Abstract

Background:

The rising prevalence of obesity is associated with significant health risks, underscoring the need for effective prevention and treatment. The use of anti-obesity medications (AOMs) remains limited due to several barriers.

Objectives:

To physicians’ perspectives and clinical practices regarding AOMs in Saudi Arabia.

Methods:

We conducted a national cross-sectional survey between May and August 2024 targeting family physicians, endocrinologists, and bariatric surgeons in Saudi Arabia. We distributed the survey using convenience sampling through department heads at hospitals across five regions and relevant professional societies. We collected data on clinician demographics, clinical practices, and perceptions related to AOMs. We compared responses across specialties and identified predictors of prescribing AOMs.

Results:

A total of 92 clinicians completed the survey: 71 family physicians, 20 endocrinologists, and 1 bariatric surgeon. Overall, 15.3% of the respondents had received formal obesity-focused training. While 92.4% reported counseling patients on obesity-related complications, 57.6% routinely referred patients to dietitians. Endocrinologists preferred international guidelines and prescribed AOMs more frequently than family physicians (90.0% vs. 60.5%; P < 0.001). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists were the most commonly prescribed first-line agents. Key predictors of prescribing AOMs included medical specialty, guidelines preference, and prior obesity training.

Conclusions:

Physician specialty, clinical experience, and adherence to guidelines influence the prescription of anti-obesity medications in Saudi Arabia. Limited training and a more conservative approach among family physicians highlight the need for targeted educational interventions to improve obesity management. Initiatives should focus on harmonizing clinical guidelines and expanding access to evidence-based treatments.

Keywords: Anti-obesity medications, GLP-1 receptor agonists, obesity, Saudi Arabia, survey

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is among the leading causes of death worldwide. Over the past three decades, the prevalence of obesity has steadily increased worldwide, including in Saudi Arabia.[1] A recent systematic review reported a marked rise in overweight and obesity among adults in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Cooperation Council countries over the past 40 years, with sociodemographic factors, sedentary lifestyles, and unhealthy diets identified as risk factors.[2] These findings have been supported by multiple reports from the Ministry of Health and other organizations.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9] The rising rate of obesity in Saudi Arabia is projected to result in 2.26 million new cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver disease, and liver cancer by 2040.[10] This underscores the importance of focused strategies aimed at prevention and treatment.[2,11]

Managing obesity presents a complex challenge. The initial step typically involves prompting lifestyle modifications. However, the efficacy of such interventions is modest, achieving weight reductions of only 3%–10%, and is often followed by a high rate of weight regain.[12] Given these limitations, attention has shifted toward complementary therapeutic modalities, such as bariatric surgery and pharmacotherapy, which can potentially result in more durable weight loss.[13] Pharmacotherapy can assist individuals with obesity achieve and maintain clinically meaningful weight loss, thereby reducing the risk of obesity-related complications.[14] Four agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for adult weight management, including naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) tirzepatide and liraglutide.[11]

Despite the availability of approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), the prevalence of obesity in the United States has continued to rise in recent decades.[15] Factors contributing to the low levels of initiation and sustained use of AOMs may stem from the hesitance of public health and medical organizations to acknowledge obesity as a disease, limited insurance coverage, inadequate provider training, and misconceptions about the safety and efficacy of available treatments.[14]

This study aimed to understand the perspectives, attitudes, and practices of physicians who prescribe AOMs in Saudi Arabia and to examine the differences in prescribing patterns between family physicians and endocrinologists. The main objective was to assess physicians’ opinions and perspectives regarding the effectiveness of AOMs.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of physicians treating patients with obesity in Saudi Arabia. The survey spanned five major regions—Central, Eastern, Western, Southern, and Northern—between May and August 2024.

Participants

We targeted certified family physicians, endocrinologists, and bariatric surgeons who actively treat adults and are practicing in Saudi Arabia. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) certified medical practitioners in family medicine, endocrinology, or bariatric surgery; 2) actively practicing in Saudi Arabia; and 3) agreed to participate in the survey. Incomplete responses were excluded.

Sampling strategy

We used a convenience sampling strategy, targeting family medicine physicians, endocrinologists, and bariatric surgeons. The survey was disseminated through the heads of relevant departments in various healthcare settings, who further distributed it to their staff. Moreover, the survey was distributed through the Saudi Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism and the Saudi Society of Family and Community Medicine.

Survey development

We developed survey items through an extensive literature review and focus group sessions with obesity management experts. The items were categorized into domains. We removed redundant items to keep the survey concise yet comprehensive. The final survey included multiple-choice questions and Likert-scale items.

To assess the clarity and relevance of the survey questions, we administered a clinical sensibility questionnaire [Supplementary File 1], adapted from Burns et al. to 10 clinicians representing the specialties of family medicine, endocrinology, and bariatric surgery.[16] Their feedback informed revisions to enhance the survey’s clarity and relevance. Prior to distribution, three obesity experts further reviewed the questionnaire for final modifications.

The final survey instrument contained 12 items across various domains: demographic information (gender, age, specialty, years in practice, and region of practice); clinical practice patterns (training in obesity management, proportion of patients treated for obesity, sector of practice, and guidelines followed); and perceptions and opinions (effectiveness of AOMs, beliefs about obesity as a chronic disease, significant factors in the development of obesity, and frequency of counselling patients on weight loss). The final version of the survey is included in Supplementary File 2.

Survey Administration

We administered the survey electronically via SurveyMonkey.[17] An email/message with a cover letter explaining the study’s objectives and a survey link was sent to potential respondents. Follow-up reminder emails were sent at one and two weeks to maximize responses. The survey link was distributed through the aforementioned societies and department heads across various healthcare settings. The exact response rate could not be calculated, as we could not track the emails and messages sent through electronic applications (WhatsApp Inc., Facebook, Inc.).

