Abstract

Background

Pomegranate consumption may have a beneficial effect on glucose control and insulin resistance due to its bioactive compounds. However, the results of available clinical trials are inconsistent. To address these inconsistencies, we conducted a meta-analysis of 34 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluating the effects of pomegranate on glycemic parameters in adults.

Methods

A thorough search was conducted across multiple databases until December 2024 to identify trials that investigated the impact of pomegranate on glucose control and insulin sensitivity. We calculated the effect size, reported as the weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), based on the net changes in fasting blood glucose (FBS), insulin, HOMA-IR, and Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

Results

Among the 407 records, this meta-analysis included 34 eligible RCTs involving 1500 participants. Pomegranate consumption was significantly associated with a reduction in FBS (WMD: -3.036 mg/dl; 95% CI, -4.273 to -1.799, P < 0.001, Tau2 = 6.039, I2 = 89.22%), insulin (WMD: -0.967 IU/mL; 95% CI, -1.486 to -0.448, P < 0.001, Tau2 = 0.761, I2 = 83.82%), HOMA-IR (WMD: -0.338; 95% CI, -0.470 to -0.205, P < 0.001, Tau2 = 0.031, I2 = 84.96%), and QUICKI (WMD: 0.003; 95% CI, 0.001 to 0.006, P = 0.011, Tau2 = 0.00, I2 = 7.11%), whereas changes in HbA1c (WMD: 0.046, 95% CI: -0.207 to 0.298, P = 0.723, Tau2 = 0.081, I2 = 60.62%) were not statistically significant. The non-linear dose-response analysis showed a significant association between the pomegranate dose and FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.006). Also, the duration of pomegranate consumption showed a significant non-linear relationship with FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.022) and insulin (P for non-linearity = 0.030). We did not find a significant non-linear association between the dosage of pomegranate juice and FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.83), insulin (P for non-linearity = 0.51), and duration of pomegranate extract with FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.30).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests that the consumption of pomegranate products can result in positive effects on FBS, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, and QUICKI in adults. More RCTs with longer duration and larger sample sizes are needed to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40795-025-01138-7.

Keywords: Pomegranate, Glycemic profile, Meta-analysis, Dose-response

Introduction

Diabetes, one of the top 10 causes of death among adults, is a serious, long-term condition with a major impact on the lives and well-being of individuals, families, and societies worldwide. The global diabetes prevalence in 2019 was estimated at 9.3% (463 million people), expected to rise to 10.2% (578 million) by 2030, and 10.9% (700 million) by 2045 [1]. Individuals with diabetes are at high risk for both microvascular complications (including retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (such as cardiovascular comorbidities), owing to hyperglycemia and components of insulin resistance syndrome (metabolic syndrome) [2–4].

Guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes have in recent years included lifestyle treatments, such as functional foods, as a way to improve glycemic levels and their related complications [5, 6]. Natural plant and fruit compounds have gained popularity for their therapeutic properties and safety, making them commonly used in disease prevention and treatment [7, 8]. Pomegranate is an ancient fruit known worldwide for its medicinal and dietary uses; it grows in different geographical areas, including the Mediterranean, Asia, and California [9]. Studies suggest that the different parts of the pomegranate, including the fruit, flower, seed, and peel, may play a role in managing metabolic disorders and some chronic diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, kidney disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and diabetes mellitus [10, 11]. Pomegranate phytochemicals like polyphenols (flavonoids, punicalagin, and gallic acid and ellagic acid), terpenoids, oleanolic and ursolic acids could exert their beneficial effects by reducing oxidative stress [12], inflammation [13, 14], metabolic syndrome [15], and glycemic dysregulation [9, 15, 16]. Since punicalagin in pomegranates inhibits α-amylase, allowing for a slower release of glucose and a reduction in blood glucose levels. Moreover, peripheral insulin levels decreased significantly in both healthy individuals and those with T2DM who received a single oral dose of 1.5 mL of fresh pomegranate juice per kg of body weight while fasting. This suggests that consuming fresh pomegranate juice could be utilized as a preventive measure as well as a supplemental treatment for people who have hyperglycemia [12, 17].

Multiple clinical trials have examined the impact of pomegranate on glycemic profiles across diverse populations [13, 14, 18–21]. There is considerable inconsistency regarding the net effect of pomegranate on glycemic indices among available RCTs. Studies have shown that pomegranate products can positively affect glycemic profiles [22–24], while others have reported no beneficial effect compared to controls [14, 18, 25]. The contradictory outcomes of the conducted studies, which vary in population type, sample size, and the pomegranate products used, suggest that a meta-analysis may be essential for summarizing the results. Some meta-analyses have been conducted in this field [26–28]. Jandari et al. (2020) included 7 RCTs with 350 participants with diabetes and found no significant beneficial effects of pomegranate on glycemic profiles [26]. Similarly, Huang et al. (2017), which included 18 RCTs with 538 participants, did not observe this result [27]. The most recent meta-analysis by Bahari et al. (2024) incorporated 32 eligible studies to examine the effects of pomegranate consumption on fasting blood sugar (FBS), fasting insulin, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in adults. The findings indicate that pomegranate intake has a positive effect on glycemic indices in adults [28].

We performed a dose-response analysis in our study, which, to our knowledge, has not been addressed in any prior research. This can provide a more comprehensive and clearer summary of the effect of pomegranate on glycemic profiles. Furthermore, we also analyzed QUICKI (Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index), which was rarely reported in previous meta-analyses. Additionally, we included four articles that were not included in the recent meta-analysis [29–32]. In this meta-analysis, we aimed to determine the optimal dose and duration of pomegranate product consumption that affects the blood glycemic profile in adults by performing a dose-response analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

The guidelines of the PRISMA statement served as the basis for our meta-analysis design (Supplementary Table 1) [33]. A search was conducted in the PubMed, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases for English articles on relevant RCTs exploring the influence of pomegranate on glycemic profile until December 2024, using MeSH terms and related keywords. Details of the search strategy for PubMed, Scopus, and ISI Web of Science databases are provided in Supplementary Table 2, available online as supporting information. Moreover, we performed a manual search in the reference lists of available meta-analyses and reviews related to this topic. The registration code of our study protocol at PROSPERO is CRD42024455359.

Study selection

Two independent investigators (F.MZ. and F.Sh.H.) thoroughly examined the titles and abstracts of all identified studies to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion involving a third investigator (S.A.K.). The inter-rater agreement was considered substantial, with a Kappa statistic of 0.68. According to established guidelines, Kappa coefficients between 0.61 and 0.80 reflect a high level of agreement among raters [34]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a placebo-controlled trial with a parallel or crossover design; (2) The article contains information on how pomegranate products affect glycemic profiles and any other information that would allow for the calculation of mean and SD changes; (3) The study was conducted on adults aged over 18 years; (4) A control group was used in the study, allowing for the extraction of information on the intervention and control groups at the start and conclusion of the study; (5) The assessment of grey literature was conducted to gather additional insights. The exclusion criteria for the studies included: 1) non-RCTs, in vitro and in vivo studies, review studies, and studies without reported SDs, SEs, or 95% CIs at baseline and the end of the study in both intervention and control groups.

