Abstract

Enhanced oil recovery (EOR) remains a critical focus for the petroleum industry, aiming to overcome the challenges of residual oil mobilization and maximize hydrocarbon recovery in increasingly complex reservoirs. This study introduces an innovative approach using synthesized Polylactic Acid (PLA)/Henna composites as an environmentally sustainable additive to enhance oil recovery through mechanisms such as interfacial tension (IFT) reduction, wettability alteration, and physical sweeping for improved fluid sweep efficiency. The composite was synthesized using extrusion techniques to ensure a uniform filler dispersion and was extensively characterized through FTIR, SEM, and EDS analyses. Brines, including seawater (SW), formation water (FW), and PLA-Henna-modified SW, were formulated to simulate actual reservoir conditions. Experimental analyses included IFT measurement using the pendant drop method, wettability studies using contact angle measurements, and core flooding experiments to assess EOR performance. Experimental findings revealed that the optimal PLA-Henna concentration was 2 wt%, which achieved significant IFT reductions (to 27 mN/m in SW). The composite also altered rock wettability from oil-wet to water-wet with pronounced effects in SW brine, where contact angles reduced from 142 to 89°. Core flooding experiments highlighted an increase in oil recovery factors, with PLA-Henna-modified SW yielding the highest recovery (85%) compared to FW (49.7%) or SW (61%). These advancements emphasize PLA/Henna composites’ potential for sustainable EOR applications, ensuring improved recovery outcomes while utilizing biodegradable, eco-friendly materials.

Keywords: Enhanced oil recovery, PLA/Henna, Interfacial tension, Wettability alteration, Core flooding

Subject terms: Chemistry, Energy science and technology, Engineering, Environmental sciences, Materials science

Introduction

The global energy landscape is dominated by crude oil, which continues to be a major source of energy, despite ongoing exploration of alternative energy sources such as solar, wind, and geothermal. While efforts to transition to renewable energy are progressing, they are not sufficient to keep pace with the growing energy demand driven by industrialization and population growth1–5. As a result, crude oil remains indispensable in meeting global energy needs and sustaining economic development6–9. However, the discovery of new oil reservoirs has declined sharply, leaving the petroleum industry with the significant challenge of maximizing recovery from existing reservoirs. This has necessitated research into advanced recovery techniques, collectively referred to as EOR10–14.

EOR processes are implemented after primary and secondary recovery methods become ineffective in extracting residual oil trapped within reservoir pores. Primary oil recovery utilizes the reservoir’s natural energy to extract hydrocarbons, which typically yields only 5–15% of the original oil-in-place (OOIP)15–19. Secondary recovery, employing techniques like water or gas flooding to maintain reservoir pressure, increases oil production but still leaves over half of the OOIP trapped. This inefficiency has made tertiary recovery, or EOR, critical for maximizing reserves. EOR encompasses a variety of methods, including thermal, miscible, and chemical techniques, applied based on reservoir conditions to enhance fluid properties, reduce IFT, and increase rock wettability, thereby mobilizing residual oil20–23.

Chemical EOR methods have gained prominence due to their adaptability and effectiveness in recovering oil from both conventional and unconventional reservoirs. Surfactants, polymers, and nanoparticles are among the most widely used chemical agents in EOR. Surfactant flooding is particularly effective for reducing IFT, altering rock wettability, and emulsifying residual oil droplets, thereby creating an oil bank that improves recovery19,24–27. Surfactants, composed of hydrophilic “head” groups and hydrophobic “tail” chains, reduce capillary forces that trap oil and facilitate crude oil mobilization in both sandstone and carbonate formations. Wettability alteration, another crucial mechanism in surfactant-based EOR, shifts rock surfaces from being oil-wet to water-wet, enabling better interaction between the injected aqueous phase and residual oil. Amphiphilic surfactants, bio-based surfactants, and polymers are being increasingly utilized due to their environmental friendliness and compatibility in high-salinity and high-temperature conditions28–31.

Polymers are another class of chemical agents that exhibit distinct viscoelastic properties, allowing them to enhance oil recovery by improving the mobility ratio and reducing water bypass. Synthetic and natural polymers, such as partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) and xanthan gum, have been extensively studied and implemented in field-scale applications globally. These polymers reduce viscous fingering, improve sweep efficiency, and recover oil films in constricted pores through pulling and stripping mechanisms5,32–35 Further advancements in polymer technology have led to hybrid applications, where polymers are combined with surfactants, alkalis, or nanoparticles to enhance their efficiency. Polymeric nanoparticles, surfactant-polymer formulations, and alkali-polymer solutions represent the forefront of chemical EOR, providing innovative solutions to longstanding challenges in oil recovery36–39.

In recent years, nanotechnology has introduced a transformative dimension to EOR, allowing the interaction and modification of reservoir properties at the nanoscale. Nanoparticles (NPs) exhibit unique properties such as high surface energy, small particle size, and tunable chemistry, enabling them to alter fluid dynamics and reservoir rock attributes effectively. For instance, NPs can reduce IFT, change rock wettability, and stabilize emulsions, leading to improved mobility of residual oil4,40–43. Core–shell nanomaterials have further improved NP stability under high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) conditions, addressing issues related to aggregation and dissipation. Bio-nanotechnology, which integrates biomaterials with nanoparticles, offers additional advantages such as biodegradability, low toxicity, and environmental sustainability. By combining NPs with biosurfactants or polymers, the dispersion stability and oil recovery efficiency of chemical EOR agents can be further enhanced44–47.

However, advanced chemical EOR methods, including formulations employing surfactants, polymers, and nanoparticles, face several challenges such as high costs, formation damage, and ecological concerns. While synthetic chemicals demonstrate exceptional efficiency, their long-term impact on reservoir conditions, produced water management, and overall environmental sustainability remain major areas of concern. Recent efforts have focused on developing bio-based EOR agents that are both economical and eco-friendly2,48–52. For example, bio-based surfactants derived from natural sources and biopolymers extracted from plant or microbial products have shown promising results in reducing IFT and altering wettability under extreme reservoir conditions. These advancements align with global environmental regulations and the growing emphasis on sustainability in the petroleum industry53–56.

This paper presents a systematic investigation into the development and application of bio-based Polylactic Acid (PLA)/Henna composites for EOR. The study follows a robust workflow beginning with the synthesis and characterization of the composite materials, ensuring reproducibility and uniform filler integration. Benchmark tests, including IFT reductions, wettability alteration, and core flooding experiments, were conducted using synthetic brines to simulate real reservoir conditions. The study rigorously explored the composite’s interaction with crude oil and porous rock systems under HPHT conditions, quantifying oil recovery performance at different stages. This integrated methodology bridges nanocomposite materials’ potential applications with their practical performance in EOR, establishing PLA/Henna as a sustainable and efficient solution.

This research presents a new composite material for enhanced oil recovery by combining Polylactic Acid and Henna. Polylactic Acid is a well-known biodegradable plastic made from renewable resources. It’s sustainable, biocompatible, and its degradation can be controlled. However, on its own, PLA doesn’t have the varied surface chemistry or particle-based pore-blocking abilities needed for EOR. Henna, a natural plant material, is rich in biopolymers and other organic compounds. It has a fine particulate structure and active hydroxyl groups, making it a promising candidate for EOR. Despite its potential, Henna has not been extensively studied for this purpose.

The novelty of this study lies in the synergistic combination of these two materials. This composite aims to use the strengths of both: PLA provides a stable, biodegradable structure, while Henna contributes the particulate matter that is essential for effective EOR.

Materials and methods

Materials

Polylactic acid

The Polylactic Acid (PLA) pellets utilized in this research were obtained from ItLavga Company. PLA is a thermoplastic polymer that is renewable and derived from natural sources such as corn starch and sugarcane, which makes it an excellent choice for environmentally friendly applications. Its characteristics, including inherent biodegradability, mechanical strength, and ease of processing, contribute to its widespread use across various industries. Particularly relevant to drilling fluid rheology, PLA’s compatibility with natural fillers can enhance fluid performance across a range of environmental conditions57,58.

