Abstract

The increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections is a major global health concern, with biofilms playing a key role in bacterial persistence and resistance. Biofilms provide a protective matrix that limits antibiotic penetration, enhances horizontal gene transfer, and enables bacterial survival in hostile environments. Conventional antimicrobial therapies are often ineffective against biofilm-associated infections, necessitating the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system has emerged as a revolutionary tool for precision genome modification, offering targeted disruption of antibiotic resistance genes, quorum sensing pathways, and biofilm-regulating factors. However, the clinical application of CRISPR-based antibacterials faces significant challenges, particularly in efficient delivery and stability within bacterial populations. Nanoparticles (NPs) present an innovative solution, serving as effective carriers for CRISPR/Cas9 components while exhibiting intrinsic antibacterial properties. Nanoparticles can enhance CRISPR delivery by improving cellular uptake, increasing target specificity, and ensuring controlled release within biofilm environments. Recent advances have demonstrated that liposomal CRISPR-Cas9 formulations can reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro, while gold nanoparticle carriers enhance editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems. These hybrid platforms also enable co-delivery with antibiotics, producing synergistic antibacterial effects and superior biofilm disruption. Additionally, they can facilitate co-delivery of antibiotics or antimicrobial peptides, further enhancing therapeutic efficacy. This review explores the synergistic integration of CRISPR/Cas9 and nanoparticles in combating biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance. We discuss the mechanisms of action, recent advancements, and current challenges in translating this approach into clinical practice. While CRISPR-nanoparticle hybrid systems hold immense potential for next-generation precision antimicrobial therapies, further research is required to optimize delivery platforms, minimize off-target effects, and assess long-term safety. Understanding and overcoming these challenges will be critical for developing effective biofilm-targeted antibacterial strategies.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, Biofilm, CRISPR/Cas9, Nanoparticles, Gene editing, Antibacterial therapy

Background

Antibiotic-resistant infections pose a significant threat to global health, with biofilm-associated infections being particularly challenging due to their inherent resistance to conventional antimicrobial therapies [1]. Biofilms are structured communities of microorganisms such as bacteria or fungi that adhere to surfaces and are embedded in self-produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [2]. This matrix creates microenvironments that can reduce antibiotic efficacy by altering bacterial metabolism and limiting the penetration of antibiotics [1]. Antimicrobial resistance in bacterial populations arises via two distinct but often co-occurring mechanisms. The first involves heritable genetic adaptations, such as the acquisition of resistance genes (e.g., bla, mecA, ndm-1) through plasmids or transposons, allowing bacteria to enzymatically degrade antibiotics or evade their binding. In contrast, biofilm-mediated resistance is primarily phenotypic, driven by the protective extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, reduced metabolic activity of persister cells, and quorum sensing–regulated efflux systems. Notably, biofilms can exhibit up to 1000-fold greater tolerance to antibiotics compared to planktonic cells [3]. This mechanistic divergence highlights the need for a dual-action approach: CRISPR–Cas systems offer precise targeting of genetic resistance determinants, while nanoparticle-based delivery enhances penetration through biofilm barriers—together forming a synergistic antimicrobial strategy. The CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a natural defense system found in bacteria and archaea that helps them fight viral infections. The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a powerful tool for gene editing, opening new avenues for combating antibiotic resistance. CRISPR/Cas9 allows for precise targeting and modification of specific genetic sequences, offering potential for eradicating antibiotic resistance genes [4]. This system consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease, which introduces double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs Cas9 to the specific genomic sequence. By designing gRNAs to target resistance genes, researchers can disrupt these genes, thereby resensitizing bacteria to antibiotics [5]. Recent advancements have highlighted the synergistic potential of combining the CRISPR/Cas9 system with nanoparticles to enhance the delivery and efficacy of antimicrobial agents against biofilm-associated infections. Nanoparticles, due to their unique physicochemical properties, can facilitate targeted delivery, improve cellular uptake, and protect genetic material from degradation [6]. Various types of nanoparticles, such as lipid-based nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, and metallic nanoparticles, have been explored for this purpose. These carriers can be engineered to possess surface modifications that enhance their interaction with biofilm components, ensuring efficient penetration and delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 constructs directly to the bacterial cells. For instance, liposomal Cas9 formulations reduced P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [7], and CRISPR–gold nanoparticle hybrids demonstrated a 3.5-fold increase in gene-editing efficiency while promoting synergistic action with antibiotics [8, 9]. This combination strategy not only improves the precision of CRISPR/Cas9 targeting but also overcomes the barriers posed by biofilm matrices, thereby enhancing the treatment outcomes of resistant infections [10, 11]. Additionally, the use of nanoparticles can facilitate the co-delivery of antibiotics alongside CRISPR/Cas9, creating a multifaceted approach that attacks bacteria through both genetic disruption and traditional antimicrobial mechanisms. This integrated method holds promise for addressing the growing crisis of antibiotic resistance, particularly in chronic and device-associated infections where biofilms are prevalent [7]. However, current mono-therapeutic strategies—whether based solely on genetic editing or on nanoparticle-mediated delivery—often fall short in overcoming the complex barriers of biofilm-associated resistance. Therefore, there is an urgent need for interdisciplinary combinatorial strategies that integrate molecular gene-targeting tools such as CRISPR/Cas with advanced nanocarriers for precise and effective antimicrobial therapy [8]. This paper aims to provide an in-depth exploration of the integration of CRISPR/Cas9 technology with nanoparticle-based delivery systems, focusing on their combined efficacy in managing and treating antibiotic-resistant infections associated with biofilms.

The antibiotic resistance disaster: a global challenge

Antibiotic resistance represents one of the most urgent threats to global health, food security, and modern development. The rapid emergence and spread of resistant bacteria negatively affect the efficacy of antibiotics, which are crucial for treating bacterial infections. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), antibiotic resistance causes an estimated 700,000 deaths annually, a figure projected to rise dramatically if current trends continue (WHO, 2020). Antibiotic resistance is induced through genetic mutations or the acquisition of resistance genes via horizontal gene transfer. The primary mechanisms include enzymatic degradation or modification where bacteria produce enzymes such as beta-lactamases that deactivate antibiotics [12], alteration of target sites through mutations in bacterial proteins that prevent antibiotic binding [13], efflux pumps that bacteria use to expel antibiotics before they can exert their effects [14], and reduced permeability resulting from changes in the bacterial cell membrane that decrease antibiotic uptake [15]. Several factors accelerate the development and spread of antibiotic resistance, including overuse and misuse of antibiotics through inappropriate prescribing, self-medication, and over-the-counter availability [14, 16], agricultural use where antibiotics are used in livestock for growth promotion and disease prevention fostering resistant strains [17], poor infection control with inadequate hygiene and sanitation in healthcare settings and communities facilitating the spread of resistant bacteria [18], and global travel and trade which increase the dissemination of resistant strains across borders [19]. The consequences of antibiotic resistance are profound, leading to increased morbidity and mortality as resistant infections are harder to treat, resulting in longer illnesses and higher death rates [20]. It also imposes an economic burden due to higher healthcare costs from prolonged hospital stays, additional tests, and more expensive treatments (Smith & Coast, 2013), and threatens medical procedures like surgeries, cancer chemotherapy, and organ transplants, which become riskier without effective antibiotics [21]. Addressing this crisis requires a multifaceted approach, including antibiotic stewardship to promote the appropriate use of antibiotics in healthcare and agriculture [22], enhanced global monitoring of antibiotic resistance patterns (WHO, 2020), investment in new antibiotics, vaccines, and diagnostic tools [23], raising public awareness about the risks of antibiotic misuse, and strengthening hygiene practices, vaccination programs, and infection control measures. Through stewardship, surveillance, research, and education, the spread of resistance can be slowed, preserving the efficacy of existing antibiotics for future generations [18].

