More than 75 years ago, Schoenheimer reported that mammals not only synthesize cholesterol de novo, but also selectively absorb dietary cholesterol from the small intestine while excluding dietary plant sterols and other noncholesterol sterols (1). Subsequent studies have built on this work, demonstrating that cholesterol homeostasis depends on a balance between de novo cholesterol synthesis, the absorption of dietary cholesterol, and excretion of excess cholesterol via the hepatobiliary system. Although cholesterol synthesis and breakdown pathways are well defined, the pathway of dietary cholesterol absorption remains to be elucidated. We still need mechanistic insights to explain Schoenheimer’s observations of selective sterol absorption—that is, the absorption of cholesterol but not plant sterols by intestinal epithelial cells (enterocytes). Given the link between plasma cholesterol levels and heart disease, the mechanism of dietary cholesterol absorption is of great interest (2). Some knowledge has been gained by investigating cellular processes as disparate as vesicular transport, molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum, lipid-transfer proteins, sterol-esterification enzymes, and rare genetic disorders (see the figure). The pharmaceutical industry is actively seeking drugs that specifically inhibit cholesterol absorption without affecting the absorption of other dietary lipids. The discovery of the drug ezetimibe (Zetia)—which specifically blocks intestinal cholesterol absorption by binding to a protein on the apical surface of enterocytes—has garnered much interest. Elucidating the target protein of ezetimibe may reveal the identity of a putative cholesterol transporter. On page 1201 of this issue, Altmann et al. (3) report the discovery of a protein that has the characteristics of a cholesterol transporter, perhaps bringing the search for this elusive protein to a close.

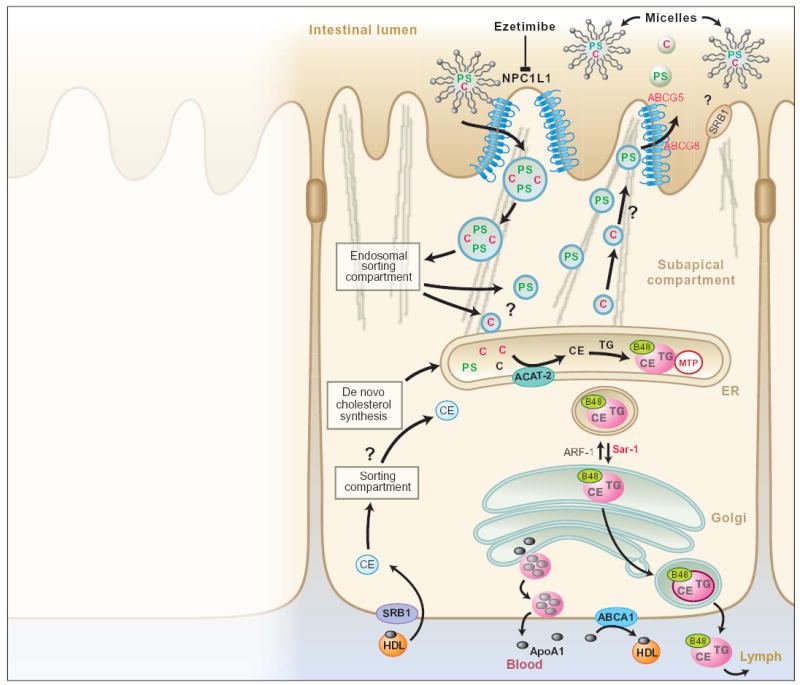

The absorption of dietary cholesterol and noncholesterol sterols.

