Abstract

The chemical conjugation of poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) to therapeutic agents, known as PEGylation, is a well-established strategy for enhancing drug solubility, chemical stability, and pharmacokinetics. Here, we report on a class of supramolecular polymeric prodrugs by utilizing oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) to modify the hydrophobic anticancer drug camptothecin (CPT). These OEGylated prodrugs, despite their low molecular weight, spontaneously self-assemble into therapeutic supramolecular polymers (SPs) with a tubular morphology, featuring a dense OEG coating on the surface. By designing biodegradable linkers with varying chemical stabilities, we investigated how the release kinetics of CPT influence the in vitro and in vivo performance of these SPs. Our findings demonstrate that self-assembling prodrugs (SAPDs) with a self-immolative disulfanyl-ethyl carbonate (etcSS) linker exhibit a faster drug release rate than those with a reducible disulfanyl butyrate (buSS) linker, leading to higher potency and significantly improved antitumor efficacy. Notably, two stable tubular SPs, Tubustecan (TT) 1E and TT 7E, outperformed irinotecan—a clinically approved CPT prodrug—in a colon cancer model, achieving enhanced tumor growth inhibition and prolonged animal survival. These results highlight the potential of supramolecular OEGylation as an important strategy for engineering drug-based supramolecular polymers and underscore the critical role of chemical stability vs. supramolecular stability in optimizing supramolecular prodrug design.

Keywords: Supramolecular polymer, peptide-drug conjugates, self-assembly, prodrug, OEGylation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Supramolecular polymers (SPs), formed through non-covalent interactions between monomeric units, offer some unique and important advantages for drug delivery.1–5 One unique feature is that the physiochemical properties of supramolecular nanostructures can be finely modulated via molecular and supramolecular crafting of the underlying building blocks.6–8 For instance, peptide assemblies can exhibit sequence-specific morphologies9–11 and structural sensitivity to amino acid positioning within isomeric sequences.12–16 In other examples, the self-assembly of monomers can be controlled by attachment and removal of enzyme-cleavable pendant chemical groups, enabling a sol-gel transition in a particular biological setting.17–22 SPs can also be further customized via supramolecular copolymerization, allowing precise control over composition and functionality.23–25

Leveraging the precise control over supramolecular morphology, self-assembling prodrugs (SAPDs) have emerged as a new class of drug-containing building blocks that spontaneously form therapeutic supramolecular polymers (SPs) in aqueous solution.26–27 This unique capability enables the development of self-formulating, self-delivering therapeutics, offering a promising strategy for improving drug stability and pharmacokinetic profiles.27–28 For example, rationally designed block copolymer-drug conjugates and polypeptide-drug conjugates can assemble into drug-containing micellar structures and nanoparticles.29–32 In addition, conjugating small-molecule drugs with short peptides had led to a library of self-assembling peptide-drug conjugates that form structually well-defined assemblies in aqueous solutions.33–36 In all these cases, the conjugated drugs are pivotal in shaping the assembly process, influencing the morphology and supramolecular stability of the resulting structures. Equally important is the selection of the chemical linker, which governs both the timing and mechanism of drug release in biological environments.37–38 While it is generally assumed that the chemical linker is embedded within the supramolecular structure upon assembly, its specific role—particularly in relation to the supramolecular stability of self-assembling prodrugs—remains unclear and requires further investigation.

Our lab has recently developed a series of self-assembling camptothecin (CPT) analogues, termed tubustecans (TTs), which form tubular SPs in aqueous solution by conjugating two CPT molecules to a short peptide.39 These TTs exhibit remarkable supramolecular stability and robust tubular assembly protocol, along with highly uniform diameters due to the highly ordered packing of CPT moieties. Additionally, the nanotubes' inner cavities can serve as reservoirs for low-molecular-weight hydrophobic compounds, enabling the co-delivery of multiple therapeutic agents. However, the water-soluble peptide components often carry charges due to their weak acid/base nature, which can lead to entanglement and consequent hydrogelation under physiological conditions, potentially limiting their use in systemic drug delivery.40–41 While poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) conjugation is considered the gold standard for imparting neutral surface chemistry and steric stabilization to pharmaceutical agents,42–44 we have come to realize that its conjugation to CPT units potentially disrupt its ability to assemble into stable tubustecan nanostructures. To optimize our TTs, we explore further the conjugation of oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) to lysine residues to develop a series of therapeutic SPs with an OEGylated surface suitable for systemic delivery. Through the strategic selection of two distinct linker chemistries, the resulting tubular SPs provide a robust platform to investigate the interplay between chemical and supramolecular stability, and how this relationship influences drug release, in vitro cytotoxicity, and in vivo therapeutic performance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular design and self-assembly.

