Abstract

Background

Preoperative anxiety is pervasive among patients awaiting surgical procedures and is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications. Music intervention is a promising strategy to alleviate preoperative anxiety levels and is easily implementable even in busy clinical settings. Our objective was to conduct an umbrella review of systematic reviews studying the efficacy of music intervention in reducing preoperative anxiety among adult patients.

Methods

To identify systematic reviews assessing the effects of music intervention on preoperative anxiety in adult surgical patients, we retrieved MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library from inception until 22 August 2024. The primary outcome was to review the overall efficacy of music intervention in reducing preoperative anxiety levels. In addition, specific details regarding the implementation of music intervention were also summarized. We assessed the quality of the included systematic reviews by using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 checklist.

Results

Six eligible systematic reviews (i.e. one high-quality, four moderate-quality, and one low-quality review) analyzing 40 primary studies were included. The reporting on the intervention content and its implementation process was often unsatisfactory, with some key information missing. The pooled results on the reduction of preoperative anxiety using music intervention were statistically significant (MD = -5.20, 95%CI (-6.32, -4.07), I2 = 49%). Subgroup analyses revealed that music intervention had a more pronounced effect when the duration of the intervention was 20 min or longer and in patients younger than 60 years of age.

Conclusion

Music intervention may have a beneficial effect on reducing preoperative anxiety levels. However, to optimize the integration of music intervention into routine clinical practice, high-quality evidence and especially clearer reporting on the implementation methods are required.

Registration

PROSPERO (CRD42022333246).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12871-025-03120-z.

Keywords: Preoperative anxiety, Umbrella review, Systematic review, Surgery, Music intervention

Background

Preoperative anxiety, which manifests as nervousness, worry, or even fear, is pervasive among patients awaiting surgical procedures. Preoperative anxiety is usually characterized by state anxiety symptoms reflecting a temporal and transient emotional state that varies in intensity and occurs in response to environmental stimuli [1, 2]. The global pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety was reported to be 48% in a meta-analysis, whereas the prevalence reported in individual studies fluctuated widely, ranging from 16.7% to 97% [3–5]. High levels of preoperative anxiety have been associated with various intraoperative and postoperative complications, including hemodynamic alterations during anesthetic induction, an increased intraoperative anesthetic requirement, increased postoperative pain, and even a higher incidence of perioperative morbidity and mortality [6–9].

In view of the serious impact of preoperative anxiety, a number of anxiety-reducing protocols have already been implemented prior to surgical procedures, including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies. While anxiolytic agents, particularly benzodiazepines, are commonly prescribed and effective in reducing preoperative anxiety, they paradoxically increase the risk of multiple negative side effects such as postoperative delirium [10]. Therefore, non-pharmacological therapies (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, music interventions, preoperative patient education, massage) have become increasingly popular due to their non-invasive nature and perceived safety in comparison to pharmacological therapies [11–13]. Among all non-pharmacological preoperative anxiety-reducing strategies, music intervention stands out as particularly advantageous due to its non-invasive nature and ease of implementation, even in a busy clinic.

Several proposed mechanisms underlying the effects of music intervention on anxiety and mood disturbances have been reported. The anxiolytic effect of music intervention relies not only on distraction, shifting people’s focus from stressful events or negative stimuli to something enjoyable, but also on the modulation of the autonomic nervous system activity. By suppressing the sympathetic nervous system, music intervention decreases adrenergic activity and reduces neuromuscular arousal, both of which are linked to an acute reduction in stress and anxiety [14, 15]. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying the positive effects remain obscure and need to be further investigated.

Since several related systematic reviews (SR) have already been published, our objective is to provide an overview of the available evidence, assess the overall strength of the evidence, and identify research gaps in the existing literature. To this end, we performed an umbrella review of SRs that analyzed the efficacy of music intervention in reducing preoperative anxiety in surgical patients.

Methods

This umbrella review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (see Additional file 1) [16]. The protocol of this umbrella review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022333246).

Eligibility criteria

We included SRs investigating the effect of music intervention on preoperative anxiety reduction in adult patients (over 18 years of age). The following definitions were used in our review:

Music intervention is an intervention defined as passive or active listening to music administered by medical personnel to meet the physiological or psychological needs of patients in different healthcare areas. This is different from the practice of music therapy, which involves a certified music therapist providing an individually tailored music experience [17].

A SR was defined as a review designed to answer specific research questions by identifying and collecting all primary studies meeting pre-specified eligibility criteria and selecting them using an explicit and systematic process [18]. SRs that did not include a critical appraisal of the included studies were deemed ineligible. To enhance coherence, we excluded SRs that focused on patients undergoing dental surgery.

We considered preoperative anxiety level as the primary outcome, which had to be assessed by validated instruments explicitly stated in the included SRs. Furthermore, no specific threshold (low/high) for the severity of preoperative anxiety was required.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science Core Collection from inception until 22nd of August 2024, using the search terms “preoperative anxiety”, “systematic review”, and “meta-analysis” (see Additional file 2 for the search strategy used for all databases; all search strategies were developed in collaboration with an information specialist from the university library). We also searched the reference lists of the included SRs to discover any additional eligible SRs. Conference abstracts, unpublished studies, and other grey literature were not searched.

Study selection

After removing duplicates with Endnote, all records were imported into Rayyan for further screening. Three reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts via Rayyan and subsequently reviewed the full text of all potentially eligible studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the supervisor of the research team.

Overlap of systematic reviews

A citation matrix was developed to assess the degree of overlap among the included SRs by calculating the corrected covered area (CCA) [19, 20]. The citation matrix consisted of all primary studies (rows) included in the SRs (columns), with the inclusion of a primary study in a particular SR indicated by a cross mark. CCA, expressed as a percentage, was calculated as (N − r)/(rc − r), where N is the total number of publications included in evidence synthesis (i.e., the total number of times primary studies appeared across all SR, including double counting), r is the number of rows (i.e., the number of primary studies), and c is the number of columns (i.e., the number of SRs). The degree of overlap was classified as very high (CCA > 15%), high (CCA 11–15%), moderate (CCA 6–10%), or light (CCA 0–5%) [20].

We calculated the CCA across the entire matrix and looked for the SRs with complete/nearly complete overlap in their inclusion of primary studies. SRs with low or no overlap were analyzed directly. SRs with a high CCA score were compared by examining multiple sources, including research question definitions (i.e., participants, intervention, comparison, and outcomes); search and study selection strategies; and meta-analysis results, if available, etc.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed and pre-tested to extract data from the eligible SRs and the primary studies. Two reviewers (KLY and MMN) independently extracted data using the extraction form, compared their extracted data, and resolved disagreements through discussion. The third reviewer, the supervisor of the research team (KM), was actively involved when there was any discrepancy between the two reviewers, and after further discussion with him, a final decision was made.

