Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of 3D-printed guide plate-assisted descending INFIX technology in the management of unstable pelvic ring injuries.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed the clinical data of 51 patients who underwent INFIX surgery for pelvic ring fractures at the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University between January 2023 and December 2024. Based on the use of 3D-printed guide plates, the patients were divided into two groups: conventional group (n = 28) and guide plate group (n = 23). The surgical parameters, including operative time, number of intraoperative fluoroscopic evaluations, intraoperative blood loss, and incision length, were recorded and compared between the two groups. The postoperative reduction accuracy was evaluated using the Matta imaging scoring system, while the Majeed scoring system was used to obtain functional outcomes in clinical follow-up. All the potential complications were identified and evaluated accordingly.

Results

Both the patient groups were followed up for a period of 6–11 months, with an average of 8 months. The guide plate group demonstrated shorter surgery duration, fewer fluoroscopic assessments, and fewer guide needle trajectory adjustments compared to the conventional group (P < 0.05). The guide plate group exhibited a higher percentage of good Matta scores than the conventional group (17.39% vs. 14.29%).

Conclusions

The individualized 3D-printed navigation template significantly reduced the complexity of INFIX surgery, minimized intraoperative and postoperative complications, and enhanced clinical outcomes. The procedure can be safely performed in resource-limited medical facilities, making it feasible for junior surgeons with limited pelvic anatomy experience.

Keywords: 3D print, INFIX, Pelvic fracture, Internal fixation, Anterior ring injury

Introduction

Unstable pelvic ring fractures are typically associated with high-energy trauma, accounting for approximately 1.5–3.9% of all fractures. However, these injuries have relatively high mortality and disability rates [1]. Therefore, optimizing the treatment of pelvic fractures is crucial for improving patient prognosis and reducing clinical mortality. The posterior pelvic ring contributes to 60% of pelvic stability, while the anterior pelvic ring accounts for 40% [2].

Anteroposterior compression, lateral compression, and vertical shear injuries of the pelvis (AO/OTA B1–3, C1–3) often necessitate fixation of the anterior pelvic ring [3]. INFIX serves as an effective method for the definitive treatment of anterior pelvic ring injuries. This technique provides a safe and straightforward approach for managing complex pelvic ring fractures, offering stable fixation, satisfactory osseointegration, and sufficient functional outcomes, even in unstable pelvic ring injuries [4]. However, the minimally invasive INFIX procedure has a steep learning curve, requires a high level of surgical expertise, and involves prolonged radiation exposure. Potential complications include improper screw positioning and inadvertent vascular or nerve injury. Pedicle screw placement, in particular, should be performed by experienced surgeons, posing a challenge for less experienced physicians. Additionally, repeated fluoroscopy is necessary throughout the procedure, increasing intraoperative radiation exposure for patients and surgeons. The technique also carries risks of damage to adjacent blood vessels, nerves, and pelvic organs, postoperative complications, and the need for advanced imaging support, making its implementation challenging in resource-limited healthcare settings.

The use of 3D printing guide plate technology enhances surgeons’ understanding of the three-dimensional anatomy of pelvic structures, shortens the learning curve, and allows for continuous refinement of surgical planning [5]. To facilitate the INFIX procedure and improve the accuracy of sacroiliac screw placement, this study proposed the bone-shaped groove between the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior inferior iliac spine as a navigation template for guide plate design.

This retrospective study analyzed the clinical outcomes of 51 patients with pelvic ring fractures, evaluating the effectiveness of 3D-printed guide plate-assisted descending INFIX technology in the management of unstable pelvic ring injuries.

Materials and methods

General information

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (Approval No.: [2025]YX No. 239) and conforms to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (revised 2013). All eligible patients who agreed to participate provided written informed consent.

This retrospective study analyzed the clinical data of 51 patients who underwent INFIX surgery for pelvic ring fractures at the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University between January 2023 and December 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age > 18 years; (2) Preoperative diagnosis of anterior pelvic ring fracture with minimal displacement. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Severe osteoporosis; (2) Coagulation dysfunction; (3) Presence of infection signs. The cohort included 33 males and 18 females, aged 19 to 76 years, with a mean age of 42.1 years. All cases involved high-energy trauma as the cause of pelvic ring injury.

