Abstract

Background acacia melanoxylon

is an important species for establishing pulpwood plantations due to its high application value in engineered wood products. However, the lack of a well-established in vitro regeneration system has severely constrained its industrial-scale propagation and the induction of tetraploids.

Results

In this study, using the superior A. melanoxylon clone SR3, an in vitro regeneration system using a bud-bearing stem segment was established. A DKW medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/L 6-BA, 0.1 mg/L IAA, and 0.2 mg/L NAA was determined as the optimal differentiation medium. Adding 0.5 mg/L IBA and 0.25 mg/L NAA to the 1/2 MS medium produced a higher rooting percentage and root number. To determine the optimal timing for tetraploid induction in A. melanoxylon, morphological, cytological, and flow cytometric analyses were conducted on the swollen tissue at the base of the bud-bearing stem segment. On the 5th day of preculture, white callus tissue was observed, characterized by vigorous cell division and the highest G2/M-phase cell content in the adventitious bud primordia. After colchicine treatment, the tetraploid induction efficiency on the 5th day of preculture was significantly higher compared to the 4th or 6th day. The highest induction rate of 12.26 ± 0.80% was achieved with 100 mg/L colchicine for 72 h on the 5th day of preculture. Furthermore, tetraploid A. melanoxylon exhibited morphological traits such as reduced plant height, leaf number, and stomatal density.

Conclusions

This study establishes a stable and effective method for in vitro tetraploid induction in A. melanoxylon, providing theoretical and technical support for polyploid breeding and laying the groundwork for subsequent triploid development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13007-025-01426-0.

Keywords: Acacia tree, Bud-bearing stem segment, Adventitious bud, Developmental stage observation, Tetraploid induction, Morphological variation

Background

A. melanoxylon is an evergreen, fast-growing tree species of the genus Acacia in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the Fabaceae family. Due to its rapid growth, high pulp yield [1, 2], hard wood [3], high fiber quality [4], and ability to grow in relatively poor soils [5], it has become an important timber raw material for forest construction. However, the genetic improvement of A. melanoxylon remains largely confined to traditional selection, which is insufficient to meet the increasing demand for elite varieties in industrial timber plantations [6, 7]. Polyploid breeding, especially triploid breeding, holds significant potential for developing new tree species and selecting fast-growing, high-yield forest varieties with short rotation periods and high productivity [8]. Compared to diploids, triploid trees exhibit significantly enhanced growth rate, and photosynthetic efficiency [8, 9], increased levels of secondary metabolites [10], and better physiological adaptability under environmental stresses [11]. These advantages make triploid breeding a promising strategy for developing cultivars with rapid growth, increased secondary metabolite production, and improved stress tolerance [12, 13]. However, tetraploid trees often demonstrate weaker growth traits than diploids [14–17]. Nevertheless, the acquisition of tetraploids can provide materials for the hybridization of diploids and tetraploids to obtain triploids [18]. To date, no studies have reported the induction of triploids or tetraploids in A. melanoxylon.

The methods for artificially inducing tetraploids include treating germinating seeds [19–21], seedling apical buds [22], in vitro leaves [23, 24], bud-bearing stem segment [25], callus tissue [26, 27] and zygotes [28] with colchicine solutions. Seed and seedling apical bud treatments often result in mixoploids due to the multicellular nature of these materials. While in vitro differentiation and purification can resolve this issue of mixoploids [29], the process requires multiple steps, including regeneration system establishment, tissue culture purification, and ploidy identification, making it difficult and inefficient than the direct chromosome doubling of adventitious buds in vitro [30]. The regeneration of the in vitro receptor materials, such as plant leaves and stem segments, typically begins with the dedifferentiation and cell division of the parenchyma cells at or near the incision sites and the vascular bundle sheath cells [31]. During the direct induction of adventitious buds from these tissues, chromosome doubling can occur in the first mitotic division of the bud primordium cells, resulting in the formation of homozygous tetraploids [32]. In poplar, treating in vitro leaves with 30 mg/L colchicine for 3 days during differentiation culture induced chromosome doubling in adventitious buds, with tetraploid induction rates ranging from 7.9 to 13.2% across different genotypes and no chimeras being observed [24].

In the establishment of plant tissue culture systems, the types and ratios of plant growth regulators (PGRs) are among the key factors affecting explant dedifferentiation, organogenesis, and regeneration efficiency [33]. By adjusting the concentrations of auxins and cytokinins, both the direction and type of organogenesis can be modulated [34]. For instance, the combination of 6-BA and NAA has been shown to play a crucial role in the direct induction of adventitious buds in poplar [35] and apple [36], typically using ratios of approximately 5:1 to 10:1 [34]. In addition, studies have shown that substituting or adding other auxins (such as IAA and IBA) on this basis can further enhance the regeneration efficiency of adventitious buds [37, 38]. Stem segments can effectively induce adventitious bud regeneration via callus-mediated pathways when cultured with combinations of 6-BA (0.1–2.0 mg/L) and either NAA (0.2–0.5 mg/L) or IAA (0.2–1.0 mg/L) in A. melanoxylon [39, 40]. In plant rooting culture systems, the combination of IBA and NAA added to 1/2 MS medium is commonly used as a primary set of growth regulators [34]. For example, in poplar, treatment with IBA alone results in low rooting efficiency, while its combination with NAA significantly increases adventitious root induction rates [41]. In A. melanoxylon, different genotypes can form roots either with IBA alone (0.25–2.0 mg/L) or in combination with NAA (0.2–0.5 mg/L) [39, 40]. However, current studies on A. melanoxylon have only reported callus-mediated adventitious bud regeneration, which is generally inefficient and time-consuming [39, 40]. A direct regeneration system has yet to be established. Furthermore, systematic hormone optimization for both direct adventitious bud induction and rooting remains lacking, thereby constraining its clonal propagation and polyploid breeding potential.

In this study, a regeneration system was established based on bud-bearing stem segment using an elite clone SR3 of A. melanoxylon as the experimental material. Since adventitious buds can be induced from bud-bearing stem segments in A. melanoxylon, the question arises: can this pathway also be used to induce tetraploids? To explore this, we first investigated the developmental status and cell cycle progression of explant tissues during adventitious bud regeneration. On this basis, we successfully induced chromosome doubling in the in vitro–derived adventitious buds and developed a stable and efficient method for somatic chromosome doubling, and tetraploid plants were successfully obtained. Subsequent phenotypic characterization revealed that tetraploid A. melanoxylon exhibited clear growth disadvantages compared to diploids, with significantly reduced plant height, leaf number, and stomatal density. This study provides foundational materials and technical references for the creation of novel A. melanoxylon germplasm and the cultivation of triploids.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and culture initiation

Plant materials

The superior clone SR3 of A. melanoxylon, which had been originally selected and bred by the Research Institute of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Guangdong Province, China, was used as the plant material in this study. One-year-old root sucker seedlings of the superior tree were collected and planted in the greenhouse of Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China (39.98°N, 116.34°E). The greenhouse was maintained at 24–28 °C, and the seedlings were allowed to grow for at least one month before use.