We extracted the following data from the SRs: (a) bibliographic details (first author, year of publication, and study type); (b) participant demographics (sample size, age, gender, surgery type, etc.); (c) outcomes, including preoperative anxiety and relevant physiological outcomes reported in the included SRs (outcome and measurement, synthesis model, effect size, pooled effect and 95% confidence intervals, heterogeneity, results of quality assessment, limitations, etc.).

To acquire comprehensive information on the intervention implementation, we also extracted the following data from the primary studies: (a) bibliographic details (first author, year of publication, and study type); (b) participant demographics (sample size, age, gender, surgery type, etc.); (c) intervention characteristics (a rationale for intervention, intervention content, delivery schedule, interventionist, treatment fidelity, and setting); (d) outcomes (measurement instrument, post-intervention scores, change scores (i.e., change-from-baseline scores, if post-intervention scores were not available)).

Quality assessment

We used A MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2) checklist [21] to assess the quality of the included SRs. The AMSTAR 2 checklist contains 16 items for assessing the quality of systematic review, with seven items recognized as critical domains. Each item was evaluated as “yes”, “partly yes”, and “no”. Three items (statistical methods in meta-analysis, bias influence, and publication bias assessment) were not applicable for systematic reviews without meta-analysis. The overall quality was classified as high, medium, low, and very low according to the guide of AMSTAR 2 [21]. Two reviewers (KLY and MMN) independently assessed the quality of the included SRs, and any discrepancies resolved through discussion. The third reviewer (KM), was actively involved to make final decisions when discrepancies arose between the other two reviewers.

To strengthen the robustness of the meta-analysis, we collected the quality assessment results of the primary studies included in the eligible SRs regarding the critical item (i.e., random sequence generation). We then checked for consistency to determine whether the primary studies were included in more than one SR. If the quality assessment results were not consistent, two reviewers independently re-assessed the random sequence generation of those primary studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [22], and any discrepancies were solved by discussion.

Data synthesis and analysis

First, we conducted a narrative synthesis of the basic characteristics and findings of the included SRs. The intervention details were summarized in a Mind map via Microsoft Visio (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA). Descriptive statistical analyses, i.e., frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviation, were used to present the study results and quality assessments.

Updated meta-analyses were performed including all primary studies in the SRs that were eligible for meta-analyses using R software version 4.6.3 (RStudio, Boston, MA). Estimates were pooled according to the Mantel–Haenszel random-effects model. Effect sizes were reported as mean difference (MD) standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used MD for pooling post-intervention scores and change scores when anxiety scores were measured using same instrument, as it allowed for the combination of most studies and provided a direct interpretation of the intervention effect [18]. Additionally, we used SMD for pooling post-intervention scores when different anxiety measurement instruments were used, ensuring comparability across studies. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to test the stability of the results of the meta-analyses by excluding non-randomized and inadequately randomized trials. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic with I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% categorized as low, moderate, and high, respectively [23]. We performed subgroup analyses when there was at least one subgroup with two or more studies based on the following factors: study type, content of intervention, delivery methods, surgery/procedure type, and the age of the patients (as a categorical factor using a cut-off value of 60 years for older age). We conducted visual inspection of the funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s test to assess publication bias for any meta-analysis that included at least 10 studies, with a P value < 0.05 indicating the presence of publication bias [24]. A comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the difference in the reduction of preoperative anxiety levels among various intervention contents when a subgroup difference was identified (P < 0.05). We used the “gemtc” package in R (version 4.6.3) to perform a network meta-analysis using a multivariate consistency model with random effects, generating pooled MD with 95% CI. We used surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) curves to rank the intervention content, which was expressed as a percentage, with a higher SUCRA value suggesting a greater probability of the intervention content being more effective. All results were listed in a league table.

Results

Search results

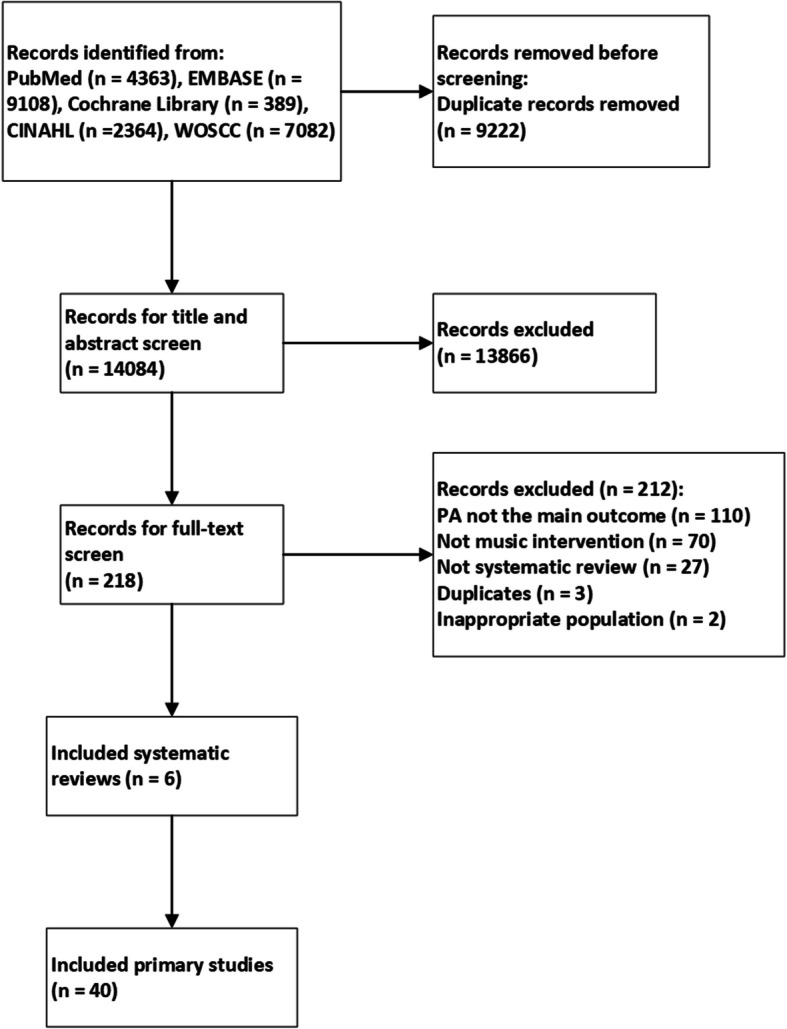

We identified 23,306 records by searching the electronic databases, and we screened the full text of 218 manuscripts after removing duplicates and screening the titles and abstracts. Ultimately, we included six SRs [15, 25–29] encompassing 40 primary studies, while excluding 212 manuscripts for specified reasons (see Fig. 1). No additional eligible SRs were identified from the reference lists of the included SRs.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of literature screening. Legend: CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; WOSCC: Web of Science Core Collection; PA: preoperative anxiety

