Abstract

Neurofeedback has been utilized to treat a variety of mental health issues by influencing brainwave patterns using auditory and/or visual feedback. Despite a plethora of research, there is a significant gap regarding why neurofeedback is not more commonly utilized in mental health care practice. This study sought to address this gap by posing the question: What factors are associated with psychotherapists’ self-reported interest in adopting neurofeedback into their current practice? This study utilized the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to explore factors associated with outpatient psychotherapists’ interest in implementing neurofeedback in their practices. The primary variables of interest were years in practice, cost as the main barrier to implementation, and type of practice setting. Surveys were completed online by licensed psychotherapists (N = 500). A logistic regression analysis found that, compared to those practicing in a solo private practice, psychotherapists practicing in community mental health clinics/agencies (adjusted OR: 1.77, 95% confidence interval, CI, [0.99, 3.15], p = .0524) and other outpatient settings (adjusted OR: 1.81, 95% CI [0.95, 3.44], p = .0708) had higher odds of being interested in neurofeedback. Finally, compared to those who did not believe that neurofeedback would be welcome in their practice setting or were unsure, those who reported believing neurofeedback would be welcome (adjusted OR: 3.38, 95% CI [2.18, 5.26], p < .0001) had much higher odds of being interested in neurofeedback. This study found that inner setting factors had the most significant association with psychotherapists’ interest in implementing neurofeedback. These findings point to potential areas of focus to increase the uptake of neurofeedback in mental health care settings.

Keywords: neurofeedback, consolidated framework for implementation research, implementation science, psychotherapy, mental health

Electroencephalogram (EEG) neurofeedback is an intervention that utilizes a brainwave-to-computer interface to provide auditory and/or visual feedback to encourage and inhibit specific brainwave patterns based on the findings of a quantitative electroencephalogram and/or an individual’s symptoms. The International Society for Neuroregulation and Research simply defines neurofeedback as “a type of biofeedback that involves learning to control and optimize brain function. Neurofeedback may or may not include the use of a direct stimulus or task when teaching the brain new ways of performing” (International Society for Neuroregulation and Research, 2021). A variety of independent studies have found neurofeedback to be highly effective in the reduction of many mental health symptoms. However, due to the wide variety of practitioner approaches to neurofeedback (including variety within prevalence of clinical use, protocols including what frequencies are targeted and where on the scalp electrodes are placed, and recommended number of sessions), inconsistent research design impacting meta-analysis (i.e., lack of controls, inconsistent use of sham conditions, and lack of funding), the neurofeedback field has struggled to establish a firm base of randomized controlled trials comparable to similarly effective mental health treatments (Fisher et al., 2016; Kuznetsova et al., 2023; Micoulaud-Franchi et al., 2021; Riesco-Matías et al., 2021; Trocki, 2006; van Der Kolk et al., 2016). The results of some outcomes studies in neurofeedback suggest comparable symptom reduction to current gold standard treatments. For example, Nicholson et al. (2020) found a 61.1% posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) remission rate. Similar findings were reported for a study of symptom reduction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Purper-Ouakil et al., 2022). However, despite these compelling findings, there are still some within the mental health field who question the broader credibility of the intervention, most recently in the treatment of ADHD (Kuznetsova et al., 2023; Pigott et al., 2021; Thibault et al., 2021). This could be, in part, due to some conflict within and across fields in the history of neurofeedback, which includes a variety of different methods and approaches (Robbins, 2008). Study comparisons and meta-analyses have also proven difficult for the neurofeedback field due to a large variety of mental health outcomes being measured and protocols being utilized. The two studies referenced above provide a great example of this dynamic. Purper-Ouakil et al.’s (2022) ADHD study focused on reducing the ratio of θ to β in frontal areas of the brain and increasing what is known as the sensorimotor rhythm (7–11 Hz) in central brain regions. On the other hand, Nicholson et al.’s (2020) PTSD study utilized a protocol that rewarded the down-regulation of α (8–12 Hz) at the midline of the parietal lobe. Speaking about credibility broadly, then, without the specificity of distinct protocols and/or specific symptoms or disorders is difficult.

Perhaps due to these factors, neurofeedback is not particularly well-known or utilized within mental health, which has led to calls for future research into possible barriers and facilitators to the use of neurofeedback in psychotherapy treatment (Larson et al., 2010). An exploration of practitioners’ perspectives on the advantages, disadvantages, and essential components of practicing neurofeedback identified specific suggestions on potential barriers to effective implementation (Larson et al., 2010). For example, study participants mentioned the complexity of learning neurofeedback and the commitment it entails. To date, research has focused on outcomes of the use of neurofeedback to treat specific mental health disorders and not on why, despite its efficacy, neurofeedback is underutilized in outpatient mental health and what factors contribute to this trend.

In the first issue of the journal, Implementation Science, Eccles and Mittman (2006, p. 1) defined implementation science as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practice into routine practice and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services.” During the past 60 years, the field of implementation science has sought to bridge this gap between research and practice by focusing on factors that influence the uptake of routine use of an intervention (Bauer & Kirchner, 2020).

One of the most popular frameworks within the implementation science field is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009). The CFIR was developed by Damschroder et al. (2009) to provide an overarching framework to aid in the exploration of “essential factors” of the process of intervention implementation. The first domain of the CFIR is characteristics of the intervention that is being implemented. This domain includes factors such as the complexity and cost of the intervention as well as aspects such as the intervention’s adaptability and the strength and quality of the evidence supporting it. The next two domains of the CFIR are the inner setting and the outer setting. Factors in these domains include the specific, immediate context for the intervention (i.e., structural characteristics, culture, and implementation climate) and the broader context (i.e., outlying clinics, external policies, and incentives). The fourth domain is the characteristics of individuals involved in the implementation process/intervention. This domain includes factors such as personal attributes, self-efficacy, and the individual’s stage of change. Four of the five CFIR domains were utilized in the design of this study: individual characteristics, inner and outer settings, and intervention characteristics (see Figure 1). The fifth domain, implementation process, was not included in this study since most participants would not have any experience implementing neurofeedback and thus would be unfamiliar with the process of implementing it.

Figure 1.

