Abstract

Pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) is an ornamental-medicinal plant commonly planted in green spaces, and it has various industrial and medicinal applications. It is widely cultivated in semi-arid and Mediterranean regions, where it often faces drought stress. This research was conducted to evaluate the impact of moderate and severe drought stress during the flowering stage and to determine the drought response mechanisms in pot marigold. Therefore, the pot marigold plants were treated with control (100%), 60% and 30% of field capacity (FC) in the greenhouse, starting from the blooming stage, when usually the decrease in rainfall occurs during its life cycle. The impacts of different levels of stress were evaluated on eight plant water content parameters, seventeen morpho-physiological and phenological traits, and nine biochemical factors. Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) by best linear unbiased estimates (BLUEs) indicated that reducing water supply at moderate stress still led to satisfactory growth of pot marigold, where most of the morpho-physiological and phenological traits, including days from budding to flowering and pollination, flowers number, flower weight and diameter, and plant height, were not significantly affected at 60% of FC in comparison to 100% of FC. However, severe drought stress significantly reduced plant height, flower diameter, and flower weight by 31%, 20%, and 38%, respectively. In addition, the factor analysis demonstrated that pot marigold employs a combination of avoidance and tolerance mechanisms, including root system elongation, adjustment in antioxidant enzymes activity, and chlorophyll and carotenoid content to cope with drought stress. Our results represent a significant advance in understanding the level of tolerance and the responsive mechanisms to drought stress in pot marigold during the most critical stage of its life cycle, when reduced rainfall usually occurs in its cultivation area.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-15845-5.

Keywords: Canonical correlation, Root system, Oxidative enzymes

Subject terms: Plant breeding, Plant stress responses

Introduction

Pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) is an ornamental medicinal plant native to Europe, Western Asia, and America1. In addition, pot marigold has various medical, cosmetic and industrial applications. It is widely used in cosmetic formulations of creams, lotions, and hair care products. The main medicinal applications of pot marigold include the treatment of skin irritations, rashes, acne, lesions, wounds, and inflammations. Furthermore, its extract exhibits antifungal, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties, as well as anti-inflammatory effects2,3. The extracts of pot marigold’s flower have diverse industrial applications in food coloring, pharmaceuticals, and as additives in poultry feed for enhancing coloration and emulsifying properties4,5. In addition to edible uses (flavoring and coloring of various foods), the flower of this plant has effective substances that are used in the preparation of painting colors and industrial nylon6–8. Its products also have phytoremediation, allelopathic effects, and they are used as a trap crop against plant parasitic nematodes.

Flowering is a delicate phase of growth in Calendula officinalis during which plants are highly susceptible to environmental stress such as drought. Environmental stress during this phase affects plant growth and flower morphogenesis significantly, as well as the process of pigmentation and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites that are crucial for ornamental as well as medicinal applications of the crop9,10. Although commercial harvest is usually done at the onset of flowering, information on physiological and biochemical reactions in response to flowering is important in determining how drought stress can influence yield quality and postharvest traits. Therefore, research on drought effects at this level can be useful in formulating future strategies on improving tolerance to stress as well as commercial quality in pot marigold.

Pot marigold is frequently cultivated in Mediterranean and semi-arid regions, where it often faces drought conditions. Drought stress is one of the most significant challenges to produce gardens and green spaces that destroys photosynthetic pigments, reduces leaf chlorophyll, and damages photosynthetic structures11,12. Plants adopt three main mechanisms including avoidance, tolerance or escape in response to drought stress. Escape refers to plants’ capacity to expedite the flowering or life cycle, while drought avoidance denotes plants’ capability to minimize water loss and enhance water uptake by altering the morphology of the root system. They may increase root biomass and length and reduce shoot growth to avoid water limitations13,14. Drought tolerance, on the other hand, pertains to plants’ ability to adapt to drought conditions through modifications in physiological and biochemical processes. Under drought stress conditions, electrolyte leakage and malondialdehyde (MDA) content may increase. This is because membrane lipid peroxidation produces MDA in response to elevated intercellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under oxidative stresses15. However, peroxidase (POD) activity reduces under stress conditions suggesting the capability of enzymatic mechanisms in removing ROS in plants16. Despite the general harmful effects of drought stress on crops, medicinal plants may be more economically efficient in stress conditions by producing more potent compounds, in contrast to crops whose performance is negatively impacted by such conditions17.

Best Linear Unbiased Estimates (BLUEs)18 are significant because they allow us to combine different measurements of the same observable, taking into consideration their independent uncertainties and correlation. BLUEs are unbiased and have the least variance when the true uncertainties are known. But bias might creep in if estimated uncertainties were used. These biases can be mitigated using the BLUE method iteratively, which improves the precision of the combined measurements in the statistical method19.

Given the significance of pot marigold and its widespread cultivation in semi-arid regions, several research studies have been conducted to assess the impact of drought stress on this species during the early growth stages and to study the interaction of drought with other factors like nitrogen levels in Calendula officinalis L20. Some of these studies have focused on the use of drought stress modifiers to mitigate the effects of drought21. Additionally, some research have been carried out on the application of various solvents and phytohormones to enhance drought tolerance in pot marigold22,23. However, the impact of different levels of drought stress during flowering stage on the most economical criteria of Calendula officinalis L. and its physiological response mechanism to drought stress remained unclear. In this study, we evaluated the effects of moderate and severe drought stress, starting from the blooming stage coinciding with the usual reduced rainfall patterns observed in Mediterranean climates, on the most important morpho-physiological, phenological, and biochemical traits, and identified the dominant drought response mechanism in pot marigold.

Materials and methods

Plant materials, growth conditions and experimental design

The marigold seeds from Atlas Sabz company were planted in a sowing tray containing equal parts of cocopeat, perlite, and peat moss and then the seedlings were transferred to pots in a greenhouse with natural light. The experiment was conducted in a controlled greenhouse with day/night temperatures of 25 ± 2 °C / 20 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 65–75%. Each pot contained 3.0 kg of soil consisting of equal parts of field soil, perlite, and humus. The soil analysis demonstrated in Table 1. In order to impose drought stress on the pot experiment, the pots were first well-watered such that the excess water flowed from the bottom, leaving the soil saturated. The pots were weighed for each and then the weight utilized to calculate the amount of water necessary to impose a desired level of drought stress in terms of percentage of field capacity. Water was added appropriately to provide the desired level of soil moisture for the duration of the treatment. The gravimetric approach enabled control over the water content of the soil to impose drought stress24. The pots were irrigated to field capacity (FC) until the blooming stage when the buds of flowers start to appear. In the budding stage of growth, plants subjected to three levels of irrigation including 100% field capacity (control), 60% FC and 30% FC. The pots were watered daily and weighed to maintain desirable FC. The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design (CRD) with five replicates.

Table 1.

Concentration of macronutrient and micronutrient elements of the soil used in this experiment.

| Element | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | ||

| Calcium (Mgk− 1) | Ca | 4511 |

| Phosphorus (Mgk− 1) | P | 34.59 |

| Potassium (Mgk− 1) | K | 1140 |

| Nitrogen (%) | N | 0.23 |

| Micronutrients | ||

| Manganese (Mgk− 1) | Mn | 21.83 |

| Zinc (Mgk− 1) | Zn | 2.69 |

| Iron (Mgk− 1) | Fe | 5.70 |

| Boron (ppm) | B | 0.36 |

| pH | - | 7.20 |

The concentrations of elements are in mg/kg, parts per million (ppm), and Percent (%).

Plant water content

Leaf samples were collected 45 days after the drought stress treatment was applied to measure plant water content and their biochemical and antioxidant enzyme activity. The measured parameters included relative water content (RWC), water saturation deficit (WSD), initial water content (IWC), leaf water content (LWC), excised leaf water retention (ELWR), excised leaf water loss (ELWL), leaf water loss (LWL) and relative water protective (RWP) as follows,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where, FrW stands for fresh weight, DW stands for dry weight (which is measured by placing the leaves in an oven at 80 °C for 48 h), and TW stands for turgid weight after soaking the leaves in distilled water for 18–20 h in the dark. W1, W2, and W3, refer to weight of leaves placed in an incubator at a temperature of 25 °C after two, four, and six hours respectively.

