Abstract

Difficulties with executive functioning are implicated in various forms of psychopathology. However, executive functioning task performance frequently demonstrates poor test-retest reliability, questionable convergent validity, and unstable associations with clinical measures. Model-based approaches may improve measurement by providing richer information about mechanisms underlying performance. The present study systematically compared a model-based measure of task-general executive functioning, Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation (EEA), with traditional summary metrics extracted from the same tasks in a longitudinal study of adolescents (N=637, age 7–19). EEA demonstrated reasonable stability across development and strong cross-task reliability. Reflecting traditional metrics, EEA related to self-reported effortful control and parent-reported attention, externalizing and total problems. EEA and one traditional metric (Go/No-Go Standard Deviation of Reaction Time) correlated with inhibition-related brain activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and the right superior temporal gyrus. These findings highlight the potential of EEA as a task-general, stable, biologically plausible measure of executive functioning in adolescents.

Keywords: computational, attention, externalizing, longitudinal, Go/No-Go, Stop-Signal

General Scientific Summary:

This study explores a novel approach to measuring executive functioning using computational modeling. We find that efficiency of evidence accumulation (EEA) is a reliable, task-general metric that relates to both mental health and brain activation patterns in adolescents. These findings highlight the potential for advanced modeling techniques to refine how executive functioning is assessed and understood.

Executive functioning in childhood is important for a wide range of outcomes across the lifespan, including academic success, mental and physical health, and wellness (see Robson et al., 2020 for a meta-analysis). Executive functioning is thought to be a set of top-down processes that involve regulation of behavior when automatic responding is not sufficient (Diamond, 2013), though there are many other terms often used to capture similar constructs (e.g. self-regulation, effortful control; Nigg, 2017). Difficulties with executive functioning have long been linked to various forms of psychopathology (e.g. Bloemen et al., 2018; Gotlib & Joormann, 2010; Moffitt, 2018; Smith et al., 2014; Verdejo-Garcia et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2014) to the extent that executive functioning has been proposed as a transdiagnostic target for intervention (Zelazo, 2020). Thus, understanding the factors underlying individual differences in executive functioning is critical for characterizing and predicting the development of psychopathology.

Challenges in the measurement of executive functioning

Studies of individual differences in executive functioning tend to assume that executive functioning is made up of several intercorrelated, but distinct, subcomponents (Karr et al., 2018; Sripada & Weigard, 2021). The most prominent theory of executive functioning, the unity-yet-diversity theory (Miyake et al., 2000), subdivides executive functioning into “shifting”, “updating”, and “inhibition” functions. A proliferation of tasks have thus been designed to capture individual performance within subcomponents of executive functioning (e.g. the go/no-go task measures “inhibition”; Packwood et al., 2011). These (putatively) subcomponent-specific tasks have been used extensively in clinical neuropsychology (Packwood et al., 2011) and in clinical neuroscience (e.g. Hull et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2013; Metin et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2014).

Despite this prominence of the unity-yet-diversity model, there is growing evidence that casts doubt on the model. A number of recent studies report conflicting findings regarding the structure of the subcomponents of executive functioning (Karr et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2013; McKenna et al., 2017; Packwood et al., 2011). Indeed, several studies suggest that almost all of the variance in individual and developmental differences in performance on tasks of executive functioning can instead be attributed to a single task-general factor (Loffler et al., 2024; Tervo-Clemmens et al., 2023). Similarly, most psychiatric disorders are associated with broad deficits across many different cognitive domains, rather than specific deficits in single domains (Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009; Snyder, 2013; Willcutt et al., 2005), supporting the role of a more general factor in conveying risk for psychopathology. Finally, metrics traditionally extracted from these subcomponent executive functioning tasks suffer from test-retest reliability issues and do not consistently relate to real-world outcomes such as mental health, physical health, or income (Eisenberg et al., 2019; Enkavi et al., 2019). Thus, thoughtful study of the developmental course and real-world correlates of task-general, rather than subdivided, executive functioning is warranted.

Model-based measurement of task-general executive functioning

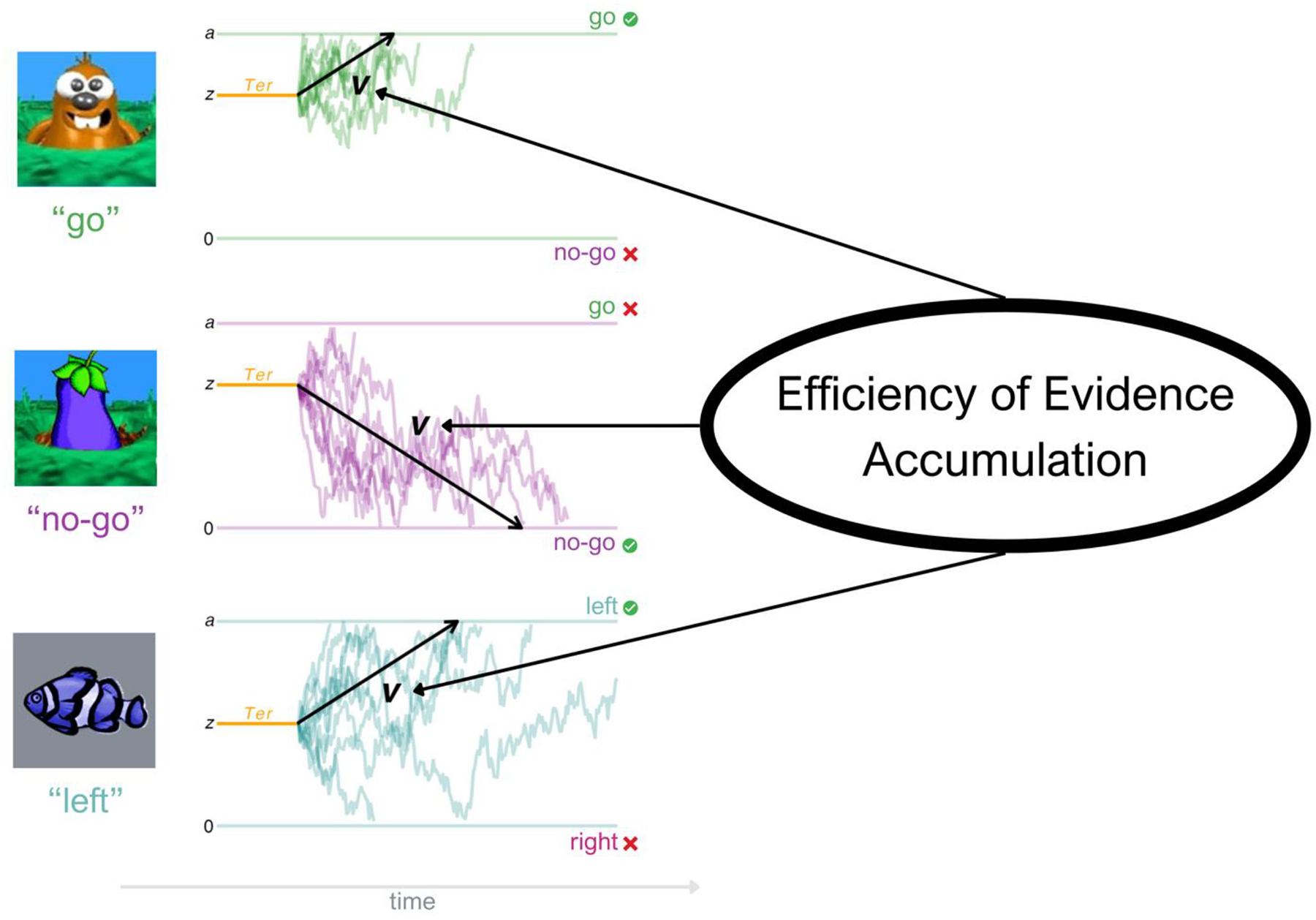

Quantifying task-general executive functioning can also be challenging, as traditional metrics (e.g. “accuracy” on any given task) provide information about performance on very different types of executive functioning tasks, which in turn can create illusory subfactors due to method variance alone (Loffler et al., 2024). Though used less frequently in clinical psychology, model-based approaches popular in mathematical psychology and computational psychiatry can provide a formal method for both explaining and quantifying task performance with a common metric that theoretically indexes the same process across many tasks (Huang-Pollock et al., 2017; Ratcliff, 2002; Ratcliff et al., 2016). For example, the diffusion decision model (DDM), one of the most widely used modeling frameworks in computational psychiatry, assumes that evidence driving a decision (i.e. choosing a response on a given forced-choice task) is gradually accumulated over time until a critical response threshold is reached (Ratcliff & Rouder, 1998; Figure 1). The DDM uses trial-by-trial accuracy and reaction time information to estimate several parameters including drift rate (v), boundary separation (a), and non-decision time (Ter), which together characterize how an individual accumulates evidence to make a decision (Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008). Among these, drift rate describes the rate at which individuals accumulate information relevant to making a response that is consistent with the task goals (Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008; Weigard & Sripada, 2021). In contrast, boundary separation measures response caution, and non-decision time reflects encoding and motor execution speed.