Explant disinfection and culture initiation

Fresh stem segments with axillary buds were collected, washed under running tap water for more than 60 min with the tap turned on to a very small flow, maintaining a thin and continuous stream of water to gently rinse the surface of the samples, and then treated with 75% ethanol for 45 s in a sterile laminar flow hood. The axillary buds were then immersed in an ‘84’ disinfectant solution for 20 min, followed by three washes with sterile distilled water, each for more than 5 min. Subsequently, the axillary buds were inoculated onto the Murashige and Skoog (MS, Caisson Labs, MSP09) basic medium supplemented with 30 g/L sucrose and 7 g/L agar.

Culture conditions

The pH of all media in this study was adjusted to 5.8–6.0 with 1 M NaOH and measured using a pH meter (Sartorius PB-10, Germany). After the pH adjustment, 7 g/L agar was added to the medium, and the mixture was autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. Approximately 25 mL of sterilized medium was poured into each 280 mL glass bottle, and all plant growth regulators were filter-sterilized (0.22 μm) before addition. All in vitro culture experiments were conducted at 25 ± 2 °C under LED lighting (2000–3000 lx) with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod.

Establishment of adventitious bud regeneration system for bud-bearing stem segments

The bud-bearing stem segment were derived from axillary bud-proliferated shoots of A. melanoxylon were used as the material. The segments were inoculated onto a Driver and Kuniyuki Walnut (DKW) basal medium(composition for 1 L provided in Supplementary Table S1)using the straight insertion method. A three-factor, three-level orthogonal experimental design was used, using DKW medium supplemented with 6-Benzylaminopurine (6-BA) (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mg/L), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (0.05, 0.1, and 0.15 mg/L), and 1-naphthylacetic acid (NAA) (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 mg/L) as the differentiation medium. Each treatment consisted of three replicates, with 50 stem segments per replicate. Adventitious bud regeneration was recorded after 40 days of culture.

Effects of different concentrations of NAA on rooting culture

Using 1/2 MS basic medium with 0.5 mg/L 3-indolebutyric acid (IBA) as the basal medium, single adventitious buds larger than 1.5 cm in height were excised from bud-bearing stem segments after induction on differentiation medium and treated with different concentrations of NAA (0, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/L). Each treatment was repeated thrice, with 50 stem segments per repeat. The rooting was assessed after 30 days by calculating the rooting percentage and number of roots.

Anatomical analysis of the adventitious bud regeneration

To observe the process of adventitious bud regeneration, swollen tissues formed on bud-bearing stem segments during adventitious bud induction on differentiation-inducing medium were collected at various developmental stages and fixed in FAA fixative (5 mL of 38% formaldehyde, 5 mL of glacial acetic acid, and 90 mL of 70% ethanol) for 24 h. The samples were dehydrated using a graded ethanol series, followed by paraffin infiltration and embedding. Transverse sections of 4 μm thickness were prepared using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2016, Leica) and stained with Safranin-Fast Green. The stained sections were digitally scanned using an automatic slide scanner (Panoramic MIDI, 3DHISTECH).

Characterization and cytological observation of receptor material

Bud-bearing stem segments of A. melanoxylon were cultured on differentiation-inducing medium, and the base of each segment was observed under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX12) at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 days to examine callus formation at the incision site. Photographs were taken to record document morphological changes during early differentiation.

Samples were taken from the A. melanoxylon receptor material cultured on differentiation medium at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6d. The expanding portion of the bud-bearing stem segment was excised and fixed with FAA fixative for 24 h. Subsequent procedures followed the same protocol as described above.

Colchicine-induced chromosome doubling treatment

Bud-bearing stem segments of A. melanoxylon that exhibited both uniformity and vigorous growth were selected for adventitious bud induction and transferred to differentiation medium. After preculturing for 4, 5, or 6 days, the segments were transferred to a liquid regeneration medium containing colchicine at concentrations of 60, 80, or 100 mg/L for 24, 48, or 72 h, respectively. After three washes with sterile water, each for more than 5 min, the segments were transferred to a colchicine-free solid regeneration medium for 40 days to induce adventitious bud formation. In total, 27 treatments were tested, with each treatment repeated thrice, using 10 stem segments per replicate. When the adventitious buds attained a length of 1.5 cm, the regenerated A. melanoxylon plants were transferred to the rooting medium.

Flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle and the DNA content of the regenerating buds

Flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, USA) was used to analyze the cell cycle [42, 43]. Approximately 0.5 g of basal tissues from bud-bearing stem segments that had been precultured on differentiation medium for 0 to 6 days were placed in a culture dish containing 1 mL to 2 mL of nuclear lysis solution (45 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 30 mM sodium citrate, 20 mM MOPS, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 7.0). The mixture was filtered through a 30 μm nylon mesh into a sample tube. The nuclei were stained with 60 µL to 70 µL of DAPI (5 mg/mL) for 1 min. Three samples were collected for each treatment. The peak patterns were analyzed using a Cyflow® cytometer (Partec PAS, Germany), and the ModFit LT 5.0 software was used to identify the proportions of cells in the G1, S, and G2/M phases [42].

After colchicine treatment, regenerated adventitious buds were subjected to 30 days of rooting culture, and the DNA content of sterile A. melanoxylon seedlings was then analyzed by flow cytometry. The tender leaves were placed in a culture dish with 1 mL to 2 mL of nuclear lysis solution and quickly chopped using a sharp double-edged blade. The mixture was filtered through a 30 μm nylon mesh, and the collected filtrate was mixed with 60 µL to 70 µL of DAPI (5 mg/ml) stain and incubated for 1 min. Flow cytometry was used to measure the DNA content. To determine the DNA content of the diploid cells, young diploid leaves were used as a reference to adjust the flow cytometry peak. Subsequently, ploidy identification was performed on the rooting seedlings. Ploidy was reassessed after 90 days to confirm the plants’ final ploidy.

Chromosome counting for ploidy determination of regenerating buds

After flow cytometry analysis, confirmed tetraploid and diploid A. melanoxylon plants were selected for chromosome counting. Stem tip tissues (0.5–1 cm) were collected between 10:00 AM and 12:00 PM, a period when the mitotic index is relatively high and a larger proportion of cells are in metaphase, which is suitable for accurate chromosome counting. The collected tissues were treated in saturated 1,4-dichlorobenzene solution for 4 h to 6 h, then washed with distilled water and fixed in Carnoy’s fixative (absolute ethanol: acetic acid = 3:1) for 2 h to 24 h at 4 °C. They were then treated in a mixture of concentrated hydrochloric acid and absolute ethanol (1:1) for 15 min to 20 min, followed by rinsing in distilled water 3 to 5 times for 8 min each. The excess water was absorbed using filter paper, and the stem tip tissues were placed on a microscope slide. A drop of carbol fuchsin solution was applied for 5 min for staining, and a coverslip was placed. The chromosomes in the stem tip cells were observed and photographed under a microscope (Olympus BX51).

