Abstract

Background:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Several prognostic scores exist in DLBCL, including the International Prognostic Index (IPI). More recently, a modification of the IPI that estimates the risk of progression to the central nervous system (CNS-IPI) was published. Whether the CNS-IPI index is sufficient to prognosticate DLBCL survival is yet untested.

Objectives:

We aim to describe the outcomes of DLBCL patients based on CNS-IPI risk groups.

Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed all DLBCL cases diagnosed from January 2015 until April 2022 at an academic tertiary hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. CNS-IPI was calculated at the time of diagnosis. The outcomes were compared between two CNS-IPI risk categories: low and intermediate/high-risk groups. Logrank method was used to calculate P value, and Kaplan–Meier method to estimate survival.

Results:

A total of 136 patients were included (median age: 56.5 years), of which 38 (28%) died: 5 in the low-risk group and 33 in the intermediate/high-risk group. Low-risk and intermediate/high-risk CNS-IPI were found in 41 (30%) and 95 (70%) patients, respectively. The median survival in the low-risk and intermediate/high-risk CNS-IPI groups was 66 months [95% CI: 60–not-reached (NR)] and NR (95% CI: 24–NR) (P = 0.007), respectively. Only seven (5%) patients developed progression to the CNS, of which 6 (86%) were in the intermediate/high-risk group.

Conclusion:

The risk of progression to the central nervous system was moderate in our diffuse large B-cell lymphoma population. Patients with intermediate/high-risk CNS-IPI had worse survival compared with low-risk patients. The CNS-IPI was found to a good model to not only estimate the risk of disease progression to the central nervous system but also overall survival.

Keywords: CNS-IPI, diffuse large B-cell, DLBCL, International Prognostic Index, lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Of all lymphoma types, DLBCL represents around 30% of all adult cases.[1] Prognosis has improved over time and roughly 65%–70% of DLBCL patients are cured.[2] Despite these improvements, relapse is common, with disease progression resulting in death among many patients.

Several prognostic scores can help estimate the long-term survival of patients with DLBCL. The International Prognostic Index (IPI) was one of the initial predictive models used in DLBCL,[3] which was followed by many other modifications and validations.[4,5,6] Furthermore, extranodal involvement in DLBCL is common and several involved sites have been associated with an increased risk of secondary progression to the central nervous system (CNS).[7] In particular, involvement of the adrenal glands, kidneys, testes, ovaries, epidural space, and possibly bone marrow and other organs have been shown to increase the risk of CNS.[8]

Given that CNS involvement in DLBCL is serious with high mortality, a modified IPI score that focuses on estimating the risk of CNS relapse in DLBCL was developed and validated (CNS-IPI).[8] Since IPI and CNS-IPI share most of the variables, it is only plausible that both models can estimate long-term survival, although the ability of CNS-IPI to estimate survival has not yet been statistically proven. In this study, we aim to describe the clinical features of patients with high CNS-IPI score and their survival prediction using CNS-IPI.

METHODS

This is a retrospective study that included all new cases of DLBCL diagnosed and treated at the adult hematology section of King Saud University Medical City (KSUMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from January 2015 to April 2022. The KSUMC lymphoma database was searched to identify patients with DLBCL and the data were collected accordingly.

The study was conducted after the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Saud University. Patient data confidentiality was ensured during the study period. The manuscript was prepared following the STROBE reporting guidelines.

The primary objective of the study was to correlate between two risk categories of the CNS-IPI: the low versus intermediate/high CNS-IPI groups and overall survival (OS). A pre hoc decision was made to combine intermediate- and high-risk groups to better reflect clinical practice, as patients in the low-risk category are usually not offered CNS-directed therapy, unlike the other two risk groups. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis until death or last follow-up. Secondary objectives included description of clinical features of CNS-IPI risk groups, estimation of the risk of CNS progression, and description of the clinical features of patients who developed CNS progression.

Data collected were as follows: age, gender, date of diagnosis, number of extranodal sites, area of extranodal sites, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, CNS prophylaxis administration and CNS involvement, date of last follow-up, and the survival status (alive or dead).

Statistical analysis

The survival outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and P values/Wald 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined using the log-rank test. All analyses were performed using two-tailed tests, with the type 1 error rate fixed at 0.05. Simple frequency statistics were used to summarize the remaining variables. Data were analyzed using R Studio version 1.3.1056 and R for Statistical Computing version 4.0.2.

