Abstract

Background:

Recruitment is a necessary, yet challenging component to clinical trial implementation. Using intentional strategies to meet enrollment goals is important to ensure the recruited sample adequately reflects the intended study population. Outreach via electronic health record (EHR) patient portals is a promising strategy. While identifying potentially eligible individuals in the EHR is largely accepted as effective, little is known about the effectiveness of outreach via EHR compared to outreach via traditional electronic mail (email) communication given equivalent population identification strategies.

Methods:

This study was conducted using recruitment data from one of four study locations participating in the LEAP study, a multi-site, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial studying the long-term use of phentermine on weight loss and blood pressure. Between May 2023 and February 2024, 17,989 potentially trial-eligible participants identified using EHR data were randomized to either portal or email recruitment communications. Outreach success was measured at six milestones between starting the self-screener and study randomization. Recruitment rates overall and by demographic subpopulation are reported at each milestone as a percent of total invited and as a percent of previous milestone completers. Multivariate analysis considers the moderating effect of demographics on the relative impact of communication type.

Results:

Overall, 6.6% (n=1191) completed the self-screener and 0.5% (n=85) were randomized into the LEAP trial. Individuals randomized to patient portal communication were more likely to start the self-screener (Odds Ratio [OR]=2.4 [2.12, 2.73], p<0.0001) and complete the subsequent four steps, however there was no significant difference in the percent ultimately randomized into the study (OR=1.43 [0.93, 2.21], p=0.10). Moreover, when controlling for completion of the previous step, all subsequent milestone differences were no longer significant. Gender was the only significant moderating factor of all available participant characteristics, with women 2.92 ([2.48, 3.43], p<0.001) and men 1.72 ([1.41, 2.12], p<0.001) times more likely to respond to portal messages than email communications.

Conclusions:

Initial activation in study activities was higher in the patient portal group. Although this impact sustained itself across all but the final study milestone and resulted in absolute larger counts among those randomized to portal messages, there is no evidence that this choice will improve representation in biomedical research or the final study randomization rate overall. Therefore, these findings suggest using the portal strategy may lead to more effort without yield on interim steps by both the research team and the potential participants compared to email. Ultimately, the research team’s approach may depend on organizational context and study topic, as some topics do not lend themselves to the less secure nature of email communications.

Keywords: Recruitment, subjects’ participation, patient portal

Background

Recruitment into clinical trials, or the process of identifying and notifying potential participants of a research opportunity with the goal of enrolling them into a trial, is a necessary precursor to trial success.1–3 Inadequate recruitment can lead to trial failures and limit the subsequent knowledge derived from the trial. Thus, good scientific stewardship supports inquiry into optimization of recruitment methods. Use of electronic health records (EHRs) is promising, primarily for its ability to target those that have a high likelihood of study eligibility based on patient-specific data.4–8 Moreover, the evolution and adoption of EHR patient portals, secure online websites suitable for communicating private health information, enables their use as a communication tool alerting individuals of studies for which they may be eligible. While not universally adopted, patient portals are widely available across health care systems in the US and in many other countries throughout the world, especially in countries with national health care systems.9, 10 An estimated 40% of US adults accessed their portal in 202011 and frequency of both offers of and access to is increasing over time, more than doubling in the US between 2014 and 2022.12 This method may hold more promise than other electronic methods because unlike email, it is considered a secure mode of communication. This privacy allows for communicating personal health information.13

A body of evidence supports the effectiveness of patient portals for trial recruitment alone and/or in combination with other strategies.13–19 Importantly, and preempting claims that digital platforms could be difficult for groups with less digital experience, using patient portals has also been shown to be an effective recruiting strategy among older individuals.20 Less is known about the relative effectiveness of this approach compared to other strategies. Although there is some evidence that outreach via an EHR patient portal can be more effective than email or postal outreach,21 the evidence is mixed,22 subject to limitations that could confound findings,13, 23 and/or gathered via survey-only studies.23, 24 In survey data collection, email contact is largely considered a less expensive, albeit less effective, mode of outreach compared to postal contact or telephone outreach.25

Although electronic communication strategies for trial recruitment are hypothesized to appeal to populations historically underrepresented in biomedical research, there is less evidence to support this. With electronic methods, recruited individuals are less likely to be from populations underrepresented in biomedical research compared to more labor-intensive approaches such as physical mailings and telephone outreach.8, 23, 26 Although mounting evidence supports the use of EHR for sample identification, there is less evidence that it yields a sample large enough to justify wider adoption, particularly if the goal is to diversify the sample.8

The use of portals for recruitment has been shown to be acceptable to patients17, 27 with little evidence of an increase in complaints from this type of outreach.21, 28 Positive signs include patients reporting they believe research recruitment is a good use of patient portals and there is increased satisfaction with being a patient at the host institution when receiving recruitment messages via the portal.21 When a portal is used, there is increased perceived credibility of the request to participate, communicating to the recipient the study is indeed associated with a credible organization, from which they receive health care, and with whom they have an underlying relationship.27

Compared to email, there can be more resources needed for recruitment via portal messaging. These may include institutional leadership approval, programming, and in many cases reliance on centralized organizational infrastructure such as a centralized EHR team for whom research may not be an explicit priority; whereas other recruitment efforts can be implemented by a team more local to the research effort.19, 21 Given the promise of portal messaging for recruitment, there is a need for a greater understanding of its relative effectiveness compared to less resource-intensive, yet potentially less personal methods due to the less secure nature of direct email communication. Answering the call for more for randomized trials of recruitment approaches,23 we compare the relative effectiveness of two electronic recruitment strategies, patient portal and email, with respect to overall yield and participant diversity, within a large clinical trial.