Survey Research Design Centered Around Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Domains

To make neurofeedback more available to people struggling with the impact of mental illness, we need to know what enables or inhibits mental health providers from implementing the intervention. To date, no such exploration into specific implementation factors has been initiated in the field of neurofeedback. Very little knowledge has been gleaned from the experiences and perspectives of mental health providers’ who are familiar with a variety of mental health interventions, despite the necessity of practitioner acceptance and motivation for successful implementation of evidence-based interventions (Berenholtz & Pronovost, 2003; Kettlewell, 2004). This study utilized the CFIR (see Figure 1) to answer the research question for this study: What factors are associated with psychotherapists’ self-reported interest in adopting neurofeedback into their current practice? The aim of this study was to begin filling this gap by exploring a range of possible contributing factors using the CFIR as a guide (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Method

This study explored factors associated with licensed psychotherapists’ interest in implementing neurofeedback into their outpatient mental health practice. The study protocol was approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Internal Review Board (Protocol No. 274998) and received an informed consent waiver.

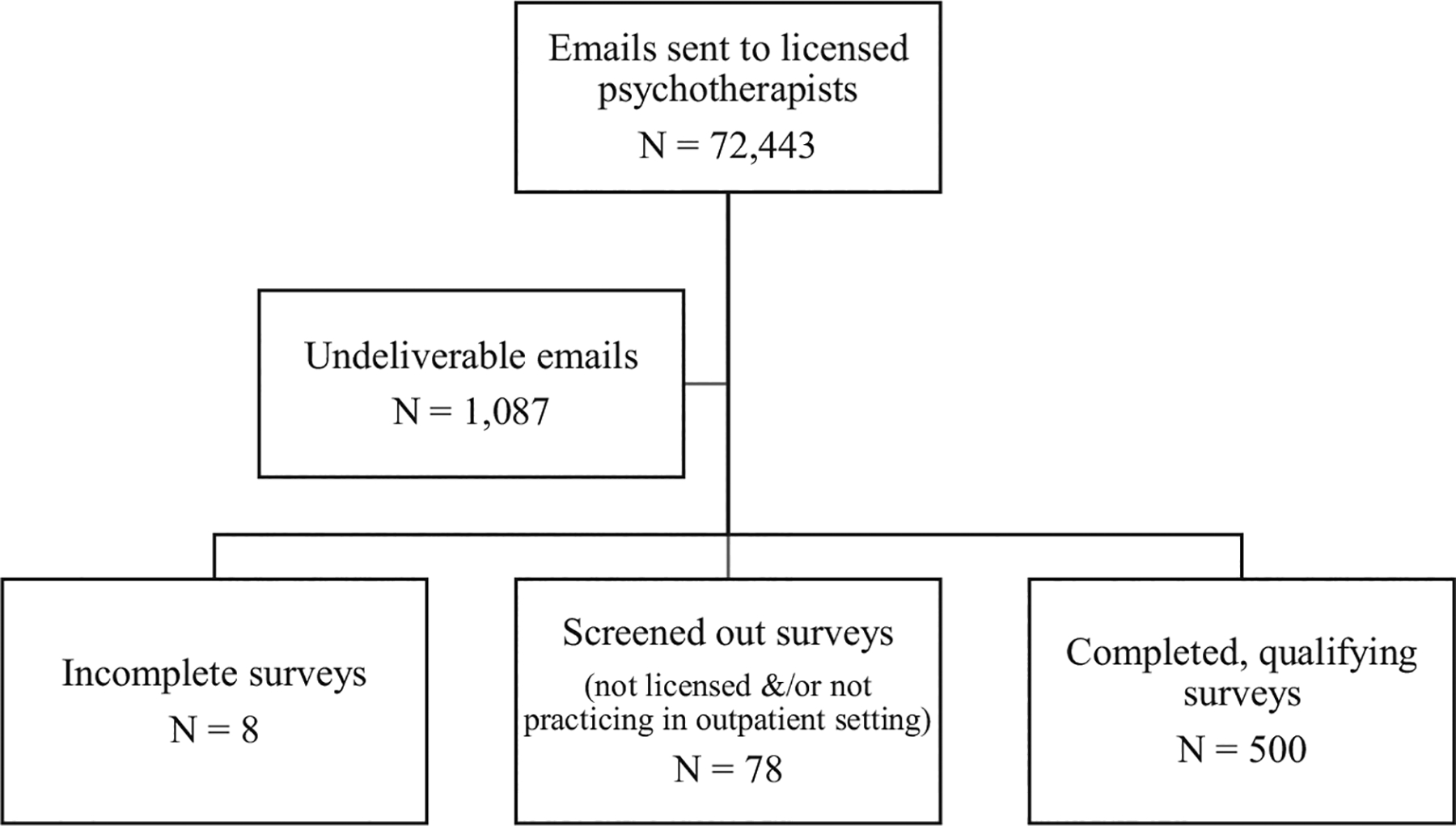

We sent quantitative online survey invitations to 72,443 licensed mental health professionals across seven states within the United States (Tennessee, Ohio, Maine, Michigan, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Wyoming). During the research design phase of this study, the principal investigator (WN) reached out to psychotherapy licensing boards for each of the 50 states in the United States to determine which states’ boards offer email addresses for their licensees to the public, which resulted in an initial sample of 72,443. We created a database in REDcap that included the 72,443 email addresses and used this database to send out three automated survey invitations, each separated by 2 weeks during March and April 2023. The survey was left open for an additional 4 weeks and closed in May 2023. This convenience sample was chosen due to our goal of sampling a large population of licensed psychotherapists with different specialties and years of experience who may or may not have knowledge of or experience with neurofeedback (Etikan, 2016). The inclusion criteria for this study were (a) holding an active license to practice psychotherapy and (b) currently practicing in an outpatient setting (see Table 1 for information about the sample). Of the final 586 initiated surveys (see Appendix for full survey), 500 surveys were completed, eight were incomplete (not used in analysis), and 78 initiated the survey but did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Psychotherapists’ Survey Characteristics (n = 500)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 17 (3.4) |

| Black/African American | 57 (11.4) |

| White | 410 (82) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 2 (0.4) |

| Asian | 4 (0.8) |

| Other | 10 (2) |

| Age | |

| 20–39 | 127 (25.4) |

| 40–59 | 259 (51.8) |

| 60+ | 114 (22.8) |

| Gender identity | |

| Female | 408 (81.6) |

| Male | 89 (17.8) |

| Nonbinary | 3 (0.6) |

| Average yearly income | |

| Under $25,000 | 25 (5) |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 95 (19) |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 172 (34.4) |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 104 (20.8) |

