Abstract

Context

In uncontrolled clinical studies, prone positioning appeared to be safe and to improve oxygenation in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. However, the effect of prone positioning on clinical outcomes in children is not known.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that, at the end of 28 days, infants and children with acute lung treated with prone positioning would have more ventilator-free days than those treated with supine positioning.

Design

Multi-center, randomized, controlled clinical trial of supine versus prone positioning. Randomization was concealed. Group assignment was not blinded.

Patients and Setting

We enrolled 102 pediatric patients, 42-weeks post-conceptual age to 18 years, within 48 hours of meeting acute lung injury criteria from seven Pediatric Intensive Care units.

Interventions

Patients randomized to the supine position remained supine. Patients randomized to the prone group were positioned within 4 hours of randomization and remained prone for 20 hours each day during the acute phase of their illness for a maximum of 7 days then remained supine. Both groups were managed using lung protective ventilator and sedation protocols, extubation readiness testing and hemodynamic, nutrition and skin care guidelines.

Main Outcome Measure

Ventilator-free days to day 28. Analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results

The trial was stopped at the planned interim analysis on the basis of the pre-specified futility stopping rule. There were no differences in the number of ventilator-free days between the two groups (15.8 ± 8.5 supine versus 15.6 ± 8.6 prone group, difference −0.2 days, 95 percent confidence interval, −3.6 to 3.2, P=0.91). After controlling for age, Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score, direct versus indirect acute lung injury and mode of mechanical ventilation at enrollment, the adjusted difference in ventilator-free days was 0.3 days (95% confidence interval, −3.0 to 3.5; P=0.87). There were no differences in the secondary endpoints including proportion alive and ventilator-free on day 28, mortality from all causes, the time to recovery of lung injury, organ-failure-free days, and functional health.

Conclusions

Prone positioning does not significantly improve ventilator-free days or other clinical outcomes in pediatric patients with acute lung injury.

Acute lung injury is a major cause of acute respiratory failure in critically ill patients and is associated with several clinical disorders including sepsis, pneumonia, and aspiration.1 Although lifesaving, traditional ventilation strategies with higher tidal volumes and airway pressures can exacerbate lung inflammation and injury.2 Acute lung injury produces parenchymal lung damage that is heterogeneous and may place the patient at risk for ventilator-associated lung injury. When supine, the reduced volume of the nondependent aerated lung is at risk for alveolar overdistention3 while the cyclical ventilation of the dependent lung at low volumes can cause recruitment-derecruitment with subsequent mechanical strain.4 Prone positioning, as first suggested by Bryan5, is a maneuver that can improve ventilation-to-perfusion matching6 and lung mechanics7 in both adult and pediatric patients with severe impairment of gas exchange.8–13 The improved oxygenation and regional changes in ventilation may result in decreased ventilator-associated lung injury14 and facilitate patient recovery.

Although prone positioning is frequently used in the management of pediatric patients with acute lung injury,15 there are no data that suggest improved clinical outcomes. Gattinoni and colleagues16 showed no effect of 7 hours per day of prone positioning on survival in adult patients with acute lung injury. Prone positioning improved oxygenation and a post hoc analysis suggested improved outcomes in those with severe acute lung injury. Using a similar study design, Guerin and colleagues17 extended the study population to include all adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and again found improved oxygenation but no difference in survival or ventilator days between the prone and supine groups. Both trials used prone positioning for relatively short periods each day, did not require a lower tidal volume approach, and did not include children. Therefore, we examined prolonged periods of prone ventilation combined with a lower tidal volume approach in children with acute lung injury. We tested the hypothesis that children with acute lung injury treated with prone positioning would have more ventilator-free days than those treated with supine positioning.

METHODS

Patients were enrolled from August 2001 through April 2004 at seven pediatric intensive care units that participate in the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. The study design was approved by the institutional review board of each hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or legal guardian of each subject.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were pediatric patients (2 weeks to 18 years) who were intubated and mechanically ventilated with a ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 300 or less (adjusted to 253 in Salt Lake City because of altitude), bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and no clinical evidence of left atrial hypertension.18 Patients were excluded if they were less than 2 weeks of age (newborn physiology), less than 42 weeks post-conceptual age (considered preterm), unable to tolerate a position change (persistent hypotension, cerebral hypertension); had respiratory failure from cardiac disease; had hypoxemia without bilateral infiltrates; had received a bone marrow or lung transplant; were supported on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; had a nonpulmonary condition that could be exacerbated by the prone position; had participated in other clinical trials within the preceding 30 days; or if there was a decision to limit life support. Randomization was done using a permuted blocks design, stratified by center, with random block sizes. Allocation was concealed; each center received serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes containing study assignments.

Treatment Procedures

Eligible patients were randomized within 48 hours of meeting study criteria to either supine or prone positioning. The clinical and research team were not blinded to treatment assignment. Patients randomized to the supine group remained supine. Patients randomized to the prone group were positioned prone within 4 hours of randomization and remained prone for 20 hours each day during the acute phase of their illness for a maximum of 7 days of treatment, after which they were positioned supine. When prone, individually sized cushions were used to splint the most compliant aspect of the chest wall over the sternum and unrestrain the diaphragmatic-abdomen component of the chest wall.7 (Please see attached protocols for consideration for online publication.)

The acute phase of illness was defined as the time interval between randomization and the time at which extubation readiness criteria were met: specifically, spontaneous breathing, oxygenation index (mean airway pressure/[PaO2:FiO2 ratio] x 100) less than 6, and a decrease in ventilator support over the previous 12 hours.19 Patients in both groups were assessed each morning while in the supine position. Thus the length of prone positioning could be less than 20 hours on day 1. Other than positioning, both groups were managed with specific care algorithms, which included ventilator and sedation protocols, extubation readiness testing, as well as hemodynamic, nutrition and skin care guidelines during the 28 day period.

