Abstract

Objective

To characterize the clinical features, risk factors, and outcomes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (JIA-U), aiming to improve early detection and management strategies.

Methods

This study conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of JIA patients diagnosed and treated at the Department of Rheumatology at Beijing Children’s Hospital (2016–2023), with subgroup evaluation of JIA-U cases.

Results

Among 1494 JIA patients, 72 (4.82%) developed uveitis. The oligoarticular subtype (OJIA, 47.2%) and enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA, 27.8%) predominated. Uveitis onset occurred at a median of 10 months post-arthritis diagnosis (range: 0–86 months), with 93% manifesting within 4 years. Chronic anterior uveitis was the most frequent phenotype. ANA positivity and HLA-B27 were significantly associated uveitis. First-line acute management involved topical corticosteroids, with methotrexate escalation for severe cases and TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab preferred) for refractory disease. Ocular complications arose in 25.9% during follow-up.

Conclusion

Uveitis, often bilateral and insidious, is a common extra-articular manifestation of JIA. Absent arthritis signs may delay diagnosis, highlighting the need for regular screening and close rheumatology–ophthalmology collaboration to optimize outcomes.

Keywords: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, uveitis, clinical manifestations, treatment, prognosis

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), the most common chronic rheumatic disease in children, is defined as arthritis of unknown etiology persisting ≥6 weeks with onset before age 16 years after exclusion of other causes.1 JIA is characterized primarily by chronic synovial inflammation of the joints, and some subtypes may be accompanied by multiorgan dysfunction, such as involvement of the respiratory system, digestive system, nervous system, and eyes.2 Uveitis caused by ocular involvement is a common extra-articular manifestation of JIA, particularly in oligoarticular JIA (OJIA) and rheumatoid factor-negative polyarticular JIA (pJIA, RF-).3–5 Clinically, it often presents as a chronic course with bilateral involvement and usually without obvious symptoms. The insidious nature of this disease may lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment, potentially resulting in visual impairment or blindness.6 A growing number of research have investigated the pathogenesis of JIA-associated uveitis (JIA-U), particularly in patients with positive anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and HLA-B27.7 As ANA titers rise, the incidence of uveitis appears to increase as well.8 Currently, there remains a paucity of data characterizing subtype-specific differences in JIA-U within Asian populations, particularly in mainland China. This study systematically evaluates the clinical spectrum and prognostic outcomes of JIA-U, with focused comparison between OJIA and enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) subtypes. Our findings aim to enhance clinical recognition, facilitate risk-stratified management, and ultimately improve visual outcomes through timely intervention.

Methods

This single-center retrospective cohort study analyzed clinical data from JIA-U patients treated at Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University (January 2016-May 2023). All cases were diagnosed by pediatric rheumatologists following the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) 2001 classification criteria. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≤16 years old at disease onset; (2) confirmed JIA diagnosis meeting ILAR criteria; and (3) consulted an ophthalmologist and diagnosed with uveitis. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) infectious uveitis (viral, bacterial, parasitic, or mycoplasma-induced); (2) ocular inflammation caused by metabolic diseases; and (3) other rheumatic diseases complicated by uveitis. All clinical data were extracted and reviewed from the hospital’s electronic medical record system. Data collection: (1) Demographics and clinical features: gender, age of arthritis onset, affected joints, ophthalmic examination findings, and ocular complications. (2) Laboratory indicators: C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (CCP) and HLA-B27 status. (3) Therapeutic medications and follow-up. Our study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institution Review Board of Beijing Children’s Hospital (Approval No: IEC-C-006-A04-V.07.2). Written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians prior to data collection.

