Abstract

Background

Pseudostellaria heterophylla, a member of the Caryophyllaceae family, is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine due to its bioactive cyclic peptides (CPs) with immunomodulatory functions. Caryophyllaceae- like CPs, one of the largest types plant-derived CPs, typically consist of 5–12 amino acids and are derived from ribosomally synthesized peptide precursors. The diversity of CPs arises from variations in their core peptide sequences. However, the precursor genes responsible for Caryophyllaceae-like CPs biosynthesis in P. heterophylla remain largely uncharacterized.

Results

In this study, barcoding PCR combined with high-throughput sequencing was used to efficiently genotype precursor genes encoding CPs in P. heterophylla. This approach enabled the identification of known and novel precursor genes, including prePhHB_1, prePhHB_2, prePhPE and prePhPN. The core peptide regions showed high variability, while the leader and follower regions were relatively conserved, with a few nucleotide mutations. Tissue-specific expression analysis revealed that prePhHB was predominantly expressed in the phloem and fibrous roots, while prePhPE was specifically expressed in the xylem. prePhPN exhibited low expression level and was mainly detected in the phloem and stem. Moreover, the expression of these precursor genes was responsive to abscisic acid and nitrogen stress. RNA in situ hybridization revealed that prePhPE transcripts were primarily localized in the xylem and phellem of the roots. Transient co-expression in Nicotiana benthamiana indicated that prePhPE is involved in the biosynthesis of Pseudostellarin E (PE).

Conclusions

Barcoding PCR combined with high-throughput sequencing provides an effective strategy for investigating CP precursor genes, including those with low expression. The results reveal conserved features in CP precursor genes and highlight a previously unrecognized mechanism contributing to CP diversity. The prePhPE gene was identified as the precursor gene of PE, which accumulates mainly in the xylem of P. heterophylla roots. prePhPN may be a precursor gene for a novel CP.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-06972-2.

Keywords: Pseudostellaria heterophylla, Precursor gene, PrePhPE, Pseudostellarin E biosynthesis, High-throughput sequencing

Background

Cyclic peptides (CPs), a diverse class of natural products, widely distributed in plants [1–3]. Many CPs have great biological activities, including estrogenic, vasorelaxant, antimicrobial, and immunosuppressive activities [4–6]. Notably, their antifungal activities are considered environmentally safe and pose minimal risks to human health [7, 8]. To date, approximately 500 CPs have been identified from over 120 plant species spanning 26 families, with the Caryophyllaceae and Rhamnaceae families being particularly enriched in CPs. These CPs have been classified into 8 types, among which Caryophyllaceae-like CPs represent one of the largest types. More than 190 Caryophyllaceae-like CPs have been reported in vascular plants [9, 10]. Caryophyllaceae-like CPs typically consist of 2 or 5–12 amino acids cyclized via peptide bonds, forming a single ring. These compounds are prevalent in various flowering plants, especially species of the Caryophyllaceae family such as Pseudostellaria heterophylla [9]. The roots of P. heterophylla are valuable in traditional Chinese medicine as a tonic for treating fatigue, spleen asthenia, and anorexia [11, 12]. This species is rich in Caryophyllaceae-like CPs, including pseudostellarin A–H and heterophyllin A–H [13–15]. A novel CP, pseudostellarin K, was recently isolated from its fibrous roots [16]. Many of these compounds exhibit biological functions, such as tyrosinase inhibitory activity, melanin formation inhibitory activities, and cancer cytotoxicity [17–19]. However, the generally low abundance of CPs in Caryophysiaceae species poses a challenge for their utilization and development. Thus, elucidating the biosynthetic pathway of the Caryophyllaceae- like CPs is essential for enhancing their production in P. heterophylla.

Two biosynthetic pathways have been proposed for Caryophyllaceae-like CPs. One involves non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), which assemble peptides independently of ribosomal machinery [20]. Alternatively, a ribosome-dependent pathway involves in the formation of linear precursor peptides encoded by mRNA. This ribosomal mechanism has been reported in plant species such as Petunia hybrida, Saponaria vaccaria, and P. heterophylla [4, 21]. Typically, CP precursor peptides comprise an N-terminal leader peptide, a variable core peptide, and a C-terminal follower peptide. While the leader and follower peptides often contain conserved recognition motifs, the core region is highly variable [2]. Maturation of CPs requires enzymatic cleavage at the N- and C-termini of the precursor, followed by cyclization [4, 22, 23]. The enzymes recognize the leader and follower peptides, and exhibit high tolerance for variation in the core peptides, resulting in the production of diverse CPs. Therefore, identifying CP precursor gene is crucial for understanding the biosynthesis of Caryophyllaceae-like CP.

