Abstract

Background

Mental health is increasingly recognized worldwide as a significant public health challenge. However, progress in developing interventions to address mental health burdens, particularly in non-Western countries, has been remarkably slow. This stagnation may be attributed to limited research on the underlying causes of mental health issues, such as trauma, as well as a lack of awareness regarding mental health disorders and help-seeking behaviours. The current study seeks to mainstream the understanding of mental health disorders by investigating the impact of trauma awareness and mental health disorders on the variance in help-seeking behaviours for mental health in non-Western contexts. This exploration aims to enhance the discourse on mental health initiatives and inform strategies for promoting mental health awareness and access to care in these regions.

Methods

A total of 2472 young adults (n = 1871) and adolescents (n = 601) were recruited from four countries (Bangladesh, n = 487; Egypt, n = 1070; Ghana, n = 695; and UAE, n = 217) to participate in this study. They completed three survey scales, namely, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, the Individual Trauma Identification and Management Scale and the Attitude toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help. Using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 29 and the Andrew Hayes PROCESS Model version 4.0, the data were subjected to hierarchical multiple regression, moderation and mediation analyses.

Results

Both trauma and mental health disorders collectively served as predictors of access to mental health help-seeking behaviour. Furthermore, mental health help-seeking behaviour was identified as a mediating factor in the relationship between trauma and mental health disorders.

Conclusion

This study recommends the establishment of mental health and trauma awareness programs specifically aimed at young adults and adolescents across these four countries. Additionally, a comprehensive discussion of the study’s implications is provided in detail.

Keywords: Public health, Mental health, Help seeking, Youth, Bangladesh, Egypt, Ghana, United Arab Emirates

Highlights

Nonwestern contexts share a common understanding or perception of mental health disorders.

Comparative studies on mental health among adolescents and young adults are under-researched in a nonwestern context.

Studies on the relationships among awareness of trauma, mental health disorders and mental health-seeking behaviour are very rare.

Trauma awareness and mental health disorders are significant predictors of mental health help-seeking behaviours.

Raising awareness of trauma and mental health disorders could enhance mental health help-seeking behaviour.

Introduction

Mental health encompasses a comprehensive state of well-being that empowers individuals to navigate life challenges, realize their potential, engage in productive work, and contribute meaningfully to society [1]. This concept extends beyond the mere absence of mental illness; it also encompasses overall well-being and the capacity for thriving, which are influenced by various factors, including access to opportunities, supportive interpersonal relationships, and stable environmental conditions [2]. The WHO [1] reported that, in 2019, approximately one in eight individuals worldwide—approximately 970 million people—suffered from a mental disorder, with anxiety and depression identified as the most prevalent conditions. Furthermore, the emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 exacerbated this situation, resulting in a marked increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders, particularly depression and stress, which has increased by nearly 28% within a year [1]. Given that a substantial portion of the global population is at risk for mental health disorders, there is a burgeoning research focus on understanding the impact of these conditions on individual functioning, overall well-being, physical health, and productivity [3, 4].

Adolescents and young adults make up a quarter of the global population [5, 6]. In this study, adolescence refers to the developmental period for individuals aged 13–19 years, whereas young adults are defined as those aged 20–35 years [7]. This period is a critical and transformative phase of life [8]. Unfortunately, the global burden of mental health disorders is particularly high among adolescents and young adults. According to [9], approximately 254 million adolescents and young adults worldwide suffer from mental health disorders. In particular, the adolescent and young adult stages are characterized by hormonal and physical changes, shifts in social dynamics, and significant brain and cognitive development [8, 10]. This period is often described as one of heightened vulnerability to mental health issues due to various environmental factors, including poverty, peer pressure, substance abuse, and bullying [10]. The combination of physical, emotional, and social changes, especially when compounded by challenges such as poverty, abuse, or violence, can increase susceptibility to mental health problems [11–13]. Therefore, it is vital to support adolescents by reducing their exposure to adversity, promoting socioemotional learning, enhancing their psychological well-being, and ensuring access to mental health care to foster their development and long-term health [14].

The contemporary discourse surrounding mental health disorders is to promote help-seeking behaviour among adolescents and young adults, demographics that are particularly vulnerable yet frequently resistant to seeking assistance [15–18]. The key obstacles to help-seeking behaviours identified in the literature include pervasive stigma and negative societal attitudes toward mental health services, feelings of embarrassment, limited mental health literacy, unawareness of the need for professional intervention, and negative perceptions regarding mental health professionals, including skepticism about their effectiveness and concerns surrounding confidentiality [18–21]. Sociocultural factors also significantly influence help-seeking behaviour, with gender differences playing a notable role [22]. For example, research suggests that boys are more inclined to view seeking help as indicative of weakness than their female counterparts are [18]. Conversely, certain facilitators may mitigate these barriers, including prior positive interactions with mental health services, encouragement from supportive networks, and a sense of trust in professionals [18, 20].

The stigma associated with seeking assistance for mental health disorder is particularly pronounced in non-Western countries, where individuals with mental health disorders frequently encounter discrimination [22]. Many societies erroneously attribute mental health conditions to supernatural forces, resulting in widespread reluctance to associate with affected individuals [23, 24]. Despite a substantial population experiencing mental health disorders in nonwestern regions [25, 26], a considerable number remain undiagnosed [27, 28] [29, 30]. elucidated the detrimental impact of undiagnosed mental health disorders on productivity and the subsequent strain on national resources. Moreover, the relationships among mental health challenges, criminal behaviour, and suicide rates are notably concerning [31, 32], thus compelling governmental entities to establish institutional mechanisms aimed at alleviating the adverse effects associated with mental health disorders [33, 34].

Nonwestern countries share similarities in their perceptions and stigma related to mental health disorders [28, 35]. In this context, enhancing awareness regarding the etiology of mental health disorders and the available interventions is paramount. To allocate governmental resources effectively toward productive interventions, it is imperative to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing mental health mitigation and to promote help-seeking behaviour. However, there is a notable gap in empirical evidence concerning the interplay between awareness of mental health issues, their underlying causes, and the propensity for individuals to seek help. The overarching aim of this study was to investigate the interplay between mental health disorders, trauma, and help-seeking behaviour for mental health across different countries. The primary objective of this study was to examine how mental health disorders and trauma awareness contribute to variations in help-seeking behaviour. The findings of this study are promising, as they have the potential to inform policies aimed at enhancing help-seeking behaviour and improving awareness of mental health and trauma.

Theoretical framework

Various theoretical frameworks such as theory of planned behaviour, health belief model, attachment theory, and cognitive behavioural therapy have been employed to investigate the interplay between early-life experiences, cognitive processes, and help-seeking behaviours. In this study, attachment theory [36] and cognitive behavioural theory [37] were adopted as foundational theories. Both theories attempt to understand factors which could impact on the creation of safe environment for the development of all persons. While attachment theory focuses on inter-personal relationship and mental functioning of individuals [38, 39], cognitive behaviour theory emphasizes individual’s development in the society which has implication on their decision-making in later years [40].

Both trauma and mental health develop across the course of one’s development and thus, decision to access mental health services could be based on one’s experiences or contextual factors [38, 39, 41]. Attachment theory and cognitive behaviour therapy offer a complex lens to study the synergy between trauma, mental health disorder and mental health help seeking behaviour. For example, Cheng, McDermott, and Lopez [42] elucidate the complex relationships among early attachment experiences, mental health outcomes, and cognitive barriers such as self-stigma, thereby demonstrating how these interconnected elements shape individuals’ attitudes and intentions regarding help-seeking behaviours. Similarly, Collins and Feeney [43] assert that formative life experiences significantly influence the development of attachment styles, which subsequently inform cognitive appraisals and decision-making processes related to seeking assistance. This body of literature underscores the necessity for interventions that target self-stigma, cultivate secure attachment relationships, and enhance overall mental health, with the aim of fostering more adaptive attitudes and intentions toward help-seeking.

