Abstract

IL-18 is a unique cytokine that exerts both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects depending on the surrounding environments. Excessive inflammation in the feto-maternal interface is thought to result in the onset of miscarriage and preterm birth, but much is unknown about the function of IL-18 in pregnancy. Here, we report the protective role of IL-18 in pregnancy using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced murine miscarriage models. Whereas a low dose (1 µg) of LPS injection in pregnant mice did not induce miscarriages, the additional injection of anti-IL-18 neutralizing antibody (IL-18 nAb) resulted in a significant increase in abortion rates among the pregnant mice. Under these conditions, multiple T-cell subsets and natural killer cells produced significantly lower levels of the type 1 cytokine IFN-γ and the type 2 cytokine IL-4. The miscarriage induced by the low-dose LPS along with the IL-18 nAb was improved by the supplementation of IFN-γ and IL-4. Furthermore, the main source of IL-18 production was found to be the myometrium rather than macrophages. These results indicated that IL-18, which was initially thought to have a harmful effect on the maintenance of pregnancy, has a protective role in miscarriage against minor stimulation by pathogens with modulating immune homeostasis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-16546-9.

Keywords: IL-18, Inflammation, Miscarriage, Myometrium, Preterm birth

Subject terms: Intrauterine growth, Cytokines, Inflammation, Immunology

Introduction

Preterm birth (PB) is a major pregnancy complication. Approximately 11% of neonates worldwide are born prematurely (< 37 gestational weeks). This is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality1. PB leads to long-term complications, such as developmental disabilities, and pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases; 35% of neonatal deaths are directly attributable to PB2. Microbial infection is considered to be closely associated with the onset of PB3–5. Most of these pathological conditions are thought to be primarily subclinical infections, with ascending infection from the vagina leading to intra-amniotic infection. Indeed, when such ascending infections spread to the uterus, excessive infiltration of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, occurs in the placenta, leading to the development of histological chorioamnionitis (CAM)5,6. CAM has been extensively studied as a significant risk factor for PB in the field of obstetrics and gynecology. Therefore, bacterial vaginosis is also a risk for intrauterine infection and PB7. In bacterial vaginosis, the normal flora is disturbed, with an elevation in the numbers of causative organisms such as Gardnerella and Mycoplasma and a decrease in Lactobacillus.

The invading microorganisms are primarily bacteria: Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus agalactiae, Fusobacterium, and Gardnerella vaginalis8,9. The pathogen-associated molecular patterns derived from these bacteria are sensed by host pattern recognition receptors, inducing the activation of the immune system and a subsequent inflammatory environment within the amniotic cavity. This immune response consists of inflammatory cytokines released from surrounding fetal tissues and infiltrating immune cells10,11.

Although these bacteria and the imbalance of the bacterial flora are associated with the onset of PB, the causative organism is unknown in more than half of cases12. In fact, clinical practice shows that not all pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis develop PB. More interestingly, pregnancies are maintained successfully even when the endometrial microbiota in the uterus are disrupted13. These findings indicated that some complex mechanisms may exist between microbial infection and the onset of PB.

Excessive inflammatory cytokine production provokes a variety of pregnancy complications. Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)−1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, chemokines such as IL-8, and inflammatory mediators are produced systemically or locally during infection, and excessive inflammation is induced in the feto-maternal interface leading to PB14–16. Among these, the inflammatory cytokine IL-18 was first identified in 1995 and is classified as a member of the IL-1 superfamily, which also includes IL-1β17. It exists intracellularly as an inactive precursor (pro-IL-18) and is cleaved by caspase-1 via the inflammasome to become the active form, which is released outside the cell. Interestingly, IL-18 has plastic properties: one role as a helper T (Th)1 cytokine inducing interferon (IFN)-γ production and another as a Th2 cytokine inducing IL-4 production, depending on the surrounding milieu18. In the field of reproductive immunology, the balance between Th1 and Th2 immune responses is known to play a crucial role19–21. While the maintenance of the semi-allogeneic fetus generally requires a Th2-biased immune state and enhanced regulatory T cell function, certain physiological stages—such as implantation, placental development, late gestation (onset of labor), and responses to pathogenic infection—demand an appropriate level of Th1 or Th17-type of inflammation10. Therefore, analyzing Th1/Th2 dynamics during pregnancy is essential for understanding immune regulation in reproduction. As mentioned above, IL-18 has both Th1 and Th2 functions; however, there have been very few reports on its role in relation to miscarriage or preterm birth22,23. It also remains unknown whether IL-18 exerts a harmful or beneficial effects on the maintenance of pregnancy.

In this study, we investigated the role of IL-18 during pregnancy using a murine miscarriage model induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Although IL-18 is classically recognized as a pro-inflammatory cytokine, our findings revealed its unexpected protective role against LPS-induced miscarriage. These results provide new insights into the immune mechanisms involved in host defense during pregnancy. Notably, many previous studies have reported that LPS administration induces strong placental inflammation and miscarriage in mice, supporting the validity of this experimental model24–26. Importantly, this study utilized a murine miscarriage model to simulate infection-driven inflammation in feto-maternal interface relevant to human preterm birth. In human pregnancies, early miscarriages are predominantly caused by chromosomal abnormalities and were not the focus of our investigation. Instead, we aimed to understand inflammation in feto-maternal interface, a hallmark of infection-associated preterm birth and late miscarriage. For these reasons, we selected a miscarriage model to more accurately examine immune responses in feto-maternal interface that may underlie infection-associated preterm birth in humans.