Ethical considerations

We obtained approval from the central ethics committee. Participation was voluntary, as stated in the survey cover letter, and completing the survey was considered consent to participate. The survey was anonymous, ensuring the confidentiality of the respondents. The data were securely stored and accessed only by the research team. We followed the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS) guidelines for reporting the results of this questionnaire [Supplementary File 3].[18]

Data analysis

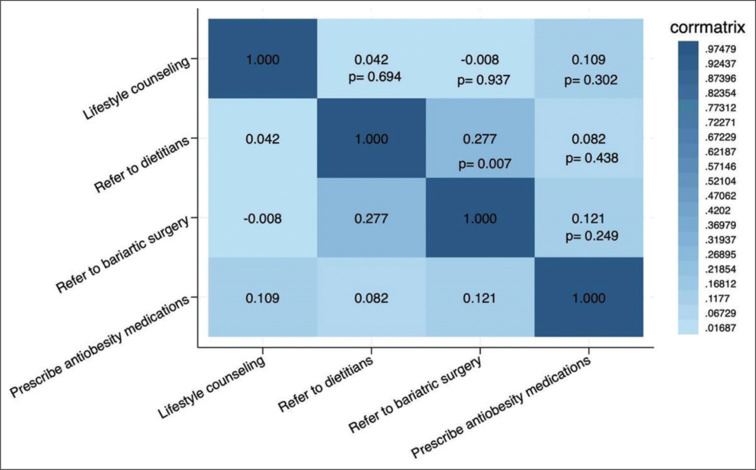

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, medians, 25th–75th percentiles, frequencies, and percentages) were used to summarize the demographic information and survey responses. The internal consistency of the survey items was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. We also explored the relationships between different obesity management practices via Spearman correlations and presented them graphically as a heatmap.

To further examine the factors associated with the use of AOMs and referrals to bariatric surgery, we conducted two univariable ordinal logistic regression analyses. Both models include predictors such as specialty, years of experience, practice setting, and adherence to clinical practice guidelines. The first model examined the frequency of prescribing AOMs, while the second focused on the frequency of referrals to bariatric surgery. The outcome variables were collapsed into three levels: “strongly agree” and “agree” were merged, and “strongly disagree” and “disagree” were merged. We reported the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for all regression analyses.

Responses were compared between family medicine physicians and endocrinologists using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann‒Whitney test for continuous variables. Results are presented as numbers and percentages, means (SDs) or medians (Q1–Q3). Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 29; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA version 18 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. There were no variables with missing data.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

The survey demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75. A total of 92 clinicians completed the electronic survey, the majority of whom were males (64.1%), with an average age of 37.4 ± 10.2 years. Most participants specialized in family medicine (77.2%), followed by endocrinology (21.7%) and bariatric surgery (1.1%). Nearly half (44.6%) had been in clinical practice for <5 years, and the majority were from the Central region (59.8%) and worked in the governmental sector (67.4%). Overall, 15.3% of the respondents had completed obesity-focused training or certification: 30.0% of the endocrinologists and about 10% of the family physicians. Half the respondents (50.0%) reported treating >25% of their patients for obesity [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical practice characteristics of the respondents

| Variable | All respondents (N=92), n (%) |

Family physicians (n=71), n (%) |

Endocrinologists (n=20), n (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 59 (64.1) | 41 (57.7) | 17 (85.0) | 0.025a |

| Age (years) (means±SD) | 37.4±10.2 | 35.4±9.4 | 44.7±10.3 | <0.001b |

| Years in clinical practice | ||||

| <5 | 41 (44.6) | 37 (52.1) | 3 (15.0) | 0.009c |

| 6–10 | 22 (23.9) | 15 (21.1) | 7 (35.0) | |

| >10 | 29 (31.5) | 19 (26.8) | 10 (50.0) | |

| Region | ||||

| Central | 55 (59.8) | 43 (60.6) | 12 (60.0) | 0.286c |

| Eastern | 18 (19.6) | 15 (21.1) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Western | 12 (13.0) | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Southern | 5 (5.4) | 5 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Northern | 2 (2.2) | 6 (8.5) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Obesity training or certification | 14 (15.3) | 7 (9.9) | 6 (30.0) | 0.015c |

| Proportion of patients with obesity in daily practice | ||||

| ≤25% | 46 (50.0) | 35 (49.3) | 11 (55.0) | 0.545c |

| >25% | 46 (50.0) | 36 (50.7) | 9 (45.0) | |

| Practice sector | ||||

| Governmental sector | 62 (67.4) | 1 (1.4) | 8 (40.0) | <0.001c |

| Private sector | 10 (10.9) | 56 (78.9) | 6 (30.0) | |

| Both | 20 (21.7) | 14 (19.7) | 6 (30.0) |

aChi-squared test; bt-test; cFisher’s-Freeman-Halton exact test with more than 2×2 tables. SD – Standard deviation

Clinical practice patterns

Approximately 24% of the respondents aimed for a 5% weight reduction in their patients. In contrast, 39.1% of physicians reported using patient comorbidities as the basis for determining weight loss targets. While 92.4% frequently counselled patients on obesity-related complications, 57.6% routinely referred patients to dietitians. Overall, 93.5% of the respondents, always or often, counselled patients about lifestyle modification. The respondents reported time constraints (37.0%), serious health issues (25.0%), and the absence of weight-related health issues (15.2%) as the most common barriers to discussing obesity in daily practice [Table 2].

Table 2.

Summary of survey responses

| Variable | All responses (N=92), n (%) | Family physicians (n=71), n (%) | Endocrinologists (n=20), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred obesity guidelines* | ||||

| Saudi clinical practice guidelines | 37 (40.2) | 33 (46.5) | 3 (15.0) | 0.011a |

| ACC/AHA/TOS guideline | 36 (39.1) | 31 (43.7) | 5 (25.0) | 0.132a |

| AACE/ACE obesity guidelines | 34 (37.0) | 19 (26.8) | 15 (75.0) | <0.001a |

| Clinical judgment | 34 (37.0) | 25 (35.2) | 9 (45.0) | 0.424a |

| Obesity is a chronic disease | ||||

| Strongly agree or agree | 88 (95.7) | 67 (93.4) | 20 (100.0) | 0.029b |

| Neutral | 3 (3.3) | 3 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ranking of risk factors for obesity** | ||||

| Diet | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.158c |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.061c |

| Social and behavioral factors | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.304c |

| Genetic factors | 4 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) | 2 (1–4) | 0.039c |

| Iatrogenic causes | 5 (5–6) | 6 (5–6) | 5 (4–5) | 0.054c |

| Neuroendocrine disorders | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 6 (5–6) | 0.014c |

| Counseling patients with obesity-related complications | ||||

| Always or often | 85 (92.4) | 66 (93.0) | 18 (90.0) | 0.433b |

| Sometimes | 7 (7.6) | 5 (7.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Rarely or never | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Reasons for not discussing obesity management with patients | ||||

