Abstract

Cardiovascular bypass grafting remains a crucial therapeutic approach for complex atherosclerotic diseases. However, the clinical application of traditional grafts is hampered by limited autologous vessel availability, while the translational potential of fully cellular self-assembled vascular grafts is constrained by their prolonged fabrication. Here, we present a scaffold-guided in vivo tubular tissue self-assembly strategy to rapidly engineer functional cardiovascular bypass grafts. Using 3D-printed biodegradable scaffolds implanted subcutaneously in SD rats, we generated bioengineered tubular vascular constructs (BTCs) rich in host cells and extracellular matrix within 2 weeks. BTC exhibited biophysical and biochemical properties highly analogous to the native abdominal aorta. When used as interpositional grafts in the abdominal aorta, the BTCs demonstrated excellent patency, blood flow velocity, vascular reactivity, compliance, and histological architecture comparable to those of the native vessel over a 24-week implantation period. Our method significantly shortens the fabrication time of bioengineered vessels—from several months to two weeks—thereby aligning with the critical time window required for elective cardiovascular bypass surgery. Moreover, all materials used in this study are clinically approved, which facilitates future clinical translation. This work establishes a practical and scalable platform for the rapid, “off-the-shelf” production of bioengineered cardiovascular grafts through stable scaffold-guided in vivo tissue formation.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-025-03664-9.

Keywords: Scaffold-guided, Self-assembly, Bioengineered cardiovascular bypass graft, Tubular tissue morphogenesis, Vascular reconstruction

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of global mortality, and the development of durable revascularization therapies is crucial for reducing the disease burden [1]. As the gold standard treatment for complex atherosclerotic diseases, bypass grafting (using autologous vessels such as the internal mammary artery and great saphenous vein) is widely used in both cardiac and peripheral vascular surgery [2, 3]. This “gold standard“ status is supported by three key clinical advantages: ① Long-term follow-up data confirm its reliability — 10-year patency rates of autologous arterial and venous grafts in coronary artery bypass can reach up to 85% and 60%, respectively [4, 5], significantly outperforming early synthetic alternatives; ②It possesses inherent biomechanical compatibility with native vasculature, withstanding hemodynamic stressors such as pulsatile flow and pressure gradients; ③The risk of postoperative thrombosis and infection is relatively low due to its natural biological properties, and surgical techniques for implantation are well-established.

Unlike these traditional grafts, which rely on autologous tissues or synthetic materials, the bioengineered tubular vascular constructs (BTCs) focused on in this study are defined as tubular grafts formed either by in-situ self-assembly of host cells or via in vitro induction of cell-secreted matrices. Their core features encompass the biological activity of natural blood vessels—including the presence of living cells and functional extracellular matrix (ECM)—as well as customizable structural design, with the aim of overcoming the bottlenecks of limited autologous graft sources and insufficient biocompatibility of synthetic materials. However, the application of this therapy is limited by the availability of patients’ own vascular resources, and disease progression often forces patients to undergo repeat surgeries when their graft reserves are exhausted [5]. Although synthetic vascular grafts have been applied clinically, long-term follow-up studies indicate that their 2-year patency rate is only about 30%, which falls short of the requirements for durable revascularization [6]. Therefore, the development of novel bypass grafts that combine the functional advantages of autologous grafts with the “off-the-shelf” convenience of synthetic grafts holds great promise for improving long-term survival and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease.

In recent years, diverse strategies have been devised for the development of bioengineered BTC grafts. One widely used approach involves integrating vascular endothelial cells (ECs), smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and fibroblasts into the graft wall, endowing it with sufficient mechanical strength to withstand surgical anastomosis and in vivo perfusion pressures comparable to natural arteries [7–10]. After implantation in animal models, these constructs can be partially recolonized by host cells [11]. Additionally, alternative strategies such as using bone marrow-derived monocytes have been explored to promote vascular regeneration and functional integration [12, 13]. To stabilize vascular structures and accelerate the construction process, most existing methods rely on permanent or degradable scaffolds [13–15]. However, many scaffold materials have not yet obtained approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), severely limiting their clinical translation potential. This is because FDA approval is a clinical translation prerequisite—it validates safety, efficacy, and compliance, and non-certification blocks lab-to-clinic translation [10, 16–18].

To overcome the limitations associated with artificial scaffold materials, researchers have explored scaffold-free, cell-based vascular engineering strategies that utilize only cell spheroids or cell sheets as fundamental building units [16]. For example, cell sheet–based vascular grafts have been successfully applied in the clinic for the construction of arteriovenous fistulas required for hemodialysis [19]. The maturation of such scaffold-free engineered vessels typically involves two key stages: first, cell sheets are three-dimensionally cultured around a mandrel to form structurally stable tubular tissues [19]; subsequently, luminal perfusion is applied to promote mechanical remodeling of the vessel wall and the formation of a functional endothelial layer [16]. However, this approach requires an in vitro culture period lasting several months. Moreover, the resulting engineered vessels exhibit insufficient mechanical elasticity when subjected to arterial hypertension and continuous blood flow, which severely limits their broad application in both emergency and elective bypass surgeries.

In this study, we developed a biodegradable scaffold using a clinically approved polylactic acid (PLA)-based bioadhesive—addressing the critical challenge of limited FDA-approved materials for vascular engineering—combined with 3D printing technology to overcome the long production cycles of conventional strategies. Leveraging this approach, in a subcutaneous SD rat model, the scaffold induced host cells and ECM components to undergo in situ self-assembly along its structure, forming a BTC with biomechanical and biochemical properties similar to those of native arteries within 14 days—a timeline far shorter than the 4 weeks or longer required for traditional methods like decellularized vessels or cell sheet technologies, thus meeting the timeliness demands of emergency surgeries. This BTC can serve as an autologous interventional graft to successfully repair abdominal aortic (AA) defects, and through modulation of the local microenvironment, it facilitates the recruitment of endogenous vascular-related cells, enabling functional arterial regeneration. The BTC not only exhibits surgical manipulability and hemodynamic performance comparable to that of native arteries, but also offers advantages such as rapid fabrication (14 days vs. months for cell sheet technologies) and strong intraoperative durability, thereby overcoming key limitations of conventional scaffold-dependent or cell-based strategies, including low long-term patency rates (65–75% at 1 year for decellularized vessels vs. 100% over 24 weeks here) and prolonged tissue engineering times. This work presents a novel engineering approach for developing “off-the-shelf” vascular bypass grafts and holds great potential for clinical translation.

Experimental section

Materials and reagents

The bio-based high-precision resin eResin-PLA Pro (PH100) was obtained from eSUN®. Primary antibodies including rat monoclonal anti-CD11b (ab8878), rabbit polyclonal anti-fibronectin (FN, ab2413), mouse monoclonal anti-CD73 (ab257311), mouse monoclonal anti-CD31 (ab9498), rabbit polyclonal anti-VE cadherin (CDH5, ab232880), mouse monoclonal anti-N cadherin (CDH2, ab19348), and rabbit monoclonal anti-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain 11 (SM-MHC, ab133567) were purchased from Abcam. Additional primary antibodies included rabbit polyclonal anti-CD105 (PA5-46971), recombinant rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki67 (ab15580), rabbit polyclonal anti-arginase-1 (arg-1, PA5-85267), mouse monoclonal anti-iNOS (MA5-17139). Antibodies used for flow cytometry were as follows: CD45 monoclonal antibody (clone 30-F11, pacific blue, MCD4528), CD11b monoclonal antibody (OX-42, PE, MA5-17511), CD86 monoclonal antibody (BU63, APC, MA1-10294), and CD206 (mannose receptor, MMR) monoclonal antibody (19.2, PE, 12206942). Fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies included goat anti-rat IgG (H + L) (Alexa fluor 488, ab150157), Goat anti-rabbit or mouse IgG (H + L) (Alexa fluor 594, ab150076, ab150116), goat anti-mouse or rabbit IgG (H + L) (Alexa fluor 647, ab150115, ab150079). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, G4202), diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, D21490) was also obtained from Gibco. Histochemical staining kits included hematoxylin and eosin (HE, G1005), masson’s trichrome (MTC, G1006), sirius red (SR, G1078), verhoeff–van gieson (VVG, GP1035), alcian blue (AB, GP1041), and periodic acid–schiff (PAS, G1008). Other reagents included electron microscopy fixative (G1102), 10% Triton X-100 (G3068), bovine serum albumin (BSA, GC305010), and sodium citrate antigen retrieval solution (G1201), all obtained from Servicebio®. Iohexol contrast agent (2023B02025) was obtained from Hanson Pharmaceutical. The calcium-sensitive contrast agent Eu-DOTA-4AmC (CAS number: 481668-57-9, CB12563218) was purchased from Xi’an Kaixin Biotech Co., Ltd.

Scaffold design and 3D printing

A cylindrical vascular scaffold with an inner diameter of 2 mm and a wall thickness of 0.5 mm was designed using SolidWorks software (Dassault Systèmes, France). The scaffold featured a grid-like porous structure to mimic the volumetric characteristics of native blood vessels. The final model was exported in standard tessellation language format (Fig. S1) for subsequent 3D printing. The bio-based high-precision resin eResin-PLA Pro was selected as the printing material due to its good biocompatibility, favorable mechanical properties, and suitability for micro-scale 3D printing. According to the manufacturer’s documentation, the material has passed biocompatibility testing in accordance with ISO 10,993 standards. Printing was performed using an M-dental U60 DLP-based 3D printer (Ningbo Inteplast, China) equipped with a 405 nm light source. The standard tessellation language file was imported into the slicing software, and the printing parameters were set as follows: layer thickness = 25 μm, exposure time per layer = 8–10 s, bottom exposure time = 60 s. Support structures were automatically generated. The printing platform was calibrated before starting the print job.

After printing, the scaffolds were carefully removed from the build platform and immersed in 90% isopropyl alcohol for 10 min, followed by ultrasonic cleaning for 5 min to remove residual uncured resin. Post-curing was carried out under UV light at 60 °C for 30 min, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Dimensional accuracy was verified using digital calipers and precision gauges, and the results (Fig. S2) were compared with the original CAD design (inner diameter: 2 mm; wall thickness: 0.5 mm).

