Abstract

Background

Hypercalcemia is one of the most common ionic disorders. It is diagnosed when the serum calcium concentration is greater than 10.5 mg/dL. While mainly associated with primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy, it can also be caused by multiple derangements. Almost every part of the body can be affected by excess calcium. Hypercalcemia might be very dangerous and even lethal.

Case presentation

We report a rare trigger of increased serum calcium level - synthol intramuscular injections. A 60-year-old man who suffered from general weakness, weight loss and acute kidney injury, which were associated with unidentified hypercalcemia, was under review for proper diagnosis. We excluded endocrine disorders, malignancies, sarcoidosis, iatrogenic causes, which were defined as medication- related. Patient history, physical examination, blood chemistry, 24-hour urine collection, computed tomography and endoscopy were performed. Finally, the biopsy of muscle explained the source of the increased serum calcium concentrations.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia is a common disorder that has a wide range of triggers. Synthol intramuscular injections are among the causes of elevated serum calcium levels. It is important to make proper and quick diagnoses and begin therapy. Unfortunately, surgical resection of the synthol seems to be the only reasonable option for hypercalcemia treatment.

Keywords: Synthol, Hypercalcemia, Nephrocalcinosis

Background

Hypercalcemia is diagnosed when the serum calcium concentration is greater than 10.5 mg/dL. It is considered mild if the plasma calcium concentration is between 10.5 and 11.9 mg/dL, moderate if the plasma calcium concentration is between 12 and 13.9 mg/dL, and severe if the serum calcium concentration is above 14 mg/dL [1–3]. Up to 99% of total body calcium is stored in the skeleton. Among the 1–2% of calcium that is not stored in bones, half remains ionized in the active form, 40% is bound to proteins such as albumin, and 10% is bound to organic anions [1, 2].

Calcium homeostasis is maintained by parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitriol (1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol) and calcitonin [1–3]. PTH is an amino acid hormone synthesized by the parathyroid glands that is released in response to low serum calcium concentrations. PTH increases the level of serum calcium by enhancing the resorption of bones by osteoclasts, stimulating the reabsorption of calcium in renal tubules, and activating the modification of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol to calcitriol [1, 2]. Calcitriol is a steroid hormone, the active form of vitamin D. Its precursor, after exposure to ultraviolet B radiation, is produced in the skin or delivered in the diet and then hydroxylated first in the liver and finally in the kidneys. Calcitriol increases the absorption of calcium in the intestines [1, 2]. Calcitonin is an amino acid hormone synthesized by the thyroid gland due to high serum calcium levels. It decreases serum calcium concentrations by inhibiting osteoclast activity and promoting renal calcium excretion [1, 2].

The most common causes of hypercalcemia, accounting for approximately 90% of hypercalcemia cases, are primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy; however, increased plasma calcium levels may also be caused by multiple derangements (Table 1) [1, 2, 4–11].

Table 1.