| Always counseling patients | 48 (52.2) | 35 (49.3) | 12 (60.0) | 0.397a |

| Time constraints | 34 (37.0) | 28 (39.4) | 6 (30.0) | 0.441a |

| More serious health issues | 23 (25.0) | 18 (25.4) | 5 (25.0) | 0.974a |

| Absence of weight-related health issues | 14 (15.2) | 11 (15.5) | 3 (15.0) | >0.99d |

| Patient preference | 12 (13.0) | 11 (15.5) | 1 (5.0) | 0.289d |

| Insurance coverage | 7 (7.6) | 3 (4.2) | 4 (20.0) | 0.039d |

| Target weight loss (% of initial weight) | ||||

| 5% of initial weight | 22 (23.9) | 18 (25.4) | 4 (20.0) | 0.733b |

| 10% of initial weight | 24 (26.1) | 18 (25.4) | 6 (30.0) | |

| ≥15% of initial weight | 10 (10.9) | 6 (8.5) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Depends on comorbidities | 36 (39.1) | 29 (40.8) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Counseling obese patients on lifestyle modification | ||||

| Always or often | 86 (93.5) | 66 (92.9) | 19 (95.0) | >0.99b |

| Sometimes | 5 (5.4) | 4 (7.0) | 1 (5.0) | |

| Rarely or never | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lifestyle modification recommendation* | ||||

| Diet | 91 (98.9) | 71 (100.0) | 19 (95.0) | 0.220d |

| Physical activity | 86 (93.5) | 68 (95.8) | 18 (90.0) | 0.302d |

| Sleep hygiene | 37 (40.2) | 26 (36.6) | 11 (55.0) | 0.139a |

| CBT | 26 (28.3) | 18 (25.4) | 8 (40.0) | 0.200a |

| Frequency of dietitian referral | ||||

| Always or often | 53 (57.6) | 37 (52.1) | 15 (75.0) | 0.104b |

| Sometimes | 29 (31.5) | 25 (35.2) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Rarely or never | 10 (10.9) | 9 (12.7) | 1 (5.0) |

*Statistically significant at P<0.05; **Continuous data are presented as the means±SDs or medians (Q1–Q3), and categorical data are presented as absolute numbers and percentages; aChi-square test; bFisher-Freeman-Halton exact test with more than 2×2 tables; cMann-Whitney U-test; dFisher’s exact test 2×2 tab. AHA – American Heart Association; AACE – American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ACE – American College of Endocrinology; ACC – American College of Cardiology; CBT – Cognitive behavioral therapy; TOS – The Obesity Society

Endocrinologists relied more on the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology (ACE) guidelines,[19] while family physicians preferred the Saudi guidelines (P = 0.011) [Table 2].[20] Compared with family physicians, endocrinologists were more likely to consider insurance coverage and medication costs (P = 0.020).

Most respondents (67.4%) reported prescribing AOMs either always, often, or sometimes in their practice. Compared with 60.6% of the family physicians, 90.0% of the endocrinologists prescribed AOMs (P < 0.001). Overall, 79.3% and 52.2% of the respondents considered a body mass index of >30 kg/m² and 27–29.9 kg/m² with weight-related comorbidities, respectively, as indications for AOMs [Table 3].

Table 3.

Anti-obesity medication prescribing and bariatric surgery referral practices of the respondents

| Variable | All responses (N=92), n (%) | Family physicians (n=71), n (%) | Endocrinologists (n=20), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of prescribing anti-obesity medication for obese patients | ||||

| Always or often | 23 (25.0) | 10 (14.1) | 13 (65.0) | <0.001c |

| Sometimes | 39 (42.4) | 33 (46.5) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Rarely or never | 30 (32.6) | 28 (39.5) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Indications for anti-obesity medications* | ||||

| BMI >30 kg/m2 | 73 (79.3) | 56 (78.9) | 16 (80.0) | >0.99e |

| BMI of 27–29.9 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities | 48 (52.2) | 31 (43.7) | 16 (80.0) | 0.004a |

| Failure to achieve weight loss goals with lifestyle intervention | 38 (41.3) | 29 (40.8) | 9 (45.0) | 0.739a |

| Weight regain following bariatric surgery | 32 (34.8) | 18 (25.4) | 13 (65.0) | 0.001a |

| Patient’s preferences | 21 (22.8) | 20 (28.2) | 1 (5.0) | 0.035e |

| Frequency of bariatric surgery referral | ||||

| Always or often | 20 (21.7) | 13 (18.3) | 6 (30.0) | 0.237c |

| Sometimes | 53 (57.6) | 42 (59.2) | 11 (55.0) | |

| Rarely or never | 19 (20.7) | 16 (22.5) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Indications for bariatric surgery referral* (kg/m2) | ||||

| BMI ≥40 | 82 (89.1) | 65 (91.5) | 16 (80.0) | 0.218e |

| BMI ≥35 | 16 (16.3) | 12 (16.9) | 3 (15.0) | >0.99e |

| BMI ≥35 and obesity-related comorbidity | 65 (70.7) | 55 (77.5) | 9 (45.0) | 0.005a |

| BMI of 30 and 34.9 and type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome | 19 (20.7) | 15 (21.1) | 4 (20.0) | >0.99e |

| BMI of 30–34.9 who failed to achieve sustainable weight loss or comorbidity improvement | 14 (15.2) | 10 (14.1) | 4 (20.0) | 0.499e |

| BMI ≥27.5 kg/m2 for a specific race | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99e |

| Choice of anti-obesity medications* | ||||

| GLP-1 RA | 90 (97.8) | 69 (97.2) | 20 (100.0) | >0.99e |

| Dual GIP/GLP-1 RA | 41 (44.6) | 25 (35.2) | 16 (80.0) | <0.001a |

| Orlistat | 17 (18.5) | 13 (18.3) | 4 (20.0) | >0.99e |

| Bupropion-naltrexone | 5 (5.4) | 4 (5.6) | 1 (5.0) | >0.99e |

| Phentermine-Topiramate | 3 (3.3) | 3 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99e |