Data extraction

Two authors (F.MZ. and F.Sh.H) conducted an independent review of eligible RCTs. Data extraction was performed using a standardized form. Studies were selected based on clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The information included the first author’s name, publication year, location, study design, gender, duration, total number of participants, number of female and male participants, mean age, type of pomegranate supplement, dosage, intervention population, and mean BMI of participants [35].

Quality assessment

Two independent investigators (S.M.Gh and A.H.) evaluated the quality of the studies included. The discrepancies were addressed through a discussion that included a third investigator (S.A.K.). The included studies were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane criteria . To assess the quality of studies, multiple factors were taken into account, including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other possible sources of bias. L (for low risk of bias), H (for high risk of bias), and U (for unclear risk of bias) were used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality assessment

| Study | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants And personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective outcome reporting |

Other potential threats to validity |

General risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abedini et al. 2021 [18] | L | L | H | U | L | H | L | Moderate |

| Akbarpour et al. 2021 [22] | U | H | H | U | L | H | L | High |

| Akkus et al. 2023 [32] | L | U | L | U | L | L | L | Low |

| Ammar et al. 2016 [53] | H | H | L | L | U | U | L | Moderate |

| Asgary et al. 2014 [13] | H | H | H | H | L | H | L | High |

| Babaeian et al. 2013 [14] | U | U | H | H | L | L | U | Moderate |

| Barghchi et al. 2023 [29] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Cerda et al. 2006 [49] | U | U | L | U | L | H | L | Moderate |

| Eghbali et al. 2021 [7] | U | U | L | H | H | U | L | Moderate |

| Esmaeilinezhad et al. 2019 [19] | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | Low |

| Faghihimani et al. 2016 [20] | L | U | L | U | L | L | L | Low |

| Fuster-Muñoz et al. 2016 [50] | L | L | L | L | L | H | L | Low |

| González-Ortiz et al. 2011 [51] | U | U | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Goodarzi et al. 2021 [21] | L | U | L | U | H | L | L | Low |

| Grabeža 2020 [57] | U | H | L | U | L | L | L | Low |

| Hajimahmoodi et al. 2009 [46] | U | U | L | H | H | U | U | Moderate |

| Hajizade et al. 2023 [31] | H | H | H | H | L | H | H | High |

| Hashemi et al. 2021 [41] | L | L | L | L | U | H | L | Low |

| Heber et al. 2007 [48] | U | H | U | U | L | H | L | Moderate |

| Hosseini et al. 2016 [23] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Khajebishak et al. 2019 [45] | L | U | L | U | L | L | L | Low |

| Kojadinovic et al. 2017 [55] | L | U | H | U | L | H | L | Moderate |

| Manthou et al. 2017 [56] | U | H | H | H | L | H | L | High |

| Mirmiran et al. 2010 [39] | L | H | L | U | L | H | L | Moderate |

| Moazzen et al. 2017 [40] | U | H | L | U | L | H | L | Moderate |

| Nemati et al. 2022 [24] | U | H | H | H | L | H | L | High |

| Park et al. 2014 [54] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Sohrab & Angoorani et al. 2015 [42] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Sohrab, Ebrahimof et al. 2016 [43] | U | L | H | H | L | H | L | High |

| Sohrab, Nasrollahzadeh et al. 2014 [25] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Sumner et al. 2005 [47] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Tsang et al. 2012 [52] | U | H | H | H | L | H | H | High |

| Zare et al. 2024 [30] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

| Zarezadeh et al. 2019 [44] | L | L | L | U | L | H | L | Low |

L: low risk of bias; H: high risk of bias; U: unclear risk of bias

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the influence of consumption of pomegranate products on glycemic profile changes in the following outcomes: FBS (mg/dl), insulin (IU/mL), HbA1c (%), HOMA-IR, and QUICKI. Effect sizes were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). WMD was estimated by calculating the mean difference (change score) in each study using the following formula: (measure at the end of follow-up in the treatment group − measure at baseline in the treatment group) − (measure at the end of follow-up in the control group − measure at baseline in the control group). To determine SD change when it is not reported, we utilized the formula (SD change = square root [(SD baseline² + SD final²) – (2 × r × SD baseline × SD final)]( with a correlation coefficient of 0.5, which is a cautious estimate between 0 and 1 [37]. In studies that used SE instead of SD, the following formula was used to calculate SD, where n is the number of subjects: SD = SE × square root (n). In assessing the statistical heterogeneity among the studies included in the analysis, we calculated the I² statistic, which measures the proportion of total variation across studies. The I² value was assessed to be greater than 50%, indicating significant heterogeneity. Furthermore, we employed Tau² to estimate the variance between the studies. A random-effects model was used to determine the pooled effect size when heterogeneity was present. The subgroup analyses were performed on different types of pomegranate, dosage of pomegranate juice and extracts, duration of consumption, participant BMI, participant sex, participant age, type of study, quality assessment, and study population. Furthermore, we investigated the association between doses and duration of pomegranate intake and outcomes, considering a non-linear dose-response relationship. Fractional polynomial modeling was employed to investigate the non-linear impact of pomegranate dosage on blood glucose and insulin levels. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of excluding one study on the pooled effect size. Funnel plots, Begg’s rank correlation, and Egger’s weighted regression tests were used to investigate publication bias. The analysis was adjusted for publication bias using Duval and Tweedie’s “trim and fill” and “fail-safe N” approaches [38]. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V3 software was used for all statistical analyses, with a p value of 0.05 considered statistically significant [35].

Grading the evidence

The assessment of evidence for major outcome indicators using the GRADE method took into account factors such as risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias, assigning each outcome a grade of “very low”, “low”, “moderate”, or “high” (Table 2).

Table 2.

GRADE profile of pomegranate for glycemic parameters

| Quality assessment | Summary of findings | Quality of evidence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Number of intervention/control |

WMD, 95%CI | |

| Blood glucose | No serious limitations | Very serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | 729 /684 | -3.036 mg/dl, 95% CI: -4.27, -1.79 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| Insulin | No serious limitations | Very serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | 514 /510 | -0.967 µU/ml, 95% CI: -1.48, -0.44 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| HOMA-IR | No serious limitations | Very serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | 503 /480 | -0.238, 95% CI: -0.259, -0.217 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| HbA1c | No serious limitations | Very serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | 239 /230 | 0.046, 95% CI: --0.207, 0.298 |

⊕ ⊕ ⊕ ◯ Moderate |

| QUICKI | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | 134/131 | 0.003, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.006 |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