The sequences of precursor peptides genes have been identified in several plant families, including Rutaceae, Linaceae, and Euphorbiaceae, based on genomic and transcriptomic data [24]. For instance, the Citrus clementina genomes contain 100–150 small cyclic amphipathic peptides genes encoding small ~ 50 amino acid precursor proteins that are post-translationally processed into CPs consisting of 5–10 amino acids [25]. In flax (Linum usitatissimum), five conserved sites were used to identify the potential diversity of cyclic peptides based on the flax genome and whole protein sequence, leading to the discovery of various precursor peptides [24, 26]. In the Caryophyllaceae family, precursor gene information has largely been derived from expressed sequence tag (EST) libraries, as no genome databases are currently available. For example, a precursor gene of CP segetalin A was identified in transformed Saponaria vaccaria roots, which catalyzed the biosynthesis of segetalin A [2]. In P. heterophylla, the precursor gene prePhHB and PrePhHA has been shown to encode the precursor peptides of Heterophyllin B (HB) and Heterophyllin A (HA), respectively [27, 28]. Although at least 17 CPs have been reported in P. heterophylla, the majority of precursor genes remain unknown. The highly conserved sequence in precursor genes present challenges for its cloning and identification. Thus, efficient identification of linear precursor peptides and their encoding genes is critical to elucidating the CP biosynthesis pathway in P. heterophylla.

High-throughput sequencing provides a powerful approach for identifying gene sequences from PCR products amplified using primers targeting conserved regions [29, 30]. High-throughput tracking of mutations (Hi-TOM) has been widely used in the high-throughput identification of mutations induced by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas systems, which resemble the core sequence of CP precursor genes. Hence, high-throughput sequencing is an effective method for discovering CP precursor genes, and enhancing our understanding of CPs biosynthetic in P. heterophylla.

In this study, we aimed to identify precursor genes involved in CP biosynthesis in P. heterophylla. Conserved primers were designed according to the prePhHB gene, and cDNA from different tissues of P. heterophylla were used for PCR amplification followed by high-throughput sequencing. We report the discovery of novel CP precursor genes and provide functional evidence supporting their involvement in the ribosome-dependent biosynthesis of Caryophyllaceae-like CPs in P. heterophylla.

Results

Barcoding PCR with high-throughput sequencing to detect Cyclic peptide precursor genes

A high-throughput sequencing strategy was used to comprehensively screen for cyclic peptide precursor genes across all tissues of P. heterophylla. PCR products were mixed to construct a DNA library and sequenced with paired-end 150 bp reads. A total of 47,056 unique reads were obtained, among which more than 17,000 reads matched well with the prePhHB sequence, a known precursor gene of the cyclic peptide HB [27]. Sequence variation were detected in the precursor peptide sequence, leading to the classification of the reads into 5 types, named prePhHB, prePhHB_1, prePhHB_2, prePhPE and prePhPN. These were assembled into 3 types cyclic peptides (CPs) types: HB, PE and a novel CP without chemical analysis determination. Among the 5 type precursor peptide sequences, only ATT/GTT and GAG/TTACGT variants were present in N-terminal leader peptide sequences, while variants of GAGCTG/GTGCTG/GTGATG and GGA/GGG were present in the C-terminal follower peptide sequences. The core peptide regions showed substantial sequence divergence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Nucleotide sequence alignment of putative cyclic peptide precursor genes identified from barcode sequence of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. These precursor genes encoded the precursor peptides of 3 different CPs: PE, HB, and PN. Red frame represents the variation of the nucleotide sequence. Blue frame indicates a nonsense mutation. The conserved sequences are visualized