Characteristics of the included SRs

The included SRs were published from 2008 to 2023 and consisted of 1 to 25 primary studies that reported preoperative anxiety levels and relevant outcomes, with sample sizes ranging from 159 to 2,051. All the SRs included RCTs and quasi-experimental studies or non-randomized controlled trials. Meta-analyses were conducted only in one SR [15], while the rest consisted solely of narrative syntheses. Five SRs only examined music intervention [15, 26–29] while one examined non-pharmacological interventions in general, including music intervention [25]. The surgery type was not restricted in three SRs [15, 26, 28], while the remaining three SRs specified the surgeries, i.e., cranial or spinal neurosurgery [27], breast cancer surgery [25], or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery [29]. Outcomes included in the eligible SRs contained preoperative anxiety levels and relevant physiological health outcomes. Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of the included SRs. Seven instruments to assess preoperative anxiety levels were identified in the included SRs, with the most frequently used instruments being the state subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) [30] and the Visual Analogue Scale for anxiety (VAS-A) [31].

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included systematic reviews

| Study ID | Surgery types | Age(yrs)/number of included studiesb/Sample size | Study types included | Outcomes | Instrument for PA assessment | Risk of bias tools | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradt 2013a | no restriction | 48.74c/26/2051 | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | PA; HR; BP; RR; ST; SC; BG | STAI-S, VAS, NRS, SAS | Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool-1 | Music listening may have a beneficial effect on preoperative anxiety |

| Gillen 2008 | no restriction | 18–99d/11/1072 | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | PA; WB; BP; HR; RR; BG; SV; CO | STAI-S, VAS, POMS | JBI checklists for RCTs and quasi-experimental design studies | It is likely that patients will benefit psychologically from having the opportunity to listen to music in the immediate pre-procedural period |

| Ng Kee Kwong 2022 | cranial or spinal neurosurgery | 46.5–62.2d/3/159 | RCTs, quasi-RCTs, and qualitative study | PA; HR; RR; BP | VAS, BAI | Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool | This study suggests a potential role for music intervention in perioperative neurosurgical management, particularly for relieving anxiety and pain |

| Tola 2021 | breast cancer surgery | 47–54d/3/273 | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | PA; AR; SA | STAI-S, VAS | JBI checklists for RCTs and quasi-experimental design studies | Music appeared to be effective for reducing preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing breast cancer surgery |

| Wandl 2022 | no restriction | 32–53.66d/7/842 | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | PA; HR; BP | STAI-S, VAS; SAS; MSS | CONSORT 2010 Checklist | Music intervention can strengthen the patient’s wellbeing before surgical procedures and reduce anxiety |

| Wu 2023 | CABG surgery | 56.3/1/60 | RCT | PA | STAI-S | Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool-1 | Music therapy is valuable as a low-technology intervention and a very cost-effective way to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing CABG |

RCTs randomized controlled trials, quasi-RCTs quasi-randomized controlled trials, JBI Joanna Briggs Institute, CONSORT Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, PA preoperative anxiety, HR heart rate, BP blood pressure, RR respiratory rate, ST skin temperature, SC salivary cortisol, BG blood glucose, WB well-being, SV stroke volume, CO cardiac output, AR anesthesia requirements, SA satisfaction, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, STAI-S State Anxiety scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, VAS Visual Analogue Scales, NRS Numerical Rating Scales, SAS Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, POMS Profile of Mood States, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory, MSS Mood States Scale

aSR conducting meta-analysis;

bPrimary studies reported preoperative anxiety and relevant outcomes

cMean age

dRange of the mean age reported in each primary studies

Quality assessment

One SR [18] was rated as high in quality, four SRs [27–29, 31] were rated as moderate in quality, and one SR [30] was rated as low in quality. The results of the quality assessment are listed in Additional file 3. The low-quality SR failed to report on two of the seven critical domains: it failed to state that the methodology was established prior to conducting the SR, and it did not account for the risk of bias in individual studies when interpreting the results. The quality assessment results of the primary studies extracted from the included SR are listed in Additional file 4.

Overlap in systematic reviews

Low overall overlapping association was found in the six SRs (CCA = 5%). However, a high overlap was found between Bradt 2013 [15] and Gillen 2008 [26] (CCA = 12%). The participants and interventions described in Gillen 2008 [26] and Bradt 2013 [15] were broadly similar with both investigating the effect of music interventions on preoperative anxiety in adult patients. Bradt 2013 [15] did include more primary studies due to its broader inclusion criteria, later literature search time, and more explicit screening and selection process. More details are included in Additional file 4.

Details of interventions

Most of the included SRs reported detailed information on the interventions of the included primary studies to some extent, e.g., regarding the number of sessions, genre of music, duration of each session, delivery method, implementation time, and other related information. Because there was much variation across primary studies concerning these aspects, the key information on music intervention is comprehensively described in Additional file 5, and summarized in Fig. 2, which presents the most commonly reported intervention components included in the studies.

Fig. 2.

Summary of interventions details of music intervention. Legend: This figure summarizes the details of the most reported content on music intervention. The most reported duration was 20 min, with a single session being the norm, and the most reported delivery method was headphone, typically administered on the day of surgery, and classical music was the most provided genre

Almost all studies utilized pre-recorded music [32–70], except for one study [71] which offered live music therapy and was therefore not included in the following analysis; one study [63] that offered both pre-recorded and live music to patients, but only the data from pre-recorded music was used. Most of the studies offered one session of music intervention before surgery [32–46, 48–51, 54–70]. The most frequently reported duration of music intervention was 20 min [38, 40–43, 46, 48, 49, 56, 57, 61, 62, 65], delivered via headphones [32, 34, 38–40, 43–48, 50, 51, 56, 58, 60, 62–65, 69]. Among a total of 17 genres that have been reported, classical music is the most commonly used music genre [32–36, 39, 45, 49, 52, 53, 58, 61, 64, 66, 67, 70]. Only 12 studies clarified the rationale behind music selection, with the main rationale being that music with a slow tempo and regular rhythm was considered to facilitate relaxation and decrease anxiety [35, 46, 50, 57, 58, 61, 62]. Eight studies reported the involvement of music therapists or musicians in music selection (i.e., checking the selected music or compiling the music lists) [35, 40, 45, 57, 61–64].

