Abstract

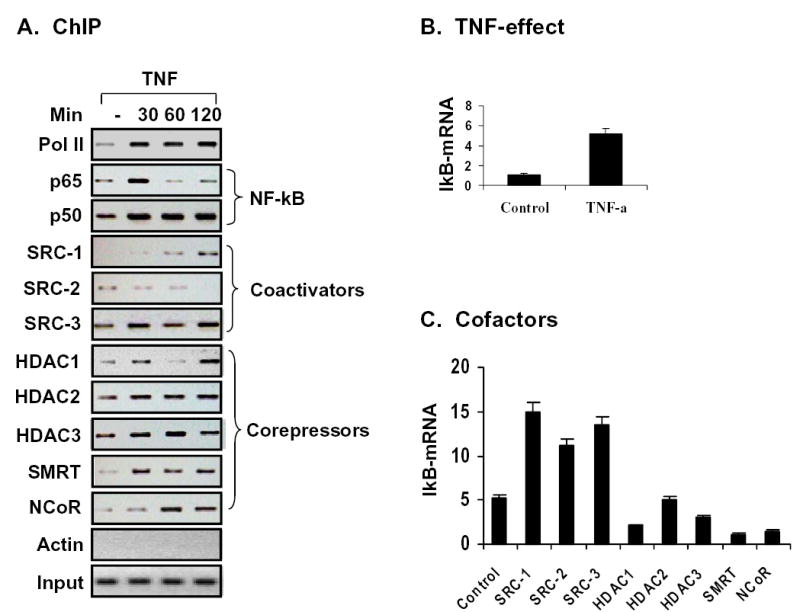

In this study, we investigated recruitment of coactivators (SRC-1, SRC-2 and SRC-3) and corepressors (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, SMRT and NCoR) to the IkBα gene promoter after NF-kB activation by TNF-α. Our data from ChIP assay suggest that coactivators and corepressors are simultaneously recruited to the promoter, and their binding to the promoter DNA is oscillated in HEK293 cells. SRC-1, SRC-2 and SRC-3 all enhanced IkBα transcription. However, the interaction of each coactivator with the promoter exhibited different patterns. After TNF-α treatment, SRC-1 signal was increased gradually, but SRC-2 signal was reduced immediately, suggesting replacement of SRC-2 by SRC-1. SRC-3 signal was increased at 30 minutes, reduced at 60 minutes, and then increased again at 120 minutes, suggesting an oscillation of SRC-3. The corepressors were recruited to the promoter together with the coactivators. The binding pattern suggests that the corepressor proteins formed two types of corepressor complexes, SMRT/HDAC1 and NCoR/HDAC3. The two complexes exhibited a switch at 30 and 60 minutes. The functions of corepressor proteins were confirmed by gene overexpression and RNAi-mediated gene knockdown. These data suggest that gene transactivation by the transcription factor NF-kB is subject to the regulation of a dynamic balance between the coactivators and corepressors. This model may represent a mechanism for integration of extracellular signals into a precise control of gene transcription.

Transcriptional activity of NF-kB is regulated by transcription coactivators and corepressors, which are originally identified for nuclear receptors. The coactivators of NF-kB include P300/CBP, p/CAF, and p160 proteins (SRC-1, SRC-2 and SRC-3) (1–8). CBP/p300 and the p160 proteins both possess intrinsic histone acetylase (HAT) activity, which is necessary to open the chromatin structure through an acetylation-induced conformation change in histone protein. However, the function of p160 protein is dependent upon CBP/p300 as p160 protein exhibits much less activity in the absence of CBP/p300 (9).

The most common active form of NF-kB is a heterodimer of two subunits, p65 (RelA) and p50 (NF-kB1). The subunit p65 contains an activation domain that binds to the coactivators for transcription initiation. The subunit p50 does not have an activation domain, but p50 can activate gene transcription through BCL3. The two subunits exhibit a different preference for p300/CBP and p/CAF. p300/CBP is required for p65-mediated transactivation and p/CAF is involved in transactivation by NF-kB p50 (2). Interaction of p65 with p300/CBP requires p65 S276 phosphorylation (10), and S276 mutation inhibits p65 function (11). All of the three p160 proteins have been reported to participate in the transcriptional activation mediated by NF-kB, however, the relative importance of each isoform in NF-kB mediated gene transcription remains to be investigated. Recent studies suggest that the function of a coactivator is not universal. It is determined by at least two factors: transcription factors and the promoter context. A coactivator may act as a corepressor in certain gene environments (12), and a corepressor (N-CoR) has been reported to act as a coactivator in the regulation of gene transcription (13). To understand the relative importance of p160 proteins, we investigated the time course of p160 interaction with IkBα promoter using ChIP assay. The data suggests that after NF-kB activation by TNF-α, SRC-1 and SRC-2 exhibit an opposite patterns of association with IkBα promoter. The SRC-3 is different from SRC-1 and 2 in that it exhibits an unique oscillation in association with the IkBα gene promoter.