Results

Study selection

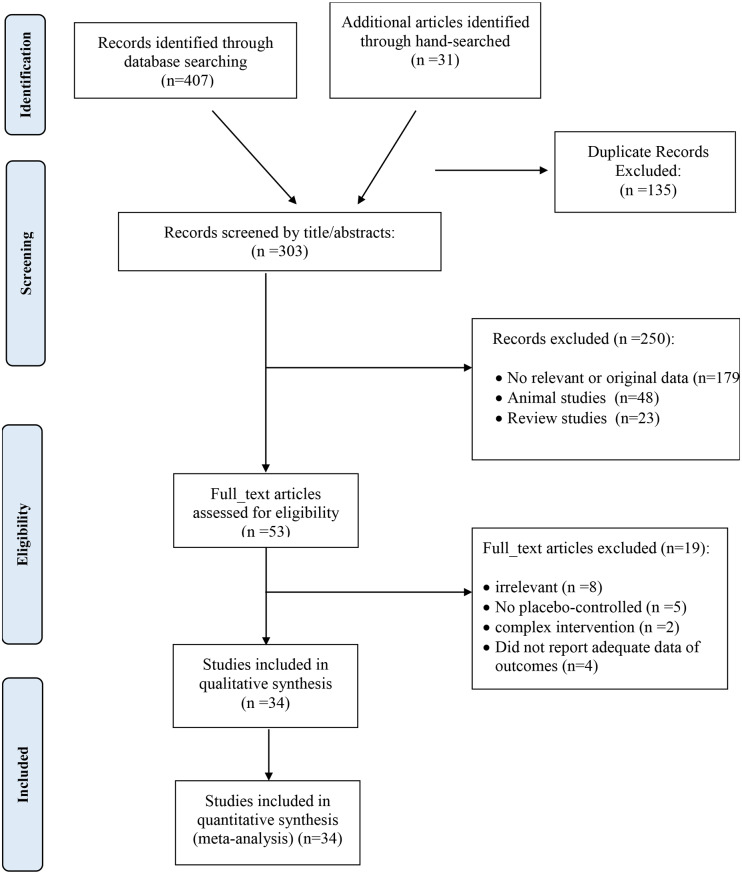

From the initial search, we identified 407 publications, excluding 135 duplicated studies. A total of 250 studies were screened based on title and abstract, with 179 being discarded attributed to unrelated titles, 48 for being animal studies, and 23 for being reviews. The remaining studies were then assessed in full text. A manual search of the reference lists of relevant reviews identified one additional trial. Of the remaining articles, 18 were excluded due to the following reasons: irrelevance (n = 8), absence of a placebo-controlled group (n = 5), complexity of intervention (n = 2), and insufficient outcome data (n = 4) (Supplementary Table 3). Ultimately, 34 studies satisfied our inclusion criteria. The flowchart depicting the literature search is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the number of studies identified and selected into the meta-analysis

Characteristics of included studies

We found 34 papers comprising 40 treatment arms that evaluated the effect of pomegranate on the blood glycemic profile. The main features of the included studies can be found in Supplementary Table 4. These studies were carried out in various countries, including Iran [7, 13, 14, 18–25, 29–31, 39–46], the USA [47, 48], Spain [49, 50], Mexico [51], Turkey [32], the UK [52], Tunisia [53], Korea [54], Serbia [55], Greece [56], and Bosnia and Herzegovina (58). The age of included participants ranged from 21 to 69 years; although most studies recruited both males and females, some studies only included males [24, 49, 50, 53] and females [7, 18, 19, 22, 31, 45, 54]. The pomegranate juice dosage fell within the range of 100 mL/day [22] to 750 mL/day [53]. The intervention durations ranged from 1 week (the shortest) [40] to 12 weeks (the longest) [21, 25, 30, 42, 47], while the sample size ranged from 10 [56] to 90 participants [30].

Quality assessment

Examining the general risk of bias showed that 17 trials [19–21, 23, 25, 29, 30, 32, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 50, 51, 54, 57] had low risk, 10 studies had moderate risk [7, 14, 18, 39, 40, 46, 48, 49, 53, 55], and 7 trials [13, 22, 24, 31, 43, 52, 56] had high risk of bias. Details of the risk of bias assessment are described in Table 1. According to the GRADE evidence profiles, the RCTs in our study had a range of evidence quality from low to high (Table 2).

Meta-analysis

The impact of pomegranate on fasting blood sugar levels

The results of this meta-analysis indicated a significant reduction in FBS with pomegranate consumption compared with the control group (WMD: -3.036 mg/dl; 95% CI, -4.273 to -1.799, P < 0.001). There was a significant level of variability and high heterogeneity among the studies (Tau2 = 6.039, I2 = 89.22%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In addition, we conducted several subgroup analyses to examine the potential divergent effects of pomegranate supplementation during the follow-up period (less than 8 weeks / 8 weeks or more), the type of supplement used (extract, seed oil, juice, powder, fruit), and the initial health condition of the participants (metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, other), study quality (high/low), supplementation dosage (> 500/≤ 500) for powder form, (< 250/≥250) for juice form, and baseline BMI of participant (< 30 kg/ /≥30 kg/

/≥30 kg/ ). The results of subgroup analysis showed that using the juice or extract form of pomegranate as intervention types at a dosage of < 250 mL/day or < 500 mg/day decreased FBS significantly. Moreover, subgroup analyses showed a significant reduction in FBS levels following pomegranate intake among participants aged under 50 years with type 2 diabetes, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m², and higher baseline FBS (≥ 100 mg/dL). Additionally, long-term pomegranate consumption (more than 8 weeks) resulted in a further decrease in FBS (Table 3).

). The results of subgroup analysis showed that using the juice or extract form of pomegranate as intervention types at a dosage of < 250 mL/day or < 500 mg/day decreased FBS significantly. Moreover, subgroup analyses showed a significant reduction in FBS levels following pomegranate intake among participants aged under 50 years with type 2 diabetes, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m², and higher baseline FBS (≥ 100 mg/dL). Additionally, long-term pomegranate consumption (more than 8 weeks) resulted in a further decrease in FBS (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot detailing weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of pomegranate on FBS

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of included randomized controlled trials in meta-analysis of the effect of pomegranate products on glycemic profile

| Group | No. of trials | WMD (95% CI) | P value | I2 (%) | P-heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS | |||||

| Pomegranate type | |||||

| Extract | 10 | -4.084(-6.189,-1.978) | 0.000 | 65.82 | 0.002 |

| Juice | 22 | -2.760(-4.832,-0.678) | 0.009 | 92.68 | 0.000 |

| powder | 3 | 0.801(-5.333,6.935) | 0.798 | 28.59 | 0.246 |

| Seed oil | 2 | -6.948(-27.665,13.769) | 0.511 | 71.22 | 0.062 |

| Fruit | 1 | 1.300(-3.109,5.709 | 0.563 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Dose (Mg/d) | |||||

| < 500 | 5 | -5.167(-7.085,-3.249) | 0.000 | 37.890 | 0.169 |

| ≥ 500 | 5 | -2.796(-7.756, 2.165) | 0.269 | 76.769 | 0.002 |

| Dose (ml/d) | |||||

| <250 | 13 | -3.002(-5.365,-0.638) | 0.013 | 93.44 | 0.000 |

| ≥250 | 10 | -1.678(-5.270, 1.914) | 0.36 | 71.68 | 0.000 |

| BMI | |||||

| < 30 | 20 | -0.957(-2.406,0.492) | 0.195 | 14.142 | 0.278 |

| ≥ 30 | 15 | -5.007 (-6.464,-3.549) | 0.000 | 91.397 | 0.000 |

| Duration (weeks) | |||||

| < 8 | 18 | -1.609(-3.633,0.414) | 0.119 | 73.021 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 8 | 20 | -5.149(-6.638,-3.660) | 0.000 | 87.907 | 0.000 |