Animal approval and anesthesia protocols

A total of 40 male Sprague-Dawley rats (8–10 weeks old, weighing 280–320 g) were used in this study. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Dongguan University of Technology and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for the care and use of laboratory animals, ensuring humane treatment throughout the experimental procedures.

Prior to surgery, the rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg). The depth of anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of a paw withdrawal reflex. Vital signs were continuously monitored during the procedure to ensure the absence of pain responses. Postoperative analgesia was provided, and the animals were observed daily for recovery and welfare assessment.

Preparation of BTC

A sterile PLA vascular scaffold with an inner diameter of 2 mm and a wall thickness of 0.5 mm was implanted subcutaneously into the abdominal region of SD rats to prepare the BTC. During surgery, a small incision was made on the abdominal skin, and the pre-measured scaffold was inserted into the subcutaneous pocket. The incision was then closed using intradermal sutures. On day 14 post-implantation, the original implantation site was reopened under anesthesia, and the scaffold together with the surrounding tissue capsule was carefully retrieved. A cylindrical segment approximately 0.2 mm in length was excised from the middle portion of the construct and longitudinally sectioned to obtain both inner and outer surface samples.

The samples were immediately fixed in electron microscopy fixative for 2 h, followed by graded ethanol dehydration, critical point drying, and sputter coating with gold using a HITACHI MC1000 ion sputtering device. Surface morphology of the inner and outer layers of the BTC was then examined using a HITACHI Regulus 8100 scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi, Japan). During the experimental period, body weight and body temperature of each rat were recorded before surgery and at different time points post-implantation to evaluate systemic responses. Non-analyzed samples were stored at − 20 °C for further analysis.

Construction of AA defect model and vascular transplantation surgery

A total of 40 healthy adult male rats were used, with 20 rats allocated to each group: BTC graft group and autologous transplantation group. Five minutes before surgery, heparin (100 U/kg) was intraperitoneally injected for anticoagulation. After anesthesia, rats were fixed in a supine position, and the abdominal area was shaved and disinfected with iodophor. A midline abdominal incision was made through the skin and fascia to expose the AA, followed by careful dissection of the perivascular tissues. The aorta was clamped at both ends, and a 13-mm longitudinal incision was made on the anterior wall to create a localized defect. The lumen was flushed with heparinized saline to remove thrombi. Sterile pre-cut BTC grafts (13 mm in length, 2 mm in inner diameter, 500 μm in wall thickness) were implanted and sutured to the defect with 6 − 0/7 − 0 vascular sutures (continuous or interrupted suturing). For the autologous transplantation group, a 13-mm segment of the rat’s own aortic tissue was harvested and sutured in the same manner.

After checking for suture leakage, the distal vascular clamp was first released to expel air, followed by the proximal clamp. The abdominal cavity was irrigated with warm saline, and the peritoneum, muscle, and skin were sutured layer by layer. For AA samples without transplantation, the aorta was longitudinally dissected along the midline to obtain inner and outer surface tissues, which were immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 2 h. Samples were sequentially dehydrated in gradient ethanol, freeze-dried, sputter-coated with gold, and observed for surface morphology using a SEM following the same protocol as BTC samples, to analyze the microstructural characteristics of the aortic wall. Unused AA samples were stored at −20 °C for future use.

BTC and AA samples were taken out from the refrigerator, rewarmed in a 37 °C water bath for 2 h, cut into 5-mm specimens, and fixed on the stage of an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Dimension FastScan, USA). PBS was added to keep the samples moist. In tapping mode, a ScanAsyst-Air probe (tip radius < 2 nm) was used. Low-magnification scanning was first performed at a 50 μm×50 μm range for positioning, followed by high-resolution scanning of regions of interest (e.g., cell layers, glue membrane surfaces) at 2 μm×2 μm. The scanning rate was 1–10 Hz with a resolution of 512 × 1024 pixels. Noise was removed and planar correction was performed using Nanoscope software to extract parameters such as arithmetic mean roughness (Ra) and root-mean-square roughness (Rq). Nanoscale topographical differences in the inner/outer surfaces of BTC and AA (e.g., microvilli density, collagen fiber arrangement) were compared. Each group of samples was measured in triplicate, with 3 regions selected for analysis each time.

Water contact angle and surface morphology characterization

Samples stored at − 20 °C were thawed in a 37 °C water bath for 1 h, cut into 10 mm × 2 mm squares, and ultrasonically cleaned with ethanol and deionized water (15 min each), then dried for testing. Using a micro-syringe, 5–10 µL of distilled water droplets were dispensed onto the sample surface. The samples were placed on a SL250 contact angle goniometer (KINO Industry Co., Ltd., USA). After adjusting the position for a clear image, the droplet behavior was recorded at 5 frames/s until stable. The water contact angle (WCA) was calculated by the instrument’s tangent or height-width method.

The recorded images were processed with interpolation software to reconstruct the three-phase boundary, obtaining surface roughness (Ra, Rq), autocorrelation length, and spatial frequency. A model integrating surface height and contact angle data analyzed wetting properties. Droplet volume was calculated via multi-layer slice interpolation, with hierarchical algorithms used for multi-layer samples. Each sample was measured five times, and the average and standard deviation were reported to ensure data reliability.

2D small-angle X-ray scattering and X-ray diffraction analysis

The inner surfaces of BTC and AA were carefully separated using a micro-scalpel and fixed on the sample stage of a 2D small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan), ensuring the surfaces were flat and free of obvious defects. The X-ray wavelength was set to 1.5406 Å (Cu Kα), and measurements were performed in the small-angle range (scattering angle θ < 10°). Scattering images were acquired by a two-dimensional detector.

For raw data processing, background subtraction and normalization were conducted using Rigaku software to generate two-dimensional scattering patterns. The scattering vector Q was calculated using the formula:

|

where λ is the X-ray wavelength and θ is the scattering angle.

Radial integration of the scattering patterns was performed to obtain the intensity vs. Q (I(Q)) curves. These curves were fitted using OriginPro to extract key parameters, such as average pore size and grain size.

Using a X-ray diffraction (XRD) diffractometer (6100, Shimadzu, Japan), test round, flat samples of BTC and AA with a diameter of 15 mm and a thickness of less than 1 mm. The test parameters were set as follows: tube voltage 40 kV, tube current 30 mA, scanning range 5°−80° (2θ), scanning speed 10°/min, and step size 0.02° [20, 21]. After installing the samples, the instrument was initialized, the parameters were input for measurement, and the data were saved after completion.

2.8 Zeta potential determination

The inner surface membranes of BTC and AA samples were cut into strips (width ≤ 1.5 mm, length 20–30 mm), curled into spirals, and tightly packed into a quartz capillary (inner diameter: 2 mm, length: 50 mm) without visible gaps.

A 10⁻³ M KCl solution (pH 7.0 ± 0.1), filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane, was used as the electrolyte. Prior to sample measurement, blank calibration was performed using an empty capillary to eliminate background effects. Instrument accuracy was verified using a standard glass capillary with a known zeta potential (− 30 ± 2 mV).

The streaming potential measurements were conducted using an Anton Paar SurPASS instrument. The membrane-filled capillary was fixed in the streaming potential measurement module, with both ends connected to electrodes and a peristaltic pump. The KCl solution was pumped at a constant flow rate of 0.1 mL/min. Steady-state streaming potential (ΔV) and pressure difference (ΔP) were recorded for each sample, and each sample was tested five times.

After subtracting the blank value, the zeta potential (ζ) was calculated using the following formula:

|

where: η: solution viscosity, r: capillary radius, ε: relative permittivity, ε0 : vacuum permittivity.

Cyclic elasticity and suture retention strength testing

BTC and AA samples rewarmed in a 37 °C water bath were trimmed to dimensions of 12 mm in length, 2 mm in width, and 1 mm in thickness. Using a DMA dynamic thermomechanical analyzer (Q800, TA Instruments, USA), the samples were fixed in a single-cantilever fixture. The temperature was programmed to rise from room temperature to 37 °C and held constant. In strain-controlled mode, a strain of 25% was applied for 10 cycles, with stress-strain curves and elastic recovery data recorded.

Cut BTC (inner diameter 2 mm, wall thickness 0.5 mm) and AA (inner diameter 2 mm, wall thickness 0.34 mm) into 13 mm-long tubes. Perform interrupted sutures using 8 − 0 absorbable sutures with a stitch spacing of 3 mm. Each sample should have ≥ 5 suture points. Prepare 4 samples per group. Use a Zwick/Roell Z005 universal testing machine equipped with a 1 N load cell and custom arc-shaped fixtures. Set the tensile speed to 1 mm/min, ensuring alignment between the sample axis and tensile direction. Clamp the sample and initiate tensile testing until failure. Record the force-displacement curve, maximum failure load, and failure mode (suture pullout/material rupture).

Histochemical staining

For BTC samples (excised subcutaneously), AA, and BTC/autograft samples collected at corresponding time points post-transplantation, the tissues underwent sequential ethanol gradient dehydration, xylene clearing, and paraffin embedding after SEM detection [22]. Using a PM-24 paraffin microtome (Saiweier, China), 4-µm-thick tissue sections were prepared. The paraffin sections were first immersed in xylene I and II for 10 min each, followed by sequential incubation in absolute ethanol, 95%, 85%, and 75% ethanol for 5 min each, and finally washed three times with PBS buffer for 5 min each. Various histochemical staining kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions [23]. Stained images were acquired using a whole-slide scanner (3DHISTECH, Hungary). Quantification of components in stained sections was performed using FiJi ImageJ-win 64 software (based on ImageJ 2.x, developed by the National Institutes of Health, USA), with three individual biological samples per group.

Immunocytochemistry

Deparaffinized sections were first immersed in antigen retrieval buffer, boiled at medium heat for 15 min, and then allowed to cool naturally. Subsequently, the sections were washed three times with PBS buffer for 5 min each. To block non - specific binding, the sections were incubated with 5% goat serum in PBS for 10 min at 37 °C.

Primary antibodies were then applied to the sections, which were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After removing the primary antibodies, the sections were equilibrated to room temperature for 30 min and gently washed with PBS to remove any unbound antibodies. Next, secondary antibodies were applied to the sections and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark to prevent photobleaching. Finally, the sections were stained with DAPI for 5 min to visualize the cell nuclei.