RESULTS

A total of 136 patients with DLBCL were included. Most cases were male (96, 70.5%), with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) of 0–1 (112, 82%), high LDH (75, 55%), and extra-nodal involvement of two or more sites (76, 56%). Table 1 describes the detailed patients’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients included in the study (N=136)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age >60 years | 59 (44.4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 96 (70.5) |

| Female | 40 (29.4) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0–1 | 112 (82.0) |

| >1 | 24 (18.0) |

| High LDH | 75 (55.0) |

| Bulky disease | 15 (11) |

| Stage | |

| I–II | 52 (38.0) |

| III–IV | 84 (62.0) |

| Extranodal sites | |

| <2 | 37 (27) |

| ≥2 | 76 (56) |

| Selected high-risk anatomical sites | |

| Renal or adrenal involvement | 17 (12.5) |

| Bone marrow | 20 (14.7) |

| Breast | 1 (0.7) |

| Testis/ovary | 2 (1.5) |

| Epidural/paraspinal | 3 (2) |

| CNS-IPI | |

| 0–1 (low) | 41 (30.1) |

| 2–3 (intermediate) | 64 (47) |

| 4–6 (high) | 31 (22.8) |

| Intrathecal chemotherapy | 29 (21) |

| CNS relapse | 7 (5.1) |

| COO using Hans algorithm | |

| GCB | 51 (38) |

| Non-GCB | 71 (52) |

| COO not reported | 14 (10) |

| IPI risk groups | |

| Low (0–1) | 52 (38) |

| Low–intermediate (2) | 26 (19) |

| High–intermediate (3) | 32 (24) |

| High (4–5) | 26 (19) |

| Primary therapy | |

| RCHOP 6 cycles | 74 (54) |

| RCHOP 4–5 cycles | 15 (11) |

| RCHOP 1–3 cycles | 13 (10) |

| RCVP/CVP | 7 (5) |

| DA-EPOCHR 6 cycles | 3 (2) |

| DA-EPOCHR 1 cycle | 1 (<1) |

| CNS prophylaxis | |

| IT-MTX | 24 (18) |

| Triple IT | 3 (2) |

| HD-MTX | 2 (1) |

| IT-ARA-C | 2 (1) |

ECOG PS – Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; LDH – Lactate dehydrogenase; GCB – Germinal-center b-cell; RCHOP – Rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone; DA-EPOCHR – Dose-adjusted etoposide/rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone; RCVP – Rituximab/cyclophosphamide/vincristine/prednisone; CNS-IPI – Central nervous system-international prognostic index; IT – Intrathecal, MTX – Methotrexate; HD – High-dose; ARA-C – Cytarabine

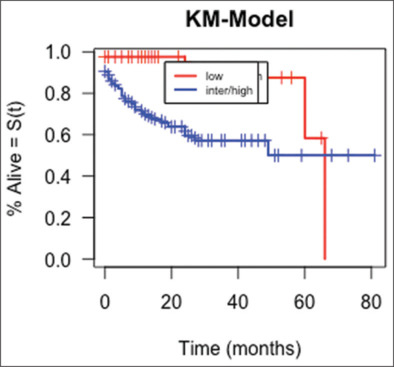

A total of 38 (28%) patients died, with the cause of death being lymphoma (63.2%), treatment-related toxicity (26.3%), and unrelated causes (10.5%). The median follow-up time for alive patients was 16 months (range: 0–81 months). The median survival for the whole group was 66 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 49-not reached (NR)]. Figure 1 presents the OS of the whole group. There were only five (12%) deaths in the low-risk group, while 33 (35%) deaths occurred in the intermediate/high-risk group. There was a significant difference in the median survival in the low-risk group (66 months, 95% CI: 60-NR) and the intermediate/high-risk group (NR, 95% CI: 24-NR) (P = 0.007) [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival for all patients. Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval, while the midline horizontal line represents the average

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival comparison between low versus intermediate/high-risk CNS-IPI groups (P = 0.007)