Patients were categorized into two groups based on the use of 3D-printed guide plates: the conventional group (n = 28) and the guide plate group (n = 23). The guide plate group included 20 cases of Tile type B and 3 cases of Tile type C, while the conventional group involved 25 cases of Tile type B and 3 cases of Tile type C. The baseline characteristics, including gender, age, injury mechanism, fracture classification (Tile type), and time from injury to surgery, are listed in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the guide plate and conventional groups (P > 0.05), indicating comparability between the cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Group | n | Gender (M/F) | Age (years) Mean ± SD |

Injury Cause | Tile Classification (n) | Time from Injury to Surgery (days) Mean ± SD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Traffic | Fall | Crush | Tile B | Tile C | ||||

| Guide | 23 | 13 | 10 | 43.1 ± 15.9 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 3.7 ± 1.4 |

| Conv. | 28 | 20 | 8 | 41.4 ± 15.4 | 13 | 12 | 3 | 25 | 3 | 3.7 ± 1.6 |

| χ²/t-value | 0.663 | 0.376 | 0.059 | 0 | 0.187 | |||||

| P-value | 0.416 | 0.709 | 0.971 | 1 | 0.853 | |||||

Method

Preoperative design and navigation template production

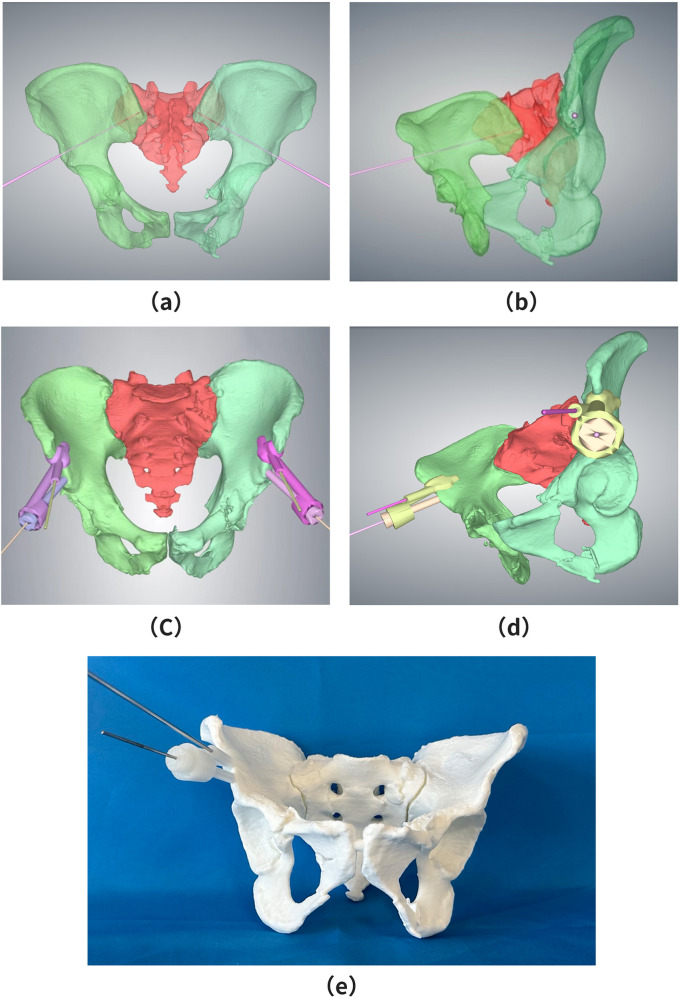

Upon hospital admission, all patients underwent preoperative CT imaging and three-dimensional reconstruction. A 3D pelvic model was generated using Mimics software, and a virtual screw channel was created in 3-Matic by placing a cylindrical structure of appropriate diameter within the model. The cylinder’s position was adjusted to ensure it was centered within the virtual channel, maintaining a diameter of 2 mm at the pelvic teardrop position (see Figs. 1(a) and (b)).

Fig. 1.

Design of the Navigation Template and 3D Pelvic Model. (a) A 2 mm cylinder was positioned at the center of the teardrop region to construct a virtual screw insertion channel. (b) Lateral view of the virtual screw channel within the three-dimensional pelvic model (c) Navigation template and hollow guide tube were designed based on the central channel of the teardrop region. The template base was secured to the bone groove between the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior inferior iliac spine, with a 2.5 mm positioning Kirschner pin channel constructed adjacent to the base. (d) Lateral view of the 3D-printed navigation template and the three-dimensional pelvic model, demonstrating preoperative surgical simulation

The screw position within the virtual channel was assessed across three CT planes, sagittal, coronal, and transverse, to confirm that it did not breach the cortical bone or enter the joint cavity at any level. Based on the simulated screw placement process in the 3D pelvic model, the screw entry point and an anatomically accurate guide plate were designed. This included a base component and a hollow guide tube. After fitting these components, an individualized positioning guide plate with a guide hole was developed.