Data Collection

At enrollment, admission functional health20 and Pediatric Risk of Mortality III21 data were recorded. Race and ethnic group were assigned by the investigators. We also monitored circulatory, pulmonary, coagulation, hepatic, renal, and neurological system function daily for 28 days.

Patients randomized to prone positioning had their physiologic values and arterial blood gases assessed before and one hour after each supine-to-prone and prone-to-supine turn. Days in which a patient exhibited a 20 or more increase in the PaO2:FiO2 ratio or a 10% or more decrease in oxygenation index after a supine to prone turn were classified a priori as responder days.22 Patients who experienced more responder days than nonresponder days over the entire study period were considered overall responders; when equal, the patient’s overall response was categorized by their day 1 response.9

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was ventilator-free days, defined as the number of days a patient breathed without assistance for at least 48 consecutive hours from day 1 to day 28 after randomization.23 Secondary endpoints included alive and ventilator-free on day 28, mortality from all causes, the time to recovery of lung injury, organ-failure-free days, and functional health. Time to recovery of lung injury was defined as the number of days from randomization to meeting extubation readiness testing criteria for 24 consecutive hours through day 28. Organ-failure-free days were defined as the number of days from day 1 to day 28 in which a patient was without clinically significant non-pulmonary organ dysfunction. The pediatric logistic organ dysfunction (PELOD) score parameters24 were used to define pediatric organ dysfunction. Functional health was defined as differences in cognitive impairment and overall functional health from intensive care admission to hospital discharge or day 28 (whichever occurred first) using the Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category score and Pediatric Overall Performance Category score.20

Statistical Methods

To ensure adequate power for the interim and final analyses, we conservatively based our sample estimate on a dichotomous outcome - the proportion of patients who were alive and ventilator-free at the end of 28 days. We used data from our Phase One study9 in which 25 consecutive prone positioned patients were matched (on acute lung injury trigger, age, and closest PRISM score on admission and oxygenation index at enrollment) 1:2 to a historical control group derived from the Pediatric ARDS Data Set.19 After we excluded bone marrow transplant recipients from the analysis, 18 of 20 (90%) prone positioned patients were alive and ventilator-free on day 28 compared to 26 of 40 (65%) matched supine positioned patients. Prone positioned patients also experienced more ventilator-free days (15 ± 9 days) than supine positioned patients (8 ± 9 days). Assuming 10% non-compliance in each group, we calculated that a sample size of 90 subjects per group was required to yield 90% power to detect the non-compliance adjusted difference of 87.5% (90% x 90% + 65% x 10%) versus 67.5% (65% x 90% + 90% x 10%) in the proportion of patients alive and ventilator-free on day 28, using a fixed sample size chi-square test (nQuery Advisor 3.0, Statistical Solutions, Boston, MA).

We planned a single interim analysis after 50% of patients had completed their participation in the study using the O’Brien-Fleming stopping rule25, with a priori boundaries of P < 0.006 (|Z| > 2.74) to reject the null hypothesis (efficacy boundary, if large treatment differences appear before the end of the study) and P > 0.52 (|Z| < 0.70) to accept the null hypothesis (futility boundary, if there is little chance of finding a significant difference between groups). Allowing for this interim analysis with possible early stopping, a sample size of 90 patients per group provided 88% power to detect the difference of 87.5% versus 67.5% in proportion of patients alive and ventilator-free on day 28 between treatment groups using a chi-squared test and 82% power to detect a difference of at least 4 ventilator-free days between treatment groups via a Student’s t-test (assuming a common standard deviation of 9 days for each group) (East 3.1, Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, MA). Thus this study was adequately powered to detect the hypothesized difference of at least 4 ventilator-free days or a 20% or greater difference in the proportion of ventilator-free and alive on day 28.

The primary analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis. We used the Student’s two-sample t-test, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to compare baseline characteristics. Student’s t-test was used to compare the number of ventilator-free days between the two groups. Multiple linear regression analysis was then used to control for age, PRISM III score, mode of mechanical ventilation at enrollment, and direct versus indirect cause of lung injury. Center effect was not included in regression models as doing so did not appreciably affect treatment group comparisons and because center effects were not statistically significant. No lack of fit, deviation from the homoscedasticity assumption, or outliers were indicated in the residual plots against variables in the model or against selected variables not in the model. A quantile normal plot of the residuals revealed no clear deviation from normality. The secondary outcomes and adverse events were compared using the two-sample t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, except that the time to recovery of lung injury was analyzed using the log rank test. Although two-sample t-tests are known to be robust for deviation from normality for the sample sizes in the current study, we also performed Wilcoxon rank sum tests since they may be more powerful than t-tests for non-normal data. The p-values for Wilcoxon rank sum tests were not reported unless the significance result differed from t-tests. All analyses were performed with SAS software (Version 9.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

The Data and Safety Monitoring Board stopped the trial at the interim analysis, after 102 patients had been enrolled, on the basis of the pre-specified futility stopping rule. At this time, based on the 94 patients who had completed the 28-day study period (47 prone and 47 supine), comparison of the primary outcome variable (ventilator-free days) via t-test (P=0.87) or multiple linear regression (P=0.55) crossed the a priori futility boundary for early stopping with acceptance of the null hypothesis of no difference between groups. An identical conclusion was reached using the comparison between proportions of patients alive and ventilator-free on day 28 (P=0.60 Chi-square test). At the interim analysis, it was calculated that if the study had continued to the planned enrollment of 180 patients, the probability of demonstrating a difference in ventilator-free days between treatment groups was less than 1 percent under the alternative hypothesis based on the observed unadjusted ventilator-free day treatment group differences. Analyses below report on data from all 102 patients enrolled.