| AGE | |||||

| < 50 | 18 | -4.176(-5.621,-2.723) | 0.000 | 93.465 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 50 | 20 | -0.933(-2.792,0.926) | 0.325 | 24.937 | 0.151 |

| FBS Baseline | |||||

| < 100 | 20 | -2.165(-4.065, -0.265) | 0.026 | 87.558 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 100 | 18 | -4.881(-7.417, -2.346) | 0.000 | 87.340 | 0.000 |

| Quality | |||||

| High | 10 | -4.445(-6.936, -1.954) | 0.000 | 95.892 | 0.000 |

| Low | 28 | -1.971(-4.039,0.097) | 0.062 | 75.085 | 0.000 |

| Gender | |||||

| Both | 19 | -1.623(-4.053,0.807) | 0.191 | 84.340 | 0.000 |

| Female | 10 | -1.582(-4.334,1.170) | 0.260 | 48.649 | 0.041 |

| Male | 6 | -6.815(-9.896,-3.735) | 0.000 | 95.933 | 0.000 |

| Population | |||||

| MS | 11 | -1.062(-3.678,1.553) | 0.426 | 65.156 | 0.001 |

| T2DM | 13 | -7.492(-10.453, -4.530) | 0.000 | 89.652 | 0.000 |

| Other | 14 | -2.345(-4.771, 0.081) | 0.058 | 89.320 | 0.000 |

| INSULIN | |||||

| Pomegranate type | |||||

| Extract | 6 | -2.254(-3.562,-0.946) | 0.001 | 77.742 | 0.000 |

| Juice | 13 | -0.287(-0.740,0.165) | 0.213 | 62.946 | 0.001 |

| Powder | 2 | -4.018(-12.491,4.456) | 0.353 | 95.005 | 0.000 |

| Seed oil | 3 | 0.134(-1.072-1.340) | 0.827 | 19.597 | 0.288 |

| Dose (Mg/d) | |||||

| < 500 | 2 | -0.919(-3.325,1.487) | 0.454 | 46.94 | 0.170 |

| ≥ 500 | 4 | -2.728(-4.263,-1.194) | 0.000 | 83.25 | 0.000 |

| Dose (ml/d) | |||||

| <250 | 7 | -0.171(-0.541,0.199) | 0.364 | 57.606 | 0.028 |

| ≥250 | 6 | -0.887(-2.454,0.679) | 0.267 | 68.479 | 0.007 |

| BMI | |||||

| < 30 | 13 | -0.522(-1.396,0.353) | 0.242 | 56.58 | 0.006 |

| ≥ 30 | 10 | -1.605(-2.344,-0.865) | 0.000 | 91.90 | 0.000 |

| Duration (weeks) | |||||

| < 8 | 6 | -0620(-2.843,1.604) | 0.585 | 91.32 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 8 | 18 | -0.694(-1.158,-0.231) | 0.003 | 69.56 | 0.000 |

| AGE | |||||

| < 50 | 13 | -1.416(-2.068,-0.764) | 0.000 | 88.8 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 50 | 11 | -0.500(-1.650,0.650) | 0.394 | 71.08 | 0.000 |

| Quality | |||||

| High | 5 | -0.202(-0.277,-0.127) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.444 |

| Low | 19 | -1.152(-2.188,-0.116) | 0.029 | 82.27 | 0.000 |

| Gender | |||||

| Both | 11 | -0.937(-1.840,-0.035) | 0.042 | 52.285 | 0.021 |

| Female | 7 | -0.973(-3.040,1.034) | 0.356 | 80.750 | 0.000 |

| Male | 2 | -0.214(-0.321,-0.106) | 0.000 | 17.206 | 0.272 |

| Population | |||||

| MS | 7 | -0.812(-3.294,1.670) | 0.521 | 92.57 | 0.000 |

| T2DM | 11 | -0.316(-0.663,0.030) | 0.000 | 46.89 | 0.042 |

| Other | 6 | -1.209(-1.884,-0.533) | 0.073 | 0.00 | 0.840 |

| HOMA-IR | |||||

| Pomegranate type | |||||

| Extract | 6 | -0.232(-0.838,0.374) | 0.454 | 90.074 | 0.000 |

| Juice | 10 | -0.230(-0.303,-0.157) | 0.000 | 49.723 | 0.036 |

| Powder | 2 | -0.868(-2.671,0.935) | 0.345 | 93.422 | 0.000 |

| Seed oil | 3 | -0.164(-0.843,0.514) | 0.635 | 69.188 | 0.039 |

| Dose (Mg/d) | |||||

| < 500 | 2 | 0.648(-1.946,3.241) | 0.625 | 92.906 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 500 | 7 | -0.373(-0.918,0.173) | 0.181 | 91.369 | 0.000 |

| Dose (ml/d) | |||||

| <250 | 5 | -0.226(-0.314,-0.138) | 0.000 | 75.323 | 0.003 |

| ≥250 | 5 | -0.305(-0.57,-0.040) | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.884 |

| BMI | |||||

| < 30 | 11 | -0.145(-0.443,0.152) | 0.339 | 55.419 | 0.013 |

| ≥ 30 | 9 | -0.463(-5.574,0.000) | 0.000 | 92.518 | 0.000 |

| Duration (weeks) | |||||

| < 8 | 5 | -0.463(-0.992,0.066) | 0.086 | 91.817 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 8 | 16 | -0.106(-0.358,-0.094) | 0.001 | 70.258 | 0.000 |

| AGE | |||||

| < 50 | 10 | -0.458(-0.600,-0.316) | 0.000 | 88.451 | 0.000 |

| ≥ 50 | 11 | 0.101(-0.567,0.354) | 0.651 | 80.007 | 0.000 |

| Quality | |||||

| High | 3 | -0.227(-0.262,-0.191) | 0.000 | 37.648 | 0.201 |

| Low | 18 | -0.301(-0.668,0.65) | 0.107 | 85.435 | 0.000 |

| Gender | |||||

| Both | 11 | -0.157(-0.613,0.300) | 0.502 | 72.470 | 0.000 |

| Female | 5 | -0.394(-1.129,0.143) | 0.380 | 82.794 | 0.000 |

| Male | 2 | -0.224(-0.263,-0.186) | 0.000 | 59.945 | 0.114 |

| Population | |||||

| MS | 6 | -0.471(-1.109,0.167) | 0.148 | 92.668 | 0.000 |

| T2DM | 9 | -0.215(-0.321,-0.110) | 0.000 | 70.348 | 0.000 |

| Other | 6 | -0.221(-0.549,0.106) | 0.186 | 58.938 | 0.027 |

| HbA1c | |||||

| Pomegranate type | |||||

| Extract | 3 | 0.081(-0.355,0.518) | 0.714 | 56.374 | 0.101 |

| Juice | 3 | -0.146(-0.389,0.098) | 0.241 | 0.000 | 0.887 |

| Powder | 1 | 0.740(0.332,1.148) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Seed oil | 2 | -0.138(-0.464,0.189) | 0.408 | 0.000 | 0.734 |

