Abstract

Introduction

Osteomas are benign bone tumors most commonly found in the external auditory canal, often mistaken for exostoses. While typically asymptomatic, larger osteomas can cause hearing loss, tinnitus, or canal obstruction.

Case presentation

A 20-year-old Syrian male presented with progressive right-sided hearing loss and difficulty inserting ear-cleaning tools, persisting since age 13 years. Previous conservative management with canal dilation was unsuccessful. Examination revealed partial occlusion of the external auditory canal, and otoscopy was not possible owing to the stenosis. Axial and three-dimensional computed tomography scans identified a bony bridge connecting the mastoid and zygomatic processes, obstructing the canal. Audiometry confirmed conductive hearing loss (40–50 dB air–bone gap). The patient underwent postauricular excision, bony drilling, and canal reconstruction. Postoperatively, the air–bone gap resolved, and canal patency was restored. Histopathology confirmed a benign osteoma.

Conclusion

Despite being benign, this condition warrants more research to address knowledge gaps and improve diagnosis, especially in underserved areas. Better understanding and awareness could significantly enhance patient management and quality of life.

Keywords: Case report, Osteoma, External auditory canal benign tumors, Mastoid, External auditory canal stenosis

Introduction

Osteomas are benign, slow-growing bone tumors that commonly affect areas such as the external auditory canal (EAC), the mastoid cortex, facial bones, and the mandible [1]. They often remain stable and undetected for long periods of time [2]. Osteomas are generally mistaken for exostoses and grouped together. However, Graham [3], in 1979, provided a clear distinction between these two lesions on the basis of their histopathological characteristics. Symptoms are rare and may involve vertigo, pain, hearing loss, and tinnitus. Diagnosis is based on clinical history, examination, radiographic imaging studies, and histopathology [4]. Surgical removal is the primary treatment for EAC osteomas, although asymptomatic patients may be managed through careful monitoring without immediate intervention [5]. We present a case of a 20-year-old Syrian male who was experiencing hearing loss in the right ear along with a narrowing of the external auditory canal. This narrowing was not visibly noticeable from the outside, but the patient complained of being unable to insert ear-cleaning tools (such as cotton swabs) into the affected ear. The patient had been visiting doctors since the age of 13 years, but no accurate or appropriate diagnosis was provided for his condition. This case report is presented in accordance with the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) 2023 criteria [6].

Case presentation

A 20-year-old Syrian male presented to the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) clinic with right-sided hearing loss and a sensation of ear canal obstruction, reporting an inability to insert ear-cleaning tools, unlike the left ear. The patient had consulted several specialists since the age of 13 years and had undergone conservative treatment involving canal dilation using ear plugs; however, no improvement was achieved.

The canal narrowing remained stable over time (neither worsened nor improved). However, the hearing loss had progressively increased owing to wax impaction in the canal, rather than lesion progression.

