Abstract

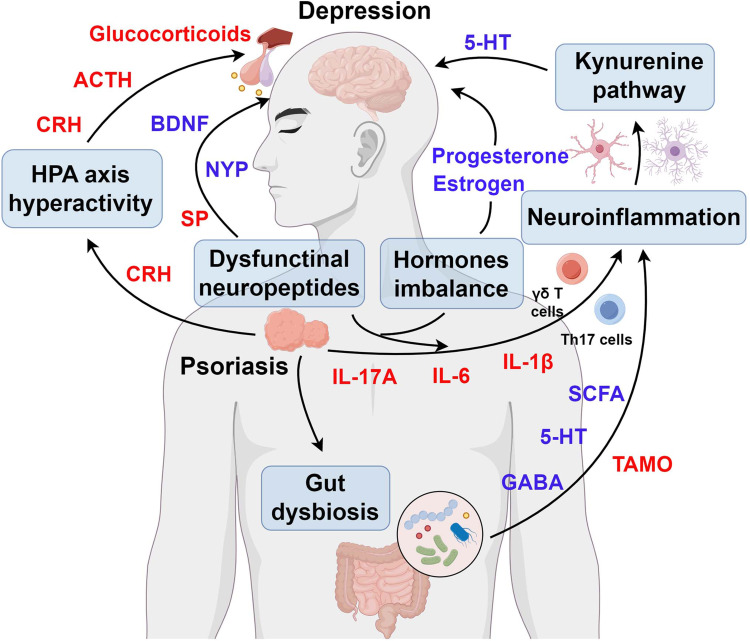

Psoriasis, a common chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting approximately 2–3% of the global population, frequently co-occurs with depression. This highly prevalent comorbidity significantly impairs patients’ quality of life. Despite the substantial physical and mental health burden imposed by psoriatic depression, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms connecting psoriasis and depression remain poorly understood. In this review, we explored several pathological processes that may contribute to psoriasis-associated depression, including immune cells dysregulations, hormones imbalances, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunctions, neuropeptides expression abnormalities, and gut dysbiosis. The primary purpose of this review was to present a comprehensive overview of the pathogenic mechanisms linking psoriasis and depression. These insights may guide trans-disciplinary interventions aimed at both skin and mood symptoms.

Keywords: psoriasis, depression, Th17 cell, HPA axis, neuropeptides, gut microbiota

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects more than 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Red patches with thick, silvery scales and sustained inflammation are the major skin hallmarks of psoriasis.1,2 However, psoriasis is not only solely limited to cutaneous manifestations but is also frequently associated with a broad spectrum of comorbidities,3,4 including mental disorders (eg depression and anxiety),5,6 metabolic disturbances (eg diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia),7,8 cardiovascular abnormalities (eg atherosclerosis and hypertension),9,10 psoriatic arthritis,11,12 chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),13,14 and other systemic complications. These findings underscore the importance of a comprehensive approach to both the dermatological and associated systemic manifestations of psoriasis.

Depression is one of the most common and serious comorbidities associated with psoriasis. Psoriatic patients, who experience multiple psychological burden (such as appearance anxiety, burdensome treatment regimens, social barriers, and economic burden), often suffer from depressive symptoms.15–17 Furthermore, a significant proportion of individuals experiencing psoriasis-related depression exhibit suicidal tendencies and engage in self-harming behaviors.18,19 In recent years, the high psycho-social burdens in psoriatic patients with depression have garnered increasing attention. The theme of World Psoriasis Day 2022 “United we tackle mental health” highlights the growing recognition of the detrimental effects of depression in patients with psoriasis. Greater awareness of the harmful effects of depression on psoriasis would improve patients’ quality of life and optimize their clinical treatment outcomes.

Psoriasis and depression share underlying pathophysiological features, such as inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and immune dysregulation. Therefore, further studies are warranted to investigate the biological mechanisms by which psoriasis contributes to the development of depression. Additionally, existing reviews in this field may have severe limitation (eg, fragmented understanding of cellular mechanisms, limited therapeutic integration). In this review, we elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms underlying psoriasis-related depression, encompassing inflammatory dysregulation, hormonal imbalances, neuroendocrine pathways, neuropeptide alterations, and microbiome interactions. Furthermore, we will explore the future research directions and address the challenges in the search for novel treatment strategies for both psoriasis and depression.

The Pathogenesis of Psoriasis

The cellular mechanisms that underlie psoriasis are intricate. Numerous cells, including dendritic cells, T cells, keratinocytes, neutrophils, are implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.20 Once stimulated with psoriasis-specific autoantigens, such as cathelicidin LL37,21 the plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) activate and release a series of cytokines like interleukin-23 (IL-23) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), thereby triggering the helper T (Th) cells differentiation into pro-inflammatory Th17.22,23 Furthermore, γδ T17 cells in the dermis can also be activated by IL-23.24 These activated Th17 cells and γδ T cells subsequently release interleukin-17A (IL-17A), interleukin-17F (IL-17F) and interleukin-22 (IL-22), ultimately leading to the hyper-proliferation and abnormal differentiation of keratinocytes.25,26 In turn, these dysfunctional keratinocytes can further release LL-37, thereby forming a self-perpetuating inflammatory loop.27 In addition, activated keratinocytes secrete chemokines that recruit neutrophils and macrophages, which result in amplifying the inflammatory responses in psoriasis.28–30 Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that mast cells also participate in the etiology of psoriasis. On one hand, mast cells released tryptase and Cathepsin B to induce itch in psoriasis.31 On the other hand, inflammatory mediators (such as IL-17A, TNF-α) secreted from mast cells further trigger DC maturation, T cells clonal expansion and neurons activation, ultimately potentiating the psoriasis-related inflammation.32–34

The Pathogenic Mechanisms Underlying Psoriasis-Related Depression

Immune Cells and Their Cytokines in Psoriasis and Depression

Given that Th17 cells/γδ T cells and IL-17A are the predominant culprits of psoriasis pathogenesis, they may also play a crucial role in the etiology of psoriasis-associated depression (Figure 1). Previous study suggested that Th17 cells/γδ T cells can transmigrate into the brain through impaired blood-brain barrier (BBB).35 Besides the peripheral-derived γδ T cells, the meningeal-resident γδ T cells can also amplify the neuroimmune response and consequently induce depression-like behaviors through Dectin-1 signaling.36 Furthermore, IL-17A, a key cytokine secreted by Th17 cells/γδ T cells, exacerbates neuro-inflammation by directly crossing the damaged BBB. IL-17A contributes to BBB disruption through multiple pathways. First, it binds to IL-17 receptors on BBB endothelial cells, disrupting tight junctions and increasing BBB permeability.37 Second, IL-17A recruits neutrophils to the BBB by inducing CXCL1 secretion. These neutrophils subsequently damage the BBB through gelatinase and proteases release.38 Additionally, IL-17A activates matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3), which promotes neutrophil recruitment and further BBB damage.39 Other keratinocyte-derived cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, can cross the BBB. These cytokines amplify brain inflammation via soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R), IL-1R and Toll like receptors (TLRs), respectively.40–42 Aligning with the above pathological alterations, current research indicates that psoriasis-related psychological stresses (such as appearance anxiety, self-abasement) exactly promote the onset of depression through Th17 cell-mediated inflammatory responses and the aforementioned inflammatory factors.5,43,44

Figure 1.

Th17 cells / γδ T cells and cytokines as a bridge among psoriasis and depression. By Figdraw.

Abbreviations: IL-17A, interleukin-17A; CXCL-1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinase; IL-17R, interleukin-17 receptor; IL-10, interleukin-10; IL-6, interleukin-6; sIL-6R, soluble IL6 receptor; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-1R, interleukin-1 receptor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; TLRs, Toll-like receptors.