Study Population

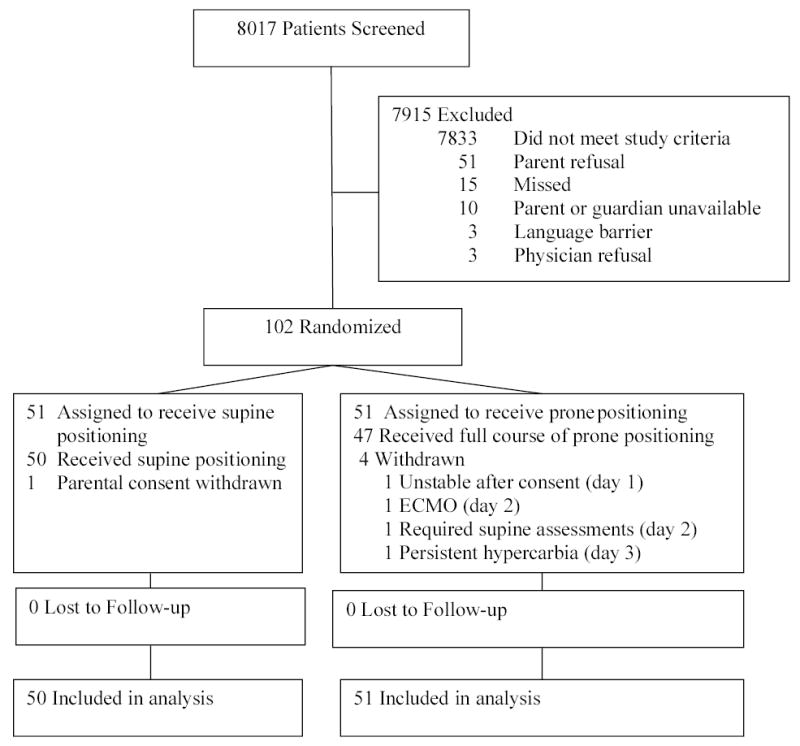

Of the 8017 intubated ventilated pediatric patients screened for the study, 184 met acute lung injury criteria and 102 were enrolled and randomized, 51 patients to each group (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics and respiratory variables at enrollment were similar between the two groups (Table 1 and Table 2). More patients in the prone group were initially supported on high frequency oscillatory ventilation (12% supine; 29% prone; Chi-square test P=0.03). This difference was no longer significant after the implementation of study protocols when patients in both groups with an oxygenation index of greater than 20 were transitioned to high frequency oscillatory ventilation.

Figure 1.

Patient Flow through Clinical Trial

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Enrollment*

| Characteristic | SupineGroup(N=51) | ProneGroup(N=51) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 2.1 (0.3, 11.0) | 2.0 (0.3, 8.2) |

| Age group No. (%) | ||

| <2 years | 25 (49%) | 25 (49%) |

| 2 to 8 years | 10 (20%) | 13 (25%) |

| >8 years | 16 (31%) | 13 (25%) |

| Female sex No. (%) | 21 (41%) | 27 (53%) |

| Race or ethnic group† No. (%) | ||

| White | 28 (56%) | 27 (54%) |

| Black | 6 (12%) | 5 (10%) |

| Hispanic | 10 (20%) | 14 (28%) |

| Asian | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| More than one group | 2 (4%) | 4 (8%) |

| Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category‡ | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) |

| Pediatric Overall Performance Category§ | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) |

| Pediatric Risk of Mortality III scores|| | 11 ± 9 | 11 ± 8 |

| Risk of Mortality | 3% (2%, 12%) | 6% (1%, 23%) |

| No. of nonpulmonary organ or system failures¶ | 2 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 2) |

| PaO2:FiO2** | 105 ± 48 | 94 ± 41 |

| PaO2:FiO2 ratio ≤ 200** No. (%) | 49 (96%) | 50 (98%) |

| Cause of lung injury No. (%) | ||

| Pneumonia | 27 (53%) | 29 (57%) |

| Bronchiolitis with pneumonia | 8 (16%) | 6 (12%) |

| Sepsis | 7 (14%) | 7 (14%) |

| Aspiration | 6 (12%) | 5 (10%) |

| Other | 3 (6%) | 4 (8%) |

| Direct†† pulmonary injury No.(%) | 44 (86%) | 42 (82%) |

Values with plus-minus signs are means ± SD; values with parentheses are number (percentage) or medians (first quartile, third quartile). Because of rounding, percentages may not total 100. PaO2 denotes partial pressure of arterial oxygen tension, and FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups for any of these variables.

Race and ethnicity could not be determined for two patients (one in supine and one in prone group).

Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category score ranges from 1 (normal cognitive development) to 6 (brain death).20

Pediatric Overall Performance Category score ranges from 1 (good overall performance) to 6 (brain death).20

Scores from the Pediatric Risk of Mortality III can range from 0–74, with higher scores indicating higher probability of death.21

Patients were monitored for neurological, cardiovascular, renal, hematological and hepatic failure.24

Arterial blood gases in both groups were assessed while in the supine position. PaO2:FiO2 values from Salt Lake City were normalized for altitude. Data reflect the lowest PF ratio on the day of enrollment.

Direct pulmonary injury originates from pulmonary disease.34

Table 2.