Methods

Study setting

The Long-term Effectiveness of the Anti-obesity medication Phentermine (LEAP) trial provided a platform for a sub-study comparing electronic outreach strategies. LEAP is a multi-site, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing 24 mg/day phentermine to placebo over 24 months, with co-primary efficacy and safety outcomes of change in weight and blood pressure. Participants in both arms also participate in a digital lifestyle intervention (WW™) and meet with study staff for 11 visits over the 24 months. The study was approved by the central Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest and was pre-registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05176626). This sub-study was conducted at HealthPartners Institute in Minnesota, one of the four LEAP sites, where outreach via patient portal and email were both possible modes of communication.

Participants

Eligible patients for the LEAP trial included adults between the ages of 18 and 70 years who have a BMI of 27–29.9 kg/m2 with a weight-related comorbidity (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), or a BMI of 30–44.9 kg/m2, regardless of comorbidity status. Participants needed to have and agree to using a smartphone or other device with regular internet access, given the use of the online WW™ application. Exclusions are consistent with current package labeling of phentermine, including a history of cardiovascular disease, poorly-controlled blood pressure (>149/94 mm Hg), elevated heart rate (>110 beats per minute), history of any cardiac arrhythmia, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, concurrent use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors, pregnancy or breastfeeding, end-stage organ disease, or other baseline condition that may render weight loss or use of the study medication unsafe (e.g., active malignancy, stage 4 or higher chronic kidney disease). Further exclusions include people with weight loss of ≥5 kg in the past 6 months, a history of bariatric surgery, a prescription for any anti-obesity medication within the past 12 months, or a prescription for phentermine or a phentermine-containing drug in the past 2 years. For this sub-study, participants also were required to have an email address on file and an active patient portal account.

Procedure

LEAP study sites received a waiver of informed consent for the recruitment phase, where an eligible participant phenotype was created using EHR data. The patient phenotype accounted for weight, vital status, associated comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes or pre-diabetes), prescriptions for anti-obesity medications, and possible exclusion criteria (e.g., diagnoses of heart diseases or arrhythmias, hospitalizations). Patients were contacted via patient portal and/or email, depending on the health systems’ communication capabilities.

The sub-study was fielded between May 2023 and February 2024. Thirty-eight weekly batches of potentially eligible patients at one site were randomly selected, without replacement, from the full sample extracted from the EHR data repository using the EHR phenotype. Weekly sample sizes were selected to meet study recruitment goals and fluctuated based on available baseline appointment slots and response rates to the self-survey, ranging from 300 to 600 invitees per week. Patients were randomly selected from the population eligible based on EHR and randomized 1:1 to receive outreach communication via email or patient portal message using SAS version 9.4 statistical software. Within 7 days before outreach, a data programmer checked the outreach list to ensure patients were still alive and not on the research opt-out list for the health system. A single message was sent to each potential participant and was sent at the same time and day each week.

For the sub-study, invitations were developed to mirror each other across the two delivery platforms, containing the same information about the study, including the goal, general requirements, basic eligibility criteria, and incentive information. Interested patients were able to click on a link to a self-screener housed in REDCap29, 30 that had a link to a video about the study and questions to ascertain preliminary eligibility. The links were individualized to the patient; therefore, the research team could track whether an invited participant completed the self-screener to determine eligibility.

Outcomes

LEAP recruitment milestones were used as the outcomes for this sub study. Binary variables were created to determine whether a potential participant passed the following milestones:

Self-screener completion. Participants who completed the self-screener form online, regardless of eligibility. Both eligible and ineligible patients who completed this task were included as completed.

Phone-screener completion. Patients eligible after completing the self-screener were asked to provide contact information and the best time to outreach. Study staff called self-screened eligible patients up to three times to conduct a phone screening visit, which took approximately 15–20 minutes to complete. Patients who completed this task, regardless of eligibility, were included as completed.

Consent completion. Immediately after completing the phone screener, eligible patients were asked if they were interested and would like to continue with the study. If so, participants could immediately complete a phone consent and digital consent process, where a study team member would email the consent form to participants as they reviewed the content with them. Participants were able to ask questions about the trial, and if interested, signed the digital consent form. Participants who did not have time to complete this step after finishing the phone screener could make an appointment to complete the consent process later. Participants who consented for the study were marked as completed at this step.

Behavioral run-in completion. After consent, participants enter a behavioral run-in period to confirm they can successfully download the WW™ app and complete online surveys using the REDCap platform. Participants were emailed daily self-monitoring surveys via REDCap and asked to complete 5 surveys within a 14-day period. Participants who successfully passed this step were marked as complete.