| Factors influencing the choice of anti-obesity medication* | ||||

| BMI | 73 (79.3) | 56 (78.9) | 16 (80.0) | >0.99e |

| Comorbidities | 72 (78.3) | 57 (80.3) | 14 (70.0) | 0.365e |

| Obesity-related complications | 70 (76.1) | 53 (74.6) | 16 (80.0) | 0.772e |

| Medication availability | 67 (72.8) | 53 (74.6) | 13 (65.0) | 0.393a |

| Adverse effects | 52 (56.5) | 42 (59.2) | 9 (45.0) | 0.260a |

| Patient preferences | 51 (55.4) | 38 (53.5) | 12 (60.0) | 0.607a |

| Cost | 41 (44.6) | 26 (36.6) | 15 (75.0) | 0.002a |

| Prescription privileges | 26 (28.3) | 24 (33.8) | 2 (10.0) | 0.037a |

| Insurance | 22 (23.9) | 13 (18.3) | 9 (45.0) | 0.020e |

| First-line agent | ||||

| Semaglutide | 42 (45.7) | 33 (46.5) | 9 (45.0) | 0.081c |

| Tirzepatide | 24 (26.1) | 14 (19.7) | 9 (45.0) | |

| Liraglutide | 23 (25.0) | 21 (29.6) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Orlistat | 3 (3.3) | 3 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Factors influencing choice of GLP-1 RA or dual GIP/GLP-1 agonists* | ||||

| Availability | 77 (83.7) | 57 (80.3) | 19 (95.0) | 0.176e |

| Effectiveness | 44 (47.8) | 32 (45.1) | 12 (60.0) | 0.238a |

| Dosing frequency | 42 (45.7) | 34 (47.9) | 8 (40.0) | 0.532a |

| Patient preference | 39 (42.4) | 30 (42.3) | 9 (45.0) | 0.826a |

| Adverse effects | 30 (32.6) | 24 (33.8) | 6 (30.0) | 0.749a |

| Side effects prompting discontinuation of GLP-1 RA or dual GIP/GLP-1 agonists* | ||||

| Severe nausea and vomiting | 60 (65.2) | 44 (62.0) | 15 (75.0) | 0.281a |

| Acute pancreatitis | 18 (19.6) | 13 (18.3) | 5 (25.0) | 0.532e |

| Diarrhea | 18 (19.6) | 14 (19.7) | 4 (20.0) | >0.99e |

| Hypersensitivity reaction | 11 (12.0) | 10 (14.1) | 1 (5.0) | 0.445e |

| Hypoglycemia | 9 (9.8) | 8 (11.3) | 1 (5.0) | 0.678e |

| Alopecia | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.220e |

| Clinical trial is needed in Saudi Arabia | 87 (94.6)† | 68 (95.8) | 19 (95.0) | >0.99e |

*The denominator is 71 for family physicians and 20 for endocrinologists; respondents were able to choose more than one option; *Statistically significant at P<0.05**Continuous data are presented as the means±SDs or medians (Q1–Q3), and categorical data are presented as absolute numbers and percentages; †This reflects participants who agreed that a clinical trial is needed; aChi-square test; bt-test; cFisher-Freeman-Halton exact test with more than 2×2 tables; dMann-Whitney U-test; eFisher’s exact test 2×2 tab. BMI – Body mass index; GLP-1 RA – Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; GIP – Glucose- insulinotropic polypeptide; SD – Standard deviation

GLP-1 RAs were the most prescribed first-line agents (97.8%), with 45.7% of respondents choosing semaglutide as the first option, followed by tirezepatide (26.1%) and liraglutide (25.0%). Factors that influenced the choice of medication included availability (83.7%), effectiveness (47.8%), and dosing frequency (45.7%). There were no statistically significant differences in AOM selection between family physicians and endocrinologists.

Predictors of AOM prescription and referral for bariatric surgery

Table 4 summarizes the predictors of AOM prescription and bariatric surgery referral. Ordinal logistic regression analysis revealed that specialization in endocrinology (OR: 9.97, 95% CI: 3.36–29.60), use of AACE guidelines (OR: 2.43, 95% CI: 1.09–5.43), use of clinical judgment (OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 1.22-6.16), prior obesity training (OR: 2.45, 95% CI: 1.07–5.64), and age (OR: 1.04, 95%: CI 1.01–1.08) were associated with increased odds of prescribing AOMs. In contrast, specialization in family medicine (OR: 0.11, 95% CI: 0.32–0.40) and use of Saudi obesity guidelines (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.16–0.79) were associated with lower odds of prescribing AOMs. In the regression analysis, none of the variables were significant predictors of referral to bariatric surgery [Table 5].

Table 4.

Predictors of anti-obesity medication prescription

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Specialization in endocrinology | 9.97 (3.36–29.60) | <0.001 |

| Use of AACE/ACE obesity guidelines | 2.43 (1.09–5.43) | 0.031 |

| Use of clinical judgment | 2.74 (1.22–6.16) | 0.014 |

| Obesity training | 2.45 (1.07–5.64) | 0.034 |

| Practice years | 1.54 (0.99–2.41) | 0.056 |

| Region | 1.18 (0.90–1.54) | 0.230 |

| Practice sector | 1.07 (0.53–2.13) | 0.851 |

| Proportion of patients treated for obesity | 1.07 (0.61–1.89) | 0.802 |

| Age | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.025 |

| Male gender | 0.67 (0.31–1.49) | 0.328 |

| ACC/AHA/TOS guideline | 0.67 (0.31–1.49) | 0.328 |

| Use of Saudi obesity guidelines | 0.36 (0.16–0.79) | 0.012 |

| Specialization in family medicine | 0.11 (0.32-0.40) | <0.001 |

AACE – American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ACE – American College of Endocrinology; AHA – American Heart Association; TOS – The Obesity Society; OR – odds ratio; CI – Confidence interval; OR – Odd ratio; ACC – American College of Cardiology

Table 5.