Mental health, trauma and mental health help-seeking behaviour

The relationships between trauma, mental health, and mental health-seeking behaviour in adolescents and young adults present a complex and evolving landscape of inquiry [44, 45]. Traumatic experiences or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are characterized as events that potentially compromise an individual’s capacity for sound judgment [46]. Such traumatic events during childhood encompass but are not limited to physical and emotional abuse, neglect, parental death, household dysfunction, or exposure to substance abuse [47]. Research [48–50] indicates that a significant number of children encounter at least one traumatic event prior to reaching adulthood, which can severely hinder developmental progress. Moreover, young adults who have experienced trauma exhibit heightened vulnerability to a range of adversities, including physical and mental health issues, underachievement in educational and occupational domains, and an increased likelihood of engaging in criminal activities and substance addiction [51, 52]. Thus, the implications of childhood trauma are profound and enduring, significantly shaping adolescent development and influencing an individual’s long-term physical and mental health trajectory [53].

Recent research trends indicate the intricate interplay between trauma and mental health, as well as the multifaceted barriers that prevent individuals from seeking appropriate help [54, 55]. For example, many studies have reported a linear relationship between trauma and mental health disorders. Systematic reviews conducted by McKay et al. [56, 57] and Leung, Chan, and Ho [58] confirmed that trauma serves as a significant predictor of various mental health conditions. Similarly, longitudinal studies, such as those by Kisely et al. [59] and Bell et al. [60], illustrate that trauma exerts profound adverse effects on psychological well-being over time. Qualitative studies by Downey and Crummy [61] as well as Boterhoven de Haan et al. [62] further corroborate the assertion that trauma profoundly influences mental health outcomes.

Moreover, there are evidence of a relationship between mental health disorders and mental health seeking behaviour [63, 64]. The relationship is negative with studies reporting that individuals with mental health disorders rarely seek help [65, 66]. This contributes to deterioration of their condition [33, 67]. Mental health help-seeking represents a prevalent method for addressing mental health disorders and is characterized as an adaptive coping mechanism in which individuals seek external support to alleviate their mental health concerns [68]. This process can manifest in both formal and informal ways, including but not limited to, engaging with mental health professionals or seeking support from friends and family [69]. The incorporation of external assistance through mental health help-seeking plays a vital role in facilitating recovery and promoting integration into societal frameworks [70, 71]. Central to the phenomenon of help-seeking behaviour is individuals’ self-awareness of their mental health status and their identification of resources that can foster effective coping strategies for managing mental health disorders [72–74]. Upon achieving this self-realization, individuals may feel empowered to share their experiences and solicit help or guidance from their social circles [75, 76]. This underscores the importance of enhancing awareness and understanding of mental health disorders, including their potential triggers, such as trauma, among individuals.

Studies addressing the relationship between trauma, mental health disorder and mental health help seeking behaviour is very scarce. For instance, to the best of our knowledge, no study has explored the association between self-reported trauma awareness and mental health help seeking behaviour. The current study aimed to explore the contribution of trauma and mental health disorders in the variance in mental health help seeking behaviour.

Country contexts

The present study investigates the determinants influencing mental health help-seeking behaviour among adolescents and young adults in four non-Western countries, where mental health is significantly shaped by cultural norms and societal practices. For example, research indicates that mental health help-seeking behaviours among adolescents in Ghana are notably affected by stigma, sociocultural beliefs, financial constraints, academic-related stressors, and institutional barriers [77]. In contrast, in Egypt, factors such as female sex, urban residency, and a family history of mental health conditions have been identified as positively correlated with the propensity to seek professional mental health assistance. However, various impediments persist, including stigma, attitudinal barriers (such as a preference for self-reliance and, discomfort in discussing emotional issues), a lack of awareness regarding available mental health services, concerns regarding the efficacy of treatment options, and limited social support systems, all of which can hinder mental health help-seeking behaviour among adolescents and young adults [78].

In Bangladesh, several factors influence mental health help-seeking behaviours among young adults, including stigma, limited awareness of available mental health services, reliance on religious beliefs as alternative coping mechanisms, a perceived lack of necessity for professional support, and attitudinal barriers regarding self-reliance [79]. The authors further indicate that higher levels of mental health literacy, increased perceived stress, and exposure to individuals facing mental health challenges significantly increase the likelihood of seeking professional care. In a related Bangladeshi study, Dutta et al. [80] reported that women in rural communities sought mental health services from traditional and religious leaders based on two major reasons: affordability and their close proximity to such service providers. Similarly, Barbato et al. [81] and Musa [22] highlight comparable patterns in the UAE, where mental health help-seeking behaviour among adolescents and young adults is influenced by family stress, gender norms, cultural stigma, challenges associated with expatriate adjustment, and the severity of symptoms. Notably, males and individuals experiencing self-harm or anxiety-related disorders tend to delay seeking help, whereas those presenting with psychotic symptoms are more likely to pursue care promptly. The observed disparities in access to mental health support and awareness of mental health disorders among participants underscore the necessity for further research focusing on demographic factors to enhance our understanding of these dynamics.

Current study

Addressing the multifaceted challenges associated with mental health, trauma, and the process of seeking help necessitates the implementation of holistic interventions that integrate rigorous research, policy reforms, mental health education, and enhanced access to professional counseling services. This study is situated within non-western contexts, which have a disproportionately limited body of literature examining the interplay between trauma awareness, mental health disorders, and help-seeking behaviours. Furthermore, the existing research on the relationship between trauma awareness and mental health remains insufficiently explored, indicating a significant gap in the academic discourse. Therefore, the study formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis I

Trauma and mental health awareness predict mental health help-seeking behaviour.

Hypothesis II

Demographic variables contribute to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour.

Hypothesis III

Mental health help-seeking behaviour will mediate the relationship between awareness of trauma and mental health disorders.

In relation to Hypothesis III, the relationship between trauma and mental health disorders is well established. However, as to whether mental health help seeking could reduce the susceptibility of persons living with trauma to mental health is yet to be tested. We reasoned that access to mental health help seeking could lead to better mental health among adolescents and young adults.

Methods

The present study employed a cross-sectional design aimed at capturing participants’ understanding at a specific point in time. Such a design is particularly suitable for large-scale research endeavors that seek to establish a comprehensive understanding of a particular phenomenon [82, 83]. This methodological approach justifies the framework guiding the study reported herein.

Study participants

The participants in this study included adolescents and young adults from four diverse countries: Bangladesh, Egypt, Ghana, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Egypt and Ghana are located in Africa whereas Bangladesh and UAE are in Asia. While these countries were selected through a convenience sampling approach, it is crucial to acknowledge that mental health issues across the countries are deeply intertwined with local cultural contexts and practices [84, 85]. This intersectionality underscores the necessity of investigating the relationships among mental health, help-seeking behaviours, and trauma awareness across these various cultural landscapes.

