Abstract

Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) sp. strain NGR234 contains three replicons, the smallest of which (pNGR234a) carries most symbiotic genes, including those required for nodulation and lipo-chito-oligosaccharide (Nod factor) biosynthesis. Activation of nod gene expression depends on plant-derived flavonoids, NodD transcriptional activators, and nod box promoter elements. Nod boxes NB6 and NB7 delimit six different types of genes, one of which (fixF) is essential for the formation of effective nodules on Vigna unguiculata. In vegetative culture, wild-type NGR234 produces a distinct, flavonoid-inducible lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that is not produced by the mutant (NGRΩfixF); this LPS is also found in nitrogen-fixing bacteroids isolated from V. unguiculata infected with NGR234. Electron microscopy showed that peribacteroid membrane formation is perturbed in nodule cells infected by the fixF mutant. LPSs were purified from free-living NGR234 cultured in the presence of apigenin. Structural analyses showed that the polysaccharide portions of these LPSs are specialized, rhamnose-containing O antigens attached to a modified core-lipid A carrier. The primary sequence of the O antigen is [-3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,2)-α-l-Rhap-(1-]n, and the LPS core region lacks the acidic sugars commonly associated with the antigenic outer core of LPS from noninduced cells. This rhamnan O antigen, which is absent from noninduced cells, has the same primary sequence as the A-band O antigen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, except that it is composed of l-rhamnose rather than the d-rhamnose characteristic of the latter. It is noteworthy that A-band LPS is selectively maintained on the P. aeruginosa cell surface during chronic cystic fibrosis lung infection, where it is associated with an increased duration of infection.

Rhizobium spp. are unique soil bacteria that have found an ecological niche within cortical cells of legume roots. Rhizobia infect highly organized root nodules, where they reduce atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia, which is then exported to the plant cells in the form of amides or ureides. Nodulation (nod) genes control the biosynthesis of lipo-chito-oligosaccharides (Nod factors) that are required for nodule initiation (6, 40). Genes required for the conversion of nitrogen into ammonia can be divided into two classes: the nif genes, which encode nitrogenase (22, 54), and the fix genes, which are involved in electron transport and membrane synthesis, etc. fix genes have many and varied functions (13, 45).

Nineteen nod boxes (conserved cis-acting regulatory sequences located in the 5′-end-flanking region of nodD-regulated, flavonoid-inducible genes) are present on the symbiotic plasmid pNGR234a of the broad-host-range Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (17, 28). Knockout mutation of the open reading frame that is 800 bp downstream of NB6 (17) provokes a Nod+ Fix− phenotype on Vigna unguiculata that results from nodules with defective peribacteroid membranes. Preliminary observations suggested that the mutant is unable to synthesize a polysaccharide component, shown here to be an O-antigen polysaccharide, that is a prominent product of apigenin-induced vegetative cells and bacteroids induced by the wild-type strain (16, 24).

Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) are major structural and antigenic components of the rhizobial outer membrane (9, 26, 41, 51). Their normal expression and structures are essential for successful symbiotic infection (8, 15, 26, 31, 33, 34, 49, 58). In the present study, we show that the flavonoid-inducible polysaccharide is a rhamnan O antigen, covalently linked to a structurally modified core oligosaccharide lipid A (thus, an LPS). Isolation and analysis of this unique O antigen shows that it consists of a trisaccharide repeat of l-rhamnose, having the same primary sequence as the A-band O antigen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth and manipulation.

Escherichia coli and Rhizobium strains, along with their relevant characteristics, are listed in Table 1. Microbiological techniques used are described in reference 29. Analysis of DNA, cloning, and sequencing procedures have been described previously (17, 46, 47). To construct NGRΩfixF, the 3.4-kb HindIII fragment of pNG77 was cloned into the HindIII site of pRK7813E/B (Table 1). Then, an Spr omega cassette was inserted into the unique EcoRI site of p3.4H. Mobilization of pΩ3.4H into NGR234 using pRK2013 as a helper plasmid, followed by forcing recombination between pNGR234a and pΩ3.4H (with the incompatible plasmid R751-pMG2), yielded NGRΩfixF. Southern blotting was used to check that the omega cassette was correctly inserted into fixF. Furthermore, conjugation of either pNG77 or p3.4H into NGRΩfixF restored the wild-type phenotype. Bacteroids were isolated from V. unguiculata nodules using the technique described in reference 50.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Rhizobium | ||

| NGR234 | Broad-host-range Rhizobium strain isolated from Lablab purpureus nodules, Rifr | 29, 44 |

| NGRΔnodABC | NGR234 derivative, NodABC− Nod− Rifr Spr | 43 |

| NGRΩfixF | NGR234 derivative containing an Ω cassette inserted into the EcoRI site of fixF, Rifr Spr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| p3.4H | 3.4-kb HindIII fragment of pNG77 cloned into the HindIII site of pRK7813E/B, Tcr | This work |

| pΩ3.4H | p3.4H with an Ω cassette inserted into the unique EcoRI site of fixF, Spr Tcr | This work |

| pNG77 | 32.4-kb clone from a cosmid library of NGR234 in pRK7813, Tcr | 56 |

| pRK2013 | Tra+ helper plasmid for mobilization, Kmr | 12 |

| pRK7813 | Broad-host-range Inc. P1 cosmid, Tcr | 25 |

| pRK7813E/B | pRK7813 derivative with an EcoRI-BamHI deletion in the polylinker, Tcr | This work |

Plant assays.

Seeds of Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. cv. Red Caloona were purchased from Rawlings Seeds (44). Nodulation ability was assayed in modified Magenta jars (29). At harvest, the nodules were sterilized, rolled on tryptone-yeast agar (to check for surface contamination), and cut in half. A small portion of the inner bacteroidal tissue was removed from one half and streaked out on triptone-yeast agar, while the other half was used for light and electron microscopy (59).

PAGE.

Aliquots (2 to 5 μg) of bacterial extracts were analyzed by deoxycholic acid-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) using 18% acrylamide; the gels were stained sequentially with alcian blue and silver (49), as well as directly with silver (to visualize LPS). The alcian blue prestain is necessary for detection of the acidic capsular polysaccharides (K antigens) (10, 48).

LPS preparation.