Predictors of referral to bariatric surgery (n=92)

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Obesity training | 2.20 (0.90–5.34) | 0.083 |

| Proportion of patients treated for obesity | 1.77 (0.95–3.29) | 0.070 |

| Specialization in endocrinology | 1.72 (0.65–4.55) | 0.278 |

| Use of ACC/AHA/TOS guideline | 1.64 (0.72–3.72) | 0.240 |

| Male gender | 1.27 (0.55–2.94) | 0.577 |

| Use of AACE/ACE obesity guidelines | 1.25 (0.55–2.83) | 0.596 |

| Practice sector | 1.21 (0.60–2.46) | 0.592 |

| Practice years | 1.15 (0.72–1.84) | 0.556 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.706 |

| Region | 0.95 (0.72–1.26) | 0.741 |

| Use of Saudi obesity guidelines | 0.72 (0.32–1.64) | 0.433 |

| Use of clinical judgment | 0.62 (0.27–1.43) | 0.262 |

| Specialization in family medicine | 0.49 (0.19–1.28) | 0.146 |

AACE – American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ACE – American College of Endocrinology; AHA – American Heart Association; TOS – The Obesity Society; OR – odds ratio; CI – Confidence interval; OR – Odd ratio; ACC – American College of Cardiology

Correlation between obesity managing practices

A weak positive correlation was between referrals to dietitians and referrals for bariatric surgery (r = 0.277, P = 0.007) [Figure 1]. No other correlation coefficients reached statistical significance.

Figure 1.

A heatmap showing the correlation between different practices for managing obesity

DISCUSSION

This national survey explored the perspectives and practice of healthcare providers regarding obesity management in Saudi Arabia. The respondent pool was predominantly male (64.1%) and included a wide range of ages and levels of clinical experience, which may influence clinical decision-making. Most respondents were family physicians, followed by endocrinologists, and one bariatric surgeon.

Encouragingly, approximately 92.4% of the respondents routinely counsel patients on obesity complications, reflecting physicians’ awareness of addressing obesity and its consequences. However, only half would routinely refer patients to dietitians; this is much lower than the referral rate of 83% in the USA.[21] This discrepancy between frequent counselling and lower referral rates highlights a potential gap in multidisciplinary care, especially given that the 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guidelines for overweight and obesity management recommend referral to a nutrition professional, preferably a registered dietitian, for individualized dietary counselling as part of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention.[22]

Our study reveals a divergence from ACTION IO findings, where perception of patient disinterest was a major barrier (66% in Saudi, 71% internationally), whereas only 13% of our respondents identified it as a barrier.[23,24] Time constraints were similarly significant across studies, with 37.0% in ours, underscoring the need for improved communication strategies in obesity management.[23,24]

Our study highlights the distinct approaches endocrinologists and family physicians use to manage obesity. Lifestyle modification is an integral aspect of obesity management, serving as the first step in weight loss.[1] While both family physicians and endocrinologists counseled patients on lifestyle modifications, endocrinologists were more inclined to recommend advanced strategies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and improved sleep hygiene. In similar settings, data from Sweden showed the majority of physicians feel confident in discussing lifestyle modifications with patients with obesity.[25]

Our survey highlights a significant disparity in the prescription of AOMs between clinical specialties. Compared with family physicians, who demonstrated a more conservative approach, while endocrinologists were more inclined to prescribe AOMs. This finding is consistent with prior research, which revealed that endocrinologists have the highest prescription rates among various specialties, followed by family physicians.[26,27] Endocrinologists’ higher prescription rates may stem from their specialized training and frequent management of complex obesity cases, whereas family physicians’ broader focus on general health and limited exposure to specialized treatments is likely the reason for a more conservative approach. Additionally, the endocrinologists who completed this survey were older and had more years of experience, which correlates with a greater likelihood of prescribing AOMs. This aligns with other studies suggesting a positive association between clinical experience and optimism about emerging treatments.[28] It is possible that the observed lower rates of AOM prescriptions among family physicians may, in part, be attributable to restrictions on prescribing privileges. In certain institutions, the authority to prescribe these medications is restricted to endocrinologists, a policy that likely accounts for the disparity in prescribing patterns between endocrinologists and family physicians. Moreover, the limited availability of approved AOMs in Saudi Arabia at the time, with only Orlistat mentioned in the Saudi guidelines, may have influenced prescribing practices.[20] Liraglutide, not included in the guidelines initially due to its later approval, could further explain the conservative approach observed, particularly among family physicians.[20]

In previous studies, the factors driving healthcare providers to prescribe AOMs include obesity-related complications, body weight, and the potential for improving quality of life.[28,29] Our study revealed similar findings, underscoring their importance in clinical decision-making. However, our results also reveal that barriers such as insurance coverage and medication costs significantly influence prescribing practices, particularly among endocrinologists. This may be due to the familiarity of endocrinologists with the high costs of newer treatments and their patients’ frequent need for insurance coverage to access these medications. This aligns with findings from other studies, where financial and logistical challenges were identified as critical obstacles to the broader use of AOMs.[21,26,28]

Moreover, the results of this survey indicate a preference for GLP-1 RA as first-line agents in the treatment of obesity. This mirrors findings in other studies, where the choice of GLP-1 RA is frequently guided by availability, effectiveness, and alignment with patient preferences.[21,26] These findings highlight the complex interplay between efficacy, patient-centered care, and systemic barriers in the management of obesity. However, half of the respondents reported commonly seeing patients with obesity in their clinical practice. A similar survey of primary care physicians in the USA revealed a greater proportion (77%) of patients with obesity.[29] Only 15% of respondents received obesity-focused training, with endocrinologists being more likely to have received training in obesity than family physicians. This may have contributed to the observed variability in obesity management, such as more frequent prescription of AOMs. Additionally, most participants practice in the governmental sector, unlike their counterparts abroad, who typically practice in multispecialty private settings.[26] The study provided sampling from diverse healthcare settings, such as private and governmental institutions, significantly impacting patient demographics, including educational levels and health awareness. Patients in these environments may possess varying degrees of health literacy, which can influence their understanding of medications and willingness to engage in treatment. Disinterest in medication often arises from a lack of information, fear of side effects, or past negative experiences. Including different healthcare settings in our study increases the generalizability of our findings. Taken together, these factors potentially explain the observed practice variability.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. As the research was exploratory, the generalizability and reliability of the findings may be limited. In addition, although the survey was distributed broadly through professional societies and departments to reach the target population, this approach may have introduced selection bias. In addition, reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for socially desirable responses. Finally, the relatively small sample size of the study further limits the generalizability of the findings.

Recommendations

This study highlights the need for enhanced education and training in obesity management for family physicians to improve their utilization of AOMs in patient care. Addressing systemic barriers, such as insurance coverage, medication costs, and prescription privileges, is essential for equitable access to treatment. These efforts could lead to better obesity care and help reduce obesity-related complications in Saudi Arabia.