All primary and secondary antibodies were used in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunofluorescence images of the stained samples were acquired using a 3DHISTECH whole - slide scanner. For subsequent image analysis, Fiji ImageJ - win64 software was employed to process and quantify the data.

Transmission electron microscopy observation

BTC and autologous transplantation samples retrieved at 7 days post-surgery were immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/1% paraformaldehyde electron microscopy fixative at 4 °C for 2 h. Samples were rinsed 3 times with 0.1 M PBS (10 min each), post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h, and dehydrated in gradient ethanol (50%→70%→90%→100%) for 15 min each. After two 15-min transitions with 100% acetone, samples were infiltrated with epoxy resin (acetone: resin = 1:1 for 1 h; 1:2 for 2 h; pure resin overnight) and polymerized at 60 °C for 48 h. Ultra-thin Sects. (60–80 nm) were cut using an ultramicrotome and double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for 15 min each. Vascular ultrastructure images were acquired using a Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HT7700,HITACHI, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV.

Flow cytometry

Tissues from BTC and autologous grafts at 7 days post-surgery were minced and digested in a solution containing 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and 1 mg/mL collagenase IV at 37 °C for 30 min with gentle agitation. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm strainer, centrifuged (300 g, 5 min), and the supernatant discarded. Cells were lysed using 1 mL of RBC Lysis Buffer (eBioscience) for 5 min at room temperature, followed by two washes with PBS. The cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL.

For immunostaining, 100 µL of cell suspension was incubated with Fc receptor blocker (Mouse BD Fc Block™) for 15 min at 4 °C. Fluorescently conjugated antibodies against CD45, CD11b, CD68, CD206, and CD86 were added according to the manufacturer’s instructions and incubated for 30 min in the dark. Cells were washed twice with 2 mL of PBS. Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed again, and resuspended in 300 µL of PBS.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a Coulter CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman, USA), acquiring 10,000 events per sample. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (v10.8.1), with isotype controls used to gate out non-specific binding.

Doppler ultrasound and micro-computed tomography detection

At postoperative weeks 1, 4, and 12, after anesthesia, the animals were placed in a supine position and fixed. The abdominal area was shaved and coated with coupling gel. A MyLab SigmaPVET color doppler ultrasound system (CDU, Esaote, Italy) was used to measure the internal diameter, external diameter, and wall thickness (WT) of the graft. Color Doppler imaging was employed to assess blood flow velocity, including peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end-diastolic velocity (EDV), as well as the resistance index (RI). Spectral Doppler was used to record the Doppler spectra across three cardiac cycles.

At postoperative week 24, basal spontaneous pulse frequency of the artery was continuously recorded for 10 min using a biological signal acquisition system (BL420, YiLian Medicine, Shanghai, China), with electrodes closely attached to the arterial surface. The average value was calculated and used as a reference for subsequent electrical field stimulation parameter settings.

Following baseline data collection, the experimental animals were subjected to general anesthesia. Iohexol contrast agent was then administered via tail vein injection at a dose of 1.5 mL/kg. Subsequently, whole-artery computed tomography(CT) scanning was performed using a Quantum GX2 Micro-CT system (PerkinElmer). Scanning parameters were set as follows: voltage at 50–70 kVp to ensure image resolution while minimizing radiation exposure; current at 400–500 µA to maintain stable X-ray output; and slice thickness controlled between 50 and 100 μm to clearly capture structural details of the artery.

Next, the calcium-sensitive contrast agent Eu-DOTA-4AmC was injected via the tail vein at a dose of 1.3 mL/kg. After an appropriate waiting period of 15–30 min to allow full distribution and binding of the contrast agent to calcium ions, the same Micro-CT scanning protocol was repeated.

After completing both scans, the electrodes of the electrical stimulation device were precisely fixed at both ends of the artery. The stimulation intensity and frequency were gradually adjusted to stabilize the arterial pulsation at a pacing frequency of 1 Hz. The imaging view was switched to a top-down perspective, and secondary dynamic imaging of the abdominal aorta was conducted using the built-in professional image analysis software of the Quantum GX2 Micro-CT system. This software, based on 3D registration and optical flow algorithms, performed frame-by-frame analysis of the continuous image sequences, enabling high-precision quantification of the motion trajectories of both the intima and adventitia.

Finally, three-dimensional reconstruction was carried out based on data from both scans. Using image processing algorithms, key functional indicators—including vascular patency, calcium wave conduction velocity, and anisotropy ratio—were systematically analyzed.

Blood pressure and compliance assessment

At 24 weeks post-surgery, rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), placed in a supine position on the operating table, and the abdomen was routinely disinfected. A PE-50 catheter pre-filled with heparinized saline (10 U/mL) was inserted into the proximal segment of the AA replacement (approximately 5 mm from the anastomosis) and secured with silk sutures. A TMY-203B pressure sensor (TaiMeng, China) was connected to the BL420 Biological Signal Acquisition System, configured with: Sampling frequency: 100 Hz, Time constant: 0.001 s, Filtering frequency: 100 Hz. After air was purged from the sensor-catheter system, blood pressure waveforms were recorded using the Blood Pressure Recording module of the BL420 software. Following signal stabilization, continuous recordings were acquired 2 s, with synchronous marking of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) peaks during the cardiac cycle.

Vascular diameter measurements were performed using a high-frequency Doppler ultrasound system (VisualSonics Vevo 3100, 30 MHz probe). Anesthetized rats were positioned supine, and ultrasonic coupling agent was applied to the abdomen. Longitudinal sections of the replaced aortic segment were obtained 10 mm from the anastomosis. Using M-mode imaging, diameter changes were recorded over at least three consecutive cardiac cycles to measure the maximum systolic diameter (Dmax) and minimum diastolic diameter (Dmin). Each measurement was repeated three times, and the mean values were used for analysis. Vascular compliance (C) was calculated using the following formula:

|

where Dmax,Dmin: Systolic and diastolic vessel diameters (mm), Psys,Pdia: Systolic and diastolic blood pressures (mmHg), L: Length of the measured vessel segment (fixed at 13 mm). All measurements were performed independently by two experienced investigators, and the results were averaged.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For comparisons among multiple groups (≥ 3 groups), a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was first performed to assess overall differences, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons if the ANOVA was significant. For interactions between two variables, a two-way ANOVA was used with Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. Two-group comparisons were analyzed using Student’s t-test (parametric data) or the Mann-Whitney U test (nonparametric data). All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

The biochemical and biophysical analysis of endogenous cells and ECM in self-assembled BTC tube walls

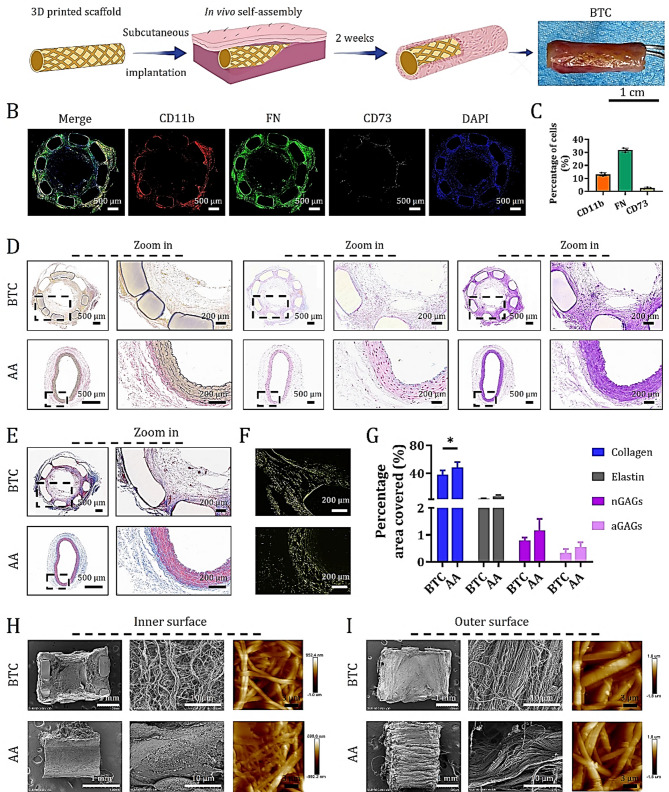

After subcutaneous implantation of 3D-printed PLA scaffolds into the abdominal region of rats, the incisions healed rapidly without signs of swelling or adverse reactions (Fig. S3). Over a 14-day period, body temperature and weight of the implanted rats remained comparable to those of the non-surgical control group (Fig. S4). Macroscopic observation revealed that the PLA scaffolds were initially yellow and porous (Fig. S2), but after 14 days of subcutaneous implantation, host tissues organized along the volumetric architecture of the scaffold, forming autologous tissue-like BTCs resembling native anatomy (Fig. 1A). Immunofluorescent staining for CD11b, FN, and CD73 on cross-sectional midsections of retrieved BTCs demonstrated that (13.2 ± 1.1) % of endogenous cells expressed monocyte markers, (31.7 ± 1.6) % expressed fibroblast markers, and (3.2 ± 0.3) % expressed mesenchymal stem cell markers (Fig. 1B and C). These cells were evenly distributed throughout the BTC wall. Serial sections from the same cross-sections underwent histological staining with VVG, AB, PAS, MTC, and SR, revealing uniform deposition of ECM components within the BTC walls due to endogenous cell infiltration (Fig. 1D and E and S5). These included elastic fibers (black), nGAGs (blue), aGAGs (magenta), and collagen (blue). Under polarized light microscopy, collagen fibers exhibited yellow (Type I) and green (Type III) birefringence (Figs. 1E and S5). Compared to native AA from SD rats, the BTC walls showed comparable deposition of elastin, aGAGs, and nGAGs, although collagen content was lower (Fig. 1G). These findings indicate that the 3D-printed PLA scaffold effectively recruits endogenous monocytes, fibroblasts, and mesenchymal stem cells to initiate immune modulation and ECM deposition, resulting in a compositionally similar ECM to that of the target AA vessel wall.