Results

Neutralizing IL-18 exacerbates miscarriage in mice injected with low-dose LPS

Initially, to determine the effects of LPS administration on pregnant mice, abortion rates were evaluated for LPS treatment. Pregnant mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 µg/mouse or 2 µg/mouse of LPS on Gd 8.5; mice were sacrificed, and the abortion rates were evaluated on Gd 13.5. The experimental scheme is shown in Fig. 1A and B. Spontaneous miscarriage rarely occurred in the control mice, but nearly half of the mice injected with 2 µg of LPS experienced miscarriage (Fig. 1C). Conversely, the abortion rate with lower dose LPS (1 µg) was so low that it was not significantly different from that without LPS. (Fig. 1C). It is known that LPS administration in pregnant mice produces various inflammatory cytokines27–29. Therefore, we investigated whether the production of IL-18, one of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, was also induced by LPS. We found that, whereas 1 µg of LPS injection increased serum IL-18 levels in both non-pregnant and pregnant mice on gestational day (Gd) 8.5, the pregnant mice exhibited significantly higher IL-18 levels than the non-pregnant mice (Fig. 1D). Conversely, IL-18 was not detected in the serum of pregnant mice without the LPS injection. These results suggested that IL-18 is more likely to regulate inflammation in pregnancy. Interestingly, we did not observe a significant increase in IL-18 levels in pregnant mice injected with 2 µg of LPS injection (Fig. 1D, right lane). Although serum levels do not always reflect the local placental environment, this result may suggest that IL-18 is not the main factor responsible for inducing severe inflammation leading to miscarriage. To elucidate the effects of IL-18 in LPS-treated pregnant mice, pregnant mice were injected intraperitoneally with LPS along with an anti-IL-18 neutralizing antibody (IL-18 nAb) or an isotype control IgG on Gd 2.5, 5.5, 8.5, and 11.5, as shown in Fig. 1B. Unexpectedly, the administration of 1 µg of LPS along with IL-18 nAb resulted in significantly higher abortion rates than that of 1 µg of LPS alone (Fig. 1C, right lane). Macroscopic and histological findings following LPS and IL-18 nAb administration are shown in Supplemental Fig. S1. In the group treated with LPS (1 µg) and IL-18nAb, marked embryonic degeneration was observed macroscopically (Supplemental Fig. S1A, lower panel). H&E staining also revealed extensive necrotic areas with several cell infiltration in the placenta (Supplemental Fig. S1B, lower panel). Administration of IL-18 nAb alone did not induce miscarriage (Fig. 1C, second lane from left). These findings suggest that IL-18 exerts a protective effect against degeneration of the feto-maternal interface and miscarriage induced by low-dose LPS administration.

Fig. 1.

Neutralizing IL-18 facilitates miscarriage in mice injected with low-dose LPS. (A) Schematic representation of the LPS administration to pregnant mice. (B) Schematic representation of the LPS and IL-18 nAb administration to pregnant mice. (C) Abortion rate evaluated on Gd 13.5. n = 17 for IL-18 nAb (-), LPS (-); n = 23 for IL-18 nAb (+), LPS (-); n = 11 for IL-18 nAb (-), LPS 2 µg/body; n = 13 for IL-18 nAb (-), LPS 1 µg/body; n = 12 for IL-18 nAb (+), LPS 1 µg/body. (D) Pregnant and non-pregnant mice were administered LPS intraperitoneally on Gd 8.5 and 24 h later, the serum concentrations of IL-18 were determined. N = 4 for pregnant (-), LPS (-); n = 4 for pregnant (+), LPS (-); n = 4 for pregnant (-), LPS (+); n = 4 for pregnant (+), LPS (+). ***p < 0 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA analysis followed by the Turkey’s post hoc test. Gd, gestational day; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IL-18 nAb, anti-IL-18 neutralizing antibody; ns, not significant.

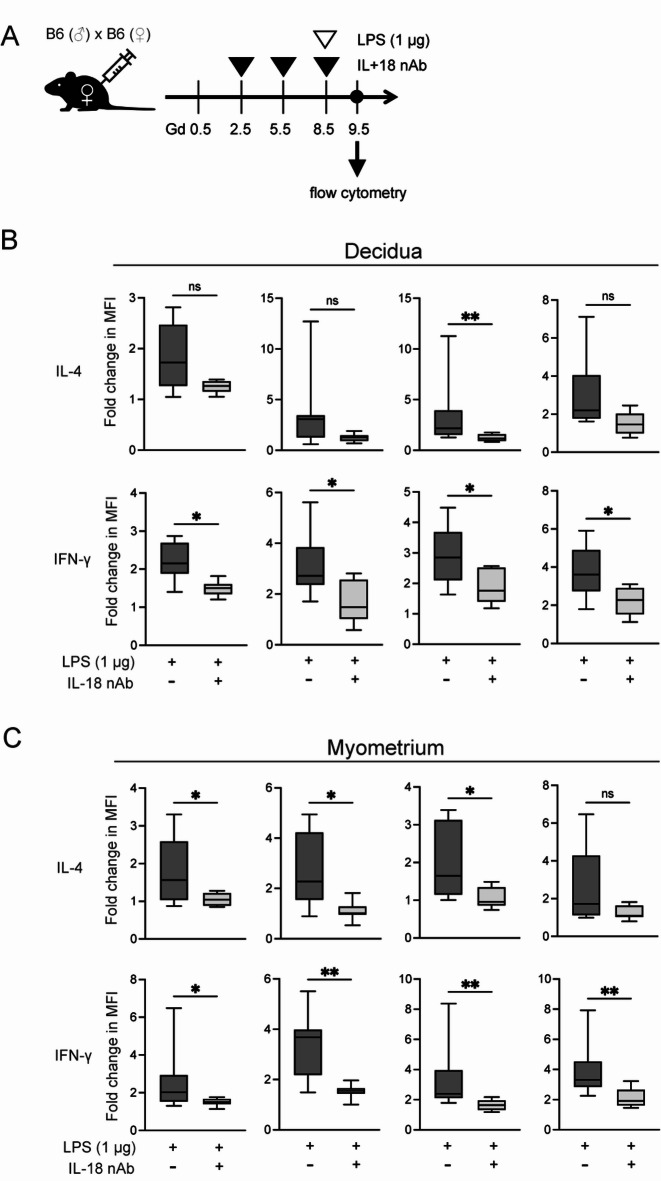

Neutralizing IL-18 decreases IFN-γ and IL-4 production in the myometrium and the decidua

As previously described, appropriate Th1/Th2 balance is crucial for a successful pregnancy. In reproductive immunology, various cytokines have been examined to evaluate this balance during pregnancy. Among them, the IFN-γ/IL-4 ratio has been frequently used in both murine models and human clinical samples to assess the Th1/Th2 immune state30–33. Based on this background, we aimed to investigate IFN-γ and IL-4 production in pregnant mice. Here, intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ production were measured by flow cytometry after peritoneal injection of 1 µg of LPS with or without IL-18 nAb, as shown in Fig. 2A. As mentioned above, LPS was administered on Gd 8.5, and miscarriage was evaluated on Gd 13.5. However, since the immune responses and cytokine changes that trigger excessive inflammation were expected to occur earlier, immune cell and cytokine analyses described below were performed on Gd 9.5. In fact, when miscarriage occurs (Gd 13.5), the embryo often degenerates into a small hematoma, making it difficult to isolate the decidua. The full gating strategy was shown in Supplemental Fig. S2. We found that treatment with the IL-18 nAb tended to decrease the production of IL-4 and IFN-γ from natural killer (NK) cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells in the decidua (Fig. 2B). Conversely, the myometrium exhibited more prominent patterns than the decidua (Fig. 2C). These results suggested that the administration of IL-18 nAb to LPS-treated mice causes suppression of cytokine production from the myometrium rather than from the decidua.

