Abstract

Background

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are responsible for substantial illness and death worldwide. Helminthic infections among school-aged children pose a serious public health challenge due to their detrimental effects on health and development.

Methods

A wide-ranging search conducted across five databases, including Scopus, EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to retrieve papers published between 1998 and 2024. To evaluate the combined prevalence, a random-effects model with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was applied, and the statistical analysis was performed using meta-analysis packages in R version (3.6.1).

Results

There were 190 eligible studies documented in 42 countries, and 199,988 schoolchildren included in this review. The global prevalence of helminthic parasites was 20.6% (17.2– 24.3%). Among the countries studied, Tanzania and Vietnam showed the highest levels of prevalence at 67.41% and 65.04%, respectively, with Toxocara spp. and Ascaris lumbricoides being the most prevalent helminthic parasites at 10.36% and 9.47%, respectively.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study underscores the pressing public health concern of helminthic infections among schoolchildren, largely driven by inadequate sanitation and poor water quality. Prompt action, such as improving sanitation, expanding school-based deworming programs, and enhancing access to safe water, is crucial to control these infections and enhance overall health outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-23958-9.

Keywords: Intestinal helminths, Soil-transmitted helminths (STHs), Child health, Schoolchildren, Systematic review

Background

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are primarily chronic infections that cause significant illness and death, particularly among the world’s poorest populations. These diseases not only impact health but also contribute to the cycle of poverty [1].

Socioeconomic disadvantage is a well-established and significant factor influencing the spread of these diseases. Factors such as poverty and inadequate sanitation play a key role in facilitating parasite transmission [2]. In terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), the greatest burden of NTDs is still attributed to soil-transmitted helminth (STHs) infections, schistosomiasis, lymphatic filariasis, and dengue fever [3].

Intestinal helminth infections are regarded as highly significant socio-economic and public health concerns globally [4]. Their prevalence is higher in tropical and subtropical zones, notably among populations in developing countries facing poverty and poor sanitary conditions [5]. It is approximated that nearly 300 million people suffer from heavy morbidity of intestinal helminths with annual deaths ranging from 10,000 to 135,000 [5, 6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) statistics, many people worldwide are infected with these infections. Globally, nearly 2 billion people primarily children are infected with common parasitic diseases such as STHs, which include hookworms (Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale), Ascaris lumbricoides, and Trichuris trichiura [7].

Preschoolers and school-aged children, including adolescents, are disproportionately affected by intestinal helminths and schistosomes for reasons that are not yet well understood. These infections can result in stunted growth, weakened physical health, and impaired cognitive function particularly memory and learning which together negatively impact their educational achievement and school participation [8].

Transmission of intestinal parasites commonly occurs via exposure to contaminated feces, ingestion of raw or undercooked meat, contaminated water or soil, or through transdermal penetration [9]. In children, infection commonly occurs through soil-transmitted routes and behaviors such as nail biting. In high-prevalence regions, approximately 870 million children are estimated to be at risk of soil‑transmitted helminth infections globally, according to WHO [10]. A prevalence rate of high intestinal parasite has been reported in children compared to people of other ages. Intestinal helminths infection in children can lead to severe complications such as malabsorption, malnutrition, disorders of growth and development, anemia and retardation, intestinal obstruction, hemorrhagic diarrhea, fever, dehydration, vomiting and nutritional complications such as iron deficiency anemia. Up to date, numerous studies have been conducted on intestinal parasites prevalence in school-aged children in different countries [11].

According to the geographical and health status of the studied area, statistics have been designed in a wide range, indicating helminth infection as a leading cause of health problem in the world. However, differences in the rate of prevalence of helminth parasites may be related to diverse factors such as climate, geography, socio-economic, and cultural factors [12, 13].

Helminth infections in fecal samples are primarily diagnosed using direct smear microscopy, concentration methods, and the Kato-Katz technique for quantifying helminth eggs, including Schistosoma species [14–16]. Today, more accurate DNA-based methods are used to more accurately diagnose infections of this type [10, 14]. Preschool and schoolchildren are particularly vulnerable to helminth infections and associated complications like malnutrition and anemia. Due to their higher exposure to contaminated sources such as soil, growing evidence over recent years highlights the importance of prioritizing infection risk in this population. These findings are critical in creating proper and effective interventions [17–19].

This systematic review and meta-analysis focused on estimating the global prevalence of helminthic parasite in school-age children via synthesizing data across studies in distinct geographic locations. The findings of this review are expected to support evidence-based interventions aimed at reducing the burden of soil-transmitted helminthic infections among school-aged children.

Methods

Search approach

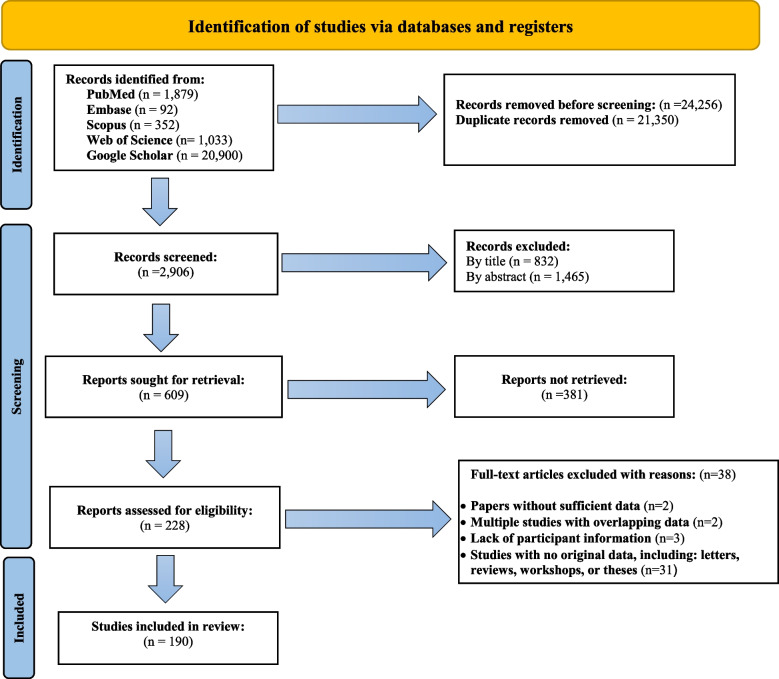

This study adhered to the guidelines established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Fig. 1) [20]. We systematically searched several databases, including Scopus, EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, to collect relevant papers published between 1998 and 2024, applying no date restrictions (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study design process

We used search terms associated with the prevalence, epidemiology, incidence, parasites, parasitic diseases, parasitic infections, helminthiasis, parasitic helminth, helminth parasites, helminthic infections, helminth diseases, pathogenic helminth, intestinal helminth, preschool and/or school-age children, global, and worldwide, using both AND and/or Boolean operators.

Duplicates were removed using EndNote X9 software library and manual verification, followed by manual screening of reference lists to capture relevant studies potentially missed by the database search. After automatic and manual duplicate removal (21,350 duplicates), 2,906 unique records were screened.

Two reviewers (ZG and HS) independently screened titles and abstracts and assessed full-text articles for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (MB). Data extraction and quality assessment were also independently conducted by ZG and HS, with supervision by AVE and MB.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if they were cross-sectional studies documenting helminthic infections in schoolchildren, published as original research in peer-reviewed journals, available in English with both abstracts and full texts accessible, and reporting the total sample size and the number of positive cases.

Studies classified as case series, case reports, letters, editorials, publications lacking original data, review articles, those with inconclusive findings, non-English publications, and studies reporting parasitic helminths from non-human samples were excluded from this analysis.

Microsoft Excel® version 2016 was employed to systematically extract the following data from the included articles: author names, publication year, climate, annual rainfall, average temperature, humidity, gender, age, mean age, educational level, Global Burden of Disease (GBD) regions, WHO region, countries, district/city/province, Human Development Index (HDI), income level, type of samples, diagnostic method, and type of helminth parasites (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the included studies reporting the prevalence of helminth parasites among schoolchildren

| Study No | Author | Study Year | Country | District/City/Province | Diagnostic method | Sample size | Infected | Age of selected population | Mean age | Species of helminths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Khan W et al | 2020 | Pakistan | Dir | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 324 | 266 | 4_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 3 | Chien Wei Liao et al | 2016 | West Africa | Democratic Republic of Sao Tome | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 252 | 108 | 8_9 | 9.8 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 4 | Okyay et al | 2004 | Turkey | Direct smear | 456 | 83 | 7_14 | –– | Enterobius vermicularis | |

| 5 | Habtu Debash et al | 2023 | Ethiopia | Sekota | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 402 | 38 | 6_14 | –– | Hymenolepis nana |

| 6 | Hussein Sharif Siddig et al | 2017 | Sudan | Khartoum | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 120 | 20 | 5_7 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 7 | Ashok et al | 2013 | India | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 208 | 14 | 6_14 | 8.8 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis | |

| 8 | Ranjit Gupta et al | 2020 | Nepal | Saptari | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 285 | 8 | 11_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana |

| 9 | Tamiru Getnet et al | 2020 | Ethiopia | Amber | Direct smear | 384 | 55 | 9_12 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 10 | Khadime sylla et al | 2020 | Senegal | Dakar | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 1603 | 18 | 5_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp. |

| 11 | Chien Wei Liao et al | 2017 | The Republic Of Marshall Island | Democratic Republic of Sao Tome | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 400 | 22 | 6_13 | 9.73 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 12 | Napharanh Nanthavong et al | 2017 | Democratic Republic | Huaphan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 74 | 18 | up to 5 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 13 | Wafaa FA.Ahmad et al | 2011 | Egypt | Tanta | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1520 | 112 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 14 | Talal Alharazi et al | 2020 | Yemen | Taiz | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 385 | 36 | 7_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 15 | Taheri et al | 2011 | Iran | South Khorasan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 2169 | 171 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 16 | Ikram Ullah et al | 2009 | Pakistan | Peshawar | Direct smear | 200 | 140 | 5_10 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 17 | Abdelsafi Gabbad and Mohammed A Elawad | 2014 | Sudan | Khartoum | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 500 | 228 | 5_10 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 18 | Berhanu Feleke | 2016 | Ethiopia | Bahir Dar | Direct smear | 2372 | 1463 | 5_19 | 12.75 | Ascaris lumbricoides |

| 19 | Dires Tegen et al | 2020 | Ethiopia | Dera | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 382 | 211 | 6_21 | –– |

Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 20 | Baba Krishna Sharma et al | 2004 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 533 | 485 | 4_19 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 21 | Olawumi Edward et al | 2017 | Malaysia | Tapah | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 508 | 308 | 6_13 | 10.1 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 22 | Afridi et al | 2017 | Pakistan | Skardu | Direct smear | 300 | 95 | up to 5 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana |

| 23 | Ika Puspa Sari et al | 2016 | Indonesia | Jakarta | Direct smear | 157 | 2 | 6_11 | –– | Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 24 | Eman H.Radwan et al | 2019 | Egypt | Damanhur | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 810 | 47 | 6_18 | 11.2 | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 25 | Msab Nou Raldein et al | 2019 | Sudan | Berber | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 100 | 87 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm |

| 26 | LK Khanal et al | 2011 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 142 | 19 | 6_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 27 | Zeynep Gokalp | 2015 | Turkey | Eskisehir | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 132 | 10 | 7_12 | 7.96 | Enterobius vermicularis |

| 28 | Daniel Gebretasdik et al | 2018 | Ethiopia | Harbu | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 400 | 38 | 5_15 | –– | Hymenolepis nana |

| 29 | Ismail et al | 2018 | Egypt | Taifg | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 150 | 18 | 4_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides |

| 30 | Hayatham Mahmoud Ahmad and Gamal Ali Abu-Sheishaa | 2022 | Egypt | Aga | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 726 | 154 | 6_18 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 31 | Ayalew Sisay and Brook Lemma | 2016 | Ethiopia | Bochesa | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 384 | 84 | 7_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 32 | Abuobieda Sirelkhatem et al | 2019 | Sudan | Ombda | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) | 210 | 29 | 6_14 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp. |

| 33 | R Canete et al | 2013 | Cuba | Matanzas | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 107 | 46 | 8_9 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura |

| 34 | Niyizuragero Emile et al | 2013 | South Africa | Rwanda | Direct smear | 109 | 23 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm |

| 35 | R Devera et al | 1998 | Venezuela | Direct smear & Scotch Tape Test | 282 | 53 | –– | –– | Enterobius vermicularis | |

| 36 | Z Astal | 2004 | Palestine | Khan Younis | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 1370 | 209 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura |

| 37 | Vicente Y.Belizurio et al | 2011 | Philippines | Davao del Norte | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 572 | 248 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 38 | Latha Ragunathan et al | 2010 | India | Puducherry | Direct smear & staining | 1172 | 660 | 5_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 39 | Kuang Yao Chen et al | 2018 | Taiwan | Direct smear & Scotch Tape Test | 44,163 | 93 | 4_6 | –– | Enterobius vermicularis | |

| 40 | Abraham Degarege et al | 2013 | Ethiopia | Wonji Shoa Sugar | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 403 | 312 | 4_6 | 3.3 | Ascaris. Lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm |

| 41 | Alexandwe Rosewell et al | 2010 | Nicaragua | kato-katz method | 880 | 238 | 6_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, | |

| 42 | Abolfazl Iranikhah et al | 2017 | Iran | Qom | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 2410 | 119 | 7_14 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 43 | Moradali Fouladvand et al | 2018 | Iran | Bushehr | Direct smear & Scotch Tape Test | 203 | 23 | 7_12 | –– | Enterobius vermicularis |

| 44 | Warunee Ngrenngarmlert et al | 2007 | Thailand | Nakhon Prathom | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1920 | 14 | 7_12 | –– | Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis, Opisthorchis spp. |

| 45 | Huong Thi Le et al | 2007 | Vietnam | Tam Nong | Direct smear | 400 | 368 | 5_8 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura |

| 46 | Mustafa Ulukanligil and Adnan Seyrek | 2003 | Turkey | Sanliurfa | Direct smear & Scotch Tape Test | 1820 | 1759 | 7_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp. |

| 47 | Sarmila Tandukar et al | 2013 | Nepal | Lalitpur | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 1392 | 40 | 5_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 48 | Rostami Masoumeh et al | 2012 | Iran | Golestan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 800 | 31 | 8_12 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 49 | Ayodhia Pitaloka Pasaribu et al | 2019 | Indonesia | Suka | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 468 | 360 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 50 | Jitendra Shrestha et al | 2019 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 508 | 141 | 4_19 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura |

| 51 | Jannatbi Iti | 2018 | India | Bijapur | Direct smear | 58 | 6 | 8_13 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana |

| 52 | Hassan Rezanezhad et al | 2017 | Iran | Jahrom | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 431 | 1 | ––- | –– | Enterobius vermicularis |

| 53 | Kamal Singh Khadka et al | 2013 | Nepal | Pokhara | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 100 | 6 | 3_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 54 | Elahe Atashnafas et al | 2006 | Iran | Damghan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 764 | 70 | 7_12 | –– | Enterobius vermicularis |

| 55 | Z.Astal et al | 2004 | Palestine | Khan Younis | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 1370 | 496 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 56 | A.Dudlova et al | 2018 | Slovakia | Direct smear & Scotch Tape Test | 390 | 14 | 2_15 | –– | Enterobius vermicularis | |

| 57 | Tsegaw Fentie et al | 2013 | Ethiopia | Tana | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 520 | 458 | 6_15 | 11.6 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Fasciola spp., Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 58 | D L Lee et al | 1999 | Malaysia | Sarawak | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 264 | 117 | 7_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 59 | David M.Cook et al | 2009 | Guatemala | Palajunoj | Direct smear | 5228 | 1207 | 5_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana |

| 60 | Laukaji Rai et al | 2017 | Nepal | Lokhim | Direct smear | 359 | 31 | 4_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 61 | Manisha Shurma et al | 2020 | Nepal | Bhaktapur | Direct smear | 194 | 4 | 6_14 | –– | Hymenolepis nana |

| 62 | Bijay Kumar Shrestha et al | 2021 | Nepal | Dharan Submetropolitan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 400 | 43 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 63 | Melaku Wale and Solomon Gedefaw | 2022 | Ethiopia | Jaragedo | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 396 | 72 | 7_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 64 | Olufemi MOSES Agbolade et al | 2007 | Nigeria | Ogun State | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1059 | 1006 | 3_18 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 65 | Hossein Mahmoudvand et al | 2020 | Iran | Lorestan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 366 | 36 | 2_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 66 | Nan Linh Njuyen et al | 2012 | Ethiopia | Angolela | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 664 | 75 | 6_19 | –– | Ascaris lombricidas, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 67 | Rosa Elena Mejia Torres et al | 2014 | Honduras | Tegucigalpa | kato-katz method | 2554 | 1493 | 8_11 | –– |

Ascaris Lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura , Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 68 | David Jose Gonzalez et al | 2019 | colombia | Antioquia | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 6045 | 2182 | 7_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 69 | Collins Okoyo et al | 2020 | Kenya | Kenya | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 9801 | 1646 | 5_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm |

| 70 | Rajabu Hussein et al | 2020 | Tanzania | Nyamikoma | kato-katz method | 830 | 752 | –– | –– | Schistosoma spp. |

| 71 | Teshome Bekana et al | 2021 | Ethiopia | Amhara | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 798 | 248 | 6_15 | –– | Fasciola spp., Schistosoma spp. |

| 72 | A Escobedol Andel et al | 2008 | Cuba | Pinar del Río | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 200 | 163 | 5_15 | –– | Ascaris Lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 73 | Nahya Salim et al | 2014 | Tanzania | rural coastal Tanzania | Duplicate Urine filtration & Dipstick & Baerman method & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 1033 | 396 | –– | –– | Ascaris Lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis, Wuchereria bancrofti, |

| 74 | Daniel Getacher Feleke et al | 2022 | Ethiopia | Ambara | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 375 | 95 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius.vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 75 | Fikru Gashaw et al | 2015 | Ethiopia | Maksegnit and Enfranz | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 550 | 352 | 5_17 | –– | Ascaris Lumbricoides, Schistosoma spp. |

| 76 | Angus Hughes et al | 2023 | Vietnam | Dak Lak | Multiplex PCR | 7710 | 2328 | –– | –– | Ascaris Lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 77 | Privat Agniwo et al | 2023 | Mali | Fangouné Bamanan and Diakalèl | Duplicate Urine filtration & Dipstick & Baerman method & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 971 | 487 | 6_14 | –– | Schistosoma spp. |

| 78 | Sangeeta Deka et al | 2021 | India | North-eastern India | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 435 | 50 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 79 | A.Daryani et al | 2012 | Iran | Sari | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 1100 | 56 | 7_14 | –– | Enterobius.vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis, Trichostrongylus spp. |

| 80 | Orabi | 2000 | Palestine | Nablus | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 220 | 8 | 1_6 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 81 | LEE et al | 2000 | Philippines | Roxas | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 301 | 262 | 1_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Opisthorchis spp., Echinostoma spp., Rhabditis spp. |

| 82 | LEE et al | 2000 | Philippines | Legaspi | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 64 | 30 | 3_20 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Opisthorchis spp., Echinostoma spp., Rhabditis spp. |

| 83 | Salahi et al | 2019 | Iran | Khodabandeh | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 520 | 17 | 3_7 | –– | Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 84 | Yong et al | 2000 | Nepal | Baharatpur | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 300 | 62 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Fasciola spp., Hookworm |

| 85 | Shahabi et al | 2000 | Iran | Shahriar | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1902 | 294 | 6_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Fasciola spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Trichostrongylus spp., Dicrocoelium dendriticum |

| 86 | Chandrasena et al | 2004 | Sri Lanka | Mahiyangana | Direct smear | 145 | 28 | 6_15 | –– | Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 87 | Saifi et al | 2001 | India | Budaun | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) | 367 | 49 | 5_13 | –– |

Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana |

| 88 | Waikagul et al | 2002 | Thailand | Nan | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1010 | 606 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis, Opisthorchis spp. |

| 89 | LEE et al | 2002 | Cambodia | Kampongcham | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 251 | 138 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Opisthorchis spp., Echinostoma spp., Rhabditis spp. |

| 90 | Sanprasert et al | 2016 | Thailand | –– | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1909 | 131 | 1_23 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Fasciola spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 91 | Piangiai et al | 2003 | Thailand | Chiang Mal | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 403 | 120 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Opisthorchis spp. |

| 92 | Rita Khanal et al | 2018 | Nepal | Rupandehi | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 217 | 114 | 4_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp. |

| 93 | Bakarman et al | 2019 | Saudi Arabia | Jeddah | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 581 | 1 | 6_16 | 11.6 | Hymenolepis nana |

| 94 | Nematian et al | 2004 | Iran | Tehran | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 19,209 | 826 | –– | 8.5 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 95 | Jintana Yanola et al | 2018 | Thailand | Omkoi | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 375 | 33 | 6_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 96 | Saksirisampant et al | 2004 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 781 | 146 | 6_19 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 97 | Daryani et al | 2005 | Iran | Ardabil | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1070 | 16 | 7_13 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 98 | Chandrashekhar et al | 2005 | Nepal | Kaski | Direct smear | 2091 | 117 | 6_10 | 8.8 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 99 | Sadjjadi and N Tanideh | 2005 | Iran | Marvdasht | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 337 | 6 | 3_6 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 100 | Shoji Uga et al | 2005 | Vietnam | Hanoi | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 217 | 144 | 14_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Fasciola spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 101 | Wongiindanon et al | 2005 | Thailand | Samut Sakhon | Direct smear | 4014 | 152 | 5_7 | –– | Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis, Opisthorchis spp. |

| 102 | Chhakda et al | 2005 | Cambodia | –– | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 1616 | 546 | –– | 11.3 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 103 | Kanoa et al | 2006 | Palestine | Gaza | Direct smear & staining | 432 | 53 | 6_11 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 104 | K. Patel and R. Khandekar | 2006 | Oman | Dahahira | Direct smear | 436 | 41 | 9_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 105 | Saksirisampant et al | 2006 | Thailand | –– | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1037 | 7 | 3_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 106 | Yaicharoen et al | 2006 | Thailand | Nakhon Pathom | Direct smear | 814 | 29 | 7_13 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis, Opisthorchis spp. |

| 107 | Aksoy et al | 2007 | Turkey | Izmir | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 1127 | 128 | 7_14 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 108 | Aminzadeh et al | 2007 | Iran | Varamin | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 293 | 16 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 109 | Almerie et al | 2008 | Syria | Damascus | Direct smear | 1469 | 5 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 110 | Gyawali et al | 2009 | Nepal | Dharan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 182 | 10 | 4_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 111 | Nagwa Aly and Magda M.M. Mostafa | 2010 | Saudi Arabia | Tabuk | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 812 | 10 | 2_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 112 | Sehgal et al | 2010 | India | Chandigarh | Direct smear | 360 | 22 | –– | –– | Hymenolepis nana |

| 113 | Shwkat Ahmad Wani et al | 2010 | India | Kashmir | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 352 | 265 | 1_15 | 9.1 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 114 | Singh et al | 2010 | India | Srinagar | Direct smear | 514 | 191 | 5_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp. |

| 115 | Samal et al | 2016 | India | Khurda | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 250 | 20 | 1_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm |

| 116 | Rayan et al | 2010 | India | –– | Direct smear | 195 | 61 | 5_11 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 117 | Matthys et al | 2011 | Tajikistan | –– | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 594 | 208 | 7_11 | 9.1 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 118 | S. Hussein | 2011 | Palestine | Nablus | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining & PCR | 735 | 40 | 7_13 | 9.5 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 119 | Bhandari et al | 2011 | Nepal | Kavrepalanchowk | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 360 | 81 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 120 | D.Chandi and J.Lakhani | 2018 | India | Bhaili | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 250 | 27 | 6_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 121 | A Aher and S Kulkarni | 2011 | India | Ahmednagar | Direct smear | 624 | 54 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 122 | Nithyamathi et al | 2016 | Malaysia | Peninsular | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1760 | 108 | 7_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 123 | Abdulsalam et al | 2012 | Malaysia | Pahang | Direct smear | 300 | 208 | 6_13 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 124 | Bhattachan et al | 2015 | Nepal | Chitwan | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 296 | 23 | 5_18 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 125 | Panda et al | 2012 | India | Nellimarla Mandal | Direct smear | 124 | 17 | 6_9 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 126 | Shrestha et al | 2012 | Nepal | Baglung | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 260 | 26 | ≤ 4 −10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 127 | Al-Delaimy et al | 2014 | Malaysia | Lipis | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 498 | 261 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 128 | Al-Mekhlafi et al | 2019 | Malaysia | Peninsular | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining & PCR | 1142 | 180 | 6_19 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 129 | Bilakshan sah et al | 2013 | Nepal | Itahari | Direct smear | 200 | 26 | 12_15 | ––- | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 130 | J.lakhani et al | 2013 | India | Vadodara | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 140 | 16 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 131 | Kitvatanachai et al | 2013 | India | Muang Pathum Thani | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 202 | 1 | 7_12 | –– | Hookworm |

| 132 | Raj Tiwari et al | 2013 | Nepal | Dadeldhura | Direct smear | 530 | 161 | 4_12 | –- | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 133 | Ullah et al | 2014 | Pakistan | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Direct smear & staining | 222 | 222 | 4_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Toxocara spp. |

| 134 | Pradhan et al | 2014 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear | 194 | 9 | 6_10 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 135 | Hajare et al | 2022 | Ethiopia | Ofa | Direct smear | 391 | 357 | 5_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 136 | Muharram | 2023 | Yemen | Sana'a | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 500 | 9 | 6_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp. |

| 137 | Jada et al | 2016 | Malaysia | Kancheepuram | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) | 335 | 133 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 138 | Oladejo So et al | 2018 | Nigeria | Imo | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 132 | 26 | 1_45 | –– |

Ascaris Lumbricoides, Fasciola spp., Schistosoma spp., Hookworm |

| 139 | Kiran et al | 2014 | India | Bhopal | Direct smear | 300 | 45 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm |

| 140 | Jaiswal et al | 2014 | Nepal | Kaski | Direct smear | 163 | 6 | 3_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 141 | Pandey et al | 2015 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 300 | 6 | 7_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana |

| 142 | R Polseela and A Vitta | 2015 | Thailand | Phitsanulok | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 352 | 12 | 7_15 | –– | Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 143 | Altinoz Aytar et al | 2015 | Turkey | Yıgılca | Direct smear & staining | 523 | 89 | 6_19 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 144 | Punsawad et al | 2018 | Thailand | Nopphitam | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 299 | 34 | 7_12 | ––- | Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 145 | Aschalew Gelaw et al | 2013 | Ethiopia | Gondar | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 304 | 82 | 9_13 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 146 | Bhandari et al | 2015 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 507 | 18 | 3_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 147 | K Yadav and S Prakash | 2016 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & staining | 507 | 129 | 6_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura |

| 148 | Dahal et al | 2022 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear | 409 | 39 | 5_18 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 149 | Bansal et al | 2018 | India | Rishikesh | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) & staining | 461 | 26 | < 10 | 7.26 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 150 | Limbu et al | 2021 | Nepal | Dharan | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 116 | 4 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm |

| 151 | Shrestha et al | 2016 | Nepal | Bhaktapur | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 184 | 34 | 3_14 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 152 | Dhital et al | 2016 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 600 | 11 | 3_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp. |

| 153 | Doi et al | 2016 | Thailand | Sakon Nakhon | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 417 | 121 | 4_12 | ––- | Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Opisthorchis spp., Heterophyes Heterophyes, Gongylonema spp., |

| 154 | Ankan et al | 2016 | Turkey | Kutahya | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 471 | 57 | 5_11 | 7.91 | Enterobius vermicularis |

| 155 | Safi et al | 2019 | Afghanistan | –– | kato-katz method | 2263 | 602 | 8_10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 156 | Korzeniewski | 2016 | Afghanistan | –– | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 500 | 189 | 7_18 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Fasciola spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis, Trichostrongylus spp., Dicrocoelium dendriticum |