Pelleted cells from 5 liters of 10−6 M apigenin-induced or noninduced cultures (raised to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.9 in RMM [7]) were extracted using a modified hot-phenol-water method. The resulting water phases were combined, dialyzed, and freeze-dried, and the rhamnose-containing LPSs purified by sequential size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on superfine Sephadex G150 under disassociative conditions (0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, pH 9.25). Aliquots of the fractions (2 ml) were assayed colorimetrically for 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid (Kdo) by the thiobarbituric acid assay (57), for uronic acid using the hydroxybiphenyl assay (3), and for neutral sugars using the anthrone procedure (60). The fractions were pooled, dialyzed against water, and freeze-dried. SEC using a Superose 12 column (Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) under associative conditions (50 mM ammonium formate, pH 5, 0.4 ml min−1), followed by passage through a Dionex BioLC (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to achieve final purification of the LPS. The refractive index of the eluant was monitored using a RID-10A detector (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). Pooled fractions were freeze-dried several times to remove the formate.

Glycosyl analyses.

Glycosyl residue compositions were determined by gas-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of the trimethylsilyl (TMS) methylglycoside derivatives (60), using a 30-m DB-1 fused silica column (J&W Scientific, Folsom, Calif.) on a 5890A GC-MS (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Inositol was used as an internal standard, and retention times were compared to authentic standards. Glycosyl linkage analysis was determined by per-O-methylation (Hakomori method) and GC-MS analysis of the partially methylated alditol acetates (60), using a 30-m DB-1 column. The enantiomeric configurations of the glycosyl residues were determined by GC-MS analysis of the TMS (+)-sec-butyl glycoside derivatives of the carbohydrate components and authentic standards (18), including l-(+)-Rha, d-(+)-GlcNAc, and d-(+)-GalNAc.

NMR analyses.

1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses were performed on a Brüker AM 250 spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) and a Varian 500-MHz spectrometer (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). Samples were dissolved in D2O, and after allowing for extensive exchange of deuterium, the spectra were obtained at 316 degrees Kelvin (316 K). Chemical shifts were referenced to acetone. 1H-1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY) (42), total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) (2, 5), and nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) (30) data were collected in phase-sensitive modes. Low-power presaturation was applied to the residual HDO signal. Typically, homonuclear data sets were collected with 512 times 2,048 complex data points, and 16 scans/increment. Acquisition times were 0.3 s (t2) and 0.04 s (t1). The TOCSY pulse program contained a 60-ms MLEV-17 mixing sequence, and the NOESY mixing time was 150 ms. Carbon-proton correlations were made using gradient-selected heteronuclear single-quantum-coherence spectroscopy (HSQC) (4, 11), acquired with 256 times 1,024 complex points and 32 scans/increment. Heteronuclear multiple-bond-coherence spectroscopy (HMBC) and HSQC-TOCSY spectra were also required, due to the overlap of proton signals. The HMBC spectrum was acquired with 366 × 1,024 complex data points and 96 scans/increment. Acquisition times were 0.3 s (t2) and 0.007 s (t1).

RESULTS

Involvement of flavonoids and nod box NB6 in the expression of fixF.

Nod boxes NB6 and NB7 delimit six different genes that encode NoeE, a Nod factor-specific sulfyrl transferase (23), an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter system, an ion transporter, an epimerase, a glycosyl transferase, and FixF (17). nod box::lacZ fusions clearly demonstrate that the activity of NB6 is dependent on NodD1 and flavonoids (28). FixF shares 25% identity and 50% similarity with KpsS of E. coli K1 over 220 of its 402 amino acids as well as 29% identity (43% similarity) to RkpJ of Rhizobium meliloti. Both are involved in the production of the acidic capsular polysaccharides (K antigens) (27, 37).

A knockout mutant (NGRΩfixF) was constructed (see Materials and Methods) that is Nod+ Fix− on Calopogonium caeruleum, Macroptilium atropurpureum, and V. unguiculata (data not shown). Light and electron microscopic observations of V. unguiculata plants inoculated with NGRΩfixF showed that the number of bacteroid-containing cells was drastically reduced (Fig. 1B and C). Furthermore, the cytoplasm of the cortical cells in the nodules was degraded and ramification of the peri-bacteroid membrane was much less pronounced (Fig. 1D and E). Similar observations were made with the related legume M. atropurpureum (B. Relić and C.-H. Wong, unpublished). In other words, FixF seems to be required for peri-bacteroid membrane formation.

FIG. 1.

A, photograph of Vigna unguiculata plants growing in Magenta jars. Left to right: uninoculated, inoculated with the NGRΩfixF mutant, and inoculated with wild-type Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. B and C, light micrographs (magnification, ×100) of V. unguiculata nodules induced by NGR234 (B) and the Fix− derivative NGRΩfixF (C). D and E, electron micrographs (magnification, ×4,500 and 10,000, respectively) of portions of V. unguiculata nodules induced by wild-type NGR234 (D) and the Fix− mutant (E). Abbreviations: b, bacteroid; cw, cell wall; cc, cortical cell; vb, vascular bundle.

Does the absence of FixF provoke a hypersensitive response?

To test whether the Fix− phenotype is due to plant defense responses, complementation experiments in which V. unguiculata was inoculated with NGRΩfixF and NGRΔnodABC were performed. As the nodABC mutant is unable to produce Nod factors and is therefore Nod− on all plants, nitrogen-fixing nodules can form only if the fixF mutant produces sufficient Nod factors to permit NGRΔnodABC to enter roots and form nodules. Indeed, most of the nodules were occupied by NGRΔnodABC, but some also contained NGRΩfixF (data not shown). The presence of nitrogen-fixing nodules showed that plant flavonoids induced the nod genes of the fixF mutant, resulting in the production of Nod factors. In turn, these Nod factors caused root hair curling and nodule induction on the plant, allowing NGRΔnodABC to enter the roots (46, 47). Most probably this would not have occurred if NGRΩfixF had provoked a negative response, such as hypersensitivity. Of course, it is also possible that the wild-type surface of the Nod factor-minus mutant may have suppressed plant defense responses induced by the truncated surface of the fixF mutant during coinoculation. Unfortunately, there is no easy way of ruling out this possibility, but it seems unlikely that the fixF mutant triggers a plant defense response during the early stages of infection. Furthermore, the inability of the fixF mutant to fix nitrogen is not linked to deficiencies in Nod factor production. This was shown by purifying the Nod factors produced by NGRΩfixF and analyzing them by fast atom bombardment-MS, where they were shown to be identical to those produced by the wild-type strain (data not shown).