Fig. 2.

Neutralizing IL-18 decreases IFN-γ and IL-4 production in the myometrium and the decidua. (A) Schematic representation of low-dose LPS (1 µg) and IL-18 nAb administration to pregnant mice. (B, C) Flow cytometric analysis of intercellular IL-4 and IFN-γ production in the indicated immune cells in the decidua (B) and myometrium (C) of pregnant mice at Gd 9.5. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U-test. Gd, gestational day; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ns, not significant.

Neutralizing IL-18 canceled STAT1 and STAT6 activation induced by low-dose LPS administration

To investigate whether the reduction in IFN-γ and IL-4 production caused by IL-18 neutralization indirectly affected their downstream signaling, we conducted immunofluorescence staining of the myometrium and the decidua to detect phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1) and STAT6 (pSTAT6), which are known downstream mediators of IFN-γ and IL-4 signaling, respectively. Although STAT1 and STAT6 are not direct components of IL-18 signaling, we hypothesized that modulating IL-18 activity may influence the activation of these pathways through its regulatory effects on IFN-γ and IL-4 expression. pSTAT1 or pSTAT6 was hardly observed in normal pregnant mice at Gd 9.5 (Fig. 3A, upper lane). Conversely, mice injected with 1 µg of LPS exhibited mainly both pSTAT1+ cells and pSTAT1+pSTAT6+ cells in the decidua and myometrium (Fig. 3A, middle lane). As expected, IL-18 nAb administration decreased the pSTAT1 and pSTAT6 signals (Fig. 3A, lower lane). We quantified the expression of pSTAT1 and pSTAT6 in the decidua and myometrium based on the results of immunofluorescence staining. In the mice injected with LPS alone, the percentages of pSTAT1+ cells in decidua were higher than that in the myometrium (Fig. 3B, upper lane). By contrast, the percentages of pSTAT1+pSTAT6+ cells in the myometrium were higher than that in the decidua. Few pSTAT6+ cells were found in the decidua and myometrium. These results indicated that the IFNγ–pSTAT1 and IL-4–pSTAT6 axes had different proportions depending on tissue differences, decidua and myometrium. More interestingly, the administration of IL-18 nAb canceled all these differences, and pSTAT1-positive and pSTAT6-positive cells almost disappeared from the decidua and the myometrium (Fig. 3B, lower lane). This result indicated that pSTAT1 and pSTAT6 expression, which are downstream signaling for IFN-γ and IL-4, were downregulated by treatment with IL-18 nAb. These findings were consistent with the results that treatment with IL-18 nAb suppressed IFN-γ and IL-4 production from immune cells in the decidua and myometrium (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Neutralizing IL-18 canceled STAT1 and STAT6 activation induced by low-dose LPS administration. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of decidua and myometrium on Gd 9.5. The samples were prepared as shown in Fig. 2A. Upper lane, LPS (−) and IL-18 nAb (−); middle lane, LPS (+) and IL-18 nAb (−); lower lane, LPS (+) and IL-18 nAb (+). The dotted lines indicate the border between the decidua (dec) and the myometrium (myo). Blue indicated DAPI, green indicates pSTAT6, and red indicated pSTAT1. White bar, 50 μm. (B) Percentage of pSTAT1-positive and pSTAT6-positive cells in the decidua and myometrium. ****p < 0.0001; Mann–Whitney U-test. Gd, gestational day; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Furthermore, we also investigated which specific cell types serve as targets of IFN-γ and IL-4 by examining the co-localization of p-STAT1 and p-STAT6 with immune cell marker, CD3ε and NK1.1 (Supplemental Fig. S3). We found that a subset of CD3ε-positive cells expressed p-STAT1 and p-STAT6. Additionally, some NK1.1-positive cells also showed positivity for p-STAT1 and p-STAT6. Given that CD3ε-positive cells include various subtypes such as CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells, and NK1.1-positive cells encompass both NK and NKT cells, the observed heterogeneity in phosphorylation patterns likely reflects these distinct immune cell subsets. Moreover, as shown in Supplemental Fig. S3, p-STAT1 and p-STAT6 expression was also observed in other cells not marked by CD3ε or NK1.1, which are likely non-immune cells such as decidual stromal or interstitial cells. These findings suggest that IFN-γ and IL-4 may target not only immune cells but also maternal non-immune cells in the decidua and myometrium.

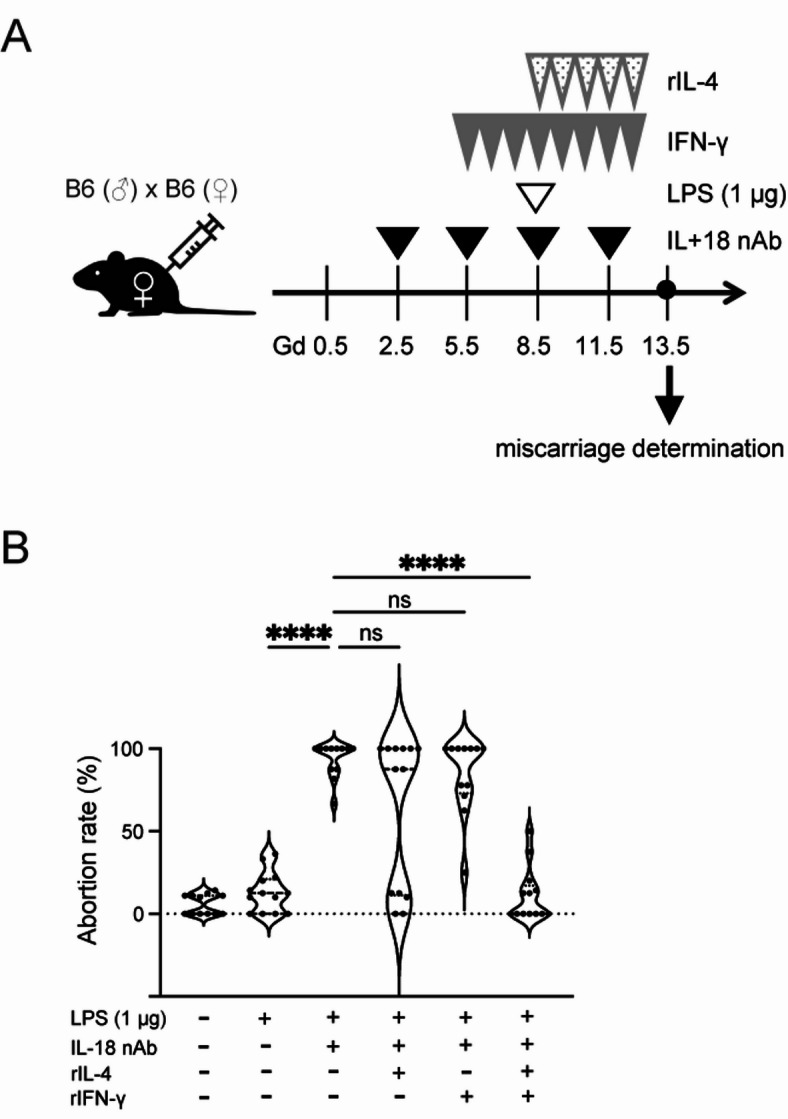

Combination therapy of IFN-γ and IL-4 improves miscarriage of LPS and IL-18 nAb treated mice

We observed that, compared with LPS injection alone, the additional treatment with IL-18 nAb induced a significantly higher rate of miscarriage as well as a reduction in IFN-γ and IL-4 production from immune cells.