Respiratory Values at BASELINE, study Day 1, and Average in Acute Phase*

|

BASELINE† |

Study Day1† |

Average inAcutePhase† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Supine (N=51) | Prone (N=51) | Supine (N=50) | Prone (N=50) | Supine (N=50) | Prone (N=50) |

| PaO2:FiO2 ratio | 147 ± 60 | 153 ± 65 | 157 ± 63 | 159 ± 74 | 176 ± 62 | 183 ± 69 |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 49 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| Oxygenation index | 15 ± 12 | 18 ± 18 | 14 ± 11 | 15 ± 12 | 12 ± 9 | 11 ± 9 |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 49 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| PaO2 (mm Hg) | 76 ± 26 | 84 ± 32 | 76 ± 25 | 78 ± 29 | 78 ± 18 | 80 ± 19 |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 49 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | 48 ± 12 | 46 ± 10 | 50 ± 12 | 54 ± 13 | 53 ± 12 | 56 ± 13 |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 49 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| Arterial pH | 7.37 ± 0.08 | 7.39 ± 0.07 | 7.38 ± 0.06 | 7.36 ± 0.10 | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 7.38 ± 0.07 |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 49 | 50 | 49 | 50 |

| Tidal volume (ml per kilogram of ideal body weight) | 7.7 ± 2.1 | 7.6 ± 2.9 | 6.6 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 1.0‡ | 6.2 ± 1.1‡ |

| No. of patients | 34 | 27 | 39 | 34 | 42 | 42 |

| Mean airway pressure | ||||||

| Conventional mechanical ventilation (cm of water) | 15 ± 5 | 16 ± 5 | 14 ± 4 | 14 ± 5 | 13 ± 4 | 12 ± 4 |

| No. of patients | 45 | 36 | 39 | 34 | 42 | 42 |

| High frequency oscillatory ventilation (cm of water) | 26 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | 29 ± 6 | 25 ± 6 | 27 ± 4§ | 23 ± 5§ |

| No. of patients | 6 | 15 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 17 |

| Supported on high frequency oscillatory ventilation (%) | 12%|| | 29%|| | 22% | 32% | 24% | 27% |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Minute ventilation (liters/min) | 1.8 (1.0, 5.7) | 1.6 (1.1, 4.4) | 1.6 (0.9, 3.6) | 1.8 (0.7, 3.8) | 1.6 (1.0, 3.2) | 1.6 (0.6, 2.8) |

| No. of patients | 34 | 27 | 39 | 34 | 42 | 42 |

| FiO2 | 0.58 ± 0.19 | 0.61 ± 0.19 | 0.54 ± 0.17 | 0.55 ± 0.18 | 0.49 ± 0.13 | 0.49 ± 0.14 |

| No. of patients | 51 | 51 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| PEEP (cm of water) | 8.4 ± 3.4 | 9.5 ± 3.2 | 7.8 ± 3.2 | 8.4 ± 3.1 | 7.7 ± 2.7 | 7.2 ± 2.2 |

| No. of patients | 45 | 36 | 39 | 34 | 42 | 42 |

Values with plus-minus signs are means ± SD; values with parentheses are medians (first quartile, third quartile). PaO2 denotes partial pressure of arterial oxygen tension, and FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen. Patients in both groups were assessed while in the supine position. PaO2:FiO2 values from Salt Lake City were normalized for altitude.

Baseline is prior to the institution of study protocols, Day 1 is the first 10am±2hr assessment; average in acute phase was calculated as the average of the morning (10am ± 2hr) assessments in the acute phase.

The average tidal volume in acute phase was significantly different between the two groups (two-sample t-test P=0.02).

The average mean airway pressure for patients supported on high frequency oscillatory ventilation in acute phase was significantly different between the two groups (two-sample t-test P=0.04; Wilcoxon rank sum test P=0.08).

The proportion of high frequency oscillatory ventilation was significantly different between the two groups at baseline (Chi-square test P=0.03).

Outcomes

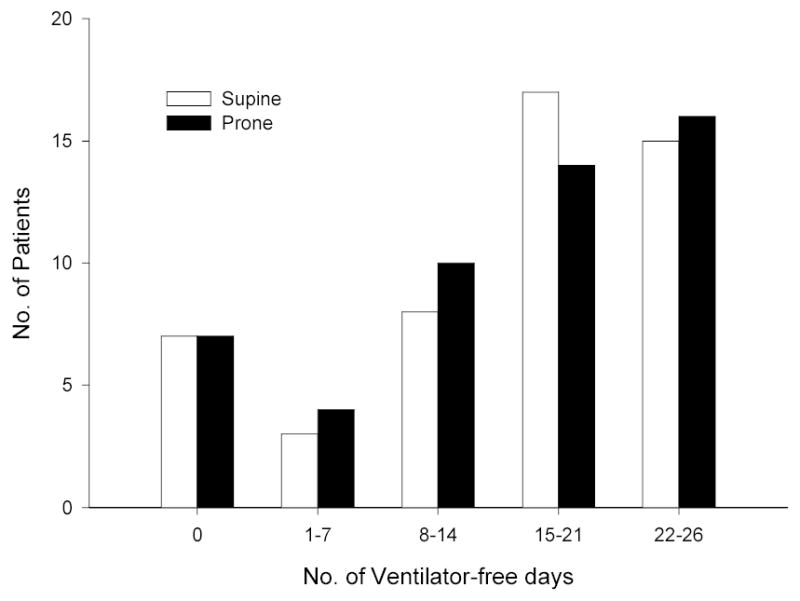

The primary outcome, number of ventilator-free days, was not significantly different between the two groups (15.8 ± 8.5 supine; 15.6 ± 8.6 prone; two-sample t-test P=0.91; prone to supine difference −0.2 days, 95 percent confidence interval, −3.6 to 3.2; Table 3 and Fig. 2). After controlling for age, Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score, direct versus indirect cause of acute lung injury and mode of mechanical ventilation at enrollment in a multiple linear regression analysis, the adjusted prone to supine difference was 0.3 days (Wald test P=0.87; 95 percent confidence interval, −3.0 to 3.5). In addition, we found no evidence that age was a confounder (when excluding age from model, prone to supine difference was 0.4 days, similar to that when age was included in the model; 95 percent confidence interval −2.9 to 3.7) or effect modifier of the association between prone vs. supine positioning and ventilator-free days (F test for position by age interaction P=0.53). In particular, the ventilator free days for the three age groups were: < 2 years: supine 18.7 ± 7.1, prone 18.6 ± 7.6, difference −0.1 days, 95 percent confidence interval −4.4 to 4.1; 2 to 8 years: supine 14.6 ± 8.3, prone 11.5 ± 8.3, difference −3.1 days, 95 percent confidence interval −10.4 to 4.1; >8 years: supine 12.2 ± 9.4, prone 14.0 ± 9.2, difference 1.8 days, 95 percent confidence interval −5.3 to 9.0.