| $100,001+ | 73 (14.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 31 (6.2) |

| Highest earned degree | |

| Masters | 435 (87) |

| Doctorate | 63 (12.6) |

| Medical Doctor | 2 (0.4) |

| Years of practice | |

| 0–9 | 183 (36.6) |

| 10–29 | 247 (49.4) |

| 30+ | 70 (14) |

| Type of practice setting | |

| Community mental health clinic/agency | 119 (23.8) |

| Solo private practice | 165 (33) |

| Group private practice | 143 (28.6) |

| Other outpatient setting | 73 (14.6) |

| Familiarity with neurofeedback before survey | |

| Not at all familiar | 77 (15.4) |

| Slightly familiar | 195 (39) |

| Somewhat familiar | 116 (23.2) |

| Moderately familiar | 83 (16.6) |

| Extremely familiar | 29 (5.8) |

Figure 2.

Recruitment Flowchart

Prior to data collection, we ran a simple power analysis using Statistical Analysis System to approximate the appropriate sample size for testing the difference between group means, the results of which are displayed in Table 2. Due to common variability in response rates on similar surveys (Baruch & Holtom, 2008; Jepson et al., 2005; Story & Tait, 2019; Weissman et al., 2006), we used three different hypothetical response rates for the power analysis: a low response rate (N = 200), a moderate response rate (N = 350), and a high response rate (N = 500). The information displayed in Table 2 is based on a test for the difference in likelihood to implement neurofeedback between early and late career status. The number of surveys collected was sufficient to power a model of group differences for our outcome. The online survey included exploratory questions about factors within four of the five CFIR domains (see Figure 1). The survey began with 26 questions about personal characteristics of the provider and their work setting. The survey then posed five questions about participants familiarity, perception, and experience with neurofeedback before providing a brief description of neurofeedback that was written and approved by a group of experienced neurofeedback practitioners. The inclusion of this description was meant to ensure that all participants had some form of introduction to neurofeedback before answering questions about specifics aspects of its implementation. Finally, 29 questions asked about their perspective on neurofeedback.

Table 2.

Power Table for Likelihood to Implement With Variable Years in Practice

| Outcome scenario: Group proportions reporting likelihood to implement neurofeedback (yes/no) | Estimated power | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low response rate N = 200 |

Moderate response rate N = 350 |

High response rate N = 500 |

|

| Early career, 10% Late career, 20% |

0.508 | 0.747 | 0.882 |

| Early career, 10% Late career, 30% |

0.948 | 0.997 | >0.999 |

| Early career, 20% Late career, 30% |

0.371 | 0.580 | 0.734 |

| Early career, 20% Late career, 40% |

0.876 | 0.985 | 0.999 |

| Early career, 30% Late career, 40% |

0.316 | 0.501 | 0.650 |

| Early career, 30% Late career, 50% |

0.828 | 0.971 | 0.996 |

| Early career, 50% Late career, 75% |

0.960 | 0.999 | >0.999 |

To answer our research question, we used bivariate descriptive models and multiple logistic regression analysis to explore factors within each of the above categories related to the binary outcome: whether or not psychotherapists are interested in pursuing the implementation of neurofeedback. This outcome was assessed by a yes/no question at the end of the survey (“Are you interested in learning more about implementing neurofeedback into your practice?”). This broad question was chosen, instead of a question about current willingness or readiness to implement the intervention, due to the presumed lack of knowledge by participants. For our model development, we utilized an abridged version of the steps for purposeful variable selection outlined by Hosmer et al. (2013). This abridged form of Hosmer’s method, which allows for more liberal inclusion criteria, was chosen since very little is known about this topic. This strategy was most appropriate for this type of exploratory phase of implementation research to help reduce the chance of missing any potential new information and allows for the exploration of a wide range of potential factors that may enable or inhibit providers’ interest in neurofeedback.

The first step in our analysis included the use of Pearson chi-square tests and t tests for each variable to determine association between each individual variable and the primary outcome (see Table 3). An initial adjusted model was created using all variables with a p value below .25. Next, clinically significant variables contributing to our outcome were carried forward from the bivariate tests. We defined “clinical significance” by identifying p values around and below .05 as well as other factors, such as the Wald chi-square results, adjusted odds ratio, and clinical intuition. Our goal was to align with conventional statistical significance while also avoiding what Amrhein et al. (2019) call “dichotomania,” which can result in an overreliance on a hard cutoff point at the cost of clinical knowledge and critical thinking. In addition to the p value, we considered effect size and the precision of confidence intervals (CIs) to evaluate clinical significance (Li et al., 2021). In this study, there was one variable that was just over the .05 cutoff that appeared to have an impact on the outcome being measured and fit into the clinical picture of implementation addressed by this research question.

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations Between Survey Variables and Interest Outcome

| Variable | Interest in learning more about NFB | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N = 309 (61.8%) |

No N = 191 (38.2%) |

p | |

| Primary variables | |||

| Years in practice | 13.5 | 17.7 | <.0001a |

| Type of practice setting | .1499a | ||

| Community mental health clinic/agency | 81 (68.07) | 38 (31.93) | |

| Solo private practice | 91 (55.15) | 74 (44.85) | |

| Group private practice | 91 (63.64) | 52 (36.36) | |

| Other outpatient setting | 46 (63.01) | 27 (36.99) | |

| Cost as main barrier | .0616a | ||

| Cost | 222 (64.53) | 122 (35.47) | |

| Other main barrier | 87 (55.7) | 69 (44.23) | |

| Secondary variables | |||

| Age | 47.4 | 51.9 | .0001a |

| Area of specialty | .4135 | ||

| Addictions | 44 (65.67) | 23 (34.33) | |

| Trauma | 138 (66.03) | 71 (33.97) | |

| Eating disorders | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | |

| Couples/marital | 13 (54.17) | 11 (45.83) | |

| Family therapy | 12 (46.15) | 14 (53.85) | |

| Play therapy | 9 (56.25) | 7 (43.75) | |

| Other | 90 (58.82) | 63 (41.18) | |

| Type of client pay | .7651 | ||

| Cash/private pay only | 40 (68.97) | 18 (31.03) | |

| Cash/private pay and insurance | 176 (61.11) | 112 (38.89) | |

| Insurance only | 58 (62.37) | 35 (37.63) | |

| Grant funding | 11 (57.89) | 8 (42.11) | |

| Other | 24 (57.14) | 18 (42.86) | |

| Acceptability of intervention measure (scale range from 1 to 5) | 4.1 | 3.5 | <.0001a, b |