Biochemical and antioxidant traits

To analyze biochemical and antioxidants, the fresh leaves were grounded into a fine powder using liquid nitrogen in a porcelain mortar. The powdered leaves were then placed into a tube and stored in a freezer at - 80 °C until they were ready to be measured. Superoxide dismutase (SOD)30, Catalase (CAT)31, POD32, Ascorbate peroxidase (APX)33, MDA34, and different pigments such as Chlorophyll a (Ca), Chlorophyll b (Cb), total Chlorophyll (TC) and Carotenoids (Car)35 were evaluated as followings:

|

where, ODControl and ODSample are the light absorption values of the control solution and the examined sample at a wavelength of 560 nm, respectively, and LW is the weight of the leaf sample in grams (g).

|

|

where t1 and t2 are the beginning and end of the investigated period, respectively. A240(t1) and A240 (t2) are the values of light absorption at the wavelength of 240 nm at times t1 and t2, respectively. E is the H2O2 decomposition coefficient (39.4 for CAT, 26.6 for POD, and 2.8 for APX) and LW is the weight of the leaf sample. Ca = (12.25 A663 – 2.79 A646); Cb = (21.21 A646 – 5.1 A663); TC = Ca + Cb; Car = (1000 A470 – 1.8 Ca – 85.02 Cb)/198.

Morpho-physiological traits

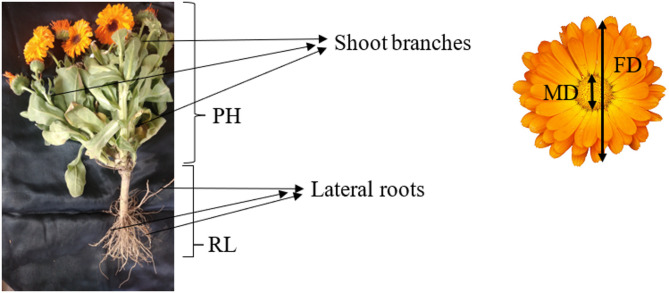

Various growth and developmental related traits including both phenological and morphological criteria were evaluated. Days from budding to flowering when flower fully expanded (DB) and days from budding to pollination when over 60% of pollen were visible (DP) were measured as phenological traits. Moreover, plant height (PH), number of shoot branches (BN), whole flower diameter (FD) and middle flower diameter (MD), flower weight (FW), number of leaves (LN), canopy temperature (CT) measurement by infrared thermometer, number of flowers (FN), number of flowers to branches ratio (FB), shoot weight (SW), root weight (RW), number of lateral roots (RN), root volume (RV), ratio of shoot to root weight (SR), and root length (RL) were evaluated (Fig. 1). Additionally, root volume (RV) was determined by calculating the amount of water displaced when the roots were submerged in a graduated cylinder filled with water. These traits were measured 45 days following the imposition of drought stress treatment.

Fig. 1.

The overview of pot marigold and the evaluated morphological traits used in this study. RL: root length, PH: plant height, FD: flower diameter, MD: middle flower diameter.

Data analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least square difference (LSD) test were performed using SAS 9.4 software. Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML)36 by Best Linear Unbiased Estimates (BLUEs) was conducted via GenStat software (ver. 15)37. According to Henderson (1975)16, the ordinary least squares estimator of the coefficients of a linear regression model can be the best estimator, known as the BLUE. This is a statistical method for maximum likelihood estimation that uses a transformed set of data to calculate a likelihood function, thus avoiding the impact of nuisance parameters38,39. Principal component analysis (PCA), canonical correlation analysis (CCA), and Pearson correlation were conducted using R program (version 4.4.1).

Results

Pot marigold water content under moderate and severe drought stress

The application of different levels of drought stress had significant effects on water status related traits (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of variance for water related traits in response to drought stress in pot marigold.

| Sources of variation |

df | Mean squares | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RWC | WSD | IWC | LWC | ELWR | ELWL | LWL | RWP | ||

|

Irrigation treatment |

2 | 188.6*** | 0.02*** | 5.4** | 0.001** | 0.003*** | 0.003** | 0.002*** | 0.003** |

| Error | 12 | 8.5 | 0.001 | 0.6 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| CV (%) | 3.3 | 22.5 | 8.8 | 1 | 1.5 | 11.4 | 13.3 | 1.9 | |

ns, *, ** and ***: non-significant and significant at the probability level of 5%, 1% and 0.1%, respectively. df: degree of freedom, RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, and RWP: Relative water protective.

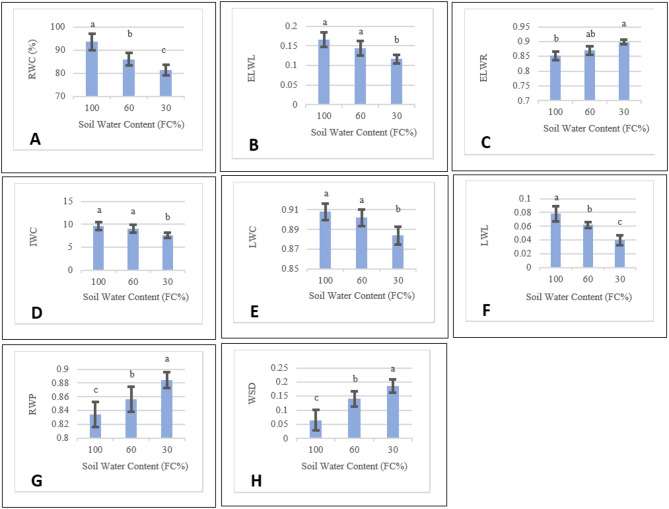

While RWC and LWL significantly reduced, RWP, ELWR and WSD elevated under both medium and severe stresses (Fig. 2A, F, G, C, H). However, LWC, IWC and ELWL significantly decreased only under severe stress (Fig. 2E, D, B). Conversely, ELWR increased under moderate and severe stress (Fig. 2C). However, there was no significant difference between normal conditions and moderate stress.

Fig. 2.

The best linear unbiased estimates (BLUE) of marigold water related content traits under 100%, 60% and 30% of FC. Similar letters mean no significant difference (LSD = 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error (n = 5). RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, and RWP: Relative water protective.

Effects of moderate and severe drought stress on morpho-physiological and phenological traits

To evaluate the overall impact of drought stress on pot marigold, seventeen morpho-physiological and phenological traits related to yield and growth were evaluated (Table 3; Fig. 3). The results showed that the number of flowers, shoot branches, leaves, flowers/branches ratio, and number of lateral roots were not significantly affected by drought stress (Table 3; Fig. 3). Additionally, the phenological traits of days to flowering and pollination were not influenced by drought stress (Table 3; Fig. 3). However, plant height, flower diameter, mid-flower diameter, and flower weight were not significantly altered by moderate drought stress, but they were significantly reduced by 31%, 20%, 25% and 38%, respectively, under severe stress conditions.

Table 3.

ANOVA on morpho-physiological and phenological traits in response to drought stress in pot marigold.

| Source of variation |

df | Mean squares | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | RW | DB | DP | PH | BN | FN | FD | MD | ||

|

Irrigation treatment |

2 | 6.4*** | 147** | 54ns | 29.3ns | 200ns | 6.1ns | 2.6ns | 1.7ns | 0.3ns |

| Error | 12 | 0.3 | 18.9 | 119 | 151 | 57.9 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.08 |

| CV (%) | 2.1 | 38.4 | 32.8 | 29.3 | 22.4 | 38 | 29 | 12.4 | 15.3 | |

| S.V. | df | Mean squares | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN | FW | SW | RL | SR | RN | RV | FB | ||

| Irrigation treatment | 2 | 119ns | 6.2ns | 1050*** | 18.8ns | 0.92*** | 28.1ns | 1040*** | 150.5ns |

| Error | 12 | 53.1 | 2.4 | 61.3 | 4.3 | 0.05 | 73.1 | 67.3 | 527.3 |

| CV (%) | 19.5 | 27.6 | 36.7 | 16.1 | 13.1 | 22.7 | 28.8 | 30.1 | |

ns, *, ** and ***: non-significant and significant at the probability level of 5%, 1% and 0.1%, respectively. DB: Days from budding to flowering, DP: Days from budding to pollination, PH: Plant height, BN: number of shoot branches, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, LN: number of leaves, CT: Canopy temperature, FN: number of flowers, FB: flower to branch ratio, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RN: number of lateral roots, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

Fig. 3.

The best linear unbiased estimates (BLUE) of morpho-physiological and phenological traits under 100%, 60% and 30% of FC. Similar letters mean no significant difference (LSD = 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error (n = 5). DB: Days from budding to flowering, DP: Days from budding to pollination, PH: Plant height, BN: number of shoot branches, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, LN: number of leaves, CT: Canopy temperature, FN: number of flowers, FB: flower to branch ratio, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RN: number of lateral roots, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

In our study, drought stress resulted in a significant decrease in shoot weight (51.9% and 76.3%), root volume (43.7% and 63.6%), root weight (35.7% and 63.8%), and shoot/root ratio (29.1 and 35.9%) under moderate and severe stress, respectively (Fig. 3H, P, M, and Q). Conversely, root length showed an increase (12.8% and 21.6%) under moderate and severe stress, respectively (Fig. 3O). Similarly, canopy temperature showed a significant increase (4.9% and 8.5%) in response to moderate and severe drought stress (Fig. 3C).