Biofilm structure and ultrastructural review of bacterial biofilms

The biofilm structure is highly organized, often displaying a heterogeneous architecture characterized by microcolonies interspersed with water channels that facilitate nutrient distribution and waste removal [1, 2, 24]. Biofilm formation begins with the adhesion of microorganisms to a surface, followed by the production of EPS, which holds the cells together and anchors the biofilm to the substrate. The process involves multiple stages, starting from initial attachment, irreversible attachment, maturation, and finally dispersion. Biofilms can consist of a single species of bacteria or multiple species, often including fungi and other microorganisms in complex communities. The extracellular matrix, composed primarily of polysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), forms a protective barrier that limits the penetration of antibiotics and plays a pivotal role in maintaining biofilm integrity and resilience. This matrix is not only a physical impediment but also a source of microenvironments within the biofilm, where bacterial cells experience [7, 24]. The heterogeneous structure of biofilms creates microenvironments with varying levels of nutrient availability, pH, oxygen, and waste products, which can contribute to the survival of microorganisms even under challenging conditions [21, 25, 26]. At the ultrastructural level, bacterial biofilms exhibit a stratified organization. The basal layer, in close contact with the surface, consists of densely packed cells that form strong adhesions via adhesins and pili, contributing to the initial attachment phase. Above this layer, microcolonies develop, often surrounded by a dense EPS matrix that acts as a protective barrier against antibiotics and immune responses [2, 24, 27–29]. The uppermost layers are less densely packed, with cells exhibiting phenotypic heterogeneity, including persister cells that contribute to antibiotic resistance [25]. Advanced imaging techniques such as confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have shown the dynamic and complex nature of biofilm ultrastructure. The intricate architecture and ultrastructural complexity of bacterial biofilms underscore their role in chronic infections and their resilience against antimicrobial treatments. Understanding these structural nuances is critical for developing effective strategies to disrupt biofilm formation and enhance antibiotic efficacy [30]. The resistance mechanisms employed by bacteria within biofilms have garnered significant attention due to their role in persistent infections and their ability to circumvent traditional antimicrobial therapies. The development of biofilm-associated resistance involves a variety of mechanisms, including structural barriers, altered metabolic states, genetic adaptation, and intercellular communication. The molecular basis of biofilm resistance is complex, and ongoing research aims to elucidate the key factors involved in this phenomenon [1, 29].

The importance and mechanism of biofilms in antibiotic resistance

The formation of biofilms allows bacteria to survive in hostile environments, including under the stress of antibiotic treatment. This resistance mechanism is particularly significant in chronic infections and hospital settings, where biofilm-associated infections are prevalent [3]. One of the most concerning aspects of biofilms is their ability to contribute to antibiotic resistance. Several mechanisms have been identified by which biofilms enhance bacterial resistance to antibiotics by biofilms. Many antibiotics are less effective against biofilm-associated bacteria because they cannot reach the cells in the inner regions of the biofilm. Within biofilms, bacteria exist in a slower-growing or dormant state. Antibiotics, particularly those targeting cell wall synthesis or protein synthesis, are less effective against slow-growing or dormant cells. As a result, biofilm bacteria can survive even in the presence of therapeutic concentrations of antibiotics [31]. The “persisters,” a subset of bacterial cells within biofilms, exhibit a dormant phenotype that is highly resistant to antibiotics. The role of persister cells in biofilm-associated resistance is another critical aspect of the resistance phenotype. Persister cells are a small subpopulation of metabolically inactive or slow-growing cells that can survive exposure to high concentrations of antibiotics. These cells are thought to be present in biofilms as a result of stress-induced dormancy. The mechanisms underlying persister cell formation remain incompletely understood, but several studies suggest that changes in bacterial gene expression, including the upregulation of stress response pathways, are involved [32]. The ability of persister cells to endure antimicrobial treatments contributes to the recalcitrance of biofilm infections, as these cells can “wake up” and repopulate the biofilm once the antibiotic pressure is relieved. One of the most significant mechanisms is the upregulation of efflux pumps, which actively expel antibiotics from bacterial cells, reducing the intracellular concentration of the drug. Efflux pumps are often regulated by quorum sensing, a bacterial communication system that involves the release and detection of small signaling molecules. In biofilms, quorum sensing regulates the expression of genes responsible for efflux pump production, as well as other resistance factors, such as oxidative stress response proteins [16, 25, 33]. Quorum sensing also modulates the production of extracellular matrix components, further promoting biofilm formation and resistance to antimicrobial agents [34]. Biofilm-associated bacteria often express higher levels of efflux pumps, which can actively expel antibiotics from bacterial cells, thereby reducing their efficacy. Additionally, biofilms can increase the production of enzymes like β-lactamases that degrade antibiotics [35]. The physical and chemical structure of the biofilm plays a crucial role in protecting bacterial cells from antimicrobial agents. In addition to the physical barrier provided by the extracellular matrix, biofilm-forming bacteria are equipped with a range of molecular mechanisms that enhance their resistance to antimicrobial agents. Biofilms provide an environment that facilitates genetic exchange among microorganisms. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT), including the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes, is more frequent within biofilms. This can lead to the rapid spread of resistance traits among bacterial populations. The genetic diversity of bacteria within biofilms also plays a pivotal role in the development of resistance. Biofilm environments are conducive to horizontal gene transfer, allowing for the exchange of antibiotic resistance genes among bacterial cells. The dense, cooperative structure of biofilms facilitates the transfer of plasmids, transposons, and other mobile genetic elements, which may carry resistance determinants. This genetic exchange not only accelerates the acquisition of resistance but also results in the establishment of stable, resistant subpopulations within the biofilm [36]. Furthermore, biofilm formation itself has been shown to induce genetic mutations that contribute to the development of resistance, particularly in response to prolonged antibiotic exposure [37]. Several recent studies have focused on the role of the biofilm’s microenvironment in modulating antibiotic resistance. The physical characteristics of biofilms, including their thickness and density, influence the diffusion of antimicrobial agents and create microenvironments with reduced drug penetration. This limited access to antibiotics enhances the persistence of bacteria within biofilms, even in the presence of otherwise effective treatments [13, 31]. Moreover, biofilms in vivo are frequently exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of antibiotics, which may induce adaptive resistance mechanisms such as the activation of efflux pumps, DNA repair pathways, and changes in membrane permeability. These adaptive responses allow bacteria to survive under conditions that would otherwise be fatal [38]. Biofilm-associated infections are frequently encountered in clinical settings, particularly among patients with indwelling medical devices such as catheters, prosthetic joints, and cardiac valves. These abiotic surfaces facilitate microbial adhesion and subsequent biofilm development, contributing to persistent infections that exhibit a high degree of tolerance to conventional antimicrobial therapies. Key bacterial species implicated in these infections include Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus spp. Research about biofilm-targeting strategies has grown in recent years, aiming to develop treatments that can either prevent biofilm formation, disrupt established biofilms, as well as methods to inhibit the initial attachment of bacteria or block the signaling pathways that regulate biofilm formation (e.g., quorum sensing inhibitors) are under investigation. Enzymes that degrade components of the EPS matrix, such as DNases or polysaccharide-degrading enzymes, can enhance the effectiveness of antibiotics by allowing better penetration into the biofilm. Combining antibiotics with agents that disrupt biofilms or enhance antibiotic penetration is a promising strategy. This approach could reduce the likelihood of resistance development by targeting multiple aspects of biofilm-associated bacterial survival. Nanomaterials such as silver nanoparticles or nanostructured surfaces are being explored for their ability to disrupt biofilms and enhance antibiotic efficacy [2, 24, 27, 31]. Bacteriophages, viruses that infect and kill bacteria, are being investigated for their potential to target and disrupt biofilms without promoting antibiotic resistance [39–41]. The ability of bacteria within biofilms to resist antibiotic treatment, evade immune responses, and exchange resistance genes makes biofilm-associated infections particularly difficult to treat. Understanding the mechanisms underlying biofilm formation and resistance is essential for the development of more effective treatment strategies. Continued research into biofilm biology and innovative therapeutic approaches will be key in addressing the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance [25, 26, 28, 29, 42]. Biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance represents a complex and multifactorial challenge in both clinical and environmental contexts. Understanding the underlying mechanisms is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies [43]. Understanding the mechanisms of biofilm resistance has significant clinical implications, particularly for the treatment of chronic and recurrent infections. The recalcitrance of biofilm-associated bacteria to antibiotics necessitates the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting biofilm formation, enhancing drug penetration, or targeting specific resistance mechanisms. Recent advances have explored the use of enzymatic agents that degrade the extracellular matrix, as well as the development of compounds that inhibit quorum sensing or efflux pump activity [3, 38]. Additionally, combining traditional antibiotics with agents that disrupt biofilm structure or function may improve treatment outcomes and help overcome the challenges associated with biofilm-associated infections [15, 38].