| 157 | Al-Mekhlafi et al | 2016 | Yemen | Sana'a | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1218 | 209 | 5_15 | 9.3 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 158 | AL-Fakih et al | 2022 | Yemen | –– | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 600 | 60 | 7_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 159 | Alsubaie et al | 2016 | Yemen | Ibb | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 258 | 92 | 8_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 160 | Ghani et al | 2016 | Pakistan | Lahore | Direct smear | 300 | 36 | < 10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 161 | Turki et al | 2017 | Iran | Bandar Abbas | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 1456 | 4 | 6_14 | 9.2 | Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 162 | Bahmani et al | 2017 | Iran | Sanandaj | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 400 | 15 | 7_15 | –– | Hymenolepis nana |

| 163 | Jameel et al | 2017 | Iraq | Zakho | Direct smear | 103 | 18 | 6_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 164 | Jaiswal et al | 2017 | Nepal | Damauli | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 150 | 27 | 7_13 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 165 | Tenali et al | 2018 | India | –– | Direct smear & staining | 1246 | 208 | 5_18 | 12.6 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 166 | Kyaw et al | 2018 | Thailand | Ratchaburi | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 252 | 12 | 9_17 | 11.86 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm |

| 167 | Tandukar et al | 2018 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining & PCR | 333 | 9 | 5_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 168 | Gopalakrishnan et al | 2018 | India | Anakaputhur | Direct smear | 250 | 19 | 13_18 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm |

| 169 | Assavapongpaiboon et al | 2018 | Thailand | Saraburi | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 263 | 5 | 4_15 | 7.9 | Strongyloides stercoralis, Opisthorchis spp. |

| 170 | Upama et al | 2019 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 330 | 21 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 171 | Rather et al | 2019 | India | Kashmir | Concentration (Sedimentation) | 130 | 41 | 5_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura,.Taenia spp |

| 172 | Gurung et al | 2019 | Nepal | Kathmandu | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 160 | 42 | < 10 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 173 | Qasem et al | 2020 | Yemen | Ibb | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 300 | 27 | 6_16 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 174 | Sah et al | 2021 | Nepal | Janakpurdham | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 155 | 14 | 5_17 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 175 | T Alharrazi | 2022 | Yemen | Taiz | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 478 | 100 | 6_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 176 | Edrees et al | 2022 | Yemen | Amran | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 360 | 33 | 6_15 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 177 | Edrees et al | 2022 | Yemen | Sana’a | Direct smear | 173 | 29 | 9_13 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 178 | Khan et al | 2022 | Pakistan | Lower Dir | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 184 | 58 | 10_17 | 14 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Hookworm |

| 179 | Salih et al | 2022 | Iraq | Duhok | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 1172 | 158 | 6_12 | –– | Enterobius vermicularis |

| 180 | Al-Mekhlafi et al | 2023 | Yemen | Sana'a | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 400 | 133 | 7_12 | 9.52 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Schistosoma spp., Enterobius vermicularis, Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 181 | Karmacharya et al | 2023 | Nepal | Bhaktapur | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 190 | 7 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Taenia spp., Schistosoma spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 182 | Subhan et al | 2023 | Pakistan | Bajawar | Direct smear | 402 | 243 | 4_12 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Trichuris trichiura, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 183 | Njenga et al | 2022 | Kenya | Nairobi | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 406 | 63 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 184 | Mekonnen et al | 2024 | Ethiopia | Hakim | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 333 | 34 | 5_17 | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm |

| 185 | Erismann et al | 2016 | Burkina faso | ––- | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 385 | 25 | 8_14 | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Schistosoma spp., Hookworm |

| 186 | Ikponmwosa Owen Evbuomwan et al | 2022 | Nigeria | Benin | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 249 | 164 | –– | –– | Strongyloides stercoralis |

| 187 | Z Khudrui | 2000 | Palestine | Qalqilia | Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) | 1329 | 153 | –– | –– | Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Enterobius vermicularis |

| 188 | Padmaja et al | 2014 | India | Amalapuram | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 200 | 13 | –– | –– | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis |

| 189 | Richert et al | 2024 | Madagascar | Ambatoboeny | Direct smear | 241 | 14 | 0_17 | 11.8 | Hymenolepis nana, Taenia spp., Hookworm, Enterobius vermicularis, Trichuris trichiura, Ascaris lumbricoides |

| 190 | Shaddel et al | 2024 | Iran | Tehran | Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 250 | 9 | 7_14 | 10.17 | Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm, Hymenolepis nana |

Table 2.

Sub–group analysis based on HDI, Educational level, Source of sample, Diagnostic method, Average temperature, Annual rainfall, Climate, GBD Geographies regions, WHO region, Countries, Humidity, Age, Mean age, Gender and District/City/province in included studies

| Variables | No studies | Sample size | Infected | Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 τ2 p-value | |||||

| HDI | |||||

| Very High human development | 31 | 25,401 | 4929 | 16.94 (9.5–25.98) | 99 9.76 P <.001 |

| High human development | 44 | 104,595 | 7876 | 17.39 (10.86–25.07) | 99 10.02 P <.001 |

| Medium human development | 68 | 45,167 | 9477 | 15.69 (11.91–19.87) | 99 5.14 P <.001 |

| Low human development | 47 | 24,825 | 9409 | 35.35 (25.97–45.34) | 99 12.58 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Income level | |||||

| High income level | 4 | 2219 | 66 | 2.67 (0.00–11.52) | 96 1.22 P <.001 |

| Upper middle income level | 57 | 115,458 | 10,965 | 15.46 (10.22–21.55) | 99 8.63 P <.001 |

| Lower middle income level | 91 | 61,616 | 16,112 | 22.78 (17.41–23.63) | 99 10.16 P <.001 |

| Low income level | 38 | 20,695 | 6432 | 26.95 (18.74–36.03) | 99 8.75 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Educational level | |||||

| Secondary school | 7 | 1788 | 212 | 12.65 (7.42–19.01) | 91 1.26 P <.001 |

| Primary school | 154 | 175,407 | 29,356 | 21.86 (17.96–26.03) | 99 9.42 P <.001 |

| Primary & Secondary school | 29 | 22,793 | 4007 | 0.1675 (0.0829–0.2739) | 99 12.44 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Type of sample | |||||

| Stool & Urine | 4 | 12,310 | 3169 | 47.27 (18.72–76.83) | 99 12.50 P <.001 |

| Stool | 180 | 185,382 | 29,698 | 20.24 (16.71–24.01) | 99 9.53 P <.001 |

| Stool & Blood | 5 | 1325 | 221 | 13.93 (4.46–27.40) | 97 3.54 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Diagnostic method | |||||

| Direct smear | 37 | 24,959 | 5404 | 19.85 (12.63–28.22) | 99 9.10 P <.001 |

| Concentration (Sedimentation) | 26 | 13,745 | 2944 | 22.73 (13.3–33.8) | 99 10.14 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) | 64 | 51,350 | 6016 | 15.18 (10.76–20.18) | 99 7.04 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining | 18 | 13,044 | 1424 | 10.35 (4.9–17.5) | 99 4.97 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 5 | 2397 | 620 | 30.59 (17.08–46.04) | 98 3.19 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & kato-katz method | 14 | 22,380 | 6949 | 47.04 (30.19–64.25) | 99 10.95 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) | 4 | 2241 | 364 | 18.56 (8.21–31.86) | 97 2.39 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Scotch Tape Test | 5 | 46,858 | 1942 | 21.63 (0.00–65.87) | 99 27.72 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & staining | 6 | 4102 | 1361 | 40.15 (10.15–75.07) | 99 20.29 P <.001 |

| Kato-katz method | 4 | 6527 | 3085 | 51.90 (20.65–80.34) | 99 11.48 P <.001 |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Flotation) & staining | 1 | 461 | 26 | 5.64 (3.84–8.10) | -—- |

| Duplicate Urine filtration & Dipstick & Baerman method & Concentration (Flotation & Sedimentation) | 2 | 2004 | 883 | 44.20 (33.02–55.68) | 96 0.66 P <.001 |

| Multiplex PCR | 1 | 7710 | 2328 | 30.19 (29.13–31.18) | -—- |

| Direct smear & Concentration (Sedimentation) & staining & PCR | 3 | 2210 | 229 | 7.19 (1.70–15.96) | 97 1.46 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Average temperature | |||||

| 0–10 | 2 | 984 | 222 | 16.10 (0.00–55.82) | 99 9.56 P <.001 |

| 10–20 | 61 | 55,359 | 6493 | 11.38 (7.77–15.57) | 99 5.83 P <.001 |

| > 20 | 127 | 143,645 | 26,860 | 25.94 (21.15–31.04) | 99 10.39 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Humidity | |||||

| < 40 | 33 | 40,847 | 3497 | 12.20 (7.40–17.99) | 99 5.54 P <.001 |

| 40–75 | 134 | 89,849 | 22,803 | 21.42 (17.10–26.07) | 99 10.14 P <.001 |

| > 75 | 23 | 69,673 | 6978 | 14.85 (8.75–22.20) | 99 12.23 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Annual rainfall | |||||

| < 400 | 43 | 49,326 | 4639 | 11.63 (7.73–16.20) | 99 4.79 P <.001 |

| 400–1000 | 48 | 40,710 | 11,581 | 30.85 (21.77–40.73) | 99 13.21 P <.001 |

| 1001–1500 | 59 | 22,907 | 5043 | 16.63(11.79–22.11) | 99 7.20 P <.001 |

| > 1500 | 41 | 90,421 | 12,511 | 25.89 (17.68–35.05) | 99 10.48 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Climate | |||||

| Desert climate | 48 | 25,097 | 6986 | 28.28 (20.04–37.33) | 99 11.50 P <.001 |

| Hot-summer Mediterranean climate | 8 | 7292 | 2917 | 27.81 (9.16–51.78) | 99 12.66 P <.001 |

| Humid subtropical climates | 1 | 390 | 14 | 3.59 (2.15–5.93) | -—- |

| Semi-desert climate | 26 | 39,792 | 2782 | 7.60 (4.78–11) | 98 2.25 P <.001 |

| Tropical monsoon climate | 45 | 76,352 | 9916 | 20.82 (13.38–29.39) | 99 11.31 P <.001 |

| Tropical rainforest climate | 18 | 15,817 | 5219 | 35.44 (22.47–49.61) | 99 9.54 P <.001 |

| Tropical savanna climate | 20 | 25,613 | 3880 | 16.57 (8.43–26.74) | 99 7.92 P <.001 |

| Tropical wet-dry climate | 24 | 9635 | 1861 | 15.39 (9.56–22.29) | 99 4.70 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| GBD Geographies regions | |||||

| Caribbean | 2 | 307 | 209 | 63.52 (24.94–94.03) | 97 8 P <.001 |

| Central Asia | 1 | 594 | 208 | 35.02 (31.25–38.91) | -—- |

| Central Europe | 1 | 390 | 14 | 3.59 (2.17–5.95) | -—- |

| Central Latin America | 5 | 14,989 | 5173 | 32.19 (19.54–46.34) | 99 2.72 P <.001 |