In this study, adolescents and young adults were recruited from high schools and universities, respectively. The adolescent cohort consisted of individuals aged 13–18 years (grades 9–12), as it has been posited that this age range enables this cohort to provide informed and meaningful responses to survey instruments. The young adult participants, aged 18–35 years, were primarily sourced from various universities. The decision to focus the recruitment efforts within educational institutions was guided by prior literature, which has predominantly utilized learners from high schools [86, 87] and universities [88, 89]. Additionally, obtaining parental consent for a minority population in high school settings has been streamlined through the coordination facilitated by the schools themselves. A total of 16 educational institutions, comprising an equal distribution of 8 high schools and 8 universities, were purposively selected for inclusion in this research. Within each participating country, four institutions—two high schools and two universities—were invited to participate in the study.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic information of the participants who participated in this study. A total of 2472 participants participated in this study and were distributed as follows: Bangladesh (20%), Egypt (43%), Ghana (28%) and the UAE (9%). For gender, 71% were females, whereas 29% were males (see Table 1 for more details).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants

| N = 2472 | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Type Young adults Adolescents |

1871 601 |

76% 24% |

|

Nationality (n = 2469) UAE Egypt Ghana Bangladesh |

217 1070 695 487 |

9% 43% 28% 20% |

|

Gender (n= 2462) Male Female |

701 1761 |

29% 71% |

|

Training in Trauma Awareness (n = 2456) Yes No |

339 2117 |

14% 86% |

|

Training in Mental Health (n = 2464) Yes No |

758 1706 |

31% 69% |

|

Having close friends (n = 2470) Yes No |

1905 565 |

77% 23% |

|

Family income (n = 2469) Low income Middle income High income |

624 1654 191 |

25% 67% 8% |

Instrument

A four-part instrument was used for data collection. The first part collected demographic information from the participants (see Table 1). The second part employed the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale [90], a widely recognized tool for assessing the prevalence of mental health disorders within specific populations [91, 92]. This instrument consists of 21 items divided into three subscales, with each subscale comprising seven items [92, 93]. Responses are measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (most of the time). For this project, 19 items were found to be appropriate, which were distributed as follows: depression (n = 7), anxiety (n = 6) and stress (n = 6). Some of the items on the scale were as follows: ‘I don’t seem to experience any positive feelings at all’, ‘I experience breathing difficulty (e.g., excessively rapid breathing, breathlessness in the absence of physical exertion)’, ‘I tend to overreact to situations’ and ‘I feel that I am using a lot of nervous energy’. A composite mean of at least 2 suggests a high risk of mental health disorders among study participants.

The third part was the Individual Trauma Identification and Management Scale (ITIMS), which measures individuals’ self-awareness of trauma and management strategies. The instrument was adapted from the Parent Trauma Identification and Management scale [47] and Teacher Trauma Identification and Management Scale [94], which were developed from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s [95, 96] trauma management framework. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration framework elaborate awareness and supportive measures which could be institutionalized in schools, communities or organizations to manage trauma. There is a believe that children who are at risk of trauma maybe unaware of their susceptibility [97, 98]. Consequently, Teacher Trauma Identification and Management Scale and Parent Trauma Identification and Management scale were developed to ascertain whether adults in the lives of children would be able to identify children who are at risk [94]. The ITIMS is a self-reported awareness of trauma; operationalized in this study as events such as violence, abuse or rejection could impair one’s judgment [46, 47].

The revised instrument was first used and validated among adolescents (see authors in press). The instrument is made up of 18 items and is divided into two subscales, with 9 items each: Trauma Identification and Trauma-informed practices. Some of the items on the Trauma Identification subscale are ‘I have an in-depth understanding of events that cause trauma’, ‘I am able to see or identify people I do not trust’ and ‘I am able to know if I’m struggling to develop relationships with peers or others.’

In relation to the Trauma Informed Practice subscale, some of the items include ‘I can develop support plans for myself and peers who are traumatized’, ‘I can promote the inclusion of traumatized students in all school activities’ and ‘I can participate in decision-making on trauma management.’ The instrument is anchored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). A composite mean of at least four indicates high trauma awareness among study participants.

The last part was the revised Attitude toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPH-SF), which consists of 10 items [99]. Although the initial version consists of 18 items [100], Rayan, Baker, and Fawaz [99] validated it in Jordan and confirmed that 10 items were appropriate for measuring mental health help-seeking behaviour. It is a unidimensional scale that is anchored on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Some of the items are as follows: ‘If I believed I was experiencing a mental breakdown’, ‘my first inclination would be to receive professional attention’; ‘The idea of talking about problems with a counsellor strikes me as a poor way to eliminate emotional conflicts’; ‘If I were experiencing a serious emotional crisis at this point in my life’; and ‘I would be confident that I could find relief in counseling.’ A composite of at least four indicators indicates that high mental health helps me to seek behaviour among study participants.

The instrument was reviewed by eight experts (two from each country) with research interest in mental health from each of the three countries. They commented on cultural and contextual appropriateness of items before data collection. The reliability of the instruments was computed via Cronbach’s alpha: ITIMS (trauma identification [0.73] and TIP [0.87], revised DASS-21 (overall = 0.87; depression [0.87], anxiety [0.79] and stress [0.79] and ATSPPH-SF [0.75]).

Procedure

The study protocols received approval from the Social Science Research Ethics Committee at the United Arab Emirates University (ERSC_2024_4613). Subsequent to this approval, permission for data collection was sought from the respective universities. In Bangladesh, data collection was coordinated by the third author, while the ninth author undertook the same role in Ghana. The last author managed data collection efforts in Egypt, whereas authors one, two, five, nine and ten were responsible for data collection in the United Arab Emirates.

In both Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, prominent social media platforms, which target university students, were identified as key channels for data collection. For high school demographics, school leaders were tasked with disseminating information about the study to parents, who were requested to respond to participation inquiries via email or WhatsApp. Students whose parents did not provide feedback were excluded from participation. While the third author from Bangladesh collected data from adolescents through direct outreach within schools and young adults via the university online teaching and communication portal CANVAS, authors four and thirteen from Ghana conducted direct outreach within university classrooms to distribute questionnaires for completion by study participants. In each high school context, consent forms were issued to the students for parental endorsement. Only those students who returned signed consent forms were eligible for inclusion in the study.

The data collection for this study was conducted between May 2024 and October 2024, utilizing a combination of paper-and-pencil methods and Google Forms. In Bangladesh, both methodologies were employed to gather data effectively, whereas in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, data collection was conducted exclusively through Google Forms. In contrast, the paper-and-pencil method was implemented solely in Ghana. Prior to data collection, participants were provided with an information statement detailing the study’s objectives and procedures. They were assured that their identities and the names of their respective universities would remain confidential in any reporting. Furthermore, participants were informed that the data would be accessible to individuals outside the research team and that participation would not result in any form of compensation. They were also made aware of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without facing any repercussions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their engagement in the research. In relation to adolescents, consent was obtained from their parents before they completed the questionnaire.

Data analysis

The data were entered/transferred to Microsoft Excel for completeness before they were exported to SPSS for data analysis.

For Hypothesis I, hierarchical multiple regression was computed to explore the contribution of trauma and mental health awareness to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour. In Step 1, trauma and mental health awareness were entered into the model, while demographic variables (see Table 1) were entered into Step 2 to assess their contributions to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour. The analysis was performed at both the subscale and total scale levels. The assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity were not violated [101]. The effect size, observed using the R square (R2), was interpreted as follows [102]: small (0.02 − 0.09), moderate (0.10 − 0.19) and large (at least 0.20).

For Hypothesis II, moderation analysis was performed via the Andrew Hayes method to understand the impact of demographic variables on the relationships among mental health, trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviour. Following the computation of hierarchical regression, demographic variables that uniquely contributed to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour were included in the moderation analysis. The demographic variables were used as moderators, and mental health and trauma awareness were used as dependent and independent variables, respectively. The effect size discussed above was observed for this computation.

For Hypothesis III, mediation analysis was computed to explore the influence of mental health help on the relationship between mental health and trauma awareness. Mental health help was used as a mediator to assess its effect on the relationships between mental health and trauma awareness, which were used as dependent and independent variables, respectively.

Results

The mean scores computed for each of the scales were as follows: mental health help seeking (M = 3.22, SD = 0.66), mental health disorders (M = 1.37, SD = 0.66) and awareness of trauma (M = 3.31, SD = 0.65).