FixF is inducible and involved in LPS synthesis.

As fixF is downstream of a functional nod box and has homology to genes involved in LPS biogenesis, it seemed possible that the structure of the bacterial cell wall might be modulated by flavonoids. Consequently, crude cell wall extracts were prepared from cultured induced and noninduced bacteria. The aqueous phases of phenol-water extracts were separated on 18% deoxycholate (DOC)-PAGE gels and stained with either alcian blue/silver to detect the acidic, Kdo-rich K antigens or directly with silver stain (no alcian blue pretreatment), a procedure which detects only LPSs without revealing K antigens. There were no apparent differences between the induced and noninduced extracts in the alcian blue analysis for K antigens (data not shown), which migrate as two distinct ladder patterns of different mobilities (49). Analyses of silver stained, noninduced cell extracts (Fig. 2, lane 1) showed primarily rough LPS and only trace amounts of smooth LPS (R-LPS and S-LPS, respectively), a pattern that is typical of Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) spp. S-LPS is either absent or expressed at only very low levels in most wild-type Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) strains examined to date (21, 49, 55). In contrast, NGR234 cells grown in the presence of apigenin (Fig. 2, lane 2) yielded a different LPS banding pattern. In addition to a small amount of the typical S-LPS bands, a series of approximately 10 to 15 tightly grouped, prominent bands of higher mobilities appeared (labeled as “PS” to reflect the presence of a polysaccharide component and to distinguish these from the typical S-LPS). The fact that the “PS” component appeared on the gel without the alcian blue pretreatment suggested that it was a new, structurally modified form of LPS (48, 49).

FIG. 2.

Deoxycholate-PAGE analysis of the phenol-water extracts (aqueous phase) of polysaccharides (PS) of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and the FixF− mutant (NGRΩfixF). Lanes: 1, noninduced, parent strain NGR234; 2, NGR234 induced by 10−6 M apigenin; 3, apigenin-induced NGRΩfixF. The gel was stained directly with silver reagent to visualize only LPS species. Noninduced NGR234 shows a major, low-molecular-weight form of LPS (rough LPS that lacks the O antigen; bottom band). Incubation with apigenin (and other specific flavonoids) induces expression of a higher-molecular-weight form of LPS (smooth LPS), which carries the rhamnan O antigen that is absent from the FixF− mutant. These induced components are labeled “PS” to designate the polysaccharide component and to distinguish them from the normal, noninduced smooth-LPS that is characteristic of noninduced cells (lane 1).

The PAGE-silver stain protocol was then applied to apigenin-induced cells of NGRΩfixF. NGRΩfixF did not produce the PS (Fig. 2, lane 3). To examine whether this inducible PS is produced during the later stages of symbiosis, bacteroids were isolated from V. unguiculata nodules inoculated with wild-type NGR234 by following published procedures (24). In a preliminary report (24), we used DOC-PAGE analysis to show that PS components of identical mobilities and staining characteristics are also produced by these bacteroids.

FixF controls production of an LPS O antigen.

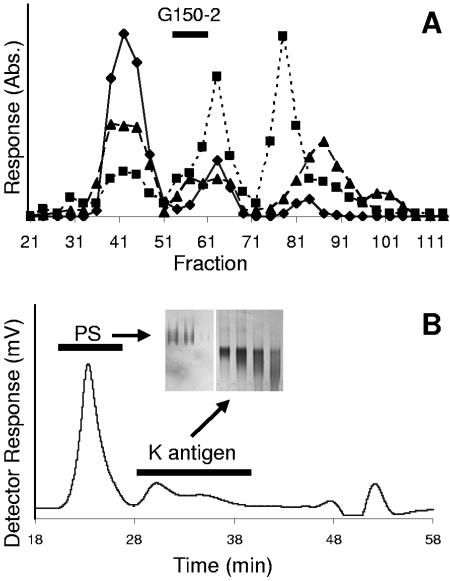

To further characterize the nature of the FixF-dependent polysaccharide component (putative LPS), the chromatographic properties of the material were examined under both dissociative and associative conditions. The putative LPS material (Fig. 2 lane 2) was isolated from large-scale cultures of apigenin-induced wild-type NGR234 and then separated from other polysaccharides by sequential SEC chromatography, first on Sephadex G-150 (dissociative conditions) and then on Superose-12 (associative conditions) (Fig. 3). Fractions containing the PS (Fig. 3A) contained primarily Kdo and hexose and low levels of uronic acid (the last glycosyl component, as well as Kdo analogues, arises from comigrating K antigens). Thus, although chromatography under dissociative conditions completely separated the PS material from the R-LPS (which eluted in fractions 71 to 95), it was still contaminated with K-antigen fragments and neutral polysaccharides. To obtain preparations of greater purity, the pooled PS-containing fractions from several preparations were further fractionated without detergent on Superose-12 (Fig. 3B, including DOC-PAGE inset), which allows the LPS to reaggregate and elute in the void volume. As expected, the PS material eluted in the column void volume (pool G150-2 · Sup12-1), suggesting that it was a form of LPS, while the K antigens and neutral polysaccharides eluted in later fractions, essentially unchanged from their elution positions under dissociative conditions.

FIG. 3.

A, Sephadex G-150 SEC elution profile of the phenol-water extract (water phase) from induced Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234; fractions were assayed for the presence of hexose (A492 [Abs.]; triangles), uronic acid (A520; diamonds), and Kdo (A550; squares). The PS eluted in fractions 53 to 61 (pool G150-2), which is shown by the solid bar. B, Superose-12 SEC elution profile of pool G150-2 material, using a refractive-index detector. The PS eluted in the void volume of the column due to the presence of the lipid anchor. PAGE analysis of the PS (G150-2 · Sup12-1) and the K antigen are shown in the inset.