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | 1 | 74 | 18 | 24.32 (16.40–35.39) | -—- |

| East Asia | 1 | 44,163 | 93 | 0.21 (0.07–0.15) | -—- |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | 25 | 22,299 | 7209 | 36.63 (24.48–49.71) | 99 11.27 P <.001 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 49 | 56,116 | 6087 | 9.98 (6.71–13.82) | 99 4.39 P <.001 |

| Oceania | 1 | 400 | 22 | 5.50 (3.62–8.15) | -—- |

| South Asia | 72 | 29,770 | 5828 | 16.47 (11.92–21.59) | 99 7.81 P <.001 |

| Southeast Asia | 23 | 25,964 | 6792 | 38.30 (25.52–51.96) | 99 11.21 P <.001 |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 2 | 271 | 88 | 30.39 (14.18–49.56) | 91 1.80 P <.001 |

| West Africa | 1 | 252 | 108 | 42.86 (36.88–49.03) | -—- |

| Western sub-Saharan Africa | 6 | 4399 | 1726 | 36.72 (7.58–72.83) | 99 21.35 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| WHO region | |||||

| African | 30 | 26,291 | 8767 | 35.99 (24.72–48.09) | 99 11.67 P <.001 |

| Americas | 7 | 15,296 | 5382 | 40.73 (24.38–58.21) | 99 5.52 P <.001 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 56 | 57,212 | 6176 | 15.33 (10.19–21.28) | 99 8.55 P <.001 |

| European | 8 | 5513 | 2348 | 23.67 (5.88–48.51) | 99 14.20 P <.001 |

| South-East Asia | 71 | 35,101 | 5390 | 13.24 (9.69–17.24) | 99 5.57 P <.001 |

| Western Pacific | 18 | 60,575 | 5512 | 40.90 (26.74–55.88) | 99 10.44 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Countries | |||||

| Afghanistan | 2 | 2763 | 791 | 31.91 (21.68–43.11) | 95 0.67 P <.001 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 | 385 | 25 | 6.49 (4.38–9.35) | -—- |

| Cambodia | 2 | 1867 | 684 | 44.03 (24.44–64.65) | 97 2.20 P <.001 |

| Colombia | 1 | 6945 | 2182 | 36.10 (34.77–37.21) | -—- |

| Cuba | 2 | 307 | 209 | 63.52 (24.94–94.03) | 97 0.0800 P <.001 |

| Democratic Republic | 1 | 74 | 18 | 24.32 (16.34–35.36) | -—- |

| Egypt | 4 | 3206 | 331 | 10.92 (5.30–18.20) | 97 1.06 P <.001 |

| Ethiopia | 16 | 9058 | 3974 | 37.30 (22.49–53.45) | 99 10.95 P <.001 |

| Guatemala | 1 | 5228 | 1207 | 23.09 (21.93–24.22) | -—- |

| Honduras | 1 | 2554 | 1493 | 58.46 (56.55–60.38) | -—- |

| India | 21 | 7838 | 1805 | 16.02 (9.61–23.60) | 98 4.90 P <.001 |

| Indonesia | 2 | 625 | 362 | 31.60 (0.0–99.92) | 99 44.30 P <.001 |

| Iran | 17 | 33,680 | 1710 | 4.62 (2.89–6.72) | 97 0.86 P <.001 |

| Iraq | 2 | 1275 | 176 | 14.25 (10.78–18.10) | 24 0.07 P =.25 |

| Kenya | 2 | 10,207 | 1709 | 16.67 (15.70–17.66) | 0 0.01 P =.52 |

| Madagascar | 1 | 241 | 14 | 5.81 (3.60–9.61) | -—- |

| Malaysia | 7 | 4807 | 1315 | 39.38 (21.58–58.77) | 99 6.86 P <.001 |

| Mali | 1 | 971 | 487 | 50.15 (46.97–53.34) | -—- |

| Nepal | 33 | 12,647 | 1773 | 11.96 (7.35–17.48) | 98 5.08 P <.001 |

| Nicaragua | 1 | 880 | 238 | 27.05 (24.11–30) | -—- |

| Nigeria | 3 | 1440 | 1196 | 63.25 (16.50–97.87) | 99 19.32 P <.001 |

| Oman | 1 | 436 | 41 | 9.40 (6.94–12.45) | -—- |

| Pakistan | 7 | 1932 | 1060 | 58.61 (29.80–84.54) | 99 15.58 P <.001 |

| Palestine | 6 | 5456 | 959 | 12.73 (5.54–22.28) | 98 2.45 P <.001 |

| Philippines | 3 | 937 | 540 | 60.75 (30.74–86.91) | 98 7.04 P <.001 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 1393 | 11 | 0.62 (0.01–1.95) | 81 0.0015 P =.02 |

| Senegal | 1 | 1603 | 18 | 1.12 (0.42–1.45) | -—- |

| Slovakia | 1 | 390 | 14 | 3.59 (2.11–5.90) | -—- |

| South Africa | 2 | 271 | 88 | 30.39 (14.18–49.56) | 91 1.80 P <.001 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 145 | 28 | 19.31 (13.86–26.59) | -—- |

| Sudan | 4 | 930 | 364 | 40.03 (9.58–76.61) | 98 13.86 P <.001 |

| Syria | 1 | 1469 | 5 | 0.34 (0.09–0.73) | -—- |

| Taiwan | 1 | 44,163 | 93 | 0.21 (0.07–0.15) | -—- |

| Tajikistan | 1 | 594 | 208 | 35.02 (31.28–38.93) | -—- |

| Tanzania | 2 | 1863 | 1148 | 67.41 (14.04–99.96) | 99 17.39 P <.001 |

| Thailand | 14 | 13,846 | 1422 | 9.96 (4–18.17) | 99 5.10 P <.001 |

| The Republic Of Marshall Island | 1 | 400 | 22 | 5.50 (3.59–8.13) | -—- |

| Turkey | 6 | 4529 | 2126 | 26.41 (4.04–58.99) | 99 17.47 P <.001 |

| Venezuela | 1 | 282 | 53 | 18.79 (14.67–23.77) | -—- |

| Vietnam | 3 | 8327 | 2840 | 65.04 (26.48–94.62) | 99 12.23 P <.001 |

| West Africa | 1 | 252 | 108 | 42.86 (36.88–49.03) | -—- |

| Yemen | 10 | 4672 | 728 | 14.85 (8.75–22.20) | 97 2.26 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Age | |||||

| 5–10 | 85 | 102,795 | 12,330 | 19.25 (14.69–24.25) | 99 8.01 P <.001 |

| 10–15 | 85 | 61,428 | 15,140 | 22.32 (16.56–28.68) | 99 11.63 P <.001 |

| Total | 190 | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 108 | 54,944 | 10,029 | 33.15 (28.17–38.33) | 99 7.95 P <.001 |

