Abstract

Primary Sjogren’s disease (pSD) is a systemic autoimmune disease. Currently, the causes of pSD remain unknown, and no curative therapies are available. Our prior studies showed Tlr7 activation was an important driver of pSD in females. Since Tlr7 is regulated by Tlr9, we hypothesized that ablation of Tlr9 would exacerbate disease in a Tlr7-dependent manner. Towards this end, we generated pSD mice that lacked systemic expression of either Tlr9 (NOD.B10Tlr9−/−) or both Tlr7 and Tlr9 (NOD.B10Tlr-DKO). We harvested tissues for histologic analysis and assessed disease-relevant immune cell populations in secondary lymphoid organs. We examined total and autoreactive antibody levels in sera. Enhanced nephritis was observed in Tlr9-deficient females, while dacryoadenitis was increased in males that lacked Tlr9, and these manifestations were dependent on Tlr7. Moreover, the percentages of splenic Tlr7+ B cells, germinal center and age-associated B cells, CD4+ and CD8+ activated/memory T cells, and Tfh cells were increased in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 mice, and this expansion was abrogated in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. Finally, total IgM levels were elevated in sera from NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to the parental strain and autoreactive IgM and IgG were also enriched in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females. NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females and males showed dramatically reduced IgM and IgG titers as compared to the NOD.B10 strain and anti-nuclear autoantibodies were diminished in this strain. Overall, our study revealed that ablation of Tlr9 drives pSD in females but has negligible effects on disease in males. Moreover, Tlr9 regulates Tlr7-dependent pSD manifestations in a sex-biased manner.

Keywords: MyD88, Sialadenitis, salivary gland, B cell, autoantibody, autoimmunity

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Primary Sjögren’s disease (pSD) is the second most prevalent autoimmune disease in the United States, characterized by chronic inflammation and progressive destruction of moisture-producing glands [1]. The prevalence of pSD is 0.3 – 3 per 1000 of general population. It predominantly affects middle-aged women, and exhibits a striking female predilection, with a female-to-male ratio of at least 9:1 [2–4]. In addition to exocrine dysfunction, 30 to 40% of patients with pSD display extra-glandular manifestations, including interstitial nephritis and pneumonitis [1]. Moreover, pSD is characterized by B cell dysfunction, as hypergammaglobulinemia, autoantibodies, and increased risk of B cell lymphoma are observed [1, 5]. The etiology of pSD, and the reasons why this disease shows such a striking female predominance, remain incompletely understood. Current treatments palliate symptoms but do not target underlying disease mechanisms.

To identify pathways with therapeutic relevance to pSD, we have focused on MyD88, a signaling adaptor used by most toll-like receptors (TLRs) and IL-1 receptor family members [6]. MyD88 is crucial in bridging innate and adaptive immunity and numerous studies demonstrate an essential role for Myd88-dependent pathways in the initiation and progression of many different autoimmune diseases [7–13]. Myd88 signaling can mediate pathologic inflammatory responses through heightened production of type I interferon (IFN) and upregulation of IFN-stimulated genes, thus driving the development of autoimmunity [14, 15]. Early studies by our group demonstrated that Myd88 is crucial for the pathogenesis of pSD [16–18]. Moreover, MyD88-dependent signaling cascades are dysregulated in pSD patients in both salivary glands and systemically [19, 20], and MyD88 is upregulated in monocytes derived from pSD patients [21].

Elegant studies using samples from patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and murine lupus models have shown a crucial role for 2 endosomal TLRs that rely on MyD88 in disease, TLR7 and TLR9. Indeed, genes encoding endosomal TLRs themselves and associated signaling intermediates are recognized as risk alleles in patients with SLE including TLR7, TLR9, TRAF4, IRF5, and IRAK1 [7, 22, 23]. Functional studies confirm the importance of these pathways in disease [24–26]. These findings are replicated in lupus mouse models where Tlr7 activation mediates many organ-specific disease manifestations, including glomerulonephritis, and cardiac and pulmonary disease [25, 27–30]. Several studies revealed that B cell-intrinsic Tlr7 signaling mediates disease in mice, and TLR7 mediates expansion of B cell subsets that drive pathology in patients including age-associated B cells (ABCs) or DN2 cells, germinal center (GC) B cells, and plasmablasts [28, 31–34].

In contrast, Tlr9 plays a protective role in lupus pathogenesis. Indeed, systemic ablation of Tlr9 in multiple mouse models of lupus exacerbates the disease, leading to severe disease progression and significantly reduced lifespans [9, 27, 35–37]. In vivo and in vitro studies demonstrated that Tlr9-deficient B cells are prone to differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells [38]. Moreover, Tlr9 hinders the survival of autoreactive B cells in the periphery and maintains immune tolerance to RNA-associated antigens by suppression of excessive antibody class-switching and regulation of B cell maturation to prevent autoimmunity [24, 39, 40]. Further studies found that expression of Tlr9 in the B cell compartment governs disease, as overexpression of Tlr9 in B cells ameliorates lupus nephritis and conditional deletion of B cell-specific Tlr9 exacerbates the disease [41, 42].

Since both Tlr7 and Tlr9 rely on Myd88 for signaling, there has been considerable effort to understand the seemingly paradoxical effects of these receptors in autoimmunity. Indeed, Tlr7 activation is restrained by Tlr9, as MRL/lpr mice that are deficient in both Tlr7 and Tlr9 show attenuated disease as compared to strain-matched controls that lack expression of Tlr9 alone [9]. This regulation has been shown to be particularly important in the B cell compartment, as Tlr9 restricts the Tlr7-mediated differentiation of B cells in vitro by limiting BCR and Tlr activation [38]. Studies using Tlr7 conditional knockout MRL/lpr mice that also lacked systemic expression of Tlr9 confirmed the importance of Tlr7 and Tlr9 signaling in the B cell compartment, as ablation of Tlr7 in B cells, but not monocytes, resulted in reduced proteinuria and glomerular disease when compared to Tlr7-sufficient controls that lacked expression of Tlr9 [43].

Given the importance of endosomal TLRs in lupus, we undertook studies to determine the roles of these receptors in pSD. TLR7 and TLR9 are upregulated in salivary gland epithelial cells, minor salivary glands and in parotid tissue of pSD patients [44–46]. In addition, TLR7 and TLR9 signaling is enhanced in B cells, CD14+ monocytes, and PBMCs derived from pSD patients [21, 45, 47–49]. While endosomal TLRs are dysregulated within exocrine tissue and in the periphery in the context of pSD, the way in which these receptors contribute to disease remains poorly understood.

Our prior work demonstrated that Tlr7 agonism accelerated disease progression in pSD females and drove expansion of ABCs, a B cell subset shown to be pathogenic in other autoimmune diseases [50, 51]. Additionally, we found that Tlr7 drives tissue-specific disease in a sex-biased manner in pSD, as Tlr7 was primarily pathogenic in females, but was protective in males [52]. Since Tlr7 plays a key role in pSD and Tlr9 regulates Tlr7 activation in the context of lupus, we sought to determine if Tlr9 mediated pSD exocrine-specific and systemic disease manifestations in a sex-biased manner, and if this was dependent on Tlr7 expression. We employed a well characterized pSD mouse model termed NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J (NOD.B10) for our studies. NOD.B10 mice recapitulate numerous characteristics of pSD observed in humans [1, 53–55]. For instance, NOD.B10 mice show sex-biased disease and NOD.B10 females develop spontaneous pSD manifestations by 26 weeks of age that is characterized by reduced salivary flow, organ-specific inflammation including, salivary and lacrimal glands, kidneys and lungs, as well as elevated anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) in sera [52–54, 56, 57]. To investigate the contribution of Tlr9 to disease and to determine whether specific disease manifestations were dependent on Tlr7 in a sex-biased manner, we generated NOD.B10 mice that lacked either Tlr9 (NOD.B10Tlr9−/−) or both Tlr7 and Tlr9 systemically (NOD.B10Tlr-DKO).

Results of our study revealed that Tlr9 mediates both local and systemic disease manifestations in pSD mice in a sex-biased manner. Indeed, ablation of Tlr9 in females enhanced nephritis and resulted in expansion of B and T cell subsets associated with disease. Total and ANA-specific antibodies were also enriched in female NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice. Significantly, many of these disease manifestations were diminished in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females, indicating the heightened disease observed in Tlr9-deficient animals was dependent on Tlr7 expression. In contrast, ablation of Tlr9 resulted in few phenotypic changes in our male pSD mice, although dacryoadenitis was enhanced in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− males. Thus, ablation of Tlr9 exacerbated disease in female mice but had negligible effects in males. Collectively, our results revealed that Tlr9-dependent signals restrain inflammation in pSD in a sex-specific manner and many disease manifestations are dependent on Tlr7. Our study provides a mechanistic understanding regarding the role of endosomal Tlrs in pSD and this work will inform our knowledge regarding design of novel therapeutics to treat sex- and tissue-specific pSD manifestations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice.

NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J (NOD.B10) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (stock # 001925). To generate Tlr9-deficient animals on the NOD.B10 genetic background (NOD.B10Tlr9−/−), C57BL/6-Tlr9em1.1Ldm/J mice (stock # 034449) were bred to the NOD.B10 strain for 7 generations. Progeny were verified to be congenic with the NOD.B10 strain using a speed congenics approach (Jackson Laboratories). To generate NOD.B10 mice that lacked both Tlr7 and Tlr9, Tlr7-deficient NOD.B10 mice previously generated and validated in our laboratory were bred to the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− animals [52]. The resulting mice that lack both Tlr7 and Tlr9 are designated as NOD.B10Tlr-DKO. All animals in this study were euthanized at 26 – 30 weeks of age, which is the clinical disease stage [53, 54], unless otherwise indicated. Mice were maintained in the Laboratory Animal Facility at the University of Buffalo in accordance with the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) of the University at Buffalo and US NIH guidelines.

2.2. Sex as a biologic variable.

Both male and female mice were used as indicated.

2.3. RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

Spleens were harvested, snap frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until use. Total RNA was extracted by resuspending the respective spleens in Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using BioMashers (TaKaRa). The RNA was phase separated by chloroform and further isolated using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research). Isolated RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). All qRT-PCR assays were performed in triplicates in at least three independent experiments. Relative expression values of each target gene were normalized to β-actin expression. The following primers were used for qRT-PCR:

Tlr7 forward 5’- CTG ACC GCC ACA ATC ACG TCA TG -3’

Tlr7 reverse 5’- GCT TGT CTG TGC AGTCCA CG -3’

Tlr9 forward 5’- CTC TGA GAG ACC CTG GTG TGG -3’

Tlr9 reverse 5’- GGT GCA GAG TCC TTC GAC GG -3’

β-actin forward 5’- TCT TGG GTA TGG AAT CCT GTG GC -3’

β-actin reverse 5’- GCA ATG CCT GGG TAC ATG GTG G -3’

2.4. Collection of tissue for histologic analysis.

Submandibular glands (SMG), lacrimal glands, lungs, and kidneys were harvested. Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded, and H&E-stained. Slides were scanned using Aperio Scan Scope. For each organ, a representative tissue section was scanned, and the area of inflammation and the total tissue area examined was quantified using ImageJ. The percent area of inflammation was calculated by dividing the area of inflammation by the total tissue area examined and multiplying by 100, as previously described [18].

2.5. Saliva and sera collection.

Stimulated saliva was collected following intraperitoneal injection of 0.3 mg of pilocarpine HCl dissolved in 100 μL of PBS. Saliva was collected for 10 minutes and placed on ice. Saliva was centrifuged briefly and quantified by pipette. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Blood was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 700 g and sera were collected and stored at −20° C until use.

2.6. Cell culture conditions.

Spleens were harvested from the indicated strains and mechanically dispersed. Red blood cell (RBC) lysis was performed, and cells were counted using a hemocytometer. Cells (0.5 × 106) were plated in 24 well plates and were cultured overnight in media alone (2% FBS in RPMI as previously described [58]), or in media containing Imiquimod (Imq) (Invivogen) at a concentration of 0.625, or 0.313 μg/mL as indicated. Cells were also stimulated with CpG class B (0.625 μM) (ODN 1826, Invivogen) or with a CpG control (0.625 μM) (ODN 2138, Invivogen). Cells were also stimulated with Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from S. typhimurium (25 μg/mL) (Sigma Aldrich). Cells were cultured overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator and supernatants and cells were harvested as indicated.

2.7. Harvesting of peripheral lymphoid tissues and flow cytometry.

Cervical lymph nodes (cLNs) and spleens were harvested and mechanically dispersed. RBC lysis was performed on splenocytes and flow cytometry was performed using the following fluorescently-labeled antibodies: B220 (clone RA3–6B2, BD Biosciences), CD23 (clone B3B4, Biolegend), CD21/35 (clone 7G6, BD Biosciences), T-bet (clone 4B10, BD Biosciences), CD11c (clone N418, BioLegend), CD11b (clone M1/70, BD Biosciences), Fas (clone Jo2, BD Biosciences), GL7 (clone GL7, BioLegend), CD138 (clone 281–2, BD Biosciences), CD4 (clone GK1.5, BD Biosciences), CD8α (clone 53–6.7, BD Biosciences), CD44 (clone IM7, BD Biosciences), CD62L (clone MEL-14, BD Biosciences), CD69 (clone H1.2F3, Biolegend) Tlr7 (clone A94B10, BD Biosciences), Tlr9 (clone J157A7, BD Biosciences), TCRβ (clone H57–597, BD Biosciences), PD1 (clone J43, Invitrogen), and CXCR5 (clone SPRCL5, Invitrogen). Data were acquired using a Fortessa (BD Biosciences) and quantified using Flow Jo (BD Biosciences).

2.8. Antibody and IL-6 ELISAs.

Sera were serially diluted and ELISAs were performed to quantify total IgM and IgG (Invitrogen). IL-6 and IFNα were measured in the tissue culture supernatants (Invitrogen and PBL Assay Science, respectively). All samples were analyzed in duplicate in accordance with manufacturer instructions.

2.9. HEp-2 Assays and autoantigen arrays.

Female sera were diluted 1:100 and male sera were diluted 1:50. Sera were incubated with HEp-2 sides (MBL Bion) in accordance with manufacturer instructions. Bound IgG was detected using mouse anti-IgG conjugated to FITC (Southern Biotech). Confocal microscopy was performed, and ANA patterns were identified as previously published [59]. Sera were harvested and sent to UT Southwestern for autoantigen array analysis.

2.10. Data Analysis.

Statistical tests were performed as indicated using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.3.1) and the R programming environment [60]. In experiments shown in Figures 2 and 3 where 2 groups of mice were compared, Mann-Whitney tests at level 0.05 were performed. Data were also analyzed by comparing values for the 4 strains of mice (NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9+/−, NOD.B10Tlr9−/−, and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO) for each sex. Analyses were performed using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test at level 0.05 was applied to assess difference among either female or male strains. Autoantigen array data were normalized as previously described [50].

Figure 2: Tlr7 expression is enhanced in B cells from NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice, and Tlr9-deficient splenocytes are hyperresponsive to Tlr7 agonism.

(A) Cervical LNs and (B) spleens were harvested from NOD.B10 (n = 20 females and 18 males), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 10 females and 9 males) and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 8 females and 9 males) strains and flow cytometry was performed to assess B cell (B220+) Tlr7 expression. (C) Splenocytes from NOD.B10 (n = 7) and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females (n = 9) were cultured in media alone or with Imq (31.3 μg/mL). Supernatants were collected, and IL-6 secretion was evaluated by ELISA. Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 3: Ablation of Tlr9 worsens lacrimal gland inflammation in males that is attenuated in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice.

(A and C) SMG tissue was harvested from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 17 and 22, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 8 and 10, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 10 and 12, respectively) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 7 and 10, respectively) mice and inflammation was quantified. (B and E) Lacrimal tissue was collected from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 9 and 15, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 10 and 7, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 10 and 14, respectively) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 8 and 11, respectively) mice and dacryoadenitis was quantified. (D) Stimulated saliva was collected from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 21 of each sex), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 12 of each sex), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 9 of each sex) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 11 and 15, respectively) mice and quantified. Yellow dashed lines indicate areas of lymphocytic infiltration. Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

For each ANA-specific IgM or IgG in the array data we identified autoantibodies that were differentially enriched between the 3 strains of each sex (NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/−, NOD.B10Tlr-DKO) via analysis of variance (ANOVA). We also used two-sided two-sample t-tests to compare ANA-specific autoantibody expression in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− or NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females with their strain-matched male counterparts. For each comparison we used the p. adjust R function in the R Stats package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, version 4.3.1) to adjust the P values in order to control the false discovery rate (FDR) across the ANA-specific autoantigens at 0.05 using the method proposed by Benjamini and Hochberg [61].

2.11. Data availability.

The autoantigen array data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the following accession number: GSE292271.