Predictors of mental health help-seeking

Hierarchical multiple regression was computed to explore the predictors of mental health help-seeking behaviour (see Table 2). In step 1, mental health and trauma awareness made an 11% contribution to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour, R2 = 0.11; F (2, 2290) = 144.70, p =.001. Individually, both mental health (beta = 0.19, p =.001) and awareness of trauma (beta = 0.28, p =.001) made unique contributions to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour.

Table 2.

Predictors of mental health help-seeking behaviour

| Unst. Beta | S.E. | Stand. Beta | t | p | Confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Step 1 | |||||||

| Mental Health | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 9.45 | 0.001** | 0.14 | 0.22 |

| Trauma awareness | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 14.13 | 0.001** | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| Step 2 | |||||||

| Mental Health | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 6.67 | 0.001** | 0.10 | 0.18 |

| Trauma awareness | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 13.12 | 0.001** | 0.23 | 0.31 |

| Type | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 6.68 | 0.001** | 0.15 | 0.28 |

| Nationality | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 4.74 | 0.001** | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Gender | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 6.39 | 0.001** | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| Training in Trauma Awareness | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.43 | 0.67 | − 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Training in Mental Health | − 0.06 | 0.03 | − 0.05 | −1.98 | 0.05* | − 0.13 | − 0.001 |

| Having close friends | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.42 | − 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Family income | 0.03 | 0.023 | 0.02 | 1.08 | 0.28 | − 0.02 | 0.07 |

Note: *P ≤.05; **P ≤.01

In step 2, demographic variables were added to the model. The demographic variables made a 3% contribution to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour, R2 change = 0.03; F (7, 2283) = 12.08, p =.001. The combined independent and demographic variables made a 14% contribution to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour, R2 = 0.14; F (9, 2283) = 42.63, p =.001. While mental health and trauma awareness significantly contributed to mental health help-seeking behaviour, four demographic variables significantly contributed to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour.

At the subscale level, in step 1, the predictors made a 12% contribution to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour, R2 = 0.12; F (5, 2287) = 59.64, p =.001. With the exception of depression, the individual subscales significantly contributed to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour. However, trauma identification made a greater contribution than the other predictors did (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of mental health help-seeking behaviour

| Unst. Beta | S.E. | Stand. Beta | t | p | Confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Step 1 | |||||||

| Depression | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.86 | − 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Anxiety | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 3.57 | 0.001** | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Stress | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 2.13 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.13 |

| Trauma identification | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 7.14 | 0.001** | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| Trauma informed practices | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 4.45 | 0.001** | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Step 2 | |||||||

| Depression | − 0.03 | 0.03 | − 0.03 | − 0.86 | 0.39 | − 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 3.09 | 0.002** | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Stress | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 2.31 | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Trauma identification | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 6.00 | 0.001** | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| Trauma informed practices | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 5.11 | 0.001** | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| Type | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 6.82 | 0.001** | 0.16 | 0.28 |

| Nationality | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 5.09 | 0.001** | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Gender | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 6.03 | 0.001** | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| Training in Trauma Awareness | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.65 | − 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Training in Mental Health | − 0.07 | 0.03 | − 0.05 | −2.10 | 0.04* | − 0.13 | − 0.004 |

| Having close friends | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.42 | − 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Family income | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.25 | − 0.02 | 0.07 |

Note: **p ≤.01; *p ≤.05

In step 2, the demographic variables individually made a 3% contribution to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour, F (7, 2280) = 12.05, p =.001. The combined demographic variables and independent variables made a 15% contribution to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour, F (12, 2280) = 32.72, p =.001. With respect to the independent variables, only depression did not make individual contributions to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour. Moreover, four demographic variables, namely, the type of participants, nationality, gender and training in mental health, significantly contributed to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour. Here, trauma identification and the type of participants made greater contributions to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour (see Table 3).

Moderators of trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviour

Moderation analysis was computed to explore the influence of demographic variables on the relationship between trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviour (see Table 4). First, participant type significantly moderated (R2 = 0.10; F [3, 2317] = 81.21, p =.001) the relationship between trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviour, beta = − 0.16, t = −3.60, p =.0003, 95% CI (−0.24, − 0.07). Individually, trauma awareness and the type of participant significantly contributed to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour.

Table 4.

Moderators of trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviour

| Beta | S.E. | t | p | Confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

|

Type Trauma awareness Trauma awareness x Type |

0.70 0.47 − 0.16 |

0.15 0.06 0.04 |

4.64 7.83 −3.60 |

0.001** 0.001** 0.001** |

0.40 0.35 − 0.24 |

0.99 0.59 − 0.07 |

|

Nationality Trauma awareness Trauma awareness x Nationality |

0.33 0.50 − 0.08 |

0.09 0.07 0.03 |

3.74 7.20 −2.92 |

0.0002** 0.001** 0.07 |

0.16 0.36 − 0.13 |

0.51 0.64 − 0.02 |

|

Gender Trauma awareness Trauma awareness x Gender |

0.19 0.29 − 0.02 |

0.14 0.07 0.04 |

1.32 3.92 − 0.36 |

0.19 0.0001** 0.72 |

− 0.09 0.15 − 0.10 |

0.46 0.44 0.07 |

|

Training in mental health Trauma awareness Trauma awareness x Training in mental health |

0.35 0.44 − 0.09 |

0.15 0.08 0.04 |

2.32 5.60 −2.09 |

0.02* 0.001** 0.14 |

0.05 0.29 − 0.18 |

0.65 0.59 − 0.006 |

Note: **p ≤.01; *p ≤.05

When participants were either young adults (beta = 0.32, t = 13.07, p =.001, 95% CI [0.27, 0.36]) or adolescents (beta = 0.16, t = 4.41, p =.001, 95% CI [0.09, 0.23]), a significant relationship was found between trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviour.

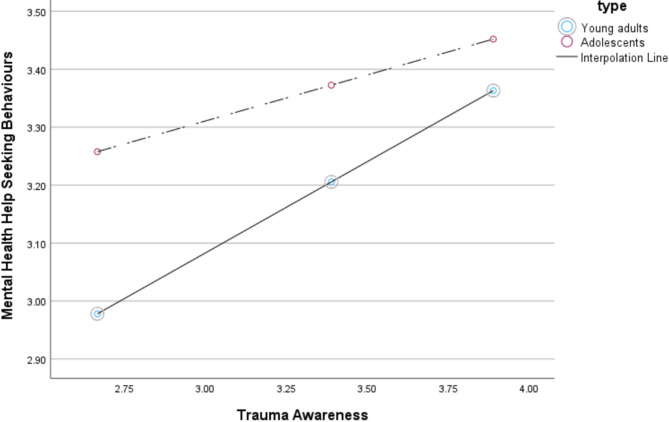

Figure 1 shows that when trauma awareness is low, mental health-seeking behaviour is more common among adolescents than among young adults. However, when awareness of trauma increases, mental health help-seeking behaviour increases. Compared with young adults, adolescents are more likely to seek mental health.

Fig. 1.