To bridge these gaps, targeted educational programs may increase family physicians’ knowledge and confidence in the use of AOMs. Additionally, harmonizing clinical guidelines and addressing other barriers, such as insurance coverage and medication availability, are key to improving access to effective obesity treatments. Future research should explore solutions to overcome these barriers. In addition, these findings could be further complemented by studies exploring patient adherence and the outcomes associated with anti-obesity programs.

CONCLUSIONS

Our survey revealed a significant disparity in the prescription of AOMs between endocrinologists and family physicians, possibly driven by differences in training, prescription privileges, and possibly adherence to guidelines. Endocrinologists are more likely to prescribe AOMs than family physicians. Future studies should explore reasons for variability in clinical practice.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Central Ethics Committee (Approval no.: 2024-86). Completing the survey was considered consent to participate in the study. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.

Peer review

This article was peer-reviewed by two independent and anonymous reviewers.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: H.F.A, and W.A; Methodology: H.F.A, S.A, A.A.Alfadda, S.A.M, S.A.A, and W.A; Data analysis: S.A.A and A.A.Arafat; Writing–original draft preparation: H.F.A, and S.A; Writing – review and editing: All authors; Supervision: H.F.A, and W.A.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY FILES

Supplementary File 1:

Clinical Sensibility Questionnaire about the Anti-Obesity Medication survey

-

To what extent are the questions directed at important issues related to the objectives?

☐Small extent ☐Limited extent ☐Fair extent ☐Moderate extent ☐Large extent

Comments:___________________________________________________________

-

Are there important items related to the objectives that are omitted?

☐Crucial gaps ☐Important gaps ☐Minor gaps ☐Minimal gaps ☐Insignificant gaps

Comments:___________________________________________________________

-

To what extent are the response options provided simple and easily understood?

☐Small extent ☐Limited extent ☐Fair extent ☐Moderate extent ☐Large extent

Comments: ___________________________________________________________

-

To what extent are questions likely to elicit information addressing the survey objectives?

☐Small extent ☐Limited extent ☐Fair extent ☐Moderate extent ☐Large extent

Comments:____________________________________________________________

-

How many items are inappropriate or redundant?

☐Very many ☐Many ☐Some ☐A few ☐Hardly any

Comments: ___________________________________________________________

-

How likely is the Anti-Obesity Medication survey to elicit variability among the respondents?

☐Very unlikely ☐Unlikely ☐Likely ☐Quite likely ☐Very likely

Comments: ___________________________________________________________

Supplementary File 2:

Saudi Care Providers’ Opinions and Perspectives on the Effectiveness of Anti-obesity Medications (SCOPE-AM) Survey

Gender:☐ Male☐ Female

Age: .....

-

In what field did you complete sub-specialty/fellowship training? (Select all that apply)

☐ Family medicine

☐ Bariatric surgery

☐ Endocrinology

☐ Obesity

☐ Lifestyle medicine

-

How long have you been in practice (years since your completion of residency):

☐ <5 years

☐ 6-10 years

☐ >10 years

-

Your clinical practice is located in which region:

☐ Central region

☐ Eastern region

☐ Western region

☐ Northern region

☐ Southern region

-

Have you received any specialized training in obesity?

☐ No, I did not receive any specialized training in obesity medicine

☐ Yes, I completed a fellowship training in obesity medicine or bariatric surgery

☐ Yes, I completed training course(s) in obesity medicine (e.g. SCOPE)

☐ Other (please specify)

-

In your practice, what is the proportion of patients that you treat for obesity?

☐ <25%

☐ 25% to 50%

☐ 50% to 75%

☐ >75%

-

You provide care for patients with obesity in:

☐ Private sector

☐ Governmental sector

☐ Both

-

In your practice, which of the following guidelines do you implement when managing patients with obesity? (Select all that apply)

☐ Saudi clinical practice guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults

☐ American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/The Obesity society guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults

☐ American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity

☐ I use my clinical judgment

☐ Other (please specify)

-

Obesity is a chronic disease:

☐ Strongly agree

☐ Agree

☐ Neutral

☐ Disagree

☐ Strongly disagree

-

Please rank the following factors in order of how strongly you believe they predispose individuals to develop obesity, with 1 being the most significant factor and 6 being the least significant:

☐ Iatrogenic causes (e.g., medications)

☐ Diet

☐ Neuroendocrine disorders

☐ Social and behavioral factors

☐ Sedentary lifestyle

☐ Genetic factors

-

How frequently do you counsel patients with obesity-related health problems about weight loss?

☐ Always

☐ Often

☐ Sometimes

☐ Rarely

☐ Never

-

In your practice, what would be the reason(s) for not discussing obesity management with your patients? (Select all that apply)

☐ Weight is not a priority or a goal for the patient

☐ The patient has other, more serious health issues

☐ The patient has no weight-related health issues

☐ The patient is already aware of the necessary action(s) to control their weight

☐ To avoid offending the patient

☐ It is not the role of the physician to counsel on weight loss

☐ The visit duration is too short

☐ No or limited insurance coverage

☐ I always counsel my patients about weight loss

-

In your practice, what is the target percentage of weight reduction for patients with obesity?

☐ 5% of starting weight

☐ 10% of starting weight

☐ 15% or more of starting weight

☐ The target depends on the presence or absence of comorbidities

☐ Other (please specify)

-

How frequently do you counsel patients with obesity on lifestyle modification?

☐ Always

☐ Often

☐ Sometimes

☐ Rarely

☐ Never

-

In your practice, which lifestyle modification(s) would you recommend for patients with obesity? (Select all that apply.)

☐ Dietary intervention

☐ Regular physical activity

☐ Cognitive behavioral therapy

☐ Recommend sleep hygiene

☐ Other (please specify)

-

How frequently do you refer patients with obesity to dietitians?

☐ Always

☐ Often

☐ Sometimes

☐ Rarely

☐ Never

-

In your practice, how frequently do you prescribe anti-obesity medication for patients with obesity?

☐ Always

☐ Often

☐ Sometimes

☐ Rarely

☐ Never

-

For what indication(s) do you prescribe anti-obesity medications for patients with obesity? (Select all that apply)

☐ Adults with BMI >30 kg/m2

☐ Adults with BMI of 27 to 29.9 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities

☐ Adults who have not met weight loss goals (loss of at least 5% of total body weight at 3 to 6 months) with a comprehensive lifestyle intervention

☐ Adults with significant weight regain following bariatric surgery

☐ Based on patients’ preferences

☐ Other (please specify)

-

In your practice, how frequently do you refer patients for or advise them about bariatric surgery?