| Feasibility of intervention measure (scale range from 1 to 5) | 3.9 | 3.7 | <.0001a |

| Intervention appropriateness measure (scale range from 1 to 5) | 4 | 3.3 | <.0001a, b |

| Most significant facilitator | .7505 | ||

| Basic NFB training can be completed online | 45 (56.25) | 35 (43.75) | |

| Faster treatment progress | 16 (69.57) | 7 (30.43) | |

| Long-term effects | 83 (61.48) | 52 (38.52) | |

| Self-regulation effectiveness | 31 (60.78) | 20 (39.22) | |

| 85%−90% efficacy | 134 (63.51) | 77 (36.49) | |

| Tertiary variables | |||

| Gender identity | .3930 | ||

| Female | 251 (61.52) | 157 (38.48) | |

| Male | 55 (61.8) | 34 (38.2) | |

| Nonbinary | 3 (100) | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | |

| Race/ethnicity | .5449 | ||

| White | 247 (60.24) | 163 (39.76) | |

| Black/African American | 40 (70.18) | 17 (29.82) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 13 (76.47) | 4 (23.53) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Asian | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | |

| Other | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | |

| Average yearly income | .7896 | ||

| Under $25,000 | 18 (72) | 7 (28) | |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 54 (56.84) | 41 (43.16) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 108 (62.79) | 64 (37.21) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 65 (62.5) | 39 (37.5) | |

| $100,001+ | 46 (63.01) | 27 (36.99) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 18 (58.06) | 13 (41.94) | |

| Highest degree earned | .1571a | ||

| Masters | 274 (62.99) | 161 (37.01) | |

| Doctorate or Medical Doctor | 33 (53.85) | 30 (46.15) | |

| Number of clinicians in practice setting | 19.3 | 9.0 | .0455a |

| Average number of weekly therapy hours | 21.7 | 19 | .0056a |

| Colleagues who practice NFB in setting | .4258 | ||

| Yes | 29 (67.44) | 14 (32.56) | |

| No | 280 (61.27) | 177 (38.73) | |

| Colleagues who practice NFB outside setting | .0391a | ||

| Yes | 122 (67.78) | 58 (32.22) | |

| No | 187 (58.44) | 133 (41.56) | |

| Whether NFB welcome in setting | <.0001a | ||

| Yes | 212 (68.61) | 69 (24.56) | |

| No | 9 (26.47) | 25 (73.53) | |

| Unsure | 88 (47.57) | 97 (52.43) | |

| Familiarity with NFB (presurvey) | .0663a | ||

| Not at all familiar | 39 (50.65) | 38 (49.35) | |

| Slightly/somewhat familiar | 195 (62.7) | 116 (37.3) | |

| Moderately/extremely familiar | 75 (66.96) | 37 (33.04) | |

| Perception of NFB | .0015a | ||

| Very/somewhat negative | 5 (45.45) | 6 (54.55) | |

| Neither positive nor negative | 96 (52.46) | 87 (47.54) | |

| Very/somewhat positive | 208 (67.97) | 98 (32.03) | |

Note. Row percent in parentheses. NFB = neurofeedback.

p value below model cutoff of .25.

Taken out of model due to issues of multicollinearity.

Results

Data collection resulted in 500 completed surveys (see Figure 2). The sample was 82% White, 11.4% Black/African American, and 3.4% Hispanic; 81.6% identified as female and Mage of the sample was 49 years (range = 23–77; see Table 1 for more demographic information). The bivariate analysis of survey variables with the interest outcome resulted in 10 variables being carried forward to the multiple logistic regression analysis (see Tables 3 and 4). Two variables were eliminated from an initial model of 12 due to issues of multicollinearity (age with years in practice) and small cell size (perception of neurofeedback). Of those 10 variables fit in the adjusted model, two were found to be clinically significant, as defined above, after evaluating the effect size, confidence intervals, and p value: type of practice setting and whether the psychotherapist thought neurofeedback would be welcome in their setting. Of the three primary variables initially selected in our study design (years in practice, cost as the main barrier to implementation, and type of practice setting) only type of practice setting was clinically significant.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Results for Interest Outcome

| Variable included in model | Interest in learning more about NFB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | ||

| LL | UL | |||

| Primary variables | ||||

| Years in practice | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | .0164 |

| Type of practice setting | ||||

| Community mental health clinic/agency | 1.77 | 0.994 | 3.15 | .0524a |

| Solo private practice | ||||

| Group private practice | 1.33 | 0.79 | 2.24 | .2782 |

| Other outpatient setting | 1.81 | 0.95 | 3.44 | .0708a |

| Cost as main barrier | ||||

| Cost | ||||

| Other main barrier | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.25 | .3462 |

| Secondary variables | ||||

| FIM score | 1.24 | 0.85 | 1.81 | .2595 |

| Tertiary variables | ||||

| Highest degree earned | ||||

| Masters | ||||

| Doctorate or Medical Doctor | 0.94 | 0.51 | 1.73 | .8316 |

| Number of clinicians in practice setting | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | .2089 |

| Average number of weekly therapy hours | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.03 | .1583 |

| Colleagues who practice NFB outside setting | ||||

| Yes | 1.23 | 0.78 | 1.92 | .3719 |

| No | ||||

| Whether NFB welcome in setting | ||||

| Yes | 3.38 | 2.18 | 5.26 | <.0001a |

| No/unsure | ||||

| Familiarity with NFB (presurvey) | ||||

| Not at all familiar | ||||

| Slightly/somewhat familiar | 1.60 | 0.90 | 2.83 | .1112 |

| Moderately/extremely familiar | 1.80 | 0.86 | 3.76 | .1205 |

Note. Reference variables are italicized. NFB = neurofeedback; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = lower limit; FIM = feasibility of intervention measure.

Clinical significance.