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence, histochemical staining, and SEM analysis of self-assembled BTC. (A) Schematic illustration of the BTC preparation strategy and macroscopic photographs of BTC 14 days after subcutaneous implantation in rats. (B) Immunostaining of CD11b, FN, and CD73 on cross-sectional tissue sections of BTC. (C) Quantitative analysis of the percentages of CD11b⁺, FN⁺, and CD73⁺ cells (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). (D) VVG staining (specific for elastin), AB staining (specific for aGAGs), and PAS staining (specific for nGAGs) showing the distribution of elastin, aGAGs, and nGAGs in cross-sections of BTC and AA, respectively. (E) MTC staining highlighting collagen fibers in cross-sections of BTC and AA. (F) SR staining analyzed under polarized light to distinguish between type I collagen (yellow/red, strong birefringence) from type III collagen (green, weak birefringence) in BTC and AA. (G) Quantitative analysis of the percentages of collagen, elastin, nGAGs, and aGAGs staining (data are mean ± SD, sample size n = 3, *P < 0.05). H-I. SEM and AFM images of the inner (H) and outer (I) surfaces of BTC and AA tube walls

SEM imaging further confirmed that the nanofibrous morphology of the self-assembled ECM on both the inner and outer surfaces of the BTC closely resembled that of the native AA (Fig. 1H and I). However, unlike the endothelial layer lining the luminal surface of the AA, the BTC lacked such coverage. AFM surface topography analysis revealed distinct structural differences: the BTC exhibited a “loose short-fiber network” morphology on both inner and outer surfaces, with slightly denser stacking on the outer side, suggesting a flexible structure with high surface area—favorable for cell adhesion but potentially less mechanically robust. In contrast, the AA displayed a “dense long-fiber interweave” on both surfaces, with subtle surface modifications on the outer wall, indicating a rigid and mechanically superior structure, albeit with a potentially stiffer biological interface. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the 3D-printed PLA scaffold is capable of inducing subcutaneous tissue to self-assemble into a BTC with ECM characteristics closely matching those of the native AA wall.

Characterization of tissue-like ECM in subcutaneously self-assembled BTC

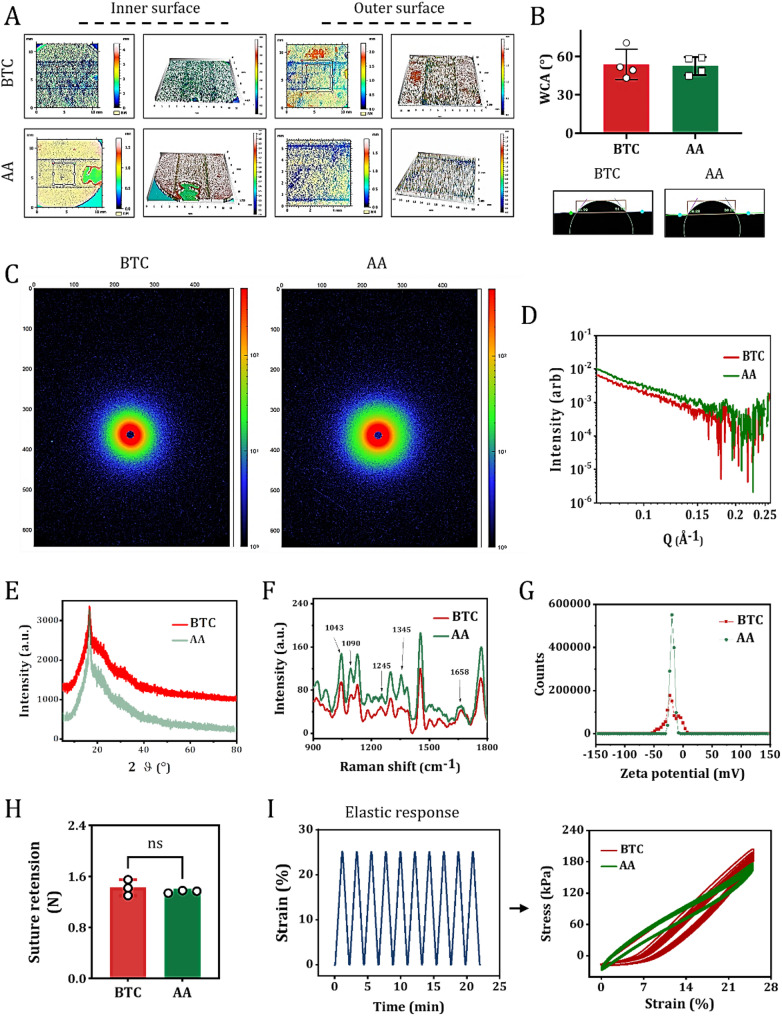

We further investigated whether the biophysical and biochemical properties of the tissue-like ECM in BTC matched the transplantation requirements of natural AA. Static WCA analysis showed that the inner and outer surfaces of BTC, self-assembled by 3D-printed PLA scaffolds, achieved synergistic hydrophilicity through the chemical hydrophilicity of GAGs (containing carboxyl and sulfonic groups) and the Wenzel effect of GAG nanofiber structures in the ECM (Fig. 2A). The Wenzel effect describes how surface roughness amplifies a material’s intrinsic wettability: micro/nanostructures enhance water spreading and capillary action, making hydrophilic surfaces more hydrophilic. This is relevant to graft-host interaction as optimized surface wettability promotes cell infiltration and ECM deposition, while its role in fluid compatibility lies in facilitating endothelialization to improve hemocompatibility.This transformed the originally hydrophobic PLA substrate into a surface with anisotropic wettability similar to AA (Fig. 2B), confirming the successful ingrowth of ECM components and reconstruction of interfacial properties. Two-dimensional SAXS revealed that the scattering patterns of BTC ECM exhibited similar long-period ordered structural features to AA ECM (Fig. 2C and D), directly demonstrating that the microscale arrangement of its tissue anisotropy is consistent with natural blood vessels. XRD results showed that the ECM in BTC exhibited an “amorphous-crystalline mixed structure” (Fig. 2E), highly consistent with the characteristics of native AA ECM. In BTC, collagen fibers displayed a crystalline peak at 16.7°, coexisting with amorphous regions, while elastin was predominantly amorphous, indicating that the molecular packing pattern possesses significant biomimetic features.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of tissue-like ECM in BTC. (A) Anisotropic wettability topographical features of the inner and outer surfaces of BTC and AA. (B) Quantitative analysis of WAC on the inner surfaces of BTC and AA. Data are mean ± SD; n = 3. Insets show representative WAC images of BTC and AA inner surfaces. (C) Representative 2D SAXS images of the inner-to-outer surfaces of BTC and AA. (D) One-dimensional curves derived from 2D SAXS images of BTC and AA via radial integration. E-G. XRD spectra (E), Raman spectra (F), and zeta potential plots (G) of BTC and AA inner surfaces. (H) Quantitative analysis of suture retention strength in BTC and AA. Data are mean ± SD; n = 3. ns: no significance. (I) Tensile force vs. time response curves (left panel) and stress-strain response curves (right panel) of BTC and AA under 25% strain conditions

Polarized Raman spectroscopy revealed that the characteristic molecular vibration patterns of the ECM in BTC were completely matched with those in the AA. Specifically, the intensity ratios (I∥/I⊥) of the amide I bands of collagen (~ 1245 cm⁻¹) and elastin (~ 1658 cm⁻¹) along the parallel and perpendicular directions relative to the fiber axis showed consistent trends (Fig. 2F). Moreover, key spectral peaks including the phenylalanine ring breathing mode of collagen (~ 1043 cm⁻¹), the C-O-C symmetric stretching vibration (~ 1090 cm⁻¹), and the CH₂ deformation vibration (~ 1345 cm⁻¹) of GAGs further indicated similar molecular orientation and structural symmetry between BTC and AA. These findings provide chemical bond-level evidence for the consistency of anisotropy between the two tissues. Zeta potential analysis revealed that both BTC and AA exhibited weakly negative charge characteristics (Fig. 2G), with charge densities close to the acidic GAGs/proteoglycan-dominated pattern of natural ECM, ensuring low immunogenicity and a suitable cell-adhesive interface.

Mechanical property tests showed that the ingrowth of ECM in BTC endowed it with suture retention strength comparable to AA (suture retention strength test, Fig. 2H). The suture retention strength of BTC was measured at (1.42 ± 0.2) N, comparable to that of native AA (1.36 ± 0.07) N. Importantly, this value exceeds the performance benchmarks for small-diameter vascular grafts reported in clinical studies, where a burst pressure of 90 mmHg is widely recognized as the critical threshold to prevent suture site leakage or graft detachment during surgery and post-implantation [10]. This alignment with clinical safety standards confirms that BTC meets the essential mechanical requirements for resisting suture-induced stress—key to avoiding complications in small-vessel reconstruction. In cyclic stretching tests at 25% deformation, BTC maintained approximately 90% of its initial tensile stress after 10 cycles, slightly lower than AA’s 92% (Fig. 2I), but still meeting the basic mechanical requirements for vascular substitutes. In conclusion, the 3D-printed PLA scaffold-induced self-assembled BTC closely mimics the biophysical (wettability, anisotropy, charge properties, mechanical performance) and biochemical (ECM composition, molecular structure) characteristics of the target application site, natural blood vessels AA.

Contribution of BTC as an intra-arterial graft in the functional arterial reconstruction after severe vascular injury

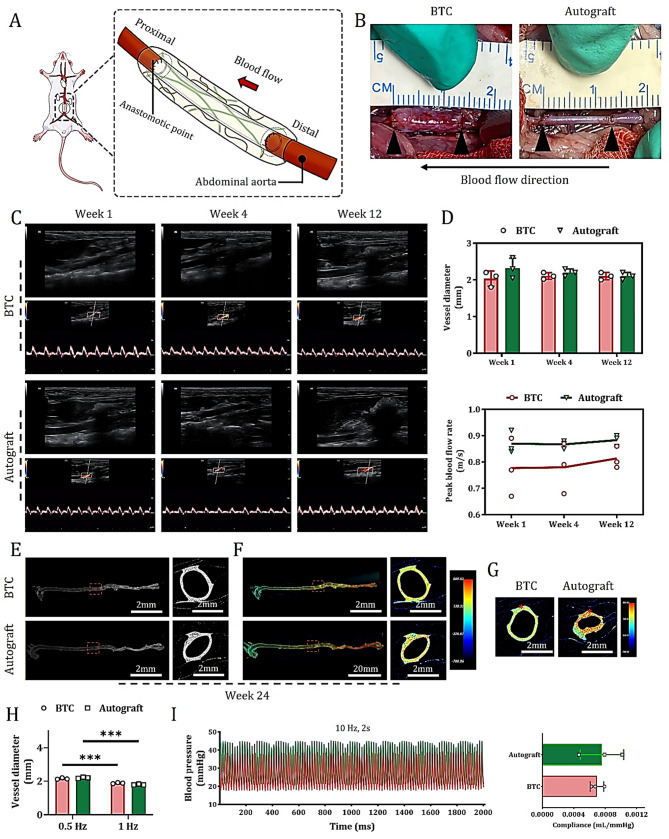

To evaluate whether BTC can function as a substitute for diseased arteries under conditions of severe vascular injury—and whether it can harness the host’s regenerative potential to achieve both structural and functional vascular repair, much like the “gold standard” autologous vascular graft—we established a severe AA injury model. In this model, the AA was completely transected surgically, resulting in the loss of local intima, media, and adventitia. The BTC was then implanted and anastomosed at the injury site (Fig. 3A), with excised autologous vessels serving as positive controls.