Participant type as moderator of trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behavior. Note: Graphical summary of moderation showing the interactive effective of participant type (adolescents vs. young adults) on the relationship between self-reported trauma awareness and mental health help seeking behaviour. The broken lines depict ratings by adolescents while the thick line represents ratings by young adults

Moderators of mental health and mental health help seeking behaviour

Moderators of mental health and mental health help-seeking behaviour were explored (see Table 5). Only the type of participant emerged as a significant (R2 = 0.07; F [3, 2381] = 65.68, p =.001) moderator of the relationship between mental health and mental health help-seeking behaviour, beta = 0.33, t = 0.04, p =.001, 95% CI (0.24, 0.42). Individually, mental health disorders (beta = − 0.24, t = −4.03, p =.0001, 95% CI [−0.35, − 0.12]) and participant type (beta = − 0.25, t = −3.65, p =.0003, 95% CI [−0.38, − 0.12]) were direct predictors of mental health help-seeking behaviour. To expand further, in the event that participants were either young adults (beta = 0.09, t = 4.18, p =.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.14]) or adolescents (beta = 0.42, t = 0.04, t = 11.12, p =.001, 95% CI [0.35, 0.50]), a significant relationship was found between mental health and mental health help-seeking behaviour.

Table 5.

Moderators of mental health and mental health help seeking behaviour

| Beta | S.E. | t | p | Confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

|

Type Mental Health Mental Health x Type |

− 0.25 − 0.24 0.33 |

0.07 0.06 0.04 |

−3.65 −4.03 7.47 |

0.0003** 0.0001** 0.0001** |

− 0.38 − 0.35 0.24 |

− 0.16 − 0.12 0.42 |

|

Nationality Mental Health Mental Health x Nationality |

0.07 0.39 − 0.07 |

0.04 0.06 0.02 |

2.05 6.77 −3.49 |

0.14 0.0001** 0.0001** |

0.003 0.28 − 0.12 |

0.14 0.51 − 0.03 |

|

Gender Mental Health Mental Health x Gender |

− 0.07 − 0.16 0.20 |

0.07 0.08 0.04 |

−1.15 −2.00 4.42 |

0.25 0.05* 0.001** |

− 0.21 − 0.32 0.11 |

05 − 0.003 0.29 |

|

Training in mental health Mental Health Mental Health x Training in mental health |

− 0.07 0.13 0.03 |

0.06 0.08 0.04 |

−1.05 1.66 0.72 |

0.29 0.10 0.47 |

− 0.19 − 0.02 − 0.06 |

0.06 0.29 0.12 |

Note: *P ≤.05; **P ≤.01

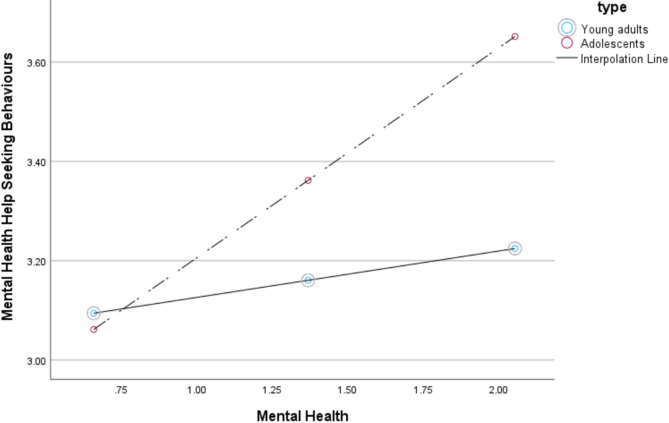

Figure 2 shows that when the risk of mental health is low, mental health help-seeking behaviour is low for both young adults and adolescents. However, as the risk of mental health increases, mental health-seeking behaviour increases for both young adults and adolescents, with the latter exhibiting greater help-seeking behaviour than the former.

Fig. 2.

Participant type as a moderator of mental health and mental health help-seeking behavior. Note: Graphical summary of moderation showing the interactive effective of participant type (adolescents vs. young adults) on the relationship between Mental health disorder and mental health help seeking behaviour. The broken lines depict ratings by adolescents while the thick line represents ratings by young adults

Mental health help seeking as a mediator of trauma and mental health

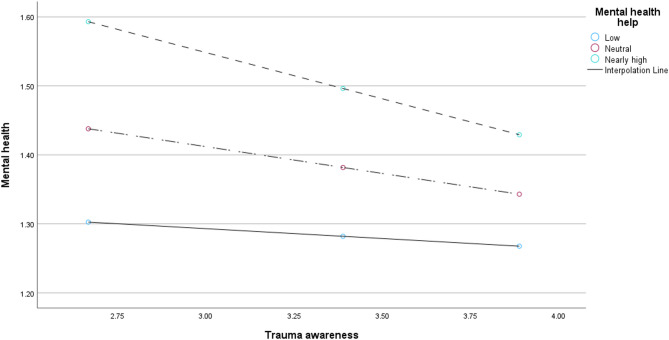

First, mediation analysis was computed to explore the effect of mental health help-seeking behaviour on the relationship between trauma awareness and mental health. Both trauma awareness (beta = 0.23, t = 3.05, p =.002, 95% CI [0.08, 0.38]) and mental health help-seeking behaviour (beta = 0.52, t = 6.43, p =.001, 95% CI [0.36, 0.68]) had direct effects on mental health. The overall model was significant, R2 = 0.04, F (3, 2317) = 35.83, p =.001. Most importantly, mental health help-seeking behaviour had an indirect effect (R2 change = 0.006; F [1, 2317] = 16.06, p =.001) on the relationship between trauma awareness and mental health, beta = − 0.10, p =.0001, 95% CI (−0.14, − 0.05). When mental health-seeking behaviour is low (M = 2.70), no relationship was found between trauma awareness and mental health (beta = − 0.03, p =.22, 95% CI [−0.07, 02]). However, when mental health help-seeking behaviour is either neutral (M = 3.21; beta = − 0.08, p =.001, 95% CI [−0.12, − 0.03]) or nearly high (M = 3.80; beta = − 0.13, p =.001, 95% CI [−0.19, − 0.08), a relationship was found between mental health and trauma awareness.

As shown in Fig. 3, although there is no apparent interaction, it could be argued that the lower one’s mental health help-seeking behaviour is, the lower one’s knowledge of trauma and risk of mental health. Similarly, as mental health help increases, knowledge of trauma awareness decreases, and the risk of mental health disorders increases. Additionally, as knowledge of trauma increases, help seeking (whether it is low, neutral or nearly high) reduces the risk to mental health.

Fig. 3.

Mental health help as a mediator of mental health and trauma awareness. Note: Graphical summary of mediation showing the interactive effective of mental health help seeking behaviour on the relationship between Mental health disorder and self-reported trauma awareness. The broken lines depict low and neutral ratings on mental health help seeking behaviour while the thick line represents nearly high ratings on the mental health help seeking behaviour

Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the role of trauma awareness and mental health in influencing variations in help-seeking behaviours for mental health services across four non-Western countries: Bangladesh, Egypt, Ghana, and the UAE. This research is grounded in the limited literature addressing the interrelationships among mental health, trauma, and help-seeking behaviours, which underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of these dynamics in diverse cultural contexts.

The findings of the present study provide robust support for Hypothesis I, indicating that mental health awareness and trauma recognition significantly contribute to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour among individuals. Hierarchical regression analyses demonstrated that with each increase in awareness of trauma and risk factors associated with mental health, there is a corresponding 11% increase in mental health help-seeking behaviour. The weight of the result could be interpreted as moderate [102]. Prior research has focused predominantly on the relationship between mental health per se and help-seeking behaviour [89, 103]. In contrast, the current study extends the literature by elucidating the connection between trauma awareness and mental health help-seeking behaviours. These findings suggest that enhancing awareness of trauma and mental health among young adults and adolescents may foster a more proactive approach to seeking mental health support. Once individuals in these populations acquire knowledge regarding trauma and its mental health ramifications, they are likely to develop a comprehensive understanding of the available resources for obtaining help. Furthermore, across the four countries included in this study, persistent stigma and inadequate awareness regarding mental health and trauma have been reported in the literature.

