Abstract

Background

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) play an important role in the development of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), and improving its progression by targeting the activation and regulation of NETs-related genes (NETRGs) might be an important therapeutic target and deserve further exploration.

Methods

Differentially expressed NETRGs (DENETRGs) were obtained by intersecting the NETRGs and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between DFUs and healthy control (HC) samples. The nomogram was constructed with the biomarkers identified by machine learning algorithms. In addition, the immune infiltration was conducted to further analyze the pathogenesis of DFUs. We used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to verify the expression of the biomarkers.

Results

S100A12 and HPSE were defined as the biomarkers of DFUs, and both were significantly highly expressed in DFUs groups. Moreover, the diagnostic model with two biomarker was constructed. Besides, the proportion of the type 17 T helper cell and neutrophil were significantly increased, and the proportion of activated B cell was significantly decreased in the DFUs groups.

Conclusion

This study revealed the potential molecular mechanisms of NETRGs in DFUs, which could provide novel insights for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of DFUs.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcers, neutrophil extracellular traps-related genes, diagnosis, immune infiltration, function, mechanism

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus poses a significant global public health issue. In recent years, its prevalence has been increasing at a remarkable rate.1,2 Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) represent a severe complication of diabetes mellitus, associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.3 It typically appears as an ulcer, most commonly found on the plantar surface of the foot.4 Approximately 19% to 34% of diabetic patients will develop a DFUs during their lifetime, significantly increasing the risk of lower limb amputation.5–7 The annual incidence of DFUs ranges from 1.0% to 4.1%, with a prevalence of 4.6% in clinical settings.8,9 Furthermore, the mortality rate for patients with DFUs is alarmingly high, with 5.0% of patients with new ulcers dying within 12 months and 42.2% within five years.10 Current management strategies for DFUs include glycemic control, debridement, infection control, and offloading, but these measures often fall short in preventing complications and ensuring effective healing.7,11–15 Proper management of DFUs lowers the risk of amputations and hospitalizations, which in turn reduces healthcare costs.16 DFU biomarkers, as indicative characteristics of the pathogenesis of diabetic wounds, can enhance the understanding of DFU, facilitate early clinical diagnosis and forecast disease progression for DFU.17 Studies have shown that the levels of serum CRP, IL-6, fibrinogen, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and white blood cell have been identified as useful parameters for the diagnosis of infected diabetic foot ulcer.17,18 However, the research on biomarkers in DFU is still in its early stage.17 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new and effective biomarkers for the accurate diagnosis of DFUs.

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are web-like structures composed of DNA, histones, and antimicrobial proteins released by activated neutrophils to trap and kill pathogens.19 At the beginning, research regarding NETs mainly concentrated on their antimicrobial capabilities. But later on, it was found out that NETs also have crucial functions in a wide range of diseases.20 At present, NETs have emerged as a critical factor in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases,19,21 including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and atherosclerosis.20 However, excessive or dysregulated NET formation can lead to tissue damage and exacerbate inflammation.19 Considering the fact that NETs have a dual function, being involved in both host defense and the development of diseases, they are thus likely to be important targets for therapeutic approaches.22,23 Comprehending the subtle equilibrium between the advantageous and harmful impacts of NETs is crucial for formulating efficient strategies to regulate them within diverse clinical scenarios.23 Recent studies have identified specific NET-related genes and proteins that may serve as biomarkers for disease severity and therapeutic targets.24,25 In the context of diabetes, NETs have been implicated in impaired wound healing and chronic inflammation, suggesting a potential role in the pathogenesis of DFUs.26–28 Heparanase (HPSE) is an endo-beta-D-glucuronidase capable of cleaving heparan sulfate and is associated with inflammation, wound healing and angiogenesis.29,30 S100A12, also known as EN-RAGE (extracellular newly identified RAGE ligand), mediates inflammation through its interaction with a multiligand RAGE.31

In this study, we integrated NETs-related genes (NETRGs) from the literature with transcriptomic data of DFUs from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO) database, performing functional enrichment analysis and machine learning on differentially expressed NETs-related genes (DENETRGs). This study combines the the least absolute shrinkage selector operator (LASSO), support vector machine-random forest (SVM-RF) and Boruta algorithms for cross-validation to enhance the reliability of feature screening and provide methodological references for similar studies. We identified biomarkers associated with DFUs and constructed a novel clinical diagnostic model, providing potential targets for clinical diagnosis. Additionally, through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and immune cell infiltration analysis, we explored the functions of biomarkers and the pathogenesis of DFUs. Finally, we constructed a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) regulatory network for biomarkers and predicted potential drugs, further revealing the molecular mechanisms and providing a theoretical basis for a deeper understanding of the driving mechanisms of DFUs. This study systematically reveals the core role of NETRGs in DFUs, providing a new perspective for understanding the complex interaction mechanism in the chronic inflammatory microenvironment and contributing to the further improvement of the existing research system in this field.

Materials and Methods

Data Extraction and Pre-Processing

Totals of 69 NETRGs were selected from previous studies.32 Three microarray datasets were obtained from the GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) based on the following criteria: Firstly, the included datasets must be derived from patients suffering from DFUs. Secondly, the samples should be wound tissue biopsies. Consequently, the GSE134431 dataset (number of diabetic foot ulcers (NDFUs) = 13, number of healthy control (NHC) = 8), GSE68183 dataset (NDFUs = NHC = 3), and GSE80178 dataset (NDFUs = 9, NHC = 3) were extracted. Among them, the GSE134431 dataset was used as the training dataset. The GSE68183 and GSE80178 datasets were combined and removed batch effect by using the “combat” function of the “sva” R package (version 3.48.0), and combined dataset (NDFUs =12, NHC = 6) was used as the validation dataset.17

Functional Enrichment Analysis of DENETRGs

The mRNA expression levels in GSE134431 dataset were compared by the “DEseq2” R package (version 1.40.2) (|log2Fold change| > 0.585, p < 0.05),33,34 and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in DFUs were obtained. The “DESeq2” package is used to analyze differentially expressed genes in RNA-Seq data. It is based on the negative binomial distribution model and can effectively handle the variability and technical duplication among samples.33 The “ggplot2” package (version 3.4.2)35 and “pheatmap” package (version 1.0.12)36 were utilized to draw volcano map and heat map respectively to show the expression levels of DEGs. Then, the DENETRGs were obtained by intersecting the DEGs and NETRGs. In addition, the genomic locations of these DENETRGs in chromosomes were determined using “RCircos” package (version 1.2.2).37

Subsequently, the correlation analysis among the expression levels of DENETRGs was performed by the “base” R package (version 4.3.1). Moreover, the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of DENETRGs was constructed by “STRING” website (https://cn.string-db.org/) (Maximum number of interactors = 0, Confidence > 0.25).38 Furthermore, the functional enrichment analysis of these DENETRGs was conducted by “clusterprofiler” R package (version 4.8.2) (adj.p < 0.05),39 including Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. clusterProfiler is a software package used for characterizing and interpreting omics data. Functional enrichment can be achieved through overexpression or gene set enrichment analysis.40

