Abstract

Background

The rumen hosts a diverse microbial community and serves as a natural bioreactor that efficiently utilizes plant biomass. To explore the potential of sorghum-sudangrass silage (SS) as an alternative to whole-plant corn silage (WS), this study evaluated the growth performance, rumen microbiota, serum metabolome, and rumen fermentation characteristics of Hu sheep. The aim was to assess the feasibility of SS as a feed resource and to identify specific rumen bacteria that interact with host metabolism.

Results

Feeding Hu sheep a diet containing 50% WS and 50% SS (T1 group) improved both growth performance and rumen fermentation compared to a diet of 100% WS (T0 group). In contrast, replacing WS entirely with SS (T2 group) did not affect growth performance. Microbiome analysis revealed that SS inclusion increased the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria. In particular, the T1 group showed an enrichment of Sphingomonas, while the T2 group had higher levels of Bacillus, Enterococcus, and Ruminobacter. Metabolomic analysis indicated that both T1 and T2 diets enhanced purine metabolism.

Conclusion

Partial replacement (50%) of WS with SS improves rumen microbial composition, promotes purine metabolism, enhances rumen fermentation, and supports better growth performance in Hu sheep. These findings demonstrate that SS is a promising alternative to WS for enhancing growth and rumen function in ruminants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04211-0.

Keywords: Sorghum-sudangrass silage, Growth performance, Sheep, Rumen fermentation, Microbiota structure, Serum metabolome

Introduction

In recent years, climatic challenges such as drought and delayed planting due to extreme soil conditions have posed considerable risks to corn cultivation for silage production [1]. Mycotoxin contamination is also a significant challenge in corn silage production [2]. As a result, sorghum-sudangrass (Sorghum × Drummondii) has emerged as a promising alternative forage crop for silage. This hybrid, developed from Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and Sudangrass (Sorghum bicolor subsp. drummondii), is an annual forage grass with the advantages of strong hybrid dominance, high nutritive value, and substantial biomass yield [3–5]. It is also well-suited for double-cropping systems and grazing systems [6].

Studies by Sawal and Sharma [7] have demonstrated that sorghum-sudangrass is suitable for feeding adult sheep and is particularly advantageous in drought-prone and water-scarce regions. Compared with other forages, sorghum-sudangrass exhibits greater resistance to various abiotic stresses and is more cost-effective to cultivate [8]. It also produces greater biomass and sugar content and demonstrates higher water-use efficiency than other sorghum varieties [9]. Furthermore, it often outperforms corn under water-limited conditions [10].

Despite these agronomic advantages, the high biomass and water content of sorghum-sudangrass pose challenges for preservation. Ensiling is a widely adopted strategy worldwide for preserving green fodder [11] and it has been shown to enhance palatability for ruminants [12, 13]. Several studies have reported that superior-quality silage can be made from sorghum-sudangrass [14–16] and is already used by some farmers as roughage for ruminant feeding [1, 17]. However, the effects of feeding sorghum-sudangrass silage (SS) on rumen microbes and host metabolism remain poorly understood. As the primary site for roughage digestion in ruminants, the rumen hosts a complex microbial ecosystem that plays a central role in nutrient utilization, host metabolism, and phenotypic expression [18, 19].

This study investigated the effectiveness of SS as a feed component in Hu sheep. Specifically, it aims to evaluate the potential of SS as a bioactive forage resource and to explore its influence on the rumen microbial community and host metabolic interactions.

Materials and methods

Sorghum-Sudangrass silage preparation

Sorghum-sudanense was harvested at about 65% moisture content and chopped to 1 to 2 cm. It was then ensiled in a pressure cellar with the addition of freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria powder. After 60 d of fermentation, the silo was opened for feeding. The content of dry matter (method 930.15), crude protein (method 991.20.15), Ca (method 985.01), and P (method 985.01) in the feed were determined according to the methods prescribed by the AOAC [20]. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) were determined according to the method of Van Soest et al. [21], using the Ankom system [22].

Experimental animals and feeding management

Thirty healthy Hu sheep (average body weight: 25.57 ± 0.84 kg; age: 4 months) were randomly allocated to three treatment groups: T0 (diet containing whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage, 100% WS), T1 (50% of WS in the T0 diet was replaced with SS, 50% WS + 50% SS), and T2 (100% of WS in the T0 diet was replaced with SS, 100% SS), with 10 sheep in each group. The experiment lasted for 40 d, including a 10-d adaptation period and a 30-d formal experimental period. The experimental diets were formulated according to the feeding standard of Chinese meat goat nutritional requirement (NY/T 816 2021), and the composition and nutritional level of each group of diets are shown in Table 1. Prior to the experiment, all sheep were dewormed and vaccinated. Each sheep was fed equal portions twice daily at 8:00 and 20:00, with free access to clean water and space for exercise.

Table 1.

Experimental diet formulation and nutritional composition (dry matter basis)

| Items1 | Group2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | |

| Ingredients | |||

| WS | 50 | 25 | 0 |

| Wheat straw | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| SS | 0 | 25 | 50 |

| Corn | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Wheat bran | 9 | 10 | 9.5 |

| Corn | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Soybean meal | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| Corn protein powder | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Urea | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| CaHCO3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 |

| Talcum powder | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Salt | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Premix3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Nutrient composition | |||

| Metabolizable energy (MJ/Kg)4 | 10.04 | 9.95 | 10.00 |

| Crude protein (%) | 14.27 | 14.59 | 14.40 |

| Neutral detergent fiber (%) | 48.08 | 50.75 | 49.26 |

| Acid detergent fiber (%) | 25.78 | 26.48 | 24.76 |

| Ca (%) | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.89 |

| P (%) | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.54 |

1WS, Whole-plant corn silage; SS, Sorghum-sudangrass silage

2T0: Diet contained WS and wheat straw as roughage. T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS. T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

3The premix provides (per kg): VA 10 000 IU, VD3 1 000 IU, VE 100 mg, niacin 30 mg, Fe 32 mg, Cu 5 mg, Zn 18.5 mg, Mn 10 mg, I 0.5 mg, Co 0.1 mg

4Calculated according to nutrient requirements of sheep

Growth performance

At the start and the end of the experiment, all sheep were weighed before morning feeding to determine their average daily gain (ADG). Feed offered and refusals were accurately recorded daily for each group to calculate the average dry matter intake (DMI) and feed conversion ratio (FCR).