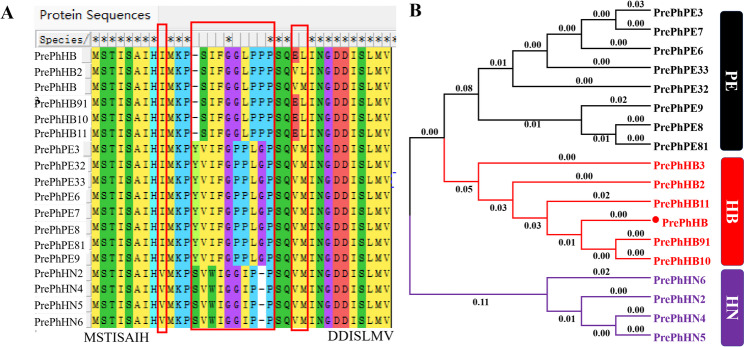

Phylogenetic analysis of precursor peptide genes

To explore the evolutionary relationships and structural conservation among the precursor genes in P. heterophylla, the peptide amino acid sequences were aligned and analyzed (Fig. 2A). Major differences were observed in the 8–9 amino acid residues within the core peptide region. Minor variations such as I/V and PS/PY variants, were present in the N-terminal leader peptide. Variants of EL/VL/VM were present in the C-terminal follower peptide. Seventeen sequences were highly homologous with prePhHB. Phylogenetic tree showed that 5 types and prePhHB were highly homologous, followed by PrePhPE. In contrast, PrePhHN shared low similarity with other precursor types, indicating that it may represent a novel type of CP precursor gene (Fig. 2B). The conserved and variable regions suggest a novel mechanism for the evolution of precursor gene diversity.

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequence analysis of precursor genes from P. heterophylla. A Conserved and variation regions of precursor peptides, with red frame indicating amino acid variation. B Phylogenetic analyses of precursor peptides detected from P. heterophylla. Black lines represent precursor peptides of PE, red line represents precursor peptides of HB, and the purple lines represent precursor peptides of PN

Multiple comparisons found that the 5 types of peptide precursors could be classified based on 3 structural features: leader, core, and follower peptides. This structure is consistent with the structure of Caryophyllaceae-like CPs (Fig. 3). The leader peptide was highly conserved, with variations of IMKPS, IMKPY, and VMKPS. PrePhPE had the specific leading peptide of IMKPY. Follower peptides were varied, including EL, VL, and VM, suggesting that at least 3 genes encode HB-type CP precursors. The PrePhHB sequence was consistent with the previous study [27]. While PrePhHB_1 and PrePhHB_2 represented novel variants. The unknown precursor prePhPN was predicted to encode a core sequence of VWIGGIPP. All the peptide precursors had a terminal proline in the mature peptide, thus qualifying them as proline-rich cyclic peptides.

Fig. 3.

Visualization of three clade precursor peptides from P. heterophylla. Red letters indicate conserved C-terminal residues. Purple letters indicate mutated amino acids in the follower region of HB-type peptides. And 3 genes encode precursors peptide of HB, including PrePhHB, PrePhHB_1 and PrePhHB_2. One precursor gene was detected for encoding precursors peptide of PE and HN, respectively. Blue letters indicate amino acids variations in the leader peptide region

Expression patterns of precursor peptide genes in different tissues

To investigate the function of precursor genes in P. heterophylla, gene expression was detected in different tissues (roots, phloem, xylem, leaf, fibrous roots, and stem). prePhHB was dominantly expressed in the phloem and fibrous roots, with transcript levels more than 5-fold higher than in other tissues (Fig. 4A). prePhPE showed tissue-specific expression in the xylem, and its expression was over 100 times higher than that in the other tissues (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the expression of prePhPN was low in all P. heterophylla tissues (Fig. 4C), which may contribute to the undetectable levels of the corresponding CP in this study.

Fig. 4.

Expression analysis of three precursor genes in different tissues of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. The relative expression levels of prePhHB (A), prePhPE (B), and prePhHN (C) in roots, phloem, xylem, leaf, fibrous roots, stem, and leaf. All data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences by multiple comparisons using SPSS Statistics

Abiotic stress, particularly nitrogen stress, regulated precursor gene expression in P. heterophylla [31]. qRT-PCR analysis indicated that the expression of prePhHB and prePhHN was downregulated under prolonged ammonia nitrogen treatment and upregulated in response to nitrate compared with nitrogen deficiency. The expression of prePhPE and prePhHN was upregulated under short-term ammonia nitrogen treatment (Figure S1A–C). In addition, both PrePhHB, PrePhPE was induced by abscisic acid (ABA) treatment in a time-dependent manner, whereas PrePhHN expression was decreased by ABA treatment (Figure S1D–F). These results indicate that the three precursor peptide genes expression was regulated by abiotic stress.

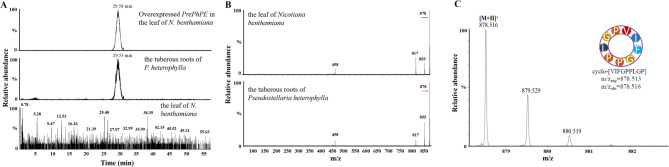

Detection of PE in P. heterophylla roots and prePhPE-overexpressing Nicotiana benthamiana

To study the localization of prePhPE, RNA in situ hybridization was conducted in P. heterophylla roots and stems. Strong hybridization signals were observed in the xylem and phellem, with weaker expression in the cambium, phloem, and rays composed of parenchyma cells (Fig. 5A). In stems, prePhPE was also expressed in the phellem, cortex and xylem. It was weakly expressed in cambium and phloem (Fig. 5B). We thus propose that PE was mainly biosynthesized and accumulated in the xylem cells.