| BMI | |||||

| < 30 | 6 | 0.008(-0.241,0.256) | 0.952 | 27.769 | 0.226 |

| ≥ 30 | 3 | 0.135(-0.450,0.720) | 0.650 | 84.706 | 0.001 |

| AGE | |||||

| < 50 | 2 | -0.167(-0.458,0.125) | 0.263 | 0.000 | 0.841 |

| ≥ 50 | 9 | -0.114(-0.200,0.429) | 0.476 | 64.884 | 0.009 |

Effect of pomegranate intake on insulin

Pomegranate consumption significantly reduced insulin levels, according to the meta-analysis results (WMD: -0.967 IU/mL; 95% CI, -1.486 to -0.448, P < 0.001). There is significant heterogeneity among the studies (Tau2 = 0.761, I2 = 83.82%; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Based on subgroup analysis, the pomegranate extract intervention can decrease insulin levels. Specifically, the analysis found that long-term intervention (≥ 8 weeks), intervention with extract type in high dose (≥ 500 mg), intervention in obese participants (≥ 30 kg/m²), and participants aged < 50 years decreased insulin levels in participants with type 2 diabetes (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot detailing weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of pomegranate on insulin

Effect of pomegranate intake on HOMA-IR

The meta-analysis revealed a significant decrease in HOMA-IR with pomegranate consumption. (WMD: -0.338; 95% CI, -0.470 to -0.205, P < 0.001). There was a significant heterogeneity among the studies (Tau2 = 0.031, I2 = 84.96%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Based on subgroup analysis, pomegranate supplementation in juice form, at doses < 250 mL/day and ≥ 250 mL/day, resulted in a significant reduction in HOMA-IR. Moreover, long-term supplementation (≥ 8 weeks), intervention in obese participants (≥ 30 kg/m²), and participants aged < 50 years lowered HOMA-IR with type 2 diabetes (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot detailing weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of pomegranate on HOMA-IR

Effect of pomegranate intake on HbA1c

A total of 12 trials reported data on HbA1c. Compared with the control group, pomegranate intake did not significantly affect the HbA1c (WMD: 0.046; 95% CI, -0.207 to 0.298, P = 0.723). However, there was a significant heterogeneity among the studies (Tau2 = 0.081, I2 = 60.624%; P = 0.009) (Fig. 5). Based on the subgroup analysis, no association was observed between the effect of pomegranate juice or its extract on HbA1c (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot detailing weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of pomegranate on HbA1c

Effect of pomegranate intake on QUICKI

Five studies provided data on QUICKI, and pooling the data of these studies revealed that pomegranate supplementation had a significant effect on QUICKI (WMD: 0.003; 95% CI, 0.001 to 0.006, P = 0.011). The results indicate no variance between the studies and a very low degree of heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.00, I2 = 7.11%; P = 0.366) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot detailing weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of pomegranate on QUICKI

Duration and dosage of pomegranate intake have a non-linear impact on outcomes

The dose-response assessment reveals no significant non-linear associations between pomegranate juice and FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.83) or insulin (P for non-linearity = 0.51) (Figs. 7 and 8). However, a significant non-linear association was observed between the dosage of pomegranate extract and FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.006) (Fig. 9). The consumption of pomegranate extract at doses lower than 500 mg/day resulted in reduced FBS levels. The duration of pomegranate juice treatment showed a significant non-linear association with FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.022) and insulin (P for non-linearity = 0.03) (Figs. 10 and 11). In addition, the dose-response assessment did not show any significant non-linear association between the duration of pomegranate extract intake and FBS (P for non-linearity = 0.3) (Fig. 12).

Fig. 7.

Non-linear dose-response of the association between the dosage of pomegranate juice and weighted mean difference (WMD) of FBS

Fig. 8.

Non-linear dose-response of the association between the dosage of pomegranate juice and weighted mean difference (WMD) of insulin

Fig. 9.

Non-linear dose-response of the association between the dosage of pomegranate extract and weighted mean difference (WMD) of FBS

Fig. 10.

Non-linear dose-response of the association between the duration of pomegranate juice and weighted mean differences in FBS

Fig. 11.

Non-linear dose-response of the association between the duration of pomegranate juice and weighted mean difference (WMD) of insulin

Fig. 12.

Non-linear dose-response of the association between the duration of pomegranate extract and weighted mean difference (WMD) of FBS

Sensitivity analysis

Each study was removed from the analysis to understand the impact of individual trials on the overall effect size. None of the included studies, when removed, significantly affected the overall estimates for FBS, insulin, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR in the sensitivity analysis. However, the effects of pomegranate products on QUICKI were sensitive to the study performed by Esmaeilinezhad et al. [19]. Excluding this study from the analyses resulted in the effect of pomegranate products on QUICKI no longer being statistically significant (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis of the impact of pomegranate products on FBS (A), insulin (B), HbA1c (C), HOMA-IR (D), and QUICKI (E)

Publication bias

We performed Egger’s weighted regression test to analyze the presence of publication bias. The results indicated potential publication bias for FBS (P = 0.027), while no significant publication bias was detected for insulin (P = 0.947), HbA1c (P = 0.749), HOMA-IR (P = 0.562), and QUICKI (P = 0.770). To address this, we applied the trim and fill method to adjust for possible missing studies. After correction, the adjusted effect sizes remained consistent, suggesting that the overall findings are robust despite the presence of potential publication bias. Corrected effect sizes along with the outcomes of Begg’s rank correlation and ‘fail-safe N’ tests are presented in Table 4. Using the trim and fill method, 10, 2, 1, and 1 potentially missing studies were imputed for the meta-analyses of FBS, insulin, HbA1c, HOMA-IR, and QUICKI, respectively. The funnel plot is shown in Fig. 14.

Table 4.

Publication bias

| Corrected effect size | Begg’s rank correlation test | Egger’s linear regression test | Fail-safe N test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WMD | 95% CI | Kendall’s Tau | z-value | p-value | Intercept | 95% CI | t | df | p-value | N | |

| FBS | -5.06 | -6.25, -3.87 | -0.224 | 1.986 | 0.046 | 1.201 | 0.137,2.264 | 2.290 | 36 | 0.027 | 3818 |

| Isulin | -1.11 | -1.64, -0.58 | 0.029 | 0.198 | 0.842 | -0.93 | 0.53, -2.04 | 1.74 | 22 | 0.947 | 242 |

| Hb-A1C | 0.079 | -0.157, 0.315 | 0.361 | 01.355 | 0.175 | -0.514 | -4.182, 0.152 | 0.332 | 7 | 0.749 | 0 |

| HOMA-IR | -0.36 | -0.49, -0.22 | 0.143 | 0.905 | 0.364 | -0.374 | -1.706, 0.956 | 0.58 | 19 | 0.562 | 681 |

| Quicki | 0.003 | 0.001, 0.0006 | 0.10 | 0.244 | 0.806 | -0.37 | -4.08, 3.33 | 0.318 | 3 | 0.770 | 3 |

Fig. 14.