Fig. 3.

Contribution of BTC as an interventional graft for AA in functional arterial reconstruction. (A) Schematic diagram of experimental measurements. (B) Macroscopic observation of grafts in each group at 1-week post-treatment. (C) Representative ultrasound evaluations of grafts and host abdominal aortic lumens at 1-, 4-, and 12-weeks post-treatment: Upper panels: Doppler ultrasound images (showing lumen patency and structure); Lower panels: Color Doppler spectral images (reflecting blood flow direction, velocity, and characteristics). (D) Quantitative analysis of vascular inner diameter (upper panel) and maximum blood flow velocity (lower panel) of grafts at 1-, 4-, and 12-weeks post-treatment (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). (E) CT images of the entire aorta integration (lateral and top views). (F) Lumen calcium-sensitive dye-stained images of vascular wall calcium waves (lateral and top views). (G) Circular calcium wave conduction visualized by calcium ion dye staining after point stimulation of the abdominal aortic media (red asterisk indicates the electrode position). I. Quantitative analysis of basal vascular inner diameter and post-1 Hz point-stimulation systolic inner diameter in the abdominal aorta replacement area of each group of animals at 24 weeks post-treatment (data are mean ± SD, n = 3, ***P < 0.001). (H) Representative curves of blood pressure response at 24 weeks post-treatment. Right panel: Quantitative analysis of vascular compliance (data are mean ± SD, n = 3)

One week after surgery, laparotomy revealed that BTC maintained a well-preserved tubular structure at the implantation site, with red blood flowing freely through its transparent lumen. The 3D-printed PLA scaffold was clearly visible within the vessel wall, exhibiting a reinforcing structure reminiscent of steel rebar in concrete. In contrast, the autograft appeared milky white and semi-transparent (Fig. 3B). These macroscopic observations were further confirmed by doppler ultrasound and CDU spectral imaging (Fig. 3C). At 4- and 12-weeks post-surgery, CDU results showed that both BTC and the autograft maintained stable tubular structures and normal arterial blood flow patterns (Fig. 3C). Quantitative analysis of vascular diameter and peak flow velocity further validated BTC’s excellent performance in maintaining vascular patency (Fig. 3D).

By 24 weeks post-implantation, micro-CT imaging demonstrated that the engineered BTC graft preserved its intact tubular morphology and was well integrated into the rat’s entire aortic system, with no signs of stenosis or collapse (Fig. 3E). Calcium imaging revealed the presence of functionally contractile vascular SMCs in the entire AA segments reconstructed with either BTC or autografts. During spontaneous contractions, calcium waves propagating along the direction of blood flow were clearly observed from both top and side views, exhibiting distinct anisotropic conduction characteristics. Specifically, in BTC, the longitudinal and transverse calcium wave conduction velocities were approximately 1.2 cm/s and 1.0 cm/s, respectively (Fig. 3F), while in the autograft, the corresponding values were 1.6 cm/s (longitudinal) and 1.3 cm/s (transverse). Further field stimulation at 1 Hz revealed that the transverse conduction velocities in BTC and autograft reached 1.23 cm/s and 1.56 cm/s, respectively (Fig. 3G). All experimental groups exhibited a baseline spontaneous oscillation frequency of approximately 0.5 Hz, which could be stably entrained to 1 Hz via electrical field stimulation. Under these conditions, both BTC and autograft vessels exhibited contraction responses, with maximal reductions in luminal diameter of approximately 10% and 18%, respectively (Fig. 3F and I). These findings indicate that, by 24 weeks post-implantation, BTC had largely restored normal electrophysiological function, including pacemaker responsiveness and calcium wave propagation properties, although its contractile response remained slightly weaker compared to the autologous graft.

Invasive blood pressure recordings using the BL420 system further revealed that under high-frequency (10 Hz) electrical stimulation, the BTC-reconstructed abdominal aorta displayed a periodic blood pressure response pattern similar to that of the autograft group, albeit with slightly higher overall blood pressure levels (Fig. 3I). Quantitative compliance analysis showed that the abdominal aorta treated with BTC exhibited slightly reduced compliance compared to the autograft group, though the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 3I). Collectively, these results clearly demonstrate that BTC effectively promotes the regeneration and reconstruction of functional arteries in the repair of AA defects.

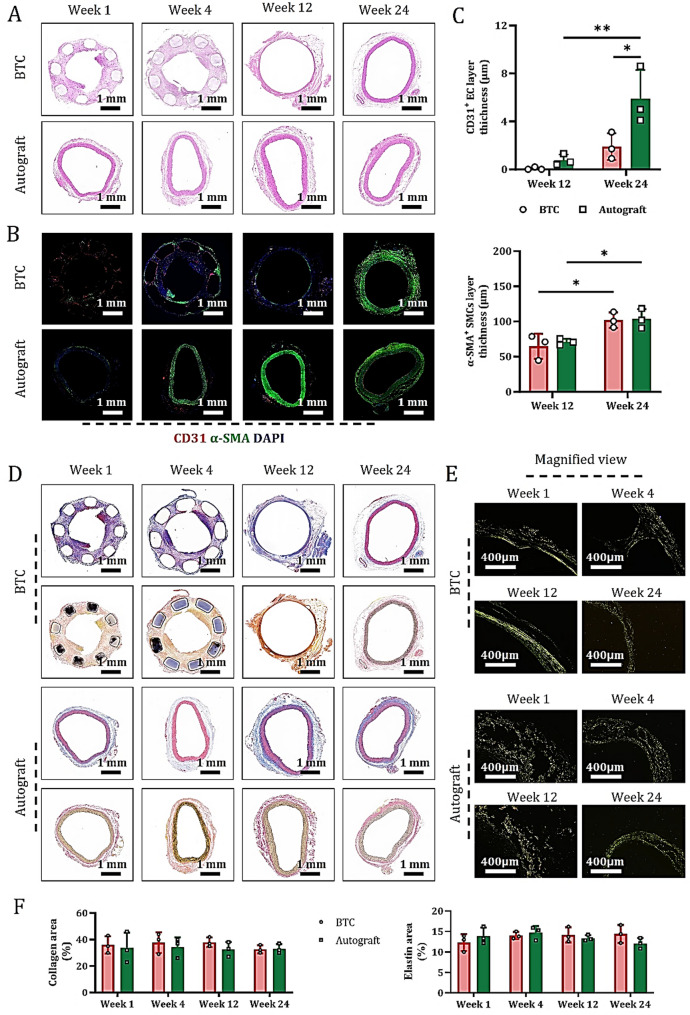

Dynamic morphological transformation of BTC-derived cells during vascular maturation

To investigate the process of complete vascular repair, tissue samples were collected at 1 week (short term), 4 weeks (transitional medium term), 12 weeks (medium term), and 24 weeks (long term) after treatment. HE staining of central sections from the healed anastomotic sites showed that, compared with the autograft group, the BTC group gradually formed a dense, organized, and arterialized vascular wall structure at 24 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 4A), whose morphological characteristics were highly similar to those of autologous AA derived from the manufacturing model after treatment. Dynamic evolution analysis revealed that the BTC grafts followed a coordinated regulatory mechanism of “tubular structure guidance-cell response-matrix remodeling” within 1–4 weeks after implantation: “Tubular structure guidance” refers to the BTC scaffold’s tubular architecture directing cell migration and alignment; “cell response” involves scaffold-triggered EC proliferation/lumen formation and SMC differentiation; “matrix remodeling” denotes cell-driven collagen/elastin deposition and organization to reinforce the vascular wall. In contrast, autologous blood vessels primarily underwent an evolution pattern of “injury-repair-adaptation” during this stage. This difference was validated by immunofluorescence staining for CD31 and α-SMA in tissue sections from the same site (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

BTC develops into mature blood vessels during arterial anastomosis. At 1-, 4-, 12-, and 24-weeks post-treatment, (A) HE staining of the middle cross-section of each explanted graft (showing tissue structure development). (B) Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (EC marker) and α-SMA (SMC marker) on paraffin sections of the same cross-section. (C) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD31⁺ (upper) and α-SMA⁺ (lower) cells (data are mean ± SD, n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (D) MTC staining (revealing collagen fibers alignment, upper) and VVG staining (visualizing elastic fibers, lower) on paraffin sections of the same cross-section. (E) SR staining under polarized microscopy on the same sections (observing collagen I and III fiber alignment). (F) Quantitative analysis of collagen (left) and elastin (right) staining percentages in each group of grafts at 1-, 4-, 12-, and 24-weeks post-treatment (data are mean ± SD, n = 3)

Time-series analysis showed that the intimal and medial structures of BTC grafts gradually optimized and exhibited a significant trend toward organization over time (Figs. 4B and S6). Notably, because autografts were derived from autologous AA peeled from the manufacturing model, the EC monolayer was prone to detachment during saline washing, resulting in the failure to form mature CD31+ ECs in the inner wall and immature α-SMA+ SMCs in the middle wall of the autograft group within 4 weeks postoperatively (Figs. 4B and S7). Quantitative analysis showed that the bridged arteries in both BTC and autograft groups began to take shape at 12 weeks postoperatively and reached maturity at 24 weeks (Fig. 4C).