Screening for the Biomarkers of DFUs

In this study, the importance ranking and the best combination of DENETRGs were calculated by three machine learning algorithms. Then, the candidate genes were obtained by intersecting the results of these three algorithms (LASSO),41,42 SVM-RF,41,43 and Boruta44,45). LASSO analysis was carried out using the “glmnet” package (version 4.1–8), with 3-fold cross-validation. Lambda.min was chosen as the final fitting model.46,47 The LASSO method is used to identify basic features from large-scale data and screen gene models.48 This method involves a cross-validation process to determine the optimal regularization parameter (λ), thereby balancing the bias-variance trade-off and improving the prediction accuracy of the model.49 SVM-RF analysis was conducted using the “caret” package (version 6.0–94).50 The feature subset was gradually optimized by recursively eliminating the features that made the least contribution to the model.51 The Boruta algorithm provided by the “Boruta” package (version 8.0.0) was utilized for feature selection to identify important feature genes.52 Boruta is a feature selection algorithm that randomly destroys each true feature in sequence to evaluate the importance of each feature.53 The expressions levels of the candidate genes between DFUs and healthy control (HC) were compared by “rank-sum test” in both training and validation datasets, and the genes with the consistent expression were defined as the target genes for subsequent analyses. In order to study the ability to distinguish the DFUs of target genes and found the biomarkers of DFUs, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of each target genes were drawn by “pROC” R package (version 1.18.4) in both training and validation datasets.54 Then, based on the biomarkers, the diagnostic model (nomogram) was constructed with the biomarkers by “rms” R package (version 6.7–0).55 Then, the calibration curve, decision curve analysis (DCA) curve, and the ROC curve of nomogram were drawn to verify the validity of this model.

The Function Analysis of Biomarkers and Immune Micro-Environment Analysis

On the one hand, the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed for further studying the function of biomarkers according to the median expression value (q < 0.25, p < 0.05). On the other hand, the proportions of 28 immune cells were calculated using the ssGSEA algorithm, and compared between DFUs and HC samples (p < 0.05). Then, the correlations between biomarkers and differential immune cells were explored by Spearman correlation analysis.

Construction of the ceRNA Regulatory Networks and Drug Prediction

The targeted microRNAs (miRNAs) were predicted in miRDB database (http://mirdb.org/), and the targeted long non-coding RNA (lncRNAs) were predicted in StarBase (v2.0) database (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/). Then, the ceRNA networks were constructed by “Cytoscape” software (version 3.7.2).56 In addition, the targeted drugs of biomarkers were predicted in Drug-Gene Interaction database (DGIdb, http://www.dgidb.org/). The selected key genes that were considered potential pharmaceutical targets for DFUs treatment were imported into DGIdb to explore existing drugs or small organic compounds. Finally, Pubchem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was used to predict the secondary structure of drugs. We entered the chemical names of the drugs in the PubChem search box and downloaded the secondary structure diagram of the drug in the compound summary interface.

Validation of the Expression of Biomarkers

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed to validate the expression of biomarkers between DFUs and HC tissue samples, which were obtained from the Chenggong Hospital affiliated to Xiamen University. The specific information of included patients can be found in Table S1. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Chenggong Hospital affiliated to Xiamen University, Ethics number: 73JYY2024145244. Total RNA was extracted using TRIZol (Thermo Fisher, Shanghai, CN), and mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed using SureScript-First-strand-cDNA-synthesis-kit (Servicebio, WuHan, CN). Simultaneously, the internal reference gene GAPDH was utilized to guarantee that the qRT - PCR outcomes could precisely mirror the expression levels of biomarkers. The primer sequences of biomarkers and GAPDH were displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer Used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Primer (5’→ 3’) |

|---|---|

| HPSE | F: CGCTGATGCTGCTGCTCCTG |

| R: AGCGGCTCCTGGGTGAAGAAG | |

| S100A12 | F: ACTCAGTTCGGAAGGGGCATTTTG |

| R: TGATGGTGTTTGCAAGCTCCTTTG | |

| GAPDH | F: GTGGACCTGACCTGCCGTCTAG |

| R: GAGTGGGTGTCGCTGTTGAAGTC |

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using R language (https://www.r-project.org/). Differences between DFUs and HC groups were compared by “wilcoxon” test. To examine the relationship between the expression levels of biomarkers and immune cells, a Spearman correlation was applied. In qRT-PCR experiments, the 2−ΔΔCt method was used to determine gene expression levels. If not specified above, p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

DENETRGs Were Associated with TNF, AGE-RAGE Signaling Pathways

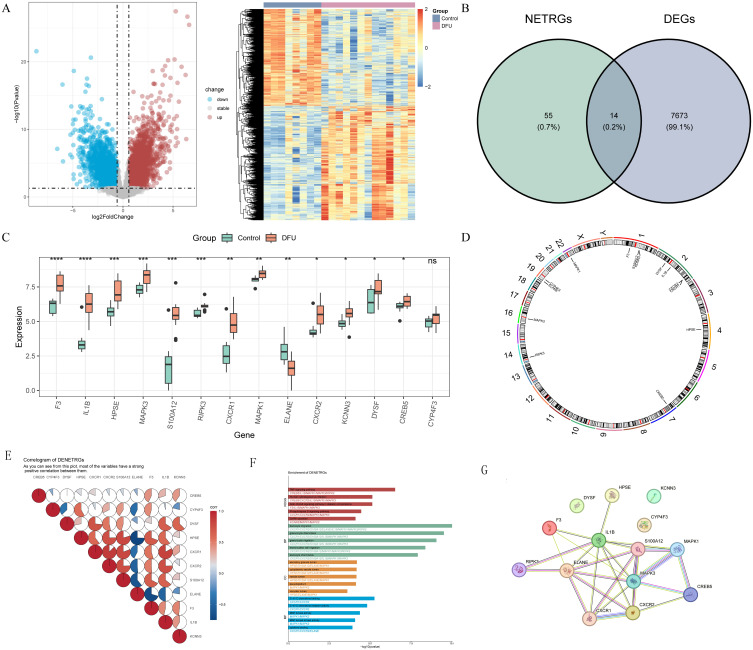

There were 7,687 DEGs (4,162 up-regulated and 3,525 down-regulated) between 13 DFUs and 8 HC samples in GSE134431 dataset (Figure 1A). Then, 14 DENETRGs, including CREB5, CXCR1, CXCR2, CYP4F3, DYSF, ELANE, F3, HPSE, IL1B, KCNN3, MAPK1, MAPK3, RIPK3, and S100A12 were obtained by intersecting 7,687 DEGs and 69 NETRGs (Figure 1B). All these DENETRGs were up-regulated in GSE134431 dataset, except for ELANE (Figure 1C). Besides, we found that most of these DENETRGs were located on the Chromosomes 1 and 2 (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Identification of differentially expressed neutrophil extracellular traps-related genes (DENETRGs) from the GSE134431 dataset. (A) The volcano map and heat map of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) and healthy control (HC) samples. (B) The Venn diagram of DENETRGs obtained by intersecting DEGs and NETRGs. (C) The expression discrepancies of DENETRGs between DFU and HC groups. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. (D) The chromosomal localization analysis of DENETRGs. (E) The pie chart illustrating the relevance between DENETRGs. (F) The GO terms and KEGG pathways enriched in DENETRGs. (G) The PPI network of DENETRGs.