Causes of hypercalcemia

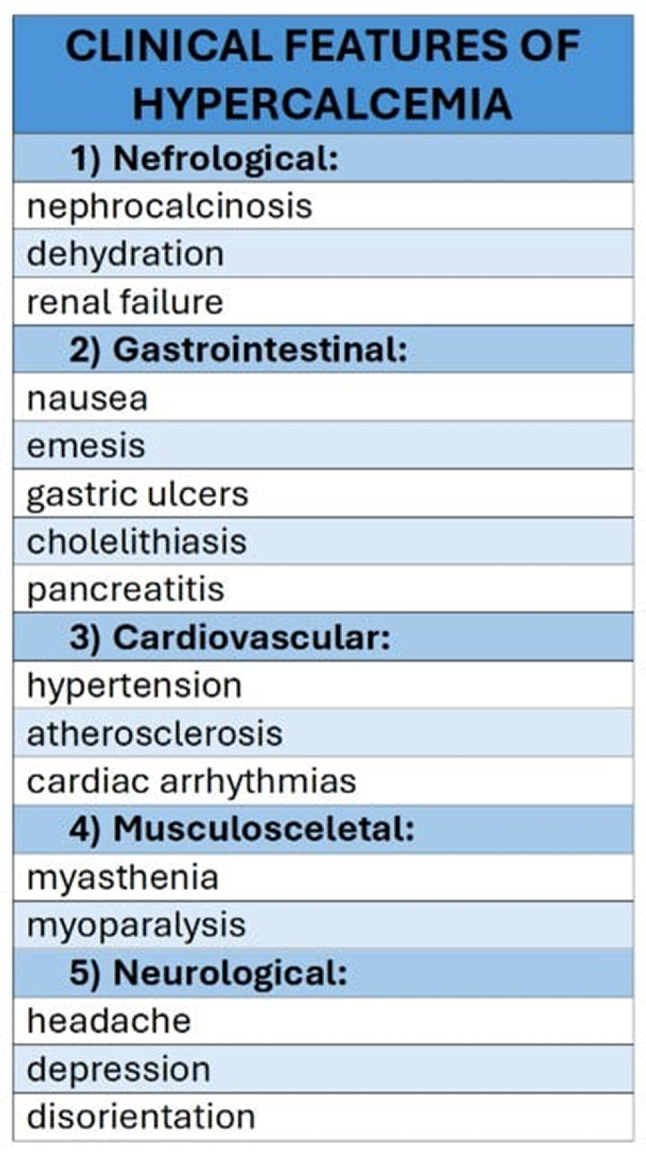

Hypercalcemia impacts different body parts. The digestive system, urinary tract and neurological system are most often affected (Table 2) [1, 2]. Clinical features might be severe or even lethal and trigger of hypercalcemia is not always obvious so we would like to mention about rare cause of increased calcium level.

Table 2.

Clinical features of hypercalcemia

Case presentation

A 60-year-old man with chronic kidney disease, hypertension, nephrocalcinosis and osteoporosis, with a history of nicotine use and a history of intravenous injections into the muscles of the upper limbs and chest thirty years ago, was admitted to the nephrology ward due to an unclear etiology of hypercalcemia. One month before admission, the patient was hospitalized at a municipal hospital. He reported to the emergency department due to weakness, unintentional weight loss (18 kg for 12 months) and vomiting lasting for two days. Laboratory blood tests revealed acute-on-chronic kidney disease with a serum creatinine concentration of 7.64 mg/dL [0.5–0.9 mg/dL] and a plasma urea concentration of 128 mg/dL [15–43 mg/dL] (in earlier blood tests, the serum creatinine concentration was 2.5 mg/dL). Additionally, severe hypercalcemia was detected (serum ionized calcium was 3.61 mmol/L; the reference value in the laboratory was 2.1–2.6 mmol/L). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen revealed calcium deposits in the kidneys, multilevel degenerative changes in the spine and calcifications in the pancreas and stomach. High- resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest revealed bilateral fibrous lesions in the posterior and base parts of the pulmonary lobes and unusual images of the pectoral muscles after synthetic injections (Fig. 1). Laboratory blood tests, such as parathyroid hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), vitamin D and electrophoretic separation of proteins, were performed. The patient was treated with intravenous fluids, furosemide, hydrocortisone and zolendronic acid, and thus, the serum calcium concentration was reduced to 2.52 mmol/L. The patient was advised to take 80 mg of furosemide and 20 mg of hydrocortisone per day for ambulatory oral treatment. However, in the control ambulatory blood tests after 3 weeks, the serum calcium concentration remained elevated at 11,5 mg/dl [8,6–10,2 mg/dL].

Fig. 1.

Pectoral muscles after synthetic injections with deposits of calcium imaged in high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest

When admitted to the nephrology ward, the patient was in fairly good condition. He reported periodic self-limited low back pain, especially in the morning. A detailed history of drugs, vitamins and dietary supplements was taken, which revealed drug therapy: 80 mg furosemide, 20 mg hydrocortisone, 2.5 mg bisoprolol, 4 mg doxazosin, 10 mg lercanidipine and potassium supplementation. The patient was also confirmed to receive unknown intramuscular injections (probably containing testosterone) due to enlarge skeletal muscle mass. He stressed that the last dose of these injections was received 2 years ago. There were no abnormalities on physical examination except for visible muscle deformities within the upper limbs or chest. Laboratory tests revealed increased serum calcium concentrations (11,4 mg/dL, ionized form of calcium 1.46 mmol/l [1.15–1.35]), stable values of plasma creatinine (2,5 mg/dL), normal value of phosphate (3.1 mg/dl [2.6–4.5]) and magnesium (1.9 mg/dl [1.6–2.6]), normal serum albumin (4.4 g/dl [3.9–5.0]), reduced serum parathyroid hormone (3,5 pg/ml; [15–65 pg/ml]), not elevated parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) (< 14 pg/ml [< 14 pg/mL]), normal serum calcitonin (12,5 pg/ml [8,31–14,3 pg/ml]), normal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) (63,3 pg/ml [19,9–79,3 pg/mL]) and suboptimal 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (22 ng/ml [30–50 ng/ml]). Twenty-four-hour urine collection revealed elevated excretion of calcium (414 mg/24 h [100–275 mg/24 h]) and sodium (306 mmol/24 h [40–220 mmol/24 h]), normal excretion of potassium (96 mmol/24 h [25–125 mmol/24 h]), and normal concentrations of oxalate (20 mg/24 h [< 45 mg/24 h}) and citrate (553,5 mg/24 h [> 320 mg/24 h]). We also performed an antibody panel to eliminate systemic diseases; ANA/ENA Western blot, antibodies against double-stranded DNA, and antinuclear antibodies were not detected. Owing to suspected sarcoidosis, the patient was consulted by a pulmonologist, but this diagnosis was excluded. Additionally, gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed, but no abnormalities, including malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract, were found. The patient was also seen by a urologist, but derangement of the urinary system was not found. Radiological examinations revealed that the parts of muscle after intramuscular synthol injections are strongly calcified, suggesting that they may be the source of increased serum calcium concentrations. The decision to perform a muscle biopsy was made. Histologically, muscle cells filled with silicon-like material without epithelial atypia and with large deposits of calcium were found. With no evidence of other reasons for hypercalcemia, we determined that intramuscular synthol injections caused a not yet well-known body reaction in muscle tissue because of calcium storage and calcium release, which resulted in hypercalcemia.