Carbohydrate and lipid composition analyses of pool G150-2 · Sup12-1 demonstrated that the inducible LPS contains glucose (Glc), Kdo, glucosamine (GlcN) detected as N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), rhamnose (Rha), 3-O-methylRha, and mannose (Man) in a 6:2:1:24:2:1 ratio (the GlcNAc is indicative of the lipid A portion of LPS). This material also contained the LPS-specific β-OH-C14:0, β-OH-C16:0, and β-OH-C18:0 fatty acids, although the β-OH-C18:0 content was fourfold higher than in purified R-LPS from noninduced cells. Importantly, the uronic acids associated with the serogroup-specific core oligosaccharides, typical of the dominant R-LPS produced by noninduced wild-type cells (49), were not detected. These results indicated that both the core region and lipid A are structurally modified from those of noninduced wild-type cells and that the PS material is a rhamnose homo-polymer (rhamnan) O antigen carried on the structurally modified core-lipid A anchor. Moreover, mild acid hydrolysis of this induced LPS, under conditions which specifically cleave labile Kdo linkages (1% acetic acid, 100°C, 1 h), followed by rechromatography on Superose-12, resulted in the displacement of all glycosyl residues away from the void volume (where LPS aggregates elute), into the included volume (typical of nonaggregating O-antigen polysaccharides and core oligosaccharides), indicating that these components were previously linked together by Kdo residues (typical of LPS). Methylation analysis of the polysaccharide fraction released by mild acid hydrolysis showed the presence of two major components: 2-linked Rha and 3-linked Rha in a 1:2 ratio, along with minor amounts of terminal Rha. All rhamnosyl residues were determined to be in the l configuration by GC-MS analysis of the TMS (+)-sec-butylglycosides. The Glc, Man, and GlcNAc residues of the intact LPS were found to be in the d configuration.

1H-NMR analysis of the intact LPS (lipid A-core-rhamnan [data not shown]) revealed a major group of resonances between δ 1.0 and δ 1.4, which correspond to the C6 methyl protons of the rhamnosyl residues and the methylene protons from fatty acids, as well as a broad resonance at δ 0.8 originating from the terminal methyl protons on the fatty acids. Resonances at δ 1.8 and δ 2.05 were due to the C3 methylene protons of Kdo, and resonances around δ 2.00 were due to N-acetyl protons, showing that not all of the GlcN originated from the lipid A moiety. As described above, the flavonoid-induced LPS was treated with 1% acetic acid (100°C, 1 h), which released the lipid A by hydrolysis of the acid labile Kdo ketosidic linkage. Then, the visibly agglutinated lipid A was removed by centrifugation. Subsequent dialysis removed the Glc and Man (presumably low-molecular-weight core components), as well as most of the Kdo, yielding the water-soluble, nondialyzable rhamnan O polysaccharide for further NMR analysis.

A 1H-NMR spectrum of the soluble rhamnan was then obtained (Fig. 4); the resonances between δ 1.26 and δ 1.30 are due to the Rha H6 protons, and those between δ 3.5 and δ 4.2 correspond to the ring methine protons. A sharp signal at δ 3.68 arises from 3-O-MeRha methoxyl protons. The anomeric proton resonances range from δ 4.95 to δ 5.18, and have the typically small (1- to 2-Hz) J1,2 coupling of α-linked aldoses, specifically those having the manno configuration. The chemical shifts for two major anomeric resonances were established from COSY, TOCSY, and HSQC experiments (carbon δ in parentheses) at δ 5.02 (104.8) and δ 4.95 (104.8). Three secondary anomeric resonances were also identified at δ 5.18 (103.6), δ 5.16 (103.6), and δ 5.10 (103.4). In addition, the anomeric proton for a very minor component was found at δ 5.00 (103.6).

FIG. 4.

1H-NMR spectrum (500 MHz) of the purified rhamnan (PS), which was released from the LPS core-lipid A with mild acid, from apigenin-induced Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. Anomeric signals from the four glycosyl residues of the repeating unit are labeled (A to D).

The TOCSY spectrum (Fig. 5) showed clear couplings for all protons belonging to what was subsequently identified as four glycosyl spin systems, allowing complete and unambiguous proton assignments. Magnetization transfer was strongest from H3 through H6, typical of rhamnosyl residues in the manno configuration. For each spin system, suitable entry points could be made at both the H1 and H6 protons. COSY analysis (not shown) confirmed assignments for H1/H2 and H6/H5 for the four glycosyl spin systems. TOCSY and COSY results were then used to assign the respective carbon shifts in the HSQC spectrum (Fig. 6). The complete proton and carbon chemical shifts for the two major glycosyl residues (designated residues A and B) and two less abundant residues (designated C and D) are reported in Tables 2 and 3. The downfield shift of carbon 3 for both residues A and B (δ 80.8 and δ 80.6, respectively) indicated that these two residues are the 3-linked residues identified during methylation analysis. This conclusion was supported by three-bond HMBC correlations from carbon 1 of residues adjoining H3 of these two residues (not shown) and by strong interresidue NOEs (discussed below).

FIG. 5.

Partial 500-MHz 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum of the rhamnan O-chain polysaccharide isolated from apigenin-induced cell cultures of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. The rhamnan was isolated by mild acid hydrolysis of the flavonoid-induced LPS and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Four distinct rhamnosyl spin systems can be identified; the figure shows connectivities for protons H1 through H5. Strong coupling between H4/H6 and H5/H6 for all four glycosyl residues was also observed (not shown). Proton chemical shifts are reported in Table 2.

FIG. 6.

Partial 500-MHz 1H-13C HSQC spectrum of the flavonoid-induced rhamnan O chain, showing connectivities for protons H2, H3, H4, and H5 to their respective carbons. Carbons A3, B3, C2, and D2 resonate approximately 10 ppm downfield from their otherwise expected positions, due to glycosidic substitution. Carbon C3 is also downfield (coincident with B3) due to endogenous 3-O-methylation. Glycosyl composition and linkage analysis indicate that approximately 20% of the 2-linked rhamnosyl residues (residue D) are 3-O-methylated (designated residue C). Carbon shifts obtained from HSQC are reported in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

1H assignmentsa for rhamnan of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234

| Glycosyl residueb | Chemical shift (ppm)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 | |

| →3)-α-l-Rhap(1→ (A) | 4.95 | 4.15 | 3.83 | 3.55 | 3.76 | 1.27 |

| →3)-α-l-Rhap(1→ (B) | 5.02 | 4.12 | 3.89 | 3.56 | 3.87 | 1.30 |

| →2)-α-l-3MeRhap(1→ (C) | 5.10 | 4.08 | 3.88 | 3.48 | 3.72 | 1.26 |

| →2)-α-l-Rhap(1→ (D) | 5.18/5.16 | 4.07 | 3.94 | 3.49 | 3.82 | 1.29 |

Chemical shifts in parts per million, assigned from the COSY and TOCSY experiments, using acetone as the reference.