Collection of rumen fluid and determination of fermentation parameters

At the end of the formal experimental period, six sheep were randomly selected from each group for rumen fluid collection. Prior to sampling, sheep were deprived of both water and feed for 12 h. Rumen fluid was collected using an oral stomach tube. The initial portion was discarded to avoid contamination with saliva. Subsequently, 15 mL of rumen fluid was collected, filtered through four layers of gauze, and the pH was measured immediately using a calibrated pH meter.

The filtered rumen fluid was then dispensed into four 5 mL centrifuge tubes, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until further analysis. These samples were analyzed for concentrations of volatile fatty acid (VFA), microbial protein (MCP), and ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) and were used for DNA extraction. Volatile fatty acid concentrations were determined using gas chromatography (GC-14B, Kyoto, Japan) [23]. Microbial protein was determined using the trichloroacetic acid method [24], and NH3-N concentration was measured using the phenol-sodium hypochlorite colorimetric method [25].

Determination of rumen microorganisms

DNA extraction, 16 S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing

The frozen rumen fluid was thawed at room temperature, and 1 mL of each sample was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. The supernatant was discarded, and DNA was extracted from the pellet using the bead-beating method followed by phenol-chloroform extraction, performed with a mini bead blender (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA purity and concentration were examined using an ultra-micro spectrophotometer (NanoDrop-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and DNA quality was then verified using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Qualified DNA samples were stored at − 80 °C until further processing.

Next-generation sequencing library preparation and Illumina MiSeq sequencing were performed by Novogene (Tianjin, China). The V3-V4 variable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using primers 5’-CCTACGGRRBGCASCAGKVRVGAAT-3’ and 3’-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAATCC-5’. All PCR reactions were performed in a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) with 4 µL of fivefold FastPfu buffer, 10 ng of template DNA, 0.8 µM of each primer, 0.5 U of Pfu polymerase, and 2 µL of 2.5 mM dNTP per 50 uL PCR system. PCR amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 27 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Amplicons were purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA). Thereafter, amplicon libraries were generated using the TruSeqTM DNA Sample Preparation Kit (TransGen Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Paired-end sequencing (2 × 250 bp) was performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform.

Low-quality portions of the sequence were trimmed, and sample data were extracted using Cutadapt V1.9.1 software. We then removed barcodes and primer sequences to obtain raw reads. Subsequently, the read sequences were compared with the species annotation database to detect chimeric sequences, which were removed to obtain pure sequences. The pure sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity using UPARSE V7.0 software. Then, the sequences with the highest frequency of occurrence in the OTUs were filtered according to the principles of this algorithm as the representative sequences. Species annotation analysis was performed using the Mothur method with the SILVA132 SSU rRNA database (threshold set at 0.8–1). Taxonomic composition was summarized at various levels, including kingdom, phylum, order, family, genus, and species. All data were normalized to ensure comparability among samples.

Blood sample collection and metabolomic analysis

Immediately following rumen fluid collection, blood samples were obtained intravenously (n = 6 per group). Approximately 10 mL of blood was collected from each sheep. The samples were centrifuged at 4,000 r/min for 3 min, and the resulting serum was harvested and stored at − 80 ℃ for subsequent metabolomic analysis.

Serum metabolomic profiling was conducted using a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS) platform. The frozen serum (1 mL) was thawed completely on ice. All sample handling steps were carried out on ice to maintain metabolite stability. After vortexing for 10 s, 50 µL of serum was pipetted into a centrifuge tube, and 300 µL of 20% acetonitrile-methanol internal standard was added. The mixture was vortexed for 3 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 r/min at 4 ℃. Subsequently, 200 µL of the supernatant was transferred into another centrifuge tube and allowed to stand at − 20 ℃ for 30 min. The sample was then centrifuged again at 12,000 r/min for 3 min at 4 ℃, and 180 mL of the final supernatant was pipetted into an autosampler vial for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Metabolite identification and quantification were carried out on a Waters Acquity UPLC Hss T3 C18 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm). Chromatographic separation was performed at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min and a column temperature of 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of ultrapure water containing 0.1% formic acid (phase A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (phase B). The elution gradient was programmed as follows: 0 min, 95:5 (A: B; v/v); 11.0 min, 10:90; 12.0 min, 10:90; 12.1 min, 95:5; and 14.0 min, 95:5.

The electrospray ion (ESI) source temperature was set at 500 °C, the mass spectrometry voltages were 5,500 V (positive mode) and − 4,500 V (negative mode), the ion source gas I was set to 55 psi and the curtain gas to 25 psi, and the collision-induced ionization parameter was set to high. In the triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, each ion pair was scanned for detection using optimized de-clustering voltages and collision energies. Qualitative analysis was conducted using a self-constructed targeted metabolite database (MWDB, Metware Database), based on retention time, precursor–product ion pair information, and the secondary mass spectral data.

Data analysis and visualization

Raw data were initially organized using Microsoft Excel 2016 and subsequently analyzed using SPSS 20.0. Differences in growth performance and rumen fermentation parameters were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by multiple comparisons using Duncan’s test.

Analysis of 16 S rRNA gene sequences was performed using the Novogene Cloud platform (https://magic.novogene.com/). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was conducted based on weighted UniFrac distances, and the combination of principal coordinates with the highest explanatory value was selected for graphical presentation. PCoA was analyzed using the R software packages weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA), stats and ggplot2.

Metabolomic data were analyzed using SIMCA 14.1. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was employed to identify potential biomarkers associated with metabolic differences between groups. Model quality was evaluated using R2Y (cum) (goodness of fit) and Q2 (cum) (predictive goodness of fit) [26]. Additionally, 200 permutation tests were performed to minimize overfitting and reduce the risk of false-positive results. Metabolites were considered significantly different when the variable importance in projection (VIP) was > 1, fold change (FC) > 2 or < 0.5, and P < 0.05.

Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed metabolites was conducted using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database via https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/. Correlations and significance between differentially abundant microorganisms, growth performance, rumen fermentation parameters, and differentially expressed metabolites were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation in R (V 4.0.2). Correlations were considered significant when the Spearman correlation coefficient (R) was > |0.5| and the P value was < 0.05.