Table 2 shows patients’ characteristics according to the risk groups. CNS involvement at the time of diagnosis was reported in seven patients, all of whom also had systemic disease involvement. Two of these patients died before starting therapy, while five were started on immunochemotherapy along with high-dose methotrexate (n = 2) or intrathecal chemotherapy (2) (one patient was lost to follow-up). CNS relapse was reported only in seven patients (5%) while intrathecal prophylaxis was administered in 29 (21%) patients [Table 3]. The median time of DLBCL diagnosis until development of CNS relapse was 18 months (range: 6–42 months). The primary therapy was rituximab chemotherapy in 113 patients, while 8 declined therapy, 8 were lost to follow-up after they presented to different hospitals, and 7 were transferred to palliative care before initiating chemotherapy. CNS prophylaxis was administered to 29 (21%) patients, of whom 21 (72%) were in the intermediate/high risk group. Details regarding rituximab chemotherapy and CNS prophylaxis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients according to the risk groups (i.e., low versus intermediate/high Central Nervous System–International Prognostic Index score)

| Variable | Low, n (%) | Intermediate/high, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 41 (30.1) | 95 (69.8) |

| Age >60 (years) | 5 (12.1) | 54 (56.8) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 27 (66) | 69 (72.6) |

| Female | 14 (34) | 26 (27.3) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0–1 | 42 (100) | 71 (75) |

| >1 | 0 | 24 (25.2) |

| High LDH | 6 (15) | 69 (73) |

| Bulky disease | 5 (12) | 10 (11) |

| Stage | ||

| I–II | 32 (78) | 20 (21.0) |

| III–IV | 9 (22) | 75 (79) |

| Extranodal sites | ||

| <2 | 16 (40) | 21 (22.0) |

| ≥2 | 14 (34) | 62 (65.2) |

| CNS relapse | 1 (2.4) | 6 (6) |

| 2-year survival rate | 95 | 67 |

| 5-year survival rate | 90 | 65 |

ECOG PS – Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; LDH – Lactate dehydrogenase; CNS – Central nervous system

Table 3.

Characteristics of the patients with progression to the central nervous system (n=7)

| CNS relapse | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 56 (19–70) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4 (57) |

| Female | 3 (43) |

| CNS-IPI | |

| Low | 1 (14) |

| Intermediate | 5 (71) |

| High | 1 (14) |

| Two or more extranodal sites | 5 (71) |

| Renal or suprarenal gland | 1 (14) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 2 (29) |

| Intrathecal chemotherapy prophylaxis | |

| Yes | 3 (43) |

| No | 4 (57) |

| Sites | |

| Parenchymal | 7 (100) |

| Leptomeningeal | 1 (14) |

| Both parenchymal and leptomeningeal | 1 (14) |

| Crania nerve palsy | 2 (29) |

CNS-IPI – Central Nervous System–International Prognostic Index

DISCUSSION

The CNS-IPI risk model was developed from data involving 2164 adult DLBCL patients based on a risk model that consisted of the IPI factors in addition to involvement of kidneys and/or adrenal glands and was later validated in an independent cohort from the Canadian British Columbia Cancer Agency.[8] This score divides patients into three risk categories, namely, low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. The high-risk group showed a 2-year rate of progression in the CNS of 10.2%. Based on this risk model, it was suggested that patients with >10% risk of CNS progression should be considered for CNS-directed prophylactic therapies. Unfortunately, CNS-directed prophylaxis has not consistently been shown to decrease the risk of secondary CNS progression: some studies have shown benefit of prophylaxis, while others revealed no added benefit.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]

Over the follow-up period of our study, we found that the risk of CNS involvement in our DLBCL cohort was 5%. This could be related to the fact that most of our patients (47%) were in the intermediate risk group of the CNS-IPI, which is more or less similar to the reported risk of this group in the literature.[8] Additionally, as only seven patients developed secondary CNS progression, this number was too small to conduct any meaningful statistical analysis or to estimate the benefit of CNS prophylaxis, which was given in 29 patients. Of these seven patients, five (71%) had an intermediate CNS-IPI score and one had renal/adrenal involvement. Five of these patients had two or more extranodal site involvement and only three (43%) received CNS prophylaxis.

At the time of DLBCL diagnosis, physicians usually attempt to calculate the different prognostic scores, in particular, IPI and its modified versions. However, it is simpler to use one predictive and robust score that can help estimate not only CNS risk but also overall survival. Our study showed that CNS-IPI has the ability to do both. There was a statistically significant difference in survival between patients who had low-risk CNS-IPI and those with intermediate/high-risk scores.

We have shown that testes or ovarian involvement were rare in newly diagnosed DLBCL patients (1.5%), while bone marrow involvement was more common and reported in 14.7% of cases. It is also noteworthy that the involvement of two or more extranodal sites was more common in the intermediate/high-risk group (about 65%), which was roughly two times higher than that in the low-risk group (34%). Previous data have correlated the number of extranodal sites involved with the future risk of CNS progression.[17]

Strengths and limitations

Our study has many strengths. We have shown in a good sample size that CNS-IPI is a useful tool in predicting survival. In addition, we have reported a detailed description of patients with high CNS-IPI and such data are lacking in our population.