Hypothesis II received partial support, as certain demographic variables contributed to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviour. Notably, the type of participant—adolescent or young adult—exerted a significant influence on this variance and moderated the relationships among mental health, trauma awareness, and help-seeking behaviour. The moderation analysis revealed that, with increasing trauma awareness and mental health understanding, adolescents were more inclined to access mental health services than their young adult counterparts were. The weight of the result could be interpreted as moderate as the model explained 10% of the variance [102] in the relationship between trauma awareness and mental health help seeking behaviour. While young adults are typically perceived as more mature and independent and capable of making informed decisions regarding their well-being, the findings indicate a potential decline in help-seeking behaviour in this demographic as they gain more knowledge about trauma and mental health. This observed trend may be linked to the stigma associated with mental health issues across various cultural contexts [33, 104, 105]. Cultural stereotypes surrounding mental health can create significant barriers to disclosure and the willingness to seek assistance [106–108]. It appears that adolescents may be less affected by stigma, possibly due to their engagement in more open discussions about mental health and the support systems available to mitigate mental health burdens.

The findings of this study lend support to Hypothesis III, demonstrating that mental health help-seeking behaviour serves as a mediator in the relationship between mental health and trauma awareness among the study participants. Specifically, the results indicate that as engagement in mental health help-seeking behaviours increases, so does knowledge about mental health, while concurrently, the risk associated with mental health issues diminishes. It is useful to indicate here that the effect size was small [102]. Although these findings are novel, the literature suggests that awareness programs play a crucial role in promoting mental health help-seeking behaviour [16, 33, 109]. It is plausible that such awareness programs cover a wide array of topics, including the onset of mental health disorders, core symptoms, and available intervention services. In non-Western contexts, there may be a pressing need for innovative programs specifically designed to encourage individuals to seek help when they perceive early signs of mental health issues. Notably, evidence indicates that many individuals within society remain unaware of mental health disorders [106, 110] and trauma-related issues [111, 112].

An intriguing finding worth discussing is the relationship between trauma awareness and the prevalence of mental health disorders. The computational mediation analysis indicates that trauma awareness has a significant effect on mental health outcomes; specifically, for every 0.24 unit increase in trauma awareness, there is a corresponding increase in the risk of mental health disorders. This suggests that as individuals’ understanding of trauma increases, so does their susceptibility to mental health challenges. Conversely, it can be posited that a reduction in trauma awareness may lead to a decrease in the risk associated with mental health disorders. The significance of trauma awareness cannot be overstated, as it plays a crucial role in enabling individuals to recognize their potential risk for mental health issues. The literature supports the notion of a synergistic relationship between mental health and traumatic experiences [113–116]. Notably, research has shown that children with a history of trauma are more likely to develop mental health disorders as they mature [57, 114, 117]. These findings may particularly resonate with those of the study population, who may benefit from enhanced trauma awareness as a means of identifying their risk for mental health disorders. Many individuals with mental health disorders remain undiagnosed worldwide [118, 119], underscoring the importance of integrating trauma training with efforts to raise awareness of mental health issues.

Study limitations

The current study acknowledges several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. Primarily, it utilized self-reported assessments administered to young adults and adolescents, which may not reliably reflect their true levels of trauma awareness and mental health status. To increase the robustness of future research, it is recommended that qualitative methodologies be employed, allowing for a more nuanced exploration of trauma awareness and mental health among young adults enrolled in higher education institutions. Furthermore, future study could use comparable or adapt an existing instrument to explore mental health help seeking behaviour across countries. Moreover, the scope of this study was confined to young adults and adolescents within educational settings, thereby excluding those of the same age who are not currently enrolled in formal education. As a result, the conclusions drawn from this research should be contextualized within this specific population. Future studies should consider incorporating young adults outside educational programs, thus fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the relevant issues.

Despite these limitations, a significant strength of this study is its utilization of diverse data collection methods. By employing multiple languages and a variety of approaches, including online surveys and pen-and-paper questionnaires, this study enhances the validity of its data and broadens the applicability of its findings.

Conclusion and study implications

The current study aimed to investigate the interplay between mental health, trauma, and help-seeking behaviour. Specifically, this study sought to elucidate the contributions of mental health status and trauma experiences to the variance observed in help-seeking behaviour for mental health issues. Of the three hypotheses formulated for this research, two received full empirical support, whereas one was partially supported.

In reference to Hypothesis I, the results indicated that trauma and mental health status collectively predicted help-seeking behaviour for individuals with mental health concerns. Hypothesis II was partially supported, revealing that certain demographic variables—including gender, nationality, participant type, and mental health training—contributed individually to the variance in mental health help-seeking behaviours. Notably, participant type emerged as the sole demographic factor that moderated the relationships among trauma awareness, mental health status, and help-seeking behaviour. With respect to Hypothesis III, the findings suggested that help-seeking behaviour functioned as a mediating variable in the relationship between mental health disorders and trauma awareness. To date, this study appears to be the first comparative investigation that examines the interrelationships among trauma, mental health, and help-seeking behaviour within non-Western contexts.

The current study also makes a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge, offering valuable insights for future policy and practice implementation. One key recommendation for policymakers across various countries is to increase awareness of trauma and mental health disorders. Increased knowledge in these areas is essential, as it can positively influence help-seeking behaviours related to mental health. To achieve this goal, policymakers might collaborate with universities and schools to create tailored mental health and trauma awareness programs designed specifically to meet students’ needs. Additionally, developers of these training programs should consult with students to identify triggers for mental health challenges, the onset of trauma, and the available intervention or support systems within their communities.

Moreover, policymakers could design focused training initiatives for both adolescents and young adults. Particularly for young adults, these programs emphasize the importance of disclosing mental health issues and encourage them to seek support from recognized resources. Finally, health professionals could establish mental health units within schools as part of an effort to make help-seeking services more visible to students. By recognizing these facilities, young adults and adolescents may be more inclined to visit and engage with professionals, leading to the essential support they need to alleviate the burden of trauma and mental health disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants who consented to participant in this study.

Author contributions

MPO, RY, SN, EMG, LF, EC, YAS, MAE, AAA, TB, MMA, ES, NO, DM and AM contributed to the conception of the study. MPO, EMG, LM, EC, YAS, MAE, AAA, TB, MMA, ES, NO, DM and AA collected the data. MPO, and AM analysed and interpreted the data. MPO, RY, SN, EMG, LF, EC, YAS, MAE, AAA, TB, MMA, ES, NO, DM and AM contributed to the writing, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Office of the Associate Provost for Research at United Arab Emirates University.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and informed consent

All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Institutional Review Committee of the United Arab Emirates University (ERSC_2024_4613) approved this study and its protocols. Each study participant was informed of the purpose, method, expected benefit, and risk of the study. They were also informed of their full right to not participate in or withdraw from the study at any time. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their guidance/parents before taking part in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO: Mental Health. Author. 2022 Https://Www.Who.Int/News-Room/Fact-Sheets/Detail/Mental-Health-Strengthening-Our-Response.

- 2.Lomax S, Cafaro CL, Hassen N, Whitlow C, Magid K, Jaffe G. Centering mental health in society: a human rights approach to well-being for all. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2022;92:364–70. 10.1037/ort0000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbert C. Enhancing mental health, Well-Being and active lifestyles of university students by means of physical activity and exercise research programs. Front Public Health. 2022;10. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.849093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hammoudi Halat D, Soltani A, Dalli R, Alsarraj L, Malki A. Understanding and fostering mental health and well-being among university faculty: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2023;12: 4425. 10.3390/jcm12134425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The World Bank: Health Nutrition and Population Statistics| DataBank. (2018).

- 6.Gupta MD. The power of 1.8 Billion: Adolescents, Youth and the Transformation of the Future. New York. (2014).