Table 3.

Primary and Secondary Outcome Variables*

| Outcome | Supine(N=50)† | Prone(N=51) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of ventilator-free days from day 1 to day 28 | 15.8 ± 8.5 | 15.6 ± 8.6 | 0.91 |

| Mean ± SD | |||

| Alive and ventilator-free on day 28 No. (%) | 43 (86%) | 41 (80%) | 0.45 |

| Deaths No. (%) | 4 (8%) | 4 (8%) | 1.00 |

| No. of days to recovery of lung injury‡ | 5 (3, 9) | 4 (2, 9) | 0.78 |

| Median (Q1,Q3) | |||

| No. of days without failure of circulatory, neurological, coagulation, hepatic and renal organs from day 1 to day 28§ | 17 (7, 22) | 16 (9, 22) | 0.88 |

| Median (Q1,Q3) | |||

| Worse Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) Score from PICU admission to hospital discharge|| (or day 28) No. (%) | 11 (22%) | 6 (12%) | 0.16 |

| Worse Pediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC) Score from PICU admission to hospital discharge|| (or day 28) No. (%) | 14 (29%) | 8 (16%) | 0.12 |

Values with plus-minus signs are means +/− SD. The P-value is based on the Student’s t-test for number of ventilator-free days and number of days without nonpulmonary organ failures, log rank test for number of days to recovery of lung injury, Fisher’s exact test for mortality, and Chi-square test for the remaining outcomes.

All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis except one supine patient for whom parental consent was withdrawn.

In survivors, number of days from randomization to achieve an oxygenation criterion; oxygenation index of 6 or lower for 24 consecutive hours through day 28.

Patients were monitored daily for 28 days for neurological, cardiovascular, renal, hematological and hepatic failure. This variable was not available for ten patients who transferred to other acute care facilities during the 28-day study period (six supine, four prone).

POPC and PCPC were not available for one supine patient. One prone patient, with a static baseline to hospital discharge PCPC/POPC, died during a subsequent readmission from a nonpulmonary problem.

Figure 2.

Number of Ventilator-free Days in the Control Group and the Prone Positioned Group. There were no significant differences between the two groups (two-sample t-test P=0.91).

The proportion of patients alive and ventilator-free on day 28 was 86% in the supine and 80% in the prone group (RR = 0.93, 95 percent confidence interval 0.78 to 1.11, Chi-square test P=0.45). The mortality rate was 8% in both groups (RR = 0.98, 95 percent confidence interval 0.26 to 3.71, Fisher’s exact P=1.00). There were no significant differences in the secondary endpoints of time to recovery of lung injury, organ-failure-free days and functional outcomes (Table 3) or sedative use (Table 4) between the two groups. There were also no significant differences in the number of survivors who were oxygen dependent on day 28 (20% supine and 26% prone, Chi-square test P = 0.49).

Table 4.

Sedation use during the acute phase*

| SupineGroup(N=50) | ProneGroup(N=50) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average† | median (Q1, Q3) | ||

| Morphine equivalents | 2.9 (1.6, 4.7) | 3.3 (1.5, 5.2) | |

| Midazolam equivalents | 2.5 (1.2, 4.2) | 2.1 (1.2, 4.2) | |

| Sedation score | 57 (43, 86) | 60 (34, 87) | |

| Total‡ | |||

| Morphine equivalents | 12.2 (4.9, 24.3) | 9.9 (4.5, 23.1) | |

| Midazolam equivalents | 12.1 (3.4, 21.4) | 8.7 (3.0, 14.5) | |

| Sedation Score | 262 (100, 478) | 199 (93, 435) | |

All opiates were converted to morphine equivalents using the following conversions to equal 1 mg of morphine sulfate: 15 μg fentanyl citrate, 0.15 mg hydromorphone hydrochloride, 0.3 mg methadone hydrochloride, 20 mg codeine. All benzodiazepines were converted to midazolam equivalents using the following conversions to equal 1 mg of midazolam: 2 mg diazepam, 0.33 mg lorazepam. For the sedation scoring, 1 point was given for each of the following: morphine or midazolam equivalents of 0.1 mg per kilogram of body weight, pentobarbital 2 mg/kg, chloral hydrate 50 mg/kg, any propofol use, any phenobarbitol use. Use of any antihistamines received a point score of 0.5.35

Average calculated per patient per day (mg per kilogram of body weight per day).

Total is sum (mg per kilogram of body weight) during the acute phase.

There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups for any of these variables (two-sample t-test).