CRISPR-Cas system

The CRISPR-Cas system is a revolutionary genetic tool that has reshaped the landscape of molecular biology and genetic engineering. Originally discovered in bacteria and archaea as an adaptive immune mechanism, CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) and its associated protein, Cas (CRISPR-associated proteins), have been repurposed for genome editing in diverse organisms. The CRISPR/Cas system roles in microbial defense involve storing segments of viral DNA in the form of CRISPR sequences and using these sequences to guide the Cas proteins to target and cleave foreign DNA during subsequent infections [44, 45]. The discovery of the programmable nature of CRISPR-Cas9, in particular, has enabled precise modifications to the genome of various organisms (Table 1), ushering in an era of unprecedented genetic manipulation [45]. The gene-editing system consists of two primary components: the Cas9 endonuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The Cas9 protein introduces double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the target DNA at a precise location defined by the gRNA. Once the DSB occurs, the bacterial repair mechanisms, such as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), attempt to repair the break, often resulting in gene knockouts or insertions that can disrupt biofilm-related processes. This precise targeting ability enables researchers to investigate the molecular mechanisms underpinning biofilm formation, maintenance, and eradication [46]. This precision allows researchers to cut and edit specific genes, making it an invaluable tool for genetic engineering and research. When the DNA is cut by Cas9, the cell attempts to repair the break through one of two pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is error-prone and often introduces small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, while HDR can be used for precise edits if a donor DNA template is provided [47]. This system has been harnessed not only for gene knockout experiments but also for more complex tasks, such as gene insertion, correction of mutations, and even gene activation or repression, depending on the modifications made to the Cas9 protein or the RNA guide [45]. The applications of CRISPR-Cas9 have revolutionized molecular biology and genetic research, including in fields such as agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. It has enabled the development of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) with enhanced traits, such as crops resistant to diseases or environmental stressors, as well as the potential for treating genetic diseases through gene therapy. In human medicine, CRISPR-Cas9 has shown promise for correcting genetic defects at the DNA level, with ongoing research into its potential for treating conditions like cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and muscular dystrophy [47]. However, ethical concerns, including the potential for off-target effects and germline editing, remain significant hurdles that need to be addressed as the technology continues to evolve [48]. In recent years, improvements to the CRISPR-Cas9 system have been made, including the development of more precise and efficient versions like CRISPR-Cas12 and CRISPR-Cas13, which target DNA and RNA, respectively. These advancements have expanded the utility of CRISPR beyond genome editing to other applications such as RNA editing and diagnostics, offering even more potential for biomedical and therapeutic innovations [49].

Table 1.

Representative CRISPR/Cas9-nanoparticle delivery systems with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, or biofilm-relevant applications

| Nanoparticle platform | CRISPR-Cas9 form | Target cells/organism | Target gene | Model | Application | Key findings | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric NPs | RNPs | Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | mecA | In vitro | Antibacterial (resistance) | Disrupted mecA gene; suppressed resistance to methicillin; restored antibiotic susceptibility | [50] |

| PEI Magnetic NPs | Plasmid DNA | HEK293 cells | TLR3 | In vitro | Immunomodulatory/host defense | Magnetic field-assisted CRISPR delivery enabled site-specific genome editing; potential application in modulating host defense genes against infection | [51] |

| Lipid-based NPs | Cas9 mRNA + sgRNA | BMDMs/C57BL/6 mice | NLRP3 | In vitro/in vivo | Anti-inflammatory/sepsis control | 70.2% NLRP3 knockout in vitro; modulated macrophage inflammation pathways; potentially reducing inflammatory damage in infections | [52] |

| Lipid-based NPs | Cas9 mRNA + sgRNA | HEK293 endothelial cells | ICAM-2 | In vivo | Biofilm penetration (vascular) | Endothelial targeting improved CRISPR delivery; may enhance vascular targeting of antimicrobials | [53] |

| Gold-lipid hybrid NPs | Plasmid DNA | Melanoma + Bacteria models | PLK-1 | In vitro/in vivo | Dual antibacterial/antitumor | Photothermal CRISPR system disrupted cell proliferation and potentially sensitized microenvironments to therapy | [54] |

| Lipidoid NPs | RNPs | HeLa-DsRed cells (biofilm test) | GFP reporter | In vivo | CRISPR delivery validation | Achieved ~ 70% knockout with low toxicity; relevant for CRISPR-based biosensors or delivery in biofilm-like environments | [55] |

| Polymeric NPs | Plasmid DNA | HFD-induced diabetic mice | NE (elastase) | In vivo | Inflammatory/metabolic infection | Knockout of neutrophil elastase reduced inflammation; improved insulin sensitivity, suggesting infection-linked inflammation modulation | [56] |

| Core–shell Fe/PEI NPs | Plasmid DNA | Porcine fibroblasts | H11 | In vitro | Gene delivery platform | 3.5 × improvement in delivery over lipofection; potential for CRISPR editing in antimicrobial peptide research | [57] |

| Polymeric NPs | Plasmid DNA | HEK293 + HeLa | GFP/iRFP | In vitro | CRISPR validation in cell platforms | 70% knockout; useful for building infection reporters or delivery optimization in biofilm models | [58] |

Mechanism of action of the CRISPR-Cas9 system

The sgRNA is engineered to be complementary to a target DNA sequence and directs Cas9 to that sequence for cleavage. The precise targeting is facilitated by the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) in the DNA sequence, which is required for Cas9 recognition (Fig. 1). The PAM sequence, typically “NGG” in Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, serves as a critical determinant for the binding of Cas9 to the target DNA and the subsequent DNA cleavage event [59]. Upon recognition of the PAM sequence, the Cas9 protein undergoes a conformational change, which allows it to unwind the DNA around the target sequence. The sgRNA then binds to the complementary DNA strand, forming a DNA-RNA hybrid structure. This binding is essential for the specificity of the system, as the Cas9 protein will only activate its nuclease activity when the guide RNA is fully paired with the target DNA [59, 60]. Cas9 has two distinct nuclease domains: The RuvC and HNH domains, which play complementary roles in cleaving the DNA. The HNH domain cleaves the strand of the DNA that is complementary to the guide RNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand, creating a double-strand break. This precise, staggered cleavage generates sticky ends that can be repaired through the cell's repair mechanisms, leading to either random mutations or targeted insertions, depending on the repair pathway activated [61].

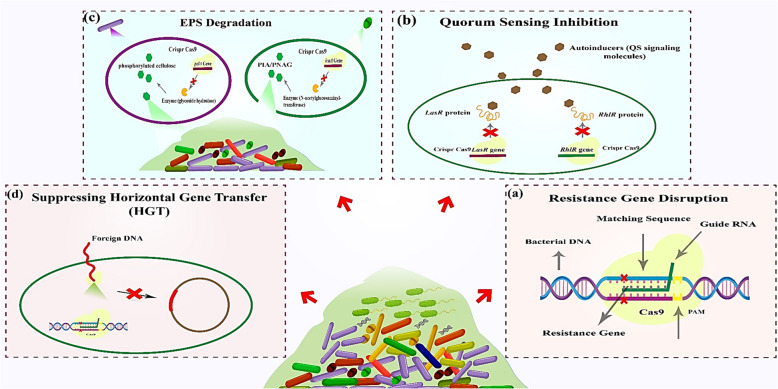

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9 in combating bacterial biofilms: a Resistance gene disruption: CRISPR-Cas9 targets antibiotic resistance genes via sequence-specific guide RNA (gRNA), inducing double-strand breaks at the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site. Cas9 cleavage disrupts resistance gene integrity, restoring bacterial susceptibility. b Quorum sensing inhibition: CRISPR-Cas9 disrupts quorum sensing (QS) by targeting transcriptional regulators (e.g., LuxR, BMIR proteins), blocking autoinducer-mediated signaling and biofilm coordination. c EPS degradation: CRISPR editing of genes encoding extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), such as phosphorylated cellulose (Pel polysaccharide), destabilizes the biofilm matrix, enhancing structural collapse. d Suppressing horizontal gene transfer: CRISPR-Cas systems degrade foreign DNA (e.g., plasmids) carrying resistance genes, preventing horizontal gene transfer (HGT) within biofilm communities