Fig. 5.

In situ hybridization localization of prePhPE in P. heterophylla. A In root, the expression of prePhPE was detected in the xylem and phellem, while weak signals were observed in the cambium, phloem, and rays. (ii) showd hybridization in root using the prePhPE sense probe. Scale bars are 1000 μm (i), 200 μm (ii, iii), and 100 μm (iv). B In stem, the expression of prePhPE was localized to the phellem, cortex and xylem. Scale bars are 100 μm (i), 100 μm (ii). ii, the hybridization in stem using the prePhPE sense probe

To verify the function of the precursor gene, prePhPE was overexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves, producing a compound with a [M + H]+ m/z value of 878.516 (Figure S2). This product exhibited a mass spectral peak similar to that detected in P. heterophylla tuberous roots (Fig. 6A), where a similar compound ([M + H]+ m/z 878.517) generated secondary fragments at m/z 855.433, 817.457, and 458.731 (Fig. 6B). The theoretical molecular weight of PE (C45H67N9O9) was highly consistent with the observed m/z value of 878.516 in prePhPE-overexpressing N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that PE was biosynthesized by overexpressing prePhPE, identifying it as a precursor gene essential for PE biosynthesis.

Fig. 6.

Transient expression of prePhPE in tobacco cells leads to PE biosynthesis. A Extracted ion chromatogram trace of prePhPE overexpression in tobacco with a mass spectra peak at a [M + H]+ m/z value of 878.516. B Extracted ion chromatogram trace of prePhPE overexpression in tobacco and P. heterophylla tuberous roots. (C) MS data extracted at retention times 28.82- and 28.83-min. Cyclic peptides were detected by UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS in both P. heterophylla and tobacco, with peaks marked by retention time (RT) and measured molecular weight (MW)

Discussion

Cyclic peptides are low in content but important bioactive compounds in plants. Elucidation of the CP biosynthesis pathway promotes its utilization. Given the support for CP biosynthesis from ribosome-generated precursors in P. heterophylla, it was important to research the precursor genes to illustrate CP biosynthesis pathways. To identify the precursor genes encoding CPs, barcoding PCR with high-throughput sequencing was conducted in P. heterophylla. Ultimately, novel peptide precursor genes were identified, and their gene function was investigated.

Barcoding PCR combined with high-throughput sequencing was an effective method for precursor gene identification

Previous research has indicated that Caryophyllaceae-like CPs are commonly found in Caryophyllaceae species, such as P. heterophylla. And they are derived from ribosomally synthesized precursor peptides, including precursor peptides with leader, core, and follower peptides. In addition, the leader and follower peptides of the precursor peptides have similar sequence with known precursor peptides from P. heterophylla, S. vaccaria, and Galerina marginate [2, 24, 32]. Although some precursor sequences have been identified from the genome or transcriptome database [33, 34]. Many precursor genes encoding precursor peptides of CPs are too short to be filtered out in the transcriptome database. Most plants, including P. heterophylla, do not yet have a complete reference genome, which leads to difficulties in the study of precursor genes. Therefore, it is important to develop new methods for identifying precursor genes.

NGS and Hi-TOM enable the accurate quantification and visualization of sequence variations [30]. Here, we developed a systematic strategy for the construction of an NGS library to identify precursor peptide sequences. Degenerate primers containing barcodes enabled the amplification of diverse precursor genes, including low-abundance transcripts (Fig. 4). The variations in the leader, core, and follower peptides were observed (Fig. 3), demonstrating the method’s sensitivity and specificity. Compared with Sanger sequencing, this high-throughput approach enables parallel analysis of hundreds of samples, providing both cost-effectiveness and scalability.

The expression of CP precursor genes were regulated by environmental factors

Some peptides are enriched within regions associated with phenotypic variations and domestication selection, contributing to the genetic regulation of complex traits and domestication [35, 36]. Previous research indicated that the HB content was significantly varied among cultivated P. heterophylla from different areas, largely due to mutations in the prePhHB gene [27]. Both ecological environment and germplasm genetic factors play an important role in the mutations, which are associated with genetic regulation and domestication selection. Variations in core peptides resulted in the production different CPs, and sequence variations were also observed in precursor genes encoding the same CPs (Figs. 1 and 2). Thus, the variations in precursor genes may relate to the domestication selection of P. heterophylla.