Observation on growth and stomatal phenotype of diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon

Three plants each of tetraploid and diploid A. melanoxylon tissue culture seedlings, whose ploidy levels had been previously confirmed, were randomly selected after 80 days of transplantation. Plant height, stem diameter and phyllode area were measured. The lower epidermis of the leaves was gently scraped off with clear nail polish and then transferred to a glass slide. Under a 20×, 40×, and 100× objective lens, the stomatal characteristics were observed. For each slide, 10 fields of view were selected, and the number of stomata in each field was recorded along with the stomatal length and width measurements.

Data analysis

Data processing and table creation were performed using Excel 2021. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple comparison tests were conducted using SPSS (version 26, IBM, USA), with the statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Additionally, the stomatal size, stomatal density, and phyllode area were measured using Image J software.

Results

Adventitious bud regeneration from bud-bearing stem segments

After at least two subcultures of the initial explants, the bud-bearing stem segment of A. melanoxylon were inoculated onto differentiation media based on DKW supplemented with various combinations of plant growth regulators (Fig. 1a). After 5 days of culture, obvious basal swelling was observed at the base of the bud-bearing stem segment (Fig. 1b). By day 20, the swollen tissues grew more distinct, with visible white callus forming on their surfaces. Some explants had already developed adventitious buds at this stage (Fig. 1c). After 40 days of culture, due to continued internal differentiation, extensive adventitious bud formation was observed in the swollen tissues (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Establishment of an in vitro regeneration system from bud-bearing stem segment of A. melanoxylon. (a) Bud-bearing stem segment inoculated on differentiation medium. (b) Swelling initiated at the basal region of the explants. (c) Continued expansion of the swollen tissue with the emergence of several adventitious buds. (d) Numerous adventitious buds formed within the swollen tissue. (e) Aerial part of a rooted plantlet. (f) Root system of the rooted plantlet

The statistical analysis revealed that the highest adventitious bud regeneration efficiency occurred when 6-BA was applied at 0.5 mg/L, significantly outperforming other concentrations. However, increasing the 6-BA concentration led to a decline in both regeneration efficiency and survival rates (Table 1). Among the tested treatments, D-2 and D-3 had the highest regeneration efficiency and survival rates, with no significant differences between them. The D-2 formulation was thus selected for subsequent experiments (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of different hormone concentration combinations on adventitious bud regeneration efficiency from bud-bearing stem segment of A. melanoxylon

| Plant growth regulators (mg/L) | Percentage shoot regeneration (%) | Average number of adventitious shoots |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-BA | IAA | NAA | |||

| D-1 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 86.67 ± 3.06bc | 15.28 ± 0.68b |

| D-2 | 0.5 | 0.10 | 0.2 | 96.67 ± 3.06a | 18.07 ± 1.62a |

| D-3 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.3 | 92.00 ± 6.00ab | 17.92 ± 1.42a |

| D-4 | 1.0 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 81.33 ± 4.62c | 13.01 ± 0.51c |

| D-5 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.1 | 84.00 ± 6.00bc | 11.21 ± 0.87d |

| D-6 | 1.0 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 79.33 ± 5.03c | 12.04 ± 0.77cd |

| D-7 | 1.5 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 64.00 ± 7.21d | 7.40 ± 0.46f |

| D-8 | 1.5 | 0.10 | 0.3 | 60.67 ± 6.11d | 9.25 ± 1.02e |

| D-9 | 1.5 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 60.67 ± 3.06d | 8.71 ± 0.47ef |

Note: D-1–D-9 denote different experimental groups. All values are presented as means ± Standard deviation (SD) of three replicates. P < 0.05 was considered significantly different and is shown by different letters

Effect of NAA concentration on rooting of shoots

Once the regenerated adventitious shoots attained a length of over 1.5 cm, they were transferred to the rooting media with varying concentrations of NAA. After 30 days of culture, both the rooting percentage and the number of roots were recorded. The highest rooting percentage and number of roots were observed at an NAA concentration of 0.25 mg/L (Supplementary Table S2; Fig. 1e, f).

Histological analysis of adventitious bud formation

To clarify the type and cellular origin of adventitious buds in A. melanoxylon, anatomical observations were conducted throughout the regeneration process. As shown in Fig. 2a, the transverse sections of the uncultured stem segments had their tissue structure intact, with lightly stained nuclei and the cortical parenchyma cells arranged regularly. During culture, these cells first underwent dedifferentiation, characterized by enlarged cell size, loose arrangement, and increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, producing adventitious bud primordium cells with mitotic potential (Fig. 2b). These primordium cells continued to divide, forming small, densely packed cell clusters with deeply stained nuclei, gradually completing the process of organogenesis (Fig. 2c). Eventually, the bud primordia broke through the epidermis to form well-defined adventitious buds connected to the vascular system in the swollen tissue (Fig. 2d). The anatomical analysis revealed that the adventitious buds of A. melanoxylon originated from the dedifferentiated cortical parenchyma cells in the swollen tissue and not from the white callus formed on the surface. The swollen tissue was composed of densely arranged cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio and strong regenerative activity, whereas the surface callus mainly served as a protective layer and was uninvolved in bud formation.

Fig. 2.

Anatomical observation of adventitious bud regeneration at the basal part of A. melanoxylon bud-bearing stem segment. (a) Transverse section of the stem segment before culture. (b) Dedifferentiation of cortical parenchyma cells into bud primordium cells. (c) Proliferation and organization of bud primordium cells. (d) Development of bud primordium into adventitious buds. Note: Xy - xylem; Ve - vessel; Pe - parenchyma cell; En - enlarged tissue; Mc - meristematic cell; Mn - meristematic nodule; Lp - leaf primordium; Ab - adventitious bud

Observation of developmental status and cell cycle identification of tissues cultured in vitro

The morphological changes of the A. melanoxylon bud-bearing stem segment during micropropagation were observed. When the preculture duration was increased, the stem bases gradually swelled, and white callus tissue began to appear. Compared with the control (0 days), after 1 day of in vitro culture, the basal cut ends of the nodal segments appeared moist, with a light green epidermis (Fig. 3a, b). On day 2, the cut surface began to dry, and the epidermis around the incision turned dark green (Fig. 3c). On day 3, the basal region demonstrated signs of dehydration and contraction, with slight bulging at the center (Fig. 3d). By day 4, the basal region was visibly enlarged, and the epidermis appeared greenish-white (Fig. 3e). On day 5, a small amount of callus tissue began to form on the surface of the swollen basal region, and the epidermis turned white (Fig. 3f). On day 6, prominent white callus tissue was observed on the surface of the swollen basal region (Fig. 3g).