- 7.American Psychological Association: Adulthood. Author. 2023 https://dictionary.apa.org/adulthood

- 8.World Health Organization: Mental health of adolescents. Author. 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

- 9.Stelmach R, Kocher EL, Kataria I, Jackson-Morris AM, Saxena S, Nugent R. The global return on investment from preventing and treating adolescent mental disorders and suicide: a modelling study. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e007759. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blakemore S-J. Adolescence and mental health. Lancet. 2019;393:2030–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kopinak JK. Mental health in developing countries: challenges and opportunities in introducing Western mental health system in Uganda. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;3:22–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duby Z, McClinton Appollis T, Jonas K, Maruping K, Dietrich J, LoVette A, Kuo C, Vanleeuw L, Mathews C. As a young pregnant girl… the challenges you face: exploring the intersection between mental health and sexual and reproductive health amongst adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:344–53. 10.1007/s10461-020-02974-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golin CE, Amola O, Dardick A, Montgomery B, Bishop L, Parker S, Owens LE. Chap. 5 poverty, personal experiences of violence, and mental health: Understanding their complex intersections among Low-Income women. In: poverty in the united States. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 63–91.

- 14.Mbithi G, Abubakar A. Assessing and supporting mental health outcomes among adolescents in urban informal settlements in Kenya and Uganda. Eur Psychiatry. 2023;66:988–S989. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calear AL, Morse AR, Batterham PJ, Forbes O, Banfield M. Silence is deadly: a controlled trial of a public health intervention to promote help-seeking in adolescent males. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51:274–88. 10.1111/sltb.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eigenhuis E, Waumans RC, Muntingh ADT, Westerman MJ, van Meijel M, Batelaan NM, van Balkom AJLM. Facilitating factors and barriers in help-seeking behaviour in adolescents and young adults with depressive symptoms: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0247516. 10.1371/journal.pone.0247516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo S, Nguyen H, Weiss B, Ngo VK, Lau AS. Linkages between mental health need and help-seeking behavior among adolescents: moderating role of ethnicity and cultural values. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62:682–93. 10.1037/cou0000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:183–211. 10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Omari O, Khalaf A, Al Sabei S, Al Hashmi I, Al Qadire M, Joseph M, Damra J. Facilitators and barriers of mental health help-seeking behaviours among adolescents in Oman: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;76:591–601. 10.1080/08039488.2022.2038666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguirre Velasco A, Cruz ISS, Billings J, Jimenez M, Rowe S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:293. 10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagen BNM, Sawatzky A, Harper SL, O’Sullivan TL, Jones-Bitton A. Farmers aren’t into the emotions and things, right?? A qualitative exploration of motivations and barriers for mental health help-seeking among Canadian farmers. J Agromedicine. 2022;27:113–23. 10.1080/1059924X.2021.1893884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musa M. Mental health in the middle east: historical perspectives, current challenges, and future implications. Saudi J Humanit Soc Sci. 2024;9:138–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghuloum S, Al-Thani HAQF, Al-Amin H. Religion and mental health: an Eastern Mediterranean region perspective. Front Psychol. 2024. 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1441560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alqasir A, Ohtsuka K. The impact of religio-cultural beliefs and superstitions in shaping the understanding of mental disorders and mental health treatment among Arab Muslims. J Spiritual Ment Health. 2024;26:279–302. 10.1080/19349637.2023.2224778. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ametaj AA, Hook K, Cheng Y, Serba EG, Koenen KC, Fekadu A, Ng LC. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with severe mental illness in a non-western setting: data from rural Ethiopia. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13:684–93. 10.1037/tra0001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu D, Nagpal S, Pillai RR, Mutiso V, Ndetei D, Bhui K. Building youth and family resilience for better mental health: developing and testing a hybrid model of intervention in low- and middle-income countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220:4–6. 10.1192/bjp.2021.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas J, Galadari A. There Is No Health Without Mental Health: The Middle East and North Africa. Presented at the (2022).

- 28.Ran M-S, Hall BJ, Su TT, Prawira B, Breth-Petersen M, Li X-H, Zhang T-M. Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific Rim region: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:8. 10.1186/s12888-020-02991-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark DA, Wooden M. Mental health and productivity at work: does what you do matter? Labour Econ. 2017;46:150–65. 10.1016/j.labeco.2017.05.001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Oliveira C, Saka M, Bone L, Jacobs R. The role of mental health on workplace productivity: a critical review of the literature. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2023;21:167–93. 10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arafat SMY. Mental Health and Suicide in Bangladesh. Presented at the (2023).

- 32.Lew B, Lester D, Mustapha FI, Yip P, Chen Y-Y, Panirselvam RR, Hassan AS, In S, Chan LF, Ibrahim N, Chan CMH, Siau CS. Decriminalizing suicide attempt in the 21st century: an examination of suicide rates in countries that penalize suicide, a critical review. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:424. 10.1186/s12888-022-04060-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Javed A, Lee C, Zakaria H, Buenaventura RD, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Duailibi K, Ng B, Ramy H, Saha G, Arifeen S, Elorza PM, Ratnasingham P, Azeem MW. Reducing the stigma of mental health disorders with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58: 102601. 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boden M, Zimmerman L, Azevedo KJ, Ruzek JI, Gala S, Magid A, Cohen HS, Walser N, Mahtani R, Hoggatt ND, McLean KJ. Addressing the mental health impact of COVID-19 through population health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102006. 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elshamy F, Hamadeh A, Billings J, Alyafei A. Mental illness and help-seeking behaviours among middle Eastern cultures: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative data. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0293525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0293525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harlow E. Attachment theory: developments, debates and recent applications in social work, social care and education. J Soc Work Pract. 2021;35:79–91. 10.1080/02650533.2019.1700493. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leahy R, Clark D, Dozois D. Cognitive-Behavioral theories. In: Crisp H, Gabbard GO, editors. Gabbard’s textbook of psychotherapeutic treatments. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. p. 151–168.

- 38.Yip J, Ehrhardt K, Black H, Walker DO. Attachment theory at work: a review and directions for future research. J Organ Behav. 2018. 10.1002/job.2204. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bucci S, Roberts NH, Danquah AN, Berry K. Using attachment theory to inform the design and delivery of mental health services: a systematic review of the literature. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2015;88:1–20. 10.1111/papt.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright JH, Reis J, Casey DA. Cognitive-Behavioral theories. In: Crisp H, Gabbard GO, editors. Gabbard’s textbook of psychotherapeutic treatments. American Psychiatric Pub; 2022;169–200.