3.0. Results

3.1. Validation of NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice.

To examine the role of Tlr9 in pSD in a comprehensive manner, we generated NOD.B10 mice that lacked Tlr9 expression systemically, termed NOD.B10Tlr9−/−. Since previous studies by our group and others demonstrated an important role for TLR7 in pSD pathogenesis and Tlr9 restrains Tlr7 signaling [36, 38, 48–52, 62–65], we also generated pSD mice that lacked systemic expression of both Tlr7 and Tlr9, termed NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (Figure 1A). We first used flow cytometry to assess relative Tlr9 expression in splenic B cells derived from females and male NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9+/− mice (Figure 1B). We calculated the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each strain and found that Tlr9 expression was decreased in both female and male NOD.B10Tlr9+/− mice as compared to the sex-matched parental strains (p = 0.004 for each sex). We next verified that NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice lacked Tlr9 and that the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strain lacked Tlr7 and Tlr9 at both the gene and protein levels by qRT-PCR and flow cytometry using splenic tissue (Figure 1C – F). We also performed functional studies to confirm loss of Tlr9-mediated signaling in the knockout animals (Figure 1G and H). Splenocytes were harvested from NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice and were cultured with media alone or with the Tlr9 agonist CpG-B. Tlr7 and Tlr4 agonists, Imq and LPS, respectively, were used as positive controls. Splenocytes from the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals were cultured similarly. For all strains, cultured cells were harvested, and flow cytometry was performed to assess B cell CD69 expression. B cells from the NOD.B10 mice upregulated CD69 in response to stimulation with Imq, CpG-B, and LPS. Splenocytes from the Tlr9-deficient pSD mice also demonstrated robust activation following Tlr4 agonism but were unresponsive to CpG-B treatment as expected. Additionally, splenocytes from the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals showed strong responses to LPS but showed no evidence of activation following stimulation with either Imq or CpG-B. Altogether, these data confirm the successful ablation of Tlr9 and both Tlr7 and Tlr9 in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice, respectively.

Figure 1: Validation of NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice.

(A) Diagram showing the generation of NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strains. (B) Spleens were harvested from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 8 and n = 10, respectively) and NOD.B10Tlr9+/− mice (n = 8 and n = 9, respectively), flow cytometry was performed and B cell Tlr9 expression was calculated using MFI. Spleens were harvested from female and male NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice, and (C) qRT-PCR for Tlr9 was performed (n = 3 of each strain). (D) B cell Tlr9 expression was evaluated by flow cytometry (n = at least 8 of each sex and strain). Spleens were isolated from NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice, and (E) qRT-PCR for Tlr7 and Tlr9 was performed (n = 3 of each strain). (F) B cell Tlr7 and Tlr9 expression was evaluated by flow cytometry (n = at least 8 of each sex and strain). A histogram plot of one representative animal from each strain is shown. IC = Isotype Control. (G) Spleens were harvested from NOD.B10 (n = 16), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = at least 6) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 10) mice and cells were cultured in media alone, Imq (62.5 μg/mL), CpG-B (62.5 μM), or LPS (25 μg/mL) overnight as indicated. Cells were harvested and flow cytometry was performed to assess B cell CD69 expression (B220+ CD69+). (H) B cell CD69 expression is shown in histogram plots. One representative animal from each strain is shown. Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (**p < 0.01).

3.2. Tlr7 expression is enhanced in B cells from NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females and Tlr9-deficient splenocytes are hyperresponsive to Tlr7 agonism.

We next sought to determine if Tlr7 expression and signaling were altered in Tlr9-deficient pSD females. We harvested cLNs and spleens from NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females and males and performed flow cytometry to examine Tlr7-expressing B cells. Our data revealed that NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females and males had a higher percentage of B cells that expressed Tlr7 in cLNs (p = 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively) (Figure 2A). Moreover, Tlr7-expressing B cells were increased in the spleens derived from Tlr9-deficient females (p = 0.003), but no changes were noted in spleens from males (Figure 2B). To assess whether these results carried functional significance, we performed assays to determine if splenocytes from NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females were hyperresponsive to Tlr7 agonism. Cells were cultured overnight with a low dose of Imq (0.313 μg/mL). Supernatants were harvested, and IL-6 secretion was quantified. Our results revealed that IL-6 secretion was enhanced in the splenocyte cultures derived from Tlr9-deficient pSD females as compared to those from the Tlr9-sufficient controls (p = 0.04) (Figure 2C). We performed additional analyses to determine whether IFNα secretion was also enhanced following Tlr7 agonism of NOD.B10Tlr9−/− splenocytes derived from females. We found that while Imq induced robust IFNα production in both NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− splenocytes, there were no differences between the strains (Supplemental Figure 1). Altogether, our results established that Tlr7 expression and sensitivity is enhanced in splenocytes derived from Tlr9-deficient pSD females.

3.3. SMG inflammation is independent of Tlr9 expression, but ablation of Tlr9 exacerbates lacrimal gland disease in males that is ameliorated in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice.

We next examined exocrine gland inflammation and function in NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9+/−, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males and females. We found that in both sexes, ablation of Tlr9 had no effect on the amount of inflammation present in the SMG tissues (Figure 3A and C). We then assessed stimulated saliva production and found that there were no differences in saliva secretion in any of the strains examined in females (Figure 3D). Males that lacked Tlr9 expression also produced similar levels of saliva as compared to sex-matched pSD controls, although NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males produced less saliva as compared to their NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9+/− counterparts (p = 0.0006 and p = 0.02, respectively) (Figure 3D). Of note, we also examined the weight of each strain in males and females. We found that NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females were heavier than their NOD.B10Tlr9+/− counterparts (p = 0.02), although there were no differences among the male strains (Supplemental Figure 2).

Additionally, we quantified the area of inflammation in the lacrimal tissue. We found that Tlr9 ablation did not alter dacryoadenitis in females. Males, however, had enhanced inflammation in lacrimal gland tissue in the absence of Tlr9 (p = 0.0002). Moreover, NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males had reduced dacryoadenitis as compared to both the NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− strains (p = 0.008 and p < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 3B and E). Thus, our data revealed that while sialadenitis is independent of Tlr9, Tlr9 expression restrains lacrimal gland inflammation in a Tlr7-dependent manner in males.

3.4. Nephritis is diminished while lung inflammation is enhanced in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females.

We then performed experiments to examine nephritis in mice lacking Tlr9 alone or Tlr7 and Tlr9 in combination. Our data revealed that kidney inflammation was increased in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 mice (p = 0.03) (Figure 4A and C). When we examined NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females, however, we noted that nephritis was similar to that observed in the NOD.B10 mice, although nephritis was enhanced in both NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females and compared to sex-matched NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (p = 0.007 and p = 0.002, respectively). In males, kidney inflammation was negligible in all strains examined (Figure 4A and C). These data demonstrate that in pSD females, kidney inflammation is enhanced in Tlr9-deficient mice, and this requires expression of Tlr7.

Figure 4: Nephritis is enhanced in Tlr9-deficient pSD females in a Tlr7-dependent manner, while NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females exhibit heightened pulmonary inflammation.

(A) Kidneys were harvested from NOD.B10 mice (n = 18 of each sex), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 11 females and 8 males), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 9 females and 13 males) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 9 females and 11 males) and tissue inflammation was quantified. (B) Lungs were collected from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 17 and 25, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 11 and 8, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 9 and 13, respectively) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 9 and 10, respectively) mice and tissue inflammation was quantified. Yellow dashed lines indicate areas of lymphocytic infiltration. Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

We next quantified pulmonary inflammation in each strain. In contrast to our findings in the kidney, we found that there was no difference in lung inflammation in either NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to their NOD.B10 counterparts, and females lacking both Tlr7 and Tlr9 expression had heightened pulmonary inflammation (p = 0.03) (Figure 4B and D). In contrast, levels of pulmonary inflammation were similar among the male strains (Figure 4B and D). Of note, we also assessed the pancreatic tissue of each strain. Consistent with a previously published report [53], we observed negligible lymphocytic infiltration in all strains examined, and this finding was consistent in both females and males (Supplemental Figure 3). Taken together, these findings reveal that nephritis in females is dependent on Tlr7, while ablation of both Tlr7 and Tlr9 exacerbates pulmonary inflammation in pSD in a sex-biased manner.

3.5. Ablation of Tlr9 activates adaptive immunity in a sex-biased manner that is diminished in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice.

We next sought to evaluate immune populations in secondary lymphoid organs from each of the strains. We performed flow cytometry on both spleens and cLNs, and gating strategies employed are shown in Supplemental Figure 4. We first examined the spleens and found that the percentage of total B cells was increased in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females as compared to their NOD.B10 counterparts (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.04) (Figure 5A). Additionally, the percentage of total B cells was expanded in Tlr9-deficient females as compared to the heterozygous strain (p = 0.009) (Figure 5A). Of, note, no changes in total B cells were observed among the male strains (Figure 5A). We next examined splenic follicular (Fo) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells. We found no differences in the percentage of Fo B cells in any of strains in either females or males (Supplemental Figure 5A). When we examined MZ B cells, we found that Tlr9-deficient females had a reduced proportion of this subset as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (p = 0.04), although no changes were noted in males (Supplemental Figure 5B).