These transmigrated Th17 cells/γδ T cells and cytokines (including IL-17A, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) may contribute to neuroinflammation through various mechanisms (Figure 1). For instance, Th17 cells can exacerbate depressive symptoms by targeting brain-resident cells, such as neurons and microglia.45,46 Volker Siffrin et al demonstrated that Th17 cells induce neuronal damage by directly elevating intracellular calcium concentration in neuron, subsequently triggering Ca2+-mediated neuronal toxicity.47 In addition, Th17 cells-activated microglia secrets indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) and consequently results in the decline of tryptophan by activating the kynurenine pathway.48,49 Moreover, the decreased level of tryptophan finally leads to the etiology of depression.50,51 Furthermore, infiltrated cytokines, including IL-17A, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, also exacerbate the neuroinflammatory processes.52–55 In a study involving 232 participants, Hirohito Tsuboi et al reported that the serum levels of IL-17A and TNF-α are significantly positively correlated with the severity of depressive symptoms.53 Hongyu Wang et al showed the interaction between IL-17A and Src family kinases, followed by activation of phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), causes intracellular Ca2+ flux, ultimately resulting in caspase-12-mediated neuronal apoptosis.56 In another study, Xue-Jing Lv et al unraveled that IL-17A markedly activates astrocytes in the ventral hippocampus (vHPC) CA1 area by increasing intracellular calcium level. These IL-17A-activated astrocytes release ATP/adenosine, which subsequently contributes to depression symptoms.57 Additionally, IL-17A promotes M1 microglial polarization by activating GSK-3β signaling, thereby intensifying neuroinflammation in the brain.58 Furthermore, TNF-α induces glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, thereby promoting neuroinflammatory responses.52,59 In addition, both IL-1β and IL-6 are known to activate the kynurenine pathway. This activation results in reduced tryptophan production, which ultimately enhances depression-related symptoms.60,61

Taken together, these findings may demonstrate that inflammatory dysregulation, particularly Th17 cells/γδ T cells and associated cytokines, may serve as key mediators linking psoriasis and depression.

Female Hormonal Factors in Psoriasis and Depression

Female hormonal factors, such as estrogen, progesterone and prolactin, are critical factors that regulate various physiological processes. In addition to being essential for female reproductive physiological processes, female hormones are also known to be important regulatory factors for autoimmune diseases (such as psoriasis) and depression (Figure 2).62–64

Figure 2.

Hormones imbalance in psoriasis and depression. By Figdraw. The dashed line represents the inability to exert the regulatory effect. The solid line represents the ability to play a moderating role. The red characters mean an increased expression of specific hormones. Additionally, the blue characters indicate a decreased expression of specific hormones.

Abbreviations: BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor; DCs, dendritic cells; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Estrogen, the principal female sex hormone, plays a vital role in regulating immune responses.65 Estrogen can suppress the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ) via interacting with the estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) on dendritic cells, T cells, and macrophages.65,66 Additionally, estrogen enhances IL-10 (an anti-inflammatory cytokines) releases and therefore mitigates the inflammatory responses in autoimmune diseases.67 Moreover, estrogen can promote Treg cells differentiation and thereby maintain immune tolerance and prevent autoimmunity.68 Given the above anti-inflammatory properties of estrogen, estrogen exerts an inhibitory effect on the psoriatic dermatitis. Clinical evidence also confirms that the severity of psoriasis is increased when the serum estrogen levels are low (eg, during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle or postmenopause).69 Moreover, clinical data further show that women experiencing low estrogen during the luteal phase or postmenopause exhibit more negative mood and reduced hippocampal activation under acute stress and are particularly sensitive to lower cortisol levels during repeated stress.70 Mechanistically, estrogen eases the depression by suppressing the inflammatory cytokines releases.71 In addition, estrogen was further identified as critical for increasing hippocampal dendritic Vglut1-positive presynaptic clusters.72 Rodent studies further revealed that estrogen alters neuronal excitability in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (associated with increased susceptibility) and induces a decrease in the resting membrane potential (RMP) of lateral habenula (LHb) neurons.73,74

Progesterone, another key female hormone, also plays an anti-inflammatory role by inhibiting the T cell (particularly CD4+ T cells) proliferation, dampening pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α) releases and inhibiting inflammasome activation.75–77 Progesterone’s immunosuppressive properties likely account for the symptom fluctuations in many women with psoriasis experience during their menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Rising progesterone levels in the luteal phase may reduce psoriatic inflammation, improving symptoms for some.78,79 Similarly, the substantial progesterone increases in the pregnancy fosters an anti-inflammatory state, often leading to significant symptomatic relief.79,80 Progesterone’s immunosuppressive properties also play a critical role in the alleviating depressive symptoms. According to the Swiss Perimenopause Study, elevated progesterone levels were associated with increased psychosocial resilience and reduced depressive symptoms in women.81 In addition, postpartum depression (PPD) is associated with a decline in progesterone and progesterone-derived neurosteroids after delivery.82 Mechanistically, progesterone and its metabolites mitigate the depressive disorder through promotion of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A receptor activity and regulation the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus.83,84

Prolactin, a female hormone primarily associated with lactation, acts as a double-edged sword in psoriasis and depression. While it can exacerbate psoriasis symptoms, it helps alleviate depressive symptoms. In psoriasis, elevated prolactin levels promote the proliferation of keratinocyte and the secretion of IL-17, IL-6 and TNF-α from immune cells, consequently resulting in aggravating the severity of psoriatic plaques.85 In depression, prolactin exerts a suppressive effect on depression. Studies in ovariectomized female rats revealed that prolactin mitigates chronic stress-induced passive coping behaviors and elevates VTA dopamine neuron populations, highlighting its contribution to stress resilience under low-ovarian-hormone conditions.86 Large-scale population cohort studies are still needed to further clarify the role of prolactin in psoriasis and its associated depression.

In combination, recognizing these hormonal interconnections is critical for personalized treatment strategies for women managing both psoriasis and depression in clinical practice.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis in Psoriasis and Depression

The HPA axis represents a complex neuroendocrine communication network involving interactions between the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands. This predominant neuroendocrine system responds to diverse physical and psychological stressors (such as disfigurement, social barriers, and economic burden) by releasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and glucocorticoids (GCs).87 In addition to the HPA axis in the brain, skin is a newly identified cutaneous HPA axis.88 Accumulating evidence suggests that skin-derived CRH and ACTH pathways may serve as a critical mechanistic link between the psoriasis and depression (Figure 3).89,90

Figure 3.

The overactive HPA axis is a crucial link bridging psoriasis and depression. By Figdraw.

Abbreviations: UV, ultraviolet; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; CRHR1, corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; HMGB1, high-mobility group box-1.

CRH is a 41 amino acid peptide that is primarily released into the brain. Elevated levels of CRH have been observed in individuals with depression compared with healthy controls.91 This peptide exerts its effects through interactions with corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor (CRHR) subtypes. Cedomir Todorovic et al demonstrated that overactivation of hippocampal CRHR receptor 1 (CRHR1) by CRH induces depression-like behaviors in mice.92 Subsequent studies by Sun et al and Liu et al highlighted that intraperitoneal administration of antalarmin, a novel identified CRHR1 antagonist, ameliorates LPS-induced or post-stroke- mediated depression in vivo.91,93 Beyond the central nervous system, several peripheral cells in the skin, including mast cells, melanocytes, keratinocytes and fibroblasts, also release CRH under conditions of mental stress or ultraviolet (UV) light exposure.94–96 Consistently, Kim et al reported that CRH is increased in the psoriatic lesions, suggesting its potential role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and associated depression.97 Elevated CRH contributes to the development of psoriasis and psoriasis-associated depression through multiple mechanisms. First, CRH binds to CRHR1 on keratinocytes and mast cells, inducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-22, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β).98,99 These cytokines in turn amplify cutaneous inflammation by propagating downstream immune responses. Second, CRH-induced cytokines can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) via the activation of endothelial cells, thereby influencing neuroinflammatory pathways that contribute to psoriasis-related depression. Third, local HPA axis activation in the skin indirectly potentiates central HPA axis activity, exacerbating depressive behaviors. These interconnected mechanisms underscore the importance of CRH as a key regulator of psoriasis pathology.

