Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to compare the ganglion cell layer changes following temporal inverted internal limiting membrane flap (i-ILMF) surgery for idiopathic macular hole (IMH).

Methods

This retrospective study included 50 eyes that underwent vitrectomy with a 2.5-disc-diameter temporal inverted internal limiting membrane flap (i-ILMF) technique. Demographic, functional, and anatomical data were collected before and after the surgery. The best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings such as ganglion cell layer -inner plexiform layer (GCL-IPL) thickness and hole related parameters/indexes were compared in the preoperative period and 6th month after surgery.

Results

The average age of the patients was 68.8 ± 10.31 years, and the average duration of visual loss was 10.95 ± 6.54 months. The average GCL-IPL thickness increased significantly from 57.98 ± 21.43 μm to 68.74 ± 13.62 μm at 6 months after surgery (p < 0.001). The nasal GCL-IPL thickness was significantly increased from 56.94 ± 24.18 μm to 73.10 ± 15.39 μm after 6 months after surgery (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The temporal i-ILMF technique not only leads to high anatomical success and visual improvement but also results in a significant increase in GCL-IPL thickness postoperatively, suggesting a unique structural response to this method.

Keywords: Ganglion cell layer, Idiopathic macular hole, Temporal inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique

Introduction

An idiopathic macular hole (IMH) is a full-thickness defect in the neurosensory retina at the central fovea, leading to significant visual impairment. IMH predominantly affects women (67–91%) between the ages of 50 and 70 years, with bilateral involvement in 3–27% of cases [1]. The condition arises from vitreomacular traction and other pathophysiological mechanisms, resulting in central vision loss, which can profoundly impact the quality of life. The standard surgical treatment for IMHs involves pars plana vitrectomy combined with internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling, which is often assisted by staining dyes, such as triamcinolone acetonide (TA), indocyanine green (ICG), or Brilliant Blue G (BBG), to increase visibility [2].

Moderate to large macular holes often fail to close with standard ILM peeling surgery and can lead to damage to the ganglion cell layer–inner plexiform layer (GCL–IPL). For holes exceeding 500 μm, standard vitrectomy with ILM peeling has limited efficacy, with up to 44% of holes remaining unclosed and the need for reoperation frequently occurring. Even when closure is achieved, visual acuity often remains below 0.2 logMAR. Moreover, losses of nerve fibres and ganglion cells due to toxicity associated with the staining material or direct mechanical trauma during vitrectomy have been documented following standard ILM peeling [3–5]. To improve both the anatomical success and preservation of inner retinal structures, alternative techniques have been developed. To address these limitations, Michalewska et al. [6] introduced the inverted internal limiting membrane flap (i-ILMF) technique. In this approach, a remnant ILM flap is left attached and inverted over the hole to act as a scaffold for retinal tissue proliferation and to potentially protect or support inner retinal layers. For idiopathic holes larger than 400 μm, this method has been reported to increase closure rates to approximately 98%, compared with 88% with conventional ILM peeling. Similar outcomes have been reported for myopic macular holes, including those associated with retinal detachment or macular schisis [7, 8]. Recent studies further confirmed that i-ILMFs promote higher rates of type 1 closure and improve anatomical success [9, 10]. Following MH surgery, a decrease in the GCL‒IPL thickness was observed in investigations involving either conventional ILM peeling or i-ILMF techniques [3, 11, 12]. Therefore, this study was designed to address a central question: can a modified technique involving a larger (2.5 DD) inverted ILM flap prevent or even reverse the postoperative thinning of the GCL‒IPL that is observed with conventional approaches? While most studies report GCL thinning after ILM peeling, we hypothesized that using a larger flap (2.5 DD) with the temporal i-ILMF technique might provide a scaffold that supports or stimulates the GCL, leading to its increased thickness.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective study of 50 patients with MHs who underwent pars plana vitrectomy with the temporal i-ILMF technique between January 2022 and January 2024 at the Department of Ophthalmology – Retina Unit, Ankara Bilkent City Hospital (Ankara, Turkey).

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee (E1/1750/2021). All patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Preoperative patient selection

We included individuals aged 18 years and older who had an idiopathic full-thickness macular hole (FTMH). This was defined as a complete defect in the neurosensory retina at the centre of the fovea, which was diagnosed by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. The exclusion criteria included those who had other systemic disorders or ophthalmic pathologies, such as corneal conditions (e.g., keratoconus), ocular trauma, uveitis, or amblyopia, an axial length > 26 mm or a history of prior surgeries.