Figure 5: Ablation of Tlr9 activates adaptive immunity in a sex-biased manner that is diminished in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice.

Spleens were harvested female and male NOD.B10 (n = 20 and 17, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 13 and n = 9, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 10 and 9, respectively) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 9 and 9, respectively) strains and flow cytometry was performed to assess the percentage of (A) total B cells (B220+), (B) GC B cells (B220+, Fas+, GL-7+) (C) CD11c+ ABCs (B220+, CD23−, CD21−, CD11C+), (D) CD11b+ CD11c+ ABCs (B220+, CD23−, CD21−, CD11b+, CD11c+), (E) plasmablasts (B220+, CD138+), (F) total CD4+ T cells, (G) activated/memory CD4+ T cells (CD4+, CD44+, CD62Llo/−), and (H) Tfh cells (CD4+ TCRβ+ CXCR5+ PD1+). For the Tfh studies, spleens from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 7 and 5, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 9 and n = 5, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 8 and 8, respectively) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strains (n = 8 and 7, respectively) were assayed. (I) Total CD8+ T cells and (J) activated/memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+, CD44+, CD62Llo/−) were examined. Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

We next examined germinal center (GC) B cells. We found that this population was expanded in Tlr9-deficient females as compared to their NOD.B10 counterparts (p = 0.01) (Figure 5B). Moreover, GC B cells were diminished in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females as compared to both NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice (p = 0.005 and p < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 5B), while no differences were observed among the male strains. We next focused on CD11c+ and CD11b+CD11c+ ABCs and found that these populations were expanded in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to the parental strain (p = 0.001 for each), and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females had a reduced percentage of these populations when compared to the Tlr9-deficient mice (p = 0.0001 for each ABC subset) (Figure 5C and D). We also observed that female Tlr9-deficient mice had an expansion of CD11b+CD11c+ ABCs as compared to NOD.B10Tlr9+/− females (p = 0.04). Of note, we saw no differences in either ABC subset when we examined the male strains (Figure 5C and D).

In contrast to our findings in the other B cell subsets, the percentage of splenic plasmablasts was decreased in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females (p = 0.04) and in both NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− males as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 animals (p = 0.05 and p = 0.002, respectively). In addition, males showed increased proportions of plasmablasts in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice as compared to sex-matched Tlr9-deficient animals (p = 0.009) (Figure 5E). Moreover, the percentages of plasmablasts in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males and females was similar to that observed in their sex-matched NOD.B10 counterparts, indicating that the decreases observed in the Tlr9-deficient mice were dependent on Tlr7 in both sexes (Figure 5E).

We then examined splenic T cell populations. We found no differences in the percentage of CD4+ T cells in females or males (Figure 5F). When we examined CD4+ activated/memory T cells, however, we found that this population was increased in Tlr9-deficient females, as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 (p < 0.0001), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (p = 0.02), and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (p = 0.02). Moreover, the percentage of activated/memory CD4+ T cells was similar between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females, indicating that the increase observed in the Tlr9-deficient mice was dependent on Tlr7 (Figure 5G).We next assessed this population in males and found that there was an increased proportion of CD4+ activated/memory T cells in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals as compared to their NOD.B10 counterparts (p = 0.04) (Figure 5G). Since we saw differences in GC B cells in the female strains, we examined T follicular (Tfh) cells. Our data revealed that the proportion of Tfh cells was increased in female NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 animals (p = 0.02). This expansion was dependent on Tlr7 expression, as the Tfh population was diminished in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females as compared to both NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− counterparts (p = 0.005 and p < 0.0001, respectively). We next examined the splenic Tfh population in the males and found no differences among any of the strains examined (Figure 5H).

Lastly, we examined CD8+ T cells in the spleen. The percentage of total CD8+ T cells was decreased in Tlr9-deficent females as compared to NOD.B10 (p = 0.001) and NOD.B10Tlr9+/−females (p = 0.02), while no changes were observed in males (Figure 5I). When we examined CD8+ activated/memory T cells, we found that this population was increased in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to both the NOD.B10 (p = 0.008) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (p = 0.006), and the percentage of this subset was similar between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females, indicating that Tlr7 expression was required for the increase observed in Tlr9-deficient mice (Figure 5J). Finally, we examined this subset in males and saw no differences among the strains (Figure 5J).

We next assessed select immune populations in cLNs in each of our strains. Similar to our observations in the spleen, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females had increased percentages of total B cells compared to NOD.B10 (p < 0.0001) and NOD.B10Tlr9+/− females (p = 0.04), and this increase was abrogated in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (Figure 6A). We also examined the percentages of GC B cells and plasmablasts in the cLNs, and no changes were seen in any of the strains in either sex (Supplemental Figure 5C and D, respectively). We then focused on T cell populations. We noted that the percentage of CD4+T cells was decreased in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to the NOD.B10 strain (p < 0.00001). When we examined this population in males, we observed that it was also decreased in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (p = 0.002) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strains (p = 0.0007) as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 counterparts (Figure 6B). We found, however, that NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females had an increased percentage of activated/memory CD4+ T cells, compared to both NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (p < 0.00001 and p = 0.03 and, respectively). The percentage of activated/memory CD4+ T cells in the cLNs were also increased in female NOD.B10Tlr9+/− mice as compared to the NOD.B10 parental strain (p = 0.008). In males, we found that activated/memory CD4+ T cells were expanded in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice as compared to the NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9+/− strains (p = 0.05 and p = 0.01, respectively) (Figure 6C), indicating that the expansion of this population was independent of Tlr9 and relied entirely on the loss of Tlr7 expression. We next assessed Tfh cells in the cLNs of the female strains. Our data revealed that the percentage of Tfh cells was increased in Tlr9-deficent NOD.B10 mice as compared to the parental strain (p = 0.03). In addition, there was a decrease in the proportion of Tfh cells in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females (p = 0.009). Similar to our findings in the spleen, there were no differences in the percentages of Tfh cells in the male strains (Figure 6D).

Figure 6: Alterations in cLN populations are similar to those observed in the spleen.

Cervical LNs were harvested from the same animals as described in Figure 5 and (A) total B cells (B220+), (B) total CD4+ cells, (C) activated/memory CD4+ T cells (CD4+, CD44+, CD62Llo/−), (D) Tfh cells (CD4+, TCRβ+ CXCR5+ PD1+ (E) total CD8+ T cells, (F) activated/memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+, CD44+, CD62Llo/−). Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

We then assessed total CD8+ T cells. We saw no differences in this population among the strains, with the exception of the Tlr9-deficient males, which showed a decreased proportion compared to NOD.B10Tlr9+/− males (p = 0.03) (Figure 6E). Finally, we evaluated CD8+ activated/memory T cells and found results similar to those observed for the corresponding subset of CD4+ T cells (Figure 6F). Specifically, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females had an increased percentage of this subset compared to NOD.B10 controls (p < 0.0001, respectively). Moreover, the percentage of this subset was similar between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. In males, we found no differences in activated/memory CD8+ T cells among the strains (Figure 6F). Altogether, these analyses revealed that Tlr9 ablation causes expansion of B and T cell subsets associated with disease in females, and that this expansion relies on the expression of Tlr7. In males, deletion of Tlr9 had negligible effects on the immune populations examined. Similar to our previous publication [52], males that lacked Tlr7 showed expansion of several subsets in both the spleen and cLNs, and this was independent of Tlr9 expression.

3.6. Tlr9 governs antibody production in a sex-biased manner and IgG production in pSD relies on dual expression of Tlr7 and Tlr9.

To assess the functional consequences of B and T cell expansion in the knockout strains, we harvested sera from each strain and performed ELISAs to quantity total IgM and IgG. Our data revealed that female Tlr9-deficient mice had increased IgM as compared to their NOD.B10 counterparts (p = 0.03), while IgM titers were decreased in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females compared to NOD.B10 mice (p = 0.02). Additionally, both NOD.B10Tlr9+/− and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females had elevated IgM as compared to their DKO counterparts (p = 0.0005 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Of note, IgM was also decreased in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males when compared to that from NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9+/− or NOD.B10Tlr9−/− animals (p = 0.003, p = 0.001, and p = 0.0006, respectively) (Figure 7A). We then examined IgG levels. While no differences were observed in the Tlr9-deficient females or males, we found that IgG production was almost completely abrogated in both females and males that lacked expression of Tlr7 and Tlr9, and these levels were diminished as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 (p = 0.0005 and p > 0.0001, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (p = 0.002 for both females and males), and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice (p > 0.0001 and p = 0.005, respectively) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7: Tlr9 governs total and autoreactive antibody production in a sex-biased manner.