Baseline session completion. After successfully completing run-in, a study team member conducted an EHR chart review to ensure that patients would likely be eligible for the trial. If they passed the medical record review, participants were contacted by phone and scheduled for an in-person baseline session to conduct final eligibility testing and collect baseline data. Participants who completed this step, regardless of eligibility for randomization, were marked as completed.

Randomization. Patients who were eligible from the baseline session and still interested in participating in the trial were scheduled for a randomization visit, where they were assigned to a study arm (blinded) and given their first study drug prescription. They also started the WW™ intervention and met with the study clinician to get instructions for moving forward. This step was the most important step for the research team, as only randomized participants counted towards the study recruitment goal. Participants who were randomized into the trial were counted as completed in this step.

In addition to these recruitment milestones, we captured additional data of interest:

Patient characteristics.

Demographic and clinical characteristics available in the EHR at the time of the EHR data extraction were used as covariates to determine whether the recruitment modes produced equal response rates across groups. Specifically, age (grouped into 4 groups:18–29 years, 30–44 years, 45–59 years, and 60+ years), gender (male, female, or other), race (Asian, Black or African American, White, Multiple or Other Race [which included people who identified as American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or some other not-specified racial group], or Unknown Race), ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino, Not Hispanic or Latino, or Unknown Ethnicity), and BMI category (overweight [BMI 27.0 – 29.9], obesity class I [BMI 30.0–34.9], obesity class II [BMI 35.0–39.9], or obesity class III [BMI 40.0–44.9]).

Time to completion.

The number of days between invitation send and completing the self-screening was documented and compared between groups.

Documentation of unsolicited feedback.

Patients who reached out to the research team after receiving an outreach message and shared positive or negative feedback related to the recruitment process via phone or email were documented in the study database. Frequency of unsolicited negative feedback was counted across both recruitment modes and themes are reported.

Analysis and power

Data were stored in REDCap, an online data management software, and analyzed using SAS 9.4. Data were pre-screened for missingness and to ensure all values were within expected ranges. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables) were used to describe the sample and the unadjusted rates of recruitment milestone completion overall and by recruitment mode. Logistic regression analyses, with recruitment modes as the independent variable and each recruitment milestone completion status (1 = yes, 0 = no), were used to determine whether recruitment mode was significantly associated with each recruitment milestone. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to compare the likelihood of completion by patient portal invitation to the likelihood of completion by email invitation. The primary analysis included mode as the only independent variable. In secondary analyses, we limited the analyses to participants who successfully passed the prior recruitment milestone (e.g., only participants who were eligible after self-screener were included in the analysis for phone screener completion). Finally, in exploratory analyses, we examined whether demographic and clinical characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, gender, and BMI category) significantly moderated the effect of recruitment mode on completing the self-screener by adding a main effect for the participant characteristic and an interaction term for mode by participant characteristic to the logistic regression models used for the primary analysis.

A priori power analyses were conducted for the sub-study to determine whether there was superiority of one recruitment mode over the other on completing the self-screener (highest completion rate) and being randomized into the trial (lowest completion rate). For self-screener completion, a power analysis estimating the 95% power to detect a difference of 2%, with a base completion rate of 10% in the patient portal group, an alpha of 0.05, and a two-tailed test estimated that a sample size of 12,712 messages was needed. A second power analysis testing the difference in randomization rate suggested that with 95% power, a randomization difference of 1% in each arm, a base randomization rate of 1% in the patient portal group, alpha = 0.05, and a two-tailed test, 7668 invitations would be needed to detect a significant difference between the groups. Therefore, this sub-study had adequate power to detect small differences in completion rates across the arms and recruitment milestones.