ACTH, a 39-amino acid polypeptide, is synthesized and secreted by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Elevated ACTH levels have also been observed in patients with depression, as shown in clinical studies. Recent investigations have demonstrated that high ACTH levels, particularly an elevated ACTH/cortisol ratio, may serve as a predictive biochemical marker of psoriasis severity and its association with psychopathology.100 These findings suggest that ACTH may play a central role in linking psoriasis to depression. ACTH has been implicated in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders and psoriasis via its regulatory effects on diverse cytokine levels. For instance, Abhiraj Rajasekharan et al found that elevated ACTH levels were associated with increased IL-17 production, which ultimately contributes to psoriasis progression.101 Additionally, physical exercise has been shown to improve mental health outcomes, as evidence by reductions in ACTH level and decreased inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-17 and IL-1β).102 Collectively, these cytokines (IL-17 and IL-1β) are critical contributors to the pathogenesis of both depression and psoriasis. This provides a novel perspective on the role of ACTH as a potential mediator of psoriasis and its psychiatric comorbidities.

Previous studies have reported that approximately 35–65% of depressive patients exhibit glucocorticoid hypersecretion.103,104 A growing body of evidence has demonstrated elevated serum glucocorticoid levels in depressed individuals compared to controls.105 Of notable interest, these individuals also show concurrent increase in glucocorticoids and severe neuroinflammation. Excess glucocorticoid release amplifies the neuroinflammatory responses through multiple cellular pathways. Mechanistically, a high concentration of glucocorticoids provokes the secretion of high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) by activated microglia and cortical astrocytes, thereby triggering neuroinflammation.106,107 Furthermore, glucocorticoid-induced upregulation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) expression contributes to neurological pathology in depression.108 Glucocorticoids promote harmful effects by inducing NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. A deficiency in glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback is another hallmark feature of depression syndrome.109,110 Previous investigations have revealed that glucocorticoid receptor (GR) function is impaired in depressed individuals, leading to defective GR-mediated negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis.111,112 This results in continuous HPA axis activation, which might exacerbate neuroinflammatory pathology and sustain depressive symptoms.

In summary, these researches may indicate that overactivation of HPA axis is highly associated with the etiology of psoriasis-related depression. Thus, targeting HPA axis might be a promising therapeutic strategy for psoriasis-associated depression.

Neuropeptides and Neurotransmitters in Psoriasis and Depression

The skin, as the largest sensory organ of the body, is densely innervated by peripheral nerves.113 Functionally, these peripheral nerves can release numerous neuropeptides and neurotransmitters [eg brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Neuropeptide Y (NPY), and Substance P (SP)] to facilitate communication with the cutaneous resident non-neuronal cells, including keratinocytes, DC cell, mast cell, fibroblast, and others.114 Recent studies highlight the potential contributory role of these neuropeptides and neurotransmitters in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and its complication, such as depression (Figure 4).89

Figure 4.

Neuropeptides and neurotransmitters play a vital role in the etiology of psoriasis and depression. By Figdraw. The red characters mean an increased expression of specific neuropeptides and neurotransmitters. Additionally, the blue characters indicate a decreased expression of specific neuropeptides and neurotransmitters.

Abbreviations: DCs, dendritic cells; NPY, Neuropeptide Y; BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor; SP, Substance P; Y2R, Y2 receptor; IDO, indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase.

BDNF, a member of the nerve growth factor family of trophic factors, plays a pivotal role in supporting neuron survivals and maintaining neural plasticity.115 Pathologically, a reduction in BDNF levels in the brain has been identified as one of the major mechanisms underlying depression.116,117 Previous study by Brunoni et al demonstrated reduced plasma BDNF level in psoriatic patients,118 while Sjahrir et al reported a strong negative correlation serum BDNF levels and the severity of depressive symptoms in psoriasis.119 Furthermore, W. JiaWen elucidated that downregulation of BDNF/TrKB signaling pathway is implicated in the pathogenesis of depression-like behavior in the K5.Stat3C psoriatic mouse model.120 Collectively, these results suggest that the BDNF level may function as a promising biomarker for predicting the severity of depression in psoriasis.

NPY, a 36-amino acid peptide, is widely expressed in mammalian peripheral and central nervous systems. Physiologically, it exerts antidepressant effects by binding to its Y2 receptor and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activity.121 Pathologically, reduced plasma and medial prefrontal cortex levels of NPY diminish its antidepressant influence, ultimately contributing to the development of depression.122,123 Emerging evidence suggests a potential role for NPY in psoriasis pathogenesis. Reich et al reported significantly lower plasma NPY level in pruritic compared with non-pruritic psoriatic patients.124 Notably, activation of NPY and its Y1 receptor alleviates von Frey filament-induced mechanical itch and 48/80-triggered histaminergic itch.125 Future investigation is needed to elucidate the pathogenic role of NPY in local psoriasis pathology, particularly in individuals with psoriasis-related depression.

SP, a widely expressed neurotransmitter composed of 11-amino acid, is released upon stress. Recent evidence has shown increased levels of SP in psoriatic skin compared with normal skin.126 This peptite plays a significant role in the pathological progression of psoriasis. Specifically, SP induces the maturation of CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs) by binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), ultimately leading to IL-23 release from mature DCs and exacerbation of psoriasis severity.127 Additionally, SP triggers mast cell activation by binding to NK-1 receptors, resulting in the secretion of histamine and cytokines (such as IFN-γ and TNF-α), which leads to pruritus and neurogenic inflammation in psoriasis.126,128 Furthermore, SP is involved in the recruitment of CD4+/CD8+ T cell infiltration and promotes keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation, thereby contributing to disease progression.129,130 Interestingly, beyond its role in psoriasis, SP also plays a role in the etiology of depression. Elevated levels of SP level have been observed in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with major depressive disorder.131 Several substance P antagonists, such as MK869 and NKP608, have been demonstrated promising therapeutic effects on depression syndrome.132

Collectively, these findings suggest that neuropeptides disturbances may serve as a connecting link between psoriasis and depression. Exogenous administration of BDNF or NYP might be an effective way to treat psoriasis and depression.

Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Psoriasis and Depression

Gut microbiota refers to microorganisms that inhabits the gastrointestinal environment of humans and other animals, including bacteria, fungi, phages, and eukaryotic viruses.133 Multiple researches have demonstrated that gut microbiota plays a critical role in maintaining host immune homeostasis.134,135 Disturbances in the homeostasis of gut microbiota, also known as gut dysbiosis, have been demonstrated to be involved in a wide range of diseases, including autoimmune disorders,136,137 digestive system cancer,138,139 and neurological conditions.140,141 In addition to the microbiota itself, shifts in the microbial metabolites small molecules directly produced by bacteria or derived from host molecules modified by bacterial activity are increasingly recognized as contributing factors in the development of various diseases.136,142,143 Recent studies may indicate that gut dysbiosis and its associated changes in the microbial metabolome precede the onset of psoriasis and depression (Figure 5). 144,145

Figure 5.

The gut dysbiosis is a pivotal bridge linking psoriasis and depression. By Figdraw. The red characters mean an increased expression of specific gut microbiota and its metabolites. Additionally, the green characters indicate a decreased expression of specific gut microbiota and its metabolites. Gut microbiota is shown in italics.

Abbreviations: LCFA, long-chain fatty acids; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; GABA, gamma amino butyric acid; 5-HT, serotonin; DCs, dendritic cells; TMAO, Trimethylamine-N-oxide.

