Abstract

Representatives from academia, industry, regulatory agencies, and patient advocacy groups convened under AASLD and EASL in June 2022 with the primary goal of achieving consensus on chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV) (HDV) treatment endpoints to guide clinical trials aiming to “cure” HBV and HDV. Conference participants reached agreement on some key points. The preferred primary endpoint for phase II/III trials evaluating finite treatments for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is “functional” cure, defined as sustained HBsAg loss and HBV DNA less than lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) 24 weeks off-treatment. An alternate endpoint would be “partial cure” defined as sustained HBsAg level <100 IU/mL and HBV DNA <LLOQ 24 weeks off-treatment. Clinical trials should initially focus on patients with HBeAg-positive or negative chronic hepatitis B, who are treatment-naïve or virally suppressed on nucleos(t)ide analogues. Hepatitis flares may occur during curative therapy and should be promptly investigated and outcomes reported. HBsAg loss would be the preferred endpoint for chronic hepatitis D, but HDV RNA <LLOQ 24 weeks off-treatment is a suitable alternate primary endpoint of phase II/III trials assessing finite strategies. For trials assessing maintenance therapy, the primary endpoint should be HDV RNA <LLOQ assessed at on-treatment week 48. An alternate endpoint would be ≥2 log reduction in HDV RNA combined with normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level. Suitable candidates for phase II/III trials would be treatment-naïve or -experienced patients with quantifiable HDV RNA. Novel biomarkers (HBcrAg, HBV RNA) remain exploratory while nucleos(t)ide analogues and pegylated interferon still have a role in combination with novel agents. Importantly, patient input is encouraged early on in drug development under the FDA/EMA patient-focused drug development programs.

Keywords: Cure, Cirrhosis, Novel therapy, Clinical Outcomes, Biomarkers

Introduction

To promote and facilitate the planning and execution of new clinical trials with the goal of developing finite treatments resulting in “functional cure”, for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) jointly organized a Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Treatment Endpoint Conference in Washington DC on June 3-4, 2022, as a follow-up to similar conferences held in 2016 and 2019. Participants, including representatives from academia, industry, regulatory agencies (US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] and European Medicines Agency [EMA]), International Organizations and patient advocacy groups assembled in Washington DC on June 3-4, 2022.

This report highlights 9 “key questions” addressed in the conference and summarizes the discussions and opinions of experts and patient advocacy groups who attended the 2-day meeting with an emphasis on endpoints, trial design, safety and monitoring for novel therapies aiming to achieve HBV or hepatitis D virus (HDV) “cure”. AASLD and EASL selected the meeting organizers, and the report represents the view of the participants as reported by the authors and reviewed and approved by the speakers and moderators of the conference.

In the context of the emergence of novel therapies, the main goal of the conference was to develop an agreement on HBV and HDV treatment endpoints to guide the design of clinical trials aiming to “cure” chronic HBV and HDV infections. Throughout the meeting, key questions were posed, and the participants discussed the options presented and attempted to reach a consensus. These questions were further explored during a closed session involving 24 experts (including the 4 authors), representing all the stakeholder groups.

Hepatitis B

1. What is the Appropriate Primary Endpoint for Clinical Trials Evaluating New Drugs for Finite Treatment of CHB?

The primary goal of therapy for CHB is to improve survival by preventing cirrhosis, hepatic failure, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver-related death. These clinical endpoints however typically develop over decades and are therefore unfeasible to be used as primary therapeutic endpoints for clinical trials of new investigational agents. Consequently, clinical studies have relied on surrogate markers and shorter-term, intermediate endpoints to substitute for these extended, delayed outcomes. In prior pre- and post-marketing trials, responses have been defined as biochemical (normalization of serum alanine aminotransferase [ALT level]), virological (HBV DNA <lower limit of quantitation [LLOQ]), serological (hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg] loss ± seroconversion to antibody to HBsAg [anti-HBs] and hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg] loss ± seroconversion to antibody to HBeAg [anti-HBe]) and histological (improvement in liver inflammation and fibrosis). Of all these surrogate endpoints, HBsAg loss is considered to be the most relevant because HBsAg seroclearance is associated with sustained off-treatment improvement in clinical outcomes.(1, 2) Additionally, HBsAg loss has been shown to have an additional clinical benefit (lower rates of HCC and hepatic decompensation) over HBV DNA suppression alone, particularly in patients with cirrhosis.(3, 4) Moreover, HBsAg seroclearance is easy to measure with standardized and widely available assays.