The music tempo was documented in seven studies with four studies [35, 47, 50, 51] reporting a range of 60–80 beats per minute (bpm), two studies reporting 60–72 bpm [38, 53], and one study reporting 70–80 bpm [46]. Two studies mentioned that music volume was controlled at 50–55 dB [50, 51] and another at 25–30 dB [64]. In most studies, patients could select their preferred music from a list of music offered by the researchers [32–36, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45, 47, 51–58, 60–63, 66, 67, 69, 70]. Two studies allowed patients to listen to their personal music lists [37, 44], while nine studies only allowed patients to listen to the playlist selected by the researchers [40, 43, 46, 48–50, 59, 64, 65].

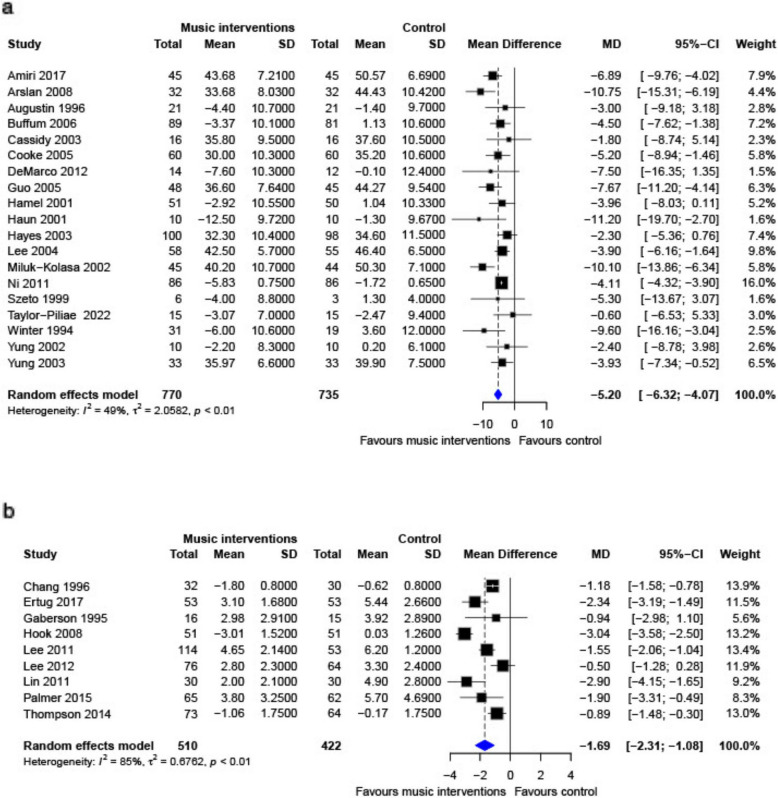

Meta-analyses for preoperative anxiety

The following meta-analyses were based on data from 30 primary studies drawn from the six SRs examining the effects of music intervention on preoperative anxiety levels. First of all, the meta-analysis of 19 primary studies that used STAI-S showed that patients who received music intervention had lower preoperative anxiety levels than those who did not (MD = −5.20, 95%CI (−6.32, −4.07), I2 = 49%, n = 19) (Fig. 3a). Similar findings were found in sensitivity analyses, in which we excluded non-randomized and inadequately randomized trials (MD = −4.95, 95%CI (−6.50, −3.41), I2 = 45%, n = 7) and studies showing much larger beneficial effects than others (i.e., Arslan 2008 [33], Haun 2001 [65], Winter 1994 [60], and Miluk-Kolasa 2002 [54]; MD = 4.12, 95%CI (−4.33, −3.92), I2 = 0, n = 15). Although the funnel plot (Additional file 6) showed a slight asymmetry, Egger’s test (t = −1.90, df = 17, p = 0.07), suggested no significant evidence for publication bias.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of music intervention on preoperative anxiety levels Legend: a Forest plot for meta-analysis of music intervention on preoperative anxiety levels (only state subscale of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory); b Forest plot for meta-analysis of music intervention on preoperative anxiety levels (only Visual Analogue Scale)

The results of the subgroup analysis are listed in Table 2. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) in the subgroup analysis were found for different durations of music intervention (i.e., less than 20 min, 20 min, and longer than 20 min). Music interventions of 20 min or longer managed to reduce preoperative anxiety levels, with intervention longer than 20 min proving the most effective. A detailed comparison of the three different music intervention durations is summarized in Additional file 7. In addition, patients younger than 60 years of age appeared to benefit more from music intervention than patients aged 60 or older (test for subgroup differences p = 0.03). Furthermore, patients undergoing surgical procedures seemed to benefit more from music intervention in reducing preoperative anxiety compared to patients receiving other medical procedures, such as cardiac catheterization, arthroscopy, and biopsy (test for subgroup differences p = 0.03). No statistically significant subgroup difference was detected between patients listening to music selected by the researchers and those choosing their own music (p = 0.28).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses results for music interventions on preoperative anxiety level

| Subgroup analyses | Effect size | I2 | Number of studies | Subgroup differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative anxiety (STAI-S) | ||||