Results

Population

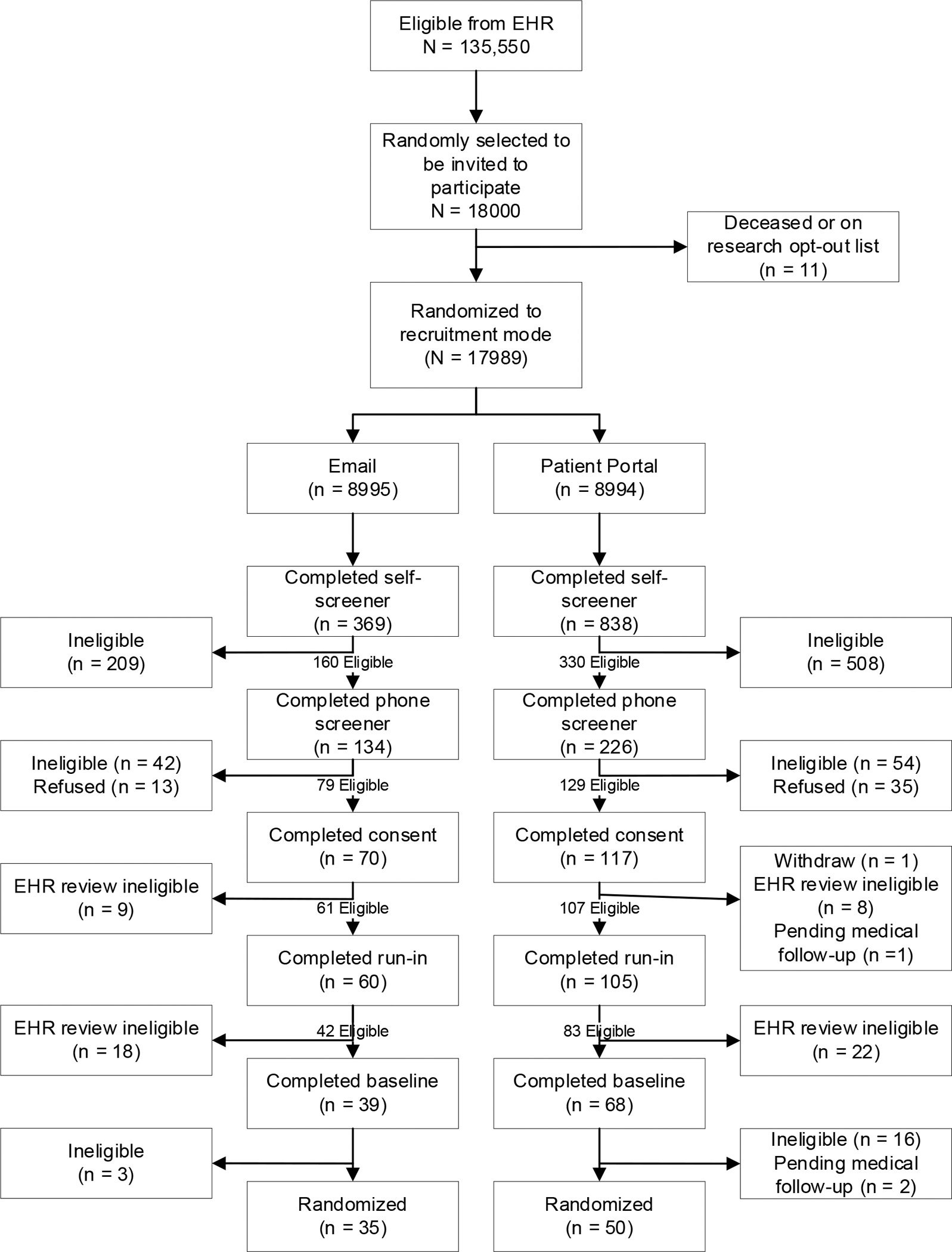

Over the study period, 17,989 individuals with EHR-indicated eligibility were randomized to email (n=8995) or patient portal (n=8994) communication (see Figure 1). Sample characteristics did not differ significantly between arms, with respect to sex, race/ethnicity or BMI category with 52.5% female, 3.1% Hispanic/Latino, 4.5% Asian, 13.0% Black or African American, 75.2% White, 21.9% overweight, and 47.1, 21.9 and 9.1% Obesity Class I, II, and III, respectively. Although mean age of 47.8 years old did not differ between arms, there were more of the youngest age group in the email compared to the patient portal arm (10.9% compared to 9.8%, p=0.013). (See Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart

Table 1.

Outreach Sample Characteristics from EHR, All and by Group Assignment

| Recruitment Method |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 17989) | Email (n = 8995) | Patient Portal (n = 8994) | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Sample Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|

| ||||||

| Age (M, SD) | 47.8 | 13.4 | 47.7 | 13.5 | 47.8 | 13.2 |

| 18–29 | 1864 | 10.4 | 980 | 10.9 | 884 | 9.8 |

| 30–44 | 5791 | 32.2 | 2882 | 32.0 | 2909 | 32.3 |

| 45–59 | 5816 | 32.3 | 2831 | 31.5 | 2985 | 33.2 |

| 60+ | 4518 | 25.1 | 2302 | 25.6 | 2216 | 24.6 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 8542 | 47.5 | 4294 | 47.7 | 4248 | 47.2 |

| Female | 9442 | 52.5 | 4699 | 52.2 | 4743 | 52.7 |

| X or Unknown | 5 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.02 | 3 | 0.03 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 562 | 3.1 | 275 | 3.1 | 287 | 3.2 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 17185 | 95.5 | 8591 | 95.5 | 8594 | 95.6 |

| Unknown | 242 | 1.4 | 129 | 1.4 | 113 | 1.3 |

| Race | ||||||

| Asian | 805 | 4.5 | 399 | 4.4 | 406 | 4.5 |

| Black or African American | 2333 | 13.0 | 1140 | 12.7 | 1193 | 13.3 |

| White | 13523 | 75.2 | 6800 | 75.6 | 6723 | 74.8 |

| Multiple or Other Race | 574 | 3.2 | 276 | 3.1 | 298 | 3.3 |

| Unknown | 754 | 4.2 | 380 | 4.2 | 374 | 4.2 |

| BMI Category | ||||||

| Overweight (27.0–29.9) | 3939 | 21.9 | 2002 | 22.3 | 1937 | 21.5 |

| Obesity Class I (30.0–34.9) | 8474 | 47.1 | 4214 | 46.9 | 4260 | 47.4 |

| Obesity Class II (35.0–39.9) | 3933 | 21.9 | 1943 | 21.6 | 1990 | 22.1 |

| Obesity Class III (40.0–44.9) | 1643 | 9.1 | 836 | 9.3 | 807 | 9.0 |

Outcomes

Overall, 1207 individuals (6.7%) completed the self-screener after message delivery. The completion rate was higher among those randomized to the portal compared to email communication (9.1% vs. 4.1%, OR=2.40, [2.12, 2.73], p<0.0001). At each recruitment milestone up to but not including study randomization, portal communications yielded higher completion rates. In total, portal communications resulted in 50 randomized compared to 35 after email communication (OR=1.43, [0.93, 2.21], p=0.10) (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Milestone Completion Rates by Recruitment Method