Examination and follow-up

The baseline examination included an assessment of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) using a Snellen chart (converted to the logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution [logMAR] for analysis), biomicroscopic slit-lamp evaluation, and intraocular pressure measurement using Goldmann applanation tonometry. After pupil dilatation with 0.5% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine, posterior segment examination and optical coherence tomography (OCT) analysis were performed. Assessments were performed at baseline and 6 months after the surgery. The reason for specifically performing ganglion cell analysis at 6 months postsurgery was that the administered C3F8 gas could remain in the eye for 6–8 weeks. By evaluating the OCT scans at 6 months, we ensured that the gas had been completely absorbed and would not interfere with the measurements.

Optical coherence tomography imaging

Macular cube analysis (512 × 128 scans) using Cirrus HD-OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) was performed following pupil dilatation before surgery and at the 6-month postoperative visit. Subsequently, an investigator thoroughly examined all the photographs and rejected those that had a signal strength lower than 7, missing data on the peripapillary ring, apparent motion artefacts, or inappropriate segmentation. Automated segmentation was performed for GCL–IPL thickness. OCT scans that did not provide complete correct segmentation in automatic mode were excluded. With respect to the OCT results, manual measurements were carried out on the MH minimum diameter (the smallest width of the hole), base diameter (measured at the level of the RPE), height, hole form factor (HFF) [13, 14], MH index (MHI) [15], and tractional hole index (THI) [16]. On the basis of the minimum diameter, the MHs were categorized as suggested by the International Vitreomacular Traction Study into large (> 400 μm), intermediate (250–400 μm), or small (< 250 μm) MHs. The ratio of the hole height to the base diameter was defined as the MHI. The HFF was calculated as the ratio of the sum of the right and left arm lengths divided by the basal diameter of the hole, and the THI was defined as the ratio of the maximal height to the minimum diameter. In addition, we measured the mean thickness of the GCL–IPL in the following six sectors: the superonasal, inferonasal, superotemporal, inferotemporal, superior and inferior sectors. Furthermore, the average of the superotemporal and inferotemporal regions was used to identify the temporal quadrant, and the average of the superonasal and inferonasal regions was used to identify the nasal quadrant.

Intraoperative surgical procedure

The surgeon used only the temporal i-ILMF technique for all MHs between 2021 and 2024. A standard 3-port 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy was performed by using the Constellation vision system (Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas, USA). Surgeries were performed by just one vitreoretinal surgeon (MO). In all the patients, phacoemulsification was performed simultaneously with intraocular lens implantation prior to vitreoretinal surgery. Core vitrectomy was carried out, posterior hyaloid separation was induced, and the posterior hyaloid was completely removed by active suction with 0.2 mL of triamcinolone acetonide. MembraneBlue Dual (DORC, Zuidland, the Netherlands) was injected into the macular region to stain the ILM. To minimize dye toxicity, the incubation time with the MembraneBlue Dual dye was quite short (approximately 10 s). All the epiretinal membranes were peeled away. ILM peeling was conducted by covering an area of 2.5 DD around the MH with ILM forceps (Alcon Grieshaber-Switzerland/Alcon Labs, Inc., Fort Worth, TX). By using ILM forceps, the ILM was peeled off in a circular motion, usually starting close to the inferior or superior vascular arcade and at least two disc diameters from the MH. The edges of the MH were peeled, the wide ILM flap that resulted from trimming with the vitreous cutter was trimmed, and the annular remnant of the ILM that was hinged to the edge of the hole was gently turned upside down facing the RPE. As a result, there were typically additional layers of an inverted ILM covering the hole. Care was taken not to stuff the ILM flap into the hole. During fluid‒air exchange, if the inverted ILM flap folded over itself and resulted in inadequate coverage of the macular hole and nasal papillomacular area, one or two drops of a balanced salt solution were gently applied under air to unfold the flap. To promote better adhesion of the ILM flap over the hole and nasal papillomacular region, active fluid aspiration was performed over the optic disc with a soft-tip cannula to dry the macula. This manoeuvre ensured that the macular hole and nasal quadrant were properly and evenly covered by the ILM flap. After the hole was covered with a flap, the liquid was removed from the disc at least twice for complete drying to ensure full adhesion of the flap. PFCL was not used for flap adhesion. The backflush needle was positioned at least one disc diameter from the hole to prevent flap eversion during the fluid‒air exchange procedure, which was carried out at very low intraocular pressure. The air was replaced with 14% perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas at the end of surgery. To ensure the postoperative face-down position, all patients were operated under local anaesthesia. The patients were maintained in the prone position for 3 days after surgery.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by using the IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 28.0.1.0 for Windows, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). To determine the distribution pattern, the Shapiro‒Wilk test was performed for each variable. Continuous variables are reported as the means ± SDs and ranges. Comparisons between continuous variables (with a normal distribution) were performed using Student’s t test. For nonparametric values, the Mann‒Whitney U test was carried out for comparison. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the preoperative and postoperative BCVA and GCL thicknesses. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