Results

Growth performance

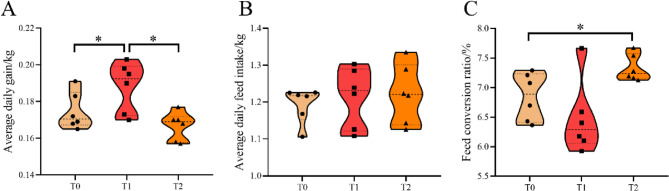

The ADG was significantly higher in the T1 group compared to the control group (T0), while no significant difference was observed between T2 and T0. In contrast, FCR were significantly higher in the T2 group than in the T0 group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of Sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion in the diet on growth performance of Hu sheep (n = 6). A Average daily gain; B Average daily feed intake; C Feed conversion ratio. T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage. T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS. T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

Rumen fermentation parameters

The concentration of NH3-N was greater in group T1 compared to the T0 and T2 groups (P < 0.05). Total volatile fatty acid (TVFA) concentration was lower in the T2 group than in the T0 group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of including sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) in the diet on rumen fermentation parameters of Hu sheep

| Items1 | Treatment groups2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | ||

| pH | 6.26 ± 0.17 | 6.20 ± 0.13 | 6.08 ± 0.86 | 0.866 |

| MCP (mg/dL) | 7.23 ± 0.31 | 7.36 ± 0.48 | 7.23 ± 0.74 | 0.690 |

| NH3-N (mg/dL) | 3.01 ± 0.69b | 3.84 ± 0.46a | 2.97 ± 0.61b | 0.037 |

| TVFA (mmol/L) | 100.94 ± 12.49a | 89.51 ± 4.51 | 84.43 ± 4.85b | 0.017 |

| Acetate (%) | 72.42 ± 9.12 | 67.55 ± 2.39 | 62.89 ± 3.33 | 0.060 |

| Propionate (%) | 25.31 ± 2.77 | 23.14 ± 1.77 | 22.13 ± 2.48 | 0.131 |

| Butyrate (%) | 18.82 ± 2.21 | 15.08 ± 1.38 | 15.48 ± 3.28 | 0.053 |

| A/P | 2.86 ± 0.20 | 2.93 ± 0.18 | 2.89 ± 0.43 | 0.933 |

1MCP, Microbial protein; TVFA, Total volatile fatty acids; A/P, Acetate-to-propionate ratio

2T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage

T1: 50% of WS was replaced with sorghum-sudangrass silage (SS)

T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

abMeans within a row with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.05)

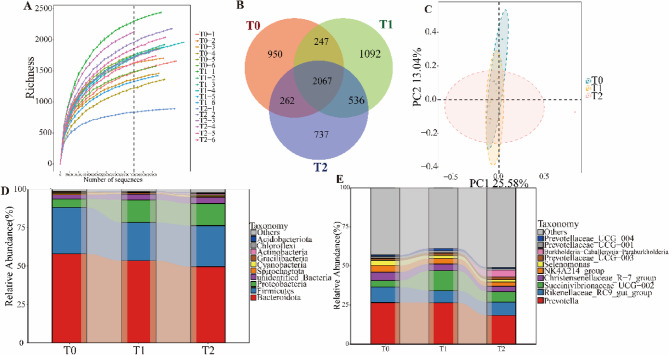

Rumen microbial community structure

Illumina sequencing of 18 rumen fluid samples yielded a total of 1,529,044 raw reads, from which 1,519,739 high-quality sequences were obtained after shear-filtering and quality control, resulting in an effective quality control rate of 99.39%. The rarefaction curve gradually plateaued, indicating that increasing sequencing depth would not detect additional OTUs, thus confirming the reliability of the sequencing data (Fig. 2A). At a 97% sequence similarity threshold, 4,846 OTUs were identified. Among them, 2,067 OTUs were shared across all groups, while 950, 1,092, and 737 unique OTUs were identified in the T0, T1, and T2 groups, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Composition of rumen microbiota in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of Sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion (n = 6). A Rarefaction (dilution) curve; B Venn diagram of ruminal bacterial OTUs; C PCoA plot illustrating the separation of rumen microbial communities based on the weighted UniFrac dissimilarity matrix; D Relative abundance of the top ten bacterial phyla; E Relative abundance of the top 10 bacterial genera. T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage. T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS. T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

Alpha diversity analysis showed no significant differences (P > 0.05) in ACE, Chao1, Simpson, and Shannon indices among the three dietary groups (Fig. S1). The PCoA results based on weighted UniFrac dissimilarity matrix revealed partial clustering of rumen microbial communities by dietary group, with PCoA1 and PCoA2 explaining 52.5% and 20.2% of the variation, respectively (Fig. 2C).

At the phylum level, Bacteroidota and Firmicutes were dominant across all samples (Fig. 2D). At the genus level, Prevotella was the most abundant genus (Fig. 2E). To further explore microbial differences between groups, LEfSe analysis was performed (Fig. 3). The distribution of differentially abundant taxa among the T0, T1 and T2 groups is shown in Fig. 3A. At the phylum level, Acidobacteriota and Myxococcota were more abundant in the T1 group (LDA > 2.5), while Actinobacteria was more abundant in the T2 group (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, LEfSe analysis also indicated that Acidobacteria were more enriched in the T2 group (LDA > 2.5).

Fig. 3.

Differential enrichment of rumen microbial taxa in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion (n = 6). A Dendrogram showing differences in the enrichment of microbial taxa among the three treatment groups; B Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores of rumen microbial OTUs. T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage. T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS. T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

At the genus level, Sphingomonas, Bacillus, Succinimonas, Pantoea, Enterococcus, unidentified_Gemmatimonadaceae, Bryobacter, Ruminobacter, and Ruminococcus differed between groups T1 and T2 (Fig. 3B). Among them, Sphingomonas was enriched in the T1 group, while the remaining genus were representative of the T2 group (Fig. 3B).

Serum metabolomics

Sample quality control

During metabolite detection, total ion current chromatograms of quality control samples showed high overlap with consistent retention times and peak intensities, indicating stable and reliable signal detection throughout the analysis (Fig. S2).