(A) Sera were harvested from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 18 and n = 17, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 10 and n = 9, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 10 each) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 8 and n = 10, respectively) strains and total IgM was quantified (B) Sera were harvested from female and male NOD.B10 (n = 21 and n = 23, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9+/− (n = 10 and n = 11, respectively), NOD.B10Tlr9−/− (n = 10 each) and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO (n = 9 and n = 10, respectively) strains and total IgG was quantified by ELISA. Horizontal lines represent mean and SEM (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). HEp-2 staining was performed to assess autoreactive IgG using sera from (C) female and (D) male NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice. The ANA patterns observed for each strain are indicated in the accompanying pie charts.

We then performed HEp-2 staining to assess IgG autoreactivity. We found that sera derived from female NOD.B10 mice showed a variety of patterns, although 18% of the mice (n = 2/11) showed a homogenous pattern, while 36% had a speckled pattern (n = 4/11). Of these, 75% (3/4) showed a nuclear speckled pattern, while 25% (1/4) had a cytoplasmic speckled pattern. We next examined sera from Tlr9-deficient females. These data revealed that 91% of animals examined had a speckled pattern (n = 10/11), with 50% of the mice showing a nuclear pattern and the other 50% exhibiting a cytoplasmic speckled pattern (n = 5/10 each). We did not observe any fluorescence in the sera derived from the female NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females (n = 8) (Figure 7C). We also assessed sera from the male strains. Results from these analyses revealed similar findings as compared to the females, as NOD.B10 male sera showed both homogenous (n = 5/11) and nuclear speckled patterns (n = 2/11). NOD.B10Tlr9−/− male sera was predominately nuclear speckled (n = 6/8), while the majority of sera derived from NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals showed no autoreactivity (n = 7/8), sera from 1 male showed a cytoplasmic speckled pattern. (Figure 7D).

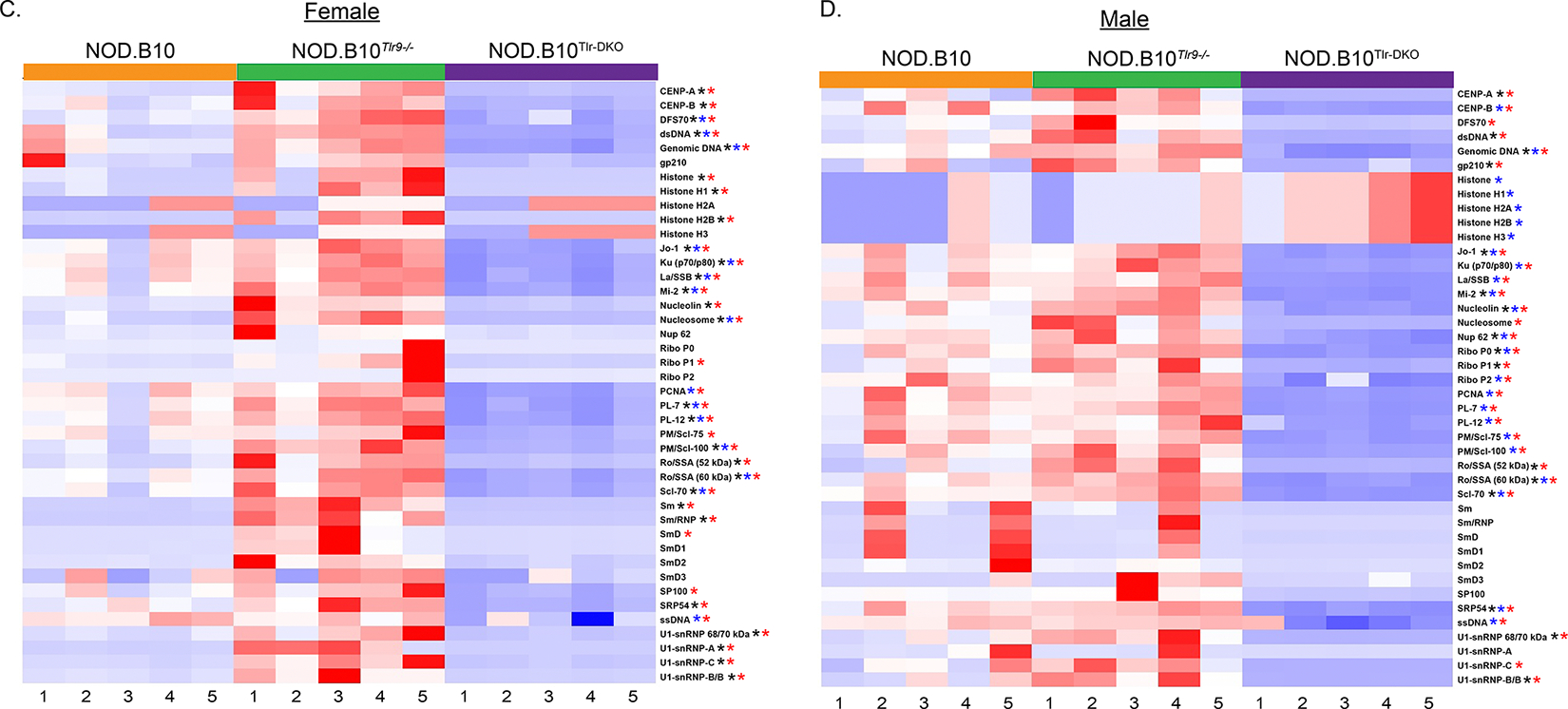

Autoantigen arrays were performed to confirm and extend the HEp-2 results. We focused our analyses on ANAs, as these antibodies are highly relevant to the human disease [66]. We performed several analyses on these data, and the p values for all comparisons are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. We first compared IgM autoantibodies among the NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. We found that 16 of 42 distinct ANAs (38%) were increased in Tlr9-deficient mice as compared to NOD.B10 animals (Figure 8A). Specifically, IgM antibodies directed against DSF70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, nucleosome, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (60 kDa), Sm, Sm/RNP, SmD, SmD2, SRP54, ssDNA, U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa, U1-snRNP-A, U1-snRNP-C, and U1-snRNP-B/B were elevated in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females.

Figure 8. Sera from NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice are enriched for ANAs in a Tlr7-dependent manner.

Sera were harvested female and male NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/−, and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strains (n = 5 each) and autoantigen arrays were performed to assess ANA-specific IgM in (A) females and (B) males and ANA-specific IgG in (C) females and (D) males. ANAs that are significantly different between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− sera are indicated by black asterisks, and blue asterisks indicate significant differences between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice. Red asterisks show significant differences between the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strains.

We next compared ANAs between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. In contrast, we found that 38% (n = 16/42) different ANAs were differentially enriched between the 2 strains as follows: DSF-70, ds-DNA, genomic DNA, gp210, Jo-1, La/SSB, PCNA, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSA (60 kDa), Scl-70, SmD2, ssDNA, and U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa. Finally, we compared ANA-specific IgM between the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. Our results revealed that 69% (n = 29/42) of the ANAs examined were enhanced in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice as compared the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strain. Specifically, CENP-B, DFS70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, gp210, Jo-1, Ku (p70/p80), La/SSB, nucleolin, nucleosome, ribophosphatases P0 and P1, PCNA, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSA (60 kDa), Scl-70, Sm, Sm/RNP, SmD, SmD2, SRP54, ssDNA, U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa, U1-snRNP-A, U1-snRNP-C, and U1-snRNP-B/B were enriched in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as compared to the double knockout animals.

We next focused our analyses on ANA-specific IgM in NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males (Figure 8B). When we compared sera from NOD.B10 males to their NOD.B10Tlr9−/− counterparts, we found that only 1 autoantigen, DSF70, was enriched in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− animals. We next compared IgM autoreactivity between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males. We found that DSF70, nucleolin, ribophosphatases P0 and P2, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSA (60 kDA), and U1-snRNP-B/B were enriched in NOD.B10 males compared to the double knockout animals, which represented 19% (n = 8/42) of the ANAs examined. Of note, 5 autoantibodies directed against different histone components (histone, histone H1, H2A, H2B, and H3) were elevated in sera from NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males as compared to the NOD.B10 strain. Finally, when we compared NOD.B10Tlr9−/− males to the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strain, we observed similar results as those described when we compared NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males. Additionally, autoantibodies directed against U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa were enriched in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− animals as compared to the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strain.