Funnel plot displaying publication bias in the studies reporting the impact of pomegranate products on FBS (A), insulin (B), HbA1c (C), HOMA-IR (D), and QUICKI (E). The “trim and fill” method was employed to estimate possibly missing studies. Open circles indicate published studies that have been observed, while closed circles signify unpublished studies that were imputed

Discussion

The effect of pomegranate on glycemic profiles has been reported inconsistently. This meta-analysis showed that pomegranate consumption significantly affects FBS, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, and QUICKI in adults. However, we found no significant effect on HbA1c. From a clinical perspective, the effect size observed in our study was statistically significant, yet not clinically meaningful. Therefore, it can be suggested that long-term health benefits of regular pomegranate intake may serve as a complementary dietary strategy for managing glycemic profiles.

The effect of pomegranate in reducing blood glucose has been stated in animal studies [58] and previous human experimental and clinical trial studies [23, 24, 29, 44]. Despite this, some studies revealed a slight or no decrease [14, 18, 19, 32], which may be a result of heterogeneity among studies.

The findings may be addressed by the mechanism of the pomegranate effect. Pomegranate contains phenolic compounds that can reduce blood glucose by inhibiting enzymes, insulin secretion, and protecting pancreatic tissue [59]. In vitro, the inhibition of α-glucosidase and α-amylase was selectively comparable to Acarbose [60]. Punicalagin and gallic acid in pomegranate have been shown to activate the transcription of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), which subsequently stimulates paraoxonase 2 )PON2( expression in macrophages. Increasing PPAR-γ activity can improve insulin sensitivity [61, 62]. In addition, pomegranate reduces inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin-6 (IL-6), chemokines, adhesion molecules, and COX-2 expression in the liver by downregulating the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway [63]. The expression of these factors is associated with systemic inflammation and insulin resistance [64]. On the other hand, research has indicated elevated circulating concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 in individuals with diabetes [65–67]. The polyphenols, mainly flavonoids, present in pomegranate juice had the capacity to prevent the oxidation of LDL by protecting it against oxidative damage caused by cellular processes [68]. Furthermore, pomegranates are rich in rutin and antioxidant compounds, such as vitamin C, which play a critical role in protecting the body from the detrimental effects of free radicals [69, 70]. Another study demonstrated that vitamin C supplementation, with or without rutin, can significantly reduce FBS; however, it does not appear to affect HbA1c, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR [71]. A study showed that pomegranate-derived ellagic acid inhibits resistin secretion by promoting the degradation of intracellular resistin protein in fat cells. Resistin, an adipocytokine, plays a role in linking obesity to type 2 diabetes [72].

Consistent with our results, in 2024, Bahari et al. published a meta-analysis with 32 RCTs to study the effects of pomegranate consumption on glycemic indices. Pomegranate consumption was associated with improvements in glycemic parameters, as evidenced by reductions in FBS, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR. However, the results regarding HbA1c were inconsistent [28]. In a meta-analysis conducted by Yin et al. in 2024, involving 15 RCTs, the findings demonstrated that pomegranate extract significantly improved HOMA-IR and fasting insulin levels in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). It also improved fasting insulin levels in individuals with T2DM and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [73]. Laurindo et al. in 2022 published a meta-analysis with 20 RCTs that showed that pomegranate can be advantageous in reducing FBS and HOMA-IR and improving insulin resistance [15]. In 2020, Jandari et al., based on 7 RCTs, concluded that pomegranate supplementation had no significant favorable effects on FBS, HOMA-IR, and HbA1c, while the subgroup analysis results of our meta-analysis showed significant effects on FBS and HOMA-IR in different populations of people with type 2 diabetes [26]. In the studies by Laurindo and Jandari, subgroup analyses were not performed due to the small number of selected trials. Contrary to our results, Huang et al. in 2017, with 16 RCTs, stated that consumption of pomegranate did not significantly affect FBS, fasting insulin, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR. Subgroup analysis was performed for study design, duration, type of intervention, health status, BMI baseline, and FBS levels, and none of the studied subgroups showed significant results [27]. This difference in results could be because of the smaller number of included studies. None of the published meta-analyses have performed a dose-response analysis. Several factors might influence our study results as well as those of other studies, including: (i) variations in age, gender, ethnicity, and baseline health conditions among participants, (ii) differences in the formulation of pomegranate extract or juice (such as variations in concentration and preparation methods) may influence both the bioavailability and efficacy of the intervention, thereby contributing to inconsistent outcomes, (iii) lifestyle factors such as physical activity levels and the individual dietary patterns of participants, such as consumption of fruits, vegetables, and processed foods, can significantly impact outcomes.

There are several strong points in our meta-analysis. Most of the studies included in this meta-analysis were of high quality (27 of 34 RCTs). These findings can be valuable and noteworthy for researchers and scientists, as they were gathered from available RCTs investigating the effect of pomegranate on the glycemic profile. However, several limitations need to be considered, and it is advisable to approach the results with caution. Our selection was limited to studies published in English; studies in other languages were excluded. Only 6 RCTs had over 50 participants, and the included RCTs had a moderate sample size. Moreover, the selected trials varied in sample size, administration and consumption time, baseline FBS, study quality, type of pomegranate intervention, and target population. In addition, the number of studies that reported HbA1c and QUICKI was low.

Future studies should include participants from diverse geographic regions and demographic backgrounds to enhance understanding of the effects of pomegranate consumption. Additionally, more research is needed to report on HbA1c and QUICKI for a clearer view of the long-term impacts on metabolic health. Exploring the biochemical pathways of pomegranate products is essential, and future trials should standardize protocols for administration and duration of interventions to improve comparability and reliability.

Conclusion

We found that pomegranate significantly reduced levels of FBS, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR in adults, particularly patients with T2DM, although its effect on HbA1c was not statistically significant. Incorporating pomegranate into the diet as a beneficial nutritional component has the potential to improve metabolic health. However, further research is essential to thoroughly elucidate its effects on glycemic profiles.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CI