Prone Positioning and Oxygenation

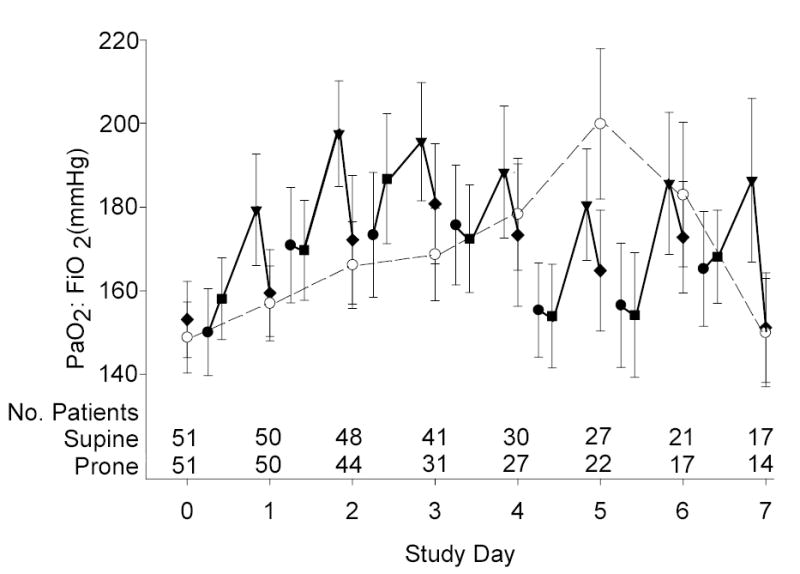

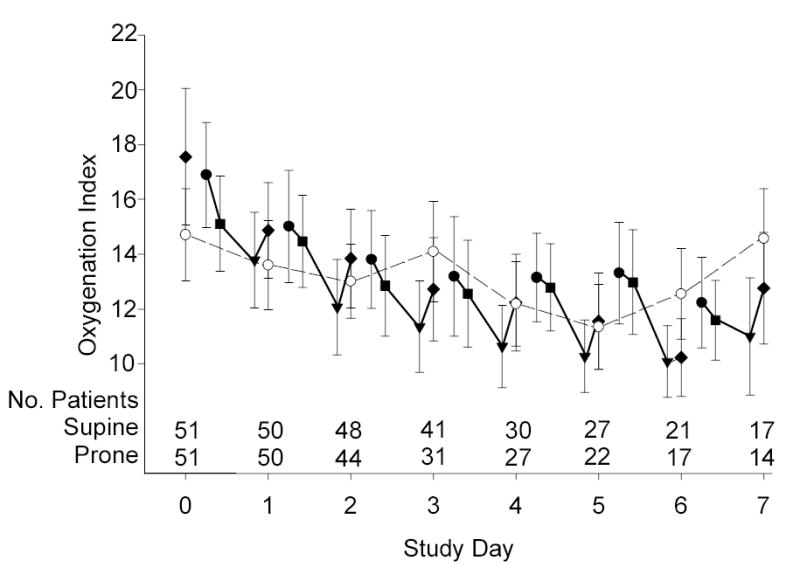

Patients who were randomized to the prone group were positioned within 28 hours of meeting study criteria (median; Q1-Q3, 18–39 hours) and within 2.3 hours of randomization (median; Q1-Q3, 1.6–3.5 hours). On average, patients remained prone for 18 ± 4 hours per day for 4 days (range 1 to 7 days), which accounted for 79% ± 9% of the acute phase of illness. The PaO2:FiO2 ratio and oxygenation index response to positioning are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3a & 3b.

Mean (± SE) PaO2:FiO2 ratio (3a) and Oxygenation Index (3b) during the Acute Phase. The prone group is denoted by solid symbols: immediately before prone positioning (circles), after one hour prone (squares), after 20-hour prone (triangles), and at 10am supine on each study day (diamonds). The supine group was denoted by open symbols also at 10am on each study day (circles). Time zero reflects supine values in both groups prior to the implementation of ventilator protocols. Each calculation includes data from all patients, regardless of how many measurements were available from each patient on that day. Also shown are the number of patients who contributed at least one measurement to the calculation. The morning supine PaO2:FiO2 ratio and oxygenation index was not significantly different between the two groups for any of the acute phase days (two-sample t-test P≥0.15).

Sixty-four percent of 202 daily pronation procedures resulted in a PaO2:FiO2 ratio increase of 20 mm Hg or more or an oxygenation index decrease of 10% or more. Based on the patient’s multiple day oxygenation response, 90% of prone patients were categorized as overall “responders” to prone positioning. The number of ventilator-free days was not significantly different between overall responders and non-responders to prone positioning (two-sample t-test P=0.85).

Protocol Deviations and Adverse Events

All positioning and adjunctive therapy protocols were stopped during the acute phase in 4 patients (three prone, one supine; see Figure 1). In the prone group one patient became hemodynamically unstable after consent had been obtained (day 1), one patient failed conventional therapies and was cannulated for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (day 2), and one patient demonstrated persistent hypercarbia in the prone position (day 3). One parent in the supine group withdrew consent on day 1. Prone positioning alone was stopped on day 2 in a patient with sickle cell disease because of splenic sequestration. Except for one supine patient for whom parental consent was withdrawn, all patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Position-Related Complications

All position related adverse events are listed in Table 5. Five patients experienced serious study-related events, four in the prone group and one in the supine group (Fisher’s exact P=0.36). In the prone group, three patients experienced hypercarbia and one patient’s endotracheal tube was twisted and partially obstructed during a head turn while prone. All four of these patients were on high frequency oscillatory ventilation at the time of the event and all four survived. The single study-related serious adverse event in the supine group was a Stage IV pressure ulcer26, 27 and the patient did survive.

Table 5.

Adverse events

| SupineGroup(N=50) | ProneGroup(N=51) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Events(number of patients) | Events(number of patients) | ||

| Inadvertent endotracheal tube extubation | 5 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| Plugged endotracheal tube | 0 | 2 (2) | |

| Endotracheal reintubation (after passing the extubation readiness test for upper airway obstruction) | 5 (4) | 6 (6) | |

| Transient desaturation | 6 (2) | 5 (3)* | |

| Transient hypercarbia | 0 | 4 (3) | |

| Bradycardic episode | 0 | 4 (1) | |

| Pneumothorax or pneuomediastinum | 3 (2) | 0 | |

| Pressure ulcer | |||

| Stage II | 12 (7) | 12 (9) | |

| Stage III | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Stage IV | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Loss of arterial access | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Paraphimosis | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Abdominal ascites | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Circumoral rash | 0 | 1 (1) | |

Two of the five transient desaturation events occurred in one patient while supine.