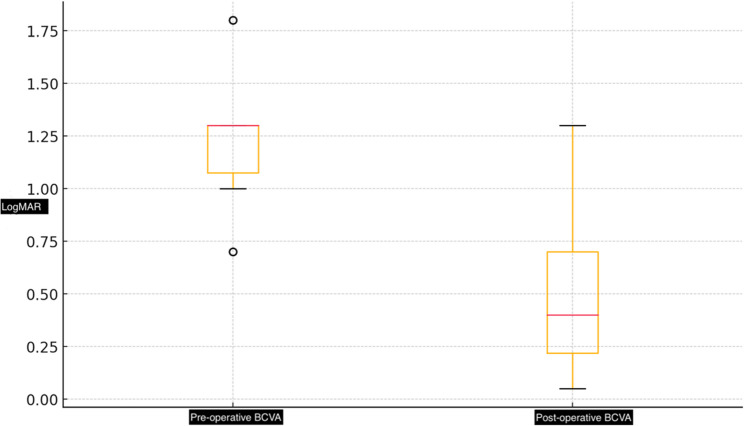

This study included fifty patients who underwent pars plana vitrectomy and the temporal i-ILMF method for idiopathic MHs at the Ankara Bilkent City Hospital retina clinic. The mean age of the patients was 68.8 ± 10.31 years, and the mean visual loss time was 10.95 ± 6.54 months. Twenty-eight patients (56%) were females. Table 1 provides a description of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. The mean BCVA significantly improved, from 1.23 ± 0.24 to 0.45 ± 0.27 logMAR at 6 months (p = 0.01) (Fig. 1). There was a statistically significant increase in BCVA (p = 0.01). The primary anatomical success rate was 98% (49/50), with just one eye requiring further surgical intervention because of the inability to close the MH. The overall anatomical success rate reached 100%.

Table 1.

This table shows statistical descriptive parameters in the study

| Descriptive Values | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 69.48 ± 8.26 | 43–86 |

| Gender (Female/Male) | 28/22 | |

| Visual Loss Time (Months) | 10.95 ± 6.54 | 1–26 |

| Base Daimeter (Μm) | 828.42 ± 329.38 | 350–1900 |

| Height Of Hole (Μm) | 372.64 ± 86.98 | 217–609 |

| Minimum Diameter (Μm) | 434.7 ± 165.19 | 165–800 |

| Hole Stage | 3.06 ± 0.89 | 2–4 |

| MHI | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.21–0.99 |

| HFF | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 0.41–1.10 |

| THI | 1.130.23 | 0.71–1.91 |

| Baseline BCVA, Logmar | 1.23 ± 0.24 | 0.70–1.80 |

| 6th Month BCVA, Logmar | 0.45 ± 0.28 | 0.05–1.3 |

| Baseline Average GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 57.98 ± 21.43 | 6-103 |

| Baseline Nasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 56.94 ± 24.18 | 10–110 |

| Baseline Temporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 90.16 ± 32.033 | 15–133 |

| Baseline Superior GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 59.76 ± 27.04 | 5-130 |

| Baseline Superotemporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 60.02 ± 22.33 | 10–93 |

| Baseline Superonasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 60.64 ± 23.96 | 16–114 |

| Baseline Inferotemporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 60.28 ± 21.77 | 10–89 |

| Baseline Inferonasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 56.64 ± 23.7 | 21–109 |

| Baseline Inferior GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 56.28 ± 25.51 | 16–124 |

| 6th Month Average GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 68.7 ± 13.62 | 28–87 |

| 6th Month Nasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 73.1 ± 15.39 | 22–96 |

| 6th Month Temporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 93.64 ± 23.38 | 25–98 |

| 6th Month Superior GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 69.7 ± 15.92 | 22–96 |

| 6th Month Superotemporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 61.02 ± 16.01 | 21–82 |

| 6th Month Superonasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 73.16 ± 17.66 | 21–108 |

| 6th Month Inferotemporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 65.24 ± 15.88 | 18–91 |

| 6th Month Inferonasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 71.64 ± 17.09 | 19–108 |

| 6th Month Inferior GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 72.76 ± 14.15 | 25–98 |

