Abstract

5-Methylcytosine (m5C), an important RNA modification, has been extensively studied in colorectal cancer (CRC). In recent years, with advances in high-throughput sequencing technology and RNA modification detection tools, the role of m5C modification in tumorigenesis and development has been gradually elucidated and regulated by “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers,” m5C modification affects many biological processes and cancer progression, including cell proliferation, autophagy, invasion, and apoptosis. In CRC, m5C modification affects cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, drug resistance, and immunotherapy resistance by regulating RNA stability, metabolic reprogramming, signalling pathway activation, and immune escape. Moreover, m5C modification provides potential biomarkers and targets for early diagnosis and efficacy prediction. In addition, studies on drugs that target m5C modification related proteins have shown that intervention in m5C modification may provide new directions for immunotherapy and molecular therapy for patients with CRC. In summary, m5C modification, an important epigenetic regulators in CRC, provides a new perspective on the mechanism underlying cancer therapy and precision medicine research. Future research should focus on revealing the specific role of m5C modification in the tumor microenvironment and drug resistance mechanisms and promote its clinical translation in diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, RNA 5-methylcytosine (m5C), NSUN2, DNMT2, Early diagnosis, Targeted therapy

Introduction

5-Methylcytosine (m5C) RNA methylation, a critical epitranscriptomic regulatory mechanisms, has aroused widespread interest in the field of oncology research with the rapid advancement of high-throughput sequencing technology and precise development of RNA modification detection methods [1]. This modification is catalyzed by m5C methyltransferases (writers), while the demethylation process is regulated by demethylases (erasers), and specific recognition proteins (readers) can interact specifically with m5C-modified bases through specific domains, thereby exerting their functions [2]. m5C modification is widely present in various RNA molecules, including mRNAs, tRNAs, rRNAs, and lncRNAs [3], and forms a sophisticated regulatory network that regulates RNA structural stability, splicing maturation, subcellular localization, and translation efficiency. Recent studies have revealed that m5C modification not only participates in maintaining basic cellular physiological functions but also plays a key regulatory role in disease progression in particulars, it exhibits multi-dimensional carcinogenic regulatory characteristics in the processes of tumorigenesis and development.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common and deadly cancer worldwide, with its mortality second only to that of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 10% of global cancer cases and related deaths annually [4]. Due to the continuous optimization of multimodal treatment strategies, the overall survival time of patients with advanced disease has increased in recent years to approximately 3 years [5]. The occurrences of colorectal cancer had accompanied by a series of molecular events, such as gene mutations, epigenetic modifications, and changes in the tumor microenvironments. Recent studies have shown that RNA methylation plays key regulatory roles in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer [6]. Among these modifications, m5C modification exerts significant carcinogenic effects by regulating malignant phenotypes, such as tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and drug resistance. m5C modification can drive malignant tumor progression by affecting gene expression, altering the activity of intracellular signalling pathways, and even regulating the function of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment [7]. m5C RNA methylation not only participates in RNA metabolism regulation but also exacerbates the malignant phenotype of colorectal cancer through mechanisms such as promoting tumor progression and inducing resistance to immunotherapy [8–10]. Notably, the level of m5C modification of RNA is closely related to the activation state of T cells [11], suggesting that it may serve as a potential biomarker for immune checkpoint blockade therapies, providing a new research direction for precision cancer immunotherapies.

In summary, m5C RNA methylation is not only deeply involved in the core biological processes of malignant transformation and tumor progression in colorectal cancer cells but also serves as a key epigenetic marker for tumorigenesis and developments. With an in-depth understanding of the dynamic regulatory network and molecular mechanisms of m5C modification, this system has expected to provide innovative diagnostic and therapeutic directions for molecular subtyping, early diagnostic marker screening, and targeted therapy strategy development for colorectal cancer. Therefore, systematic analysis of the regulatory mechanism and clinical translational values of m5C RNA methylation in colorectal cancer will strongly promote the innovation and optimization of precision treatment systems for this disease.

m5C RNA modification occurrence and regulatory mechanisms

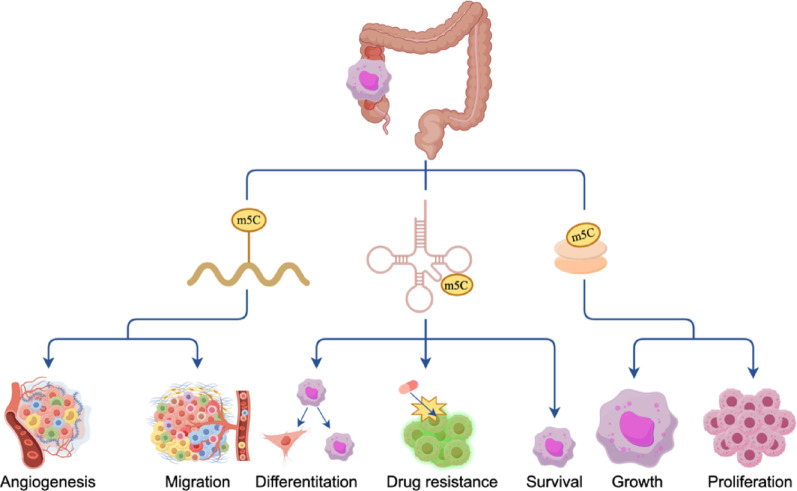

m5C RNA modification first discovered in the 1970s [12], and early studies focused on the modification of rRNA and tRNA [13]. In recent years, with the innovation of high-throughput sequencing technology and improvements in epitranscriptomic research, the role of m5C in mRNAs, lncRNAs (long non-coding RNA) and other noncoding RNAs has been gradually elucidated [14–17], and its core role in post-transcriptional regulations have become increasingly prominent. m5C modification has widely distributed in RNA molecules such as tRNAs, rRNAs, mRNAs and lncRNAs. In tRNAs, m5C modifications are situated in the anticodon loop, TΨC (specific structural element within tRNA) loop and D loop region [18], which plays a key role in maintaining tRNA structural stability and its functional integrity in rRNAs, m5C modifications help to stabilize rRNA folding and maintain its structural integrity, processing, and ribosome biogenesis [19], in mRNAs, m5C modifications are most common in the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) and can also be distributed in the coding region (CDS) and 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) [20], dynamically regulating RNA stability and translation; and in lncRNAs, m5C modifications also affect stability and regulatory function [21]. m5C modifications in different RNA molecules jointly regulate RNA stability, RNA function, and cellular biological processes, thereby affecting various aspects of colorectal cancer progression (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

m5C RNA modification occurrence and regulatory mechanisms. By Figdraw

Methyltransferases (writers)

The m5C modification of RNA has mediated by a class of specific methyltransferases, the NOP2/SUN RNA methyltransferase family (such as NSUN2), tRNA aspartic acid methyltransferase 1 (TRDMT1), and DNA methyltransferase 2 (DNMT2) [2]. These enzymes catalyze the methylation reaction at the C5 position of cytosine to mediate the production of m5C, thereby regulating biological processes such as RNA stability, post-transcriptional modification, splicing, and translation [13]. The NOP2/SUN (NSUN) family is an important RNA methyltransferase family that includes NSUN1, NSUN2, NSUN3, NSUN4, NSUN5, NSUN6, and NSUN7 [22, 23]. This family plays a key role in regulating various cell biological processes, especially the occurrence and development of tumors [24, 25]. Family members contain a key conserved cysteine residue, which binds to the C6 position of the target cytosine through a thiol group to form a covalent intermediate. The formation of this intermediate makes the carbon at the C5 position of cytosine active, after which the methyl group has transferred from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the C5 position to form 5-methylcytosine[26], thereby regulating the methylation status of RNA.

The reported human homolog TRDMT1 is highly like DNMT2 in sequence and function, and both participate in m5C modification in tRNA molecules [27]. Due to their close associations with structure and function, TRDMT1 and DNMT2 are regarded as the same methyltransferase [28, 29] in academia. DNMT2 is a unique DNA methyltransferase that differs from classical DNMT family members (such as DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B) in structure and function [30]. DNMT2 was initially considered a typical DNA methyltransferase, but subsequent studies revealed that DNMT2 has dual substrate specificity [31], and its main function is not to directly add methyl groups to DNA but to methylate RNA molecules through its methyltransferase activity, especially m5C methylation of tRNA [32].