Current therapies (pegylated interferon alfa [pegIFNa] and nucleos(t)ide analogues [NAs]) are not curative due to persistence of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), a stable, non-integrated form of viral DNA located in the hepatocyte nucleus, as well as HBV DNA that is directly integrated into the host genome. During acute infection, cccDNA can be silenced and/or degraded through immune mechanisms, however in chronic infection the immune responses are dysfunctional and not easily restored by current treatments. New finite duration therapies are needed, together with a scaling up of existing antiviral treatments, in order to reduce the enormous impact of CHB on global health, with >800,000 deaths annually.(5) Selection of the most appropriate endpoint for clinical trials evaluating new finite therapies is challenging. Some experts have argued for a complete (i.e., sterilizing) cure, whereby all traces of HBV infection would be eliminated, including cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA. This endpoint is currently an unattainably high bar to achieve, as we currently lack therapies that can eliminate both cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA. Moreover, we lack commercial and standardized assays for quantifying cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA. If we cannot safely and easily achieve elimination of cccDNA, the next best goal would be silencing (or degradation) of cccDNA under the premise that this would be associate with complete suppression of HBV replication off-treatment and a lowered risk of hepatitis B disease progression and transmission of new infection to others. At the previous 2016 and 2019 AASLD/EASL endpoints conference, HBsAg loss with or without development of anti-HBs and HBV DNA less than the Lower Limit of Detection (<LLOD) 24 weeks off-treatment was proposed as the definition of functional cure. Also proposed was an alternate but less desirable endpoint of partial cure, defined as HBsAg positive, HBeAg negative with HBV DNA persistently <LLOD, 24 weeks off-treatment. Although long-term sustained off-treatment HBV DNA suppression is associated with similar improvements in clinical outcomes as HBsAg loss, in patients with cirrhosis, it is not reliably durable, and there is a 15-40% lifetime chance of disease reactivation.(6, 7) Therefore, based on expert opinion, the consensus reached previously was that as defined above, functional cure is the preferred primary endpoint for trials evaluating new finite therapies.(1, 2)

Hindering the goal of functional cure as a treatment endpoint is the fact that HBsAg in serum originates from two sources, cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA. Although novel treatments in development may potentially eliminate or silence cccDNA, they may not abolish ongoing RNA transcription from integrated viral genomes, and HBsAg would remain detectable in serum. Thus, until we have therapies that can both eliminate integrated HBV DNA or silence HBsAg transcription and translation from cccDNA and integrated HBV genomes, achieving functional cure, as it is currently defined, may prove difficult. Nonetheless, a sustained seroclearance of HBsAg, (i.e., rendering HBsAg to levels below the currently accepted detection enzyme immune assays, <0.05 IU/ml), plausibly implies profound suppression of replication of HBV, and suggests reduced overall expression from cccDNA and integrated viral genomes.