Confidence Interval

- FBS

Fasting Blood Sugar

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- NAFL

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- PCOS

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- PON2

Paraoxonas

- QUICKI

Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trials

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SE

Standard Error

- TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α

- T2DM

Type 2 Diabetes

- WMD

Weighted Mean Difference

Author contributions

The authors’ contribution was as follows: F.M. and F.Sh. contributed to the statistical analysis; F.Sh.H. and F.M. conducted the systematic search, screening, and data extraction; S.M.Gh. and A.H. conducted the quality assessment; S.A.K. finalized the manuscript; and M.M. proofread the manuscript for native English writing; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine. 2010;38(11):602–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Groop L, Henry RR, Herman WH, Holst JJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Reviews Disease Primers. 2015;1(1):1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association AD. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu L, Li Y, Dai Y, Peng J. Natural products for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Pharmacology and mechanisms. Pharmacol Res. 2018;130:451–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association AD. Introduction: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Supplement1):S1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eghbali S, Askari SF, Avan R, Sahebkar A. Therapeutic effects of Punica granatum (Pomegranate): an updated review of clinical trials. J Nutr Metab. 2021;2021:5297162. 10.1155/2021/5297162. PMID: 34796029; PMCID: PMC8595036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhang Y-J, Gan R-Y, Li S, Zhou Y, Li A-N, Xu D-P, et al. Antioxidant phytochemicals for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Molecules. 2015;20(12):21138–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland D, Hatib K. Bar-Ya’akov I. Pomegranate: botany, horticulture, breeding. Hortic Reviews. 2009;35:127–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng J, Li J, Xiong R-G, Wu S-X, Huang S-Y, Zhou D-D, et al. Bioactive compounds and health benefits of pomegranate: an updated narrative review. Food Bioscience. 2023;53:102629. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akhtar S, Ismail T, Layla A. Pomegranate bioactive molecules and health benefits. Bioactive Molecules Food. 2019;3:1253–79. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bajaj S, Khan A. Antioxidants and diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asgary S, Sahebkar A, Afshani MR, Keshvari M, Haghjooyjavanmard S, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Clinical evaluation of blood pressure lowering, endothelial function improving, hypolipidemic and anti-inflammatory effects of pomegranate juice in hypertensive subjects. Phytother Res. 2014;28(2):193–9. 10.1002/ptr.4977. Epub 2013 Mar 21. PMID: 23519910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babaeian S, Ebrahimi Mameghani M, Niafar M, Sanaii S. The effect of unsweetened pomegranate juice on insulin resistance, high sensitivity C-reactive protein and obesity among type 2 diabetes patients. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci (JAUMS) [Internet]. 2013;13(1(47)):7–15. Available from: https://sid.ir/paper/392762/en [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurindo LF, Barbalho SM, Marquess AR, Grecco AIS, Goulart RA, Tofano RJ, et al. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) and metabolic syndrome risk factors and outcomes: A systematic review of clinical studies. Nutrients. 2022;14(8):1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banihani S, Swedan S, Alguraan Z. Pomegranate and type 2 diabetes. Nutr Res. 2013;33(5):341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bashan N, Kovsan J, Kachko I, Ovadia H, Rudich A. Positive and negative regulation of insulin signaling by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):27–71. 10.1152/physrev.00014.2008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Abedini M, Ghasemi-Tehrani H, Tarrahi MJ, Amani R. The effect of concentrated pomegranate juice consumption on risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2021;35(1):442–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmaeilinezhad Z, Babajafari S, Sohrabi Z, Eskandari MH, Amooee S, Barati-Boldaji R. Effect of synbiotic pomegranate juice on glycemic, sex hormone profile and anthropometric indices in PCOS: a randomized, triple blind, controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;29(2):201–8. 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.07.002. Epub 2018 Jul 17. PMID: 30538082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faghihimani Z, Mirmiran P, Sohrab G, Iraj B, Faghihimani E. Effects of pomegranate seed oil on metabolic state of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodarzi R, Jafarirad S, Mohammadtaghvaei N, Dastoorpoor M, Alavinejad P. The effect of pomegranate extract on anthropometric indices, serum lipids, glycemic indicators, and blood pressure in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2021;35(10):5871–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akbarpour M, Fathollahi Shoorabeh F, Mardani M, Amini Majd F. Effects of eight weeks of resistance training and consumption of pomegranate on GLP-1, DPP-4 and glycemic statuses in women with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr Food Sci Res. 2021;8(1):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosseini B, Saedisomeolia A, Wood LG, Yaseri M, Tavasoli S. Effects of pomegranate extract supplementation on inflammation in overweight and obese individuals: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;22:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nemati S, Tadibi V, Hoseini R. Pomegranate juice intake enhances the effects of aerobic training on insulin resistance and liver enzymes in type 2 diabetic men: a single-blind controlled trial. BMC Nutr. 2022;8(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohrab G, Nasrollahzadeh J, Zand H, Amiri Z, Tohidi M, Kimiagar M. Effects of pomegranate juice consumption on inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Res Med Sciences: Official J Isfahan Univ Med Sci. 2014;19(3):215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jandari S, Hatami E, Ziaei R, Ghavami A, Yamchi AM. The effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum) supplementation on metabolic status in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2020;52:102478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H, Liao D, Chen G, Chen H, Zhu Y. Lack of efficacy of pomegranate supplementation for glucose management, insulin levels and sensitivity: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bahari H, Ashtary-Larky D, Goudarzi K, Mirmohammadali SN, Asbaghi O, Naderian M, et al. The effects of pomegranate consumption on glycemic indices in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews; 2024. p. 102940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barghchi H, Milkarizi N, Belyani S, Norouzian Ostad A, Askari VR, Rajabzadeh F, et al. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peel extract ameliorates metabolic syndrome risk factors in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Nutr J. 2023;22(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zare M, Tarrahi MJ, Sadeghi O, Karimifar M, Goli SAH, Amani R, et al. Effects of bread fortification with pomegranate peel powder on inflammation biomarkers, oxidative stress, and mood status in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Food Sci Nutr. 2025;13(8):e70577. 10.1002/fsn3.70577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hajizade F, Mogharnasi M, Ghahremani R, Kazemi T. Effect of four weeks of pomegranate supplementation and exercise at home on cardiac electrical activity and lipid profile in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2023;30(1):44–55. http://journal.bums.ac.ir/article-1-3248-en.html

- 32.Akkuş ÖÖ, Metin U, Çamlık Z. The effects of pomegranate Peel added bread on anthropometric measurements, metabolic and oxidative parameters in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Nutr Res Pract. 2023;17(4):698–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85(3):257–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borenstein M, Rothstein H. Comprehensive meta-analysis: Biostat; 1999.

- 36.Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1. 0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook cochrane org. 2011:243 – 96.

- 37.Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2008.

- 38.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mirmiran P, Fazeli MR, Asghari G, Shafiee A, Azizi F. Effect of pomegranate seed oil on hyperlipidaemic subjects: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(3):402–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moazzen H, Alizadeh M. Effects of pomegranate juice on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with metabolic syndrome: a Double-Blinded, randomized crossover controlled trial. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2017;72(2):126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seyed Hashemi M, Namiranian N, Tavahen H, Dehghanpour A, Rad MH, Jam-Ashkezari S, et al. Efficacy of pomegranate seed powder on glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement Med Res. 2021;28(3):226–33. English. 10.1159/000510986. Epub 2020 Dec 10. PMID: 33302270. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Sohrab G, Angoorani P, Tohidi M, Tabibi H, Kimiagar M, Nasrollahzadeh J. Pomegranate (Punicagranatum) juice decreases lipid peroxidation, but has no effect on plasma advanced glycated end-products in adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Food Nutr Res. 2015;59:28551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sohrab G, Ebrahimof S, Sotoudeh G, Neyestani T, Angoorani P, Hedayati M et al. Effects of pomegranate juice consumption on oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2016;17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Zarezadeh M, Saedisomeolia A, Hosseini B, Emami M. The effect of Punica granatum (Pomegranate) extract on inflammatory biomarkers, lipid profile and glycemic indices in patients with overweight and obesity: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2019;13:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khajebishak Y, Payahoo L, Alivand M, Hamishehkar H, Mobasseri M, Ebrahimzadeh V, et al. Effect of pomegranate seed oil supplementation on the GLUT-4 gene expression and glycemic control in obese people with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(11):19621–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haji MM, Oveysi MR, Sadeghi N, Janat B, Nateghi M. Antioxidant capacity of plasma after pomegranate intake in human volunteers. Acta Medica Iranica. 2009;47(2):125–32. https://www.sid.ir/en/vewssid/j_pdf/86520090210.pdf