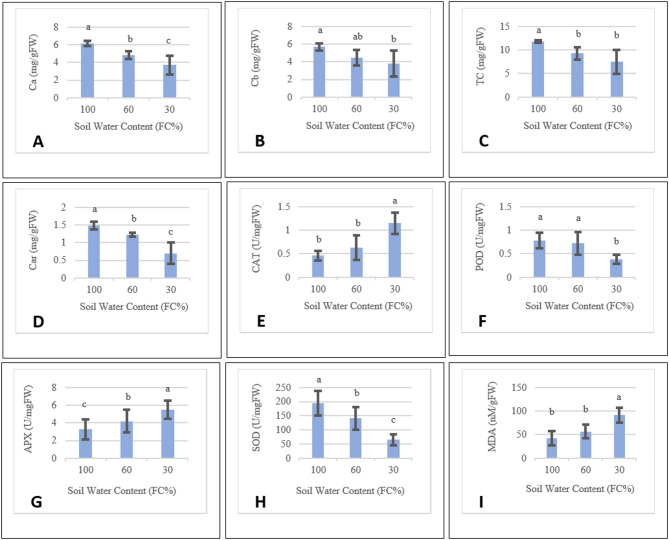

Chlorophyll content and oxidative enzymes activity under moderate and severe drought stress

Considering the effects of drought stress on biochemistry of plants and alteration of oxidative related enzymes, chlorophyll content and the activity of various enzymes were evaluated under stress and compared to normal irrigation conditions (Table 4; Fig. 4). Drought stress affected the activities of oxidative-related enzymes in pot marigold, as evidenced by alteration of APX, CAT, MDA, SOD, and POD levels. Specifically, APX increased in response to both levels of drought stress, while CAT and MDA levels were elevated only in severe drought stress treatment. Conversely, SOD level significantly decreased as drought stress severity increased, and POD declined only under severe stress conditions (Table 4; Fig. 4H, and F). When subjected to drought stress conditions, there was a notable reduction in the levels of carotenoids and Chlorophyll a (Table 4; Fig. 4D, and A). Chlorophyll b levels decreased only in cases of severe stress, whereas total chlorophyll decreased with moderate stress and remained steady under severe stress in pot marigold (Table 4; Fig. 4B, and C).

Table 4.

ANOVA on biochemical traits in response to drought stress in marigold.

| Sources of variation |

df | Mean squares | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POD | SOD | MDA | CAT | Car | Ca | Cb | TC | APX | ||

|

Irrigation treatment |

2 | 0.27** | 20926.1*** | 3245.9*** | 0.65*** | 0.81*** | 7.5*** | 4.6* | 23.8** | 6.04* |

| Error | 12 | 0.03 | 1292.4 | 225 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| CV (%) | 28.8 | 27 | 23.6 | 27.8 | 16.5 | 14.3 | 21.7 | 17.3 | 26.6 | |

ns, *, ** and ***: non-significant and significant at the probability level of 5%, 1% and 0.1%, respectively. MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total Chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase.

Fig. 4.

The BLUE of biochemical traits under 100%, 60% and 30% of FC. Similar letters mean no significant difference (LSD = 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error (n = 5). (MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total Chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase).

All traits that were not significantly altered by drought stress based on ANOVA and LSD analysis (Table 3; Fig. 3), including RN, LN, FN, FB, DP, DB, and BN, were excluded from further analysis.

The pearson correlation between morpho-physiological and biochemical traits

The pot marigold shoot architecture showed significant correlation with plant water content at different levels of drought stress, chlorophyll content, oxidative enzymes activities and root weight (Table 5). Flower weight and plant height exhibited a notable positive correlation with relative water content and POD activity. However, they displayed a negative correlation with WSD under severe stress conditions (Table 5). Additionally, plant height demonstrated a positive correlation with root weight, total chlorophyll, as well as chlorophyll a and b content. On the other hand, flower weight and flower diameter were negatively correlated with shoot/root ratio and APX activity, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pearson correlation coefficients among evaluated traits under 60% and 30% of field capacity (FC).

| 60% of FC | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW | PH | FD | MD | SW | RW | SR | RV | RL | CT | RWC | WSD | IWC | LWC | ||

| 30% of FC | FW | 1 | 0.12ns | -0.39ns | -0.59ns | 0.68ns | 0.70ns | 0.42ns | 0.74ns | 0.73ns | 0.54ns | 0.86ns | -0.86ns | -0.27ns | -0.49ns |

| PH | 0.99*** | 1 | -0.78ns | -0.58ns | 0.73ns | 0.63ns | 0.91ns | 0.57ns | -0.01ns | -0.07ns | -0.40ns | 0.4ns | -0.73ns | -0.68ns | |

| FD | 0.51ns | 0.49ns | 1 | 0.46ns | -0.57ns | -0.45ns | -0.94* | -0.40ns | 0.07ns | 0.34ns | 0.07ns | -0.01ns | 0.94ns | 0.85ns | |

| MD | 0.25ns | 0.27ns | 0.14ns | 1 | -0.76ns | -0.72ns | -0.69ns | -0.71ns | -0.76ns | -0.56ns | -0.24ns | 0.24ns | 0.18ns | 0.22ns | |

| SW | 0.77ns | 0.84ns | 0.35ns | 0.31ns | 1 | 0.99** | 0.76ns | 0.97** | 0.56ns | 0.52ns | 0.28ns | -0.24ns | -0.48ns | -0.67ns | |

| RW | 0.87ns | 0.91* | 0.26ns | 0.49ns | 0.92* | 1 | 0.64ns | 1*** | 0.61ns | 0.62ns | 0.36ns | -0.30ns | -0.37ns | -0.06ns | |

| SR | -0.30ns | -0.24ns | 0.26ns | -0.49ns | 0.13ns | -0.26ns | 1 | 0.60ns | 0.14ns | -0.08ns | -0.10ns | 0.06ns | -0.83ns | -0.78ns | |

| RV | 0.56ns | 0.50ns | 0.20ns | -0.53ns | 0.08ns | 0.17ns | -0.23ns | 1 | 0.65ns | 0.67ns | 0.42ns | -0.36ns | -0.32ns | -0.57ns | |

| RL | 0.17ns | 0.10ns | -0.18ns | -0.77ns | -0.22ns | -0.17ns | -0.14ns | 0.89* | 1 | 0.90* | 0.69ns | 0.66ns | 0.31ns | 0.11ns | |

| CT | -0.47ns | -0.40ns | -0.76ns | -0.40ns | -0.01ns | -0.17ns | 0.38ns | -0.26ns | 0.10ns | 1 | 0.58ns | -0.49ns | 0.48ns | 0.20ns | |

| RWC | 0.95* | 0.97** | 0.63ns | 0.34ns | 0.88* | 0.90* | -0.10ns | 0.35ns | -0.07ns | -0.45ns | 1 | -0.99** | 0.15ns | -0.10ns | |

| WSD | -0.94* | -0.97** | -0.52ns | -0.36ns | -0.94* | -0.94* | 0.08ns | -0.30ns | 0.11ns | 0.32ns | -0.99** | 1 | -0.10ns | 0.11ns | |

| IWC | 0.30ns | 0.22ns | 0.51ns | 0.29ns | -0.27ns | -0.03ns | -0.57ns | 0.35ns | 0.09ns | -0.93* | 0.20ns | -0.07ns | 1 | 0.93* | |

| LWC | 0.18ns | 0.11ns | 0.59ns | 0.41ns | -0.28ns | -0.09ns | -0.44ns | 0.11ns | -0.15ns | -0.95* | 0.15ns | -0.02ns | 0.96** | 1 | |

| ELWR | -0.01ns | 0.03ns | 0.36ns | 0.87ns | 0.17ns | 0.21ns | -0.08ns | -0.72ns | -0.94* | -0.43ns | 0.19ns | -0.18ns | 0.25ns | 0.47ns | |

| ELWL | -0.14ns | -0.13ns | -0.66ns | -0.72ns | -0.06ns | -0.12ns | 0.13ns | 0.40ns | 0.70 ns | 0.77ns | -0.29ns | 0.21ns | -0.61ns | -0.78ns | |

| LWL | -0.22ns | -0.25ns | -0.43ns | 0.64ns | -0.40ns | -0.08ns | -0.80ns | -0.35ns | 0.30ns | -0.19ns | -0.31ns | 0.31ns | 0.38ns | 0.39ns | |