Therefore, supplementation therapy was examined to investigate whether both IFN-γ and IL-4, or alone, were associated with miscarriage. The experimental scheme is shown in Fig. 4A. In mouse pregnancy, it is considered that the implantation occurs around Gd 5, which corresponds to approximately week 2 of gestation in humans. By around Gd 10, the basic placental structure is established, corresponding to approximately week 14 of gestation in humans. Previous studies have reported that IFN-γ plays an important role in placental development34,35. Based on these findings, we administered IFN-γ prior to IL-4 in this study, aiming to support normal placental formation. Although only some miscarriages were averted by supplementation with IL-4 alone or IFN-γ alone, there were no statistical differences in abortion rate compared with the mice treated with LPS and IL-18 nAb (Fig. 4B). However, combination therapy with IL-4 and IFN-γ produced a marked improvement in the abortion rate (Fig. 4B, rightmost rows), indicating that both IFN-γ and IL-4 were necessary for the prevention of miscarriages. These results indicated that the appropriate levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ may have a protective role against murine miscarriage induced by the administration of small doses of LPS.

Fig. 4.

Injection of IL-4 and IFN-γ improves LPS-induced miscarriage. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. Recombinant (r)IFNγ was administered daily from Gd 5.5 and rIL-4 from Gd 8.5 until Gd 12.5. (B) Abortion rate was evaluated at 13.5. n = 12 for LPS (-), IL-18 nAb (-), rIL-4 (-), rIFN-γ (-); n = 12 for LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-), rIL-4 (-), rIFN-γ (-); n = 12 for LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (+), rIL-4 (-), rIFN-γ (-); n = 13 for LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (+), rIL-4 (+), rIFN-γ (-); n = 12 for LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (+), rIL-4 (-), rIFN-γ (+); n = 13 for LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (+), rIL-4 (+), rIFN-γ (+) ****p < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Turkey’s post hoc test. Gd, gestational day; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

IL-18 is produced by uterine smooth muscle

Macrophages are known to be the main source of IL-1817. Therefore, we established conditional knockout mice that lacked macrophage-derived IL-18 (Il18fl/fl;LysM-cre) and administered 1 µg of LPS to verify the abortion rate. The experimental scheme is shown in Fig. 5A. In the Il18fl/fl;LysM-cre mice injected with 1 µg of LPS, miscarriages occurred only partially; however, there were no statistical difference compared with Il18fl/fl mice injected with 1 µg of LPS (Fig. 5B, third and fourth rows from left). Therefore, we speculated that IL-18, which is necessary for the prevention of miscarriage, may be produced by other sources than macrophages. Hence, we examined pro- and mature IL-18 production in the murine placenta, decidua, and myometrium on Gd 16.5 using western blotting. Because the placenta, decidua, and myometrium can be relatively clearly separated at Gd16.5, we selected this time point for tissue-specific analysis. Interestingly, we found that the myometrium was also a potent source of IL-18 production (Fig. 5C). Immunofluorescence staining with αSMA, reflecting smooth muscle cells, and IL-18 revealed that IL-18-positive cells generally overlapped with αSMA-positive cells. In addition, IL-18 expression was observed broadly throughout the entire myometrial layer (Fig. 5D). Therefore, uterine smooth muscle cells were thought to produce IL-18. Next, we established uterine smooth muscle cell-specific Il18-deficient mice (Il18fl/fl;Sm22a-cre) and administered 1 µg of LPS to verify the abortion rate. The experimental schema is shown in (Fig. 5E). We found a marked abortion rate in Il18fl/fl;Sm22a-cre mice injected with 1 µg of LPS, and that the abortion rates of these mice were significantly higher than that of Il18fl/fl mice injected with 1 µg of LPS (Fig. 5F, third and fourth rows from left). These results suggested that IL-18 produced by uterine smooth muscle cells may have a greater contribution to miscarriage than from macrophages.

Fig. 5.

IL-18 is also produced by uterine smooth muscle. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. (B) Macrophage-specific Il18-deficient pregnant mice (Il18fl/fl;LysM-cre) were injected with 1 µg of LPS and the abortion rate was evaluated on Gd 13.5. n = 13 for Il18+/+, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-); n = 12 for Il18+/+, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (+); n = 12 for Il18fl/fl, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-); n = 18 for Il18fl/fl;LysM-cre, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-). ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Turkey’s post hoc test. (C) Production of pro- and mature IL-18 in the myometrium, decidua, and placenta on Gd 16.5 was measured by western blotting. (D) Confocal images of the myometrium and decidua. The decidua is located at the bottom left of the upper images. Green indicates αSMA and magenta indicates IL-18. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 34,580. The lower images show the area enclosed by the square in the upper images. White bar, 50 μm. (E) Schematic representation of the experimental setup. (F) Smooth muscle-specific Il18-deficient pregnant mice (Il18fl/fl;Sm22a-cre) were injected with 1 µg of LPS and the abortion rate was evaluated using Gd 13.5. n = 13 for Il18+/+, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-); n = 11 for Il18+/+, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (+); n = 14 for Il18fl/fl, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-); n = 26 for Il18fl/fl;Sm22a-cre, LPS (+), IL-18 nAb (-) **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Turkey’s post hoc test.

Discussion

This study showed that the administration of neutralizing antibodies against IL-18 induced murine miscarriages, even with small doses of LPS. Uterine smooth muscle cells were also a major source of IL-18, and IL-18 stimulated appropriate levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ production. These results indicated that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-18, which was expected to have a negative effect on pregnancy progress, had protective roles against reproductive failure.