Once the DSB is induced, the cell responds with one of two major DNA repair mechanisms: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is the predominant repair pathway, particularly in mammalian cells. It is an error-prone mechanism that directly ligates the broken ends of DNA without a homologous template, often leading to insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. These indels can cause frameshift mutations, effectively disrupting the targeted gene’s function. Alternatively, HDR is a more accurate repair mechanism that utilizes a homologous template to repair the break. This template could be provided exogenously, such as a donor plasmid or a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN), and can be used for precise gene edits or insertions. HDR is less efficient in non-dividing cells, which makes it challenging for precise editing in certain tissues, but is still invaluable when precise gene editing is required [62]. The precise action of CRISPR-Cas9 in editing genomes also hinges on its specificity. A major limitation of the system is its propensity for off-target effects, where Cas9 induces DNA breaks at unintended genomic locations that have sequence homology to the target sequence. Off-target cleavage typically occurs when the sgRNA binds to a similar but non-identical sequence elsewhere in the genome, especially when the off-target sequence contains a PAM sequence [59, 62]. These off-target effects could lead to unwanted genetic mutations or disruptions in functional genes, which could have unintended consequences, particularly in therapeutic applications. To minimize such risks, several strategies have been developed to increase the specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. One of the most notable approaches involves the engineering of high-fidelity Cas9 variants that exhibit reduced off-target cleavage while maintaining editing efficiency. These include Cas9 variants such as eSpCas9, HypaCas9, and SpCas9-HF1, all of which have been shown to reduce off-target activity significantly without compromising the system’s on-target editing efficacy [60]. Additionally, research into alternative CRISPR-associated proteins, such as Cpf1 (now known as Cas12), has shown promise for improving target specificity. Cas12 has distinct features, such as a different PAM sequence requirement (“TTTN”), and an ability to generate staggered cuts, which may reduce off-target activity and expand the range of editable loci [63]. The applications of CRISPR-Cas9 extend beyond basic genome editing to therapeutic and biotechnological realms. The ability to induce precise gene modifications, correct genetic mutations, or knock out genes has profound implications for the treatment of genetic disorders, such as sickle cell anemia and Duchenne muscular dystrophy [64]. Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 enables functional genomics, allowing researchers to systematically study gene function by creating knockout or knock-in cell lines, animal models, and organoids. Despite its immense potential, challenges such as delivery mechanisms, off-target effects, and efficiency of HDR in non-dividing cells remain areas of active research [65]. Recent improvements in CRISPR technology, including advanced delivery techniques and the development of next-generation CRISPR-Cas systems, are addressing some of these limitations and will likely accelerate the therapeutic and industrial applications of genome editing [59].

The CRISPR-Cas system and biofilm-related antibacterial resistance

The CRISPR-Cas system has gained significant attention for its potential in antimicrobial strategies, particularly in targeting antibiotic-resistant bacterial populations within biofilms. One of the main reasons biofilm-associated bacteria exhibit increased antibiotic resistance is due to limited drug penetration, altered metabolic states, and horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which facilitates the spread of resistance determinants [7]. The CRISPR-Cas system plays a dual role in biofilm-related resistance: while it can function as a defense mechanism against phages and plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes, it also influences biofilm formation through regulatory pathways [17]. CRISPR-Cas9 technology, originally discovered as a bacterial immune system against viral infections, has rapidly evolved as a powerful tool for genome editing, with promising applications in combating antibiotic resistance. One of the promising applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in this field is its ability to specifically target and disrupt antibiotic resistance genes, thereby restoring bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. Recent studies have demonstrated the ability of CRISPR-Cas9 to target and remove resistance genes from the genomes of pathogenic bacteria. For example, one study successfully utilized CRISPR-Cas9 to cleave the mcr-1 gene, which confers resistance to colistin, in urgent need for novel antimicrobial Escherichia coli strains. This approach effectively restored the bacteria’s sensitivity to colistin, a last-resort antibiotic, showcasing CRISPR-Cas9’s potential to reverse antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [66, 67]. Additionally, CRISPR-Cas9 has been applied to target and eliminate plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes, such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes, in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, further proving its ability to reverse resistance mechanisms [68]. Moreover, CRISPR-Cas9 has been adapted for use in gene drives, a system that ensures the inheritance of specific genes in a population. Researchers have explored the use of CRISPR-based gene drives to target resistance genes across bacterial populations. This strategy has shown promise in preventing the spread of antibiotic resistance in clinical and environmental settings [69]. One of the main advantages of using CRISPR-Cas9 over traditional antibiotic therapies is its precision; while antibiotics indiscriminately kill both pathogenic and beneficial bacteria, CRISPR-Cas9 can specifically target resistance genes without affecting the surrounding microbial community, minimizing collateral damage to the microbiome [55, 59]. The widespread and clinical application of the CRISPR system still faces challenges, with the most significant challenge being the delivery of CRISPR complex components. Issues such as delivery efficiency, particularly in the context of human infections, and the potential for off-target effects need to be addressed. The design of safe and effective delivery systems, such as viral vectors or nanoparticles, is critical for successful clinical application [61, 62]. Additionally, there are concerns about the potential for resistance to CRISPR-Cas9 systems themselves, as bacteria may evolve mechanisms to resist CRISPR-mediated genome editing [70]. Despite these hurdles, the application of CRISPR-Cas9 systems represents a transformative approach in the fight against antibiotic resistance. Ongoing research and clinical trials are crucial to overcoming these challenges and unlocking the full potential of CRISPR-based therapies to combat resistant infections [71]. Studies have shown that certain CRISPR-Cas systems directly regulate biofilm formation. For example, Type I and Type II CRISPR-Cas systems can modulate quorum sensing (QS) pathways, which are critical for biofilm development. In some bacteria, the disruption of CRISPR-Cas components has been linked to enhanced biofilm formation, suggesting that CRISPR interference can downregulate genes associated with biofilm stability. Conversely, biofilm-forming bacteria often exhibit reduced CRISPR activity, allowing them to acquire foreign genetic material, including antibiotic resistance genes, via HGT [25, 66, 72].

CRISPR-based strategies for biofilm eradication

Because biofilm-associated resistance has created many challenges, researchers have explored CRISPR-based approaches to disrupt biofilms and re-sensitize bacteria to antibiotics. CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-Cas3 nucleases have been employed to selectively degrade antibiotic resistance genes in biofilm-embedded bacteria, leading to increased susceptibility to conventional antibiotics [44]. Additionally, engineered phage-delivered CRISPR systems can selectively lyse biofilm-forming pathogens by targeting essential survival genes. These strategies have shown promising results against clinically relevant pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus [33, 68, 73]. Recent advancements have also explored CRISPR-guided antimicrobials, wherein programmable CRISPR systems induce targeted double-stranded DNA breaks within resistance genes, effectively eliminating resistant subpopulations from biofilms. Additionally, the combination of CRISPR-based disruption with conventional antibiotics has demonstrated synergistic effects, significantly enhancing bacterial clearance [7, 49, 61].