| RWP | 0.14ns | 0.13ns | 0.66ns | 0.72ns | 0.06ns | 0.13ns | -0.13ns | -0.40ns | -0.70 ns | -0.77ns | 0.29ns | -0.21ns | 0.61ns | 0.78ns | |

| Ca | 0.85ns | 0.90* | 0.37ns | 0.57ns | 0.93* | 0.98** | -0.19ns | 0.07ns | -0.30ns | -0.26ns | 0.92* | -0.96* | 0.02ns | 0.01ns | |

| Cb | 0.87ns | 0.92* | 0.33ns | 0.34ns | 0.98** | 0.98** | -0.06ns | 0.22ns | -0.11ns | -0.11ns | 0.92* | -0.97** | -0.13ns | -0.18ns | |

| TC | 0.87ns | 0.92* | 0.35ns | 0.44ns | 0.97** | 0.99** | -0.12ns | 0.16ns | -0.19ns | -0.17ns | 0.93* | -0.97** | -0.07ns | -0.11ns | |

| Car | 0.71ns | 0.74ns | 0.26ns | -0.37ns | 0.74ns | 0.62ns | 0.26ns | 0.62ns | 0.45ns | 0.13ns | 0.69ns | -0.72ns | -0.28ns | -0.42ns | |

| CAT | -0.31ns | -0.28ns | -0.47ns | 0.77ns | -0.16ns | 0.04ns | -0.51ns | -0.71ns | -0.64ns | 0.08ns | -0.28ns | 0.22ns | 0.01ns | 0.10ns | |

| POD | 0.89* | 0.90* | 0.07ns | 0.17ns | 0.76ns | 0.89* | -0.39ns | 0.54ns | 0.29ns | -0.09ns | 0.79ns | -0.83ns | 0.01ns | -0.16ns | |

| APX | -0.24ns | -0.15ns | 0.21ns | 0.30ns | 0.34ns | 0.07ns | 0.67ns | -0.79ns | -0.81ns | 0.23ns | 0.05ns | -0.10ns | -0.50ns | -0.26ns | |

| MDA | -0.35ns | -0.34ns | 0.03ns | 0.79ns | -0.21ns | -0.12ns | -0.20ns | 0.82ns | -0.86ns | -0.27ns | -0.22ns | 0.22ns | 0.23ns | 0.44ns | |

| SOD | -0.42ns | -0.43ns | -0.67ns | -0.83ns | -0.38ns | -0.46ns | 0.21ns | 0.31ns | 0.70ns | 0.74ns | -0.56ns | 0.51ns | 0.53ns | -0.66ns | |

| 60% of FC | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELWR | ELWL | LWL | RWP | Ca | Cb | TC | Car | CAT | POD | APX | MDA | SOD | ||

| 30% of FC | FW | 0.62ns | -0.49ns | -0.01ns | 0.49ns | 0.06ns | -0.07ns | -0.02ns | 0.44ns | 0.51ns | -0.02ns | -0.97** | -0.77ns | 0.45ns |

| PH | 0.25ns | -0.09ns | -0.35ns | 0.09ns | 0.10ns | 0.20ns | 0.16ns | -0.41ns | 0.38ns | -0.69ns | -0.14ns | -0.69ns | 0.55ns | |

| FD | 0ns | -0.20ns | 0.09ns | 0.20ns | -0.21ns | -0.26ns | -0.25ns | -0.15ns | -0.84ns | 0.14ns | 0.30ns | 0.70ns | -0.58ns | |

| MD | -0.83ns | 0.75ns | -0.24ns | -0.75ns | -0.58ns | -0.54ns | -0.56ns | -0.14ns | -0.45ns | 0.44ns | 0.72ns | 0.67ns | -0.07ns | |

| SW | 0.73ns | -0.56ns | -0.42ns | 0.56ns | -0.07ns | -0.08ns | -0.07ns | -0.23ns | 0.29ns | -0.70ns | -0.71ns | -0.96** | 0.68ns | |

| RW | 0.78ns | -0.62ns | -0.47ns | 0.62ns | -0.15ns | 0.18ns | -0.17ns | -0.27ns | 0.18ns | -0.72ns | -0.74ns | -0.94* | 0.67ns | |

| SR | 0.29ns | -0.10ns | -0.13ns | 0.01ns | 0.26ns | 0.31ns | 0.30ns | -0.02ns | 0.71ns | -0.42ns | -0.40ns | -0.80ns | 0.56ns | |

| RV | 0.80ns | -0.65ns | -0.46ns | 0.65ns | -0.16ns | -0.21ns | -0.19ns | -0.24ns | 0.15ns | -0.69ns | -0.77ns | -0.92* | 0.65ns | |

| RL | 0.93* | -0.93* | 0.25ns | 0.93* | 0.34ns | 0.21ns | 0.26ns | 0.28ns | 0.10ns | -0.22ns | -0.87ns | -0.46ns | -0.08ns | |

| CT | 0.92* | -0.94* | -0.07ns | 0.94* | 0.01ns | -0.10ns | -0.07ns | -0.09ns | -0.31ns | -0.45ns | -0.69ns | -0.37ns | -0.01ns | |

| RWC | 0.46ns | -0.42ns | 0.12ns | 0.42ns | -0.05ns | -0.21ns | -0.16ns | 0.56ns | 0.22ns | 0.28ns | -0.82ns | -0.37ns | 0.16ns | |

| WSD | -0.40ns | 0.36ns | -0.21ns | -0.36ns | -0.04ns | 0.13ns | 0.07ns | -0.66ns | -0.33ns | -0.38ns | 0.82ns | 0.34ns | -0.12ns | |

| IWC | 0.21ns | -0.42ns | 0.33ns | 0.42ns | 0.10ns | 0.02ns | 0.05ns | 0.01ns | -0.69ns | 0.14ns | 0.12ns | 0.64ns | -0.74ns | |

| LWC | 0ns | -0.23ns | 0.5ns | 0.23ns | 0.31ns | 0.27ns | 0.29ns | 0.10ns | -0.56ns | 0.27ns | 0.33ns | 0.81ns | -0.92* | |

| ELWR | 1 | -0.98** | 0ns | 0.97** | 0.22ns | 0.14ns | 0.17ns | -0.06ns | -0.03ns | -0.56ns | -0.78ns | -0.58ns | 0.07ns | |

| ELWL | -0.89* | 1 | -0.12ns | -1*** | -0.29ns | -0.20ns | -0.23ns | 0.04ns | 0.16ns | 0.48ns | 0.68ns | 0.38ns | 0.14ns | |

| LWL | 0.42ns | -0.31ns | 1 | 0.12ns | 0.89* | 0.84ns | 0.86ns | 0.78ns | 0.39ns | 0.63ns | -0.09ns | 0.41ns | -0.80ns | |

| RWP | 0.89* | -1*** | 0.31ns | 1 | 0.29ns | 0.20ns | 0.23ns | -0.04ns | -0.16ns | -0.48ns | -0.68ns | -0.38ns | -0.14ns | |

| Ca | 0.35ns | 0.28ns | -0.08ns | 0.28ns | 1 | 0.98** | 0.99*** | 0.59ns | 0.52ns | 0.27ns | -0.19ns | 0.11ns | -0.63ns | |

| Cb | 0.11ns | -0.05ns | -0.29ns | 0.05ns | 0.96** | 1 | 1*** | 0.48ns | 0.51ns | 0.20ns | -0.06ns | 0.13ns | -0.61ns | |

| TC | 0.22ns | -0.15ns | -0.20ns | 0.15ns | 0.98** | 0.99*** | 1 | 0.52ns | 0.52ns | 0.23ns | -0.11ns | 0.12ns | -0.62ns | |

| Car | -0.50ns | 0.43ns | -0.74ns | -0.43ns | 0.55ns | 0.75ns | 0.67ns | 1 | 0.66ns | 0.82ns | -0.40ns | 0.09ns | -0.35ns | |

| CAT | 0.62ns | -0.32ns | 0.88ns | 0.33ns | 0.06ns | -0.14ns | -0.05ns | -0.70ns | 1 | 0.33ns | -0.43ns | -0.46ns | 0.21ns | |

| POD | -0.22ns | 0.22ns | -0.11ns | -0.22ns | 0.80ns | 0.87ns | 0.85ns | 0.75ns | -0.16ns | 1 | 0.12ns | 0.53ns | -0.44ns | |

| APX | 0.61ns | -0.36ns | -0.25ns | 0.36ns | 0.20ns | 0.15ns | 0.17ns | -0.10ns | 0.20ns | -0.34ns | 1 | 0.74ns | -0.30ns | |

| MDA | 0.90* | -0.75ns | 0.67ns | 0.75ns | -0.01ns | -0.25ns | -0.15ns | -0.81ns | 0.81ns | -0.47ns | 0.47ns | 1 | -0.78ns | |

| SOD | -0.88* | 0.93* | -0.26ns | -0.93* | -0.59ns | -0.38ns | -0.48ns | 0.18ns | -0.32ns | -0.11ns | -0.36ns | -0.64ns | 1 | |