Discussion and conclusions

Although the current literature reports only two cases of hypercalcemia caused by synthol injections [12, 13] and the mechanism is still unclear, the history of our patient is the next evidence supporting this hypothesis. The patient underwent many tests and examinations to diagnose numerous known causes of hypercalcemia, which were excluded. However, the results of the histopathological examination of the muscle biopsy revealed that intramuscular synthol injections may result in hypercalcemia during long-term observation.

Synthol is one of the site enhancement oils. It consists of 85% oil, 7.5% lidocaine, and 7.5% alcohol [14]. Its intramuscular injections, which are used by bodybuilders to improve muscle appearance and increase muscle mass, may cause numerous complications, such as pain after injection, deformities of muscles, chronic wounds, ulceration and muscle fibrosis [15–17]. They usually appear directly or shortly after injection. However, hypercalcemia can be detected many years after this procedure [17, 18]. This may be the probable reason why this cause of hypercalcemia has rarely been examined and reported. Apparently, the mechanism of hypercalcemia is similar to that after free silicone use—fibrosclerous and granulomatous reactions to a foreign body. Inflammation with formation of granulomas has been observed also after subcutaneous paraffin oil injections [17–19]. As mentioned previously, granulomatosis is one of the leading causes of hypercalcemia due to increased synthesis of calcitriol in granulomas, which are formed by overreactive macrophages [12, 13, 18, 19]. Calcitriol is often elevated, whereas 25-hydroxyvitamin D is usually normal or even below normal range [20, 21]. However, it is not mandatory; sometimes, as in our case, the patient’s serum calcitriol level was within the normal range.

Importantly, the implemented intravenous and oral treatment decreased the serum calcium concentration only temporarily, and hypercalcemia recurred. Surgical resection of the synthol seems to be the only reasonable option for hypercalcemia treatment [14]. Chiri revealed that 3 months after surgical removal, serum calcium concentrations decrease to reference values [13].

Hypercalcemia is a common disorder that has numerous etiologies, and if it is not properly and quickly diagnosed and treated, it may cause severe complications, including death. Synthol intramuscular injections are among the causes of elevated serum calcium levels.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PTH

Parathyroid hormone

- PHPT

Primary hyperparathyroidism

- CT

Computed tomography

- HRCT

High-resolution computed tomography

- TSH

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- PTHrP

Parathyroid hormone-related protein

- ANA/ENA

Antinuclear antibody/extractable nuclear antigen antibodies

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

Author contributions

MM analyzed and interpreted all examinations, wrote discussion and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. ZM was responsible for graphics and background. KR and SN were responsible for [content-related supervision] (https://www.diki.pl/slownik-angielskiego?q=content-related+supervision). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959–66. PMID: 12751658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonon CR, Silva TAAL, Pereira FWL, Queiroz DAR, Junior ELF, Martins D, Azevedo PS, Okoshi MP, Zornoff LAM, de Paiva SAR, Minicucci MF, Polegato BF. A review of current clinical concepts in the pathophysiology, etiology, diagnosis, and management of hypercalcemia. Med Sci Monit. 2022;28:e935821. 10.12659/MSM.935821. PMID: 35217631; PMCID: PMC8889795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang WT, Radin B, McCurdy MT. Calcium, magnesium, and phosphate abnormalities in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(2):349 – 66. 10.1016/j.emc.2013.12.006. Epub 2014 Feb 19. PMID: 24766937. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Turner JJO. Hypercalcaemia - presentation and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(3):270–3. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-3-270. PMID: 28572230; PMCID: PMC6297576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palumbo VD, Palumbo VD, Damiano G, Messina M, Fazzotta S, Lo Monte G, Lo Monte AI. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism: a review. Clin Ter. 2021;172(3):241–246. 10.7417/CT.2021.2322. PMID: 33956045. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Magacha HM, Parvez MA, Vedantam V, Makahleh L, Vedantam N. Unexplained hypercalcemia: a clue to adrenal insufficiency. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42405. 10.7759/cureus.42405. PMID: 37637567; PMCID: PMC10447631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxon HR, Apple DJ, Goldsmith RE. Hypercalcemia in thyrotoxicosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147(5):694-6. PMID: 715646. [PubMed]