☐ Always

☐ Often

☐ Sometimes

☐ Rarely

☐ Never

-

For what indication(s) do you refer patients for or advise them about bariatric surgery? (Select all that apply)

☐ Adults with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 regardless of comorbidities

☐ Adults with BMI ≥35 kg/m2 regardless of comorbidities

☐ Adults with BMI ≥35 kg/m2 and 1 or more obesity-related comorbidity

☐ Adults with BMI between 30 and 34.9 kg/m2 and type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome

☐ Adults with BMI 30 and 34.9 kg/m2 who cannot achieve sustainable weight loss or comorbidity improvement with nonsurgical weight loss methods

☐ Adults with BMI ≥27.5 kg/m2 for a specific race

☐ Other (please specify)

-

Which classes of anti-obesity medications do you prescribe to patients with obesity? (Select all that apply)

☐ Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist

☐ Dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist

☐ Phentermine-Topiramate

☐ Orlistat

☐ Bupropion-naltrexone

☐ Phentermine (as a single agent)

☐ Topiramate (as a single agent)

☐ Other (please specify)

-

Which of the following factor(s) influence your choice of anti-obesity medication (select all that apply):

☐ Patient’s BMI

☐ Obesity-related complications

☐ Patient comorbidities

☐ Patient preferences

☐ Medication side effects

☐ Insurance coverage

☐ Medication costs

☐ Medication availability at your institution

☐ Prescription privileges

☐ Other (please specify)

-

Which of the following is your first-line agent for obesity management?

☐ Liraglutide

☐ Semaglutide

☐ Tirzepatide

☐ Phentermine-Topiramate

☐ Orlistat

☐ Combination bupropion-naltrexone

☐ Phentermine (as a single agent)

☐ Other (please specify).

-

Which of the following factors influence your choice of GLP-1 agonist or dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist? (Select all that apply)

☐ Availability

☐ Effectiveness

☐ Patient preference

☐ Adverse effects

☐ Dosing frequency (i.e., once weekly, once daily)

-

Have you discontinued GLP-1 agonists or dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist due to side effects?

☐ Yes

☐ No

-

If yes, which side effect(s) prompted you to discontinue GLP-1 agonists or dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist? (select all that apply)

☐ Hypoglycemia

☐ Diarrhea

☐ Severe nausea and vomiting

☐ Hypersensitivity reaction

☐ Acute pancreatitis

☐ Alopecia

☐ Other (please specify)

-

Do you believe that a large randomized clinical trial in Saudi Arabia examining the efficacy and safety of different GLP-1 medications would influence your future practice?

☐ Yes

☐ No

Supplementary File 3

Checklist for reporting of survey studies checklist

| Section/topic | Item | Item description | Reported on page number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | |||

| Title and abstract | 1a | State the word “survey” along with a commonly used term in title or abstract to introduce the study’s design | 3 |

| 1b | Provide an informative summary in the abstract, covering background, objectives, methods, findings/results, interpretation/discussion, and conclusions | 3 | |

| Introduction | |||

| Background | 2 | Provide a background about the rationale of study, what has been previously done, and why this survey is needed | 5 |

| Purpose/aim | 3 | Identify specific purposes, aims, goals, or objectives of the study | 5 |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Specify the study design in the methods section with a commonly used term (e.g., cross-sectional or longitudinal) | 7 |

| 5a | Describe the questionnaire (e.g., number of sections, number of questions, number and names of instruments used) | 7 | |

| Data collection methods | 5b | Describe all questionnaire instruments that were used in the survey to measure particular concepts. Report target population, reported validity and reliability information, scoring/classification procedure, and reference links (if any) | 7 |

| 5c | Provide information on pretesting of the questionnaire, if performed (in the article or in an online supplement). Report the method of pretesting, number of times questionnaire was pretested, number and demographics of participants used for pretesting, and the level of similarity of demographics between pre-testing participants and sample population | NA | |

| 5d | Questionnaire if possible, should be fully provided (in the article, or as appendices or as an online supplement) | Supplementary File 2 | |

| Sample characteristics | 6a | Describe the study population (i.e., background, locations, eligibility criteria for participant inclusion in survey, exclusion criteria) | 7 |

| 6b | Describe the sampling techniques used (e.g., single stage or multistage sampling, simple random sampling, stratified sampling, cluster sampling, convenience sampling). Specify the locations of sample participants whenever clustered sampling was applied | 7 | |

| 6c | Provide information on sample size, along with details of sample size calculation | 7 | |

| 6d | Describe how representative the sample is of the study population (or target population if possible), particularly for population-based surveys | 7 | |

| Survey administration | 7a | Provide information on modes of questionnaire administration, including the type and number of contacts, the location where the survey was conducted (e.g., outpatient room or by use of online tools, such as SurveyMonkey) | 8 |

| 7b | Provide information of survey’s time frame, such as periods of recruitment, exposure, and follow-up days | 8 | |

| 7c | Provide information on the entry process For nonweb-based surveys, provide approaches to minimize human error in data entry For web-based surveys, provide approaches to prevent “multiple participation” of participants |

8 | |

| Study preparation | 8 | Describe any preparation process before conducting the survey (e.g., interviewers’ training process, advertising the survey) | 5 |

| Ethical considerations | 9a | Provide information on ethical approval for the survey if obtained, including informed consent, IRB approval, Helsinki declaration, and GCP declaration (as appropriate) | 8 |

| 9b | Provide information about survey anonymity and confidentiality and describe what mechanisms were used to protect unauthorized access | 8 | |

| Statistical analysis | 10a | Describe statistical methods and analytical approach. Report the statistical software that was used for data analysis | 9 |

| 10b | Report any modification of variables used in the analysis, along with reference (if available) | NA | |

| 10c | Report details about how missing data was handled. Include rate of missing items, missing data mechanism (i.e., MCAR, MAR or MNAR) and methods used to deal with missing data (e.g., multiple imputation) | 9 | |

| 10d | State how non-response error was addressed | NA | |

| 10e | For longitudinal surveys, state how loss to follow-up was addressed | NA | |

| 10f | Indicate whether any methods such as weighting of items or propensity scores have been used to adjust for non-representativeness of the sample | NA | |