3MeRhap, 3-O-methyl-rhamnopyranose. (A) to (D) designate the four identified glycosyl spin systems.

TABLE 3.

13C assignmentsa for rhamnan of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234

| Glycosyl residueb | Chemical shift (ppm)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| →3)-α-l-Rhap(1→ (A) | 104.79 | 72.83 | 80.78 | 74.29 | 72.05 | 17.9 |

| →3)-α-l-Rhap(1→ (B) | 104.85 | 72.83 | 80.56 | 74.31 | 72.85 | 17.9 |

| →2)-α-l-3MeRhap(1→ (C) | 103.44 | 80.91 | 80.56 | 74.91 | 72.31 | 18.0 |

| →2)-α-l-Rhap(1→ (D) | 103.65 | 80.92 | 72.85 | 74.96 | 71.96 | 18.1 |

Chemical shifts in parts per million assigned from HSQC analysis, using acetone as the reference.

3MeRhap, 3-O-methyl-rhamnopyranose. (A) to (D) designate the four identified glycosyl spin systems.

Using similar correlations, it was possible to completely assign all groups of the 2-linked rhamnose (residue D). Two downfield anomeric resonances (δ 5.18 and δ 5.16) result from this residue; i.e., both anomeric resonances have the same carbon chemical shift and both share connectivity to the same H2, which shows connectivity to only one H3, etc. (i.e., they belong to the same spin system). The reason for the two distinct H1 resonances was not determined, but it indicates a difference in the chemical environment of the protons, possibly reflecting two favored polysaccharide populations having distinct, but interchangeable, conformations. Interestingly, NOE correlations to the H3 proton of residue B were obtained for both anomeric resonances of this residue (D) (Fig. 7). The downfield shift of carbon 2 for residue D (Table 3) indicates that residue D is the 2-linked residue detected during methylation analysis.

FIG. 7.

Partial 500-MHz 1H-1H NOESY spectrum of the flavonoid-induced rhamnan. Strong interresidue NOEs are indicated (A1,D2; D1,B3; B1,A3), confirming glycosidic linkage position and sequence. Intraresidue NOEs and several weaker interresidue NOEs between anomeric protons and protons adjacent to the linkage position (e.g., D1,B2 and B1,A4) are also designated. As determined from the peak area of integration of GC-MS and NMR signals, approximately 20% of the 2-linked rhamnosyl residues are 3-O-methylated (residue C). An interresidue NOE between residue C (H1, δ 5.10) and residue B (H3, δ 3.89) supports a 1→ 3 linkage between these residues.

The 1H-1H NOESY spectrum (Fig. 7) revealed three strong interresidue correlations, reflecting the positions and glycosidic sequences for three prominent linkages in the rhamnan polysaccharide. These strong NOEs were observed between the anomeric protons and the corresponding ring protons at the glycosidically substituted carbon of the aglycon residue. The NOEs were observed at (residue, proton) D1,B3 (δ 5.18/5.16, δ 3.89), B1,A3 (δ 5.02, δ 3.83), and A1,D2 (δ 4.95, δ 4.07) and establish that Rha D is linked to the C3 of Rha B, Rha B is linked to the C3 of Rha A, and Rha A is linked to C2 of Rha D. Furthermore, comparatively weak, intraresidue NOE correlations between protons H1/H2 for all residues indicated an equatorial-equatorial configuration for these protons, confirming that the l-Rha residues are α linked (1). Thus, the FixF-dependent, bacteroidal polysaccharide is an LPS O antigen, consisting of trisaccharide repeating units having the sequence [-3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,2)-α-l-Rhap-(1-]n that are attached to a modified core-lipid A. Interestingly, the primary sequence of the rhamnan is the same as the primary sequence of the P. aeruginosa A-band O antigen, except that the A-band rhamnan consists of d-Rha instead of l-Rha (52).

Based on the carbon 2 and carbon 3 downfield chemical shifts (at δ 80.9 and δ 80.6, respectively), and the fact that 3-O-methylRha was detected in the glycosyl composition analysis (but neither 3-O-methylRha nor 2,3-methylRha was obtained during methylation analysis), the anomeric resonance at δ 5.10 (103.4) must originate from the 2-linked-3-O-methylrhamnosyl residue. Also, a weak NOE correlation from H1 of the 3-O-methylRha (designated residue C) to H3 of Rha residue B (δ 5.10/δ 3.89) (Fig. 7) showed that it is part of the rhamnan molecule. Integration values for the anomeric resonances indicated that approximately 20% of the 2-linked residues are 3-O-methylRha; therefore, about one in every five repeats contain endogenous methylation at O-3 of the 2-linked rhamnosyl residues. The minor anomeric resonance, at δ 5.00 (103.6), appears to be due to a terminal 3-O-methylRha, but this was not firmly established because of its low abundance. Integration of the H2 resonance (δ 4.31) indicated that this residue was present at approximately 5% of the abundance of Rha residue A. If it is a terminal sugar, or “cap” residue, this would indicate an average degree of polymerization of 10 to 12 trisaccharide repeats for the rhamnan (approximate molecular mass, 4,400 to 5,300 mass units), which is in agreement with the PAGE data.

DISCUSSION

Structural analysis of a flavonoid-inducible glycoconjugate, originally believed to be a polysaccharide, showed that it is a new form of LPS (represented in Fig. 8) containing a modified core oligosaccharide-lipid A and a unique O-antigen polysaccharide consisting of trisaccharide repeating units of rhamnose: [-3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,2)-α-l-Rhap-(1-]n. Previously, DOC-PAGE analysis indicated that a rhamnan polysaccharide is also produced in bacteroids (16, 24). Subsequent analysis of bacteroid extracts also revealed an abundance of rhamnose (data not shown), which supports the PAGE observations. Together, these results show that flavonoid induction of vegetative NGR234 cells, or bacteroid development, results in a major change in LPS surface chemistry, from one in which rough-LPS is the dominant form (free-living noninduced cells) to one in which smooth-LPS, containing a structurally unique O antigen, is a dominant form. The structure of the rhamnan isolated directly from Vigna bacteroids is currently under investigation. Due to environmental differences between bacteroids and the induced vegetative state, structural differences between these two rhamnans could exist.

FIG. 8.