Significant values are in [bold].

ns, *, ** and ***: non-significant and significant at the probability level of 5%, 1% and 0.1%, respectively. MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase, RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, RWP: Relative water protective, PH: Plant height, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, FW: Flower weight, CT: Canopy temperature, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

Root growth was mainly correlated with plant water and chlorophyll content, canopy temperature and activities of some of the antioxidant enzymes (Table 5). Root weight and root volume displayed a strong positive correlation with each other and with shoot weight (Table 5). Moreover, root volume exhibited a relatively high positive correlation with root length. Root weight showed a significant positive correlation with relative water content, total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b content. Similarly, total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b exhibited strong positive associations with root and shoot weight under drought conditions in Tagetes spp., and tomato40,41. Furthermore, root weight exhibited a positive correlation with POD activity while showing a negative correlation with MDA activity and water saturation deficit (Table 5). Root length was positively correlated with RWP, ELWR, and canopy temperature, but displayed a negative correlation with ELWL (Table 5).

Canonical correlation analysis

Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) helps to identify and measure the associations between two sets of variables. After excluding non-significant and non-correlated traits based on initial Pearson correlation analysis, 14 traits from two groups of morpho-physiological (U) and biochemical (V) traits were selected for analysis of canonical correlations between groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

Standardized canonical variables and their correlation with Morpho-physiological and biochemical traits in pot marigold under drought stress.

| Variable | Coefficients in canonical variables |

Correlation with morpho-physiological variables |

Correlation with biochemical variables |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morpho-physiological traits |

Morph1 (U1) |

Morph2 (U2) |

Morph1 (U1) |

Morph2 (U2) |

Bioch1 (V1) |

Bioch2 (V2) |

| FW | -0.29 | 1.15 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.39 |

| PH | 0.60 | -1.59 | 0.73 | -0.05 | 0.72 | -0.05 |

| RL | -0.56 | 0.10 | -0.83 | -0.15 | -0.83 | -0.14 |

| RWC | 0.31 | -0.21 | 0.82 | 0.33 | 0.81 | 0.31 |

| SW | 0.23 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 0.31 | 0.76 | 0.29 |

| RW | -0.09 | -0.20 | 0.72 | 0.18 | 0.721 | 0.17 |

| CT | 0.18 | -0.79 | -0.74 | -0.49 | -0.74 | -0.46 |

|

Correlation of canonical variables |

0.99 (U1,V1) |

0.98 (U2,V2) |

||||

|

Canonical correlation modified |

0.94 (U1,V1) |

0.89 (U2,V2) |

||||

| Variable | Coefficients in canonical variables | Correlation with biochemical variables |

Correlation with morpho-physiological variables |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical traits |

Bioch1 (V1) |

Bioch2 (V2) |

Bioch1 (V1) |

Bioch2 (V2) |

Morph1 (U1) |

Morph2 (U2) |

| Chlorophyll a | 2.11 | -1.05 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.85 | 0.25 |

| Chlorophyll b | -1.05 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.65 | 0.23 |

| CAT | 0.24 | -0.56 | -0.52 | -0.44 | -0.52 | -0.42 |

| POD | -0.30 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.52 |

| APX | 0.62 | -1.16 | -0.36 | -0.40 | -0.36 | -0.37 |

| MDA | -0.33 | 2.21 | -0.61 | -0.22 | -0.06 | -0.21 |

| SOD | 0.28 | 1.26 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.44 |

Significant values are in [bold].

FW: Flower weight, PH: Plant height, RL: Root Length, RWC: Relative water content, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, CT: Canopy temperature, CAT: Catalase, POD: Peroxidase, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, MDA: Malondialdehyde, SOD: Superoxide dismutase.

Results showed that the correlation of the first pair of canonical variables was relatively high, and the second pair had a lower correlation. Hence, the first pair of canonical variates was a better predictor of the opposite set of variables. The highest coefficients in the first canonical (Morph1) variate for Morpho-physiological traits were related to PH and RL. In Morph2, PH had the highest coefficient. In Bioch1 and Bioch2, Ca and MDA, had the highest coefficients, respectively. Morph1 had relatively strong correlations with RL and RWC. Morph2 was strongly correlated with CT and FW. The results indicated that CT and FW are the most effective traits among morpho-physiological traits when drought occurs. Bioch1(V1) had a positive correlation with Ca and Cb. Bioch2 (V2) had high correlations with POD and SOD. This result shows that drought results RL and decreasing RWC.

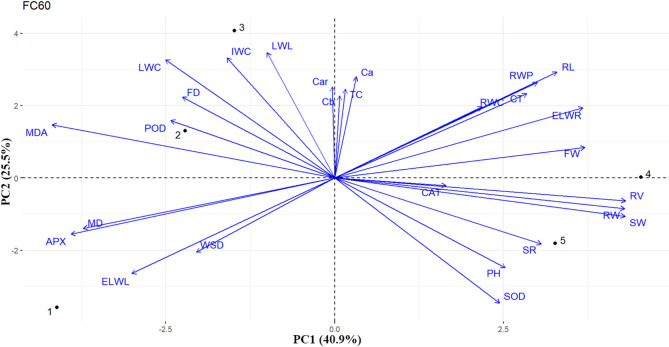

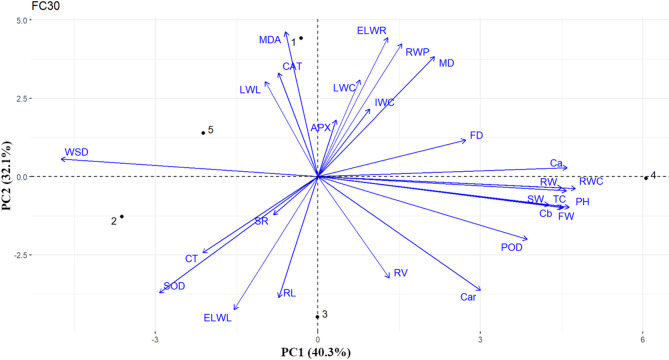

Association of traits

We used PCA to evaluate the association among twenty-eight biochemical and morpho-physiological traits. The cosine of the angle between two vectors refers to the extent of correlation where the acute angles (< 90°) represent positive correlation, whereas the obtuse angles (˃90°) indicate negative correlation. The length of the vectors reflects the extent of the variability42.

The first pair PCs explained around 60%, 66% and 72% of total variations under normal irrigation, moderate stress (60%), and sever stress (30%) conditions, respectively (Figs. 5 and 6, and 7). In non-stress conditions, the first two PCs accounted for 60.3% of the total variance, with PC1 explaining 33.3% and PC2 explaining 27% (Fig. 5). The vectors representing SW, RW, RL, APX, Cb, LWC, ELR, and RWP displayed angles of less than 90° with FW, suggesting a positive correlation among these variables. Additionally, FD exhibited angles of less than 90° with SR and RWC, while MD showed angles of less than 90° with CAT and Ca, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Bi-plot showing the relationship of biochemical and morpho-physiological traits under 100% of FC. MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase, RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water Retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, RWP: Relative water protective, PH: Plant height, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, FW: flower weight, CT: Canopy temperature, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

Fig. 6.

Bi-plot showing the relationship of biochemical and morpho-physiological traits under 60% of FC. MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase, RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water Retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, RWP: Relative water protective, PH: Plant height, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, FW: flower weight, CT: Canopy temperature, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

Fig. 7.

Bi-plot showing the relationship of biochemical and morpho-physiological traits under 30% of FC. MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase, RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water Retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, RWP: Relative water protective, PH: Plant height, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, FW: flower weight, CT: Canopy temperature, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

The initial two principal components account for 66% of the overall variance, with PC1 explaining 40.9% and PC2 explaining 25.5%, under 60% of FC (Fig. 6). The acute angles between vectors showed that flower weight was positively associated with root criteria including RV, RW and RL. In contrast, the obtuse angels between vectors indicated that plant water content such as LWC, IWC, ELWL and antioxidant enzyme activities such as POD and APX were negatively associated with FW (Fig. 6). In addition, the close acute angels between vectors indicated that root length was highly associated with RWC, RWP and CT under moderate stress (Fig. 6). Moreover, the acute angels between vectors showed that APX was positively associated with MD and LWC and POD were positively associated with FD (Fig. 6). APX was positively associated with MD, and LWC and PD were positively associated with FD (Fig. 6).