A significant association was found between the type of outpatient setting (solo private practice, group private practice, community mental health clinic/agency, and other outpatient setting) and providers’ interest in neurofeedback. Compared to those in solo practice, psychotherapists practicing in community mental health clinics/agencies (adjusted OR: 1.77, 95% CI [0.99, 3.15], p = .0524) and other outpatient settings (adjusted OR: 1.81, 95% CI [0.95, 3.44], p = .0708) had higher odds of being interested in neurofeedback.

Survey respondents were asked whether they believed neurofeedback would be welcome in their practice setting. Compared to those who did not believe that neurofeedback would be welcome in their practice setting or were unsure, those who believed neurofeedback would be welcome (adjusted OR: 3.38, 95% CI [2.18, 5.26], p < .0001) had much higher odds of being interested in implementing neurofeedback.

Discussion

This exploratory study sought to determine what factors are associated with outpatient psychotherapists’ interest in implementing neurofeedback. While the paucity of research prevents a comparison of other implementation research specific to neurofeedback, this study’s results align with results of other research using the CFIR within the mental health field. First, whether psychotherapists believed neurofeedback would be welcome in their practice setting had a very significant effect on their odds of being interested in the intervention. In a systematic review of the use of the CFIR model in alcohol and drug settings, Louie et al. (2021) found that both individual characteristics and organizational factors moderate the effectiveness of implementation. Strong organizational leadership and commitment to the intervention, perhaps similar to this study’s variable concerning whether neurofeedback would be welcome in the work setting, was found to be the most important factor for implementation of mental health peer support in a systematic review of peer support interventions guided by the CFIR (Mutschler et al., 2022).

The second significant finding of this study relates to the influence of practice setting on psychotherapists’ interest in implementing neurofeedback. Psychotherapists who practiced in community mental health clinics/agencies were significantly more likely to report being interested in neurofeedback. While this study did not explore why this may be the case, there are several noteworthy differences between private practice settings and community mental health agencies that could potentially contribute to this finding. First, most often community mental health agencies serve clientele that utilize government-funded insurance plans like Medicaid, while private practices generally take only cash-pay clients and/or clients with private insurance plans with higher reimbursement rates. Providers practicing in community mental health agencies often also have larger, more varied caseloads and a higher proportion of clients with more severe presenting problems and fewer resources to help them. Second, the difference in reimbursement rates between private practice and community mental health agencies usually contributes to a large revenue discrepancy between providers working in private practice and community mental health, with providers in private practice having the potential to make significantly more money (Frank et al., 2003; Watanabe-Galloway et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2023). On the other hand, individuals in private practice must pay for their own trainings, while some community mental health agencies provide funding for continuing education. Third, in most states under most psychotherapy licenses, there is a provisional licensure stage of 1–3 years during which new providers cannot bill private insurances but are allowed to bill government-funded insurance plans under the supervision of another provider. Thus, newer providers often start their careers in community mental health agencies. While this study did not find a significant correlation between years in practice and interest in neurofeedback, it is possible that the stage of providers’ careers could contribute to this practice setting finding.

Together, these two findings point to the significant influence that practice settings can have in the implementation of any intervention, including neurofeedback. Anecdotally, the most common efforts to increase the use and popularity of neurofeedback have been aimed at the individual practitioner level (i.e., recruitment of individual providers via individualized marketing strategies) and the outer setting level (i.e., calling for more research to gain status as an evidence-based practice or Food and Drug Administration clearance and attempts to encourage insurance companies to cover neurofeedback billing codes). These findings suggest that the neurofeedback field may need to also focus on what the CFIR model calls the “inner setting,” the settings in which individual practitioners will be implementing neurofeedback through strategies aimed at leaders within organizations or training whole groups of providers who work together in the same setting, as is often the case in larger group practices and community mental health agencies. Neurofeedback training programs could, for example, aim to provide group trainings where the training staff travels to the clinic or agency and provides training for the entire staff with training including the systemic aspects of implementation (such as billing, scheduling, and other logistic concerns).

Future research should focus on a closer examination of the contribution of practice setting to psychotherapists’ interest in neurofeedback. For example, future research could explore what is driving the effect of the type of practice setting on providers’ interest in implementation of neurofeedback. It is possible that factors such as client characteristics or needs, which were not accessed in this study but are included in the CFIR, may be playing a part in this association (Milgram et al., 2022; Rollins et al., 2024). Future research should also explore what factors contribute to whether providers perceive neurofeedback to be welcome in their workplace. A better understanding of contributing factors could inform inner and outer setting changes to affect the uptake of neurofeedback in mental health treatment. Following the structure provided by CFIR, these factors could include external policies and incentives, cosmopolitanism, structural characteristics of the practice setting, and implementation climate.

This study was not without its limitations. First, this study was limited by the use of a neurofeedback description embedded in the survey as a means to introduce neurofeedback to survey participants. Part of the problem that this study was seeking to better understand was the limited awareness of neurofeedback in the mental health field. Due to this fact, it could not be assumed that all licensed psychotherapists who participated in the survey were already familiar with neurofeedback. Thus, a brief overview of neurofeedback was required to ascertain participants’ perspectives on the intervention. Second, though written and approved by neurofeedback experts, the description of neurofeedback provided could have biased the data. For example, most of the neurofeedback providers who wrote the description specialize in working with individuals with trauma. The language and focal points of the description, then, could have skewed toward language more appealing to trauma therapists. The neurofeedback providers also generally all work under the same model of neurofeedback, whereas someone with different training may have described the interventions differently, which could have biased the data in different ways. This limitation highlights a significant area of difficulty in neurofeedback research more broadly. The term “neurofeedback” is a considerably large umbrella term for a plethora of approaches and models/frameworks to which neurofeedback practitioners ascribe. This variety both makes neurofeedback difficult to define with specificity and difficult to research as a broad concept. Third, as with any survey research, the study was limited by both the restricted number of questions (to minimize participant burden), and most of the questions having been written exclusively for this study since few validated measures were available that align with the purpose of this study. Some of the data gathered was ultimately excluded from the model due to small cell sizes, including the validated personality measure. Finally, the 500-participant sample resulted in a response rate of .007%. Due to the nature of the database created with the licensee lists, this number should be interpreted with caution partly because not everyone on the 72,443 provider list met the inclusion criteria for the study. Thus, the initial participant pool did not accurately represent the population being studied. For example, some of the states licensee lists included multiple types of mental health licenses, including some social workers who do not provide psychotherapy or other types of providers who are still on the lists but have retired or who are not working in an outpatient setting. We also closed the survey once the responses met the upper end of the goal determined by our power analysis (300–500) in order to begin data analysis.