| Variable | Recruitment Method | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| All | Patient portal | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|

| |||||||||

| Self-screener | 1207 | 6.7 | 369 | 4.1 | 838 | 9.1 | 2.40 | 2.12, 2.73 | <.0001 |

| Phone-screener | 360 | 2.0 | 134 | 1.5 | 226 | 2.5 | 1.70 | 1.37, 212 | <.0001 |

| Consent | 187 | 1.0 | 70 | 0.8 | 117 | 1.3 | 1.68 | 1.25, 2.26 | .0006 |

| Run-in | 165 | 0.9 | 60 | 0.7 | 105 | 1.2 | 1.76 | 1.28, 2.42 | .0005 |

| Baseline | 107 | 0.6 | 39 | 0.4 | 68 | 0.8 | 1.75 | 1.18, 2.60 | .0055 |

| Randomization | 85 | 0.5 | 35 | 0.4 | 50 | 0.5 | 1.43 | 0.93, 2.21 | .10 |

Note. OR = Odds ratio; Compares likelihood of those who were outreached via patient portal to those outreached via email (reference group) for each recruitment milestone. CI = Confidence interval.

Women, people with higher BMIs, and people who are older were more likely to start the self-screener across modes. People who are Black (compared to White) were equally less likely across modes to start the self-screener. Hispanic ethnicity was not related to starting the self-screener. Sex was the only observed characteristic that significantly moderated the effect of recruitment mode on self-screener completion (See Table 3). Females were more than 2.92 times ([2.48, 3.43], p<0.001) more likely and men 1.72 times ([1.41, 2.12], p<0.001) more likely to respond to patient portal messages compared to email.

Table 3.

Moderation of Recruitment Method by Participant Characteristics on Self-Screener Completion

| Variable | Self-screener completion rates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| All | Patient portal | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|

| |||||||||

| All | 1191 | 6.6 | 369 | 4.1 | 822 | 9.1 | 2.40 | 2.12, 2.73 | |

| Age | .12 | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 77 | 4.1 | 32 | 3.3 | 46 | 5.2 | 1.62 | 1.03, 2.58 | |

| 30–44 | 388 | 6.7 | 119 | 4.1 | 275 | 9.5 | 2.42 | 1.94, 3.03 | |

| 45–59 | 400 | 6.9 | 127 | 4.5 | 279 | 9.4 | 2.20 | 1.77, 2.73 | |

| 60+ | 326 | 6.6 | 91 | 4.0 | 238 | 10.7 | 2.92 | 2.28, 3.75 | |

| Sex | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Male | 403 | 4.7 | 154 | 3.6 | 256 | 6.0 | 1.72 | 1.41, 2.12 | |

| Female | 788 | 8.4 | 215 | 4.6 | 582 | 12.3 | 2.92 | 2.48, 3.43 | |

| Race | .54 | ||||||||

| Asian | 35 | 4.4 | 12 | 3.0 | 23 | 5.7 | 1.94 | 0.95, 3.95 | |

| Black or African American | 117 | 5.0 | 28 | 2.5 | 91 | 7.6 | 3.28 | 2.13, 5.05 | |

| White | 961 | 7.1 | 306 | 4.5 | 666 | 9.9 | 2.33 | 2.03, 2.68 | |

| Multiple or Other Race | 34 | 5.9 | 11 | 4.0 | 24 | 8.1 | 2.11 | 1.01, 4.39 | |

| Unknown | 44 | 5.8 | 12 | 3.0 | 34 | 9.1 | 3.07 | 1.56, 6.02 | |

| Ethnicity | .53 | ||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 38 | 6.8 | 10 | 3.6 | 28 | 9.8 | 3.09 | 1.48, 6.46 | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1143 | 6.7 | 357 | 4.2 | 786 | 9.2 | 2.37 | 2.08, 2.69 | |

| Unknown | 10 | 4.1 | 2 | 0.5 | 8 | 7.1 | 4.84 | 1.01, 23.3 | |

| BMI Category | .58 | ||||||||

| Overweight (27.0–29.9) | 174 | 4.4 | 49 | 2.5 | 129 | 6.7 | 2.84 | 2.03, 3.98 | |

| Obesity Class I (30.0–34.9) | 524 | 6.2 | 167 | 4.0 | 363 | 8.5 | 2.26 | 1.87, 2.73 | |

| Obesity Class II (35.0–39.9) | 346 | 8.8 | 110 | 5.7 | 242 | 12.2 | 2.31 | 1.82, 2.92 | |

| Obesity Class III (40.0–44.9) | 147 | 9.0 | 43 | 5.1 | 104 | 12.9 | 2.73 | 1.89, 3.95 | |

Note. OR = Odds ratio, comparing patient portal to email (reference). CI = Confidence interval. P-value is for the interaction term (mode by participant characteristic) determining whether there are significant differences in the effect of recruitment mode on self-screener completion by participant characteristics.

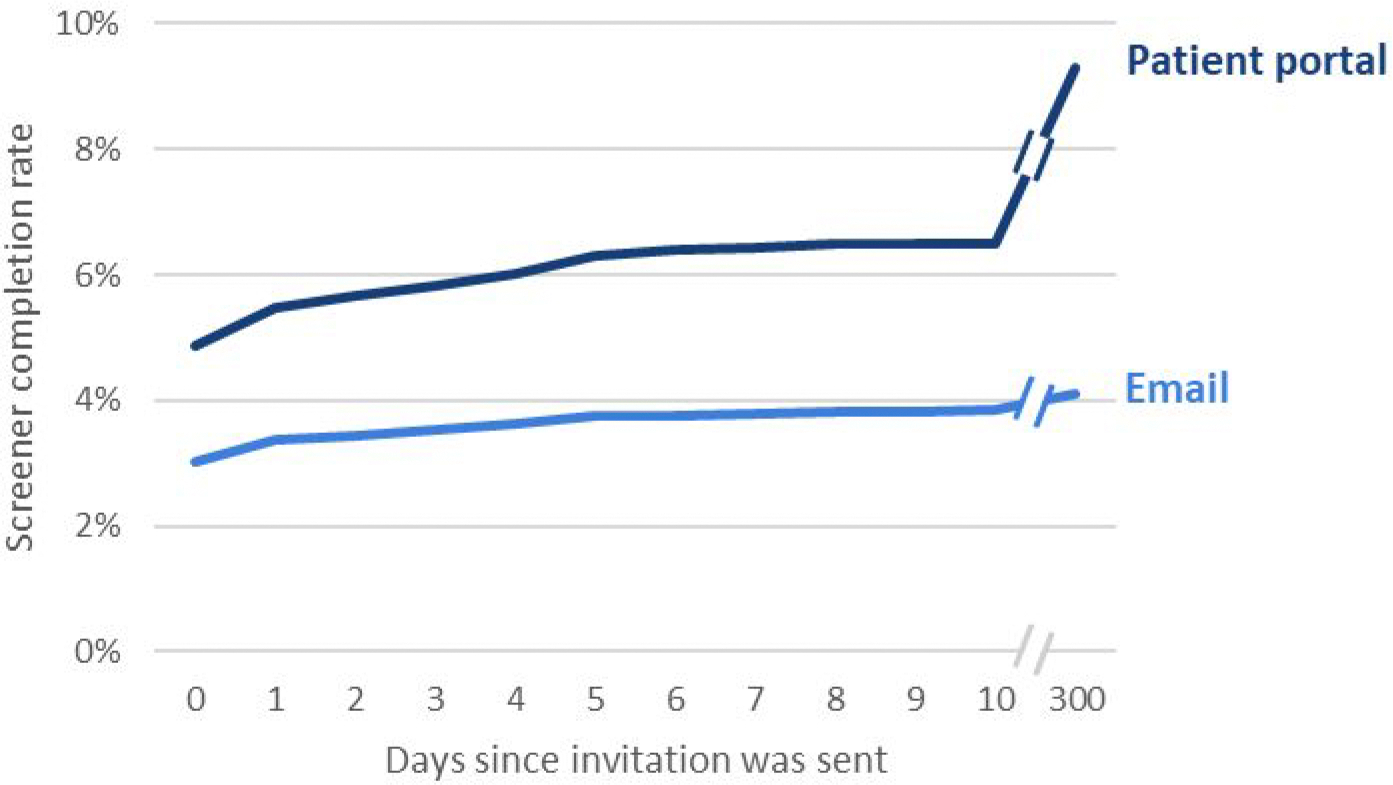

In the email invitation group, 3.0% completed the screener on the day of invitation. This contrasts with 4.9% among the portal group. Portal rates remained higher than email and had a longer tail with over 10% completing after 10 days in contrast to just over 4% completing after 10 days in the email group (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Screener completion rates over time and by mode

When considering only the pool of people who could complete a given milestone (i.e., those that successfully completed the prior milestone), there were few significant differences in completion rates across any subsequent milestone after starting the self-screener. When taken as a percentage of people that completed the self-screener, email communications yielded significantly higher rates of phone screener completion (83.8% compared to 68.5%, p=0.0004). There were no significant differences in the subsequent milestones of consent, run-in, baseline, or randomization completion rates (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Milestone Completion Rates by Recruitment Method, Only when eligible from prior step

| Variable | Recruitment Method | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| All | Patient portal | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|

| |||||||||

| Phone-screener | 360 | 73.5 | 134 | 83.8 | 226 | 68.5 | 0.42 | 0.26, 0.68 | .0004 |

| Consent | 187 | 87.8 | 70 | 88.6 | 117 | 87.3 | 0.89 | 0.37, 2.09 | .78 |

| Run-in | 165 | 88.2 | 60 | 85.7 | 105 | 89.7 | 1.46 | 0.60, 3.58 | .41 |

| Baseline | 107 | 88.4 | 39 | 95.1 | 68 | 85.0 | 0.29 | 0.06, 1.37 | .12 |

| Randomization | 85 | 98.8 | 35 | 97.2 | 50 | 100.0 | - | - | - |

Note. OR = Odds ratio, comparing patient portal to email (reference). CI = Confidence interval. Phone screener completion limited to self-screener eligible (n = 490). Consent completion limited to phone screener eligible (n = 213). Run-in completion limited to consent completion (n = 187). Baseline completion limited to run-in completion and EHR review eligible (n = 121). Randomization limited to baseline eligible (n = 86). Because of high rates of randomization completion among baseline-eligible participants, OR could not be meaningfully calculated (cells with n = 0).

