Abstract

Background:

Perceived social support represents a key factor influencing both mental and physical health, yet brief Arabic measures are scarce.

Objectives:

To assess the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the abbreviated 6-item Medical Outcomes Study–Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS-6) among Saudi adults.

Methods:

An online questionnaire was distributed via social media platforms to assess perceived social support, psychological distress, quality of life (QoL), and coping. Cronbach’s alpha (α), McDonald’s omega (ω), and corrected item-total correlations were used to evaluate the scale’s reliability. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on 50% of the sample, using maximum likelihood with varimax rotation to identify factor structure. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) validated the model in the other 50%, with fit assessed through RMSEA, SRMR, CFI, TLI, and other indices. Concurrent validity was evaluated through Pearson’s correlations with relevant psychological measures.

Results:

A total of 1028 Saudi adults completed the questionnaire. Suitability of the data for EFA was supported by a strong KMO value (0.83) and significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (P < 0.001). Parallel analysis indicated that a three-factor solution was optimal, explaining 80% of the variance. CFA confirmed this model with excellent fit indices (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.02, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.95). Negative relationships with depression (r = −0.24, P < 0.01) and anxiety (r = −0.17, P < 0.01), and a positive correlation with QoL (r = 0.37, P < 0.01) and adaptive coping strategies provided evidence for concurrent validity. The Arabic MOS-SSS-6 exhibited high internal consistency (α = 0.90, ω = 0.90).

Conclusions:

The Arabic MOS-SSS-6 is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring perceived social support among Saudi adults, demonstrating significant correlations with psychological variables relevant for psychological assessments and interventions.

Keywords: Arabic, Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey, perceived social support

INTRODUCTION

Social support is a multidimensional concept and a crucial construct in psychological research,[1] influencing both mental and physical health.[2,3] A recent meta-analysis found strong correlations between social support and psychological adjustment (r = 0.24; 95% 0.22-0.26) across various outcome categories, including mental health, and specific outcomes, including depression and stress.[2] Both direct and/or buffering mechanisms for this effect are plausible. In fact, a study that included people with HIV/AIDS found that social support had both direct and buffering effects. It showed that perceived social support was directly associated with enhanced health-related quality of life (QoL),[4] and indirectly in reducing depressive symptoms.[4] Another study demonstrated that social support mediates the relationship between loneliness and depression in community-dwelling older adults.[5]

Social support is commonly categorized into structural and functional dimensions. Structural support pertains to the diversity of social roles and relationships within one’s social network, while functional support includes received social support (i.e., tangible aspects of social networks such as size and composition), and perceived social support (i.e., an individual’s belief or perception that support is available and accessible, when needed).[1,6] Research indicates that perceived social support is more strongly associated with psychological adjustment[2] and serves as a better predictor of well-being outcomes compared to received social support.[7]

Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) is a 19-item multidimensional tool that is widely used to measure perceived social support.[8] It measures four dimensions: affectionate support (i.e., expression of affection and love), emotional-informational support (i.e., empathetic listening, encouragement to express emotions, and provision of advice and feedback), tangible support (i.e., provision of concrete assistance or resources, such as financial aid or practical help with tasks), and positive social interactions (i.e., availability of companions who can participate in fun and enjoyable activities).[8] MOS-SSS is used in longitudinal studies[9,10] and among various populations, including patients with chronic illnesses,[11] caregivers,[12] veterans,[13] and students.[14]

A recent review identified that there are 11 versions of MOS-SSS are available for various populations and cultures.[15] This review found that while the 19-item four-factor MOS-SSS is the most common, its factor structure varies across cultures and contexts (3–5 factors using exploratory factor analysis [EFA] and 2–5 factors using confirmatory factor analysis [CFA]). This finding underscores the importance of adhering to the standard scale translation and validation procedures.[15] Furthermore, the MOS-SSS is currently available in 14 different languages,[15] including Arabic. Dafaalla et al.[16] administered the Arabic MOS-SSS-19 among a sample of 487 Sudanese medical students and found that the Arabic version was reliable (Cronbach’s α was 0.93 for the overall MOS-SSS score). For validity, analysis revealed four factors, accounting for 72% of the variance.[16] Alaloul et al.[17] also validated the Arabic MOS-SSS-19 in a sample of Jordanian cancer survivors, confirming the four-factor model with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.82 to 0.93). Their analysis established convergent validity through significant correlations with QoL measures.[17]