Figure 1. Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation.

Note. This figure depicts how Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation (EEA) is derived from several executive functioning task conditions. As pictured on the left, each condition is modeled with the Diffusion Decision Model (DDM), which assumes that evidence driving a decision (i.e. choosing a response) is gradually accumulated over time until a critical response threshold is reached (Ratcliff & Rouder, 1998). The DDM model parameter of interest is drift rate (v, pictured here in black), which describes the rate of evidence accumulation. Also pictured here are boundary separation (a), which captures response caution, and non-decision time (Ter), which includes encoding and output time. EEA is calculated via a latent factor explaining shared variance in v across various tasks and conditions, thus describing the general rate at which an individual gathers goal relevant evidence among noise to make adaptive choices across tasks and conditions (Weigard & Sripada, 2021). This metric can be calculated in this way from many choice tasks; the three conditions used for this study (Go/No-Go “go”, Go/No-Go “no-go”, and Stop Signal “go”) are pictured here. Data pictured here are simulated to depict a similar v value for the three conditions.

The DDM is biologically plausible in that the spiking behavior of neurons during choices in non-human primate research shows properties that are highly consistent with evidence accumulation (Cassey et al., 2016; Killeen et al., 2013; Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008; Smith & Ratcliff, 2004); additionally, diffusion model parameters relate to human brain activity (Kuhn et al., 2011; Liu & Pleskac, 2011; O’Connell et al., 2012; Turner et al., 2017; Weigard et al., 2020). This model has also been applied to commonly used executive functioning tasks, including the Go/No-Go task (Letkiewicz et al., 2024; Ratcliff et al., 2018) and Stop Signal task “go” choice (Nigg et al., 2018), though the vast majority of studies using these tasks do not yet take this approach.

Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation

Although the DDM has provided valuable insights into how efficiently individuals accumulate evidence within specific cognitive tasks, these models have traditionally been applied in isolation, leaving open the question of whether shared processes exist across tasks. Recent work suggests that drift rate, rather than being task-specific, may reflect a broader trait that drives individual differences in performance across many tasks, including executive function tasks (Lerche et al., 2020; Schmiedek et al., 2007; Weigard et al., 2021). This insight has led to the proposal that individual differences in executive functioning are largely driven by efficiency of evidence accumulation (EEA), a latent factor that explains shared variance in drift rate across different cognitive tasks. (Loffler et al., 2024; Weigard & Sripada, 2021). EEA is conceptualized as a task-general dimension that reflects how effectively an individual gathers goal-relevant information. (Weigard & Sripada, 2021; Figure 1). Thus, while observed drift rate parameters measure evidence accumulation for a single task or condition, EEA aims to capture a person’s general efficiency irrespective of the specific task conditions. Importantly, EEA contributes to goal-directed performance irrespective of whether it is opposed by irrelevant information or automatic processing. Thus, EEA is arguably a broader construct than “executive functioning”, in that it explains behavior across many tasks or task conditions that are not traditionally considered “executive”. Yet EEA has clear conceptual similarities to established definitions of executive processes in that it reflects an individual’s ability to selectively attend to goal-relevant information to produce adaptive responses (Miller & Cohen, 2001). The EEA framework provides a compelling explanation for emerging evidence that most variance in individual and developmental differences in executive function task performance is explained by a single task-general factor (Loffler et al., 2024; Tervo-Clemmens et al., 2023). Namely, that differences in performance on specific executive tasks (e.g., selecting the correct response on “no-go” trials despite opposed automatic processing) are mostly driven by an individual’s general ability to gather goal-relevant information, which similarly drives performance on other executive tasks and even on tasks not traditionally thought of as “executive” (e.g., selecting the correct response on “go” trials, even when opposed automatic processing is absent).

According to this framework, the task-general factor underlying executive functioning can be effectively measured with a latent variable comprised of drift rate estimates across different tasks. Unlike traditional EF metrics, which often show weak or inconsistent factor structures, EEA explains almost all variance in executive functioning performance in adult samples (Loffler et al., 2024). It also exhibits stronger test-retest reliability and better predictive validity for real-world behaviors related to executive functioning, including self-regulation and psychopathology risk (Lerche & Voss, 2017; Schubert et al., 2016; Weigard et al., 2021). EEA has also been linked to multiple psychiatric diagnoses, including ADHD (Ging-Jehli et al., 2021; Karalunas et al., 2014; Ziegler et al., 2016) and schizophrenia (Heathcote et al., 2015). Indeed, recent work suggests that EEA in adults may be a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology (Sripada & Weigard, 2021).

Much of this research, however, has focused on adults. The developmental stability, predictive utility, and neural correlates of EEA in youth remain largely unknown. Given that childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the development of executive functioning, examining EEA in younger populations could provide key insights into EEA as a transdiagnostic marker of psychopathology, both concurrently and over time.

Present Study

The present study examined EEA’s viability as a task-general, stable, valid, and biologically plausible measure of individual differences in executive functioning in a community sample of adolescents. We utilized Go/No-Go and Stop-Signal data from the Michigan Twin Neurogenetics Study (MTwiNS), a unique longitudinal twin study (N=708 children from 354 families) with oversampling for twins living in low-income neighborhoods, a strategy which is likely to enrich risk for psychopathology due to exposure to adversity. To evaluate EEA’s potential as an improved measure of executive functioning, we systematically compared it to traditional task-based EF metrics. Specifically, we tested: (1) Task-generality—whether EEA forms a coherent, cross-task latent factor; (2) Stability—whether EEA demonstrates rank-order stability across two adolescent waves; (3) Concurrent and predictive validity—whether EEA’s cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with temperament and psychopathology mirror or improve upon traditional EF measures; and (4) Biological plausibility—whether EEA or traditional EF metrics relate to inhibition-related brain activation in key regions such as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG; inhibition) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; error monitoring).

Methods

Participants

Participants were part of the Michigan Twins Neurogenetics Study (MTwiNS), an ongoing longitudinal neuroimaging project within the broader Michigan State University Twin Registry (see Burt & Klump, 2019). The 354 families participating in MTwiNS were originally identified through birth records and recruited into a representative sample based on the criterion that the family was living in a neighborhood with above-average levels of poverty (Burt & Klump, 2019). This recruitment strategy yielded a unique sampling frame that balances representation with enrichment for exposure to adversity which, unfortunately, increases risk for psychopathology (Burt et al., 2021). Although the ongoing MTwiNS project recruited twins to facilitate genetically-informed work on resilience to neighborhood disadvantage, twins are largely similar to ordinary siblings (Willemsen et al., 2021); thus, this unique dataset is also useful for investigating questions that do not leverage the twin design.

The 637 twins (from 337 pairs) included in the present study successfully completed at least one of two behavioral executive functioning tasks during their first MTwiNS visit, which occurred between September 2015 and March 2020 (i.e. before a data collection pause due to Covid-19). Of these 637 twins, 355 (from 183 pairs) returned and had executive functioning data from a second visit at least one year after their first visit. This number is smaller than originally planned due to the Covid-19 data freeze in March 2020. The twins were 7 to 19 years old upon first visit (Mean=14.7, SD=2.1; 54.5% male; less than 2% of the present sample was 10 or younger) and 10 to 20 years old upon second visit (Mean=15.7, SD=2.3; 54.4% male). The breakdown of twins’ parent-reported race and ethnicity reflected the surrounding area (80% White, 12% Black, 5% Other, 1% Latino/Latina, 1% Pacific Islander, 1% Native American, 1% Asian). Median reported family annual income for this sample was $70,000 to $79,999 and ranged from less than $4,999 to greater than $90,000. Eleven percent of included children were from families reporting an annual income below the 2020 federal poverty line of $26,246 per year and 53% of families were below the living wage for a family of 4 in Michigan (with one parent working; http://livingwage.mit.edu/states/26). Parents provided informed consent and children provided assent in compliance with the policies of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

Procedure

Twins and their primary caregivers took part in a day-long visit to the University of Michigan which included a mock MRI scan as well as a one-hour blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) fMRI scan for each twin. Twins completed several tasks in the scanner, including a Go/No-Go task. Outside of the scanner, twins completed several additional computer tasks, including a Stop-Signal task, and a battery of child-report questionnaires. The Stop-Signal task was added partway through data collection; thus, this task is missing at random for 303 children at the first visit. Primary caregivers completed a demographic interview with an examiner and a battery of self- and parent-report questionnaires. Families who participated in Time 1 were invited for a return visit (Time 2) ~one year after the first visit (Mean=1.32 years, SD=0.45 years, Range=0.67–3.00). These return visits followed a nearly identical protocol.