| Female | 108 | 49,297 | 8102 | 31.09 (26.04–36.37) | 99 8.48 P <.001 |

| Total | 108 | ||||

| District/City/province | |||||

| Aga | 1 | 726 | 154 | 21.21 (18.24–24.21) | -—- |

| Ahmednagar | 1 | 624 | 54 | 8.65 (6.63–11.06) | -—- |

| Amalapuram | 1 | 200 | 13 | 6.50 (3.88–10.84) | -—- |

| Ambara | 1 | 375 | 95 | 25.33 (21.20–29.97) | -—- |

| Ambatoboeny | 1 | 241 | 14 | 5.81 (3.31–9.35) | -—- |

| Amber | 1 | 384 | 55 | 14.32 (11.14–18.15) | -—- |

| Amhara | 1 | 798 | 248 | 31.08 (27.93–34.35) | -—- |

| Amran | 1 | 360 | 33 | 9.17 (6.69–12.67) | -—- |

| Anakaputhur | 1 | 250 | 19 | 7.60 (4.51–11.21) | -—- |

| Angolela | 1 | 664 | 75 | 11.30 (9.14–13.96) | -—- |

| Antioquia | 1 | 6045 | 2182 | 36.10 (34.86–37.28) | -—- |

| Ardabil | 1 | 1070 | 16 | 1.50 (0.95–2.44) | -—- |

| Baglung | 1 | 260 | 26 | 10 (6.87–14.21) | -—- |

| Baharatpur | 1 | 300 | 62 | 20.67 (16.51–25.64) | -—- |

| Bahir Dar | 1 | 2372 | 1463 | 61.68 (59.70–63.61) | -—- |

| Bajawar | 1 | 402 | 243 | 60.45 (55.59–65.11) | -—- |

| Bandar Abbas | 1 | 1456 | 4 | 0.27 (0.06–0.65) | -—- |

| Benin | 1 | 249 | 164 | 65.86 (59.75–71.343) | -—- |

| Berber | 1 | 100 | 87 | 87 (78.83–91.97) | -—- |

| Bhaili | 1 | 250 | 27 | 10.80 (7.43–15.18) | -—- |

| Bhaktapur | 3 | 568 | 45 | 6.68 (0.55–18.20) | 94 2.31 P <.001 |

| Bhopal | 1 | 300 | 45 | 15 (11.24–19.35) | -—- |

| Bijapur | 1 | 58 | 6 | 10.34 (5.45–21.21) | -—- |

| Bochesa | 1 | 384 | 84 | 21.88 (17.90–26.18) | -—- |

| Budaun | 1 | 367 | 49 | 13.35 (10.30–17.26) | -—- |

| Bushehr | 1 | 203 | 23 | 11.33 (7.77–16.50) | -—- |

| Chandigarh | 1 | 360 | 22 | 6.11 (3.98–9) | -—- |

| Chiang Mai | 1 | 781 | 146 | 18.69 (15.85–21.35) | -—- |

| Chiang Mal | 1 | 403 | 120 | 29.78 (25.36–34.31) | -—- |

| Chitwan | 1 | 296 | 23 | 7.77 (5.35–11.49) | -—- |

| Dadeldhura | 1 | 530 | 161 | 30.38 (26.62–34.42) | -—- |

| Dahahira | 1 | 436 | 41 | 9.40 (7.07–12.56) | -—- |

| Dak Lak | 1 | 7710 | 2328 | 30.19 (29.18–31.23) | -—- |

| Dakar | 1 | 1603 | 18 | 1.12 (0.62–1.68) | -—- |

| Damanhur | 1 | 810 | 47 | 5.80 (4.27–7.51) | -—- |

| Damascus | 1 | 1469 | 5 | 0.34 (0.16–0.81) | -—- |

| Damauli | 1 | 150 | 27 | 18 (12.74–24.97) | -—- |

| Damghan | 1 | 764 | 70 | 9.16 (7.35–11.45) | -—- |

| Davao del Norte | 1 | 572 | 248 | 43.36 (39.35–47.45) | -—- |

| Democratic Republic of Sao Tome | 1 | 252 | 108 | 42.86 (36.94–49.03) | -—- |

| Dera | 1 | 382 | 211 | 55.24 (50.22–60.13) | -—- |

| Dharan | 2 | 298 | 14 | 4.62 (2.32–7.57) | 0 0.02 P =.45 |

| Dharan Submetropolitan | 1 | 400 | 43 | 10.75 (8.10–14.19) | -—- |

| Dir | 1 | 324 | 266 | 82.10 (77.94–86.39) | -—- |

| Duhok | 1 | 1172 | 158 | 13.48 (11.59–15.51) | -—- |

| Eskisehir | 1 | 132 | 10 | 7.58 (4.06–13.30) | -—- |

| Fangouné Bamanan and Diakalèl | 1 | 971 | 487 | 50.15 (47.01–53.29) | -—- |

| Gaza | 1 | 432 | 53 | 12.27 (9.57–15.75) | -—- |

| Golestan | 1 | 800 | 31 | 3.87 (2.71–5.42) | -—- |

| Gondar | 1 | 304 | 82 | 26.97 (22.28–32.22) | -—- |

| Hakim | 1 | 333 | 34 | 10.21 (7.52–14.03) | -—- |

| Hanoi | 1 | 217 | 144 | 66.36 (59.82–72.27) | -—- |

| Harbu | 1 | 400 | 38 | 9.50 (6.89–12.67) | -—- |

| Huaphan | 1 | 74 | 18 | 24.32 (16.34–35.37) | -—- |

| Ibb | 2 | 558 | 119 | 20.70 (2.04–51.25) | 98 5.39 P <.001 |

| Imo | 1 | 132 | 26 | 19.70 (13.98–27.41) | -—- |

| Itahari | 1 | 200 | 26 | 13 (9.17–18.48) | -—- |

| Izmir | 1 | 1127 | 128 | 11.36 (9.65–13.36) | -—- |

| Jahrom | 1 | 431 | 1 | 0.23 (0.12–1.40) | -—- |

| Jakarta | 1 | 157 | 2 | 1.27 (0.62–4.80) | -—- |

| Janakpurdham | 1 | 155 | 14 | 9.03 (5.68–14.77) | -—- |

| Jaragedo | 1 | 396 | 72 | 18.18 (14.74–22.32) | -—- |

| Jeddah | 1 | 581 | 1 | 0.17 (0–0.82) | -—- |

| Kampongcham | 1 | 251 | 138 | 54.98 (48.80–60.98) | -—- |

| Kancheepuram | 1 | 335 | 133 | 39.70 (34.61–45.03) | -—- |

| Kashmir | 2 | 482 | 306 | 53.99 (13.92–91.16) | 98 9.95 P <.001 |

| Kaski | 2 | 2254 | 123 | 5.17 (3.75–6.80) | 0 0.02 P =.34 |

| Kathmandu | 12 | 4523 | 929 | 14.53 (4.36–29.18) | 99 9.90 P <.001 |

| Kavrepalanchowk | 1 | 360 | 81 | 22.50 (18.50–27.10) | -—- |

| Kenya | 1 | 9801 | 1646 | 16.79 (15.91–17.40) | -—- |

| Khan Younis | 2 | 2740 | 705 | 24.99 (7.88–47.68) | 99 2.94 P <.001 |

| Khartoum | 2 | 620 | 248 | 30.42 (7.32–60.69) | 97 4.79 P <.001 |

| Khodabandeh | 1 | 250 | 17 | 3.27 (2.10–5.22) | -—- |

| Khurda | 1 | 250 | 20 | 8 (5.39–12.17) | -—- |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 1 | 222 | 222 | 0 (98.23–99.99) | -—- |