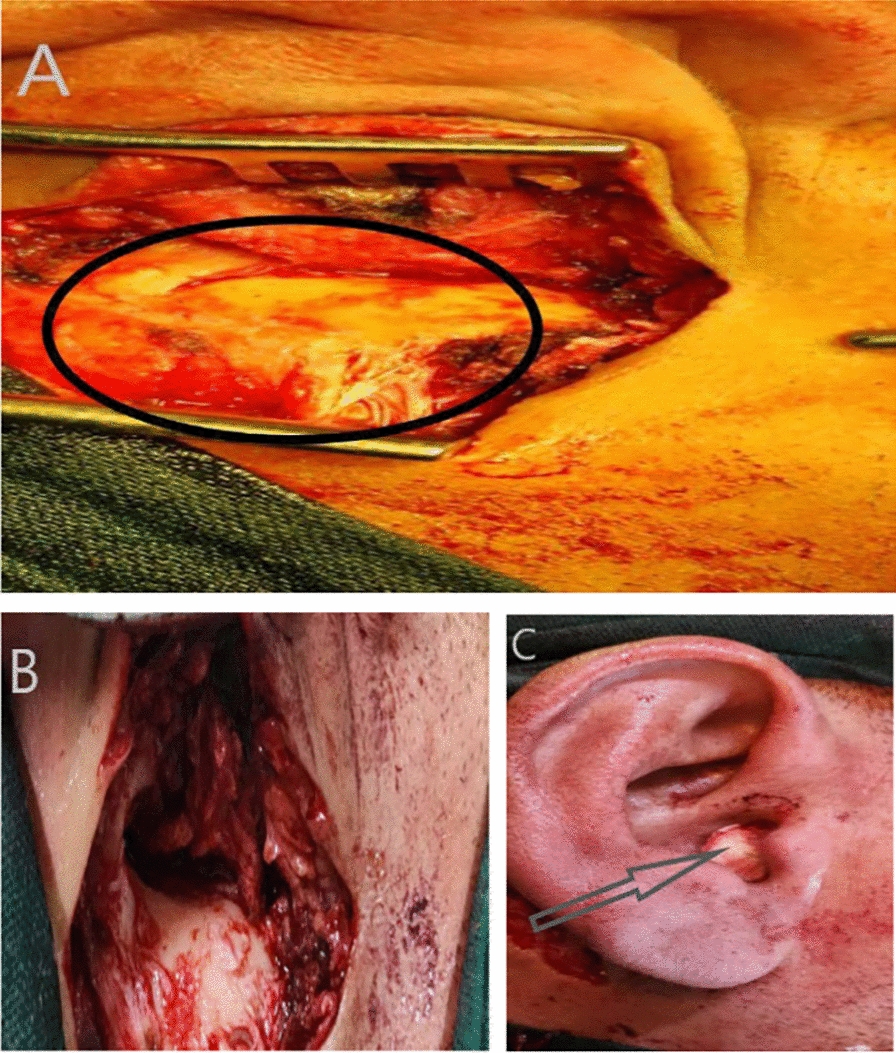

On clinical examination, the auricle appeared normal, but there was partial obstruction at the entrance of the external auditory canal (Fig. 1). An attempt was made to perform otoscopy on the right ear using a 3 mm lens, but it was unsuccessful. In contrast, the left ear showed no pathological findings, either visually or upon otoscopy.

Fig. 1.

The red circle indicates canal stenosis, while the blue triangle marks the skin stretched over the bony prominence

Imaging studies:

-Axial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed canal occlusion by a bony segment (Fig. 2A).

-A three-dimensional (3D) CT scan showed a bony bridge extending from the mastoid process posteriorly to the zygomatic process anteriorly (Fig. 2B).

Additional tests:

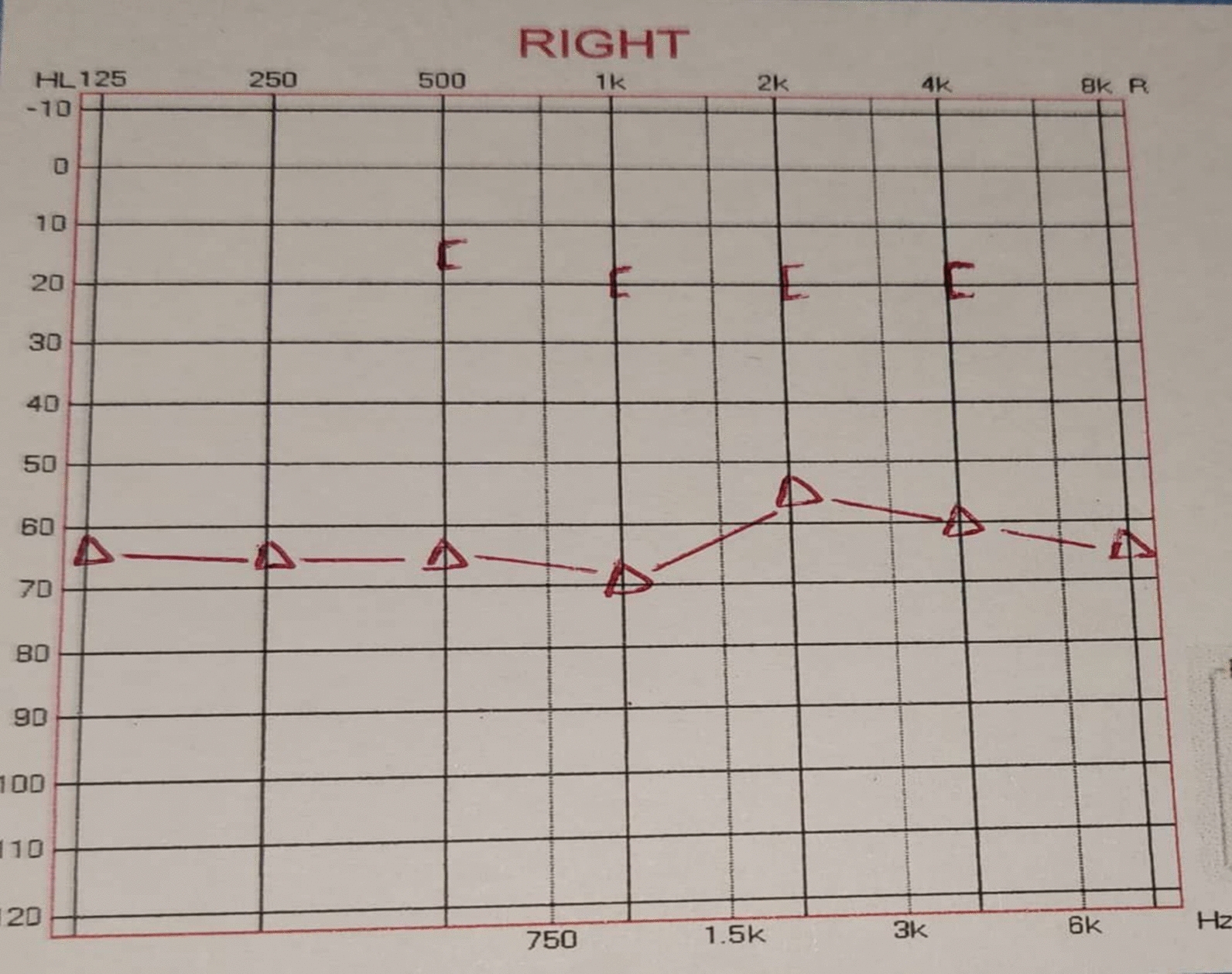

-Pure-tone audiometry demonstrated conductive hearing loss with an air–bone gap of 40–50 dB (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

A Axial computed tomography scan of the right temporal bone revealing bony obliteration of the external auditory canal lumen. B Three-dimensional computed tomography scan of the right temporal bone showing a bony bridge extending from the mastoid process to the zygomatic process

Fig. 3.

Right ear pure tone audiometry showing conductive hearing loss with about 50 dB air–bone gap

After explaining the condition to the patient and obtaining consent for surgery, a postauricular incision was made, followed by dissection to the mastoid cortex. The overlying bony segment connecting the posterior canal wall (mastoid) to the anterior canal wall (zygomatic process) was identified (Fig. 4A). We drilled the excess bone with a burr and reconstructed the auditory canal (Fig. 4B). A Merocel pack was placed in the ear canal immediately after bone removal (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

A The black circle marks the bony stenosis of the external auditory canal. B Postoperative view of the external auditory canal following drilling of the osteomas. C A Merocel pack (gray arrow) was placed in the ear canal immediately after surgical removal of bony segment

Postoperative care included:

-Sterile gauze dressing (changed every 48 hours for 10 days)

-Antibiotic coverage: Augmentin 1 g tablet every 12 hours for 7 days

-Analgesics: acetaminophen as needed

- On day 10: suture removal and Merocel pack removal

Postoperative evaluation and periodic follow-up:

The pathology report showed well-organized, mature lamellar bone surrounded by dense fibrocollagenous stroma, with no evidence of cellular atypia or osteoid proliferation. These morphological features are diagnostic of conventional osteoma.