The components of corepressor complex for NF-kB include SMRT, NCoR, HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3 (14–19). In these corepressor proteins, SMRT and NCoR do not have an enzymatic activity, but they can trigger the catalytic activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) for deacetylation of histone proteins (20). Although intracellular distribution of SMRT and NCoR are regulated by different signaling pathways (21), these two proteins are interchangeable in the inhibition of NF-kB activity. HDAC1–3 belongs to the class I histone deacetylases that includes HDAC1, 2, 3, 8, and 11 (22). The class II histone deacetylases include HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10. The catalytic activity of HDACs is required for deacetylation of histones and transcription factors in the regulation of transcription. HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 all have been reported to inhibit NF-kB; however, their roles in the regulation of NF-kB activity are highly controversial. HDAC1 and HDAC3 were shown to be involved in the inhibition of NF-kB activity (14,18,19,23–26), but the relationship of the two deacetylases remains to be determined. We have investigated this issue using ChIP assays and evaluated their functions in the IkBα gene promoter. Our data suggests that HDAC1 and HDAC3 both are recruited to the IkBα promoter after NF-kB activation, but they can substitute for each other in a time-dependent manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and reagents

HEK293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were maintained in the DMEM culture medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum. Antibodies to IkBα (sc-371), p65 (sc-8008), p50 (sc-8414), SRC1 (sc-8995), SRC3 (sc-9119), SMRT (sc-1610), NCoR (sc-8994) and Pol II (sc-9001) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). β-actin (ab6276), HDAC2 (ab1770) and HDAC3 (ab2379) antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). HDAC1 antibody (H 6287) was from Sigma. SRC2 antibody (06-986) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). The SRC-1 and SRC-3 expression vectors were kindly provided by Dr. Bert W O'Malley at the Baylor College of Medicine. The SRC-2 (GRIP-1) vector was a gift from Dr. Michael R Stallcup (University of Southern California). SMRT and NCoR together with their RNAi expression vectors were used as previously reported (27). HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3 together with their RNAi expression vectors have been described elsewhere (28).

Western Blotting (29)

Cells were treated with 20 ng/ml TNF-α after serum-starvation in 0.5% BSA-containing cell culture medium. Whole cell lysate protein was made in lysis buffer (1% triton X-100, 50 mM KCI, 25 mM hepes ph7.8, leupeptin 10 μg/ml, aprotinin 20 μg/ml, 125 μM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) via sonication. The protein (100 μg) was boiled for three minutes, resolved in 6% mini-SDS PAGE for 90 minutes at 100 volt, and blotted on the PVDF membrane (162-0184, Bio-Rad). After being pre-blotted in milk buffer for 20 minutes, the membrane was blotted with the first antibody for 1–24 hours and the secondary antibody for 30 minutes. The HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (NA934V or NA931, Amersham Life Science) were used with chemiluminescence reagent (NEL-105, PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) for generation of the light signal. To detect multiple signals from one membrane, the membrane was treated with a stripping buffer (59mM Tri-HCI, 2% SDS, 0.75% 2-ME) for 20 minutes at 37 ° C after each cycle of blotting to remove the bound antibody. All the experiments were conducted for three or more times. Intensity of the immunoblot signal was quantified using a computer program, PDQuest 7.1 (Bio-Rad).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP)

HEK293 cells were cultured in 100 mm cell culture plate and treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) after serum-starvation overnight. The cells were treated with formaldehyde and collected after TNF-treatment. The ChIP assay was used to monitor the NF-kB induced recruitment of coactivators and corepressors in the human IkBα gene promoter in HEK293 cells. The protocol was developed from a published study (30). The IkBα primers were designed to cover the NF-kB binding site (-316/-15) in the human IkBα gene promoter (31): forward 5'-GGACCCCAAACCAAAATCG-3'; reverse 5'-TCAGGCGCGGGGAATTTCC-3'. The major steps in the ChIP assay are to crosslink the target protein to the chromatin DNA with formaldehyde, break the chromatin DNA into fragments 400-1200bp in length, immunoprecipitate (IP) the protein-DNA complex with an antibody that recognizes the target protein. IgG was used in IP as a control for non-specific signal. The DNA in IP product was amplified in PCR with the ChIP assay primers that are specific to the NF-kB binding site at -316/-15. Beta-actin was used as a negative control for NF-kB target gene. The ChIP primers are (F) 5' TGCACTGTGCGGCGAAGC 3', and (R) 5' TCGAGCCATAAAAGGCAA 3' that amplify -980/-915 in the human actin gene promoter. The image of PCR product is presented in revered black/white in which DNA band is in black. The PCR products were quantitated based on signal intensity.