Fig. 1.

These boxplots demonstrate pre-operative and post-operative BCVA in LogMAR

The average GCL‒IPL thickness significantly increased, from 57.98 ± 21.43 μm to 68.74 ± 13.62 μm at 6 months after surgery (p < 0.001). The nasal GCL‒IPL thickness significantly increased, from 56.94 ± 24.18 μm to 73.10 ± 15.39 μm at 6 months after surgery (p < 0.001). The temporal GCL‒IPL thickness increased from 90.16 ± 32.03 μm to 93.64 ± 23.38 μm at 6 months after surgery (p = 0.619). The nonsignificant change in the temporal quadrant, in contrast to the significant change observed in the nasal quadrant, was notable. Preoperative and postoperative macular changes (Fig. 2) and GCL + IPL changes (Fig. 3) are illustrated in a sample patient. The average temporal, nasal and other segment GCL‒IPL changes are shown in Fig. 4. Preoperative and postoperative BCVA and GCL thickness changes for all segments were compared and are presented in Table 2. The patients were divided into two types, type 1 and type 2, according to the degree of MH closure. Macular hole closure is classified into Type 1 and Type 2 patterns. Type 1 closure is characterized by complete restoration of the foveal contour with continuity of the neural retina over the fovea, resulting in a closed defect and typically better visual outcomes. In contrast, Type 2 closure involves incomplete bridging of the retinal layers, with the edges of the hole attached to the retinal pigment epithelium or glial tissue covering the defect without reestablishing the normal foveal architecture. This type is considered anatomically stable but is usually associated with limited visual improvement. While 31 patients (62%) had type 1 closure, 19 patients (38%) had type 2 closure at the 6th month after surgery. In terms of the hole indices, there were no statistically significant differences between the closure patterns. There was no significant difference in the base diameter or minimum diameter of the hole between type 1 and type 2 closures. Data regarding type 1 and type 2 closures, hole indices and average GCL‒IPL levels are compared statistically in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative and post-operative changes are demonstrated in Macular Cube OCT images

Fig. 3.

Pre-operative and post-operative changes are demonstrated in ganglion cell analysis. After temporal i-ILMF technique, particularly average and nasal quadrant GCL+IPL thickness increased

Fig. 4.

This boxplots demonstrate pre-operative and post-operative GCL-IPL thickness in temporal, nasal and average

Table 2.

This table demonstrated comparison between baseline and 6th month parameters

| Parameters | Baseline | 6th Month | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCVA (LogMAR) | 1.23 ± 0.24 | 0.45 ± 0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Average GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 57.98 ± 21.43 | 68.7 ± 13.62 | 0.001 |

| Nasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 56.94 ± 24.18 | 73.1 ± 15.39 | < 0.001 |

| Temporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 90.16 ± 32.033 | 93.64 ± 23.38 | 0.619 |

| Superior GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 59.76 ± 27.04 | 69.7 ± 15.92 | 0.017 |

| Superotemporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 60.02 ± 22.33 | 61.02 ± 16.01 | 0.882 |

| Superonasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 60.64 ± 23.96 | 73.16 ± 17.66 | < 0.001 |

| Inferotemporal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 60.28 ± 21.77 | 65.24 ± 15.88 | 0.162 |

| Inferonasal GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 56.64 ± 23.7 | 71.64 ± 17.09 | < 0.001 |

| Inferior GCL-IPL Thickness (µm) | 56.28 ± 25.51 | 72.76 ± 14.15 | < 0.001 |

Table 3.