Fig. 3.

Observation of developmental status and detection of cell cycle proportions of tissues cultured in vitro. (a-g) Morphological characterization of the basal region of bud-bearing stem segment of 0-6d. (h-n) Cytological observation of the basal region of bud-bearing stem segment of 0-6d. (o-u) Flow cytometric analysis of the proportion of G1, S, and G2/M phase cells in adventitious bud primordia of 0-6d

Based on the observed morphological changes, continuous histological sections were prepared from the swollen basal region of the A. melanoxylon bud-bearing stem segment from day 0 to day 6 of differentiation culture. On days 1 and 2, the cell structure near the cut surface remained largely intact with regular cell arrangement. Most of the nuclei were faintly stained, with only a few cells having nuclear staining (Fig. 3h–j). By day 3, the staining grew more pronounced, the cell size increased slightly, and the cellular arrangement became looser (Fig. 3k). On day 4, the cells at the wound margin had marked swelling, with some cells becoming irregular in shape and having larger intercellular spaces, indicating active division (Fig. 3l). On day 5, numerous irregularly shaped cells with deeply stained nuclei were observed at the section margins, suggesting vigorous mitotic activity (Fig. 3m). On day 6, the cross-sectional area increased substantially, and a large number of irregularly shaped cells were observed near the incision site. Extensive cell proliferation and disorganized arrangement were evident (Fig. 3n).

The flow cytometry analysis revealed that, prior to preculture, the proportions of the G₁, S, and G₂/M-phase cells in the basal region of the A. melanoxylon bud-bearing stem segment were 76.47%, 7.69%, and 15.84%, respectively (Fig. 3o). On days 1 and 2 of preculture, the distribution of cells in the G₁, S, and G₂/M phases demonstrated no significant changes (Fig. 3p, q). By day 3, the cell cycle distribution began to shift: The G₁-phase cells decreased to 62.14% and the S-phase cells and the G₂/M-phase cells increased to 17.17% and 20.69%, respectively (Fig. 3r). On day 4, the S-phase cells peaked at 23.37%, followed by slight decreases on days 5 and 6 to 18.32% and 13.86%, respectively. During days 4 to 6, the proportion of G₁-phase cells ranged between 53.11% and 60.83%, while the G₂/M-phase cells ranged between 23.52% and 26.29%, both higher than those observed during the first 3 days of preculture (Fig. 3s-u).

Taken together, these results indicate that the basal region of the A. melanoxylon bud-bearing stem segment exhibited pronounced swelling and active cell division at the wound site on day 4 of preculture. By day 5, callus tissue began to appear on the epidermis, with a large number of mitotically active cells observed at the incision. On day 6, evident white callus formed, and numerous proliferating cells were visible at the wound surface. Meanwhile, the flow cytometry results revealed that the proportion of the adventitious bud primordium cells in the G₂/M-phase was higher on days 4, 5, and 6 than during the first 3 days of preculture. The bud-bearing stem segment precultured for 4, 5, and 6 days were thus selected as explants for colchicine treatment.

Colchicine treatment of adventitious bud primordia cells induces tetraploid A. melanoxylon

Different combinations of colchicine concentration and treatment duration had varying effects on the explants’ survival rate. When the preculture duration was 4 days, increasing the colchicine concentration and exposure time resulted in a gradual decline in explant survival, with the lowest survival rate being 26.67 ± 5.77%. With longer preculture durations (5 and 6 days), the explants’ tolerance enhanced, and increases in colchicine concentration and treatment time led to only slight reductions in their survival rates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of different preculture time, Colchicine concentration and treatment time on somatic chromosome doubling in A. melanoxylon

| Treatment number | Colchicine concentration (mg/L) | Preculture duration (d) | Exposure time (h) | Survival rate (%)a | No. of regenerated shoots b | No. of mixoploidc | No. of tetraploidd | Tetraploid induction rate (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 4 | 24 | 46.67 ± 5.77 | 86 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 2 | 4 | 48 | 36.67 ± 11.55 | 75 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 3 | 4 | 72 | 30.00 ± 0.00 | 50 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 4 | 5 | 24 | 70.00 ± 10.00 | 158 | 0 | 1 | 0.55 ± 0.95 | |

| 5 | 5 | 48 | 60.00 ± 10.00 | 114 | 1 | 2 | 1.90 ± 1.65 | |

| 6 | 5 | 72 | 83.33 ± 5.77 | 153 | 2 | 3 | 1.97 ± 0.20 | |

| 7 | 6 | 24 | 90.00 ± 10.00 | 186 | 2 | 3 | 1.61 ± 0.07 | |

| 8 | 6 | 48 | 86.67 ± 5.77 | 165 | 3 | 1 | 0.61 ± 1.05 | |

| 9 | 6 | 72 | 80.00 ± 10.00 | 152 | 3 | 2 | 1.25 ± 1.09 | |

| 10 | 80 | 4 | 24 | 40.00 ± 10.00 | 81 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 11 | 4 | 48 | 30.00 ± 0.00 | 54 | 1 | 1 | 1.52 ± 2.62 | |

| 12 | 4 | 72 | 26.67 ± 5.77 | 61 | 1 | 2 | 2.92 ± 2.56 | |

| 13 | 5 | 24 | 66.67 ± 5.77 | 124 | 1 | 7 | 5.47 ± 2.34 | |

| 14 | 5 | 48 | 76.67 ± 15.28 | 136 | 3 | 8 | 6.48 ± 3.09 | |

| 15 | 5 | 72 | 76.67 ± 5.77 | 129 | 2 | 12 | 9.37 ± 1.01 | |

| 16 | 6 | 24 | 86.67 ± 15.28 | 140 | 2 | 3 | 2.22 ± 0.51 | |

| 17 | 6 | 48 | 80.00 ± 17.32 | 121 | 4 | 4 | 3.28 ± 1.22 | |

| 18 | 6 | 72 | 83.33 ± 15.28 | 144 | 4 | 8 | 5.60 ± 0.71 | |

| 19 | 100 | 4 | 24 | 40.00 ± 0.00 | 87 | 0 | 1 | 1.11 ± 1.92 |

| 20 | 4 | 48 | 36.67 ± 5.77 | 68 | 2 | 3 | 4.43 ± 0.31 | |

| 21 | 4 | 72 | 30.00 ± 10.00 | 54 | 1 | 3 | 6.27 ± 2.64 | |

| 22 | 5 | 24 | 83.33 ± 20.82 | 146 | 3 | 9 | 6.35 ± 1.38 | |

| 23 | 5 | 48 | 86.67 ± 5.77 | 149 | 3 | 17 | 11.47 ± 0.87 | |

| 24 | 5 | 72 | 80.00 ± 20.00 | 139 | 2 | 17 | 12.26 ± 0.80 | |

| 25 | 6 | 24 | 73.33 ± 25.17 | 148 | 4 | 6 | 4.58 ± 1.74 | |

| 26 | 6 | 48 | 96.67 ± 5.77 | 165 | 5 | 9 | 5.62 ± 1.11 | |

| 27 | 6 | 72 | 90.00 ± 10.00 | 167 | 4 | 11 | 6.78 ± 1.84 | |

| Total | - | - | - | - | 3252 | 56 | 133 |

Note: a: Average percentage of surviving explants from three independent experiments. All values are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). b, c, d: Total values from three independent replicates. e: Average induction rate from three independent experiments. All values are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD)