Transfection assay

Transient transfection was conducted in triplicate in 24-well plate. Cells (5 X 104/well) were plated for sixteen hours and transfected with plasmid DNA utilizing Lipofectamine2000. In the transient transfection, IkBα luciferase reporter plasmid DNA (0.2 μg) is used in each point unless indicated in the figure legend. In cotransfection, an empty control vector is used in the control to keep total plasmid DNA at the same amount in each point. For TNF-treatment, the cells were kept in serum-free medium for 16 hours, and treated with TNF-α for 5 hours before reporter assay. The NF-kB luciferase reporter vector that contains 5 kB response elements was obtained from Stratagene (Cat# 219077, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The IkBα luciferase reporter contains the mouse IkBα promoter (-1 kb) in which four NF-kB binding sites have been identified. In all of the transient transfection, the internal control reporter is 0.1 μg/well of SV40-renilla luciferase reporter plasmid, and the total DNA concentration was equalized in each well with a control plasmid. The luciferase assay was conducted using a 96-well luminometer with the dual luciferase substrate system (Promega). The luciferase activity was normalized with the internal control Renilla luciferase, and a mean value together with a standard error of the triplicate samples was used to determine the reporter activity. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Real time RT-PCR

293 cells were transiently transfected with the cofactors in a 24- well place. After 48 hours, the cells were treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 30 minutes, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol protocol. The real time RT-PCR reaction was conducted in triplicates using Taqman IkBα probe (Hs00153283_m1, Applied Biosynthesis). The mean value of the triplicates was used to indicate mRNA level of IkBα.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was conducted three times at least with consistent result. The representative gel or blot from each experiment is presented in this manuscript. In reporter assay, a mean value and standard deviation of the triplicates is used to represent the reporter activity. The data was analyzed using student’s T-test with significance p< 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SRC-1 is a coactivator for NF-kB in IkBα promoter

SRC-1 was the first 160 kDa nuclear receptor coactivator identified and is also known as nuclear coactivator 1 (NCoA-1) (32). Although SRC-1 has histone acetylase (HAT) activity, its function is dependent on CBP (33,34). SRC-1 facilitates transactivation by many nuclear receptors including the progesterone receptor (PGR), estrogen receptor (ER) glucocorticoid receptor (GR), thyroid hormone receptor (TR), and retinoid X receptor (RXRa) (33). SRC-1 also participates in transactivation by the convention transcription factors including NF-kB (1,5), SP1, the chimeric Gal4-VP16 protein, and STAT5a (35,36).

To evaluate the coactivator function of SRC-1 in NF-kB-mediated IkBα transcription, SRC-1 was investigated using ChIP assay. In this study, NF-kB is activated by TNF-α in HEK293 cells. Recruitment of SRC-1 was monitored during a time frame of 30–120 minutes after addition of TNF-α (Fig. 1A). Association of SRC-1 with the IkBα gene promoter was increased gradually. The increase is associated with DNA binding of NF-kB, and presence of RNA polymerase II (Pol II), an indicator of transcriptional initiation. p65/DNA interaction is increased at 30 minutes, reduced at 60 minutes and then increased again at 120 minutes during TNF-treatment. This may reflect the asynchronous oscillations of p65 following TNF-stimulation as reported recently (37). These data suggest that SRC-1 is recruited for gene transcription mediated by NF-kB.

Fig 1. Interaction of SRC-1 with NF-kB.

(A) ChIP assay for SRC-1/NF-kB association. The signals for p65, p50 and Pol II indicate that NF-kB was activated and mRNA synthesis was initiated. Actin signal is a control of DNA input. (B) Cotransfection of SRC-1 with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 and p50 expression vectors, which were used at 0.1 μg/point for each plasmid DNA. (C) Immunoblotting of IkBα protein in HEK293 cells transfected by SRC-1. SRC-1 expression is confirmed in the transfected cells. Actin protein is a control for protein loading. (D) Cotransfection of SRC-1 with NF-kB luciferase reporter. The same condition was used as described in the legend for panel 2 except the reporter DNA.

SRC-1 function was examined using the IkBα-Luciferase report in transient transfection of HEK293 cells. Cotransfection of SRC-1 led to a significant increase in the IkBα reporter activity (Fig. 1B). Consistently, the protein abundance of endogenous IkBα was also doubled in this condition (Fig. 1C). The increase in IkBα protein and SRC-1 protein was determined in the transfected cells by Western blot. In a similar assay, NF-kB luciferase reporter was also enhanced by SRC-1 (Fig. 1D), suggesting that SRC-1 can serve as a coactivator for NF-kB regardless of promoter context.

SRC-2 is replaced by SRC-1after NF-kB activation by TNF-α

SRC-2 is also known as GRIP-1 (glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein-1) (38) and TIF2 (transcriptional intermediary factor 2) (39). SRC-2 has been shown to be a coactivator for both class I (GR, ER, AR, MR, PR) and class II nuclear receptors (TRα, VDR, RARα, RXRα) (38). It shares high sequence homolog with SRC-1 (N-CoA1), and is also known as N-CoA2 (nuclear coactivator 2). SRC-2 is distributed in both cytoplasm and nucleus (40), and the distribution is regulated by cell differentiation. SRC-2 was reported as a coactivator of NF-kB (1).