At the recent June 22nd, 2022, endpoints meeting, various alternative endpoints were discussed, (see Table 1). One proposal was to re-define partial cure to include a biomarker indicative of functional silencing of cccDNA. There was considerable discussion on which marker to include. HBV RNA or hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAg) <LLOQ 24 weeks off-therapy were considered. These are promising research serum markers of cccDNA transcription. However, assays for measuring HBV RNA are not standardized; nonselective assays and primer selection could potentially measure species of HBV RNA or HBV DNA in addition to pregenomic RNA. Several research assays are being developed to detect HBV RNA in patients with low (<3 log10) concentrations of HBV DNA in serum, or in patients receiving long term nucleoside analogue treatment (8) but their sensitivity remains an issue. Similarly, the current chemiluminescent HBcrAg assay may lack sufficient sensitivity to detect ongoing cccDNA transcription in patients with lower levels of HBV DNA in serum. Furthermore, there is no evidence that reductions in HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels are associated with improvement in clinical outcomes. Given these current shortfalls, a definition for partial cure using the more established biomarkers of quantitative HBsAg and HBV DNA (<LLOQ) 24 weeks off-therapy was suggested. Various HBsAg thresholds were considered, ranging from <10, <100 and <1000 IU/mL. A level of <100 IU/mL was chosen as a judicious compromise between the proportion of treated patients reliably achieving this cutoff on treatment with current agents in development, and the known risk-reduction in clinical outcomes, in order to allow the observed increments in development to progress. However, further clinical data are needed to establish that HBsAg decline to <100 IU/ml is a clinically meaningful threshold. The REVEAL data, based on prospective observation of a predominantly untreated HBeAg-negative Asian cohort, demonstrated that lower HBsAg levels were associated with reduced HCC risk suggesting there may be benefit to lowering HBsAg levels.(9) Those with a HBsAg level >100-<1000 IU/mL and ≥1000 IU/mL at entry into the study had a 3.2 and 5.44 fold greater risk respectively, of developing HCC and 1.96 and 3.5-fold greater risk of developing cirrhosis compared to patients with a HBsAg level <100 IU/mL. Also, among HBeAg negative patients with low HBV DNA (<2000 IU/mL), high HBsAg levels >1000 IU/mL were shown to be associated with a 13.7 fold increased risk of developing HCC compared to those with HBsAg levels <1000 IU/mL.(10) A sustained reduction in HBsAg to low levels is thus a potentially clinically meaningful therapeutic endpoint. Whether reducing HBsAg levels through newer treatments, particularly translation inhibitors, emulates natural (immunologically mediated) reductions in HBsAg, and will result in improved clinical outcomes and prognosis for both HBeAg-positive and negative patients, whether these cut-offs are valid in non-Asian populations and for all therapies in development are important questions that require further investigation and confirmation. Another important concern when invoking a definition of partial cure is the durability of response. There is some evidence that low HBsAg levels are associated with a higher chance of achieving both spontaneous and treatment induced HBsAg seroclearance, suggesting perhaps that the presence of lower HBsAg concentrations signals a lower replicative state, and perhaps, the hope, of an improved immunological control of the infection. A recent meta-analysis of 42 studies reported a pooled rate of HBsAg loss after stopping therapy with an end-of-treatment HBsAg level <100 IU/ml of 41.2% (95% CI 30.6–52.7%), compared to 5.8% (95% CI 3.6–9.4%), for those with an end-of-treatment HBsAg level of ≥100 IU/ml, but these predictive cutoffs differ markedly by race and possibly HBV genotype. Among Asians, 33.9% of those with an end-of-treatment HBsAg level of <100 IU/ml experienced subsequent HBsAg loss whereas among Caucasians 34.6% experienced subsequent HBsAg loss with an end-of-treatment HBsAg level of <1000 IU/ml.(5) Studies of agents in development such as small interfering RNA (siRNAs) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) that specifically target all transcripts encoding HBsAg have reported that greater than half to two-thirds of patients can achieve HBsAg levels <100 IU/mL on treatment.(11, 12) Data from the REEF-2 study reported that 15.6% of patients can achieve the revised definition of partial cure (HBV DNA <LLOQ and a HBsAg level <100 IU/mL) 24 weeks off NA and siRNA treatment.(12) Intriguingly, after stopping treatment among HBeAg-negative patients, lower and delayed increases in HBV DNA and fewer ALT “flares” (defined as ALT ≥3X upper limit of normal (ULN)) were observed in patients receiving the siRNA plus a NA compared to the control arm receiving NAs alone: 5% vs. 39%, respectively.(13) The longer term durability needs to be established because of the long half-life of these agents.

Table 1 – Proposed Definitions of HBV Cure and Their Re-definitions.