Conclusion

The evidence supporting neurofeedback as a mental health treatment approach is growing, but adoption of neurofeedback in outpatient settings has been very slow. Understanding what factors impact practitioner’s interest in neurofeedback could help increase clinicians’ awareness of the intervention and its uptake and use in routine mental health care. This exploratory study utilized the CFIR domains as a foundation and found that the type of outpatient practice setting and beliefs about whether neurofeedback would be welcome in their setting significantly influenced psychotherapists’ self-reported interest in learning more about implementing neurofeedback. These findings point to a variety of opportunities for future research exploring neurofeedback’s application in outpatient mental health treatment from an implementation science lens. As the research base on the use of neurofeedback as a mental health intervention continues to grow, it is imperative for researchers to take advantage of the knowledge and insights provided by the field of implementation science to better understand factors that influence its uptake in outpatient mental health treatment.

Clinical Impact Statement.

This exploratory study utilized an implementation science framework and found that two main factors significantly influenced psychotherapists’ self-reported interest in learning more about implementing neurofeedback: type of outpatient practice setting and beliefs about whether neurofeedback would be welcome in their setting. These findings point to a variety of opportunities for future research exploring neurofeedback’s application and increased uptake in routine outpatient mental health treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no financial interest or conflicts of interest to report. Geoffrey M. Curran is supported by the Translational Research Institute, Grant UL1 TR003107, through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

Psychotherapist Survey

-

1Do you currently have an active psychotherapy license?

- No active license (ends survey)

- Yes (name of license type)

-

2Are you currently practicing in an outpatient setting?

- Yes

- No (ends survey)

-

3In which state are you licensed? If you are licensed in multiple states, please select the state in which you currently spend the majority of your time practicing.

- Full drop-down list of states

-

4

How old are you?

-

5What gender do you identify with?

- Female

- Male

- Nonbinary

- Other

-

6What is your race/ethnicity? Please check all that apply.

- Hispanic/Latino/Latina/Latinx

- Black/African American

- White

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Other

-

7What is your personal average yearly salary/income?

- Under $25,000

- $25,001–$50,000

- $50,001–$75,000

- $75,001–$100,000

- $100,001+

- Prefer not to answer

-

8What is your highest earned degree?

- Masters

- Doctorate (PhD, EdD, PsyD)

- MD

-

9

How many years have you been a practicing mental health provider?

-

10What population(s) do you work with in your practice?

- Kids

- Teens

- Adults

- Couples

- Families

-

11What area, if any, do you primarily specialize in treating?

- Addictions

- Trauma

- Couples/marital

- Family therapy

- Other: __________________

-

12In which type of setting do you currently practice?

- Community mental health clinic/agency

- Solo private practice

- Group private practice

- Other outpatient setting: __________

-

13

About how many licensed clinicians work in your current setting?

-

14

On average, how many hours of therapy do you provide per week?

-

15How are services paid for by your clients?

- Cash/private pay only

-

Cash/private pay and insuranceIf this option is chosen, have a slider option about percentage which are insurance—“What percentage of your sessions are paid for via insurance?”

- Insurance only

- Grant funding

- Other (describe): ______________

-

16Here are a number of personality traits that may or may not apply to you. Please choose a number after each statement to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with that statement. You should rate the extent to which the pair of traits applies to you, even if one characteristic applies more strongly than the other.

- I see myself as extraverted, enthusiastic

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as critical, quarrelsome

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as dependendable, self-disciplined

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as anxious, easily upset

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as open to new experiences, complex

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as reserved, quiet

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as sympathetic, warm

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as disorganized, careless

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as calm, emotionally stable

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

- I see myself as conventional, uncreative

- Disagree strongly

- Disagree moderately

- Disagree a little

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree a little

- Agree moderately

- Agree strongly

-

17Which of the following trainings have you completed? (Check all that apply)

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

- Brainspotting

- Somatic Experiencing (SE)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

- Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

- Prolonged Exposure (PE)

- Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT)

- Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

- Certified Sexual Addiction Therapist (CSAT)

- Certified Sex Therapist (AASECT)

- Internal Family Systems (IFS)

- Play Therapy

- Gottman Certification

- Hypnosis

Survey Part B—Intervention

-

18Before hearing about this study, how would you describe your familiarity with neurofeedback as a mental health intervention?

- Not at all familiar

- Slightly familiar

- Somewhat familiar

- Moderately familiar

- Extremely familiar

-

19What is your perception of neurofeedback based on what know?

- N/A—I’m not familiar with neurofeedback

- Very negative

- Somewhat negative

- Neither positive nor negative

- Somewhat positive

- Very positive

-

20(Skip if N/A on 27) Have you ever considered completing the training?

- Yes

- No

- (If yes) Have you completed the training?

- Yes

- No

- (If yes) Do you currently use neurofeedback in your practice?

- Yes

- No

- (If yes) Would you be interested in participating in a one-on-one interview via Zoom regarding your experience of implementing neurofeedback?

- Yes

- Email: _______________

- No

-

21Does anyone within your work setting practice neurofeedback?

- Yes

- No

-

22Does anyone you know outside of your workplace practice neurofeedback?

- Yes

- No

Instructions: We want to learn more about your experience with and impressions of an intervention that you may or may not be familiar with known as neurofeedback (also sometimes called “EEG biofeedback”). Please read the description of neurofeedback provided below.

What Is Neurofeedback?

Neurofeedback, also called EEG Biofeedback, is a learning technology that enables a person to alter their brain waves. With neurofeedback we can learn to shift our underlying neuronal patterns and, through this internal change, experience a fundamental shift into a healthier way of being in the world. This is done by giving our brain direct feedback about its functioning and, through this feedback, teach our brain and nervous system to work in a more regulated and less reactive, fear-driven way. When information about a person’s own brain wave characteristics are made available to them, the individual can learn to change them. Once the brain has learned to function in a more coherent, organized, and optimal way, we can see not only improved emotion regulation but also greater mental clarity, concentration, focus, sleep, relational connection, and overall emotional and physical well-being.