Statistical analysis and plotting were conducted utilizing SPSS 25.0 software. Measurement data that followed a normal distribution was presented as mean ± standard error, while data that did not follow a normal distribution was presented as median. Count data was expressed as frequency (percentage). Independent sample t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s test were utilized to compare the groups. A p-value <0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

General information: During the 7-year study period, we identified 1,494 JIA cases, with 72 (4.82%) developing uveitis (JIA-U). JIA-U patients showed significantly earlier disease onset (7.01±0.39 years) compared to non-uveitis JIA cases (8.16±0.10 years; p=0.007). Median interval from JIA diagnosis to uveitis is 10 months (range: 0–86 months). Approximately 43.1% (31/72) developed uveitis within the first year after the diagnosis of JIA, and 93% experienced the onset of uveitis within four years of JIA onset. Fifteen patients (20.8%) initially presented to ophthalmology with asymptomatic uveitis, subsequently developing articular manifestations that led to JIA diagnosis during rheumatologic evaluation. The male-to-female ratio was 1:1, suggesting an absence of significant gender differences. The most common subtype of JIA associated with uveitis is OJIA (47.2%), followed by ERA (27.8%). In patients with pJIA, 94% are RF-negative, and RF-negative individuals have a higher likelihood of developing uveitis compared to RF-positive individuals (94% vs 6%; p< 0.001). Patients with systemic JIA (sJIA) exhibit a markedly reduced probability of developing uveitis when compared to non-sJIA patients (0.4% vs 10.8%; p< 0.001).

Ocular manifestations: Anterior uveitis is the most common type, with 64 cases (88.9%), followed by panuveitis (7.0%, 5/72), posterior uveitis (2.8%, 2/72), and intermediate uveitis (1.4%, 1/72). Chronic uveitis represented the most frequent clinical course (72.2%, 52/72), with acute (23.6%, 17/72) and recurrent (4.2%, 3/72) forms being less common. Acute uveitis was significantly more common in ERA patients (53% of acute cases), compared to pJIA (35.3%) and OJIA (11.8%) (p < 0.001). Patients with JIA-U frequently presented with minimal or no ocular symptoms. Of note, 15 patients (20.8%) having intraocular inflammatory lesions identified through ophthalmologic examination despite the absence of subjective ocular complaints. Among those with symptomatic presentation, conjunctival congestion was the most common clinical sign, observed in 38 patients (66.7%), followed by decreased visual acuity in 31 patients (54.4%). Other reported symptoms included photophobia (22.9%), tearing (14.0%), ocular pain (12.1%), foreign body sensation (8.8%), and dry eyes (7.0%).

All patients diagnosed with JIA-U underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic screening evaluation, including assessment of visual acuity, intraocular pressure (IOP), slit lamp examination, and fundus assessment (Figure 1A and B). Based on combined findings from slit-lamp and fundus assessments, bilateral ocular involvement was identified in 63.9% patients (46/72). Corneal adhesions were definitively diagnosed via slit lamp examination in 19 patients, cataracts in 12 cases, corneal banding degeneration in 10, macular edema in 2, and glaucoma in 2. Elevated IOP was detected in 10 patients (13.9%), potentially attributable to intraocular inflammatory cell infiltration, posterior synechiae with pupillary distortion, or peripheral anterior synechiae causing angle closure.

Figure 1.

Ocular manifestations and complications in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. (A and B) Irregular pupil shape, iris synechiae, and visible flare/secretion in the anterior chamber under slit lamp examination. (C) Glaucoma. (D) Cataract.

Laboratory Indicators: Among the cohort, leukocytosis was observed in 13 cases (18.1%), more frequently in OJIA. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) and CRP were found in 15 (20.9%) and 6 patients (8.3%), respectively, while ferritin levels remained normal. Of 69 patients tested for ANA, 46 (66.7%) were positive, with the highest titer (1:2560) primarily in OJIA. A total of 10 individuals (14.3%) tested positive for HLA-B27, half of whom had ERA. All patients with pJIA were subjected to RF testing, which indicated a negative rate of 94%. Furthermore, 57 patients underwent the anti-citrullinated protein antibody (CCP) assay, yielding negative results in 53 cases (93%). Complement C3 and C4 were within normal ranges, and ENA positivity was rare. Clinical and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Information of JIA-Associated Uveitis

| Clinical Information | JIA-U (n=72) | JIA Without Uveitis (n=1422) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.539 | ||

| Male | 36 (50) | 678 (47.7) | |

| Female | 36 (50) | 744 (52.3) | |

| Age (year) | 7.01±0.39 | 8.16±0.1 | 0.007 |

| Subtype of JIA, n (%) | |||

| OJIA | 34 (47.2) | 117(8.2) | <0.001 |

| pJIA (RF-) | 16 (22.2) | 119 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| pJIA (RF+) | 1 (13.9) | 105 (7.4) | 0.053 |

| ERA | 20 (27.8) | 245 (17.2) | 0.022 |

| sJIA | 1 (13.9) | 254 (17.9) | 0.119 |

| Subtype of uveitis | |||

| Bilateral, n(%) | 46 (63.9) | ||

| Course, n (%) | |||

| Acute uveitis | 17 (23.6) | ||

| Chronic uveitis | 52 (72.2) | ||

| Recurrent uveitis | 3 (4.2) | ||

| Anatomical classification, n (%) | |||

| Anterior uveitis | 64 (88.9) | ||

| Intermediate uveitis | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Posterior uveitis | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Panuveitis | 5 (7.0) | ||

| Immunological index, n (%) | |||

| ANA (+) | 46 (66.7) | 156 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| RF (+) | 2 (4.0) | 131 (9.2) | 0.129 |

| Anti-CCP (+) | 4 (7.0) | 169 (12.3) | 0.227 |

| HLA-B27 (+) | 10 (14.3) | 163 (12.2) | 0.617 |

Abbreviations: ANA, antinuclear antibodies; Anti-CPP, citrullinated protein antibody; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen-B27; SE, standard error.

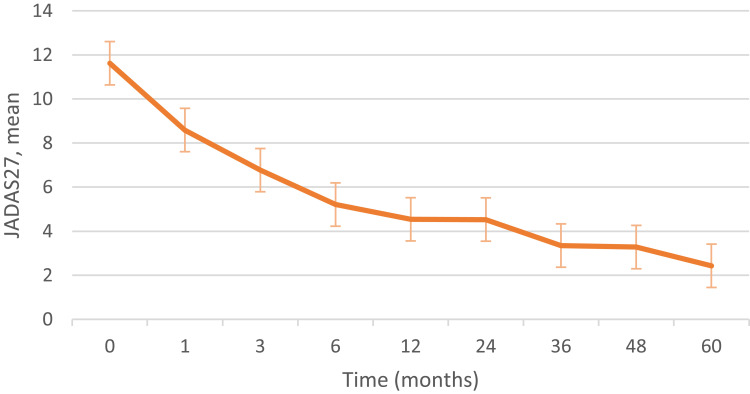

Treatment and follow-up: At the initiation of treatment, 70.8% of patients used topical corticosteroids, and 52.8% received oral glucocorticoids. Immunosuppressants were prescribed to 84.7% of patients, with methotrexate (MTX) accounting for 88.5% of these cases. Biologic agents, all TNF-α antagonists, were initiated in 48 patients (66.7%), with adalimumab being the most common (50%), followed by etanercept (29.2%). Finally, fifty-eight patients had regular follow-up (median 23.7 months; range 1–120 months). Twenty-eight patients were asymptomatic with slit-lamp examinations revealing varying degrees of improvement compared to prior exams, indicating reduced disease activity. During follow-up, 15 patients (25.9%) developed ocular complications, including six new cases (Figure 1C and D). The most common complication observed was iris adhesion. Four patients underwent cataract surgery, and one received peribulbar dexamethasone injections for severe corneal band degeneration. Disease activity scores at follow-up are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The JADAS27 score during follow-up of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis.

Abbreviation: JADAS27, juvenile arthritis disease activity score 27.

Comparison of JIA Subtypes: In this cohort, uveitis was most in patients with OJIA and ERA. To better characterize uveitis in these subtypes, we compared demographics, laboratory features, and clinical outcomes. The female predominance was significantly higher in the OJIA group (67.6%) compared to ERA (15%) (p < 0.01). The mean age of onset was 6.01±0.47 years in OJIA and 9.78±0.7 years in ERA (p<0.001). All ERA patients had symptomatic uveitis, with 45% presenting acutely. In contrast, OJIA-associated uveitis was mostly asymptomatic and chronic. Anatomically, anterior uveitis predominated in both groups, though panuveitis was more frequently observed in OJIA (4 cases, 11.8%) compared to ERA (1 case). Intermediate and posterior uveitis were rare. ANA positivity showed no difference between groups, while HLA-B27 was positive in 1 OJIA (3.0%) and 8 ERA (40%) patients (p = 0.001). At the last follow-up, ocular complications were observed in 10 patients—7 in the OJIA group and 3 in the ERA group. Full details are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with OJIA and ERA with Uveitis

| Clinical Characteristics | OJIA with Uveitis (n=34) | ERA with Uveitis (n=20) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 11 (32.4) | 17 (85) | |

| Female | 23 (67.6) | 3 (15) | |

| Age at diagnosis of JIA, years, mean±SE | 6.01±0.47 | 9.78±0.7 | <0.001 |

| Laterality, n (%) | 0.776 | ||

| Bilateral | 22 (64.7) | 12 (60) | |

| Unilateral | 12(35.3) | 8 (40) | |

| Course, n (%) | |||

| Acute uveitis | 3 (8.8) | 7 (35) | 0.028 |

| Chronic uveitis | 29 (85.3) | 13 (65) | 0.081 |

| Recurrent uveitis | 2 (5.7) | 0 | 0.525 |

| Anatomical classification, n (%) | |||

| Anterior uveitis | 28 (82.4) | 18 (90) | 0.695 |

| Intermediate uveitis | 1 (3.0) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Posterior uveitis | 1 (3.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1.000 |

| Panuveitis | 4 (11.6) | 1 (5.0) | 0.640 |

| Laboratory indicators, n (%) | |||

| ANA (+) | 22 (64.7) | 12 (60) | 0.776 |

| RF (+) | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 0.370 |

| Anti-CCP (+) | 1 (3.0) | 0 | 1.000 |

| HLA-B27 (+) | 1 (3.0) | 8 (50) | 0.001 |

| Complication, n | 7 | 3 | 0.390 |

| Cataract | 0 | 1 | |

| Glaucoma | 0 | 0 | |

| Corneal adhesion | 6 | 2 | |

| Corneal band degeneration | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ANA, antinuclear antibodies; Anti-CPP, citrullinated protein antibody; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen-B27; bDMARD, biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs; CsA, Ciclosporin A; MTX, Methotrexate; MMF, Mycophenolate Mofetil; RF, rheumatic factor; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Uveitis, also known as iridocyclitis, refers to inflammation of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Pediatric uveitis accounts for 5–10% of all uveitis cases and represents the most common cause of childhood blindness. The causes encompass both infectious and non-infectious origins.9 Among the latter, rheumatic diseases are prominent, with JIA-U comprising 15–67% of pediatric uveitis cases.10,11 Chronic anterior uveitis is the most common form of JIA-U, typically involving the iris and ciliary body. Its onset is insidious and may be clinically silent, often leading to severe complications in advanced stages and significantly impairing quality of life.12 Our study provides updated epidemiologic and clinical data from mainland China, addressing a notable gap in Asian pediatric cohorts. The prevalence of uveitis in our cohort (4.82%) aligns with reports from Taiwan (4.7–6.7%) and is lower than that seen in North America and Europe (11.6–20.5%).13–15 Patients with JIA-U present at an earlier age and are more likely to have ocular involvement in the early stages of the disease. Therefore, intensive ophthalmic screening is strongly recommended during the first 4 years following JIA diagnosis. Importantly, 20.8% of patients in this cohort developed uveitis prior to JIA onset. Hence, patients with unexplained uveitis should be evaluated by rheumatology specialists, especially if local therapy is ineffective, to enable early detection of underlying systemic disease.

