Abstract

Background

Iron deficiency anaemia is a common disorder affecting up to 30% of pregnant women. Treatment guidelines for iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy exist, which if adopted, may reduce the associated risks of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. However, multiple factors may impair adherence and absorption of oral iron, limiting the success of this first-line treatment.

Methods

To document the effectiveness of national (British Society of Haematology) guidelines for the treatment of iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) in pregnancy, with a focus on use of oral iron, we carried out a prospective cohort study. Aims were to assess the response, side effect and adherence to treatment and predictability of response using routine clinical and laboratory data. The study population consisted of pregnant women diagnosed with anaemia. Women were offered follow-up through a dedicated anaemia clinic in a secondary care maternity unit serving a multi-ethnic population in the midlands of England. First line treatment was ferrous sulphate 200 mg three time a day as recommended in earlier national guidelines. The response was assessed 2 to 4 weeks later by measuring the haemoglobin (Hb) concentration. A response was defined in 2 ways; (i) a 10 g/L increase in Hb; and (ii) a 10 g/L increase in Hb and/or gestationally adjusted threshold of the Hb. Education and advice were provided to women, with on-going follow-up at clinic appointments including an assessment of side effects. Following a response with oral iron, treatment was continued for a further 3 months when the women were again reviewed.

Results

The overall rate of haematological response to a first course of oral iron was 36.5% (10 g/L increase in Hb) and 55.2% (incorporating gestational threshold in Hb). The response rates at the completion of follow up, post-delivery, were 70.5% and 88.5% respectively. Responders to oral iron had lower median Hb at diagnosis (95 g/L) compared to non-responders (100 g/L). The responders median Hb was 113 g/l versus 103 g/L for non-responders at first follow-up and was Hb 122 g/L versus 110 g/L, respectively, at the end of the study visit 5. There is a statistically significant difference between responders and non-responders for the change in haemoglobin from baseline to visit 5 (p = 0.017). Non-responders reported more side effects than responders (95% versus 85%).

Conclusion

Oral iron treatment for IDA in pregnancy as advocated in national guidelines is challenging to deliver, even in the setting of a specialist anaemia clinic. The findings have implications for guideline recommendations and implementation, and identify research opportunities for diagnosing IDA in pregnancy, optimising the pathways of iron treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-07938-w.

Keywords: Anaemia, Response, Iron, Diagnosis, Adherence, Prediction

Background

Current approaches to address the on-going high burden of anaemia during pregnancy, largely caused by iron deficiency, have been described in multiple guidelines, including British Society for Haematology guidelines in UK [1–5]. Timely recognition and treatment of iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) during pregnancy is recommended, given that the reported risks associated with anaemia for the mother and infant, include stillbirth and neonatal death [6, 7]. In the first and second trimesters, IDA has also been correlated with low birth weight and pre-term birth, both of which lead to significant morbidity lasting into infancy and sometimes adult life [8–12].

Despite guidance, our recent nationwide prospective audit reported a high incidence of anaemia at 30% during pregnancy and 20% post-delivery [13]. This suggests on-going challenges with improving care, even allowing for recommendations in guidelines. The increased demand for iron in pregnancy is driven by the expanded blood volume of the mother and the requirements of the developing fetus and placenta. Oral iron is commonly the first-line treatment option but is recognised to cause significant gastrointestinal side effects that are thought in turn to cause additional problems with adherence. More recently there has been an increase in the use of parenteral (intravenous) iron, to produce a more rapid correction of anaemia and increase in iron stores, while avoiding the gastrointestinal side effects. It is likely that there is significant variation in treatment practices around the country on how best to integrate guidelines for treatment into an overloaded maternity system.

We wished to document and describe the success rates and challenges of treating IDA during pregnancy, when adhering with as much fidelity as was possible, to national guidelines. To this end we offered women with a diagnosis of IDA during their pregnancy, additional focussed care delivered through a dedicated anaemia clinic. This was staffed by a clinical research fellow in obstetrics, a research assistant, and was overseen by a consultant obstetric specialist (DC).

The aim of this study was to report on the effectiveness of guideline recommendations for treatment of IDA during pregnancy. We focused in particular on the response to oral iron, as this is the most common form of treatment used in UK practice and the mode of administration which is most problematic to deliver and assess responses. We also wanted to explore if it was possible to identify women who were more likely to respond to oral iron by combining routine clinical and haematological measures taken at the time of diagnosis into a predictive model. Specific study objectives were to describe and quantify the responses to oral iron treatment and to explore the effect of demographic, clinical and laboratory variables in predicting response to treatment.

Methods

Study design

This prospective, single centre, cohort study recruited pregnant women with IDA. Women who consented to participate were offered support, treatment, and follow-up through a dedicated anaemia research clinic. Eligible participants with IDA were identified in two ways; (1) those diagnosed de novo in the hospital antenatal and/or community clinics and antenatal maternity ward or (2) from a daily download of blood results of routine screening samples taken either at the first trimester or the 28th week gestation antenatal visits [14]. Eligible women were approached by the research staff and given information about the project, prior to seeking consent. The diagnostic thresholds of anaemia were defined by the criteria described in British Society Haematology (BSH) guidelines and by the World Health Organization guidance at the time, which are gestationally adjusted haemoglobin thresholds of: first trimester < 110 g/L, second and third trimester < 105 g/L, and postpartum < 100 g/L.