Mechanisms of CRISPR/Cas9 editing in biofilm control

In the context of biofilm control, CRISPR/Cas9 can be used to manipulate several key genetic pathways that regulate biofilm formation. The CRISPR/Cas9 system is guided by RNA molecules to specific DNA sequences, often those that regulate the synthesis of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), which form the matrix of the biofilm. For example, in Staphylococcus aureus, the icaA gene encodes an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of PIA, a key component of the biofilm matrix. Disrupting icaA via CRISPR/Cas9 results in reduced biofilm formation and impaired bacterial adhesion, a crucial process for biofilm establishment [7, 17]. One of the central mechanisms by which biofilms are formed is quorum sensing (QS), a process by which bacteria communicate to regulate group behaviors such as biofilm formation, virulence, and antibiotic resistance. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the las and rhl QS systems are vital for biofilm development. These systems involve the production and detection of signaling molecules, which regulate the expression of genes involved in biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. CRISPR/Cas9 can be used to knock out key genes in these pathways, such as lasR, rhlR, and luxR, to prevent QS and biofilm formation. By targeting these genes, the system could effectively reduce biofilm biomass and make bacterial populations more susceptible to antibiotics [7, 17, 55, 59]. Another important target is the cyclic-di-GMP signaling pathway. Cyclic-di-GMP is a second messenger molecule that plays a critical role in the regulation of biofilm formation in many bacteria. High levels of cyclic-di-GMP promote biofilm formation, while low levels encourage planktonic growth. Genes like pelA, which encode enzymes involved in cyclic-di-GMP synthesis, are key targets for CRISPR/Cas9 editing. By knocking out or downregulating these genes, researchers have successfully reduced biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This approach can also be extended to other bacteria where cyclic-di-GMP is involved in biofilm regulation, such as Escherichia coli [47, 48, 67, 74, 75].

Engineering CRISPR/Cas9 for biofilm disruption

For the efficient application of CRISPR/Cas9 in biofilm-targeting strategies, the delivery of CRISPR components into biofilm-embedded bacteria presents a significant challenge. Biofilms act as physical barriers, and the dense EPS matrix often limits the penetration of genetic material, including CRISPR/Cas9 constructs. Various strategies have been explored to overcome this limitation. One approach is the use of nanoparticles or liposomes to deliver CRISPR components (Fig. 2). These carriers can penetrate biofilm matrices, facilitate the uptake of plasmid DNA or CRISPR/Cas9 complexes, and enhance gene editing efficacy [28, 29, 76]. Additionally, bacteriophage-mediated delivery has shown promise in overcoming delivery barriers. Engineered bacteriophages that carry CRISPR/Cas9 components can specifically target and infect bacterial cells within biofilms, thus delivering the gene-editing machinery directly to the desired location [69]. Phage-based CRISPR systems have been successfully used to edit genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms, offering a targeted and efficient means of biofilm disruption. Phage-based CRISPR delivery may also offer reduced cytotoxicity to surrounding host cells, making it an attractive strategy for clinical applications [9, 37, 77]. In addition to plasmid-based or phage-based delivery, some studies have explored electroporation and other physical methods to facilitate the uptake of CRISPR/Cas9 components in biofilm-forming bacteria. These techniques can increase the permeability of bacterial cell membranes, allowing the introduction of CRISPR plasmids or proteins into biofilm-associated bacteria [77, 78].

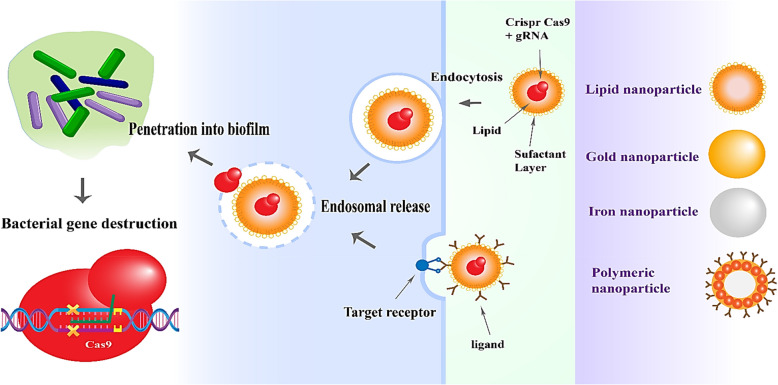

Fig. 2.

Engineered nanoparticle platform for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery: mechanisms and applications in biofilm eradication and resistance gene suppression. The figure illustrates multi-purpose nanoparticles vacillating between lipid-based polymeric nanoparticles, such as PLGA and chitosan, and inorganic nanoparticles, such as Au and iron oxide, all types of delivery systems for CRISPR-Cas9 into bacterial biofilms. Nanoparticles scatter across the extracellular polymeric matrix while being taken up by bacterial cells through the receptor-mediated or clathrin/caveolin-dependent endocytosis pathway [79]. Following uptake, the CRISPR-Cas9 RNPs are released via endosomal escape mechanisms [80], allowing for genome editing

Quorum sensing inhibition and biofilm disruption

Quorum sensing (QS) is a bacterial communication system that regulates biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. CRISPR-Cas9 has been employed to disrupt QS-regulated genes, such as luxS, lasI, and rhlR, leading to biofilm dispersal and increased bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials. Nanoparticle formulations enhance this strategy by enabling precise delivery and controlled release of CRISPR-Cas9 components within biofilm structures. Recent studies have highlighted the efficacy of NP-CRISPR systems in QS inhibition, effectively weakening biofilm resilience [25].

Direct eradication of biofilm-forming bacteria

Beyond targeting antibiotic resistance genes and QS pathways, CRISPR-Cas9 can be programmed to disrupt essential biofilm-associated genes. Genes involved in adhesion (fimH, bap) and EPS production (psl, pel, icaA) are prime targets for biofilm eradication [66, 68]. NP-based CRISPR systems allow targeted gene knockouts, resulting in structural destabilization and enhanced antimicrobial penetration. This strategy has shown significant promise in reducing biofilm biomass and restoring bacterial clearance by antibiotics and host immune defenses. Nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 delivery presents a revolutionary approach for tackling biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance. By ensuring precise targeting of resistance genes, quorum sensing pathways, and biofilm integrity, NP-CRISPR strategies hold great potential for clinical applications. However, challenges such as delivery efficiency, immune responses, and scalability need to be addressed for translational success. Future research should focus on optimizing nanoparticle formulations, enhancing bacterial specificity, and exploring combination therapies with existing antimicrobials. The integration of NP-CRISPR technology with other antimicrobial strategies may pave the way for next-generation biofilm control and infection management [8, 81].

Relationships between the CRISPR-Cas system and antibiotic resistance

The CRISPR-Cas system has shown a complex relationship with antibiotic resistance, as it not only serves as a defense against phage attacks but also influences the dynamics of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and the spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). The role of the CRISPR-Cas system in antibiotic resistance can be twofold. On one hand, it can limit the acquisition and dissemination of resistance genes through HGT. By cleaving the foreign plasmids or DNA that carry these resistance genes, CRISPR-Cas systems can act as a barrier to the spread of resistance within microbial populations [72]. This has been demonstrated in studies where bacteria with active CRISPR systems were less likely to acquire plasmids carrying ARGs compared to CRISPR-deficient strains [82]. On the other hand, some studies suggest that bacteria may develop resistance to the CRISPR-Cas system itself, allowing the persistence of antibiotic resistance. For example, mutations in the CRISPR sequences or the Cas proteins can result in the loss of immune function, facilitating the accumulation and spread of resistance genes. In some cases, bacteria have developed mechanisms to suppress CRISPR activity or acquire immunity to specific Cas proteins, which could allow the persistence of resistance genes even in the presence of CRISPR-mediated defense [83]. Moreover, CRISPR-Cas systems have been shown to influence the evolution of multidrug resistance in clinical isolates, where CRISPR interference could contribute to the selection of resistant strains by altering the bacterial genomic landscape [84]. CRISPR interference with mobile genetic elements carrying ARGs may also be influenced by bacterial population dynamics. In densely populated communities, the horizontal transfer of resistance genes can be a key factor in the spread of resistance. The CRISPR-Cas system's role in limiting or enhancing this transfer is context-dependent, varying based on the strain, environmental factors, and the specific type of CRISPR system present. For instance, Type I and Type III CRISPR systems, which primarily target RNA and DNA, may exert different selective pressures on the spread of resistance compared to the more widely studied Type II system, which is used in genome editing [72, 85]. Furthermore, the relationship between CRISPR-Cas systems and antibiotic resistance is not always direct. Other factors, such as the presence of specific bacteriophages or the dynamics of microbial communities, can modify the impact of CRISPR on antibiotic resistance. For example, phage therapy has been proposed as an alternative to antibiotics, where the CRISPR-Cas system could prevent bacterial adaptation to phages, but it may also interfere with the phage’s ability to deliver genetic material, including resistance traits, to bacterial hosts [86].