Measures

Go/No-Go Task

The Go/No-Go task used in this study was adapted from Casey et al. (1997), in which neural reactivity during inhibition is elicited via a “whack-a-mole” game (stimuli courtesy of Sarah Getz and the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology; task downloaded from http://fablab.yale.edu/page/assays-tools). Full task details are available in the Supplemental Methods.

In order to compare EEA to traditional metrics, we extracted two commonly-used performance metrics from the go/no-task. False alarm rate was calculated as the percent of “no-go” trials for which a participant incorrectly responded when a non-response was warranted. Standard Deviation of Reaction Time (SDRT) was calculated as the standard deviation of reaction time for “go” trials, excluding failed “go” trials. Participants with overall below-chance performance (<55%), below-chance performance on “go” trials (<55%), or with more than 5% of trials implausibly “fast guesses” (<150ms; Voss et al., 2013) were not considered to be meaningfully participating in the Go/No-Go task, and were therefore excluded from Go/No-Go analyses (N=13 first visit, N=5 second visit), leaving N=589 individuals with viable Go/No-Go data at the first visit, and N=307 individuals with viable Go/No-Go data at the second visit (Table S1).

Stop-Signal Task

The child-friendly Stop-Signal task used in this study was a 10 minute, 150 trial task adapted from Bissett & Logan (2012) as described previously (Begolli et al., 2018). Full task details are available in the Supplemental Methods.

In order to compare EEA to traditional metrics, we extracted two commonly-used performance metrics from the stop-signal task. Stop-signal reaction time was calculated using the non-parametric method recommended by Verbruggen et al. (2019). This involves integrating the “go” response time distribution, replacing omissions with the maximum “go” response time, finding the point where the integral equals the probability of responding on “stop” trials, and subtracting the mean stop-signal delay (SSD) from the response time at this point. Standard Deviation of Reaction Time (SDRT) was calculated as the standard deviation of reaction time for “go” trials, excluding failed “go” trials. Participants with overall below-chance performance (<55%), below-chance performance on “go” trials (<55%), a high non-response rate on “go” trials (>25%), or with more than 5% of trials implausibly “fast guesses” (<150ms; Voss et al., 2013) were not considered to be meaningfully participating in the task and were therefore excluded from Stop-Signal analyses (N=59 first visit, N=63 second visit), leaving N=334 individuals with viable Stop-Signal data at the first visit, and N=295 individuals at the second visit (Table S1).

Due to a programming error, two slightly different task versions were used (response cutoff 1.5s instead of 0.85s). The task version with the longer cutoff was only used for 60 children (21 at time 1, 39 at time 2). To account for this difference, task version was regressed out of all metrics extracted from the Stop-Signal task before continuing with analyses. Detailed descriptions of these regressions are presented in Table S2.

Self-Report of Executive Functioning

Twins reported on their executive functioning abilities via the “effortful control” superscale (α = 0.78) of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ; Capaldi & Rothbart, 1992), which combines the attention, activation control, and inhibitory control subscales (Snyder et al., 2015). The attention scale (6 items) measures the ability to focus and shift attention, the activation control scale (5 items) measures the ability to begin and complete tasks, and the inhibitory control scale (5 items) measures the ability to suppress unwanted behaviors (Snyder et al., 2015).

Psychopathology

Parents reported on children’s psychopathology via the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Scales of interest included the total problems, externalizing problems (combines rule breaking and aggressive behavior), internalizing problems (combines anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic problems), and attention problems scales. Per ASEBA recommendations, we used raw scores for each subscale (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). A previous version of this manuscript used a combined informant approach, creating a composite of parent- and child-report; thus, we ran these analyses and included the results in the supplement for full transparency. However, we focus on parent-report here to decrease multiple comparisons and simplify reporting of results (α=0.87 [Internalizing], α=0.88 [Externalizing], α=0.84 [Attention Problems], and α=0.94 [Total Problems]). Almost all participants with executive functioning data had psychopathology data (N=2 missing at Time 1, N=0 at Time 2).

Functional neuroimaging

Functional imaging data were acquired using one of two GE Discovery MR750 3T scanners located at the University of Michigan Functional MRI Laboratory. Preprocessing followed our lab standard pipeline; details are available in the Supplemental Methods.

After preprocessing, the Artifact detection Tools toolbox (ART; https://www.nitrc.org/projects/artifact_detect/) was used to detect translation or rotational motion outlier volumes that remained after earlier QA (>2mm movement or 3.5 rotation) and to scrub them from the dataset. Preprocessed images were also visually inspected for major artifacts. Coverage of the frontal lobe was checked using the WFU PickAtlas “frontal lobe” structural mask (Maldjian et al., 2003). A participant’s fMRI data were considered unusable if they contained obvious prefrontal artifacts, had less than 90% coverage of the frontal mask, or had more than 5% of scans identified as motion outliers. Preprocessing was conducted in containerized versions of SPM12, and the standard pipeline is accessible via Github (https://github.com/UMich-Mind-Lab/pipeline-task-standard). After quality checks, 549 participants with behavioral data had usable fMRI data (Table S3).

Functional data were modeled using the general linear model in SPM12. Three conditions were modeled: correct No-Go trials, in which a participant correctly withheld a response to a No-Go stimulus; incorrect No-Go trials, in which a participant incorrectly responded to a No-Go stimulus; and Go trials, in which a participant saw a Go stimulus. Incorrect Go trials were not modeled due to the expected high hit rates for Go trials (median 100%). For each participant, the main contrast of interest was all No-Go (including both correct and incorrect) > Go.

Analytic Plan

Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation (EEA)

Diffusion Model Analysis.

Diffusion model parameters were estimated using individual-level Bayesian estimation methods implemented in the Dynamic Models of Choice suite of functions (Heathcote, 2019) which uses an adaptation of the differential evolution Markov chain Monte Carlo sampler (Turner et al., 2013), in R version 4.1.0 (R Core Team, 2021). Trials with implausibly fast response rates (<150ms; Voss et al., 2013) were excluded from the DDM analysis. Broad and informative priors were used for parameter estimation (Table S4) and the automated RUN.dmc() function was used to obtain convergence, which was then confirmed via visual inspection of chains. Drift rate was estimated separately for “go” and “no-go” trial types within the Go/No-Go task due to previous evidence that it may systematically differ across the two conditions (Huang-Pollock et al., 2017; Ratcliff et al., 2018). A single drift rate parameter was estimated for “go” choice trials from the Stop-Signal task, also following prior work (Huang-Pollock et al., 2017; Karalunas et al., 2014). Two other diffusion model parameters, boundary separation (a) and non-decision time (Ter), were also extracted from each task for supplemental analysis. Given that boundary separation primarily indexes response caution and non-decision time reflects task-specific perceptual and motor processing, these parameters were not included in our latent model, which was designed to capture shared variance in evidence accumulation across tasks.

Question 1: Assessing task-generality: Can EEA form a coherent factor across tasks and task conditions?

To assess viability as a task-general, stable individual difference, we first assessed across-task reliability for drift rate as well as the traditional metrics. We ran zero-order Pearson correlations to assess rank-order stability; i.e., does performance on one task predict performance on another task?

We then calculated individual participants’ EEA factor scores as latent factor scores from the three drift rate parameters (go, no-go, Stop-Signal) in Mplus version 8.10 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) via R (R Core Team, 2021), tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019), and the MplusAutomation package (Hallquist & Wiley, 2018). All participants with any executive functioning data were included, and factor models used maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) which are robust to missingness and to non-normal data.

Question 2: Assessing stability: How stable across time is executive functioning performance as measured by EEA vs by traditional metrics?

We assessed longitudinal stability of EEA and traditional metrics within our sample for those individuals who returned for a second visit (~1 year later) and had usable data at that timepoint (N=355 with any data at time 2; N=297 with EEA at both timepoints, 278 with Go/No-Go, 99 with Stop Signal; Table S1). We first ran zero-order Pearson correlations to assess rank-order stability. To ensure findings were not affected by relatedness of twins, missingness on the stop-signal task, or time between visits, we also ran follow-up models in Mplus which included time between visits as a covariate, clustered for family, and used maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR).