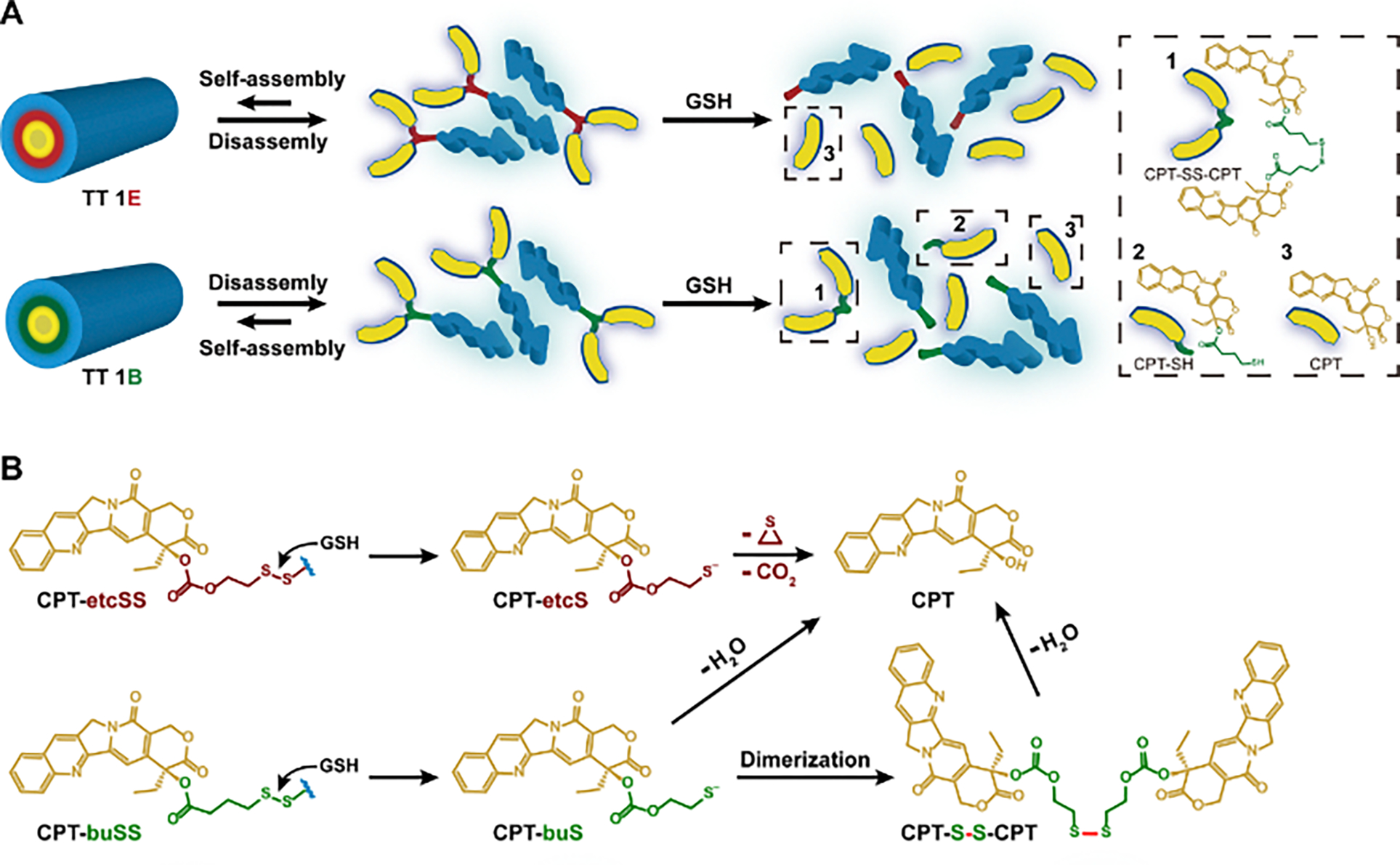

Figure 1A illustrates the chemical structures of tubustecan (TT 1), comprising two anticancer CPT units an OEGylated peptide, and a biodegradable linker that bridges the hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments while regulating drug release. CPT, a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor derived from Camptotheca acuminata,45 serves as the hydrophobic domain, providing strong associative π–π interactions that drive directional monomer assembly. The OEG moieties, conjugated to the lysine side chain, neutralize primary amine charges and act as nonionic hydrophilic auxiliaries. This amphiphilic design enables TT 1 to self-assemble into supramolecular nanostructures with a neutral surface chemistry, potentially enhancing its potential for systemic drug delivery. Given that prodrugs typically exhibit minimal cytotoxicity until they are converted into their active parent compounds, the assembled TTs must first disassemble into monomeric prodrugs before undergoing degradation into active free CPT. The disassembly process is primarily governed by supramolecular stability, which can be modulated by tuning the hydrophilic segments.46 In contrast, the subsequent conversion of monomeric prodrugs into active CPT is primarily governed by their intrinsic chemical stability, which is directly influenced by the choice of the linker chemistry. To investigate the impact of chemical stability on systemic drug delivery, we designed two TT derivatives: TT 1E, featuring a disulfanyl-ethyl carbonate (etcSS) linker, and TT 1B, containing a disulfanyl butyrate (buSS) linker (Figure 1A, S1, and S2). These biodegradable linkers were designed by replacing an oxygen with a carbon in their backbone, leading to distinct chemical stabilities.

Figure 1.

Monomer design and supramolecular assembly of OEGylated tubustecan 1 (TT 1) with different chemical stability. (A) Chemical structure of TT 1 with an etcSS linker (TT 1E) and a buSS linker (TT 1B), respectively. (B) Schematic illustration of self-assembly of TT 1 into tubular supramolecular polymers with the corresponding etcSS (E) or buSS (B) chemical linkers. Representative cryo-TEM images of SP TT 1E (C) and SP TT 1B (D) at the concentration of 2 mM. (E) Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of assembled TT 1E and TT 1B in water at the concentration of 200 μM.

When dissolved in water at neutral pH (2 mM), both TT 1E and TT 1B formed micrometer-long filamentous assemblies approximately 10 nm in width, as observed via cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) (Figure 1C and 1D). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra (Figure 1E) further confirmed nearly identical absorptions in both the chromophore (>250 nm) and peptide (~224 nm) regions, 33, 39 indicating that the tubular supramolecular packing within the self-assembled TT 1E and TT 1B remains largely unchanged. Collectively, TEM and CD studies demonstrate that modifying the linker chemistry in this particular case does not alter the self-assembly behavior of the TTs, yielding two SPs with distinct chemical stabilities (Figure 1B).

In Vitro therapeutic release.