Association of SRC-2 with the IkBα gene promoter was detectable in the absence of TNF-α treatment (Fig. 2A). It was reduced gradually in 293 cells after TNF-treatment. This reduction is corresponding to an increase in SRC-1 signal, suggesting that SRC-2 is substituted by SRC-1 in the IkBα promoter after NF-kB activation. By examining intracellular distribution of SRC-2, we observed that SRC-2 protein was decreased in the nucleus, but increased in the cytoplasm during TNF-treatment (Fig. 2B). This suggests that replacement of SRC-2 by SRC-1 might be a result of loss of SRC-2 in the nucleus. It is not clear why such a nuclear exclusion is induced by TNF-α. The exclusion might be related to phosphorylation of SRC-2 as what was observed in SRC-1 (41). SRC-1 was shown to be phosphorylated by ERK. Since TNF-α induces activation of ERK, and SRC-2 shares high level of homologue with SRC-1, it is likely that the nuclear exclusion of SRC-2 is related to ERK activation by TNF-α.

Fig 2. Substitution of SRC-2 by SRC-1.

(A) ChIP assay for SRC-2/NF-kB association. This result was obtained in the same condition as for ChIP assay of SRC-1. The signals for p65, p50 and Pol II is presented in Fig. 1A. (B) Nuclear exclusion of SRC-2. The cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted from HEK293 cells after TNF-treatment. SRC-2 protein was quantified in the extracts by immunoblotting. Actin and SP1 protein signals are used as controls for protein loading of the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, respectively. (C) Cotransfection of SRC-2 with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 expression vectors at 0.1 μg/point. (D) Immunoblotting of IkBα protein in HEK293 cells transfected. SRC-2 protein level is confirmed in cells transfected for overexpression or knockdown.

The function of SRC-2 was examined using the IkBα reporter in a transient transfection. Overexpression of SRC-2 resulted in an increase in the reporter activity (Fig. 2C) and this was associated with an increase in IkBα protein. While knockdown of SRC-2 led to a decrease in IkBα protein (Fig. 2D). These results support that SRC-2 acts as a coactivator of NF-kB, and its major function might be related to the maintenance of basal level expression of IkBα. In the presence of TNF-α, SRC-1 replaces SRC-2 in the IkBα promoter for a robust transcriptional activation induced by NF-kB activation.

SRC-3 exhibits oscillation in interaction with IkBα promoter

SRC-3 was cloned independently by several labs in 1997 under different names including p/CIP (p300/CBP/co-integrator-associated protein) (35), ACTR (42), AIB-1 (a gene amplified in breast cancer-1) (43), RAC-3 (receptor-associated coactivator 3) (44), TRAM-1 (a thyroid hormone receptor activator molecule-1) (45). p/CIP is the mouse homolog of the human SRC-3 (46). SRC-3 shares 31% and 36% amino acid identity with SRC-1 and SRC-2, respectively (35). SRC-3 recruits CBP and P/CAF for generation of the transcription initiation complex (35,42). Intracellular distribution of SRC-3 is regulated by extracellular signals including insulin (47) and TNF-α (7). In serum free medium, SRC-3 is predominantly in the cytoplasm while insulin or TNF-α results in SRC-3 nuclear translocation. SRC-3 was reported as a coactivator of NF-kB (7,8). More interestingly, SRC-3 is associated with IKK, and is subject to phosphorylation by IKK (7).

SRC-3 was examined in the same experimental conditions that were used for SRC-1. Interestingly, the pattern of SRC-3 signal is different from that of either SRC-1 or SRC-2 in ChIP assay. SRC-3 recruitment was induced by TNF-α at 30 minutes (Fig. 3A). However, the association was reduced at 60 minutes and followed by another increase at 120 minutes. It is not clear why the SRC-3 signal follows this pattern of oscillation. Since this pattern of oscillation was observed in p65, the data suggests that SRC-3 may directly interact with p65. Therefore, its recruitment is strictly dependent on the presence of p65 in the promoter. It is also possible that SRC-3 may have a different function from SRC-1. It remains to be examined if a nuclear exclusion contributes to the oscillation.

Fig 3. Oscillation of SRC-3.

(A) ChIP assay for SRC-3/NF-kB association. This result was obtained in the same condition as for ChIP assay of SRC-1. The signals for p65 and p50 demonstrates activation of NF-kB by TNF-α. (B) Cotransfection of SRC-3 with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 expression vector at 0.1 μg/point. The SRC-3 DNA (μg) is indicated. (C) Knockdown of SRC-3 by vector-based RNAi expression. The DNA (μg) of SRC-3 RNAi vector is indicated. (D) Immunoblotting of IkBα protein in HEK293 cells transfected. SRC-3 protein level is confirmed in cells transfected for knockdown.