Because our sample covered a wide range of ages, we also evaluated associations between executive functioning metrics and age by conducting visual inspections of plotted data and by fitting multilevel repeated measures models in Mplus using MLR. Models included clustering for family and individual, with each executive functioning metric “on” age as a “between” effect, and a random intercept for the executive functioning metric as a “within” effect to account for repeated measurements on the same individuals.

Question 3: Assessing validity: Do patterns of associations with EEA reflect traditional metrics and align with expectations for measuring “executive functioning”?

To assess whether executive functioning performance as measured by EEA and by traditional metrics related to self-reported effortful control, total problems, attention problems, externalizing problems, or internalizing problems, we used linear regression within Mplus, controlling for age and sex, and accounting for relatedness within families using the “cluster” command which adjusts standard errors to account for the nesting within the data. The psychopathology variables were positively skewed (i.e. zero-inflated); thus, as above, we used MLR estimation which is robust to non-normality.

For prospective associations with psychopathology, because of the variability in age and time between the two visits, we repeated the same analyses as above, using age at the second visit and adding time between visits as a predictor. Finally, we re-ran these models with controls for previous levels of psychopathology to assess whether performance predicted change in symptoms of psychopathology between visits.

Question 4: Assessing biological plausibility: Does executive functioning performance as measured by EEA or by traditional metrics relate to inhibition-related brain activation?

To assess the biological relevance of executive functioning task performance as measured by EEA and traditional metrics, we used linear regression in SPM12 to investigate whether executive functioning performance as measured by these variables is associated with brain activation during the contrast of interest (all no-go > go). Models controlled for age, sex, and scan protocol. We used a stringent, whole-brain approach, with cluster thresholding determined for each model by 3dttest++ within AFNI (Cox, 1996; Cox et al., 2017a, 2017b) based on an overall error rate corrected for multiple comparisons (alpha) of 0.05 with a voxel-wise threshold of p<0.001.

Missing Data

As noted above, Stop-Signal is missing at random for the first visit for many children (N=303). A full breakdown of data availability by timepoint is available in Table S1. To evaluate whether SSRT missingness introduced systematic differences, we compared participants with and without SSRT data on demographic and outcome variables. This analysis is presented in Table S5. All Mplus models used maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR), which is robust to non-normality and missingness.

Transparency and Data Sharing Statement

Full anonymized functional imaging and behavioral data for the entire MTwiNS study are shared via the NIMH Data Archive (https://nda.nih.gov/edit_collection.html?id=2818). The standard functional imaging pipeline is publicly available on Github (https://github.com/UMich-Mind-Lab/pipeline-task-standard). Code and output for all latent modeling and regression analyses is available on OSF (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8KNUV). All materials described in the methods section are either linked, cited, or available upon request. This study was not preregistered; however, hypotheses and analytic plans were determined a priori as part of a dissertation prospectus (documentation available upon request).

Results

The DDM fit the data well for all conditions and parameter recovery for drift rate (v) was excellent for all tasks and conditions (Figures S1 & S2).

Question 1: Assessing task-generality: Can EEA form a coherent factor across tasks and task conditions?

The individual drift rate parameters demonstrated better cross-task reliability than the other extracted metrics that were available for both tasks at the first visit (r=.28 and .30 for Go and No-Go with Stop-Signal, respectively; 95% CI [.17, .38] and [.19, .40]; p<0.01; Table 1). No other available metric demonstrated cross-task reliability significantly different from 0 at the first visit, meaning that a participant who performed better than their peers for a given metric on one task did not reliably perform better than others for that same metric on the second task (Table 1). For example, though SDRT theoretically indexes the same process across both tasks (i.e. variance in reaction time), children with more variable reaction times on one task did not necessarily show the same pattern on the other task.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals for cross-task Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation (EEA), single-task drift rate, and traditional metrics at Time 1 (N=637)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EEA Factor | −0.00 | 0.67 | |||||||

| 2. GNG Drift Rate (No-Go) | 2.52 | 0.73 | .90** | ||||||

| [.88, .91] | |||||||||

| 3. GNG Drift Rate (Go) | 3.07 | 0.84 | .89** | .61** | |||||

| [.87, .91] | [.56, .66] | ||||||||

| 4. GNG False Alarm Rate | 0.11 | 0.10 | −.67** | −.68** | −.54** | ||||

| [−.71, −.62] | [−.72, −.63] | [−.59, −.48] | |||||||

| 5. GNG SDRT | 0.15 | 0.05 | −.82** | −.59** | −.88** | .30** | |||

| [−.84, −.79] | [−.64, −.54] | [−.90, −.86] | [.22, .37] | ||||||

| 6. SST Drift Rate | 2.53 | 0.59 | .50** | .30** | .28** | −.15* | −.32** | ||

| [.41, .58] | [.19, .40] | [.17, .38] | [−.26, −.03] | [−.42, −.21] | |||||

| 7. SST SSRT | 0.20 | 0.05 | −.21** | −.23** | −.13* | .10 | .12* | −.16** | |

| [−.32, −.11] | [−.34, −.11] | [−.24, −.01] | [−.02, .22] | [.01, .24] | [−.27, −.06] | ||||

| 8. SST SDRT | 0.13 | 0.02 | −.15** | −.05 | −.02 | −.00 | .05 | −.53** | −.06 |

| [−.25, −.04] | [−.16, .07] | [−.14, .09] | [−.12, .12] | [−.07, .16] | [−.60, −.44] | [−.17, .05] |

Note. M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively. GNG indicates metric derived from Go/No-Go task. SST indicates metric derived from Stop-Signal task. Values for traditional metrics are not standardized here (i.e. mean false alarm rate of 0.11 reflects 11% false alarm rate). Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. The confidence interval is a plausible range of population correlations that could have caused the sample correlation (Cumming, 2014). Confidence intervals presented here are not corrected for relatedness within families.

indicates p < .050.

indicates p < .010. Table generated with the apaTables package (Stanley & Spence, 2018).

Because cross-task reliability was reasonable for drift rate at the first visit as described above, as well as at the second visit (r=.27 and .29 for Go and No-Go with Stop-Signal, respectively, at time 2; 95% CI [.15, .38] and [.17, .40]; p<0.01), we proceeded with creating an EEA factor score for each time point. The EEA latent factor converged at each timepoint, and loadings for all three conditions (go, no-go, Stop-Signal) were significant and within the acceptable range at both visits, though loadings for Stop-Signal were lower than those for the go and no-go conditions of the Go/No-Go task (At Time 1, λno-go=0.78, λgo=0.78, λsst=0.42, all p<0.001; At Time 2, λno-go=0.82, λgo=0.76, λsst=0.36, all p<0.001), likely due to shared method variance between the two Go/No-Go measures. Model fit was uninformative due to saturated models.

Covariance coverage was extracted from the latent factor models at both timepoints to assess data availability across indicators and is available in Table S6. Coverage values for the Time 1 model ranged from 0.449 to 0.925, with an average off-diagonal coverage of 0.608. For the Time 2 model, coverage ranged from 0.696 to 0.865, with an average off-diagonal coverage of 0.752. These values are consistent with expectations given the quasi-planned missing design and are well within the range where FIML estimation performs robustly (Enders, 2022; Graham et al., 2006).

Descriptive statistics for, and correlations among, all of the extracted metrics from each task at time 1, including the cross-task EEA factor and single-task drift rate scores, are available in Table 1. Distributions of all metrics are available in Figure S3.

Question 2: How stable is executive functioning performance as measured by EEA vs by traditional metrics?

EEA demonstrated comparable developmental stability to the traditional metrics (r=.53, 95% CI [.44, .60], p<0.001; Table S7; Figure 2A). Confidence intervals for EEA and most traditional metrics were overlapping, indicating similar developmental stability; the one exception was SSRT, which had poor stability (r=.03, 95% CI [−.18, .23], p = 0.799; Table S7; Figure 2A). To check that this poor stability was not driven by our regressions removing variance due to SST version, we re-ran the SSRT test-retest correlation with the original SSRT values at both timepoints. This did not improve the results (r=.03). Follow-up Mplus models using MLR to better handle missingness on Stop-Signal and time between visits, and with clustering for family, produced similar results (Table S8).

Figure 2.