| Study type | p = 0.16 | |||

| RCT | MD = −4.49, 95%CI (−5.42, −3.57) | 23% | 12 | |

| CCT | MD = −6.74, 95%CI (−9.72, −3.77) | 54% | 7 | |

| Age | p = 0.03 | |||

| less than 60 years old | MD = −6.02, 95%CI (−7.58, −4.46) | 61% | 14 | |

| more than 60 years old | MD = −3.45, 95%CI (−5.22, −1.68) | 0% | 4 | |

| Duration | p < 0.01 | |||

| more than 20 min | MD = −7.25, 95%CI (−9.31, −5.20) | 56% | 7 | |

| 20 min | MD = −4.11, 95%CI (−4.32, −3.91) | 0 | 7 | |

| less than 20 min | MD = −2.95, 95%CI (−4.91, −0.98) | 0 | 4 | |

| Music selection | p = 0.28 | |||

| Research selected | MD = −6.36, 95%CI (−8.56, −4.17) | 0 | 4 | |

| Patient selected | MD = −4.96, 95%CI (−6.21, −3.72) | 51% | 15 | |

| Surgery type | p = 0.03 | |||

| Surgery | MD = −6.06, 95%CI (−7.70, −4.43) | 59% | 13 | |

| Medical procedure | MD = −3.71, 95%CI (−5.14, −2.27) | 3% | 6 | |

| Preoperative anxiety (VAS-A) | ||||

| Duration | p = 0.53 | |||

| more than 20 min | MD = −2.25, 95%CI (−3.83, −0.66) | 93% | 3 | |

| 20 min | MD = −1.57, 95%CI (−2.48, −0.66) | 67% | 3 | |

| less than 20 min | MD = −1.25, 95%CI (−2.05, −0.44) | 64% | 3 | |

| Music selection | p = 0.17 | |||

| Research selected | MD = −1.23, 95%CI (−1.73, −0.73) | 30% | 3 | |

| Patient selected | MD = −1.95, 95%CI (−2.85, −1.05) | 89% | 6 | |

| Sessiona | p < 0.01 | |||

| 1 session | MD = −1.30, 95%CI (−1.72, −0.88) | 56% | 7 | |

| 2 sessions | MD = −3.02, 95%CI (−3.52, −2.52) | 0 | 2 | |

STAI-S State anxiety subscale of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, VAS-A Visual Analogue Scale for anxiety, MD mean difference, CI confidence interval

aThe study that provided 8 sessions of music to patients (Lin 2011) were not included in this subgroup analysis

The pooled results of primary studies using VAS-A (MD = −1.69, 95%CI (−2.31, −1.08), I2 = 85%, n = 9, see forest plot in Fig. 3b), and the results of the sensitivity analysis were stable when excluding inadequately randomized trials (MD = −2.01, 95%CI (−3.04, −0.98), I2 = 82%, n = 4) and studies showing much larger beneficial effects than others (i.e., Hook 2008 [47] and Lin 2011 [53]; MD = −1.30, 95%CI (−1.72, −0.88), I2 = 56%, n = 7). The subgroup analysis did not show statistically significant subgroup differences for different durations (p = 0.53) and music selection (p = 0.17), while the preoperative anxiety reduction in patients receiving two sessions of music was greater than in patients receiving only one session (test for subgroup differences p < 0.01) Further details of the subgroup analysis on VAS-A are available in Table 2.

The pooled result of primary studies that reported post-intervention scores, regardless of the instruments used (i.e., STAI-S, VAS-A, or Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale), also demonstrated the anxiety-reducing effect of music intervention (SMD = −0.71, 95%CI (−0.92, −0.49), I2 = 79%, n = 20, see forest plot in Additional file 8). A stable result was obtained when excluding non-randomized and inadequately randomized trials (SMD = −0.45, 95%CI (−0.70, −0.19), I2 = 70%, n = 7).

Physiological outcome measures

Physiological outcomes related to preoperative anxiety were descriptively depicted in five SRs [15, 25–28] and were pooled for meta-analysis in only one SR [29].

The differences between the intervention and control groups were statistically significant for heart rate (HR, MD = −2.50, 95%CI (−4.18, −0.81), I2 = 74%, n = 20) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP, MD = −1.98, 95%CI (−3.43, −0.54), I2 = 76%, n = 17), but not for systolic blood pressure (SBP, MD = −4.01, 95%CI (−9.95, 1.94), I2 = 97%, n = 18). However, excluding studies with inadequate randomization changed the results of the meta-analysis for both HR and DBP from significant to non-significant. Regarding heart rate variability (HRV), the meta-analysis showed evidence that music intervention affected the low to high frequency (LF/HF) ratio (MD = −0.60, 95%CI (−0.99, −0.21), I2 = 55%, n = 4), which is one of the measurements for HRV. Furthermore, music intervention was not able to significantly reduce respiratory rate (RR, MD = −0.58, 95%CI (−1.54, 0.38), I2 = 95%, n = 9), which was further confirmed by the sensitivity analysis excluding studies with inadequate randomization. More results are listed in Additional file 8.

Other less frequently reported physiological outcomes, including salivary cortisol [45], blood glucose level [55], stroke volume [55], cardiac output [55], and skin conductivity response [45] also proved to be significantly reduced in the music intervention group. For skin temperature – included in two studies – the results were inconsistent, with one study reporting a statistically significant increase in skin temperature in the music intervention group, while the other study found no difference between intervention and control groups [45, 55].

Discussion

Main findings

This umbrella review synthesizes the results of previous SRs and updates the meta-analyses on the effect of music intervention on reducing preoperative anxiety in adult patients. Overall, music intervention seems to have a significant anxiolytic effect on patients before surgery. The results of the subgroup analyses suggest that extending the duration of music intervention to 20 min or more may yield better outcomes in reducing preoperative anxiety levels; and patients younger than 60 years of age may benefit more from music intervention in comparison to older patients. However, no conclusive evidence was found regarding the effect of music intervention on physiological responses, except for a small effect on reducing HR and DBP.

Intervention reporting

Complete and transparent reporting of the intervention is one of the prerequisites for a good clinical study and could improve the comparability of outcomes across diverse clinical settings. Unfortunately, many included studies lacked detailed protocols for music delivery, potentially diminishing confidence in applying this intervention and affecting its effectiveness in practice. Only a few primary studies comprehensively described the intervention including the rationale for music selection [35, 46, 50, 57, 58, 61, 62], the volume and tempo of the music [35, 38, 46, 47, 50, 50, 51, 51, 53, 64], the specific timing of the implementation [32, 35, 45, 48, 51, 53, 56, 58, 62, 67, 71], and the settings [41, 51, 53, 55, 59, 61, 67]. Additionally, very few studies outlined the strategies employed to ensure that the interventions were delivered as intended [47, 58]. Inadequate reporting of treatment fidelity hinders the accurate assessment of music intervention efficacy, as clear descriptions are essential for ensuring interventions are delivered as intended and for accurately interpreting the study outcomes [72]. A prior systematic review of music intervention research in healthcare also emphasized the insufficient reporting of treatment fidelity strategies [73]. The Checklist for Reporting Music-Based Interventions provides a structured framework that could improve the reporting quality, rigor and clinical relevance of future research in this field [74].