Functional analysis suggests that SRC-3 enhances NF-kB-mediated IkBα transcription. SRC-3 overexpression enhanced the IkB reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B), while knockdown of SRC-3 decreased the IkBα reporter activity (Fig. 3C). The reporter activity is consistent with the IkBα protein levels under these conditions (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that although SRC-3 signal exhibits a different pattern from SRC-1 in ChIP assay, SRC-3 still serves as a coactivator for NF-kB in the IkBα gene promoter. It remains to be investigated how SRC-3 acts in the formation of transcription initiation complex for NF-kB.

HDAC1is a corepressor for NF-kB

HDAC1 was reported in many studies as a corepressor protein for NF-kB (14,23–26). To evaluate HDAC1 activity, HDAC1 recruitment was investigated using ChIP assay, and the HDAC1 function was determined in the reporter assay. Overexpression and RNAi-mediated knockdown was applied to HDAC1. HDAC1 signal was induced by TNF-α as revealed in ChIP assay (Fig. 4A). The increase was observed at 30 minutes, then reduced at 60 minutes and increased again at 120 minutes after TNF-treatment. This pattern of oscillation is similar to that observed with p65 and SRC-3 (Fig. 3A). However, the biological significance of such an oscillation is not clear. It is quit possible that HDAC1 also directly binds to p65 in NF-kB protein. It remains to be tested if HDAC1 and SRC-3 have a physical interaction in this condition since they exhibit a similar oscillation pattern. Recruitment of histone deacetylase usually leads to inhibition of gene transcription, this on/off pattern may also represent a competition for NF-kB between coactivator and corepressor. This data suggests that corepressors constantly compete with coactivators even when the transcription has been initiated. Such an action of corepressor may be necessary for the precise control of gene transcription. Once the corepressor becomes dominant in the promoter region, the transcription will stop.

Fig 4. Inhibition of NF-kB by HDAC1.

(A) ChIP assay for HDAC1/NF-kB association. This result was obtained in the same condition as for ChIP assay of SRC-1. (B) Cotransfection of HDAC1 with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 expression vector at 0.1 μg/point. The HDAC1 DNA (μg) is indicated. (C) Knockdown of HDAC1 by vector-based RNAi expression. The DNA (μg) of HDAC1 RNAi (1RNAi) vector is indicated. (D) Immunoblotting of IkBα protein in HEK293 cells transfected. HDAC1 protein level is confirmed in cells transfected for overexpression knockdown.

The repressor activity of HDAC1 was confirmed with the IkBα reporter. Overexpression of HDAC1 led to reduction of the reporter activity (Fig. 4B). This was companied by a reduction in the IkBα protein (Fig. 4D). Knockdown of HDAC1 resulted in an enhancement in IkBα promoter activity (Fig. 4C), and protein expression (Fig. 4D). Since inhibitory activity is detectable upon HDAC1 overexpression, this may explain why HDAC1 was consistently reported as a corepressor for NF-kB (14,23–26). Unlike HDAC1, the role of HDAC2 or HDAC3 is highly controversial in the regulation of NF-kB. Our data supports the model that HDAC1 inhibits transcriptional activity of NF-kB through deacetylation of histone protein.

HDAC2 is not a corepressor for NF-kB in the IkBα promoter

HDAC2 was reported to mediate glucocorticoid inhibition of p65-mediated transactivation (16,17) or inhibit NF-kB p65-induced IL-8 transcription through association with HDAC1 (23). In this study, HDAC2/NF-kB interaction was investigated under the same condition as being used for HDAC1. The HDAC2 signal was induced by TNF-α in ChIP assay (Fig. 5A). However, the induction was not as strong as for HDAC1. Modification of HDAC2 function by overexpression or knockdown failed to generate a significant impact on the IkBα reporter and protein activities (Fig. 5, B, C and D). These data suggest that HDAC2 may not be involved in the regulation of NF-kB activity in the IkBα gene. This conclusion is supported by observations from other labs that although HDAC2 associates with p65 upon immunoprecipitation (19,23,48), HDAC2 does not exhibit catalytic activity (19).

Fig 5. HDAC2/NF-kB interaction.

(A) ChIP assay for HDAC2/NF-kB association. This result was obtained in the same condition as for ChIP assay of SRC-1. (B) Cotransfection of HDAC2 with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 expression vector, which was used at 0.1 μg/point. The HDAC2 DNA (μg) is indicated. (C) Knockdown of HDAC2 by vector-based RNAi expression. The DNA (μg) of HDAC2 RNAi vector is indicated. 2RNAi is abbreviation of HDAC2 RNAi. (D) Immunoblotting of IkBα protein in HEK293 cells transfected. The change in HDAC2 protein is confirmed in cells transfected for overexpression knockdown.