Note. This figure depicts developmental stability (A) and individual-level change from Time 1 to Time 2 (B) for executive functioning scores, as measured by Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation (EEA), Go/No-Go Standard Deviation of Reaction Time (SDRT), Go/No-Go False Alarm Rate, Stop Signal Standard Deviation of Reaction Time, and Stop Signal Reaction Time (SSRT). In (B), scores are plotted against child age in years at time of testing. Each line represents one child. In general, children improved with age on all metrics. This pattern is more apparent for task-general EEA and go/no-go metrics, which may be driven by a higher N for these tasks, as the Stop Signal task was added to the Time 1 protocol partway through data collection (N=297 for EEA, 278 for Go/No-Go, 99 for Stop Signal).

Visual inspection of EEA and traditional metrics plotted against twin age indicated predictable change with age, such that performance as measured by these metrics improved between visits and with age (Figure 2B). Repeated measures models with nested random effects for family and twin confirmed an effect of age on task-general EEA (β= 0.58 & T=11.48; Table S9) as well as all other metrics, such that all metrics improved with age across our sample (Table S9).

Question 3: Do patterns of associations with EEA reflect traditional metrics and align with expectations for measuring “executive functioning”?

Zero-order correlations for EEA and traditional metrics with all self- and parent-report outcomes are reported in Table S10. Results of all models controlling for age, sex, and relatedness within families are presented in Table 2 and Figure S4.

Table 2.

Standardized regression coefficients with confidence intervals for extracted metrics on concurrent and prospective self- and parent-report measures

| Task-General EEA | GNG False Alarm Rate | GNG SDRT | SST SSRT | SST SDRT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concurrent | >1 year | Concurrent | >1 year | Concurrent | >1 year | Concurrent | >1 year | Concurrent | >1 year | |

| Effortful Control | 0.24** | --- | −0.10* | --- | −0.20** | --- | −0.06 | --- | −0.12* | --- |

| [0.16, 0.32] | --- | [−0.19, −0.02] | --- | [−0.28, −0.12] | --- | [−0.17, 0.04] | --- | [−0.22, −0.03] | --- | |

| Attention Problems | −0.19** | −0.09 | 0.17** | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| [−0.29, −0.10] | [−0.24, 0.06] | [0.08, 0.27] | [−0.04, 0.25] | [0.00, 0.20] | [−0.06, 0.24] | [−0.03, 0.20] | [−0.09, 0.39] | [−0.02, 0.17] | [−0.12, 0.14] | |

| Externalizing | −0.10* | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| [−0.19, −0.01] | [−0.20, 0.04] | [−0.03, 0.18] | [−0.05, 0.27] | [−0.01, 0.14] | [−0.05, 0.17] | [−0.07, 0.14] | [−0.17, 0.20] | [−0.04, 0.13] | [−0.18, 0.19] | |

| Internalizing | 0.00 | 0.15* | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.05 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| [−0.09, 0.09] | [0.03, 0.26] | [−0.07, 0.12] | [−0.20, 0.06] | [−0.11, 0.05] | [−0.22, 0.00] | [−0.05, 0.15] | [−0.37, 0.14] | [−0.14, 0.07] | [−0.12, 0.18] | |

| Total Problems | −0.10* | −0.01 | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| [−0.19, −0.02] | [−0.13, 0.12] | [0.01, 0.20] | [−0.11, 0.22] | [−0.04, 0.12] | [−0.09, 0.13] | [−0.05, 0.16] | [−0.20, 0.24] | [−0.07, 0.12] | [−0.10, 0.15] | |

Note. Values indicate the standardized estimate (β) for each metric predicting self-report of effortful control, measured via the effortful control superscale of the EATQ (Capaldi & Rothbart, 1992) and parent-report of symptoms of psychopathology, measured via parent-report on the CBCL (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Models used maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR), controlled for age and sex, and clustered by family to account for relatedness. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each standardized estimate.

indicates p < .050.

indicates p < .010.

Concurrent self-report effortful control

When accounting for age, sex, and relatedness within families, better EEA related to better self-report effortful control (β=0.24; 95% CI [0.16, 0.32]; p<0.001; Table 2). This was also the case for Go/No-Go False Alarm Rate (β=−0.10; 95% CI [−.19,−.02]; p = 0.011), Go/No-Go SDRT (β=−0.20; 95% CI [−0.28, −0.12]; p < 0.001), and Stop Signal SDRT (β=−0.12; 95% CI [−0.22, −0.03]; p = 0.010).

Concurrent psychopathology

When accounting for age, sex, and relatedness within families, worse EEA scores related to more concurrent attention problems (β=−.19; 95% CI [−.29,−.10]; p < 0.001; Table 2) as well as more externalizing problems (β=−.10; 95% CI [−.19,−.01]; p = 0.028; Table 2) and more total problems (β=−.10; 95% CI [−.19,−.02]; p = 0.016; Table 2). Go/No-Go False Alarm Rate was associated with attention problems and total problems, while Go/No-Go SDRT was only associated with attention problems (Table 2). Neither traditional Stop Signal metric was associated with any measure of psychopathology.

Prospective psychopathology

When accounting for age, sex, time between visits, and relatedness within families, no metrics measured at time 1 were associated with attention, externalizing, or total problems at time 2 (Table 2). In contrast to concurrent findings, better EEA scores at the first visit were associated with more internalizing problems overall at the second visit (β=.15; 95% CI [.03, .26]; p = 0.013; Table 2). This effect held when adding an additional control for previous level of internalizing problems (β=.09; 95% CI [.00, .18]; p = 0.049; Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

Results from models identical to those described above, using combined report instead of parent-only report, are summarized in Table S11. Results were largely the same; notably, better EEA scores at first visit were associated with less externalizing problems at second visit when considering combined-informant report (β=−0.12; 95% CI [−.00, −.24]; p = 0.040; Table S11).

Finally, we report the above models with the additional parameters extracted from the diffusion model for each task (a and Ter) in Table S12. Briefly, boundary separation (a) was not related to any personality or psychopathology dimensions (Table S12). Faster Ter in the Stop-Signal task, but not the Go/No-Go task, was related to worse concurrent effortful control (β=0.19; 95% CI [0.10, 0.28]; p < 0.001; Table S12), greater concurrent externalizing (β=−0.12; 95% CI [−0.22, −0.01]; p = 0.034), and greater concurrent total problems (β=−0.12; 95% CI [−0.22, −0.01]; p = 0.034).

Question 4: Does executive functioning performance as measured by EEA or by traditional metrics relate to brain activation?

When accounting for age, sex, and scan protocol, better performance as measured by two of the extracted metrics (EEA, and Go/No-Go SDRT) related to increased inhibition-related (no-go > go) brain activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and the right superior temporal gyrus (Table S13; significant activation for these metrics with overlap displayed in Figure 3). Though the superior temporal gyrus clusters had similar peak voxels, their shapes varied: for example, the superior temporal gyrus cluster associated with EEA extended along the temporal lobe to include the medial temporal gyrus (Figure S5). Details regarding all significant clusters are available in Table S13. Notably, there were bilateral inferior frontal gyrus clusters in which EEA correlated with activation as hypothesized; however, these clusters were too small to be significant in whole brain analyses (p < 0.001; k=131 and 124; cutoff k=165).

Figure 3. Unique and overlapping regions in which better task-general EEA (red) and Go/No-Go SDRT (blue) correlated with increased inhibition-related brain activation.

Note. Slice location of this image is (−3, 44, 11). Image depicted in neurological space. This image depicts substantial overlap in regions correlating with executive functioning performance as measured by task-general EEA (red) and Go/No-Go Standard Deviation of Reaction Time (SDRT; blue) within the anterior cingulate cortex and right superior temporal gyrus. Additive overlap between images is indicated with color blending; therefore, locations indicated in purple represent areas of overlap. None of the other traditional metrics (Go/No-Go False Alarm Rate, Stop Signal Reaction Time, Stop Signal SDRT) correlated with inhibition-related activation. Image generated from activation maps cluster-thresholded with 3dttest++ (Cox, 1996; Cox et al., 2017a, 2017b) in SPM (Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging) and rendered via MRIcroGL (Rorden & Brett, 2000).

