ABSTRACT

Based on global biotic homogenization, habitat generalists and specialists play an important role in maintaining the stability of ecosystems. However, limited information is available about the assembly processes and co-occurrence patterns of soil bacterial habitat specialists and generalists in forest ecosystems, particularly their response mechanisms to environmental factors. In this study, high-throughput sequencing technology was used to investigate the role of the ecological assemblage processes of soil bacterial habitat specialists and generalists and their role in maintaining the stability of the symbiotic network in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests (China). The results showed that compared with specialists, the diversity of bacterial habitat generalists was lower, but their distribution ranges and environmental niche breadth were wider. Results from the null and neutral models indicate that, compared to deterministic processes, the community assembly of habitat generalists and specialists is more strongly influenced by stochastic processes, with generalists exhibiting a higher degree of stochasticity than specialists. Network analysis results showed that habitat specialists played a greater role in maintaining the stability of the bacterial co-occurrence network than the generalists. In addition, bacterial habitat specialists were more likely to be affected by light and spatial feature vectors than generalists. These findings provide a novel perspective for understanding the assembly processes and diversity maintenance mechanisms of the forest soil bacterial community.

IMPORTANCE

Limited information is available about bacterial specialists and generalists in forests. Generalists were more affected by stochastic processes than specialists. Specialists played a more important role in network stability than generalists. Light and spatial vectors had stronger effects on specialists than generalists.

KEYWORDS: soil bacteria, niche breadth, habitat generalists, habitat specialists, community assembly process, co-occurrence network

INTRODUCTION

In natural ecosystems, most studies have shown that microbial communities are classified as habitat generalists, specialists, and other taxa depending on their niche breadth (1, 2). Habitat specialists with narrow niche breadth are considered more competitive but less resistant against changing environments, while the habitat range of generalists and their fitness for a particular environment are more extensive (3, 4). In comparison with generalists, habitat specialists have a faster worldwide decline based on niche breadth predictions, contributing to the functional homogenization in biodiversity (5). This homogenization might change ecosystem functioning, thus endangering ecosystem services (6). In addition, some generalists exhibit a rapid rate of niche evolution (7, 8). To some extent, the change of niche breadth can reflect extinction risk (6). Based on global biotic homogenization, habitat generalists and specialists play an important role in maintaining the stability of ecosystems (5).

Ecologists have extensively studied the environmental factors controlling soil microorganism abundance and distribution patterns (9, 10). Results showed that pH, temperature, and salinity are the key environmental factors that control the compositions and distributions of microbial habitat generalists and specialists (11). In addition, light has been shown to significantly influence soil microbial biomass and alter the structure of soil bacterial communities (12). Habitat specialists and generalists of aquatic invertebrates have different ecological responses to environmental changes in various ecosystems. Habitat specialists respond with greater variance to environmental conditions, while generalists respond with less variance to environmental changes (13). In aquatic ecosystems, environmental factors such as salinity, temperature, and total nitrogen have a greater effect on the habitat specialists of microbial communities because specialists might have strict requirements for environmental conditions (11, 14). Habitat specialists may face extinction if drastic environmental disturbances occur (15). However, studies have not established how habitat generalists and specialists of soil bacterial communities differ in response to environmental changes, particularly in forest ecosystems.

Soil bacteria are important drivers of forest biogeochemical processes and play an important role in regulating nutrient cycling and promoting plant growth (16). Bacterial diversity is strongly associated with multiple ecosystem functions, such as climate, habitat disturbance, vegetation, and soil properties of environmental changes (5). The study of these changes is essential for the development of basic ecological theory and predicting the response of ecosystems to environmental change (17, 18). Bacterial diversity in forest ecosystems has received increasing attention (19).

The understanding of the ecological processes of bacterial community aggregation is a continuing subject of debate in the microbial ecology field (14). Bacterial community assembly can be divided into deterministic and stochastic processes (20). Deterministic processes involve environmental filtering (e.g., salinity, pH, and temperature) and biotic interactions (e.g., competition, predation, mutualism, and trade-off) (21, 22). By contrast, stochastic processes include dispersal limitation and random changes (e.g., birth, death, ecological drift, extinction, and speciation) (23). Habitat generalists and specialists of microbial communities in lake sediments in Tibetan lakes are mainly affected by stochastic processes (11). Stochastic processes determine the assembly of micro-eukaryotic community habitat generalists in an anthropogenically impacted river, while the deterministic processes strongly influence the distribution of habitat specialists (14). These inconsistent results suggest differences in community assembly between habitat specialists and generalists that have been attributed to differences in ecosystem type (24, 25). In addition, environmental factors can regulate the balance between deterministic and stochastic processes (26). For example, soil pH and soil moisture content are major drivers that regulate the balance between deterministic and stochastic processes of abundant and rare bacterial subcommunities, respectively (27). Low salinity contributes to the dominance of stochastic processes in micro-eukaryotic plankton community assembly (28). However, researchers have not determined the key environmental factors that regulate the balance between habitat generalists and specialists in community assembly mechanisms in soil bacterial communities of temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests.

The complex interspecific interactions within microorganisms are extremely important for maintaining microbial diversity and ecosystem function (29, 30). At present, most studies have used co-occurrence networks to explore the structure of complex microbial communities and interactions between microorganisms (30), such as oil-contaminated soils (31), rivers (14, 32), and marine water (33). Co-occurrence networks can be used to clarify interactions between microbial taxa, identify keystone species, compute network topological features, and further provide useful information for exploring species coexistence and microbial diversity (11). Additionally, microbial communities can be divided into modules comprising highly interconnected microorganisms, with modularity interpreted as habitat heterogeneity, niche overlap, and phylogenetic correlation (34). However, the co-occurrence patterns of generalists and specialists in temperate forest soil bacterial communities have not been fully understood.