The bone-shaped groove between the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior inferior iliac spine, which is exposed during surgery, was selected as the clamping base plate. The acetabular screw guide plate was then generated using Boolean operations (see Figs. 1(c) and (d)). The final guide plate was printed using Magics operational model slicing software, utilizing medical-grade photosensitive resin as the printing material. A preoperative surgical simulation was performed to ensure accuracy (see Fig. 1(e)). Before intraoperative use, all template components underwent cryogenic plasma sterilization to ensure aseptic conditions. The guide plate design, including virtual channel planning, was done in 1.5 ± 0.3 h, while stereolithography printing was completed in 4.2 ± 0.6 h. The average time from CT completion to guide plate readiness was 6 h, meeting the emergency surgery time constraints. Although the guide plate group required an additional 6 h for template production, the optimized preoperative workflows, such as concurrent template fabrication during patient stabilization, resulted in comparable surgical timing between the groups, showing no significant delays. The material cost for each 3D-printed guide plate using medical-grade photosensitive resin was approximately $28 USD. Software licensing fees (Mimics/3-Matic) were amortized to $14 USD per case. The technical design and printing time (2 h at $56 USD labor cost) brought the total per-guide cost to $98 USD.

Conventional group

Minimally invasive percutaneous fixation of the anterior pelvic ring was routinely performed. Preoperative imaging included CT scans and X-rays, with pelvic inlet and outlet views obtained. The acquired imaging data were processed in the workstation, and reference plane images were selected for surgical planning. Fracture characteristics and surrounding soft tissue conditions were evaluated in multiple dimensions, and the surgical plan was designed. The intestines were routinely cleaned before the procedure to reduce the impact of feces and intestinal gas on intraoperative fluoroscopy. Upon entering the operating room, patients underwent general anesthesia and were placed in the supine position. A 2–3 cm longitudinal incision was made with the anterior superior iliac spine as the central point. The sartorius muscle and tensor fasciae latae were bluntly dissected to expose the anterior superior iliac spine. Using a periosteal elevator, the inner and outer plates of the iliac bone were carefully separated. Pedicle screw placement was performed with an open awl.

The acetabular screw entry point was positioned near the insertion site of the rectus femoris muscle. Based on the surgeon’s experience, the screw entry point was identified at the outer aspect of the anterior iliac spine on both sides, with the anterior inferior iliac spine used as a reference under teardrop view fluoroscopy [6]. Under obturator oblique and pelvic outlet views, C-arm fluoroscopy guided the insertion of the guidewire. After confirming proper placement, a screw of appropriate length and diameter was inserted [7].

Scherer et al.. suggested that maintaining a rod-bone distance of 20–25 mm and a rod-pubic symphysis distance of < 40 mm helps reduce lateral femoral cutaneous nerve irritation [8]. However, individual patient body types must be considered when determining the optimal rod-bone distance. Additionally, pedicle screw stability requires a screw length of at least 50∼60 mm within the bone [9]. The contralateral acetabular screw was implanted using the same technique. A rod was inserted through a small incision at the anterior superior iliac spine on one side and advanced through a subcutaneous tunnel in the abdominal “bikini area” to reach the subcutaneous screw. The rod was positioned subcutaneously and superficially on the sartorius muscle, connected to the bilateral screws, manually adjusted for reduction, and secured by tightening the nut.

Guide plate group

The guide plate-assisted technique was implemented based on the conventional group’s approach, utilizing 3D printing technology for precise screw placement.

A skin incision was made at the surface projection of the anterior inferior iliac spine, 0.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. The fat and fascia layers were incised, exposing and protecting the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Blunt dissection was performed between the sartorius muscle and tensor fasciae latae to access the region between the anterior superior and inferior iliac spines. An electric knife was used to clear soft tissue from the bone surface, exposing the bone groove between the anterior superior and inferior iliac spines (Fig. 2(a)).

Fig. 2.