In total, 3,252 regenerated shoots were obtained from diploid A. melanoxylon under 27 different colchicine treatment combinations (Table 2), among which 133 were tetraploids and 56 were chimeras. Tetraploids could be induced under varying colchicine concentrations, treatment durations, and preculture periods. However, lower colchicine concentrations and shorter treatment durations resulted in lower induction efficiency (Table 2). When the colchicine concentration was 60 mg/L, the tetraploid induction rates remained low across different preculture durations and treatment combinations. When the concentration exceeded 80 mg/L, higher tetraploid induction rates were achieved after 4, 5, or 6 days of preculture. The highest tetraploid induction rate, 12.26 ± 0.80%, was obtained from the explants precultured for 5 days and treated with 100 mg/L colchicine for 72 h (Table 2). However, during induction, the number of chimeras increased with prolonged preculture duration. Although tetraploids could still be obtained on day 6, the number of chimeric plants was significantly higher than on day 4. In contrast, the explants treated on day 5 exhibited not only the highest tetraploid induction rate but also a relatively lower proportion of chimeras (Table 2), indicating that day 5 is the optimal timing for chromosome doubling.

To investigate the effects of preculture duration and treatment time on tetraploid induction efficiency, the data from colchicine treatments at a concentration of 100 mg/L were analyzed. Under the same preculture duration, longer treatment times generally led to higher induction efficiency; however, there was no significant difference between 48 h and 72 h treatments (Supplementary Fig. 1a). When comparing the different preculture durations under the same treatment time, the tetraploid induction efficiency on day 5 was significantly higher than on other days. On day 6, the induction rate was significantly higher than that on day 4 only under 24 h treatment and showed no significant difference compared to day 5 (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Tetraploid identification of the regenerated A. melanoxylon plantlets

The ploidy level of the regenerated plantlets was identified using flow cytometry. The diploid plants exhibited a fluorescence peak near channel 60 (Fig. 4a), while the tetraploid plants showed a peak near channel 120 (Fig. 4b). Chromosome counting was then used to further confirm the ploidy level. The root tip squashes revealed that the diploid plants had 2n = 2x = 26 chromosomes (Fig. 4c), while the tetraploid plants had 2n = 4x = 52 chromosomes (Fig. 4d), consistent with the flow cytometry results.

Fig. 4.

Ploidy identification of regenerated A. melanoxylon plantlets. (a) Flow cytometry result of diploid plantlets. (b) Flow cytometry result of tetraploid plantlets. (c) Chromosome number of diploids (2n = 2x = 26). (d) Chromosome number of tetraploids (2n = 4x = 52)

Phenotypic variation in growth traits between diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon

Morphological observations were made on the diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon plantlets 80 days after transplantation. The distinct differences in plant height, stem thickness, and leaf characteristics between the two ploidy levels were noted. The height was measured every 20 days. The tetraploid plants demonstrated significantly slower growth rates, with their rate of growth gradually declining over time (Fig. 5c). After 80 days of growth, the tetraploid plants’ average height was 11.88 ± 1.23 cm, which was 41.96% lower than that of the diploid plants (Fig. 5a, c). The stem diameter at the 5th internode of the tetraploid plants was 0.76 ± 0.05 mm, significantly greater than that of the diploids, representing a 1.85-fold increase (Fig. 5d). Compared to the diploid, the tetraploid exhibited a significantly reduced number of leaves (Fig. 5e). Moreover, the tetraploid plants’ phyllode area was smaller, while their phyllode thickness was significantly greater (Fig. 5b, f, and g).

Fig. 5.

Morphological comparison of diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon plantlets at 80 days after transplantation. (a) Comparison of plant height between diploid and tetraploid plants. (b) Comparison of leaf morphology between diploid and tetraploid plants. (c) Growth curve of diploid and tetraploid plants over 80 days. (d) Stem diameter at the 5th internode in diploid and tetraploid plants. (e) Number of leaves per plant in diploid and tetraploid plants. (f) Phyllode area of diploid and tetraploid plants. (g) Phyllode thickness of diploid and tetraploid plants. All values represent the mean ± SD. Asterisks denote significant differences, determined by Student’s t-test: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001

Stomatal variation analysis between diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon

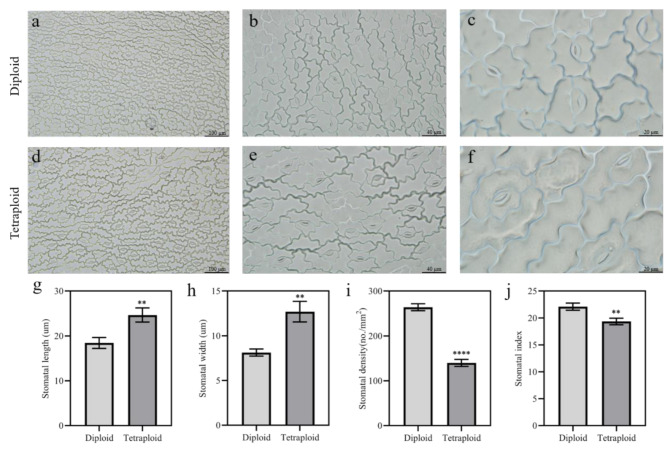

The stomatal length, width, and density were examined in the leaves of the diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon under a microscope. The observations made at 100×, 40×, and 20× magnifications revealed clear differences in stomatal size and density between the two ploidy levels (Fig. 6a–f). The average stomatal length and width in diploid leaves were 18.42 ± 1.21 μm and 8.12 ± 0.39 μm, respectively, while in tetraploids they reached 24.66 ± 1.58 μm and 12.68 ± 1.16 μm (Fig. 6g, h). Accordingly, the stomatal length and width in tetraploids were 1.34 and 1.56 times greater than those in diploids, respectively (Fig. 6g, h). The stomatal density and stomatal index of tetraploid plants were significantly reduced, the former decreased by 47.06% and the latter decreased by 12.40% (Fig. 6i, j).

Fig. 6.