We then examined autoreactive IgG in the NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/−, and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females (Figure 8C). We first compared NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females as above. We found the sera from the Tlr9-deficient females was enriched in 64% (n = 27/42) of the ANAs as follows: CENP-A, CENP-B, DSF70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, histone, histones H1 and H2B, Jo-1, Ku (p70/p80), La/SSB, Mi-2, nucleolin, nucleosome, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSB (60 kDa), Scl-70, Sm, Sm/RNP, SRP54, U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa, U1-snRNP-A, U1-snRNP-C, and U1-snRNP-B/B. We next compared IgG-specific ANAs between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. We found that DSF70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, Jo-1, Ku (p70/p80), La/SSB, Mi-2, nucleosome, PCNA, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-75, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSB (60 kDa), Scl-70, and ssDNA were enriched in the NOD.B10 sera, representing 40% of the ANAs examined (n = 17/42). We then compared the ANAs between NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females. Most of the ANAs examined (79%, n = 33/42) were increased in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice as compared to the sex-matched NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals. Specifically, CENP-A, CENP-B, DSF70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, histone, histones H1 and H2B, Jo-1, Ku (p70/p80), La/SSB, Mi-2, nucleolin, nucleosome, Ribophosphatase P1, PCNA, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-75, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSB (60 kDa), Scl-70, Sm, Sm/RNP, SmD, SP100, SRP54, ssDNA, U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa, U1-snRNP-A, U1-snRNP-C, and U1-snRNP-B/B were enriched in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females compared to the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals.

Finally, we examined ANA-specific IgG in male NOD.B10, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice (Figure 8D). We first compared sera from NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice and found that 40% of the ANAs examined (n = 17/42) were enriched in NOD.B10 males. Specifically, CENP-A, dsDNA, genomic DNA, gp210, Jo-1, Mi-2, nucleolin, Nup-62, ribophosphatases P0 and P1, PL-7, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSA (60 kDa), Scl-70, SRP54, U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa, and U1-snRNP-B/B were enhanced in the NOD.B10 strain. We next compared ANAs between NOD.B10 and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice. We found that 45% (n = 19/42) of the ANAs were enriched in the NOD.B10 strain, while 5 were enhanced in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males, specifically histone and histones H1, H2A, H2B and H3. The following ANA-specific IgGs were enhanced in the NOD.B10 strain: CENP-B, genomic DNA, Jo-1, Ku (p70/p80), La/SSB, Mi-2, nucleolin, Nup 62, ribophosphatases P0 and P2, PCNA, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-75, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (60 kDa), Scl-70, SRP54, and ssDNA. Lastly, we compared ANAs between NOD.B10Tlr9−/− and NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males. Here, we noted that 69% of ANAs examined were elevated in the NOD.B10Tlr9−/− strain (n = 29/42), specifically CENP-A, CENP-B, DSF70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, gp210, Jo-1, Ku (p70/p80), La/SSB, Mi-2, nucleolin, nucleosome, Nup 62, ribophosphatases P0, P1 and P2, PCNA, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-75, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (52 kDa), Ro/SSA (60 kDa), Scl-70, SRP54, ssDNA, U1-snRNP 68/70 kDa, U1-snRNP-C, and U1-snRNP-B/B.

Lastly, we compared ANAs in Tlr9-deficient females to strain-matched males (Supplemental Figure 6 and Table 2). We first analyzed IgM and found that 17% (n = 7/42) of the ANAs examined were enriched in females as compared to males as follows: DFS70, dsDNA, genomic DNA, ssDNA, and U1-snRNP-C. Additionally, 38% of the ANA-specific IgGs examined (n = 16/42) were enriched in Tlr9-deficient females as compared to males as follows: gp210, Jo-1, La/SSB, Mi-2, nucleosome, PL-7, PL-12, PM/Scl-100, Ro/SSA (60 kDa), and Scl-70. Of note, there were no differences detected between sera from NOD.B10Tlr-DKO males and females for either ANA-specific IgM or IgG. Taken together, these data revealed that ablation of Tlr9 in both male and female pSD mice enhanced the production of ANAs in sera, and mice of both sexes that lacked expression of both Tlr7 and Tlr9 had significantly diminished ANAs.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of Tlr9 in pSD in a comprehensive manner and to determine which Tlr9-driven disease manifestations rely on Tlr7 expression. Our work revealed that splenocytes derived from NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females are hyperresponsive to Tlr7 agonism as compared to those from sex-matched NOD.B10 mice. Ablation of Tlr9 was pathogenic in pSD females but had a negligible effect on disease in males, with the notable exception of the lacrimal tissue. In females, ablation of Tlr9 resulted in enhanced Tlr7-dependent nephritis and expansion of both B and T cell subsets associated with disease. Our findings in males showed that Tlr9 expression exerts sex-biased effects, as deletion of Tlr7 caused enhanced disease that was primarily independent of Tlr9. Moreover, NOD.B10Tlr9−/− females and males displayed increased autoreactive IgM and IgG in sera, and ablation of both Tlr7 and Tlr9 dramatically reduced total and ANA-specific antibodies. Overall, these findings demonstrate the importance of endosomal Tlr activation in pSD pathogenesis and highlight the need for therapies that are tailored to address specific disease manifestations in accordance with patient sex.

Our study revealed an interesting sex-specific dichotomy in Tlr9-mediated inflammation in exocrine tissues, as sialadenitis was similar between Tlr9-deficient females and males, while ablation of Tlr9 resulted in robust dacryoadenitis in males but not females (Figure 3). Moreover, this inflammation was dependent on Tlr7 expression, as lacrimal inflammation in the NOD.B10 males was similar to that in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strain (Figure 3B and E). These results are intriguing because prior studies in our lab found no differences in dacryoadenitis when Myd88 was deleted systemically or when Myd88 was specifically ablated in either the stromal or hematopoietic compartments [16, 18]. Additionally, Tlr7-deficient pSD males showed no differences in lacrimal inflammation as compared to the NOD.B10 parental strain [52]. While the reasons for these seemingly disparate observations are unclear, it is possible that the absence of Tlr9 allows for enhanced Tlr7 signals, and that this heightened Tlr7 activation mediates inflammation [38, 67]. These findings are supported by studies in which LAMP3 overexpression in salivary tissue led to robust sialadenitis that was accompanied by upregulation of Tlr7 [62]. Significantly, when LAMP3 was overexpressed in Tlr7-deficient mice, this inflammation was attenuated [62]. In addition, studies by our group demonstrated that treatment of pre-disease pSD females with a Tlr7 agonist drove robust lacrimal inflammation [50]. Altogether, these data suggest that Tlr7 hyperactivation may drive lacrimal disease in pSD males, and further work is needed to examine this in greater depth.

Moreover, additional studies are needed to determine why the absence of Tlr9 caused robust lymphocytic infiltration in the lacrimal tissue of males but not females. One possible explanation for this is that there may be endogenous Tlr7-activating ligands in male lacrimal tissue that are absent in females. Since male NOD.B10 mice show greater dacryoadenitis than females (Figure 3 and [52]), there could be increased apoptotic debris or other endogenous activators of Tlr7 in the lacrimal tissue of males as compared to females [68]. As a corollary, these findings suggest that Tlr7 signaling is required to amplify ongoing inflammation but that activation of Tlr7 by endogenous ligands does not initiate dacryoadenitis in male pSD mice. Further studies are needed to examine these possibilities and to determine whether underlying genetic or hormonal differences between the sexes also contribute to the enhanced inflammation observed in males.

Of note, female kidney and lung tissue also showed sex-biased strain-specific differences. Indeed, ablation of Tlr9 in females led to heightened Tlr7-dependent nephritis. In contrast, lung inflammation was unchanged in NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice but was enhanced in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO females (Figure 4). These findings are consistent with our prior work, in which ablation of Myd88 in the hematopoietic compartment led to diminished nephritis but enhanced lung inflammation in females [18]. While we do not know the reasons for these dichotomous results, we have speculated previously that differences in the tissue microenvironments may lead to altered availability of specific Tlr ligands that modulate inflammation [18]. Indeed, DAMP-driven signaling networks in diverse tissue types may underlie the differences observed. DAMPs mediate activation of both pro-and anti-inflammatory pathways through ligation of diverse receptors that do not require Myd88, such as P2X7/P2X4 and STING [69–71]. Since these pathways are implicated in pSD [17, 19, 20, 72–81], tissue-specific DAMPs and differential expression of their cognate receptors and co-receptors may account for the disparate findings observed in kidney and lung, although further studies are needed to establish this conclusively. This paradigm also likely extends to salivary tissue as well, as ablation of Tlr7 or Tlr9 did not alter salivary inflammation in any of the female or male strains examined, suggesting that pathways independent of endosomal Tlrs may mediate sialadenitis in pSD.

It is important to point out that some of disease manifestations observed in NOD.B10Tlr9/- females were dependent on Tlr7, while others were not. Indeed, nephritis and expansion of immune populations seen in Tlr9-deficient females disease relied on the expression of Tlr7 (Figures 4 and 5). This was not the case, however, when we examined total and autoreactive antibody titers. Serum IgM levels were diminished in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice of both sexes as compared to sex-matched NOD.B10 mice (Figure 7). These findings were even more striking when we quantified IgG titers, as these were negligible in both female and male NOD.B10Tlr-DKO animals (Figure 7). These findings are also mirrored in the HEp-2 and autoantigen array data, as many ANA-specific IgM and IgG autoantibodies were significantly reduced in the DKO mice as compared their NOD.B10 counterparts (Figure 8).