HDAC3 inhibits NF-kB mediated transcription

HDAC3 was reported to deacetylate NF-kB p65 leading to NF-kB nuclear export (18,19). This activity of HDAC3 may limit transcriptional activity of NF-kB. However, unlike HDAC1, reports about HDAC3 are inconsistent with respect to its corepressor function for NF-kB (23,25). In this study, association of HDAC3 was examined in a ChIP assay after NF-kB activation by TNF-α (Fig. 6A). Before TNF-treatment, HDAC3 signal has already been detectable in the IkBα promoter. The signal was enhanced by TNF-treatment at 30 minutes, peaked at 60 minutes and then reduced by 120 minutes. If HDAC3 acts as an inhibitor of p65, recruitment of HDAC3 should lead to a reduction in gene transcription induced by NF-kB. Three published studies support that HDAC3 can deacetylate p65 (18,19,49). Interestingly, the increase in HDAC3 is correlated with the decrease in HDAC1 at 60 minutes. This data suggests that HDAC3 may be interchangeable with HDAC1 in the inhibition of NF-kB target gene transcription. This observation further supports our hypothesis that corepressor binds to NF-kB even when gene transcription is initiated.

Fig 6. HDAC3 oscillation.

(A) ChIP assay for HDAC3/NF-kB association. This result was obtained in the same condition as for ChIP assay of SRC-1. (B) Knockdown of HDAC3 by vector-based RNAi expression. The DNA (μg) of HDAC3 RNAi vector is indicated. (C) Cotransfection of HDAC3 with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 expression vector at 0.1 μg/point. The HDAC3 DNA (μg) is indicated.

Upon functional analysis, we observed that knockdown of HDAC3 led to a significant enhancement in the IkBα reporter activity (Fig. 6B), suggesting the negative role of HDAC3 in the regulation of NF-kB activity. The activity was confirmed by overexpression of HDAC3 that led to an inhibition of the reporter activity. (Fig. 6C). These functional data suggest that HDAC3 is a corepressor for NF-kB in the IkBα gene promoter.

SMRT and NCoR are corepressors of NF-kB

SMRT and NCoR are two components of the nuclear corepressor complex in which they serve to activate the catalytic function of deacetylases. SMRT and NCoR contribute to the transcriptional repression in a transcription factor-specific manner (50). Data from a NCoR knockout study suggests that N-CoR may also act as a coactivator for expression of certain genes (13). An early study showed that SMRT inhibited the transcriptional activity of NF-kB (14). The inhibition was observed for both p65 and Gal4-p65, suggesting that the activation domain of p65 is targeted by SMRT. SMRT activity in the inhibition of gene transcription was abolished by the chemical inhibitor of histone deacetylase, TSA (Trichostatin A, 100 nM), suggesting that SMRT requires the catalytic function of HDACs for transcriptional inhibition. In the two major subunits of NF-kB, p50 exhibits a stronger interaction with SMRT (14,15). However, it was shown that SMRT failed to inhibit NF-kB activity in a reporter assay. Instead, N-CoR was shown to inhibit the NF-kB reporter activity (23).

In ChIP assays, we observed that both SMRT and NCoR were recruited to the IkBα promoter after NF-kB activation (Fig. 7A). The signals were detectable before TNF-α treatment. TNF-α increased binding of both SMRT and NCoR to the promoter. SMRT and NCoR exhibited different binding patterns in the time course analysis. At 30 minutes, SMRT binding was stronger than that of NCoR. At 60 minutes, this relationship was reversed with NCoR overriding SMRT. At 120 minutes, SMRT and NCoR were both at a submaximum levels. This time-dependent change suggests that SMRT and NCoR may substitute each other in the control of NF-kB activity. Since SMRT and HDAC3 exhibit similar patterns in ChIP assay, SMRT may form complex with HDAC3 in the inhibition of NF-kB activity. In contrast, NCoR and HDAC1 exhibit a similar signal pattern in the ChIP assay. NCoR is likely to form a corepressor complex with HDAC1. The ChIP data from SMRT and NCoR further support the model that corepressors bind to the gene promoter even when gene transcription is initiated.

Fig 7. Switch between SMRT and NCoR.

(A) ChIP assay for SMRT and NCoR interaction with NF-kB association. This result was obtained in the same condition as for ChIP assay of SRC-1. (B) Cotransfection of SMRT or NCoR with IkBα reporter. The IkBα reporter was activated by cotransfection of p65 and p50 expression vectors, which was used at 0.1 μg/point for each vector. Plasmid DNA (μg) for SMRT or NCoR is indicated. (C) Knockdown of SMRT or NCoR by vector-based RNAi expression. Vector DNA (μg) of RNAi expressing plasmid is indicated.

Upon cotransfection, overexpression of SMRT or NCoR leads to an inhibition of IkBα reporter (Fig. 7B). The inhibition was only observed in the presence of p50 in cotransfection, suggesting that an interaction of SMRT or NCoR with p50 is required for the inhibition in physiological conditions. This data also confirms that p50 is the major subunit in the NF-kB heterodimer to interact with SMRT or NCoR. Knockdown of either SMRT or NCoR by RNAi led to a dramatic enhancement of the IkBα reporter activity (Fig. 7C), confirming the corepressor functions of SMRT and NCoR.