Applications of nanoparticles in antibiotic therapy

Nanoparticles (NPs) are increasingly explored for their potential in enhancing antibiotic therapy, primarily due to their unique physicochemical properties, such as high surface area, size-dependent behavior, and the ability to modify surface interactions. These features enable nanoparticles to overcome the challenges posed by conventional antibiotics, such as poor bioavailability, rapid clearance, and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The ability of nanoparticles to deliver drugs more effectively, enhance their stability, and offer targeted therapy has made them a promising tool in combating antibiotic-resistant infections [87, 88]. Nanoparticles, especially liposomes, micelles, dendrimers, and polymeric NPs, have shown promising applications as carriers for antibiotics. The high surface-to-volume ratio of NPs facilitates the encapsulation of hydrophobic antibiotics, thereby improving their solubility, stability, and bioavailability. Furthermore, targeted drug delivery is achieved by functionalizing NPs with ligands that selectively bind to bacterial cells, ensuring enhanced local concentrations of antibiotics at the site of infection [89].

Drug/gene delivery to combat bacterial infection

The mechanism of action of drug and gene delivery systems is essential to understand in order to optimize the therapeutic efficacy against bacterial infections. The fundamental goal of both drug and gene delivery is to selectively target bacterial cells or infected tissues, allowing for the efficient release of therapeutic agents at the site of infection while minimizing systemic toxicity. Several mechanisms are employed in the delivery of drugs and genes to combat bacterial infections, with the most prominent ones being passive targeting, active targeting, and stimuli-responsive release [90, 91].

Drug delivery mechanisms

Passive targeting

Passive targeting relies on the physicochemical properties of the drug delivery system and the biological environment. One of the most common strategies for passive targeting is the use of nanoparticles, which are designed to exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. The EPR effect occurs in the inflamed or infected tissues, where blood vessels become leaky, allowing nanoparticles to accumulate at higher concentrations. This mechanism is particularly useful for delivering antibiotics to sites of infection, such as abscesses or chronic wounds [92].

Active targeting

Active targeting involves the modification of the surface of drug carriers to enable recognition by specific bacterial cells or infected tissue. This can be achieved by functionalizing nanoparticles with ligands (such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers) that bind to specific bacterial surface markers. For example, liposomes or polymeric nanoparticles can be conjugated with antibodies against bacterial antigens like lipopolysaccharides on Gram-negative bacteria, allowing for targeted delivery of antibiotics [93]. Additionally, bacterial receptors such as pili or fimbriae can be exploited for targeting bacterial cells directly [92].

Controlled release and nanocarriers

Nanocarriers, such as liposomes, micelles, and dendrimers, can encapsulate drugs and control their release at the site of infection. These carriers often employ diffusion, degradation, or swelling mechanisms to release the drug over time. For example, a pH-sensitive polymeric carrier will release its contents in an acidic environment, which is typical of infected tissues. Additionally, some nanocarriers respond to the enzymatic activity in the bacterial cell wall or biofilms, ensuring that the antibiotic is released only when it reaches the targeted site [92].

Gene delivery mechanisms

Plasmid DNA delivery

One of the most straightforward gene delivery mechanisms involves the use of plasmid DNA, which is delivered directly into bacterial cells or host tissues to express antimicrobial peptides, enzymes, or other therapeutic proteins. This is typically achieved using viral vectors, such as adenoviruses or lentiviruses, which can deliver genes into the target cells. Alternatively, non-viral vectors such as cationic liposomes or nanoparticles can facilitate the uptake of plasmid DNA through endocytosis [94]. Upon internalization, the plasmid DNA is released into the cytoplasm, where it can be transcribed and translated into the desired therapeutic proteins [95].

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing

Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components, such as the Cas9 protein and guide RNA, is achieved using nanoparticles or viral vectors. These systems allow for precise and targeted gene editing, which can either knock out bacterial resistance genes or enhance the host immune response against the infection [96].

Bacteriophage-based gene delivery

In this approach, phages can be modified to deliver therapeutic genes directly to bacterial cells. The mechanism of action involves the bacteriophage attaching to specific receptors on bacterial cell walls, injecting its genetic material into the bacterium, and replicating inside the cell. This method can be used to deliver genes encoding antimicrobial peptides or enzymes that degrade bacterial cell walls, thus helping to combat infection. Furthermore, bacteriophage-derived systems can be used to disrupt bacterial biofilms, a common mechanism of antibiotic resistance [39, 77].

Stimuli-responsive gene delivery

Gene delivery can also be enhanced by incorporating stimuli-responsive carriers. These carriers respond to environmental changes, such as pH, temperature, or specific enzymes found in the infection site, which trigger the release of therapeutic genes. For example, pH-sensitive nanoparticles can release their cargo when exposed to the acidic conditions present in infected tissues, ensuring that the gene therapy is localized to the site of infection [97]. Such controlled release mechanisms are critical for minimizing side effects and improving therapeutic outcomes. Both drug and gene delivery mechanisms aim to improve the precision, efficacy, and safety of therapies used to combat bacterial infections. While drug delivery systems primarily focus on enhancing drug stability, bioavailability, and targeted delivery, gene delivery systems are focused on enhancing the host’s defense mechanisms or directly disrupting bacterial virulence. The integration of nanoparticles, CRISPR technologies, and bacteriophage-based systems holds great promise in overcoming the challenges posed by antibiotic resistance and improving the overall management of bacterial infections [55].

Enhancing antibiotic efficacy and overcoming resistance

NPs can enhance the efficacy of antibiotics, particularly against multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. They act as potent adjuvants, increasing bacterial membrane permeability and facilitating the uptake of antibiotics. Some NPs can also disrupt biofilms, a common feature of chronic infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Metal-based NPs, such as silver (Ag NPs), gold (Au NPs), and copper oxide (CuO NPs), possess intrinsic antimicrobial properties, which, when combined with antibiotics, exhibit synergistic effects that can overcome resistance mechanisms [98, 99]. Beyond their role in drug delivery, some nanoparticles possess direct antibacterial properties. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles interact with bacterial cells through mechanisms such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, disruption of bacterial cell walls, and interference with cellular components like proteins and DNA. For instance, silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) are known to release silver ions that damage bacterial cell membranes, leading to cell death. Similarly, copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) are effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria due to their ability to generate oxidative stress [100, 101]. One of the major challenges with conventional antibiotics is their systemic toxicity and side effects. NPs help reduce these effects by providing localized drug release, which limits the exposure of non-target tissues to high drug concentrations. Additionally [102] or targeting moieties can further minimize toxicity while enhancing therapeutic outcomes. The integration of nanoparticles with antibiotics in combination therapies has proven to be a powerful strategy. Multifunctional nanoparticles can simultaneously deliver antibiotics and other therapeutic agents, such as anti-inflammatory or anticancer drugs, for a more comprehensive treatment approach. These NPs can also be engineered to respond to external stimuli like pH, temperature, or light, allowing for controlled and site-specific drug release [103]. Despite the promising applications of nanoparticles in antibiotic therapy, several challenges remain. Issues such as potential toxicity, immune system interactions, and the large-scale production of nanoparticles need to be addressed. Furthermore, the long-term effects of NPs, particularly in terms of environmental and human health, require thorough investigation. Continued advancements in nanomaterial design, biocompatibility, and regulatory approval are essential for the clinical translation of nanoparticle-based antibiotic therapies [104].