Henna powder

The henna powder employed as a natural filler in this study was sourced from EbnManooye, boasting a purity certification of over 98%. The henna was produced through a spray-drying process that ensured high quality and consistency in its properties. This method resulted in fine henna particles characterized by improved uniformity and stability, rendering them suitable for use in polymer composites. The high purity and controlled particle characteristics of the henna powder were critical for achieving optimal compatibility and performance when integrated with the Polylactic Acid (PLA) matrix59,60.

Salts

The salts used in this study, including potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), and calcium chloride (CaCl2), were obtained from Merck with a certified purity exceeding 98%. These salts were selected due to their widespread occurrence in natural brines, such as SW and FW. Their high purity ensured consistency and accuracy in synthesizing artificial brines for experimental purposes. The individual salts were carefully weighed and dissolved in deionized water in specific proportions to replicate the ionic composition of SW and FW. The prepared solutions closely simulated the chemical environment encountered in EOR operations.

The synthesized brines were essential for examining the performance of the developed PLA/henna polymer under conditions mimicking real reservoir environments. Each salt plays a distinct role in influencing the physiochemical properties of the brine, such as ionic strength, salinity, and mineral compatibility. For instance, NaCl and KCl provide the primary monovalent ions found in high-salinity brines, while divalent ions such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ (introduced through CaCl2 and MgCl2) are critical for understanding interactions between the polymer and formation minerals. Accurate formulation of brines was therefore paramount to ensure relevance and reliability in evaluating the polymer’s application within EOR systems61,62.

Table 1 shows the concentration of materials that were used in sample preparation.

Table 1.

The concentration of brines that were used in sample preparation.

| Brine type | Component | Concentration (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| Formation water (FW) | NaCl | 140,000 |

| KCl | 5000 | |

| CaCl2 | 28,000 | |

| MgCl2 | 6000 | |

| Total dissolved solids (TDS) | 250,000 | |

| Seawater (SW) | NaCl | 27,000 |

| KCl | 1000 | |

| CaCl2 | 1200 | |

| MgCl2 | 3000 | |

| Na2 SO4 | 4000 | |

| NaH CO3 | 200 | |

| Total dissolved solids (TDS) | 45,000 |

Experimental procedure

This section presents experimental procedures of different stages as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methodology table which clearly present the procedures of various stages.

| Step | Procedure |

|---|---|

| 1. Henna preparation | Clean, grind, and sieve Henna leaves into a fine powder (250 µm). Dry the powder at 60 °C for 24 h |

| 2. Mixing | Weigh and mix PLA pellets and the dried henna powder in a ratio of 98% PLA to 2% henna |

| 3. Dissolving | Add the PLA/Henna mixture to chloroform. Stir at 1000 rpm and 60 °C for 1 h until a homogeneous solution is formed |

| 4. Film casting | Pour the homogeneous mixture into a glass petri dish to create a thin film |

| 5. Drying | Allow the film to dry at room temperature for 48 h to evaporate all the chloroform |

| 6. Final preparation | Grind the dried film into a fine powder for use in subsequent experiments |

Synthesizing PLA/Henna composite

The PLA (Polylactic Acid)/Henna composite was synthesized through a carefully-structured procedure designed to achieve uniform dispersion and effective integration of the filler within the polymer matrix. The process began with the preparation of the raw materials to ensure their compatibility for thermal processing. PLA pellets were dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 12 h to remove residual moisture, which is crucial as moisture can catalyze hydrolytic degradation during heat processing. This degradation may adversely affect the molecular weight and mechanical properties of PLA, compromising the quality of the final composite. Henna powder, prepared to a particle size range of 80–100 microns, was selected as the natural filler due to its physicochemical properties and compatibility with the polymer. Henna powder was incorporated into the PLA matrix at a loading of 15% by weight. To facilitate the initial blending, the PLA pellets and Henna powder were manually mixed to minimize inconsistency in dispersion before further thermomechanical processing.

The blended mixture underwent extrusion using a single-screw extruder operated at temperatures ranging from 180 to 200 °C, chosen to match the melting characteristics and thermal stability of PLA while mitigating risks of polymer degradation. The screw speed was optimized at approximately 30 rpm, allowing adequate residence time in the extruder for consistent melting, mixing, and dispersion of Henna particles throughout the PLA matrix. The resulting molten composite material was extruded through a die to produce continuous filaments, which were subsequently air-cooled to room temperature to maintain their structural integrity. The cooled filaments were collected onto spools for convenient handling. To prepare the material for subsequent applications, the extruded filaments were ground into fine particles using a mortar and pestle, ensuring fine fragmentation suitable for further processing. The particle sizes were carefully reduced, with the final ground composite passing through a 400-mesh sieve (≈ 37 microns) to guarantee size uniformity. Achieving this level of homogeneity in particle size was critical for optimizing the composite’s performance, particularly in applications involving enhanced drilling fluid rheology and filtration properties. The resulting PLA/Henna composite exhibited a uniformly dispersed filler within the polymer matrix, reflecting the success of the synthesis method in producing a high-quality material for advanced engineering applications.

IFT measurement

The IFT between oil and brine was measured using the pendant drop method, a widely accepted technique in fluid interface studies. In this method, a droplet of oil is suspended from a needle in a high-precision optical cell filled with brine, ensuring that the droplet is exposed to a stable brine environment. The shape of the droplet, influenced by interfacial forces, is captured using high-resolution imaging equipment, and the coordinates of the droplet profile are analyzed to calculate the IFT based on the Young–Laplace equation. This procedure allows for accurate and reproducible measurements of interfacial properties, making it ideal for studying fluid behavior in EOR scenarios.

Four types of brines were evaluated in this study. The first was synthetic formation brine, formulated to replicate reservoir conditions with a total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration of 250,000 ppm. The second type was synthetic SW with a TDS of 45,000 ppm, representing marine environments commonly encountered during EOR operations. The third and fourth brines were FW and SW modified with the PLA/Henna composite (PLAHF and PLAHS), where the polymer-filler matrix was introduced to alter the brine properties for enhanced performance. These brines were carefully prepared to ensure compatibility with experimental conditions and validate the effects of the synthesized composite on interfacial behavior.

IFT plays a critical role in EOR, as it governs the interaction between oil and water phases within porous reservoir rocks. Lowering IFT reduces the capillary forces that trap oil in reservoir pores, allowing for higher oil mobilization and increased recovery rates. The effectiveness of surfactants, polymers, or other additives in EOR processes is directly tied to their ability to alter IFT, thereby optimizing fluid displacement and minimizing residual oil saturation. As such, accurate characterization of IFT behavior is essential for designing efficient EOR strategies and achieving sustainable hydrocarbon recovery under challenging reservoir conditions63–65.

Wettability measurement

The wettability measurement was conducted using the contact angle approach, which is a reliable and widely-used method for characterizing the interaction between fluids and rock surfaces. First, cylindrical core plugs obtained from sandstone rocks were sliced into thin discs to prepare rock surfaces suitable for wettability experiments. These rock slices were immersed in FW for initial aging. To initiate the measurement, an oil droplet was gently placed onto the surface of the rock slices using a precision syringe, and the initial contact angle (Ө0) was recorded. At this stage, special care was taken to ensure that the droplet remained stationary without spreading or moving on the rock surface, as this would affect the accuracy of the measurement. The initial angle Ө0 provided baseline data on rock wettability in fresh conditions before exposure to HPHT conditions and aging.