Study setting

The study was carried out in a maternity unit of a large District General Hospital in the midlands of England. The population served by the unit has a diverse mix of ethnicities, white British/European, Asian and Black African and Black Caribbean being the 4 largest groups. The area is one of the most deprived in England with 70% of the population falling within the 2 most deprived quintiles when measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) published by the Office for National Statistics. As a consequence, there are high rates of non-communicable diseases affecting the population and high rates of perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Sample participants

Recruitment of participants ran from June 2018 to August 2019, with follow up being completed in December 2019. Analysis of the data and blood samples was then disrupted by the COVID 19 pandemic. Analysis of the study (non-routine) blood samples was completed in 2022.

Inclusion criterion were any pregnant women aged between 18 and 45 years with a diagnosis of IDA up to 35 weeks’ plus 6 days gestation. We defined IDA using the BSH guidelines, which uses thresholds of haemoglobin adjusted for gestation [5]. We excluded women presenting at or after 36 weeks. There were differing clinical opinions about what should be first line treatment in this group who were so close to potential spontaneous labour and it was judged that there might be insufficient time between diagnosis and the end of pregnancy to complete assessments of oral treatment. Other exclusion criteria included: a major haemoglobinopathy, active infection, hyperemesis gravidarum/persistent vomiting, gastrointestinal disease (Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis), systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic renal failure and allergies to iron.

Interventions

This was a non-interventional study, and clinical management of IDA followed recommendations detailed in national guidelines [4, 5], adopted into local guidance documents. To deliver best practice for anaemia management in pregnancy, we introduced a dedicated anaemia research clinic modelled on the pre-operative anaemia clinic services, as advocated nationally e.g. https://hospital.blood.co.uk/patient-services/patient-blood-management/pre-operative-anaemia. Women identified as anaemic were offered the option of management and follow-up through this clinic, supported by a research fellow and consultant obstetrician. The study started when earlier national guidance was in place, which recommended daily iron dose of 100-200 mg elemental iron per day; prescribed as 200 mg ferrous sulphate three times a day (65 mg elemental iron per tablet x 3 = 195 mg).

All women were offered a full blood count (FBC) to screen for IDA usually 8–12 weeks’ gestation and then 28 weeks’ according to standard practice [2]. Women who consented to participate were started on oral iron no longer than 14 days from the point of diagnosis (Visit 1). Enrolled women were given verbal instructions, and written information on the correct way to take the tablets to maximise absorption.

Women were asked to return for a follow up visit, between 2 and 4 weeks after initiating treatment, when a peripheral blood count was taken to assess the therapeutic response and assessments were made of side effects and adherence (Visit 2). The variation in follow up visits was to coincide with a woman’s obstetric appointments. Iron has a marketing authorisation (MA) in the UK and is being used in this study in its marketed presentation and packaging bearing the MA number.

Non-response to therapy

Women who did not demonstrate either an increase in their haemoglobin concentration by 10 g/L or normalised the Hb for gestation were reviewed. If the non-response was due a modifiable factor further advice and adjustments were provided. Adjustments included further advice on the best way to take the medication, e.g. on an empty stomach at least 30 min before food, with a drink containing vitamin C, similarly, not at the same time as other medications that interfere with absorption e.g. proton pump inhibitors etc., treating side effects such as constipation with laxatives, and if required lowering the frequency of the dose schedule down to twice or once daily. Women were asked to continue with the modified treatment regimen and continue recording in their treatment diary. They were reviewed in a further 2 weeks (Visit 3), when the same process as in Visit 2 was followed. Women who had increased their haemoglobin into the normal range for pregnancy were maintained on oral iron. As per routine practice, women who continued to be non-responders, when assessed at visit 3, had blood sampling for vitamin B12 and folate levels and were considered for intravenous ferric carboxymaltose. Sixteen women received intravenous iron, 2 iron dextran and 14 ferric carboxymaltose. They were also asked to return to the clinic after a further 2 weeks for repeat blood sampling (including research blood samples) to ensure that they responded to the intravenous treatment.

Data collection

Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory data were collected from the patient care record and laboratory information systems. Additional data were collected at each visit, and obstetric outcome data collected at the postnatal follow up visit 6 weeks after birth. At each visit, the frequency and severity of symptoms experienced by the participant and associated with IDA was assessed using an adapted version of a published pregnancy symptomatology tool [15]. The frequency of side effects was assessed by examining the pre-piloted tolerability and symptom tool adapted from a questionnaire developed to assess gastrointestinal symptoms after oral ferrous sulphate supplementation [16]. Finally, participants were asked to complete a Well-being in Pregnancy (WiP) questionnaire [17].

Participants were also requested to keep a diary, recording the time at which they took their medication, the symptoms of anaemia experienced at the time and the side effects suffered since the last tablet was taken. The completed diary was returned at the follow up visits and supplemented the information gathered through questionnaires on adherence and side effects/symptoms suffered since the preceding visit.

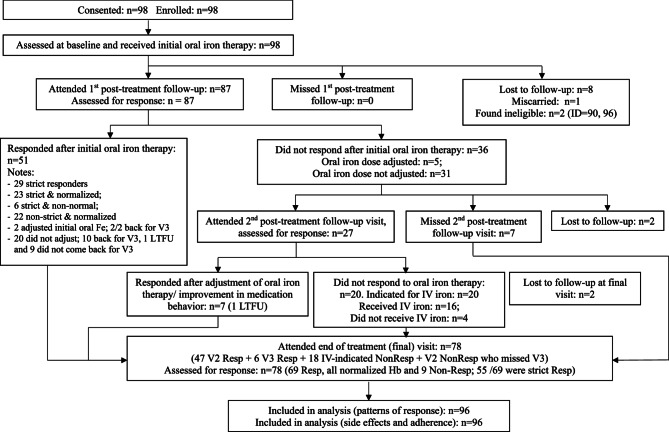

Blood sampling

The diagnosis of IDA was made on routine sampling with a peripheral venous blood count. Once women consented to participate in the study blood samples were collected at baseline and follow up visits (see Fig. 1) for a repeat peripheral venous blood count, iron studies and general biochemistry. An additional sample of blood was taken, processed, and stored at −80 degrees Celsius, for more specialist iron and inflammatory biomarker studies and will be the subject of a separate report.

Fig. 1.

Participant flowchart. N.B. "strict" refers to the primary outcome of a >10g/L increase in haemoglobin

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of women with an increase in Hb of > 10 g/L, 2–4 weeks after the start of treatment.

Secondary outcome measures included:

An increase in Hb by ≥ 10 g/L, 2-4weeks after the start of treatment and/or with normalization of the haemoglobin concentration, adjusted for gestational age. This measure recognized that the physiological changes of pregnancy result in haemodilution and thus a fall in the concentration of haemoglobin across gestation.

longitudinal changes in haemoglobin, red cell indices, iron, transferrin, ferritin, TSAT, CRP, biochemistry for liver enzymes, urea and electrolytes and creatinine.

Change in frequency and severity of symptoms associated with anaemia in pregnancy and assessed by the pregnancy symptomatology questionnaire [15].

Frequency and severity of side effects induced by iron therapy by an adapted published tolerability tool [16], and general wellbeing [17].

Statistical analysis

Sample size

As this was an exploratory cohort study and did not involve a novel intervention, we did not perform a sample size calculation and pragmatically proposed to recruit 120 women. This number was based on estimated numbers of anaemic women seen in the antenatal clinics and wards during the preceding 24 months and to support secondary and exploratory analyses required to meet the objectives. Differences between responders and non-responders were explored by comparing baseline demographic data, haematological, and iron parameters. Distributions of haematological and iron parameters between responders and non-responders at V2 and V5 were compared and checked for equality using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

The primary outcome was described as a percentage for the group. To calculate the response rate to oral treatment, the results for visit 2 & 3 were combined. Categorical variables were summarized using percentages and quantitative variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile ranges. The proportion of women achieving responses were estimated using the observed sample proportion and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the Wilson-Score Method. Women who dropped out at V2 or V5 were considered as non-responders. Our rationale was that we were aiming to adhere to the guidelines with a high degree of fidelity. As such it was felt that it would be better to include them as treatment failures, rather than assume that they were not and potentially inflate the treatment success rate. In our view part of the treatment package includes the process of follow up with confirmation of a response.

Logistic regression models were explored to identify predictors of responses from the set of baseline demographic (index of deprivation quintile, ethnicity, marital status), obstetric (parity, trimester of recruitment), and routinely collected haematological and iron indices. Principal component analyses were further utilized to derive scores representing combinations of haematological and iron indices. Positive and negative predictive values were obtained to assess the predictive utility of the model and positive predictive values of at least 75% were considered useful for practice. Statistical analyses were performed using statistical analysis software (SAS/STAT, Version 9 of the SAS System for Windows, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

The report has been prepared using the STROBE guidelines for reporting observational cohort studies.

Results

Baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

The flow diagram (Fig. 1) shows the number of individuals at each stage of the study and the reasons for withdrawal. The characteristics of enrolled pregnant women is shown in Table 1. and appears representative of the general maternity population served by the hospital located in a central urban environment encompassing 2 years, 2018 and 2019. The mean age was 29 years and the proportions for body mass index and socioeconomic deprivation were as expected, with 65.6% of the population being in the 2most deprived quintiles when measured by the index of multiple deprivation score produced by the Office of National Statistics, UK. The ethnic diversity reflected that of the local population where around 62.5% is from ethnic minority groups.

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

| Antenatal (N=96) | Antenatal with ≥ 1 follow-up visit (N=87) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median (IQ range) | 29 (25 – 34) | 30 (26 – 35) |

| 29 (19 – 45) | 30 (19 – 45) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | Asian | 32 (33.3) | 31 (35.6) |

| Black | 17 (17.7) | 14 (16.1) | |

| Mixed | 11 (11.5) | 10 (11.5) | |

| White | 36 (37.5) | 32 (36.8) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Married | 47 (49.0) | 43 (49.4) |

| Gestation at recruitment (days) | Mean (SD) | 170.0 (62.9) | 171.4 (62.31) |

| Median (Min – Max) | 203.0 (51 - 250) | 203 (51 - 250) | |

| Gravida | 1 | 26 (27.1) | 21 (24.1) |

| 2 | 30 (31.3) | 29 (33.3) | |

| 3 | 16 (16.7) | 15 (17.2) | |

| 4 | 14 (14.6) | 13 (14.9) | |

| >=5 | 10 (10.4) | 9 (10.3) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Parity, n (%) | Multiparous | 63 (65.6) | 59 (67.8) |

| Obesity Class | Non-overweight | 47 (49.0) | 44 (50.6) |

| Overweight | 26 (27.1) | 24 (27.6) | |

| Obese | 23 (24.0) | 19 (21.8) | |

| I | 15 (15.6) | 13 (14.9) | |

| II | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | |

| III | 4 (4.2) | 4 (4.6) | |

| Super-morbid | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Medical comorbidities, n (%) | Present | 21 (21.9) | 19 (21.8) |

| Asthma | 5 (5.2) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Sickle Cell Trait | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.4) | |

| Gestational Diabetes Mellitus GDM | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.4) | |

| Mood Disorders | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.4) | |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation | 1 | 63 (65.6) | 58 (66.7) |

| 2 | 14 (14.6) | 13 (14.9) | |

| 3 | 8 (8.3) | 6 (6.9) | |

| 4 | 7 (7.3) | 6 (6.9) | |

| 5 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Not reported | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.4) |

98 women agreed to enter the study, 2 were found to be ineligible and so were excluded. 96 women were therefore included in the data analysis. 8 women were lost to follow up between entry into the study and the follow up visit. 1 woman suffered a miscarriage in the same period. Therefore, 87 women had 1 or more follow up visits. The 9 women withdrawn from the data set had no material impact on the data with no significant differences found between the whole group and the 87 with follow up data.

Primary outcome

The overall response rate defined as increase Hb > 10 g/L at follow up after oral iron, (visit 2 & 3) was 36.5%. For the response rate incorporating a rise in Hb above the gestational threshold +/- an Hb rise > 10 g/L, the response rate was 55.2%. By the end of full treatment, (oral and intravenous iron), 3 months following diagnosis, (visit 5) the response rates were 57.3% (Hb > 10 g/L) and 71.9% (after incorporating the gestational threshold). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Response, remission and retention rates according to BCSH 2012 guidelines

| Outcomes | Categories | Post oral iron therapy follow-up (V2&V3) | End of iron therapy follow-up (V5 end of treatment 3 months after the diagnosis) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Incidence 1 (95% CI) | N | Incidence 1 (95% CI) | ||

| Response rates. | Haematological response2 | 35 |

36.5 (27.6–46.4) 40.2 (30.4–50.7) § |

55 |

57.3 (47.3–66.7) 70.5 (59.8–79.7) § |

| Haematological and/or gestational response3 | 53 |

55.2 (45.3–64.8) 60.9 (50.4–70.7) § |

69 |

71.9 (62.2–79.7) 88.5 (80.0–94.1) § |

|

| Attrition 4 | 9 | 9.4 (5.0–16.9) | 18 | 18.7 (12.2–27.0) | |

| Types of Non-Response 5 | Insufficient Hb increase | 16 | 47.1 (31.1–63.5) § | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–23.8) § |

| No change | 3 | 8.8 (2.5–21.7) § | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–23.8) § | |

| Worsening | 15 | 44.1 (28.5–60.7) § | 9 | 100.0 (76.2–100.0) § | |

| Remission by severity 6 of baseline Hb deficit |

Non-severe (nV2V3= 54; nV5 = 47) |

33 | 61.1 (47.8–73.3) § | 39 | 83.0 (70.4–91.6) § |

|

Severe (nV2V3 = 33; nV5 = 31) |

12 | 36.4 (21.6–53.4) § | 30 | 96.8 (85.9–99.6) § | |

| Total number of women | 87 | 90.6 (83.6–95.3) | 78 | 81.3 (72.6–88.1) | |

| Retention | Asian (n = 32) | 31 | 96.9 (86.3–99.7) | 29 | 90.6 (77.0–97.3) |

| Black (n = 17) | 14 | 82.4 (60.0–94.8) | 14 | 82.4 (60.0–94.8) | |

| Mixed (n = 11) | 10 | 90.9 (64.7–99.0) | 10 | 90.9 (64.7–99.0) | |

| White (n = 36) | 32 | 88.9 (75.7–96.1) | 25 | 69.4 (53.3–82.6) | |

Response rates are shown for oral iron alone after visits 2&3 and at visit 5 completion of treatment when it includes the women who received intravenous iron following a failure to respond to oral iron

1Incidence of response, attrition, remission and overall retention calculated based on total eligible antenatal population (N = 96). § Incidence of response, non-response and remission calculated based on participants with observed outcomes, i.e., n = 87 at V2/V3 and n = 78 at V5

2Haematological response is defined as attainment of ≥ 10 increase in Hb from baseline

3Haematological and or a gestational response is defined as attainment of ≥ 10 increase in Hb from baseline or remission, i.e., normalisation of Hb (based on trimester-specific thresholds)

4Attrition due to loss to follow-up or miscarriage: at V2/V3, 8 were lost to follow-up and 1 miscarried; at V5, 9 more participants were lost to follow-up

5Non response with respect to an increase > 10 g/L; 34 of 87 participants (at V2/V3) and 9 of 78 (at V5) failed to respond to iron therapy

6Non severe baseline Hb is defined as Hb requiring < 10 g/dL units to normalise; Severe baseline Hb is defined as Hb requiring ≥ 10 g/dL to normalise

The scatter plot (Fig. 2) shows haemoglobin of the group of women diagnosed with IDA during pregnancy (represented by the orange dots), who failed to increase their haemoglobin by 10 g/L at visit 2, but normalized their haemoglobin based upon the gestation specific levels above which is considered normal for pregnancy. From the clustering of cases (orange dots), this group of women tended to have higher levels of haemoglobin at the time of diagnosis and recruitment into the study.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plat of women who responded to treatment vs. non-responders according to Hb at recruitment. A scatter plot of haemoglobin at recruitment (diagnosis), x axis, by response haemoglobin at the follow up visit 2, y axis The orange dots represent the women who were classified as responders when the definition of a response also included normalization of Hb adjusted for gestational age

The women with a 10 g/L response to oral iron therapy had lower median levels of haemoglobin at diagnosis than those who did not respond, median Hb at baseline 95 g/L versus 100 g/L. After treatment, the median Hb level in this responder group was higher than the non-responders, at V2, 113 g/L versus 103 g/L and this difference persisted throughout pregnancy. At the final assessment visit, 3 months after the original diagnosis (V5) had been made and treatment initiated, the median Hb for those who responded to oral treatment was 122 g/L and for the non-responders 111 g/L. When the broader definition of response was used, women with a 10 g/L increase in Hb or an increase that was above the gestationally adjusted threshold for Hb, but less than 10 g/L the same pattern emerged, although the median baseline haemoglobin was the same in both groups, the increase in the Hb of responders using this broader definition relative to non-responders was also maintained throughout the period of treatment and follow. Figure 3 shows responses of haemoglobin at V2.

Fig. 3.

Change in haemoglobin concentrations throughout the study by responder and non-responder status. Change in haemoglobin concentration from baseline to visit 2 and then 5, the end of the study separated by both the haematological response > 10 g/L and broader definition of response that includes an increase in haemoglobin above the gestational adjusted Hb threshold but not necessarily by > 10 g/L

The change in haemoglobin was compared between the baseline visit, the initial and final follow up visits. At both time points there was a significant difference in the change in haemoglobin concentration between responders and non-responders.

By the final visit (V5) all women had given birth. Those women who had responded to treatment, which includes the women who had also received intravenous iron, had a higher haemoglobin concentration than those who did not respond. By visit 5 the increase in Hb in the responder group was 20 g/L and only 13 g/L in the non-responders P = 0.017).

All women who met the > 10 g/L response criteria also normalized their gestationally adjusted haemoglobin concentration. Of the 37 women who did not meet this definition of a response, 22 increased their haemoglobin concentration above the gestationally adjusted threshold to no longer fall into the defined criteria as being anaemic for a pregnant woman. The different definitions of response rates to oral iron have been mapped against each other and are shown in Table 3. The pattern of changes in haemoglobin was mirrored by the changes in haematocrit (see supplementary Table 5).

Table 3.

Response to oral iron cross tabulating the two definitions

| > 10 g/L and/or normalisation for gestation | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| > 10 g/L only | No | Yes | |

| No | 37 (41.6) | 22 (24.7) | 59 (66.3) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 30 (33.7) | 30 (33.7) |

| Total | 37 (41.6) | 52 (58.4) | 89 (100.0) |

The numbers of responders and non-responders by each definition showing that 41.6% of women failed to respond to treatment by either definition and 33.7% responded by both definitions. The difference in final response rates between the two definitions was the 24.7% of women normalised their Hb above the threshold for the gestation of pregnancy, but failed to obtain a 10 g/L increase in haemoglobin concentration in the required time frame for follow up

normalised their Hb for the gestation of pregnancy but failed to obtain a 10 g/L increase in haemoglobin concentration in the required time frame for follow up

Other outcomes

Adherence

To assess adherence, we used the broader definition of a response. Pragmatically, women who did not reach the threshold of 10 g/L, but normalized their haemoglobin concentration for the gestation continued their original dose rather than have any dose adjustments or be offered intravenous iron, thus, reflecting clinical practice. Self-reported adherence was similar in both groups, with 71% of responders and 67.7% of non-responders stating they had taken their medication as instructed. Women who reported being adherent were less likely to suffer from nausea, p = 0.032. But for the other symptoms associated with iron there were no statistically significant differences between women who were adherent and those that were not. There were no differences noted for the total number of side effects. (Supplementary Table 6).

95% (95%) of non-responders reported one or more side effect attributed to the medication compared to 85% of participants who were recorded as responding. Of the women who reported a high number of side effects (4 or 5 out of a possible 5), 18.6% were in the group of non- responders and 12.5% in the group of responders. The incidence of black stools in the non-responder group was 23% higher than responders to treatment. But there were no statistically significant differences between the groups for each of the side effects and for a composite measure of all the side effects together (Supplementary Table 7).

When we examined these differences by ethnic group, we discovered that black women (women of African/Caribbean heritage) and women of mixed racial heritage were less likely to respond to treatment when directly compared to white women OR 0.15 (95%CI 0.017,0.949) and OR 0.11 (95%CI 0.005, 0.93) respectively. There was no difference in response rates between Asian and White women OR 0.92 (ci 0.22, 3.98). These differences between the ethnic groups remained even after adjustment for side effects.

We found no statistical difference between those that responded to oral iron and those that did not for general wellbeing.

Modelling

We used logistic regression modelling to test if these data could identify women who were more likely to respond to oral iron treatment, but all models displayed limitations. Model 1 using the haemoglobin at diagnosis and the variables, ethnicity, trimester at recruitment, marital status and parity had a predictive accuracy of 75%. The specificity was high at 89.8% but the sensitivity low at 42.9%. We then tested to see how much baseline laboratory data improved the predictability of the model. Using principal component analysis (PCA), two models were constructed, PC1, which included alkaline phosphatase, Albumin, Transferrin, calculated total iron binding capacity (TIBC), iron saturation and iron, and PC2, which included mean cell volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC). The laboratory models showed a marginal gain in the specificity to 92.3% but a reduction in the sensitivities to 30.8% and 34.6% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Principal component models used to predict most likely to respond to oral iron at visit 2

| Models | True positive rate | True negative rate | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Overall predictive accuracyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Baseline) n = 87 | 42.9 | 89.8 | 66.7 | 76.8 | 74.7 |

|

Model 2a n = 77 (Model 1 + PC1 and PC2) |

44.0 | 88.5 | 64.7 | 76.7 | 74.0 |

|

Model 3 n = 78 PC1 + PC2 |

30.8 | 92.3 | 66.7 | 72.7 | 71.8 |

|

Model 4 n = 78 Hb1 + PC1 |

34.6 | 92.3 | 69.2 | 73.8 | 73.0 |

Summary of (crude) predictive ability: Model 1 Baseline = haemoglobin at diagnosis, ethnicity, trimester at recruitment, support status, and parity. PC1 = alkaline phosphatase, albumin, transferrin, total iron binding capacity iron saturation and iron. PC2 = mean cell volume, mean corpuscular haemoglobin, and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration

aIn Model 2, Hb at recruitment was dropped because Hb is already in PC2

bNot corrected for chance

We also examined the impact of socio-economic deprivation on the predictive ability of the models. Using the index of multiple deprivation (IMD), as a single measure and then each of its component parts were included in the models. There were no material changes to the results (Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

We successfully followed up a cohort of women with anaemia during pregnancy in the setting of a dedicated maternity anaemia clinic. Our study focused on delivering best practice guidance as closely as possible, to evaluate the success of oral iron treatment for anaemia. Key findings of our study are that around two thirds of affected women failed to increase their haemoglobin concentration by the criteria of 10 g/L 2 to 4 weeks following the start of treatment with oral iron and educational support. Even when the definition of response to treatment was adjusted to account for the physiological changes in pregnancy, around a half of women still appeared to fail to respond to oral iron therapy. Self-reported levels of adherence were similar between responders and non-responders. Overall, the trend in the incidence of side effects (black stools, constipation, diarrhoea, heartburn, and nausea) was consistently lower among responders compared to non-responders. No significant differences for specific side effect were identified between the two groups.

Our study findings suggest that even after optimising the management pathway for treating iron deficiency anaemia, closely following national guidelines, a significant proportion of women identified (and labelled) as iron deficient failed to demonstrate an adequate haematological response according to recognised criteria [4, 5]. The findings raise broad questions about the use of oral iron in pregnancy, which is currently the first line treatment. Our study was started prior to updated national guidance which promotes lower daily doses of oral iron, but we believe our findings have value as an evaluation of practice and in the context of implementing guidelines [14]. It should also recognised that the evidence for lower doses of iron showing improved absorption with alternate day dosing was initially conducted in non-pregnant women [18], which may not apply in pregnancy.

Our study extends previous quality improvement projects, which although describing improvements in the processes of management of iron deficiency [19, 20], have not addressed the issue of expected response from treatment and the reasons why many women fail to respond. Although it is widely reported that the gastrointestinal side effects caused by oral iron result in problems with adherence [21–24], in our study, self-reported levels of adherence were similar between responders and non-responders. The differences between the women who responded to treatment and those who failed to respond is unknown but might be accounted for in several ways. Non-responders may have been more severely affected by the side effects leading to a non-significant reduction in adherence. Although we were unable to measure the severity of the side effect profiles, these data show that the percentage reporting each side effect was consistently higher in the non-responder group. It is possible that the women who did not respond to treatment were not as iron depleted, but as iron parameters are not routinely measured at diagnosis this requires further investigation.

Also as group, their Hb concentration at the time of diagnosis was higher than women who did respond, a state that was mirrored in their haematocrit. This highlights the difficulties that are encountered with the diagnosis of IDA in pregnancy. The physiological increase in plasma volume during pregnancy of about 40% over and above the 30% increase in red cell mass results in haemodilution, lowering the haemoglobin threshold for diagnosis in the second and third trimesters. The BSH guidance sets the threshold at these trimesters below which anaemia is diagnosed at 105 g/L It is possible that a group of women labelled as having IDA are in fact simply showing the normal haemodynamic changes of a healthy pregnancy [25]. This would be consistent with the finding that “mild anaemia” improves some obstetric outcomes [26, 27]. It has been suggested that a measured ferritin level is used to improve the diagnosis. However, this approach has problems too. While ferritin is a good marker of iron stores the cut-off point in pregnancy is disputed and it is not a measure of functional iron [28–32]. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that some women diagnosed with IDA are in fact iron replete and have haemoglobin concentrations lower than the gestational threshold because of the haemodilution. Attempts have been made to utilize other routine haematological and iron indices to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of IDA during pregnancy and predict response [25]. Using PCA, we derived scores, combining routine haematological and iron biomarkers and clinical features, in our logistic regression models. None of our models reached acceptable thresholds to be recommended for clinical practice. Therefore, the criteria for diagnosing IDA should not rely on haemoglobin alone and may need to include other measures of iron status, possibly serum transferrin receptor, TSAT, Ferritin, Hepcidin or a combination of these variables. Clearly more work is needed to refine the diagnostic criteria for anaemia in pregnancy into a useful diagnostic model.

Strengths and limitations

Support and guidance on management of iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy was implemented in a dedicated anaemia clinic, achieving a high level of follow-up. The study was a single centre evaluation, therefore limiting the extrapolation of the findings to other maternity populations. The implications of our work for low- and middle-income settings, where IDA is more prevalent, requires further study. Also, the timing of follow up to see if there had been a response to treatment was wider than recommended for some women. This was for pragmatic reasons, but future studies will need to address this issue.

A significant limitation was the change in guidance for oral iron treatment during the study period. The recommendations for dosing with ferrous sulphate were changed, from 200 mg three times a day, reducing it to 65 mg (one 200 mg tablet) of elemental iron per day [5, 33, 34]. However, recent evidence shows that alternate day compared to consecutive day dosing does not necessarily result in higher levels of ferritin but does have reduced numbers of gastrointestinal side effects [18]. It therefore remains possible that some of our results were affected by the dosing frequency, or the formulation of the iron preparation used, which had an impact on the frequency of side effects experienced by the women and thus affected their adherence with oral treatment. Newer or alternative formulations may improve absorption or adherence [35].

Implications for practice and research

In our maternity centre we adopted a model of anaemia care based on well-established pre-operative surgical anaemia clinics. Whether this model of care works in maternity services, often over-stretched in the NHS, remains unclear. The attrition rate at the follow up visits 2 and 3 was 10%, and at the end of treatment (V5), the attrition was 20%. Since women who dropped out were automatically considered as ‘non-responders’ this means that the estimate of overall response at the end of treatment which is 57.3% is a lower bound or the worst-case scenario estimate of the proportion of responders.

Attempts have been made to utilize other routine haematological and iron indices to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of IDA during pregnancy and predict response [25]. Using PCA, we derived scores, combining routine haematological and iron biomarkers and clinical features, in our logistic regression models. None of our models reached acceptable thresholds to be recommended for clinical practice. Therefore, the criteria for diagnosing IDA should not rely on haemoglobin alone and needs to include other measures of iron status, possibly serum transferrin receptor, T-sat, Ferritin, Hepcidin or a combination of these variables.

Research continues to be required into the diagnosis and optimal management of IDA, including the role of iv iron. The use of intravenous iron is increasing in clinical practice, but when and in which groups of pregnant women it should be used requires a stronger evidence-base [36]. Given the problems with the treatment of IDA in pregnancy that have been demonstrated in this work, there is a case for investigating the use of prophylactic iron to try to prevent iron deficiency during pregnancy [37]. Prophylaxis has been recommended by several organizations including Network for the advancement of patient blood management haemostasis and thrombosis (NATA) and WHO to take into account the increased requirement for iron during pregnancy that, so often, is unmet through diet. It is estimated that without supplementation 80% of women will have no detectable iron stores at the end of pregnancy, impacting upon peri-partum blood loss and lactation [38, 39].

Conclusions

A significant number of women with iron deficiency anaemia during pregnancy fail to have an adequate response to treatment. The situation persists even when their management is optimized in accordance with national guidance. Women report significant numbers of side effects irrespective of their response to treatment and may be one of the reasons for a failure to respond, although we cannot rule out other factors. The authors of the national guideline highlight the areas of poor-quality evidence in the diagnosis and management of IDA in pregnancy and our results reinforce their comments. We have also found worrying levels of non-response, which clearly demonstrates that more research is required to improve the situation. The problem of how to best manage IDA requires concerted action as many women are being failed by current treatment and therefore remain exposed to higher risks of the associated adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- IDA

Iron deficiency anaemia

- BSH

British Society for Haematology

- Hb

Haemoglobin

- FBC

Full blood count

- TSAT

Transferrin saturation

- CRP

C reactive protein

- TIBC

Total iron binding capacity

- MCV

Mean corpuscular volume

- MCH

Mean corpuscular haemoglobin

- MCHC

Mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration

- MA

Marketing Authorisation

- WiP

Wellbeing in pregnancy

- IMD

Index of multiple deprivation

- PCA

Principle component analysis

- NATA

Network for the advancement of patient blood management haemostasis and thrombosis

- WHO

World Health Organisation

- STROBE

Strengthening reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

Authors' contributions

Author contributions: D.C. designed the project over saw its execution analysed the data and authored the manuscript prior to comments from the study team. S.S. assisted with the design of the project, analysis of the data and co-wrote the final draft of the paper. H.A. and M.M. assisted with the design of the project, recruited and collected data and commented on the final draft of the paper. D.B. carried out the statistical analysis while working at NHS Blood and Transplant and co-authored the final draft of the paper. S.S. coordinated the study set up assisted with the study design and co-authored the final paper, L.D. and J.I. assisted with recruitment, data collection and co-authored the final draft of the paper.

Funding

A grant of £45,00 was awarded by the Rotha Abraham Trust.

Data availability

Data is provided with the manuscript or supplementary information files. All source data can be obtained by request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was granted by the West Midlands– Black Country Ethics committee. Ref number 18/WM/0090. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study in writing using the ethically approved consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Competing Interests. D Churchill was formerly a member of the Multi-disciplinary Iron Deficiency Anaemia Steering (MIDAS) committee supported by Pharmacosmos. All other authors do not have any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Blood Transfusions in Obstetrics. Green-top Guideline No. 47. 2015. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/blood-transfusions-in-obstetrics-green-top-guideline-no-47/

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal Care. NICE guideline [NG201]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng201

- 3.World Health Organization. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1