The correlation analysis results among the expression levels of DENETRGs were showed in Figure 1E, and the correlations between HPSE and CXCR1, HPSE and CXCR2, HPSE and S100A12, CXCR1 and CXCR2, CXCR1 and S100A12, CXCR2 and S100A12 were found to be higher. To further understand the molecular mechanisms involved in the development of DFUs, we performed functional enrichment analysis. GO analysis results showed that these DENETRGs were enriched in 614 entries (Table S2), such as granulocyte chemotaxis, granulocyte migration, C-X-C chemokine binding. And KEGG analysis showed that these DENETRGs were associated with 126 pathways (Table S3), such as TNF, AGE-RAGE signaling pathways, GnRH secretion. (Figure 1F). The PPI network of these DENETRGs was constructed with 14 nodes and 27 protein interaction relationship pairs (Figure 1G).

The Diagnostic Model of DFUs Constructed with S100A12 and HPSE

The characteristic genes of DFUs were screened by three kinds of machine learning. First, through LASSO analysis, HPSE, S100A12, F3, IL1B, and RIPK3 were defined as the characteristic genes 1 (Lambda.min = 0.024). IL1B, S100A12, F3, CXCR1, and HPSE were defined as the characteristic genes 2 (Variables = 5, AccuracyMAX = 0.97) by SVM-RF analysis, and HPSE, CXCR1, CXCR2, S100A12, F3, IL1B, MAPK3, RIPK3 were defined as the characteristic genes 3 by Boruta analysis (Figure 2A–C). Then, the intersection of these characteristic genes was selected, and totals of four candidate genes, including IL1B, S100A12, F3, and HPSE were screened for following analysis (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Screening of candidate biomarkers by machine learning algorithms. (A) Tuning parameter selection via 10-fold crossvalidation with minimum criteria in the LASSO model; LASSO coefficient profiles of genes. (B) The SVM-RFE cross-validation curve. (C) The line chart depicting the temporal evolution of variable importance scores during the execution of the Boruta algorithm, along with a box plot illustrating the distribution of variable importance. (D) The Venn graph of candidate gene.

The expression levels of all four candidate genes were significantly higher in the DFUs groups compared to the validation dataset (combined dataset) (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A and B). However, only S100A12 and HPSE exhibited area under curve (AUC) values greater than 0.7 in both the training and validation dataset, thereby establishing them as biomarkers for DFUs (Figure 3C and D). These findings demonstrated that these biomarkers possess diagnostic value for DFUs. In addition, the qRT-PCR results showed that S100A12 and HPSE were significantly highly expressed in DFUs groups compared to HC groups (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Identification and validation of biomarkers for DFU. (A and B) Comparison of the expression levels of candidate genes between the DFU and HC groups in the training (A) and validation (B) sets. not significant; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. (C and D) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves biomarkers in the training (C) and validation (D) sets. (E) The expression of biomarkers in clinical samples. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Based on the training dataset, the nomogram was constructed with two biomarkers (Figure 4A), the calibration curve of the nomogram showed that the slope closed to 1, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC value) of nomogram was 0.962 (Figure 4B), which indicated that the nomogram model had an accurate predictive power and could be used as an effective diagnostic mode. In addition, to verify the generality and reliability of the nomogram in dataset from different sources. We further constructed a nomogram based on the validation dataset (Figure S1). The calibration curve of the nomogram was also close to 1, and the AUC value in the ROC curve of the nomogram was as high as 1.000, although this indicated potential overfitting. However, it is sufficient to prove that the constructed model has high prediction accuracy and reliability (Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Construction of the nomogram. (A) The nomogram constructed based on two biomarkers (S100A12 and HPSE). (B) The calibration curve, decision curve analysis (DCA) curve, and ROC curve of nomogram.

The Function Analyses of Biomarkers

To further understand the pathologic mechanisms of these biomarkers in DFUs patients, we further performed GSEA analysis. The results of GSEA enrichment analysis of two biomarkers were shown in the Figure 5A and B and Table S4. The results revealed that the expressions of S100A12 were significantly positively correlated with the functions of galactose metabolism, IL−17 signaling pathway, etc., and significantly negatively correlated with the functions of linoleic acid metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, etc. Similarly, the expressions of HPSE were significantly positively correlated with the functions of linoleic acid metabolism, steroid biosynthesis, etc., and significantly negatively correlated with the functions of complement and coagulation cascades, glycosphingolipid biosynthesis, etc.

Figure 5.

GSEA enrichment analysis of biomarkers. (A) S100A12; (B) HPSE.

The Level of Type 17 T Helper Cell, Neutrophil, and Activated B Cell Could Be Significantly Changed by DFUs

To explore the changes in the immune microenvironment of DFUs patients and develop novel immunomodulatory strategies, we performed immune cell infiltration analysis. The type 17 T helper (Th17) cell and neutrophil were significantly increased, and the activated B cell was significantly decreased in the DFUs groups (Figure 6A and B). Besides, there were positive correlations between S100A12 and Th17 cell (p < 0.05), between S100A12 and neutrophil (p < 0.01), between HPSE and neutrophil (p < 0.01). There was negative correlation between S100A12 and activated B cell (p < 0.05), between HPSE and activated B cell (p < 0.001) (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Immune infiltration analysis. (A) The stacked bar graph depicting the immune cell scores of 28 samples from DFU and HC groups. (B) Comparison of estimated proportion of immune cells between DFU and HC groups. not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (C) Correlation heat map of differential immune cells and biomarkers.

The ceRNA Regulatory Network and Potential Drugs of Biomarkers

In order to reveal the complex mechanism of biomarker interaction in the cell and further understand the regulatory mechanism of biomarkers in DFUs, we conducted a ceRNA regulatory network analysis. The ceRNA regulatory network was constructed with 6 miRNAs, 4 lncRNAs, and 2 biomarkers (Figure 7 and Table S5). In this network, there were 3 miRNAs (hsa-miR-4282, hsa-miR-3163, and hsa-miR-373-5p) of HPSE and 3 miRNAs (hsa-miR-1224-5p, hsa-miR-574-5p, and hsa-miR-5589-5p) of S100A12. Moreover, AL137782.1 and NR2F1-AS1 could regulate hsa-miR-3163 at the same time, XIST and PPP1R14B-AS1 could regulate hsa-miR-574-5p at the same time. Furthermore, there were 5 targeted drugs (eg Ubrogepant, Eptinezumab, Atogepant) of S100A12 and 17 targeted drugs (eg Amopyroquine, Hesperidin, Astemizole) of HPSE (Figure 8A). The secondary structure of these drugs was predicted, as shown in Figure 8B.