Missing Data

To assess potential bias due to missing Stop-Signal task data, we compared participants with and without Stop-Signal data at Time 1 on key baseline variables. As shown in Table S5, EEA scores did not differ significantly between groups (t-test p = .146; Kolmogorov-Smirnov p = .088), supporting the robustness of the latent factor methodology. Additionally, attention and externalizing problems, outcomes most closely linked to executive functioning, did not differ by missingness. Participants with Stop-Signal data were, on average, older, more likely to be male, and had longer time lags between visits. They also showed modestly higher internalizing symptom scores. All between-participant models included age and sex as covariates. To further account for group differences, we re-ran all models predicting psychopathology from task-based metrics (Question 3 above) with internalizing symptoms included as an additional covariate. Results remained consistent (see Table S14). This approach aligns with prior guidance suggesting that including variables associated with missingness can mitigate bias in analyses with non-random missing data (Collins et al., 2001).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation (EEA) as a novel, task-general measure of executive functioning in adolescents. Using DDM and latent factor modeling, we found that drift rate, the model parameter from which EEA is calculated, demonstrated stronger cross-task reliability than traditional metrics. The EEA latent factor demonstrated similar test-retest reliability to traditional metrics and followed similar patterns of associations with self-report effortful control and self- and parent-report concurrent psychopathology. Finally, fMRI analyses revealed that EEA and one single-task traditional metric (Go/No-Go SDRT) were associated with inhibition-related brain activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and the superior temporal gyrus. These findings suggest that EEA provides some advantages over traditional metrics, particularly in terms of cross-task reliability, while maintaining meaningful links to cognitive, clinical, and neurobiological outcomes.

Drift rate, the parameter underlying EEA, demonstrated significantly better cross-task reliability (r = .28–.30) than traditional metrics of inhibition (e.g., SSRT, Go/No-Go false alarm rate) and response variability (SDRT), which showed little to no cross-task reliability. These findings align with prior work conceptualizing EEA as a task-general individual difference dimension (Lerche et al., 2020; Weigard et al., 2021; Weigard & Sripada, 2021), extending this work to include adolescence. It also suggests that one of the key benefits of adopting an EEA-based conceptualization of task-general executive functioning is that it allows for a more cohesive psychometric structure across tasks, facilitating the formation of cross-task latent variables. This stands in contrast to traditional executive function metrics, which have recently been found to show weak and inconsistent relations with one another across studies, preventing the identification of a reliable factor structure (Karr et al., 2018).

EEA demonstrated reasonable developmental stability (r = .53) across a 1–3 year span, comparable to or stronger than traditional metrics. This finding is in line with previous work which has found EEA and related DDM parameters to have good test-retest reliability (Lerche & Voss, 2017; Schubert et al., 2016; Weigard et al., 2021). While somewhat lower than previous work (e.g. Lerche & Voss, 2017, r>0.70), this stability is remarkable given the timespan between visits (>1 year) during adolescence, a developmental period when cognitive development has not yet stabilized (Kolb et al., 2012). Additionally, all extracted parameters, including EEA, showed expected age-related improvements (Diamond, 2013; Kolb et al., 2012). Future work should explore short-term test-retest reliability (~1 week) and extend longitudinal designs beyond two timepoints to better characterize executive function trajectories.

Consistent with theoretical expectations, better performance as measured by almost all metrics (EEA, Go/No-Go False Alarm Rate, SDRT for both tasks) was associated with better self-reported effortful control. Similarly, better performance as indexed by EEA, Go/No-Go False Alarm Rate, and Go/No-Go SDRT was associated with fewer attention problems. Better EEA also related to fewer concurrent externalizing problems, a CBCL subscale which includes aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors, consistent with recent work in adults (Sripada & Weigard, 2021). Notably, neither EEA nor traditional metrics predicted future total, attention, or externalizing problems when controlling for baseline symptoms, suggesting that executive functioning in this age range may be more indicative of current rather than future functioning. Our findings contrast a recent finding in ABCD that drift rate predicted change in attention problems (Wiker et al., 2024). It is possible that our sample did not have the statistical power to detect a subtle change effect, but that it would have been detected in a sample of greater size. Longitudinal work with more timepoints and a longer timespan could clarify this issue.

Interestingly, increased EEA was uniquely associated with increased prospective internalizing problems, even when controlling for initial levels. This result runs counter to the association between better EEA and fewer overall problems, but reflects recent evidence that cognitive performance is inversely associated with externalizing behaviors but positively linked to some internalizing traits (Brislin et al., 2022). Future research should examine whether EEA reflects neurocognitive processes that, when underactive, contribute to externalizing behaviors and, when overactive, relate to internalizing symptoms.

Functional neuroimaging analyses revealed that EEA and one traditional metric (Go/No-Go SDRT) correlated with increased inhibition-related brain activation in the anterior cingulate cortex, a major salience network hub (Seeley et al., 2007), important for error processing (Bush et al., 2000) and conflict monitoring (Botvinick et al., 2004). This region has previously been implicated when employing computational models of the Go/No-Go task in young adults (Weigard et al., 2020); thus, these findings extend this work to adolescents. Additionally, both metrics were associated with activation in the superior temporal gyrus, a region implicated in change detection and response inhibition (Opitz et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2017). Notably, we did not find an association between EEA and IFG activation as hypothesized; however, subthreshold bilateral IFG clusters were noted (p<0.001, k=131 and 124; cutoff k=165). Overall, our findings indicate that EEA has robust and conceptually relevant brain correlates.

Though this study has major strengths, including a large, well-sampled cohort with adversity exposure, two waves of data collection, and multimodal outcomes, several limitations should be considered. First, the associations between EEA and symptoms of psychopathology were not corrected for multiple comparisons; however, our goal was to describe the nomological network rather than to conduct strict hypothesis testing. Second, our measurement of task-general executive functioning was constrained to two relatively brief tasks due to fMRI-related time constraints. This likely contributed to the lower loadings observed for the Stop-Signal task in our latent factor, as the Go/No-Go task was represented twice and thus introduced shared method variance. Future work should include additional tasks beyond response inhibition and extend task duration to allow for computational model fitting to portions of the task for within-task comparison. Third, we followed ASEBA guidelines by using raw CBCL scores rather than normed T scores. Although T scores incorporate normative adjustments for age and sex, we addressed these variables directly as covariates in our analyses. Future research might compare scoring methods to further clarify how EEA relates to mental health outcomes across diverse populations. Fourth, while our models accounted for family clustering, we did not differentiate between MZ and DZ twins when modeling within-family residual variances. Preliminary checks indicated that clustering by zygosity did not explain additional variance beyond clustering by family; however, this remains an important consideration for future twin-based studies of EEA. Finally, while missingness was non-trivial, it was largely driven by study design factors rather than participant characteristics. Future work should continue to assess the impact of missingness and leverage approaches such as sensitivity analyses or multiple imputation where appropriate.

In summary, EEA provides a promising computational measure of executive functioning, offering superior cross-task reliability, strong theoretical grounding, and meaningful links to psychopathology and neurobiology. EEA demonstrated superior cross-task reliability when compared to other metrics, reasonable test-retest reliability, and changed predictably with age within our sample. EEA was associated with concurrent attention and externalizing problems and was associated with inhibition-related brain activation in two relevant regions, the anterior cingulate cortex and the right superior temporal gyrus. While some traditional metrics followed similar patterns, EEA integrates accuracy and reaction time to better characterize performance across tasks.

Overall, these findings highlight the potential for computational methods to improve the measurement of executive functioning performance in adolescents, while also revealing that some traditional metrics (i.e. SDRT) follow similar patterns of association and provide a reasonable alternative when computational modeling is not possible. Beyond measurement advantages, these findings also provide strong theoretical support for EEA as a computationally rigorous and biologically grounded explanation for task-general executive functioning in adolescents, which promises to advance translational research in the field by facilitating more precise theoretical explanations and stronger links with neurobiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIMH) and the Office of the Director National Institute of Health (OD), under Award Numbers UG3MH114249 and R01-MH081813, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD093334 and R01-HD066040. Funding was also provided by a NARSAD young Investigator Grant from the Brain and Behavior Foundation and the Avielle Foundation. R. C. Tomlinson was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 1256260 and by a postdoctoral training grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIA: T32AG049663). A. S. Weigard was supported by K23 DA051561 and R21 MH130939. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIMH, NICHD, NIA, or NSF.

Footnotes

Prior dissemination: This research has been accepted for presentation at the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD) Biennial Meeting in May 2025. Additionally, an earlier version of this work was included as part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation, which is publicly available through the University of Michigan’s institutional repository. However, the current manuscript represents a substantially revised and expanded version that includes additional analyses and updated conclusions.

Ethical Approval Statement: This study was approved by the University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) under study protocol HUM00163965. Informed consent and/or assent were obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians in accordance with ethical guidelines for human subjects research.