Hole related parameters and their comparison between type 1 and type 2 closure is demonstrated

| Hole Related Parameters | Type 1 Closure (n = 31) | Type 2 Closure (n = 19) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHI | 0.45 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.19 | 0.078 |

| HFF | 0.64 ± 0.13 | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 0.139 |

| THI | 1.13 ± 0.25 | 1.13 ± 0.19 | 0.913 |

| Base Diameter (mm) | 836.2 ± 274.71 | 816.75 ± 405.43 | 0.394 |

| Minimum Diameter (mm) | 424.70 ± 143.28 | 449.70 ± 196.58 | 0.937 |

Discussion

In contrast to previous studies that report ganglion cell layer thinning after macular hole surgery, our study found a significant postoperative increase in the average and nasal GCL-IPL thickness using a large temporal i-ILMF technique. The precise causes of structural and functional alterations during conventional ILM peeling for MH treatment have not yet been clearly established. The thinning reported in previous studies may be related to the surgical method itself, i.e., the use of vital dyes and perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL), and microtraumas that occur during ILM manipulation [17]. Michalwski et al. [18] sought to obtain a high closure rate for a FTMH while also lowering the surgical stress related to ILM removal. To address this issue, they created the temporal i-ILMF technique, which is a modified version of the original ILM flap approach. The temporal i-ILMF technique involves grasping and peeling the ILM from the temporal side of the fovea, extending it to the boundaries of the FTMH, and then inverting it to cover the hole in the macula. However, the nasal ILM remains unaffected. Consequently, they proposed that it decreased the probability of surgical harm to the papillomacular bundle region. In terms of surgical results, no difference was observed in visual prognosis between the techniques. A study published by Valera-Cornejo et al. [19] reported a statistically significant decrease in GCL–IPL levels at 6 months after surgery. They reported that the GCL thinned out after surgery because of direct mechanical injury to the ILM during the peeling process rather than because of the cytotoxicity of the dye. Many investigations have revealed a statistically significant decrease in the GCL‒IPL thickness at 6 months [3, 11, 20, 21].

In terms of the surgical technique used for the temporal i-ILMF, the ILM is grasped and peeled off 2.5 DD away from the macula as a standard for each patient. During circumferential peeling, the ILM is not removed completely from the retina. Instead, it is left attached to the margins of the MH. In our study, the GCL‒IPL thickness increased at the end of the sixth month. Owing to the flap being folded over the macula, the temporal i-ILMF approach was associated with increased GCL‒IPL thicknesses in both the nasal and temporal areas compared with those after conventional ILM peeling techniques. We believe that the GCL‒IPL thickness may also be influenced by the distance of the hinge created after folding over the ILM to the fovea. Nevertheless, after surgery, this hinge frequently disappears from OCT images, making it more challenging to show how it is related to it (Fig. 5). Therefore, our study demonstrated that the macula was structurally reinforced using the temporal i-ILMF procedure. Additionally, to better illustrate the surgical technique, the detailed surgical steps are provided in Fig. 6.

Fig. 5.

This figure shows inverted ILM flap technique and ILM folding at hinge region

Fig. 6.

Intraoperative screenshots demonstrating the steps of temporal inverted internal limiting membrane (ILM) flap preparation. A After ILM staining, initiation of ILM peeling from the temporal side. B, C Creation of a temporal ILM flap approximately 2.5 disc diameters in length. D The prepared flap is folded to cover the macular hole and the nasal papillomacular bundle. E,F Visualization of the non-contact ILM flap covering the macula under fluid. G, H Appearance of the ILM flap covering the macular hole under air, and drying of the macula by aspirating residual fluid with a soft-tip cannula over the optic disc

Following surgery, an increase in the thickness of the GCL‒IPL was observed in our study. This thickening can result from biological processes such as glial cell activation, cellular oedema, axonal damming or structural reorganization. Additionally, an increased thickness in the ILM region may reflect glial proliferation and tissue remodelling during the healing process. These mechanisms can lead to a significant increase in the GCL‒IPL thickness, as demonstrated via OCT.

Our study properly standardized the size of the flap by pinching at a distance of 2.5 DD from the centre of the MH in each patient. Importantly, however, this value may change for each patient. A number of studies included the construction of an ILM peel with approximately 2 DD [3, 19, 22]. Unlike other studies, our study revealed that the GCL‒IPL thickness was greater after surgery. This can be explained by the fact that a larger than 2-DD flap, such as a 2.5-DD flap, was folded onto the macula. Another explanation could be extensive peeling. Khodabande et al. [23] reported that a wider ILM peel of 4 DD appeared to provide better anatomical consequences than a more limited 2-DD peel for an idiopathic FTMH. Consequently, a larger (2.5 DD) flap acts as a better scaffold, leading to GCL thickening, promoting glial cell proliferation, or providing a matrix that reduces axonal retraction, which, in contrast to previous studies, may result in an apparent increase in the volume on OCT, as observed in this study.

While the use of a dye during surgery has been predicted to have an impact on the thickness of the GCL, there is currently a lack of conclusive evidence to support this claim. Several studies investigating the ILM peeling technique have suggested that the ILM dye may lead to a decrease in the GCL thickness [3, 11, 24].

Comparative research was performed using the i-ILMF technique to evaluate the effectiveness of the Infracyanine Green and Brilliant Blue dyes. Although the GCL thickness was greater in the Brilliant Blue group than in the Infracyanine Green group after a long-term postoperative period, the GCL thicknesses were found to be less than normal after both dyes were applied [12]. Furthermore, in many studies, vitreoretinal surgeons used PFCL to attach ILM flaps to the macular hole area [25, 26]. However, direct contact of the PFC-treated ILM with the peeled retina may cause retinal damage and lead to a decrease in the number of ganglion cells. Therefore, we did not use PFCL in our study. Notably, the choice of C3F8 gas as a tamponade may have contributed to the stabilization and adhesion of the inverted ILM flap over the macular hole during the postoperative period. Compared with SF6, C3F8 has a longer intraocular persistence time and typically remains in the vitreous cavity for approximately 6–8 weeks. This prolonged tamponade effect can help maintain the inverted flap in contact with the underlying retinal pigment epithelium and the edges of the hole, potentially facilitating glial proliferation and scaffold integration.

The main limitation of this study is the lack of a control group (e.g., with a conventional ILM peel or a smaller flap size). Future prospective studies comparing conventional ILM peeling and the temporal inverted ILM flap technique in terms of the ganglion cell analysis, as well as investigations evaluating different flap sizes, are warranted to address this limitation. The other limitation of our study is that it only analysed basic high-contrast central acuity, without assessing contrast sensitivity, retinal sensitivity, or microperimetry. Notably, in a prospective trial comparing two groups of patients who underwent typical FTMH surgery (ILM peeling), MP-1 microperimetry was unable to detect any difference over a period of 12 months [27]. Another limitation of this study is that it is not possible to make any comparisons between dyes, as the same dye was used.

In conclusion, the temporal i-ILMF procedure is a surgically effective option. During the postoperative period, it improves visual acuity while also providing structural support to the ganglion cell layer. In contrast to the findings of previous studies, the thickening of the ganglion cell layer after surgery has significant value in this study. To obtain more conclusive findings, it is necessary to conduct studies with larger sample sizes

Authors’ contributions

Performing of surgery and material gathering provided by MO, statistical analysis provided by MŞ, writing of manuscript provided by GÇ, supervision provided by MO. All author checked last revision of manuscript, and declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that there is no funding for the study.

Data availability

Performing of surgery and material gathering provided by MO, statistical analysis provided by MŞ, writing of manuscript provided by GÇ, supervision provided by MO. All author checked last revision of manuscript, and declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided informed consent in accordance with the guidelines approved by the ethics committee. The study received ethics committee approval from Ankara City Hospital (E1/1750/2021). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brooks HL. Macular hole surgery with and without internal limiting membrane peeling. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1939–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dera AU, Stoll D, Schoeneberger V, Walckling M, Brockmann C, Fuchsluger TA, et al. Anatomical and functional results after vitrectomy with conventional ILM peeling versus inverted ILM flap technique in large full-thickness macular holes. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2023;9(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba T, Hagiwara A, Sato E, Arai M, Oshitari T, Yamamoto S. Comparison of vitrectomy with brilliant blue G or indocyanine green on retinal microstructure and function of eyes with macular hole. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2609–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tosi GM, Martone G, Balestrazzi A, Malandrini A, Alegente M, Pichierri P. Visual field loss progression after macular hole surgery. J Ophthalmol. 2009;2009:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai M, Iijima H, Gotoh T, Tsukahara S. Optical coherence tomography of successfully repaired idiopathic macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:621–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Adelman RA, Nawrocki J. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for large macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2018–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuriyama S, Hayashi H, Jingami Y, Kuramoto N, Akita J, Matsumoto M. Efficacy of inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for the treatment of macular hole in high myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(1):125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SN, Yang CM. Inverted internal limiting membrane insertion for macular Hole-Associated retinal detachment in high myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;162:99–e1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghoraba H, Rittiphairoj T, Akhavanrezayat A, Karaca I, Matsumiya W, Pham B, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane flap versus Pars plana vitrectomy with conventional internal limiting membrane peeling for large macular hole. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;8(8):CD015031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramtohul P, Parrat E, Denis D, Lorenzi U. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique versus complete internal limiting membrane peeling in large macular hole surgery: a comparative study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sevim MS, Sanisoglu H. Analysis of retinal ganglion cell complex thickness after brilliant blue-assisted vitrectomy for idiopathic macular holes. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38:180–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cillino S, Castellucci M, Cillino G, Sunseri V, Novara C, Di Pace F, et al. Infracyanine green vs. Brilliant blue G in inverted flap surgery for large macular holes: A Long-Term Swept-Source OCT analysis. Med (Kaunas). 2020;56(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uemoto R, Yamamoto S, Aoki T, Tsukahara I, Yamamoto T, Takeuchi S. Macular configuration determined by optical coherence tomography after idiopathic macular hole surgery with or without internal limiting membrane peeling. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1240–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Hoerauf H. Predictive values in macular hole repair. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusuhara S, Teraoka Escaño MF, Fujii S, Nakanishi Y, Tamura Y, Nagai A, et al. Prediction of postoperative visual outcome based on hole configuration by optical coherence tomography in eyes with idiopathic macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:709–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ruiz-Moreno JM, Staicu C, Piñero DP, Montero J, Lugo F, Amat P. Optical coherence tomography predictive factors for macular hole surgery outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:640–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Takai Y, Tanito M, Sugihara K, Ohira A. The role of single-layered flap in temporal inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for macular holes: pros and cons. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:5737083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Dulczewska-Cichecka K, Adelman RA, Nawrocki J. Temporal inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique versus classic inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique: a comparative study. Retina. 2015;35:1844–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Valera-Cornejo D, García-Roa M, Ramírez-Neria P, Romero-Morales V, García-Franco R. Macular ganglion cell complex thickness after vitrectomy with the inverted flap technique for idiopathic macular holes. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2021;85:120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Seo KH, Yu SY, Kwak HW. Topographic changes in macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness after vitrectomy with indocyanine green-guided internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic macular hole. Retina. 2015;35:1828–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hashimoto Y, Saito W, Fujiya A, Yoshizawa C, Hirooka K, Mori S, et al. Changes in inner and outer retinal layer thicknesses after vitrectomy for idiopathic macular hole: implications for visual prognosis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabater AL, Velázquez-Villoria Á, Zapata MA, Figueroa MS, Suárez-Leoz M, Arrevola L, et al. Evaluation of macular retinal ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness after vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic macular holes. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:458631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodabande A, Mahmoudi A, Faghihi H, Bazvand F, Ebrahimi E, Riazi-Esfahani H, et al. Outcomes of idiopathic full-thickness macular hole surgery: comparing two different ILM peeling sizes. J Ophthalmol. 2020;2020:1619450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanckaert G, Vander Mijnsbrugge J, Delbecq AL, Fils JF, Jansen J, Van Calster J, et al. Efficacy and safety evaluation of monoblue dual view and monoblue ILM view vital stains during vitrectomy surgery. 2024. 10.1177/11206721241261099. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.La Mantia A, Mateo C. Modified perfluorocarbon liquid/internal limiting membrane interface staining in myopic macular hole retinal detachment. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023;33:602–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hu Z, Gu X, Qian H, Liang K, Zhang W, Ji J, et al. Perfluorocarbon liquid-assisted inverted limiting membrane flap technique combined with subretinal fluid drainage for macular hole retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes. Retina. 2022;42:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Scupola A, Mastrocola A, Sasso P, Fasciani R, Montrone L, Falsini B, et al. Assessment of retinal function before and after idiopathic macular hole surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(1):132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Performing of surgery and material gathering provided by MO, statistical analysis provided by MŞ, writing of manuscript provided by GÇ, supervision provided by MO. All author checked last revision of manuscript, and declare that there are no conflict of interest.