Assessment of matrix remodeling maturity in graft tissues via MTC, VVG, and SR staining (combined with polarized and ordinary light microscopy) revealed that, compared with autografts, the BTC group exhibited more pronounced dynamic evolution of collagen fibers (types I and III) and elastin fibers at the intima-media, media, and media-adventitia interfaces during the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases at 24 weeks in vivo (Fig. 4D and F and S8). These results fully demonstrate that BTC effectively promotes the formation and maturation of neovascular AA during arterial anastomosis.

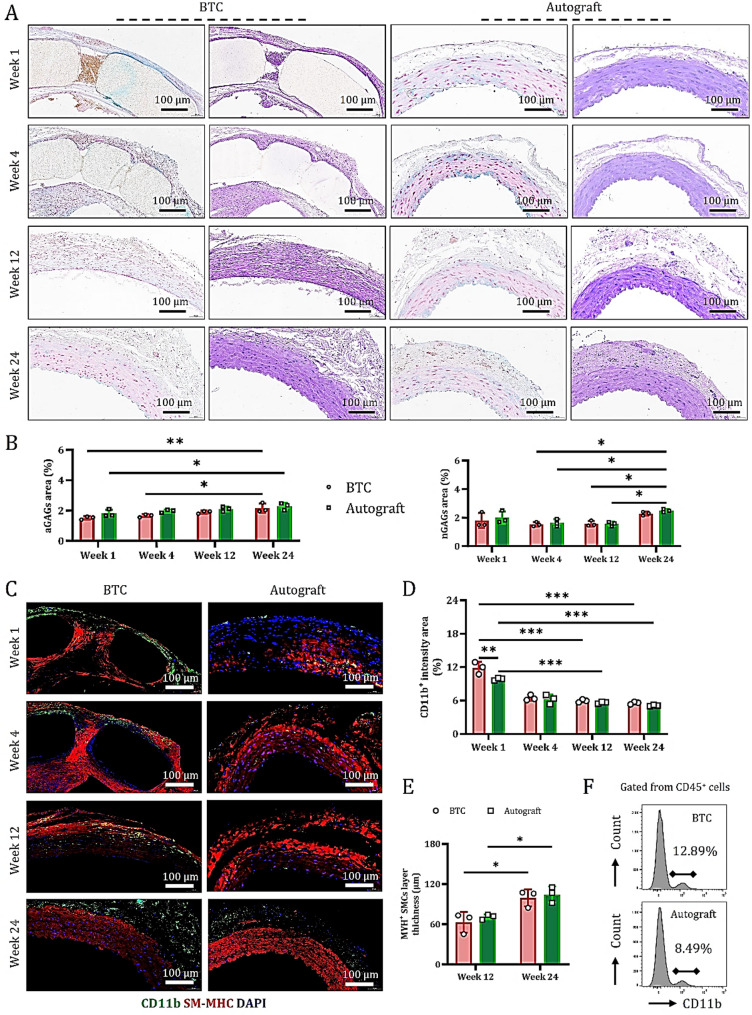

GAGs in BTC synergize with macrophages to promote SMC regeneration

Understanding which biochemical active components in the subcutaneously self-assembled BTC contribute to vascular repair is an issue of significant importance. Histological analysis using AB and PAS staining on tissue sections collected at 1 week, 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks post-surgery (Fig. 5A) revealed that aGAGs rapidly accumulated within the vessel walls of both BTC and autografts during the early phase of in vivo regeneration (1-week post-op), helping to stabilize the newly formed vasculature. nGAGs, due to their high water-retention capacity, provided a necessary hydrated microenvironment for neo-tissue formation and contributed to the mitigation of local inflammatory responses.

Fig. 5.

Polysaccharides in BTC synergize with macrophages to promote dynamic maturation of smooth muscle cells. (A) AB and PAS staining of mid-cross sections of grafts from different groups at 1 week, 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks post-operation, showing the stage-specific distribution characteristics of polysaccharide components within the vessel wall. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of aGAGs and nGAGs stained areas (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of CD11b (macrophage marker, green) and SM-MHC (SMC marker, red) on paraffin sections of cross-sections of grafts from different groups, illustrating the spatial distribution and abundance changes of cells at various time points. D-E. Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD11b+ macrophages (D) and SM-MHC+ cells (E) (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). F. Flow cytometry analysis of the expression levels of CD11b+ macrophages within CD45+ cells in grafts from different groups at 1-week post-operation

During the mid-phase (4–12 weeks post-op), as the 3D-printed PLA scaffold was gradually degraded, the newly formed blood vessels gradually matured, aGAGs levels continued to increase and their distribution became more organized. These polysaccharides not only provided physical support but also promoted smooth muscle cell maturation, while nGAGs expression gradually decreased. By the late stage (24 weeks post-op), synthesis and deposition of both aGAGs and nGAGs had stabilized (Fig. 5A and B), primarily accumulating within the mature vessel walls and forming a complex matrix network that supported long-term vascular stability. Previous studies have indicated that nGAGs play a crucial role in preventing excessive scar formation and maintaining vascular elasticity and compliance.

Further immunofluorescence analysis using CD11b (macrophage marker) and SM-MHC (SMC marker) demonstrated that, during the repair of severe arterial injury, aGAGs and nGAGs in both BTC and autografts recruited monocytes, thereby promoting the formation of repair phenotype SM-MHC+ vascular SMCs (Fig. 5C and D and S10-S11). Notably, during the early phase (1-week post-op), host-derived monocytes actively migrated to the injury site to clear inflammatory factors. Due to its unique ECM nanofiber porous architecture, BTC exhibited a stronger monocyte-capturing capacity than the autograft (Fig. 5C and D). Flow cytometry analysis further confirmed this observation: at 1-week post-surgery, the proportion of CD11b+ cells in the BTC group was significantly higher than in the autograft group (Fig. 5F).

In summary, the self-assembled polysaccharide components in BTC, together with subcutaneously infiltrating monocytes, synergistically promote the generation of repair-associated smooth muscle cells.

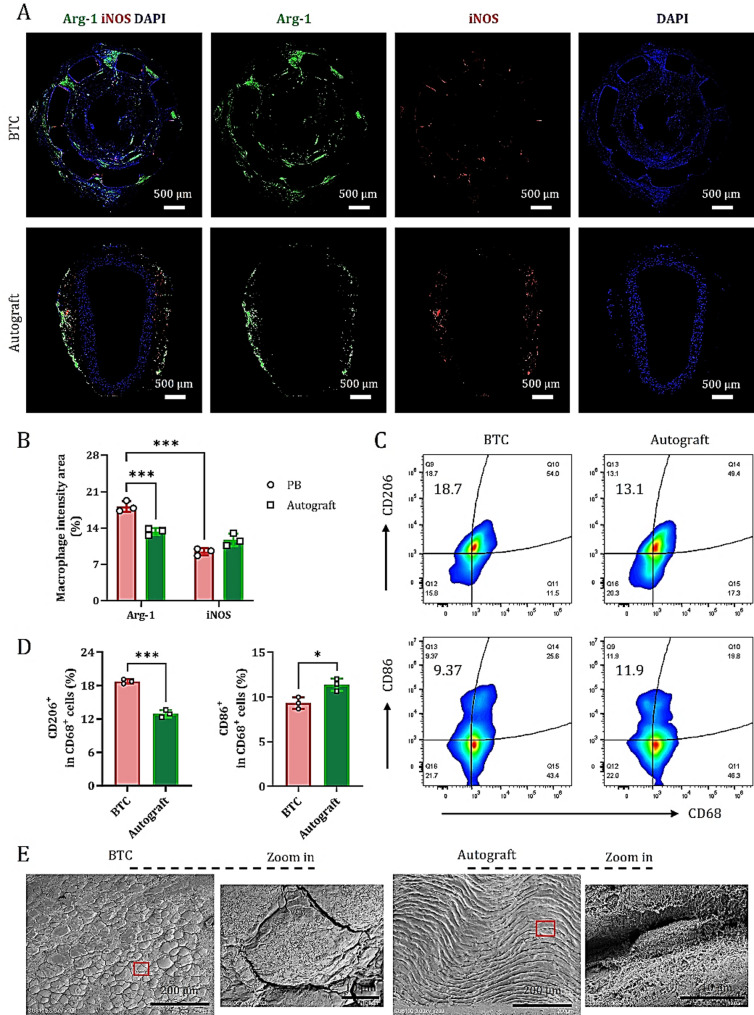

BTC induces pro-regenerative macrophage polarization at arterial injury sites during early treatment

To evaluate the early contribution to complete vascular repair, tissue samples were collected one week after treatment. Immunofluorescence staining of the mid-portion of the grafts for Arg-1 and iNOS revealed distinct macrophage polarization patterns between the BTC and autograft groups.

In the BTC group, abundant Arg-1+ macrophages (M2 phenotype, regeneration-promoting) were observed across all layers of the graft wall, including the intima, media, and adventitia. In contrast, iNOS+ macrophages (M1 phenotype, pro-inflammatory) were sparsely distributed around the PLA scaffold (Fig. 6A). In the autograft group, Arg-1+ macrophages were predominantly localized to the outer vessel wall, with only minimal infiltration of iNOS+ macrophages in the media. Neither Arg-1+ nor iNOS+ macrophages were detected near the luminal surface (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

BTC induces pro-regenerative polarization of macrophages at sites of severe arterial injury. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of Arg-1 (M2 macrophage marker) and iNOS (M1 macrophage marker) on mid-cross sections of grafts from different groups at 1-week post-operation. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of Arg-1+ and iNOS+ cells (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). *P < 0.001. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of the expression levels of CD206+ (M2 macrophage marker) and CD86+ (M1 macrophage marker) within CD68+ cells in grafts from different groups at 1-week post-operation. (D) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD206+ and CD86+ cells (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). *P < 0.05, *P < 0.001. (E) SEM images of the inner surface of the middle cross-section of grafts in each group at 1-week post-operation

Quantitative analysis demonstrated that, in the BTC group, the proportion of Arg-1+ macrophages (18.13 ± 1.68) % was significantly higher than that of iNOS+ macrophages (9.35 ± 0.68) % (*P < 0.001), indicating that BTC effectively induces a robust regenerative immune response at severely injured sites. In contrast, in the autograft group, the proportions of Arg-1+ and iNOS+ macrophages were (13.25 ± 0.70) % and (11.35 ± 1.12) %, respectively, with no significant difference between them. The overall regenerative response in this group was markedly weaker compared to the BTC group (Fig. 6B).