COMMENT

In this intervention trial of 102 pediatric patients with acute lung injury, there were no significant differences in the number of ventilator-free days, mortality, time to recovery of lung injury, organ-failure-free days or functional outcome between the prone and supine groups. Although we examined prolonged periods of prone ventilation combined with a lower tidal volume approach in children with acute lung injury, our results are similar to previously reported studies in the adult population.16, 17

As described in several nonrandomized studies,9, 10, 12 most of our patients positioned prone did exhibit an improvement in oxygenation; however, these improvements were not associated with a decrease in the duration of ventilator support. Our 20-hour per day protocol was much longer than the 7 and 8 hour protocols that were previously tested in adult patients.16, 17 This study was designed so that patients could be afforded the potential lung protective effects of prone ventilation early and throughout the acute phase of illness. This aim was achieved as patients were positioned prone on average 28 hours after meeting eligibility criteria and were managed in the prone position for 79% of the acute phase of illness. Even though patients in this trial received early and prolonged use of the prone position, we were unable to demonstrate beneficial effects on clinical outcomes.

Ninety percent of prone positioned patients were categorized as “responders” by some improvement in oxygenation efficiency. The mechanism by which prone positioning leads to an improvement in oxygenation is not fully understood especially in a developmentally immature patient. In infancy, chest wall compliance is nearly three times that of the lung.28 By the second year of life, the increase in chest wall stiffness is such that the chest wall and lung have similar compliance as in adults. By eight years of age, the height of the chest wall is similar to that of an adult. Pelosi and colleagues7 reported that thoracoabdominal compliance decreases in the prone position and the magnitude of this change are correlated with the observed change in oxygenation; that is, the greater the decrease in thoracoabdominal compliance, the greater the improvement in oxygenation with prone positioning. Given the demonstration that improved oxygenation with prone positioning is correlated with the magnitude of supine-prone difference in chest wall compliance in adults,7 we predicted that prone positioning would be more effective for improving oxygenation thus clinical outcomes in the younger patients enrolled in our clinical trial. Our results did not support this prediction.

The primary outcome for this study was ventilator-free days, a composite outcome that reflects both survival and duration of mechanical ventilation.23 We selected this outcome variable because we hypothesized that prone positioning would simultaneously reduce mortality and shorten the duration of ventilation. Compared to previous studies investigating acute lung injury in adult patients,2, 16, 17, 29–31 we report lower mortality and more ventilator-free days. Aside from age and excluding patients post bone marrow transplant, our patient population was similar to previous studies investigating prone positioning in adult patients.16, 17

To evaluate the nonpulmonary effects of the prone position, a number of secondary outcomes were analyzed. Nonpulmonary organ-failure-free days an outcome that provides insight into the lethal multiple organ dysfunction related to acute lung injury,32 were not significantly different between the two groups. This may be related to the small number of septic patients in our study, a population that consistently manifests the largest number of organ failures in clinical trials.1 Furthermore, the use of a lung-protective ventilator protocol limited the potential for differences in treatment outside of the positioning protocols.

Our study design also included assessment of functional health, which provided additional insight on important surrogate outcomes. Not all pediatric patients who survived acute lung injury returned to their previous level of function. Specifically, 11% of survivors suffered worsening cerebral function and 16% of survivors suffered worsening overall functional ability. To our knowledge, this is the first study of acute lung injury describing the impact of acute lung injury on functional outcomes in the pediatric population.

Little is known about the relationship between acute phase management (specifically, optimal levels of oxygenation in the acute phase) and functional outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. In pediatrics, several functional outcome and quality of life measures are now available. Future interventional studies should concentrate on looking past the immediate outcome of the episode of illness and focus on the patient’s functional capacity and quality of survival.33

There are limitations to this clinical trial. First, it was not possible to blind clinicians to group assignment so observer bias may have been introduced. However, several aspects of the trial design should have limited this potential bias including the use of algorithms for most aspects of clinical care as well as the use of objective outcome measures. Second, this study was not designed to show equivalence between prone and supine positioning. Our trial design included a futility stopping boundary because we thought it would be inappropriate to continue to randomize patients into a study in which there was little chance of finding statistically significant differences in the main clinical outcomes. Stopping the study for futility at the planned interim analysis could have caused a type II error (false negative result), that is, failing to detect a prone positioning possible benefit of 3.5 ventilator free days or possible harm of 3.0 ventilator free days as indicated from the 95 percent confidence interval. Third, given the smaller total sample size induced by stopping early, we might not have observed a rare position-related complication in the study.

CONCLUSIONS

Shortcomings of previous clinical studies of prone positioning have included the lack of treatment algorithms for adjunctive care of study patients that might impact primary or secondary study outcomes. In this trial, carefully designed protocols to define ventilator management, extubation readiness, and the use of sedative agents were implemented to minimize variation in the daily management of both groups. Despite careful control of these co-interventions, pediatric patients positioned prone did not demonstrate improved clinical outcomes. While we can rule out a large beneficial treatment effect, we cannot exclude a small treatment effect, including a small negative effect. However, based on the interim analysis done at the study midpoint, the results of this trial do not support the continued use of prone positioning as a therapeutic intervention to improve the outcomes in pediatric patients with acute lung injury.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the pediatric critical care nurses, respiratory therapists, physicians and our patients and their families who supported this clinical trial and to our colleagues in the PALISI network who helped sustain this clinical trial.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Curley had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

- Study concept and design: Curley, Hibberd, Wypij, Thompson, Matthay, Arnold

- Acquisition of data: Curley, Fineman, Grant, Barr, Cvijanovich, Sorce, Luckett

- Analysis and interpretation of data: Curley, Hibberd, Wypij, Shih, Thompson, Arnold

- Drafting of the manuscript: Curley, Hibberd, Wypij, Shih, Matthay, Arnold

- Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Curley, Hibberd, Fineman, Wypij, Shih, Thompson, Grant, Barr, Cvijanovich, Sorce, Luckett, Matthay, Arnold

- Statistical analysis: Curley, Hibberd, Wypij, Shih

- Obtained funding: Curley, Thompson, Hibberd, Wypij

- Administrative, technical, or material support: Curley, Fineman, Wypij, Grant, Barr, Cvijanovich, Sorce

- Study supervision: Curley

Financial Disclosures: None

Funding Support: NIH/NINR RO1NR05336; RR00064; RR00054; Equipment support: Novametrix Medical Systems, Medical Ventures, i-STAT Corporation.