How navigation templates operate in the infix operation mode. (a) reveals the grooves between the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior inferior iliac spine and removes the supracossicular soft tissue. (b) Placing the guide between the grooves and inserting a temporary Kirschner needle to give fixation. (c) Driving a positioning Kirschner needle. (d) Fluoroscopy after removal of the guide plate and temporary Kirschner needle, with the guide needle in the center of the “tear drop position”

The navigation template was securely fixed between the anterior superior and inferior iliac spines, and a 2.5 mm Kirschner wire was inserted to a depth of 2 cm for temporary fixation (Fig. 2(b)). The inner core of the guide plate was inserted, and a 2.0 mm positioning Kirschner wire was advanced along the positioning channel, maintaining a depth of 15–40 mm. Under C-arm fluoroscopy, the wire position was confirmed at the center of the teardrop position in the obturator oblique, pelvic outlet, and teardrop views (Fig. 2(c)).

Once proper positioning was confirmed, a hollow drill was used to remove the positioning guide pin, hollow catheter, and base in sequence. A screw of appropriate length and diameter was then inserted, ensuring that the screw tail remained exposed on the surface of the sartorius muscle.

The contralateral acetabular screw was placed using the same technique. A rod was inserted through a small incision on one side and guided through a subcutaneous tunnel in the abdominal “bikini area” to the subcutaneous screw. The rod was positioned subcutaneously and superficially on the sartorius muscle, connected to the bilateral screws, manually adjusted for reduction, and secured by tightening the nut (Fig. 2(d)).

Postoperative intervention and evaluation criteria

Postoperatively, second-generation cephalosporins were administered for 1–3 days based on the patient’s condition. Enoxaparin sodium (6000 IU/Qd, subcutaneous injection) was initiated on postoperative day 2 for thromboprophylaxis.

Radiographic assessment was performed immediately after surgery, including anteroposterior, inlet, and outlet pelvic X-rays. Early mobilization and functional exercises were encouraged to minimize complications. Patients without significant comorbidities were advised to turn independently the day after surgery, sit up by postoperative day 3, and progressively increase activity.

Patients underwent monthly outpatient follow-ups for the first three months post-surgery. Partial weight-bearing with double crutches was initiated 2–4 weeks postoperatively, followed by single crutch-assisted walking at 4–10 weeks. Full weight-bearing was permitted 10–12 weeks postoperatively. X-ray assessments were conducted at 1, 2, and 3 months to monitor screw positioning and accuracy. Clinical evaluations included assessments of lumbosacral pain, gait patterns, walking distance with assistance, standing tolerance, adaptation to INFIX, and nerve injury. At the final follow-up, functional outcomes were evaluated using Majeed’s scoring system.

Screw placement status

A three-dimensional CT scan was performed on postoperative day 2 to assess screw placement accuracy. Screw positioning was categorized into four grades: grade 0 (no cortical bone penetration); grade 1 (cortical bone penetration of less than 2 mm); grade 2 (cortical bone penetration between 2 and 4 mm); grade 3 (cortical bone penetration exceeding 4 mm).

Clinical indicators

Surgical parameters, including operative time, number of intraoperative fluoroscopic evaluations, intraoperative blood loss, and incision length, were recorded and compared between the two groups.

Fracture reduction status

Postoperative fracture reduction was evaluated using the Matta criteria and classified into three levels: excellent (85 ~ 100 points), good (70 ~ 84 points), medium (55 ~ 69 points), and poor (below 55 points) [10].

Complications

The incidence of postoperative complications, including femoral lateral cutaneous nerve dysfunction, infection, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and screw loosening or withdrawal, was compared between the groups.

Functional outcomes

Clinical function was assessed at the final follow-up [11] using the Majeed scoring system, evaluating pain, work capacity, sitting, standing, and sexual activity. Functional outcomes were classified as follows: excellent (≥ 85 points), fair (55–69 points), and poor (< 55 points).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 software. Normal distribution tests were conducted on the measurement data to determine the appropriate statistical approach. Data following a normal distribution were expressed as “mean ± standard deviation,” and inter-group comparisons were conducted using an independent sample t-test. For data that did not meet the normal distribution criteria, values were presented as “median (lower quartile, upper quartile),” and comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Count data were expressed as “case (%),” with inter-group comparisons performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A significance level of α = 0.05 was set, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Reference conclusion