| Kutahya | 1 | 471 | 51 | 12.10 (9.36–15.27) | -—- |

| Lahore | 1 | 300 | 36 | 12 (8.92–16.27) | -—- |

| Lalitpur | 1 | 1392 | 40 | 2.87 (2.04–3.82) | -—- |

| Legaspi | 1 | 64 | 30 | 46.88 (35.35–58.81) | -—- |

| Lipis | 1 | 498 | 261 | 52.41 (48.02–56.76) | -—- |

| Lokhim | 1 | 359 | 31 | 8.64 (6.23–12.07) | -—- |

| Lorestan | 1 | 366 | 36 | 9.84 (7.16–13.29) | -—- |

| Lower Dir | 1 | 184 | 58 | 31.52 (25.36–38.61) | -—- |

| Mahiyangana | 1 | 145 | 28 | 19.31 (13.76–26.53) | -—- |

| Maksegnit and Enfranz | 1 | 520 | 352 | 64 (59.90–67.82) | -—- |

| Marvdasht | 1 | 337 | 6 | 1.78 (0.83–3.84) | -—- |

| Matanzas | 1 | 107 | 46 | 42.99 (34.12–52.44) | -—- |

| Mthatha | 1 | 162 | 65 | 40.12 (32.96–47.82) | -—- |

| Muang Pathum Thani | 1 | 202 | 1 | 0.5 (0.1–2.79) | -—- |

| Nablus | 2 | 955 | 48 | 4.84 (3.23–6.74) | 5.39 0 P =.30 |

| Nairobi | 1 | 406 | 63 | 15.52 (12.26–19.31) | -—- |

| Nakhon Pathom | 1 | 814 | 29 | 3.56 (2.47–5.05) | -—- |

| Nan | 1 | 1010 | 606 | 60 (56.96–63.01) | -—- |

| Nellimarla Mandal | 1 | 124 | 17 | 13.71 (8.93–21) | -—- |

| Nopphitam | 1 | 299 | 34 | 11.37 (8.06–15.31) | -—- |

| North‑eastern India | 1 | 435 | 50 | 11.49 (8.77–14.78) | -—- |

| Nyamikoma | 1 | 830 | 752 | 90.60 (88,46–92.44) | -—- |

| Ofa | 1 | 391 | 357 | 91.30 (88.03–93.64) | -—- |

| Ogun State | 1 | 1059 | 1006 | 95 (93.69–96.34) | -—- |

| Ombda | 1 | 210 | 29 | 13.81 (9.70–19.06) | -—- |

| Omkoi | 1 | 375 | 33 | 8.80 (6.24–12.02) | -—- |

| Pahang | 1 | 300 | 208 | 69.33 (63.88–74.24) | -—- |

| Palajunoj | 1 | 5228 | 1207 | 23.09 (21.84–24.14) | -—- |

| Peninsular | 1 | 2902 | 288 | 10.44 (3.03–21.56) | 98 1.21 P <.001 |

| Peshawar | 1 | 200 | 140 | 70 (63.29–75.86) | -—- |

| Phitsanulok | 1 | 352 | 12 | 3.41 (2–5.9) | -—- |

| Pinar del Río | 1 | 200 | 163 | 81.50 (75.49–86.20) | -—- |

| Pokhara | 1 | 100 | 6 | 6 (2.88–12.57) | -—- |

| Puducherry | 1 | 1172 | 660 | 56.31 (53.47–59.15) | -—- |

| Qalqilia | 1 | 1329 | 153 | 11.51 (9.69–13.14) | -—- |

| Qom | 1 | 2410 | 119 | 4.94 (4.01–5.75) | -—- |

| Ratchaburi | 1 | 252 | 12 | 4.76 (2.80–8.18) | -—- |

| Rishikesh | 1 | 461 | 26 | 5.64 (3.89–8.15) | -—- |

| Roxas | 1 | 301 | 262 | 87.04 (82.78–90.38) | -—- |

| Rupandehi | 1 | 217 | 114 | 52.53 (45.91–59.06) | -—- |

| Rural coastal Tanzania | 1 | 1033 | 396 | 38.33 (35.40–41.33) | -—- |

| Rwanda | 1 | 109 | 23 | 21.10 (14.74–29.82) | -—- |

| Sakon Nakhon | 1 | 417 | 121 | 29.02 (24.87–33.55) | -—- |

| Samut Sakhon | 1 | 4014 | 152 | 3.79 (3.15–4.34) | -—- |

| Sana’a | 2 | 573 | 162 | 7.75 (0–28.70) | 99 4.12 P <.001 |

| Sanandaj | 1 | 400 | 15 | 3.75 (2.30–6.11) | -—- |

| Sanliurfa | 1 | 1820 | 1759 | 96.65 (95.73–97.39) | -—- |

| Saptari | 1 | 285 | 8 | 2.81 (1.41–5.42) | -—- |

| Saraburi | 1 | 263 | 5 | 1.90 (0.84–4.39) | -—- |

| Sarawak | 1 | 264 | 117 | 44.32 (38.49–50.35) | -—- |

| Sari | 1 | 1100 | 56 | 5.09 (3.87–6.48) | -—- |

| Sekota | 1 | 402 | 38 | 9.45 (6.66–12.44) | -—- |

| Shahriar | 1 | 1902 | 294 | 15.46 (13.68–16.95) | -—- |

| Skardu | 1 | 300 | 95 | 31.67 (26.65–37.13) | -—- |

| South Khorasan | 1 | 2169 | 171 | 7.88 (6.71–8.99) | -—- |

| Srinagar | 1 | 514 | 191 | 37.16 (31.06–41.40) | -—- |

| Suka | 1 | 468 | 360 | 76.92 (72.93–80.56) | -—- |

| Tabuk | 1 | 812 | 10 | 1.23 (0.59–2.17) | -—- |

| Taifg | 1 | 150 | 18 | 12 (7.68–18.14) | -—- |

| Taipei | 1 | 44,163 | 93 | 0.21 (0–0.04) | -—- |

| Taiz | 2 | 863 | 136 | 14.70 (5.44–27.41) | 95 1.22 P <.001 |

| Tam Nong | 1 | 400 | 368 | 92 (88.91–94.26) | -—- |

| Tana | 1 | 520 | 458 | 88.08 (85.04–90.62) | -—- |

| Tanta | 1 | 1520 | 112 | 7.37 (5.94–8.58) | -—- |

| Tapah | 1 | 508 | 308 | 60.63 (56.34–64.83) | -—- |

| Tegucigalpa | 1 | 2554 | 1493 | 58.46 (56.54–60.36) | -—- |

| Tehran | 2 | 19,459 | 835 | 4.20 (3.85–4.56) | 0 0.01 P =.68 |

| Vadodara | 1 | 140 | 16 | 11.43 (7.35–17.91) | -—- |

| Varamin | 1 | 293 | 16 | 5.46 (3.43–8.72) | -—- |

| Wonji Shoa Sugar | 1 | 403 | 312 | 77.42 (73.13–81.28) | -—- |

| Yıgılca | 1 | 523 | 89 | 17.02 (14–20.44) | -—- |

| Zakho | 1 | 103 | 18 | 17.48 (11.56–26.08) | -—- |

| Total | 147 | ||||

Table 3.

Sub-group analysis based on type of helminth parasites

| Type of helminth parasites | No studies | Sample size | Infected | Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 τ2 p-value | |||||||

| Toxocara spp. | 1 | 222 | 23 | 10.36 (7.08–15.13) | - | - | - |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 139 | 123,449 | 12,011 | 9.47 (7.32–11.85) | 97 5.26 P <.001 | ||

| Heterophyes heterophyes | 1 | 417 | 1 | 8.87 (6.34–11.85) | - | - | - |

| Schistosoma spp. | 30 | 26,128 | 2472 | 7.82 (3.43–13.76) | 99 0.0713 P <.001 | ||

| Trichuris trichiura | 105 | 85,018 | 6499 | 5.83 (3.86–8.16) | 99 0.0554 P <.001 | ||

| Hookworms | 92 | 72,923 | 5421 | 4.57 (3.30–6.03) | 97 0.0239 P <.001 | ||

| Hymenolepis nana | 98 | 80,871 | 2427 | 3.03 (2.35–3.78) | 97 0.0099 P <.001 | ||

| Enterobius vermicularis | 86 | 112,682 | 3055 | 2.75 (1.97–3.65) | 98 0.0135 P <.001 | ||

| Rhabditis spp. | 1 | 251 | 6 | 2.39 (1.16–5.18) | - | - | - |

| Taenia spp. | 52 | 55,028 | 877 | 2.34 (1.45–3.42) | 97 0.0129 P <.001 | ||

| Fasciola spp. | 9 | 6440 | 95 | 1.83 (0. 33–4.36) | 95 0.0116 P <.001 | ||

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 33 | 31,326 | 576 | 1.65 (0.76–2.83) | 96 0.0129 P <.001 | ||

| Wuchereria bancrofti | 1 | 1033 | 15 | 1.45 (0.81–2.32) | - | - | - |

| Opisthorchis spp. | 8 | 9092 | 95 | 1.44 (0.23–3.55) | 95 0.0091 P <.001 | ||

| Dicrocoelium dendriticum | 2 | 2402 | 12 | 0.62 (0.04–1.73) | 79 0.11 P <.001 | ||

| Trichostrongylus spp. | 3 | 3502 | 23 | 0.58 (0.01–1.78) | 92 0.0022 P <.001 | ||

| Gongylonema spp. | 1 | 417 | 1 | 0. 24 (0.04–1.33) | - | - | - |

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, as detailed in Supplementary Table 2 [21]. Scores were assigned across three domains: Selection (maximum 5 stars), Comparability (maximum 2 stars), and Outcome (maximum 3 stars).

Studies scoring 7–9 on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale were classified as high quality and included. Studies scoring 4–6 were classified as moderate quality. Studies scoring < 4 or lacking sufficient methodological clarity were excluded due to high risk of bias or insufficient data.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (ZG and HS) using a standardized Excel form. The extracted data included study characteristics, sample size, diagnostic methods, and prevalence rates. Cross-verification was conducted by a third author (AVE) to ensure data accuracy.

A range of statistical techniques was applied to thoroughly assess the worldwide prevalence of helminthic infections in school-aged children. The overall pooled prevalence was calculated using a 95% confidence interval (CI).

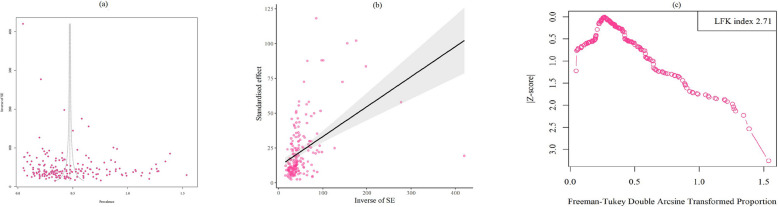

A random-effects model incorporating the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was used to estimate the pooled prevalence. Publication bias was evaluated through Egger’s funnel plot, Begg’s rank test, the Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK) index, and the Doi plot [22].

An LFK index outside ± 2 was classified as major asymmetry, between ± 1 and ± 2 as minor asymmetry, and within ± 1 as symmetry, indicating no publication bias.

To evaluate heterogeneity across studies, Cochrane’s Q test and the inconsistency index (I2) were applied. I2 values were interpreted as follows: 0–25% indicated low heterogeneity, 25–50% moderate heterogeneity, and 50–75% high heterogeneity. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using the meta and metasens packages in R (version 3.6.1) [23].

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The systematic search conducted in this study initially identified 24,256 articles. We retrieved 20,900 records from Google Scholar, 1,879 from PubMed, 1,033 from Web of Science, 352 from Scopus, and 92 from EMBASE.

After screening, 228 full-text articles were reviewed for eligibility. Of these, two studies were excluded due to insufficient data, two for overlapping data, three for lacking participant information, and 31 for not containing original data (e.g., letters, reviews, workshop reports, and theses). Ultimately, 190 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis following critical appraisal (Fig. 1).