The first pair PCs explained 72% of total variation, with PC1 explaining 40.3% and PC2 explaining 32.1%, under 30% of FC (Fig. 7). The tight angels between TC, Cb and SW with FW indicated a high association among them. Moreover, vectors for RWC, RW, PH, POD and Ca had < 90° angles with FW. No association was observed between FW and WSD under severe stress (Fig. 7). The FD had < 90° angles with Ca, Cb, TC, RWC, RW and PH whereas, > 90° with CT and SOD.

By examining the obtained results and the amount of variance of each trait in different drought treatments, the most effective traits in moderate stress were biochemical traits such as Ca, Cb, Car, and TC. However, under severe stress, the biochemical traits like MDA, CAT, and APX were most effective criteria.

Factor analysis

Factor analysis is a statistical technique employed to expound the diversity among perceived, correlated variables in terms of conceivably fewer unobserved variables termed factors. The results of factor analysis on biochemical and morpho-physiological traits under 60% and 30% of FC are demonstrated in Table 7.

Table 7.

Factor analysis on biochemical and morpho-physiological traits under 60% and 30% of FC in pot marigold.

| 60% of FC | 30% of FC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | |

| FW | 0.52 | -0.43 | -0.06 | 0.91 | -0.25 | 0.31 |

| PH | 0.24 | -0.83 | 0.07 | 0.95 | -0.19 | 0.24 |

| FD | 0.09 | 0.97 | -0.20 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.76 |

| MD | -0.76 | 0.45 | -0.46 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.28 |

| RWC | 0.39 | 0.04 | -0.14 | 0.94 | -0.01 | 0.30 |

| WSD | -0.32 | -0.01 | 0.05 | -0.98 | -0.02 | -0.16 |

| IWC | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.08 | -0.04 | -0.15 | 0.93 |

| LWC | 0.06 | 0.93 | 0.33 | -0.11 | 0.08 | 0.96 |

| ELWR | 0.99 | -0.08 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.91 | 0.39 |

| ELWL | -0.97 | -0.14 | -0.15 | -0.07 | -0.64 | -0.76 |

| LWL | -0.08 | 0.30 | 0.91 | -0.23 | 0.32 | 0.14 |

| RWP | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.76 |

| SW | 0.70 | -0.69 | -0.18 | 0.95 | 0.16 | -0.13 |

| RW | 0.76 | -0.59 | -0.28 | 0.98 | 0.10 | -0.01 |

| SR | 0.21 | -0.94 | 0.22 | -0.16 | 0.15 | -0.27 |

| RV | 0.78 | -0.54 | -0.29 | 0.28 | -0.93 | 0.23 |

| RL | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.20 | -0.07 | -0.99 | -0.07 |

| CT | 0.94 | 0.23 | -0.13 | -0.18 | -0.02 | -0.98 |

| Ca | 0.14 | -0.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.23 | 0.08 |

| Cb | 0.07 | -0.08 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.04 | -0.06 |

| TC | 0.09 | -0.06 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.12 | -0.01 |

| Car | -0.18 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.73 | -0.49 | -0.21 |

| CAT | -0.17 | -0.72 | 0.52 | -0.12 | 0.67 | -0.13 |

| POD | -0.63 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.90 | -0.34 | -0.08 |

| APX | -0.69 | 0.33 | -0.06 | 0.05 | 0.82 | -0.21 |

| MDA | -0.52 | 0.81 | 0.21 | -0.25 | 0.87 | 0.27 |

| SOD | 0.06 | -0.74 | -0.67 | -0.40 | -0.62 | -0.66 |

| Eigenvalue | 11 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 5.7 |

| Proportion | 0.4 | 0.26 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.16 |

| Cumulative | 0.4 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.4 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

Significant values are in [bold].

MDA: Malondialdehyde, POD: Peroxidase, Ca: Chlorophyll a, Cb: Chlorophyll b, TC: Total chlorophyll, Car: Carotenoids, APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT: Catalase, RWC: Relative water content, WSD: Water saturation deficit, IWC: Initial water content, LWC: Leaf water content, ELWR: Excised leaf water Retention, ELWL: Excised leaf water loss, LWL: Leaf water loss, RWP: Relative water protective, PH: Plant height, FD: whole flower diameter, MD: Middle flower diameter, FW: flower weight, CT: Canopy temperature, SW: shoot weight, RW: root weight, RV: root volume, SR: ratio of shoot to root weight, RL: Root length, RV: root volume.

The factor analysis on the principal components data revealed that three significant factors with eigenvalues greater than one explain over 85% of the changes under stress treatments (Table 7). After rotation, coefficients above 0.5 were considered as significant coefficients, and the highlighted criteria are the most responsive characteristics to drought stress that undergo the most changes.

The first factor identified as the most crucial factor influencing changes in response to drought stress accounted for 40% of the variations observed under both 60% and 30% of FC in pot marigold. This first factor primarily encompassed RV, RL, CT, and ELWL, reflecting pot marigold’s adaptation through alterations in root structure and adjustment in canopy temperature, mainly associated with a stress avoidance mechanism under moderate drought conditions. In contrast, the primary factor under 30% of FC predominantly consisted of Ca, Cb, TC, Car, SW, RW, PH, FW, and RWC, exhibiting high and comparable values indicative of the significance of chlorophyll and carotenoid levels, as well as morphological adjustments in response to severe stress (Table 7). Consequently, pot marigold demonstrates distinct responses to drought stress under moderate and severe conditions.

The second most significant factor influencing changes in response to drought stress in marigold accounted for 26% and 30% of variations observed under 60% and 30% of FC, respectively. While LWC and IWC were emphasized in the second factor under 60% of FC, the second factor under 30% of FC highlighted the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as APX, MDA, and CAT mainly related to drought tolerance mechanisms.

The third factor accounted for 20% and 16% of variations related to the drought stress response in marigold under 60% and 30% of FC, respectively. This factor was primarily associated with chlorophyll content, including Ca, Cb, and TC, and LWL under moderate stress (60% of FC), and leaf water content, encompassing IWC and LWC, under severe stress (30% of FC).

In general, the factor analysis revealed that both avoidance and tolerance mechanisms play a significant role in the response to drought stress in marigold plants.

Discussion

The study aimed to assess how moderate and severe drought affect pot marigolds growth during the flowering phase and understand how the plant responds to drought conditions. The evaluation of various leaf water content criteria demonstrates a strong association between the level of soil moisture and the leaf water content, indicating that a decrease in soil moisture results in a corresponding reduction in leaf water content in this study. This allowed us a precise evaluation of the effects of moderate and severe drought stress on various characteristics of marigold plants. The reduced RWC under water-deficient conditions may be linked to the behavior of stomata and the root system of plants43. The severity of drought stress can also be accurately assessed by determining the WSD44. A decline in leaf water content could lead to a decrease in cell turgor pressure, potentially impacting the plant’s strength and structural integrity45.

The evaluation of seventeen morpho-physiological and phenological demonstrated that the key traits important for marigold cultivation remain largely unaffected by moderate drought stress, while they are being impacted by severe stress. However, in Tagetes minuta L., drought conditions led to a significant reduction in various morphological traits including plant height, stem diameter, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, stem fresh weight, stem dry weight, flower fresh weight, and flower dry weight15.

The increase of root length, decrease of shoot weight and height, and the elevated canopy temperature in our study indicated the absence of adequate water, plants experience higher temperatures and develop longer roots in search of water under severe drought stress. Therefore, pot marigold under water deficit conditions tend to exhibit shorter growth as a strategy to conserve water. This adaptive response allows the plants to allocate more resources towards strengthening their root system. Plants with deep and extensive root systems have the ability to improve water absorption and enhance drought tolerance9. Consistent with our findings, Riaz et al.. (2013)46 reported that drought stress led to a notable decrease in the dry weight of roots in Tagetes erecta L. The effectiveness of the root system, particularly in terms of depth, plays a crucial role in enhancing drought tolerance, surpassing the significance of root quantity and structure.