In the present study, 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing was used to sequence bacterial communities from 120 soil samples collected from the forest dynamic monitoring plots of Baiyunshan. The park is rich in species resources and generally belongs to well-preserved natural ecosystems. Baiyunshan National Forest Park (Henan Province, China) is a typical forest ecological zone in the transition zone between the warm temperate and subtropical zones because of its unique geographic location and complex topography, providing an ideal location to study the distribution pattern and ecological process of bacterial communities (18). The distribution pattern of soil bacterial communities has aroused great concern among ecologists (18, 35), but the distribution pattern and mechanism of soil bacterial subcommunities with different niche breadth on temperate forest plots remain poorly understood. The objectives of this study are as follows: (i) to reveal the community assembly mechanisms of soil bacterial community habitat generalists and specialists and analyze the relative importance of stochastic and deterministic processes; (ii) to explore the coexistence patterns of the habitat generalists and specialists; (iii) and to assess the effects of light, plant, topography, and spatial eigenvectors on habitat generalists and specialists. We hypothesized that stochastic processes play a greater role in the community assembly of habitat generalists than specialists. Habitat specialists contribute more to network stability than generalists. In addition, considering the low environmental tolerance of habitat specialists, habitat specialists might be more susceptible to environmental factors than generalists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

The sampling site is located in Baiyun Mountain National Forest Park (111°47'–111°51'E, 33°38'–33°42'N) in Henan Province, China. The park has an area of approximately 168 km2 at elevations from 800 to 2,216 m above sea level and is located in the transition region from warm temperate zone to north subtropical zone (36, 37). Its annual mean temperature is 12.2°C, the extreme maximum temperature is 41.2°C, and the extreme minimum temperature is –14.4°C. The annual mean rainfall is 1,200 mm, mostly from July to September. Baiyun Mountain National Forest Park is rich in plant resources, with an average forest coverage of 81.2% and approximately 1,991 plant species (38). In the present study, Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata, Toxicodendron vernicifluum, and Sorbus alnifolia are some dominant tree species in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests.

Sampling point setting and sample collection

According to the construction standards of the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Tropical Forestry Research (39), a long-term fixed monitoring plot of 4.8 hm2 with a length of 240 m from east to west and 200 m from north to south was established in the Baiyunshan National Forest Park. The 4.8 hectare plot was divided into 120 quadrats (400 m2 each, Fig. 1). Three soil sub-samples were collected from each 20 m × 20 m square (10 m distance among the three sub-samples), and then the three soil samples were mixed evenly into one soil sample. A total of 120 soil samples were collected in this sampling campaign. Each soil sample was divided into two parts; one was used for soil chemical analysis, and the other was stored at –80°C for bacterial microbiological analysis.

Fig 1.

Location and topography of the 4.8 hm2 forest dynamic plot in Baiyun Mountain National Forest Park. The map was created using ArcGIS, with the basemap sourced from the official China Standard Map Service, under map review number GS(2019)1822.

In the plot, all trees with a diameter at breast height ≥1 cm were tagged, measured, mapped, and identified to species (40). The plant stand density, plant richness, plant diversity, and plant basal area were measured and calculated as environmental factors of woody plants. Plant richness refers to the number of species. Plant stand density indicates the number of individual trees. Plant diversity was calculated by reference formula (41). Plant basal area was calculated as π × R2, where R is the radius at a height of 1.3 m (42).

For each 20 × 20 m subplot, the elevation, convexity, aspect, and slope were measured using the methods described by Harms et al. (43) and Valencia et al. (44).

Hemispherical photographs were obtained using a Canon EOS 60D camera (Japan) at four corners of 20 × 20 quadrats at 1.3 m above the ground (45). Photographs were taken during either early dawn, late dusk, and overcast weather whenever possible to ensure the accuracy of the data (46). Three replicate photos were taken, and the photos showing the highest contrast between the sky and foliage were selected as the valid photo. The selected effective photographs were processed using the Hemi View woodland canopy digital analysis system. The average leaf angle, canopy cover (CC), total radiation, scattered radiation (SR), direct radiation, transmittance of light (LT), and leaf area index were obtained (47).

Spatial factors were derived from the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of a truncated distance matrix (PCNM). Based on quadrat coordinates, the geographical distances were converted to geospatial factors (48, 49). Data were log-transformed prior to statistical analysis when necessary. A forward selection procedure was used to select the PCNM variables by using the “pcnm” function in the vegan package (48).

DNA extraction, PCR, and Illumina sequencing

The total soil bacterial DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of fresh soil samples by using the Fast DNA SPIN extraction kit (Mobio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (32). The purified DNA concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington), and its integrity was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The V4-V5 region of prokaryotic 16S rRNA genes was amplified using the universal primer pair of 515F (5′-GTG YCA GCM GCC GCG GTA-3′) and 907R (5′-CCG YCA ATT YMT TTR AGT TT-3′) (50, 51). The PCR amplification cycles for 16S rRNA genes consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (52). The PCR product was purified and quantified as described previously (32). All libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) by using a paired-end (2 × 150 bp) approach. The sequencing and bioinformatics analyses were performed by Huada Gene Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China.

Bioinformatics analysis

Raw paired-end FASTQ sequences were assembled using FLASH (v.1.2.11) under default settings (53). The obtained raw sequence data were analyzed and processed using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology pipeline against the compiled files; the procedures were described in detail by Yao et al. (54). A total of 7,329,751 sequences were obtained from all bacterial samples. After quality filtering, denoising, and chimera removal, the UCLUST algorithm was used to divide the sequences into different operational taxonomic units (OTUs) according to 97% similarity (55). Species annotation was carried out using the Greengenes database (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/).

Analysis of the habitat generalists, specialists, and neutral taxa

The niche breadth was calculated as described by Pandit et al. (56) by using the Levins niche breadth index:

Bj represents the niche breadth of OTU j in the communities, while Pij represents the relative abundance of OTU j in a given habitat i (i.e., each of the 120 samples was considered a “habitat”) (56, 57). A given OTU with a higher B value indicates a wider niche breadth. OTUs with wider niche breadth are more evenly distributed and more metabolically flexible than those with narrower niche breadth (58). The analysis was based on the function “Niche Breadth” in the R package “Spaa” (59).

Microbial communities were divided into generalists or specialists and neutral taxa based on the Levins niche breadth (1). The occurrences of OTUs generated by simulating 1,000 permutations (quasiswap permutation algorithms) were calculated using the EcolUtils R package. The OTUs were further classified as generalists, neutral taxa, and specialists based on their occurrence and by using permutation algorithms as implemented in EcolUtils. Generalists have wider fundamental niches than specialists (60). In the present study, an OTU was considered a generalist or specialist based on whether the observed occurrence exceeded the upper 95% confidence interval or fell below the lower 95% confidence interval, and the OTUs were considered neutral taxa if the observed niche breadth was within the 95% confidence interval range (61). In total, 5.97% of OTUs were classified as generalists, 41.14% as specialists, and the remaining 52.89% as neutral taxa.