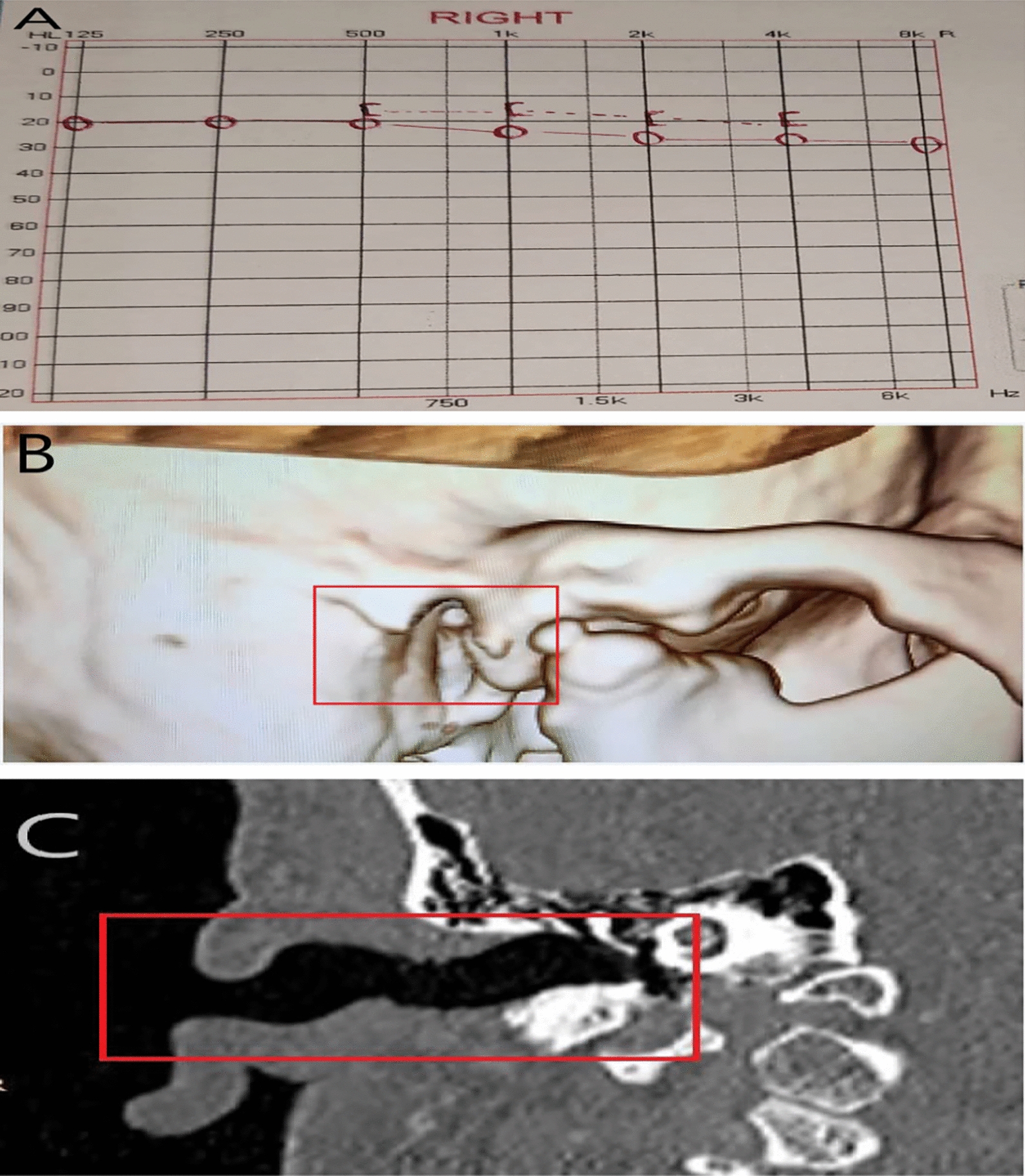

During follow-up, after 6 months, the pure-tone audiometry revealed the absence of the air–bone gap, accompanied by clinical improvement in the patient’s conductive hearing loss, and the imaging study (coronal CT scan, and 3D CT scan) of the right temporal bone demonstrated complete removal of the bony mass. The external auditory canal appeared anatomically preserved with no signs of recurrence. As of this manuscript’s submission, no radiologic signs of recurrence or complications were noted during the periodic follow-up (every year) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A Right ear pure-tone audiometry showing the absence of the air–bone gap, which was about 50 dB before surgery. B Postoperative three-dimensional computed tomography scan showing the absence of the bony bridge. C Postoperative coronal computed tomography scan showing how the auditory canal has returned to normal after removing the cause of the stenosis

Discussion

Osteomas are benign bony growths that most commonly occur in the external auditory canal (EAC), mastoid cortex, facial bones, and mandible [1]. Despite their benign nature, osteomas in the EAC may produce significant clinical symptoms due to canal blockage and space-occupying effects [7–9]. Osteomas have traditionally been compared and contrasted with exostoses of the external auditory canal (EAC). Both osteomas and exostoses are typically benign and are often discovered incidentally as they usually grow slowly and remain stable and undetected for several years. Among the two, exostosis is far more common, with an incidence rate of 0.6%, and it occurs more frequently in middle-aged men. While chronic irritants, such as exposure to cold water and repeated episodes of otitis externa, have a direct correlation with the development of exostosis, the exact cause of osteomas in the EAC remains unidentified [3, 4]. Although some documented cases link osteomas of the external auditory canal (EAC) to frequent cold-water exposure (for example, in surfers and swimmers), most studies lack conclusive evidence. Current theories propose that factors such as trauma, chronic inflammation, hormonal influences, infections, developmental abnormalities, and genetic predisposition could contribute to the formation of EAC osteomas [1–3]. In the case presented here, the lesion was unilateral, unlike exostoses (surfer’s ear), which are typically bilateral. This, along with the patient’s lifestyle and the absence of any habits or water sources for swimming, negates the diagnosis of exostoses [2]. However, on the basis of the characteristics of the bony bridge and the clinical history that began in his childhood, without progression