Following the initial measurements, the rock samples were subjected to aging to simulate reservoir-like conditions. The rock slices were immersed in crude oil and placed inside HPHT cells equipped to maintain pressures of up to 2000 psi and a temperature of 105 °C. Aging was conducted over a 28-day period during which oil was continually in contact with the rock surface within bulk liquids of SW, formation brine, or PLAHS and PLAHF. After the aging process was completed, the oil droplet contact angle (Ө1) was measured to examine the evolution of wettability under prolonged exposure to oil under realistic reservoir conditions. This step was crucial to analyzing dynamic wettability changes, reflecting possible rock-fluid interactions that occur during aging.

To further evaluate the impact of brines on wettability alteration, the aged rock slices were immersed in the various brines for an additional two weeks under similar HPHT conditions. This extended exposure allowed more profound interaction between the rock surfaces, brines, and oil droplets, potentially influencing contact angle behavior. After these additional two weeks, the final measurement (Ө2) of the oil droplet contact angle was carried out. This final measurement was used to assess the overall wettability transition caused by continuous aging and brine treatments, providing valuable insights into the effectiveness of each brine in altering wettability. By comparing Ө0, Ө1, and Ө2, a comprehensive understanding of how wettability evolves in EOR processes was achieved66–69.

Core flooding experiment

The core flooding experiments were conducted using three identical sandstone core plugs, each with a diameter of 1.5 inches and a length of 5 inches, to ensure consistency across the tests. In the first step, the core plugs were mounted within the core holder of the flooding setup and thoroughly washed using sequential injections of toluene and methanol to remove any residual salts, organic contaminants, or other impurities. This cleaning step was crucial for eliminating unwanted materials that could alter the experimental results. After washing, the cores were dried in a controlled oven at 70 °C for one week until no further reduction in mass was observed, ensuring complete dryness before subsequent procedures.

The basic characteristics of the sandstone core plugs used in the core flooding experiments are indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

The basic characteristics of the sandstone core plugs used in the core flooding experiments.

| Core plug | Diameter (inches) | Length (inches) | Grain density (g/cc) | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5 | 5 | 2.665 | 23.5 | 50.9 |

| 2 | 1.5 | 5 | 2.667 | 23.9 | 51.3 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 5 | 2.671 | 23.6 | 50.5 |

Following the drying process, the core plugs were remounted into the core holder, and formation brine was injected through each core to saturate the pore spaces uniformly. The saturated cores were then placed into an HPHT chamber containing FW at conditions of 2000 psi and 105 °C for one week to simulate FW aging and mineral-brine-rock interactions often encountered in reservoirs. Next, crude oil was injected into the core plugs, displacing the formation brine and reestablishing the initial oil saturation to replicate reservoir conditions as accurately as possible. After the injection step, the cores were completely submerged in crude oil within an HPHT chamber and aged for a duration of 28 days under the same conditions (2000 psi and 105 °C) to simulate long-term reservoir conditions and promote wettability equilibrium.

Table 4 outlines the order of the core flooding experiments, specifying the fluids used for both the secondary and tertiary recovery phases. The core flooding experiments were conducted on three separate sandstone core plugs to evaluate the performance of different flooding scenarios. The experiments consisted of both a secondary and a tertiary recovery stage.

Table 4.

The sequence of the core flooding experiments, explicitly indicating which fluids were used during the secondary and tertiary recovery stages.

| Core plug | Secondary recovery stage (Fluid injected) | Tertiary recovery stage (Fluid injected) |

|---|---|---|

| Core 1 | Formation water (FW) | PLA-Henna-modified formation water (PLAHF) |

| Core 2 | Seawater (SW) | PLA-Henna-modified seawater (PLAHS) |

| Core 3 | Seawater (SW) | PLA-Henna-modified seawater (PLAHS) |

Secondary recovery stage

- Fluids Used Each core was flooded with a specific fluid until no more oil was produced.

- Core 1 (Control) Injected with Formation Water (FW) (with viscosity of 1.26 cp).

- Core 2 Injected with Seawater (SW) (with viscosity of 1.18 cp).

- Core 3 Injected with Seawater (SW).

Tertiary recovery stage

- Fluids Used After the secondary recovery stage, the cores were flooded with a PLA/Henna-modified fluid to recover additional oil.

- Core 1 Flooded with PLA-Henna-modified Formation Water (PLAHF) (with viscosity of 6.3 cp).

- Core 2 Flooded with PLA-Henna-modified Seawater (PLAHS) (with viscosity of 5.8 cp).

- Core 3 Also flooded with PLA-Henna-modified Seawater (PLAHS).

For the core flooding experiments, each core underwent a series of injections to evaluate the fluid interactions and performance. For each core, two pore volumes (PV) of FW and two PV of the respective test fluids were sequentially injected. Specifically, FW was used for the first core (control), synthetic SW for the second, and PLA/Henna-modified SW (PLAHS) for the third. Injection parameters, including pressure drop, recovery factor, and cumulative fluid injection volume, were recorded throughout the experiments. These measurements provided a comprehensive dataset for assessing the fluid-rock interactions, brine efficiency, and EOR potential for the test fluids under reservoir-like conditions70–72.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of PLA/Henna composites

The synthesis of PLA/Henna composites was conducted twice, adhering to the established methodology, to assess the reproducibility of the fabrication process. Advanced characterization techniques, including Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), were employed to analyze the synthesized composites and verify consistency across both batches. The results obtained from both synthesis cycles exhibited remarkable similarity, confirming the reliability and repeatability of the composite fabrication method as well as the stability of its physicochemical characteristics.

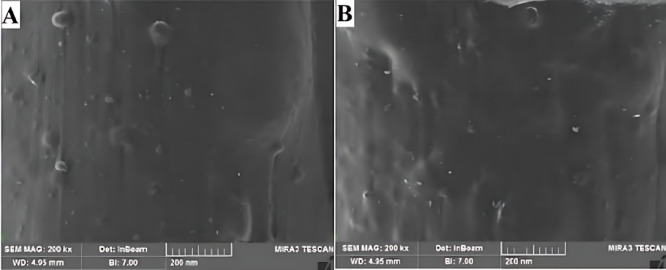

Figure 1 highlights SEM images of composites prepared during the first and second synthesis cycles. These images reveal surfaces with smooth and homogeneous textures, exhibiting minimal voids and no noticeable agglomeration of Henna filler particles. The Henna powder appears to be uniformly distributed within the PLA matrix, which is indicative of a highly effective mixing process. Such uniform filler dispersion improves interfacial bonding between the PLA matrix and Henna particles, ensuring consistent mechanical integrity and material quality. Moreover, the absence of voids or particle aggregation signifies strong polymer-filler compatibility, which is essential for optimizing the composite’s performance73.

Fig. 1.

SEM images related to (A) first and (B) second synthesis process.

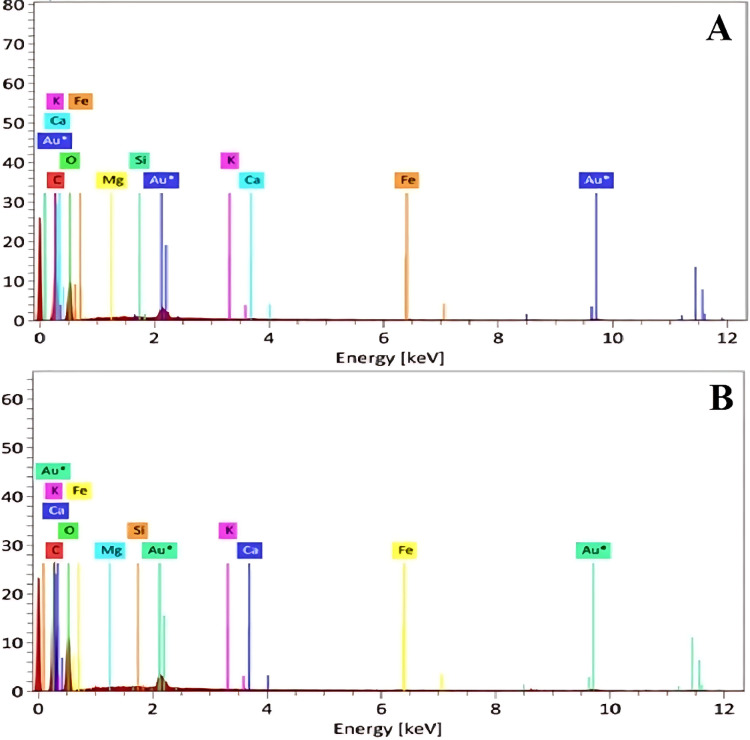

The EDS results (Fig. 2) further validate the successful incorporation of Henna as a filler material. The spectra obtained from each batch detect essential elements characteristic of Henna, such as calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and magnesium (Mg), uniformly distributed across the composite samples. These findings align with Henna’s expected chemical composition. The strong correlation between EDS results from both synthesis batches confirms the repeatability of the process, with consistent filler dispersion achieved in the composite matrix during each cycle73,74.