Top panel, hypothetical structure of the LPS from cells of Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) sp. strain NGR234 that have undergone phase shift to the chronic infection state (i.e., bacteroids). Most isolates of free-living Rhizobium spp. examined to date, including NGR234, synthesize abundant R-LPS, with little or no detectable S-LPS production (21, 49, 55). Production of an S-LPS, containing a rhamnan O antigen is up-regulated in bacteroids and during flavonoid induction. Inner core, inner core region oligosaccharide; Outer core, outer core region. The “clubs” represent the 3-O-methyl group on some 2-linked rhamnose residues in the O-antigen repeating unit. Bottom panel, primary sequence of the trisaccharide repeats of the Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 rhamnan, [-3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,3)-α-l-Rhap-(1,2)-α-l-Rhap-(1-]n, and comparison of the A-band O antigen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the rhamnan from Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234.

dTDP-l-rhamnose, the probable precursor of the rhamnan, is synthesized from d-glucose-1-phosphate. All enzymes needed for the conversion of d-glucose-1-phosphate to dTDP-l-rhamnose are encoded by an adjacent, flavonoid-inducible locus (17, 28, 39). Rhamnan synthesis thus appears to be transcriptionally regulated in a manner similar to that of Nod factors, i.e., via NodD1, nod boxes, and flavonoids. Studies of R. meliloti have shown that extracellular polysaccharides or K antigens are often important for the initial steps of infection (20, 38, 51), but there is no evidence of an abnormal production of these components by NGRΩfixF.

FixF is homologous to RkpJ (R. meliloti) and KpsS (E. coli). kpsS is a conserved gene that is required for translocation of the K antigen and appears to function in the attachment of the polymerized polysaccharide to a Kdo-lipid complex. Wild-type E. coli cells secrete K antigen with a single Kdo residue at the reducing terminus, which is attached to a lipid anchor, whereas kpsS mutants accumulate nonacylated polysaccharides that lack internal Kdo (37). RkpJ also functions in translocation of K antigen to the R. meliloti cell surface (27). Given the homology of fixF to kpsS, it seems likely that FixF also functions in the attachment of the polymerized rhamnan to the modified LPS core.

Since Rha, Glc, and Kdo are the most abundant glycosyl components of the inducible LPS and the rhamnan can be separated from the LPS anchor by mild acid hydrolysis (and rechromatography), it seems likely that the rhamnan O antigen is linked through Kdo directly to an inner core (Fig. 8). The fact that serogroup B antibodies, which recognize both the R-LPS and the S-LPS of normally cultured cells (50), do not react with the induced rhamnan LPS is further evidence that the serogroup-specific outer core glycosyl residues are absent (data not shown). In the case of the noninduced NGR234, these outer core region glycosyl residues consist mainly of galacturonic acid (49); glycosyl composition analysis indicates that this glycosyl component is absent in the apigenin-induced LPS. In addition to core region modifications, the induced rhamnan-LPS shows an altered fatty acyl composition compared to the R-LPS from vegetative cells (21). The complete structural details of this core-lipid A, including the location and type of acyloxyacyl residues, are unknown and are currently under investigation. At this time, there is no evidence of a role for FixF in the synthesis of the induced core-lipid A.

Although the NGR234 rhamnan has the same primary sequence as the A-band O antigen of P. aeruginosa LPS, the latter is composed of d- rather than l-rhamnose (19, 52). Minor amounts of 3-O-methylRha are found in both the A-band and NGR234 rhamnan O antigens. Endogenously methylated glycosyl residues were previously reported as “capping residues” of various O polysaccharides, including those from Rhizobium etli LPS (14) and Rhizobium loti (53). The location of such residues at the nonreducing terminus of the polysaccharide would block further elongation, specifically for those O antigens believed to be synthesized by the “monomeric” mechanism, in which individual monosaccharides are transferred consecutively from the corresponding XDP-sugar donor to the growing nonreducing end (32).

Previous studies with R. etli and Rhizobium leguminosarum have shown that LPS mutants, containing specific structural defects in the O-antigen portion of their LPSs, are unable to maintain or establish a normal nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with their legume hosts, yielding either Nod+ Fix− or Nod− Fix− phenotypes (15, 34-36). In these cases, a correct LPS structure and normal surface abundance appear to be necessary, even after the initial stages of symbiotic infection (e.g., root hair curling and infection thread formation). Results reported here clearly show that in NGR234, the transition from free-living cells to bacteroids is accompanied by a shift in LPS surface chemistry, from R-LPS lacking O antigen in the vegetative state to the expression of S-LPS having a unique O antigen in bacteroids. This “phase shift” in LPS surface chemistry may promote proper interaction between the bacteroid membrane and the surrounding symbiosome membrane, and is probably essential for continued bacteroid survival within the plant-derived symbiosome compartment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant MCB-9728564 from the National Science Foundation (to B. Reuhs), by the Erna och Victor Hasselblads Stiftelse, the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (projects 31-30950.91, 31-36454.92, 31-63893.00, and 3100AO-104097/1), Société Académique de Genève (to S.J.), and the Université de Genève. The Complex Carbohydrate Research Center was supported in part by Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-93ER20097.