Recent research advances have revealed more key enzymes involved in RNA m5C methylation modification. Methyltransferases such as METTL17 [33] and the METTL3/14 complex have been shown to play crucial roles in RNA m5C methylation modifications. Studies have shown that METTL3 forms a heterodimer with METTL14 to catalyze the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification of p21 mRNA, whereas NSUN2 is responsible for catalyzing its m5C modification. The two act together on the p21 3′ UTR, promoting each other to regulate intracellular gene expression and protein synthesis processes [34]. In summary, these m5C RNA methylation modification enzymes regulate RNA m5C modification, not only maintaining basic cell functions but also playing a core regulatory role in tumor evolution [35]. Systematic analysis of the multidimensional regulatory network of these enzymes and their mechanism of action in the tumor microenvironment will provide key theoretical support for the development of novel targeted therapies.

Demethylases (erasers)

m5C RNA demethylases are important enzymes that regulate RNA modification status, mainly by removing m5C modifications from RNA molecules and restoring their original cytosine state [36]. Typical m5C demethylases include Ten-Eleven Translocation family enzymes (such as TET1, TET2, and TET3), AlkB homolog 1 (ALKBH1), and fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) [37]. These enzymes regulate RNA stability, post-transcriptional modification, translation, and gene expression through demethylation and play important roles in cell differentiation, stress response, and tumorigenesis [2]. TET family enzymes are currently the most widely studied class of m5C demethylases. TET family enzymes introduce an oxygen molecule at the carbon 5 position of m5C through oxidation reactions, generating 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) [38], 5-formylcytosine (5-fC), 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC) and other oxidation products. 5-hmC, 5-fC, and 5-caC can be further repaired or removed, leading to the removal of m5C [39]. Therefore, the role of TET enzymes are to gradually oxidize m5C, causing it to eventually return to unmethylated cytosine.

In contrast, the AlkB homolog (ALKBH) family of enzymes, another class of important m5C demethylases, has a unique demethylation mechanism [40]. Unlike the oxidation mechanism of the TET family, ALKBH family enzymes (such as ALKBH1 and ALKBH5) catalyze the demethylation of m5C by relying on Fe2⁺ and α-ketoglutarate as cofactors [41]. These enzymes can restore RNA molecules to them unmodified cytosine form by catalyzing the demethylation reaction of m5C. Unlike TET enzymes, the demethylation process of ALKBH family enzymes does not involve oxidative intermediates but achieved by directly removing methyl groups [42].

FTO is a widely expressed demethylase that was initially discovered for its association with obesity [43]. As an α-ketoglutarate-dependent demethylase, FTO can remove methyl modifications on RNA molecules, particularly m6A modifications [44]. However, recent studies have found that although FTO does not directly participate in the m5C modification process, in terms of chromatin regulation, FTO affects the m6A modifications of RNAs such as Long Interspersed Nuclear Element 1 (LINE1) [45] and may participate in the regulation of the chromatin state together with m5C modification. In recent years, the roles of m5C methylases such as NSUN2 in RNA epigenetics and CRC have depicted in detail [9, 10, 46]. However, the molecular regulatory mechanisms of m5C demethylases in colorectal cancer were poorly understood yet. Current research focuses predominantly on other epigenetic modifiers, such as TET family enzymes in myeloid leukaemia (as DNA demethylases) [47, 48], or ALKBH family members and FTO in lung cancer via m6A modulation [43, 49]; however, there is still a lack of systematic research on the specific regulatory network of RNA m5C demethylases in the occurrence and development of CRC. Therefore, in-depth elucidation of the molecular mechanism of RNA m5C demethylases in the malignant transformation and evolution of CRC can not only expand the theoretical system of tumor epigenetic regulation but also provide a theoretical basis for developing precision treatment strategies based on the dynamic regulation of RNA methylation.

Readers

m5C RNA modification reader proteins are important cellular regulators that can specifically recognize and bind to RNA molecules containing m5C modifications, thereby regulating their stability, posttranscriptional modification, translation, nucleocytoplasmic transport, and other biological processes [50–52]. Representative reader proteins include Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1), ALY/REF export factor (ALYREF), and YT521-B homology domain-containing family protein 2 (YTHDF2) [53–55]. YBX1 is an important multifunctional RNA-binding protein that interacts with m5C through the key residue Trp45 in its cold-shock domain (CSD) to specifically recognize m5C modification sites [56], thereby widely participating in the regulation of RNA stability, posttranscriptional modification, nuclear export, translation, DNA repair, and other processes. In CRC cells, YBX1 participates in regulating cell proliferation, migration, drug resistance, and other biological processes by binding to m5C-modified RNA [9].

ALYREF, the first identified m5C reader, forms the TREX complex (transcription/export complex) with the THO subcomplex and RNA helicase UAPS6 [57]. It recognizes m5C-modified RNA via its Lys171 (K171) residue [58]. ALYREF is closely related to RNA transport and can specifically recognize and bind to m5C-modified RNA, promoting its efficient transport from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [59]. This process plays a vital role in biological processes such as the posttranscriptional regulation, splicing [60], and translation of RNA. In particular, regulating the nucleocytoplasmic transport of m5C-modified RNA, ALYREF ensures that these modified RNAs can easily enter the translation process by binding to them, thereby participating in intracellular protein synthesis and functional regulation [61]. In addition, ALYREF also regulates the expression of genes related to cell proliferation and cancer development by influencing RNA stability and splicing [62, 63]. Research has shown that ALYREF has an important influence on the occurrence and progression of CRC [59].

Initially, YTHDF2 was considered an m6A-binding protein [64]. Upon binding to m6A-modified mRNA, it recruits related degradation enzymes or complexes, thereby accelerating mRNA degradation, reducing mRNA stability, decreasing its abundance within cells, and consequently affecting gene expression levels [65]. Emerging evidences has shown that YTHDF2 recognizes both m5C and m6A via a shared binding pockets [64, 66]. However, binding to m5C requires the cooperative participation of all five key amino acids (W432, W486, Y418, D422, and W491), whereas binding to m6A only relies on two of them (W432 and W486) [67]. This differentiated binding pattern enables dual regulation of mRNA stability, providing a molecular basis for the dynamic balances of the epitranscriptome.

m5C RNA reader proteins play essential roles in RNA stability, post-transcriptional modification, nuclear export, and translation [68–70]. In the occurrence and development of CRC, these reader proteins may promote the proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells by regulating the expression of tumor-related genes [10]. Future in-depth research on the mechanism of action of m5C reader proteins will not only help elucidate the molecular basis of CRC but also provide new directions for targeted cancer therapy.

Impact of m5C modification on the biological functions of CRC cells

m5C RNA modification plays a pivotal role in the biological functions and activities of CRC cells by dynamically regulating RNA metabolism and functional networks (Fig. 2). Studies have demonstrated that m5C RNA modification not only drives core malignant phenotypes—such as cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and immune evasions through the targeting of specific RNA molecules but also promotes malignant phenotypic transformation by altering metabolic homeostasis, fine-tuning posttranscriptional processing, and coordinating crosstalk between signalling pathways (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

The role of m5C RNA modification in colorectal cancer. By Figdraw

Table 1.