Dynamic interaction of coactivators and corepressors with the IkBα promoter

It is believed that removal of corepressor components from nuclear receptors is associated with activation of ligand-bound receptor. Correspondingly, corepressor association leads to inactivation of nuclear receptor and inhibition of transcription. It remains to be determined if this model also works for the DNA-specific transcription factor, like NF-kB. In this study, interaction of NF-kB with the coactivators and corepressors was analyzed systematically. The results suggest that activation of NF-kB by TNF-α not only results in coactivator binding, but also triggers corepressor recruitment. More importantly, recruitment of the two classes of cofactors happens simultaneously (Fig. 8A). Binding of Pol II (RNA polymerase II) to NF-kB was induced by TNF-α and this marks transcription initiation. Since the corepressors did not reduce Pol II signal in the time frame of current study, the result suggests that the coactivators are dominant in the control of transcription after NF-kB activation. This data demonstrate that association of corepressor is persistent and is not an “on or off” phenomenon. Thus, the transcription is determined by the balance between corepressors and coactivators. Coactivators will override the corepressor when an activation signal is integrated into the gene promoter. Otherwise, corepressor is dominant to minimize the gene transcription in prevention of gene leaking in the absence of stimulation. This may explain why gene transcription is tightly regulated in cells under physiological conditions.

Fig 8. Regulation of IkBα mRNA expression.

(A) The ChIP assay was conducted as stated in the method section. To help readers in understanding the complex switches among the coactivators and corepressors, and between the coactivator and corepressors, ChIP data presented in Figures 1 through 7 are combined together here. (B) IkBα mRNA expression was induced by TNF-treatment in 293 cells. IkBα mRNA was determined by Taqman RT-PCR as stated in methods. (C) Regulation of IkBα mRNA by the coactivators and corepressors.

Our data also suggest that there is a switch among the different members of coactivators in the course of gene transcription in order to drive the gene transcription. Such a switch is observed for SRC-1 and SRC-2 (Fig. 8A), suggesting that SRC-1 may be required for TNF-induced gene transcription, and SRC-2 is for basal gene transcription. The data suggests that each isoform of p160 proteins has a stage-specific function in the regulation of gene transcription induced by NF-kB. Collectively, each of the three p160 proteins can substitute among themselves for NF-kB mediated transcription. This explains why there is no function deficiency in NF-kB in the p160 isoform knockout mice, including SRC-1-/-(51,52), SRC-2 -/- (52,53), and SRC-3 -/- (46,47).

This study suggests that corepressor complexes are also subject to exchange during the course of gene transcription induced by NF-kB (Fig. 8A). The binding patterns suggest that SMRT/HDAC1 and NCoR/HDAC3 forms two different corepressor complexes. Although both complexes can inhibit NF-kB activity, it seems that they act at different time point along IkBα transcription induced by NF-kB. At 30 minutes, NCoR/HDAC3 complex is a major player while at 60 minutes, SMRT/HDAC1 is the main corepressor complex. Similarly to the p160 coactivators, the corepressor switch ensures a precise control of gene transcription, and efficient integration of signals from different sources into gene expression. Involvement of both forms of corepressor complexes provides a double check mechanism for the inhibition of NF-kB. Formation of the SMRT/HDAC1 complex may require involvement of unknown proteins since association of these two proteins has not been observed in the process of protein purification. This study also provides evidence that HDAC1 and HDAC3 may use different mechanism in the control of NF-kB activity as their binding patterns to the promoter are different. This study supports a more precise model for interactions of nuclear cofactors with NF-kB in the IkBα gene transcription. Although this study is done with NF-kB, the model of cofactor recruitment may also apply to other DNA-specific transcription factors.

Finally, the promoter activity of the endogenous IkBα gene was determined through measuring mRNA expression using real time RT-PCR. mRNA of IkBα was induced by TNF-treatment (Fig. 8B). This induction was enhanced by coactivators (SRC-1, SRC-2, and SRC-3) and decreased by corepressors (HDAC1, HDAC3, SMRT and NCoR) (Fig. 8C). This group of data suggests that cofactor binding (ChIP data) is consistent with its function in the regulation of gene transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thanks Ms. Kathryn Redd for her excellent technical assistance. This study is supported by NIH grant DK068036 and ADA research award to J Ye.