The balance between plant growth and stress responses is a major physiological challenge for plants surviving in dynamic environments. Plant peptides are involved in regulating homeostasis [37, 38]. In this study, the CP precursor genes were expressed at a significantly high level in the different parts of the roots, exhibited varied expression patterns in response to ABA, and were significantly induced by nitrogen stress (Figure S1). It was demonstrated that over-expression of the nitrate and ammonium regulated peptide transporter OsNPF7.3 increases grain yield in rice [39]. Peptide transporter OsNPF8.1 is important for plant tissues to enhance redistribution of organic nitrogen (N), contributing to balance plant growth and tolerate N deficiency [40]. DNF4 gene, encodes the cysteine-rich peptide NCR211, plays a critical role in the function of differentiated rhizobia and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in Medicago truncatula, which actively convert nitrogen into ammonia for the synthesis of amino acids [41]. Peptides promote nitrogen uptake and utilization by plants. In addition, peptide gene was induced by ABA and enhanced plant resistance to drought stress [42, 43]. Peptides play important roles in plant development and responses to abiotic stresses. RNA in situ hybridization showed that prePhPE was expressed in the xylem and phellem, which had lignification and suberification (Fig. 5). Hence, abiotic stress factors may regulate the expression of precursor genes and affect CP biosynthesis, playing important roles in drought resistance as well as nitrogen uptake and utilization in P. heterophylla.

The expression of precursor genes affected CP biosynthesis

Previous research revealed that the production of CP kalata B1 was significantly increased by the overexpression of its precursor peptide gene in N. benthamiana leaves [44]. Asparaginyl endopeptidases (AEP) facilitate the biosynthesis of kalata B1 by catalyzing peptide cyclization [45]. Similarly, the overexpression of the L. chinense precursor peptide gene (LbaLycA) in N. benthamiana leaves increased the production of CP Lyciumins A, B, and D, which were absent in wild-type tobacco [46]. The precursors were cleaved by a prolyl oligopeptidase to generate linear intermediates, and the serine protease peptide cyclase removed the C-terminal propeptide and catalyzed cyclisation, giving mature CPs [8]. The precursor genes directly affected the CP production. Enzymes catalyzing the formation of CPs, whose function was conserved, exist in N. benthamiana leaves. Thus, precursor genes are essential and most important for CP biosynthesis.

In this study, we isolated CP precursor genes from P. heterophylla using a barcoding PCR combined with high-throughput sequencing, and functionally characterized them through transient co-expression in N. benthamiana. In particular, PE was biosynthesized by overexpression of precursor gene prePhPE in N. benthamiana (Fig. 6). These results suggest that prePhPE plays an important role in PE biosynthesis. Further research is required to characterize the enzymes that catalyze the linearization and cyclization of precursor peptides.

Conclusions

In this study, a novel CP precursor gene, prePhPE, was identified in P. heterophylla, which encoded a precursor peptide that had conservative amino acid residues at both the N-terminus and C-terminus of the core peptide. prePhPE was specifically expressed in the xylem and was induced by nitrogen stress and ABA. Functional analysis confirmed that prePhPE encoded precursor peptides involved in PE biosynthesis. In addition, prePhPN was identified as a potential novel peptide precursor gene. Taken together with previous knowledge and results from this study, we further propose that the biosynthetic pathway of CPs in P. heterophylla could be divided into three steps, including transcription, translation of precursor genes, and post-translational modifications of these synthesized precursor peptides (Fig. 7). These studies provide a foundation for further investigation of the CP biosynthetic pathway in P. heterophylla.

Fig. 7.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of cyclic peptides in P. heterophylla. The precursor peptide of CPs was encoded by specific precursor genes in P. heterophylla, which were cleaved to form linear intermediates. Subsequent removal of the C-terminal region obtained the core peptide, followed by cyclization to generate mature CPs. The expression of precursor genes were in response to ABA and nitrogen

Methods

Plant materials

The seeds of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax were sown and propagated by tuberous root in an experimental field at Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Guiyang, China). Tissues from mature P. heterophylla plants, propagated by tuberous root for approximately 6 months, including the phloem, xylem, leaves, roots, fibrous roots, and stems, were collected to analyze the expression levels of precursor genes [47]. Roots and stems were used for in situ hybridization analysis. Seedlings derived from seed germination were cultured in half-strength Murashige and Skoog (½MS) medium for 3 months until the roots bulged. Then, seedlings were transferred to MS medium supplemented with 20 µM ABA for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. In addition, remaining seedlings were cultured in nitrogen deficient medium (CK), 10 mM ammonium nitrogen medium (NH), and 10 mM nitrate nitrogen medium (NO) under 16 h light/8 h dark conditions at 25 °C for 12 h and 4 months [31]. All seedlings were grown in culture flasks of 10 plants per bottle, with at least five bottles per treatment. Root samples were immediately washed with sterile water, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until RNA extraction.