Fig. 2.

EDX test results related to (A) first and (B) second synthesis process.

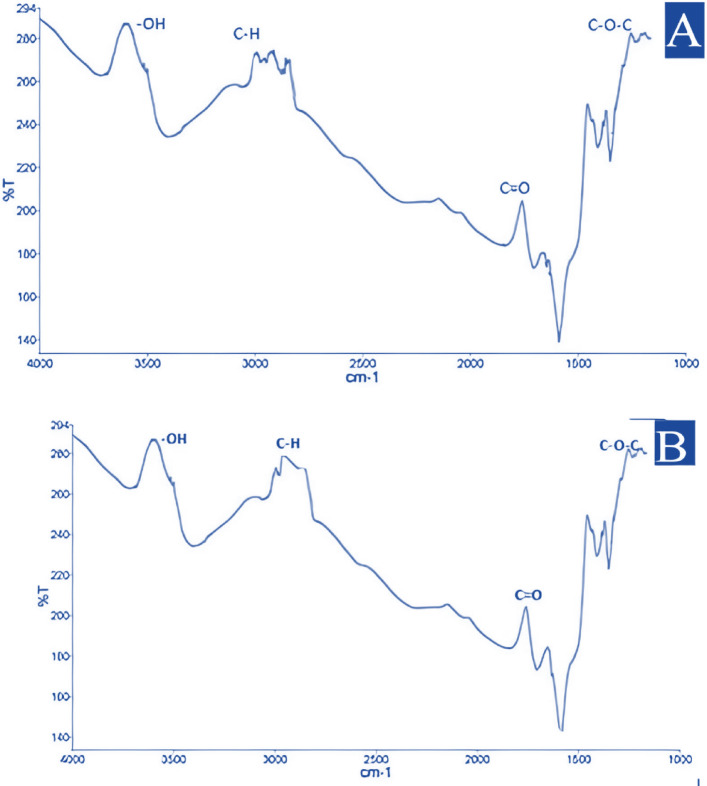

Figure 3 presents FTIR analyses of the PLA/Henna composites, highlighting key vibrational peaks characteristic of both the PLA matrix and Henna filler. Peaks associated with the PLA polymer chain, such as the C=O stretching vibration near 1750 cm−1 and C–H stretching vibration at approximately 2977 cm−1, indicate the stability and structural integrity of PLA during composite synthesis. The C–O–C stretching bands between 1000 and 1200 cm−1 further confirm the retention of PLA’s molecular structure. An additional broad absorption band in the range of 3500–3700 cm−1 corresponds to hydroxyl (–OH) groups contributed by Henna filler. For composites containing higher filler content, this peak intensifies, suggesting increased hydrogen bonding interactions between Henna’s hydroxyl groups and the ester functional groups in PLA. These interactions enhance filler-matrix adhesion, contributing to improved compatibility and mechanical performance. The FTIR analyses from both synthesis batches also show consistent results, reinforcing the reliability and repeatability of the composite production method75,76.

Fig. 3.

FTIR spectra of PLA/Henna composite related to (A) first synthesis and (B) second synthesis process.

IFT experiments results

IFT measurements between crude oil and brine phases are detailed in Table 5, which quantifies the effects of different PLA/Henna concentrations on IFT for both SW and FW as the bulk phase. The results highlight the progressive reduction in IFT values as PLA/Henna concentration increases, indicating its potential to improve interfacial properties and facilitate the mobilization of residual oil during EOR processes.

Table 5.

Effect of PLA/Henna concentration on oil-brine IFT.

| Bulk phase | Droplet | PLA/H concentration (wt%) | IFT (mN/m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FW | Oil | 0 | 43 |

| FW | Oil | 1 | 42 |

| FW | Oil | 2 | 38 |

| FW | Oil | 4 | 38 |

| SW | Oil | 0 | 41 |

| SW | Oil | 1 | 37 |

| SW | Oil | 2 | 27 |

| SW | Oil | 4 | 26 |

The data in Table 5 reveal distinct trends in IFT behavior for both brines. For FW, the IFT begins at 43 mN/m in the absence of PLA/Henna and marginally decreases to 42 mN/m with 1 wt% PLA/Henna added. Increasing the concentration to 2 wt% leads to a more pronounced IFT reduction to 38 mN/m. However, beyond 2 wt%, further increments in PLA/Henna concentration (4 wt%) yield no additional improvement, as the IFT remains constant at 38 mN/m. This indicates that the optimal concentration of PLA/Henna in FW is 2 wt%, where the composite achieves its maximum efficiency in reducing IFT.

SW displayed a similar IFT reduction trend, although its initial performance was slightly better compared to FW. The IFT of crude oil in SW starts at 41 mN/m without PLA/Henna, which decreases to 37 mN/m with 1 wt% PLA/Henna. The reduction becomes substantially pronounced at 2 wt%, where the IFT drops to 27 mN/m, a 34% decrease compared to untreated SW. This indicates that SW exhibits better compatibility with PLA/Henna than FW. Incrementing the PLA/Henna concentration to 4 wt% causes only a marginal reduction, where IFT decreases slightly to 26 mN/m, suggesting diminishing returns beyond the 2 wt% concentration.

Wettability measurement

The ability of PLA/Henna composites to alter rock wettability is presented in Table 6, which quantifies contact angle (Ө) measurements under various conditions (initial angle, after aging in oil, and post-treatment with PLA/Henna). The results demonstrate a progressive shift in wettability from oil-wet to water-wet behavior, with a clear dependence on PLA/Henna concentration and the type of brine used as the bulk phase. The findings confirm that PLA/Henna composites are effective in wettability alteration, particularly at an efficient concentration of 2 wt%, beyond which further improvement in the contact angle is minimal.

Table 6.

Contact angle measurements for wettability alteration using PLA/Henna composites.

| No | Bulk phase | PLA/Henna (wt%) | Ө0 | Ө1 | Ө2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FW | 0 | 75 | 143 | 129 |

| 2 | FW | 1 | 75 | 140 | 127 |

| 3 | FW | 2 | 74 | 144 | 119 |

| 4 | FW | 4 | 75 | 141 | 117 |

| 5 | SW | 0 | 75 | 142 | 122 |

| 6 | SW | 1 | 74 | 144 | 113 |

| 7 | SW | 2 | 75 | 143 | 89 |

| 8 | SW | 4 | 75 | 144 | 88 |

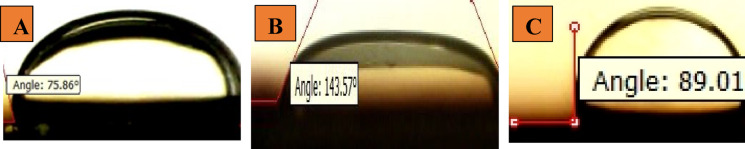

Table 6 illustrates the progressive reduction in contact angle after treatment with PLA/Henna composites, signifying a shift in rock surface wettability from oil-wet to water-wet conditions. Initial contact angles (Ө0) of approximately 75° indicate mildly water-wet surfaces before oil aging. After aging in oil (Ө1), the contact angle increases significantly, with values ranging between 140° and 144°, characteristic of oil-wet surfaces. Application of PLA/Henna composites reduces the contact angle further (Ө2), restoring water-wet behavior through effective wettability alteration mechanisms.