Shortened forms with sound psychometric properties are valuable for reducing response burden, especially in epidemiological and longitudinal studies. Holden et al.[18] developed and validated a short 6-item MOS-SSS version using two large cohorts of Australian women. The MOS-SSS-6 was shown to have high internal consistency, good construct validity (factor loadings onto the total score ranging from 0.55 to 0.89, with all fit indices being satisfactory) and criterion validity (r = 0.97 between the MOS-SSS-19 and MOS-SSS-6 total scores), and moderate concurrent validity (moderate correlations with health and social indicators including physical and emotional well-being, optimism, life satisfaction, and loneliness).[18]

Considering that the factor structure of the original MOS-SSS-19 varies across different cultures and contexts,[15] it is not surprising that abbreviated versions of the MOS-SSS may also differ in the number of items and factors included. For example, existing English and Spanish abbreviated forms include 4-, 8-, and 12-item versions[19,20,21] as well as 6- and 8-item versions, respectively.[22] While the original MOS-SSS-19 is available in Arabic, abbreviated forms also need to be evaluated in the desired language, culture, and context. Therefore, this research aims to evaluate the reliability and factor structure of the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 among Saudi adults. Brief and psychometrically sound measures are necessary so that researchers, psychologists, and social workers can assess perceived social support in longitudinal studies and community and clinical settings.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

A convenience sample of Saudi adults, aged ≥18 years, participated in this cross-sectional online study. Participants were recruited online through an anonymous online link shared on the authors’ social media accounts. Participants accessed the survey through a hyperlink and completed the survey using Google Forms. All items in the questionnaire were mandatory, ensuring that responses could only be submitted after all questions were answered. Participation was entirely voluntary, and each participant provided electronic informed consent. This research received approval from the Research Ethics Committee at University of Ha’il. All procedures followed were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.

Measures

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was assessed using the MOS-SSS-6, which includes four dimensions: emotional-information support (2 items), tangible support (2 items), affectionate support (1 item), and positive social interactions (1 item).[18] Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time), yielding a total score from 6 to 30. Higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. The English MOS-SSS-6 has shown satisfactory psychometric properties.[18] The current study used the 6 items for the brief version from the original Arabic MOS-SSS-19 version.[16]

Other relevant measures

Psychological distress was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),[23] which includes 14 items: 7 for anxiety (HADS-A) and 7 for depression (HADS-D). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with six items requiring reverse scoring. Total scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress. The HADS has shown satisfactory psychometric properties across various populations, including Arabic-speaking samples.[24,25,26,27,28] The current study used the Arabic version of the HADS.[28]

Quality of life was measured using the European Health Interview Survey-Quality of Life (EUROHIS-QOL),[29] a brief 8-item scale based on the WHOQOL-BREF,[30] scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The overall score, ranging from 8 to 40, indicates better QoL at higher scores, with the scale demonstrating good psychometric qualities in multiple countries.[29] Additionally, the parent Arabic version of the EUROHIS-QOL, the WHOQOL-BREF, has also demonstrated adequate psychometric properties.[31,32]

Coping strategies were evaluated using the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief COPE),[33] a 28-item multidimensional scale that assesses adaptive and maladaptive strategies. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale, and the Brief COPE includes 14 subscales (e.g., self-distraction, denial, and emotional support), each with 2 items. The scale has established validity and reliability, with the Arabic version also found to be a reliable measure.[33,34]

Data analysis

Participants’ characteristics were summarized using mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) for numeric variables, and categorical variables using frequency and percentage. Assumptions necessary for both EFA and CFA including multivariate normality and multicollinearity were assessed and met (e.g., skewness values <−0.5; kurtosis values were primarily below 0, indicating platykurtic distributions).[35] Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s omega (ω) coefficients and corrected item-total correlations.[36,37] A α and ω coefficient of 0.70 or above, along with an item-total correlation greater than 0.30, was considered acceptable.