Statistical analyses

The richness indices of all samples were calculated using the diversity function in the “Vegan” package (62). The Kruskal-Wallis method was used to test for differences in the bacteria richness and niche breadth in the four communities (63, 64).

Beta-nearest taxon index (beta NTI) and Raup-Crick metric (RC-Bray) values were used in null model analyses to assess the influence of different ecological processes, both stochastic and deterministic, on bacterial community assembly (65). When |βNTI| > 2, deterministic processes govern the observed community turnover between pairs of communities, whereas |βNTI| < 2 suggests that stochastic processes drive community succession (28). Meanwhile, the neutral community model was employed to estimate the potential contribution of neutral processes to community assembly (66). A best-fit distribution curve between OTU occurrence frequency and its relative abundance was generated using nonlinear least-squares analysis (67). In this model, a single free parameter m is used to describe the migration rate. A higher m value indicates that microbial communities are less influenced by environmental constraints (68). The R² value represents the goodness-of-fit to the model and was calculated according to the “Östman method” (69). When R² approaches 1, it suggests that the community assembly is fully consistent with stochastic processes. Model computations were performed using R version 3.6.1.

Furthermore, the effects of deterministic processes on the bacterial community assembly were tested by checking the deviation degree of each observation index from the average value of the null model (C-score) (70). The calculation method of standardized effect size (SES) was based on the research method of Gotelli et al. (71). The magnitude of SES is interpreted as the strength of the effect of deterministic processes on the assemblage, where the higher the absolute value of SES, the stronger the relative contribution of deterministic processes (72). C-score was determined using the sequential swap randomization algorithm with the package “EcoSimR” in R version 3.6.1 (73).

A network analysis method was used to reveal the co-occurrence patterns of generalists, neutral taxa, and specialists in the study area. Network analysis data were visualized using Gephi software (74). The topology structure of the bacterial network was evaluated based on the modularity index. Each node indicates a given OTU, and each edge represents a significant correlation between two OTUs. Degree represents the number of edges connecting each node to the rest of the nodes in the network. For the bacterial community structure, the R language “igraph” package is used to build and analyze the network (75).

In the present study, the partial least-squares path modeling (PLS-PM) was used to quantitatively analyze the direct and indirect effects of light, topography, PCNM, and woody plant factors on bacteria richness. The methods of Chu et al. (76) and Wang et al. (77) were used to analyze the direction and intensity of the effect of environmental variables on species richness. In PLS-PM, each latent variable includes one or more indicator variables. For example, the latent variable (PCNM) includes two indicator variables (PC2 and PC3); plant includes BA (plant richness) and DEN (plant stand density), light includes CC, SR, and LT, and topography includes ASP (aspect). The relationships among these block variables were quantified with path coefficients. The goodness-of-fit index was used to estimate the prediction performance of models (78). PLS-PM was performed using the package “plspm” in R 4.0.1 (41).

RESULTS

Diversity and niche breadth of bacterial communities

Habitat generalists, specialists, neutral taxa, and all bacterial communities had similar spatial distribution patterns (Fig. 2A). In comparison with the specialists, the spatial distribution of the generalists is more extensive. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences in species richness among overall species, generalists, neutral taxa, and specialists (Fig. 2B, P < 0.001). More generalists were identified within Proteobacteria and Planctomycetes, while more specialists were associated with Acidobacteria and Verrucomicrobia (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

Spatial distribution and species composition of overall taxa, specialists, generalists, and neutral taxa in Baiyun National Forest Park. (A) Distribution map of bacterial OTU species in 120 sample plots. (B) Richness index of bacterial communities. (C) Species composition of bacterial communities.

Relative importance of deterministic and stochastic processes

The results of the null model analysis indicated that habitat generalists, specialists, neutral taxa, and the overall bacterial community were all influenced by a combination of deterministic and stochastic processes (Fig. 3A). Both generalists (stochastic processes: 93.7%; deterministic processes: 6.3%) and specialists (stochastic processes: 78.6%; deterministic processes: 21.4%) were predominantly governed by stochastic processes. The relationship between the distribution and relative abundances of bacterial taxa was well-described by the neutral community model (Fig. 3B). The neutral community model well-fitted the frequency of microbial OTU (86.4%) and played an important role in bacterial community assembly. Generalists, neutral taxa, and specialists explained 54.3%, 86.7%, and 91.2% of the community variance, respectively. The relatively higher m value for generalists than for specialists (1.195 vs 0.2298) suggests that generalists are highly diffuse and are less restricted by the environment. In addition, compared with the specialists, the generalists showed a wider niche breadth (Fig. 3C). More importantly, the C-score showed that SES decreased with changes in specialists (Fig. 3D), neutral species, and generalists, suggesting the decreased importance of deterministic processes for bacterial subcommunities assemblage. Both habitat generalists and specialists were more strongly driven by stochastic rather than deterministic processes.

Fig 3.

Ecological processes of the bacterial communities in Baiyun Mountain National Forest Park. (A) Assessment of the influence of stochastic and deterministic processes on soil bacterial community assembly based on a null model. The inner circle represents the contribution of stochastic and deterministic processes to community construction. The outer ring represents the detailed ecological processes assigned to stochastic and deterministic processes. (B) Neutral model applied to assess the effects of random dispersal on the soil bacteria. Rsqr indicates the goodness-of-fit to the neutral model. Nm indicates the metacommunity size times immigration. m indicates the estimated migration rate. The solid blue lines indicate the best fit to the neutral model, and dashed blue lines represent 95% confidence intervals around the model prediction. (C) Comparison of the mean niche breadth of four bacterial taxa. The Kruskal-Wallis test at P < 0.05. (D) C-score metric based on null models. The values of observed C-score (C-scoreobs) > simulated C-score (C-scoresim) indicate non-random co-occurrence patterns. Standardized effect sizes <−0 and >0 represent aggregation and segregation, respectively.