Figure 7.

The ceRNA regulatory network of biomarkers. The yellow square represents mRNA, the red circle represents miRNA, the blue triangle represents lncRNA, and the lines represent the interaction between the two molecules.

Figure 8.

Prediction of targeted drugs for DFU. (A) The drug-biomarker network. The yellow graph represents biomarkers and the blue represents targeted drugs. (B) The secondary structure of drugs.

Discussion

At present, the research and treatment technology in the field of diabetes have made remarkable progress. At the level of genetic research, genes such as GIPR have been found to be associated with diabetes risk.57 An important breakthrough has been made in the application of nanotechnology in the treatment of DFUs.6 With regard to diabetes complications, some risk factors associated with diabetic retinopathy, including age, red blood cells, hemoglobin, have been identified, providing support for early clinical identification and intervention.2 However, DFUs represents a severe complication of diabetes mellitus that profoundly affects patients’ health and quality of life. DFUs is associated with an increased risk of infections and higher likelihood of lower limb amputations, leading to prolonged hospitalizations and elevated mortality rates.58 Considering the grave consequences of DFUs, there is an urgent requirement for enhanced diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to effectively manage this condition. Neutrophils and NETs play pivotal roles in the immune response and inflammatory processes, which are significantly implicated in the pathophysiology of DFUs.24–26 The formation process of NETs, known as NETosis.59 In diabetes patients, the levels of NETs-related products in the bloodstream are markedly increased, and these results validate the connection between NETosis and diabetic complications such as the impaired healing of diabetic wounds, diabetic retinopathy, and atherosclerosis.60,61 Elevated levels of NETs markers were observed in the retinal tissue of diabetic mice, as well as in the fibrovascular epiretinal membranes, vitreous fluid, and blood serum of individuals with proliferative diabetic retinopathy.62 Studies have shown that NETs play a key role in atherosclerosis and that NETs promote plaques in atherosclerosis.63 This study aims to identify genes associated with NETs in the context of DFUs by integrating transcriptomic data and employing advanced bioinformatics approaches. The objective is to uncover novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets that can enhance the clinical management of DFUs and reduce its associated morbidity and mortality rates.

Functional enrichment analysis revealed the identification of 14 DENETRGs (CREB5, CXCR1, CXCR2, CYP4F3, DYSF, ELANE, F3, HPSE, IL1B, KCNN3, MAPK1, MAPK3, RIPK3, and S100A12) associated with DFUs, involving several key signaling pathways including the TNF and AGE-RAGE pathways. The TNF signaling pathway plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of DFUs due to its involvement in the inflammatory response. For instance, TNF-α, as a major pro-inflammatory cytokine, is elevated in DFUs tissues and contributes to chronic inflammation and impaired wound healing.64 The AGE-RAGE signaling pathway is another key pathway that exacerbates DFUs by promoting oxidative stress and inflammation, further impeding the healing process.65,66 Particularly, S100A12 and HPSE emerge as potential biomarkers for DFUs, with significantly elevated expression levels in DFUs samples compared to HC. This elevation is corroborated by high AUC values in both the training and validation sets, indicating their diagnostic potential.

HPSE is an endo-β-D-glucuronidase that degrades the glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate (HS).67 Active HPSE has been reported to affect the transcription of genes related to T cell migration and associated immune responses.68 HPSE has also been found to influence the transcription of genes encoding enzymes involved in glucose metabolism.69 HPSE is extensively involved in immune responses and inflammation development by regulating HS, specifically including the regulation of leukocyte activation, migration, and the release of cytokines/chemokines.70–72 Studies also indicate that HPSE plays a significant role in the development of diabetes-related diseases such as diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, and diabetic atherosclerosis.73–78 These studies indicate that HPSE is extensively involved in the occurrence and development of inflammation, immunity, and various complications of diabetes. Furthermore, it is plausible to propose that HPSE may also play a significant role in impaired diabetic wound healing and potentially regulate the inflammatory response during the wound healing process. In the current study, HPSE exhibited significant differential expression in both the training and validation groups, which was corroborated by subsequent qRT-PCR analysis. Therefore, we infer that the high expression of HPSE in DFUs patients may be a factor contributing to delayed wound healing. To date, there are no studies on the specific functions of HPSE in diabetic wound healing, necessitating further research to elucidate the precise mechanisms by which it exerts its effects.

S100A12, is a member of the S100/calgranulin family and one of the ligands for RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products.79 The pro-inflammatory and chemotactic protein S100A12 has been implicated in various chronic inflammatory conditions,80 autoimmune diseases,79 as well as cardiovascular diseases.81 The relationship between S100A12 and diabetes is also very close. Studies have shown that the blood concentration of S100A12 is associated with diabetes biomarkers such as HbA1c and fasting blood glucose concentration.82 Kislinger et al83 also reported that the expression of S100A12 in the aorta and kidneys of diabetic patients is increased compared to non-diabetic individuals, suggesting that S100A12 may contribute to diabetic microangiopathy and accelerated atherosclerosis; Burke et al observed higher S100A12 expression in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease compared to those without diabetes.84 These studies confirm the close relationship between S100A12 and diabetes and inflammation, which indirectly suggests its potential role in the healing process of diabetic chronic wounds. In this study, the high expression of S100A12 in diabetic wound groups from two independent GEO datasets also confirmed its potential as a biomarker. The mechanism by which blood glucose-related factors lead to increased S100A12 protein levels is not yet clear. In diabetic wounds, hyperglycemia may stimulate the production of S100A12 protein in granulocytes, monocytes, or other cells. Studies have shown that PAI-1, TNF, and IL-6 are elevated in diabetic patients.85–87 Among these molecules, TNF and IL-6 have been confirmed to upregulate S100A12 expression in monocytes and macrophages,88,89 and the specific mechanisms need to be further studied.

GSEA further revealed that S100A12 is positively correlated with galactose metabolism and the IL-17 signaling pathway, and negatively correlated with linoleic acid metabolism and tyrosine metabolism, which is consistent with the pro-inflammatory nature of S100A12. HPSE, on the other hand, shows a positive correlation with linoleic acid metabolism and steroid biosynthesis, and a negative correlation with the complement and coagulation cascades, as well as glycosphingolipid biosynthesis. Interleukin-17 (IL-17) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is secreted primarily by T cells and plays a key role in the inflammatory phase of wound healing. The stimulation of MAPK pathways by IL-17 can result in augmented cellular responses essential for wound healing, including cell migration and proliferation. Although IL-17 helps to clear pathogens in the early stages of inflammation, excessive IL-17 signalling may lead to chronic inflammation, which can impair wound healing.90,91 Linoleic acid is a polyunsaturated fatty acid involved in inflammation and cell membrane synthesis. Linoleic acid influences different stages of wound healing by modulating immune response and cell migration.92–94 These findings suggest that S100A12 and HPSE may play complex roles in the metabolic and signaling pathways related to inflammation, immunity, and tissue repair. Further experimental research is needed to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these associations.