To assess the underlying factor structure, EFA was conducted on a random subset comprising 50% of the data. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were employed to evaluate the suitability of the data for factor analysis. KMO values exceeding 0.6 and a significant Bartlett’s test (P < 0.05) confirmed adequacy of the data. The number of factors was determined using Horn’s parallel test and inspection of the scree plot.[38] Maximum likelihood method was used to extract factors, followed by varimax rotation. Factor loadings ≥0.40 were considered significant for item retention.[39]

CFA was performed on the remaining 50% of the data to validate the factor structure identified in EFA. The lavaan package in R was utilized to fit the CFA model, and maximum likelihood estimation was applied. Model fit was assessed using multiple indices, including the Chi-square statistic (χ2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 95% confidence interval (CI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Cutoff values of RMSEA <0.06, SRMR <0.08, and CFI/TLI ≥0.95 were considered indicative of good model fit. Additionally, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), consistent Akaike information criterion (CAIC), and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were evaluated to further validate model fit.[40] Finally, Pearson’s correlations with a 95% confidence interval (CI) between the MOS-SSS-6 and related psychological measures were calculated to provide evidence for concurrent validity. All the analyses were performed using R statistical programming (version 4.4.1).

RESULTS

A total of 1028 adult participants were included in this study, with a mean age of 33.7 years (SD = 11.5). Most participants were male (52.7%), married (54.3%), and with at least a bachelor’s degree (50.7%). Regarding occupational status, the majority of participants were employed (47.2%), followed by students (30.2%), unemployed (16.4%), and retirees (6.1%).

Internal consistency reliability

The reliability of the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 is demonstrated by its high internal consistency (α = 0.90 and ω = 0.90). These coefficients indicate strong inter-item correlations, confirming the scale’s effectiveness in measuring the construct of perceived social support. Internal consistency of the individual factors was also within the acceptable range (for emotional-informational support, α = 0.78; for tangible support, α =0.90). Additionally, as shown in Table 1, the corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.64 to 0.78, suggesting that all items contribute meaningfully to the overall construct. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 has adequate internal consistency and is a reliable measure for assessing perceived social support among Saudi adults.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and standardized factor loading for the Arabic Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey-6 version

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach’s α if item deleted | α | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived social support | |||||

| MOS-SSS1 | 3.49 (1.35) | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.90 | |

| MOS-SSS2 | 3.51 (1.33) | 0.75 | 0.88 | ||

| MOS-SSS3 | 3.68 (1.33) | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.78 | |

| MOS-SSS4 | 4.04 (1.23) | 0.64 | 0.89 | ||

| MOS-SSS5 | 3.98 (1.28) | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.88 | |

| MOS-SSS6 | 3.91 (1.28) | 0.76 | 0.88 | ||

| MOS-SSS-6 total score | 22.62 (6.34) | 0.90 | 0.90 | ||

| Psychological distress | |||||

| HADS-anxiety | 4.93 (4.22) | 0.86 | 0.86 | ||

| HADS-depression | 5.72 (4.18) | 0.80 | 0.79 | ||

| HADS total score | 10.65 (7.67) | 0.89 | 0.89 | ||

| QoL | |||||

| EUROHIS-QOL-8 | 31.32 (6.33) | 0.87 | 0.87 | ||

| Coping domains | |||||

| Self-distraction | 3.13 (1.76) | ||||

| Active coping | 3.82 (1.68) | ||||

| Denial | 2.06 (1.89) | ||||

| Substance use | 0.40 (1.20) | ||||

| Emotional support | 2.63 (1.84) | ||||

| Informational support | 2.43 (1.91) | ||||

| Behavioral disengagement | 1.92 (1.74) | ||||

| Venting | 2.35 (1.69) | ||||

| Positive reframing | 3.71 (1.77) | ||||

| Planning | 3.73 (1.75) | ||||

| Humor | 1.84 (1.81) | ||||

| Acceptance | 4.41 (1.65) | ||||

| Religion | 4.58 (1.73) | ||||

| Self-blame | 1.95 (1.88) | ||||

| Brief COPE total score | 38.97 (14.23) | 0.89 | 0.88 |

SD – Standard deviation; α – Cronbach alpha; ω – McDonald omega; MOS-SSS-6 – Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey; HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; QoL – Quality of life; EUROHIS-QOL-8 – European Health Interview Survey-Quality of Life; Brief COPE – Abbreviated version of the coping orientation to problems experienced inventory