In general, many pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria are present in the vagina. It has been shown that endometrial microbiota are also found in the uterine cavity36,37. These findings indicated that the fetus and placenta are always potentially open to attack from a variety of bacteria. In the present study, we showed that IL-18 protected against murine miscarriage from minor pathogen stimulation (i.e., small doses of LPS). We speculate that IL-18 may protect the fetus from minor infections in the vagina and uterine cavity in human pregnancy. Indeed, the presence of pathogenic bacteria and dysbiosis in the vagina or uterus did not necessarily cause miscarriage or PB13. We hypothesize that reduced IL-18 production, as well as the presence of pathogens, may be a factor in miscarriages and PB caused by bacterial infections.

Inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α, have been reported to be harmful during pregnancy15,16,38. We initially hypothesized that IL-18, as found for IL-1β, had a harmful effect on pregnancy progression by inducing Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ in the inflammatory environment following LPS administration. However, we found that the administration of neutralizing antibodies against IL-18 reduced the production of both IFN-γ and IL-4 cytokines, leading to murine miscarriage following the administration of small doses of LPS. This result indicated that both IFN-γ and IL-4 cytokines were crucial in pregnancy for protection from pathogens. Previous reports have shown that IFN-γ is required for placental vascular remodeling, which may be strongly associated with the maintenance of placental function34,35,39. In addition, in an in vivo and in vitro study (manuscript in preparation), our group found that IL-18 and IFN-γ were important for the placental formation and fetal development. As for IL-4, it may also suppress excessive Th1 deflection during infection as previous reports have shown a suppressive effect on LPS-induced inflammation40,41. In addition, there have been reports of angiogenesis-promoting effects of IL-1842,43. These findings suggested that IL-18, together with IFN-γ and IL-4, may be important for pregnancy maintenance.

Although excessive inflammation is considered a great concern for pregnancy complications, such as repeated implantation failure, repeated pregnancy loss, PB, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy44–48, the necessary level of inflammation, particularly in early pregnancy, has recently been reported. In humans, the development of uterine receptivity necessitates pro-inflammatory responses such as the release of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α49–51. Increased levels of IL-12, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and NO under an M1 macrophage-dominated environment promote embryo attachment to the decidua52. Th1 cytokines, such as IFN-γ, are now thought to have an important role in placentation53. In clinical cases, the IL-18/TWEAK (tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis) ratio is sometimes used for patients who demonstrate repeated implantation failure54,55. This endometrial biomarker reflects angiogenesis and the Th1/Th2 balance before implantation. It is noted that the IL-18/TWEAK ratio is a target for treatment, not only when it is high, the hyper-immune activation state, but also when it is low, the hypo-immune activation state. These findings suggested that an appropriate Th1-type response was also sometimes necessary for successful pregnancy progression. In addition, inflammatory responses are necessary to eliminate pathogens during infection. Thus, we believe that, not only the anti-inflammatory environment but also factors that regulate “appropriate inflammation,” such as IL-18, are very important in maintaining pregnancy.

Although macrophages are generally known to be the main source of IL-1817, we found that smooth muscle was also a main source of IL-18 during pregnancy. This suggested that abnormal IL-18 production may occur in the presence of diseases with abnormalities in the myometrium, such as uterine myoma and adenomyosis. Several studies have revealed that patients with uterine myoma and adenomyosis were associated with many obstetric complications including PB, fetal growth restriction, placental malposition, and preeclampsia56–60. Following these findings and our current results, in future studies we will investigate IL-18 production, including its binding protein and receptor, in tissues obtained from the patients with uterine myoma and adenomyosis. Furthermore, we will conduct animal experiments using a mouse model of uterine adenomyosis.

It is unclear what triggers IL-18 production during pregnancy. Based on the report that NLRP3 activation is required for LPS-induced preterm labor61, it was assumed that the induction of IL-18 was via the inflammasome canonical pathway. However, our result showed that IL-18 was homeostatically produced in the pregnant myometrium without LPS stimulation (Fig. 5C, D). In addition, we found higher serum IL-18 levels in pregnant mice compared with non-pregnant mice injected with LPS (Fig. 1). These results indicated that pregnancy itself tends to increase IL-18 production. Based on our conditional knockout experiments, IL-18 produced by myometrial smooth muscle cells appears to play a crucial role in pregnancy maintenance. We hypothesize that its production may be regulated by mechanical stress in the myometrium—such as uterine expansion during pregnancy or contractions during labor. To explore this further, we are planning an omics-based comprehensive analysis of cytokine expression and signaling pathways in the myometrium. In addition, we intend to perform in vivo experiments to clarify the functional consequences of these molecular changes. These future studies will not only deepen our understanding of IL-18 regulation in the myometrium but may also help elucidate the broader mechanisms linking uterine inflammation to pregnancy outcomes.

One limitation of this study is the use of a syngeneic mating combination in pregnant mice. This decision was based on the fact that allogeneic combinations involve complex immune responses such as alloantigen-specific tolerance or rejection, which can complicate the interpretation of LPS-induced responses and cytokine changes. To clearly analyze the relationship between LPS-induced inflammation and miscarriage, we adopted a syngeneic mating model with a uniform immunological background. However, since all human pregnancies are allogeneic by nature, future studies using allogeneic mouse models and analyses of human clinical samples will be necessary. Another limitation of this study is that the murine miscarriage model employed—based on intraperitoneal LPS injection—does not fully replicate the clinical features of human bacterial vaginosis. In human pregnancy, bacterial vaginosis-associated pathogens ascend from the lower genital tract to the uterus, leading to intrauterine infection and CAM. Although intraperitoneal LPS injection in mice is a widely used method to induce placental inflammation25,26, it does not perfectly mimic the ascending route of infection observed in humans. To better reflect the pathophysiology of bacterial vaginosis and its progression to CAM, future studies utilizing transvaginal LPS administration or vaginal infection models may be warranted.

In conclusion, we have shown that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-18, produced mainly by the myometrium, promotes appropriate levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 production and prevents miscarriage from the administration of small doses of LPS. It will be necessary to analyze the dynamics of IL-18 in the tissues obtained from the patients with uterine abnormalities, uterine myoma and adenomyosis in future. These investigations may provide clues to the elucidation of the mechanisms that cause pregnancy complications such as miscarriage, PB, and fetal growth restriction in these diseases.

Conclusion

We have shown that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-18, produced mainly by the myometrium, promotes appropriate levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 production and prevents miscarriage following the administration of small doses of LPS. It will be necessary to analyze the dynamics of IL-18 in the tissues obtained from the patients with uterine abnormalities, uterine myoma and adenomyosis in future. These investigations may provide clues to the elucidation of mechanisms that cause pregnancy complications such as miscarriage, PB, and fetal growth restriction in these diseases.