A growing body of research indicates that the composition of specific bacterial taxa is quite distinct between healthy controls and psoriatic patients.146 C. Hidalgo-Cantabrana et al demonstrated that the α-diversity of gut microbiota was reduced in psoriatic patients compared to healthy controls.147 Furthermore, Jonathan Shapiro et al revealed that the β-diversity of gut microbiota also exhibited a distinct pattern in individuals with psoriasis.148 Through the use of metagenomics sequencing, Shiju Xiao et al identified that the abundance of phyla Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia and Actinobacteria as well as genera such as Megamonas, Roseburia, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Bacteroides, increased in psoriatic patients, while the abundance of Euryarchaeota, Proteobacteria and phyla Bacteroidetes, and genera like Eubacterium, Alistipes, and Prevotellaand, were decreased.149 In addition to microbial composition, gut microbiota-derived metabolic products or endotoxins play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Long-chain fatty acids (particularly stearic acid and oleic acid) are elevated due to increased Prevotella and reduced Parabacteroides distasonis, exacerbating psoriatic dermatitis by enhancing the infiltration and cytokine secretion of DCs and Th17 in the lesional skin.145 Moreover, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are deficient because of decreased Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abundance, impair regulatory T cell (Treg) activation, thereby amplifying psoriatic inflammatory responses.150

Previous studies have demonstrated that gut dysbiosis, characterized by reduced richness and diversity of the gut microbiota, plays a significant role in the development of depression. Using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing, Zheng et al reported decreased relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and increased relative abundances of Actinobacteria in patients with depression compared to healthy controls.144 Futhermore, Jiang et al found that bacterial α-diversity in stool samples was elevated among individuals with depression. Notably, the levels of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes were significantly upregulated, while the level of Firmicutes was notably decreased in patients with depression.151 Emerging evidence also highlights the strong involvement of microbially derived molecules, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), neurotransmitters, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), and folic acid, in the etiology of depression.152 Specifically, a reduction in propionate and acetate, both SCFAs, was observed by Skonieczna-Zydecka et al in women with depression.153 Interestingly, the administration of propionate and acetate has been shown to alleviate depressive symptoms in mice,152 underscoring their potential therapeutic role in depression. Gut microbiota-produced neurotransmitters, such as serotonin (5-HT) and gamma amino butyric acid (GABA)], which are significantly decreased in germ-free mice, are crucial for promoting the pathological processes of depression.154 TMAO, an oxidation product of trimethylamine (TMA) produced by the gut microbiota during choline metabolism, can exacerbate depression-associated pathological changes by directly crossing the BBB.155,156 Moreover, disruption of vitamins metabolism, particularly folic acid deficiency caused by gut dysbiosis, is also implicated in the pathogenesis of depression.157

Overall, the evidence suggests that alterations in the gut microbiota may be critically involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis-related depression. Therefore, microbiota-targeted interventions might represent a promising innovative adjunctive therapy for both psoriasis and depression.

Future Perspectives

The brain was traditionally recognized as an “immune privileged” organ during the early 19th century. However, advancements in neuroimmunology research over the past few decades have challenged this traditional view, revealing a complex interplay between the immune system and brain. Giulia Castellani et al highlighted that immune niches in the brain, such as the choroid plexus, lymphatic drainage, meninges and skull bone marrow, are essential for brain immunity.158 This research suggests that Th17 cells might also be recruited through these immune niches, potentially contributing to depressive symptoms. Using 1.9-nanometer gold nanoparticles to trace their distribution, Scott et al demonstrated that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can directly flow through the peripheral nervous system (PNS).159 This finding indicates the possibility that pathogenic factors originating from the skin or PNS may influence brain function via the CSF, providing new insights into the mechanisms underlying psoriasis-related depression.

Previously, Guo et al identified that IMQ-stimulated mice exhibited significant psoriasis-like skin lesions and depressive behaviors. Of interest, noradrenaline (NE), which is released from the sympathetic nerves of the autonomic nervous system, is notably reduced in the prefrontal cortex.160 This finding suggests a potential role for sympathetic nerve activity in the pathogenesis of psoriasis-associated depression. Further investigation is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, the possible involvement of the parasympathetic nervous system, particularly the vagus nerve, remains unexplored in psoriasis-related depression. Further studies investigating the regulatory role of parasympathetic pathways in psoriasis and its associated neuropsychiatric disorders could offer valuable insights into novel therapeutic approaches.

Patients with psoriasis often suffer from poor sleep quality.161 Smith et al analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) involving 12,625 participants and confirmed a significant correlation between psoriasis and sleep disturbances (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.88; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.44–2.45).162 Furthermore, recent cross-sectional studies have shown that sleep disturbances, which can disrupt circadian rhythms, play a crucial role in the development of depression syndrome.163,164 Therefore, further research should be conducted to investigate the potential pathogenic effects and underlying regulatory mechanisms of poor sleep quality in psoriasis-associated depression, particularly focusing on circadian rhythm disruptions.

Besides topical treatments (such as topical corticosteroids, vitamin D3 analogues, and targeted phototherapy), oral systemic treatments (including methotrexate, ciclosporin, and acitretin) and biologics (such as Secukinumab, and Guselkumab), diet therapy has demonstrated therapeutic benefits for psoriasis. For instance, psoriatic patients adhering to the Mediterranean diet, which is comprised of nutrient-rich and antioxidant-packed foods (eg vegetables, legumes, and olive oil), often exhibit lower disease severity than those following a high-fat and high-sugar diet.165,166 In analyzing data from the UK Biobank comprising 180,446 participants, Ke et al found that higher adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet, which emphasizes fruits, vegetables, healthy fats, whole grains, and limits red meat, saturated fats, and added sugars,167 was associated with a reduced incidence of depression.168 These findings suggest that adopting healthier dietary patterns may confer significant benefits for psoriatic patients. Furthermore, these diets likely have a positive impact on mitigating the risk of psoriasis-related depression. However, future studies are required to elucidate the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

Exercise-based therapies have emerged as effective anti-inflammatory interventions for psoriasis management. Studies by Young et al and Rosety et al demonstrated that regular exercise provides significant health benefits for psoriatic patients, including reductions in fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disease activity.169 Furthermore, exercise not only promotes skin clearance but also enhances psychosocial functioning.170 However, the underlying mechanisms by which exercise improves psychological health remain to be fully understood. In a recent study, Zhang et al revealed that physical exercise effectively alleviates anxiety-like behaviors through enhanced synaptic structures, mediated by increased circulating lactate and its subsequent upregulation of synaptosome-associated protein 91 (SNAP91) lactylation.171 Such findings imply that future research could explore whether exercise exerts its beneficial effects on psoriasis-related depression through metabolism-associated epigenetic regulatory mechanisms.

A recent randomized, single-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial demonstrated that infliximab, a potent TNF-α antagonist widely used in the treatment of psoriasis, effectively alleviated motivational deficits in patients with major depression (MD) compared to the placebo group.172 These findings align with previous evidence suggesting that cytokines, particularly TNF-α, profoundly influence the pathogenesis of major depression. Furthermore, the findings substantiate the critical role of cytokine-mediated pathways in psoriasis-depression comorbidity, paving the way for potential clinical applications of other biological agents (such as IL-17A antagonists) for the treatment of major depression in the future.

For postmenopausal women with psoriasis and depression, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) might provide mild symptomatic relief due to estrogen’s anti-inflammatory properties. However, significant risks, including breast cancer and cardiovascular disease, are associated with HRT, and its effectiveness against psoriasis varies. A comprehensive assessment of individual risks versus benefits is crucial prior to initiation.

By analysis of a large cohort of 1,105,964 individuals, a recent study by Tyra Lagerberg et al showed that oral glucocorticoid therapy is linked to significantly increased risks of severe psychiatric sequelae, encompassing both the initiation and recurrence of common psychiatric disorders.173 Since potent topical corticosteroids (like clobetasol) may exert systemic effects, psoriatic patients receiving this therapy require additional monitoring for psychiatric adverse effects.