Stomatal phenotypic characteristics of diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon at 80 days after transplantation. (a) Stomatal morphology of diploid leaves under 100× magnification. (b) Stomatal morphology of diploid leaves under 40× magnification. (c) Stomatal morphology of diploid leaves under 20× magnification. (d) Stomatal morphology of tetraploid leaves under 100× magnification. (e) Stomatal morphology of tetraploid leaves under 40× magnification. (f) Stomatal morphology of tetraploid leaves under 20× magnification. (g) Stomatal length in diploid and tetraploid plants. (h) Stomatal width in diploid and tetraploid plants. (i) Stomatal density in diploid and tetraploid plants. (j) Stomatal index in diploid and tetraploid plants. All values represent the mean ± SD. Asterisks denote significant differences, determined by Student’s t-test: **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001

Discussion

During the process of somatic chromosome doubling in plants, if induction occurs precisely at the first metaphase of mitosis in the adventitious bud primordium cells, stable and homogeneous tetraploids can be efficiently obtained [24]. Treating the adventitious bud primordium cells derived from the leaf [44, 45] and stem segment [46] explants at appropriate stages of in vitro culture with chemical agents can effectively and stably induce homozygous tetraploids in poplar. Similarly, the colchicine treatment of leaves after differentiation culture results in high tetraploid induction efficiency in Lycium [14, 47]. In addition, the colchicine treatment of leaf explants in Ziziphus jujuba var. spinosa successfully yields homozygous tetraploids [48]. Regarding Acacia, establishing a regeneration system using stem segments or leaf explants is relatively challenging [49]. In this study, we found that during the micropropagation of A. melanoxylon using bud-bearing stem segment, the basal region of the segments readily swelled and produced adventitious buds during subculture. The histological analysis of the swollen basal tissues revealed that the cortical parenchyma cells readily dedifferentiated into meristematic primordium cells, which directly initiated adventitious bud formation (Fig. 2). The regeneration efficiency was high, with each explant producing an average of 18.07 ± 1.62 buds (Table 1). By applying colchicine to the adventitious bud primordium cells formed in the swollen basal region of the bud-bearing stem segment, pure tetraploid plantlets were successfully obtained from the explants precultured for 4, 5, or 6 days. We thus propose a novel method for inducing somatic chromosome doubling in A. melanoxylon by applying colchicine treatment to the adventitious bud formation pathway at the basal part of bud-bearing stem segment during in vitro micropropagation.

The preculture duration of the explant materials is one of the key factors influencing the efficiency of somatic chromosome doubling [23, 50]. In the doubling process, the timely application of colchicine to the adventitious bud primordium cells is crucial for the efficient and stable induction of homozygous tetraploids [24]. When the explants are cultured on a differentiation medium, the cortical parenchyma cells gradually dedifferentiate into bud primordium cells, and the proportion of primordium cell formation varies across different culture stages [51]. The timing at which the primordium cell formation peaks differ among plant species and explant types. Previous studies have shown that in Populus, the optimal preculture duration for leaf explants to reach the appropriate stage of callus development varies among genotypes, typically ranging from day 3 to day 9. Applying colchicine at the peak period of adventitious bud primordium cell formation can significantly enhance the tetraploid induction efficiency [24]. In Lycium, the highest tetraploid induction efficiency was achieved when the excised leaves were precultured for 12 days [47]. In this study, we found that applying colchicine treatment to the adventitious bud-inducing explants precultured for 4, 5, or 6 days consistently yielded stable tetraploid plantlets, which indicates that, during this period, the bud primordium cells were undergoing a mitotic peak, making it an optimal window for chromosome doubling. Moreover, our concurrent phenotypic, cytological, and flow cytometric analyses revealed that the basal region of the nodal segments was markedly swollen on days 4 to 6 and exhibited active cell division. The proportion of the G2/M-phase cells ranged between 23.52% and 26.29%, higher than the range (16.23–20.69%) observed during the first 3 days of preculture (Fig. 3). Among the tested time points, preculturing for 5 days resulted in the highest tetraploid induction efficiency, suggesting that the proportion of adventitious bud primordium cells was highest on day 5, when the G2/M-phase cell ratio peaked at 26.29%. In comparison, although the explants precultured for 4 and 6 days also exhibited relatively high proportions of G₂/M-phase cells and enabled the induction of some tetraploids, the induction performed on day 4 resulted in a lower survival rate due to the shorter culture duration. Meanwhile, when preculture was extended to day 6, the number of chimeric plants tended to increase, probably because some of the bud primordium cells had entered the second metaphase of mitosis. Accurately identifying the developmental dynamics of the bud primordium cells and optimizing the colchicine treatment window for different explant types is thus essential for the efficient and stable induction of homozygous tetraploids.

Chromosome doubling often leads to morphological changes in plants [52]. For example, in Populus, chromosome doubling to the tetraploid level resulted in larger and thicker leaves, reduced height, and increased stem diameter [45]. Similarly, tetraploid Betula platyphylla exhibited greater stem diameter at breast height, overall stem thickness, and leaf area compared to diploids; however, its height was reduced [53]. In Citrus, the tetraploid plants exhibited significantly thicker leaves, thicker stems, and larger and heavier fruits [54], although the plants themselves tend to be shorter in stature [55]. The morphological observations of the diploid and tetraploid A. melanoxylon revealed that the tetraploid plants were significantly shorter in height, exhibited slower growth rates, and had fewer leaves. However, they had thicker stems and thicker phyllodes (Fig. 5). These growth characteristics suggest that tetraploid A. melanoxylon can serve as an intermediate material, providing a genetic and morphological foundation for future polyploid breeding programs. In addition, stomatal changes are among the most prominent features associated with polyploidization [8, 56]. In Eucalyptus, both the triploid and tetraploid plants show significantly larger stomatal size and lower stomatal density compared to diploids [28, 57]. Similarly, compared to diploids, tetraploid Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits significantly reduced stomatal density, along with significantly increased stomatal length and width [58]. In this study, A. melanoxylon exhibited stomatal characteristics consistent with the patterns observed in other polyploid species: the stomatal length and width of tetraploids were significantly greater than those of diploids, while their stomatal density was significantly lower than that of diploids (Fig. 6). Stomatal traits can thus serve as a rapid and straightforward method for identifying polyploid plants. These morphological changes are commonly attributed to gene dosage effects, whereby chromosome doubling alters gene expression, subsequently affecting cell structure and function and, ultimately, leading to phenotypic changes in the plant [59]. Future studies could further explore the molecular mechanisms underlying these morphological changes, thereby deepening our understanding of the genetic variation patterns in polyploid plants.