| 10g | Describe any sensitivity analysis conducted | NA | |

| Results | |||

| Respondent characteristics | 11a | Report numbers of individuals at each stage of the study. Consider using a flow diagram, if possible | 10 |

| 11b | Provide reasons for nonparticipation at each stage, if possible | NA | |

| 11c | Report response rate, present the definition of response rate or the formula used to calculate response rate | NA | |

| 11d | Provide information to define how unique visitors are determined. Report number of unique visitors along with relevant proportions (e.g., view proportion, participation proportion, completion proportion) | 10 | |

| Descriptive results | 12 | Provide characteristics of study participants, as well as information on potential confounders and assessed outcomes | 10 |

| Main findings | 13a | Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates along with 95% CIs and P values | 11 |

| 13b | For multivariable analysis, provide information on the model building process, model fit statistics, and model assumptions (as appropriate) | NA | |

| 13c | Provide details about any sensitivity analysis performed. If there are considerable amount of missing data, report sensitivity analyses comparing the results of complete cases with that of the imputed dataset (if possible) | NA | |

| Discussion | |||

| Limitations | 14 | Discuss the limitations of the study, considering sources of potential biases and imprecisions, such as non-representativeness of sample, study design, important uncontrolled confounders | 15 |

| Interpretations | 15 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results, based on potential biases and imprecisions and suggest areas for future research | 16 |

| Generalizability | 16 | Discuss the external validity of the results | NA |

| Other sections | |||

| Role of funding source | 17 | State whether any funding organization has had any roles in the survey’s design, implementation, and analysis | NA |

| Conflict of interest | 18 | Declare any potential conflict of interest | NA |

| Acknowledgements | 19 | Provide names of organizations/persons that are acknowledged along with their contribution to the research | NA |

NA – Not available; MNAR – Missing not at random; MAR – Missing at random; MCAR – Missing completely at random; CI – Confidence interval; IRB – Institutional review board; GCP – Good clinical practice

Funding Statement

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Safaei M, Sundararajan EA, Driss M, Boulila W, Shapi’i A. A systematic literature review on obesity: Understanding the causes and consequences of obesity and reviewing various machine learning approaches used to predict obesity. Comput Biol Med. 2021;136:104754. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salem V, AlHusseini N, Abdul Razack HI, Naoum A, Sims OT, Alqahtani SA. Prevalence, risk factors, and interventions for obesity in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13448. doi: 10.1111/obr.13448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health (MOH) Riyadh: Ministry of Health; 2019. Statistical Yearbook 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health (MOH) Riyadh: Ministry of Health; 2020. World Health Survey Saudi Arabia (KSAWHS) 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Saudi Health Interview Survey Results. Available from: https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/Projects/KSA/Saudi-Health-Interview-Survey-Results.pdf. [Last accessed May 14, 2025]

- 6.World Health Organization WHO Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501491. [Last accessed May 14, 2025]

- 7.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2014. Noncommunicable Diseases Global Monitoring Framework: Indicator Definitions and Specifications. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2020. The Global Health Observatory. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coker T, Saxton J, Retat L, Alswat K, Alghnam S, Al-Raddadi RM, et al. The future health and economic burden of obesity-attributable type 2 diabetes and liver disease among the working-age population in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0271108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novograd J, Mullally JA, Frishman WH. Tirzepatide for weight loss: Can medical therapy “outweigh” bariatric surgery? Cardiol Rev. 2023;31:278–83. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, Epstein L, Goodpaster B, Hall KD, et al. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:7–15. doi: 10.1002/oby.20967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squadrito F, Rottura M, Irrera N, Minutoli L, Bitto A, Barbieri MA, et al. Anti-obesity drug therapy in clinical practice: Evidence of a poor prescriptive attitude. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128:110320. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ard J, Fitch A, Fruh S, Herman L. Weight loss and maintenance related to the mechanism of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. Adv Ther. 2021;38:2821–39. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, Meade MO, Adhikari NK, Sinuff T, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179:245–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SurveyMonkey Inc San Mateo, California, USA1999–2024. Available from: https://www.surveymonkey.com . [Last accessed May 25, 2025]

- 18.Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, Nam NH, Ng SJ, Abbas KS, et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS) J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:3179–87. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06737-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203. doi: 10.4158/EP161365.GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alfadda AA, Al-Dhwayan MM, Alharbi AA, Al Khudhair BK, Al Nozha OM, Al-Qahtani NM, et al. The Saudi clinical practice guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Saudi Med J. 2016;37:1151–62. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.10.14353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshman L, Othman A, Furst W, Heisler M, Kraftson A, Zouani Y, et al. Primary care providers’ perceived barriers to obesity treatment and opportunities for improvement: A mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alfadda AA, Al Qarni A, Alamri K, Ahamed SS, Abo’ouf SM, Shams M, et al. Perceptions, attitudes, and barriers toward obesity management in Saudi Arabia: Data from the ACTION-IO study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:166–72. doi: 10.4103/sjg.sjg_500_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caterson ID, Alfadda AA, Auerbach P, Coutinho W, Cuevas A, Dicker D, et al. Gaps to bridge: Misalignment between perception, reality and actions in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1914–24. doi: 10.1111/dom.13752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrasco D, Thulesius H, Jakobsson U, Memarian E. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes about obesity, adherence to treatment guidelines and association with confidence to treat obesity: A Swedish survey study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:208. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01811-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garvey WT, Mahle CD, Bell T, Kushner RF. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and management of obesity and knowledge of glucagon, GLP–1, GIP receptor agonists, and dual agonists. Obes Sci Pract. 2024;10:e756. doi: 10.1002/osp4.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaduganathan M, Patel RB, Singh A, McCarthy CP, Qamar A, Januzzi JL, Jr., et al. Prescription of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists by cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1596–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahan S, Kumar R, Ahmad N, Dunn J, Sims T, Mackie D, et al. Abstract #1495502: Healthcare providers’ perceptions of anti-obesity medications: Results from the OBSERVE study. Endocr Pract. 2023;29:S127. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadel K, Lee ME, An A, Limketkai B, Pickett-Blakely O, Yeung M, et al. S1630 perceptions and comfort status in prescribing anti-obesity medications: A multi-center survey among gastroenterologists and primary care physicians. Official J Am Coll Gastroenterol. 2023;118:S1222–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.