The results presented in Table 2 indicate that surgery time, the number of intraoperative fluoroscopies, and the number of guide needle trajectory adjustments were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05), whereas intraoperative bleeding volume showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). The guide plate group demonstrated shorter surgery duration, fewer fluoroscopic assessments, and fewer guide needle trajectory adjustments than the conventional group (P < 0.05). In traditional fluoroscopic pelvic fracture fixation, repeated fluoroscopic imaging of the inlet, outlet, and teardrop positions was required to adjust the needle entry point and screw trajectory, leading to prolonged surgery time and increased radiation exposure for both patients and surgical staff [12]. The use of a preoperatively designed guide plate simplified the surgical process, reducing the number of fluoroscopies and trajectory adjustments while enabling precise screw placement, ultimately shortening surgery time and minimizing radiation exposure.

Table 2.

Comparison of surgery time, bleeding volume, number of fluoroscopies, and number of guide needle trajectory adjustments between patients in the guide plate group and the conventional group

| Variable | Guide plate group (n = 23) |

Conventional group (n = 28) |

t/Z | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery time (min) | 46.30 ± 8.14 | 51.43 ± 8.42 | -2.19 | 0.033 |

| Intraoperative bleeding volume (mL) | 14.00 ± 2.68 | 15.00 ± 2.61 | -1.35 | 0.185 |

| Number of intraoperative fluoroscopies | 6.00 (5.50, 8.50) | 12.50 (8.75, 16.25) | -3.97 | < 0.001 |

| Number of guide needle trajectory adjustments during surgery | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 4.00 (2.00, 6.00) | -4.10 | < 0.001 |

Reference conclusion

The results in Table 3 show that the differences in the Matta scores of the two groups were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The guide plate group demonstrated a higher percentage of excellent Matta scores (78.26%) compared to the conventional group (50.00%). Similarly, the percentage of good Matta scores was also higher in the guide plate group (17.39%) than in the conventional group (14.29%). These findings suggest that the use of preoperative planning with individualized navigation templates in INFIX surgery enhances the accuracy of pelvic reduction, leading to improved surgical outcomes.

Table 3.

Comparison of Matta scores for postoperative fracture reduction between the guide plate group and the conventional group

| Group | n | Matta score/case for fracture reduction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fair | Good | Excellent | ||

| Guide plate group | 23 | 1 (4.35) | 4 (17.39) | 18 (78.26) |

| Conventional group | 28 | 10 (35.71) | 4 (14.29) | 14 (50.00) |

| Z | - | |||

| P | 0.021 | |||

Note: - Indicates that Fisher’s exact test method is used

Reference conclusion

The results in Table 4 indicate that the differences in Majeed functional scores between the two groups were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The proportion of patients with excellent Majeed functional scores in the guide plate group was 78.26%, notably higher than the 39.29% observed in the conventional group, suggesting superior clinical functional outcomes in the guide plate group. However, there was no statistically significant difference in postoperative complications between the two groups (P > 0.05). This finding aligns with a study case by Arpad Solyom et al. [13] on the treatment of complex pelvic fractures using three-dimensional design and a review by Ronald Man Yeung Wong et al. [14], both of which concluded that 3D printing does not increase the risk of complications. Despite this, the placement of the guide plate between the anterior superior and inferior iliac spines can stretch the femoral lateral cutaneous nerve, leading to postoperative femoral lateral cutaneous nerve paralysis in some patients. Therefore, it is recommended that the femoral lateral cutaneous nerve be exposed and protected when using the guide plate. Among the three patients in the guide plate group who experienced symptoms of femoral lateral cutaneous nerve involvement, two fully recovered after the removal of internal fixation [15]. Some studies have reported that patients with similar symptoms experienced immediate relief following implant removal [16].

Table 4.