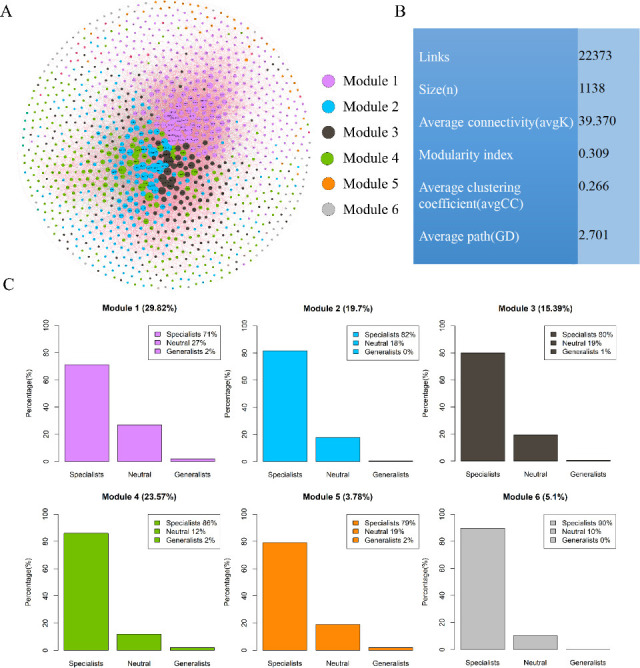

Co-occurrence networks of bacterial microbial communities

The bacterial community network was clearly divided into four major modules, accounting for 88.48% (module 1–module 4) of the whole network (Fig. 4A through C). The co-occurrence network showed high ratios of positive correlations and consisted of 1,138 nodes (OTUs) and 22,373 edges (average connectivity, 39.370). Among all nodes, 15 and 914 OTUs belonged to generalists and specialists, respectively. The average path length was 2.701 edges, and the clustering coefficient and modularity index were 0.266 and 0.309, respectively. Bacterial communities were dominated by taxa preferring specialists in all modules, but only a few generalists were present. In the co-occurrence network, five phyla (Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes, Verrucomicrobia, and Chloroflexi) were widely distributed, accounting for 73.8% of all nodes (Fig. S1).

Fig 4.

Co-occurring network colored by modularity class for soil bacteria in Baiyun Mountain National Nature Reserve. (A) The co-occurrence patterns among OTUs revealed by network analysis. The red lines show positive correlations between nodes, and the green lines show negative relationships. Each node represents different OTUs, and the colors of the nodes indicate different modules. Modules 1–6 display different colors. A group of OTUs in one module means that these OTUs have more interactions among themselves and fewer associations with other modules. (B) Topological properties of the co-occurrence network of soil bacterial communities. (C) Relative abundance of specialists, neutral species, and generalists (OTUs) in the main modules.

Direct and indirect effects of environments on bacterial community

For bacteria richness (Fig. 5 through B), PCNM (spatial effect) had the highest path coefficient of 0.176, which can be attributed to the strong spatial structuring of the plot environment variation. The goodness-of-fit of total bacterial richness and environmental factors was 0.496, which is higher than 0.35, indicating that the model was reliable. The effects of light and PCNM on bacterial richness were statistically significant; the direct and indirect contribution rates of PCNM to bacterial richness were 17.61% and 16.07%, respectively, and the direct and total contribution rates of light to bacterial richness were 17.21% and 19.76%, respectively.

Fig 5.

PLS-PM showing the direct and indirect effects of different factors on bacteria richness. (A) PLS‐PM was used to examine the linkages among light, PCNM, plant, topography, and overall species richness. The blue line indicates positive correlation, while the red line indicates negative correlation. The arrow color and width indicate the strength of the relationship. Numbers on the lines out of the PLS-PM were the “weight” contributions. (B) The positive and negative effects of PCNM, topography, light, and vegetation on bacterial richness. (C) Direct and indirect effects of environmental factors on generalists, neutral species, and specialist richness.

PCNM and light had similar positive or negative effects on the richness of specialists, generalists, and neutral taxa. The path coefficients of light (21.04%) and PCNM eigenvectors (21.23%) of the specialist richness were higher than those of generalists (light, 18.89%; PCNM eigenvectors, 18.11%), indicating that light and PCNM had a greater effect on specialists than generalists.

DISCUSSION

Assembly of bacterial communities

Our results clearly demonstrate the important roles of both stochastic and deterministic processes in bacterial community assembly (Fig. 3). Based on the null model, the neutral community model, niche breadth, and C-score analyses, we found that both generalist and specialist taxa in forest ecosystems were more influenced by stochastic processes than by deterministic ones. Habitat generalists showed a higher degree of stochasticity compared to specialists. Similarly, Zou et al. found that both generalist and specialist planktonic bacterial taxa in lakes and reservoirs were mainly governed by stochastic processes (79). In our study, habitat generalists had broader niche breadths, which allowed them to tolerate a wider range of environmental conditions (80). This may explain why they were more strongly affected by stochasticity. Meanwhile, the C-score results indicate that as the niche breadth decreases from broad (habitat generalists) to narrow (habitat specialists), the SES value declines, indicating a reduced influence of deterministic processes and an increased dominance of stochastic processes. This reflects the differences in ecological strategies among different functional groups in terms of spatial dispersal and environmental adaptation, further supporting that dispersal limitation is the dominant process shaping specialist communities.

However, habitat specialists in farmland microbial communities often exhibit strong preferences for specific environmental conditions, rendering them more susceptible to species sorting, a form of deterministic process (81). This is inconsistent with our findings. In our study, dispersal limitation contributed the most to the assembly of specialist communities, with a maximum contribution of 44.42%. This could be due to their narrower spatial distributions (Fig. 2A), narrower niche breadths (Fig. 3C), and lower dispersal abilities. These traits may prevent them from crossing spatial barriers to reach suitable habitats. Specialists may try to escape unfavorable environments, but due to their weak dispersal capacity, they are more likely to be limited by dispersal (82). In environments with low human disturbance, stochastic processes tend to dominate (83). Our study site is a national nature reserve that has remained nearly undisturbed for over a century. The low environmental filtering pressure in such a stable environment may have reduced deterministic constraints on specialists, thereby increasing their susceptibility to stochastic processes (81). In summary, in temperate deciduous broadleaf forests, both specialists and generalists are more strongly shaped by stochastic processes. Generalists, however, are influenced by stochasticity to a greater extent than specialists.