Nanoparticles: carrier of the CRISPR-Cas system

Traditional antimicrobial strategies often fail against biofilms, necessitating alternative approaches. CRISPR-Cas9, a genome-editing tool capable of precise genetic modifications, has emerged as a promising strategy for targeting biofilm-associated resistance genes. However, efficient delivery of CRISPR components into biofilms remains a major hurdle. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems offer a viable solution by enhancing CRISPR-Cas9 stability, biofilm penetration, and targeted bacterial eradication [9]. Nanoparticles have emerged as promising carriers for the CRISPR-Cas system, addressing the challenges of efficient gene editing by improving the delivery of CRISPR components to target cells, tissues, or organs [96]. The CRISPR-Cas system, especially the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool, requires efficient delivery to ensure successful genetic modification (Fig. 2). Nanoparticles, due to their unique physical and chemical properties such as high surface-area-to-volume ratio and ability to encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances, provide an effective solution [7]. Different types of nanoparticles have been explored for CRISPR delivery (Table 2). Liposomes, lipid-based nanoparticles, are among the most commonly used because of their ability to fuse with cell membranes, facilitating the transport of CRISPR components such as Cas9 proteins and guide RNAs (gRNAs) [105]. Polymeric nanoparticles, created from synthetic or natural polymers, have also shown promise due to their capacity to package CRISPR components and control release, protecting the system from degradation [6]. Inorganic nanoparticles, including gold, silica, and iron oxide nanoparticles, offer additional benefits due to their stability and ability to be functionalized for gene delivery or imaging purposes. Exosome-mimetic nanoparticles, which are modeled after naturally occurring exosomes, also present a unique approach to delivering CRISPR systems, capitalizing on their inherent ability to interact with cells [88, 92, 99, 105]. The mechanisms of nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR-Cas delivery involve the uptake of nanoparticles through cellular pathways such as endocytosis, which can occur via clathrin-mediated or caveolin-mediated routes. Once inside the cell, the nanoparticles must release the CRISPR components into the cytoplasm, often overcoming barriers such as the endosomal membrane. Once the Cas9 protein reaches the nucleus, it induces double-strand breaks in the target DNA, leading to gene knockout or insertion via the cell's DNA repair machinery [106, 107]. Various nanoparticles (NPs) have been designed to enhance CRISPR-Cas9 delivery for biofilm eradication. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) provide high transfection efficiency and protect CRISPR components from enzymatic degradation. Polymeric nanoparticles, such as poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and chitosan-based NPs, offer controlled release and biofilm-targeting capabilities. Inorganic nanoparticles, including gold and silica-based NPs, enhance stability and can be functionalized for specific targeting. Additionally, cell-penetrating peptide-modified NPs facilitate uptake by bacterial cells and biofilm penetration [2, 108]. While CRISPR-Cas9 systems are often scrutinized for their off-target gene-editing effects, the nanoparticle carriers themselves introduce additional risks related to delivery specificity. In particular, cationic nanoparticles, which are frequently employed for complexing negatively charged nucleic acids, exhibit a high affinity for anionic host cell membranes. This property can result in nonspecific cellular uptake, leading to off-target delivery in mammalian cells and reduced therapeutic precision [109]. Surface modifications, such as PEGylation or zwitterionic coatings, have been shown to reduce unintended interactions and improve biocompatibility, but optimization must be tailored to the specific delivery context [110]. However, the nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR delivery systems have several challenges. Toxicity is a concern, as some nanoparticles can damage cells or organs. Furthermore, not all cells take up nanoparticles efficiently, which can hinder the overall delivery efficacy. Despite advances, off-target gene editing remains a problem for CRISPR/Cas9 system, although improved targeting strategies with nanoparticles are being explored to enhance precision. Additionally, immune responses against synthetic nanoparticles can limit their therapeutic potential [5, 6, 92]. Another critical consideration is the bioaccumulation potential of inorganic nanoparticles, particularly metal-based carriers such as gold (AuNPs) or silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). These particles, while effective in enhancing CRISPR delivery and biofilm penetration, are known to accumulate in the liver, spleen, and other reticuloendothelial tissues, potentially triggering long-term toxicity or immune responses [111]. Chronic exposure studies in animal models have shown that even low-dose accumulation of metal nanoparticles may alter hepatic function and induce oxidative stress [112]. Thus, comprehensive in vivo biosafety assessments are essential before clinical translation of nanoparticle-assisted CRISPR therapeutics. Recent developments focus on optimizing the size, charge, and surface functionalization of nanoparticles to improve CRISPR delivery [96]. Surface functionalization, using targeting ligands such as antibodies or peptides, helps guide nanoparticles to specific cell types and reduces unintended interactions. Moreover, stimuli-responsive nanoparticles that respond to environmental cues such as pH or temperature offer controlled release of CRISPR components at the desired target site [88, 91, 96, 105]. The efficacy of CRISPR–nanoparticle systems in treating biofilm-associated infections depends not only on the engineering of advanced nanocarriers but also on a nuanced understanding of the microbiological microenvironment. Mature biofilms exhibit localized acidic conditions (pH 5.0–6.5) due to anaerobic bacterial metabolism, which provides a unique physicochemical cue for targeted drug release. pH-responsive nanoparticles, typically constructed from acid-labile linkers or protonatable polymers (e.g., poly(histidine), poly(β-amino esters)), are designed to remain stable at physiological pH but undergo destabilization or payload release in acidic niches [113]. This allows CRISPR-Cas cargos to be released precisely within the biofilm matrix, minimizing premature degradation and maximizing localized gene editing. For example, Tu et al. (2020) demonstrated that acid-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles could effectively release CRISPR/Cas9 payloads in acidic tumor microenvironments, a strategy directly translatable to acidic biofilm cores [114]. Such interdisciplinary integration of material science and microbiological insight is essential for achieving spatially controlled delivery and enhancing therapeutic specificity. The synergistic effect between CRISPR/Cas9 and nanoparticle carriers arises from the complementary strengths of both systems, particularly in overcoming biofilm-associated delivery barriers. Cationic or surface-functionalized nanoparticles can disrupt the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix through electrostatic interaction or enzymatic co-loading, thereby improving the penetration of CRISPR components into deeper biofilm layers [115]. Additionally, ligand-modified nanoparticles, such as those functionalized with bacterium-specific antibodies or antimicrobial peptides, enhance targeting specificity, reducing off-target effects and increasing CRISPR localization at infection sites [114]. Moreover, pH-responsive or redox-responsive nanocarriers are designed to release CRISPR cargos selectively within acidic or oxidative microenvironments typical of mature biofilms, ensuring spatially controlled gene editing [113]. In some designs, nanoparticles act as co-delivery platforms, carrying both CRISPR constructs and traditional antibiotics or EPS-degrading enzymes, achieving a multi-pronged disruption of biofilm defenses and promoting synergistic bacterial clearance [116]. Nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR-Cas delivery has broad applications. Gene therapy has the potential to treat genetic disorders by enabling precise genetic modifications in somatic cells. In cancer therapy, CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to modify immune cells, such as T cells, to enhance their ability to target cancer cells. Furthermore, agricultural biotechnology benefits from CRISPR technology for crop modification, with nanoparticles improving the delivery of CRISPR systems into plant cells to generate traits such as disease resistance or increased yield [107]. Recent studies have emphasized the need for safer, more efficient nanoparticle formulations. Innovations in nanoparticle design, including biocompatible materials, targeted delivery, and responsive systems, are paving the way for the broader application of CRISPR-Cas9 in clinical and agricultural settings [117, 118].

Table 2.