The mechanism and function of m5C RNA modification in colorectal cancer

| Factor/enzyme | Type | Target RNAs and m5C sites | Functions | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSUN2 | Writers | ENO1 mRNA | Promotes the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer | Regulates of glycometabolic reprogramming through the NSUN2/YBX1/m5C-ENO1 positive feedback loop | [10] |

| SKIL mRNA | Promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration | Enhances SKIL mRNA stability and activates the TAZ signaling pathway | [9] | ||

| mRNA | Promotes nuclear export of m5C-modified mRNA | [61] | |||

| TREX2 mRNA | Promotes tumorigenesis and resistance to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy | Maintains TREX2 m5C methylation and mRNA stability to inhibit cGAS/STING pathway activation | [71] | ||

| tRNA-Arg C34 site | Regulates EMT process and enhances cell migration and invasion abilities | Protects tRNA-Arg from endonuclease cleavage, promoting the accumulation of pro-transfer tRFs | [8] | ||

| SLC7A11 mRNA | Promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and inhibits ferroptosis | Methylation of SLC7A11 mRNA enhances the stability and translation efficiency of the mRNA | [72] | ||

| mRNA | Promotes the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer | Regulates of mRNA stability and translation | [73] | ||

| NSUN4 | Writers | NXPH4 mRNA | Promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of tumor cells | Methylation of NXPH4 mRNA activates the HIF signaling pathway | [74] |

| NSUN5 | Writers | Peripheral blood immune cells | m5C is a biomarker for the noninvasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer | Upregulation of NSUN5 and YBX1 expression promotes m5C modification | [75] |

| Promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation | Regulates the cell cycle through the Rb-CDK4/6-CCNE1 pathway | [76] | |||

| circ_0102913 | Promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of colorectal cancer cells | Promotes tumor progression by activating downstream signaling pathways through the miR-571/RAC2 axis | [77] | ||

| NSUN6 | Writers | METTL3 mRNA | Overexpression of METTL3 promotes G1/S phase transition in colorectal cancer cells | Promotes the cell cycle and proliferation of colorectal adenocarcinoma cells | [78] |

| METTL17 | Writers | mt-RNA | Regulates mitochondrial translation function and inhibits ferroptosis | Promotes resistance to ferroptosis and tumor proliferation and migration in colorectal cancer cells | [33] |

| ALYREF | Readers | mRNA | Promotes the nuclear export and expression of target mRNA in synergy with ELAVL1 | Promotes the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer | [59] |

| mRNA | Specifically binds to m5C-modified mRNA, promoting mRNA nuclear export | [61] | |||

| YBX1 | Readers | ENO1 mRNA | Participation in the NSUN2/YBX1/m5C—ENO1 positive feedback loop | Promotes the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer | [10] |

Role of m5C modification in CRC cell proliferation and apoptosis

The role of m5C RNA modification in CRC cell proliferation has been extensively investigated. As key "writer" enzymes of m5C methylation, NSUN family members (Particularly NSUN2) play critical regulatory roles in tumor progression [79]. Clinical data analysis revealed that the transcription level and protein expression of NSUN2 are significantly upregulated in CRC tissues and are positively correlated with malignant phenotypes such as increased tumor diameter and TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) stage progressions [10, 74, 80]. These findings suggest that NSUN2 may act as an oncogenic driver in CRC initiation and progression. In depth mechanistic studies demonstrated that the RNA m5C methyltransferase NSUN2 regulates tumor metabolic reprogramming by specifically mediating m5C epitranscriptomic modifications on the mRNA of enolase 1 (ENO1) [10], a key glycolytic enzyme. Notably, the regulatory association between m5C modification and ferroptosis has become important directions in the field of tumor research. The team led by Ruibing Tong constructed an NSUN2 conditional knockout model, revealing that this enzyme not only regulates CRC cell proliferation but also dynamically modulates the stability and translational efficiency of solute carrier family 7-member 11 (SLC7A11) mRNA through m5C methylation, thereby determining tumor cell ferroptosis sensitivity [72]. This discovery highlights the potential roles of m5C modification in ferroptosis regulation and provides novel insights for future research. Further studies indicated that in CRC, the RNA methyltransferase NSUN4 enhances the stability of neurexophilin 4 (NXPH4) mRNA via m5C modification. The NXPH4 protein competitively binds to prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing protein 4 (PHD4), inhibiting its hydroxylation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α). This blockade prevents HIF-1α ubiquitination and degradation, activating the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signalling pathway and driving malignant behaviours such as tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [74].

At the mechanistic level of m5C modification, the core reader proteins YBX1 and ALYREF exhibit critical regulatory functions. Molecular mechanism studies have shown that YBX1 significantly enhances the stability and promotes the translation efficiencies of ENO1 mRNA by specifically recognizing its m5C-modified sites, thereby regulating metabolic processes linked to CRC cell proliferation [10]. Another study revealed that NSUN2 maintains SKI-like oncogene (SKIL) mRNA stability through m5C modification in a YBX1-dependent manner, promoting upregulation of the expressions of this gene in colorectal cancer cells [9]. Previous mechanistic investigations confirmed that SKIL competitively binds to large tumor suppressor homolog 2 (LATS2), a key component of the Hippo pathway, inhibiting transcriptional coactivators with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention, thereby enhancing the transcriptional activation of TAZ-mediated cell proliferation, survival, and migration-related genes [81]. In addition, as another important m5C modification reader protein, ALYREF has been shown to specifically bind m5C-modified sites on ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-2 (RPS6KB2) and regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (RPTOR) mRNAs. By promoting their nucleocytoplasmic transport efficiency and translational activity, ALYREF amplifies the oncogenic effects of these two key mechanistic targets of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway components in CRC [59]. Notably, ALYREF also stabilizes the HIF-1α protein, enhancing tumor cell adaptation to hypoxic microenvironments. This process may facilitate the expression of glycolysis-related genes, driving tumorigenesis and progression [82].

In summary, m5C RNA modification plays a central role in CRC metabolic reprogramming, cell cycle regulation, and oncogenic signalling pathway activation by dynamically regulating the transcript stability, subcellular localization, and translational activities of key oncogenes. Current research focuses mostly on the functional analysis of single methylases or recognition proteins, and systematic elucidations of the global role of the m5C modification network and multidimensional epigenetic interaction mechanisms are lacking, which limits its application and transformations in early clinical diagnosis. Future research needs to integrate spatial transcriptomics (ST), single-cell epigenomics (SCE), and dynamic methylation sequencing (DMS) technologies to systematically elucidate the spatiotemporal specific regulatory patterns of m5C modification and its crosstalk mechanisms with other types of epigenetic forms. Such efforts will lay a theoretical foundation for developing RNA epigenetics-based precision diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Role of m5C modification in CRC cell migration and invasion

m5C RNA modification dynamically regulates the epitranscriptome to participate in the pathological processes of CRC cell migration and invasion. Current studies on the roles of m5C RNA modification in CRC metastasis have focused primarily on phenotypic validations at the cellular level [9, 10, 71], while the analysis of deep molecular mechanisms are still insufficient. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a core mechanism of tumor metastasis, is significantly associated with m5C modification. Luan and colleagues reported that NSUN2 overexpression induces the upregulation of mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin and Vimentin), EMT transcription factors (ZEB1, Slug, and Snail), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2/3/7/9) while suppressing the epithelial marker E-cadherin, thereby driving mesenchymal traits and enhancing invasion in colon cancer cells [8]. These findings suggest that m5C modification may co-ordinately promote tumor metastasis by remodelling cytoskeletal dynamics, regulating cell adhesion molecule expression, and activating EMT programs. Notably, studies in other cancers have revealed pan-tumor mechanisms involving the m5C system. For example, NOP2 enhances enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) mRNA stabilities through ALYREF-mediated m5C modification, leading to H3K27me3-dependent epigenetic silencing of the E-cadherin promoter and promoting EMT in lung cancers [83]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) LINC00618 upregulates sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) m5C modification levels by inhibiting NSUN2 ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation, thereby providing metabolic support for tumor cell growth and driving HCC proliferation, migrations, and EMT [84].

m5C modification further promotes metastasis by regulating oncogenic signalling pathways and metabolic reprogramming. Studies have demonstrated that the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) NMR methylated by NSUN2 activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signalling axis, inducing the expression of key effector molecules such as matrix metalloproteinase 3/matrix metalloproteinase 10 (MMP3/MMP10) to enhance the invasive capacity of oesophageal cancer cells [85]. Additionally, Sylvain Delaunay et al. revealed that mitochondria-associated m5C/f5C modifications significantly increase the potential of cancer cells to breach the extracellular matrix and establish distant colonization by accelerating oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) metabolic rates, underscoring the critical role of m5C RNA modification in tumor metastasis [86].