Exploratory factor analysis

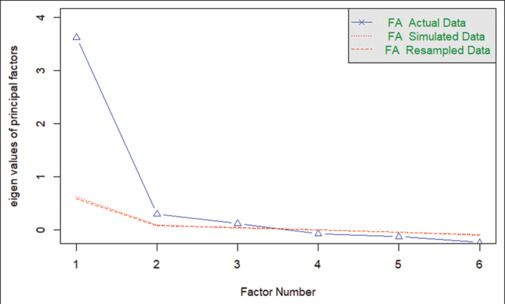

Using the first subset of the data (n = 514), the overall KMO value was 0.83 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (P < 0.001), indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Individual KMO values for each variable ranged from 0.77 to 0.88, demonstrating acceptable sampling adequacy across all items. Parallel analysis indicated that a three-factor solution was optimal, as eigenvalues for the first three factors exceeded the randomly generated eigenvalues [Figure 1]. These three factors accounted for 80% of the total variance. The factor loadings for each item are presented in Table 2. Items MOS-SSS 1 and 2 loaded strongly onto factor 1 “tangible support,” whereas items MOS-SSS 3 and 4 loaded strongly onto factor 2 “emotional-informational support” and MOS-SSS 5 and 6 loaded strongly to factor 3 “affectionate and positive social interaction.”

Figure 1.

Scree plot displaying the eigenvalues of the factors derived from exploratory factor analysis of the Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey-6

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the exploratory factor analysis of the Arabic Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey-6

| Item | Factor 1 (tangible support) | Factor 2 (emotional-informational support) | Factor 3 (affectionate and positive social interaction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOS-SSS1 | 0.94 | 0.17 | 0.30 |

| MOS-SSS2 | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.35 |

| MOS-SSS3 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.38 |

| MOS-SSS4 | 0.19 | 0.93 | 0.32 |

| MOS-SSS5 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.76 |

| MOS-SSS6 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

MOS-SSS-6 – Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey

Confirmatory factor analysis

The three-factor structure identified in the EFA was tested using CFA on the second subset of the data (n = 514). Several goodness-of-fit indices were calculated, and the result indicate that the model fit was acceptable (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.07 [90% CI: 0.04–0.10], SRMR = 0.02, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.95, BIC = 8538.9, CAIC = 8475.3). Almost all indices are within the recommended thresholds, indicating an excellent model fit. The BIC and CAIC were within acceptable limits, with no alternative model exhibiting a significantly lower BIC (ΔBIC ≥ 10). All items loaded significantly onto their respective factors (P < 0.001). Standardized factor loadings are shown in Table 3. A path diagram of the CFA model is presented in Figure 2, highlighting the relationships between the observed variables and latent constructs.

Table 3.

Standardized factor loadings of the confirmatory factor analysis of the Arabic Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey-6

| Items | Factor | Standardized loading (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| MOS-SSS1 | 1 | 0.88 (0.84–0.91) |

| MOS-SSS2 | 1 | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) |

| MOS-SSS3 | 2 | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) |

| MOS-SSS4 | 2 | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) |

| MOS-SSS5 | 3 | 0.90 (0.87–0.92) |

| MOS-SSS6 | 3 | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) |

MOS-SSS-6 – Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey; CI – Confidence interval

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the confirmatory factor analysis model for the Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey-6 Arabic (n = 514). Latent variables (Fc1, Fc2, and Fc3) are depicted as circles, and observed variables (SS1–SS6) are shown as rectangles. Single-headed arrows indicate standardized factor loadings, while double-headed arrows represent correlations between latent variables

Concurrent validity

To assess the concurrent validity of the Arabic MOS-SSS-6, correlational analyses with related constructs including psychological distress, QoL, and coping strategies were conducted [Table 4]. Analysis showed significant negative correlations between the MOS-SSS-6 and depressive symptoms (r = −0.24, 95% CI: −0.30, −0.18; P < 0.01) and anxiety symptoms (r = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.22, −0.11, P < 0.01) and significant positive correlation with QoL (r = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.32, 0.42; P < 0.01). Higher levels of perceived social support were significantly associated with lower levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as better QoL.