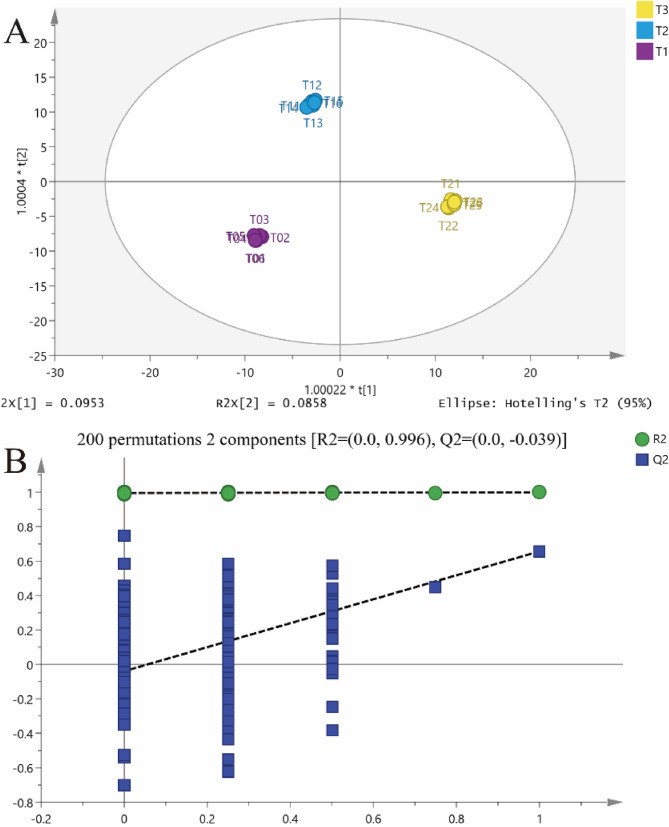

Multivariate statistical analysis

To explore the contribution of SS to group differentiation, OPLS-DA was employed to identify distinct metabolic patterns among dietary treatments. Clear separation between groups was observed in the OPLS-DA score plots for each comparison (T0 vs. T1, T0 vs. T2, and T1 vs. T2) (Fig. 4A). The validity of the OPLS-DA model was confirmed through 200 permutation tests, with all R²Y values exceeding 0.98, indicating excellent model fit and predictive power for subsequent variance analysis (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Multivariate statistical analysis of serum metabolites in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion (n = 6). A OPLS-DA score plots showing separation among the three treatment groups; B Corresponding OPLS-DA validation plots for the same groups. T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage. T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS. T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

Differentially expressed metabolites

Volcano plots were used to visualize differentially expressed metabolites across group comparisons (Fig. 5), with grey dots indicating no significant changes, red dots indicating up-regulation, and blue dots indicating down-regulation. A total of 29 differentially expressed metabolites were identified between T0 and T1, including 17 down-regulated metabolites and 12 up-regulated metabolites.

Fig. 5.

Volcano plots of differentially expressed metabolites in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion. Grey dots indicate non-significant metabolites; red dots indicate up-regulated metabolites; blue dots indicate down-regulated metabolites. T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage. T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS. T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS. A Comparison between T0 and T1; B Comparison between T0 and T2; C Comparison between T1 and T2

Between T0 and T2, 22 differentially expressed metabolites were detected (13 down-regulated and 9 up-regulated), while 25 were identified between T1 and T2 (17 down-regulated and 8 up-regulated). There were 22 differentially expressed metabolites in any two of the three comparisons (T0 vs. T1, T0 vs. T2 and T1 vs. T2) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differentially expressed metabolites identified in pairwise comparisons among the three treatment groups

| Metabolites | Treatment group1 | VIP2 | P | FC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethylamine N-oxide | T0 vs. T1 | 1.545 | 0.025 | 2.675 |

| T2 vs. T3 | 1.62 | 0.013 | 3.542 | |

| Securinine | T0 vs. T3 | 1.774 | < 0.001 | 2.523 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 2.058 | < 0.001 | 0.340 | |

| L-tyrosine methyl ester 4-sulfate | T0 vs. T3 | 1.682 | 0.001 | 0.277 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.813 | 0.003 | 2.550 | |

| N-Acetyl-L-tryptophan | T0 vs. T3 | 1.901 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.663 | 0.009 | 12954.800 | |

| 3-aminobenzamide | T0 vs. T3 | 1.795 | < 0.001 | 0.425 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.813 | 0.002 | 4.127 | |

| 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide | T0 vs. T1 | 1.415 | 0.041 | 0.363 |

| T0 vs. T3 | 1.566 | 0.005 | 0.118 | |

| Pyrazine | T0 vs. T3 | 1.865 | < 0.001 | 2.849 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 2.137 | < 0.001 | 0.352 | |

| Indole-2-carboxylic acid | T0 vs. T1 | 1.413 | 0.030 | 0.423 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.866 | 0.004 | 0.478 | |

| Indole-3-carboxaldehyde | T0 vs. T1 | 1.370 | 0.041 | 0.409 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.973 | 0.002 | 0.397 | |

| 5-Methylcytosine | T0 vs. T1 | 1.490 | 0.039 | 7.640 |

| T0 vs. T3 | 1.469 | 0.010 | 2.574 | |

| Adenosine | T0 vs. T1 | 1.446 | 0.049 | 2.895 |

| T0 vs. T3 | 1.423 | 0.013 | 2.492 | |

| 2-Phenylpropionic acid | T0 vs. T3 | 1.683 | 0.001 | 0.287 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.751 | 0.003 | 2.428 | |

| Argininosuccinic acid | T0 vs. T3 | 1.852 | < 0.001 | 2.957 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 2.126 | < 0.001 | 0.465 | |

| Leu-Trp | T0 vs. T1 | 1.599 | 0.016 | 5.845 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.397 | 0.043 | 3.348 | |

| Hyp-Ile | T0 vs. T1 | 1.584 | 0.009 | 0.379 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.428 | 0.034 | 0.469 | |

| Val-Tyr | T0 vs. T1 | 1.488 | 0.040 | 21.381 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.369 | 0.048 | 10.836 | |

| Cyclo (gly-pro) | T0 vs. T1 | 1.483 | 0.041 | 8.330 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.416 | 0.038 | 9.684 | |

| Ile-Trp | T0 vs. T3 | 1.296 | 0.028 | 0.197 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.457 | 0.033 | 7.005 | |

| D-Turanose | T0 vs. T3 | 1.627 | 0.002 | 0.149 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.506 | 0.028 | 4.052 | |

| PE (16:0/20:4) | T0 vs. T3 | 1.578 | 0.009 | 2.896 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.813 | 0.009 | 0.347 | |

| 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate | T0 vs. T3 | 1.683 | 0.001 | 0.287 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.751 | 0.003 | 2.428 | |

| Acetaminophen | T0 vs. T3 | 1.709 | 0.001 | 0.276 |

| T1 vs. T3 | 1.751 | 0.003 | 2.506 |

1T0: Diet contained whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage

T1: 50% of WS was replaced with sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS)