Serotonin is vital for both skin homeostasis and antidepressant activity; however, the efficacy of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as a treatment for psoriasis is controversial. One study indicated that Paroxetin, a classical antidepressant of SSRIs, eased the severity of psoriasis and depression syndrome in a case study by which two females suffering from major depression and psoriasis.174 However, other study showed that Paroxetin exacerbated and spread the psoriasis.175 Moreover, several studies demonstrated that psoriatic patients who had been taking fluoxetine (another SSRIs antidepressant) for a long period of time developed psoriasis.176 Large-scale longitudinal cohort studies are needed to distinguish between psoriasis patients who improved on SSRIs and those whose condition recurred or worsened.

Although existing studies suggest that gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to psoriasis-associated depression, large-scale longitudinal cohort studies and intervention trials targeting the gut microbiome remain scarce. In addition, many researches on depression in psoriasis (including gut dysbiosis, immune cell transmigration or the cutaneous HPA axis) rely on animal models; however, species differences may limit the translatability of findings to human pathogenesis. Large-scale human cohort studies remain urgently needed to validate the pathogenic mechanisms underlying depression in psoriasis. Furthermore, additional investigations employing multi-omics approaches are warranted to examine this comorbidity through integrated genomic, metabolomic, and gut microbial perspectives.

Conclusion

Due to the high comorbidity rate and severe psycho-social burdens of depression in psoriatic patients, elucidating the intrinsic pathophysiological mechanisms by which psoriasis contributes to depression is critically important. Immune dysregulation, particularly hyperactivated Th17 cell- and γδ T cell-mediated inflammatory responses, has been established as a key pathogenic link connecting psoriasis and depression. Additionally, hormonal imbalances, particularly dysregulation of female sex hormones during reproductive transitions (menstrual cycles, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause), contribute to the etiology of psoriasis-related depression. Moreover, neuroendocrine dysregulation (HPA-axis dysfunction) and neuropeptidergic disturbances (particularly reduced BDNF/NPY and elevated SP levels) constitute critical pathophysiological mechanisms linking psoriasis to depression. Recent advances in understanding the role of gut microbiota and their metabolites in psoriasis and depression pathogenesis have established novel therapeutic targets for precision interventions. Future research should prioritize a deeper exploration of these mechanisms, while investigating innovative therapeutic approaches for both psoriasis and depression symptom.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515030148); the Specific Fund of “Young Talents Program” of Guangdong College of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SZ2022QN10); Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by China Association of Chinese Medicine (2022-QNRC2-B07); Specific Fund of State Key Laboratory of Dampness Syndrome of Chinese Medicine (SZ2021ZZ23); the Specific Research Fund for TCM Science and Technology of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (YN2024HL04 and YN2024GZRPY072).

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicting interests in this work.