Table 4.

Person’s correlations with related variables

| Scale | MOS-SSS-6 | HADS-anxiety | HADS-depression |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOS-SSS-6 | - | ||

| HADS-anxiety | −0.17 (−0.22–−0.11)** | - | |

| HADS-depression | −0.24 (−0.30–−0.18)** | 0.70 (0.67–0.73)** | - |

| EUROHIS-QOL-8 | 0.37 (0.32–0.42)** | −0.53 (−0.57–−0.48)** | −0.59 (−0.62–−0.54)** |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). MOS-SSS-6 – Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey; HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; EUROHIS-QOL-8 – European Health Interview Survey-Quality of Life

With regards to the coping domains, as assessed by the Brief COPE,[33] MOS-SSS-6 correlated with various coping domains that aligned with expectations. Specifically, MOS-SSS-6 showed positive correlations with active coping (r = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.30; P < 0.001), emotional support (r = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.29, 0.40; P < 0.001), informational support (r = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.29; P < 0.001), positive reframing (r = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.27; P < 0.001), planning (r = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.27; P < 0.001), humor (r = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.14; P = 0.007), acceptance (r = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.19, 0.30; P < 0.001), and religion (r = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.21; P < 0.001). Conversely, negative correlations were found with maladaptive coping strategies, including self-distraction (r = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.22, −0.10; P < 0.001), denial (r = −0.01, 95% CI: −0.07, 0.05; P = 0.657), behavioral disengagement (r = −0.02, 95% CI: −0.08, 0.04; P = 0.534), venting (r = -0.07, 95% CI: −0.13, 0.01; P = 0.016), and self-blame (r = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.14, −0.02; P = 0.07). These findings underscore the role of social support in facilitating adaptive coping mechanisms while concurrently mitigating reliance on less effective strategies.

DISCUSSION

This study explored the psychometric properties of the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 among a large sample of Saudi adults. The findings indicate that the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 is a reliable and valid measure of perceived social support, which are critical for ensuring accurate assessments in both research and clinical settings in the Saudi context. Overall, the strong internal consistency coefficients underscore the measure’s robustness, while significant correlations with psychological distress, QoL, and coping strategies highlight the relevance and importance of perceived social support as a key factor influencing mental health outcomes.

The current study found that the internal consistency of the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 was high, with α and ω both 0.90, and the corrected item-total correlations were strong (ranging from 0.64 to 0.78), reflecting that all items contribute meaningfully to the overall construct. This finding aligns with previous research, supporting the reliability of MOS-SSS across various cultural contexts. For instance, previous research has reported acceptable reliability coefficients, α ranging between 0.70 and 0.81 among two large cohorts of Australian women,[18] and α of 0.85 in a sample of recently diagnosed cancer patients for the English version of the MOS-SSS-6.[22] Additionally, validation studies with Arabic-speaking samples have reported strong internal consistency (α = 0.93) for the Arabic MOS-SSS-19.[16,17] Overall, the findings demonstrated that the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 is a reliable tool for measuring perceived social support among Saudi adults.

Regarding the factorial structure of the MOS-SSS-6, the EFA yielded a three-factor structure, which was further supported by the CFA. The three-factor Arabic MOS-SSS-6 exhibited excellent fit indices, which are consistent with the original MOS-SSS-6 English version and previous research.[18,22] This structure aligns with theoretical frameworks that view social support as a multidimensional construct, encompassing various forms of assistance and interpersonal connections.[8,41] The first factor, tangible support, included items like “someone to help you if you were confined to bed” and “someone to take you to the doctor if you needed it,” reflecting the provision of practical or logistical aid, which is crucial during times of physical need or recovery.[42] The second factor, emotional-informational support, captured items such as “someone to share your most private worries and fears with” and “someone to turn to for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem,” emphasizing empathy, encouragement, and guidance. These elements are vital for fostering emotional well-being and providing actionable advice during challenging situations.[43] The third factor, affectionate support/positive social interaction, included items like “someone to love and make you feel wanted” and “someone to do something enjoyable with,” highlighting the importance of close, loving relationships and shared enjoyable experiences. These aspects are essential for emotional fulfillment, happiness, and QoL.[44]