T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS

2VIP, Variable importance in the projection

3FC, Fold Change

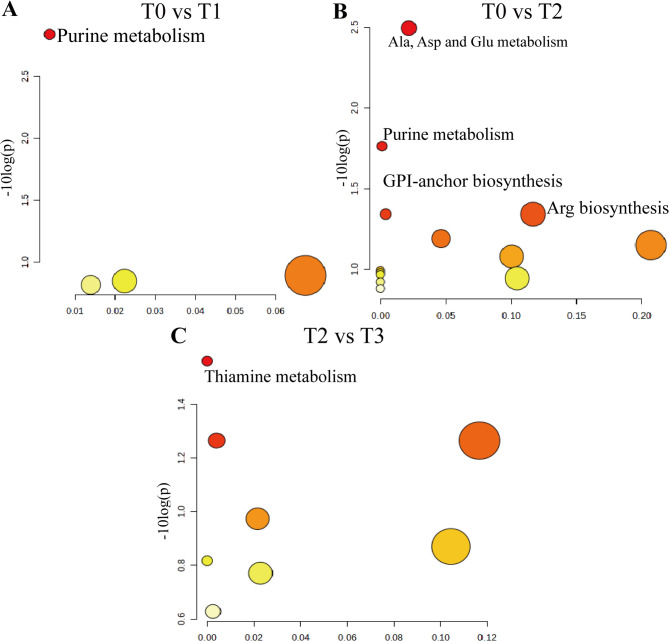

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that replacing WS with SS significantly altered five metabolic pathways, namely purine metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis, arginine biosynthesis, and thiamine metabolism (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

KEGG-enriched metabolic pathways in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion. A T0 group vs T1 group. B T0 group vs T2 group. C T1 group vs T2 group. Bubble position and size along the horizontal axis represent the impact factor of each pathway from topological analysis. The larger the bubble, the greater the impact. Bubble position and color along the vertical axis represent the significance of enrichment analysis (-lnP value). The smaller the P value, the darker the color, indicating higher significance. GPI: Glycosylphosphatidylinositol; Ala: Alanine; Asp: Asparagine; Glu: Glutamate

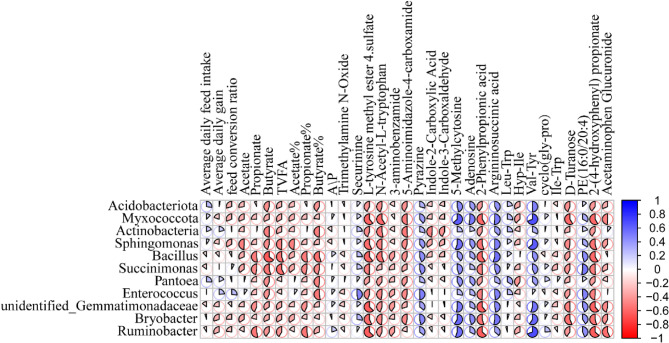

Fig. 7.

Heatmap of Spearman’s correlation analysis between rumen bacterial genera and differentially expressed metabolites in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion. Color values indicate correlation direction: values above zero represent positive correlations, and values below zero represent negative correlations. Within each square, a pie chart illustrates the strength of the correlation. The larger the pie chart, the stronger the correlation; the smaller the pie chart, the weaker the correlation

Correlation analysis of rumen microorganisms, growth performance, rumen fermentation parameters, and blood differentially expressed metabolites

Myxococcota was positively correlated with 5-methylcytosine, adenosine, argininosuccinic acid, and Val-Tyr, and negatively correlated L-tyrosine methyl ester 4-sulfate, N-Acetyl-L-tryptophan, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide, 2-phenylpropionic acid, 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate (Fig. 7). Actinobacteria showed negative correlations with N-acetyl-L-tryptophan and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (P < 0.05). Sphingomonas was positively correlated with argininosuccinic acid, 5-methylcytosine, and Val-Tyr, and negatively correlated with L-tyrosine-methyl ester 4-sulfate, 2-phenylpropionic acid, and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate (P < 0.05). Bacillus was negatively correlated with propionate, butyrate, TVFA, propionate%, butyrate%, L-tyrosine methyl ester 4-sulfate, N-acetyl-L-tryptophan, 2-phenylpropionic acid, and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate, but positively correlated with argininosuccinic acid (P < 0.05). Succinimonas showed negative correlations with butyrate, TVFA, 2-phenylpropionic acid, and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate, and a positive correlation with PE (16:0/20:4) (P < 0.05). Enterococcus was negatively and significantly correlated with butyrate% (P < 0.05). Unidentified_Gemmatimonadaceae and Bryobacter were negatively correlated with L-tyrosine methyl ester 4-sulfate, 2-phenylpropionic acid, D-turanose, and 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate, and positively correlated with Val-Tyr and 5-Methylcytosine (P < 0.05). Ruminobacter was negatively associated with propionate, propionate%, L-tyrosine methyl ester 4-sulfate, 2-phenylpropionic acid, 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate, and acetaminophen glucuronide, but positively correlated with 5-methylcytosine and Val-Tyr (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, replacing half of WS with SS in the diet of Hu sheep for 30 d significantly increased ADG, which may be attributed to a synergistic effect between SS and WS. It is worth noting that complete replacement of WS with SS led to a reduction in FCR, probably due to the lower digestibility coefficients of SS nutrients (such as dry matter, nitrogen-free extract, and crude protein) compared with WS [27].

Rumen pH plays a critical role in microbial activity and fermentation efficiency. Previous studies have reported that rumen pH is in the range of 5.5 to 6.5 when animals are fed high-quality pasture [28–30]. In this study, rumen pH ranged from 6.08 to 6.26 across all groups, with no significant differences, indicating that SS inclusion did not adversely affect rumen pH homeostasis.

The concentration of NH3-N reflects the degradation of nitrogenous substances in the diet and the utilization of ammonia by rumen microbes for MCP synthesis [31]. In this study, NH3-N concentration was highest in the T1 group, suggesting enhanced microbial activity and potentially greater MCP synthesis. Volatile fatty acids, produced via microbial fermentation of carbohydrates, provide essential energy for ruminant metabolism [31]. In this study, our findings showed that TVFA concentrations were significantly lower in the T2 group compared to the T0 group, indicating that complete replacement with SS may not support VFA production as effectively as WS. However, partial replacement (T1) appeared to support favorable VFA synthesis and microbial energy metabolism.

The core rumen microbiota is generally stable and not markedly influenced by dietary fiber sources [32, 33]. Consistent with previous reports [34], the dominant phyla identified in this study were Firmicutes and Bacteroidota, with Prevotella as the predominant genus. Bacteroidota are primarily involved in protein and carbohydrate degradation, while Firmicutes are associated with energy metabolism [35, 36]. These two phyla play key roles in host physiology, immunity, and nutrient absorption [37, 38]. In this study, SS inclusion did not alter the overall phylum-level structure of the rumen microbiota, and Prevotella remained dominant. Prevotella, a genus within Bacteroidota [39, 40], is vital in the digestion and utilization of starch, xylan, and pectin, and its abundance is influenced by dietary crude protein, starch, NDF, ADF, and the forage-to-concentrate ratio [41–43].