- 47.Sumner MD, Elliott-Eller M, Weidner G, Daubenmier JJ, Chew MH, Marlin R, et al. Effects of pomegranate juice consumption on myocardial perfusion in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(6):810–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heber D, Seeram NP, Wyatt H, Henning SM, Zhang Y, Ogden LG, et al. Safety and antioxidant activity of a pomegranate ellagitannin-enriched polyphenol dietary supplement in overweight individuals with increased waist size. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55(24):10050–4. 10.1021/jf071689v. Epub 2007 Oct 30. PMID: 17966977. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Cerdá B, Soto C, Albaladejo MD, Martínez P, Sánchez-Gascón F, Tomás-Barberán F, et al. Pomegranate juice supplementation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 5-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(2):245–53. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602309. PMID: 16278692. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Fuster-Muñoz E, Roche E, Funes L, Martínez-Peinado P, Sempere JM, Vicente-Salar N. Effects of pomegranate juice in circulating parameters, cytokines, and oxidative stress markers in endurance-based athletes: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition. 2016;32(5):539–45. 10.1016/j.nut.2015.11.002. Epub 2015 Dec 7. PMID: 26778544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.González-Ortiz M, Martínez-Abundis E, Espinel-Bermúdez MC, Pérez-Rubio KG. Effect of pomegranate juice on insulin secretion and sensitivity in patients with obesity. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;58(3):220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsang C, Smail NF, Almoosawi S, Davidson I, Al-Dujaili EA. Intake of polyphenol-rich pomegranate pure juice influences urinary glucocorticoids, blood pressure and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance in human volunteers. J Nutr Sci. 2012;1:e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ammar A, Turki M, Chtourou H, Hammouda O, Trabelsi K, Kallel C, et al. Pomegranate supplementation accelerates recovery of muscle damage and soreness and inflammatory markers after a weightlifting training session. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0160305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park JE, Kim JY, Kim J, Kim YJ, Kim MJ, Kwon SW, et al. Pomegranate vinegar beverage reduces visceral fat accumulation in association with AMPK activation in overweight women: A double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled trial. J Funct Foods. 2014;8:274–81. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kojadinovic MI, Arsic AC, Debeljak-Martacic JD, Konic-Ristic AI, Kardum ND, Popovic TB, et al. Consumption of pomegranate juice decreases blood lipid peroxidation and levels of arachidonic acid in women with metabolic syndrome. J Sci Food Agric. 2017;97(6):1798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manthou E, Georgakouli K, Deli CK, Sotiropoulos A, Fatouros IG, Kouretas D, et al. Effect of pomegranate juice consumption on biochemical parameters and complete blood count. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(2):1756–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grabež M, Škrbić R, Stojiljković MP, Rudić-Grujić V, Paunović M, Arsić A, et al. Beneficial effects of pomegranate Peel extract on plasma lipid profile, fatty acids levels and blood pressure in patients with diabetes mellitus type-2: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Funct Foods. 2020;64:103692. [Google Scholar]

- 58.dos Santos Friolli MP, de Souza MC, Sant’Ana MR, Veiga CB, Ramos C, Rostagno MA, et al. The potential of pomegranate Peel (Punica granatum) in the treatment of obese and glucose-intolerant mice. Brazilian J Dev. 2023;9(3):12220–41. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Virgen-Carrillo CA, Martínez Moreno AG, Valdés Miramontes EH. Potential hypoglycemic effect of pomegranate juice and its mechanism of action: a systematic review. J Med Food. 2020;23(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kam A, Li KM, Razmovski-Naumovski V, Nammi S, Shi J, Chan K, et al. A comparative study on the inhibitory effects of different parts and chemical constituents of pomegranate on α‐amylase and α‐glucosidase. Phytother Res. 2013;27(11):1614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shiner M, Fuhrman B, Aviram M. Macrophage paraoxonase 2 (PON2) expression is up-regulated by pomegranate juice phenolic anti-oxidants via PPARγ and AP-1 pathway activation. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195(2):313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang TH, Peng G, Kota BP, Li GQ, Yamahara J, Roufogalis BD, et al. Anti-diabetic action of Punica granatum flower extract: activation of PPAR-γ and identification of an active component. Toxicol Appl Pharmcol. 2005;207(2):160–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Husain H, Latief U, Ahmad R. Pomegranate action in curbing the incidence of liver injury triggered by diethylnitrosamine by declining oxidative stress via Nrf2 and NFκB regulation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wieser V, Moschen AR, Tilg H. Inflammation, cytokines and insulin resistance: a clinical perspective. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2013;61:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pickup J, Mattock M, Chusney G, Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pickup JC, Chusney GD, Thomas SM, Burt D. Plasma interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor α and blood cytokine production in type 2 diabetes. Life Sci. 2000;67(3):291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kado S, Nagase T, Nagata N. Circulating levels of interleukin-6, its soluble receptor and interleukin-6/interleukin-6 receptor complexes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 1999;36:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aviram M, Dornfeld L, Rosenblat M, Volkova N, Kaplan M, Coleman R, et al. Pomegranate juice consumption reduces oxidative stress, atherogenic modifications to LDL, and platelet aggregation: studies in humans and in atherosclerotic Apolipoprotein E–deficient mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5):1062–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maphetu N, Unuofin JO, Masuku NP, Olisah C, Lebelo SL. Medicinal uses, Pharmacological activities, phytochemistry, and the molecular mechanisms of Punica granatum L.(pomegranate) plant extracts: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zarfeshany A, Asgary S, Javanmard SH. Potent health effects of pomegranate. Adv Biomedical Res. 2014;3(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ragheb SR, El Wakeel LM, Nasr MS, Sabri NA. Impact of Rutin and vitamin C combination on oxidative stress and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;35:128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Makino-Wakagi Y, Yoshimura Y, Uzawa Y, Zaima N, Moriyama T, Kawamura Y. Ellagic acid in pomegranate suppresses resistin secretion by a novel regulatory mechanism involving the degradation of intracellular resistin protein in adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(2):880–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yin S, Zhu F, Zhou Q, Chen M, Wang X, Chen Q. Lack of efficacy of pomegranate supplementation on insulin resistance and sensitivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res. 2025;39(1):77–89. 10.1002/ptr.8362 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.