For FW, the untreated rock (0 wt% PLA/Henna) has a post-treatment contact angle of 129°, indicating minimal wettability alteration. Adding 1 wt% PLA/Henna marginally reduces the angle to 127°, while increasing the concentration to 2 wt% achieves significant reduction, lowering the contact angle to 119°. This suggests optimized wettability alteration at 2 wt%, as further increases in PLA/Henna concentration (4 wt%) yield only a minor improvement, reducing the contact angle to 117°.

In SW as the bulk phase, the wettability alteration effect is more pronounced. Untreated rock slices display a post-treatment contact angle of 122°, which decreases to 113° with 1 wt% PLA/Henna. At the optimal concentration of 2 wt%, the contact angle is further reduced to 89°, representing a major shift to strongly water-wet behavior. Increasing the concentration beyond 2 wt% (to 4 wt%) results in only marginal improvement (contact angle of 88°), confirming the efficiency threshold at 2 wt%.

The mechanism underlying PLA/Henna’s ability to alter wettability involves interfacial interactions facilitated by the composite materials. Henna, rich in hydroxyl (–OH) groups, interacts with polar components on the rock surface and the brine phase through hydrogen bonding. These interactions displace oil molecules adhered to the rock surface and increase the wettability of the surface toward water. Simultaneously, PLA provides structural support, enhancing the adherence of Henna particles to the rock surface and stabilizing polar groups for sustained wettability alteration.

The distinction between FW and SW performance can be attributed to ionic strengths and brine compositions. SW contains higher concentrations of monovalent (Na+, Cl−) and divalent ions (Ca2+, Mg2+), which synergistically interact with Henna’s active sites to amplify the adsorption and wettability alteration processes. These ions are more effective in promoting surface reconfiguration and reducing the oil-rock interactions compared to FW, resulting in more pronounced reductions in contact angles. (See Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Wettability captures related to fluid number 7 in (A) Ө0 (B) Ө1 and (C) Ө2.

Core flooding experiment

The results presented in Table 7 and Figs. 5, 6, and 7 demonstrate the effect of FW, SW, and PLAHS on oil recovery efficiency, pressure drop, and breakthrough phenomena during tertiary recovery processes. FW and SW were selected due to their availability and ease of access in onshore and offshore oil fields, respectively. PLAHS (2 wt%) was chosen based on its superior performance in reducing IFT and altering wettability in previous tests. Notably, as indicated in Table 7, pressure increases occurred in the tertiary phase, corresponding to the physical plugging of pore throats caused primarily by the PLA-Henna composite.

Table 7.

Performance of FW, SW, and PLA-Henna-containing SW in oil recovery.

| Core number | FW pressure (psi) | Oil pressure (psi) | FW pressure (psi) | RF (%) | Tertiary fluid | Tertiary pressure (psi) | Tertiary RF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80 | 150 | 192 | 43 | FW | 181 | 49.7 |

| 2 | 81 | 153 | 197 | 44 | SW | 169 | 61 |

| 3 | 80 | 152 | 201 | 43 | PLAHS | 574 | 85 |

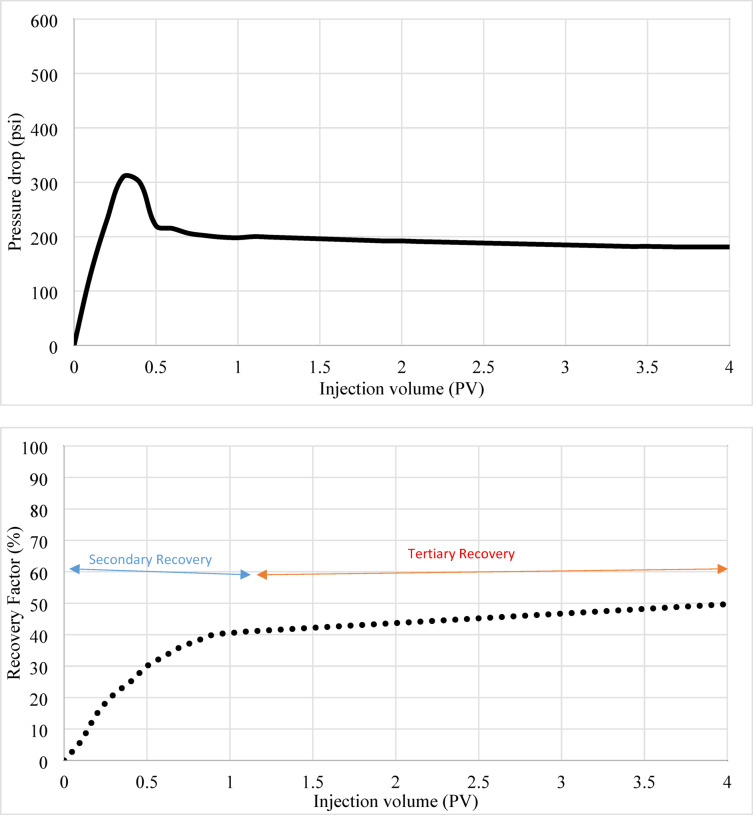

Fig. 5.

RF vs. Pressure drop during secondary and tertiary flooding (formation water).

Fig. 6.

RF vs. Pressure drop during secondary and tertiary flooding (sea water).

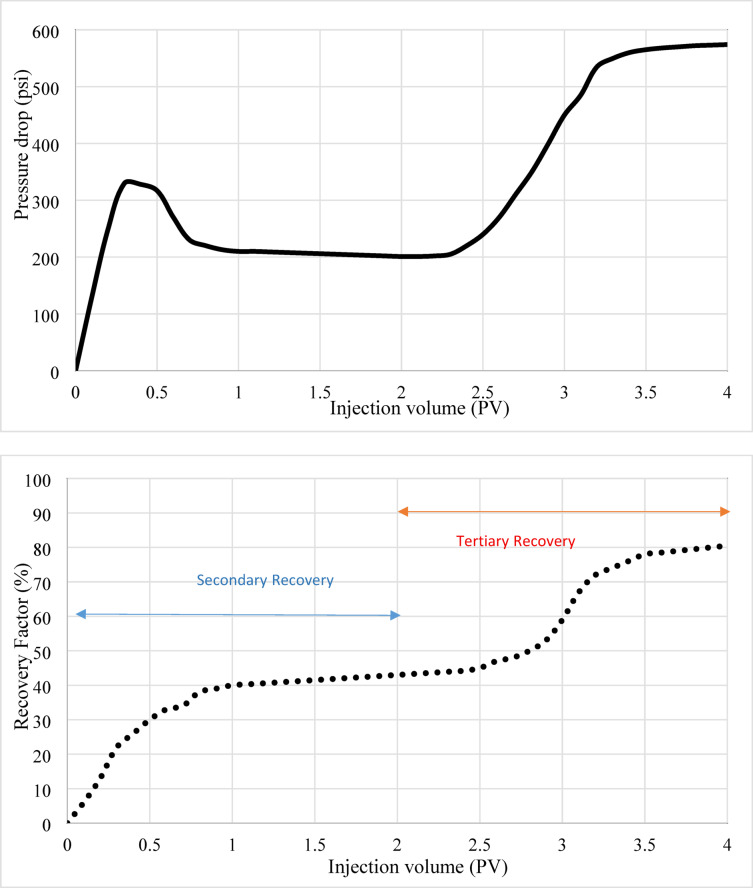

Fig. 7.

RF vs. Pressure drop during PLAHSW flooding.