It is important to note that while there are other abbreviated forms of the MOS-SSS including 4-, 8-, and 12-item versions,[19,20,21] the methods employed for items selection vary. For instance, Gómez-Campelo et al.[20] and Moser et al.[21] selected the first eight items listed, which measure “tangible support”. As such, other dimensions of perceived social support, such as affectionate support and emotional-informational support,[8] are not represented in these abbreviated forms. On the other hand, item selection for the MOS-SSS-6 English version was based on factor structure derived from previous studies and it was validated in two nationally representative Australian cohorts of women across various age groups, making it suitable for population-based research.[18]

Concurrent validity of the Arabic MOS-SSS-6 was supported through significant correlations with psychological distress, QoL, and coping strategies. Notably, higher perceived social support was associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression, echoing findings from existing literature that emphasizes the protective role of social support against mental health issues.[2] This relationship is notably critical in the context of Saudi Arabia, where social structures and familial ties play a pivotal role in individual well-being. Moreover, the positive correlation between perceived social support and QoL highlights the importance of social networks in enhancing life satisfaction and emotional health. This finding resonates with the work of Bekele et al.,[4] which illustrated that effective social support mechanisms could significantly improve health-related QoL. Higher perceived social support was correlated with active coping and emotional support, suggesting that individuals with robust social networks are more likely to engage in effective coping mechanisms when faced with stressors.

This study has several implications. First, selection of the specific version of the MOS-SSS should be based on the aim of the assessment. The abbreviated 6-item MOS-SSS is particularly useful for quickly assessing global perceived social support. This approach allows researchers and clinicians to efficiently assess social support, saving time and reducing the burden on participants and patients. However, if the aim is to obtain a comprehensive assessment of perceived social support, researchers should use the extended version of the MOS-SSS-19. Second, given that perceived social support is linked to psychological adjustment,[2] routine assessment of perceived social support could help to detect individuals at risk of developing psychological problems due to low social support levels, thus enabling referral to the appropriate social support services.

Strengths and limitations

In terms of strengths, the original MOS-SSS-6 English version was developed and validated using large cohorts of only Australian women,[18] while the current study included both men and women. A major limitation of the study is that while the large sample size employed in the current study enhances the robustness of our findings, the use of convenience and snowball sampling may have introduced biases that may affect generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS

The Arabic version of the MOS-SSS-6 is a reliable and valid tool for measuring perceived social support among the general adult Saudi population. Future research should focus on further evaluating its psychometric properties in clinical samples.

Ethical considerations

This research received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of University of Ha’il (IRB 41–00155). All procedures followed were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013. All individual participants included in this study provided electronic informed consent.

Peer review

This article was peer-reviewed by two independent and anonymous reviewers.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.M.A. and A.A.A.; Methodology: M.M.A. and A.A.A.; Data analysis: M.M.A.; Writing–original draft preparation: M.M.A.; Writing – review and editing: M.M.A. and A.A.A.; Supervision: M.M.A. and A.A.A.

Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen S. Stress, social support, and disorder. In: Veiel HO, Baumann U, editors. The Meaning and Measurement of Support. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corp; 1992. pp. 109–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zell E, Stockus CA. Social support and psychological adjustment: A quantitative synthesis of 60 meta-analyses. Am Psychol. 2025;80:33–46. doi: 10.1037/amp0001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, Greene S, Sobota M, Koornstra J, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25:337–46. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.701716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautam S, Poudel A, Khatry RA, Mishra R. The mediating role of perceived social support on loneliness and depression in community-dwelling Nepalese older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:854. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05461-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wills TA, Shinar O. Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2000. Measuring perceived and received social support; pp. 86–135. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(Suppl 1):25–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1023509117524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin C, Tooth LR, Xu X, Mishra GD. Associations between factors in childhood and young adulthood and childlessness among women in their 40s: A national prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2024;360:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman MM, David M, Steinberg J, Cust A, Yu XQ, Rutherford C, et al. Association of optimism and social support with health-related quality of life among Australian women cancer survivors – A cohort study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2025;21:221–31. doi: 10.1111/ajco.14079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams JS, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Gender invariance in the relationship between social support and glycemic control. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0285373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cumming TB, Cadilhac DA, Rubin G, Crafti N, Pearce DC. Psychological distress and social support in informal caregivers of stroke survivors. Brain Impair. 2008;9:152–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards ER, Dichiara A, Gromatsky M, Tsai J, Goodman M, Pietrzak R. Understanding risk in younger Veterans: Risk and protective factors associated with suicide attempt, homelessness, and arrest in a nationally representative Veteran sample. Mil Psychol. 2022;34:175–86. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2021.1982632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuczynski AM, Kanter JW, Robinaugh DJ. Differential associations between interpersonal variables and quality-of-life in a sample of college students. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:127–39. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02298-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dao-Tran TH, Lam LT, Balasooriya NN, Comans T. The Medical Outcome Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS): A psychometric systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79:4521–41. doi: 10.1111/jan.15786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dafaalla M, Farah A, Bashir S, Khalil A, Abdulhamid R, Mokhtar M, et al. Validity and reliability of Arabic MOS social support survey. Springerplus. 2016;5:1306. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2960-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alaloul F, Hall LA, AbuRuz ME, Abusalem S. Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the medical outcomes study social support survey in cancer survivors post-HSCT. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2021;24:235–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden L, Lee C, Hockey R, Ware RS, Dobson AJ. Validation of the MOS Social Support Survey 6-item (MOS-SSS-6) measure with two large population-based samples of Australian women. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2849–53. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gjesfjeld CD, Greeno CG, Kim KH. A confirmatory factor analysis of an abbreviated social support instrument: The MOS-SSS. Res Soc Work Pract. 2008;18:231–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gómez-Campelo P, Pérez-Moreno EM, de Burgos-Lunar C, Bragado-Álvarez C, Jiménez-García R, Salinero-Fort MÁ, et al. Psychometric properties of the eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey based on Spanish outpatients. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2073–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, Ganz PA, Clough-Gorr KM. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: Psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:1107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priede A, Andreu Y, Martínez P, Conchado A, Ruiz-Torres M, González-Blanch C. The factor structure of the Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey: A comparison of different models in a sample of recently diagnosed cancer patients. J Psychosom Res. 2018;108:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djukanovic I, Carlsson J, Årestedt K. Is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) a valid measure in a general population 65-80 years old? A psychometric evaluation study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:193. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0759-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – A review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:17–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl AA. Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: Factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:540–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terkawi AS, Tsang S, AlKahtani GJ, Al-Mousa SH, Al Musaed S, AlZoraigi US, et al. Development and validation of Arabic version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:S11–8. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_43_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt S, Mühlan H, Power M. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: Psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:420–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The WHOQOL Group Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalky HF, Meininger JC, Al-Ali NM. The reliability and validity of the Arabic World Health Organization quality of life-BREF instrument among family caregivers of relatives with psychiatric illnesses in Jordan. J Nurs Res. 2017;25:224–30. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohaeri JU, Awadalla AW. The reliability and validity of the short version of the WHO quality of life instrument in an Arab general population. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:98–104. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nawel H, Elisabeth S. Bulletin of the European Health Psychology Society. Limassol: European Health Psychologist; 2015. Adaptation and validation of the Tunisian version of the brief COPE scale; p. 783. Available from: https://www.ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/view/1253 . [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 09] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field A. 4th. London: Sage; 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘N’ Roll. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald RP. New York: Psychology Press; 1999. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferguson E, Cox T. Exploratory factor analysis: A users’ guide. Int J Sel Assess. 1993;1:84–94. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. 5th. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in structural equation models. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1993. pp. 163–80. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. Social Support: An Interactional View. Oxford, England: John Wiley and Sons; 1990. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching; pp. 319–66. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lakey B, Orehek E. Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol Rev. 2011;118:482–95. doi: 10.1037/a0023477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holt-Lunstad J. Social connection as a public health issue: The evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the “social” in social determinants of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-110732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.