In this study, no significant association was found between sex and the occurrence of uveitis, which contrasts with earlier reports suggesting a female predominance in JIA-U.16 It has been argued that this observation may simply reflect the higher proportion of female patients in the JIA group most susceptible to uveitis (early onset, ANA-positive), with a relatively lower risk of uveitis in older male JIA patients, who may often eventually be diagnosed with ERA.17 Data from Taiwan indicated that the interaction between arthritis type and gender influenced uveitis risk, with ERA being the predominant subtype and contributing to a higher proportion of affected males.17 Similarly, a Canadian study reported that both age at arthritis onset and sex influenced uveitis incidence, with early-onset, ANA-positive females more likely to develop ocular involvement.18 In our cohort, overall uveitis incidence was similar between sexes. However, risk was higher in males with ERA and in females with OJIA. These findings suggested that female sex is not an independent risk factor for JIA-U.

Chronic anterior uveitis is the most common form of JIA-U, typically presenting bilaterally with insidious onset and minimal clinical symptoms. In this study, 72.2% of patients experienced a chronic course of uveitis, and 88.9% of patients were classified as having anterior uveitis based on anatomical structure. Notably, 20.8%were asymptomatic, with intraocular inflammation detected only through routine ophthalmic screening. Patients with clinical symptoms mainly presented with conjunctival hyperemia and decreased visual acuity. Previous retrospective studies have found that over 80% of patients in JIA cohorts developed anterior uveitis, with bilateral involvement in 60.6–72%19,20 and ocular complications, such as cataracts, glaucoma, synechiae, and band keratopathy, presented in 37.3–56% at diagnosis.19 These findings underscore the importance of early detection and regular screening, as delayed diagnosis due to asymptomatic presentation may lead to irreversible complications. Additionally, in cases of early-onset JIA with atypical features or poor treatment responses, alternative diagnose such as Blau syndrome should be considered. The uveitis of patients with BLAU syndrome is characterized by chronic bilateral granulomatous panuveitis with multifocal chorioretinopathy.21 Over 50% of Blau patients have anterior combined with intermediate or posterior uveitis, while ~30% present with isolated anterior involvement.22 However, JIA-U almost exclusively involves anterior uveitis. Therefore, for refractory cases, it is necessary to inquire in detail whether the patient has a history of rash and family history and perform genetic testing if necessary.

Retrospective studies have indicated ANA positivity as a key risk factor for uveitis in JIA patients.8,23,24 Higher ANA titers, especially ≥1:320, correlate with increased uveitis risk. In this cohort, 66.7% of patients were ANA-positive, which was statistically significant compared to the group without uveitis, consistent with previous research findings. However, ANA positivity and titer do not correlate with the activity or course of JIA-U, as ANA is nonspecific and elevated in other autoimmune disease, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), connective tissue disease, scleroderma, and autoimmune hepatitis.25,26 Analyzing the inflammatory indicators when uveitis was diagnosed in patients, no obvious specificity was found, suggesting that uveitis in patients with JIA may not be completely parallel to the disease activity. According to recent recommendations, including the 2024 Taiwan Ophthalmic Inflammation Society (TOIS) consensus, children with high-risk features—such as ANA positivity, early onset, and OJIA subtype—should undergo ophthalmologic screening every three months for at least four years.27

This cohort employed a step-up approach, starting with topical glucocorticoids, progressing to oral corticosteroids, systemic immunosuppressants, and ultimately to biologics. The mechanism of action is that TNF-α, as a pro-inflammatory cytokine, plays a key role in initiating and maintaining inflammatory responses. Elevated levels of TNF-α can be observed in patients with uveitis, which further promotes the activation and proliferation of inflammatory cells and the release of inflammatory mediators. Adalimumab binds to TNF-α, blocking receptor interaction, reducing inflammation, and modulating T and B cell activation.28,29 Treatment with methotrexate and TNF-α inhibitors, particularly adalimumab, has been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of ocular complications.30 In addition, IL-6 inhibitors (tocilizumab),31 T and B cell inhibitors (abatacept, rituximab),32,33 and JAK inhibitors34 have shown promise in treating JIA-U. Although pediatric data remain limited, early findings suggest potential clinical value. Further large-scale, controlled studies are warranted to confirm their efficacy and safety in children. At last follow-up, about 80% of patients remained on immunosuppressants, biologics, or targeted therapies, with no medication discontinuations. Short-term follow-up revealed an incidence rate of 25.9% for ocular complications, primarily consisting of synechiae, cataracts, and band keratopathy. Compared to previously reported data,10,35 the incidence of complications in this study was relatively lower, and no cases of blindness were observed. Early detection of uveitis, multidisciplinary collaboration, and timely immunosuppressive therapy contributed to favorable outcomes.

Although similar studies have been conducted in Western countries, data from China remain limited. This study provides valuable regional evidence on JIA-U phenotypes and emphasizes the unique clinical profile of ERA and OJIA-associated uveitis in Asian children. However, several limitations should be limited. Due to the low incidence of JIA-U, the relatively sample size may affect our assessment of certain factors. Additionally, the assessment of uveitis partially relies on patients’ clinical descriptions, which may introduce potential bias. This study is a single-center, retrospective study, and some patients lack follow-up data on their treatment, leading to potential bias in treatment protocols.

Conclusion

JIA-associated uveitis (JIA-U) typically presents at a younger age, with a higher risk of early onset, especially in OJIA and ERA. Uveitis is usually chronic and bilateral with subtle symptoms, but ERA patients often develop acute anterior uveitis. Regular ophthalmic screening is essential, starting at JIA diagnosis and continuing long-term according to individual risk. Close collaboration between pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists is crucial for timely diagnosis, coordinated treatment, and improved outcomes in children with JIA-U.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Funding Statement

National Natural Science Foundation of China (92370106).

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the medical ethics committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University (IEC-C-006-A04-V.07.2). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Barut K, Adrovic A, Şahin S, Kasapçopu Ö. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Balk Med J. 2017;34(2):90–101. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.2017.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li C, Huang X, Wang Y, et al. Recommendations of diagnosis and treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in China. Chin J Internal Med. 2022;61(2):142–156. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112138-20210929-00666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke SLN, Sen ES, Ramanan AV. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2016;14(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0088-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leal I, Miranda V, Fonseca C, et al. The 2021 Portuguese society of ophthalmology joint guidelines with pediatric rheumatology on the screening, monitoring and medical treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. ARP Rheumatol. 2022;1(1):49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asproudis I, Katsanos A, Kozeis N, Tantou A, Konstas AG. Update on the treatment of uveitis in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a review. Adv Ther. 2017;34(12):2558–2565. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasumura J, Yashiro M, Okamoto N, et al. Clinical features and characteristics of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Japan: first report of the pediatric rheumatology association of Japan (PRAJ). Pediatr Rheumatol. 2019;17(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0318-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang MH, Shantha JG, Fondriest JJ, Lo MS, Angeles-Han ST. Uveitis in children and adolescents. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2021;47(4):619–641. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2021.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cifuentes-González C, Uribe-Reina P, Reyes-Guanes J, et al. Ocular manifestations related to antibodies positivity and inflammatory biomarkers in a rheumatological cohort. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:2477–2490. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S361243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maleki A, Anesi SD, Look-Why S, Manhapra A, Foster CS. Pediatric uveitis: a comprehensive review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2022;67(2):510–529. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paroli MP, Speranza S, Marino M, Pirraglia MP, Pivetti-Pezzi P. Prognosis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2003;13(7):616–621. doi: 10.1177/112067210301300704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar P, Gupta A, Bansal R, et al. Chronic uveitis in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2022;89(4):358–363. doi: 10.1007/s12098-021-03884-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerriero S, Palmieri R, Craig F, et al. Psychological effects and quality of life in parents and children with jia-associated uveitis. Children. 2022;9(12):1864.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenbaum JT, Asquith M. The microbiome and HLA-B27-associated acute anterior uveitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(12):704–713. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0097-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saurenmann RK, Levin AV, Feldman BM, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcome of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a long‐term followup study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(2):647–657. doi: 10.1002/art.22381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu P-Y, Kang EY-C, Chen W-D, et al. Epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: a multi-institutional study in Taiwan. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31(10):2009–2017. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2022.2162927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marelli L, Romano M, Pontikaki I, et al. Long term experience in patients with JIA-associated uveitis in a large referral center. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:682327. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.682327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvounis PE, Herman DC, Cha S, Burke JP. Incidence and outcomes of uveitis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, a synthesis of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(3):281–290. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0087-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saurenmann RK, Levin AV, Feldman BM, Laxer RM, Schneider R, Silverman ED. Risk factors for development of uveitis differ between girls and boys with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1824–1828. doi: 10.1002/art.27416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heiligenhaus A, Niewerth M, Ganser G, Heinz C, Minden K, German Uveitis in Childhood Study Group. Prevalence and complications of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a population-based nation-wide study in Germany: suggested modification of the current screening guidelines. Rheumatology. 2005;46(6):1015–1019. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angeles-Han ST, McCracken C, Yeh S, et al. Characteristics of a cohort of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and JIA-associated uveitis. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2015;13(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12969-015-0018-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suresh S, Tsui E. Ocular manifestations of Blau syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020;31(6):532–537. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarens IL, Casteels I, Anton J, et al. Blau syndrome–associated uveitis: preliminary results from an international prospective interventional case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;187:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh JG, Tawansy KA, Rao NA. Immunohistochemical study of chronic nongranulomatous anterior uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(10):1833–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CS, Roberton D, Hammerton ME. Juvenile arthritis-associated uveitis: visual outcomes and prognosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39(6):614–620. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(04)80026-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Wu H, Liu X, Jia H, Lu H. Effect of LPS on cytokine secretion from peripheral blood monocytes in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis patients with positive antinuclear antibody. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2021/8930813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalinina Ayuso V, Makhotkina N, Van Tent-Hoeve M, et al. Pathogenesis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis: the known and unknown. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(5):517–531. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W-D, Wu C-H, Wu P-Y, et al. Taiwan ocular inflammation society consensus recommendations for the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2024;123(12):S0929664624001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li B, Yang L, Bai F, Tong B, Liu X. Indications and effects of biological agents in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Immunotherapy. 2022;14(12):985–994. doi: 10.2217/imt-2021-0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bani Khalaf I, Jain H, Vora NM, et al. A clearer vision: insights into juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis. Proc. 2024;37(2):303–311. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2024.2305567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Jones AP, et al. Adalimumab in combination with methotrexate for refractory uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23(15):1–140. doi: 10.3310/hta23150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maleki A, Manhapra A, Asgari S, et al. Tocilizumab employment in the treatment of resistant juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(1):14–20. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1817501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birolo C, Zannin ME, Arsenyeva S, et al. Comparable efficacy of abatacept used as first-line or second-line biological agent for severe juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(11):2068–2073. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.151389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng CC, Sy A, Cunningham ET. Rituximab for non-infectious Uveitis and Scleritis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2021;11(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12348-021-00252-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miserocchi E, Giuffrè C, Cornalba M, et al. JAK inhibitors in refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(3):847–851. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04875-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabri K, Saurenmann RK, Silverman ED, Levin AV. Course, complications, and outcome of juvenile arthritis–related uveitis. J AAPOS. 2008;12(6):539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]