Transparency and Data Sharing Statement:

Full anonymized functional imaging and behavioral data for the entire MTwiNS study are shared via the NIMH Data Archive (https://nda.nih.gov/edit_collection.html?id=2818). The standard functional imaging pipeline is publicly available on Github (https://github.com/UMich-Mind-Lab/pipeline-task-standard). Code and output for all latent modeling and regression analyses is available on OSF (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8KNUV). All materials described in the methods section are either linked, cited, or available upon request. This study was not preregistered; however, hypotheses and analytic plans were determined a priori as part of a dissertation prospectus (documentation available upon request).

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the Aseba School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Begolli KN, Richland LE, Jaeggi SM, Lyons EM, Klostermann EC, & Matlen BJ (2018). Executive Function in Learning Mathematics by Comparison: Incorporating Everyday Classrooms into the Science of Learning. Think Reason, 24(2), 280–313. 10.1080/13546783.2018.1429306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissett PG, & Logan GD (2012). Post-Stop-Signal Slowing: Strategies Dominate Reflexes and Implicit Learning. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform, 38(3), 746–757. 10.1037/a0025429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemen AJP, Oldehinkel AJ, Laceulle OM, Ormel J, Rommelse NNJ, & Hartman CA (2018). The Association between Executive Functioning and Psychopathology: General or Specific? Psychol Med, 48(11), 1787–1794. 10.1017/S0033291717003269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, & Carter CS (2004). Conflict Monitoring and Anterior Cingulate Cortex: An Update. Trends Cogn Sci, 8(12), 539–546. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin SJ, Martz ME, Joshi S, Duval ER, Gard A, Clark DA, Hyde LW, Hicks BM, Taxali A, Angstadt M, Rutherford S, Heitzeg MM, & Sripada C (2022). Differentiated Nomological Networks of Internalizing, Externalizing, and the General Factor of Psychopathology (‘P Factor’) in Emerging Adolescence in the Abcd Study. Psychol Med, 52(14), 3051–3061. 10.1017/S0033291720005103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, & Klump KL (2019). The Michigan State University Twin Registry (Msutr): 15 Years of Twin and Family Research. Twin Res Hum Genet, 22(6), 741–745. 10.1017/thg.2019.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Klump KL, Vazquez AY, Shewark EA, & Hyde LW (2021). Identifying Patterns of Youth Resilience to Neighborhood Disadvantage. Res Hum Dev, 18(3), 181–196. 10.1080/15427609.2021.1935607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, & Posner MI (2000). Cognitive and Emotional Influences in Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Trends Cogn Sci, 4(6), 215–222. 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, & Rothbart MK (1992). Development and Validation of an Early Adolescent Temperament Measure. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 12(2), 153–173. 10.1177/0272431692012002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Trainor RJ, Orendi JL, Schubert AB, Nystrom LE, Giedd JN, Castellanos FX, Haxby JV, Noll DC, Cohen JD, Forman SD, Dahl RE, & Rapoport JL (1997). A Developmental Functional Mri Study of Prefrontal Activation during Performance of a Go-No-Go Task. J Cogn Neurosci, 9(6), 835–847. 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.6.835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassey PJ, Gaut G, Steyvers M, & Brown SD (2016). A Generative Joint Model for Spike Trains and Saccades during Perceptual Decision-Making. Psychon Bull Rev, 23(6), 1757–1778. 10.3758/s13423-016-1056-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, & Kam C-M (2001). A Comparison of Inclusive and Restrictive Strategies in Modern Missing Data Procedures. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 330–351. 10.1037/1082-989x.6.4.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW (1996). Afni: Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res, 29(3), 162–173. 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Chen G, Glen DR, Reynolds RC, & Taylor PA (2017a). Fmri Clustering and False-Positive Rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114(17), E3370–E3371. 10.1073/pnas.1614961114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Chen G, Glen DR, Reynolds RC, & Taylor PA (2017b). Fmri Clustering in Afni: False-Positive Rates Redux. Brain Connect, 7(3), 152–171. 10.1089/brain.2016.0475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G (2014). The New Statistics: Why and How. Psychol Sci, 25(1), 7–29. 10.1177/0956797613504966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (2013). Executive Functions. Annu Rev Psychol, 64, 135–168. 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg IW, Bissett PG, Zeynep Enkavi A, Li J, MacKinnon DP, Marsch LA, & Poldrack RA (2019). Uncovering the Structure of Self-Regulation through Data-Driven Ontology Discovery. Nat Commun, 10(1), 2319. 10.1038/s41467-019-10301-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2022). Applied Missing Data Analysis (2nd Ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enkavi AZ, Eisenberg IW, Bissett PG, Mazza GL, MacKinnon DP, Marsch LA, & Poldrack RA (2019). Large-Scale Analysis of Test-Retest Reliabilities of Self-Regulation Measures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 116(12), 5472–5477. 10.1073/pnas.1818430116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ging-Jehli NR, Ratcliff R, & Arnold LE (2021). Improving Neurocognitive Testing Using Computational Psychiatry-a Systematic Review for Adhd. Psychol Bull, 147(2), 169–231. 10.1037/bul0000319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, & Joormann J (2010). Cognition and Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 6, 285–312. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, & Cumsille PE (2006). Planned Missing Data Designs in Psychological Research. Psychol Methods, 11(4), 323–343. 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist MN, & Wiley JF (2018). Mplusautomation: An R Package for Facilitating Large-Scale Latent Variable Analyses in Mplus. Struct Equ Modeling, 25(4), 621–638. 10.1080/10705511.2017.1402334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote A (2019). Dynamic Models of Choice. In https://osf.io/pbwx8/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Heathcote A, Suraev A, Curley S, Gong Q, Love J, & Michie PT (2015). Decision Processes and the Slowing of Simple Choices in Schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol, 124(4), 961–974. 10.1037/abn0000117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock C, Ratcliff R, McKoon G, Shapiro Z, Weigard A, & Galloway-Long H (2017). Using the Diffusion Model to Explain Cognitive Deficits in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 45(1), 57–68. 10.1007/s10802-016-0151-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull R, Martin RC, Beier ME, Lane D, & Hamilton AC (2008). Executive Function in Older Adults: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Neuropsychology, 22(4), 508–522. 10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalunas SL, Geurts HM, Konrad K, Bender S, & Nigg JT (2014). Annual Research Review: Reaction Time Variability in Adhd and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Measurement and Mechanisms of a Proposed Trans-Diagnostic Phenotype. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 55(6), 685–710. 10.1111/jcpp.12217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karr JE, Areshenkoff CN, Rast P, Hofer SM, Iverson GL, & Garcia-Barrera MA (2018). The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions: A Systematic Review and Re-Analysis of Latent Variable Studies. Psychol Bull, 144(11), 1147–1185. 10.1037/bul0000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR, Russell VA, & Sergeant JA (2013). A Behavioral Neuroenergetics Theory of Adhd. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 37(4), 625–657. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Mychasiuk R, Muhammad A, Li Y, Frost DO, & Gibb R (2012). Experience and the Developing Prefrontal Cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 17186–17193. 10.1073/pnas.1121251109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn S, Schmiedek F, Schott B, Ratcliff R, Heinze HJ, Duzel E, Lindenberger U, & Lovden M (2011). Brain Areas Consistently Linked to Individual Differences in Perceptual Decision-Making in Younger as Well as Older Adults before and after Training. J Cogn Neurosci, 23(9), 2147–2158. 10.1162/jocn.2010.21564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Bull R, & Ho RM (2013). Developmental Changes in Executive Functioning. Child Dev, 84(6), 1933–1953. 10.1111/cdev.12096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerche V, von Krause M, Voss A, Frischkorn GT, Schubert AL, & Hagemann D (2020). Diffusion Modeling and Intelligence: Drift Rates Show Both Domain-General and Domain-Specific Relations with Intelligence. J Exp Psychol Gen, 149(12), 2207–2249. 10.1037/xge0000774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerche V, & Voss A (2017). Retest Reliability of the Parameters of the Ratcliff Diffusion Model. Psychol Res, 81(3), 629–652. 10.1007/s00426-016-0770-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letkiewicz AM, Wakschlag LS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Cochran AL, Wang L, Norton ES, & Shankman SA (2024). Preadolescent Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms Are Differentially Related to Drift-Diffusion Model Parameters and Neural Activation during a Go/No-Go Task. J Psychiatr Res, 178, 405–413. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, & Pleskac TJ (2011). Neural Correlates of Evidence Accumulation in a Perceptual Decision Task. J Neurophysiol, 106(5), 2383–2398. 10.1152/jn.00413.