This study is the first to establish a tetraploid induction system for A. melanoxylon based on in vitro adventitious bud regeneration, in which both an adventitious bud regeneration system and an efficient tetraploid induction protocol were successfully developed, thereby enriching the polyploid breeding system of Acacia species. By integrating morphological, cytological, and flow cytometric analyses to examine the developmental status of the swollen basal tissues of bud-bearing stem segments and the cell cycle distribution of adventitious bud primordium cells at different culture stages during micropropagation, the optimal treatment period was identified, significantly improving the efficiency and stability of tetraploid induction. Although this study was only validated in a single genotype, it provides a valuable reference for future chromosome doubling studies in Acacia and other species that generate adventitious buds from the basal part of bud-bearing stem segments. In addition, this study only conducted preliminary analyses of the growth phenotypes and stomatal characteristics of tetraploid plants, and further systematic evaluations of their long-term growth performance, stress resistance, and wood properties are required. Given the superior growth performance of triploid Acacia [60–62], the tetraploid lines developed in this study offer crucial germplasm for future hybridization with diploids to generate triploid offspring, offering critical germplasm resources and technical support for the genetic improvement of A. melanoxylon.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed an efficient and stable in vitro tetraploid induction system for A. melanoxylon using bud-bearing stem segments. A regeneration system based on bud-bearing stem segments was first established. Building upon this system, morphological observation, cytological analysis, and flow cytometry detection of the swollen tissues at the base of the explants were conducted to determine the optimal preculture period. The results indicated that day 5 was optimal, as the G₂/M-phase cell population peaked at this stage. Colchicine treatment at this time point significantly improved the tetraploid induction rate, with the highest efficiency achieved at 100 mg/L for 72 h. Cytological and phenotypic analyses confirmed the successful induction of pure tetraploid plants, which exhibited typical polyploid traits such as reduced plant height and stomatal density. The regeneration system established in this study provides an effective approach for the industrial-scale propagation and transgenic functional studies of A. melanoxylon. Moreover, the development of an efficient tetraploid induction method has produced fundamental materials for future polyploid breeding of A. melanoxylon, particularly for triploid breeding programs. This provides important theoretical support and practical foundations for the genetic improvement, elite cultivar development, and industrial application of A. melanoxylon.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiang S, Kang X; experimental suggestions and protocol refinement: Jiang S, Xia Y, Ling A; data analysis and manuscript translation: Jiang S, Shu J, You K, and Wang S; figure revision and critical comments: Zhan D, Zeng B and Yang J; manuscript writing: Jiang S; manuscript revision and supervision: Kang X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethics

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Celesti-Grapow L, Bassi L, Brundu G, Camarda I, Carli E, D’Auria G, et al. Plant invasions on small mediterranean islands: an overview. Plant Biosyst. 2016;150(5):1119–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemetova C, Ribeiro H, Fabiao A, Gominho J. Towards sustainable valorisation of Acacia melanoxylon biomass: characterization of mature and juvenile plant tissues. Environ Res. 2020;191:110090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradbury GJ, Potts BM, Beadle CL. Genetic and environmental variation in wood properties of Acacia melanoxylon. Ann for Sci. 2011;68(8):1363–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado JS, Louzada JL, Santos AJ, Nunes L, Anjos O, Rodrigues J, et al. Variation of wood density and mechanical properties of Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon R. Br). Mater Des. 2014;56:975–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradbury GJ, Beadle CL, Potts BM. Genetic control in the survival, growth and form of Acacia melanoxylon. New for. 2010;39(2):139–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan C, Liu Q, Zeng B, Qiu Z, Zhou C, Chen K, et al. Development of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and genetic diversity analysis in Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon) clones in China. Silvae Genet. 2016;65(1):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang R, Zeng B, Chen T, Hu B. Genotype environment interaction and horizontal and vertical distributions of Heartwood for Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. Genes-Basel. 2023;14(6):1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang X, Wei H. Breeding polyploid Populus: progress and perspective. Res. 2022;2(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao T, Cheng S, Zhu X, Min Y, Kang X. Effects of triploid status on growth, photosynthesis, and leaf area in Populus. Trees-Struct Funct. 2016;30(4):1137–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Yang J, Song L, Qi Q, Du K, Han Q, et al. Study of variation in the growth, photosynthesis, and content of secondary metabolites in Eucommia triploids. Trees-Struct Funct. 2019;33(3):817–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lourkisti R, Froelicher Y, Herbette S, Morillon R, Giannettini J, Berti L, et al. Triploidy in citrus genotypes improves leaf gas exchange and antioxidant recovery from water deficit. Front Plant Sci. 2021;11:615335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu Z, Lin H, Kang X. Studies on allotriploid breeding of Populus tomentosa B301 clones. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 1995;31(6):499–505. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Z. Studies on selection of natural triploids of Populus tomentosa. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 1998;34:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao S, Kang X, Li J, Chen J. Induction, identification and characterization of tetraploidy in Lycium ruthenicum. Breed Sci. 2019;69(1):160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Zhan D, Pang Z, Zhao J, et al. Comparative transcriptomic, anatomical and phytohormone analyses provide new insights into hormone-mediated tetraploid dwarfing in hybrid Sweetgum (Liquidambar Styraciflua × L. formosana). Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:924004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernando SC, Goodger JQ, Chew BL, Cohen TJ, Woodrow IE. Induction and characterisation of tetraploidy in Eucalyptus polybractea RT Baker. Ind Crop Prod. 2019;140:111633. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu C, Zhang Y, Han Q, Kang X. Molecular mechanism of slow vegetative growth in tetraploid. Genes. 2020;11(12):1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felber F, Bever JD. Effect of triploid fitness on the coexistence of diploids and tetraploids. Biol J Linn Soc. 1997;60(1):95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Zheng Z, Wang J, Li Y, Gao Y, Li L, et al. In vitro induction of tetraploids and their phenotypic and transcriptome analysis in Glehnia littoralis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Zhao P, Zeng F, Geng X, Zhou J, Sun J. Induction and identification of polyploids in four Rhododendron species. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2024;158(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kushwah KS, Patel S, Chaurasiya U, Wani MB. The effect of Colchicine on Vicia Faba and Chrysanthemum carinatum (L.) plants and their cytogenetical study. Vegetos. 2021;34(3):432–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdolinejad R, Shekafandeh A, Jowkar A. In vitro tetraploidy induction creates enhancements in morphological, physiological and phytochemical characteristics in the Fig tree (Ficus carica L). Plant Physiol Bioch. 2021;166:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai X, Kang X. In vitro tetraploid induction from leaf explants of Populus pseudo-simonii Kitag. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(9):1771–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu C, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Yao P, Li Y, Kang X. Impact of the leaf cut callus development stages of Populus on the tetraploid production rate by Colchicine treatment. J Plant Growth Regul. 2017;37(2):635–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou J, Guo F, Fu J, Xiao Y, Wu J. In vitro polyploid induction using colchicine for Zingiber Officinale Roscoe cv. ‘Fengtou’ ginger. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2020;142(4):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen KK, Hagberg P, Kristiansen K, Forkmann G. In vitro chromosome doubling of miscanthus sinensis. Plant Breeding. 2002;121(5):445–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Lin Y, Pei H, Zhang J, Zhang J, Luo J. Variations in colchicine-induced autotetraploid plants of Lilium Davidii var. Unicolor. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2020;141(3):479–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Wang J, Qiu B, Ma Z, Lu T, Kang X, et al. Induction and characterization of tetraploid through zygotic chromosome doubling in Eucalyptus urophylla. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:870698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Song S, Li D, Lu X, Liu J, Zhang J, et al. Isolation of diploid and tetraploid cytotypes from mixoploids based on adventitious bud regeneration in Populus. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2019;140(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marangelli F, Pavese V, Vaia G, Lupo M, Bashir MA, Cristofori V, et al. In vitro polyploid induction of highbush blueberry through de Novo shoot organogenesis. Plants. 2022;11(18):2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen C, Hu Y, Ikeuchi M, Jiao Y, Prasad K, Su Y, et al. Plant regeneration in the new era: from molecular mechanisms to biotechnology applications. Sci China Life Sci. 2024;67(7):1338–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shariatpanahi ME, Niazian M, Ahmadi B. Methods for chromosome doubling. 2021; pp.127– 48. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1315-3_5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Long Y, Yang Y, Pan G, Shen Y. New insights into tissue culture plant-regeneration mechanisms. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:926752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asghar S, Ghori N, Hyat F, Li Y, Chen C. Use of auxin and cytokinin for somatic embryogenesis in plant: a story from competence towards completion. Plant Growth Regul. 2023;99(3):413–28. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Song C, Han Y, Wang R, Guan L, Mu Y, et al. Construction of a genetic transformation system for Populus wulianensis. Forests. 2024;15(8):1474. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Bozorov TA, Li D, Zhou P, Wen X, Ding Y, et al. An efficient in vitro regeneration system from different wild Apple (Malus sieversii) explants. Plant Methods. 2020;16(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu M, Cheng S, Tang G, Hu Z, Chen L, Tang J, et al. Effects of spraying exogenous hormones IAA and 6-BA on sprouts of Pinus yunnanensis seedlings after stumping. Forests. 2025;16(1):92. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng Y, Cui Y, Shang X, Fu X. Fitting levels of 6-benzylademine matching seasonal explants effectively stimulate adventitious shoot induction in Cyclocarya Paliurus (Batal.) Iljinskaja. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2023;156(2):38. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer HJ, van Staden J. Regeneration of Acacia melanoxylon plantlets in vitro. S Afr J Bot. 1987;53(3):206–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu F, Shi Q, Huang L. Acacia melanoxylon callus induction and shoot regeneration system. Chin Bull Bot. 2014;49(5):603. (In chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng Q, Han Z, Kang X. Adventitious shoot regeneration from leaf, petiole and root explants in triploid (Populus Alba × P. glandulosa) × P. tomentosa. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2019;138(1):121–30. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davidson JM, Duronio RJ. Using drosophila S2 cells to measure S phase-coupled protein destruction via flow cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;782:205–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang S, Zeng K, Luo L, Qian W, Wang Z, Dolezel J, et al. A flow cytometry-based analysis to Establish a cell cycle synchronization protocol for Saccharum spp. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu C, Huang Z, Liao T, Li Y, Kang X. In vitro tetraploid plants regeneration from leaf explants of multiple genotypes in Populus. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2015;125(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren Y, Jing Y, Kang X. In vitro induction of tetraploid and resulting trait variation in Populus Alba × Populus glandulosa clone 84 K. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2021;146(2):285–96. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng Q, Liu Z, Du K, Kang X. Oryzalin-induced chromosome doubling in triploid Populus and its effect on plant morphology and anatomy. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2019;138(3):571–81. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang R, Rao S, Wang Y, Qin Y, Qin K, Chen J. Chromosome doubling enhances biomass and carotenoid content in Lycium Chinense. Plants. 2024;13(3):439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui Y, Hou L, Li X, Huang F, Pang X, Li Y. In vitro induction of tetraploid Ziziphus Jujuba mill. Var. Spinosa plants from leaf explants. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2017;131(1):175–82. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gantait S, Kundu S, Das PK. Acacia: an exclusive survey on in vitro propagation. J Saudi Soc Agricultural Sci. 2018;17(2):163–77. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhooghe E, Van Laere K, Eeckhaut T, Leus L, Van Huylenbroeck J. Mitotic chromosome doubling of plant tissues in vitro. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2011;104(3):359–73. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Y, Cao Y, Ren Y, Ling A, Du K, Li Y, et al. Effect of a suitable treatment period on the genetic transformation efficiency of the plant leaf disc method. Plant Methods. 2023;19(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madani H, Escrich A, Hosseini B, Sanchez-Muñoz R, Khojasteh A, Palazon J. Effect of polyploidy induction on natural metabolite production in medicinal plants. Biomolecules. 2021;11(6):899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mu H, Liu Z, Lin L, Li H, Jiang J, Liu G. Transcriptomic analysis of phenotypic changes in Birch (Betula platyphylla) autotetraploids. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(10):13012–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sudo M, Yasuda K, Yahata M, Sato M, Tominaga A, Mukai H, et al. Morphological characteristics, fruit qualities and evaluation of reproductive functions in autotetraploid Satsuma Mandarin (Citrus Unshiu Marcow). Agronomy-Basel. 2021;11(12):2441. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jokari S, Shekafandeh A, Jowkar A. In vitro tetraploidy induction in Mexican lime and sour orange and evaluation of their morphological and physiological characteristics. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2022;150(3):651–68. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia Y, Jiang S, Wu W, Du K, Kang X. MYC2 regulates stomatal density and water use efficiency via targeting EPF2/EPFL4/EPFL9 in Poplar. New Phytol. 2024;241(6):2506–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, Wang J, Liu Z, Xiong T, Lan J, Han Q, et al. Megaspore chromosome doubling in Eucalyptus urophylla S.T. Blake induced by Colchicine treatment to produce triploids. Forests. 2018;9(11):278. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monda K, Araki H, Kuhara S, Ishigaki G, Akashi R, Negi J, et al. Enhanced stomatal conductance by a spontaneous Arabidopsis tetraploid, Me-0, results from increased stomatal size and greater stomatal aperture. Plant Physiol. 2016;170(3):1435–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Z. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:377–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le S, Griffin RA, Harwood CE, Vaillancourt RE, Harbard JL, Price A, et al. Breeding polyploid varieties of acacia: reproductive and early growth characteristics of the allotetraploid hybrid (Acacia mangium × A. auriculiformis) in comparison with diploid progenitors. Forests. 2021;12(6):778. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duc Viet D, Ma T, Inagaki T, Tu Kim N, Quynh Chi N, Tsuchikawa S. Physical and mechanical properties of fast growing polyploid acacia hybrids (A. auriculiformis × A. mangium) from Vietnam. Forests. 2020;11(7):717. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bon PV, Harwood CE, Nghiem QC, Thinh HH, Son DH, Chinh NV. Growth of triploid and diploid Acacia clones in three contrasting environments in Viet Nam. Aust Forestry. 2020;83(4):265–74. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.