Flow cytometry further validated these findings. Among dissociated cells isolated from the graft wall, the percentage of CD206+ macrophages (M2 marker) in the BTC group was (18.7 ± 0.2) %, significantly higher than that in the autograft group (12.0 ± 0.6) %. Conversely, the percentage of CD86+ macrophages (M1 marker) was significantly lower in the BTC group (9.3 ± 0.9) % compared to the autograft group (11.4 ± 0.5) % (Fig. 6C and D).

SEM observations further revealed that the inner wall surface of the anastomosis in the BTC group was adhered with a large number of flat fusiform macrophages, while the inner wall of the autologous graft group was dominated by wavy arranged endothelial cells (Fig. 6E). In summary, BTC enhances the immunological microenvironment conducive to tissue repair during the early phase following severe arterial injury by recruiting vascular-resident monocytes and promoting their polarization toward an M2 macrophage phenotype. These data suggest that early and effective monocyte colonization on the luminal surface of BTC contributes to the establishment of a more favorable regenerative immune microenvironment.

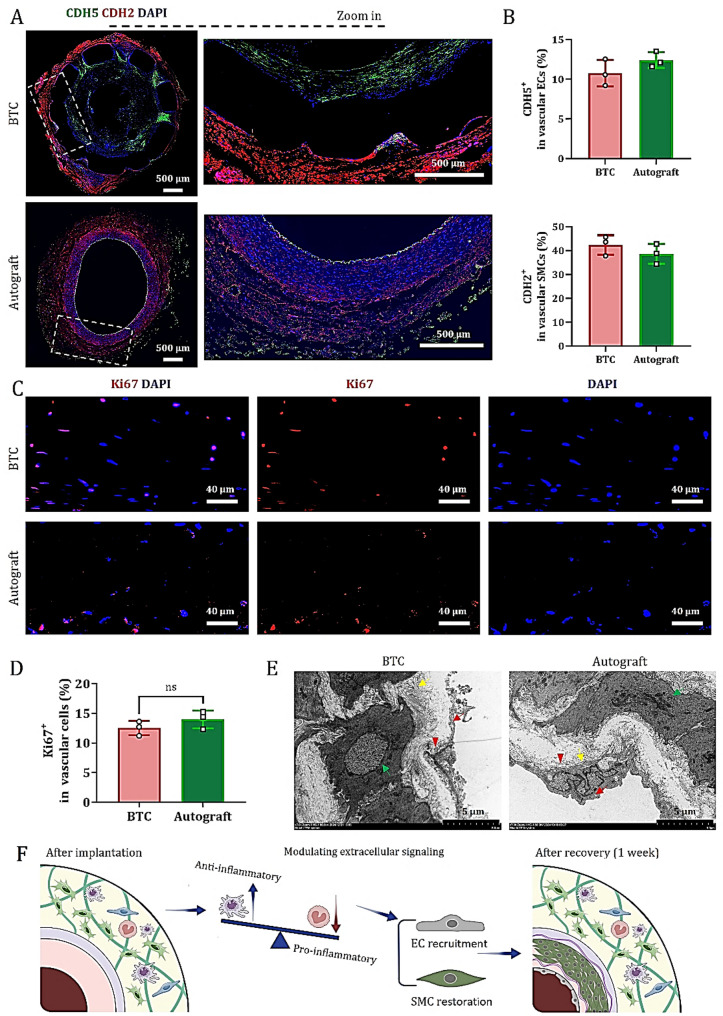

Compensatory activities of immature ECs and SMCs in BTC maintain early vascular function

Immunofluorescence staining results (Fig. 4A) showed that after treatment with BTC and autografts, the newly formed ECs and SMCs had not yet fully matured within the first four weeks. Therefore, how these immature ECs and SMCs maintain vascular barrier integrity and promote vascular remodeling in the early stages of vascular injury repair—before they have fully acquired their mature phenotypes and structural support—has become an important question worth further investigation.

Previous studies have indicated that during this period, the functions of ECs and SMCs mainly rely on their cellular plasticity and dynamic interactions with the microenvironment [19, 24–27]. To explore whether CDH5 in immature ECs and CDH2 in SMCs are involved in maintaining early vascular function, we further investigated their expression patterns.

Immunofluorescence staining of vascular sections at one-week post-surgery revealed that CDH5 and CDH2 were enriched in the luminal and outer layers of BTC, respectively (Figs. 7A and S12-13), with expression levels comparable to those observed in autografts (Fig. 7B). Consistent with the architecture of native blood vessels, autografts display CDH5 immunoreactivity in both the intima and adventitia, while CDH2 is primarily localized in the media. These findings suggest that, although immature ECs in BTC have not yet established fully mature tight junctions (such as those marked by CD31), they can form transient adherents’ junctions via CDH5 on the luminal surface, thereby enabling temporary sealing of the injured vascular site. Meanwhile, immature SMCs may enhance dynamic intercellular connections in the outer layer through CDH2, facilitating cell migration toward the damaged area, filling tissue defects, and initiating new tissue formation.

Fig. 7.

Immature ECs and SMCs in BTC optimize early vascular function through compensatory activities. (A) CDH5 (endothelial adhesion marker) and CDH2 (smooth muscle cell adhesion marker) immunofluorescence staining was conducted on graft cross-sections at 1-week post-implantation. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CDH5⁺ and CDH2⁺ cells (data are mean ± SD, n = 3). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 (a nuclear marker for cell proliferation) in paraffin sections of mid-transverse grafts from each group. (D) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of Ki67⁺ cells (data are mean ± SD, n = 3); ns indicates no statistically significant difference. (E) TEM images of the middle cross-sections of grafts in each group one week after surgery. Green arrow: rER; yellow arrow: adhesion proteins; red arrow: pinocytotic vesicles; red triangle: focal adhesions. (F) Cartoon illustration showing that BTC promotes a pro-regenerative microenvironment at the AA injury site, facilitating host ECs and SMCs migration to enhance early vascular function

Additionally, Ki67 immunofluorescence staining showed that at one-week post-surgery, BTC and autografts recruited approximately (12.7 ± 1.1) % and (14.4 ± 1.3) % proliferative cells, respectively (Fig. 7C and D), indicating that both graft types were undergoing controlled regeneration rather than abnormal proliferation during the early repair phase.

TEM further revealed that in BTC, migrating ECs exhibited predominantly transient junctions, with intercellular gaps ranging from 200 to 500 nm in length. At the interface between the EC basement membrane and ECM, focal adhesions (approximately 1 μm in diameter) were observed, along with abundant pinocytic vesicles in the cytoplasm. Adhesive proteins were found to be orderly deposited beneath the endothelium, while SMCs exhibited well-developed rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER), with gap junctions connecting adjacent myofilaments (Fig. 7E). In contrast, in autografts, the nuclei of migrating ECs in the intima protruded toward the luminal side, and tight junctions were discontinuous, with gaps ranging from 80 to 280 nm; focal adhesions were absent. Adhesive proteins were also orderly deposited beneath the endothelium but were less abundant compared to BTC. Smooth muscle cells in autografts displayed even more developed rER, and the gap junctions between myofilaments were tighter than those in BTC. These observations indicate that tissue regeneration and matrix remodeling in both types of grafts are progressing along normal physiological pathways.

In summary, combined with the data in Fig. 6, these findings indicate that the pro-regenerative immune microenvironment formed by BTC at the injury site supports the compensatory activity of immature endothelial and smooth muscle cells, which is crucial for early vascular function maintenance and functional vascular regeneration (Fig. 7F).

Discussion

Over the past decade, the field of bioengineered vascular grafts has developed various strategies for preparing BTCs to meet the clinical needs of cardiovascular bypass surgery, particularly for small-diameter vessel reconstruction. These strategies include vascular decellularization [14, 28–30], self-assembled cell sheets [8, 16], electrospinning [31–34], cylindrical mandrel deposition [35], and bioprinting [36, 37]etc. Although decellularized vessels and cell sheet technologies have demonstrated favorable patency rates and safety in phase II clinical trials, these traditional methods generally rely on prolonged in vitro culture (4 weeks or longer) and exhibit strong dependency on complex equipment, failing to meet the timeliness requirements for grafts in emergency surgeries [8, 16]. This study demonstrates that leveraging mesenchymal stem cells, monocytes, and fibroblasts abundant in the host subcutaneous microenvironment, and using 3D printed scaffolds as templates for ECM deposition, can significantly accelerate the guidance of fibroblasts to secrete matrix components such as collagen, elastin, and n/aGAGs within 2 weeks, forming BTCs with biomechanical and biochemical properties close to natural blood vessels. Experimental results show that the formed BTCs can be used for vascular bypass surgery similarly to native arteries, gradually integrating host cells at the defect site and inducing the formation of neovascular tissue at an appropriate rate to effectively compensate for the structural and functional loss of damaged arteries, thus achieving arterial tissue regeneration and repair. This process has been described in previous studies on subcutaneous bio-vascular construction based on melt-spun scaffolds [38] and vascular grafts derived from cell sheets [8, 16].

The method using 3D printed scaffolds has a direct impact on the tubular structure and physiological characteristics of BTCs. In clinical scenarios such as coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndrome, peripheral arterial disease, renal artery stenosis, carotid artery stenosis, and complex lesions or restenosis, metallic or degradable hollow scaffolds with good mechanical strength and flexibility are typically implanted into the vessel wall to support the lesion and restore or maintain vascular patency, ensuring normal blood supply to vital organs. However, in the face of long-segment stenosis, complete occlusion, or lesion locations unsuitable for traditional stent implantation, BTCs with biomechanical and biochemical properties closer to autologous vessels exhibit obvious advantages. Our research data show that BTCs constructed by the subcutaneous in-situ self-assembly strategy based on 3D printed hollow tubular scaffolds not only have enhanced mechanical stability but also can generate physiological calcium wave conduction responses under micro-CT electric field stimulation, which is an important marker of functional self-assembly of vessel wall tissues. Additionally, after 24 weeks of in vivo implantation, these BTCs exhibited autonomous vascular reactivity, contractility, and compliance comparable to those of autologous AA transplantation in SD rats. Notably, detailed histology at 24 weeks post-implantation shows BTCs have near-physiological intimal regeneration (1.83 μm thick) with no pathological hyperplasia or abnormal α-SMA+ SMC accumulation—significantly thinner than autologous grafts (5.1 μm), avoiding excessive intimal thickening common in small-diameter grafts. Our quantitative ECM analyses suggest a potential link to scaffold-guided ECM deposition, but this requires further validation via targeted experiments (e.g., scaffold topography manipulation).