Our HEp-2 findings in Tlr9−/− males and females were reminiscent of those in the lupus literature, as deletion of Tlr9 in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice resulted in increased antibodies that recognize RNA-associated antigens, as evidenced by diminished homogenous and enhanced speckled patterns [9, 35, 41, 42]. Our results are similar in that speckled patterns predominated in both male and female NOD.B10Tlr9−/− mice (Figure 7C and D) and corroborative autoantigen array data revealed that RNA-associated antibodies were enriched in the Tlr9-deficient mice of both sexes (Figure 8C and D). Moreover, many antibodies that recognize RNA-associated proteins were enhanced in Tlr9-deficient females as compared to strain-matched males, as Jo-1, La/SSB, PL-7, PL-12, Pm/Scl 100, and Ro/SSA (60 kDa) were enriched in female sera (Supplemental Figure 6). Thus, similar to findings in lupus models [40], ablation of Tlr9 resulted in loss of tolerance to RNA-associated autoantigens, and this skewing of the repertoire appears to be more profound in females than males.

Furthermore, these data demonstrated that ablation of both Tlr7 and Tlr9 resulted in attenuation of total and autoreactive antibody production in a synergistic manner. This seems to be a unique feature of pSD mice, as serum IgG levels in Tlr7/Tlr9 DKO lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice were similar to those of the parental strain [9]. This effect is not simply due to the loss of Myd88-dependent signaling, as is the case for lupus [9], as our prior studies showed that NOD.B10 females that lacked systemic expression of Myd88 showed an approximate two-fold reduction in IgM and IgG titers that were equivalent to levels seen in healthy control mice [16]. While further experiments are needed to establish the underlying reasons for this dramatic decrease in IgM and IgG levels in the NOD.B10Tlr-DKO strain, these findings highlight the importance of the combined role of Tlr7 and Tlr9 signaling in antibody production in pSD.

As a corollary to these findings, our data suggest that IgG antibodies do not mediate salivary hypofunction in the NOD.B10 strain, as both female and male NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice had negligible IgG levels in sera but were not protected from loss of flow (Figure 7B and 3D, respectively). This finding is surprising given a previous report that showed anti-muscarinic receptor autoantibodies of the IgG1 subclass mediate salivary hypofunction in the NOD.B10 strain [57]. While it is not clear why our results differ from the previous study, these data indicate that other factors besides IgG likely drive the loss of saliva production observed in the DKO strain. It is interesting to note the IgM repertoire was also altered significantly in female pSD mice in the absence of Tlr9 (Figure 8A). While the role of IgM autoantibodies in pSD are poorly understood, studies show that B-1 cells are a major source of serum IgM, and these cells undergo proliferation in response to Tlr9 agonism [82]. Moreover, B-1 cell derived IgM is highly self-reactive, and this IgM is thought to play a protective role in clearing self-derived moieties that could promote disease in a susceptible host [83, 84]. Of relevance to the current study, mice that could not signal through Unc93B1-dependent TLRs, such as Tlr7 and Tlr9, displayed diminished secretion of self-reactive IgM [85]. Thus, further studies are warranted to understand whether IgM is less protective in NOD.B10Tlr-DKO mice and if this may contribute to the loss of salivary flow in this strain.

Studies examining lupus models of disease demonstrate that B cell expression of Tlr7 and Tlr9 have profound effects on organ-specific disease, and some of these manifestations show sex-bias [41, 43]. Additional studies are needed to determine if B cell intrinsic Tlr7 and Tlr9 are critical modulators of pSD, and to establish the molecular mechanisms underlying the female sex-bias observed. Furthermore, studies are warranted to examine the way in which these Tlrs contribute to disease in other cell types, as innate immune cells and salivary epithelial cells express both Tlr7 and Tlr9 that is dysregulated in the context of pSD [21, 44–46, 64, 86–89]. This is a limitation of the current study, as it is possible that intrinsic activation of endosomal Tlrs in dendritic cells (DCs), in particular, may be a key driver of disease, as DC subsets express high levels of Tlr7 and Tlr9 [41, 43] and these cells are implicated in pSD pathogenesis [90–94]. While elegant studies in the lupus field using tissue-specific ablation of Tlr7 or Tlr9 suggest that B cell, rather than DC expression of these Tlrs is essential for disease [41, 43], it is possible that this is not the case for pSD. Thus, further studies are warranted to establish whether expression of endosomal Tlr in specific cell types drives distinct disease manifestations in pSD.

