Abstract

Introduction

A significant portion of patients with acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) due to posterior circulation infarction (PCI) is free of non-vestibular signs. A differential diagnosis of this form from that due to vestibular neuritis (VN) can be challenging. We herein aimed to understand whether quantitative eye movement signature could be used to assist such a diagnosis.

Methods

A total of 56 patients with AVS due to PCI free of non-vestibular signs, 71 patients with AVS due to VN, and 127 controls were selected retrospectively into the study from our hospital database. Demographic, clinical data, and videooculography results were extracted.

Results

Patients with PCI or VN differed from controls in most eye movement metrics. Patients with PCI also differed from those with VN in multiple metrics, including contralesional speed of horizontal saccade, gain of downward saccade, speed and gain of upward saccade, contralesional gain and gain asymmetry of smooth pursuit, and ipsilesional gain of optokinetic nystagmus. A detection model, built on the basis of age, hypertension, gain of upward saccade, and gain asymmetry of smooth pursuit, distinguished PCI from VN with area under the curve at 0.964 (0.929, 0.998) and 0.961 (0.915, 1.000) in the training and test sessions, respectively.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that eye movements are differentially impaired in patients with PCI free of non-vestibular signs and those with VN. The detection model built on smooth pursuit gain asymmetry and upward saccade gain may assist the differentiation between PCI and VN in AVS patients by trained clinicians.

Keywords: Stroke, Peripheral origin, Retrospective analysis, Side of lesion, Diagnosis modeling

Introduction

Acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) can originate from peripheral or central nervous system and is characterized by sustained vertigo, nausea and vomiting, spontaneous nystagmus, and postural instability lasting longer than 24 h [1]. This syndrome accounts for 10–25% of dizziness in the emergency department [2, 3]. Peripherally originated AVS is most frequently caused by vestibular neuritis (VN) while centrally originated AVS is mainly caused by stroke. Among the stroke causes, posterior circulation infarction (PCI) accounts for the most cases. PCI is typically considered as the infarction that occurs within the vascular territory supplied by the vertebrobasilar arterial system [4]. The pathophysiology of PCI is basically associated with the blockage caused by mechanical factors such as emboli and thrombi or the alterations in blood pressure, which reduces blood supply to a brain area, ultimately leading to tissue necrosis and an irreversible loss of neuronal function [5]. About 20% of AVS patients caused by PCI is free of nonvestibular signs. These patients may be associated with lesions in such brain areas as cerebellum, medulla, pons, and occipital lobe [6]. It is challenging to quickly distinguish these patients from those with VN because both conditions are mainly manifested with long sustained vertigo [7]. A population-based cross-sectional study has reported that AVS patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack are often incorrectly diagnosed, estimating to initially miss about 35% of such patients [8].

Patients with PCI demand immediate intervention, including thrombolysis [9], early secondary prevention [10, 11], and surgical treatment of stroke complications from malignant edema [12]. Delaying such treatments may significantly increase disability and mortality of the patients. Although patients with infarction can be diagnosed with brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI), they are costly and may not be immediately available for every AVS patient in an emergency department, particularly in underequipped hospitals [13]. Therefore, a well-maneuverable and cost-effective approach to differentiate PCI from VN would greatly facilitate the emergency department in determining treatment protocols.

Eye movement allows us to track objects of interest by combining smooth pursuits (slow eye movement), saccades (fast eye movement), and optokinetic nystagmus (involuntary eye movement responsible for stabilizing retinal images in the presence of relative motion) [14–16]. Multiple approaches have been developed for the differential diagnosis between patients with central and peripheral vertigo [17–20]. Among two simple bedside oculomotor-based approaches, HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus and test of skew; a protocol for specialists in neuro-otology) and STANDING (spontaneous nystagmus, direction, head-impulse, standing; the only validated protocol for non-specialist healthcare professionals and also applicable in the emergency room), showed high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of stroke in vertigo patients [17, 18]. Later, video head-impulse test (vHIT), a diagnostic test providing objective data versus the head-impulse test which is a bedside, manual test for quick assessment, was proposed to distinguish stroke with AVS based on the vestibulo-ocular reflex gain and saccade prevalence [19]. Eye movement is controlled by cortical and subcortical regions of the brain including the vestibular nuclei and the cerebellum [14, 15]. Hence, eye movements have been observed with a high frequency of abnormalities in patients with PCI and VN [21–25], and have been compared between different disorders. For instance, the frequency of vertical smooth pursuit deficit was higher in vestibular pseudoneuritis cases including infarction, multiple sclerosis, and hemorrhage than in VN cases [20]; PCI cases including either with or without non-vestibular signs had increased abnormalities in saccade, smooth pursuit, and optokinetic nystagmus compared with VN cases [26]; abnormal vertical smooth pursuit was detected frequently in PCI cases without brainstem signs, but much less in VN cases [24]; and PCI cases without non-vestibular signs had increased abnormalities in smooth pursuit compared with AVS cases with all peripheral causes [27]. However, it remains elusive how eye movements are quantitatively impaired in patients with PCI free of non-vestibular signs and those with VN, and whether a quantitative eye movement signature could be used to differentiate the PCI from VN.

In this study, we screened our hospital database and selected qualified patients with PCI free of non-vestibular signs or with VN and control subjects, followed by the extraction of videooculography-based quantitative eye movement data. We aimed to understand eye movement differences among the cohorts to build a detection model to diagnose this type of PCI from VN.

Materials and methods

Patients and data acquisition

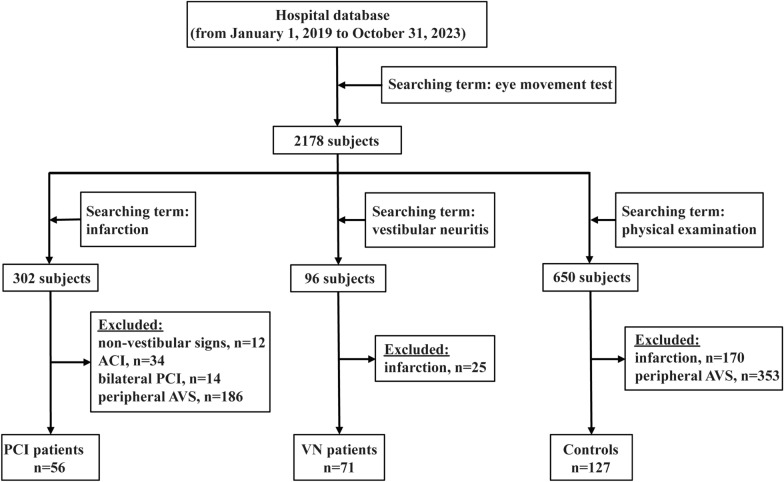

Data were acquired by searching for records of patients who underwent eye movement tests from January 1st, 2019 to October 31st, 2023, in the database of Wenzhou Central Hospital. Of the 2178 records obtained, further exploration with the use of the terms “infarction”, “vestibular neuritis”, and “physical examination”, respectively, resulted in 302, 96, and 650 hits. All patients underwent brain MRI and DWI within 72 h of presentation at our hospital. For the “infarction” group, we excluded those with non-vestibular signs, anterior circulation infarction, bilateral PCI, and peripheral AVS history or alike symptoms, leading to the identification of 56 AVS patients with PCI free of non-vestibular signs. Non-vestibular signs meant abnormal signs other than vertigo, nausea and vomiting, spontaneous nystagmus, and postural instability, such as unilateral limb weakness, limb sensory deficit, dysarthria, visual field loss, hearing loss, and lethargy [28]. PCI was defined by abnormal DWI and hypointense apparent diffusion coefficient map in vertebrobasilar artery territory, supplemented by T2-weighted sequences [29]. For the “vestibular neuritis” group, we excluded those with a history of infarction or with a newly diagnosed infarction and identified 71 AVS patients due to VN. VN was defined by the presence of nystagmus, a positive head-impulse test, and a negative neurologic examination [30], and its diagnosis required caloric test [31]. Patients all showed unilateral ipsilesional caloric hypoexcitability. For the “physical examination” group, we excluded those with a history of infarction, peripheral AVS or similar signs and symptoms and identified 127 subjects as controls (Fig. 1). The physical examination included measuring height and weight, reviewing medical history and family medical history, identifying medications currently taken, checking vital signs, evaluating organ systems by auscultation, inspection, palpation, and percussion, laboratory tests including blood tests, urinalysis, and stool examination, electrocardiogram, ultrasonic examination, X-ray, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, and other special examinations if needed. The side with infarction in DWI in patients with PCI and the slow phase side of spontaneous nystagmus in patients with VN were determined as the side of lesion. We did not find records of eye diseases or surgeries among these subjects, which otherwise would have been excluded. Information of the included subjects, including eye movement metrics and demographic and clinical features, was then collected.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for the inclusion of AVS patients with PCI free of non-vestibular signs or with VN, and controls. ACI, anterior circulation infarction; AVS, acute vestibular syndrome; PCI, posterior circulation infarction; VN, vestibular neuritis

Eye movement examination

The study was a retrospective analysis of hospital records. Patients were visually checked for nystagmus when being hospitalized. Videooculography was performed within one week of hospitalization using a videonystagmography system (VO425, Interacoustics; sampling rate, 174 Hz). The standard operation procedure for this examination in our hospital was as follows: the subjects were required to refrain from drinking alcohol and taking those drugs related to central nervous system excitation or inhibition in the previous 48 h, and there were no contraindications associated with the investigation. During the test, the subjects wore goggles while sitting about 120 cm from the monitor in a dark room. They were instructed to move their eyes for calibration and testing procedures. The frequency of object/stimulus movement was lower than 80 Hz, which theoretically would ensure that the videonystagmography system was sufficient for accurately capturing rapid eye movements. All patients underwent the spontaneous nystagmus test and were assessed with the same eye movement paradigm for both eyes. To test for saccades, the subjects were asked to track the objects moving rapidly in horizontal and vertical directions, and the indicators were latency (ms), velocity (°/s), and gain (%). The object movement amplitude was 10°–60° and velocity was 800°/s. To test for smooth pursuit, the subjects were asked to track a target moving in a horizontal direction with a sine wave, and the indicator was gain (%). The target movement amplitude was 30° and velocity was 10–30°/s. To test for optokinetic nystagmus, the subjects were asked to look to where they thought was straight ahead while presented with a visual stimulus consisting of two differently colored stripes that moved continuously, and the indicator was gain (%). The stripe movement velocity was 50°/s. All eye movement tests were performed in the next several days for those who had difficulty completing at the first attempt. Data of left and right metrics for both eyes were acquired for health controls. The asymmetry index was determined as the ratio of measurements of |(left–right)/(left + right)|× 100 for all subjects.

Demographic and clinical feature analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R (v.4.3.1). Shapiro–Wilk test was used for normality analysis. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Statistical difference was assessed by Wilcoxon test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Eye movement metrics analyses

Eye movement metrics were calculated and presented after handling missing values through median filling method as certain eye movements were not measured in some records. Data presentation and significance definition were the same as described above. Difference was determined by Wald test using logistic regression analysis adjusted with appropriate clinical features for comparisons between PCI and VN cases and controls.

Diagnosis modeling

Since the side of the lesion is usually not known at the time when the diagnosis needs to be made, the variables initially entering into modeling should be those independent of the side of the lesion. These variables included the asymmetry indexes as defined above and the vertical saccade metrics. Logistic regression was used to build the diagnosis model. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC), area under the curve (AUC) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and precision were calculated using pROC and ROCR packages. The vif function in Companion to Applied Regression package was used to calculate the variance inflation factor for evaluating multicollinearity between variables. The differential asymmetry indexes, vertical saccade metrics, and differential demographic and clinical features were used as initial variables for modeling. The model was built by the following procedures: (1) subjects were randomly divided into a training set and a test set with a ratio of 6 to 4; (2) the variables were simplified by multivariate logistic regression analysis with a backward method; and (3) these two steps were repeated 40 times, and the models were selected with no redundancy (i.e., defined as variance inflation factor < 10) among variables. The best model and its variables were selected based on the overall performance in model indicators with the use of Youden index as the cut-point, specificity with the use of 100% sensitivity as the cut-point, and simplicity of the model variables. The model was then applied for diagnosis using the test set.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The cohort contained 56 patients with AVS due to PCI free of non-vestibular signs, 71 patients with AVS due to VN, and 127 controls. The time of performing videooculography after hospitalization was 1 day with interquartile range (1, 2.75) in the PCI group and 1 day with interquartile range (0, 3) in the VN group (details in Supplementary Table 1). No significant difference was found in between (P = 0.219). Although this cohort differed (P < 0.05) in age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease, other characteristics including smoking and drinking history, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation were not significantly different among the three groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with PCI or VN, and controls

| PCI (n = 56) | VN (n = 71) | Ctrl (n = 127) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± standard deviation) | 70.0 ± 11.5 | 53.0 ± 14.0 | 65.5 ± 12.2 | < 0.001a |

| Gender (female/male) | 20/36 | 20/51 | 74/53 | < 0.001b |

| History of smoking, n (%) | 15 (26.8) | 13 (18.3) | 22 (17.3) | 0.314b |

| History of drinking, n (%) | 13 (23.2) | 8 (11.3) | 15 (11.8) | 0.089b |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 41 (73.2) | 29 (40.9) | 72 (56.7) | 0.001b |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 19 (33.9) | 7 (9.9) | 31 (24.4) | 0.004b |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 17 (30.4) | 30 (42.3) | 41 (32.3) | 0.275b |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0.205c |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 44 (78.6) | 28 (39.4) | 58 (45.7) | < 0.001b |

Ctrl, control; PCI, posterior circulation infarction; VN, vestibular neuritis

aAnalyzed by one-way ANOVA

bAnalyzed by Chi-square test

cAnalyzed by Fisher’s exact test

Analyses of eye movements in the patients and controls

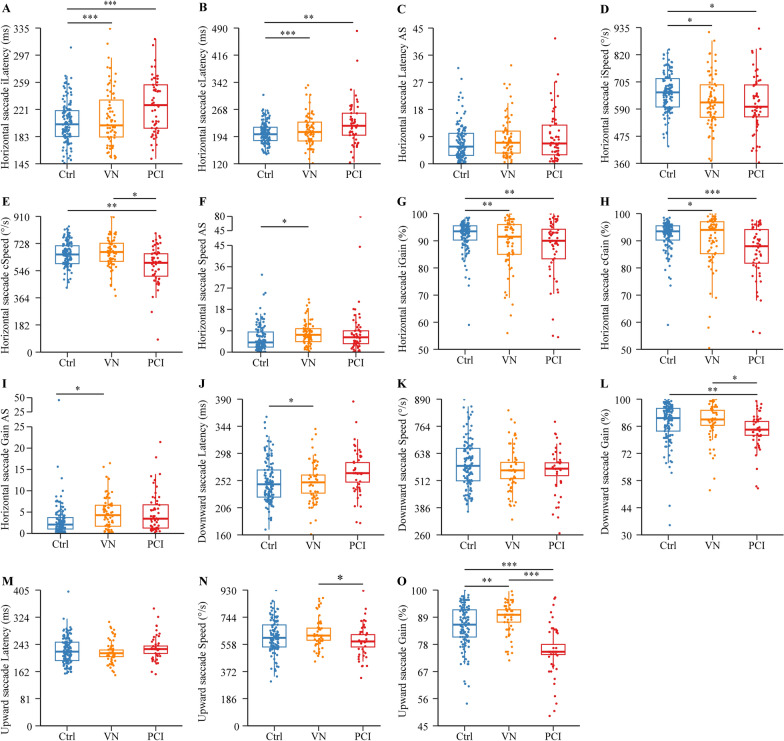

We did not find cases who had a change in the direction of the slow phase of nystagmus by the videooculography examination compared with the visual checking when being hospitalized, suggesting that no recovery nystagmus occurred in these patients. Eye movement analyses revealed that most eye movement metrics were significantly different between patients with PCI or VN and controls (P < 0.05; Figs. 2 and 3, and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3; raw data provided in Supplementary Table 1). Among them, contralesional speed of horizontal saccade (Fig. 2E), gain of downward saccade (Fig. 2L), and ipsilesional gain of smooth pursuit (Fig. 3A) were different from controls in the PCI group (P < 0.05) but not in the VN group. Speed and gain asymmetry of horizontal saccade (Fig. 2, F and I), latency of downward saccade (Fig. 2J), and ipsilesional gain of optokinetic nystagmus (Fig. 3D) were different from controls in the VN group (P < 0.05) but not in the PCI group. Between the PCI and VN groups, differences were found in contralesional speed of horizontal saccade (P = 0.033; Fig. 2E), gain of downward saccade (P = 0.029; Fig. 2L), speed (P = 0.018; Fig. 2N) and gain (P < 0.001; Fig. 2O) of upward saccade, contralesional gain (P < 0.001; Fig. 3B) and gain asymmetry (P < 0.001; Fig. 3C) of smooth pursuit, and ipsilesional gain of optokinetic nystagmus (P < 0.001; Fig. 3D).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of horizontal and vertical saccade in patients with PCI or VN, and controls. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and were analyzed by binary logistic regression adjusted with age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. AS, asymmetry; c, contralesional; Ctrl, control; i, ipsilesional; PCI, posterior circulation infarction; VN, vestibular neuritis

Fig. 3.

Comparison of smooth pursuit and optokinetic nystagmus in patients with PCI or VN, and controls. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and were analyzed by binary logistic regression adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. AS, asymmetry; c, contralesional; Ctrl, control; i, ipsilesional; PCI, posterior circulation infarction; VN, vestibular neuritis

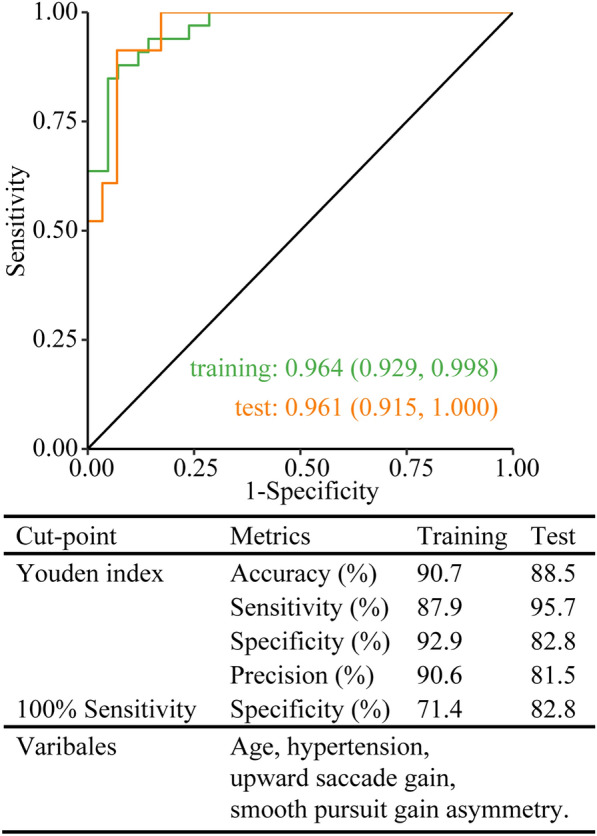

Classification analyses using differential eye movement metrics

Only clinically useful metrics should be entered into the model, which would exclude those that assume that the lesion side would be known. Therefore, only differential asymmetry indexes and vertical saccade metrics were qualified for modeling. We thus included gain of downward saccade, speed and gain of upward saccade, as well as gain asymmetry of smooth pursuit. Initial variables also included age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease. After simplification, the best model contained age, hypertension, gain of upward saccade, and gain asymmetry of smooth pursuit as variables. The AUCs distinguishing PCI from VN were 0.964 (0.929, 0.998) and 0.961 (0.915, 1.000), respectively, in the training and test session. The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and precision were all above 81.5% with the use of Youden index as the cut-point. The specificity was 71.4% and 82.8%, respectively, in the training and test session with 100% sensitivity as the cut-point (Fig. 4, Table 2).

Fig. 4.

ROC analysis for PCI free of non-vestibular signs and VN. PCI, posterior circulation infarction; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; VN, vestibular neuritis

Table 2.

The differential eye movements and clinical features after backward elimination

| Variable set | B | WALD | P | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCI vs. VN | Age | 0.104 | 8.073 | 0.004 | 1.109 (1.040, 1.205) |

| Hypertension | 1.662 | 2.626 | 0.105 | 5.271 (0.810, 53.243) | |

| Upward saccade gain | -0.172 | 9.842 | 0.002 | 0.842 (0.740, 0.924) | |

| Smooth pursuit gain asymmetry | -0.173 | 5.777 | 0.016 | 0.841 (0.710, 0.949) |

B, regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PCI, posterior circulation infarction; VN, vestibular neuritis

Correlation analysis of horizontal nystagmus with smooth pursuit

Among the PCI patients, 19 (33.9%) patients had spontaneous nystagmus, including 8 ipsilesional nystagmus, 9 contralesional nystagmus, and 2 torsional nystagmus. In contrast, nearly all VN patients (69; 97.2%) had contralesional horizontal nystagmus, except 2 cases showing contralesional, downbeat-torsional nystagmus. We then performed a correlation analysis between spontaneous horizontal nystagmus slow-phase velocity and smooth pursuit gain asymmetry index and found a moderately positive correlation between them (r = 0.448, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 1). This result suggests that greater pursuit asymmetry in the VN group than in the PCI group may be due to the interference of spontaneous nystagmus.

Discussion

Fast diagnosis of PCI free of non-vestibular signs from VN in AVS patients remains challenging in the emergency department. A videonystagmography system is not prohibitively expensive for broader adoption and costs significantly far less than an MRI system. In this study, we retrospectively and quantitatively analyzed eye movements in the patients with PCI and VN and controls from our hospital database and demonstrated that a detection model that was built upon gain of upward saccade, gain asymmetry of smooth pursuit, age, and hypertension measures could differentiate PCI from VN in our dataset.

Our patients with PCI or VN are impaired in many types of eye movement. Abnormal eye movements have been reported in the AVS patients, showing defects in horizontal and vertical saccades, horizontal and vertical smooth pursuit, and optokinetic nystagmus in patients with PCI [21–24, 32], and contralesional optokinetic nystagmus velocity in patients with VN [25]. We also noted that the speed and gain asymmetry of horizontal saccades and the latency of downward saccades differed between the VN and control groups. Indeed, patients with peripheral vestibular dysfunction may exhibit abnormal latency and gain in randomized saccades [33]. Vestibular neurons in the vestibular nuclei, as part of the saccadic system, project vestibular and eye position-related signals to the intermediate interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) [14] and receive signals from the peripheral vestibular ganglion through the vestibular nerve [34]. Lesions in the vestibular nerve and vestibular ganglion due to VN may therefore affect saccadic performance. Most previous studies classify eye movements as “abnormal” followed by frequency calculation but not by quantitative presentation of first-hand data. We herein provide a detection model built on the basis of age, hypertension, gain of upward saccade, and gain asymmetry of smooth pursuit to differentiate PCI from VN, suggesting that the videooculography-based eye movement signature could be applicable to separate these two causes in clinic. This is particularly valuable when MRI is not readily available. The model also yielded fair specificity when not a single central AVS case is missed.

The aforementioned oculomotor-based bedside examination, HINTS, has been used to diagnose stroke in AVS patients, who presumably display normal horizontal head-impulse test, direction-changing nystagmus, and skew deviation (vertical ocular misalignment). The method was reported to have a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 96%, whereas early DWI only showed a sensitivity of 72% [18]. Nonetheless, covert catch-up saccades may lead to a false-negative bedside head impulse [35]. In contrast, vHIT and videooculography HINTS can both circumvent this problem [36–38]. The combined assessment of vestibulo-ocular reflex gain and saccade prevalence using vHIT may separate VN from posterior circulation stroke, with both the sensitivity and specificity being 90.9% [19], while videooculography HINTS may detect stroke in AVS patients with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 88.9% [38]. The other aforementioned approach, STANDING, requires four steps, including the discrimination between spontaneous and positional nystagmus, the evaluation of the nystagmus direction, the head-impulse test, and the evaluation of equilibrium (standing). Using this approach, non-subspecialists could achieve a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 87% to exclude threatening cerebral diseases in a large cohort of patients presenting with vertigo or unsteadiness [17]. However, confusion may occur if testing horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is mistakenly performed [39]. There also exist other algorithms, such that a feed-forward neural net classifier with gaze-evoked nystagmus, smooth pursuit, head-impulse test, skew deviation, and subjective visual vertical has been used to differentiate VN and central vestibular pseudoneuritis [20]. In comparison, the performance in our gain of upward saccade and smooth pursuit gain asymmetry-based model, having a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 82.8% to 95.7% in the training and test session, may be comparable to vHIT and STANDING but is not better than both bedside and videooculography HINTS. The existing protocols such as HINTS and STANDING have already demonstrated a high diagnostic accuracy but also contain their own limitations as above mentioned. Thus, the current model represents a new effort and at least can be used as a supplement to distinguish PCI from VN in daily clinical practice. In addition, it is of future interest to explore a videooculography-based combination of our model and vHIT.

The gain of upward saccade and horizontal smooth pursuit gain asymmetry are the relevant eye movement markers in our model. A higher abnormal frequency of saccades in patients with PCI than with VN has been previously demonstrated [26]. Interestingly, upward saccades appear to be more affected in patients with infarction in the unilateral medial thalamus [40], while downward saccades are often affected more than upward saccades in patients with impairment in the rostral interstitial nucleus of the MLF in the midbrain [41]. Neurons of this midbrain nucleus generate premotor commands for vertical saccades; the medial thalamus is on the traversing passage of the corticofugal fibers to the rostral midbrain structures [40, 41]. Nevertheless, our cohort has no cases specifically lesioned in these two loci. We regretfully could not provide a better explanation at this time for why upward saccades differentiate PCI from VN more effectively than downward or horizontal saccades. The fast phases of horizontal nystagmus usually occur toward the contralesional side in patients with VN regardless of the gaze direction, whereas the directions of fast phase nystagmus and gaze often change in parallel in patients with PCI [1]. Studies have suggested that smooth pursuit gain on the fast phase direction of nystagmus is impaired [42, 43]. These results are in line with ours that horizontal nystagmus intensity was moderately positively correlated with smooth pursuit gain asymmetry. Hence, greater pursuit asymmetry in the VN group than in the PCI group is possibly attributed to the direction-fixed spontaneous nystagmus, rather than impairment of central pursuit pathways.

This study contains certain limitations. First, this is a retrospective data analysis that assessed eye movement testing with a delay of up to several days after symptom onset. The appearance of eye movements may change over time. Therefore, eye movement expression during that time warrants further investigation. Second, although a videonystagmography system is considerably cheaper than an MRI, it requires a specific environment (dark room with visual target display) and specialized training for clinicians (neurology, otology, audiology) to perform accurately, which most emergency departments do not have immediate access to. Well-trained clinicians can avoid delays in decision-making (e.g., use of alteplase for intravenous thrombolysis in strokes) and have been shown to appropriately differentiate peripheral from central causes in AVS [44]. In addition, a video nystagmography result reflects the function, and an MRI is structural. One cannot replace the other. Third, the scope of the use of eye movement is limited to differentiate unilateral PCI from VN. Conditions such as anterior circulation infarction and bilateral PCI, and patients with both VN and infarction should be predetermined and excluded. Mistaken inclusion of these conditions may lead to incorrect diagnosis using our model. In the future, we would further validate the model by involving larger multi-center cohorts.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates in a quantitative manner that eye movements are differentially impaired in patients with PCI free of non-vestibular signs and those with VN. The upward saccade gain and smooth pursuit gain asymmetry-based detection model could potentially diagnose this type of PCI from VN. Our findings suggest that videooculography combined with the detection model may be an assisting option in the emergency unit.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the colleagues who managed the patients and collected the data.

Author contributions

MMJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft; XLM, QQZ, XDH, SLZ, SSH, and WC: Investigation, Formal analysis; DLZ, YLS and YYZ: Methodology, Formal analysis; XZ: Supervision, Funding acquisition; JHZ: Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition; all authors: Writing—Review & Editing.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LZ25H090005 and ZCLZ25H2502) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82271282 and 82471617).

Data availability

All data and materials supporting the conclusions are included in the manuscript. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Wenzhou Central Hospital (approval No. L2023-04–052). All data used in this study were acquired from the hospital database and were de-identified appropriately; thus, no informed consent from subjects was obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiong Zhang, Email: xiongzhang@wmu.edu.cn.

Jian-Hong Zhu, Email: jhzhu@wmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Hotson JR, Baloh RW. Acute vestibular syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):680–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ. 2011;183(9):E571–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantokoudis G, Otero-Millan J, Gold DR. Current concepts in acute vestibular syndrome and video-oculography. Curr Opin Neurol. 2022;35(1):75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Front Neurol. 2014. 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuriakose D, Xiao Z. Pathophysiology and treatment of stroke: present status and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. 10.3390/ijms21207609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J-H, Kim H-W, Choi K-D, Kim M-J, Choi YR, Cho H-J, et al. Isolated vestibular syndrome in posterior circulation stroke. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4(5):410–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saber Tehrani AS, Kattah JC, Kerber KA, Gold DR, Zee DS, Urrutia VC, et al. Diagnosing stroke in acute dizziness and vertigo: pitfalls and pearls. Stroke. 2018;49(3):788–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerber KA, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Smith MA, Morgenstern LB. Stroke among patients with dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department: a population-based study. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2484–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuruvilla A, Bhattacharya P, Rajamani K, Chaturvedi S. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of acute stroke in young adults. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20(6):523–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, Geraghty O, Redgrave JNE, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1432–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavallée PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, Cabrejo L, Olivot J-M, Simon O, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):953–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijdicks EFM, Sheth KN, Carter BS, Greer DM, Kasner SE, Kimberly WT, et al. Recommendations for the management of cerebral and cerebellar infarction with swelling. Stroke. 2014;45(4):1222–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman-Toker DE. Missed stroke in acute vertigo and dizziness: it is time for action, not debate. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(1):27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moschovakis AK, Scudder CA, Highstein SM. The microscopic anatomy and physiology of the mammalian saccadic system. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50(2–3):133–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lisberger SG. Visual guidance of smooth-pursuit eye movements: sensation, action, and what happens in between. Neuron. 2010;66(4):477–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C, Triesch J, Shi BE. An active-efficient-coding model of optokinetic nystagmus. J Vis. 2016;16(14): 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanni S, Pecci R, Edlow JA, Nazerian P, Santimone R, Pepe G, et al. Differential diagnosis of vertigo in the emergency department: a prospective validation study of the STANDING algorithm. Front Neurol. 2017. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh Y-H, Newman-Toker DE. Hints to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3504–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calic Z, Nham B, Bradshaw AP, Young AS, Bhaskar S, D’Souza M, et al. Separating posterior-circulation stroke from vestibular neuritis with quantitative vestibular testing. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(8):2047–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cnyrim CD, Newman-Toker D, Karch C, Brandt T, Strupp M. Bedside differentiation of vestibular neuritis from central “vestibular pseudoneuritis.” J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(4):458–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SJ, Yeom MI, Lee SU. A case of double depressor palsy followed by pursuit deficit due to sequential infarction in bilateral thalamus and right medial superior temporal area. Int Ophthalmol. 2017;37(6):1353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S-H, Park S-H, Kim J-S, Kim H-J, Yunusov F, Zee DS. Isolated unilateral infarction of the cerebellar tonsil: ocular motor findings. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(3):429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham TD, Trobe JD. Selective unidirectional horizontal saccadic paralysis from acute ipsilateral pontine stroke. J Neuroophthalmol. 2017;37(2):159–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Lee W, Chambers BR, Dewey HM. Diagnostic accuracy of acute vestibular syndrome at the bedside in a stroke unit. J Neurol. 2010;258(5):855–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnusson M, Pyykkö I. Velocity and asymmetry of optokinetic nystagmus in the evaluation of vestibular lesions. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;102(1–2):65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling X, Sang W, Shen B, Li K, Si L, Yang X. Diagnostic value of eye movement and vestibular function tests in patients with posterior circulation infarction. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019;139(2):135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norrving B, Magnusson M, Holtås S. Isolated acute vertigo in the elderly; vestibular or vascular disease? Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91(1):43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Searls DE. Symptoms and signs of posterior circulation ischemia in the New England Medical Center posterior circulation registry. Arch Neurol. 2012. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, Luby M, Butman JA, Demchuk AM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):293–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baloh RW. Vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):1027–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichijo H (2018) Vestibular Rehabilitation for the Patients with Intractable Vestibular Neuritis. Int J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 7(6): 350–8

- 32.Su CH, Young YH. Clinical significance of pathological eye movements in diagnosing posterior fossa stroke. Acta Otolaryngol. 2013;133(9):916–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuma VC, Ganança CF, Ganança MM, Caovilla HH. Oculomotor evaluation in patients with peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72(3):407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Díaz C, Puelles L. Segmental analysis of the vestibular nerve and the efferents of the vestibular complex. Anat Rec. 2018;302(3):472–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber KP, Aw ST, Todd MJ, McGarvie LA, Curthoys IS, Halmagyi GM. Head impulse test in unilateral vestibular loss. Neurology. 2008;70(6):454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L, Halmagyi GM. Video head impulse testing: from bench to bedside. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(01):005–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halmagyi GM, Chen L, MacDougall HG, Weber KP, McGarvie LA, Curthoys IS. The video head impulse test. Front Neurol. 2017. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korda A, Wimmer W, Zamaro E, Wagner F, Sauter TC, Caversaccio MD, et al. Videooculography “HINTS” in acute vestibular syndrome: a prospective study. Front Neurol. 2022. 10.3389/fneur.2022.920357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herdman D. Advances in the diagnosis and management of acute vertigo. J Laryngol Otol. 2024;138(S2):S8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deleu D. Selective vertical saccadic palsy from unilateral medial thalamic infarction: clinical, neurophysiologic and MRI correlates. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;96(5):332–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salsano E, Umeh C, Rufa A, Pareyson D, Zee DS. Vertical supranuclear gaze palsy in Niemann-Pick type C disease. Neurol Sci. 2012;33(6):1225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bttner U, Grundei T. Gaze-evoked nystagmus and smooth pursuit deficits: their relationship studied in 52 patients. J Neurol. 1995;242(6):384–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasauer S, Hoshi M, BÜTtner U. Smooth pursuit in patients with downbeat nystagmus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1039(1):532–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarnutzer AA, Gold D, Wang Z, Robinson KA, Kattah JC, Mantokoudis G, et al. Impact of clinician training background and stroke location on bedside diagnostic test accuracy in the acute vestibular syndrome—a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2023;94(2):295–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials supporting the conclusions are included in the manuscript. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.