The choice of PLA as the 3D printing “ink” is central to promoting the rapid clinical translation of this vascular engineering technology [39]. As the most representative green environmental-friendly polymer material, PLA has been certified by the U.S. FDA and widely used in the medical field, such as absorbable sutures, bone fixation devices, and drug delivery carriers [40]. Its non-toxicity and extremely low immunogenicity provide good biological safety for in vivo implantation. However, long-term immune responses—such as delayed hypersensitivity or antibody-mediated reactions—need evaluation in large animals with more complex immune systems. PLA’s controlled degradation prevents acidic byproduct buildup, and with regulated ECM remodeling, effectively inhibits calcification. MicroCT at 24 weeks showed no calcification in BTCs, highlighting their anti-calcification advantage. Spontaneous calcium imaging and microCT-based electrical stimulation further confirmed functional stability in electrophysiological responses and mineralization control.

By virtue of the digital design advantages of 3D printing technology, the diameter, wall thickness, and length of the scaffold can be rapidly and precisely customized according to the specific anatomical characteristics and lesion conditions of the transplantation site [36, 41]. This personalized construction not only ensures the geometric accuracy of the BTC tubular structure but also can regulate the thickness of the support layer to guide fibroblasts in the host subcutaneous microenvironment to secrete ECM components such as collagen and elastin, gradually reconstructing bioactive tubular tissue structures in vivo [42]. In this “host self-assembly” process, the ECM network formed by in-situ deposition of host cells is closer to the composition and elastic response characteristics of natural blood vessels, effectively avoiding the immune rejection problems possibly caused by traditional in vitro synthesized ECM, while providing the necessary structural stability and mechanical support for BTC to achieve immediate blood flow perfusion. However, the scalability of this in-situ assembly process to human-sized vessels (e.g., coronary arteries with diameters 3–4 mm) remains untested; challenges may include slower ECM deposition kinetics in larger grafts or altered cell recruitment due to species-specific differences in subcutaneous microenvironments.

The in vivo application of BTC as an AA interposition graft provides important evidence for evaluating its feasibility in surgical operation and functional performance. During implantation, BTC showed identical surgical procedures to autologous AA grafts and exhibited comparable suture retention strength. In fact, the number of sutures required for anastomosis was equivalent to that of autologous vascular transplantation, which may be closely related to the composition and arrangement of type I/III collagen fibers and elastin fibers within BTC—these structural features are highly similar to the natural rat AA. Notably, BTC demonstrated superior pro-regenerative capacity to autologous grafts in the early stage of vascular repair, which may be attributed to the following factors: BTC has a slightly higher inner surface roughness than autologous grafts, increasing adhesion sites for circulating monocytes; meanwhile, it lacks the endothelial barrier restriction of autologous grafts. Additionally, BTC carries host subcutaneous monocytes during its subcutaneous self-organization process. In the abdominal aortic defect repair model, BTC and autologous AA as interposition grafts showed no significant difference in blood perfusion and functional performance, further verifying the excellent structural stability and biological functionality of BTC. The BTC grafts constructed in this study have an inner diameter of approximately 2.5 mm, suitable for various clinical scenarios requiring small vessel reconstruction, such as: treating microcoronary lesions in coronary artery bypass grafting, small vessel stenosis in peripheral arterial diseases, renal artery stenosis therapy, vascular repair in cerebrovascular diseases, fine vascular anastomosis in microsurgery, and vascular substitution in congenital heart disease repair for newborns and infants, etc. Notably, these clinical projections stem from rodent data; translation to humans will require validation in preclinical models that better mimic human cardiovascular physiology, including pressure dynamics and immune surveillance.

Furthermore, histological and molecular analyses showed that GAGs are significantly upregulated and M2-polarized macrophages are markedly infiltrated during BTC formation. These findings preliminarily suggest a potential synergistic role of GAGs and macrophages in promoting smooth muscle cell maturation, but this remains a hypothesis lacking direct causal evidence (e.g., macrophage-specific GAG receptor knockout). The underlying mechanisms need further clarification. Given that this study focused primarily on BTC’s overall regenerative performance and clinical feasibility, future studies should dissect the involved molecular pathways via loss-of-function experiments such as enzymatic GAG degradation or macrophage depletion.

The self-assembled cell sheet technology that has entered the phase II clinical stage shows that culturing qualified tissue-engineered blood vessels using patients’ autologous fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells in a physiological pulsatile bioreactor system requires a long time, usually about 3 to 4 months [10, 19, 43, 44]. However, in cardiovascular bypass surgery, it is generally unacceptable to postpone the surgery for months while waiting for the graft to mature. In contrast, the 3D printing strategy proposed in this study enables BTC construction within 2 weeks through host in-situ self-assembly, eliminating the need for complex in vitro operations. This efficiency is attributed to the precise guidance of cellular behavior by the 3D scaffolds—the synergistic effect of fiber orientation and modulus optimizes cellular mechanoresponse and accelerates matrix secretion, as reported in previous study [45]. Decellularization methods are associated with high costs due to reliance on specialized reagents (e.g., Triton X-100) and equipment. Similarly, cell sheet technologies require costly bioreactor maintenance [10, 43]. In contrast, this study employs PLA materials and simplified equipment, reducing raw material costs by approximately 60% compared to traditional methods, while avoiding consumable expenses associated with in vitro culture. The BTC technology based on subcutaneous in-situ self-assembly of 3D printed hollow tubular scaffolds proposed in this study can shorten the preparation time of traditional tissue-engineered blood vessels by approximately 80%, thus completing the construction of vascular grafts within the time window required for cardiovascular bypass surgery and significantly improving its clinical application feasibility. Decellularized vessels have a 1-year patency rate of ~ 65–75% and face challenges with insufficient recellularization [14, 28]. Attempts to compare BTCs with commercial ePTFE grafts were halted due to ethical and practical constraints: the 2 mm inner diameter of adult rat AA mismatched the smallest commercial ePTFE grafts (3 mm), causing acute thrombosis and fatal abdominal hemorrhage in preliminary tests—deemed unnecessary animal suffering by the ethics committee. In contrast, the BTCs in this study maintained 100% patency over 24 weeks, with functional compatibility comparable to autologous vessels. This exceptional patency is closely linked to their anti-thrombotic properties: 1 week post-implantation, electron microscopy showed no luminal thrombi, and immunofluorescence revealed early integration of endothelial and smooth muscle layers (CDH5+, CDH2+); by 24 weeks, complete endothelialization (CD31+, α-SMA+) and intact integration of endogenous monocytes with the smooth muscle layer (CD11b+, SM-MHC+) were observed. While promising in rats, this anti-thrombotic performance may be influenced by species-specific coagulation pathways, requiring validation in large animals with human-like coagulation systems. Potential mechanisms include nanoscale ligand distribution-regulated cell-material interactions [46] and fiber flexibility-mediated host integration [47].

A potential limitation of this study is the use of a rat AA defect model for experiments [29, 34, 38], which constrains certain functional evaluations. Rodent models have inherent limitations, including smaller vascular dimensions (2–3 mm vs. 3–5 mm in human coronary arteries), shorter lifespans limiting long-term safety assessments, and immune systems that differ substantially from humans—factors that may affect graft-host interactions and regenerative outcomes. For instance, burst pressure testing was not performed due to ethical and logistical constraints: the destructive nature of such tests conflicts with the 3R principles (reduction of animal suffering, maximization of sample utility) as emphasized by the Animal Ethics Committee, and the SPF-grade housing requirements for rats—including strict containment within shared university facilities, incompatibility with external testing equipment, and prohibitions on removing animals from controlled environments—rendered the procedure operationally unfeasible. However, throughout the observation period, the tested BTCs achieved a 100% patency rate without any anticoagulant treatment. Additionally, within 24 weeks after implantation, BTCs showed obvious signs of tissue maturation, and their histological structure was highly similar to that of the autologous vascular transplantation group, indicating good long-term revascularization potential. Meanwhile, a stable and orderly tissue repair and regeneration process was observed during implantation, further supporting the clinical translation prospect of this technology in cardiovascular bypass surgery. Based on the above results, future research plans to further evaluate the feasibility of this technology in large animal models, with a focus on optimizing the hollow structure design of the scaffold, mechanical elasticity matching, and overall preparation cycle—including burst pressure testing and direct comparisons with ePTFE and decellularized vessels to address current limitations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this technology shortens the preparation cycle of BTCs for small-diameter arteries to two weeks, enabling their clinical application within the timeframe of elective cardiovascular bypass surgery. Additionally, the method uses only clinically approved biodegradable materials and eliminates in vitro cell manipulation steps, thus simplifying the production process and effectively reducing the complexity and regulatory barriers for technological translation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BTC

Bioengineered tubular vascular construct

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- PLA

Polylactic acid

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- FN

Fibronectin

- CDH5

VE cadherin

- CDH2

N Cadherin

- SM-MHC

Smooth muscle myosin heavy chain aa

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline; DAPI, diamidino-2-phenylindole

- HE

Hematoxylin and eosin

- MTC

Masson’s trichrome

- SR

Sirius red

- VVG

Verhoeff-van gieson

- AB

Alcian blue

- PAS

Periodic acid-schiff

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- NIH

National institutes of health

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- AA

Abdominal aortic

- AFM

Atomic force microscope

- WCA

Water contact angle

- IgG

Immunoglobulin-G

- SAXS

Small-angle X-ray scattering

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- SD

Standard derviation

- ANOVA

A one-way analysis of variance

- nGAGs

Neutral glycosaminoglycans

- aGAGs

Acidic glycosaminoglycans

- SMC

Smooth muscle cell

- EC

Endothelial cell, rER, rough endoplasmic reticulum

- CDU

Color doppler ultrasound

- CT

Computed tomography

Author contributions

SH: Conceptualization, methodologyXS: Data curation, visualization, validationRZ: Investigation, writing—original draftKF: MethodologyYM: ValidationJX: SoftwareSL: Data curationYN: Funding acquisition, writing—review and editingAll authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding