Abstract

The immune response is modulated by a diverse array of signals within the tissue microenvironment, encompassing biochemical factors, mechanical forces, and pressures from adjacent tissues. Furthermore, the extracellular matrix and its constituents significantly influence the function of immune cells. In the case of carcinogenesis, changes in the biophysical properties of tissues can impact the mechanical signals received by immune cells, and these signals c1an be translated into biochemical signals through mechano-transduction pathways. These mechano-transduction pathways have a profound impact on cellular functions, influencing processes such as cell activation, metabolism, proliferation, and migration, etc. Tissue mechanics may undergo temporal changes during the process of carcinogenesis, offering the potential for novel dynamic levels of immune regulation. Here, we review advances in mechanoimmunology in malignancy studies, focusing on how mechanosignals modulate the behaviors of immune cells at the tissue level, thereby triggering an immune response that ultimately influences the development and progression of malignant tumors. Additionally, we have also focused on the development of mechano-immunoengineering systems, with the help of which could help to further understand the response of tumor cells or immune cells to alterations in the microenvironment and may provide new research directions for overcoming immunotherapeutic resistance of malignant tumors.

Keywords: immunotherapeutic resistance, mechano-immunoengineering systems, mechano-immunology, mechano-transduction pathways, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Mechano-transduction is the process by which cells convert mechanical signals into biochemical cues that modulate cellular functions. In altered tissue mechanics, changes occur in mechano-transduction components like adhesion molecules, ion channels, and cytoskeletal proteins[1,2]. Diseases such as atherosclerosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and peritumoral environments show increased tissue stiffness[3,4], while others like abscesses and necrotic tumor cores exhibit softening[5]. During carcinogenesis, changes in cell stiffness, adhesion, and tension affect tumor infiltration and metastasis[2,6-10]. Understanding how these biophysical signals impact immune cell activation could offer insights for cancer treatments.

Immunotherapy, while changing the outlook of cancer treatment, still faces many difficulties in the clinic. Recent studies suggest that mechanical abnormalities may be a key factor in the efficacy of immunotherapy,[11] and therefore, they may represent a new direction for enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy. In this review, we will discuss the mechanical forces present in the tumor microenvironment and their relation to tumor immune escape. In addition, we detail how the relevant mechanical force signaling pathways regulate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment and propose the use of mechano-immunoengineering systems to regulate and explore the function of immune cells to provide new ideas for cancer immunotherapeutic approaches.

Mechanical forces in the tumor microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem comprising immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, and the extracellular matrix (ECM). These components vary by tissue type and evolve alongside tumor development[12-14]. Recent research indicates that, in addition to biochemical cues, physical signals significantly affect cellular behavior, including proliferation and metastasis[15]. Key physical signals in tumors include increased stromal stiffness, solid stress, and interstitial fluid pressure. These forces interact synergistically during cancer initiation and progression, collectively influencing tumor development rather than acting in isolation[16,17].

ECM remodeling and stiffening are hallmarks of solid tumors and have been used to detect various cancer types[18]. Tumor ECM stiffening results from excessive ECM protein and enzyme activity, leading to collagen cross-linking and matrix reorganization[19]. During tumorigenesis, solid stresses accumulate, and tumor growth under compressive stress can impact cancer cell proliferation and compress surrounding blood and lymphatic vessels[20]. Additionally, fluid stresses, including microvascular and interstitial pressures, as well as shear forces from blood, lymph, and interstitial flow, affect the ECM and cancer cells. Even low levels of sustained fluid shear stress can influence epithelial cell adhesion in ovarian cancer progression[21]. Overall, solid and fluid stresses in the TME can drive cell motility and promote tumorigenesis.

Solid tumor microenvironments are typically stiffer than healthy tissues due to abnormal ECM characteristics, with tumor progression often correlating with increased mechanical rigidity[22]. ECM stiffness can impede cell movement and suppress immune responses[23]. The collagen-rich, fibrous ECM surrounding tumors also hinder T-cell migration and limit their dispersal from the tumor mass[24], with studies showing that high-collagen-density breast cancer tissues have fewer infiltrating T cells[25]. Despite the rigid ECM, tumor cells within solid tumors are usually softer and more mechanically heterogeneous than healthy cells[5]. As tumors are mechanically constrained by surrounding tissues, they shift from a proliferative to a metastatic phenotype, with metastatic cells displaying distinct mechanical traits – some become stiffer to cross the basement membrane, while others soften to move through gaps in the ECM[26,27].

Few studies have investigated the response of tumor-infiltrating immune cells to the heterogeneous mechanical environment present within the tumor. However, evidence suggests that cytotoxic T cells are more effective at killing tumors when the tumor cells become mechanically stiff. This is because mechanically stiff tumor cell membranes are more prone to stretching and are more vulnerable to perforation by T cells[28]. This difference in the ability to kill tumor cells may promote surviving cells capable of repopulating the tumor[29]. Further research is needed to examine whether therapeutic modifications of the ECM impact tumor stiffness and related immune responses, with the potential to enhance clinical outcomes. Furthermore, mechanical stress has different effects on monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells themselves[30-34]. Monocytes subjected to fluid forces during their migration to tissues exhibit enhanced adhesion, activation of CD11b integrins, enhanced phagocytosis, and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. After entering tissues and differentiating into macrophages, macrophages are sensitive to the hardness of their phagocytic targets, which is triggered through Fcγ receptors, which in turn triggers integrin localization to the phagocytic cup, prompting the completion of the phagocytic process. Dendritic cells (DCs) are stimulated by shear stress to increase the expression of MHC I and CD86 and to enhance the functions of adherence and migration, and the high-hardness environment after entering tissues promotes the maturation of DCs and reduces the concentration threshold of antigen required for their activation of T cells. A harder matrix environment induces aggregation of DNAX-associated protein 10, which forms a complex with NKG2D and activates NK cell signaling. The hard matrix environment induces BCR aggregation, which elevates the affinity of B cells for antigen, resulting in the formation of more receptor microclusters and enhanced B cell activation. In conclusion, tumor development and therapeutic efficacy are closely related to the mechanical properties of ECM. Taking advantage of the mechanical properties of tumor cells and immune cells may be beneficial in the development of oncology therapeutic strategies; e.g. “softening” tumor cells and “stiffening” immune cells may improve therapeutic efficacy.

Tumor mechanical stress and tumor biology

Studies have made significant strides in reducing cancer cell metastasis and growth through various therapies[35-39]. Immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and adoptive cell transfer (ACT) have also greatly impacted cancer treatment[40-49]. In addition, vaccines have not only shown remarkable results in the prevention and control of infectious diseases[50,51] but also play a pivotal role in the immunotherapy of tumors[52]. However, resistance to immunotherapy remains a major challenge, largely due to cancer cells’ ability to evade immune responses. Understanding and targeting these immune evasion mechanisms could improve treatment outcomes. Notably, processes like autophagy and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are key to immune evasion[53], and both are induced by mechanical stresses, including fluid shear and solid stress (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanical forces drive tumor progression by inducing EMT and autophagy, leading to immune escape. Solid stress in tumors (compression and stretching) collapses vessels, causing hypoxia and triggering EMT and autophagy via stromal and invasive pathways. Additionally, stress-induced pathways (e.g. VEGF) promote immune suppression by upregulating PD-1 and recruiting Tregs and MDSCs. In circulation, fluid shear stress enhances immune evasion by recruiting MISCs, upregulating PD-L1, and inducing EMT and autophagy through cytoskeletal changes. EMT and autophagy both contribute to immune escape by inhibiting CTL-mediated killing, degrading MHC-I, and upregulating pSTAT3.

Fluid shear stress and solid stress induce autophagy

Shear stress is the tangential force exerted on the walls of blood vessels or cell surfaces during blood or fluid flow. It can be categorized into different types based on magnitude, direction, and temporal changes, such as laminar shear stress, oscillatory shear stress, and low shear stress. Solid stresses in organisms are mechanical stresses caused by physical contact, compression, or deformation between solid tissues or cells.

Fluid shear stress and solid stress are closely associated with tumorigenesis, invasion, and autophagy induction. In certain cancer cells, mechanical stress triggers autophagy as a survival mechanism. For example, lipid rafts act as mechanosensors[54], facilitating protective autophagy in HeLa cells under physiological shear stress (20 dyn/cm2)[55]. Even low shear stress (~1-2 dyn/cm2) enhances autophagic flux; specifically, shear stress of 1-1.4 dyn/cm2 activates the integrin/cytoskeleton pathway in HCC cells, leading to cytoskeletal reorganization and autophagosome formation[56,57]. While shear stress-induced autophagy is known to promote cell migration and invasion, its effects on immune response are less understood. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the relationship between shear stress and autophagy-mediated immune evasion.

Similar to shear stress, solid stress also stimulates autophagy. As tumors progress, mechanical pressure builds within the tumor and surrounding tissues due to increased cellular and ECM density, such as collagen. Studies show that solid stress in human tumors can range from 0.21 kPa to 19.0 kPa, with higher levels in cancers like pancreatic cancer characterized by dense connective tissue[58]. This solid stress compresses blood and lymphatic vessels, restricting oxygen and nutrient transport while raising interstitial fluid pressure[59]. Importantly, reduced oxygen delivery leads to hypoxia, which activates intracellular autophagy and aids in cancer cell survival[60,61]. Additionally, solid stress may directly induce autophagy.

Overall, shear stress and solid stress play key roles in regulating cellular autophagy, and different levels of shear stress and solid stress have different effects on autophagy through various types of mechanical force sensing pathways[62,63]. Laminar shear stress usually promotes cellular autophagy and the maintenance of cellular homeostasis[64], whereas oscillatory shear stress and low shear stress may inhibit cellular autophagy, leading to cellular dysfunction and disease development[65]. In addition, solid stress has a dual effect on autophagy[66]. Moderate solid stress promotes the autophagic response and contributes to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and enhancement of adaptation, whereas excessive solid stress may inhibit or aberrantize the autophagic process and cause damage to cells. However, the specific details of these influencing mechanisms still need further in-depth studies. Future studies should focus on the response mechanisms of different cell types to shear stress and solid stress under specific physiopathological conditions and how to intervene in the occurrence and development of related diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases, by regulating shear stress and solid stress.

Fluid shear stress and solid stress facilitate the activation of EMT

Mechanical stress on tumors can also increase the invasiveness and metastatic potential of cancer cells by inducing EMT. Studies have shown that when Hep-2 cells are exposed to a shear stress of 1.4 dyn/cm2, they adopt a mesenchymal-like phenotype, which reverts upon the removal of stress[67]. Shear stress has been demonstrated to activate EMT, enhancing metastasis by triggering the YAP pathway. Furthermore, shear stress can induce EMT in circulating tumor cells (CTCs), thereby promoting their survival in the bloodstream[68].

Solid stress can directly or indirectly induce EMT in cancer cells. Like autophagy, solid stress-induced hypoxia can activate key transcriptional regulators of EMT. Under hypoxic conditions, the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) promotes EMT by regulating TWIST, a crucial transcriptional regulator of EMT[69]. Solid stress, combined with IL-6 secreted by CD4 + T cells, mediates EMT activation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) cells via the Akt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway[70]. Moreover, the responses of different cell types to solid stress are associated with their specific signaling pathways. For example, signaling molecules such as E-cadherin, β-catenin, etc., may exhibit different expressions or activity when regulated by solid stress in epithelial cells, thus affecting the EMT process[71]. And in fibroblasts or tumor cells, activation of pathways such as YAP/TAZ, FAK[72,73], etc., may exhibit different sensitivities in response to mechanical stress, leading to different degrees of EMT activation. In summary, while shear stress and solid stress are significant mediators of EMT, the precise mechanisms by which the immune response promotes cancer cell survival remain unclear due to the lack of direct mechanistic studies.

Tumor mechanical stress induces immune escape

Mechanical abnormalities may contribute to poor immunotherapy responses, making them potential therapeutic targets. Malignant cells are often weaker than non-malignant cells due to higher cholesterol levels in their membranes[74]. Reducing cholesterol stiffens the ECM, enhancing cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) efficacy and improving adoptive cell transfer (ACT) outcomes in mice. This soft ECM acts as a “mechanical immune checkpoint,” enabling cancer cells to evade immune surveillance. Similarly, reducing solid stress has improved immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy in ICB-resistant metastatic breast cancer models[75]. Angiotensin receptor blockers reduce solid stress by inhibiting fibroblast activation, promoting T-cell function, and reducing immunosuppression, thus overcoming immunotherapy resistance[75]. FAK inhibitors also reduce solid stress by depleting the stroma, enhancing PD-1 immunotherapy responses in mouse models[76]. Since cancer cells exhibit strong contraction on the ECM, macrophages can effectively target CRC cells with low metastatic potential, whereas cancer cells with high metastatic potential exhibit weak contraction on the ECM, thus evading macrophage attack and achieving immune escape[77]. Mechanical properties like stiffness and viscoelasticity may further promote tumor immune escape[78], but direct evidence linking mechanical stress[79] to immune escape and its effect on immunotherapy remains limited.

The response of cancer cells to these stresses can aid in evading other immune detection mechanisms (Fig. 1). For instance, it has been demonstrated that MDA-MB-231 and BT-474 breast cancer cells, but not MCF-7 and SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells, overexpress VEGF-A due to compression force-induced downregulation of microRNA-9 (miR-9)[80]. VEGF-A increased the expression of PD-1 in VEGFR + and CD8 + T cells, thereby demonstrating its capability to suppress anti-tumor immune responses[81,82]. Furthermore, the application of shear stress has been shown to upregulate PLAU in breast cancer cells and activate YAP in breast and prostate cancer cells[83,84]. Both PLAU and YAP activation have been linked to the promotion of an immunosuppressive environment. Additionally, YAP plays a role in promoting the recruitment of immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs)[85-87]. Overall, the findings from these studies suggest a connection between tumor mechanical stress and immune escape.

Mechanosensing pathways in cells

To explore the link between tumor mechanical stress and immune escape, it is essential to understand how immune cells sense external forces. Cells within tissues are subjected to various mechanical forces such as tension, compression, shear, and interstitial flow[6,88,89]. The physical properties of the surrounding tissue, including matrix stiffness and structure, generate mechanical signals that influence cell behavior[90,91]. Evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways allow immune cells to detect these matrix changes through mechanosensors. Immune cells not only experience these external forces but also actively respond to them, applying reciprocal or superimposed forces on the stroma and nearby cells.

Mechanical signals sensed by immune cells

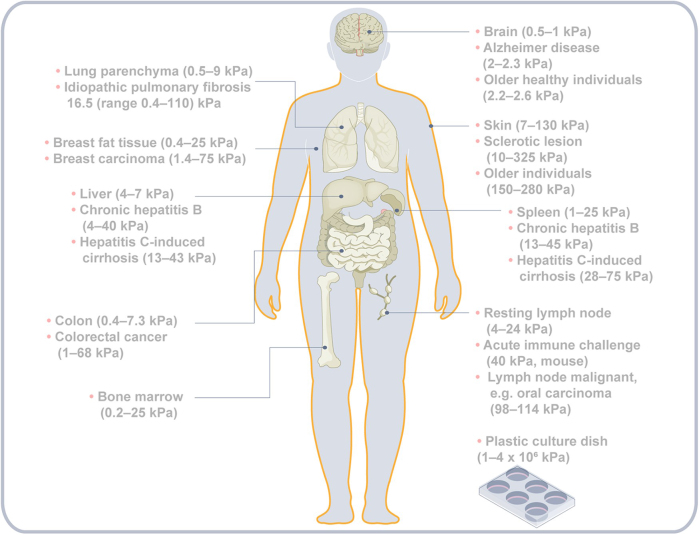

Immune cells are exposed to various mechanical signals. Tensile and compressive forces stretch or compress cells, triggering cytoskeletal rearrangements and interactions between extracellular components[90,92]. Shear forces act tangentially on cells at fluid interfaces[93], while interstitial fluid flow refers to plasma moving through the extracellular matrix into lymphatics[94]. Tissue biophysical properties (Fig. 2), primarily shaped by the ECM, determine how these forces affect immune cells[95]. Tissue stiffness, measured by the modulus of elasticity, reflects resistance to deformation. While soft tissues typically have stiffness below 10 kPa, conditions like fibrosis can raise it above 20 kPa[96-98].

Figure 2.

Stiffness in different parts of the human body under normal or pathological conditions. In certain tissues, stiffness increases under pathological conditions or during carcinogenesis, while in others, it decreases.

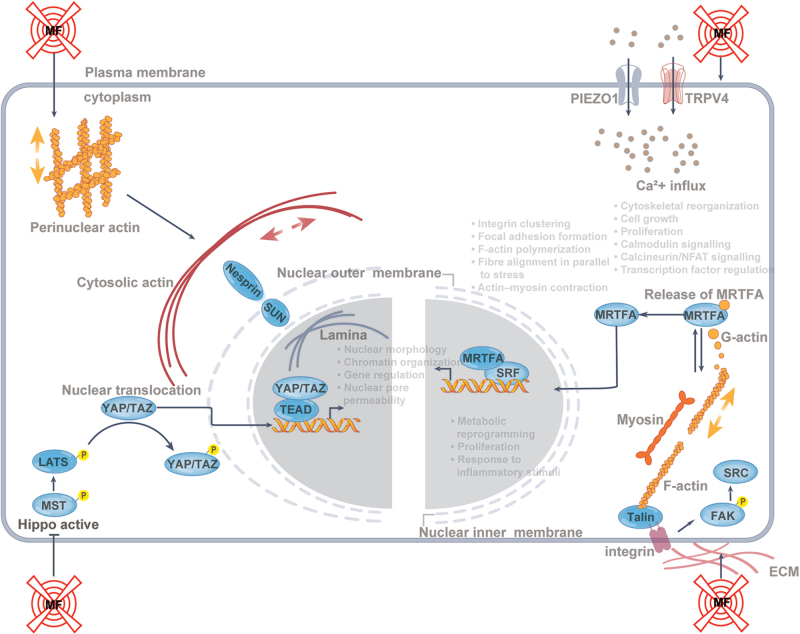

Immune cells sense and respond to mechanical signals through pathways involving mechanosensors such as integrins, TRPV4, PIEZO channels, and cytoskeletal components[99-101] (Fig. 3). These pathways regulate Ca2+ flow, cytoskeletal reorganization, and transcription. External forces are transmitted to the nucleus via the cytoskeleton and LINC complex, affecting chromatin organization and gene expression[102-106]. Actin filaments at adhesion sites drive morphological changes through polymerization and myosin contraction, regulated by Rho GTPases[107-112]. Key transcriptional regulators include SRF, MRTFA, YAP, and TAZ.

Figure 3.

Overview of mechanotransduction pathways. Bottom left: The Hippo pathway activation phosphorylates MST1/2 and LATS1/2, leading to YAP and TAZ phosphorylation and sequestration in the cytoplasm. Mechanical force (MF) inhibition of Hippo allows YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation, activating TEAD transcription factors to regulate immune genes, metabolism, proliferation, and inflammation. Bottom right: Integrins anchor cells to the ECM, forming focal adhesions that signal through FAK and SRC, influencing immune cell function, cell shape, and cytoskeletal dynamics. F-actin polymerization reduces G-actin, freeing MRTFA to enter the nucleus, where it partners with SRF to drive gene expression. Top left: The LINC complex links the nuclear scaffold to the cytoskeleton, regulating nuclear morphology, gene expression, and YAP, TAZ, and MRTFA translocation. Top right: Mechanical activation of TRPV4 and Piezo1 channels increases Ca2 + influx, affecting transcription factors, inflammation, and cytoskeleton remodeling.

Mechanotransduction in immune cells

The biophysical signals can affect immune cell function and responses. Immune cells, being adhesive and contact-dependent, are sensitive to mechanical stimuli, such as changes in extracellular matrix stiffness. Macrophages, for example, respond to substrate stiffness, which influences functions like phagocytosis[113,114], migration[113], ROS production[115], healing[116], morphology[117], and cytokine secretion[114,116,118,119]. Macrophages on rigid substrates show stronger effector functions and produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IL-6, compared to those on softer substrates, which produce less IL-10 in response to LPS[114,116,118]. Similarly, dendritic cells on stiff substrates release more pro-inflammatory cytokines and promote greater cell activation following LPS exposure[120]. Inflammation in the tumor microenvironment promotes the differentiation of stromal cells into activated fibroblasts, which express more alpha-smooth muscle actin and collagen, contributing to tissue sclerosis. This stiffening impedes chemotherapy diffusion and immune cell infiltration, a key factor in cancer progression[30].

Mechanosensing in immune cells involves detecting various mechanical stimuli, not just changes in tissue stiffness. In the circulatory system, monocytes respond to fluid shear by enhancing adhesion, phagocytosis, and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines[121]. Neutrophils also show increased phagocytosis and activation under shear, with higher platelet-neutrophil aggregation and cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels[122]. Similarly, macrophages display pro-inflammatory effects under cyclic hydrostatic pressure[96]. These findings underscore the role of mechanical signals in modulating innate immune cell functions and influencing inflammation. Additionally, innate immune pathways can trigger broad immune responses and reprogram immunosuppressive cells to regain anti-tumor potential, offering therapeutic strategies to counteract the suppressive tumor microenvironment[123].

Adaptive immune cells also respond to mechanical signals. T cells are influenced by the stiffness of DCs, with “hard” DCs requiring lower antigen concentrations for activation than “soft” DCs[124,125]. Increased cytoskeletal stiffness in DCs enhances T cell activation[125]. Stromal stiffness affects T-cell behavior, including spreading, migration[126,127], gene expression, proliferation[128], and cytotoxicity[29]. A stiffer environment boosts T-cell proliferation and activation while lowering the antigen dose required for an effector response[97]. B cells similarly sense mechanical cues, with substrate stiffness influencing B cell receptor aggregation, antigen uptake[129], proliferation, and antibody production[130]. Stiffened B cells may lose normal functions, contributing to immune suppression, tumor immune escape, and progression through abnormal cytokine production and altered tumor microenvironment interactions.

Biophysical signals and environmental forces are key in immune regulation, particularly through mechanosignaling pathways that impact immune cell activation and function. PIEZO1 and TRPV4, two mechanically gated ion channels, respond to physical stimuli at the plasma membrane, facilitating ion translocation[131]. PIEZO1 belongs to the Piezo family of cation channels[132], while TRPV4 is part of the TRP superfamily[133]. These channels open due to mechanical membrane deformation, and TRPV4 can also respond to osmotic stress, temperature changes, or inflammatory mediators like arachidonic acid and histamine[134]. Their activation increases Ca2+ influx, triggering Ca2+-regulated signaling pathways, such as the calmodulin neurophosphatase-NFAT pathway, critical for T-cell activation[135]. Elevated intracellular Ca2+ activates calmodulin neurophosphatase, which dephosphorylates NFAT, allowing its nuclear translocation[136]. Although PIEZO1-driven Ca2+ influx has been shown to activate NFAT in osteoblasts[137], this mechanism remains unconfirmed in immune cells.

In bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated by IFN-γ, activation of PIEZO1 channels on a hard matrix increases Ca2 + influx, enhancing NF-κB activation and F-actin formation, promoting an M1 inflammatory macrophage phenotype. While these macrophages also responded to IL-4 and IL-13 with increased arginase 1 (ARG1) expression, PIEZO1 activity on hard substrates suppressed IL-4/IL-13-induced ARG1 expression, indicating that mechanotransduction signaling may override other pathways[116]. Furthermore, a hard extracellular matrix (ECM) silenced the tumor suppressor RB1 via histone deacetylation, controlling cell expansion and cytokine release in a PIEZO1-dependent manner[138].

HIF-1α plays a key role in linking PIEZO1 activity to glycolysis-driven inflammatory responses, regulating immune cell metabolism. Activation of PIEZO1 by the agonist YODA1 in mouse dendritic cells induces glycolytic genes such as MYC, HK2, and SLC2A1, enhancing TNF production[120]. PIEZO1 also mediates shear force-induced inflammation, promoting monocyte adhesion, MAC1 activation, phagocytosis, and pro-inflammatory cytokine release[121]. Blocking PIEZO1 in T cells improves traction and cytotoxicity against tumors, positioning PIEZO1 as a target for enhancing cancer immunotherapy[139]. Additionally, PIEZO1 in dendritic cells regulates Th1 and Treg cell differentiation, contributing to tumor growth inhibition[140]. These findings highlight PIEZO1’s role in immune modulation across various tissue types and disease contexts.

The Hippo pathway, particularly YAP/TAZ, plays a critical role in mechanotransduction, linking mechanical signals like ECM stiffness, cell geometry, and fluid dynamics to cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation[141]. Dysregulation of this pathway is frequently observed in cancers, with YAP/TAZ acting as oncogenes and MST1/2 and LATS1/2 as tumor suppressors. Hippo pathway dysregulation is linked to cancers such as uveal melanoma and meningiomas, impacting tumor progression, metastasis, and drug resistance[142]. Furthermore, the pathway influences immunotherapy resistance by regulating immunosuppressive cells, like myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophages, through cytokines CXCL5 and CCL2[142]. These insights suggest the Hippo pathway’s involvement in immune tolerance and tumorigenesis, offering potential strategies for overcoming immunotherapeutic resistance.

Mechano-immunoengineering in malignant tumors

Engineered systems are widely used to study how mechanical signals and matrix properties influence cell function, including tissue-level forces on immune cells[143,144]. These biomaterials, often combined with ECM proteins like collagen or RGD peptides, provide natural adhesion sites for cells[145]. Advances in biomaterial design aim to more accurately mimic physiological conditions for better exploration of mechanical signaling in cell function. During tumor progression, increased ECM stiffness hampers T-cell infiltration and reduces their antitumor activity[30]. Softening the ECM has been investigated to improve drug diffusion and enhance therapies like CAR-T cells, though its impact on immune checkpoint blockade and cellular immunotherapy remains to be fully assessed. Combining ECM-targeting with strategies that modulate cellular mechanics may synergistically boost antitumor immune surveillance.

The Hippo signaling pathway involved in mechanotransduction and immune cell responses. Traditionally, this pathway is regulated by cell contact and density[146]. Mechanical signals activate MST1/MST2 and LATS1/LATS2 kinases, leading to phosphorylation of YAP and TAZ, which are retained in the cytoplasm and degraded via the proteasome[147,148]. When Hippo kinases are inhibited, YAP and TAZ translocate to the nucleus to drive gene expression by binding TEAD transcription factors[149]. YAP and TAZ are also translocated in response to ECM stiffness and cell architecture changes[150], influencing immune cell fate, metabolic reprogramming, and activation. For example, nuclear YAP/TAZ promotes M1-like macrophage activation and IL-6 production while inhibiting M2 polarization[151]. In melanoma, YAP activation enhances Treg immunosuppressive activity and increases PD-L1 expression[87,152], impacting T cells, tumor-associated macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment[153].

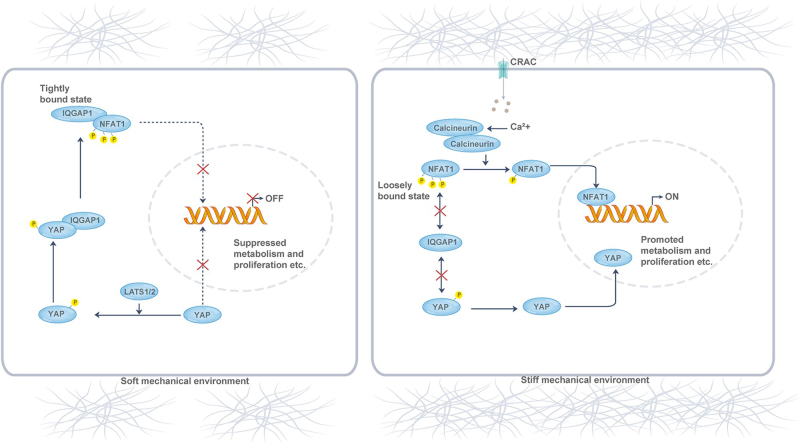

In adaptive immune cells, YAP and TAZ show similar subcellular localization influenced by matrix stiffness. In T cells, phosphorylated YAP regulates activation by modulating NFAT1’s binding affinity to its scaffolding protein, IQGAP1[97], under soft ECM conditions, thereby reducing metabolic reprogramming and activation (Fig. 4). In a stiff microenvironment, YAP moves to the nucleus, releasing NFAT1 and inducing metabolic gene expression, suppressing T-cell responses as the environment softens. YAP inhibits glycolysis, mitochondrial respiration, and amino acid uptake[154]. YAP knockdown enhances CD8 + T cell cytotoxic cytokine production and disrupts Treg cell function by reducing TGFβ-Smad signaling[87,155]. TAZ, independent of mechanistic signaling, inhibits Treg differentiation by interacting with RORγT and reducing FOXP3 acetylation[156]. YAP and TAZ remain central to coordinating mechanical signals between innate and adaptive immunity.

Figure 4.

Mechanical regulation of T-cell activity by YAP. In soft ECM environments, YAP is phosphorylated and stays in the cytoplasm, binding to IQGAP1 and sequestering NFAT1, which suppresses T-cell metabolism and proliferation. In stiff ECM environments, YAP is dephosphorylated and moves to the nucleus, releasing NFAT1 from the cytoplasm. With help from CRAC channels, calcineurin, and calmodulin, NFAT1 translocates to the nucleus, promoting T-cell activation gene expression.

Many cells form strong connections to the ECM through integrins, transmembrane receptors composed of α- and β-subunits that interact with ECM proteins[157]. Integrins cluster to create focal adhesions, which link to the cytoskeleton and activate intracellular signaling pathways through cytoskeletal rearrangements[158]. Key downstream effectors like FAK and Src regulate pathways involving RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, influencing cell motility, survival, and inflammation[159,160]. Tumor cells, such as glioma and hepatocellular carcinoma, proliferate faster and resist apoptosis on stiffer matrices, which also increases drug resistance[17].

Integrins are essential for leukocyte migration and exhibit sensitivity to mechanical stimuli, regulating immune cell functions. For example, LFA1 increases its binding affinity to ICAM1 under high matrix stiffness, aiding in dendritic cell maturation and the activation of T and NK cells[161-163]. Rigid substrates enhance macrophage phagocytosis via integrin CD11b and promote T cell actin polymerization through LFA1, leading to gene expression changes[164,165]. Additionally, matrix stiffness activates FAK, enhancing B-cell expansion and activation[166]. While some immune cells can function without integrins, they remain key for mechanosignal transduction in many contexts.

The MRTFA-SRF pathway, linked to mechanotransduction and cytoskeletal dynamics, is crucial for cellular functions. Mechanical stimulation leads to actin polymerization, releasing MRTFA from G-actin, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus and activate gene transcription with SRF[167]. In myeloid cells, this influences migration, phagocytosis, and cytoskeletal gene expression[168]. In dendritic cells, the pathway regulates cell cycle, adhesion, and lipid metabolism, with MRTFA deficiency reducing cholesterol metabolism[165], potentially impairing immune function[169]. In macrophages, MRTFA-SRF coordinates spatially constrained immunoregulatory signals[124].

The nuclear LINC complex and nuclear lamina are crucial for mechanotransduction, regulating immune functions like chemotaxis, inflammation, proliferation, and activation. A-type lamins, interacting with the LINC complex, help organize the actin cytoskeleton during T-cell activation and promote ERK1/2 phosphorylation[170,171], facilitating immune synapse formation. T cells lacking proper LINC-lamin interactions show impaired activation and proliferation. A-type lamins and the LINC complex play key roles in cytoskeletal reorganization and nuclear transcription, highlighting their importance in immune mechanotransduction. Further research is needed to explore these mechanisms in other immune cells.

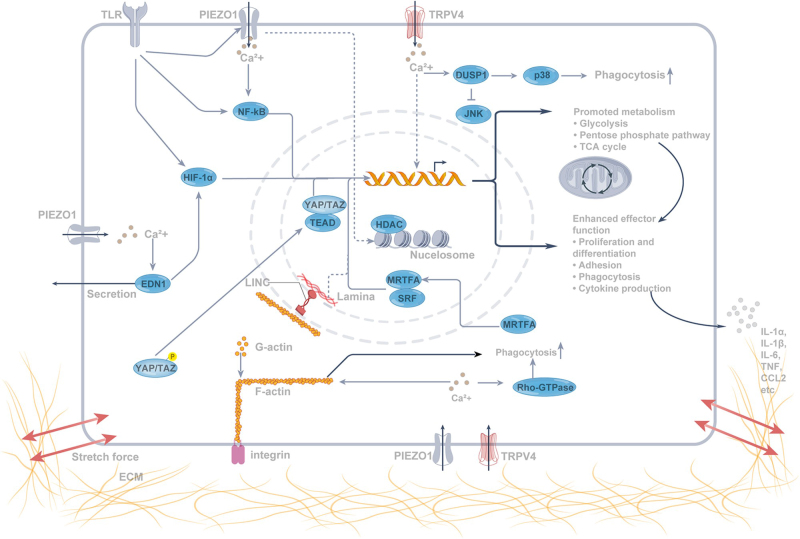

Intrinsic immune cells activate by sensing danger signals in the tissue environment, linking mechanotransduction to immune function. In disease states, mechanical stress activates mechanosensors in immune cells, allowing them to integrate signals from pattern-recognition receptors and amplify immune responses (Fig. 5). When tension decreases, a dynamic equilibrium restores, raising the threshold for danger signaling and reducing immune activation. This supports a model in which tissue-level mechanotransduction directly regulates intrinsic signaling pathways involved in danger perception.

Figure 5.

Mechanotransduction pathways and natural immune cell activation. Mechanical forces combined with pattern recognition receptor (PRR) stimulation localize Piezo1 with certain toll-like receptors (TLRs). The activation of TRPV4 and Piezo1 triggers Ca2+ influx, promoting actin polymerization, Rho GTPase activation, and enhanced phagocytosis. MRTFA enters the nucleus upon F-actin formation, driving the transcription of immune effector genes like IL-6 and CXCL9. Ca2+ also boosts TLR signaling by activating EDN1 and NF-κB, stabilizing HIF-1α, and promoting inflammatory gene expression. YAP/TAZ translocates to the nucleus, activating genes involved in glycolysis and inflammation. Piezo1 further induces histone deacetylase (HDAC) activation, contributing to inflammatory cytokine production and tumor progression.

While this discussion emphasizes direct mechanosensing pathways in immune cells, it is important to note that mesenchymal cells, such as fibroblasts, stromal cells, and endothelial cells, also significantly influence immunity through indirect mechanosensing. These mesenchymal cells typically exhibit more pronounced mechanosensing capabilities. For example, fibroblasts detect ECM mechanics and recruit immune cells like macrophages. In endothelial cells, low shear stress from unidirectional blood flow inhibits YAP and TAZ activity, suppressing pro-inflammatory gene expression and reducing monocyte infiltration. Additionally, TRPV4 regulates the degradation of human fibrocytes by modulating the expression of stretch-induced inflammatory factors, including IL-6, IL-8, COX2, MMP1, and MMP3. Understanding the crosstalk between the stroma and immune system, particularly how mechanical signaling connects these two cell populations, is a vital area for future research.

Immune cells encounter various forces in vivo, such as shear, pressure, and tension, which they convert into biochemical signals influencing their function[30]. Monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes can sense mechanical forces. Immunotherapies traditionally target biochemical cues, but “mechanical immune engineering” offers new strategies by enhancing immune cell cancer-fighting capabilities through biophysical manipulation. For T cells, passive cues like ECM stiffness can boost cytokine production, while active forces involve T-cell-generated or external mechanical forces. Disruption of these forces impairs T-cell activation[172]. Innovative methods, such as ultrasound, magnetic forces, photostimulation, and fluid flow, can enhance T-cell activation and immunotherapy effectiveness. However, challenges like microbubble fragility during migration limit in vivo application, necessitating further advancements[173].

Currently, CAR-T cell therapy suffers from cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, and off-target effects. To mitigate these side effects, methods have been used to inhibit CAR-T cell activity through suicide switches or corticosteroids, which may reduce therapeutic efficacy. The University of California, San Diego, has developed light-controlled CAR-T technology (LINTAD), which utilizes blue light as a switch to precisely control CAR-T cell activation. Studies have shown that light-activated LINTAD CAR-T cells have a significant anti-tumor effect on mice transplanted with cancer cells and that blue light can also penetrate the skin to achieve local control in vivo[174]. This technology provides a new direction for precision cancer immunotherapy, helping to enhance efficacy and minimize side effects.

In addition, another team of researchers at the University of California, San Diego, developed a new method for activating CAR-T cells using focused ultrasound. They injected modified CAR-T cells into mouse tumors and activated the cells by heating them to 43 ºC with short pulses of ultrasound while avoiding damage to the surrounding tissue. These CAR-T cells carry a gene that expresses the CAR protein only when exposed to heat. In the experiment, CAR-T cells activated by ultrasound only attacked the target tumor, while standard CAR-T cells affected all tissues expressing the target antigen[175]. This technology effectively solves the problems of precision and safety of CAR-T cells in the treatment of solid tumors and provides a new direction for cancer immunotherapy.

In summary, preclinical trials on mechanical stimulation of immune cells to improve the efficacy of tumor immunotherapy have made some progress and are expected to provide new and effective means for future tumor therapy.

Conclusions and outlook

As tumors progress, changes in tissue mechanics influence immune cell behavior, offering new therapeutic opportunities to enhance immunotherapy. Despite this, the link between tumor mechanical stress, immune cell mechanosensation, and immune evasion remains underexplored. Alterations in the ECM also affect tissue mechanics, making ECM components potential therapeutic targets. While mechanoimmunology is emerging, in vivo measurement of tissue mechanics is still challenging, and many in vitro findings require validation. Advanced technologies like MRI, ultrasound, and AI hold promise for exploring tissue mechanics and informing new therapeutic strategies.

In addition, we can provide a new research direction to overcome immunotherapy resistance of malignant tumors with the help of “mechanical immune engineering system:”

Understanding the Mechanical Immune Engineering System: This emerging field explores how immune cells sense mechanical signals and how these signals impact immune responses. It highlights the role of biomechanics in immune regulation and provides a foundation for novel immunotherapies. A deeper understanding of this system can reveal the biomechanical causes of immunotherapy resistance.

Mechanisms of Immunotherapy Resistance: Tumor tissues exhibit abnormal mechanical properties, like increased stiffness and altered matrix structure, which can hinder immune cell infiltration and function, contributing to therapy resistance. Immune cells, such as T cells and NK cells, may struggle to recognize and kill tumor cells due to disrupted mechanical sensing.

Developing Novel Therapies: Modifying tumor tissue mechanics, enhancing immune cell sensitivity to mechanical cues, and combining these approaches with existing therapies, like checkpoint inhibitors or CAR-T cell therapy, can improve efficacy and overcome resistance.

Personalized Treatment: Given tumor heterogeneity and patient variability, mechanical immune engineering enables personalized strategies by tailoring treatments to individual tumor mechanics and immune profiles.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Advancing this field requires collaboration across biology, medicine, and engineering to drive innovation and improve immunotherapy outcomes.

In conclusion, the mechanical immune engineering system holds promise for developing precise and effective treatments for overcoming tumor immunotherapy resistance.

Acknowledgements

None

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 07 January 2025

Contributor Information

Lin Zhao, Email: 508156@csu.edu.cn.

Yajun Gui, Email: 507799@csu.edu.cn.

Xiangying Deng, Email: DXY1990@csu.edu.cn.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Not applicable.

Sources of funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103653, 82303258, and 82302873), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2022JJ40659, No. 2023JJ40874, and 2022JJ40686), and the Scientific Research Launch Project for new employees of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (QH20230202).

Author’s contribution

L.Z. and X.Y.D. wrote the main manuscript text and Y.J.G. and X.Y.D prepared Figures 1-5. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Xiangying Deng.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

References

- [1].Wu P, Hou X, Peng M, et al. Circular RNA circRILPL1 promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma malignant progression by activating the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ 2023;30:1679–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Deng X, Xiong W, Jiang X, et al. LncRNA LINC00472 regulates cell stiffness and inhibits the migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma by binding to YBX1. Cell Death Dis 2020;11:945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Casal JI, Bartolome RA. RGD cadherins and alpha2beta1 integrin in cancer metastasis: a dangerous liaison. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2018;1869:321–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Feng Y, Liang Y, Zhu X, et al. The signaling protein Wnt5a promotes TGFbeta1-mediated macrophage polarization and kidney fibrosis by inducing the transcriptional regulators Yap/Taz. J Biol Chem 2018;293:19290–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Plodinec M, Loparic M, Monnier CA, et al. The nanomechanical signature of breast cancer. Nat Nanotechnol 2012;7:757–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saraswathibhatla A, Indana D, Chaudhuri O. Cell-extracellular matrix mechanotransduction in 3D. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023;24:495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tsujita K, Satow R, Asada S, et al. Homeostatic membrane tension constrains cancer cell dissemination by counteracting BAR protein assembly. Nat Commun 2021;12:5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Deng X, Xiong F, Li X, et al. Application of atomic force microscopy in cancer research. J Nanobiotechnology 2018;16:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liu Q, Li S. Exosomal circRNAs: novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for urinary tumors. Cancer Lett 2024;588:216759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li S, Kang Y, Zeng Y. Targeting tumor and bone microenvironment: novel therapeutic opportunities for castration-resistant prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2024;1879:189033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Qiu Z-W, Zhong Y-T, Lu Z-M, et al. Breaking physical barrier of fibrotic breast cancer for photodynamic immunotherapy by remodeling tumor extracellular matrix and reprogramming cancer-associated fibroblasts. ACS Nano 2024;18:9713–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Anderson NM, Simon MC. The tumor microenvironment. Curr Biol 2020;30:R921–R5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Baghban R, Roshangar L, Jahanban-Esfahlan R, et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun Signal 2020;18:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Galli F, Aguilera JV, Palermo B, et al. Relevance of immune cell and tumor microenvironment imaging in the new era of immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020;39:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kong Y, Duan J, Liu F, et al. Regulation of stem cell fate using nanostructure-mediated physical signals. Chem Soc Rev 2021;50:12828–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nia HT, Munn LL, Jain RK. Physical traits of cancer. Science 2020;370:eaaz0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cambria E, Coughlin MF, Floryan MA, et al. Linking cell mechanical memory and cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2024;24:216–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sleeboom JJF, van Tienderen GS, Schenke-Layland K, et al. The extracellular matrix as hallmark of cancer and metastasis: from biomechanics to therapeutic targets. Sci Transl Med 2024;16:eadg3840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhang S, Regan K, Najera J, et al. The peritumor microenvironment: physics and immunity. Trends Cancer 2023;9:609–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang S, Grifno G, Passaro R, et al. Intravital measurements of solid stresses in tumours reveal length-scale and microenvironmentally dependent force transmission. Nat Biomed Eng 2023;7:1473–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Martinez A, Buckley M, Scalise CB, et al. Understanding the effect of mechanical forces on ovarian cancer progression. Gynecol Oncol 2021;162:154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Garoffolo G, Pesce M. Mechanotransduction in the cardiovascular system: from developmental origins to homeostasis and pathology. Cells 2019;8:1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].He Y, Liu T, Dai S, et al. Tumor-associated extracellular matrix: how to be a potential aide to anti-tumor immunotherapy? Front Cell Dev Biol 2021;9:739161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Salmon H, Franciszkiewicz K, Damotte D, et al. Matrix architecture defines the preferential localization and migration of T cells into the stroma of human lung tumors. J Clin Invest 2012;122:899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kuczek DE, Larsen AMH, Thorseth ML, et al. Collagen density regulates the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tello-Lafoz M, Srpan K, Sanchez EE, et al. Cytotoxic lymphocytes target characteristic biophysical vulnerabilities in cancer. Immunity 2021;54:1037–54e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kim TH, Gill NK, Nyberg KD, et al. Cancer cells become less deformable and more invasive with activation of beta-adrenergic signaling. J Cell Sci 2016;129:4563–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Basu R, Whitlock BM, Husson J, et al. Cytotoxic T cells use mechanical force to potentiate target cell killing. Cell 2016;165:100–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, et al. Cell softness prevents cytolytic t-cell killing of tumor-repopulating cells. Cancer Res 2021;81:476–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mittelheisser V, Gensbittel V, Bonati L, et al. Evidence and therapeutic implications of biomechanically regulated immunosurveillance in cancer and other diseases. Nat Nanotechnol 2024;19:281–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Du H, Bartleson JM, Butenko S, et al. Tuning immunity through tissue mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Immunol 2023;23:174–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].He X, Yang Y, Han Y, et al. Extracellular matrix physical properties govern the diffusion of nanoparticles in tumor microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023;120:e2209260120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Matthews HK, Ganguli S, Plak K, et al. Oncogenic signaling alters cell shape and mechanics to facilitate cell division under confinement. Dev Cell 2020;52:563–73e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu B, Chen W, Evavold BD, et al. Accumulation of dynamic catch bonds between TCR and agonist peptide-MHC triggers T cell signaling. Cell 2014;157:357–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Radko-Juettner S, Yue H, Myers JA, et al. Targeting DCAF5 suppresses SMARCB1-mutant cancer by stabilizing SWI/SNF. Nature 2024;628:442–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liao J, Pan H, Huang G, et al. T cell cascade regulation initiates systemic antitumor immunity through living drug factory of anti-PD-1/IL-12 engineered probiotics. Cell Rep 2024;43:114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ishay-Ronen D, Diepenbruck M, Kalathur RKR, et al. Gain fat-lose metastasis: converting invasive breast cancer cells into adipocytes inhibits cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell 2019;35:17–32e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Guo X, Gao C, Yang DH, et al. Exosomal circular RNAs: a chief culprit in cancer chemotherapy resistance. Drug Resist Updat 2023;67:100937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Abusalah MAH, Priyanka Abd Rahman ENSE, Abd Rahman ENSE, et al. Evolving trends in stem cell therapy: an emerging and promising approach against various diseases. Int J Surg 2024;110:6862–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kirchhammer N, Trefny MP, Auf der Maur P, et al. Combination cancer immunotherapies: emerging treatment strategies adapted to the tumor microenvironment. Sci Transl Med 2022;14:eabo3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhu S, Zhang T, Zheng L, et al. Combination strategies to maximize the benefits of cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jenkins L, Jungwirth U, Avgustinova A, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts suppress CD8+ T-cell infiltration and confer resistance to immune-checkpoint blockade. Cancer Res 2022;82:2904–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Larroquette M, Guegan JP, Besse B, et al. Spatial transcriptomics of macrophage infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer reveals determinants of sensitivity and resistance to anti-PD1/PD-L1 antibodies. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e003890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu Q, Guan Y, Li S. Programmed death receptor (PD-)1/PD-ligand (L)1 in urological cancers: the “all-around warrior” in immunotherapy. Mol Cancer 2024;23:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu M, Li S. The opportunities and challenges of using PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for leukemia treatment. Cancer Lett 2024;593:216969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chen Z, Yue Z, Yang K, et al. Four ounces can move a thousand pounds: the enormous value of nanomaterials in tumor immunotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater 2023;12:e2300882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zhu X, Li S. Nanomaterials in tumor immunotherapy: new strategies and challenges. Mol Cancer 2023;22:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kang Y, Li S. Nanomaterials: breaking through the bottleneck of tumor immunotherapy. Int J Biol Macromol 2023;230:123159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chen Z, Yue Z, Yang K, et al. Nanomaterials: small particles show huge possibilities for cancer immunotherapy. J Nanobiotechnology 2022;20:484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Priyanka CH, Choudhary OP, Choudhary OP. mRNA vaccines as an armor to combat the infectious diseases. Travel Med Infect Dis 2023;52:102550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Priyanka AMAH, Chopra H, Chopra H, et al. Nanovaccines: a game changing approach in the fight against infectious diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2023;167:115597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Peng M, Mo Y, Wang Y, et al. Neoantigen vaccine: an emerging tumor immunotherapy. Mol Cancer 2019;18:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hou X, Shi X, Zhang W, et al. LDHA induces EMT gene transcription and regulates autophagy to promote the metastasis and tumorigenesis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2021;12:347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Codini M, Garcia-Gil M, Albi E. Cholesterol and sphingolipid enriched lipid rafts as therapeutic targets in cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021:22:726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Das J, Maji S, Agarwal T, et al. Hemodynamic shear stress induces protective autophagy in HeLa cells through lipid raft-mediated mechanotransduction. Clin Exp Metastasis 2018;35:135–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yan Z, Su G, Gao W, et al. Fluid shear stress induces cell migration and invasion via activating autophagy in HepG2 cells. Cell Adh Migr 2019;13:152–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wang X, Zhang Y, Feng T, et al. Fluid shear stress promotes autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Biol Sci 