Such studies are critical because pSD is a heterogenous disease characterized by different molecular signatures and clinical phenotypes [95–97]. In addition, sex-biased genetic alterations are reported in pSD and disease severity differs between males and females [98–104]. Altogether, these studies highlight the importance of clinical trials that address this molecular and clinical heterogeneity and also identify sex-related differences that carry clinical relevance.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that endosomal Tlrs are critical for tissue-specific disease manifestations in pSD. Our work highlights the relevance of patient sex as a modifier of organ-specific disease. Additional studies are needed to assess endogenous ligands that mediate activation of these pathways in females and males and also to determine effective strategies for therapeutic modulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Dr. Andrew McCall for technical assistance. Instrumentation for this work was provided by the Optical Imaging and Analysis Facility at the University of Buffalo. The authors thank Dr. Achamaporn Punnanitinont for assistance with Aperio slide scanning. The authors are grateful to Dr. Nichol E. Holodick (Western Michigan University) for critical review of the manuscript. Funding for this work was provided by NIH/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) award R01DE29472 to JMK. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR001412 to the University at Buffalo. Finally, the Andor Dragonfly spinning disc confocal microscope was supported by the NIH S10 grant OD025204. This manuscript does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or NIDCR.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Mariette X and Criswell LA, Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2018. 379(1): p. 97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nocturne G, et al. , Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome Prevalence: What if Sjogren was Right After All? Comment on the Article by Maciel et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2018. 70(6): p. 951–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Negrini S, et al. , Sjogren’s syndrome: a systemic autoimmune disease. Clin Exp Med, 2022. 22(1): p. 9–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helmick CG, et al. , Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum, 2008. 58(1): p. 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youinou P, Saraux A, and Pers JO, B-lymphocytes govern the pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Pharm Biotechnol, 2012. 13(10): p. 2071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medzhitov R, et al. , MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Mol Cell, 1998. 2(2): p. 253–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, et al. , Toll-Like Receptors Gene Polymorphisms in Autoimmune Disease. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 672346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadanaga A, et al. , Protection against autoimmune nephritis in MyD88-deficient MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum, 2007. 56(5): p. 1618–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickerson KM, et al. , TLR9 regulates TLR7- and MyD88-dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. J Immunol, 2010. 184(4): p. 1840–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teichmann LL, et al. , Signals via the adaptor MyD88 in B cells and DCs make distinct and synergistic contributions to immune activation and tissue damage in lupus. Immunity, 2013. 38(3): p. 528–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leadbetter EA, et al. , Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature, 2002. 416(6881): p. 603–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua Z, et al. , Requirement for MyD88 signaling in B cells and dendritic cells for germinal center anti-nuclear antibody production in Lyn-deficient mice. J Immunol, 2014. 192(3): p. 875–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamagna C, et al. , Hyperactivated MyD88 signaling in dendritic cells, through specific deletion of Lyn kinase, causes severe autoimmunity and inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(35): p. E3311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Londe AC, et al. , Type I Interferons in Autoimmunity: Implications in Clinical Phenotypes and Treatment Response. J Rheumatol, 2023. 50(9): p. 1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PY, et al. , TLR7-dependent and FcgammaR-independent production of type I interferon in experimental mouse lupus. J Exp Med, 2008. 205(13): p. 2995–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiripolsky J, et al. , Myd88 is required for disease development in a primary Sjogren’s syndrome mouse model. J Leukoc Biol, 2017. 102(6): p. 1411–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiripolsky J, et al. , Activation of Myd88-Dependent TLRs Mediates Local and Systemic Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiripolsky J, et al. , Tissue-specific activation of Myd88-dependent pathways governs disease severity in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Autoimmun, 2021. 118: p. 102608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiripolsky J and Kramer JM, Current and Emerging Evidence for Toll-Like Receptor Activation in Sjogren’s Syndrome. J Immunol Res, 2018. 2018: p. 1246818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spachidou MP, et al. , Expression of functional Toll-like receptors by salivary gland epithelial cells: increased mRNA expression in cells derived from patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol, 2007. 147(3): p. 497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maria NI, et al. , Contrasting expression pattern of RNA-sensing receptors TLR7, RIG-I and MDA5 in interferon-positive and interferon-negative patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis, 2017. 76(4):721–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han JW, et al. , Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(11): p. 1234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YH and Song GG, Systemic lupus erythematosus and toll-like receptor 9 polymorphisms: A meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Lupus, 2023. 32(8): p. 964–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gies V, et al. , Impaired TLR9 responses in B cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. JCI Insight, 2018. 3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown GJ, et al. , TLR7 gain-of-function genetic variation causes human lupus. Nature, 2022. 605(7909): p. 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie C, et al. , De Novo PACSIN1 Gene Variant Found in Childhood Lupus and a Role for PACSIN1/TRAF4 Complex in Toll-like Receptor 7 Activation. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2023. 75(6): p. 1058–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen SR, et al. , Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity, 2006. 25(3): p. 417–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricker E, et al. , Altered function and differentiation of age-associated B cells contribute to the female bias in lupus mice. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robles-Vera I, et al. , Toll-like receptor 7-driven lupus autoimmunity induces hypertension and vascular alterations in mice. J Hypertens, 2020. 38(7): p. 1322–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elshikha AS, et al. , TLR7 Activation Accelerates Cardiovascular Pathology in a Mouse Model of Lupus. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 914468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenks SA, et al. , Distinct Effector B Cells Induced by Unregulated Toll-like Receptor 7 Contribute to Pathogenic Responses in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Immunity, 2020. 52(1): p. 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fillatreau S, Manfroi B, and Dorner T, Toll-like receptor signalling in B cells during systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2021. 17(2): p. 98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh ER, et al. , Dual signaling by innate and adaptive immune receptors is required for TLR7-induced B-cell-mediated autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(40): p. 16276–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soni C, et al. , B cell-intrinsic TLR7 signaling is essential for the development of spontaneous germinal centers. J Immunol, 2014. 193(9): p. 4400–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nickerson KM, et al. , Toll-like receptor 9 suppresses lupus disease in Fas-sufficient MRL Mice. PLoS One, 2017. 12(3): p. e0173471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossaller L, et al. , TLR9 Deficiency Leads to Accelerated Renal Disease and Myeloid Lineage Abnormalities in Pristane-Induced Murine Lupus. J Immunol, 2016. 197(4): p. 1044–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lartigue A, et al. , Role of TLR9 in anti-nucleosome and anti-DNA antibody production in lpr mutation-induced murine lupus. J Immunol, 2006. 177(2): p. 1349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nundel K, et al. , Cell-intrinsic expression of TLR9 in autoreactive B cells constrains BCR/TLR7-dependent responses. J Immunol, 2015. 194(6): p. 2504–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen SR and Shlomchik MJ, Regulation of lupus-related autoantibody production and clinical disease by Toll-like receptors. Semin Immunol, 2007. 19(1): p. 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Celhar T, et al. , Toll-Like Receptor 9 Deficiency Breaks Tolerance to RNA-Associated Antigens and Up-Regulates Toll-Like Receptor 7 Protein in Sle1 Mice. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2018. 70(10): p. 1597–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tilstra JS, et al. , B cell-intrinsic TLR9 expression is protective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest, 2020. 130(6): p. 3172–3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson SW, et al. , Opposing impact of B cell-intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 signals on autoantibody repertoire and systemic inflammation. J Immunol, 2014. 192(10): p. 4525–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cosgrove HA, et al. , B cell-intrinsic TLR7 expression drives severe lupus in TLR9-deficient mice. JCI Insight, 2023. 8(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimizu T, et al. , Activation of Toll-like receptor 7 signaling in labial salivary glands of primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Clin Exp Immunol, 2019. 196(1): p. 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng L, et al. , Expression of Toll-like receptors 7, 8, and 9 in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 2010. 109(6): p. 844–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang H, et al. , Elevated expression of Toll-like receptor 7 and its correlation with clinical features in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Adv Rheumatol, 2024. 64(1): p. 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlsen M, et al. , Expression of Toll-like receptors in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Scand J Immunol, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karlsen M, et al. , TLR-7 and −9 Stimulation of Peripheral Blood B Cells Indicate Altered TLR Signalling in Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome Patients by Increased Secretion of Cytokines. Scand J Immunol, 2015. 82(6): p. 523–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brauner S, et al. , H1N1 vaccination in Sjogren’s syndrome triggers polyclonal B cell activation and promotes autoantibody production. Ann Rheum Dis, 2017. 76(10): p. 1755–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Punnanitinont A, et al. , TLR7 agonism accelerates disease in a mouse model of primary Sjogren’s syndrome and drives expansion of T-bet(+) B cells. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 1034336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Punnanitinont A, et al. , TLR7 activation of age-associated B cells mediates disease in a mouse model of primary Sjogren’s disease. J Leukoc Biol, 2024. 115(3): p. 497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Punnanitinont A, et al. , Tlr7 drives sex- and tissue-dependent effects in Sjogren’s disease. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2024. 12: p. 1434269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robinson CP, et al. , A novel NOD-derived murine model of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum, 1998. 41(1): p. 150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kiripolsky J, et al. , Systemic manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome in the NOD.B10Sn-H2b/J mouse model. Clin Immunol, 2017. 183: p. 225–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malladi AS, et al. , Primary Sjogren’s syndrome as a systemic disease: a study of participants enrolled in an international Sjogren’s syndrome registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2012. 64(6): p. 911–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao J, et al. , Sjögren’s syndrome in the NOD mouse model is an interleukin-4 time-dependent, antibody isotype-specific autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun, 2006. 26(2): p. 90–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen CQ, et al. , IL-4-STAT6 signal transduction-dependent induction of the clinical phase of Sjögren’s syndrome-like disease of the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Immunol, 2007. 179(1): p. 382–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kramer JM, et al. , Analysis of IgM antibody production and repertoire in a mouse model of Sjogren’s syndrome. J Leukoc Biol, 2016. 99(2): p. 321–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andrade LEC, et al. , Reflecting on a decade of the international consensus on ANA patterns (ICAP): Accomplishments and challenges from the perspective of the 7th ICAP workshop. Autoimmun Rev, 2024. 23(9): p. 103608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://www.R-project.org/> [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, 1995. 57: p. 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamura H, et al. , Amplified Type I Interferon Response in Sjogren’s Disease via Ectopic Toll-Like Receptor 7 Expression in Salivary Gland Epithelial Cells Induced by Lysosome-Associated Membrane Protein 3. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2024. 76(7): p. 1109–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Debreceni IL, et al. , Toll-Like Receptor 7 Is Required for Lacrimal Gland Autoimmunity and Type 1 Diabetes Development in Male Nonobese Diabetic Mice. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y, et al. , TLR7 Signaling Drives the Development of Sjogren’s Syndrome. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 676010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Desnues B, et al. , TLR8 on dendritic cells and TLR9 on B cells restrain TLR7-mediated spontaneous autoimmunity in C57BL/6 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(4): p. 1497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fayyaz A, Kurien BT, and Scofield RH, Autoantibodies in Sjogren’s Syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am, 2016. 42(3): p. 419–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alexopoulou L, Nucleic acid-sensing toll-like receptors: Important players in Sjogren’s syndrome. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 980400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vinuesa CG, Grenov A, and Kassiotis G, Innate virus-sensing pathways in B cell systemic autoimmunity. Science, 2023. 380(6644): p. 478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeng-Brouwers J, et al. , Communications via the Small Leucine-rich Proteoglycans: Molecular Specificity in Inflammation and Autoimmune Diseases. J Histochem Cytochem, 2020: p. 22155420930303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Babelova A, et al. , Biglycan, a danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via toll-like and P2X receptors. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(36): p. 24035–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar V, A STING to inflammation and autoimmunity. J Leukoc Biol, 2019. 106(1): p. 171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu W, et al. , Rapamycin can alleviate the submandibular gland pathology of Sjogren’s syndrome by limiting the activation of cGAS-STING signaling pathway. Inflammopharmacology, 2024. 32(2): p. 1113–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu J, et al. , Lactate-induced mtDNA Accumulation Activates cGAS-STING Signaling and the Inflammatory Response in Sjogren’s Syndrome. Int J Med Sci, 2023. 20(10): p. 1256–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang M, et al. , Genomic DNA activates the AIM2 inflammasome and STING pathways to induce inflammation in lacrimal gland myoepithelial cells. Ocul Surf, 2023. 30: p. 263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huijser E, et al. , Hyperresponsive cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway in monocytes from primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2022. 61(8): p. 3491–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang KT, et al. , Dysregulated Ca(2+) signaling, fluid secretion, and mitochondrial function in a mouse model of early Sjogren’s disease. Elife, 2024. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]