Overall, there were no unsolicited positive comments documented about study outreach overall. Of 14 documented negative comments, 9 specifically referenced the invitation materials, calling the invitation for weight loss insulting or potentially triggering. Six of the negative comments were from the patient portal group and 3 negative comments from the email group. Of the 6 comments made from the patient portal group, 3 expressed concerns with being invited after a history of an eating disorder, not initially identified in EHR eligibility screening but added to the EHR phenotype midway through recruitment because of this feedback.

Discussion

Both invitation strategies benefited from the ability to identify patients that had a high likelihood of being eligible for the trial, yielding a 0.5% study enrollment rate. With respect to initial interest as reflected in completing a self-screener, patient portal communication was more effective than direct email. However, after that initial step, the return was largely equivalent. Because the patient portal is more closely tied to communication about health care from clinical teams, and clinicians are largely one of the most trusted sources for health information,31, 32 this initial differentiation could be in part explained. Further, there is more competition for attention in the crowded email landscape with most people in the United States receiving 100–120 emails a day.33

There is evidence that portal recruitment may be more effective for those already more likely to engage in research, potentially exacerbating underrepresentation in trials.34 However, we did not see differences between the two strategies in initial screening across race/ethnicity, age, or initial BMI status. As the effectiveness of the two approaches was largely equivalent, the efficiency, or the relative cost of implementing each should be considered when deciding which approach to use. A limitation to the current work is that relative costs of the two approaches were not captured and reported. Broadly, portal recruitment has been shown to be efficient, but this may depend on organizational context.18 With more uptake of the first step with portal outreach, more people were in the recruitment funnel and more fell out before study enrollment. This suggests unproductive time and resources of both the patients who initially screened eligible, and study team follow-up efforts that did not yield successful enrollment with portal communication. Moreover, portal communication had a longer impact, with people expressing interest many days or weeks after the initial invite, compared to most of those that responded to email invitations doing so on the initial day of invite. This suggests that the possible higher benefit of portal communications can be better realized for longer, ongoing study recruitment efforts.

There may be other reasons to choose one mode of communication over the other. Use of portal communications is necessarily restricted to environments with EHRs and patient portals. Moreover, local environments could hinder or promote the use of patient portals for research, and there is evidence that individuals who are men, are Hispanic, have less than a college degree, and have no internet are less likely to be offered access to a patient portal.35 Yet, there is evidence its use is consistent with patient expectations, with patients generally wanting information relevant to them and more information, rather than less and could enhance perceptions of a care delivery system’s relevance.17 More negative comments were volunteered from the patient portal group. The small number of individuals who made these comments shared specific health history information back to the study, suggesting more people in this group may have read the message and/or a difference in how people reacted to the invite, but it is difficult to draw inferences based on the small number of negative responses. Considerations for protecting personal health information may preclude the use of email for study communication, in that email is broadly not considered a secure form of communication. A weight loss study such as LEAP could easily be framed in email outreach in a way that did not disclose protected health information.

This study examined the research question in the context of a single weight loss study, which is potentially limiting with the possibility that other health topics could perform differently and be more or less suitable for one type of communication over another. Moreover, we were limited to a single integrated care delivery system with a regional geographical reach. Both outreach strategies required that the individual had an established relationship with the health care system. As such, the results do not extend beyond individuals with such a relationship or to health care systems that have not adopted EHRs with patient portals. Additional research should replicate these tests in other contexts and be coupled with future formative work to better understand patient preferences with respect to digital outreach for study recruitment. Also untested, and prime for future work, is the possibility those more closely connected to their health care clinicians are more frequent users of portals and more amenable to recruitment via this mechanism. If true, this could lead to selection bias that could unduly influence some study outcomes including protocol adherence.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jen Dinh for providing input on data visualization and Mallory Hall for assistance in preparing manuscript for submission to journal. The authors would also like to thank LEAP study participants.

Funding

The LEAP Study is supported by NHLBI grants UG3HL155801 and U24HL155802.