Methods

Mice

Female and male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Nippon Bio-Supp. Center. LysM-cre (strain: IMSR_JAX:004781) and Sm22a-cre (strain: IMSR_JAX:017491) mice were on a C57BL/6 background and were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (ME, USA). Il18fl/fl mice were bred with C57/B6-LysM-cre mice to generate macrophage-specific Il18-deficient mice (Il18fl/fl;LysM-cre)62. Smooth muscle-specific Il18-deficient mice (Il18fl/fl;Sm22a-cre) were also generated in a similar manner by crossing Il18fl/fl mice with C57/B6-Sm22a-cre mice. To validate tissue-specific deletion of IL-18, we performed immunofluorescence staining using uterine sections (Supplementary Fig. S4). In macrophage-specific Il18-deficient mice, IL-18 expression was preserved in the myometrium but absent in the decidua, consistent with deletion in LysM-expressing macrophages. In contrast, in smooth muscle-specific Il18-deficient mice, IL-18–positive cells were still observed in parts of the decidua, although not in the myometrium. The validation confirmed the genotypes and tissue-specific IL-18 deletion, supporting the suitability of these mice for subsequent experiments.

Portions of the tails from macrophage-specific Il18-deficient mice (Il18fl/fl;LysM-Cre) and smooth muscle-specific Il18-deficient mice (Il18fl/fl;Sm22a-Cre) were harvested and lysed for genomic DNA extraction. Genotyping was performed by PCR to detect the presence of floxed Il18 alleles and Cre recombinase transgenes. PCR products were separated by size using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Primer sequences used for genotyping are provided in Table S1.

Male mice (8–20 weeks old) and female mice (8–12 weeks old) were used for mating. The day on which a vaginal plug was observed was designated as gestational day (Gd) 0.5. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of Nippon Medical School. Euthanasia of the mice was performed by cervical dislocation conducted by the trained researchers.

All animal experiments were carried out according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals issued by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and all murine experiments were conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by the President of Nippon Medical School (appr. No. 2020-053). The study methods were performed and reported in line with the ARRIVE guidelines.

LPS-induced murine miscarriage

Virgin female B6 mice (8–12 weeks) were mated with syngeneic males. The pregnant mice were administered LPS 1–2 µg/body intraperitoneally (LPS-EB Ultrapure, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) on Gd 8.5. Some pregnant mice were administered IL-18 nAb on Gd 2.5, 5.5, 8.5, and 11.5. Each mouse was euthanized on Gd 13.5 and determined whether they had miscarried. Miscarriage was identified by macroscopic examination of the uterus, with resorbed embryos appearing as small, dark structures. The miscarriage rate (%) was calculated by dividing the number of resorbed embryos by the total number of embryos and multiplying by 100. Representative macroscopic images of the uterus are provided in Supplemental Fig. S1. The myometrium and decidua were obtained from pregnant mice. Macrophage-specific Il18-deficient female mice and smooth muscle-specific Il18-deficient female mice were also mated in the same manner, and were administered with recombinant cytokines by abdominal injection.

Recombinant cytokine-injected mouse

Virgin female B6 mice (8–12 weeks) were mated with syngeneic males. The pregnant mice were administered LPS 1 µg/body intraperitoneally on Gd 8.5 and IL-18 nAb on Gd 2.5, 5.5, 8.5, and 11.5. For some experiments, pregnant mice were injected intraperitoneally with recombinant IFN-γ (485-ML-100/CF, R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) 0.01 µg/body from Gd 5.5 to 12.5 and recombinant IL-4 (404-ML-010/CF, R&D Systems Inc.) 1 µg/body from Gd 8.5 to 12.5. Miscarriages were determined at Gd 13.5.

ELISA

IL-18 concentrations in serum were determined using a mouse IL-18 ELISA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting analysis

Each sample of uterine smooth muscle, desmoplastic membrane, and placenta was frozen in liquid nitrogen, crushed, and lysed in sample buffer (50 mM HEPES/KOH, 250 mM NaCl, 1.5 M MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40). Whole tissue lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membrane was probed with anti-mouse IL-18 Ab (ab207323, clone: EPR19956, Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG polyclonal Ab (#115-035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) and then visualized with Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan). Images were obtained using LiminoGraph Ⅰ (ATTO Corporation), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence tissue staining

Pregnant mice were laparotomized; bilateral ovarian arterioles and uterine arteries were ligated. Tissues were fixed by immersion in 10% formaldehyde Neutral Buffer Solution (Nacalai tesque) for 1 week. The whole uterus was cut into pieces per embryo size, paraffin-embedded, sliced at 4-µm thickness, attached to glass slides (CREST CRE-13, MATSUNAMI, Osaka, Japan), and then allowed to dry for 24 h. Sections were deparaffinized by immersion in xylene for 15 min, hydrophilized with ethanol, and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS. Antigen retrieval was conducted in a 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) by heating using a microwave at 98 °C for 15 min. Samples were probed with anti-mouse phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1) antibody (#686401, A15158B, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and anti-mouse phosphorylated STAT6 (pSTAT6) antibody (ab263947, EPR22599-78, Abcam plc) overnight at 4℃ and then incubated with the following secondary antibodies: AlexaFluor (AF)555-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (A48287; Invitrogen) and AF488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (A48282; Invitrogen) for 60 min at room temperature. Nuclei were labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Nacalai tesque). Specimens were encapsulated in an antifade mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA) and then observed under a KEYENCE BZ-X710 fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan). To quantify the members of pSTAT1- and pSTAT6-positive cells, specimens were analyzed using the Mantra™ Quantitative Pathology Workstation (Akoya Biosciences, Marlborough, MA). Fluorescent signals and tissue autofluorescence were spectrally unmixed using an inForm® image analysis software (Akoya Biosciences), and signal-positive cells were determined through cell segmentation and phenotype analysis based on fluorescence intensity thresholds. Three areas of each specimen were randomly selected, and the numbers of pSTAT1- and pSTAT6-positive cells within the areas were counted automatically.

For some experiments, multiplex immunofluorescence staining was performed using the Opal™ 4-color IHC kit (Akoya Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating sections in a 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 min at 98 °C in a microwave oven. Sections were blocked for 10 min and then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in Opal Antibody Diluent. The following primary antibodies and corresponding Opal fluorophores were used: anti-CD3ε (#78588, Cell Signaling Technology, MA; 1:200) with Opal 570; anti-NK1.1 (#39197, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:200) with Opal 620; anti-pSTAT6 (#ab263947, Abcam; 1:500) with Opal 520; and anti-pSTAT1 (#686401, BioLegend; 1:100) with Opal 690. Each staining step included incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (included in the Opal kit) and tyramide signal amplification using Opal fluorophores diluted 1:200. After each staining cycle, the antigen retrieval procedure was repeated to remove antibodies while preserving the fluorescent signal. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and slides were mounted using ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (#P36961, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Images were obtained using spectral unmixing with the Mantra™ Quantitative Pathology Workstation and then analyzed using an inForm® image analysis software.