Interpretation of the results

The conclusions of the included SRs have clearly showed that music intervention has a beneficial effect on reducing preoperative anxiety in adult surgical patients and highlights its potential as a non-pharmacological approach for alleviating anxiety prior to surgery in clinical settings. However, the quality of the included SRs was unsatisfied, with only one SR being of high quality, which may limit the confidence in the conclusions. Additionally, the moderate to high heterogeneity among the included studies in the meta-analysis suggests that the results should be interpreted with caution.

Regarding the duration of music intervention, we found that music intervention may effectively reduce preoperative anxiety when its duration is 20 min or longer. Nevertheless, lacking direct pairwise comparisons among most primary studies may limit the strength of this evidence. An RCT found no significant difference between a 30-min and a 15-min music session on reducing preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing ambulatory surgery [75]. Regarding music preference, the difference between patient-selected music and researcher-selected music did not prove statistically significant in our meta-analysis, aligning with findings from an RCT investigating the effects of patient-selected music versus predetermined music on patient anxiety before gynecological surgery [76]. Conversely, another meta-analysis suggested that patient-selected music was more effective in reducing preoperative anxiety. However, similar to our meta-analysis, it lacked direct comparative data to support a definitive conclusion [77]. In terms of the number of sessions, two sessions of music intervention showed greater effectiveness in reducing preoperative anxiety compared to a single session. This finding seems to be consistent with another study which found that longer or repeated exposure to music therapy was associated with lower anxiety levels, although it focused on anxiety in general rather than preoperative anxiety specifically [78]. Hence, more direct comparative studies are needed to substantiate the effectiveness of specific components of music intervention in different contexts.

Patients under 60 seemed to benefit more from music intervention than older patients, possibly due to differences in general health status and their response to music intervention. Older patients were more frequently confronted with complex and multifaceted health challenges and hearing impairments, which can affect the efficacy of music interventions [79]. Unfortunately, none of the primary studies with an average participant age of over 60 years took into account the effect of potential hearing impairments. Older individuals tend to exhibit more stable emotional experiences and have effective coping strategies, enhancing emotional regulation and mitigating the impact of negative events [80, 81]. Besides, age-related reductions in parasympathetic activity may counteract the calming effects of music intervention [82–84]. Regarding the levels of invasiveness of the procedures, music intervention may be more pronounced in patients undergoing surgery than in those undergoing medical procedure, possibly due to the more significant physical trauma and recovery challenges associated with surgery. It is important to acknowledge that the limited number of studies as well as the small sample size in the subgroup analyses might increase the probability of finding positive results by chance alone.

We could not draw a firm conclusion regarding patients’ physiological responses to preoperative music listening due to inconsistent results across studies. Variations in outcomes reporting, with some studies providing absolute values and others reporting baseline changes, may contribute to this uncertainty. We pooled results using MD to include as many results as possible and conducted sensitivity analyses, but moderate to high heterogeneity were observed, suggesting cautious interpretation. Additionally, the mild decrease in heart rate in the music intervention group may not be clinically significant.

Limitations and strengths

The comprehensive search strategy and the use of the AMSTAR 2 tool guaranteed the comprehensiveness and objectivity of the evidence. In addition, the PRISMA guidelines were followed to guarantee adequate reporting.

Nevertheless, some limitations need to be considered. First, more recent primary studies may not be included, as we did not update the retrieval of relevant primary studies. Second, moderate to high heterogeneity was found in the meta-analyses. Despite excluding SRs that did not clearly distinguish preoperative anxiety from anxiety in other perioperative phases, the heterogeneity was still noticeable. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses could not identify the source of this heterogeneity. Therefore, we have considered the heterogeneity and the limited statistical power of the analyses when interpreting the results and drawing conclusions. Additionally, while we considered baseline confounders between the groups and used change scores in studies with substantial baseline differences, the absence of randomization may still introduce unobserved confounders. To address this concern, we have conducted subgroup and sensitivity analyses regarding study types and randomization adequacy to strengthen the confidence of the results. However, excluding non-randomized studies might enhance the internal validity of the obtained results but potentially limit the generalizability. Additionally, the overall overlap in our umbrella review was low, though a high overlap was observed between two SRs. To minimize this, our primary results were derived from individual primary studies, reducing the impact of overlap on the main outcomes. However, this approach has certain limitations. Compared to other methodological approaches dealing with overlap in primary studies across SRs, it is more resource intensive and may not always be feasible [85]. Finally, although the funnel plot and Egger’s test did not indicate significant evidence for publication bias, our findings depended on the eligibility criteria of the included SRs, which might introduce the potential influence of publication bias.

Implications for future research

We believe that, especially in busy clinical settings, music intervention has a high potential to reduce preoperative anxiety in adult surgical patients. While this umbrella review has demonstrated the effectiveness of music intervention, there remains a need for more rigorously designed clinical trials with detailed methodologies. Such trials should provide high-quality and well-powered evidence to facilitate comprehensive comparisons of intervention components and contribute to the establishment of practical guidelines for music intervention [86, 87]. Finally, and most importantly, the effect of music intervention is closely tied to the characteristics of the targeted populations, including listening ability, type of surgery, age, etc. Therefore, it is worth implementing music intervention protocols tailored to patients of interest, as this may allow the interventions to achieve their full potential.

Conclusion

Evidence from this umbrella review suggests that music intervention is a promising strategy to efficiently reduce preoperative anxiety levels in adult surgical patients. However, to further refine the intervention components and the implementation process, improvements are needed in both the reporting and the methodological quality of primary studies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Krizia Tuand (KU Leuven Libraries - 2Bergen – Learning Centre Désiré Collen, Leuven, Belgium) for her support with the development of the literature searches, and Yabin Zhang for her support with the literature screening.

Abbreviations

- PA

Preoperative anxiety

- CNS

Central nervous system

- SR

Systematic review

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CCA

Corrected covered area

- AMSTAR 2

MeaSurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews checklist

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

- MD

Mean difference

- CI

Confidence intervals

- STAI

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- VAS

Visual Analogue Scale

- SUCRA

Surface under the cumulative ranking

- SAS

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale

- HRV

Heart rate variability

- HR

Heart rate

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

Authors’ contributions

KLY contributed to the original idea; study design; literature screening; data collection; data analysis; interpretation of data; and drafting and revising of the manuscript. ED contributed to the original idea; study design; interpretation of data; and revising of the manuscript. MMN contributed to literature screening and data collection. DFH contributed to the study design and revising of the manuscript; JHT contributed to the study design and revising of the manuscript. SR contributed to the original idea; study design; interpretation of data; and revising of the manuscript; KM contributed to the original idea; study design; interpretation of data; revising of the manuscript and supervision of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

KLY was supported by Chinese Scholarship Council No. 202106180027 (for supporting her Ph.D. studies, not as research funding).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ren A, Zhang N, Zhu H, Zhou K, Cao Y, Liu J. Effects of preoperative anxiety on postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery: A prospective observational cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang K-L, Detroyer E, Van Grootven B, Tuand K, Zhao D-N, Rex S, et al. Association between preoperative anxiety and postoperative delirium in older patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majumdar JR, Vertosick EA, Cohen B, Assel M, Levine M, Barton-Burke M. Preoperative Anxiety in Patients Undergoing Outpatient Cancer Surgery. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6:440–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeb A, Hammad AM, Baig R, Rahman S. Pre-Operative Anxiety in Patients at Tertiary Care Hospital, Peshawar. Pakistan. South Asian Res J Nurs Health Care. 2019;2:76–80.