Role of Sponsor: The NIH/NINR, Novametrix Medical Systems, Medical Ventures, and i-STAT Corporation were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; data collection, data management, data analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Participants in the Pediatric Prone Study Group: Children’s Hospital Boston: J.H. Arnold, R. Johnson, M. LaBrecque, J.E. Thompson; Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago: L. Sorce, D. Steinhorn; Primary Children’s Medical Center: M.J. Chellis Grant, C. Maloney; University of California, San Francisco: L.D. Fineman, J. Gutierrez, M.A. Matthay; Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital: F.E. Barr, J. Forlidas, A. Johnson; Children’s Medical Center of Dallas: P.M. Luckett, S. Molitor-Kirsch; Children’s Hospital Oakland: N. Cvijanovich, L. Wertz. Data Coordination Center: P.L. Hibberd, P. Hopkins, M. McCarthy, A. Netson, MC. Shih, S. Wong, D. Wypij. Project Director: M. LaBrecque. External Quality Monitor: R. Lebet; Data and Safety Monitoring Board: K. Stone (Chair), R. Clark, R.M. Kacmarek, D.A. Schoenfeld.

References

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyfuss D, Soler P, Basset G, Saumon G. High inflation pressure pulmonary edema. Respective effects of high airway pressure, high tidal volume, and positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137(5):1159–1164. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.5.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muscedere JG, Mullen JB, Gan K, Slutsky AS. Tidal ventilation at low airway pressures can augment lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(5):1327–1334. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan AC. Comments of a devil’s advocate. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110:143–144. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.6P2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamm WJ, Graham MM, Albert RK. Mechanism by which the prone position improves oxygenation in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(1):184–193. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelosi P, Tubiolo D, Mascheroni D, et al. Effects of the prone position on respiratory mechanics and gas exchange during acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(2):387–393. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.97-04023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatte G, Sab JM, Dubois JM, Sirodot M, Gaussorgues P, Robert D. Prone position in mechanically ventilated patients with severe acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(2):473–478. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curley MAQ, Thompson JE, Arnold JH. The effects of early and repeated prone positioning in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Chest. 2000;118(1):156–163. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murdoch IA, Storman MO. Improved arterial oxygenation in children with the adult respiratory distress syndrome: the prone position. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(10):1043–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb12981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Numa AH, Hammer J, Newth CJ. Effect of prone and supine positions on functional residual capacity, oxygenation, and respiratory mechanics in ventilated infants and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(4 Pt 1):1185–1189. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.9601042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casado-Flores J, Martinez de Azagra A, Ruiz-Lopez MJ, Ruiz M, Serrano A. Pediatric ARDS: effect of supine-prone postural changes on oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1792–1796. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridrich P, Krafft P, Hochleuthner H, Mauritz W. The effects of long-term prone positioning in patients with trauma-induced adult respiratory distress syndrome. Anesth Analg. 1996;83(6):1206–1211. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199612000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broccard AFSR, Schmitz LL, Ravenscraft SA, Marini JJ. Influence of prone position on the extent and distribution of lung injury in a high tidal volume oleic acid model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(1):16–27. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randolph AG, Meert KL, O’Neil ME, et al. The feasibility of conducting clinical trials in infants and children with acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(10):1334–1340. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1175OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gattinoni L, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, et al. Effect of prone positioning on the survival of patients with acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):568–573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerin C, Gaillard S, Lemasson S, et al. Effects of systematic prone positioning in hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2379–2387. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curley MAQ, Fackler JC. Weaning from mechanical ventilation: patterns in young children recovering from acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(5):335–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatrics. 1992;121(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollack M, Patel K, Ruttimann U. The pediatric risk of mortality III-- Acute physiology score (PRISM III-APS): A method of assessing physiologic instability for pediatric intensive care unit patients. J Pediatrics. 1997;131(4):575–581. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curley MAQ. Prone positioning of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8(6):397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR, Network ARDS. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1772–1777. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leteurtre S, Martinot A, Duhamel A, et al. Validation of the paediatric logistic organ dysfunction (PELOD) score: prospective, observational, multicentre study. Lancet. 2003;362(9379):192–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien P, Fleming T. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panel NPUA. Stage I Assessment in Darkly Pigmented Skin. Available at: http://www.npuap.org/positn4.html

- 27.Panel NPUA. Pressure ulcers prevalence, cost and risk assessment: consensus development conference statement. Decubitus. 1989;2(2):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papastamelos C, Panitch HB, England SE, Allen JL. Developmental changes in chest wall compliance in infancy and early childhood. J Applied Physiology. 1995;78(1):179–184. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):327–336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor RW, Zimmerman JL, Dellinger RP, et al. Low-dose inhaled nitric oxide in patients with acute lung injury: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1603–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spragg RG, Lewis JF, Walmrath HD, et al. Effect of recombinant surfactant protein C-based surfactant on the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:884–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plotz FB, Slutsky AS, van Vught AJ, Heijnen CJ. Ventilator-induced lung injury and multiple system organ failure: a critical review of facts and hypotheses. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(10):1865–1872. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curley MAQ, Zimmerman JJ. Alternative outcome measures for pediatric clinical sepsis trials. Pediatric Crit Care Med. 2005;6(3 supplement):S150–S156. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161582.63265.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gattinoni L, Pelosi P, Suter PM, Pedoto A, Vercesi P, Lissoni A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease. Different syndromes? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(1):3–11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9708031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randolph AG, Wypij D, Venkataraman ST, et al. Effect of mechanical ventilator weaning protocols on respiratory outcomes in infants and children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(20):2561–2568. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]