| VARIABLE | COMPLETE CURE |

FUNCTIONAL CURE Definition 2019 |

FUNCTIONAL CURE Definition 2022 |

PARTIAL CURE Definition 2019 |

PARTIAL CURE Definition 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Positive |

| HBsAg levels, IU/ml | Negative | <LLOQ | <LLOQ | Any | <100 |

| Anti-HBs >10 IU/ml | Positive/Negative | Positive/Negative | Positive/Negative | Negative | Negative |

| HBeAg/anti-HBe | Negative/Positive | Negative/Positive | Negative/Positive | Negative/Positive | Negative/Positive |

| HBV DNA levels, IU/ml | TND | TND | <LLOQ | TND | < LLOQ |

| ALT levels | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| cccDNA | Absent | Present | Present | Present | Present |

| Integrated DNA | Absent | Present | Present | Present | Present |

| Clinical outcomes | Improved | Improved | Improved | Improved | Improved |

| Residual risk of HCC | Very low | Very low | Very low | Low | Very low |

| Durability over time | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Yes |

| Stigma for HBV | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

For all definitions the timing of the endpoint is 24 weeks off-treatment

2022 updates to the definitions are highlighted in bold

HBV DNA may occasionally be detected by sensitive PCR-based assays as “blips” but generally remain <LLOQ (i.e., <10 IU/ml) after HBsAg loss, and therefore the panel recommends using <LLOQ rather than target not detected to define functional and partial cure to allow for occasional transient detection of HBV DNA. The panel continues supporting the recommendation that anti-HBs is not required for definition of functional cure, as HBsAg loss is maintained in over 90% of patients with or without anti-HBs in long-term follow-up with currently approved therapies but will need to be confirmed with therapies in development.(14-16) Thus, although several questions discussed above remain to be answered regarding use of these definitions of functional or partial cure, there was a consensus that functional cure, with the modification of HBV DNA from “TND” to <LLOQ, is still the recommended endpoint for clinical trials evaluating finite therapies for the treatment CHB. The path to HBV cure in most patients is not linear. However positive gains are being observed. In order to allow ongoing advances to progress, partial cure, with our proposed redefinition, and as observed on treatment with current trials, might represent an intermediate endpoint on the path to functional cure. Other endpoints should be explored such as HBsAg <100 IU/mL with HBV DNA around <1000 IU/mL. Years of effort and considerable investment and patient involvement are still required. Although unproven, lowered HBsAg concentrations could improve the effectiveness of the several immune-modulatory strategies in development, given the preliminary observations observed to date with, for example, immune check point inhibitors.

It is important to note that recommendations on the endpoints of therapy will continue to evolve as new therapies able to target viral cccDNA, integrated HBV DNA, HBV RNA destabilization, and host targets are developed.

Recommendations:

The recommended endpoint of novel therapy is functional cure defined as HBsAg loss using a conventional assay for detection of HBsAg (limit of detection 0.05 IU/mL) and HBV DNA below the lower limit of quantification (i.e. < 10 IU/ml) at 24 weeks off-therapy.

An intermediate endpoint on the pathway to functional cure is partial cure, defined as HBsAg <100 IU/ml and HBV DNA below the lower limit of quantification (i.e. < 10 IU/ml) at 24 weeks off- treatment. However, further clinical data are needed to establish that HBsAg decline to <100 IU/ml is a clinically meaningful threshold suitable for use as part of composite clinical trial endpoint.

2. Define the Role of Biomarkers in Phase II/III Studies.

Biomarkers fulfill many roles in CHB. They are used for diagnosis, to assess disease severity and prognosis, to guide treatment decisions, monitor response to therapy and to assess target engagement and efficacy of new agents in clinical trials. A list of the conventional and novel biomarkers and their uses and limitations is provided in Table 2. Tests that detect serum viral antigens (HBsAg and HBeAg), and their respective antibodies (anti-HBs and anti-HBe) are the cornerstone of diagnosis of CHB, which together with HBV DNA and ALT are used to define the phase of infection and to guide need for and response to therapy. HBV genotyping and pre-core and basal core promoter mutation assays are used mainly for epidemiological studies and have a limited clinical role, the one exception being HBV genotyping if pegIFNa is being considered because of better response in genotypes A and B infection compared to C and D.