Comparison of postoperative complications and postoperative Majeed functional scores between the guide plate group and the conventional group

| Group | n | Majeed functional rating | Complications/case | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fair | Good | Excellent | None | Symptoms of femoral lateral cutaneous nerve | ||

| Guide plate group | 23 | 0 (0.00) | 5 (21.74) | 18 (78.26) | 20 (86.96) | 3 (13.04) |

| Conventional group | 28 | 2 (7.14) | 15 (53.57) | 11 (39.29) | 28 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Z/χ² | - | 1.88 | ||||

| P | 0.013 | 0.170 | ||||

Note: - Indicates that Fisher’s exact test method is used

Discussion

Using a personalized 3D-printed navigation template in the INFIX procedure offers multiple advantages, including reduced surgical complexity, shorter operation time, decreased blood loss, reduced fluoroscopy duration, improved accuracy, enhanced functional outcomes, and better pain management. Literature supports the practicality [17] of 3D-printed physical models, which, when combined with traditional imaging techniques, provide surgeons with a more comprehensive understanding of complex fractures compared to relying solely on 2D and 3D images. High-quality 3D imaging enhances fracture assessment, improving surgical planning and execution. A study by Öztürk et al. employed 3D imaging software to simulate radiological screw placement procedures [18]. They demonstrated that the double-column fixation corridor constituted a universally valid and stable osseous fixation pathway. Using the 3D imaging visualization guidance, Jonas Roos [19] implemented a robot-assisted minimally invasive acetabular anterior plate fixation, achieving excellent therapeutic outcomes.

3D printing has rapidly become a transformative force in orthopedic surgery, enabling individualized customization and highly accurate implant placement. Studies by Zhu Yahui et al. indicate that 3D printing models can compensate for the limited experience of mid- and junior-level physicians [20], thereby reducing the surgery duration, intraoperative bleeding, and fluoroscopy requirements. Additionally, 3D printing significantly shortens the learning curve for less experienced surgeons and enhances medical diagnosis and treatment capabilities. In total hip replacement surgery, customized 3D-printed acetabular prostheses improve surgical accuracy, efficiency [21], and the selection of implantation sites for pelvic bone cement-filled metastatic areas [22].

The 3D surgical guide plate effectively translates digital surgical plans into precise intraoperative execution, making it particularly beneficial for procedures with a low tolerance for error. In the current study, pre-surgical rehearsals were conducted on 3D-printed models before live procedures. This enabled intraoperative scenario analysis and facilitated research applications. For instance, Guangyao Liu [23] performed trial runs on 3D-printed pelvic models prior to biomechanical testing of LC-II screw-plate fixation for C1.1 posterior pelvic ring fractures. Besides improving accuracy, these templates minimize radiation exposure and reduce procedural time. The guide plate designed in this study demonstrated high accuracy and can be applied in emergency settings to stabilize pelvic fractures before patient transfer to specialized hospitals. Moreover, it is viable in situations where fluoroscopic beds or fluoroscopy equipment are unavailable. Furthermore, 3D-printed guide plates have been [24] particularly beneficial for novice surgeons, facilitating procedures traditionally performed only by experienced professionals. These templates also enhance precision in cases involving anatomical variations or suboptimal fluoroscopic conditions. This aligns with the findings by Zhigang Qu et al.., who highlighted the advantages of individualized 3D printing.

Zhengjie Wu’s study on intelligent robotic-assisted fracture reduction systems demonstrated that ensuring the design of virtually precise trajectories in the preoperative 3D CT images could serve as the prerequisite for employing 3D-printed navigation templates [25]. Surgeons should exercise caution when utilizing 3D-printed navigation templates for simulation surgery and individualized cutting [26], as CT image reconstruction does not fully capture the thickness of the periosteum and surrounding soft tissues. This limitation may result in improper placement of navigation templates, ultimately affecting surgical accuracy. Additionally, the stability of the guide plate relative to the bone surface plays a critical role in maintaining precision. Theoretically, a larger contact area between the guide plate and the bone enhances positioning accuracy. However, visibility may be obstructed in cases where the surgical exposure area is limited, leading to positioning errors [27]. Therefore, expanding the exposed areas in conventional INFIX surgery is essential to ensure full contact between all support points and the guide plate [28]. To optimize the surface of the navigation template, it has been suggested that soft tissue be removed from the bone surface. Zhang et al. [29] conducted a cadaveric study in which 158 screws were placed with an accuracy of 98.1% after soft tissue removal. To improve precision in this study, the soft tissues on the bone groove between the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior inferior iliac spine were completely peeled off. However, excessive tissue removal may increase the risk of bleeding and infection. Despite this, the advantages of the guide plate design allow the navigation template to be placed even within a conventional INFIX incision length, reducing the need for extensive dissection.