In addition to morphological traits, drought stress interrupts various physiological and biochemical processes in plants, including cell membranes. This can dislocate the transportation of solutes, photosynthesis rate, nutrient uptake, and translocation, causing electron leakage and excessive accumulation of ROS47,48. When plants are under severe stress, their ability to purify their cells can cause a decrease in the activities of SOD and POD enzymes as was detected in our study. Since the measurement of enzyme activity is influenced by both synthesis and degradation, a reduction in enzyme activity during stress can be attributed to either a decrease in synthesis or an increase in degradation. On the other hand, under drought stress, the accumulation of MDA is a common occurrence49–51 similar to our finding in the current study. Besides enzymes activities, the chlorophyll content measurement indicates the photosynthetic system’s ability to produce photosynthetic materials under stress conditions. The loss of chlorophyll content, as seen through the yellowing of leaves, indicates that a plant is being stressed by factors such as drought. This loss of chlorophyll content is a sign of reduced photosynthetic capacity, which ultimately affects the plant’s health52. The reduction of chlorophyll content was particularly detected under severe stress here. Disruption of the chloroplast membrane by ROS in plant cells can lead to degradation of photosynthesis and reduction in its activity53, and antioxidant enzyme activity depends on stress levels, plant species, tolerance limits, and ecological conditions54.

Considering alteration of different plant criteria in response to drought stress, it is important to identify the most effective traits and mechanisms that are involved in pot marigold response to drought stress. It is known that plant response to drought stress involves three primary mechanisms: drought avoidance, where plants regulate water absorption to prevent stress; drought tolerance, where plants withstand stress to minimize yield reduction; and drought escape, where plants avoid stress through strategies like early flowering55. Overall, our research on various aspects of drought response in pot marigold suggested that the plant predominantly employs drought tolerance mechanisms, while also utilizing some drought avoidance strategies.

Therefore, to assess genetic parameters and specific characteristics, use of BLUEs for ANOVA were carried out in this study to make better breeding and yield forecasting decisions. However, BLUEs offer an unbiased free crop forecast that is useful for resource and decision-making accordingly56.

Correlation coefficients and canonical correlation analysis can effectively identify the most correlated traits in response to drought stress. By using canonical correlation analysis, Balkaya and his colleagues (2011)57 found that in populations of winter squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.), the fruit’s length and dimensions had the biggest impact on the explanatory power of canonical variables. According to our results, the first pair of canonical variables show that different antioxidants have unequal contributions to drought stress tolerance. Therefore, pot marigold response to drought stress through allocating the energy towards increasing agronomic drought-adaptive traits like root length and accumulation of antioxidants under drought conditions. In addition, we utilized PCA to study the association among evaluated traits. The PCA is commonly used to identify the selection criteria to classify the genotypes of drought-tolerant in crops like barley and wheat58,59. The PCAs in the comparison of non, moderate, and severe stress conditions demonstrated that there is a strong associated between flower size and RWC only in non-stress conditions. However, a strong association between flower size and root weight traits was observed in non-stress and severe stress conditions. Moreover, strong associations were observed between the flower weight and root length traits in non-stress and moderate-stress conditions.

Factor analysis showed that most of the changes in leaves indicated that the drought tolerance mechanism might be the preferred response to drought stress in marigold. There is a strong relationship between enzymatic factors and leaf morpho-physiological factors. Reduction of canopy temperature in the first factor in moderate stress, shows the avoidance of dryness caused by the preservation of leaf water, which itself is the result of biochemical and ionic changes, especially in the membrane of leaf cells, with changes in antioxidant enzymes and reduced canopy temperature that induce drought tolerance are related.

Therefore, the second less important mechanism of drought response in marigold is the effect of water retention on root development and the transfer of photosynthetic materials in shoots, which can be partially considered as an avoidance mechanism.

They can be considered as a factor of reproductive growth after applying stress and the relationship between photosynthesis and transfer of assimilates with reproductive growth against applying stress is called and again emphasizes the mechanism of avoiding drought by increasing chlorophyll and accumulation of assimilates. The results suggest that photo-oxidation of thylakoid constituents is a major contributing factor in drought stress.

Drought-induced stress has been observed to exert noteworthy impacts on the functionality of antioxidative enzymes, including POD, CAT, and APX, as well as on the content of chlorophyll60. Additionally, the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments, such as Ca and Cb, is impeded under drought stress61. The decrease in chlorophyll concentration and functioning of photosystem II (PSII) may serve as indicators of water scarcity62. Furthermore, the ultimate efficiency of photochemical processes and the range of Ca fluorescence initiation curve have been observed to decrease under arid conditions63. In this research, to examine physiological and biochemical data under moderate and severe drought stress, we used a mixed model approach based on REML for variance component estimation. REML has been acknowledged as the standard technique for generating unbiased and accurate estimates of random effects in unbalanced or complicated experimental datasets. Then, BLUEs were utilized to estimate fixed effects, which gave the most dependable and unbiased linear estimates for the comparison of genotypes and drought treatments. As in previous research in crops like maize64 and common bean65, where the use of REML-BLUP or BLUE greatly enhanced selection accuracy and interpretability, the joint application of REML and BLUE in our work also resulted in strong and reliable conclusions regarding plant behavior under water deficit. Considering different aspects of drought response in this study, we were able to conclude that pot marigold does not escape drought stress but rather employs both avoidance and tolerance mechanisms. These include root system elongation for avoidance and adjustment of oxidative enzymes and other morpho-physiological traits to cope with the stress.

Conclusion

Our results show that most of the important morpho-physiological traits, including days from budding to flowering and pollination, number of flowers, flower weight and diameter, and plant height, are not significantly affected by reducing water supply to 60% of FC, making it suitable for planting in the green spaces in semi-arid regions. Moreover, the results indicate that pot marigold does not employ a drought escape mechanism in response to drought stress by shortening its flowering period compared to normal irrigation (100% of FC). In general, it can be concluded that the pot marigold antioxidant enzymes activity has a good ability to reduce the adverse effects of drought stress. Considering different aspects of drought response in this study, we were able to conclude that pot marigold employs a combination of avoidance and tolerance mechanisms, including root system elongation, adjustments in antioxidant enzyme activity, and chlorophyll and carotenoid content to cope with drought stress. These results represent a significant advance in understanding the level of tolerance and the responsive mechanisms to drought stress in pot marigold during the most critical stage of its life cycle, when reduced rainfall usually occurs in its cultivation area.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Amir Tavassoli; Conducted the experiment, Collected the data, Contributed to statistical analysis and writing the manuscript, Elahe Tavakol; Conceived the project, Designed experiments, Interpreted the results, Contributed to statistical analysis and writing the manuscript: Bahram Heidari, and Alireza Afsharifar; Contributed to data analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shiraz University and Ministry of Science, Iran.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Muley, B. P., Khadabadi, S. S. & Banarase, N. B. Phytochemical constituents and Pharmacological activities of Calendula officinalis L. (Asteraceae): a review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.8, 455–465 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora, D., Anita, R. & Sharma, A. A review on phytochemistry and ethnopharmacological aspects of genus. Calendula Pharmacognosy Reviews. 7 (14), 179–187 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulsen, E. Contact sensitization from Compositae-containing herbal remedies and cosmetics. Contact Dermat.47, 189–198 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chauhan, A. S. et al. Valorizations of marigold waste for high-value products and their industrial importance: a comprehensive review. Resources11 (10), 91 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar, A., Prakash, S. & Mishra, M. Marigold as a trap crop for the management of tomato fruit borer, Helicoverpa armigera in Tarai region of Uttar Pradesh. Sci. Temper.3 (1&2), 65–68 (2023).

- 6.Mir, R. A., Mohammad, A., Ahanger, R., Agarwal, M. & Marigold From mandap to medicine and from ornamentation to remediation. Am. J. Plant. Sci.10 (2), 309–338 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thaneshwari, S. R. Commercial application of lutein: marigold flower pigment. Ecol. Environ. Conserv.28, S315–S320 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalvatchev, Z., Walder, R. & Garzaro, D. Anti-HIV activity of extracts from Calendula. Biomed. Pharmacother.51 (4), 176–180 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farooq, M., Wahid, A., Kobayashi, N., Fujita, D. & Basra, S. M. A. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Agron. Sustain. Dev.29, 185–212 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain, S., Khaliq, A. & Ashraf, M. Drought stress in plants: causes, effects and tolerance mechanisms. In Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance 1–24 (Springer, 2018).