We thank Dora Gerber, Hajime Kobayashi, Slobodan Relić, and Şenay Şimşek for their unstinting help. We are grateful to John Glushka for advice with NMR analyses and to Maral Basma for her calculations and generation of the NGR234 rhamnan and A-band polysaccharide structures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeygunawardana, C., and C. A. Bush. 1993. Determination of the chemical structure of complex polysaccharides by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy, p. 199-249. In C. A. Bush (ed.), Advances in biophysical chemistry, vol. 3. JAI Press, Stamford, Conn. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bax, A., and D. G. Davis. 1985. MLEV-17-based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 65:355-360. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenkrantz, N. J., and B. Asboe-Hansen. 1973. A new method for the quantitative determination of uronic acid. Anal. Biochem. 54:484-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenhausen, G., and D. J. Ruben. 1980. Natural abundance N-15 NMR by enhanced heteronuclear spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 69:185-189. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braunschweiler, L., and R. R. Ernst. 1983. Coherence transfer by isotropic mixing: application to proton correlation spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 53:521-528. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broughton, W. J., S. Jabbouri, and X. Perret. 2000. Keys to symbiotic harmony. J. Bacteriol. 182:5641-5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broughton, W. J., C.-H. Wong, A. Lewin, U. Samrey, H. Myint, H. Meyer z. A., D. L. Dowling, and R. Simon. 1986. Identification of Rhizobium plasmid sequences involved in recognition of Psophocarpus, Vigna, and other legumes. J. Cell Biol. 102:1173-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, G. R. O., B. L. Reuhs, and G. C. Walker. 2002. Chronic intracellular infection of alfalfa nodules by Sinorhizobium meliloti requires correct lipopolysaccharide core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3938-3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson, R. W., S. Kalembasa, D. Turowski, P. Pachori, and K. D. Noel. 1987. Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide from a Rhizobium phaseoli mutant that is defective in infection thread development. J. Bacteriol. 169:4923-4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corzo, J., R. Pérez-Galdona, M. León-Barrios, and A. M. Gutiérrez-Navarro. 1991. Alcian Blue fixation allows silver staining of the isolated polysaccharide component of bacterial lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 12:439-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, A. L., E. D. Laue, J. Keeler, D. Moskau, and J. Lohman. 1991. Absorption mode two-dimensional NMR spectra recorded using pulse field gradients. J. Magn. Reson. 94:637-644. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer, H.-M. 1994. Genetic regulation of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbiol. Rev. 58:352-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsberg, L. S., U. R. Bhat, and R. W. Carlson. 2000. Structural characterization of the O-antigenic polysaccharide of the lipopolysaccharide from Rhizobium etli strain CE3. A unique O-acetylated glycan of discrete size containing 3-O-methyl-6-deoxy-l-talose and 2,3,4-tri-O-methyl-l-fucose. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18851-18863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsberg, L. S., K. D. Noel, J. Box, and R. W. Carlson. 2003. Genetic locus and structural characterization of the biochemical defect in the O-antigenic polysaccharide of the symbiotically deficient Rhizobium etli mutant, CE166: replacement of N-acetylquinovosamine with its hexosyl-4-ulose precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51347-51359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraysse, N., S. Jabbouri, M. Treilhou, F. Couderc, and V. Poinsot. 2002. Symbiotic conditions induce structural modifications of Sinorhizobium sp. NGR234 surface polysaccharides. Glycobiology 12:741-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freiberg, C., R. Fellay, A. Bairoch, W. J. Broughton, A. Rosenthal, and X. Perret. 1997. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature 387:394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerwig, G. J., J. P. Kamerling, and J. F. G. Vliegenthart. 1979. Determination of the absolute configuration of monosaccharides in complex carbohydrates by capillary G.L.C. Carbohydr. Res. 77:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg, J. B. 1999. Genetics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa polysaccharides, p. 1-21. In J. B. Goldberg (ed.), Genetics of bacterial polysaccharides. CRC, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 20.Gonzalez, J. E., B. L. Reuhs, and G. C. Walker. 1996. Low molecular weight EPS II of Rhizobium meliloti allows nodule invasion in Medicago sativa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:8636-8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudlavalleti, S. K., and L. S. Forsberg. 2003. Structural characterization of the lipid A component of Sinorhizobium sp. NGR234 rough- and smooth-form lipopolysaccharides. Demonstration that the distal amide linked acyloxyacyl residue containing the long chain fatty acid is conserved in Rhizobium and Sinorhizobium sp. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3957-3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halbleib, C. M., and P. W. Ludden. 2000. Regulation of biological nitrogen fixation. J. Nutr. 130:1081-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanin, M., S. Jabbouri, D. Quesada-Vincens, C. Freiberg, X. Perret, J.-C. Promé, W. J. Broughton, and R. Fellay. 1997. Sulphation of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 Nod factors is dependent on noeE, a new host-specificity gene. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1119-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabbouri, S., M. Hanin, R. Fellay, D. Quesada-Vincens, B. Reuhs, R. W. Carlson, X. Perret, C. Freiberg, A. Rosenthal, D. Leclerc, W. J. Broughton, and B. Relić. 1996. Rhizobium species NGR234 host-specificity of nodulation locus III contains nod- and fix genes, p. 319-324. In G. Stacey, B. Mullin, and P. M. Gresshoff (ed.), Biology of plant-microbe interactions. International Society for Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, St. Paul, Minn.

- 25.Jones, D. G. J., and N. Gutterson. 1987. An efficient mobilizable cosmid vector, pRK7813, and its use in a rapid method for marker exchange in Pseudomonas fluorescens strain HV37a. Gene 61:299-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannenberg, E. L., B. L. Reuhs, L. S. Forsberg, and R. W. Carlson. 1998. Lipopolysaccharides and K-antigens: their structures, biosynthesis, and functions, p. 119-154. In H. P. Spaink, A. Kondorosi, and P. J. J. Hooykaas (ed.), The Rhizobiaceae. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 27.Kiss, E., B. L. Reuhs, J. S. Kim, A. Kereszt, G. Petrovics, P. Putnoky, I. Dusha, R. W. Carlson, and A. Kondorosi. 1997. The rkpGHI and -J genes are involved in capsular polysaccharide production by Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 179:2132-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi, H., Y. Naciri-Graven, W. J. Broughton, and X. Perret. 2004. Flavonoids induce temporal shifts in gene-expression of nod-box controlled loci in Rhizobium sp. NGR234. Mol. Microbiol. 51:335-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewin, A., E. Cervantes, C.-H. Wong, and W. J. Broughton. 1990. nodSU, two new nod-genes of the broad host range strain Rhizobium strain NGR234, encode host-specific nodulation of the tropical tree Leucaena leucocephala. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 3:317-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macura, S., Y. Huang, D. Suter, and R. R. Ernst. 1981. Two-dimensional chemical exchange and cross-relaxation spectroscopy of coupled nuclear spins. J. Magn. Reson. 43:259-281. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathis, R., F. Van Gijsegem, R. De Rycke, W. D'Haeze, E. Van Maelsaeke, E. Anthonio, M. Van Montagu, M. Holsters, and D. Vereecke. 2005. Lipopolysaccharides as a communication signal for progression of legume endosymbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:2655-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer, H., U. R. Bhat, H. Masoud, J. Radziejewska-Lebrecht, C. Widemann, and J. H. Krauss. 1989. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Pure Appl. Chem. 61:1271-1282. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niehaus, K., A. Lagares, and A. Pühler. 1998. A Sinorhizobium meliloti lipopolysaccharide mutant induces effective nodules on the host plant Medicago sativa (Alfalfa) but fails to establish a symbiosis with Medicago truncatula. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:906-914. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noel, K. D., and D. M. Duelli. 2000. Rhizobium lipopolysaccharide and its role in symbiosis, p. 415-431. In E. W. Triplett (ed.), Prokaryotic nitrogen fixation: a model system for analysis of a biological process. Horizon Scientific Press, Wymondham, United Kingdom.