The immune microenvironment plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of DFUs,95 with significant alterations observed in the levels of Th17 cells, neutrophils, and activated B cells. Th17 cells, a subset of CD4+ T helper cells, are well-recognized for their role in autoimmune diseases and inflammation through the secretion of IL-17. Studies have revealed a significant correlation between diabetes and increased expression of inflammatory Th17 cells,96,97 and it has been demonstrated that decreasing Th17 can reduce the pathogenicity of diabetes,98 alleviate inflammation, and improve tissue repair in diabetes.99 In our DFUs study, we found a significant increase in Th17 cells, which was associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and exacerbated tissue damage. This finding is consistent with previous research, indicating that IL-17 can promote chronic inflammation and impede wound healing by enhancing the recruitment and activation of neutrophils. Neutrophils, the first responders in the innate immune system, are essential for the initial defense against infections. However, their excessive presence and activity can lead to prolonged inflammation and tissue damage. Our data demonstrated a significant increase in neutrophils in DFUs samples, which is consistent with their known role in chronic non-healing wounds.26,100 NETs have been implicated in this process, as they can trap and kill pathogens but also damage host tissues and delay healing.26 The identified NETRGs, such as S100A12 and HPSE, further support the critical role of neutrophils in DFUs pathology. Activated B cells, which are crucial for adaptive immunity and antibody production, were found to be significantly decreased in DFUs samples. In diabetic individuals, an imbalance in B cell subsets was detected. As Hammad et al stated, the amounts of specific B cells were found to be lower in diabetic foot patients with infection compared to those who had only diabetes.101 Studies have shown that B cells play a key role in the early stages of the wound healing process.102 This reduction may contribute to impaired immune responses and increased susceptibility to infections in DFUs patients. The negative correlation between activated B cells and the expression of S100A12 and HPSE suggests a complex interplay between different immune cell types and their regulatory mechanisms in DFUs. The alterations in these immune cells highlight the importance of the immune microenvironment in DFUs progression and healing. Understanding these changes provides valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets. For instance, modulating Th17 cell activity or neutrophil function could help reduce chronic inflammation and promote wound healing. Additionally, enhancing B cell activation might improve immune responses and infection control in DFUs patients. B cells promote wound healing by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines and producing specific antibodies that help regulate the immune response and balance inflammation levels. These findings underscore the need for targeted immunotherapies to improve outcomes for individuals suffering from DFUs.

In the context of diabetic wound healing, NETs may exert a dual function. On one hand, NETs can trap and kill pathogens to aid in the control of infection; on the other hand, excessive formation of NETs and insufficient clearance may lead to the persistence and exacerbation of inflammatory responses, thereby impeding wound healing.103,104 Consequently, investigating the role of NETs in diabetic wounds is instrumental in gaining a deeper understanding of the complex mechanisms underlying diabetic wound healing, which in turn can inform the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Monitoring the levels of NETs biomarkers (such as S100A12 and HPSE) can allow for the adjustment of clinical treatment regimens to optimize efficacy and reduce complications. This study predicted 22 drugs of S100A12 and HPSE, among which the lnteraction scores of Ubrogepant and Atogepant were relatively high. Ubrogepant is a new type of oral drug and an antagonist of the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor.105 It reduces the release of inflammatory factors by blocking the CGRP receptor.105 Atogepant is a highly effective oral small molecule CGRP receptor antagonist that can prevent CGRP-mediated injury sensation and neurogenic inflammation.106 CGRP has a pro-inflammatory effect in the accumulation of neutrophils, which are among the first cells to reach the site of inflammation.107 Therefore Ubrogepant and Atogepant may help to reduce the inflammatory response during wound healing in patients with DFUs, thus promoting wound healing.

The findings of HPSE and S100A12 in this study are consistent with existing research contexts. In this study, we highlight that biomarkers (HPSE and S100A12) may play an important role in inflammation, immune response, and wound healing, which are central to the pathophysiology of DFUs. Previous studies have found that biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-18 and CRP play a key role in the chronic inflammatory process of DFUs.108–110 We found that HPSE and S100A12 also fit into this background, because in this study we found a significant positive correlation between these biomarkers and neutrophils, which have been shown to play a key role in inflammatory processes and immune responses. This is closely related to the pathophysiology of DFUs.24–26 Compared with traditional inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6), HPSE and S100A12 may have higher diagnostic efficacy and specificity. The AUC value of CRP in diagnosing grade 2 DFUs was 0.893,111 while in this study, the AUC values of HPSE and S100A12 in diagnosing DFUs were as high as 0.933 and 0.923, respectively. Furthermore, CRP and IL-6 are mainly involved in systemic inflammatory responses. Although they also play important roles in DFUs, their mechanisms of action are rather extensive. The increase of CRP or IL-6 usually indicates the presence of systemic inflammation, but it cannot directly reflect the local pathological mechanism of DFUs.110,112 This study found that HPSE and S100A12 are related to pathways such as IL-17 signaling pathway and linoleic acid metabolism, and these pathways are closely related to inflammation development and wound healing,90–93 which provides a new direction for exploring the pathological mechanism of DFUs.

Our study contributes to further understanding of the inflammatory microenvironment of DFUs. Although studies have revealed a variety of inflammatory markers associated with DFUs, we found that the potential role of HPSE and S100A12 in DFUs has not been widely explored. In particular, the high expression of HPSE and S100A12 in DFUs in relation to chronic inflammatory states may provide new directions for early screening and personalized treatment. Therefore, adding these two markers provides new directions for better management of DFUs.