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler C, Frischkorn GT, Hagemann D, Sadus K, & Schubert AL (2024). The Common Factor of Executive Functions Measures Nothing but Speed of Information Uptake. Psychol Res, 88(4), 1092–1114. 10.1007/s00426-023-01924-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, & Burdette JH (2003). An Automated Method for Neuroanatomic and Cytoarchitectonic Atlas-Based Interrogation of Fmri Data Sets. Neuroimage, 19(3), 1233–1239. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna R, Rushe T, & Woodcock KA (2017). Informing the Structure of Executive Function in Children: A Meta-Analysis of Functional Neuroimaging Data. Front Hum Neurosci, 11, 154. 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, & Seidman LJ (2009). Neurocognition in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analytic Review. Neuropsychology, 23(3), 315–336. 10.1037/a0014708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metin B, Roeyers H, Wiersema JR, van der Meere J, & Sonuga-Barke E (2012). A Meta-Analytic Study of Event Rate Effects on Go/No-Go Performance in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 72(12), 990–996. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, & Cohen JD (2001). An Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function. Annu Rev Neurosci, 24(1), 167–202. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, & Wager TD (2000). The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cogn Psychol, 41(1), 49–100. 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (2018). Male Antisocial Behaviour in Adolescence and Beyond. Nat Hum Behav, 2(3), 177–186. 10.1038/s41562-018-0309-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (Eighth Edition ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT (2017). Annual Research Review: On the Relations among Self-Regulation, Self-Control, Executive Functioning, Effortful Control, Cognitive Control, Impulsivity, Risk-Taking, and Inhibition for Developmental Psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 58(4), 361–383. 10.1111/jcpp.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Gustafsson HC, Karalunas SL, Ryabinin P, McWeeney SK, Faraone SV, Mooney MA, Fair DA, & Wilmot B (2018). Working Memory and Vigilance as Multivariate Endophenotypes Related to Common Genetic Risk for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 57(3), 175–182. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RG, Dockree PM, & Kelly SP (2012). A Supramodal Accumulation-to-Bound Signal That Determines Perceptual Decisions in Humans. Nat Neurosci, 15(12), 1729–1735. 10.1038/nn.3248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz B, Rinne T, Mecklinger A, von Cramon DY, & Schroger E (2002). Differential Contribution of Frontal and Temporal Cortices to Auditory Change Detection: Fmri and Erp Results. Neuroimage, 15(1), 167–174. 10.1006/nimg.2001.0970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packwood S, Hodgetts HM, & Tremblay S (2011). A Multiperspective Approach to the Conceptualization of Executive Functions. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 33(4), 456–470. 10.1080/13803395.2010.533157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R (2002). A Diffusion Model Account of Response Time and Accuracy in a Brightness Discrimination Task: Fitting Real Data and Failing to Fit Fake but Plausible Data. Psychon Bull Rev, 9(2), 278–291. 10.3758/bf03196283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Huang-Pollock C, & McKoon G (2018). Modeling Individual Differences in the Go/No-Go Task with a Diffusion Model. Decision (Wash D C), 5(1), 42–62. 10.1037/dec0000065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, & McKoon G (2008). The Diffusion Decision Model: Theory and Data for Two-Choice Decision Tasks. Neural Comput, 20(4), 873–922. 10.1162/neco.2008.12-06-420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, & Rouder JN (1998). Modeling Response Times for Two-Choice Decisions. Psychological Science, 9(5), 347–356. 10.1111/1467-9280.00067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Smith PL, Brown SD, & McKoon G (2016). Diffusion Decision Model: Current Issues and History. Trends Cogn Sci, 20(4), 260–281. 10.1016/j.tics.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, & Brett M (2000). Stereotaxic Display of Brain Lesions. Behav Neurol, 12(4), 191–200. 10.1155/2000/421719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F, Oberauer K, Wilhelm O, Suss HM, & Wittmann WW (2007). Individual Differences in Components of Reaction Time Distributions and Their Relations to Working Memory and Intelligence. J Exp Psychol Gen, 136(3), 414–429. 10.1037/0096-3445.136.3.414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert A-L, Frischkorn G, Hagemann D, & Voss A (2016). Trait Characteristics of Diffusion Model Parameters. Journal of Intelligence, 4(3). 10.3390/jintelligence4030007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, & Greicius MD (2007). Dissociable Intrinsic Connectivity Networks for Salience Processing and Executive Control. J Neurosci, 27(9), 2349–2356. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Mattick RP, Jamadar SD, & Iredale JM (2014). Deficits in Behavioural Inhibition in Substance Abuse and Addiction: A Meta-Analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend, 145, 1–33. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PL, & Ratcliff R (2004). Psychology and Neurobiology of Simple Decisions. Trends Neurosci, 27(3), 161–168. 10.1016/j.tins.2004.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR (2013). Major Depressive Disorder Is Associated with Broad Impairments on Neuropsychological Measures of Executive Function: A Meta-Analysis and Review. Psychol Bull, 139(1), 81–132. 10.1037/a0028727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR, Gulley LD, Bijttebier P, Hartman CA, Oldehinkel AJ, Mezulis A, Young JF, & Hankin BL (2015). Adolescent Emotionality and Effortful Control: Core Latent Constructs and Links to Psychopathology and Functioning. J Pers Soc Psychol, 109(6), 1132–1149. 10.1037/pspp0000047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada C, & Weigard A (2021). Impaired Evidence Accumulation as a Transdiagnostic Vulnerability Factor in Psychopathology. Front Psychiatry, 12, 627179. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.627179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley DJ, & Spence JR (2018). Reproducible Tables in Psychology Using the Apatables Package. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(3), 415–431. 10.1177/2515245918773743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo-Clemmens B, Calabro FJ, Parr AC, Fedor J, Foran W, & Luna B (2023). A Canonical Trajectory of Executive Function Maturation from Adolescence to Adulthood. Nat Commun, 14(1), 6922. 10.1038/s41467-023-42540-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson RC (2025, June 27). Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation as a Formal Model-Based Measure of Task-General Executive Functioning in Adolescents. 10.17605/OSF.IO/8KNUV [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM, Forstmann BU, Love BC, Palmeri TJ, & Van Maanen L (2017). Approaches to Analysis in Model-Based Cognitive Neuroscience. J Math Psychol, 76(B), 65–79. 10.1016/j.jmp.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM, Sederberg PB, Brown SD, & Steyvers M (2013). A Method for Efficiently Sampling from Distributions with Correlated Dimensions. Psychol Methods, 18(3), 368–384. 10.1037/a0032222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F, Aron AR, Band GP, Beste C, Bissett PG, Brockett AT, Brown JW, Chamberlain SR, Chambers CD, Colonius H, Colzato LS, Corneil BD, Coxon JP, Dupuis A, Eagle DM, Garavan H, Greenhouse I, Heathcote A, Huster RJ, Jahfari S, Kenemans JL, Leunissen I, Li CR, Logan GD, Matzke D, Morein-Zamir S, Murthy A, Pare M, Poldrack RA, Ridderinkhof KR, Robbins TW, Roesch M, Rubia K, Schachar RJ, Schall JD, Stock AK, Swann NC, Thakkar KN, van der Molen MW, Vermeylen L, Vink M, Wessel JR, Whelan R, Zandbelt BB, & Boehler CN (2019). A Consensus Guide to Capturing the Ability to Inhibit Actions and Impulsive Behaviors in the Stop-Signal Task. Elife, 8. 10.7554/eLife.46323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, & Clark L (2008). Impulsivity as a Vulnerability Marker for Substance-Use Disorders: Review of Findings from High-Risk Research, Problem Gamblers and Genetic Association Studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 32(4), 777–810. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss A, Nagler M, & Lerche V (2013). Diffusion Models in Experimental Psychology: A Practical Introduction. Exp Psychol, 60(6), 385–402. 10.1027/1618-3169/a000218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigard A, Clark DA, & Sripada C (2021). Cognitive Efficiency Beats Top-down Control as a Reliable Individual Difference Dimension Relevant to Self-Control. Cognition, 215, 104818. 10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigard A, Soules M, Ferris B, Zucker RA, Sripada C, & Heitzeg M (2020). Cognitive Modeling Informs Interpretation of Go/No-Go Task-Related Neural Activations and Their Links to Externalizing Psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging, 5(5), 530–541. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigard A, & Sripada C (2021). Task-General Efficiency of Evidence Accumulation as a Computationally-Defined Neurocognitive Trait: Implications for Clinical Neuroscience. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci, 1(1), 5–15. 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging. Spm12. https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan L, François R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen T, Miller E, Bache S, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel D, Spinu V, Takahashi K, Vaughan D, Wilke C, Woo K, & Yutani H (2019). Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43). 10.21105/joss.01686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]