Our results showed that the relative abundance of Sphingomonas, a gram-negative, strictly aerobic bacterium [44], was significantly higher in the T1 group compared to the control group. Sphingomonas is known to degrade a range of polysaccharides, including cellulose [45, 46], and is widely used in aquaculture for its antagonistic effects against pathogens [47]. This suggests that 50% SS inclusion may enhance fiber degradation due to increased abundance of Sphingomonas.

The relative abundance of Bacillus, Enterococcus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Ruminobacter was significantly increased by the complete replacement of WS with SS. Bacillus is a genus of gram-positive, aerobic or partially anaerobic, endophytic spore-forming bacteria that contributes to improved animal growth performance, immune function, and gut development, and regulates the gut microbial community [48, 49]. Zhang et al. [50] showed that Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus pumilus could increase the abundance of beneficial bacteria and decrease the abundance of pathogenic bacteria in the rumen and cecum and thus facilitate nutrient metabolism and promote health status. Enterococcus is a parthenogenetic anaerobic bacterium that is capable of producing beneficial enzymes [51], vitamin B12 [52], and antimicrobial compounds such as enterococci [53, 54], and can inhibit pathogens [55, 56]. Ruminobacter is associated with the fermentation of starch and has an important role in ruminal protein digestion [57]. Enterococcus faecalis, a gram-positive bacterium, is a common inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract, and its supplementation has been shown to enhance microbial growth and feed efficiency in ruminants [58].

To further investigate SS-induced changes in host metabolism, we performed LC-MS-based metabolomic analysis. OPLS-DA clearly differentiated the metabolic profiles of T0, T1 and T2 groups, indicating that SS inclusion altered systemic metabolism. Notably, trimethylamine N-oxide levels decreased with increasing SS inclusion. Trimethylamine N-oxide can be produced through the metabolism of choline, betaine, lecithin and carnitine by gut microbes and continues to accumulate in high concentrations in marine animal tissues [59]. Trimethylamine N-oxide is considered to be a pro-atherosclerotic substance and is associated with cardiovascular risk [60–62].

Moreover, 50% SS inclusion increased serum N-acetyl-L-tryptophan, an amino acid derivative mainly absorbed in the small intestine [63]. Previous studies have shown that the dietary supplementation of N-acetyl-L-tryptophan improves nitrogen utilization and growth performance in lambs and cashmere goats [64, 65].

The concentrations of indole derivatives, including indole-2-carboxylic acid and indole-3-carboxaldehyde, decreased with the increase in SS inclusion. Indole and its derivatives are converted from tryptophan in the presence of intestinal microbiota and have a wide range of biological functions [66]. Indole-2-carboxylic acid has cholesterol-lowering effects [67]. Indole-3-carboxaldehyde not only has anti-inflammatory effects but also regulates immune system homeostasis by reducing the secretion of IFN-α and inflammatory cytokines [68]. Dietary indole-3-carboxaldehyde supplementation has been shown to reduce FCR and improve gut health in piglets [69], suggesting that excessive SS may limit beneficial indole production.

Additionally, the diet including SS enhanced purine metabolism, as indicated by increased levels of 5-methylcytosine and adenosine, which are key intermediates in cellular energy transfer and DNA synthesis [70]. This shift may explain the growth-promoting effect observed with 50% SS inclusion [71].

Conclusion

In this study, we found that SS replacing 50% of WS increased ADG and NH3-N concentration in the rumen of Hu sheep. The addition of SS did not alter the dominant microbiota at the rumen portal level (Firmicutes and Bacteroidota) and at the genus level (Prevotella) in Hu sheep. In addition, the replacement of 50% of WS by SS increased the relative abundance of Sphingomonas and up-regulated purine metabolism.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Alpha diversity indices of rumen microbiota in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion. (A) Shannon index; (B) Chao1 index; (C) Simpson index; (D) ACE index. T0: Diet containing whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage; T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS; T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS. Figure S2. Total ionic current (TIC) profiles in quality control (QC) serum samples. The horizontal axis represents the retention time (min) in the metabolite assay, and the vertical axis shows ion current intensity (cps: counts per second).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the Tumxuk City Ten Thousand Sheep Farming Cooperative for generously providing the experimental site.

Abbreviations

- ADF

Acid detergent fiber

- ADG

Average daily gain

- DMI

Dry matter intake

- ESI

Electrospray ion source

- FCR

Feed conversion ratio

- FC

Fold change

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- LDA

Linear Discriminant Analysis

- LEfSe

LDA effect size

- MCP

Microbial protein

- NDF

Neutral detergent fiber

- NH3-N

Ammonia nitrogen

- OTUs

Operational taxonomic units

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis

- PCoA

Principal coordinates analysis

- SS

Sorghum-sudangrass silage

- TVFA

Total volatile fatty acid

- VFA

Volatile fatty acid

- WS

Whole-plant corn silage

Authors’ contributions

C.L: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Z.C: validation. X. S: writing—review and editing. J.Y: resources. N.C: supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. K.Y, project administration, funding acquisition. M.W: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of the 14th Five-Year Plan (Grant Nos. 2023YFD1301705 and 2021YFD1600702) and the Key Program of the State Key Laboratory of Sheep Genetic Improvement and Healthy Production (Grant No. NCG202232).

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: PRJNA1103727), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1103727.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals issued by the Scientific Research Department of Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural and Reclamation Sciences (protocol approval number: XJNKKXYAEP-038). This study did not involve any endangered or protected animal species. Individual oral/written informed consent was obtained from all animal owners for the use of samples, and written consent was also obtained for the participation of their animals in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chuang Li and Zhiqiang Cheng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ning Chen, Email: ningningkuaile@126.com.

Kailun Yang, Email: ykl@xjau.edu.cn.