Table 2: List of available biomarkers, their clinical utility, limitations, and assays for use in CHB.

| HBV Biomarker | Clinical utility | Limitations | Assays Available |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV DNA |

|

|

|

| HBeAg |

|

|

|

| qHBeAg |

|

|

|

| HBsAg |

|

|

|

| qHBsAg |

|

Not widely available particularly in resource limited regions |

|

| Ultrasensitive HBsAg |

|

|

Qualitative

|

| HBsAg isoforms |

|

|

Abbott research use only HBsAg isoform assay |

| HBV RNA |

|

No validated assays Assays cannot distinguish between cccDNA- and intergrated HBV DNA-derived HBV RNA Assays needed to determine the amount of spliced HBV RNA | In-House

|

| HBcrAg |

|

|

CLEIA HBcrAg assay (Fujirebio, Inc.) iTACT-HBcrAg (Fujirebio, Inc.) |

| qanti-HBc | Possible roles

|

Narrow range of quantification |

|

However, conventional biomarkers neither reflect the complexity of CHB nor correlate with viral activity within the liver. Therefore, there is a need for additional biomarkers that not only accurately reflect the amount and transcriptional activity of cccDNA, and burden of HBV integration, but also better characterize the different disease phases and predict risk of complications, particularly HCC. Additionally, biomarkers that can reveal target engagement or a specific mechanism of action of the drug under study will be needed with new antiviral therapies in development. Similarly, immune markers from peripheral compartments (e.g., serum cytokine panels or cellular immune analyses using peripheral blood mononuclear cells) that improve our understanding of the impaired immune response in CHB will be needed for regimens that seek to correct the dysfunctional immune response prevailing at different stages of the disease.

Currently, no single biomarker can serve the diagnostic, monitoring and prognostic roles required for appropriate management of CHB. Therefore, combinations of biomarkers will be needed that can provide information on levels of viral replication (HBV DNA and HBeAg), and transcription from cccDNA versus transcription from integrated viral genomes especially in HBeAg negative patients (levels of HBsAg, HBV RNA or HBcrAg), and the severity of hepatocellular injury (ALT) due to the necro-inflammatory response. In the era of new therapeutics, a panel of biomarkers would allow for better patient stratification within clinical studies and to assess differential and heterogenous responses to therapy. Ultimately, improved biomarker panels may allow precision-based therapies best suited for a given patient to improve chances of achieving functional cure.

To achieve these goals, we need reproducible, well-validated but practical assays that have been evaluated in a broad range of HBV-infected populations, genotypes and across all stages and all therapies. It is equally important that primary endpoints obtained with one assay are confirmed with different commercial versions of the same type of assay. To this end, the panel recommends that the following assays be obtained in all phase II/III clinical studies: qHBsAg, HBeAg/anti-HBe and HBV DNA, to allow for comparison of these different assay results across studies. HBV genotype should be obtained at baseline on all viremic individuals. The following assays can be considered advanced exploratory markers but should be obtained depending on the drug or regimen under investigation: HBV RNA, HBcrAg. These markers of cccDNA transcription can increase during reactivation after cessation of treatment in HBeAg-positive and negative patients, even if not detectable during treatment implying a residual pool of cccDNA. Quantitative HBeAg (qHBeAg) (among HBeAg positive patients only), ultrasensitive quantitative HBsAg (qHBsAg) (LOD <0.005 IU/ml), HBsAg isoforms, quantitative anti- hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), and analyses of immune markers in the peripheral blood are also required. At a minimum, it is recommended that these assays should be measured at start of treatment, on-treatment, end-of-treatment, at defined periods during monitoring after treatment and 24 weeks off-treatment. There should be a commitment to long-term monitoring beyond 24 weeks to assess for durability of response, particularly for agents with prolonged pharmacokinetics e.g., siRNAs and ASOs. The panel recognizes the need for sub-studies that directly examine the intrahepatic compartment by including liver biopsy, fine needle aspirates and analysis of intrahepatic immune responses, relative to the surrogate biomarkers in blood.

Recommendations:

-

3.

qHBsAg, HBeAg/anti-HBe, and HBV DNA should be assessed with every regimen at baseline, on-treatment, end-of-treatment, 24-weeks off-treatment and long-term off-treatment to assess durability of response. HBV genotype should be obtained at baseline on all viremic individuals.

-

4.

The following assays although considered exploratory can add information: quantitative HBeAg (HBeAg+ patients only), quantitative anti-HBc, HBV RNA, HBcrAg, ultrasensitive qHBsAg, HBsAg isoforms, assessment of immune responses in the peripheral blood. The method used for quantitating HBV RNA, and primer selection should be specified.

-

5.