What Is It Used for?

Neurofeedback is used for many conditions and disabilities in which the brain and nervous system are not organizing or, more specifically, are not self-regulating well. These include ADHD and more severe conduct problems, specific learning disabilities, sleep problems, and chronic pain problems including migraine. The training is also helpful with the symptoms of mood disorders such as anxiety and depression, as well as for more severe conditions such as PTSD, developmental trauma, uncontrolled seizures, minor traumatic brain injury, stroke, or cerebral palsy.

How Is It Done?

Before neurofeedback training begins, the therapist will ask the client for a thorough description of their symptoms, health history, and family history in order to determine the best training approach. In most instances, clients will train at least once a week (twice per week is generally considered ideal). Training sessions may be anywhere from 15 to 45 min in duration with anywhere from 3 to 30 min of time engaged in the actual training. It is not unusual to see improvement within the first 10 sessions. Neurofeedback is a learning process. Once this learning is consolidated, its benefits are generally long-lasting and enduring.

Neurofeedback training is a painless, noninvasive procedure. One or more sensors are placed on the scalp and one to the ear using a salt-based conductive paste. The brain waves are monitored by an amplifier and a computer software that processes the signal and provides the proper feedback. This feedback is displayed to the client by means of a video game or other video display, along with audio signals. The client is asked to play the video game solely with their brain. Neurofeedback doesn’t require conscious effort because the brain recognizes the feedback patterns, via the auditory and visual feedback cues of the game, faster and more accurately than the conscious, thinking brain can. The practitioner sets goals using the computer software to increase the presence of some frequencies and suppress the presence of others based on the symptoms and goals of the client. Gradually, the brain responds to the cues that it is being given and learns new brain wave patterns. We assess progress through changes in symptoms and other behaviors. The choice of which training approaches are appropriate for a particular individual depends on a professional assessment of symptoms. Neurofeedback training should only take place under the supervision of a properly BCIA-trained and mentored professional.

Therapeutic Applications

A growing number of studies and clinical reports have shown that neurofeedback training may be helpful in alleviating the symptoms associated with a wide range of cognitive disorders, brain injuries, and negative affective states.

Conditions for which studies and/or published clinical data indicate the efficacy or possible efficacy of neurofeedback:

ADD/ADHD

Anxiety disorders

Attachment disorders

Autistic spectrum disorders

Developmental trauma

Depression

Dyslexia

Learning disorders

Migraine

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

PTSD

Seizure disorders

Substance abuse

Sleep problems

Stroke

Traumatic brain injury

Neurofeedback has also been shown to be an effective tool for:

Memory enhancement

Peak performance

Stress reduction

Conditions for which the use of neurofeedback appears to be promising and further study is indicated:

Borderline personality disorder

Conduct disorders

Pre-menstrual syndrome

Sleep disorders

Tourette’s syndrome

-

23If you had heard of neurofeedback before this study, does this description match what you have heard about it previously?

- Yes

- No

- Somewhat

- I had never heard of neurofeedback before this study.

Instructions: Next, we would like to ask you some questions about your impression of neurofeedback based on what you just read. We understand that you may not know enough about neurofeedback to form a full opinion on how you might feel about implementing it into your practice. We are only looking for your general impression.

-

24Do you think an intervention like neurofeedback would be welcome in your current work setting?

- Yes

- No

- Unsure

-

25Please select the option below each statement that best reflects your agreement with each statement.

- Neurofeedback seems implementable.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback seems possible.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback seems doable.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback seems easy to use.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

-

26Please select the option below each statement that best reflects your agreement with each statement.

- Neurofeedback seems fitting for the clients I work with.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback seems suitable for my practice/clients.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback seems applicable to the work that I do with clients.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback seems like a good match for my practice/clients.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

-

27Please select the option below each statement that best reflects your agreement with each statement.

- Neurofeedback meets my approval.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- Neurofeedback is appealing to me.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- I like neurofeedback.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

- I welcome neurofeedback.

- Completely disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Agree

- Completely agree

-

28Rate each of the following statements according to how they would affect whether you might choose to use neurofeedback in your practice.

- Neurofeedback costs approximately $7,800 in training and equipment costs.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Basic neurofeedback training can be completed online.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Neurofeedback’s basic training takes approximately 50 hr.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Some neurofeedback practitioners have found that the treatment process is faster when they utilize neurofeedback with their clients.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Neurofeedback practitioners claim that neurofeedback helps between 85% and 90% of clients/patients.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Neurofeedback is not covered by your client’s insurance providers.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Neurofeedback has been found to help people who struggle with self-regulation.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Continued one-on-one and group mentoring post-training is encouraged by neurofeedback experts.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Neurofeedback has been found to have longer-term effects, as opposed to medication.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- A deep understanding of neurofeedback requires some knowledge of neuroscience/requires knowledge outside of regular counselor training.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

- Neurofeedback practitioners claim that neurofeedback helps between 85% and 90% of clients/patients.

- +2 strongly encourage

- +1 somewhat encourage

- 0 neutral/no impact

- −1 somewhat discourage

- −2 strongly discourage

-

29

Which of the following factors would you consider to be the biggest barrier to implementing neurofeedback into your practice?

Single choice checkbox- Neurofeedback’s basic training takes approximately 50 hr.

- Neurofeedback not being covered by your client’s insurance providers.

- Continued one-on-one and group mentoring post-training is encouraged by neurofeedback experts.

- Neurofeedback costs approximately $7,800 in training and equipment costs.

- A deep understanding of neurofeedback requires some knowledge of neuroscience/requires knowledge outside of regular counselor training.

-

30

Which of the following factors would you consider to be the biggest facilitator/encouraging factor to implementing neurofeedback into your practice?

Single choice checkbox- Basic neurofeedback training can be completed online.

- Some neurofeedback practitioners have found that the treatment process is faster when they utilize neurofeedback with their clients.

- Neurofeedback has been found to have longer-term effects, as opposed to medication.

- Neurofeedback has been found to help people who struggle with self-regulation.

- Neurofeedback practitioners claim that neurofeedback helps between 85% and 90% of clients/patients.

-

31Are you interested in learning more about implementing neurofeedback into your practice? Note: Your individual response to this question is confidential. No personal information will be shared based on any answers you provide in this survey.