or increase in size, this suggests a congenital condition. Unfortunately, we cannot confirm this owing to the absence of the patient’s past medical records or imaging from his childhood. Nevertheless, this possibility remains valid on the basis of the patient’s clinical history. Epidemiological studies on EAC osteomas remain limited, primarily because of their rarity. Available research indicates that this benign tumor can occur across various age groups, with cases reported as early as the second decade of life. However, data on gender predominance are inconsistent and inconclusive [5, 7]. Both osteomas and exostoses may present with comparable symptoms, such as vertigo, episodic tinnitus, sensorineural hearing impairment, trigeminal nerve pain, and localized discomfort [8, 9]. On a computed tomography (CT) scan, an osteoma is characterized as a solitary, unilateral, pedunculated, hyperdense mass that originates from the tympanosquamous or tympanomastoid suture line and extends into the internal auditory canal (IAC) space without causing significant canal narrowing, unlike the present case, which reached the zygomatic process, causing partial canal obstruction [2, 3]. Similar to osteomas, exostoses appear as hyperdense structures on CT scans extending into the IAC space. However, they characteristically manifest as numerous, symmetrical lesions with well-defined borders and broad implantation sites, lacking deeper penetration [2, 10]. Graham [3], in his 1979 publication, attempted to establish histological differentiation between these two lesions, identifying the existence or lack of fibrovascular channels as a key diagnostic criterion separating EAC osteomas from exostoses. His work suggested that these vascular features were pathognomonic for osteomas. Contrasting these findings, Fenton et al. [10], in subsequent research, utilizing a larger sample size, demonstrated limitations to this histological approach. Their analysis revealed that fibrovascular channels were present in numerous exostosis cases, indicating that basic histopathological examination may not reliably differentiate these osseous growths. Given the typically slow-growing behavior of external auditory canal osteomas, most patients remain asymptomatic, with these lesions frequently being discovered incidentally during unrelated examinations. Conservative monitoring represents an appropriate management strategy, reserving surgical intervention for symptomatic cases or when potential complications are expected. When required, excision can generally be performed safely via a transmeatal approach [5, 7]. However, the diagnostic delay in this case, despite clear symptoms, was attributed to several interrelated factors:

1-Geographic barriers: The patient resides in a remote area lacking specialized medical centers.

2-Healthcare limitations: His visits are restricted to local clinics with poor diagnostic capabilities and insufficient medical expertise.

3-Behavioral factors: The patient’s neglect of medical follow-up due to his perception that the symptoms were non-life-threatening.

Conclusion

Although the disease itself is not life-threatening, there remains an urgent need for further research to better understand its underlying mechanisms. Such knowledge is crucial for developing effective treatments and preventive measures, particularly given the significant knowledge gaps that still exist. Compounding this issue is the fact that many specialists, especially in rural areas, may lack sufficient awareness of the disease or clinical experience in managing it. Addressing these challenges would substantially improve healthcare standards and enhance the quality of life for affected individuals.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patient for their full cooperation, which was essential for the successful completion of this manuscript. We also extend our deepest gratitude to the medical team at Yusuf Al-Azma Hospital for their exceptional collaboration and for providing all necessary facilities to make this work possible.

Author contributions

Dr. Bilal Hasan: provided medical treatment, wrote and supervised the scientific aspects of the manuscript, and edited the text for grammar and spelling. Dr. Zulfiqar Hamdan: wrote and revised the manuscript, supervised the academic and scientific aspects of the manuscript, and edited the text for grammar and spelling. Dr. Lina Mohamad: participated in writing. Dr. Nagham Salem: participated in writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the publication of this article.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was needed.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liétin B, Bascoul A, Gabrillargues J, Crestani S, Avan P, Mom T, et al. Osteoma of the internal auditory canal. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2010;127(1):15–9. 10.1016/j.anorl.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baik FM, Nguyen L, Doherty JK, Harris JP, Mafee MF, Nguyen QT. Comparative case series of exostoses and osteomas of the internal auditory canal. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(4):255–60. 10.1177/000348941112000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham MD. Osteomas and exostoses of the external auditory canal. A clinical, histopathologic and scanning electron microscopic study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88(4 Pt 1):566–72. 10.1177/000348947908800422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbone PN, Nelson BL. External auditory osteoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(2):244–6. 10.1007/s12105-011-0314-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheehy JL. Diffuse exostoses and osteomata of the external auditory canal: a report of 100 operations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1982;90(3 Pt 1):337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Maria N, Kerwan A, Franchi T, Agha RA. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2023;109(5):1136–40. 10.1097/js9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orita Y, Nishizaki K, Fukushima K, Akagi H, Ogawa T, Masuda Y, et al. Osteoma with cholesteatoma in the external auditory canal. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;43(3):289–93. 10.1016/s0165-5876(98)00022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerganov VM, Samii A, Paterno V, Stan AC, Samii M. Bilateral osteomas arising from the internal auditory canal: case report. Neurosurgery. 2008. 10.1227/01.neu.0000316023.81786.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dosemane D, Adiga D, Khadilkar MN, Chandy N. External auditory canal osteoma with coexisting canal wall cholesteatoma: a case report and review of literature. J Med Case Rep. 2024;18(1):581. 10.1186/s13256-024-04846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenton JE, Turner J, Fagan PA. A histopathologic review of temporal bone exostoses and osteomata. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(5 Pt 1):624–8. 10.1097/00005537-199605000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.