Mengzhi Wang, Email: mzwang@yzu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Dann H, Grant R, Cotanch K, Thomas E, Ballard C, Rice R. Comparison of brown midrib sorghum-sudangrass with corn silage on lactational performance and nutrient digestibility in Holstein dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91(2):663–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cattani M, Guzzo N, Mantovani R, Bailoni L. Effects of total replacement of corn silage with sorghum silage on milk yield, composition, and quality. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2017;8(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu XX, Liu ZH, Yu Z, Shi Y, Li XY. Development of SSR markers linked to low hydrocyanic acid content in sorghum-sudan grass hybrid based on BSA method. Protein Pept Lett. 2016;23(5):417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes CM, Weers BD, Thakran M, Burow G, Xin Z, Emendack Y, et al. Discovery of a Dhurrin QTL in sorghum: co-localization of Dhurrin biosynthesis and a novel Stay‐green QTL. Crop Sci. 2016;56(1):104–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.You SH, Du S, Ge GT, Wan T, Jia YS. Selection of lactic acid bacteria from native grass silage and its effects as inoculant on silage fermentation. Agron J. 2021;113(4):3169–77. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilcer T, Ketterings Q, Cerosaletti P, Cherney J, Barney P, Hunter M, et al. Successfully growing brown midrib sorghum-sudan for dairy cows in the northeast. 2001. Available at: http://www.cce.cornell.edu/rensselaer/agriculture. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- 7.Sawal R, Sharma K. Nutritive evaluation of Sorghum Sudan grass hay alone and in combination with cowpea hay in sheep. Indian J Anim Nutr. 2009;26(4):333–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farré I, Faci JM. Comparative response of maize (Zea mays L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) to deficit irrigation in a mediterranean environment. Agric Water Manage. 2006;83(1–2):135–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonulal E. Performance of sorghum× Sudan grass hybrid (Sorghum bicolor L.× Sorhgum Sudanense) cultivars under water stress conditions of arid and semi-arid regions. J Glob Innov Agric Soc Sci. 2020;8(2):78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes R, Miller D, Nelson C. Forages 1: an introduction to grassland agriculture fifth edition. Iowa State Univ Press. 1995;9:369. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pahlow G, Muck RE, Driehuis F, Elferink SJO, Spoelstra SF. Microbiology of ensiling. Silage Sci Technol. 2003;42:31–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kung L Jr., Shaver R, Grant R, Schmidt R. Silage review: interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(5):4020–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller C, Udén P. Preference of horses for grass conserved as hay, haylage or silage. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2007;132(1–2):66–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong Z, Li J, Wang S, Dong D, Shao T. Time of day for harvest affects the fermentation parameters, bacterial community, and metabolic characteristics of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid silage. Msphere. 2022;7(4):e00168–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kır H, Şahan BD. Yield and quality feature of some silage sorghum and sorghum-sudangrass hybrid cultivars in ecological conditions of Kırşehir province. Türk Tarım ve Doğa Bilimleri Dergisi. 2019;6(3):388–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gul I, Demirel R, Kilicalp N, Sumerli M, Kilic H. Effect of crop maturity stages on yield, silage chemical composition and in vivo digestibilities of the maize, sorghum and sorghum-sudangrass hybrids grown in semi-arid conditions. J Anim Vet Adv. 2008;7(8):1021–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliver A, Grant R, Pedersen J, O’rear J. Comparison of brown midrib-6 and-18 forage sorghum with conventional sorghum and corn silage in diets of lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2004;87(3):637–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, Li C, Chen Y, Liu J, Zhang C, Irving B, et al. Host genetics influence the rumen microbiota and heritable rumen microbial features associate with feed efficiency in cattle. Microbiome. 2019;7:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, Xie F, Sun D, Liu J, Zhu W, Mao S. Ruminal microbiome-host crosstalk stimulates the development of the ruminal epithelium in a lamb model. Microbiome. 2019;7:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chemists AOA, Cunniff P. Official methods of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Washington, DC.: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 1990.

- 21.Van Soest Pv, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74(10):3583–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ANKOM Technology. Method 6: Neutral Detergent Fiber in Feeds—Filter Bag Technique (for A200 and A200I). Available online: https://www.ankom.com/sites/default/files/document-files/Method_6_NDF_A200.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2021.