Barcoding PCR combined with high-throughput sequencing

Primers for the conserved region were designed according to the conserved sequence of the cyclic peptide precursor gene prePhHB (5’-ATGTCTACTATTTCAGCCATCCAC-3’, 5’-TTACACCATGAGGGAAATATCATC-3’) [27]. PCR amplification was performed using barcode-labeled primers, with templates derived from root, stem, leaves, flowers, and seeds of P. heterophylla. All PCR products were mixed in an equal nanomolar concentration in one sample for DNA library construction, which was performed using the Illumina HiSeq 3000 system with paired-end 150 bp reads (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Raw data from high-throughput sequencing were processed by trimming adapters. Unique reads were obtained by omitting replicated reads. Sequence reads for genotyping sequences were sorted with and a Perl script to identify candidate peptide precursor genes [29].

Vector construction

To validate the candidate peptide precursors identified through barcoding PCR combined with high-throughput sequences of P. heterophylla, the PCR products were cloned into the pMD™ 18-T vector using a Cloning Kit (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). The prePhPE sequence was constructed into the pCAMBIA3301 vectors via recombination reactions. The prePhPE-pCAMBIA3301 vector was used for prePhPE overexpression in N. benthamiana leaves.

prePhPE overexpression in N. benthamiana

For overexpression analysis, the prePhPE-pCAMBIA3301 vector was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and infected N. benthamiana leaves. Three days after infection, the leaves were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Amino acid sequences were aligned using MEGA 11 software, and phylogenetic trees were constructed via the neighbor-joining tree method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Conserved sequence motifs were visualized using TBtools software [48].

qRT-PCR analysis

The expression patterns of precursor genes were validated by qRT-PCR. Primers were designed during a non-conserved sequence using Primer Premier 5.0 and synthesized commercially (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S1. Total RNA was extracted using Eastep® Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega, Madison, WI USA). cDNA was then synthesized by M-MLV reverse transcriptase (RNase H-) (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed using a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) with at least three independent biological replicates. PhACT2 (KT363848) was used as the internal control [27]. Multiple comparisons were performed using SPSS Statistics 26.0 software.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

Fresh mature roots of P. heterophylla were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (DEPC.H2O; Servicebio, Wuhan, China) for 12 h. Paraffin sectioning and hybridization were performed as described previously [49]. NBT/BCIP solution was added to observe those positive for gene expression. The oligonucleotide probe was synthesized using Digoxigenin (DIG) labeling. The probe sequence was as follows: CCTTACGTTATTTTTGGACCACCTCTTGGT. The hybridization of sense probe was used as control.

Extraction of cyclic peptides in P. heterophylla and N. benthamiana

CPs were extracted as described previously [27]. Approximately 2 g of tuberous roots of P. heterophylla and leaves of N. benthamiana (prePhPE-overexpressing line and wild type) was ground into powder and ultrasonicated in 50 mL of methanol for 45 min. Then, 25 mL of the methanol filtrate was evaporated at 100 °C, re-dissolved in 5 mL of methanol, and filtered through a syringeless filter (0.22 μm, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The resulting solution was analyzed using LC-MS and UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS.

LC-MS and HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS analysis

LC-MS was performed on a Thermo Scientific TSQ Quantum Access MAX Mass Spectrometer coupled with an Accela UHPLC system (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA), following the methods previously described [27]. UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS analysis was conducted on a Xevo G2 QTof mass spectrometer with a Waters ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, MA, USA). Analytes were separated on an ACQUITY UPLC BEHC18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) maintained at 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (100% acetonitrile) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in water). The gradient conditions were as follows: 0–5.0 min, 15% A; 5.0–15 min, 25% A; 15–25 min, 30% A; 25–40 min, 35% A; 40–50 min, 35% A; and 50–60 min, 10% A. The flow rate was set at 0.30 mL/min.