References

- 1.Armstrong AW, Blauvelt A, Callis Duffin K, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2025;11(1). doi: 10.1038/s41572-025-00630-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker JNWN. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taliercio M, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis comorbidities and their treatment impact. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42(3):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2024.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamazaki F. Psoriasis: comorbidities. J Dermatol. 2021;48(6):732–740. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mrowietz U, Sumbul M, Gerdes S. Depression, a major comorbidity of psoriatic disease, is caused by metabolic inflammation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(9):1731–1738. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salari N, Heidarian P, Hosseinian-Far A, Babajani F, Mohammadi M. Global prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among patients with skin diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prevention. 2024;45(4):611–649. doi: 10.1007/s10935-024-00784-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M, Fan S, Hong S, et al. Epidemiology of lipid disturbances in psoriasis: an analysis of trends from 2006 to 2023. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2024;18(8):103098. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2024.103098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etgü F, Dervis E. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e68037. doi: 10.7759/cureus.68037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramessur R, Saklatvala J, Budu-Aggrey A, et al. Exploring the link between genetic predictors of cardiovascular disease and psoriasis. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9(11):1009–1017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.2859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huong NTK, Long B, Doanh LH, et al. Associations of different inflammatory factors with atherosclerosis among patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Front Med. 2024;11:1396680. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1396680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Chada LM, Elman S, Villa-Ruiz C, Armstrong AW, Gottlieb AB, Merola JF. Psoriatic arthritis: a comprehensive review for the dermatologist part i: epidemiology, comorbidities, pathogenesis, and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;92(5):969–982. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elman SA, Perez-Chada LM, Armstrong A, Gottlieb AB, Merola JF. Psoriatic arthritis: a comprehensive review for the dermatologist. part ii: screening and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;92(5):985–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo J, Luo Q, Li C, et al. Evidence for the gut‐skin axis: common genetic structures in inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30(2):e13611. doi: 10.1111/srt.13611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding RL, Zheng Y, Bu J. Exploration of the biomarkers of comorbidity of psoriasis with inflammatory bowel disease and their association with immune infiltration. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29(12):e13536. doi: 10.1111/srt.13536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luna PC, Chu C-Y, Fatani M, et al. Psychosocial burden of psoriasis: a systematic literature review of depression among patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Therap. 2023;13(12):3043–3055. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-01060-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yıldırım YE, Polat M, Afacan Yıldırım E. Assessing psychosocial burden in psoriasis patients using the PRISM-RII tool: a comprehensive evaluation. Dermatol Pract Conceptual. 2025;15(1):4831. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1501a4831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samela T, Moretta G, Provini A, et al. Psoriasis and emotional dysregulation: a multicenter analysis of psychodermatology outcomes. Dermatol Pract Conceptual. 2025;15(2):4644. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1502a4644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams K, Lada G, Reynolds NJ, et al. Risk of suicide and suicidality in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the British association of dermatologists biologic and immunomodulators register (BADBIR). Clin Exp Dermatol. 2025;50(4):804–811. doi: 10.1093/ced/llae449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia Y-J, Liu P, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, sleeping problems, cognitive impairment, and suicidal ideation in people with autoimmune skin diseases. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sieminska I, Pieniawska M, Grzywa TM. The Immunology of psoriasis—current concepts in pathogenesis. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2024;66(2):164–191. doi: 10.1007/s12016-024-08991-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449(7162):564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang L, Yang X, Liang Y, Xie H, Dai Z, Zheng G. Transcription factor retinoid-related orphan receptor γt: a promising target for the treatment of psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1210. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangani D, Subramanian A, Huang L, et al. Transcription factor TCF1 binds to RORγt and orchestrates a regulatory network that determines homeostatic Th17 cell state. Immunity. 2024;57(11):2565–2582.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia X, Zhu L, Xu M, et al. ANKRD22 promotes resolution of psoriasiform skin inflammation by antagonizing NIK-mediated IL-23 production. Mol Ther. 2024;32(5):1561–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia XC, Cao GC, Sun GD, et al. GLS1-mediated glutaminolysis unbridled by MALT1 protease promotes psoriasis pathogenesis. J Clin Investig. 2020;130(10):5180–5196. doi: 10.1172/JCI129269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamata M, Tada Y. Crosstalk: keratinocytes and immune cells in psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1286344.doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1286344. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1286344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni X, Lai Y. Keratinocyte: a trigger or an executor of psoriasis? J Leukocyte Biol. 2020;108(2):485–491. doi: 10.1002/JLB.5MR0120-439R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu T, Zhong X, Luo N, Ma W, Hao P. Review of excessive cytosolic DNA and Its role in AIM2 and cGAS-STING mediated psoriasis development. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2024;17:2345–2357. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S476785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou L, Zhong Y, Li C, et al. MAPK14 as a key gene for regulating inflammatory response and macrophage M1 polarization induced by ferroptotic keratinocyte in psoriasis. Inflammation. 2024;47(5):1564–1584. doi: 10.1007/s10753-024-01994-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng F, Du S, Wu M, et al. The oncogenic kinase TOPK upregulates in psoriatic keratinocytes and contributes to psoriasis progression by regulating neutrophils infiltration. Cell Commun Signaling. 2024;22(1):386. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01758-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West PW, Tontini C, Atmoko H, et al. Human mast cells upregulate cathepsin B, a novel marker of itch in psoriasis. Cells. 2023;12(17):2177. doi: 10.3390/cells12172177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benezeder T, Bordag N, Woltsche J, et al. Mast cells express IL17A, IL17F and RORC in lesional psoriatic skin, are activated before therapy and persist in high numbers in a resting state with IL-17A positivity after treatment. J Dermatological Sci. 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2025.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Li L, Jiang J, et al. Role of type I cannabinoid receptor in sensory neurons in psoriasiform skin inflammation and pruritus. J Invest Dermatol. 2023;143(5):812–821.e813. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2022.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou X-Y, Chen K, Zhang J-A. Mast cells as important regulators in the development of psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1022986. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1022986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng Z, Peng S, Lin K, et al. Chronic stress-induced depression requires the recruitment of peripheral Th17 cells into the brain. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02543-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu X, Sakamoto S, Ishii C, et al. Dectin-1 signaling on colonic γδ T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses. Nat Immunol. 2023;24(4):625–636. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01447-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, et al. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nature Med. 2007;13(10):1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nm1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojkowska D, Szpakowski P, Glabinski A. Interleukin 17A promotes lymphocytes adhesion and induces CCL2 and CXCL1 release from brain endothelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5):1000. doi: 10.3390/ijms18051000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huppert J, Closhen D, Croxford A, et al. Cellular mechanisms of IL‐17‐induced blood‐brain barrier disruption. THE FASEB J. 2009;24(4):1023–1034. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baran P, Hansen S, Waetzig GH, et al. The balance of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-6·soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R), and IL-6·sIL-6R·sgp130 complexes allows simultaneous classic and trans-signaling. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(18):6762–6775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandey GN. Inflammatory and innate immune markers of neuroprogression in depressed and teenage suicide brain. Mod Trends Pharmacopsych. 2017;79–95. doi: 10.1159/000470809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong N, Zhang Y, Yang A, Dai X, Hao S. The potency of common proinflammatory cytokines measurement for revealing the risk and severity of anxiety and depression in psoriasis patients. J Clin Lab Analysis. 2022;36(9):e24643. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang J, Zhao S, Su Y, et al. Psychological stress overactivates IL‐23/Th17 inflammatory axis and increases cDC2 in imiquimod‐induced psoriasis models of C57BL/6 mice. Exper Dermatol. 2025;34(6):e70128. doi: 10.1111/exd.70128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keenan EL, Granstein RD. Proinflammatory cytokines and neuropeptides in psoriasis, depression, and anxiety. Acta Physiol. 2025;241(3):e70019. doi: 10.1111/apha.70019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beurel E, Lowell JA. Th17 cells in depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;69:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khantakova JN, Mutovina A, Ayriyants KA, Bondar NP. Th17 cells, glucocorticoid resistance, and depression. Cells. 2023;12(23):2749.doi:10.3390/cells12232749. doi: 10.3390/cells12232749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siffrin V, Radbruch H, Glumm R, et al. In vivo imaging of partially reversible Th17 cell-induced neuronal dysfunction in the course of encephalomyelitis. Immunity. 2010;33(3):424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertollo AG, Mingoti MED, Ignácio ZM. Neurobiological mechanisms in the kynurenine pathway and major depressive disorder. Rev Neuroscie. 2024;36(2):169–187.doi:10.1515/revneuro–2024–0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Chen B, Di Z, et al. Involvement of kynurenine pathway between inflammation and glutamate in the underlying etiopathology of CUMS-induced depression mouse model. BMC Neuro. 2022;23(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12868-022-00746-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X, Xu D, Yu J, Song X-J, Li X, Cui Y-L. Tryptophan metabolism disorder-triggered diseases, mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies: a scientometric review. Nutrients. 2024;16(19):3380. doi: 10.3390/nu16193380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang S, Han J, Ye Z, et al. The correlation of inflammation, tryptophan-kynurenine pathway, and suicide risk in adolescent depression. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;34(5):1557–1567. doi: 10.1007/s00787-024-02579-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonzalez Caldito N. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the central nervous system: a focus on autoimmune disorders. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1213448. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1213448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsuboi H, Sakakibara H, Minamida-Urata Y, et al. Serum TNFα and IL-17A levels may predict increased depressive symptoms: findings from the Shika study cohort project in Japan. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2024;18(1):20.doi:10.1186/s13030–024–00317–5. doi: 10.1186/s13030-024-00317-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh Gautam A, Kumar Singh R. Therapeutic potential of targeting IL-17 and its receptor signaling in neuroinflammation. Drug Discovery Today. 2023;28(4):103517. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumari S, Dhapola R, Sharma P, Nagar P, Medhi B, HariKrishnaReddy D. The impact of cytokines in neuroinflammation-mediated stroke. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024;78:105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2024.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H, Han S, Xie J, Zhao R, Li S, Li J. IL-17A exacerbates caspase-12-dependent neuronal apoptosis following ischemia through the Src-PLCγ-calpain pathway. Exp Neurol. 2024;379:114863. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.114863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lv X-J, Lv -S-S, Wang G-H, et al. Glia-derived adenosine in the ventral hippocampus drives pain-related anxiodepression in a mouse model resembling trigeminal neuralgia. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;117:224–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Y, Huang T, Zhang H, et al. Formononetin improves cardiac function and depressive behaviours in myocardial infarction with depression by targeting GSK-3β to regulate macrophage/microglial polarization. Phytomedicine. 2023;109:154602. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guadalupi L, Vanni V, Balletta S, et al. Interleukin-9 protects from microglia- and TNF-mediated synaptotoxicity in experimental multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21(1):128. doi: 10.1186/s12974-024-03120-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandal G, Kirkpatrick M, Alboni S, Mariani N, Pariante CM, Borsini A. Ketamine prevents inflammation-induced reduction of human hippocampal neurogenesis via inhibiting the production of neurotoxic metabolites of the kynurenine pathway. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2024;27(10):pyae041. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyae041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borsini A, Alboni S, Horowitz MA, et al. Rescue of IL-1β-induced reduction of human neurogenesis by omega-3 fatty acids and antidepressants. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;65:230–238.doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cassalia F, Lunardon A, Frattin G, Danese A, Caroppo F, Fortina AB. How hormonal balance changes lives in women with psoriasis. J Clin Med. 2025;14(2):582. doi: 10.3390/jcm14020582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arvind A, Sreelekshmi S, Genetic DN. Epigenetic, and hormonal regulation of stress phenotypes in major depressive disorder: from maladaptation to resilience. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2025;45(1):29. doi: 10.1007/s10571-025-01549-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hulubă I-P, Crecan‑Suciu B, Păunescu R, Micluția I. The link between sex hormones and depression over a woman’s lifespan (Review). Biomed Rep. 2025;22(4):1–11.doi:10.3892/br.2025.1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe Y, Makino E, Tajiki-Nishino R, et al. Involvement of estrogen receptor α in pro-pruritic and pro-inflammatory responses in a mouse model of allergic dermatitis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2018;355:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunsing RL, Prossnitz ER. Induction of interleukin-10 in the T helper type 17 effector population by the G protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) agonist G-1. Immunology. 2011;134(1):93–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03471.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo D, Liu X, Zeng C, et al. Estrogen receptor β activation ameliorates DSS-induced chronic colitis by inhibiting inflammation and promoting Treg differentiation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;77:105971. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adachi A, Honda T. Regulatory roles of estrogens in psoriasis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(16):4890. doi: 10.3390/jcm11164890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Albert KM, Newhouse PA. Estrogen, stress, and depression: cognitive and biological interactions. Annual Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15(1):399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jiang X, Chen Z, Yu X, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depression is associated with estrogen receptor-α/SIRT1/NF-κB signaling pathway in old female mice. Neurochem Int. 2021;148:105097. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tan Z, Li Y, Guan Y, et al. Klotho regulated by estrogen plays a key role in sex differences in stress resilience in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1206. doi: 10.3390/ijms24021206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shanley MR, Miura Y, Guevara CA, et al. Estrous cycle mediates midbrain neuron excitability altering social behavior upon stress. J Neurosci. 2023;43(5):736–748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1504-22.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim W, Chung C. Effect of dynamic interaction of estrous cycle and stress on synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability in the lateral habenula. THE FASEB J. 2024;38(24):e70275. doi: 10.1096/fj.202402296RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hellberg S, Raffetseder J, Rundquist O, et al. Progesterone dampens immune responses in in vitro activated CD4+ T cells and affects genes associated with autoimmune diseases that improve during pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:672168. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.672168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Espinosa-Garcia C, Atif F, Yousuf S, Sayeed I, Neigh GN, Stein DG. Progesterone attenuates stress-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and enhances autophagy following ischemic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3740. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Espinosa-Garcia C, Sayeed I, Yousuf S, et al. Stress primes microglial polarization after global ischemia: therapeutic potential of progesterone. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;66:177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cassalia F, Belloni Fortina A. Psoriasis in women with psoriatic arthritis: hormonal effects, fertility, and considerations for management at different stages of life. Reumatismo. 2024;76(3):10.4081. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2024.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ceovic R, Mance M, Bukvic Mokos Z, Svetec M, Kostovic K, Stulhofer Buzina D. Psoriasis: female skin changes in various hormonal stages throughout life—puberty, pregnancy, and menopause. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:571912. doi: 10.1155/2013/571912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murase JE, Chan KK, Garite TJ, Cooper DM, Weinstein GD. Hormonal effect on psoriasis in pregnancy and post-partum. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(5):601–606. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.5.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Süss H, Willi J, Grub J, Ehlert U. Estradiol and progesterone as resilience markers? – findings from the Swiss perimenopause study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;127:105177. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reddy DS. Neuroendocrine insights into neurosteroid therapy for postpartum depression. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29(12):979–982.doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2023.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frye CA, Cleveland DM, Sadarangani A, Torgersen JK. Progesterone promotes anti-anxiety/depressant-like behavior and trophic actions of BDNF in the hippocampus of female nuclear progesterone receptor, but not 5α-reductase, knockout mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1173. doi: 10.3390/ijms26031173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mu E, Chiu L, Kulkarni J. Using estrogen and progesterone to treat premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postnatal depression and menopausal depression. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1528544. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1528544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang H, Li X, Xue F, et al. Local production of prolactin in lesions may play a pathogenic role in psoriatic patients and imiquimod‐induced psoriasis‐like mouse model. Exper Dermatol. 2018;27(11):1245–1253. doi: 10.1111/exd.13772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Medina J, De Guzman RM, Workman JL. Prolactin mitigates chronic stress-induced maladaptive behaviors and physiology in ovariectomized female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2024;258110095. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2024.110095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Göver T, Slezak M. Targeting glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathway for treatment of stress-related brain disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2024;76(6):1333–1345.doi:10.1007/s43440–024–00654–w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jozic I, Stojadinovic O, Kirsner RSF, Tomic-Canic M. Skin under the (Spot)-light: cross-talk with the central Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) Axis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(6):1469–1471. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marek-Jozefowicz L, Czajkowski R, Borkowska A, et al. The brain–skin axis in psoriasis—psychological, psychiatric, hormonal, and dermatological aspects. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):669. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mar K, Rivers JK. The mind body connection in dermatologic conditions: a literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27(6):628–640. doi: 10.1177/12034754231204295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu H, Zhang Y, Hou X, et al. CRHR1 antagonist alleviated depression-like behavior by downregulating p62 in a rat model of post-stroke depression. Exp Neurol. 2024;378:114822. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.114822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Todorovic C, Sherrin T, Pitts M, Hippel C, Rayner M, Spiess J. Suppression of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway reverses depression-like behaviors of CRF2-Deficient mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;34(6):1416–1426. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun J, Qiu L, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Ju L, Yang J. CRHR1 antagonist alleviates LPS-induced depression-like behaviour in mice. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-04519-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leis K, Mazur E, Jabłońska M, Kolan M, Gałązka P. Endocrine systems of the skin. Adv Dermatol Allergology. 2019;36(5):519–523. doi: 10.5114/ada.2019.89502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harvima IT, Nilsson G. Stress, the neuroendocrine system and mast cells: current understanding of their role in psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immu. 2014;8(3):235–241. doi: 10.1586/eci.12.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pondeljak N, Lugović-Mihić L. Stress-induced interaction of skin immune cells, hormones, and neurotransmitters. Clin Ther. 2020;42(5):757–770. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim JE, Cho DH, Kim HS, et al. Expression of the corticotropin‐releasing hormone–proopiomelanocortin axis in the various clinical types of psoriasis. Exper Dermatol. 2006;16(2):104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Haimakainen S, Harvima IT. Corticotropin‐releasing hormone receptor‐1 is increased in mast cells in psoriasis and actinic keratosis, but not markedly in keratinocyte skin carcinomas. Exper Dermatol. 2023;32(10):1794–1804. doi: 10.1111/exd.14903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou C, Yu X, Cai D, Liu C, Li C. Role of corticotropin-releasing hormone and receptor in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Med Hypotheses. 2009;73(4):513–515. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pietrzak R, Rykowski P, Pasierb A, et al. Adrenocorticotropin/cortisol ratio – a marker of psoriasis severity. Adv Dermatol Allergology. 2020;37(5):746–750. doi: 10.5114/ada.2019.83975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rajasekharan A, Munisamy M, Menon V, Mohan Raj PS, Priyadarshini G, Rajappa M. Stress and psoriasis: exploring the link through the prism of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammation. J Psychosomatic Res. 2023;170:111350. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Calapai M, Puzzo L, Bova G, et al. Effects of physical exercise and motor activity on depression and anxiety in post-mastectomy pain syndrome. Life. 2024;14(1):77. doi: 10.3390/life14010077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Araki R, Kita A, Yabe T. Decreased brain pH underlies behavioral and brain abnormalities induced by chronic exposure to glucocorticoids in mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2024;47(11):1836–1845. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b24-00251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cotella EM, Mestres Lascano I, Franchioni L, Levin GM, Suárez MM. Long-term effects of maternal separation on chronic stress response suppressed by amitriptyline treatment. Stress. 2013;16(4):477–481. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2013.775241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ibi D, Nakasai G, Sawahata M, et al. Emotional behaviors as well as the hippocampal reelin expression in C57BL/6N male mice chronically treated with corticosterone. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;230:173617. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2023.173617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hisaoka-Nakashima K, Azuma H, Ishikawa F, et al. Corticosterone induces HMGB1 release in primary cultured rat cortical astrocytes: involvement of pannexin-1 and P2X7 receptor-dependent mechanisms. Cells. 2020;9(5):1068. doi: 10.3390/cells9051068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hisaoka-Nakashima K, Takeuchi Y, Saito Y, et al. Glucocorticoids induce HMGB1 release in primary cultured rat cortical microglia. Neuroscience. 2024;560:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hermoso MA, Matsuguchi T, Smoak K, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoids and tumor necrosis factor alpha cooperatively regulate toll-like receptor 2 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(11):4743–4756. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4743-4756.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hu W, Zhang Y, Wu W, et al. Chronic glucocorticoids exposure enhances neurodegeneration in the frontal cortex and hippocampus via NLRP-1 inflammasome activation in male mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;52:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Feng X, Zhao Y, Yang T, et al. Glucocorticoid-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation in hippocampal microglia mediates chronic stress-induced depressive-like behaviors. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:210.doi:10.3389/fnmol.2019.00210. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chiang T-I, Hung -Y-Y, Wu M-K, Huang Y-L, Kang H-Y. TNIP2 mediates GRβ-promoted inflammation and is associated with severity of major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;95:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li H, Ge M, Lu B, et al. Ginsenosides modulate hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function by inhibiting FKBP51 on glucocorticoid receptor to ameliorate depression in mice exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Phytother Res. 2024;38(10):5016–5029. doi: 10.1002/ptr.8075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stander S, Schmelz M. Skin innervation. J Invest Dermatol. 2024;144(8):1716–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2023.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shastri M, Sharma M, Sharma K, et al. Cutaneous-immuno-neuro-endocrine (CINE) system: a complex enterprise transforming skin into a super organ. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33(3):e15029. doi: 10.1111/exd.15029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pardossi S, Fagiolini A, Cuomo A. Variations in BDNF and their role in the neurotrophic antidepressant mechanisms of ketamine and esketamine: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):13098. doi: 10.3390/ijms252313098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Duman RS, Deyama S, Fogaça MV. Role of BDNF in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: activity‐dependent effects distinguish rapid‐acting antidepressants. Eur J Neurosci. 2019;53(1):126–139. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yang T, Nie Z, Shu H, et al. The role of BDNF on neural plasticity in depression. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:82. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brunoni AR, Lotufo PA, Sabbag C, Goulart AC, Santos IS, Benseñor IM. Decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor plasma levels in psoriasis patients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015;48(8):711–714. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20154574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sjahrir M, Roesyanto-Mahadi ID, Effendy E. Correlation between serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor level and depression severity in psoriasis vulgaris patients. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(4):583–586. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.JiaWen W, Hong S, ShengXiang X, Jing L. Depression- and anxiety-like behaviour is related to BDNF/TrkB signalling in a mouse model of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(3):254–261.doi:10.1111/ced.13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang W, Xu T, Chen X, et al. NPY receptor 2 mediates NPY antidepressant effect in the mPFC of LPS rat by suppressing NLRP3 signaling pathway. Mediators Inflammation. 2019;2019:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2019/7898095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kupcova I, Danisovic L, Grgac I, Harsanyi S. Anxiety and depression: what do we know of neuropeptides? Behav Sci. 2022;12(8):262. doi: 10.3390/bs12080262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ozsoy S, Olguner Eker O, Abdulrezzak U. The effects of antidepressants on neuropeptide Y in patients with depression and anxiety. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49(01):26–31. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1565241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Reich A, Orda A, Winicka B, Szepietowski JC. Plasma neuropeptides and perception of pruritus in psoriasis. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2007;87(4):299–304. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gao T, Ma H, Xu B, Bergman J, Larhammar D, Lagerström MC. The neuropeptide Y system regulates both mechanical and histaminergic itch. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(11):2405–2411. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Remröd C, Lonne-Rahm S, Nordlind K. Study of substance P and its receptor neurokinin-1 in psoriasis and their relation to chronic stress and pruritus. Arch Dermatological Res. 2007;299(2):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0745-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Guo J, Qi C, Liu Y, et al. Terrestrosin D ameliorates skin lesions in an imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like murine model by inhibiting the interaction between substance P and dendritic cells. Phytomedicine. 2022;95:153864. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Siiskonen H, Harvima I. Mast cells and sensory nerves contribute to neurogenic inflammation and pruritus in chronic skin inflammation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:42.18. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Qi C, Feng F, Guo J, et al. Electroacupuncture on Baihui (DU20) and Xuehai (SP10) acupoints alleviates psoriatic inflammation by regulating neurotransmitter substance P- neurokinin-1 receptor signaling. J Traditional Complementary Med. 2024;14(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2023.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Xie L, Takahara M, Nakahara T, et al. CD10-bearing fibroblasts may inhibit skin inflammation by down-modulating substance P. Arch Dermatological Res. 2010;303(1):49–55. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1093-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bondy B, Baghai TC, Minov C, et al. Substance P serum levels are increased in major depression: preliminary results. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;53(6):538–542. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01544-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Argyropoulos SV, Nutt DJ. Substance P antagonists: novel agents in the treatment of depression. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2005;9(8):1871–1875. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Almeida A, Mitchell AL, Boland M, et al. A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2019;568(7753):499–504. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0965-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Li Y, Ye Z, Zhu J, Fang S, Meng L, Zhou C. Effects of gut microbiota on host adaptive immunity under immune homeostasis and tumor pathology state. Front Immunol. 2022;13:844335. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.844335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mavros CF, Bongers M, Neergaard FBF, et al. Bacteria engineered to produce serotonin modulate host intestinal physiology. ACS Synth Biol. 2024;13(12):4002–4014. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.4c00453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang H, Cai Y, Wu W, Zhang M, Dai Y, Wang Q. Exploring the role of gut microbiome in autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive review. Autoimmunity Rev. 2024;23(12):103654. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2024.103654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mu F, Rusip G, Florenly F. Gut microbiota and autoimmune diseases: insights from mendelian randomization. FASEB BioAdv. 2024;6(11):467–476. doi: 10.1096/fba.2024-00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Song Y, Shi M, Wang Y. Deciphering the role of host-gut microbiota crosstalk via diverse sources of extracellular vesicles in colorectal cancer. Mol Med. 2024;30(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s10020-024-00976-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ruiz‐Malagón AJ, Rodríguez‐Sojo MJ, Redondo E, Rodríguez‐Cabezas ME, Gálvez J, Rodríguez‐Nogales A. Systematic review: the gut microbiota as a link between colorectal cancer and obesity. Obesity Rev. 2025;26(4):e13872. doi: 10.1111/obr.13872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.You M, Chen N, Yang Y, et al. The gut microbiota–brain axis in neurological disorders. MedComm. 2024;5(8):e656. doi: 10.1002/mco2.656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nakhal MM, Yassin LK, Alyaqoubi R, et al. The microbiota–gut–brain axis and neurological disorders: a comprehensive review. Life. 2024;14(10):1234.doi:10.3390/life14101234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Duan YF, Dai JH, Lu YQ, Qiao H, Liu N. Disentangling the molecular mystery of tumour–microbiota interactions: microbial metabolites. Clin Translational Med. 2024;14(11):e70093. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.70093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Mayneris-Perxachs J, Castells-Nobau A, Arnoriaga-Rodríguez M, et al. Microbiota alterations in proline metabolism impact depression. Cell Metab. 2022;34(5):681–701.e610. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):786–796. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhao Q, Yu J, Zhou H, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis exacerbates the pathogenesis of psoriasis-like phenotype through changes in fatty acid metabolism. Signal Transduc Targeted Therap. 2023;8(1):40. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zou X, Gao L, Zhao H, Zhao H. Gut microbiota and psoriasis: pathogenesis, targeted therapy, and future directions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1430586.doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1430586. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1430586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Hidalgo‐Cantabrana C, Gómez J, Delgado S, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in a cohort of patients with psoriasis. Brit J Dermatol. 2019;181(6):1287–1295. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Shapiro J, Cohen NA, Shalev V, Uzan A, Koren O, Maharshak N. Psoriatic patients have a distinct structural and functional fecal microbiota compared with controls. J Dermatol. 2019;46(7):595–603. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Xiao S, Zhang G, Jiang C, et al. Deciphering gut microbiota dysbiosis and corresponding genetic and metabolic dysregulation in psoriasis patients using metagenomics sequencing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:605825.doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.605825. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.605825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. The defect in regulatory T cells in psoriasis and therapeutic approaches. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3880. doi: 10.3390/jcm10173880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]