- 5.Abate SM, Chekol YA, Basu B. Global prevalence and determinants of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg Open. 2020;25:6–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim W-S, Byeon G-J, Song B-J, Lee HJ. Availability of preoperative anxiety scale as a predictive factor for hemodynamic changes during induction of anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;58:328–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maranets I, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1346–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stamenkovic DM, Rancic NK, Latas MB, Neskovic V, Rondovic GM, Wu JD, et al. Preoperative anxiety and implications on postoperative recovery: what can we do to change our history. Minerva Anestesiol. 2018;84:1307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JB, Alexander KP, Morin J-F, Langlois Y, Noiseux N, Perrault LP, et al. Preoperative anxiety as a predictor of mortality and major morbidity in patients aged >70 years undergoing cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:137–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassie GM, Nguyen TA, Kalisch Ellett LM, Pratt NL, Roughead EE. Preoperative medication use and postoperative delirium: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang R, Huang X, Wang Y, Akbari M. Non-pharmacologic Approaches in Preoperative Anxiety, a Comprehensive Review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:854673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz Hernández C, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Pradas-Hernández L, Vargas Roman K, Suleiman-Martos N, Albendín-García L, et al. Effectiveness of nursing interventions for preoperative anxiety in adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:3274–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jlala HA, Bedforth NM, Hardman JG. Anesthesiologists’ perception of patients’ anxiety under regional anesthesia. Local Reg Anesth. 2010;3:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrary JM, Altenmüller E. Mechanisms of Music Impact: Autonomic Tone and the Physical Activity Roadmap to Advancing Understanding and Evidence-Based Policy. Front Psychol. 2021;12:727231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradt J, Dileo C, Shim M. Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. 2013;(6):Cd006908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Music Therapy Association. What is music therapy?. 2005. https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/. Accessed 13 Sept 2024.

- 18.Higgins JPT GS (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. 2011.

- 19.Pieper D, Antoine S-L, Mathes T, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennessy EA, Johnson BT. Examining overlap of included studies in meta-reviews: Guidance for using the corrected covered area index. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11:134–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tola YO, Chow KM, Liang W. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30:3369–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillen E, Biley F, Allen D. Effects of music listening on adult patients’ pre-procedural state anxiety in hospital. 2008;6:24–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng Kee Kwong KC. Kang CX, Kaliaperumal C. The benefits of perioperative music interventions for patients undergoing neurosurgery: a mixed-methods systematic review. Br J Neurosurg. 2022;36:472–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wandl B, Flörl A. Music as a nursing intervention for preoperative anxiety. Pflegewissenschaft. 2022;24:36–47. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu L, Yao Y. Exploring the effect of music therapy as intervention to reduce anxiety pre- and post-operatively in CABG surgery: A quantitative systematic review. Nurs Open. 2023;10:7544–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spielberger CD, Gonzalez-Reigosa F, Martinez-Urrutia A, Natalicio LFS, Natalicio DS. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Interam J Psychol. 1971;5:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hornblow AR, Kidson MA. The Visual Analogue Scale for Anxiety: A Validation Study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1976;10:339–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen K, Golden LH, Izzo JL, Ching MI, Forrest A, Niles CR, et al. Normalization of hypertensive responses during ambulatory surgical stress by perioperative music. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arslan S, Ozer N. Ozyurt F. Effect of music on preoperative anxiety in men undergoing urogenital surgery. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;26:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Augustin P, Hains AA. Effect of music on ambulatory surgery patients’ preoperative anxiety. AORN J. 1996;63:750, 753–750, 758. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Bringman H, Giesecke K, Thörne A, Bringman S. Relaxing music as pre-medication before surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:759–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buffum MD, Sasso C, Sands LP, Lanier E, Yellen M, Hayes A. A music intervention to reduce anxiety before vascular angiography procedures. J Vasc Nurs. 2006;24(3):68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassidy L. The effect of self-selected music on elective surgical patients’ preoperative anxiety. Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Edwardsville; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang Y, Huang SL, Lee MB, Shiu ST, Liao WS. EJects of music therapy on preoperative stress in patients facing open heart surgery. Chinese Psychiatry. 1996;10:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooke M, Chaboyer W, Schluter P, Hiratos M. The effect of music on preoperative anxiety in day surgery. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeMarco J, Alexander J, Nehrenz G Sr, Gallagher L. The Benefit of Music for the Reduction of Stress and Anxiety in Patients Undergoing Elective Cosmetic Surgery. Music Med. 2012;4:44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ertuğ N, Ulusoylu Ö, Bal A, Özgür H. Comparison of the effectiveness of two different interventions to reduce preoperative anxiety: A randomized controlled study. Nurs Health Sci. 2017;19:250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans MM, Rubio PA. Music: a diversionary therapy. Todays OR Nurse. 1994;16:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaberson KB. The effect of humorous and musical distraction on preoperative anxiety. AORN J. 1995;62(5):784-8,790–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganidagli S, Cengiz M, Yanik M, Becerik C, Unal B. The effect of music on preoperative sedation and the bispectral index. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(1):103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo J, Wang J. Study on individual music intervention to reduce preoperative anxiety on patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Chin J Nurs. 2005;40:485–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamel WJ. The effects of music intervention on anxiety in the patient waiting for cardiac catheterization. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hook L, Songwathana P. Petpichetchian W. Music therapy with female surgical patients: effect on anxiety and pain. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res Thail. 2008;12(4):259–71. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jadavji-Mithani R, Venkatraghavan L, Bernstein M. Music is beneficial for awake craniotomy patients: a qualitative study. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42(1):7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaempf G, Amodei ME. The effect of music on anxiety. A research study AORN J. 1989;50:112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee K-C, Chao Y-H, Yiin J-J, Chiang P-Y, Chao Y-F. Effectiveness of different music-playing devices for reducing preoperative anxiety: a clinical control study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:1180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee K-C, Chao Y-H, Yiin J-J, Hsieh H-Y, Dai W-J, Chao Y-F. Evidence that music listening reduces preoperative patients’ anxiety. Biol Res Nurs. 2012;14:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S. Applying Chinese classical music to treat preoperative anxiety of patients with gastric cancer. Chin Nurs Res. 2004;18:471–2. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin P-C, Lin M-L, Huang L-C, Hsu H-C, Lin C-C. Music therapy for patients receiving spine surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:960–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miluk-Kolasa B, Klodecka-Rozalska, Stupnicki R. The effect of music listening on perioperative anxiety levels in adult surgical patients. Polish Psychological Bulletin. 2002;33:55–60.