The Xevo G2 QToF mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode. The instrumental parameters were set as follows: capillary voltage of 3.0 kV; cone voltage of 30 V; source temperature of 110 °C; desolvation temperature of 600 °C; cone gas flow rate at 30 L/h; and desolvation gas flow rate at 800 L/h. The collision energy was set at 10–40 eV. Nitrogen was used as the cone gas and desolvation gas. A mass range was scanned from 50 to 1600 m/z. The Q-TOF acquisition rate was 0.2 s, and the inter-scan delay was 0.1 s. For the extraction ion analysis, the deprotonated molecular ion at 878.513 m/z for PE was selected as the extraction ion. The data were collected and acquired using MassLynx V4.1 software, and MassLynx software was used to manually process each chromatogram and mass spectrum.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Zhonghua Chen (School of Science, Western Sydney University) for modifying the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CP

cyclic peptide

- PE

Pseudostellarin E

- HB

Heterophyllin B

- Hi-TOM

High-throughput tracking of mutations

- NGS

Next-generation sequencingtechnology

- MS

Murashige & Skoog

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- BCIP

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate

- NBT

Nitroblue tetrazolium

- LC-MS

Liquid Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- Q-TOF

Quadrupole-Time of Flight

- DEPC

Diethyl pyrocarbonate

- AEP

Asparaginyl endopeptidases

Authors’ contributions

J.X., and L.G. T.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. J.X. and W.Z. performed the experiments and analysed the data. J.X. and T.Z. wrote and revised the manuscript. X.O., H. H. revised the manuscript. C.X., C.Y., G.S. assisted in the determination of CPs content.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3503803), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82160728, 82160716).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jiao Xu, Email: xujiao2008mzk@163.com.

Tao Zhou, Email: taozhou88@163.com.

References

- 1.Cascales L, Craik DJ. Naturally occurring circular proteins: distribution, biosynthesis and evolution. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:5035–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Condie JA, Nowak G, Reed DW, et al. The biosynthesis of Caryophyllaceae-like Cyclic peptides in Saponaria vaccaria L. from DNA-encoded precursors. Plant J. 2011;67:682–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramalho SD, Wang CK, King GJ, et al. Synthesis, racemic X-ray crystallographic, and permeability studies of bioactive orbitides from Jatropha species. J Nat Prod. 2018;81:2436–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber CJ, Pujara PT, Reed DW, Chiwocha S, Zhang H, Covello PS. The two-step biosynthesis of Cyclic peptides from linear precursors in a member of the plant family Caryophyllaceae involves cyclization by a Serine protease-like enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12500–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giordanetto F, Kihlberg J. Macrocyclic drugs and clinical candidates: what can medicinal chemists learn from their properties? J Med Chem. 2014;57:278–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita H, Takeya K. Bioactive Cyclic peptides from higher plants. Heterocycles. 2010;80:739–64. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tam JP, Lu YA, Yang JL, Chiu KW. An unusual structural motif of antimicrobial peptides containing end-to-end macrocycle and cystine-knot disulfides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8913–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craik DJ, Lee MH, Rehm FBH, Tombling B, Doffek B, Peacock H. Ribosomally-synthesised Cyclic peptides from plants as drug leads and pharmaceutical scaffolds. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26:2727–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan NH, Zhou JJ. Plant cyclopeptides. Chem Rev. 2006;106:840–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao M, Wang L, Feng ZM, et al. Advances on cyclopeptides of plants. China J Chin Mater Med. 2024;49:1172–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu F, Yang H, Lin SD, et al. Cyclic peptide extracts derived from Pseudostellaria heterophylla ameliorates COPD via regulation of the TLR4/MyD88 pathway proteins. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheng R, Xu X, Tang Q, et al. Polysaccharide of radix pseudostellariae improves chronic fatigue syndrome induced by Poly I:C in mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009;2011:840516. 10.1093/ecam/nep208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Tan NH, Zhou J, Chen CX, Zhao SX. Cyclopeptides from the roots of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:1327–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita H, Kobata H, Takeya K, Itokawa H. Pseudostellarin G, a new tyrosinase inhibitory Cyclic octapeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:3563–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita H, Kayashita T, Takeya K, Itokawa HJJONP. Cyclic peptides from higher plants, part 15, Pseudostellarin H, a new Cyclic octapeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;58:943–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao XF, Zhang Q, Zhao HT, et al. A new Cyclic peptide from the fibrous root of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Nat Prod Res. 2020;36:3368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morita H, Kayashita T, Kobata H, Gonda A, Takeya K, Tetrahedron HIJ. Pseudostellarins D - F, new tyrosinase inhibitory Cyclic peptides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;21:9975–82. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houshdar Tehrani MH, Gholibeikian M, Bamoniri A, Mirjalili BBF. Cancer treatment by caryophyllaceae-type cyclopeptides. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:600856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Q, Cai X, Huang M, Wang S. A specific peptide with Immunomodulatory activity from Pseudostellaria heterophylla and the action mechanism. J Funct Foods. 2020;68:103887. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finking R, Marahiel MA. Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides1. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:453–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt EW, Nelson JT, Rasko DA, et al. Patellamide A and C biosynthesis by a microcin-like pathway in Prochloron didemni, the cyanobacterial symbiont of Lissoclinum patella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson MA, Gilding EK, Shafee T, et al. Molecular basis for the production of Cyclic peptides by plant Asparaginyl endopeptidases. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mylne JS, Chan LY, Chanson AH, et al. Cyclic peptides arising by evolutionary parallelism via asparaginyl-endopeptidase-mediated biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2765–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnison PG, Bibb MJ, Bierbaum G, et al. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:108–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belknap WR, Mccue KF, Harden LA, Vensel WH, Bausher MG, Stover E. A family of small Cyclic amphipathic peptides (SCAmpPs) genes in citrus. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song ZL, Connor B, David JS, et al. The flax genome reveals orbitide diversity. BMC Genomics. 2022;23:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng W, Zhou T, Li J, et al. The biosynthesis of heterophyllin B in Pseudostellaria heterophylla from prePhHB-encoded precursor. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu M, Yang Y, Zhou T, et al. Cloning and functional verification of PhAEP gene, a key enzyme for biosynthesis of heterophyllin A in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. China J Chin Mater Med. 2023;48:1851–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, Zhang J, Sun L, et al. High efficient multisites genome editing in allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;16:137–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Q, Wang C, e Jiao X. Hi-TOM: a platform for high-throughput tracking of mutations induced by crispr/cas systems. Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62:1–7. t al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Ou XH, Hu YP, Xu J, He H, Zhou T. Effects of nitrate nitrogen on the growth and heterophyllin B of Pseudostellaria heterophylla.Northern hortic. 2024;7:104–11.