Recent studies have proposed that m5C modification also enhances cancer cell adaptability and growth by modulating interactions between tumor cells and target organ microenvironments, thereby driving metastasis and progression [87]. Although current research has partially deciphered the mechanisms of m5C in tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, significant gaps remain in understanding organ-specific metastasis and microenvironmental regulation in CRC. Insights from other cancers provide valuable clues for unravelling CRC metastasis mechanisms. Given that CRC metastasis is a leading cause of patient mortality [88], its progression is likely finely regulated by dynamic m5C modification networks. Systematically elucidating the epigenetic regulatory principles of m5C in CRC organ-specific metastasis and microenvironment remodelling will offer novel perspectives for developing RNA epitranscriptome-based early diagnostic biomarkers, prognostic evaluation systems, and targeted therapeutic strategies.

Role of m5C modification in CRC immune escape

Immune escape is one of the critical mechanisms by which tumor cells evade eliminations by the host immune system [89]. In CRC, tumor cells employ multiple strategies to avoid immune surveillance, including immune checkpoint inhibition, infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, and altered expression of immune escape-related genes [90]. The programmed death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway is one of the major mechanisms by which tumor cells evade immune surveillance [91]. A study on the CRC tumor microenvironment (TME) revealed that m5C-associated lncRNAs may promote the expression of PD-1/PD-L1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) through interactions with immune checkpoint molecules, thereby suppressing T cell activation and dampening immune responses. Furthermore, researchers hypothesize that the differential expression of m5C-related lncRNAs across molecular subtypes alters the TME, influencing T cell infiltration levels. For example, the prognostically favourable subtype B has increased M1 macrophage infiltration, potentially due to m5C-related lncRNAs promoting macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype, which enhances antitumor immunity [16].

Recent studies suggest that m5C-modified lncRNAs may regulate the migration and localization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), modulating their infiltration into the TME. Specifically, MDSCs secrete immunosuppressive factors such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and directly interact with T cells to inhibit effector T cell activity, further facilitating immune escape [92]. NSUN2, the most extensively studied m5C methyltransferase, was recently identified not only as a key RNA modification enzyme but also as a glucose metabolism sensor. Glucose binding enhances NSUN2 activity, sustaining the expression of three prime repair exonuclease 2 (TREX2). TREX2, with its exonuclease activity, degrades cytoplasmic DNA, limiting cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) accumulation and suppressing the activation of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS/STING) pathway, thereby inhibiting downstream interferon production and antitumor immune responses [71, 93]. Additionally, Lu et al. reported that DNMT2 not only influences tRNA methylation but also may indirectly regulate the generation of tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) by altering tRNA splicing or processing. Experiments have shown that the knockdown of tRFs induces G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in CRC cells while promoting M2 macrophage polarization, highlighting the critical role of tRFs in the CRC TME [94].

Although numerous studies have revealed correlations between m5C modification and tumor immune escape, most of these studies are observational and lack mechanistic and theoretical depth. In-depth research on the immune escape mechanism not only helps reveal the complexity of the tumor immune microenvironment but also may provide potential new targets and innovative research directions for tumor treatment.

Potential role of m5C modification in CRC drug resistance

Drug resistance is a major challenge in CRC treatment [95]. Studies suggest that m5C modifications may influence the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes or transporters, altering cancer cell metabolism and efflux capacity toward chemotherapeutic agents. Although current research has not specifically addressed the roles of m5C in CRC drug resistance, insights can be drawn from studies in other cancers. For example, in 5-azacytidine (5-AZA)-resistant leukemia cells, elevated m5C levels are correlated with altered expression of specific RNA cytosine methyltransferases (RCMTs). NSUN1 binds to bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) and RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain serine-2 phosphorylation (RNA Pol II CTD-S2P) in resistant cells, forming a chromatin structure that is resistant to 5-AZA but sensitive to the BRD4 inhibitor JQ1 [96]. In epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI)-resistant cells, NSUN2 stabilizes quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1) mRNA via m5C methylation in its coding sequence, promoting YBX1-mediated recognition and binding to enhance drug resistance [97]. Additionally, the m5C reader YBX1 upregulates chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 3 (CHD3), which enhances chromatin accessibility and homologous recombination, contributing to platinum resistance in ovarian cancer [98].

In CRC, m5C modification enhances glycolysis through multiple mechanisms [10, 71], profoundly impacting cancer cell survival and drug resistance. Enhanced glycolysis not only provides ample energy support for cancer cells but also reduces intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, attenuating ROS-mediated apoptotic signalling [99], which to some extent helps cancer cells evade drug-induced oxidative stress damage. Recent studies have shown that the mRNA expression of methyltransferase-like 17 (METTL17), a key mitochondrial RNA methylation regulator, is positively correlated with cancer cell resistance to glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) inhibitors. METTL17 inhibition impairs mitochondrial respiration, reduces ATP production and glycolysis, triggers lipid peroxidation, elevates ROS, and induces mitochondrial damage and cell cycle arrest [33]. Conversely, METTL17-mediated metabolic and antioxidant enhancements counteract GPX4 inhibitor-induced lipid peroxidation, underscoring the critical role of m5C in drug resistance.

Although m5C-related drug resistance mechanisms have been validated in other cancers, research in CRC remains inadequate. Systematic exploration of its role across therapies (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy) are lacking. Future studies should focus on elucidating multidimensional m5C mechanisms in CRC drug resistances, particularly through preclinical models and clinical cohorts, to provide theoretical and experimental foundations for its potential clinical application.

Potential of m5C RNA modification in CRC prognosis and clinical evaluation

The exploration of molecular biomarkers for early diagnosis and precision therapy in CRC has become a major research focus. As a pivotal RNA epitranscriptomic modification, m5C RNA modification has increasing potential for use in clinical diagnosis and condition assessment (Table 2). Multiple clinical cohort studies have confirmed that NSUN2 expression is significantly correlated with tumor size and TNM stages in CRC and that NSUN2 levels decrease markedly after radical treatment [10, 75, 100]. Haofan Yin et al. evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of m5C modification in peripheral blood immune cells for CRC by distinguishing and reclassifying them. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for m5C-based diagnosis reached 0.888 and 0.909 in the training and validation cohorts, respectively, outperforming traditional biomarkers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9), and carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125). Combined detection further improved diagnostic performances, with multivariate analysis identifying m5C and CEA as independent risk factors [75].

Table 2.

m5C-related modifications in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer

| References | Study type | Population | Biomarkers | Grouped control | Screening models (AUC, sensitivity, specificity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [80] | Retrospective cohort study |

TCGA: 434 COAD 157 READ IHC: 80 Normal 80 READ |

NSUN4, NSUN7, DNMT1 | Normal/COAD/READ |

TCGA cohort: AUC of one-year OS = 0.803 AUC of three-year OS = 0.855 AUC of five-year OS = 0.838 AUC of overall survival = 0.834 IHC independent cohort: AUC = 0.954 |

| [100] | Retrospective cohort study and case‒control study |

TCGA: 616 CRC ZNa: 40 Normal 40 CRC |

18 m5C regulatory factors | High-/low-risk groups |

TCGA cohort: AUC of one-year OS = 0.638 AUC of three-year OS = 0.668 AUC of five-year OS = 0.719 Nomogram model: AUC of one-year OS = 0.783 AUC of three-year OS = 0.801 AUC of five-year OS = 0.795 |

| [101] | Retrospective cohort study |

TCGA: 568 CRC 44 Normal |

11 m5C-related lncRNAs | Normal/CRC |

TCGA cohort: AUC of one-year OS = 0.758 AUC of three-year OS = 0.761 AUC of five-year OS = 0.811 |

| [16] | Retrospective cohort study |

TCGA & GEO: 1358 CRC |

21 m6A/m5C-related lncRNAs | High-/low-risk groups |

TCGA cohort: AUC = 0.712 GEO cohort: AUC = 0.721 |

| [75] | Case‒control study and retrospective cohort study |

Human samples: 196 CRC 83 Normal Mouse modelb |

m5C RNA methylation levels in peripheral blood immune cells | Normal/CRC |

m5C: AUC = 0.888, sensitivity 92.4%, specificity 69.8% m5C + CEA + CA19 − 9 + CA125: AUC = 0.937 |

| [102] | Retrospective cohort study | NSUN1 | Normal/CRC | ||

| [103] | Retrospective observational study |

Total: 3318 tumor samples (140 CRC) 5173 Normal |

14 m5C-related miRNAs | Normal/CRC |

Early diagnosis: AUC = 0.910 Diagnostic performance: AUC = 0.934, sensitivity 82.9%, specificity 91.6% |

aRepresents Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University cohort; bincludes ① MC38 Syngeneic model: 5 C57BL/6 control mice, 4 tumor-bearing mice ② AOM/DSS model: 5 C57BL/6 control mice, 8 CRC-induced mice ③ Apc-L850X model: 5 wild-type mice, 5 mutant mice ④ DLD-1 Xenograft model: 4 BALB/c control mice, 5 Oxaliplatin-treated mice, 4 5-FU-treated mice