NPC1L1, expressed at the apical surface of enterocytes, may be the transporter that selectively absorbs dietary cholesterol (C) from micelles in the lumen of the small intestine, a step that is blocked by the drug ezetimibe. We propose a model for NPC1L1 action, in which this transporter permits the uptake of cholesterol (and noncholesterol sterols) into vesicles that then move through a subapical endosomal sorting compartment (6). Mutations in either of the transporters ABCG5 or ABCG8 cause the hyperabsorption of dietary plant sterols (PS) and other noncholesterol sterols from the small intestine, resulting in the human disease sitosterolemia (4, 5). The endosomal sorting compartment allows cholesterol to progress to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it is esterified (CE) by ACAT-2 and then transferred to chylomicrons (pink) ready for secretion into the bloodstream; plant sterols are shunted through a pathway resulting in their transport back to the gut lumen via ABCG5 and ABCG8. Cholesterol that is synthesized de novo is also esterified by ACAT-2 and enters chylomicrons (7). Mutations in the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) result in the human disorder abetalipoproteinemia characterized by secretion of chylomicrons (8). When bound to the protein disulfide isomerase, MTP transfers neutral lipids into newly formed chylomicrons in the ER, a necessary step in the pathway of lipid secretion. Mutations in the small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Sar1, which is involved in trafficking of chylomicrons in the ER, causes chylomicron retention disease (9). Although no human disease has been linked to ARF-1 (ADP-ribosylation factor 1), this GTPase appears to be important for lipoprotein secretion by regulating vesicle budding from the Golgi (10). The parts played by SRB1 (scavenger receptor type B1), expressed on the apical and basolateral enterocyte surface, and ABCA1, expressed on the basolateral enterocyte surface, remain unclear. (TG, triglyceride; B48, apolipoprotein B48; HDL, high density lipoprotein.)

Given that ezetimibe specifically blocks cholesterol absorption, Altmann and colleagues reasoned that its target must have the structural characteristics of a cholesterol transporter. They searched human and rodent expressed sequence tag (EST) databases for protein sequences that are highly expressed in the intestine and that contain characteristic features of transporters (transmembrane domains, an extracellular signal peptide, and N-linked glycosylation sites). But, crucially, they also sought proteins containing a “sterol-sensing” domain as found in other proteins known to interface with cholesterol, such as Neimann-Pick C1 (NPC1), HMG CoA reductase, and the Patched receptor. They identified a single rodent protein with these features and discovered that it is homologous to human Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein (NPC1L1, also known as NPC3). To test whether NPC1L1 is required for cholesterol absorption in vivo, they created a mouse deficient in the Npc1l1 gene. Absorption of dietary cholesterol was almost completely abolished in these mice, and the animals were insensitive to ezetimibe. The Npc1l1-deficient mice appeared normal, except for their inability to absorb dietary cholesterol. Limited biochemical and immunohistological analyses revealed that NPC1L1 is expressed at the enterocyte apical surface (see the figure). Although highly expressed in the small intestine, NPC1L1 is not expressed by neighboring cells. In rodents, Npc1l1 is expressed predominantly in the intestine, whereas in humans it is expressed almost equally in the small intestine and the liver.

Exciting as these data are, a number of questions still need to be addressed. Although NPC1L1 may be the bona fide dietary cholesterol transporter, the authors have yet to provide solid biochemical evidence that ezetimibe binds to this protein. In addition, they have yet to demonstrate that ezetimibe does not bind to the enterocytes of Npc1l1-deficient mice. Ezetimibe is effective in the treatment of a rare autosomal recessive disease called sitosterolemia. This human disease is caused by mutations in either the ABCG5 or ABCG8 transporter, resulting in hyperabsorption of plant sterols from the small intestine (4, 5) (see the figure). Apparently, ezetimibe is an effective treatment because it is able to block the uptake of plant sterols and other noncholesterol sterols as well as cholesterol from the small intestine. An obvious experiment is to examine whether the simultaneous loss of Npc1l1 and Abcg5 or Abcg8 prevents sitosterolemia. Finally, as the human liver seems to express NPC1L1, perhaps the liver is another site of ezetimibe action, although this still needs to be investigated. Thus, identification of the cholesterol transporter is important both from a therapeutic standpoint and for gaining molecular insights into the mechanism of cholesterol absorption.

The findings of Altmann et al. raise important questions that should be addressed in future studies. How are dietary cholesterol and other sterols transported inside the cell? Where in the enterocyte does sorting between cholesterol and noncholesterol sterols (mainly plant sterols) take place? Finally, what are the functions of the other components of the intracellular sterol-trafficking pathway in the absorption of cholesterol.

References

- 1.Schoenheimer R. Z Physiol Chem. 1929;180:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klett EL, et al. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14:341. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000083763.66245.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altmann SW, et al. Science. 2004;303:1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1093131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berge KE, et al. Science. 2000;290:1771. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MH, et al. Nature Genet. 2001;27:79. doi: 10.1038/83799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danielsen EM, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1617:1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon DA, et al. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:317. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang TY, et al. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:289. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones B, et al. Nature Genet. 2003;34:29. doi: 10.1038/ng1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlowe C. Traffic. 2000;1:371. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]