- 23.Wang H, Chen Q, Chen L, Ge R, Wang M, Yu L, et al. Effects of dietary physically effective neutral detergent fiber content on the feeding behavior, digestibility, and growth of 8-to 10-month-old Holstein replacement heifers. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100(2):1161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Wang S, Wang M, Shahzad K, Zhang X, Qi R, et al. Effects of Urtica cannabina to Leymus chinensis ratios on ruminal microorganisms and fiber degradation in vitro. Animals. 2020;10(2): 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weatherburn M. Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal Chem. 1967;39(8):971–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Wu Z, Li S, Yang M, Xiao X, Lian C, et al. Targeted blood metabolomic study on retinopathy of prematurity. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(2):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher L. Evaluation of corn and sorghum-sudan silages on the basis of dry matter intake, digestibility and milk production. Can J Anim Sci. 1968;48(3):431–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Vuuren A, Van Der Koelen C, Valk H, De Visser H. Effects of partial replacement of ryegrass by low protein feeds on rumen fermentation and nitrogen loss by dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76(10):2982–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockdale C. Persian clover and maize silage. III. Rumen fermentation and balance of nutrients when clover and silage are fed to lactating dairy cows. Aust J Agric Res. 1994;45(8):1783–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolver E, Muller L, Barry M, Penno J. Evaluation and application of the Cornell net carbohydrate and protein system for dairy cows fed diets based on pasture. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81(7):2029–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, Li X, Zhang L, Wu J, Zhao S, Jiao T. Effect of oregano oil and cobalt lactate on sheep in vitro digestibility, fermentation characteristics and rumen microbial community. Animals. 2022;12(1): 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petri R, Forster R, Yang W, McKinnon J, McAllister T. Characterization of rumen bacterial diversity and fermentation parameters in concentrate fed cattle with and without forage. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;112(6):1152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson G, Cox F, Ganesh S, Jonker A, Young W, Janssen PH. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh K, Jakhesara S, Koringa P, Rank D, Joshi C. Metagenomic analysis of virulence-associated and antibiotic resistance genes of microbes in rumen of Indian Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Gene. 2012;507(2):146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen Y-Y, Keilbaugh SA, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y-B, Lan D-L, Tang C, Yang X-N, Li J. Effect of DNA extraction methods on the apparent structure of Yak rumen microbial communities as revealed by 16S rDNA sequencing. Pol J Microbiol. 2015;64(1):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tilg H, Kaser A. Gut microbiome, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(6):2126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148(6):1258–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunha IS, Barreto CC, Costa OY, Bomfim MA, Castro AP, Kruger RH, et al. Bacteria and Archaea community structure in the rumen microbiome of goats (Capra hircus) from the semiarid region of Brazil. Anaerobe. 2011;17(3):118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang J, Yao X, Zuo C, Qi Y, Chen D, Ma W. The gut bacterial diversity of sheep associated with different breeds in Qinghai Province. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellison M, Conant G, Lamberson W, Cockrum R, Austin K, Rule D, et al. Diet and feed efficiency status affect rumen microbial profiles of sheep. Small Ruminant Res. 2017;156:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Granja-Salcedo YT, Ribeiro Junior CS, de Jesus RB, Gomez-Insuasti AS, Rivera AR, Messana JD, et al. Effect of different levels of concentrate on ruminal microorganisms and rumen fermentation in Nellore steers. Arch Anim Nutr. 2016;70(1):17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mao S, Zhang R, Wang D, Zhu W. The diversity of the fecal bacterial community and its relationship with the concentration of volatile fatty acids in the feces during subacute rumen acidosis in dairy cows. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White DC, Sutton SD, Ringelberg DB. The genus Sphingomonas: physiology and ecology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7(3):301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Birkholz AM, Kronenberg M. Antigen specificity of invariant natural killer T-cells. Biomedical J. 2015;38(6):470–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui Z, Wu S, Liu S, Sun L, Feng Y, Cao Y, et al. From maternal grazing to barn feeding during pre-weaning period: altered Gastrointestinal microbiota contributes to change the development and function of the rumen and intestine of Yak calves. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asma C, Qazi JI. Probiotic antagonism of Sphingomonas sp. against Vibrio anguillarum exposed Labeo rohita fingerlings. Adv Life Sci. 2014;4(3):156–65. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lan R, Kim IH. Effects of Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis complex on growth performance and faecal noxious gas emissions in growing-finishing pigs. J Sci Food Agr. 2019;99(4):1554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luan S, Duersteler M, Galbraith E, Cardoso F. Effects of direct-fed Bacillus pumilus 8G-134 on feed intake, milk yield, milk composition, feed conversion, and health condition of pre-and postpartum Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98(9):6423–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang N, Wang L, Wei Y. Effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus pumilus on rumen and intestine morphology and microbiota in weanling Jintang black goat. Animals. 2020;10(9): 1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarantinopoulos P, Andrighetto C, Georgalaki MD, Rea MC, Lombardi A, Cogan TM, et al. Biochemical properties of enterococci relevant to their technological performance. Int Dairy J. 2001;11(8):621–47. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li P, Gu Q, Wang Y, Yu Y, Yang L, Chen JV. Novel vitamin B 12-producing Enterococcus spp. And preliminary in vitro evaluation of probiotic potentials. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:6155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang E, Fan L, Jiang Y, Doucette C, Fillmore S. Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from cheeses and yogurts. Amb Express. 2012;2(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang E, Fan L, Yan J, Jiang Y, Doucette C, Fillmore S, et al. Influence of culture media, pH and temperature on growth and bacteriocin production of bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria. AMB Express. 2018;8(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arena MP, Capozzi V, Russo P, Drider D, Spano G, Fiocco D. Immunobiosis and probiosis: antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria with a focus on their antiviral and antifungal properties. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:9949–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mansour NM, Elkhatib WF, Aboshanab KM, Bahr MM. Inhibition of Clostridium difficile in mice using a mixture of potential probiotic strains Enterococcus faecalis NM815, E. faecalis NM915, and E. faecium NM1015: novel candidates to control C. difficile infection (CDI). Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2018;10:511–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong J-N, Li S-Z, Chen X, Qin G-X, Wang T, Sun Z, et al. Effects of different combinations of sugar and starch concentrations on ruminal fermentation and bacterial-community composition in vitro. Front Nutr. 2021;8: 727714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maake TW, Aiyegoro OA, Adeleke MA. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Enterococcus faecalis supplementation as direct-fed microbials on rumen microbiota of Boer and speckled goat breeds. Veterinary Sci. 2021;8(6):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Velasquez MT, Ramezani A, Manal A, Raj DS. Trimethylamine N-oxide: the good, the bad and the unknown. Toxins. 2016;8(11): 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, DuGar B, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Servillo L, D’Onofrio N, Giovane A, Casale R, Cautela D, Ferrari G, et al. The betaine profile of cereal flours unveils new and uncommon betaines. Food Chem. 2018;239:234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zeisel SH, Warrier M. Trimethylamine N-oxide, the microbiome, and heart and kidney disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017;37:157–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee S-B, Lee K-W, Wang T, Lee J-S, Jung U-S, Nejad JG, et al. Administration of encapsulated L-tryptophan improves duodenal starch digestion and increases Gastrointestinal hormones secretions in beef cattle. Asian Austral J Anim. 2020;33(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma H, Cheng J, Zhu X, Jia Z. Effects of rumen-protected tryptophan on performance, nutrient utilization and plasma tryptophan in cashmere goats. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10(30):5806–11. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van E, Nolte J, Loest C, Ferreira A, Waggoner J, Mathis C. Limiting amino acids for growing lambs fed a diet low in ruminally undegradable protein. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(10):2627–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang B, Wan Y, Zhou X, Zhang H, Zhao H, Ma L, et al. Characteristics of serum metabolites and gut microbiota in diabetic kidney disease. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:872988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kariya T, Grisar JM, Wiech NL, Blohm TR. Hypocholesterolemic indole-2-carboxylic acids. J Med Chem. 1972;15(6):659–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hou X, Zhang X, Bi J, Zhu A, He L. Indole-3-carboxaldehyde regulates RSV-induced inflammatory response in RAW264. 7 cells by moderate Inhibition of the TLR7 signaling pathway. J Nat Med. 2021;75:602–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang R, Huang G, Ren Y, Wang H, Ye Y, Guo J, et al. Effects of dietary indole-3-carboxaldehyde supplementation on growth performance, intestinal epithelial function, and intestinal microbial composition in weaned piglets. Front Nutr. 2022;9: 896815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pedley AM, Benkovic SJ. A new view into the regulation of purine metabolism: the purinosome. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42(2):141–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palma M, Scanlon T, Kilminster T, Milton J, Oldham C, Greeff J, et al. The hepatic and skeletal muscle ovine metabolomes as affected by weight loss: a study in three sheep breeds using NMR-metabolomics. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):39120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Alpha diversity indices of rumen microbiota in Hu sheep fed diets with varying levels of sorghum–sudangrass silage (SS) inclusion. (A) Shannon index; (B) Chao1 index; (C) Simpson index; (D) ACE index. T0: Diet containing whole-plant corn silage (WS) and wheat straw as roughage; T1: 50% of WS was replaced with SS; T2: 100% of WS was replaced with SS. Figure S2. Total ionic current (TIC) profiles in quality control (QC) serum samples. The horizontal axis represents the retention time (min) in the metabolite assay, and the vertical axis shows ion current intensity (cps: counts per second).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: PRJNA1103727), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1103727.