Compared with single modifiers or gene-specific changes, constructing a comprehensive diagnostic model based on multiple m5C modification targets is clearly a more sensible choice [104]. Ziyang Di et al. developed an 11-lncRNA risk model using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). This model revealed distinct immune cell infiltration patterns between the high- and low-risk groups, such as increased CD56dim natural killer cells and reduced T cell subsets in high-risk patients. The risk score correlated with the immunotherapy response and differential activation of six immune-related pathways [101]. Similarly, Rixin Zhang et al. constructed a risk model based on LASSO Cox regression analysis to screen 3 m5C regulatory genes (DNMT1, NSUN4, NSUN7) related to the prognosis of rectal adenocarcinoma. The constructed risk model was verified in many aspects and can be used as an independent prognostic factor to effectively distinguish the prognosis of patients. The low-risk group showed strong immune reactivity and immune therapeutic response advantages and was more sensitive to a variety of drugs [105], underscoring the interplay between cancer and immunities.

Furthermore, m5C and m6A modifications are not independent risk factors but exhibit synergistic interactions [34]. Therefore, the idea of combining m6A- and m5C-related modification targets for analysis arises. In the latest research, researchers identified m6A and m5C regulators based on published data, analyzed the correlation between lncRNAs and regulator expression, screened 7 lncRNAs to construct a prognostic model, and verified its predictive ability in different cohorts [16]. Additionally, elevated m5C levels in the 3′ UTRs of transcripts have been linked to CRC liver metastasis, suggesting its predictive value [106].

However, current methodologies for detecting m5C modifications, such as bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq), m5C RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (m5C-RIP-seq), 5-azacytidine-mediated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (Aza-IP-seq), and methylation-individual nucleotide resolution crosslinking immunoprecipitation sequencing (miCLIP-seq) [107], face significant challenges for clinical translation. Although these techniques have achieved success in laboratory research, clinical diagnostics demand highly sensitive, rapid, and cost-effective assays. Existing methods are limited by operational complexity, high costs, and time-intensive procedures. Furthermore, in the current diagnostic studies of m5C modification for CRC, most studies have focused on the analysis of late-stage cancer, with few studies focusing on complete evolutions from the initial stage to the late stage of cancer. There are still many questions to be answered by relevant studies on early precancerous lesions and early cancers. Therefore, future research should focus on the discovery and application of early biomarkers for CRC and promote the use of m5C modifications in the early diagnosis of cancer.

Therapeutic potential of targeting m5C RNA modifications in CRC

For early-stage CRC, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) enables precise screening and radical treatment [108, 109]. In advanced CRC, radical surgery remains the cornerstone of therapy, with laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery recommended as the standard approach in international guidelines due to its postoperative recovery advantages [5]. Additionally, comprehensive treatment frameworks based on tumor staging and molecular subtyping includes neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, local ablation of metastases, and systemic chemotherapies. Targeted therapies such as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) monoclonal antibodies [110], cetuximab [111], and panitumumab [112] have also been integrated into clinical practice.

Despite advances in early CRC screening, most cases are diagnosed at intermediate or advanced stages, where surgery remains the optimal therapeutic option [113]. Notably, approximately 25% of newly diagnosed patients present with distant metastases [114], significantly limiting surgical accessibility. Molecular targeted therapy, first conceptualized in the early twentieth century and expanded into oncology in 1988 [5], has achieved remarkable progress. This approach disrupts tumor proliferation, differentiation, migration, or tumor microenvironment (TME) regulation by specifically targeting cancer cells. For example, monoclonal antibodies or small-molecule inhibitors suppress cell surface receptors or membrane-bound sites, offering promising therapeutic avenues for treating CRC [115].

As a focus of recent research, NSUN family enzymes drive CRC progression by modulating RNA m5C modification, which affects gene expression, cell cycle regulation, translation, and drug resistance. NSUN1 and NSUN2 have emerged as novel therapeutic targets [26]. Recent studies have validated NSUN inhibitors in preclinical models. Baoxiang Chen et al. screened compounds using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay and identified Nsun2-i4 as a potent NSUN2 inhibitor. In an azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium (AOM/DSS)-induced CRC mouse model, Nsun2-i4 significantly suppressed tumor growth and overall tumor burdens. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased activation of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathway in treated mice. Compared with monotherapy, combining Nsun2-i4 with programmed death-1 (PD-1) blockades synergistically enhance antitumor efficacy [10], suggesting novel combinatorial strategies for CRC immunotherapy.

DNA methyltransferase inhibitors also play important roles in m5C RNA-targeted therapies [116], suggesting new ideas and hope for the treatment of diseases such as cancer. As research into RNA modifications and disease mechanisms has advanced, the role of these inhibitors have become increasingly prominent. Azacytidine and decitabine, classical DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, play critical roles in cancer therapy [117]. Previous studies revealed that azacytidine inhibits tRNA aspartic acid (tRNA Asp) methylation at cytosine 38 (C38) by suppressing the RNA methyltransferase DNMT2. Interestingly, decitabine, another DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, did not have this effect. Researchers have further reported that azacitidine is more sensitive to tRNA methylation than to DNA methylation [118]. These findings provide evidence for the unique mechanistic roles of m5C-targeted therapies.

The function of TET enzymes is particularly crucial in cancer, as their expression and activity are frequently downregulated in malignancies, including CRC. The development of drugs to enhance or restore TET activity represents promising therapeutic avenues. For example, Yuji Huang et al. reported significant downregulation of TET1 in CRC tissues and cell lines, leading to suppressed WNT signalling pathway activity and reduced tumor-suppressive functions, ultimately promoting tumor growth [119]. Concurrently, nuclear-cytoplasmic mislocalization of TET2 was linked to increased CRC aggressiveness. The nuclear export inhibitor leptomycin B (LMB) prevents aberrant TET2 translocation, restoring 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) levels and tumor suppressor gene expression [120]. Notably, two months later, Yu Zhang et al. reported elevated transcriptional levels of TET1, TET2, and TET3 in 40 CRC tissues and cell lines compared with those in normal controls. Knockdown of TET family members in SW620 cells via short hairpin RNA (shRNA) significantly reduced proliferation and invasion. Consequently, they developed microRNA-506 (miR-506) to target the TET family and inhibit CRC progression [120].

METTL17, a member of the methyltransferase-like family localized to mitochondria, is closely associated with mitochondrial function, ferroptosis, and tumorigenesis. Recent studies have demonstrated that METTL17 depletion induces mitochondrial dysfunction, disrupts the cellular redox balance, sensitizes cells to ferroptosis, and reduces RNA methylation levels (including m5C) without altering mRNA abundance. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of combining METTL17 knockdown with the ferroptosis inducer ML162 for the treatment of CRC with METTL17 [33]. As mentioned earlier, m5C-associated long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) may promote immune evasion by upregulating PD-1/PD-L1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4). A recent study demonstrated that engineered interferon-alpha lentivirus (IFNαLV) combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies significantly enhanced antitumor efficacies in CRC by modulating T-cell subsets, improving antigen presentation and overcoming therapeutic resistance [121].