- 35.Noel, K. D., L. S. Forsberg, and R. W. Carlson. 2000. Varying the abundance of O antigen in Rhizobium etli and its effect on symbiosis with Phaseolus vulgaris. J. Bacteriol. 182:5317-5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noel, K. D., J. M. Box, and V. J. Bonne. 2004. 2-O-Methylation of fucosyl residues of a rhizobial lipopolysaccharide is increased in response to host exudate and is eliminated in a symbiotically defective mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1537-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pazzani, C., C. Rosenow, G. J. Boulnois, D. Bronner, K. Jann, and I. S. Roberts. 1993. Molecular analysis of region 1 of the Escherichia coli K5 antigen gene cluster: a region encoding proteins involved in cell surface expression of capsular polysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 175:5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pellock, B. J., H.-P. Cheng, and G. C. Walker. 2000. Alfalfa root nodule invasion efficiency is dependent on Sinorhizobium meliloti polysaccharides. J. Bacteriol. 182:4310-4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perret, X., C. Freiberg, A. Rosenthal, W. J. Broughton, and R. Fellay. 1999. High-resolution transcriptional analysis of the symbiotic plasmid of Rhizobium sp. NGR234. Mol. Microbiol. 32:415-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perret, X., C. Staehelin, and W. J. Broughton. 2000. Molecular basis of symbiotic promiscuity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:180-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrovics, G., P. Putnoky, B. Reuhs, J. Kim, T. A. Thorp, D. Noel, R. W. Carlson, and A. Kondorosi. 1993. The presence of a novel type of surface polysaccharide in Rhizobium meliloti requires a new fatty acid synthase-like gene cluster involved in symbiotic nodule development. Mol. Microbiol. 8:1083-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piantini, U., O. W. Sorensen, and R. R. Ernst. 1982. Multiple quantum filters for elucidating NMR coupling networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104:6800-6801. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price, N. P. J., B. Relić, F. Talmont, A. Lewin, D. Promé, S. G. Pueppke, F. Maillet, J. Dénarié, J.-C. Promé, and W. J. Broughton. 1992. Broad-host-range Rhizobium species strain NGR234 secretes a family of carbamoylated, and fucosylated, nodulation signals that are O-acetylated or sulphated. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3575-3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pueppke, S. G., and W. J. Broughton. 1999. Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and R. fredii USDA257 share exceptionally broad, nested host ranges. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:293-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Putnoky, P., E. Grosskopf, D. T. C. Ha, G. B. Kiss, and A. Kondorosi. 1988. Rhizobium fix genes mediate at least two communication steps in symbiotic nodule development. J. Cell Biol. 106:597-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Relić, B., X. Perret, M. T. Estrada-García, J. Kopcinska, W. Golinowski, H. B. Krishnan, S. G. Pueppke, and W. J. Broughton. 1994. Nod-factors of Rhizobium are a key to the legume door. Mol. Microbiol. 13:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Relić, B., F. Talmont, J. Kopcinska, W. Golinowski, J.-C. Promé, and W. J. Broughton. 1993. Biological activity of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 Nod-factors on Macroptilium atropurpureum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:764-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuhs, B. L., R. W. Carlson, and J. S. Kim. 1993. Rhizobium fredii and Rhizobium meliloti produce 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid-containing polysaccharides that are structurally analogous to group II K antigens (capsular polysaccharides) found in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:3570-3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reuhs, B. L., D. P. Geller, J. S. Kim, J. E. Fox, V. S. K. Kolli, and S. G. Pueppke. 1998. Sinorhizobium fredii and Sinorhizobium meliloti produce structurally conserved lipopolysaccharides and strain-specific K antigens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4930-4938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reuhs, B. L., S. B. Stephens, D. P. Geller, J. S. Kim, J. Glenn, J. Przytycki, and T. Ojanen-Reuhs. 1999. Epitope identification for a panel of anti-Sinorhizobium meliloti monoclonal antibodies and application to the analysis of K-antigens and lipopolysaccharides from bacteroids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5186-5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reuhs, B. L., M. N. V. Williams, J. S. Kim, R. W. Carlson, and F. Côté. 1995. Suppression of the Fix− phenotype of Rhizobium meliloti exoB mutants by lpsZ is correlated to a modified expression of the K polysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 177:4289-4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rocchetta, H. L., L. L. Burrows, and J. S. Lam. 1999. Genetics of O-antigen biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:523-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russa, R., T. Urbanik-Sypniewska, K. Lindström, and H. Mayer. 1995. Chemical characterization of two lipopolysaccharide species isolated from Rhizobium loti NZP2213. Arch. Microbiol. 163:345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmitz, R. A., K. Klopprogge, and R. Grabbe. 2002. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Azotobacter vinelandii: NifL, transducing two environmental signals to the nif transcriptional activator NifA. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:235-242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharypova, L. A., K. Niehaus, H. Scheidle, O. Holst, and A. Becker. 2003. Sinorhizobium meliloti acpXL mutant lacks the C28 hydroxylated fatty acid moiety of lipid A and does not express a slow migrating form of lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12946-12954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stanley, J., D. N. Dowling, M. Stucker, and W. J. Broughton. 1987. Screening costramid libraries for chromosomal genes: an alternative interspecific hybridization method. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 48:25-30. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weissbach, A., and J. Hurwitz. 1958. The formation of 2-keto-3-deoxyheptanoic acid in extracts of Escherichia coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 234:705-709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams, M. N. V., R. I. Hollingsworth, S. Klein, and E. R. Signer. 1990. The symbiotic defect of Rhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharide mutants is suppressed by lpsZ+, a gene involved in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 172:2622-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong, C.-H., C. E. Pankhurst, A. Kondorosi, and W. J. Broughton. 1983. Morphology of root nodules and nodule-like structures formed by Rhizobium and Agrobacterium strains containing a Rhizobium meliloti megaplasmid. J. Cell Biol. 97:787-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.York, W. S., A. G. Darvill, M. McNeil, T. T. Stevenson, and P. Albersheim. 1985. Isolation and characterization of plant cell walls and cell wall components. Methods Enzymol. 118:3-40. [Google Scholar]