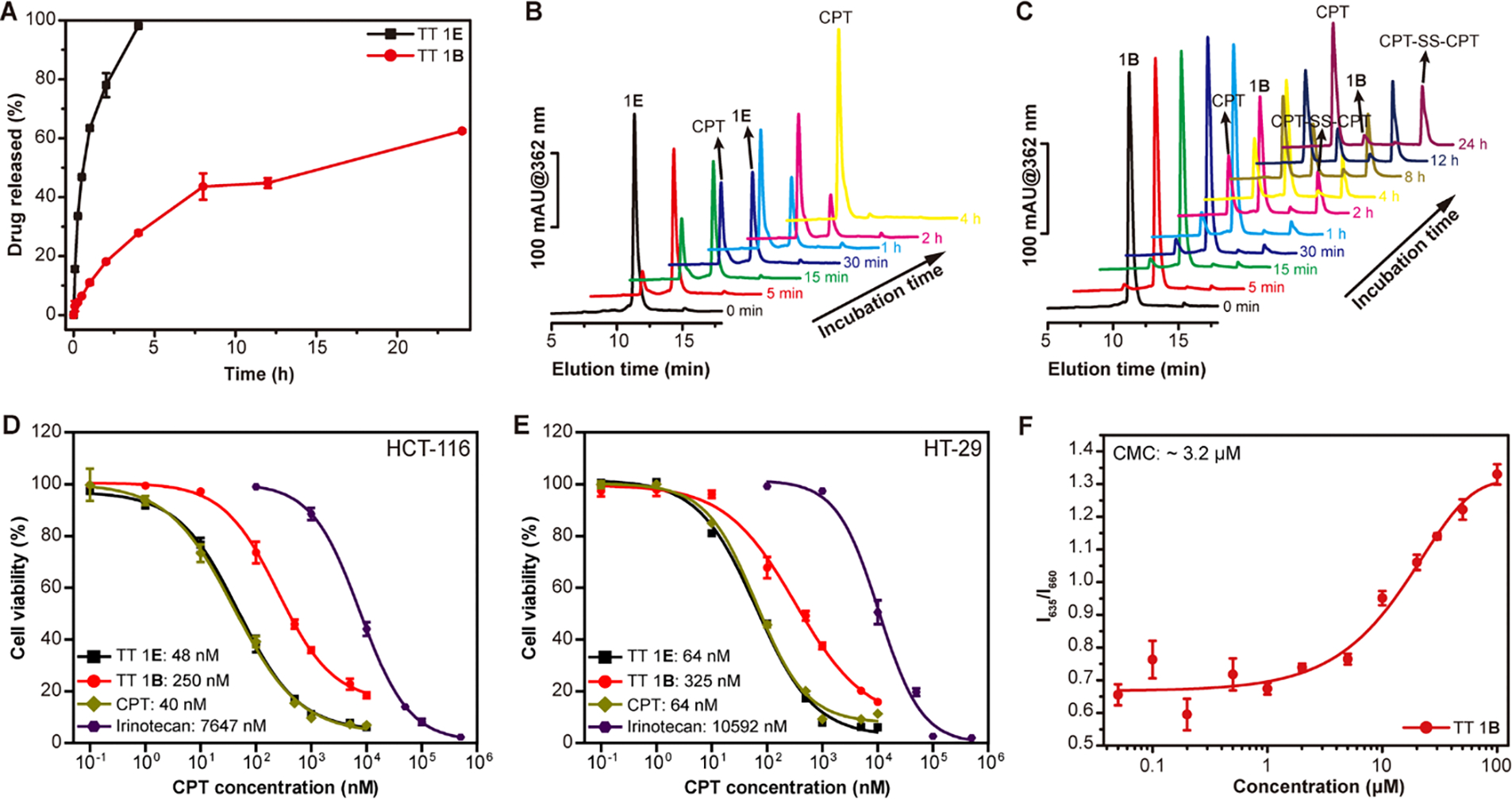

We next studied how the chemical stability of TTs influences their drug release behavior. As expected, we found that the rate of CPT release from TT 1 is highly dependent on the choice of biodegradable linkers. Figure 2A shows the cumulative release of free CPT from TT 1E and TT 1B (200 μM) in the presence of 10 mM glutathione (GSH) in PBS buffer at 37°C. TT 1E exhibited a significantly faster (~24-fold) drug release rate, with 63% and 98% of CPT released at 1 h and 4 h, respectively (Figure 2A). In contrast, TT 1B released only 11%, 28%, and 62% of CPT at 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h, respectively.

Figure 2.

In vitro GSH-induced drug release, cytotoxicity and supramolecular stability of TT 1. (A) Cumulative release plot of the free CPT from TT 1E and TT 1B solutions (200 μM) in PBS containing 10 mM GSH at 37°C (n = 3). Representative HPLC curves of GSH-treated TT 1E (B) and TT 1B (C) solutions at different time points, showing the formation of intermediate species. Comparison of cytotoxicities of TT 1E and TT 1B in inhibiting HCT-116 (D) and HT-29 (E) colon cancer cells after 72 h incubation, respectively. (F) Critical micellization concentration (CMC) study of TT 1B using a Nile Red assay. TT 1B exhibits a CMC of ~3.2 μM, similar to that of TT 1E.

Representative RP-HPLC traces (Figures 2B and 2C) illustrate the degradation profiles of TT 1E and TT 1B at various time points. As shown in Figure 2B, nearly all TT 1E (~11 min elution time) degraded completely into free CPT (~9 min elution time) within 2 h, without forming any intermediate species. However, for TT 1B, additional peaks were observed at ~13.7 min and ~15.6 min (Figure 2C), corresponding to intermediate degradation products: CPT-SH monomer and CPT-SS-CPT dimer (Figure 3A).47 TT 1E, containing the etcSS linker, seems to undergoe self-immolative degradation, rapidly converting into free CPT via a two-step pathway (Figure 3B). In contrast, TT 1B, with a buSS linker, initially breaks down into CPT-SH upon GSH attack. Interestingly, our detailed HPLC release study (Figure 2C) reveals the formation of CPT-S-S-CPT as a key intermediate during the release process, as indicated by the predominance of the dimer peak over the monomer. This suggests that a fraction of CPT-SH may either undergo self-dimerization or participate in disulfide exchange with CPT conjugates. Due to its poor aqueous solubility, CPT-S-S-CPT likely precipitates out of solution, which could, in turn, delay the subsequent hydrolysis necessary for complete release of the parent CPT. We speculate that the locally high concentration of cleaved CPT-SH near the supramolecular nanostructures plays a significant role in promoting and stabilizing the formation of the disulfide dimer, thereby hindering its further conversion into free CPT. These findings demonstrate that the use of an ultra-fast release linker, such as etcSS, significantly accelerates CPT conversion from SPs compared to the slower buSS linker.

Figure 3.