RNA modifications play pivotal roles in cellular metabolism and disease progression. With advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies, the precision and sensitivity of RNA modification detection continue to improve, enabling deeper mechanistic insights. While multiple compounds targeting the m6A pathway are under preclinical evaluations [122], therapies targeting m5C (Fig. 3) remain largely exploratory. This field remains underexplored, necessitating further research to develop innovative strategies for cancer treatment.

Fig. 3.

m5C RNA modification-based targeted therapy for colorectal cancer. By Figdraw

Discussion

The molecular association between m5C RNA modification and CRC has been progressively elucidated with advances in epitranscriptomics. Researchers have studied m5C in RNA for nearly 70 years [123], accompanied by continuous innovations in detection technologies. Since the 1990s, BS-seq has been widely used for DNA m5C detections [124]. Over the next three decades, RNA-specific BS-seq methods were developed by designing primers for distinct RNA species [125], followed by ultrafast bisulfite sequencing (UBS-seq) [126] and bisulfite-free, base-resolution m5C detection (m5C-TAC-seq) [127]. However, these methods face limitations in terms of sensitivity and inability to distinguish m5C from 5hmC. Recently, m5C RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (m5C-RIP-seq) has increased the detection efficiency for low-abundance RNAs via antibody-based enrichment [128]; however, its application is constrained by antibody specificity and modification-type resolution. 5-Azacytidine-mediated RNA immunoprecipitation (Aza-IP) has been successfully applied to the study of DNMT2 and NSUN2, significantly increasing the candidate pool of NSUN2 target sites, providing important clues for studying the role of RNA methylation in cellular processes and diseases [129, 130] but compromising RNA integrities. To achieve single-base resolution, methylation-individual nucleotide resolution crosslinking immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) combines high throughput sequencing with immunoprecipitation, enabling precise mapping of NSUN2-mediated m5C sites via crosslink-induced mutations [131]. However, its universality is limited by the development of other methyltransferase mutation systems, and further promotion requires new RNA cytidine methyltransferase mutation designs. As high-throughput technologies continue to expand epigenomic data, current analytic approaches remain challenged by limitations in cost, sensitivity, resolution, and modification coverage, highlighting the need for more scalable and precise computational frameworks.

As a key posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism, m5C RNA modification has oncogenic properties that drive CRC initiation, progression, and metastasis [33, 59, 100]. Its reversibility, spatiotemporal dynamics, and microenvironment dependency make it a central focus of CRC epitranscriptomics [132, 133]. This review systematically delineates the biological roles and clinical potential of m5C in CRC, particularly its multidimensional mechanisms that promote malignancy. Widespread across RNA species, m5C regulates RNA stability, posttranscriptional processing, and translation efficiency. Mechanistically, m5C drives CRC proliferation and invasion by dynamically stabilizing oncogenic transcripts and enhancing their translation [10]. It significantly enhances tumor immune escape ability by remodeling the tumor immune microenvironments, especially by regulating the activation status of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint signalling pathway [71]. In terms of the development of drug resistance, m5C significantly enhances the resistance of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs by regulating the expression of drug efflux pump genes [134] and the activity of key rate-limiting enzymes in glycolysis [10], further increasing the complexity of treatment.

Although current research has elucidated the oncogenic mechanisms and therapeutic potentials of m5C modification in colorectal cancer [107], its molecular structural characteristics have not been fully resolved. Existing mechanistic studies have not systematically elucidated the dynamic regulatory network of this modification in different RNA subtypes and the tumor microenvironment, especially the synergistic effects with m6A modification, DNA methylation and other epigenetic regulatory systems [16, 135], and a systematic regulatory model has not been established. In addition, developing epigenetic therapies faces challenges, targeted intervention of specific epigenetic regulators (such as NSUN2 or TET enzymes) may trigger multi-pathway regulatory effects, significantly increasing off-target risks and leading to great challenges in optimizing treatment regimens. Notably, the low abundance of m5C modifications in colorectal cancer significantly increases the difficulty of developing targeted inhibitors [136]. This modification has dynamic and reversible biological properties, and its action sites are mostly located in spatially complex or functionally sensitive regions [86], which imposes strict requirements for the spatiotemporal targeting and action precision of drugs.

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL), has become a valuable asset in overcoming some of these analytical challenges. In m5C research, AI enables efficient interpretation of high-throughput data and the identification of novel regulatory signatures [137–139]. DL frameworks such as Deepm5C and m5C-Seq have significantly improved the accuracy of m5C site prediction [140, 141]. In CRC, AI has been applied to early diagnosis, molecular subtyping, treatment prediction, and prognostic evaluation [142–144]. Pienkowski et al. developed a multimodal variational autoencoder that integrates whole-exome and transcriptomic sequencing data. This approach enables the matching of tumor samples with appropriate cell lines, offering a novel strategy for the discovery of therapeutic targets in precision oncology [145]. In addition, Bao et al. proposed the Colorectal Cancer Immune Module-Network (CCIM-Net), a DL-based model that incorporates multi-omics data to predict chemotherapy response [146]. Looking ahead, integrating AI with m5C epitranscriptomic profiling holds great promise for advancing CRC diagnostics, optimizing treatment strategies, and enabling more personalized clinical decision-making.

In conclusion, m5C epitranscriptomics offers novel perspectives for exploration of the molecular mechanism underlying CRC and for clinical translation. Deciphering its dynamic regulation and multidimensional networks will deepen our understanding of CRC pathogenesis and lay the foundation for the development of diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapies. Integrating spatial transcriptomics, single-cell epigenomics, and AI-driven analytics promises to advance CRC into a precision medicine paradigm. As a core epitranscriptomic layer, m5C has transformative potential in liquid biopsy biomarker discovery, the elucidation of drug resistance mechanisms, and RNA-targeted drug development, revolutionizing personalized and dynamic colorectal cancer management to improve patient outcomes and ultimately pioneering a new era of CRC management.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Ningbo Municipal Health Commission (Ningbo Top Medical and Health Research Program, Grant No. 2023020612) and the Ningbo Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology (Ningbo Science and Technology Major Project, Grant No. 2023S013).

Abbreviations

- 5-AZA

5-Azacytidine

- 5-caC

5-Carboxylcytosine

- 5-fC

5-Formylcytosine

- 5hmC

5-Hydroxymethylcytosine

- AI

Artificial intelligence

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- ALKBH

AlkB homolog

- ALYREF

ALY/REF export factor

- BS-seq

Bisulfite sequencing

- CA125

Carbohydrate antigen 125

- CA19-9

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- CCIM-Net

Colorectal Cancer Immune Module-Network

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- cGAS/STING

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- DL

Deep learning

- DNMT2

DNA methyltransferase 2

- EGFR-TKI

Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- EMR

Endoscopic mucosal resection

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ENO1

Enolase 1

- ESD

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- FTO

Fat mass and obesity-associated protein

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GPX4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- LATS2

Large tumor suppressor homolog 2

- LINE1

Long Interspersed Nuclear Element 1

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- miCLIP

Methylation-individual nucleotide resolution crosslinking immunoprecipitation

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- mTOR

Mechanistic target of rapamycin

- m5C

5-Methylcytosine

- NSUN2

NOP2/SUN RNA methyltransferase family member 2

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- RIP-seq

RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing

- RPS6KB2

Ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-2

- RPTOR

Regulatory-associated protein of mTOR

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SLC7A11

Solute carrier family 7 member 11

- SKIL

SKI-like oncogene

- TAZ

Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- tRFs

TRNA-derived fragments

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- YBX1

Y-box binding protein 1

- YTHDF2

YT521-B homology domain-containing family protein 2

Author contributions

All authors participated in the research and writing of the manuscript, and Guoliang Ye and Yuping Zhou made key revisions to the knowledge of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ningbo Top Medical and Health Research Program (Grant No. 2023020612) and the Ningbo Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2023S013).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no interest conflicts and agree to publish this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuping Zhou, Email: fyzhouyuping@nbu.edu.cn.