Cost-benefit analysis

Despite the added guide plate cost ($98 USD), the technique significantly reduced operative time (mean 46.3 vs. 51.4 min) and fluoroscopy frequency (median 6.0 vs. 12.5 exposures). At the institutional operational costs ($7 USD/min for OR time and $28 USD/fluoroscopic exposure), the net savings per case reached $119.7 USD. In resource-limited settings, the complication-reduction potential of this technology confers additional clinical-economic value.

In summary, the individualized 3D-printed navigation template significantly reduces the complexity of INFIX surgery, minimizes intraoperative and postoperative complications, and enhances clinical outcomes. The procedure can be safely performed in resource-limited medical facilities, making it feasible for junior surgeons with limited pelvic anatomy experience. Additionally, the technique does not require specialized equipment such as transparent carbon-fiber operating tables or fluoroscopic guidance, promoting its adoption in grassroots hospitals and among less experienced surgeons.

Acknowledgements

Doudou Jing, Lingyuan Zeng, Jiachen Li.

Author contributions

Corresponding author Li Shuwei: Research supervision, funding acquisition, final manuscript review.First author Wu Kaidong: Research design, data collection and analysis, initial draft writing of the paper.Second author Bai Xiaoyu: Clinical data collection, surgical implementation and result evaluation.Third author Li Shuwei: 3D model construction and surgical guide board manufacturing, experimental verification.

Data availability

The data are provided in the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chen W, et al. National incidence of traumatic fractures in china: a retrospective survey of 512 187 individuals. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5:e807–17. 10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Xujin F, Shiyuan X. Mechanical stability of different internal fixations for complex pelvic fractures by finite element analysis [J]. Chin J Tissue Eng Res. 2018;22(27):4354–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meinberg EG, Agel J, Roberts CS, Karam MD, Kellam JF. Fracture and Dislocation Classification Compendium-2018. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32 Suppl 1:S1-S170. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001063. PMID: 29256945. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ansari M, Kawedia A, Chaudhari HH, Teke YR. Functional outcome of internal fixation (INFIX) in anterior pelvic ring fractures. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36134. 10.7759/cureus.36134. PMID: 37065289; PMCID: PMC10101190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LU Sheng, XIN Xin, HUANG Wenhua, LI Yanbing. Progress in clinical application of 3D printed navigational template in orthopedic surgery. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2020;40(8):1220–1224. 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.08.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang MY. Percutaneous Iliac screws for minimally invasive spinal deformity surgery. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;2012:173685. 10.1155/2012/173685. Epub 2012 Jul 29. PMID: 22900162; PMCID: PMC3414079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterhoff G, Aichner EV, Scherer J, Simmen HP, Werner CML, Feigl GC. Anterior subcutaneous internal fixation of the pelvis - what rod-to-bone distance is anatomically optimal? Injury. 2017;48(10):2162–8. 10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.047. Epub 2017 Aug 25. PMID: 28859843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scherer J, Tiziani S, Sprengel K, Pape HC, Osterhoff G. Subcutaneous internal anterior fixation of pelvis fractures-which configuration of the infix is clinically optimal?-a retrospective study. Int Orthop. 2019;43(9):2161–6. 10.1007/s00264-018-4110-9. Epub 2018 Sep 8. PMID: 30196442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith A, Malek IA, Lewis J, Mohanty K. Vascular occlusion following application of subcutaneous anterior pelvic fixation (INFIX) technique. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25(1):2309499016684994. 10.1177/2309499016684994. PMID: 28166706. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Matta JM, Saucedo T. Internal fixation of pelvic ring fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(242):83-97. PMID: 2706863. [PubMed]