- 8.Shi S, Zhang L, Yu Y, Wang C, Li J. Acromegaly and non-parathyroid hormone-dependent hypercalcemia: a case report and literature review. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21(1):90. 10.1186/s12902-021-00756-z. PMID: 33933067; PMCID: PMC8088721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goltzman D, Approach to H. 2023 Apr 17. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–. PMID: 25905352.

- 10.Martin TJ, Grill V. Hypercalcemia in cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;43(1–3):123-9. 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90196-p. PMID: 1525053. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Goltzman D. Nonparathyroid Hypercalcemia. Front Horm Res. 2019;51:77–90. 10.1159/000491040. Epub 2018 Nov 19. PMID: 30641526. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Alimoradi M, Chahal A, El-Rassi E, Daher K, Sakr G. Synthol systemic complications: hypercalcemia and pulmonary granulomatosis: a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;69:102771. 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102771. PMID: 34522373; PMCID: PMC8426527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rami Chiri K, Gabriel D, Chelala H, Azar, MP016 hypercalcemia and nephrocalcinosis induced by “pump and pose” intramuscular injection. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(suppl_3):iii434. 10.1093/ndt/gfx160.MP016

- 14.Nassar A, Osseis M, Sleilati F, Nasr M, Abou Zeid S. Management of Synthol-induced fibrosis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12(12):e6391. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000006391. PMID: 39687419; PMCID: PMC11649267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikander P, Nielsen AM, Sørensen JA. Injektion af synthololie hos bodybuilder gav kroniske sår og deformerende ar [Injection of synthol in a bodybuilder can cause chronic wounds and ulceration]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177(20):V12140642. Danish. PMID: 25967249. [PubMed]

- 16.Ghandourah S, Hofer MJ, Kießling A, El-Zayat B, Schofer MD. Painful muscle fibrosis following synthol injections in a bodybuilder: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:248. 10.1186/1752-1947-6-248. PMID: 22905749; PMCID: PMC3459719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sisti A, Huayllani MT, Restrepo DJ, Boczar D, Manrique OJ, Broer PN, Shapiro SA, Forte AJ. Oil injection for cosmetic enhancement of the upper extremities: a case report and review of literature. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3):e2020082. 10.23750/abm.v91i3.8533. PMID: 32921778; PMCID: PMC7716972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sølling ASK, Tougaard BG, Harsløf T, Langdahl B, Brockstedt HK, Byg KE, Ivarsen P, Ystrøm IK, Mose FH, Isaksson GL, Hansen MSS, Nagarajah S, Ejersted C, Bendstrup E, Rejnmark L. Non-parathyroid hypercalcemia associated with paraffin oil injection in 12 younger male bodybuilders: a case series. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(6):K29–37. 10.1530/EJE-18-0051. Epub 2018 Mar 29. PMID: 29599408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gyldenløve M, Rørvig S, Skov L, Hansen D. Severe hypercalcaemia, nephrocalcinosis, and multiple paraffinomas caused by paraffin oil injections in a young bodybuilder. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2098. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60806-0. PMID: 24931692. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Tachamo N, Donato A, Timilsina B, Nazir S, Lohani S, Dhital R, Basnet S. Hypercalcemia associated with cosmetic injections: a systematic review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(4):425–30. 10.1530/EJE-17-0938. Epub 2018 Feb 16. PMID: 29453201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldrup E, Theilade S, Lorenzen M, Andreassen CH, Poulsen KH, Nielsen JE, Hansen D, El Fassi D, Berg JO, Bagi P, Jørgensen A, Blomberg Jensen M. Hypercalcemia after cosmetic oil injections: unraveling etiology, pathogenesis, and severity. J Bone Min Res. 2021;36(2):322–33. 10.1002/jbmr.4179. Epub 2020 Oct 13. PMID: 32931047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.