- 55.Miluk-Kolasa B, Matejek M. Stupnicki R. The effects of music listening on changes in selected physiological parameters in adult pre-surgical patients. J Music Ther. 1996;33:208–18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ni C-H, Tsai W-H, Lee L-M, Kao C-C, Chen Y-C. Minimising preoperative anxiety with music for day surgery patients - a randomised clinical trial. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:620–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szeto CK, Yung PM. Introducing a music programme to reduce preoperative anxiety. Br J Theatre Nurs. 1999;9:455–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor-Piliae RE, Chair S-Y. The effect of nursing interventions utilizing music therapy or sensory information on Chinese patients’ anxiety prior to cardiac catheterization: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;1:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson M, Moe K, Lewis CP. The Effects of Music on Diminishing Anxiety Among Preoperative Patients. J Radiol Nurs. 2014;33:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winter MJ, Paskin S, Baker T. Music reduces stress and anxiety of patients in the surgical holding area. J Post Anesth Nurs. 1994;9:340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yung PMB, Chui-Kam S, French P, Chan TMF. A controlled trial of music and pre-operative anxiety in Chinese men undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:352–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yung PMB, Kam SC, Lau BWK, Chan TMF. The effect of music in managing preoperative stress for Chinese surgical patients in the operating room holding area: A controlled trial. Int J Stress Manag. 2003;10:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palmer JB, Lane D, Mayo D, Schluchter M, Leeming R. Effects of Music Therapy on Anesthesia Requirements and Anxiety in Women Undergoing Ambulatory Breast Surgery for Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3162–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amiri MJ, Sadeghi T, Negahban BT. The effect of natural sounds on the anxiety of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Perioper Med. 2017;6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haun M, Mainous RO, Looney SW. Effect of Music on Anxiety of Women Awaiting Breast Biopsy. Behav Med. 2001;27:127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Y, Dong Y. Preoperative music intervention for patients undergoing cesarean delivery. Intl J Gynecol Obste. 2012;119:81–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kushnir J, Friedman A, Ehrenfeld M, Kushnir T. Coping with Preoperative Anxiety in Cesarean Section: Physiological, Cognitive, and Emotional Effects of Listening to Favorite Music. Birth. 2012;39:121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chiu HW, Lin LS, Kuo MC, Chiang HS, Hsu CY. Using heart rate variability analysis to assess the effect of music therapy on anxiety reduction of patients. In: Computers in Cardiology, 2003. Thessaloniki Chalkidiki, Greece: IEEE; 2003. p. 469–72.

- 69.Lee D, Henderson A, Shum D. The effect of music on preprocedure anxiety in Hong Kong Chinese day patients. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hayes A, Buffum M, Lanier E, Rodahl E, Sasso C. A music intervention to reduce anxiety prior to gastrointestinal procedures. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walworth D, Rumana CS, Nguyen J, Jarred J. Effects of live music therapy sessions on quality of life indicators, medications administered and hospital length of stay for patients undergoing elective surgical procedures for brain. J Music Ther. 2008;45:349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santacroce SJ, Maccarelli LM, Grey M. Intervention Fidelity. Nurs Res. 2004;53:63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robb SL, Hanson-Abromeit D, May L, Hernandez-Ruiz E, Allison M, Beloat A, et al. Reporting quality of music intervention research in healthcare: A systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2018;38:24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robb SL, Burns DS, Carpenter JS. Reporting guidelines for music-based interventions. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:342–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McClurkin SL, Smith CD. The Duration of Self-Selected Music Needed to Reduce Preoperative Anxiety. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reynaud D, Bouscaren N, Lenclume V, Boukerrou M. Comparing the effects of self-selected MUsic versus predetermined music on patient ANXiety prior to gynaecological surgery: the MUANX randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22:535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vetter D, Barth J, Uyulmaz S, Uyulmaz S, Vonlanthen R, Belli G, et al. Effects of Art on Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:704–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lu G, Jia R, Liang D, Yu J, Wu Z, Chen C. Effects of music therapy on anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res. 2021;304:114137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henshaw H, Clark DPA, Kang S, Ferguson MA. Computer skills and internet use in adults aged 50–74 years: influence of hearing difficulties. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, Blanchard-Fields F. Age differences in emotional responses to daily stress: The role of timing, severity, and global perceived stress. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:1076–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brose A, Scheibe S, Schmiedek F. Life contexts make a difference: Emotional stability in younger and older adults. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:148–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seals DR, Esler MD. Human ageing and the sympathoadrenal system. J Physiol. 2000;528:407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hilz MJ, Stadler P, Gryc T, Nath J, Habib-Romstoeck L, Stemper B, et al. Music induces different cardiac autonomic arousal effects in young and older persons. Auton Neurosci. 2014;183:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mojtabavi H, Saghazadeh A, Valenti VE, Rezaei N. Can music influence cardiac autonomic system? A systematic review and narrative synthesis to evaluate its impact on heart rate variability. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lunny C, Pieper D, Thabet P, Kanji S. Managing overlap of primary study results across systematic reviews: practical considerations for authors of overviews of reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grau-Sánchez J, Jamey K, Paraskevopoulos E, Dalla Bella S, Gold C, Schlaug G, et al. Putting music to trial: Consensus on key methodological challenges investigating music-based rehabilitation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2022;1518:12–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Edwards E, St Hillaire-Clarke C, Frankowski DW, Finkelstein R, Cheever T, Chen WG, et al. NIH Music-Based Intervention Toolkit: Music-Based Interventions for Brain Disorders of Aging. Neurology. 2023;100:868–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.