Integrated classification and comparative analysis of CRISPR-Cas system subtypes with respect to antimicrobial mechanisms, nanoparticle delivery compatibility, and translational potential

| Class | Type | Sub-type | Description | Target | Effector | CRISPR Protein | PAM/PFS | Associated type-subtype | Function | Mechanism of antimicrobial action | NP delivery compatibility | Translational readiness | Ethical/regulatory note | Application potential | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Type I | A | Multi-subunit crRNA-effector complex | dsDNA | Cascade |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

- | I, II, III-A, III-B, IV, possibly VI | DNA Nuclease and helicase activity | Cas3 degrades DNA unidirectionally after Cascade complex binding; enables"genome shredding"of resistance plasmids | Limited due to large complex size (multi-protein); needs innovative nano-encapsulation | In vitro efficacy confirmed; no in vivo or clinical delivery reported | DNA destruction is irreversible; biosecurity and containment are concerns | Multi-subunit system for processive DNA degradation. Experimentally explored to remove resistance plasmids and disrupt essential bacterial genes in persistent infections. Potential use in anti-biofilm strategies via genome shredding | [119–122] |

| B | Cascade |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

[119–122] | ||||||||||||

| C | Cascade |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 5 Cas 6 |

[119–122] | ||||||||||||

| C variant | Cascade |

Cas 5 Cas 6 Cas3 |

[119–122] | ||||||||||||

| D | Hybrid features of Type I and III |

Cas 1 Cas 6 Cas 3 |

[119, 121–123] | ||||||||||||

| E | Cascade |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

[119, 121, 122, 124] | ||||||||||||

| F | Csy-complex |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

[119, 121, 122] | ||||||||||||

| F variant 1 | Csy-complex |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

[119, 121, 122] | ||||||||||||

| F variant 2 | Csy-complex |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

[119, 121, 122] | ||||||||||||

| U | Cascade |

Cas 1 Cas 3 Cas 6 |

[119, 121, 122] | ||||||||||||

| Type III | A | Multi-subunit crRNA-effector complex | ssRNA | Csm complex |

Cas 2 Cas 6 Cas 8 Cas 10 |

I, II, III-A, III-B, V, some VI |

RNA Nuclease (Cleaving) |

Dual targeting of DNA and RNA; suitable for adaptive multi-pathway suppression of resistance and virulence | Complex structure limits delivery; still not validated in NP systems | Experimental phase; theoretical antimicrobial utility | Dual-action raises complexity in predicting off-targets and safety | Dual-action targeting of DNA and RNA makes it promising for managing complex infections involving horizontal gene transfer or mobile elements. May be valuable for real-time bacterial control but requires further optimization for nanocarrier compatibility | [119, 120, 122, 125, 126] | ||

| A variant | Csm complex |

Cas 2 Cas 6 Cas 8 Cas 10 |

[119, 120, 122, 126] | ||||||||||||

| B | Cmr complex |

Cas 2 Cas 6 Cas 8 Cas 10 |

[119, 120, 122, 126] | ||||||||||||

| B variant | Cascade |

Cas 2 Cas 6 Cas 8 Cas 10 |

[119, 120, 122, 126] | ||||||||||||

| C | Cascade |

Cas 2 Cas 6 Cas 8 Cas 10 |

[119, 120, 122, 126] | ||||||||||||

| D | Cascade |

Cas 2 Cas 6 Cas 8 Cas 10 |

[119, 120, 122, 126] | ||||||||||||

| Type IV | A | Multi-subunit crRNA-effector complex | dsDNA | Cascade |

Cas 3 Csf1(Cas8) |

I | Unknown/putative interference role (under investigation) | Suspected to restrict plasmid transfer and horizontal gene resistance spread | Not studied yet; lack of effector characterization limits formulation | Conceptual only; no in vitro or in vivo validations | No known risks; field underexplored | Poorly characterized; possibly involved in plasmid interference and restriction of mobile genetic elements. Could be useful for removing resistance plasmids in the future. Clinical applications remain speculative due to lack of adaptation machinery | [119, 120, 127–130] | ||

| A variant | Cascade |

Cas 3 Csf1(Cas8) |

|||||||||||||

| B | Cascade | Csf1(Cas8) | [119, 120, 127–130] | ||||||||||||

| Class 2 | Type II | A | Single-subunit crRNA-effector module (Cas9) | dsDNA | SpCas9 |

Cas 5 Cas 9 |

NGG SpCas9 | Type I, I |

Ribonuclease responsible for converting pre-crRNA to mature crRNA (Cleaving) |

Creates dsDNA breaks in resistance genes (e.g., mecA, blaNDM-1), blocking replication or plasmid stability | Highly compatible with lipid-based NPs, polymeric NPs, and exosomes. Cas9 protein or mRNA can be co-packaged with sgRNA | Currently in preclinical and early-phase human trials for antimicrobial and genetic diseases | Risk of off-target editing and immunogenicity. Regulatory guidelines under development for microbial gene-editing therapies | Precise DNA editing enables knockout of resistance genes (e.g., mecA, blaNDM-1) and disruption of biofilm-associated loci (e.g., icaA). Widely used in antimicrobial gene targeting and restoration of antibiotic susceptibility in drug-resistant bacteria. Compatible with diverse NP carriers for targeted delivery | [119, 131–136] |

| A variant | dsDNA | SaCas9 |

Cas 5 Cas 9 |

NNGRRT SaCas9 | Type I, I |

Ribonuclease responsible for converting pre-crRNA to mature crRNA (Cleaving) |

[131–136] | ||||||||

| B | dsDNA/ssRNA | FnCas9 |

Cas 6 Cas 9 |

NGG FnCas9 | Most type IIIB and type I |

Pre-crRNA is converted to mature crRNA by ribonuclease (Cleaving) |

[119, 131–135] | ||||||||

| C | dsDNA | NmCas9 |

Cas 7 Cas 9 |

NNNNGATT NmCas9 | I, III, IV |

It binds with crRNA and comprises of an RNA recognition motif (Cleaving) |

[119, 132–135] | ||||||||

| Type V | A | Single-subunit crRNA-effector module (Cas12) | dsDNA |

Cas12a (Cpf1) RuvC + Nuc domain |

Cas 8 Cas 12 Cpf1 |

50 AT-rich PAM TTTV | Most type I |

It forms effector complex large subunit in type I (Cleaving with cpf1) |

Cuts target DNA and triggers collateral ssDNA cleavage, enabling broader bacterial genome targeting and biofilm matrix degradation | Small size and self-processing capability make it ideal for lipid and polymeric NP encapsulation | Used in diagnostics (DETECTR), preclinical therapeutic designs underway | Lower immunogenicity; collateral activity may affect safety. Monitoring required in clinical translation | Offers gene editing with collateral cleavage potential, allowing both gene disruption and DNA degradation. Its self-processing ability simplifies NP delivery design. Applied in biofilm removal, bacterial genome disruption, and CRISPR-based diagnostics | [132, 137–142] | |

| B |

Cas12b (C2c1) RuvC |

Cas 9 Cas 12 Cpf1 |

50 AT-rich PAM TTTV | II only |

DNA nuclease (Cleaving with cpf1) |

[132, 137–143] | |||||||||

| C |

Cas12c (C2c3) RuvC |

Cas 10 Cas 12 Cpf1 |

50 AT-rich PAM TTTV | Some type I, most type III |

It forms effector complex large subunit in type III (Cleaving with cpf1) |

[132, 137–143] | |||||||||

| Type VI | A | Single-subunit crRNA-effector module (Cas13) | ssRNA | Cas13a (C2c2) |

Cas 12 (cpf1) Cas 13 |

30 PFS: non-G |

V | crRNA sorting, DNA nuclease | Degrades target RNA (e.g., resistance or virulence mRNAs), blocking protein synthesis; collateral RNA degradation in pathogens | Ideal for transient therapies; loaded as RNP or mRNA into lipid/polymer/hydrogel NPs | SHERLOCK-based diagnostics approved under EUA by FDA; therapeutic uses under study | Considered safer than Cas9 due to RNA-only targeting; potential for off-pathway RNA collateral cleavage | Targets bacterial or viral RNA, allowing suppression of gene expression without altering DNA. Promising for transient gene control in pathogens and CRISPR-based antimicrobials or diagnostics (e.g., SHERLOCK). Suitable for resistant infections involving RNA regulation | [132, 144–149] | |

| B-1 | Cas13b (C2c4) | Cas 13 (C2c2) |

50 PFS: non-C; 30 PFS:NAN/NNA |

VI | crRNA sorting, RNA nuclease | [145–151] | |||||||||

| B-2 | Cas13b (C2c4) | Cas 13 (C2c2) |

50 PFS: non-C; 30 PFS:NAN/NNA |

crRNA sorting, RNA nuclease | [146–151] | ||||||||||

| C | Cas13c (C2c7) |

Csm, Cmr Cas 13 |

- | III | Nucleases for single-stranded DNA and RNA | [144, 146–150, 152, 153] | |||||||||

| D | Cas13d |

RNase III Cas 13 |

- | II | tracrRNA is processed, and crRNA maturation is aided by this system | [146–150, 154] |

Future directions and challenges