Despite these strengths, our data also have some limitations, including the potential bias that could arise from chart review of retrospective data. Additionally, we did not plan to test the differences in OS between the three CNS-IPI categories, and thus it remains unknown if an OS difference exist after separating intermediate risk from high risk. Moreover, data on comorbidities, double-hit status and progression-free survival were not evaluated in the current study and these could add value for later studies. Finally, these findings should be confirmed in future prospective studies with a larger sample size.

CONCLUSION

The risk of progression to the central nervous system was moderate in our diffuse large B-cell lymphoma population. The study also found that the CNS-IPI is a robust model that can estimate not only the risk of progression to the central nervous system but also overall survival.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Saud University (Research Project No. E-23-7542; date: January 31, 2023), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The requirement for patient consent was waived owing to the study design. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.

Peer review

This article was peer-reviewed by two independent and anonymous reviewers.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.F.A and T.B; Methodology: all authors; Data analysis: M.F.A and T.B; Writing–original draft preparation: M.F.A and T.B; Writing – review and editing: all authors; Supervision: M.F.A.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the College of Medicine Research Center at the College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, for their logistical and personnel support.

Funding Statement

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IB, Berti E, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: Lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1720–48. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epperla N, Vaughn JL, Othus M, Hallack A, Costa LJ. Recent survival trends in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma – Have we made any progress beyond rituximab? Cancer Med. 2020;9:5519–25. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Hoskins P, et al. The revised international prognostic index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109:1857–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Galaly TC, Villa D, Alzahrani M, Hansen JW, Sehn LH, Wilson D, et al. Outcome prediction by extranodal involvement, IPI, R–IPI, and NCCN-IPI in the PET/CT and rituximab era: A Danish-Canadian study of 443 patients with diffuse-large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:1041–6. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, Glass B, Schmitz N, Pfreundschuh M, et al. Standard international prognostic index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2373–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ollila TA, Olszewski AJ. Extranodal diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Molecular features, prognosis, and risk of central nervous system recurrence. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:38. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0555-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M, Kansara R, Villa D, Sehn LH, et al. CNS international prognostic index: A risk model for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3150–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.6520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eyre TA, Djebbari F, Kirkwood AA, Collins GP. Efficacy of central nervous system prophylaxis with stand-alone intrathecal chemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy in the rituximab era: A systematic review. Haematologica. 2020;105:1914–24. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.229948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson MR, Eyre TA, Kirkwood AA, Wong Doo N, Soussain C, Choquet S, et al. Timing of high-dose methotrexate CNS prophylaxis in DLBCL: A multicenter international analysis of 1384 patients. Blood. 2022;139:2499–511. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orellana-Noia VM, Reed DR, McCook AA, Sen JM, Barlow CM, Malecek MK, et al. Single-route CNS prophylaxis for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas: Real-world outcomes from 21 US academic institutions. Blood. 2022;139:413–23. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puckrin R, El Darsa H, Ghosh S, Peters A, Owen C, Stewart D. Ineffectiveness of high-dose methotrexate for prevention of CNS relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:764–71. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobillo S, Joffe E, Sermer D, Mondello P, Ghione P, Caron PC, et al. Prophylaxis with intrathecal or high-dose methotrexate in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and high risk of CNS relapse. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:113. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00506-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong SY, de Mel S, Grigoropoulos NF, Chen Y, Tan YC, Tan MS, et al. High-dose methotrexate is effective for prevention of isolated CNS relapse in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:143. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K, Yoon DH, Hong JY, Kim S, Lee K, Kang EH, et al. Systemic HD-MTX for CNS prophylaxis in high-risk DLBCL patients: A prospectively collected, single-center cohort analysis. Int J Hematol. 2019;110:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s12185-019-02653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldschmidt N, Horowitz NA, Heffes V, Darawshy F, Mashiach T, Shaulov A, et al. Addition of high-dose methotrexate to standard treatment for patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma contributes to improved freedom from progression and survival but does not prevent central nervous system relapse. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60:1890–8. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1564823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Galaly TC, Villa D, Michaelsen TY, Hutchings M, Mikhaeel NG, Savage KJ, et al. The number of extranodal sites assessed by PET/CT scan is a powerful predictor of CNS relapse for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: An international multicenter study of 1532 patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.