To investigate the expression of IL-18 and αSMA in the Gd 8.5 myometrium, decidua, and placenta, tissues were rapidly frozen in a frozen section compound (Surgipath FSC 22 blue, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and sliced to 7-µm thickness using a cryostat (Leica CM1860 UV, Leica Biosystems). Sections attached to glass slides were immersed in acetone for 5 min at 4 °C and then hydrophilized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 3 min at room temperature. After blocked with 3% goat serum in PBS for 1 h, sections were probed with anti-mouse IL-18 antibody (ab71495; Abcam plc) and anti-mouse αSMA antibody (NBP2-33006; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO.) overnight at 4℃, followed by AF555-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (A48283; Invitrogen) and AF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (A48286; Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature. Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst 34,580 (H21486; Invitrogen).

Images were obtained using a confocal laser scanning microscope LSM980 (ZEISS, Jena, Germany) and then analyzed using a ZEN software (ZEISS).

H&E staining

FFPE tissue sections were used for H&E staining. Placentas and decidua of pregnant mice at Gd 9.5 were analyzed. Images were obtained using a KEYENCE BZ-9000 microscope system (KEYENCE).

Flow cytometry

At 4 h prior to specimen collection, brefeldin A was injected abdominally into the subject mice. The usefulness of Brefeldin A administration for intracellular cytokine detection in vivo has been demonstrated in several studies63,64. We analyzed immune cells based on their surface marker expression in decidual, desmoplastic, and myometrial tissue. In addition, the intracellular cytokines of each immune cell were also analyzed. Each tissue was cut into small pieces and degraded using collagenase. After centrifugation of the mesh-filtered solution, mononuclear cells in the cellular component were isolated using Lympholyte (Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Dead cells were stained with Zombie dye (BioLegend) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After that, cells were stained with various surface markers to enable the identification of immune cell subsets. They were then fixed with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), permeabilized with Perm/Wash Buffer (BD Biosciences), and subsequently stained intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4. Stained cells were suspended in a FACS buffer. Data were acquired using an LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer with a FACSDiva software (version 8.0.1) and then analyzed using a FlowJo software (version 10.7.2) (BD Biosciences). All antibodies and their dilution factors used for flow cytometry analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

CD8+ T cells are defined as CD3+ and CD8+ cells; CD4+ cells as CD3+ and CD4+ cells; NK cells as CD3− and NK1.1+ cells; NKT cells as CD3+ and NK1.1+ cells; The gating strategies of these immune cells are shown in Supplemental Fig S2.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using a Prism software (version 9.1.0) (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine statistically significant differences between the two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey posttest was performed to compare more than two groups by one factor. Two-way ANOVA analysis followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to compare more than two groups by two factors. The statistically significant difference was set at p < 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Ms. Masumi Shimizu for technical assistance and all the staff of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Nippon Medical School Graduate School.

Abbreviations

- Gd

Gestational day

- IL

Interleukin

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

- NKT cells

Natural killer T cells

- PB

Preterm birth

Author contributions

YH, YN and RM designed the study; YH, HI, and YN performed the flow cytometry study; YH, HI, and EK performed the western blotting analysis and immunofluorescence staining. RF, RM, EK, and YH established the conditional knockout mice; YH, YN, SS, and RM participated in data interpretation; YH and YN wrote the first draft of the manuscript; YN and RM wrote the final version of the manuscript; SS and RM provided scientific insight and supervised the study. All authors revised the manuscript, approved the manuscript to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. YH, FS, MI, YK, and RO performed the Opal™ multiplex immunofluorescence staining. All authors revised the manuscript, approved the manuscript to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Initiative for Realizing Diversity in the Research Environment from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (Grant number 20K09679 to YN and 16H05178, 22K07140 to RM, and 22K11505 to FS), the Nippon Medical School Grant-in-Aid for Medical Research, the Naito Foundation, the Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, the Takeda Science Foundation, and the Terumo Life Science Foundation. the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research, the Kanzawa Medical Research Foundation, and the Seiichi Imai Memorial Foundation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yasuyuki Negishi, Email: negi@nms.ac.jp.