Proposed drug release mechanisms of conjugated designed with different CPT-etcSS and CPT-buSS linkers. (A) Schematic representation of how carbonate-based etcSS and ester-based buSS linkers influence the release of free CPT (3). TT 1E directly degrades into free CPT and the peptide auxiliary, whereas TT 1B undergoes stepwise degradation into CPT-SS-CPT (1), CPT-SH (2), free CPT (3), and the peptide moiety. (B) Prodrugs with the self-immolative etcSS linker rapidly convert into free CPT through an intramolecular degradation pathway. In contrast, those with the buSS linker initially degrade into CPT-SH, which subsequently dimerizes into CPT-SS-CPT. The final release of free CPT requires additional hydrolysis of CPT-SH and CPT-SS-CPT. (C) Illustration of the proposed nanostructure-promoted disulfide dimer formation occurring in close proximity to supramolecular assemblies, which may hinder further conversion into free CPT.

In vitro cytotoxicity against cancer cells.

Since prodrugs generally exhibit much reduced potency, with their anticancer effects primarily dependent on the release of the active drug, we next investigated how chemical stability and subsequent drug release influence their in vitro cytotoxicity. Using HCT-116 and HT-29 colon cancer cell lines, we compared TT 1E and TT 1B with free CPT and irinotecan, a clinically approved CPT prodrug. TT 1E displayed significantly greater inhibitory activity than TT 1B, with IC50 values of 48 nM in HCT-116 and 64 nM in HT-29, compared to 259 nM and 325 nM, respectively, for TT 1B (Figure 2D and 2E). Notably, the potency of TT 1E was even comparable to free CPT (40 nM for HCT-116 and 64 nM for HT-29) and significantly exceeded that of irinotecan. According to our Nile Red assay, TT 1B exhibits a CMC of ~3.2 μM (Figure 2F), comparable to that of TT 1E reported previously,46 indicating high supramolecular stability for both molecules. Given their similar stability, it is likely that TT 1E and TT 1B follow the same cellular uptake mechanism when entering the studied cells. Therefore, these findings highlight the importance of chemical stability to regulate prodrug activation, drug release, and in vitro therapeutic efficacy.

In vivo antitumor efficacies.

Unlike antibody-drug conjugates and polymer-drug conjugates, where the chemical linker is directly exposed to the physiological environment, the linkers in self-assembling peptide-drug conjugates are deeply embedded within the core of the supramolecular nanostructure. This structural arrangement shields them from water and proteases, reducing the likelihood of premature hydrolysis and degradation. As a result, in an in vivo setting, where the physicochemical properties and supramolecular stability often dictate pharmacokinetic profiles, the contribution of chemical stability to overall therapeutic efficacy may be less pronounced than in traditional conjugate systems and may differ from the trends observed in our in vitro studies.