- 32.Fisher MF, Zhang J, Berkowitz O, Whelan J, Mylne JS. Cyclic peptides in seed of Annona muricata are ribosomally synthesized. J Nat Prod. 2020;83:1167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gui B, Shim YY, Datla RS, Covello PS, Stone SL, Reaney MJ. Identification and quantification of cyclolinopeptides in five flaxseed cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:8571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnett PG, Young LW, Olivia CM, Jadhav PD, Okinyo-Owiti DP, Reaney MJT. Novel flax orbitide derived from genetic deletion. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang S, Tian L, Liu H, et al. Large-scale discovery of non-conventional peptides in maize and Arabidopsis through an integrated peptidogenomic pipeline. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1078–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian L, Chen X, Jia X, et al. First report of antifungal activity conferred by non-conventional peptides. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19:2147–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh P, Roychoudhury A. Plant peptides involved in abiotic and biotic stress responses and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;43:1410–27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Yamashita T, Kakita M, Nakayama T, Ohkubo Y, Hayashi Y, et al. Peptide ligand-mediated trade-off between plant growth and stress response. Science. 2022;378:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang ZM, Bai GX, Huang WT, et al. The rice peptide transporter OsNPF7.3 is induced by organic nitrogen, and contributes to nitrogen allocation and grain yield. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu DY, Hu R, Li J, et al.,. Peptide transporter OsNPF8.1 contributes to sustainable growth under salt and drought stresses, and grain yield under nitrogen deficiency in rice. Rice Sci. 2023;30:113–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minsoo K, Chen YH, Xi JJ, et al. An antimicrobial peptide essential for bacterial survival in the nitrogen-fixing symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:15238–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui Y, Li M, Yin X, et al. OsDSSR1, a novel small peptide, enhances drought tolerance in Transgenic rice. Plant Sci. 2018;270:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XM, Han HP, Chen M, et al. Overexpression of OsDT11, which encodes a novel Cysteinerich peptide, enhances drought tolerance and increases ABA concentration in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;93:21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saska I, Gillon AD, Hatsugai N, et al. An Asparaginyl endopeptidase mediates in vivo protein backbone cyclization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen GK, Wang S, Qiu Y, Hemu X, Lian Y, Tam JP. Butelase 1 is an Asx-specific ligase enabling peptide macrocyclization and synthesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:732–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kersten RD, Weng JK. Gene-guided discovery and engineering of branched Cyclic peptides in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E10961–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J, Zhen W, Long D, Ding L, Gong A, Xiao C, et al. De Novo sequencing and assembly analysis of the Pseudostellaria heterophylla transcriptome. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0164235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X, Chen B, Shang X, Fang S. RNA in situ hybridization and expression of related genes regulating the accumulation of triterpenoids in Cyclocarya paliurus. Tree Physiol. 2021;41:2189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files