- 11.Kirnak, H., Kaya, C., Tas, I. & Higgs, D. The influence of water deficit on vegetative growth, physiology, fruit yield and quality in eggplants. Bulgarian J. Plant. Physiol.27 (3–4), 34–46 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortazaei nejad, F. & Jazizadeh, E. Effects of water stress on morphological and physiological indices of Cichorium intybus L. for introduction in urban landscapes. J. Plant. Process. Function. 6 (21), 279–290 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khahani, B., Tavakol, E., Shariati, V. & Rossini, L. Meta-QTL and ortho-MQTL analyses identified genomic regions controlling rice yield, yield-related traits and root architecture under water deficit conditions. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 6942 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schonbeck, M. W. & Norton, T. A. A role for abscisic an investigation of drought avoidance in intertidal Fucoid algae. Bot. Mar.22 (3), 133–144 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babaei, K., Moghaddam, M., Farhadi, N. & Pirbalouti, A. G. Morphological, physiological and phytochemical responses of Mexican marigold (Tagetes Minuta L.) to drought stress. Sci. Hort.284, 110–116 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedghi, M., Sharifi, R. S., Pirzad, A. R. & Amanpour-Balaneji, B. Phytohormonal regulation of antioxidant systems in petals of drought stressed pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L). J. Agricultural Sci. Technol.14, 869–878 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askari, E. & Ehsanzadeh, P. Drought stress mitigation by foliar application of Salicylic acid and their interactive effects on physiological characteristics of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) genotypes. Acta Physiol. Plant.37, 4–18 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson, C. R. Best linear unbiased Estimation and prediction under a selection model. Biometrics31 (2), 423–447 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lista, L. The bias of the unbiased estimator: a study of the iterative application of the BLUE method. Nuclear Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A-Accelerators Spectrometers Detectors Assoc. Equip.764, 82–93 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jafarzadeh, L., Omidi, H. & Bostani, A. A. The study of drought stress and bio fertilizer of nitrogen on some biochemical traits of marigold medicinal plant (Calendula officinalis L). J. Plant. Res.27 (2), 180–193 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gholinezhad, E. Effect of drought stress and stress modifier on biochemical traits of pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L). Plant. Process. Function. 8 (33), 213–228 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhtar, G. et al. Chitosan-Induced physiological and biochemical regulations confer drought tolerance in pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L). Agronomy12 (2), 474 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalilzadeh, R., Sharifi, R. S. & Pirzad, A. Mitigation of drought stress in pot marigold (Calendula officinalis) plant by foliar application of methanol. J. Plant. Physiol. Breed.10 (1), 71–84 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blum, A. Plant Breeding for water-limited Environments Vol. 1 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

- 25.Barrs, H. D. Determination of water deficits in plant tissue. In Water Deficits and plant growth (ed. Kozlowski, T. T.) 235–368 (Academic Press, 1968).

- 26.Clarck, J. M. & Mac-Caig, T. N. Excised leaf water relation capability as an indicator of drought resistance of Triticum genotypes. Can. J. Plant Sci.62, 571–576 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manette, A. S., Johnson, R. C., Carver, B. F. & Mornhinweg, D. W. Water relations in winter wheat as drought resistance indicators. Crop Sci.28 (3), 526 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing, H. et al. Evidence for the involvement of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in osmotic stress. Tolerance of wheat seedling: inverse correlation between leaf abscisic acid accumulation and leaf water loss. Plant. Growth Regul.42, 61–68 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasheminasab, H., Assad, M. T., Ali Akbari, A. & Sahhafi, S. R. Evaluation of some physiological traits associated with improved drought tolerance in Iranian wheat. Annuals Biol. Res.3, 1719–1725 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beauchamp, C. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem.44, 276–287 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol.105, 121–126 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herzog, V. & Fahimi, H. Determination of the activity of peroxidase. Annual Biochem.55, 554–562 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant. Cell. Physiol.22, 867–880 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du, Z. & Bramlage, W. J. Modified thiobarbituric acid assay for measuring lipid oxidation in sugar-rich plant tissue extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem.40, 1566–1570. 10.1021/jf00021a018 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lichtenthaler, H. & Wellburn, A. R. Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans.603, 591–592 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilmour, A. R., Cullis, B. R. & Verbyla, A. P. Accounting for natural and extraneous variation in the analysis of field experiments. J. Agricultural Biol. Environ. Stat.2, 269–293 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Payne, R. W., Harding, S. A., Murray, D. A., Soutar, D. M. & Bird, D. B. The Guide To the GenStat Release 15 (VSN International, 2012).

- 38.Dodge, Y. The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- 39.Johnson, R. A. & Wichern, D. W. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis, 6th Edition (Springer, 2015).

- 40.Srinivasan, A., Kannan, M., Ravikesavan, R., Jeyakumar, P. & Subramaniam, S. Association and path analysis in marigold (Tagetes spp.) genotypes under drought stress conditions. J. Pharmacogn Phytochem. 7 (6), 1502–1506 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brdar-Jokanović, M., Girek, Z., Pavlović, S., Ugrinović, M. & Zdravković, J. Shoot and root dry weight in drought exposed tomato populations. Genetika46 (2), 495–504 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tahmasebi, S., Heidari, B., Pakniyat, H. & Jalal Kamali, M. R. Independent and combined effects of heat and drought stress in the seri M82 × Babax bread wheat population. Plant. Breed.133 (6), 702–711 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merah, O. Potential importance of water status traits for durum wheat improvement under mediterranean conditions. J. Agricultural Sci.137, 139–145 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, J. et al. GRACE combined with WSD to assess the change in drought severity in arid Asia. Remote Sens.14 (14), 3454–3454 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar, S., Sachdeva, S., Bhat, K. V. & Vats, S. Plant responses to drought stress: physiological, biochemical and molecular basis. In Biotic Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants (eds. Vats, S. ed.) 1–25 (Springer, 2018).

- 46.Riaz, A. et al. Effect of drought stress on growth and flowering of marigold (Tagetes erecta L). Pak. J. Bot.45, 123–131 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nalina, M. et al. Water deficit-induced oxidative stress and differential response in antioxidant enzymes of tolerant and susceptible tea cultivars under field condition. Acta Physiol. Plant.43, 10 (2021).

- 48.Zhou, J. et al. Transcriptome profiling reveals the effects of drought tolerance in Giant Juncao. BMC Plant Biol.21, 2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau, S. E., Hamdan, M. F., Pua, T. L., Saidi, N. B. & Tan, B. C. Plant nitric oxide signaling under drought stress. Plants10, 360 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fiasconaro, M. L. et al. Role of proline accumulation on fruit quality of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) grown with a K-Rich compost under drought conditions. Sci. Hort.249, 280–288 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu, Y. et al. Drought resistance mechanisms of Phedimus Aizoon L. Sci. Rep.11, 13600 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pask, A., Pietragalla, J., Mullan, D. & Reynolds, M. P. Physiological Breeding II: A Field Guide To Wheat Phenotyping (CIMMYT, 2012).

- 53.Sihem, T. et al. Effect of drought on growth, photosynthesis and total antioxidant capacity of the saharan plant Oudeneya Africana. Environ. Exp. Bot.176, 104099 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zouari, M. et al. Exogenous proline mediates alleviation of cadmium stress by promoting photosynthetic activity, water status, and antioxidative enzymes activities of young date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.128, 100–108 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basra, A. S. & Basra, R. K. Mechanisms of Environmental Stress Resistance in Plants1–43 (Harwood Academic, 1997).

- 56.Nossam, S. C., Katakam, R. A., Pulastya, G. & Venugopalan M. Enhanced crop yield prediction using machine learning techniques 1–6 (2024).

- 57.Balkaya, A., Cankaya, S. & Ozbakir, M. Use of canonical correlation analysis for determination of relationships between plant characters and yield components in winter squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.) populations. Bulgarian J. Agricultural Sci.17 (5), 606–614 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tavakol, E., Elbadry, N., Tondelli, A., Cattivelli, L. & Rossini, L. Genetic dissection of heading date and yield under mediterranean dry climate in barley (Hordeum vulgare L). Euphytica212, 343–353 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ali, I. et al. Biochemical and phenological characterization of diverse wheats and their association with drought tolerance genes. BMC Plant Biol.19 (1), 326 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, A. et al. Effect of drought on photosynthesis, total antioxidant capacity, bioactive component accumulation, and the transcriptome of Atractylodes lancea. BMC Plant Biol.21, 293 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, H., Wang, H., Zhou, Q. & Mao, P. Ultrastructural and photosynthetic responses of pod walls in alfalfa to drought stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21 (12), 4457 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.David, A., Gustavo, S., Ligarreto-Moreno, A. & Restrepo-Díaz, H. Chlorophyll α fluorescence parameters as an indicator to identify drought susceptibility in common Bush bean. Agronomy9 (9), 526 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Juzoń, K., Czyczyło-Mysza, I., Ostrowska, A., Marcińska, I. & Skrzypek, E. Chlorophyll fluorescence for prediction of yellow lupin (Lupinus luteus L.) and pea (Pisum sativum L.) susceptibility to drought. Photosynthetica57 (4), 950–959 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zorić, M. et al. Best linear unbiased predictions of environmental effects on grain yield in maize variety trials of different maturity groups. Agronomy12 (4), 922 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carvalho, I. R. et al. REML/BLUP applied to characterize important agronomic traits in segregating generations of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L). AJCS14 (3), 391–399 (2020). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.