- Yes

- No

-

32

On a scale of 1–10 (1 = low, 10 = high), how would you rate how likely you are to implement neurofeedback into your practice in the future?

Single choice dropdown list of 1–10.

References

- Amrhein V, Greenland S, & McShane B (2019). Retire statistical significance. Nature, 567(7748), 305–307. 10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch Y, & Holtom BC (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8), 1139–1160. 10.1177/0018726708094863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, & Kirchner JA (2020). Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Research, 283, Article 112376. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenholtz S, & Pronovost PJ (2003). Barriers to translating evidence into practice. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 9(4), 321–325. 10.1097/00075198-200308000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), Article 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, & Mittman BS (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), Article 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etikan I (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SF, Lanius RA, & Frewen PA (2016). EEG neurofeedback as adjunct to psychotherapy for complex developmental trauma-related disorders: Case study and treatment rationale. Traumatology, 22(4), 255–260. 10.1037/trm0000073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, Goldman HH, & Hogan M (2003). Medicaid and mental health: Be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs, 22(1), 101–113. 10.1377/hlthaff.22.1.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, & Sturdivant RX (2013). Applied logistic regression (3rd ed.). Wiley. 10.1002/9781118548387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Neuroregulation and Research. (2021, March). Definitions and descriptions for the consumer. https://isnr.org/what-is-neurofeedback

- Jepson C, Asch DA, Hershey JC, & Ubel PA (2005). In a mailed physician survey, questionnaire length had a threshold effect on response rate. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58(1), 103–105. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettlewell PW (2004). Development, dissemination, and implementation of evidence-based treatments: Commentary. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(2), 190–195. 10.1093/clipsy.bph071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova E, Veilahti AVP, Akhundzadeh R, Radev S, Konicar L, & Cowley BU (2023). Evaluation of neurofeedback learning in patients with ADHD: A systematic review. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 48, 11–25. 10.1007/s10484-022-09562-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson JE, Ryan CB, & Baerentzen MB (2010). Practitioner perspectives of neurofeedback therapy for mental health and physiological disorders. Journal of Neurotherapy, 14(4), 280–290. 10.1080/10874208.2010.523334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Walter SD, & Thabane L (2021). Shifting the focus away from binary thinking of statistical significance and towards education for key stakeholders: Revisiting the debate on whether it’s time to de-emphasize or get rid of statistical significance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 137, 104–112. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie E, Barrett EL, Baillie A, Haber P, & Morley KC (2021). A systematic review of evidence-based practice implementation in drug and alcohol settings: Applying the consolidated framework for implementation research framework. Implementation Science, 16(1), Article 22. 10.1186/s13012-021-01090-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Jeunet C, Pelissolo A, & Ros T (2021). EEG neurofeedback for anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorders: A blueprint for a promising brain-based therapy. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(12), Article 84. 10.1007/s11920-021-01299-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram L, Freeman JB, Benito KG, Elwy AR, & Frank HE (2022). Clinician-reported determinants of evidence-based practice use in private practice mental health. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 52(4), 337–346. 10.1007/s10879-022-09551-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutschler C, Bellamy C, Davidson L, Lichtenstein S, & Kidd S (2022). Implementation of peer support in mental health services: A systematic review of the literature. Psychological Services, 19(2), 360–374. 10.1037/ser0000531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AA, Ros T, Densmore M, Frewen PA, Neufeld RWJ, Théberge J, Jetly R, & Lanius RA (2020). A randomized, controlled trial of alpha-rhythm EEG neurofeedback in posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary investigation showing evidence of decreased PTSD symptoms and restored default mode and salience network connectivity using fMRI. NeuroImage: Clinical, 28, Article 102490. 10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott HE, Cannon R, & Trullinger M (2021). The fallacy of sham-controlled neurofeedback trials: A reply to Thibault and Colleagues (2018). Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(3), 448–457. 10.1177/1087054718790802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purper-Ouakil D, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Ros T, Acquaviva E, Banaschewski T, Baumeister S, Bousquet E, Bussalb A, Delhaye M, Delorme R, Drechsler R, Goujon A, Hage A, Kaiser A, Mayaud L, Mechler K, Menache C, Revol O, Tagwerker F, … Brandeis D (2022). Personalized at-home neurofeedback compared to long-acting methylphenidate in children with ADHD: NEWROFEED, a European randomized noninferiority trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(2), 187–198. 10.1111/jcpp.13462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesco-Matías P, Yela-Bernabé JR, Crego A, & Sánchez-Zaballos E (2021). What do meta-analyses have to say about the efficacy of neurofeedback applied to children with ADHD? Review of previous meta-analyses and a new meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(4), 473–485. 10.1177/1087054718821731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J (2008). A symphony in the brain: The evolution of the new brain wave biofeedback. Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins AL, Eliacin J, Kukla M, Wasmuth S, Salyers MP, & McGuire AB (2024). Implementation of integrated dual disorder treatment in routine veterans health administration settings. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22, 578–598. 10.1007/s11469-022-00891-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Story DA, & Tait AR (2019). Survey research. Anesthesiology, 130(2), 192–202. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault RT, Veissière S, Olson JA, & Raz A (2021). EEG-neurofeedback and the correction of misleading information: A reply to Pigott and Colleagues. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(3), 458–459. 10.1177/1087054718808379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocki KF (2006). Is there an anti-neurofeedback conspiracy? Journal of Addictions Nursing, 17(4), 199–202. 10.1080/10884600600995176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Hodgdon H, Gapen M, Musicaro R, Suvak MK, Hamlin E, & Spinazzola J (2016). A randomized controlled study of neurofeedback for chronic PTSD. PLOS ONE, 11(12), Article e0166752. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe-Galloway S, Madison L, Watkins KL, Nguyen AT, & Chen LW (2015). Recruitment and retention of mental health care providers in rural Nebraska: Perceptions of providers and administrators. Rural and Remote Health, 15(4), Article 3392. 10.22605/RRH3392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, & Wickramaratne P (2006). National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(8), 925–934. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JM, Renfro S, Watson K, Deshmukh A, & McConnell KJ (2023). Medicaid reimbursement for psychiatric services: Comparisons across states and with medicare. Health Affairs, 42(4), 556–565. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]