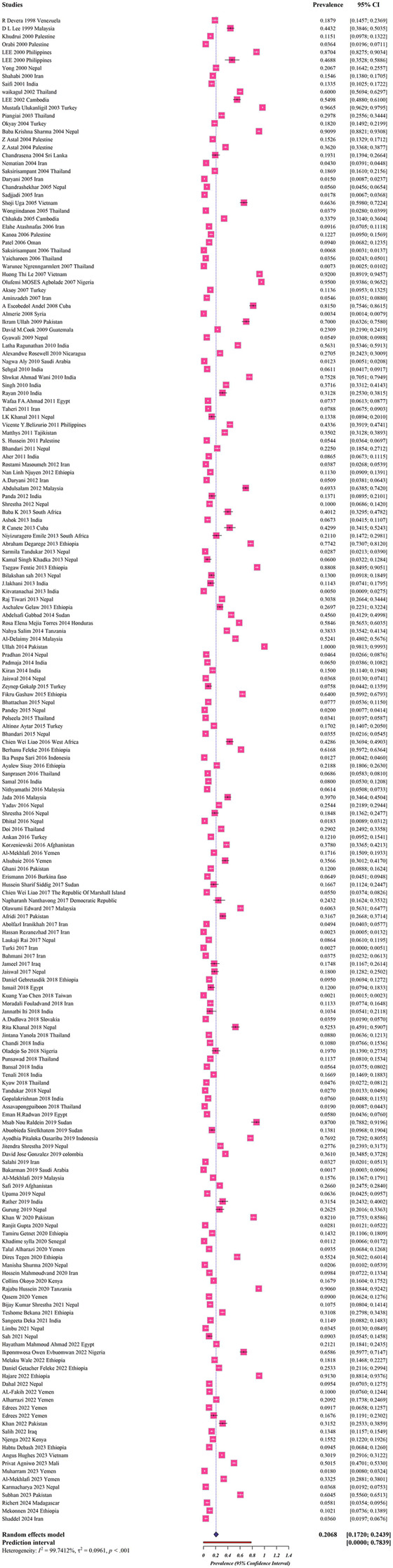

Data on the prevalence of helminthic parasites have been reported from 42 countries, and 199,988 schoolchildren, with Nepal (33 studies) and India (21 studies) being the most frequently represented (Table 2). The estimated global prevalence was 20.6% (17.2–24.3%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for random-effects meta-analysis of helminthic parasites among schoolchildren (The boxes indicate the effect size of the studies (prevalence) and the whiskers indicate its confidence interval for corresponding effect size. There is no specific difference between white and black bars, only studies with a very narrow confidence interval are shown in white. In the case of diamonds, their size indicates the size of the effect, and their length indicates confidence intervals)

According to the data collected in the included studies, a map was generated using QGIS3 software (https://qgis.org/en/site/) to illustrate the prevalence of helminthic parasites among schoolchildren in various regions of the world (Fig. 3a). A Sankey plot indicated that the largest number of studies in GBD regions was related to Nepal (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

The global prevalence of helminthic parasites among schoolchildren in different geographical regions of the world based on included studies (https://qgis.org/en/site/) (a). Additionally, the Sankey plot presents data concerning the majority of studies related to countries and GBD Region based on the included studies (b)

Prevalence based on type of helminthic parasites, type of samples, and diagnostic techniques

The overall prevalence of helminthic parasites among schoolchildren was as detailed: 10.36% (7.08–15.13%) for Toxocara spp., 9.47% (7.32–11.85%) for A. lumbricoides, 8.87% (6.34–11.85%) for Heterophyes heterophyes, 7.82% (3.43–13.76%) for Schistosoma spp., 5.83% (3.86–8.16%) for T. trichiura, 4.57% (3.30–6.03%) for hookworms, 3.03% (2.35–3.78%) for Hymenolepis nana, 2.75% (1.97–3.65%) for Enterobius vermicularis, 2.39% (1.16–5.18%) for Rhabditis spp., 2.34% (1.45–3.42%) for Taenia spp., 1.83% (0.33–4.36%) for Fasciola spp., 1.65% (0.76–2.83%) for Strongyloides stercoralis, 1.45% (0.008–2.32%) for Wuchereria bancrofti, 1.44% (0.23–3.55%) for Opisthorchis spp., 0.62% (0.04–1.73%) for Dicrocoelium dendriticum, 0.58% (0.01–1.78%) for Trichostrongylus spp., 0.24% (0.04–1.33%) for Gongylonema spp. (Table 3).

The highest pooled prevalence based on type of sample was estimated at 47.27% (18.72–76.83%) for studies using both stool and urine samples (Table 2). Based on the diagnostic methods used, the highest prevalence was reported in studies employing the Kato-Katz technique, with an estimated rate of 51.9% (20.65–82.34%) (Table 2).

Prevalence based on WHO regions, country, socio-economic status, educational level, age, and gender

WHO regional estimates of prevalence spanned from 40.90% to 13.24%, with 40.90% (26.74–55.88%) in Western Pacific Region, 40.73% (24.38–58.21%) in Region of the Americas, 35.99% (24.72%– 48.09%) in African Region, 23.67% (5.88–48.51%) in European Region, 15.33% (10.19–21.28%) in Eastern Mediterranean Region, 13.24% (9.69–17.24%) in South-East Asian Region (Table 2). Findings from country-based analyses revealed that Tanzania had the highest prevalence (67.41%, 14.04–99.96%) followed by Vietnam (65.04%, 26.48–94.62%) (Table 2).

The estimated pooled prevalence based on countries income level ranged from 26.95% to 2.67%, with the highest rate observed in low income (26.95%, 18.74–36.03%) (Table 2). Based on the HDI, the highest prevalence was observed in countries with low human development, at 35.35% (25.97–45.34) (Table 2).

Analysis by education level revealed that primary school children had the greatest pooled prevalence, 21.86% (17.96–26.03%) (Table 2). Furthermore, schoolchildren aged 10–15 years showed the highest prevalence rate among all age groups, estimated at 22.32% (16.56–28.68%) (Table 2). Additionally, the highest pooled prevalence as indicated by gender was observed among male schoolchildren, at 33.15% (28.17–38.33%) (Table 2).

Prevalence in association with climatic factors

The analyses revealed that regions with average annual rainfall of 400–1000 mm 30.85% (21.77–40.73%) had the highest rate of pooled prevalence (Table 2). Furthermore, regions with average temperature of >20 °C (25.94%, 21.15–31.04%) had the highest rate of prevalence for helminthic parasites among schoolchildren (Table 2). Moreover, the highest pooled prevalence rate of 21.42% (17.10–26.07%) was observed at a humidity range of 40–75% (Table 2). In addition, we found that tropical rainforest climate had the highest prevalence rate (35.44%, 22.47–49.61%) (Table 2).

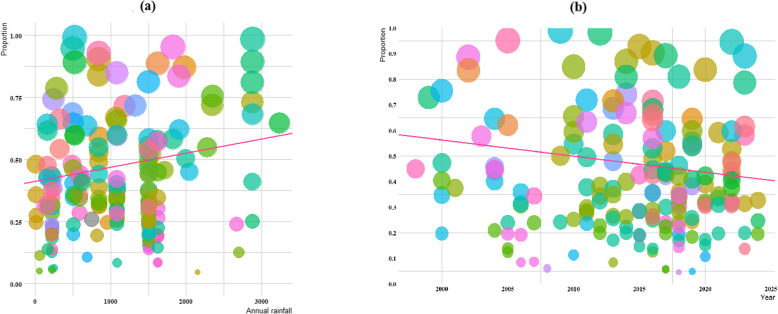

Meta regression

Significant heterogeneity was detected for annual rainfall and year of publication, though the association with annual rainfall was not statistically significant (slop = 13.167, p < 0.07), and year of publication for all studies included (slop = 0.411, p < 0.06) (Fig. 4a-b).

Fig. 4.

The global prevalence of helminthic parasites among schoolchildren in different geographical regions of the world based on annual rainfall and year of publication (the pink line is the regression line, which was plotted based on the intercept and the slope of the regression model). The different coloured bubbles represent the countries under study, and their sizes indicate the effect size of each study

Publication bias

A non-significant publication bias was detected using Egger’s test (t = 5.59, p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a major asymmetry in the Doi plot (LFK index: 2.71) (Fig. 5 a-c).

Fig. 5.

Eggers funnel plot (a) and Beggs plot (b) used to evaluate publication bias related to the global prevalence of helminthic parasites among schoolchildren according to the studies included; colored circles represent individual studies. The central line indicates the effect size, while the other two lines outline the corresponding confidence intervals. The Doi plot (c), which also reflects the publication bias, reveals a Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK) index of 2.71, indicating major asymmetry

Quality assessment

According to the quality assessment, 120 of the 190 studies were rated as high quality (scores of 7–9), and 70 were rated as moderate quality (scores of 4–6) (Supplementary Table 2).

While Egger’s test detected some asymmetry (p < 0.001), this could reflect true heterogeneity due to variations in study design, location, or diagnostic sensitivity. The LFK index of 2.71 further indicated possible publication bias. However, the inclusion of studies with moderate-to-high quality scores (≥ 4) and clear eligibility criteria suggests a reliable evidence base. Still, the interpretation of the results should be with caution due to the inherent risk of reporting bias and study-level variability.

Discussion

This study emphasizes the substantial global impact of helminthic infections in schoolchildren, highlighting their continued role as a major public health concern, especially in low-income and tropical areas. The findings support earlier research showing that helminthiasis remains a significant health problem, predominantly in areas where sanitation is poor, clean water is scarce, and socioeconomic inequalities are noticeable [4, 5, 24, 25].

We observed the highest prevalence rates in the Western Pacific Region and the Region of the Americas, with Tanzania and Vietnam reporting the highest country-specific rates. These patterns reflect the impact of geographical and climatic factors on helminth transmission, as tropical and subtropical regions with warm temperatures and high rainfall offer the most favourable conditions for the survival and spread of STHs [5, 6].

The subgroup analyses in this study demonstrated notably high infection rates in low-income countries, where environmental and infrastructural conditions favour transmission. These findings are in line with studies from similar settings, and they point to socio-economic status as a primary risk determinant of helminth infection [4, 5, 10]. The elevated prevalence in low-income countries further focuses on the role played by poor medical facilities and poverty in perpetuating such infections [9].

Among the helminth species encountered, A. lumbricoides and Toxocara spp. were the most frequently isolated. This dominancy aligns with their widespread distribution and efficient transmission routes, e.g., ingestion of contaminated food or soil [10]. The high occurrence of A. lumbricoides supports its classification as major STHs by the WHO, affecting nearly two billion people globally [11]. These infections pose significant risks to children’s health, frequently causing iron-deficiency anaemia, delayed physical development, learning difficulties, and poor nutritional status [10, 17, 19].