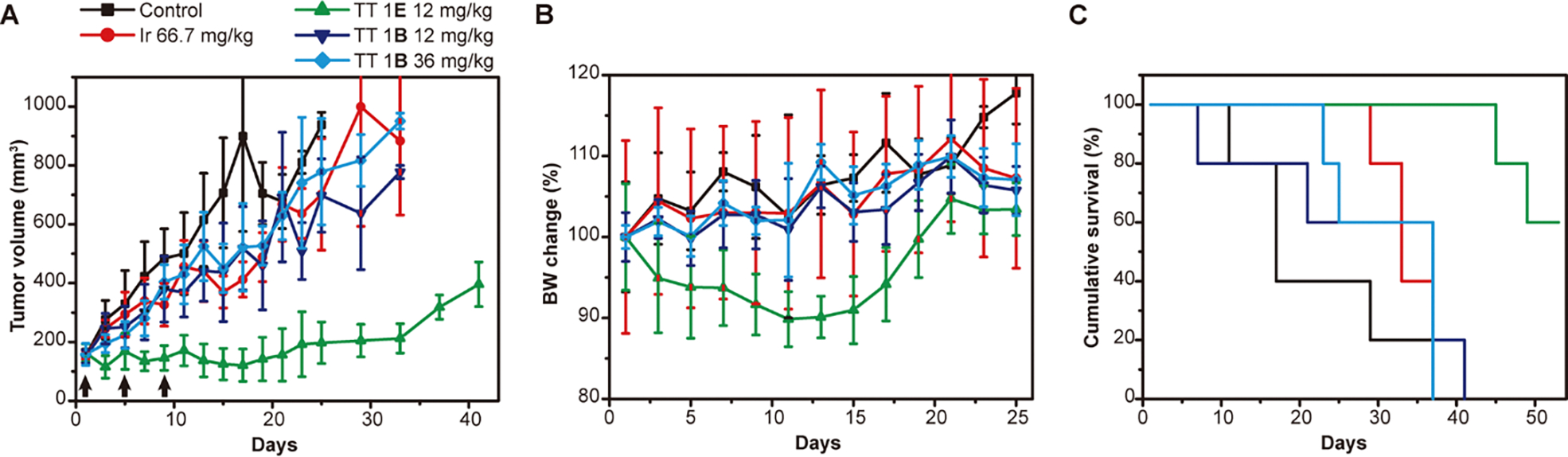

To further understand the impact of chemical stability on the in vivo performance of supramolecular medicines, we evaluated the antitumor efficacy of TT 1E and TT 1B in HT-29 tumor-bearing mice. These prodrugs were administered via intravenous (i.v.) injection on days 1, 5, and 9 at a dose of 12 mg/kg (CPT equivalent) for TT 1E, and at both 12 mg/kg and 36 mg/kg (CPT equivalent) for TT 1B (n = 5 per group), with PBS as a control. Irinotecan, a clinically used CPT prodrug for colorectal cancer, was included as an additional control at a dose of 66.7 mg/kg, near its reported maximum tolerated dose (MTD).48 TT 1E demonstrated significant tumor growth inhibition, with mean tumor volumes of 124 mm3 and 197 mm3 on days 15 and 25, respectively. In contrast, TT 1B at 12 mg/kg, 36 mg/kg, and irinotecan resulted in tumor volumes of 436 mm3, 450 mm3, and 370 mm3 on day 15, and 697 mm3, 779 mm3, and 701 mm3 on day 25, respectively (Figure 4A). While TT 1E treatment caused a slight body weight reduction (<10%), recovery occurred shortly after completing the treatment regimen (Figure 4B). The survival advantage of TT 1E was also notable, with 100% of mice surviving over 41 days and a median survival exceeding 50 days. In comparison, median survival times for PBS, irinotecan, TT 1B (12 mg/kg), and TT 1B (36 mg/kg) groups were 17, 33, 37, and 37 days, respectively (Figure 4C). These results highlight that TT 1E outperformed TT 1B even when the latter was administered at higher doses, as well as irinotecan. Given that TT 1E and TT 1B differ only in linker chemistry while maintaining similar supramolecular stability, our findings strongly suggest that, under comparable supramolecular conditions, lower chemical stability still contributes to enhanced in vivo therapeutic efficacy in supramolecular polymer-based drug delivery systems.

Figure 4.

Comparison of in vivo antitumor efficacy of TT 1E and TT 1B in nude mice bearing HT-29 tumors. Mice were intravenously injected with PBS (control), irinotecan (66.7 mg/kg), TT 1E (12 mg/kg, CPT equivalent), or TT 1B (12 and 36 mg/kg, CPT equivalent) on days 1, 5, and 9 (black arrows) (n = 5 per group). Tumor volume (A), body weight (B), and cumulative survival (C) were monitored and plotted.

Molecular design of shorter tubustecans

To further explore the relationship between chemical stability, supramolecuar stability, and their therapeutic efficay, we synthesized a series of OEGylated prodrugs, SAPD 2–4 (Scheme 1, Figure S1–S5), incorporating either etcSS or buSS linkers, and assessed their potency against cancer cells. Consistently, SAPDs with the faster-releasing etcSS linker (2E–4E) always exhibited lower IC50 values than their buSS counterparts (2B–4B), reinforcing the correlation between reduced chemical stability and higher drug potency (Table S1). However, we found that simply increasing the peptide length to introduce additional OEG segments, while allowing for modulation of supramolecular stability, resulted in the loss of tubular morphology and the formation of amyloid-like filaments instead.46 This morphological shift was driven by a combination of increased hydrophilic–lipophilic balance (HLB) values, steric repulsion from the additional OEG segments, and a transition in the assembly mode from π–π stacking-driven interactions to hydrogen bonding-dominated self-assembly due to the higher number of amide groups in the peptides.46 To preserve the ordered tubular packing, the ordered tubular packing, we increased the number of CPT units from two to four, enhancing π–π stacking among the CPT units.

Scheme 1.

Summary of synthesized OEGylated self-assembling prodrugs

Figure 5A shows the chemical structure of TT 7, which incorporates four CPTs and a peptide backbone with eight OEG side chains. To investigate the role of linker chemistry, we designed two variants: TT 7E and TT 7B, incorporating etcSS and buSS linkers, respectively (Figure 5A, 5B and S7). Upon dissolving in aqueous solution at 1 mM concentration, cryo-TEM (Figure 5C) and conventional TEM (Figure S8) imaging revealed that TT 7E self-assembles into short tubular structures with an average length of 51 nm (n > 100) and a diameter of 9.3 nm (n > 50), similar to TT 7B, which exhibited an average length of 54 nm (n > 100) and a diameter of 9.2 nm (n > 50) (Figure 5D). The high density of OEG appears to limit further elongation of SPs, while the strong π–π stacking from four CPT units preserves the tubular core.49 These findings demonstrate how supramolecular engineering of molecular building blocks enables fine-tuning of key physiochemical properties, such as length and stability, of SPs. Notably, the formation of such short nanotubes with significantly lower aspect ratios compared to TT 1 suggests that their size and geometry may lead to distinct cellular uptake and tumor accumulation behaviors, potentially impacting their therapeutic efficacy.50–54

Figure 5.

Design and self-assembly of OEGylated TT 7. (A) Chemical structure and cartoon illustration of TT 7. (B) Schematic illustration of self-assembly of TT 7 into short tubular supramolecular polymers. Representative cryo-TEM images of assembled TT 7E (C) and TT 7B (D) at the concentration of 1 mM. Short tubular supramolecular polymers were formed with average length around 50 nm (n > 100) and diameter around 9 nm (n > 50) for both TT 7E and 7B.

In vitro cytotoxicity studies of TT 7.

To evaluate the impact of linker chemistry on cytotoxicity, we compared the in vitro anticancer activities of TT 7E and its buSS-linked counterpart, TT 7B, across three different cancer cell lines: HT-29 colon cancer cells (Figure 6A), A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells (Figure 6B), and HepG2 liver cancer cells (Figure 6C). As expected, TT 7E exhibited significantly greater cytotoxicity than TT 7B, with IC50 values at least 20-fold lower in all three cell lines, reinforcing the critical role of linker chemistry in drug activation and therapeutic efficacy. Interestingly, we observed that TT 7E released its drug payload more slowly than TT 1E (Figure S7D vs. Figure 2A). This difference is likely due to the increased number of CPT units in TT 7E, which strengthens π–π stacking interactions and enhances supramolecular stability, thereby impeding drug release. However, despite its higher supramolecular stability, TT 7E still exhibited a faster release profile than TT 1B, with 70% and 99% of free CPT released at 8 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to only 44% and 62% for TT 1B (Figure 2A). These findings further emphasize the dominant influence of chemical stability on drug release kinetics and cytotoxicity, highlighting its critical role in optimizing the therapeutic potential of TTs.

Figure 6.