Core liver biopsy for virological measurements (e.g., cccDNA activity, and long read measurement of integrated HBV DNA) and/or FNAs for immunological assessments should be considered in proof-of-concept studies assessing novel therapeutics.

3. Should Novel Agents for Finite Treatment of CHB be Developed in Combination with Approved Therapies NAs and pegIFNa?

Two drug classes are currently approved to treat CHB, pegIFNa and NAs.(17-19) As the only approved class of oral antiviral for CHB and the standard-of-care therapy for a majority of patients, NAs will have an important role to play in combination with novel agents in development because of their potency in inhibiting the production of new HBV DNA containing virions, and their well-characterized long-term safety profiles. However, they are limited to inhibiting late stages of HBV replication, although recent data have suggested a reduction in HBV integration and a slow decline in the pool of cccDNA.(20-22) Additionally, current NAs have low rates of drug resistance, are well-tolerated, affordable for many in high income countries, and widely available. Furthermore, many patients under medical care will already be receiving NAs as long-term therapy. These patients may be an appropriate patient group for enrollment into clinical trials either as controls or in combination with novel agents in development, (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Whether NAs should be included in a novel regimen will partly depend on the mechanism of action of the agents under investigation. Among treatment naïve and virally suppressed populations, NAs can be included as a backbone in combination with novel drugs to suppress viral replication for agents that are not per se potent inhibitors of HBV replication, e.g., siRNAs, ASOs and nucleic acid polymers (NAPs), as well as to limit the emergence of antiviral resistance e.g., with core assembly modulators (CAMs).(23) Preliminary studies have demonstrated that the combination of a CAM and a NA can lead to more rapid and marked suppression of viral replication compared to NA alone. Both CAMs and NAs do not target cccDNA transcription and translation of HBV RNAs from integrated viral genomes, thus, CAMs with NAs have minimal effects on viral HBsAg and HBeAg after 24 weeks of treatment.(24-26) Other additional benefits to using NAs as part of a novel regimen in treatment naïve patients include possibly their (weak) potential to restore HBV-specific T-cell function in-vitro as shown in patients with long term therapeutic HBV DNA suppression(27) and to induce IFN-lambda 3 (IFNL3) (shown for nucleotide analogues) which may contribute to reduction of HBsAg levels.(28) NA withdrawal is being considered as a strategy for achieving functional cure. This is based upon several studies suggesting that NA cessation in HBeAg-negative patients is associated with higher rates of HBsAg loss compared to continuing NA.(29-31) However the results to date have been highly variable. Following NA withdrawal, HBsAg clearance rates have varied between 2.7-16.7% per year in Caucasians but only 0-3.8% per year in Asian populations.(32) Favorable predictors for HBsAg loss are a low pre-withdrawal HBsAg level (<100 to 1000 IU/ml), and Caucasian race (among Asians HBsAg levels associated with HBsAg clearance are lower, <100 IU/mL, compared to Caucasians, <1000 IU/mL).(33, 34)