2018;14:1277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nia HT, Liu H, Seano G, et al. Solid stress and elastic energy as measures of tumour mechanopathology. Nat Biomed Eng 2016;1:0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Jones D, Wang Z, Chen IX, et al. Solid stress impairs lymphocyte infiltration into lymph-node metastases. Nat Biomed Eng 2021;5:1426–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Liu Y, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. Hypoxia-induced GPCPD1 depalmitoylation triggers mitophagy via regulating PRKN-mediated ubiquitination of VDAC1. Autophagy 2023;19:2443–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhong H, Yang C, Gao Y, et al. PERK signaling activation restores nucleus pulposus degeneration by activating autophagy under hypoxia environment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:341–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Claude-Taupin A, Isnard P, Bagattin A, et al. The AMPK-Sirtuin 1-YAP axis is regulated by fluid flow intensity and controls autophagy flux in kidney epithelial cells. Nat Commun 2023;14:8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].De Belly H, Paluch EK, Chalut KJ. Interplay between mechanics and signalling in regulating cell fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022;23:465–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Meng Q, Pu L, Qi M, et al. Laminar shear stress inhibits inflammation by activating autophagy in human aortic endothelial cells through HMGB1 nuclear translocation. Commun Biol 2022;5:425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Nasr M, Fay A, Lupieri A, et al. PI3KCIIalpha-dependent autophagy program protects from endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in response to low shear stress in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2024;44:620–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Das J, Chakraborty S, Maiti TK. Mechanical stress-induced autophagic response: a cancer-enabling characteristic? Semin Cancer Biol 2020;66:101–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Liu S, Zhou F, Shen Y, et al. Fluid shear stress induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in Hep-2 cells. Oncotarget 2016;7:32876–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Xin Y, Li K, Yang M, et al. Fluid shear stress induces EMT of circulating tumor cells via JNK signaling in favor of their survival during hematogenous dissemination. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:8115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Tam SY, Wu VWC, Law HKW. Hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancers: HIF-1alpha and beyond. Front Oncol 2020;10:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Chen Q, Yang D, Zong H, et al. Growth-induced stress enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by IL-6 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma via the Akt/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncogenesis 2017;6:e375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Donker L, Houtekamer R, Vliem M, et al. A mechanical G2 checkpoint controls epithelial cell division through E-cadherin-mediated regulation of wee1-cdk1. Cell Rep 2022;41:111475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wang S, Englund E, Kjellman P, et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: CCM3 is a gatekeeper in focal adhesions regulating mechanotransduction and YAP/TAZ signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2021;23:758–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Peng Z, Ding Y, Zhang H, et al. Mechanical force-mediated interactions between cancer cells and fibroblasts and their role in the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Metastatis Treat 2024;10:4. [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lei K, Kurum A, Kaynak M, et al. Cancer-cell stiffening via cholesterol depletion enhances adoptive T-cell immunotherapy. Nat Biomed Eng 2021;5:1411–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chauhan VP, Chen IX, Tong R, et al. Reprogramming the microenvironment with tumor-selective angiotensin blockers enhances cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:10674–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhang T, Jia Y, Yu Y, et al. Targeting the tumor biophysical microenvironment to reduce resistance to immunotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2022;186:114319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Yang C, Dong X, Sun B, et al. Physical immune escape: weakened mechanical communication leads to escape of metastatic colorectal carcinoma cells from macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024;121:e2322479121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wang M, Jiang H, Liu X, et al. Biophysics involved in the process of tumor immune escape. iScience 2022;25:104124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Nia HT, Datta M, Seano G, et al. In vivo compression and imaging in mouse brain to measure the effects of solid stress. Nat Protoc 2020;15:2321–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Kim BG, Gao MQ, Kang S, et al. Mechanical compression induces VEGFA overexpression in breast cancer via DNMT3A-dependent miR-9 downregulation. Cell Death Dis 2017;8:e2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Yang R, Pei T, Huang R, et al. Platycodon grandiflorum triggers antitumor immunity by restricting PD-1 expression of CD8(+) T cells in local tumor microenvironment. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:774440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Voron T, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, et al. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+ T cells in tumors. J Exp Med 2015;212:139–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Qin X, Li J, Sun J, et al. Low shear stress induces ERK nuclear localization and YAP activation to control the proliferation of breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019;510:219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Lee HJ, Diaz MF, Price KM, et al. Fluid shear stress activates YAP1 to promote cancer cell motility. Nat Commun 2017;8:14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Yang Y, Li C, Liu T, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors: from mechanisms to antigen specificity and microenvironmental regulation. Front Immunol 2020;11:1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Shibata M, Ham K, Hoque MO. A time for YAP1: tumorigenesis, immunosuppression and targeted therapy. Int, J, Cancer 2018;143:2133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Ni X, Tao J, Barbi J, et al. YAP is essential for treg-mediated suppression of antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1026–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Sun K, Li X, Scherer PE. Extracellular matrix (ECM) and fibrosis in adipose tissue: overview and perspectives. Compr Physiol 2023;13:4387–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Sugimura K, Lenne PF, Graner F. Measuring forces and stresses in situ in living tissues. Development 2016;143:186–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Vogel V. Unraveling the mechanobiology of extracellular matrix. Annu Rev Physiol 2018;80:353–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Paul CD, Mistriotis P, Konstantopoulos K. Cancer cell motility: lessons from migration in confined spaces. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Vining KH, Mooney DJ. Mechanical forces direct stem cell behaviour in development and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017;18:728–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Hsiai TK, Cho SK, Wong PK, et al. Monocyte recruitment to endothelial cells in response to oscillatory shear stress. FASEB J 2003;17:1648–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Rutkowski JM, Swartz MA. A driving force for change: interstitial flow as a morphoregulator. Trends Cell Biol 2007;17:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ogawa R. Mechanobiology of scarring. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19:s2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Solis AG, Bielecki P, Steach HR, et al. Mechanosensation of cyclical force by PIEZO1 is essential for innate immunity. Nature 2019;573:69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Meng KP, Majedi FS, Thauland TJ, et al. Mechanosensing through YAP controls T cell activation and metabolism. J Exp Med 2020;217:e20200053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Pawlus A, Inglot MS, Szymanska K, et al. Shear wave elastography of the spleen: evaluation of spleen stiffness in healthy volunteers. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016;41:2169–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Roy NH, MacKay JL, Robertson TF, et al. Crk adaptor proteins mediate actin-dependent T cell migration and mechanosensing induced by the integrin LFA-1. Sci Signal 2018;11:eaat3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Kohler R, Heyken WT, Heinau P, et al. Evidence for a functional role of endothelial transient receptor potential V4 in shear stress-induced vasodilatation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26:1495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Li J, Hou B, Tumova S, et al. Piezo1 integration of vascular architecture with physiological force. Nature 2014;515:279–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Le HQ, Ghatak S, Yeung CY, et al. Mechanical regulation of transcription controls polycomb-mediated gene silencing during lineage commitment. Nat Cell Biol 2016;18:864–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Tajik A, Zhang Y, Wei F, et al. Transcription upregulation via force-induced direct stretching of chromatin. Nat Mater 2016;15:1287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Lombardi ML, Jaalouk DE, Shanahan CM, et al. The interaction between nesprins and sun proteins at the nuclear envelope is critical for force transmission between the nucleus and cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 2011;286:26743–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Jain N, Iyer KV, Kumar A, et al. Cell geometric constraints induce modular gene-expression patterns via redistribution of HDAC3 regulated by actomyosin contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:11349–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Versaevel M, Grevesse T, Gabriele S. Spatial coordination between cell and nuclear shape within micropatterned endothelial cells. Nat Commun 2012;3:671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Thery M, Racine V, Piel M, et al. Anisotropy of cell adhesive microenvironment governs cell internal organization and orientation of polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:19771–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Even-Ram S, Doyle AD, Conti MA, et al. Myosin IIA regulates cell motility and actomyosin-microtubule crosstalk. Nat Cell Biol 2007;9:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Wang C, Morley SC, Donermeyer D, et al. Actin-bundling protein L-plastin regulates T cell activation. J Immunol 2010;185:7487–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Klemke M, Wabnitz GH, Funke F, et al. Oxidation of cofilin mediates T cell hyporesponsiveness under oxidative stress conditions. Immunity 2008;29:404–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Thauland TJ, Hu KH, Bruce MA, et al. Cytoskeletal adaptivity regulates T cell receptor signaling. Sci Signal 2017;10:eaah3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Amann KJ, Pollard TD. Direct real-time observation of actin filament branching mediated by Arp2/3 complex using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:15009–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Sridharan R, Cavanagh B, Cameron AR, et al. Material stiffness influences the polarization state, function and migration mode of macrophages. Acta Biomater 2019;89:47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Dutta B, Goswami R, Rahaman SO. TRPV4 plays a role in matrix stiffness-induced macrophage polarization. Front Immunol 2020;11:570195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Geng J, Shi Y, Zhang J, et al. TLR4 signalling via Piezo1 engages and enhances the macrophage mediated host response during bacterial infection. Nat Commun 2021;12:3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Atcha H, Jairaman A, Holt JR, et al. Mechanically activated ion channel Piezo1 modulates macrophage polarization and stiffness sensing. Nat Commun 2021;12:3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Chen M, Zhang Y, Zhou P, et al. Substrate stiffness modulates bone marrow-derived macrophage polarization through NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Bioact Mater 2020;5:880–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Meli VS, Atcha H, Veerasubramanian PK, et al. YAP-mediated mechanotransduction tunes the macrophage inflammatory response. Sci Adv 2020;6:eabb8471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Scheraga RG, Southern BD, Grove LM, et al. The role of TRPV4 in regulating innate immune cell function in lung inflammation. Front Immunol 2020;11:1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Chakraborty M, Chu K, Shrestha A, et al. Mechanical stiffness controls dendritic cell metabolism and function. Cell Rep 2021;34:108609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Baratchi S, Zaldivia MTK, Wallert M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation represents an anti-inflammatory therapy via reduction of shear stress-induced, piezo-1-mediated monocyte activation. Circulation 2020;142:1092–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Morikis VA, Masadeh E, Simon SI. Tensile force transmitted through LFA-1 bonds mechanoregulate neutrophil inflammatory response. J Leukoc Biol 2020;108:1815–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Hu A, Sun L, Lin H, et al. Harnessing innate immune pathways for therapeutic advancement in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024;9:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Zhu C, Chen W, Lou J, et al. Mechanosensing through immunoreceptors. Nat Immunol 2019;20:1269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Blumenthal D, Chandra V, Avery L, et al. Mouse T cell priming is enhanced by maturation-dependent stiffening of the dendritic cell cortex. Elife 2020;9:e55995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Wahl A, Dinet C, Dillard P, et al. Biphasic mechanosensitivity of T cell receptor-mediated spreading of lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:5908–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Saitakis M, Dogniaux S, Goudot C, et al. Different TCR-induced T lymphocyte responses are potentiated by stiffness with variable sensitivity. Elife 2017;6:e23190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Hickey JW, Dong Y, Chung JW, et al. Engineering an artificial T-cell stimulating matrix for immunotherapy. Adv Mater 2019;31:e1807359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Spillane KM, Tolar P. B cell antigen extraction is regulated by physical properties of antigen-presenting cells. J Cell Biol 2017;216:217–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Zeng Y, Yi J, Wan Z, et al. Substrate stiffness regulates B-cell activation, proliferation, class switch, and T-cell-independent antibody responses in vivo. Eur J Immunol 2015;45:1621–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Feske S, Wulff H, Skolnik EY. Ion channels in innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2015;33:291–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, et al. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science 2010;330:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Zheng J. Molecular mechanism of TRP channels. Compr Physiol 2013;3:221–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Michalick L, Kuebler WM. TRPV4-A missing link between mechanosensation and immunity. Front Immunol 2020;11:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Feske S, Giltnane J, Dolmetsch R, et al. Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 2001;2:316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Bueno OF, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME, et al. Defective T cell development and function in calcineurin Aβ-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:9398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Zhou T, Gao B, Fan Y, et al. Piezo1/2 mediate mechanotransduction essential for bone formation through concerted activation of NFAT-YAP1-ss-catenin. Elife 2020;9:e52779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Aykut B, Chen R, Kim JI, et al. Targeting Piezo1 unleashes innate immunity against cancer and infectious disease. Sci Immunol 2020;5:eabb5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Pang R, Sun W, Yang Y, et al. PIEZO1 mechanically regulates the antitumour cytotoxicity of T lymphocytes. Nat Biomed Eng 2024;8:1162–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Wang Y, Yang H, Jia A, et al. Dendritic cell Piezo1 directs the differentiation of T(H)1 and T(reg) cells in cancer. Elife 2022;11:e79957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Meng Z, Qiu Y, Lin KC, et al. RAP2 mediates mechanoresponses of the Hippo pathway. Nature 2018;560:655–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Fu M, Hu Y, Lan T, et al. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Majedi FS, Hasani-Sadrabadi MM, Thauland TJ, et al. T-cell activation is modulated by the 3D mechanical microenvironment. Biomaterials 2020;252:120058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].de la Zerda A, Kratochvil MJ, Suhar NA, et al. Review: bioengineering strategies to probe T cell mechanobiology. APL Bioeng 2018;2:021501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Loebel C, Saleh AM, Jacobson KR, et al. Metabolic labeling of secreted matrix to investigate cell-material interactions in tissue engineering and mechanobiology. Nat Protoc 2022;17:618–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell 2013;154:1047–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Halder G, Dupont S, Piccolo S. Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Totaro A, Panciera T, Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ upstream signals and downstream responses. Nat Cell Biol 2018;20:888–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Panciera T, Azzolin L, Cordenonsi M, et al. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017;18:758–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 2011;474:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Zhou X, Li W, Wang S, et al. YAP aggravates inflammatory bowel disease by regulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization and gut microbial homeostasis. Cell Rep 2019;27:1176–89e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Hu R, Hou H, Li Y, et al. Combined BET and MEK inhibition synergistically suppresses melanoma by targeting YAP1. Theranostics 2024;14:593–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Naik A, Leask A. Tumor-associated fibrosis impairs the response to immunotherapy. Matrix Biol 2023;119:125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Lee CK, Jeong SH, Jang C, et al. Tumor metastasis to lymph nodes requires YAP-dependent metabolic adaptation. Science 2019;363:644–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Lebid A, Chung L, Pardoll DM, et al. YAP attenuates CD8 T cell-mediated anti-tumor response. Front Immunol 2020;11:580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Geng J, Yu S, Zhao H, et al. The transcriptional coactivator TAZ regulates reciprocal differentiation of T(H)17 cells and T(reg) cells. Nat Immunol 2017;18:800–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Takada Y, Ye X, Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biol 2007;8:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Di X, Gao X, Peng L, et al. Cellular mechanotransduction in health and diseases: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023;8:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [159].Sun Z, Guo SS, Fassler R. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. J Cell Biol 2016;215:445–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [160].Byeon SE, Yi YS, Oh J, et al. The role of src kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm 2012;2012:512926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [161].Ben-Shmuel A, Joseph N, Sabag B, et al. Lymphocyte mechanotransduction: the regulatory role of cytoskeletal dynamics in signaling cascades and effector functions. J Leukoc Biol 2019;105:1261–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [162].Comrie WA, Li S, Boyle S, et al. The dendritic cell cytoskeleton promotes T cell adhesion and activation by constraining ICAM-1 mobility. J Cell Biol 2015;208:457–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [163].Matalon O, Ben-Shmuel A, Kivelevitz J, et al. Actin retrograde flow controls natural killer cell response by regulating the conformation state of SHP-1. EMBO J 2018;37:e96264 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [164].Jaumouille V, Cartagena-Rivera AX, Waterman CM. Coupling of beta(2) integrins to actin by a mechanosensitive molecular clutch drives complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 2019;21:1357–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [165].Guenther C, Faisal I, Uotila LM, et al. A beta2-Integrin/MRTF-A/SRF pathway regulates dendritic cell gene expression, adhesion, and traction force generation. Front Immunol 2019;10:1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [166].Shaheen S, Wan Z, Li Z, et al. Substrate stiffness governs the initiation of B cell activation by the concerted signaling of PKCbeta and focal adhesion kinase. Elife 2017;6:e23060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [167].Vartiainen MK, Guettler S, Larijani B, et al. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science 2007;316:1749–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [168].Record J, Malinova D, Zenner HL, et al. Immunodeficiency and severe susceptibility to bacterial infection associated with a loss-of-function homozygous mutation of MKL1. Blood 2015;126:1527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [169].Everts B, Amiel E, Huang SC, et al. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKvarepsilon supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat Immunol 2014;15:323–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [170].Saez A, Herrero-Fernandez B, Gomez-Bris R, et al. Lamin A/C and the immune system: one intermediate filament, many faces. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [171].Donahue DA, Porrot F, Couespel N, et al. SUN2 silencing impairs CD4 T cell proliferation and alters sensitivity to HIV-1 infection independently of cyclophilin a. J Virol 2017;91:10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [172].Adu-Berchie K, Liu Y, Zhang DKY, et al. Generation of functionally distinct T-cell populations by altering the viscoelasticity of their extracellular matrix. Nat Biomed Eng 2023;7:1374–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [173].Lei K, Kurum A, Tang L. Mechanical immunoengineering of T cells for therapeutic applications. Acc Chem Res 2020;53:2777–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [174].Huang Z, Wu Y, Allen ME, et al. Engineering light-controllable CAR T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Adv 2020;6:eaay9209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]