Guoliang Ye, Email: yeguoliang@nbu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Nombela P, Miguel-López B, Blanco S. The role of m6A, m5C and Ψ RNA modifications in cancer: novel therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):18. 10.1186/s12943-020-01263-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen D, Gu X, Nurzat Y, et al. Writers, readers, and erasers RNA modifications and drug resistance in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):178. 10.1186/s12943-024-02089-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song H, Zhang J, Liu B, et al. Biological roles of RNA m5C modification and its implications in cancer immunotherapy. Biomark Res. 2022;10(1):15. 10.1186/s40364-022-00362-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1467–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen B, Scurrah CR, McKinley ET, et al. Differential pre-malignant programs and microenvironment chart distinct paths to malignancy in human colorectal polyps. Cell. 2021;184(26):6262-6280.e26. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han X, Wang M, Zhao YL, Yang Y, Yang YG. RNA methylations in human cancers. Semin Cancer Biol. 2021;75:97–115. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luan N, Cao Y, Sun J, et al. NSUN2-mediated splice site m5C methylation modification promotes the progression of colon cancer through modulating the discrepant cleavage of tRNA-arg. 2021. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-786758/v1

- 9.Zou S, Huang Y, Yang Z, et al. Nsun2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by enhancing SKIL mrna stabilization. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14(3): e1621. 10.1002/ctm2.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen B, Deng Y, Hong Y, et al. Metabolic recoding of NSUN2-mediated m5 C modification promotes the progression of colorectal cancer via the NSUN2/YBX1/m5 C-ENO1 positive feedback loop. Adv Sci. 2024;11(28):2309840. 10.1002/advs.202309840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang WL, Qiu W, Zhang T, et al. Nsun2 coupling with RoRγt shapes the fate of Th17 cells and promotes colitis. Nat Commun. 2023;14:863. 10.1038/s41467-023-36595-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wildenauer D, Gross HJ, Riesner D. Enzymatic methylations: III. Cadaverine-induced conformational changes of Ecoli tRNAfMet as evidenced by the availability of a specific adenosine and a specific cytidine residue for methylation+. Nucleic Acids Res. 1974;1(9):1165–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Vílchez R, Sevilla A, Blanco S. Post-transcriptional regulation by cytosine-5 methylation of RNA. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Gene Regulatory Mech. 2019;1862(3):240–52. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia Y, Pei T, Zhao J, et al. Long noncoding RNA H19: functions and mechanisms in regulating programmed cell death in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1): 76. 10.1038/s41420-024-01832-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang P, Zhang T, Chen D, Gong L, Sun M. Prognosis and novel drug targets for key lncRNAs of epigenetic modification in colorectal cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2023;2023:1–13. 10.1155/2023/6632205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song W, Ren J, Xiang R, Yuan W, Fu T. Cross-talk between m6A- and m5C-related lncRNAs to construct a novel signature and predict the immune landscape of colorectal cancer patients. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 740960. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.740960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma HL, Bizet M, Soares Da Costa C, et al. SRSF2 plays an unexpected role as reader of m5C on mRNA, linking epitranscriptomics to cancer. Mol Cell. 2023;83(23):4239–4254.e10. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motorin Y, Grosjean H. Multisite-specific tRNA:M5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA. 1999;5(8):1105–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao H, Gaur A, McConie H, et al. Human NOP2/NSUN1 regulates ribosome biogenesis through non-catalytic complex formation with box C/D snoRNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(18):10695–716. 10.1093/nar/gkac817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Squires JE, Patel HR, Nousch M, et al. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(11):5023–33. 10.1093/nar/gks144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Z, Xue S, Zhang M, et al. Aberrant NSUN2-mediated m5C modification of H19 lncRNA is associated with poor differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2020;39(45):6906–19. 10.1038/s41388-020-01475-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang T, Zhao F, Li J, et al. Programmable RNA 5-methylcytosine (m5C) modification of cellular RNAs by dCasRx conjugated methyltransferase and demethylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(6):2776–91. 10.1093/nar/gkae110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Zhai X, Liu Y, et al. NOP2-mediated m5C modification of c-Myc in an EIF3A-dependent manner to reprogram glucose metabolism and promote hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Research (Wash D C). 2023;6:0184. 10.34133/research.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Wei J, Feng L, et al. Aberrant m5C hypermethylation mediates intrinsic resistance to gefitinib through NSUN2/YBX1/QSOX1 axis in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:81. 10.1186/s12943-023-01780-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang J, Liu F, Cui D, et al. Novel molecular mechanisms of immune evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: NSUN2-mediated increase of SOAT2 RNA methylation. Cancer Commun. 2025. 10.1002/cac2.70023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tao Y, Felber JG, Zou Z, et al. Chemical proteomic discovery of isotype-selective covalent inhibitors of the RNA methyltransferase NSUN2. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2023;62(51): e202311924. 10.1002/anie.202311924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Zhu D, Yang Y, et al. Restricted tRNA methylation by intermolecular disulfide bonds in DNMT2/TRDMT1. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;251: 126310. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue S, Xu H, Sun Z, et al. Depletion of TRDMT1 affects 5-methylcytosine modification of mRNA and inhibits HEK293 cell proliferation and migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;520(1):60–6. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.09.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goll MG, Kirpekar F, Maggert KA, et al. Methylation of tRNAAsp by the DNA methyltransferase homolog Dnmt2. Science. 2006;311(5759):395–8. 10.1126/science.1120976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yagi M, Kabata M, Tanaka A, et al. Identification of distinct loci for de novo DNA methylation by DNMT3A and DNMT3B during mammalian development. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3199. 10.1038/s41467-020-16989-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang ZX, Li J, Xiong QP, Li H, Wang ED, Liu RJ. Position 34 of tRNA is a discriminative element for m5C38 modification by human DNMT2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(22):13045–61. 10.1093/nar/gkab1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Liu H, Zhu D, et al. Biological function molecular pathways and druggability of DNMT2/TRDMT1. Pharmacol Res. 2024;205: 107222. 10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Yu K, Hu H, et al. METTL17 coordinates ferroptosis and tumorigenesis by regulating mitochondrial translation in colorectal cancer. Redox Biol. 2024;71: 103087. 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Li X, Tang H, et al. NSUN2-mediated m5C methylation and METTL3/METTL14-mediated m6A methylation cooperatively enhance p21 translation: NSUN2 and METTL3/METTL14 regulate p21 translation. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(9):2587–98. 10.1002/jcb.25957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu L, Xu H, Xiong H, Yang C, Wu Y, Zhang Q. The role of m5C RNA modification in cancer development and therapy. Heliyon. 2024;10(19): e38660. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alagia A, Gullerova M. The methylation game: epigenetic and epitranscriptomic dynamics of 5-methylcytosine. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10: 915685. 10.3389/fcell.2022.915685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu Y, Yang L, Feng Q, et al. RNA 5-methylcytosine modification: regulatory molecules, biological functions, and human diseases. Genomics Proteomics Bioinform. 2024;22(5): qzae063. 10.1093/gpbjnl/qzae063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou Z, Dou X, Li Y, et al. RNA m5C oxidation by TET2 regulates chromatin state and leukaemogenesis. Nature. 2024;634(8035):986–94. 10.1038/s41586-024-07969-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lio CWJ, Yuita H, Rao A. Dysregulation of the TET family of epigenetic regulators in lymphoid and myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2019;134(18):1487–97. 10.1182/blood.2019791475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arguello AE, Li A, Sun X, Eggert TW, Mairhofer E, Kleiner RE. Reactivity-dependent profiling of RNA 5-methylcytidine dioxygenases. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4176. 10.1038/s41467-022-31876-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong J, Xu Z, Ding N, Wang Y, Chen W. The biological function of demethylase ALKBH1 and its role in human diseases. Heliyon. 2024;10(13): e33489. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bian K, Lenz SAP, Tang Q, et al. DNA repair enzymes ALKBH2, ALKBH3, and AlkB oxidize 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(11):5522–9. 10.1093/nar/gkz395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su R, Dong L, Li Y, et al. Targeting FTO suppresses cancer stem cell maintenance and immune evasion. Cancer Cell. 2020;38(1):79-96.e11. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng X, Deng S, Li Y, et al. Targeting m6A demethylase FTO to heal diabetic wounds with ROS-scavenging nanocolloidal hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2025;317: 123065. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.123065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei J, Yu X, Yang L, et al. FTO mediates LINE1 m6A demethylation and chromatin regulation in mESCs and mouse development. Science. 2022;376(6596):968–73. 10.1126/science.abe9582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu Y, Chen C, Tong X, et al. NSUN2 modified by SUMO-2/3 promotes gastric cancer progression and regulates mRNA m5C methylation. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(9):842. 10.1038/s41419-021-04127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cimmino L, Dolgalev I, Wang Y, et al. Restoration of TET2 function blocks aberrant self-renewal and leukemia progression. Cell. 2017;170(6):1079-1095.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.An J, González-Avalos E, Chawla A, et al. Acute loss of TET function results in aggressive myeloid cancer in mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10071. 10.1038/ncomms10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Traugot CM, Bubenik JL, et al. N6-methyladenosine in 7SK small nuclear RNA underlies RNA polymerase II transcription regulation. Mol Cell. 2023;83(21):3818-3834.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Z, Zeng C, Yang L, et al. YTHDF2 promotes ATP synthesis and immune evasion in B cell malignancies. Cell. 2025;188(2):331-351.e30. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang N, Chen RX, Deng MH, et al. M5C-dependent cross-regulation between nuclear reader ALYREF and writer NSUN2 promotes urothelial bladder cancer malignancy through facilitating RABL6/TK1 mrnas splicing and stabilization. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(2):139. 10.1038/s41419-023-05661-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen X, Li A, Sun BF, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(8):978–90. 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xue C, Gu X, Zheng Q, et al. Alyref mediates RNA m5C modification to promote hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:130. 10.1038/s41392-023-01395-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dai X, Gonzalez G, Li L, et al. YTHDF2 binds to 5-methylcytosine in RNA and modulates the maturation of ribosomal RNA. Anal Chem. 2020;92(1):1346–54. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu L, Chen Y, Zhang T, et al. YBX1 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via m5C-dependent SMOX mRNA stabilization. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(20):2302379. 10.1002/advs.202302379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang Y, Wang L, Han X, et al. RNA 5-methylcytosine facilitates the maternal-to-zygotic transition by preventing maternal mRNA decay. Mol Cell. 2019;75(6):1188-1202.e11. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shi M, Zhang H, Wu X, et al. ALYREF mainly binds to the 5′ and the 3′ regions of the mRNA in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(16):9640–53. 10.1093/nar/gkx597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang N, Chen R, Deng M, et al. M5C-dependent cross-regulation between nuclear reader ALYREF and writer NSUN2 promotes urothelial bladder cancer malignancy through facilitating RABL6/TK1 mrnas splicing and stabilization. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(2): 139. 10.1038/s41419-023-05661-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhong L, Wu J, Zhou B, et al. ALYREF recruits ELAVL1 to promote colorectal tumorigenesis via facilitating RNA m5C recognition and nuclear export. npj Precis Onc. 2024;8(1):243. 10.1038/s41698-024-00737-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Viphakone N, Sudbery I, Griffith L, Heath CG, Sims D, Wilson SA. Co-transcriptional loading of RNA export factors shapes the human transcriptome. Mol Cell. 2019;75(2):310-323.e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang X, Yang Y, Sun BF, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export—NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m5C reader. Cell Res. 2017;27(5):606–25. 10.1038/cr.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang ZZ, Meng T, Yang MY, et al. ALYREF associated with immune infiltration is a prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2022;21: 101441. 10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang J, Li Y, Xu B, et al. ALYREF drives cancer cell proliferation through an ALYREF-MYC positive feedback loop in glioblastoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:145–55. 10.2147/OTT.S286408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Y, Yan Y, Yin J, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of YTHDF2 promotes HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma progression in an N6-methyladenosine-dependent manner. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:63. 10.1038/s41392-023-01316-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang L, Dou X, Chen S, et al. YTHDF2 inhibition potentiates radiotherapy anti-tumor efficacy. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(7):1294-1308.e8. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang L, Ren Z, Yan S, et al. Nsun4 and Mettl3 mediated translational reprogramming of Sox9 promotes BMSC chondrogenic differentiation. Commun Biol. 2022;5:495. 10.1038/s42003-022-03420-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Z, Zeng C, Yang L, et al. YTHDF2 promotes ATP synthesis and immune evasion in B cell malignancies. Cell. 2024. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Hou X, Dong Q, Hao J, et al. NSUN2-mediated m5C modification drives alternative splicing reprogramming and promotes multidrug resistance in anaplastic thyroid cancer through the NSUN2/SRSF6/UAP1 signaling axis. Theranostics. 2025;15(7):2757–77. 10.7150/thno.104713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma HL, Bizet M, Da Costa CS, et al. SRSF2 plays an unexpected role as reader of m5C on mRNA, linking epitranscriptomics to cancer. Mol Cell. 2023;83(23):4239-4254.e10. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu M, Ni M, Xu F, et al. NSUN6-mediated 5-methylcytosine modification of NDRG1 mRNA promotes radioresistance in cervical cancer. Mol Cancer. 2024;23:139. 10.1186/s12943-024-02055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen T, Xu ZG, Luo J, et al. NSUN2 is a glucose sensor suppressing cGAS/STING to maintain tumorigenesis and immunotherapy resistance. Cell Metab. 2023;35(10):1782-1798.e8. 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tong R, Li Y, Wang J, et al. NSUN2 Knockdown Promotes the Ferroptosis of Colorectal Cancer Cells Via m5C Modification of SLC7A11 mRNA. Biochem Genet. 2025. 10.1007/s10528-025-11035-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Lin Y, Zhao Z, Nie W, et al. Overview of distinct 5-methylcytosine profiles of messenger RNA in normal and knock-down NSUN2 colorectal cancer cells. Front Genet. 2023;14:1121063. 10.3389/fgene.2023.1121063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang L, Shi J, Zhong M, et al. NXPH4 mediated by m5C contributes to the malignant characteristics of colorectal cancer via inhibiting HIF1A degradation. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29(1):111. 10.1186/s11658-024-00630-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yin H, Huang Z, Niu S, et al. 5-methylcytosine (m5C) modification in peripheral blood immune cells is a novel non-invasive biomarker for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 967921. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.967921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiang Z, Li S, Han MJ, Hu GM, Cheng P. High expression of NSUN5 promotes cell proliferation via cell cycle regulation in colorectal cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(7):3858–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hou C, Liu J, Liu J, et al. 5-methylcytosine-mediated upregulation of circular RNA 0102913 augments malignant properties of colorectal cancer cells through a microRNA-571/Rac family small GTPase 2 axis. Gene. 2024;901: 148162. 10.1016/j.gene.2024.148162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cui Y, Lv P, Zhang C. NSUN6 mediates 5-methylcytosine modification of METTL3 and promotes colon adenocarcinoma progression. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2024;38(6): e23749. 10.1002/jbt.23749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chellamuthu A, Gray SG. The RNA methyltransferase NSUN2 and its potential roles in cancer. Cells. 2020;9(8):1758. 10.3390/cells9081758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang R, Gan W, Zong J, et al. Developing an m5C regulator–mediated RNA methylation modification signature to predict prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy in rectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1054700. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1054700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu Q, Le Scolan E, Jahchan N, Ji X, Xu A, Luo K. Snon antagonizes the hippo kinase complex to promote TAZ signaling during breast carcinogenesis. Dev Cell. 2016;37(5):399–412. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J, Zhu W, Han J, et al. The role of the HIF-1α/ALYREF/PKM2 axis in glycolysis and tumorigenesis of bladder cancer. Cancer Commun. 2021;41(7):560–75. 10.1002/cac2.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang Y, Fan H, Liu H, et al. NOP2 facilitates EZH2-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition by enhancing EZH2 mRNA stability via m5C methylation in lung cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(7):506. 10.1038/s41419-024-06899-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]