In vitro and in vivo study of TT 7. Comparison of cell cytotoxicities of TT 7E and TT 7B against HT-29 colon cancer cells (A), A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells (B), and HepG2 liver cancer cells (C) with free CPT as control (n ≥ 3, 72 h incubation). Antitumor efficacy study of TT 7E in nude mice bearing HT-29 tumors (D – F) and HCT-116 tumors (G – I). TT 7E (10 mg/kg, CPT equivalent, n = 7 for HT-29 and n = 5 for HCT-116) was i.v. injected on days 1, 5 and 9 with blank PBS (n = 8 for HT-29 and n = 5 for HCT-116) and irinotecan (66.7 mg/kg, n = 7 for HT-29 and n = 5 for HCT-116) as controls. Tumor volume (D and G), body weight (E and H) and cumulative survival (F and I) plots of mice. Loss of mice is a result of treatment-related death or killing after predetermined end point was reached.

TT 7E outperformed irinotecan in vivo.

Since TT 7B exhibited extremely low potency against cancer cells (Figure 5A–C), we proceeded to evaluate only the in vivo performance of TT 7E. First, we determined the MTD of TT 7E through a dose-escalation study in healthy mice, defining it as the highest administered dose that did not result in more than a 20% body weight loss or mortality. The MTD for TT 7E was found to be approximately 15 mg/kg (CPT equivalent) (Table S2). We then assessed its antitumor efficacy in an HT-29 colon tumor model, administering intravenous (i.v.) injections at a dose of 10 mg/kg (n = 7, CPT equivalent) on days 1, 5, and 9, with PBS (n = 8) and irinotecan (66.7 mg/kg, MTD, n = 7) serving as controls (Figure 6D–F). TT 7E induced significant tumor regression compared to both control and irinotecan-treated groups. On day 17, the mean tumor volume in the TT 7E group was 65 mm3, significantly lower than 562 mm3 in the PBS group and 429 mm3 in the irinotecan group (Figure 6D). Tumor growth remained suppressed, with mean volumes staying below 150 mm3 until day 37, suggesting prolonged therapeutic effects. Additionally, TT 7E markedly improved survival outcomes, extending median survival to 69 days compared to 29 days for PBS and 41 days for irinotecan (Figure 6F). We further evaluated TT 7E in another colon tumor model (HCT-116) (Figure 6G–I and Figure S9), where it again outperformed irinotecan, achieving the lowest mean tumor volume of 111 mm3 on day 17, compared to 336 mm3 for irinotecan (Figure 6G). Notably, 100% of mice in the TT 7E-treated group survived beyond 41 days, while those treated with irinotecan had a median survival of only 23 days (Figure 6I). These findings highlight the potential of supramolecular OEGylation in designing well-defined SPs with controlled lengths for systemic CPT delivery. The combination of high supramolecular stability and low chemical stability in TT 7E enhances its therapeutic effectiveness, making it a superior candidate compared to irinotecan

Based on our studies, TT 7E emerges as the most promising candidate within our TT platform for systemic drug delivery in our tested animal models, significantly outperforming irinotecan in both colon tumor models. Moreover, it demonstrated superior tumor suppression in the HT-29 model compared to the previously identified best candidate, TT 1E, despite exhibiting slower drug release due to its higher supramolecular stability (Figure 4 and 6D–F). Our previous studies have shown that increased supramolecular stability correlates with both enhanced efficacy and stronger toxicity,46 a trend that remains consistent here, as TT 7E exhibited greater efficacy but also higher toxicity (MTD: 15 mg/kg for TT 7E vs. 24 mg/kg for TT 1E). More importantly, leveraging the advantages of our TT platform, we systematically investigated the role of chemical stability in influencing drug release, in vitro potency, and in vivo efficacy. Our results consistently demonstrated that while high supramolecular stability is essential for maintaining nanostructure integrity in circulation to prevent premature drug clearance or degradation, lower chemical stability is crucial for effective drug activation at the disease site. Together with our previous findings, this study reinforces the principle that optimal supramolecular drug assemblies require a balance between supramolecular and chemical stability—ensuring structural integrity during circulation while enabling efficient degradation and release in response to biological stimuli at target sites.

CONCLUSION

In this work, we introduced supramolecular OEGylation as an effective strategy to expand our tubustecan SP platform for systemic drug delivery. We synthesized a series of OEGylated prodrugs were synthesized, and highlighted two representative candidates, TT 1E and TT 7E for their ability to self-assemble in water into long and short tubular supramolecular polymers. By modifying the linker chemistry in OEGylated TTs, we systematically explored the impact of chemical stability on SPs' in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy. We found that lower chemical stability correlated with greater tumor suppression, reinforcing the importance of degradability in therapeutic performance. Building on our findings in supramolecular stability, we hypothesize that SPs with high supramolecular stability and low chemical stability represent a promising direction for supramolecular medicine. The ideal SPs should remain stable in circulation through strong physical interactions while undergoing targeted destabilization via chemical degradation at the disease site. By elucidating key supramolecular design principles for drug-based building blocks, we hope this work contributes to a deeper understanding of supramolecular medicines and their potential for systemic drug delivery.

Supplementary Material

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

This file contains materials, methods, chemical synthesis, and characterization of self-assembling prodrugs with supplementary figures (Figures. S1 to S9) and tables (Tables S1 and S2). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the Johns Hopkins University Integrated Imaging Center for TEM and the Department of Chemistry for Mass Spectrometry.

Funding Sources

The work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (5R01CA284268).

ABBREVIATIONS

- SP

supramolecular polymers

- PEG

poly (ethylene glycol)

- TT

tubustecan

- OEG

oligo (ethylene glycol)