- 4.Pavord S, Myers B, Robinson S, Allard S, Strong J, Oppenheimer C, et al. UK guidelines on the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(5):588–600. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.09012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavord S, Daru J, Prasannan N, Robinson S, Stanworth SJ, Girling J, et al. UK guidelines on the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy. Br J Haematol. 2020;188(6):819–30. 10.1111/bjh.16221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair M, Churchill D, Robinson S, Nelson-Piercy C, Stanworth SJ, Knight M. Association between maternal haemoglobin and stillbirth: a cohort study among a multi-ethnic population in England. Br J Haematol. 2017;179(5):829–37. 10.1111/bjh.14961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nair M, Choudhury MK, Choudhury SS, Kakoty SD, Sarma UC, Webster P, et al. Association between maternal anaemia and pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study in Assam, India. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(1):e000026. 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haider BA, Olofin I, Wang M, Spiegelman D, Ezzati M, Fawzi WW. Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3443. 10.1136/bmj.f3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huifeng S, Chen L, Wang Y, Sun M, Guo Y, Ma S, et al. Severity of anaemia during pregnancy and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2147046. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lozoff B, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13(3):158–65. 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukowski AF, Koss M, Burden MJ, Jonides J, Nelson CA, Kaciroti N, et al. Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive functioning at 19 years: evidence of long term deficits in executive function and recognition memory. Nutr Neurosci. 2010;13(2):54–70. 10.1179/147683010X12611460763689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCann JC, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relation between iron deficiency during development and deficits in cognitive or behavioural function. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(4):931–45. 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churchill D, Ali H, Moussa M, Donohue C, Pavord S, Robinson SE, et al. Maternal iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy: lessons from a national audit. Br J Haematol. 2022;199(2):277–84. 10.1111/bjh.18391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muñoz M, Peña-Rosas JP, Robinson S, Milman N, Holzgreve W, Breymann, et al. Patient blood management in obstetrics: management of anaemia and haematinic deficiencies in pregnancy and in the post-partum period: NATA consensus statement. Transfus Med. 2018;28(1):22–39. 10.1111/tme.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foxcroft KF, Calloway LK, Byrne NM, Webster J. Development and validation of a pregnancy symptoms inventory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:3. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira DAI, Couto Irving SS, Lomer MCE, Powell JJ. A rapid, simple questionnaire to assess Gastrointestinal symptoms after oral ferrous sulphate supplementation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:103. 10.1186/1471-230X-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alderdice F, McNeill J, Gargan P, Oliver P. Preliminary evaluation of the Well-being in pregnancy (WiP) questionnaire. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(2):133–42. 10.1080/0167482X.2017.1285898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoffel NU, Zeder C, Brittenham GM, Moretti D, Zimmerman MB. Iron absorption from supplements is greater with alternate day dosing in iron deficiency anaemic women. Haematologica. 2020;105(5):1232–9. 10.3324/haematol.2019.220830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdulrehman J, Lausman A, Tang GH, Nisenbaum R, Petrucci J, Pavenski K, et al. Development and implementation of a quality improvement toolkit, iron deficiency in pregnancy with maternal iron optimization (IRON MOM): a before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(8):e1002867. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flores CJ, Sethna F, Stephens B, Saxon B, Hong FS, Roberts T, et al. Improving patient blood management in obstetrics: snapshots of a practice improvement partnership. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2017; e000009. 10.1136/bmjquality-2017-000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camaschella C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1832–43. 10.1056/NEJMra1401038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pena-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM, Garcia-Casal MN, Dowswell T. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7):CD004736. 10.1002/14651858.CD004736.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyder SM, Persson LA, Chowdhury AM, Ekström EC. Do side-effects reduce compliance to iron supplementation? A study of daily- and weekly-dose regimens in pregnancy. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20(2):175–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makrides M, Crowther CA, Gibson RA, Gibson RS, Skeaff CM. Efficacy and tolerability of low-dose iron supplements during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Nutr. 2003;78(1):145–53. 10.1093/ajcn/78.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bresani CC, Braga MC, Felisberto DF, Tavares-de-Melo CE, Salvi DB, Batista-Filho M. Accuracy of erythrogram and serum ferritin for the maternal anemia diagnosis (AMA): a phase 3 diagnostic study on prediction of the therapeutic responsiveness to oral iron in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13: 13. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steer P, Alam MA, Wadsworth J, Welch A. Relation between maternal haemoglobin concentration and birth weight in different ethnic groups. BMJ. 1995;310:489–91. 10.1136/bmj.310.6978.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dewey KG, Oaks BM. U-shaped curve for risk associated with maternal hemoglobin, iron status, or iron supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(Suppl 6):S1694–702. 10.3945/ajcn.117.156075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.n den Broek NR, Letsky EA, White SA, Shenkin A. Iron status in pregnant women: which measurements are valid? Br J Haematol. 1998;103(3):817–24. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volpi E, De Grandis T, Alba E, Mangione M, Dall’Amico D, Bollati C. [Variations in ferritin levels in blood during physiological pregnancy]. Minerva Ginecol. 1991;43(9):387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milman N. Iron and pregnancy - a delicate balance. Ann Hematol. 2006;85(9):559–65. 10.1007/s00277-006-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control. A guide for program managers. 2001. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/iron-children-6to23--archived-iron-deficiency-anaemia-assessment-prevention-and-control

- 31.Nair M, Choudhury SS, Rani A, Solomi C 5th, Kakoty SD, Medhi, et al. The complex relationship between iron status and anemia in pregnant and postpartum women in india: analysis of two Indian study cohorts of uncomplicated pregnancies. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(11):1721–31. 10.1002/ajh.27059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moretti D, Goede JS, Zeder C, Jiskra M, Chatzinakou V, Tjalsma H, et al. Oral iron supplements increase Hepcidin and decrease iron absorption from daily or twice-daily doses in iron-depleted young women. Blood. 2015;126(17):1981–9. 10.1182/blood-2015-05-642223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinar S, Skornick-Rapaport A, Maslovitz S. Iron supplementation in singleton pregnancy: is there a benefit to doubling the dose of elemental iron in iron-deficient pregnant women? A randomized controlled trial. J Perinatol. 2017;37(7):782–6. 10.1038/jp.2017.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez-Ramirez S, Brilli E, Tarantino G, Girelli D, Munoz M. Sucrosomial iron: an updated review of its clinical efficacy for the treatment of iron deficiency. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16: 847. 10.3390/ph16060847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shand AW. Iron preparations for iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy: which treatment is best? Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(7):e471–2. 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanworth SJ, Churchill D, Sweity S, Holmes T, Hudson C, Brown R et al. The impact of different doses of oral iron supplementation during pregnancy: a pilot randomized trial. Blood Adv 2024 Aug 29:bloodadvances2024013408. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2024013408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Bothwell TH. Iron requirements in pregnancy and strategies to Meet them. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(suppl):s257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxmen SR, Branca F, et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided with the manuscript or supplementary information files. All source data can be obtained by request from the corresponding author.