Footnotes

Trial Registration

References

- 1.Gul RB and Ali PA. Clinical trials: the challenge of recruitment and retention of participants. J Clin Nurs 2010; 19: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idnay B, Fang Y, Butler A, et al. Uncovering key clinical trial features influencing recruitment. J Clin Transl Sci 2023; 7: e199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzochi AT, Dennis M and Chun H-YY. Electronic informed consent: effects on enrolment, practical and economic benefits, challenges, and drawbacks—a systematic review of studies within randomized controlled trials. Trials 2023; 24: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Merriman EN, et al. Trials and tribulations of recruiting 2,000 older women onto a clinical trial investigating falls and fractures: Vital D study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009; 9: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thadani SR, Weng C, Bigger JT, et al. Electronic screening improves efficiency in clinical trial recruitment. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16: 869–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai YS and Afseth JD. A review of the impact of utilising electronic medical records for clinical research recruitment. Clin Trials 2019; 16: 194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmickl CN, Li M, Li G, et al. The accuracy and efficiency of electronic screening for recruitment into a clinical trial on COPD. Respir Med 2011; 105: 1501–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuh T, Srivastava T, Fiore D, et al. Using a patient portal as a recruitment tool to diversify the pool of participants in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. JAMIA Open 2022; 5: ooac091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tornero Costa R, Adib K, Salama N, et al. Electronic health records and data exchange in the WHO European region: A subregional analysis of achievements, challenges, and prospects. Int J Med Inform 2025; 194: 105687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO). Atlas of eHealth country profiles: the use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565219 (2016, accessed 14 April 2025).

- 11.Johnson C, Richwine C and Patel V. Individuals’ Access and Use of Patient Portals and Smartphone Health Apps, 2020. ONC Data Brief, no.57, https://www.healthit.gov/data/data-briefs/individuals-access-and-use-patient-portals-and-smartphone-health-apps-2020 (2021, accessed 14 April 2025).

- 12.Strawley C and Richwine C. Individuals’ Access and Use of Patient Portals and Smartphone Health Apps, 2022 [Data Brief: 69], https://www.healthit.gov/data/data-briefs/individuals-access-and-use-patient-portals-and-smartphone-health-apps-2022 (2023, accessed 14 April 2025). [PubMed]

- 13.Pfaff E, Lee A, Bradford R, et al. Recruiting for a pragmatic trial using the electronic health record and patient portal: successes and lessons learned. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26: 44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conley S, O’Connell M, Linsky S, et al. Evaluating recruitment strategies for a randomized clinical trial with heart failure patients. West J Nurs Res 2021; 43: 785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuggia M, Besana P and Glasspool D. Comparing semi-automatic systems for recruitment of patients to clinical trials. Int J Med Inform 2011; 80: 371–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khine H, Mathson A, Moshele PR, et al. Targeted electronic health record-based recruitment strategy to enhance COVID-19 vaccine response clinical research study enrollment. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2024; 37: 101250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller HN, Lindo S, Fish LJ, et al. Describing current use, barriers, and facilitators of patient portal messaging for research recruitment: Perspectives from study teams and patients at one institution. J Clin Transl Sci 2023; 7: e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samuels MH, Schuff R, Beninato P, et al. Effectiveness and cost of recruiting healthy volunteers for clinical research studies using an electronic patient portal: a randomized study. J Clin Transl Sci 2017; 1: 366–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman SE, Langford AT, Chodosh J, et al. Use of patient portals to support recruitment into clinical trials and health research studies: results from studies using MyChart at one academic institution. JAMIA Open 2022; 5: ooac092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plante TB, Gleason KT, Miller HN, et al. Recruitment of trial participants through electronic medical record patient portal messaging: a pilot study. Clin Trials 2020; 17: 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleason KT, Ford DE, Gumas D, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a patient portal messaging for research recruitment service. J Clin Transl Sci 2018; 2: 53–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snyder A Research Recruitment Study – MyChart Message Recruitment. Society of Clinical Research Associates (SOCRA), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heerman WJ, Jackson N, Roumie CL, et al. Recruitment methods for survey research: findings from the Mid-South Clinical Data Research Network. Contemp Clin Trials 2017; 62: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett WL, Bramante CT, Rothenberger SD, et al. Patient recruitment into a multicenter clinical cohort linking electronic health records from 5 health systems: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e24003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinclair M, O’Toole J, Malawaraarachchi M, et al. Comparison of response rates and cost-effectiveness for a community-based survey: postal, internet and telephone modes with generic or personalised recruitment approaches. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng MY, Olgin JE, Marcus GM, et al. Email-based recruitment into the Health eHeart Study: cohort analysis of invited eligible patients. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e51238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter KM, Kraft SA, Speight CD, et al. Research recruitment through the patient portal: perspectives of community focus groups in Seattle and Atlanta. JAMIA Open 2023; 6: ooad004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller HN, Charleston J, Wu B, et al. Use of electronic recruitment methods in a clinical trial of adults with gout. Clin Trials 2021; 18: 92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suran M and Bucher K. False health claims abound, but physicians are still the most trusted source for health information. JAMA 2024; 331: 1612–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swoboda CM, Van Hulle JM, McAlearney AS, et al. Odds of talking to healthcare providers as the initial source of healthcare information: updated cross-sectional results from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). BMC Fam Pract 2018; 19: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Radicati Group I. Email Statistics Report, 2018–2022. 2018.

- 34.Fiala MA. Patient portal recruitment may exacerbate underrepresentation in clinical trial participants. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023; 71: 2998–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anthony D, Campos-Castillo C and Nishii A. Patient-centered communication, disparities, and patient portals in the US, 2017–2022. Am J Manag Care 2024; 30: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]