- CPT

Camptothecin

- etcSS

disulfanyl-ethyl carbonate

- buSS

disulfanyl butyrate

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- CD

circular dichroism

REFERENCES

- 1.Aida T; Meijer EW; Stupp SI, Functional Supramolecular Polymers. Science 2012, 335 (6070), 813–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webber MJ; Appel EA; Meijer EW; Langer R, Supramolecular biomaterials. Nat Mater 2016, 15 (1), 13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acar H; Srivastava S; Chung EJ; Schnorenberg MR; Barrett JC; LaBelle JL; Tirrell M, Self-assembling peptide-based building blocks in medical applications. Adv Drug Deliver Rev 2017, 110, 65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H; Su H; Xu T; Cui HG, Utilizing the Hofmeister Effect to Induce Hydrogelation of Nonionic Supramolecular Polymers into a Therapeutic Depot. Angew Chem Int Edit 2023, 62 (43), e202306652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H; Mills J; Sun B; Cui H, Therapeutic supramolecular polymers: Designs and applications. Prog Polym Sci 2024, 148, 101769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto NM; Lafleur RPM; Lou XW; Shih KC; Wijnands SPW; Guibert C; van Rosendaal JWAM; Voets IK; Palmans ARA; Lin Y; Meijer EW, Polymorphism in Benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide Supramolecular Assemblies in Water: A Subtle Trade-off between Structure and Dynamics. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140 (41), 13308–13316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X; Li MM; Liu JZ; Song YQ; Hu BB; Wu CX; Liu AA; Zhou H; Long JF; Shi LQ; Yu ZL, Self-Sorting Peptide Assemblies in Living Cells for Simultaneous Organelle Targeting. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144 (21), 9312–9323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su L; Mosquera J; Mabesoone MFJ; Schoenmakers SMC; Muller C; Vleugels MEJ; Dhiman S; Wijker S; Palmans ARA; Meijer EW, Dilution-induced gel-sol-gel-sol transitions by competitive supramolecular pathways in water. Science 2022, 377 (6602), 213–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frederix PWJM; Scott GG; Abul-Haija YM; Kalafatovic D; Pappas CG; Javid N; Hunt NT; Ulijn RV; Tuttle T, Exploring the sequence space for (tri-) peptide self-assembly to design and discover. Nat Chem 2015, 7 (1), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas CG; Shafi R; Sasselli IR; Siccardi H; Wang T; Narang V; Abzalimov R; Wijerathne N; Ulijn RV, Dynamic peptide libraries for the discovery of supramolecular nanomaterials. Nat Nanotechnol 2016, 11 (11), 960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu LT; Kreutzberger MAB; Bui TH; Hancu MC; Farsheed AC; Egelman EH; Hartgerink JD, Exploration of the hierarchical assembly space of collagen-like peptides beyond the triple helix. Nat Commun 2024, 15 (1), Article Number 10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui HG; Cheetham AG; Pashuck ET; Stupp SI, Amino Acid Sequence in Constitutionally Isomeric Tetrapeptide Amphiphiles Dictates Architecture of One-Dimensional Nanostructures. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136 (35), 12461–12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampel A; McPhee SA; Park HA; Scott GG; Humagain S; Hekstra DR; Yoo B; Frederix PWJM; Li TD; Abzalimov RR; Greenbaum SG; Tuttle T; Hu CH; Bettinger CJ; Ulijn RV, Polymeric peptide pigments with sequence-encoded properties. Science 2017, 356 (6342), 1064–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang YW; Zhou TL; Qi YZ; Li YJ; Zhang YJ; Zhao YX; Han HJ; Wang Y, Engineered assemblies from isomeric pentapeptides augment dry eye treatment. J Control Release 2024, 365, 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan SC; Lewis JA; Sai H; Weigand SJ; Palmer LC; Stupp SI, Peptide Sequence Determines Structural Sensitivity to Supramolecular Polymerization Pathways and Bioactivity. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144 (36), 16512–16523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y; Kaur K; Scannelli SJ; Bitton R; Matson JB, Self-Assembled Nanostructures Regulate H2S Release from Constitutionally Isomeric Peptides. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140 (44), 14945–14951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao J; Zhan J; Yang ZM, Enzyme-Instructed Self-Assembly (EISA) and Hydrogelation of Peptides. Adv Mater 2020, 32 (3), 1805798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo JQ; Zia A; Qiu QF; Norton M; Qiu KQ; Usuba J; Liu ZY; Yi MH; Rich-New ST; Hagan M; Fraden S; Han GD; Diao JJ; Wang FB; Xu B, Cell-Free Nonequilibrium Assembly for Hierarchical Protein/Peptide Nanopillars. J Am Chem Soc 2024, 146 (38), 26102–26112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu ZY; Guo JQ; Qiao YC; Xu B, Enzyme-Instructed Intracellular Peptide Assemblies. Accounts Chem Res 2023, 56 (21), 3076–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu YM; Archer WR; Morales KF; Schulz MD; Wang Y; Matson JB, Enzyme-Triggered Chemodynamic Therapy via a Peptide-H2S Donor Conjugate with Complexed Fe2+. Angew Chem Int Edit 2023, 62 (22), e202302303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakroun RW; Sneider A; Anderson CF; Wang F; Wu PH; Wirtz D; Cui H, Supramolecular design of unsymmetric reverse bolaamphiphiles for cell‐sensitive hydrogel degradation and drug release. Angewandte Chemie 2020, 132 (11), 4464–4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S; Zhang QX; He HJ; Yi MH; Tan WY; Guo JQ; Xu B, Intranuclear Nanoribbons for Selective Killing of Osteosarcoma Cells. Angew Chem Int Edit 2022, 61 (44). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendrikse SIS; Su L; Hogervorst TP; Lafleur RPM; Lou XW; van der Marel GA; Codee JDC; Meijer EW, Elucidating the Ordering in Self-Assembled Glycocalyx Mimicking Supramolecular Copolymers in Water. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (35), 13877–13886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu RM; Sasselli IR; Alvarez Z; Sai H; Ji W; Palmer LC; Stupp SI, Supramolecular Copolymers of Peptides and Lipidated Peptides and Their Therapeutic Potential. J Am Chem Soc 2022, 144 (12), 5562–5574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su H; Zhang WJ; Wang H; Wang FH; Cui HG, Paclitaxel-Promoted Supramolecular Polymerization of Peptide Conjugates. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (30), 11997–12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheetham AG; Chakroun RW; Ma W; Cui HG, Self-assembling prodrugs. Chem Soc Rev 2017, 46 (21), 6638–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su H; Koo JM; Cui HG, One-component nanomedicine. J Control Release 2015, 219, 383–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiapparelli P; Zhang P; Lara-Velazquez M; Guerrero-Cazares H; Lin R; Su H; Chakroun RW; Tusa M; Quiñones-Hinojosa A; Cui H, Self-assembling and self-formulating prodrug hydrogelator extends survival in a glioblastoma resection and recurrence model. J Control Release 2020, 319, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabral H; Kinoh H; Kataoka K, Tumor-Targeted Nanomedicine for Immunotherapy. Accounts Chem Res 2020, 53 (12), 2765–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Guyse JFR; Abbasi S; Toh K; Nagorna Z; Li JJ; Dirisala A; Quader S; Uchida S; Kataoka K, Facile Generation of Heterotelechelic Poly(2-Oxazoline)s Towards Accelerated Exploration of Poly(2-Oxazoline)-Based Nanomedicine. Angew Chem Int Edit 2024, 63 (27), e202404972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharyya J; Bellucci JJ; Weitzhandler I; McDaniel JR; Spasojevic I; Li XH; Lin CC; Chi JTA; Chilkoti A, A paclitaxel-loaded recombinant polypeptide nanoparticle outperforms Abraxane in multiple murine cancer models. Nat Commun 2015, 6, Article number: 7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banskota S; Saha S; Bhattacharya J; Kirmani N; Yousefpour P; Dzuricky M; Zakharov N; Li XH; Spasojevic I; Young K; Chilkoti A, Genetically Encoded Stealth Nanoparticles of a Zwitterionic Polypeptide-Paclitaxel Conjugate Have a Wider Therapeutic Window than Abraxane in Multiple Tumor Models. Nano Lett 2020, 20 (4), 2396–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheetham AG; Zhang PC; Lin YA; Lock LL; Cui HG, Supramolecular Nanostructures Formed by Anticancer Drug Assembly. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135 (8), 2907–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu XA; Wang H; Liu X; Huang L; Song N; Song YQ; Mo XW; Lou SF; Shi LQ; Yu ZL, Assembling synergistic peptide-drug conjugates for dual-targeted treatment of cancer metastasis. Nano Today 2022, 46, 101594. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y; Cheetham AG; Angacian G; Su H; Xie LS; Cui HG, Peptide-drug conjugates as effective prodrug strategies for targeted delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev 2017, 110, 112–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H; Monroe MK; Wang F; Sun M; Flexner C; Cui H, Constructing Antiretroviral Supramolecular Polymers as Long-Acting Injectables through Rational Design of Drug Amphiphiles with Alternating Antiretroviral-Based and Hydrophobic Residues. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145 (39), 21293–21302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo JQ; Tan WY; He HJ; Xu B, Autohydrolysis of Diglycine-Activated Succinic Esters Boosts Cellular Uptake. Angew Chem Int Edit 2023, 62 (36), e202308022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sis MJ; Ye Z; La Costa K; Webber MJ, Energy Landscapes of Supramolecular Peptide-Drug Conjugates Directed by Linker Selection and Drug Topology. Acs Nano 2022, 16 (6), 9546–9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su H; Wang FH; Wang YZ; Cheetham AG; Cui HG, Macrocyclization of a Class of Camptothecin Analogues into Tubular Supramolecular Polymers. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (43), 17107–17111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang FH; Su H; Lin R; Chakroun RW; Monroe MK; Wang ZY; Porter M; Cui HG, Supramolecular Tubustecan Hydrogel as Chemotherapeutic Carrier to Improve Tumor Penetration and Local Treatment Efficacy. Acs Nano 2020, 14 (8), 10083–10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang FH; Su H; Xu DQ; Dai WB; Zhang WJ; Wang ZY; Anderson CF; Zheng MZ; Oh R; Wan FY; Cui HG, Tumour sensitization via the extended intratumoural release of a STING agonist and camptothecin from a self-assembled hydrogel. Nat Biomed Eng 2020, 4 (11), 1090–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanco E; Shen H; Ferrari M, Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33 (9), 941–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webber MJ; Appel EA; Vinciguerra B; Cortinas AB; Thapa LS; Jhunjhunwala S; Isaacs L; Langer R; Anderson DG, Supramolecular PEGylation of biopharmaceuticals. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2016, 113 (50), 14189–14194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li WJ; Zhan P; De Clercq E; Lou HX; Liu XY, Current drug research on PEGylation with small molecular agents. Prog Polym Sci 2013, 38 (3–4), 421–444. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pommier Y, Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2006, 6 (10), 789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su H; Wang FH; Ran W; Zhang WJ; Dai WB; Wang H; Anderson CF; Wang ZY; Zheng C; Zhang PC; Li YP; Cui HG, The role of critical micellization concentration in efficacy and toxicity of supramolecular polymers. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117 (9), 4518–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheetham AG; Ou YC; Zhang PC; Cui HG, Linker-determined drug release mechanism of free camptothecin from self-assembling drug amphiphiles. Chem Commun 2014, 50 (45), 6039–6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koizumi F; Kitagawa M; Negishi T; Onda T; Matsumoto S; Hamaguchi T; Matsumura Y, Novel SN-38-incorporating polymeric micelles, NK012, eradicate vascular endothelial growth factor-secreting bulky tumors. Cancer Res 2006, 66 (20), 10048–10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su H; Wang FH; Wang H; Zhang WJ; Anderson CF; Cui HG, Propagation-Instigated Self-Limiting Polymerization of Multiarmed Amphiphiles into Finite Supramolecular Polymers. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143 (44), 18446–18453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gratton SEA; Ropp PA; Pohlhaus PD; Luft JC; Madden VJ; Napier ME; DeSimone JM, The effect of particle design on cellular internalization pathways. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105 (33), 11613–11618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Champion JA; Mitragotri S, Role of target geometry in phagocytosis. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103 (13), 4930–4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chithrani BD; Ghazani AA; Chan WCW, Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells. Nano Lett 2006, 6 (4), 662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenblum D; Joshi N; Tao W; Karp JM; Peer D, Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat Commun 2018, 9, Article number: 1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geng Y; Dalhaimer P; Cai SS; Tsai R; Tewari M; Minko T; Discher DE, Shape effects of filaments versus spherical particles in flow and drug delivery. Nat Nanotechnol 2007, 2 (4), 249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.