The results from Table 7 demonstrate a consistent and repeatable experimental setup, as the pressure drop for the first, second, and third flooding phases are nearly identical for each core plug during the plateau section. This confirms the reproducibility of the experiments, ensuring that the outcomes are reliable for further analysis.

For the tertiary fluid injection, FW demonstrated a limited improvement in RF (43 to 49.7%) due to its inability to significantly reduce IFT or alter wettability. Using SW as the tertiary fluid improved the RF to 61%, driven by its superior wettability alteration capabilities due to lower ionic strength and the presence of lower divalent cations (Mg2+, Ca2+). The tertiary phase pressure drop for SW (169 psi) was slightly lower than FW, suggesting less resistance to flow but more favorable wettability effects.

PLAHS demonstrated the most significant improvement, with the RF soaring to 85%. This enhanced performance is attributed to a combination of mechanisms: (1) stronger IFT reduction due to the amphiphilic properties of Henna’s polar functional groups, which modify oil-brine interactions; (2) wettability alteration induced by Henna’s hydroxyl groups and PLA’s structural compatibility; and (3) physical sweeping caused by mobility control and microparticle plugging of high-permeability channels, which diverted the injected fluid to previously unswept regions. The pressure drop during the PLA-Henna flooding stage reached 574 psi due to the physical plugging and mobility control effects. Figures 5, 6, and 7: Relationship Between Recovery Factor, Pressure Drop, and Injection Volume.

The graph in Fig. 5 illustrates the RF and pressure drop for core number 1 during FW flooding as a tertiary fluid. Initially, the RF increased alongside injection volume, plateauing near 43% during secondary recovery. During tertiary injection, the RF gradually increased to 49.7% with a stable pressure drop at 181 psi. The relatively slow improvement reflects the limited ability of FW to alter wettability or reduce IFT, serving primarily as a displacement fluid.

The graph in Fig. 6 demonstrates a more substantial improvement in RF during tertiary SW flooding. After reaching 44% during secondary recovery, the SW injection achieved a tertiary RF of 61%. The pressure profile remained stable at approximate values of 169 psi during the tertiary phase, reflecting SW’s ability to improve oil displacement without significant physical plugging effects. The higher RF trend suggests significant improvements in wettability and enhanced mobilization of residual oil in the pore network.

Figure 7 highlights the performance of PLA-Henna-incorporated SW as a tertiary fluid. The graph reveals a dramatic improvement in RF, reaching 85% in the tertiary phase due to the combined effects of IFT reduction, wettability alteration, and physical sweeping mechanisms. The pressure drop during PLA-Henna flooding steadily increased throughout the tertiary phase, peaking at 574 psi, indicating significant physical plugging.

Potential industrial applications and limitations of PLA/Henna

The PLA/Henna composite effectively reduces IFT due to its amphiphilic structure. Henna, rich in hydroxyl groups, interacts with both the hydrophilic brine phase and the hydrophobic oil phase, disrupting interfacial forces. This action minimizes capillary forces within porous media, enhancing oil mobility. The PLA matrix stabilizes Henna particles, allowing them to exhibit prolonged interfacial activity under reservoir conditions. PLA/Henna composites drive wettability shifts from oil-wet to water-wet by modifying rock surface interactions. Henna’s polar functional groups form hydrogen bonds with brine ions and displace adhered oil molecules, enabling higher water infiltration. The ions in SW synergistically interact with the composite, amplifying this effect to improve rock wettability and recovery efficiency.

The successful application of PLA/Henna composites facilitates environmentally sustainable EOR practices, addressing critical industry challenges. Firstly, by deploying bio-based and biodegradable PLA/Henna materials, operators can minimize ecological footprints, aligning with global sustainability goals. Secondly, the composite’s capability to enhance oil recovery factors offers substantial economic benefits, particularly in aging reservoirs with significant residual oil. Additionally, the use of SW, an easily accessible resource in offshore oil fields, combined with PLA/Henna’s superior performance in such brines, reduces operational costs and product sourcing complexities. The scalability and ease of synthesis further boost its industrial viability, making it a practical solution for large-scale applications in both onshore and offshore reservoirs.

One limitation of this study is the exclusion of long-term degradation behavior for PLA/Henna composites under reservoir conditions. The impact of high temperatures, pressures, and brine corrosivity on composite longevity and efficiency remains unassessed and warrants further evaluation. Another limitation is laboratory-scale experiments’ inherent inability to fully replicate field-scale complexities. Factors such as heterogeneous rock formation, multi-phase flow dynamics, and interaction with naturally occurring reservoir fluids may influence performance beyond the scope of this controlled study. Expanding to field trials is necessary for a comprehensive understanding.

Conclusion and future work

This research successfully demonstrates the efficacy of a novel Polylactic Acid (PLA)/Henna composite for enhanced oil recovery (EOR). The composite was synthesized and characterized, with analysis from FTIR, SEM, and EDS confirming a uniform and stable structure, which is crucial for its performance in reservoir environments.

Key findings from the study include:

Interfacial Tension (IFT) Reduction The addition of the PLA/Henna composite significantly reduced IFT values. An optimal concentration of 2 wt% lowered the IFT to 27 mN/m in seawater (SW) (with viscosity of 1.19 cp) and to 38 mN/m in formation water (FW) (with viscosity of 1.26 cp). This reduction in IFT is a primary mechanism for mobilizing residual oil.

Wettability Alteration The composite effectively altered the wettability of rock surfaces from oil-wet to water-wet conditions. The most significant change was observed in SW modified with the PLA/Henna composite, where the contact angle decreased from 143° to 89°. This indicates that the composite enhances fluid displacement efficiency and oil phase mobility.

Core Flooding Performance Core flooding experiments validated the composite’s potential for industrial application by demonstrating substantial improvements in oil recovery. PLA-Henna-modified SW achieved a remarkable 85% recovery factor (RF) during the tertiary stage. This performance is significantly higher than that of FW (49.7%) and SW alone (61%). The enhanced recovery is attributed to the combined effects of IFT reduction, wettability alteration, and physical pore plugging, which improves sweep efficiency by redirecting fluid flow to previously unswept regions.

In conclusion, the PLA/Henna composite presents a sustainable and efficient solution for EOR applications. Its ability to reduce IFT, alter wettability, and improve sweep efficiency makes it a promising bio-based and biodegradable material for maximizing hydrocarbon recovery while minimizing environmental impact. Further research into its long-term stability and field-scale performance is recommended to fully realize its industrial potential.

Future work

Future work could focus on using new synthesis materials3,18,19,24,41 to further improve the performance of composites for enhanced oil recovery (EOR). The current study successfully demonstrated the potential of a Polylactic Acid (PLA)/Henna composite. Building on this, future research could explore:

Other natural fillers Investigating different natural plant-based materials as fillers for PLA, like Henna, which is rich in biopolymers and organic compounds. This could lead to composites with varying surface chemistry and particle structures.

Alternative biodegradable polymers Exploring other biodegradable and biocompatible polymers besides PLA as the matrix for the composite. This could help to optimize properties such as stability and degradation control in different reservoir environments.

Novel hybrid materials Combining PLA or other polymers with a wider range of materials, including other natural fillers, bio-based surfactants, or nanoparticles, to create new hybrid materials. This could lead to a synergistic effect, enhancing properties like dispersion stability and oil recovery efficiency beyond what is achievable with a single composite. The paper also mentions that PLA on its own lacks the varied surface chemistry and pore-blocking abilities needed for EOR.

Testing under different conditions The current study used synthetic brines and simulated reservoir conditions. Future work could involve testing new composite materials under a wider range of high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) conditions, and with different types of crude oil and reservoir rocks to better understand their performance in various real-world scenarios. This would also address the ecological concerns associated with synthetic chemicals and the need for economical and eco-friendly EOR agents.