- 41.Corcoran M, McNulty M. Examining the role of attachment in the relationship between childhood adversity, psychological distress and subjective well-being. Child Abuse Negl. 2018. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng H-L, McDermott RC, Lopez FG. Mental health, self-stigma, and help-seeking intentions among emerging adults. Couns Psychol. 2015;43:463–87. 10.1177/0011000014568203. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins NL, Feeney BC. A safe haven: an attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:1053–73. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Than V, Doroud N, O’Brien L. Mental health service utilization and help seeking behaviours of adult Cambodians living in Western countries: a systematic scoping review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2024;70:778–91. 10.1177/00207640241230848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daniel AM, Treece KS. Law enforcement pathways to mental health: secondary traumatic stress, social support, and social pressure. J Police Crim Psychol. 2022;37:132–40. 10.1007/s11896-021-09476-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mustafa A, Opoku MP, Elhoweris H, Abdullah EM. Raising trauma awareness in the Middle East: exploration of parental knowledge about the identification and management of trauma among children in Egypt. J Fam Trauma Child Custody Child Dev. 2024;21:477–97. 10.1080/26904586.2024.2372255. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soleimanpour S, Geierstanger S, Brindis CD. Adverse childhood experiences and resilience: addressing the unique needs of adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:S108–14. 10.1016/j.acap.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunzell T, Stokes H, Waters L. Shifting teacher practice in trauma-affected classrooms: practice pedagogy strategies within a trauma-informed positive education model. School Ment Health. 2019;11:600–14. 10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crawley RD, Rázuri EB, Lee C, Mercado S. Lessons from the field: implementing a trust-based relational intervention (TBRI) pilot program in a child welfare system. J Public Child Welfare. 2021;15:275–98. 10.1080/15548732.2020.1717714. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brunzell T, Stokes H, Waters L, TRAUMA-INFORMED FLEXIBLE, LEARNING: CLASSROOMS THAT STRENGTHEN REGULATORY ABILITIES. Trauma-informed flexible, learning: classrooms that strengthen regulatory abilities. Int J Child Youth Fam Stud. 2016;7:218. 10.18357/ijcyfs72201615719. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giovanelli A, Reynolds AJ, Mondi CF, Ou S-R. Adverse childhood experiences and adult well-being in a low-income, urban cohort. Pediatrics. 2016. 10.1542/peds.2015-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guada JM, Conrad TL, Mares AS. The aftercare support program: an emerging group intervention for transition-aged youth. Soc Work Groups. 2012;35:164–78. 10.1080/01609513.2011.604765. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerson R, Rappaport N. Traumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in youth: recent research findings on clinical impact, assessment, and treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:137–43. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghafoori B, Barragan B, Palinkas L. Mental health service use among trauma-exposed adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:239–46. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Boer K, Arnold C, Mackelprang JL, Nedeljkovic M. Barriers and facilitators to treatment seeking and engagement amongst women with complex trauma histories. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30. 10.1111/hsc.13823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.McKay MT, Kilmartin L, Meagher A, Cannon M, Healy C, Clarke MC. A revised and extended systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;156:268–83. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKay MT, Cannon M, Chambers D, Conroy RM, Coughlan H, Dodd P, Healy C, O’Donnell L, Clarke MC. Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143:189–205. 10.1111/acps.13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung DYL, Chan ACY, Ho GWK. Resilience of emerging adults after adverse childhood experiences: a qualitative systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23:163–81. 10.1177/1524838020933865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kisely S, Abajobir AA, Mills R, Strathearn L, Clavarino A, Najman JM. Child maltreatment and mental health problems in adulthood: birth cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:698–703. 10.1192/bjp.2018.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bell CJ, Foulds JA, Horwood LJ, Mulder RT, Boden JM. Childhood abuse and psychotic experiences in adulthood: findings from a 35-year longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214:153–8. 10.1192/bjp.2018.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Downey C, Crummy A. The impact of childhood trauma on children’s wellbeing and adult behavior. Eur J Trauma Dissociation. 2022;6: 100237. 10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100237. [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Boterhoven KL, Lee CW, Correia H, Menninga S, Fassbinder E, Köehne S, Arntz A. Patient and therapist perspectives on treatment for adults with PTSD from childhood trauma. J Clin Med. 2021;10:954. 10.3390/jcm10050954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Filiatreau LM, Ebasone PV, Dzudie A, Ajeh R, Pence B, Wainberg M, Nash D, Yotebieng M, Anastos K, Pefura-Yone E, Nsame D, Parcesepe AM. Correlates of self-reported history of mental health help-seeking: a cross-sectional study among individuals with symptoms of a mental or substance use disorder initiating care for HIV in Cameroon. BMC Psychiatry. 2021. 10.1186/s12888-021-03306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doll CM, Michel C, Rosen M, Osman N, Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. Predictors of help-seeking behaviour in people with mental health problems: a 3-year prospective community study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021. 10.1186/s12888-021-03435-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brower KJ. Professional stigma of mental health issues: physicians are both the cause and solution. Acad Med. 2021. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee J, Jeong HJ, Kim S. Stress, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic and their use of mental health services. Innov High Educ. 2021. 10.1007/s10755-021-09552-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Usmani SS, Sharath M, Mehendale M. Future of mental health in the metaverse. Gen Psychiatry. 2022. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rickwood D. Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2012;173. 10.2147/PRBM.S38707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.van Weeghel J, van Zelst C, Boertien D, Hasson-Ohayon I. Conceptualizations, assessments, and implications of personal recovery in mental illness: a scoping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2019;42:169–81. 10.1037/prj0000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bizzotto N, de Bruijn G, Schulz PJ. Clusters of patient empowerment and mental health literacy differentiate professional help-seeking attitudes in online mental health communities users. Health Expect. 2025. 10.1111/hex.70153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hyseni Duraku Z, Davis H, Blakaj A, Ahmedi Seferi A, Mullaj K, Greiçevci V. Mental health awareness, stigma, and help-seeking attitudes among Albanian university students in the Western balkans: a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2024. 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1434389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McLoughlin E, Fletcher D, Slavich GM, Arnold R, Moore LJ. Cumulative lifetime stress exposure, depression, anxiety, and well-being in elite athletes: a mixed-method study. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2021;52: 101823. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shukla S. Role of cultural resources in mental health: an existential perspective. Front Psychol. 2022. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.860560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mosiichuk V. Self-realization & self-development: conceptualization of the conscious choice and the unconscious position of the subject. SSRN Electron J. 2023. 10.2139/ssrn.4395508. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rennick-Egglestone S, Ramsay A, McGranahan R, Llewellyn-Beardsley J, Hui A, Pollock K, Repper J, Yeo C, Ng F, Roe J, Gillard S, Thornicroft G, Booth S, Slade M. The impact of mental health recovery narratives on recipients experiencing mental health problems: qualitative analysis and change model. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226201. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hassett A, Isbister C. Young men’s experiences of accessing and receiving help from child and adolescent mental health services following self-harm. Sage Open. 2017. 10.1177/2158244017745112. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Addy ND, Agbozo F, Runge-Ranzinger S, Grys P. Mental health difficulties, coping mechanisms and support systems among school-going adolescents in Ghana: a mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0250424. 10.1371/journal.pone.0250424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baklola M, Terra M, Elzayat MA, Abdelhady D, El-Gilany A-H, collaborators, A. team of. Pattern, barriers, and predictors of mental health care utilization among Egyptian undergraduates: a cross-sectional multi-centre study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23: 139. 10.1186/s12888-023-04624-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sifat MS, Tasnim N, Hoque N, Saperstein S, Shin RQ, Feldman R, Stoebenau K, Green KM. Motivations and barriers for clinical mental health help-seeking in Bangladeshi university students: a cross-sectional study. Glob Ment Health. 2022;9:211–20. 10.1017/gmh.2022.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dutta GK, Sarker BK, Ahmed HU, Bhattacharyya DS, Rahman MM, Majumder R, Biswas TK. Mental healthcare-seeking behavior during the perinatal period among women in rural Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022. 10.1186/s12913-022-07678-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barbato M, Hemeiri A, Nafie S, Dhuhair S, Dabbagh BA. Characterizing individuals accessing mental health services in the UAE: a focus on youth living in Dubai. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15:29. 10.1186/s13033-021-00452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-sectional studies. Chest. 2020;158:S65-71. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kesmodel US. Cross-sectional studies – what are they good for? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:388–93. 10.1111/aogs.13331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Magnus AM, Advincula P. Those who go without: an ethnographic analysis of the lived experiences of rural mental health and healthcare infrastructure. J Rural Stud. 2021;83:37–49. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.02.019. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Edyburn KL, Bertone A, Raines TC, Hinton T, Twyford J, Dowdy E. Integrating intersectionality, social determinants of health, and healing: A new training framework for school-based mental health. School Psychol Rev. 2023;52:563–85. 10.1080/2372966X.2021.2024767. [Google Scholar]