- 11.Majeed SA. External fixation of the injured pelvis. The functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72(4):612-4. 10.1302/0301-620X.72B4.2380212. PMID: 2380212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Routt ML Jr, Kregor PJ, Simonian PT, Mayo KA. Early results of percutaneous iliosacral screws placed with the patient in the supine position. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):207-14. 10.1097/00005131-199506000-00005. PMID: 7623172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Solyom A, Moldovan F, Moldovan L, Strnad G, Fodor P. Clinical workflow algorithm for preoperative planning, reduction and stabilization of complex acetabular fractures with the support of Three-Dimensional technologies. J Clin Med. 2024;13(13):3891. 10.3390/jcm13133891. PMID: 38999455; PMCID: PMC11242480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong RMY, Wong PY, Liu C, Chung YL, Wong KC, Tso CY, Chow SK, Cheung WH, Yung PS, Chui CS, Law SW. 3D printing in orthopaedic surgery: a scoping review of randomized controlled trials. Bone Joint Res. 2021;10(12):807–19. 10.1302/2046-3758.1012.BJR-2021-0288.R2. PMID: 34923849; PMCID: PMC8696518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaidya R, Martin AJ, Roth M, Tonnos F, Oliphant B, Carlson J. Midterm radiographic and functional outcomes of the anterior subcutaneous internal pelvic fixator (INFIX) for pelvic ring injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(5):252–9. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000781. PMID: 28079731; PMCID: PMC5402711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang C, Alabdulrahman H. Pape HC complications after percutaneous internal fixator for anterior pelvic ring injuries. Int Orthop. 2017;41(9):1785–90. 10.1007/s00264-017-3415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keil H, Aytac S, Grützner PA, Franke J. Intraoperative imaging in pelvic surgery. Z Orthop Unfall. 2019;157(4):367–77. 10.1055/a-0732-5986. English, German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Öztürk V, Çelik M, Tıngır M, Özönder F, Kural C, Bilgili MG. Is the both column fixation corridor a universally valid and consistent fixation pathway in pelvic and acetabular surgery? J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):590. 10.1186/s13018-025-06008-3. PMID: 40524194; PMCID: PMC12168274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabir K, von Rundstedt FC, Roos J, Gathen M. Robotic-assisted plate fixation of the anterior acetabulum - clinical description of a new technique. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19(1):253. 10.1186/s13018-024-04731-x. PMID: 38644485; PMCID: PMC11034051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Ya-hui, Gang FBing-jinY, Chao W et al. Treatment outcomes of three-dimensional printing technology for foot and ankle fractures by junior versus senior physicians, 2018,19:3061–6. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.0306

- 21.Zhang H, Ma XD, Li BW, Zhao JN, Wang JQ, Zhou JS. [The accuracy and efficiency of design and development of 3D printed integral anatomical acetabular prosthesis in total hip arthroplasty for Crowe type II and III developmental dysplasia of the hip]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2024;104(41):3815-3821. Chinese. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20240306-00501. PMID: 39497400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Sieffert C, Meylheuc L, Bayle B, Garnon J. Design and 3D printing of pelvis phantoms for cementoplasty. Med Phys. 2024 Dec 17. 10.1002/mp.1756. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39688399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Liu Y, Wang X, Tian B, Yao H, Liu G. Experimental study of fractures of the posterior pelvic ring C1.1 using LC-II screws and internal fixation by plate. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19(1):761. 10.1186/s13018-024-05229-2. PMID: 39543607; PMCID: PMC11566199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Yi, Zhang Lifeng, Wang Bin, et al. Research on novel auxiliary placement techniques for sacroiliac screws[J]. Chin J Orthop Trauma. 2020;22(6):507–11. 10.3760/cma.j.cn115530-20190910-00315. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, Dai Y, Zeng Y. Intelligent robot-assisted fracture reduction system for the treatment of unstable pelvic fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19(1):271. 10.1186/s13018-024-04761-5. PMID: 38689343; PMCID: PMC11059586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong RMY, Wong PY, Liu C, Chung YL, Wong KC, Tso CY, Chow SK, Cheung WH, Yung PS, Chui CS, Law SW. 3D printing in orthopaedic surgery: a scoping review of randomized controlled trials. Bone Joint Res. 2021;10(12):807–19. 10.1302/2046-3758.1012.BJR-2021-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou K, Tao X, Pan F, Luo C, Yang H. A novel Patient-Specific Three-Dimensional Printing Template Based on External Fixation for Pelvic Screw Insertion. J Invest Surg. 2022;35(2):459-466. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2020.1863528. Epub 2020 Dec 30. PMID: 33377805.Feb;35(2):459-466. 10.1080/08941939.2020.1863528 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Gauci MO. Patient-specific guides in orthopedic surgery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(1S):103154. 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.103154. Epub 2021 Nov 24. PMID: 34838754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang G, Yu Z, Chen X, Chen X, Wu C, Lin Y, Huang W, Lin H. Accurate placement of cervical pedicle screws using 3D-printed navigational templates: An improved technique with continuous image registration. Orthopade. 2018;47(5):428-436. English. 10.1007/s00132-017-3515-2. PMID: 29387914. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are provided in the manuscript or supplementary information files.