Rimpei Morita, Email: rimpei-morita@nms.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Blencowe, H. et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet379 (9832), 2162–2172 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blencowe, H. & Cousens, S. Addressing the challenge of neonatal mortality. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 18 (3), 303–312 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg, R. L. et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet371 (9606), 75–84 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McElrath, T. F. et al. Pregnancy disorders that lead to delivery before the 28th week of gestation: an epidemiologic approach to classification. Am. J. Epidemiol.168 (9), 980–989 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero, R. et al. The role of infection in preterm labour and delivery. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol.15 (Suppl 2), 41–56 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero, R. et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG113 (Suppl 3), 17–42 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitich, H. et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.189 (1), 139–147 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillier, S. L. et al. A case-control study of chorioamnionic infection and histologic chorioamnionitis in prematurity. N Engl. J. Med.319 (15), 972–978 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero, R. et al. Infection and labor. V. Prevalence, microbiology, and clinical significance of intraamniotic infection in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.161 (3), 817–824 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Negishi, Y. et al. Inflammation in preterm birth: novel mechanism of preterm birth associated with innate and acquired immunity. J. Reprod. Immunol.154, 103748 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negishi, Y. et al. Harmful and beneficial effects of inflammatory response on reproduction: sterile and pathogen-associated inflammation. Immunol. Med., 44 (2) 98–115. (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Yoneda, S. et al. Antibiotic therapy increases the risk of preterm birth in preterm labor without Intra-Amniotic microbes, but May prolong the gestation period in preterm labor with microbes, evaluated by rapid and High-Sensitive PCR system. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.75 (4), 440–450 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto, T. & Kyono, K. Does dysbiotic endometrium affect blastocyst implantation in IVF patients? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.36 (12), 2471–2479 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero, R. et al. Infection and labor. III. Interleukin-1: a signal for the onset of parturition. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.160 (5 Pt 1), 1117–1123 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero, R. et al. Interleukin-1 stimulates prostaglandin biosynthesis by human Amnion. Prostaglandins37 (1), 13–22 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Splichal, I. & Trebichavsky, I. Cytokines and other important inflammatory mediators in gestation and bacterial intraamniotic infections. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 46 (4), 345–351 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura, H. et al. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature378 (6552), 88–91 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakanishi, K. Unique action of Interleukin-18 on T cells and other immune cells. Front. Immunol.9, 763 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito, S. et al. Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.63 (6), 601–610 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaouat, G. et al. Immune suppression and Th1/Th2 balance in pregnancy revisited: a (very) personal tribute to Tom Wegmann. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.37 (6), 427–434 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wegmann, T. G. et al. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol. Today. 14 (7), 353–356 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lob, S. et al. The role of Interleukin-18 in recurrent early pregnancy loss. J. Reprod. Immunol.148, 103432 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tokmadzic, V. S. et al. IL-18 is present at the maternal-fetal interface and enhances cytotoxic activity of decidual lymphocytes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.48 (4), 191–200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, L. P. et al. Depletion of invariant NKT cells reduces inflammation-induced preterm delivery in mice. J. Immunol.188 (9), 4681–4689 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reginatto, M. W. et al. Effect of sublethal prenatal endotoxaemia on murine placental transport systems and lipid homeostasis. Front. Microbiol.12, 706499 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfson, M. L. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced murine embryonic resorption involves changes in endocannabinoid profiling and alters progesterone secretion and inflammatory response by a CB1-mediated fashion. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.411, 214–222 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fidel, P. L. Jr. et al. Systemic and local cytokine profiles in endotoxin-induced preterm parturition in mice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.170 (5 Pt 1), 1467–1475 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez-Lopez, N. et al. Intra-amniotic administration of lipopolysaccharide induces spontaneous preterm labor and birth in the absence of a body temperature change. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.31 (4), 439–446 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arenas-Hernandez, M. et al. Effector and activated T cells induce preterm labor and birth that is prevented by treatment with progesterone. J. Immunol.202 (9), 2585–2608 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng, Y., Yin, S. & Wang, M. Significance of the ratio interferon-γ/interleukin-4 in early diagnosis and immune mechanism of unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet.154 (1), 39–43 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, X. et al. The update Immune-Regulatory role of Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory cytokines in recurrent pregnancy losses. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(1), 132–162 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Nan, C. L. et al. Increased Th1/Th2 (IFN-gamma/IL-4) cytokine mRNA ratio of rat embryos in the pregnant mouse uterus. J. Reprod. Dev.53 (2), 219–228 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saito, S. et al. Distribution of Th1, Th2, and Th0 and the Th1/Th2 cell ratios in human peripheral and endometrial T cells. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.42 (4), 240–245 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimada, S. et al. No difference in natural killer or natural killer T-cell population, but aberrant T-helper cell population in the endometrium of women with repeated miscarriage. Hum. Reprod.19 (4), 1018–1024 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashkar, A. A., Di Santo, J. P. & Croy, B. A. Interferon gamma contributes to initiation of uterine vascular modification, decidual integrity, and uterine natural killer cell maturation during normal murine pregnancy. J. Exp. Med.192 (2), 259–270 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen, C. et al. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. Nat. Commun.8 (1), 875 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell, C. M. et al. Colonization of the upper genital tract by vaginal bacterial species in nonpregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.212 (5), 611e1–611e9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fortunato, S. J., Menon, R. & Lombardi, S. J. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the premature rupture of membranes and preterm labor pathways. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.187 (5), 1159–1162 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yockey, L. J. & Iwasaki, A. Interferons and Proinflammatory cytokines in pregnancy and fetal development. Immunity49 (3), 397–412 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bryant, A. H. et al. Interleukin 4 and Interleukin 13 downregulate the lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammatory response by human gestation-associated tissues. Biol. Reprod.96 (3), 576–586 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noble, A. & Kemeny, D. M. Interleukin-4 enhances interferon-gamma synthesis but inhibits development of interferon-gamma-producing cells. Immunology85 (3), 357–363 (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim, K. E. et al. Expression of ADAM33 is a novel regulatory mechanism in IL-18-secreted process in gastric cancer. J. Immunol.182 (6), 3548–3555 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park, C. C. et al. Evidence of IL-18 as a novel angiogenic mediator. J. Immunol.167 (3), 1644–1653 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christiaens, I. et al. Inflammatory processes in preterm and term parturition. J. Reprod. Immunol.79 (1), 50–57 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta, S. et al. Pathogenic mechanisms in endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertil. Steril.90 (2), 247–257 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laird, S. M. et al. A review of immune cells and molecules in women with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. Update. 9 (2), 163–174 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robillard, P. Y. et al. Epidemiological studies on primipaternity and immunology in preeclampsia–a statement after twelve years of workshops. J. Reprod. Immunol.89 (2), 104–117 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romero, R. et al. Inflammation in preterm and term labour and delivery. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med.11 (5), 317–326 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Granot, I., Gnainsky, Y. & Dekel, N. Endometrial inflammation and effect on implantation improvement and pregnancy outcome. Reproduction144 (6), 661–668 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mor, G. et al. Inflammation and pregnancy: the role of the immune system at the implantation site. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci.1221, 80–87 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Sinderen, M. et al. Preimplantation human blastocyst-endometrial interactions: the role of inflammatory mediators. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.69 (5), 427–440 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, Y. H. et al. Modulators of the balance between M1 and M2 macrophages during pregnancy. Front. Immunol.8, 120 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forger, F. & Villiger, P. M. Publisher Correction: Immunological adaptations in pregnancy that modulate rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol.16 (3), 184 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ledee, N. et al. The uterine immune profile May help women with repeated unexplained embryo implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.75 (3), 388–401 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petitbarat, M. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK)/fibroblast growth factor inducible-14 might regulate the effects of Interleukin 18 and 15 in the human endometrium. Fertil. Steril.94 (3), 1141–1143 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deveer, M. et al. Comparison of pregnancy outcomes in different localizations of uterine fibroids. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol.39 (4), 516–518 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahalingam, M. et al. Uterine myomas: effect of prior myomectomy on pregnancy outcomes. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.35 (25), 8492–8497 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vilos, G. A. et al. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can.37 (2), 157–178 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hashimoto, A. et al. Adenomyosis and adverse perinatal outcomes: increased risk of second trimester miscarriage, preeclampsia, and placental malposition. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.31 (3), 364–369 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vercellini, P. et al. Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility. Fertil. Steril.119 (5), 727–740 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Motomura, K. et al. Fetal and maternal NLRP3 signaling is required for preterm labor and birth. JCI Insight, 7(16), e158238 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Nowarski, R. et al. Epithelial IL-18 equilibrium controls barrier function in colitis. Cell163 (6), 1444–1456 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foster, B. et al. Detection of intracellular cytokines by flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Immunol, 2007. Chapter 6: p. 6 24 1–6 24 21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Kovacs, S. B. et al. Evaluating cytokine production by flow cytometry using Brefeldin A in mice. STAR. Protoc.2 (1), 100244 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.