Abbreviations

- PLA

Polylactic acid

- IFT

Interfacial tension

- EOR

Enhanced oil recovery

- HPHT

High-pressure, high-temperature

- PV

Pore volume

List of symbols

- Ө0

Initial contact angle

- Ө1

Contact angle after oil aging

- Ө2

Contact angle after tertiary fluid treatment

- IFT

Interfacial tension (mN/m)

- RF

Recovery factor (%)

- PLA/Henna

Polylactic acid-henna composite

- TDS

Total dissolved solids (ppm)

- FW

Formation water

- SW

Seawater

- PLAHF

PLA-Henna-formation water

- PLAHS

PLA-Henna-seawater

Author contributions

Formal study: Tariq Alkhrissat, Ranganathaswamy M K. Conceptualization: Tariq Alkhrissat, Jasgurpreet Singh Chohan. Coding: Ali Raqee Abdulhadi, Jasgurpreet Singh Chohan, Ahmad Abumalek. Manuscript writing: Ali Raqee Abdulhadi, Ranganathaswamy M K. Manuscript editing: Muntadar Muhsen, Premananda Pradhan, Gauri Chauhan. Visualization: Muntadar Muhsen, Premananda Pradhan, Parveen Kumar. Validation: Parveen Kumar, Gauri Chauhan, Ahmad Abumalek.

Funding

There is no external funding source for this research.

Data availability

Data will be available at the academic request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This section is not applicable, and no human or animal is studied in this research.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Feng, G. et al. Novel facile nonaqueous precipitation in-situ synthesis of mullite whisker skeleton porous materials. Ceram. Int.44(18), 22904–22910 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng, G. et al. Luminescent properties of novel red-emitting M7Sn(PO4)6: Eu3+ (M= Sr, Ba) for light-emitting diodes. Luminescence33(2), 455–460 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng, G. et al. Preparation of novel porous hydroxyapatite sheets with high Pb2+ adsorption properties by self-assembly non-aqueous precipitation method. Ceram. Int.49(18), 30603–30612 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao, H., Xu, T. & Yu, H. Progress and prospects of EOR technology in deep, massive sandstone reservoirs with a strong bottom-water drive. Energy Geosci.5(1), 100164 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowrouzi, I., Mohammadi, A. H. & Khaksar Manshad, A. Benchmarking the potential of a resistant green hydrocolloid for chemical enhanced oil recovery from sandstone reservoirs. Can. J. Chem. Eng.103(1), 230–250 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khojastehmehr, M., Madani, M. & Daryasafar, A. Screening of enhanced oil recovery techniques for Iranian oil reservoirs using TOPSIS algorithm. Energy Rep.5, 529–544 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madani, M. et al. Fundamental investigation of an environmentally-friendly surfactant agent for chemical enhanced oil recovery. Fuel238, 186–197 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Najafi, S. A. S. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigation of CTAB microemulsion viscosity in the chemical enhanced oil recovery process. J. Mol. Liq.232, 382–389 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasankhani, G. M. et al. Experimental investigation of asphaltene-augmented gel polymer performance for water shut-off and enhancing oil recovery in fractured oil reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq.275, 654–666 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebouachera, S. E. I. et al. Mini-review on the evaluation of thermodynamic parameters for surfactants adsorption onto rock reservoirs: cEOR applications. Chem. Pap. (2024).

- 11.Golab, E. G. et al. Synthesis of hydrophobic polymeric surfactant (Polyacrylamide/Zwitterionic) and its effect on enhanced oil recovery (EOR). Chem. Phys. Impact9, 100756 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebouachera, S. E. I. et al. Experimental design methodology as a tool to optimize the adsorption of new surfactant on the Algerian rock reservoir: cEOR applications. Eur. Phys. J. Plus134(9), 436 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khezerlooe-ye Aghdam, S. et al. Mechanistic assessment of Seidlitziarosmarinus-derived surfactant for restraining shale hydration: A comprehensive experimental investigation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.147, 570–578 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khezerloo-ye Aghdam, S., Kazemi, A. & Ahmadi, M. Theoretical and experimental study of fine migration during low-salinity water flooding: Effect of brine composition on interparticle forces. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng.26(02), 228–243 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai, T. et al. Waste glass powder as a high temperature stabilizer in blended oil well cement pastes: Hydration, microstructure and mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater.439, 137359 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng, G. et al. Low-temperature preparation of novel stabilized aluminum titanate ceramic fibers via nonhydrolytic sol-gel method through linear self-assembly of precursors. Ceram. Int.45(15), 18704–18709 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng, G. et al. A novel red phosphor NaLa4(SiO4)3F:Eu3+. Mater. Lett.65(1), 110–112 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng, G. et al. Synthesis and luminescent properties of novel red-emitting M7Sn(PO4)6: Eu3+ (M= Sr, Ba) phosphors. Process. Appl. Ceram.12(1), 8–12 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng, G. et al. Novel nonaqueous precipitation synthesis of alumina powders. Ceram. Int.43(16), 13461–13468 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bashir, A., Sharifi Haddad, A. & Rafati, R. A review of fluid displacement mechanisms in surfactant-based chemical enhanced oil recovery processes: Analyses of key influencing factors. Petrol. Sci.19(3), 1211–1235 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saberi, H., Karimian, M. & Esmaeilnezhad, E. Performance evaluation of ferro-fluids flooding in enhanced oil recovery operations based on machine learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.132, 107908 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zulkifli, N. N. et al. Evaluation of new surfactants for enhanced oil recovery applications in high-temperature reservoirs. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol.10(2), 283–296 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosalman Haghighi, O. & Mohsenatabar Firozjaii, A. An experimental investigation into enhancing oil recovery using combination of new green surfactant with smart water in oil-wet carbonate reservoir. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol.10(3), 893–901 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng, G. et al. Synthesis and luminescence properties of Al2O3@ YAG: Ce core–shell yellow phosphor for white LED application. Ceram. Int.44(7), 8435–8439 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng, G. et al. A novel green nonaqueous sol-gel process for preparation of partially stabilized zirconia nanopowder. Process. Appl. Ceram.11(3), 220–224 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu, K. L. et al. Study on Mullite Whiskers Preparation via Non-hydrolytic Sol-Gel Process Combined with Molten Salt Method (Trans Tech Publications, Bäch, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin, C. et al. Elasto-plastic solution for tunnelling-induced nonlinear responses of overlying jointed pipelines in sand. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol.152, 105953 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosseini, S. et al. Effect of combination of cationic surfactant and salts on wettability alteration of carbonate rock. Energy Sources, Part A Recovery, Util. Environ. Effects46(1), 9692–9708 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian, K. et al. Effect of amphiphilic CaCO3 nanoparticles on the plant surfactant saponin solution on the oil-water interface: A feasibility research of enhanced oil recovery. Energy Fuels37(17), 12854–12864 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abang, G.N.-O., Pin, Y. S. & Ridzuan, N. Application of silica (SiO2) nanofluid and Gemini surfactants to improve the viscous behavior and surface tension of water-based drilling fluids. Egypt. J. Pet.30(4), 37–42 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yunita, P., Irawan, S. & Kania, D. Optimization of water-based drilling fluid using non-ionic and anionic surfactant additives. Procedia Eng.148, 1184–1190 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao, Y. et al. Low temperature preparation of aluminum titanate film via sol-gel method. Adv. Mater. Res.936, 238–242 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang, X. et al. Effects of sodium sources on nonaqueous precipitation synthesis of β″-Al2O3 and formation mechanism of uniform ionic channels. Langmuir41(3), 2044–2052 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, Z. et al. Constructing multiple sites porous organic polymers for highly efficient and reversible adsorption of triiodide ion from water. Green Energy Environ. (2025).