Limitations

Despite the promising findings, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration. In this study, although biomarkers S100A12 and HPSE were selected to construct a diagnostic model for DFUs, the combination of biomarkers in the model may not be the most optimal. And the condition of DFUs may be affected by multiple factors, such as comorbidities, treatment history, however, these factors have not been incorporated into the diagnostic model. We hope to try to introduce more relevant indicators and include more clinical information in subsequent studies, to make the model closer to clinical practice and improve its practicability in real medical environments. Three machine learning methods were employed for biomarker screening, while each approach has its own advantages, it is undeniable that they also have their own limitations. As a linear model, LASSO has a limited ability to capture complex nonlinearities or non-additive relationships.42 SVM-RF algorithm is greatly influenced by parameters.113 Boruta algorithm is sensitive to the selection of significance level, and different thresholds may lead to different feature selection results.114 Then, the sample size used in this study is relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the use of multiple datasets could introduce batch effects, despite efforts to remove them, potentially affecting the robustness of the findings. Different datasets may have differences in sample characteristics, measurement methods, data quality, etc., which may lead to inherent heterogeneity in the merging datasets. Due to the inherent differences in the characteristics of data from different sources, there may still be residual variability that cannot be completely eliminated. This study only explored the expression levels of biomarkers in DFUs through preliminary experiments, and did not investigate the potential impact of treatment on the expression of NETRGs. The study lacks clinical validation, which is essential for confirming the diagnostic utility of the identified biomarkers in a real-world setting. Although targeted drugs for S100A12 and HPSE have been predicted, they still need to be validated through a large number of clinical trials. In order to address these constraints, our future research will involve a more extensive experimental validation. We will collect tissue samples of DFUs patients before and after treatment, dynamically monitor the expression changes of NETRGs, and analyze the correlation between expression changes of NETRGs and treatment effects (such as ulcer healing time, healing quality, recurrence rate). In addition, in future research, we will focus on verifying the biological functions of HPSE and S100A12 in the wound healing of DFUs. A diabetic mouse model is planned to be constructed and induce skin wounds or ulcers, then explore the impact of the expression levels of biomarkers on the development of DFUs. The wound healing of mouse was observed by knocking out or overexpressing the biomarkers in the mouse model of DFUs.