Coexistence patterns of the habitat generalists and specialists

In this study, habitat specialists contributed more to the stability of the entire bacterial network than generalists. All six densely connected modules were dominated by habitat specialists (typically accounting for over 70%), while widely distributed generalists were extremely rare (Fig. 4). This specialist-dominated modular structure suggests a significant degree of niche differentiation within the community. Within the co-occurrence network, habitat specialists were more likely to function as intra-module hubs, playing a pivotal role in maintaining the structural integrity and functional coherence of individual modules. In contrast, generalists, despite having fewer intra-modular associations, tended to act as connectors across modules, thereby contributing to the overall functional redundancy and resilience of the microbial community (81). Our analysis showed that habitat specialists comprised 80.32% of the network nodes, while generalists accounted for only 1.32%, highlighting the critical structural role of specialists. This is consistent with previous findings (11), showing that specialists tend to form more complex and stable network structures (6, 28).

Within these modular structures, keystone taxa were frequently located at the module cores, characterized by a high degree and high betweenness centrality, linking multiple functional pathways and enhancing module stability (84). Our study further found that all keystone taxa belonged to habitat specialists, emphasizing their irreplaceable role in maintaining module functions. The loss of these central nodes could lead to a rapid collapse of intra-module cooperative relationships and result in disruptions to ecological processes and functional losses (85). Therefore, specialists not only dominate niche partitioning but also play a crucial role in sustaining both network integrity and ecosystem functioning.

Direct and indirect effects of environmental factors on bacterial community structure

In the present study, the variation in bacterial richness is mainly explained by the light and space eigenvectors in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests (Fig. 5). Light had a direct negative effect on bacterial richness, which is consistent with previous studies (86). Under the dense canopy, the light is weak, the water evaporates less, and the soil moisture is very high (74). In addition, humus is very abundant in low-light conditions, which is beneficial to the reproduction and survival of soil bacteria (87). Therefore, soil bacteria may have a strong distribution preference for low-light habitats. Spatial eigenvectors can also affect bacterial richness directly and indirectly, which is consistent with other studies (87). The 17.6% variability explained by spatial eigenvectors may reflect dispersal and biological interactions (88, 89). The explanatory power of topography and woody plants to bacterial richness is weak, which is consistent with a previous report (87), possibly because of the limited topographic variability and the aggregation distribution of species. This condition reduced the community heterogeneity.

In the present study, bacterial habitat specialists were more likely to be affected by light and space eigenvectors than generalists, which was consistent with previous findings (35). Habitat specialists had a higher degree of response to environmental change than generalists, because habitat generalists showed broad environmental tolerance, while habitat specialists exhibited a narrow range of environmental tolerances, being more sensitive to and less resistant to environmental changes (35). Light and space eigenvectors are important drivers of habitat specialists, which might influence the richness of habitat specialists in part by limiting bacterial dispersal. This finding suggests that habitat specialists may have stringent requirements for environmental conditions, and their living conditions largely depend on these specific or combined environmental factors (15). Habitat specialists face extinction if severe environmental disturbances occur. A relatively large proportion of species variation in our data cannot be explained by light and spatial data, partly because of random dispersal, but it might also include deterministic changes caused by unmeasured environmental variables (soil physical and chemical properties, etc.) (90, 91).

Conclusion

A conceptual framework was designed to describe the community assembly process of soil bacterial habitat generalists and specialists in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests, the environmental breadth, and the role in co-occurrence network stability (Fig. 6). Habitat generalists exhibited broader environmental breadths than specialists, and their community assembly was predominantly influenced by stochastic processes in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests. In contrast, habitat specialists contributed more significantly to the stability of the entire co-occurrence network than generalists. Overall, our findings may have important implications for the formation and maintenance of soil bacterial diversity in temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests and help in predicting the response of bacterial communities to surrounding environmental changes.

Fig 6.

Conceptual map showing the environmental breadth, co-occurrence pattern, and stochastic processes in the assembly of soil bacterial habitat generalists and specialists in the mountain forest ecosystem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Biodiversity Conservation Research (GZS2023006).

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Yun Chen, Email: cyecology@163.com.

Zhiliang Yuan, Email: yzlsci@163.com.

Jennifer F. Biddle, University of Delaware, Lewes, Delaware, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

All raw read data of 16S genes have been submitted to the NCBI GEO under the accession number PRJNA633088.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00992-25.