- 35.Sun, L. et al. Ultralight and superhydrophobic perfluorooctyltrimethoxysilane modified biomass carbonaceous aerogel for oil-spill remediation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.174, 71–78 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya, S. & Samanta, S. K. Soft-nanocomposites of nanoparticles and nanocarbons with supramolecular and polymer gels and their applications. Chem. Rev.116(19), 11967–12028 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammed, K. A. et al. Effect of various polymer types on Fe2O3 nanocomposite characteristics: insights from microstructural morphological, optical and band gap analyses. Polym. Bull.81(15), 13941–13958 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan, S. et al. An overview of inorganic polymer as potential lubricant additive for high temperature tribology. Tribol. Int.102, 620–635 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parizad, A., Shahbazi, K. & Tanha, A. A. Enhancement of polymeric water-based drilling fluid properties using nanoparticles. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng.170, 813–828 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng, G., Jiang, W.-H. & Liu, J.-M. Luminescent properties of a novel reddish-orange phosphor Eu-activated KLaSiO4. Mater. Sci.-Pol.37(2), 296–300 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng, G. et al. Synthesis and characterization of dense core-shell particles prepared by non-solvent displacement nonaqueous precipitation method taking C@ ZrSiO4 black pigment preparation as the case. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun.57, 100748 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng, G. et al. Non-solvent displacement nonaqueous precipitation method for core-shell materials preparation: Synthesis of C@ ZrSiO4 black pigment. Ceram. Int.49(23), 38148–38156 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng, G. et al. Nonaqueous precipitation combined with intermolecular polycondensation synthesis of novel HAp porous skeleton material and its Pb2+ ions removal performance. Ceram. Int.50(11), 19757–19768 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbood, N. K., Obeidavi, A. & Hosseini, S. Investigation on the effect of CuO nanoparticles on the IFT and wettability alteration at the presence of [C12mim][Cl] during enhanced oil recovery processes. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol.12(7), 1855–1866 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abbood, N. K. et al. Effect of SiO2 nanoparticles + 1-dodecyl-3-methyl imidazolium chloride on the IFT and wettability alteration at the presence of asphaltenic-synthetic oil. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol.12(11), 3137–3148 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Negin, C., Ali, S. & Xie, Q. Application of nanotechnology for enhancing oil recovery–a review. Petroleum2(4), 324–333 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lashari, N. et al. Impact of a novel HPAM/GO-SiO2 nanocomposite on interfacial tension: Application for enhanced oil recovery. Petrol. Sci. Technol.40(3), 290–309 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, Y. et al. Injectable polyzwitterionic lubricant for complete prevention of cardiac adhesion. Macromol. Biosci.23(4), 2200554 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu, W. & Liang, J.-Y. Defect-engineered rGO−CoNi2S4 with enhanced electrochemical performance for asymmetric supercapacitor. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China35(2), 563–578 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang, Q. et al. A smart mitochondria-targeting TP-NIR fluorescent probe for the selective and sensitive sensing of H2S in living cells and mice. New J. Chem.45(16), 7315–7320 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang, Q. et al. Rationally constructed de novo fluorescent nanosensor for nitric oxide detection and imaging in living cells and inflammatory mice models. Anal. Chem.95(4), 2452–2459 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, Y. et al. Rational construction of a fluorescent sensor for simultaneous detection and imaging of hypochlorous acid and peroxynitrite in living cells, tissues and inflammatory rat models. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.282, 121691 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hatzignatiou, D. G., Giske, N. H. & Stavland, A. Polymers and polymer-based gelants for improved oil recovery and water control in naturally fractured chalk formations. Chem. Eng. Sci.187, 302–317 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, C. et al. A novel system for reducing CO2-crude oil minimum miscibility pressure with CO2-soluble surfactants. Fuel281, 118690 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drexler, S. et al. Effect of CO2 on the dynamic and equilibrium interfacial tension between crude oil and formation brine for a deepwater pre-salt field. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng.190, 107095 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pal, N., Vajpayee, M. & Mandal, A. Cationic/nonionic mixed surfactants as enhanced oil recovery fluids: Influence of mixed micellization and polymer association on interfacial, rheological, and rock-wetting characteristics. Energy Fuels33(7), 6048–6059 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henton, D. E. et al. Polylactic acid technology. In Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites 559–607 (CRC Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davachi, S. M. & Kaffashi, B. Polylactic acid in medicine. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng.54(9), 944–967 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taghavi Fardood, S. et al. A novel green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using a henna extract powder. J. Struct. Chem.59, 1737–1743 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mehrmand, N., Moraveji, M. K. & Parvareh, A. Adsorption of Pb (II), Cu (II) and Ni (II) ions from aqueous solutions by functionalised henna powder (Lawsonia Inermis); isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.102(1), 1–22 (2022).39421269 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ali, J. A. et al. Emerging applications of TiO2/SiO2/poly(acrylamide) nanocomposites within the engineered water EOR in carbonate reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq.322, 114943 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang, Y. et al. Effect of temperature on mineral reactions and fines migration during low-salinity water injection into Berea sandstone. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng.202, 108482 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farhadi, H., Ayatollahi, S. & Fatemi, M. The effect of brine salinity and oil components on dynamic IFT behavior of oil-brine during low salinity water flooding: Diffusion coefficient, EDL establishment time, and IFT reduction rate. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng.196, 107862 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dashtaki, S. R. M. et al. Experimental investigation of the effect of Vitagnus plant extract on enhanced oil recovery process using interfacial tension (IFT) reduction and wettability alteration mechanisms. J. Petrol. Explor. Prod. Technol.10(7), 2895–2905 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamal, M. S., Hussein, I. A. & Sultan, A. S. Review on surfactant flooding: Phase behavior, retention, IFT, and field applications. Energy Fuels31(8), 7701–7720 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ali, M. et al. Assessment of wettability and rock-fluid interfacial tension of caprock: Implications for hydrogen and carbon dioxide geo-storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy47(30), 14104–14120 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang, W. et al. Effect of surfactant-assisted wettability alteration on immiscible displacement: A microfluidic study. Water Resour. Res.57(8), e2020WR029522 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Namaee-Ghasemi, A. et al. Geochemical simulation of wettability alteration and effluent ionic analysis during smart water flooding in carbonate rocks: Insights into the mechanisms and their contributions. J. Mol. Liq.326, 114854 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Saedi, H. N., Flori, R. E. & Brady, P. V. Effect of divalent cations in formation water on wettability alteration during low salinity water flooding in sandstone reservoirs: Oil recovery analyses, surface reactivity tests, contact angle, and spontaneous imbibition experiments. J. Mol. Liq.275, 163–172 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khezerloo-ye Aghdam, S., Kazemi, A. & Ahmadi, M. Studying the effect of surfactant assisted low-salinity water flooding on clay-rich sandstones. Petroleum10(2), 306–318 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kazemi, A., Khezerloo-ye Aghdam, S. & Ahmadi, M. Theoretical and experimental investigation of the impact of oil functional groups on the performance of smart water in clay-rich sandstones. Sci. Rep.14(1), 20172 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aghdam, S.K.-Y., Kazemi, A. & Ahmadi, M. Studying the effect of various surfactants on the possibility and intensity of fine migration during low-salinity water flooding in clay-rich sandstones. Results Eng.18, 101149 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dong, Z. et al. A novel method for automatic quantification of different pore types in shale based on SEM-EDS calibration. Mar. Petrol. Geol.173, 107278 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heidarpour, M. et al. New magnetic nanocomposite Fe3O4@Saponin/Cu(II) as an effective recyclable catalyst for the synthesis of aminoalkylnaphthols via Betti reaction. Steroids191, 109170 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. Detailed FTIR spectroscopy characterization of crude oil extracted asphaltenes: Curve resolve of overlapping bands. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng.185, 106618 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ovchinnikov, O. V. et al. Manifestation of intermolecular interactions in FTIR spectra of methylene blue molecules. Vib. Spectrosc.86, 181–189 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available at the academic request from the corresponding author.