Conclusion

In summary, this study successfully identified 69 NETRGs associated with DFUs and utilized advanced bioinformatics and machine learning techniques to screen out 2 biomarkers: S100A12 and HPSE. Based on biomarkers, a nomogram model was constructed, and the AUC value of the ROC curve was 0.962. The qRT-PCR experiment indicated that compared with the HC groups, S100A12 and HPSE were significantly highly expressed in the DFUs groups. We will continue to monitor the roles of these genes, as these findings lay the groundwork for future research and potential clinical applications, although further validation and larger-scale studies are required to fully realize their diagnostic and therapeutic potential.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Key Clinical Specialties Cultivated by the Army.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets (GSE134431, GSE68183, and GSE80178) analyzed in this study were extracted from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Chenggong Hospital affiliated to Xiamen University (73JYY2024145244). Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Luo R, Ji Y, Liu YH, Sun H, Tang S, Li X. Relationships among social support, coping style, self-stigma, and quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: a multicentre, cross-sectional study. Int Wound J. 2023;20(3):716–724. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binh MNT, Ddt M, Lan ANT, et al. Risk factors related to diabetic retinopathy in Vietnamese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. 2023;13:100145. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Wu P, Zhu Y, et al. Electrospinning strategies targeting fibroblast for wound healing of diabetic foot ulcers. APL Bioeng. 2025;9(1):011501. doi: 10.1063/5.0235412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raja JM, Maturana MA, Kayali S, Khouzam A, Efeovbokhan N. Diabetic foot ulcer: a comprehensive review of pathophysiology and management modalities. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(8):1684–1693. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2367–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1615439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Raeei MJE, Science M. Harnessing nanoscale innovations for enhanced healing of diabetic foot ulcers. 2024;100210. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damineni U, Divity S, Gundapaneni SRC, Burri RG, Vadde T. Clinical outcomes of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. Cureus. 2025;17(2):e78655. doi: 10.7759/cureus.78655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin YF, Liang J, Wang WS, Hsu BR, Huang TT. The role of foot self-care behavior on developing foot ulcers in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy: a prospective study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(12):1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyamu PN, Otieno CF, Amayo EO, McLigeyo SO. Risk factors and prevalence of diabetic foot ulcers at kenyatta national hospital, nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(1):36–43. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i1.8664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh JW, Hoffstad OJ, Sullivan MO, Margolis DJ. Association of diabetic foot ulcer and death in a population-based cohort from the United Kingdom. Diabet Med. 2016;33(11):1493–1498. doi: 10.1111/dme.13054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng S, Wang H, Pan X, et al. Dendritic hydrogels with robust inherent antibacterial properties for promoting bacteria-infected wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(9):11144–11155. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c25014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411(1):153–165. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackay K, Thompson R, Parker M, et al. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers - A literature review. J Diabet Complicat. 2025;39(3):108973. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2025.108973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi X, Xiang Y, Li Y, et al. An ATP-activated spatiotemporally controlled hydrogel prodrug system for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria-infected pressure ulcers. Bioact Mater. 2025;45:301–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi X, Shi Y, Zhang C, et al. A hybrid hydrogel with intrinsic immunomodulatory functionality for treating multidrug-resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa infected diabetic foot ulcers. ACS Mater Lett. 2024;6(7):2533–2547. doi: 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.4c00392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miranda MB, Alves RF, da Rocha RB, Cardoso VS, da Rocha RB. Effects and parameterization of low-level laser therapy in diabetic ulcers: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-umbrella. Lasers Med Sci. 2025;40(1):109. doi: 10.1007/s10103-025-04366-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Shao T, Wang J, et al. An update on potential biomarkers for diagnosing diabetic foot ulcer at early stage. Biomed Pharmacothe. 2021;133:110991. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korkmaz P, Koçak H, Onbaşı K, et al. The role of serum procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and fibrinogen levels in differential diagnosis of diabetic foot ulcer infection. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:7104352. doi: 10.1155/2018/7104352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng L, Xiang W, Xiao W, Wu Y, Sun L. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. MedComm. 2025;6(3):e70101. doi: 10.1002/mco2.70101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Dou Y, Lu C, Han R, He Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps in tumor metabolism and microenvironment. Biomarker Res. 2025;13(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s40364-025-00731-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sennett C, Pula G. Trapped in the NETs: multiple roles of platelets in the vascular complications associated with neutrophil extracellular traps. Cells. 2025;14(5):335. doi: 10.3390/cells14050335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Peng D, Sun W. Dual roles of neutrophil extracellular traps in lung cancer: mechanism exploration and therapeutic prospects. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi = Chinese Journal of Lung Cancer. 2025;28(1):63–68. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2025.101.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Li C, Fu C, et al. Innovative nanoparticle-based approaches for modulating neutrophil extracellular traps in diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutics. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12951-025-03195-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang S, Wang S, Chen L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps delay diabetic wound healing by inducing endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via the hippo pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(1):347–361. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.78046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rui S, Dai L, Zhang X, et al. Exosomal miRNA-26b-5p from PRP suppresses NETs by targeting MMP-8 to promote diabetic wound healing. J Control Release. 2024;372:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong SL, Demers M, Martinod K, et al. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):815–819. doi: 10.1038/nm.3887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang S, Hu L, Han R, Neuropeptides YY. Inflammation, biofilms, and diabetic foot ulcers. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022;130(7):439–446. doi: 10.1055/a-1493-0458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harithpriya K, Kaussikaa S, Kavyashree S, Geetha A, Ramkumar KM. Pathological insights into cell death pathways in diabetic wound healing. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;264:155715. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2024.155715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong J, Kukula AK, Toyoshima M, Nakajima M. Genomic organization and chromosome localization of the newly identified human heparanase gene. Gene. 2000;253(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00251-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Mestre AM, Khachigian LM, Santiago FS, Staykova MA, Hulett MD. Regulation of inducible heparanase gene transcription in activated T cells by early growth response 1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(50):50377–50385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310154200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moroz OV, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Lukanidin E, Bronstein IB. Multiple structural states of S100A12: a key to its functional diversity. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60(6):581–592. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng ZH, Li WC, Li ZC, Wang YX, Han ZW, Zhang YP. Neutrophil extracellular traps-associated modification patterns depict the tumor microenvironment, precision immunotherapy, and prognosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1094248. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1094248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Li E, Chang Z, et al. Identifying potential therapeutic targets in lung adenocarcinoma: a multi-omics approach integrating bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing with Mendelian randomization. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1433147. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1433147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito K, Murphy D. Application of ggplot2 to pharmacometric graphics. CPT. 2013;2(10):e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan SM, Chen X, Qu YQ, Zhang MY. C6 and KLRG2 are pyroptosis subtype-related prognostic biomarkers and correlated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-75650-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Meltzer P, Davis S. RCircos: an R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigden DJ, Fernández XM. The 2021 nucleic acids research database issue and the online molecular biology database collection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1–d9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2(3):100141. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu S, Hu E, Cai Y, et al. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nat Protocols. 2024;19(11):3292–3320. doi: 10.1038/s41596-024-01020-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, Shi W, Zhao D, Xiao S, Wang K, Wang J. Identification of immune-associated genes in diagnosing aortic valve calcification with metabolic syndrome by integrated bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front Immunol. 2022;13:937886. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.937886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohanyan H, Portengen L, Kaplani O, et al. Associations between the urban exposome and type 2 diabetes: results from penalised regression by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator and random forest models. Environ. Int. 2022;170:107592. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uddin S, Khan A, Hossain ME, Moni MA. Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction. BMC Med Inf Decis Making. 2019;19(1):281. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-1004-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun T, Liu J, Yuan H, Li X, Yan H. Construction of a risk prediction model for lung infection after chemotherapy in lung cancer patients based on the machine learning algorithm. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1403392. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1403392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Li CL, Wu L, et al. Distinct molecular subtypes of systemic sclerosis and gene signature with diagnostic capability. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1257802. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1257802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Lu F, Yin Y. Applying logistic LASSO regression for the diagnosis of atypical Crohn’s disease. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):11340. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15609-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engebretsen S, Bohlin J. Statistical predictions with glmnet. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0730-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi H, Yuan X, Liu G, Fan W. Identifying and validating GSTM5 as an immunogenic gene in diabetic foot ulcer using bioinformatics and machine learning. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:6241–6256. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S442388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu L, Qiao Z, Xu M, et al. Establishment and validation of a 3-month prediction model for poor functional outcomes in patients with acute cardiogenic cerebral embolism related to non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1392568. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1392568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernal YA, Blanco A, Oróstica K, Delgado I, Armisén R. Integration of RNA editing with multiomics data improves machine learning models for predicting drug responses in breast cancer patients. Res Square. 2024. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-5604105/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanz H, Valim C, Vegas E, Oller JM, Reverter F. SVM-RFE: selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinf. 2018;19(1):432. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2451-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maurya NS, Kushwah S, Mani A, Mani A, Mani A. Prognostic model development for classification of colorectal adenocarcinoma by using machine learning model based on feature selection technique boruta. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6413. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-33327-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kong C, Zhu Y, Xie X, Wu J, Qian M. Six potential biomarkers in septic shock: a deep bioinformatics and prospective observational study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1184700. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1184700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li M, Wei X, Zhang SS, et al. Recognition of refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia among Myocoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in hospitalized children: development and validation of a predictive nomogram model. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):383. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02684-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nameghi SMJE, Science M. Association of GIPR gene variant on the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. 2023;13:100140. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM, Selvin E, Etiology HCW. Epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(1):209–221. doi: 10.2337/dci22-0043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu Y, Wang H, Liu Y. NETosis: sculpting tumor metastasis and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2024;321(1):263–279. doi: 10.1111/imr.13277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, Zhou X, Yin Y, Mai Y, Wang D, Zhang X. Hyperglycemia induces neutrophil extracellular traps formation through an NADPH oxidase-dependent pathway in diabetic retinopathy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:3076. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu Y, Xia X, He Q, et al. Diabetes-associated neutrophil NETosis: pathogenesis and interventional target of diabetic complications. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1202463. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1202463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lou X, Chen H, Chen S, et al. LL37/FPR2 regulates neutrophil mPTP promoting the development of neutrophil extracellular traps in diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J. 2024;38(11):e23697. doi: 10.1096/fj.202400656R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang X, Ma Y, Chen X, Zhu J, Xue W, Ning K. Mechanisms of neutrophil extracellular trap in chronic inflammation of endothelium in atherosclerosis. Life Sci. 2023;328:121867. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel M, Patel V, Shah U, Patel A. Molecular pathology and therapeutics of the diabetic foot ulcer; comprehensive reviews. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2023;1–8. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2023.2219863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Q, Zhu G, Cao X, Dong J, Song F, Niu Y. Blocking AGE-RAGE signaling improved functional disorders of macrophages in diabetic wound. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:1428537. doi: 10.1155/2017/1428537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Youjun D, Huang Y, Lai Y, et al. Mechanisms of resveratrol against diabetic wound by network pharmacology and experimental validation. Ann Med. 2023;55(2):2280811. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2023.2280811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vlodavsky I, Ilan N, Sanderson RD. Forty years of basic and translational heparanase research. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1221:3–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang F, Wang Y, Zhang D, Puthanveetil P, Johnson JD, Rodrigues B. Fatty acid-induced nuclear translocation of heparanase uncouples glucose metabolism in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(2):406–414. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vlodavsky I, Eldor A, Haimovitz-Friedman A, et al. Expression of heparanase by platelets and circulating cells of the immune system: possible involvement in diapedesis and extravasation. Invasion Metastasis. 1992;12(2):112–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parish CR. The role of heparan sulphate in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(9):633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weber KS, von Hundelshausen P, Clark-Lewis I, Weber PC, Weber C. Differential immobilization and hierarchical involvement of chemokines in monocyte arrest and transmigration on inflamed endothelium in shear flow. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(2):700–712. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Levidiotis V, Freeman C, Tikellis C, Cooper ME, Power DA. Heparanase is involved in the pathogenesis of proteinuria as a result of glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(1):68–78. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000103229.25389.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Han J, Mandal AK, Hiebert LM. Endothelial cell injury by high glucose and heparanase is prevented by insulin, heparin and basic fibroblast growth factor. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2005;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-4-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van den Hoven MJ, Rops AL, Vlodavsky I, et al. Heparanase in glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2007;72(5):543–548. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rao G, Ding HG, Huang W, et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate high glucose-induced heparanase-1 production and heparan sulphate proteoglycan degradation in human and rat endothelial cells: a potential role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Diabetologia. 2011;54(6):1527–1538. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2110-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma P, Luo Y, Zhu X, Ma H, Hu J, Tang S. Phosphomannopentaose sulfate (PI-88) inhibits retinal leukostasis in diabetic rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380(2):402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maxhimer JB, Somenek M, Rao G, et al. Heparanase-1 gene expression and regulation by high glucose in renal epithelial cells: a potential role in the pathogenesis of proteinuria in diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2005;54(7):2172–2178. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sreejit G, Flynn MC, Patil M, Krishnamurthy P, Murphy AJ, Nagareddy PR. S100 family proteins in inflammation and beyond. Adv Clin Chem. 2020;98:173–231. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hofmann MA, Drury S, Fu C, et al. RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: a central cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell. 1999;97(7):889–901. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80801-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oesterle A, Bowman MA. S100A12 and the S100/calgranulins: emerging biomarkers for atherosclerosis and possibly therapeutic targets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(12):2496–2507. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.302072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kosaki A, Hasegawa T, Kimura T, et al. Increased plasma S100A12 (EN-RAGE) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(11):5423–5428. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kislinger T, Tanji N, Wendt T, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products mediates inflammation and enhanced expression of tissue factor in vasculature of diabetic apolipoprotein E-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(6):905–910. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.21.6.905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Zieske A, et al. Morphologic findings of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in diabetics: a postmortem study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(7):1266–1271. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000131783.74034.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Katsuki A, Sumida Y, Murashima S, et al. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha are increased in obese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(3):859–862. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jokl R, Laimins M, Klein RL, Lyons TJ, Lopes-Virella MF, Colwell JA. Platelet plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in patients with type II diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(8):818–823. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.8.818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang Z, Tao T, Raftery MJ, Youssef P, Di Girolamo N, Geczy CL. Proinflammatory properties of the human S100 protein S100A12. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69(6):986–994. doi: 10.1189/jlb.69.6.986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hasegawa T, Kosaki A, Kimura T, et al. The regulation of EN-RAGE (S100A12) gene expression in human THP-1 macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2003;171(2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang J, Ding X. IL-17 signaling in skin repair: safeguarding metabolic adaptation of wound epithelial cells. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2022;7(1):359. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01202-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mu X, Gu R, Tang M, Wu X, He W, Nie X. IL-17 in wound repair: bridging acute and chronic responses. Cell commun Signaling. 2024;22(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01668-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Poljšak N, Kreft S, Glavač N K. Vegetable butters and oils in skin wound healing: scientific evidence for new opportunities in dermatology. Phytother Res. 2020;34(2):254–269. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rodrigues HG, Vinolo MA, Sato FT, et al. Oral administration of linoleic acid induces new vessel formation and improves skin wound healing in diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Park NY, Valacchi G, Lim Y. Effect of dietary conjugated linoleic acid supplementation on early inflammatory responses during cutaneous wound healing. Mediators Inflammation. 2010;2010:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2010/342328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bai H, Kyu-Cheol N, Wang Z, et al. Regulation of inflammatory microenvironment using a self-healing hydrogel loaded with BM-MSCs for advanced wound healing in rat diabetic foot ulcers. J Tissue Eng. 2020;11:2041731420947242. doi: 10.1177/2041731420947242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kumar NP, Sridhar R, Nair D, Banurekha NTB, Babu S, Babu S. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with altered CD 8 + T and natural killer cell function in pulmonary tuberculosi. Immunology. 2015;144(4):677–686. doi: 10.1111/imm.12421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abdel-Moneim A, Bakery HH, Allam G. The potential pathogenic role of IL-17/Th17 cells in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;101:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang X, Mathis BJ, Huang Y, Li W, Shi Y. KLF4 promotes diabetic chronic wound healing by suppressing Th17 cell differentiation in an MDSC-dependent manner. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021:7945117. doi: 10.1155/2021/7945117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Audu CO, Wolf SJ, Joshi AD, et al. Histone demethylase JARID1C/KDM5C regulates Th17 cells by increasing IL-6 expression in diabetic plasmacytoid dendritic cells. JCI Insight. 2024;9(12). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.172959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Phillipson M, Kubes P. The healing power of neutrophils. Trends Immunol. 2019;40(7):635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hammad RH, El-Madbouly AA, Kotb HG, Zarad MS. Frequency of circulating B1a and B2 B-cell subsets in egyptian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Egyptian J Immunol. 2018;25(1):71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Iwata Y, Yoshizaki A, Komura K, et al. CD19, a response regulator of B lymphocytes, regulates wound healing through hyaluronan-induced TLR4 signaling. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(2):649–660. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhu S, Yu Y, Ren Y, et al. The emerging roles of neutrophil extracellular traps in wound healing. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(11):984. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04294-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang S, Feng Y, Chen L, et al. Disulfiram accelerates diabetic foot ulcer healing by blocking NET formation via suppressing the NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD pathway. Transl Res. 2023;254:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2022.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dighriri IM, Nazel S, Alharthi AM, et al. A comprehensive review of the mechanism, efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ubrogepant in the treatment of migraine. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48160. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Boinpally R, Shebley M, Trugman JM. Atogepant: mechanism of action, clinical and translational science. Clin Transl Sci. 2024;17(1):e13707. doi: 10.1111/cts.13707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zarban AA, Chaudhry H, de Sousa Valente J, Argunhan F, Ghanim H, Brain SD. elucidating the ability of CGRP to modulate microvascular events in mouse skin. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20):12246. doi: 10.3390/ijms232012246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weigelt C, Rose B, Poschen U, et al. Immune mediators in patients with acute diabetic foot syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1491–1496. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jeandrot A, Richard JL, Combescure C, et al. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein concentrations to distinguish mildly infected from non-infected diabetic foot ulcers: a pilot study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(2):347–352. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0840-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tecilazich F, Dinh T, Pradhan-Nabzdyk L, et al. Role of endothelial progenitor cells and inflammatory cytokines in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sharma H, Sharma S, Krishnan A, et al. The efficacy of inflammatory markers in diagnosing infected diabetic foot ulcers and diabetic foot osteomyelitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0267412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rose-John S. Local and systemic effects of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in inflammation and cancer. FEBS Lett. 2022;596(5):557–566. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang J, Li N, Lin W, et al. Machine learning for predicting hyperglycemic cases induced by PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors. J Healthcare Eng. 2022;2022(1):6278854. doi: 10.1155/2022/6278854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kursa MB, WRJJoss R. Feature selection with the boruta package. 2010;36:1–13. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets (GSE134431, GSE68183, and GSE80178) analyzed in this study were extracted from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).