Relative abundance at the level of phyla.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kokou F, Sasson G, Friedman J, Eyal S, Ovadia O, Harpaz S, Cnaani A, Mizrahi I. 2019. Core gut microbial communities are maintained by beneficial interactions and strain variability in fish. Nat Microbiol 4:2456–2465. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0560-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slatyer RA, Hirst M, Sexton JP. 2013. Niche breadth predicts geographical range size: a general ecological pattern. Ecol Lett 16:1104–1114. doi: 10.1111/ele.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen YJ, Leung PM, Wood JL, Bay SK, Hugenholtz P, Kessler AJ, Shelley G, Waite DW, Franks AE, Cook PLM, Greening C. 2021. Metabolic flexibility allows bacterial habitat generalists to become dominant in a frequently disturbed ecosystem. ISME J 15:2986–3004. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-00988-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rain‐Franco A, Mouquet N, Gougat‐Barbera C, Bouvier T, Beier S. 2022. Niche breadth affects bacterial transcription patterns along a salinity gradient. Mol Ecol 31:1216–1233. doi: 10.1111/mec.16316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clavel J, Julliard R, Devictor V. 2011. Worldwide decline of specialist species: toward a global functional homogenization? Frontiers in Ecol & Environ 9:222–228. doi: 10.1890/080216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mo YY, Zhang WJ, Wilkinson DM, Yu Z, Xiao P, Yang J. 2021. Biogeography and co‐occurrence patterns of bacterial generalists and specialists in three subtropical marine bays. Limnology & Oceanography 66:793–806. doi: 10.1002/lno.11643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sébastien L, EME K, BI J, Frederic J, Wilfried T. 2013. Are species’ responses to global change predicted by past niche evolution? Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B. Biol Sci 368:20120091. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lavergne S, Evans MEK, Burfield IJ, Jiguet F, Thuiller W. 2013. Are species’ responses to global change predicted by past niche evolution? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20120091. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bahram M, Hildebrand F, Forslund SK, Anderson JL, Soudzilovskaia NA, Bodegom PM, Bengtsson-Palme J, Anslan S, Coelho LP, Harend H, Huerta-Cepas J, Medema MH, Maltz MR, Mundra S, Olsson PA, Pent M, Põlme S, Sunagawa S, Ryberg M, Tedersoo L, Bork P. 2018. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature 560:233–237. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wan WJ, Gadd GM, Yang YY, Yuan WK, Gu JD, Ye LP, Liu WZ. 2021. Environmental adaptation is stronger for abundant rather than rare microorganisms in wetland soils from the Qinghai‐Tibet Plateau. Mol Ecol 30:2390–2403. doi: 10.1111/mec.15882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yan Q, Liu YQ, Hu AY, Wan WJ, Zhang ZH, Liu KS. 2022. Distinct strategies of the habitat generalists and specialists in sediment of Tibetan lakes. Environ Microbiol 24:4153–4166. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.16044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma S, Verheyen K, Props R, Wasof S, Vanhellemont M, Boeckx P, Boon N, De Frenne P. 2018. Plant and soil microbe responses to light, warming and nitrogen addition in a temperate forest. Funct Ecol 32:1293–1303. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kneitel JM. 2018. Occupancy and environmental responses of habitat specialists and generalists depend on dispersal traits. Ecosphere 9:n doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gad M, Hou LY, Li JW, Wu Y, Rashid A, Chen NW, Hu AY. 2020. Distinct mechanisms underlying the assembly of microeukaryotic generalists and specialists in an anthropogenically impacted river. Science of The Total Environment 748:141434. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liao JQ, Cao XF, Zhao L, Wang J, Gao Z, Wang MC, Huang Y. 2016. The importance of neutral and niche processes for bacterial community assembly differs between habitat generalists and specialists. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 92:fiw174. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen QL, Hu HW, Yan ZZ, Li CY, Nguyen BAT, Sun AQ, Zhu YG, He JZ. 2021. Deterministic selection dominates microbial community assembly in termite mounds. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 152:108073. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.108073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yue K, Yang W, Peng Y, Peng C, Tan B, Xu Z, Zhang L, Ni X, Zhou W, Wu F. 2018. Individual and combined effects of multiple global change drivers on terrestrial phosphorus pools: a meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment 630:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sheng YY, Cong W, Yang LS, Liu Q, Zhang YG. 2019. Forest soil fungal community elevational distribution pattern and their ecological assembly processes. Front Microbiol 10:2226. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mi XC, Feng G, Hu YB, Zhang J, Chen L, Corlett RT, Hughes AC, Pimm S, Schmid B, Shi SH, Svenning JC, Ma KP. 2021. The global significance of biodiversity science in China: an overview. Natl Sci Rev 8:nwab032. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwab032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hou L, Hu A, Chen S, Zhang K, Orlić S, Rashid A, Yu C-P. 2019. Deciphering the assembly processes of the key ecological assemblages of microbial communities in thirteen full-scale wastewater treatment plants. Microbes Environ 34:169–179. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME18107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peter C. 2000. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 31:343–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fargione J, Brown CS, Tilman D. 2003. Community assembly and invasion: an experimental test of neutral versus niche processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:8916–8920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033107100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chave J. 2004. Neutral theory and community ecology. Ecol Lett 7:241–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2003.00566.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Székely AJ, Langenheder S. 2014. The importance of species sorting differs between habitat generalists and specialists in bacterial communities. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 87:102–112. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stilmant D, Van Bellinghen C, Hance T, Boivin G. 2008. Host specialization in habitat specialists and generalists. Oecologia 156:905–912. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-1036-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang HJ, Hou FR, Xie WJ, Wang K, Zhou XY, Zhang DM, Zhu XY. 2020. Interaction and assembly processes of abundant and rare microbial communities during a diatom bloom process. Environ Microbiol 22:1707–1719. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang JM, Li MX, Li JW. 2021. Soil pH and moisture govern the assembly processes of abundant and rare bacterial communities in a dryland montane forest. Environ Microbiol Rep 13:862–870. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.13002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mo YY, Peng F, Gao XF, Xiao P, Logares R, Jeppesen E, Ren KX, Xue YY, Yang J. 2021. Low shifts in salinity determined assembly processes and network stability of microeukaryotic plankton communities in a subtropical urban reservoir. Microbiome 9:128. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01079-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiao S, Chen WM, Wei GH. 2017. Biogeography and ecological diversity patterns of rare and abundant bacteria in oil‐contaminated soils. Mol Ecol 26:5305–5317. doi: 10.1111/mec.14218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barberán A, Bates ST, Casamayor EO, Fierer N. 2012. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J 6:343–351. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jiao S, Liu ZS, Lin YB, Yang J, Chen WM, Wei GH. 2016. Bacterial communities in oil contaminated soils: biogeography and co-occurrence patterns. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 98:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu AY, Ju F, Hou LY, Li JW, Yang XY, Wang HJ, Mulla SI, Sun Q, Bürgmann H, Yu CP. 2017. Strong impact of anthropogenic contamination on the co‐occurrence patterns of a riverine microbial community. Environ Microbiol 19:4993–5009. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beman JM, Steele JA, Fuhrman JA. 2011. Co-occurrence patterns for abundant marine archaeal and bacterial lineages in the deep chlorophyll maximum of coastal California. ISME J 5:1077–1085. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tian LX, Feng Y, Gao ZJ, Li HQ, Wang BS, Huang Y, Gao XL, Feng BL. 2022. Co-occurrence pattern and community assembly of broomcorn millet rhizosphere microbiomes in a typical agricultural ecosystem. Agric, Ecosyst Environ, Appl Soil Ecol 176:104478. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luo ZM, Liu JX, Zhao PY, Jia T, Li C, Chai BF. 2019. Biogeographic patterns and assembly mechanisms of bacterial communities differ between habitat generalists and specialists across elevational gradients. Front Microbiol 10:169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peng JF, Peng KY, Li JB. 2018. Climate-growth response of Chinese white pine (Pinus armandii) at different age groups in the Baiyunshan National Nature Reserve, central China. Dendrochronologia 49:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2018.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peng KY, Peng JF, Huo JX, Yang L. 2018. Assessing the adaptability of alien (Larix kaempferi) and native (Pinus armandii) tree species at the Baiyunshan Mountain, central China. Ecol Indic 95:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.07.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fu Q, Wang N, Xiao M, Xi JJ, Shao YZ, Jia HR, Chen Y, Yuan ZL, Ye YZ. 2021. Canopy structure and illumination characteristics of different man-made interference communities in Baiyun Mountain National Forest Park. Acta Ecologica Sinica 41. doi: 10.5846/stxb201912202746 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Condit R. 1995. Research in large, long-term tropical forest plots. Trends Ecol Evol 10:18–22. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)88955-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Legendre P, Mi XC, Ren HB, Ma KP, Yu MJ, Sun IF, He FL. 2009. Partitioning beta diversity in a subtropical broad‐leaved forest of China. Ecology 90:663–674. doi: 10.1890/07-1880.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Y, Bao WK, Bongers F, Chen B, Chen GK, Guo K, Jiang MX, Lai JS, Lin DM, Liu CJ, Liu XJ, Liu Y, Mi XC, Tian XJ, Wang XH, Xu WB, Yan JH, Yang B, Zheng YR, Ma KP. 2019. Drivers of tree carbon storage in subtropical forests. Science of The Total Environment 654:684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen Y, Niu S, Li PK. 2017. Stand structure and substrate diversity as two major drivers for bryophyte distribution in a temperate montane ecosystem. Frontiers in Plant Science. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harms KE, Condit R, Hubbell SP, Foster RB. 2001. Habitat associations of trees and shrubs in a 50-ha neotropical forest plot. J Ecology 89:947–959. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-0477.2001.00615.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Valencia R, Foster RB, Villa G, Condit R, Svenning JC, Hernández C, Romoleroux K, Losos E, Magård E, Balslev H. 2004. Tree species distributions and local habitat variation in the Amazon: large forest plot in eastern Ecuador. Journal of Ecology 92:214–229. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00876.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yuan YX, Li XY, Liu FQ. 2024. Differences in soil microbial communities across soil types in China's temperate forests. Forests. doi: 10.3390/f15071110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Han B, Umaña MN, Mi X, Liu X, Chen L, Wang Y, Liang Y, Wei W, Ma K. 2017. The role of transcriptomes linked with responses to light environment on seedling mortality in a subtropical forest, China. Journal of Ecology 105:592–601. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beaudet M, Messier C. 2002. Variation in canopy openness and light transmission following selection cutting in northern hardwood stands: an assessment based on hemispherical photographs. Agric For Meteorol 110:217–228. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1923(01)00289-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dray S, Legendre P, Peres-Neto PR. 2006. Spatial modelling: a comprehensive framework for principal coordinate analysis of neighbour matrices (PCNM). Ecol Modell 196:483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.02.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Han ZM, Zhang Y, An W, Lu JY, Hu JY, Yang M. 2020. Antibiotic resistomes in drinking water sources across a large geographical scale: multiple drivers and co-occurrence with opportunistic bacterial pathogens. Water Res 183:116088. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang NL, Wan SQ, Li LH, Bi J, Zhao MM, Ma KP. 2008. Impacts of urea N addition on soil microbial community in a semi-arid temperate steppe in northern China. Plant Soil 311:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9650-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang J, Wang YF, Cui XY, Xue K, Zhang YM, Yu ZS. 2019. Habitat filtering shapes the differential structure of microbial communities in the Xilingol grassland. Sci Rep 9:19326. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55940-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lin D, Pang M, Fanin N, Wang H, Qian S, Zhao L, Yang Y, Mi X, Ma K. 2019. Correction to: Fungi participate in driving home-field advantage of litter decomposition in a subtropical forest. Plant Soil 444:535–536. doi: 10.1007/s11104-019-04210-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Magoč T, Salzberg SL. 2011. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yao M, Rui J, Niu H, Heděnec P, Li J, He Z, Wang J, Cao W, Li X. 2017. The differentiation of soil bacterial communities along a precipitation and temperature gradient in the eastern Inner Mongolia steppe. CATENA 152:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2017.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Edgar RC. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pandit SN, Kolasa J, Cottenie K. 2009. Contrasts between habitat generalists and specialists: an empirical extension to the basic metacommunity framework. Ecology 90:2253–2262. doi: 10.1890/08-0851.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu WX, Lu HP, Sastri A, Yeh YC, Gong GC, Chou WC, Hsieh CH. 2018. Contrasting the relative importance of species sorting and dispersal limitation in shaping marine bacterial versus protist communities. ISME J 12:485–494. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jiao S, Yang YF, Xu YQ, Zhang J, Lu YH. 2020. Balance between community assembly processes mediates species coexistence in agricultural soil microbiomes across eastern China. ISME J 14:202–216. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0522-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu KS, Yan Q, Guo XZ, Wang WQ, Zhang ZH, Ji MK, Wang F, Liu YQ. 2024. Glacier retreat induces contrasting shifts in bacterial biodiversity patterns in glacial lake water and sediment : bacterial communities in glacial lakes. Microb Ecol 87:128. doi: 10.1007/s00248-024-02447-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang J, Zhang BG, Liu Y, Guo YQ, Shi P, Wei GH. 2018. Distinct large-scale biogeographic patterns of fungal communities in bulk soil and soybean rhizosphere in China. Science of The Total Environment 644:791–800. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu WX, Logares R, Huang BQ, Hsieh CH. 2017. Abundant and rare picoeukaryotic sub‐communities present contrasting patterns in the epipelagic waters of marginal seas in the northwestern Pacific ocean . Environ Microbiol 19:287–300. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Costas-Selas C, Martínez-García S, Logares R, Hernández-Ruiz M, Teira E. 2023. Role of bacterial community composition as a driver of the small-sized phytoplankton community structure in a productive coastal system. Microb Ecol 86:777–794. doi: 10.1007/s00248-022-02125-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang H, Yang ZJ, Wang QC, Wang YL, Hu HW, He JZ, Zheng Y, Yang YS. 2022. Compartment and plant identity shape tree mycobiome in a subtropical forest. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0134722. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01347-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Liu WJ, Shao YZ, Guo SQ. 2025. Latitudinal gradient patterns and driving factors of woody plant fruit types based on multiple forest dynamic monitoring plots. Journal of Plant Ecology. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtaf018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kuiper JJ, van Altena C, de Ruiter PC, van Gerven LPA, Janse JH, Mooij WM. 2015. Food-web stability signals critical transitions in temperate shallow lakes. Nat Commun 6:7727. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sun P, Wang Y, Zhang YF, Logares R, Cheng P, Xu DP, Huang BQ. 2023. From the sunlit to the aphotic zone: assembly mechanisms and co-occurrence patterns of protistan-bacterial microbiotas in the western Pacific ocean. mSystems 8:e0001323. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00013-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lin XZ, Zhang CL, Xie W. 2023. Deterministic processes dominate archaeal community assembly from the Pearl River to the northern South China Sea. Front Microbiol 14:1185436. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1185436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sloan WT, Lunn M, Woodcock S, Head IM, Nee S, Curtis TP. 2006. Quantifying the roles of immigration and chance in shaping prokaryote community structure. Environ Microbiol 8:732–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Östman Ö, Drakare S, Kritzberg ES, Langenheder S, Logue JB, Lindström ES. 2010. Regional invariance among microbial communities. Ecol Lett 13:118–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stone L, Roberts A. 1990. The checkerboard score and species distributions. Oecologia 85:74–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00317345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gotelli NJ, McCabe DJ. 2002. Species co-occurrence: a meta-analysis of J. M. Diamond’s assembly rules model. Ecology 83:2091–2096. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[2091:SCOAMA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Crump BC, Peterson BJ, Raymond PA, Amon RMW, Rinehart A, McClelland JW, Holmes RM. 2009. Circumpolar synchrony in big river bacterioplankton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:21208–21212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906149106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wu BB, Wang P, Devlin AT, She YY, Zhao J, Xia Y, Huang Y, Chen L, Zhang H, Nie MH, Ding MJ. 2022. Anthropogenic intensity-determined assembly and network stability of bacterioplankton communities in the Le’an river. Front Microbiol 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.806036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen Y, Xi JJ, Xiao M, Wang SL, Chen WJ, Liu FQ, Shao YZ, Yuan ZL. 2022. Soil fungal communities show more specificity than bacteria for plant species composition in a temperate forest in China. BMC Microbiol 22:208. doi: 10.1186/s12866-022-02591-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hartvigsen G. 2011. Using R to build and assess network models in biology. Math Model Nat Phenom 6:61–75. doi: 10.1051/mmnp/20116604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chu C, Lutz JA, Král K, Vrška T, Yin X, Myers JA, Abiem I, Alonso A, Bourg N, Burslem DFRP, et al. 2019. Direct and indirect effects of climate on richness drive the latitudinal diversity gradient in forest trees. Ecol Lett 22:245–255. doi: 10.1111/ele.13175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang JJ, Pan FY, Soininen J, Heino J, Shen J. 2016. Nutrient enrichment modifies temperature-biodiversity relationships in large-scale field experiments. Nat Commun 7:13960. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gao XF, Chen HH, Govaert L, Wang WP, Yang J. 2019. Responses of zooplankton body size and community trophic structure to temperature change in a subtropical reservoir. Ecol Evol 9:12544–12555. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zuo J, Liu LM, Xiao P, Xu ZJ, Wilkinson DM, Grossart HP, Chen HH, Yang J. 2023. Patterns of bacterial generalists and specialists in lakes and reservoirs along a latitudinal gradient. Global Ecol Biogeogr 32:2017–2032. doi: 10.1111/geb.13751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bartholomäus A, Genderjahn S, Mangelsdorf K, Schneider B, Zamorano P, Kounaves SP, Schulze-Makuch D, Wagner D. 2024. Inside the Atacama Desert: uncovering the living microbiome of an extreme environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 90:e0144324. doi: 10.1128/aem.01443-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Xu QC, Vandenkoornhuyse P, Li L, Guo JJ, Zhu C, Guo SW, Ling N, Shen QR. 2022. Microbial generalists and specialists differently contribute to the community diversity in farmland soils. J Adv Res 40:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sriswasdi S, Yang CC, Iwasaki W. 2017. Generalist species drive microbial dispersion and evolution. Nat Commun 8:1162. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01265-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wang ZT, Li YZ, Li T, Zhao DQ, Liao YC. 2020. Conservation tillage decreases selection pressure on community assembly in the rhizosphere of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Science of The Total Environment 710:136326. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Nie H, Li C, Jia ZH, Cheng XF, Liu X, Liu QQ, Chen ML, Ding Y, Zhang JC. 2024. Microbial inoculants using spent mushroom substrates as carriers improve soil multifunctionality and plant growth by changing soil microbial community structure. J Environ Manage 370:122726. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Banerjee S, Schlaeppi K, van der Heijden MGA. 2018. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:567–576. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0024-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sysouphanthong P, Thongkantha S, Zhao RL, Soytong K, Hyde KD. 2010. Mushroom diversity in sustainable shade tea forest and the effect of fire damage. Biodivers Conserv 19:1401–1415. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9769-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chen Y, Svenning JC, Wang XY, Cao RF, Yuan ZL, Ye YZ. 2018. Drivers of macrofungi community structure differ between soil and rotten-wood substrates in a temperate mountain forest in China. Front Microbiol 9:37. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yang HW, Li J, Xiao YH, Gu YB, Liu HW, Liang YL, Liu XD, Hu J, Meng DL, Yin HQ. 2017. An integrated insight into the relationship between soil microbial community and tobacco bacterial wilt disease. Front Microbiol 8:2179. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zhou JZ, Kang S, Schadt CW, Garten CT. 2008. Spatial scaling of functional gene diversity across various microbial taxa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:7768–7773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709016105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jones MM, Tuomisto H, Borcard D, Legendre P, Clark DB, Olivas PC. 2008. Explaining variation in tropical plant community composition: influence of environmental and spatial data quality. Oecologia 155:593–604. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0923-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lan GY, Hu YH, Cao M, Zhu H. 2011. Topography related spatial distribution of dominant tree species in a tropical seasonal rain forest in China. For Ecol Manage 262:1507–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.06.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relative abundance at the level of phyla.

Data Availability Statement

All raw read data of 16S genes have been submitted to the NCBI GEO under the accession number PRJNA633088.