References

- 1.Sheppard KA, Rose DW, Haque ZK, Kurokawa R, McInerney E, Westin S, Thanos D, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK, Collins T. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(9):6367–6378. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Na SY, Lee SK, Han SJ, Choi HS, Im SY, Lee JW. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(18):10831–10834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkins ND, Felzien LK, Betts JC, Leung K, Beach DH, Nabel GJ. Science. 1997;275(5299):523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerritsen ME, Williams AJ, Neish AS, Moore S, Shi Y, Collins T. PNAS. 1997;94(7):2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baek SH, Ohgi KA, Rose DW, Koo EH, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Cell. 2002;110(1):55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanden Berghe W, De Bosscher K, Boone E, Plaisance S, Haegeman G. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(45):32091–32098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu RC, Qin J, Hashimoto Y, Wong J, Xu J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(10):3549–3561. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3549-3561.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werbajh S, Nojek I, Lanz R, Costas MA. FEBS Lett. 2000;485(2–3):195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(40):36865–36868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong H, Voll RE, Ghosh S. Mol Cell. 1998;1(5):661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okazaki T, Sakon S, Sasazuki T, Sakurai H, Doi T, Yagita H, Okumura K, Nakano H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300(4):807–812. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02932-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogatsky I, Zarember KA, Yamamoto KR. EMBO J. 2001;20(21):6071–6083. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jepsen K, Hermanson O, Onami TM, Gleiberman AS, Lunyak V, McEvilly RJ, Kurokawa R, Kumar V, Liu F, Seto E, Hedrick SM, Mandel G, Glass CK, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG. Cell. 2000;102(6):753–763. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SK, Kim JH, Lee YC, Cheong J, Lee JW. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(17):12470–12474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espinosa L, Ingles-Esteve J, Robert-Moreno A, Bigas A. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14 (2):491–502. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(18):6891–6903. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6891-6903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito K, Jazrawi E, Cosio B, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(32):30208–30215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, Greene WC. Science. 2001;293(5535):1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiernan R, Bres V, Ng RW, Coudart MP, El Messaoudi S, Sardet C, Jin DY, Emiliani S, Benkirane M. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(4):2758–2766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guenther MG, Barak O, Lazar MA. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(18):6091–6101. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6091-6101.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonas BA, Privalsky ML. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54676–54686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410128200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta N, Seto E. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93(1):57–67. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner BP, Westerheide SD, Baldwin AS., Jr Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(20):7065–7077. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.7065-7077.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong H, May MJ, Jimi E, Ghosh S. Mol Cell. 2002;9(3):625–636. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocha S, Campbell KJ, Perkins ND. Mol Cell. 2003;12(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell KJ, Rocha S, Perkins ND. Mol Cell. 2004;13(6):853–865. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishizuka T, Lazar MA. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(15):5122–5131. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5122-5131.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss C, Schneider S, Wagner EF, Zhang X, Seto E, Bohmann D. EMBO J. 2003;22(14):3686–3695. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg364. Weiss, Carsten. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Z, Zuberi A, Quon M, Dong Z, Ye J. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24944–24950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cell. 2000;103(6):843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto Y, Verma UN, Prajapati S, Kwak YT, Gaynor RB. Nature. 2003;423(6940):655–659. doi: 10.1038/nature01576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Science. 1995;270(5240):1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Genes Dev. 2000;14(2):121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leo C, Chen JD. Gene. 2000;245(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torchia J, Rose DW, Inostroza J, Kamei Y, Westin S, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Nature. 1997;387(6634):677–684. doi: 10.1038/42652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litterst CM, Kliem S, Marilley D, Pfitzner E. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(46):45340–45351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson DE, Ihekwaba AE, Elliott M, Johnson JR, Gibney CA, Foreman BE, Nelson G, See V, Horton CA, Spiller DG, Edwards SW, McDowell HP, Unitt JF, Sullivan E, Grimley R, Benson N, Broomhead D, Kell DB, White MR. Science. 2004;306(5696):704–708. doi: 10.1126/science.1099962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong H, Kohli K, Garabedian M, Stallcup M. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(5):2735–2744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voegel JJ, Heine MJ, Zechel C, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. Embo J. 1996;15 (14):3667–3675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen SL, Wang SCM, Hosking B, Muscat GEO. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15 (5):783–796. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.5.0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowan BG, Weigel NL, O'Malley BW. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(6):4475–4483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, Privalsky ML, Nakatani Y, Evans RM. Cell. 1997;90(3):569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan XY, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Trent JM, Meltzer PS. Science. 1997;277(5328):965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Gomes PJ, Chen JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(16):8479–8484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeshita A, Cardona GR, Koibuchi N, Suen CS, Chin WW. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(44):27629–27634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu J, Liao L, Ning G, Yoshida-Komiya H, Deng C, O'Malley BW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6379–6384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120166297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, Rose DW, Hermanson O, Liu F, Herman T, Wu W, Szeto D, Gleiberman A, Krones A, Pratt K, Rosenfeld R, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(25):13549–13554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260463097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu Z, Zhang W, Kone BC. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(8):2009–2017. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000024253.59665.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen LF, Mu Y, Greene WC. Embo J. 2002;21(23):6539–6548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zamir I, Zhang J, Lazar MA. Genes Dev. 1997;11(7):835–846. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu J, Qiu Y, DeMayo FJ, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Science. 1998;279(5358):1922–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picard F, Gehin M, Annicotte J, Rocchi S, Champy MF, O'Malley BW, Chambon P, Auwerx J. Cell. 2002;111(7):931–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mark M, Yoshida-Komiya H, Gehin M, Liao L, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW, Chambon P, Xu J. PNAS. 2004;101(13):4453–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400234101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]