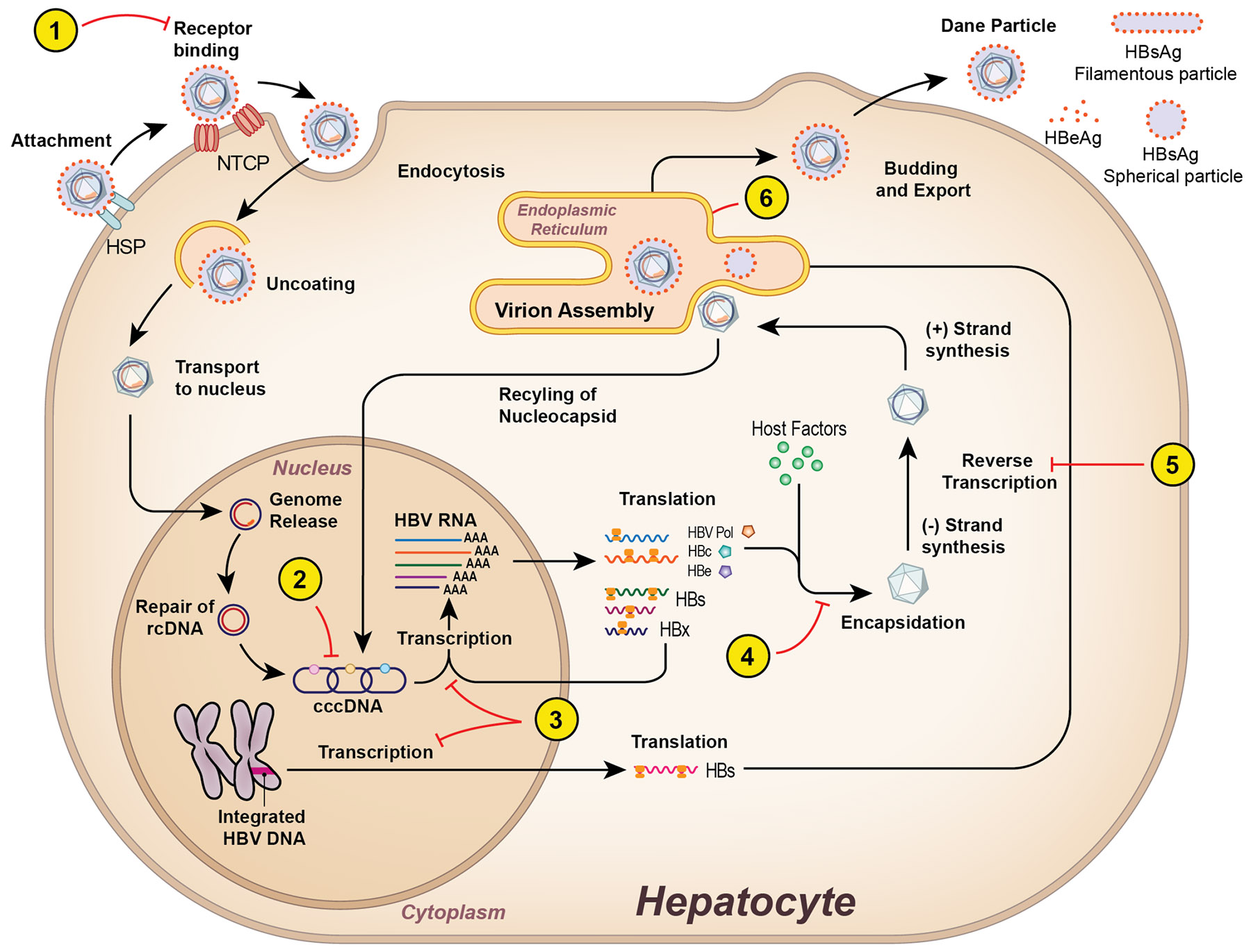

Figure 1:

HBV Life cycle and drug targets. 1) Viral entry inhibitors bind to the NTCP receptor to prevent de novo infection. 2) Inhibition of formation or degradation of cccDNA. 3) siRNA and ASO target and degrade viral transcripts leading to inhibition of viral protein synthesis. 4) CAMs inhibit the formation of the core protein and encapsidation of pre-genomic RNA. 5) NAs target the reverse transcriptase of the HBV polymerase and act as chain terminators of nascent DNA. 6) NAPs prevent secretion of HBsAg. NTCP, sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide; cccDNA, covalently closed circular DNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; ASO, antisense oligonucleotides; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogues; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen

However, the benefits of HBsAg loss must be weighed against the risk of withdrawal flares, hepatic decompensation, and death. Consequently, consensus on rationalizing NA withdrawal is still lacking. At the meeting there was agreement that if NA withdrawal is used as a comparator arm there will be a need to develop clear and stringent stopping rules, close monitoring, and re-treatment algorithms to protect patients given the extensive evidence derived from the REEF-2 study. An unresolved question is whether the disease course after stopping treatment will be similar among individuals with low HBsAg levels achieved by translation inhibition after RNA interference compared to those with low HBsAg levels observed in the natural history of the disease or after NA or pegIFNa treatment.

Historically, a finite course of pegIFNa monotherapy (48 weeks) can result in durable off-treatment HBsAg loss in up to approximately 11% of patients (mostly HBeAg positive) although these results vary by genotype and baseline serum ALT. There has been renewed interest in using pegIFNa in combination with novel agents to achieve functional cure. Leveraging its well-known antiviral and immunomodulatory effects, pegIFNa may provide additional therapeutic benefits in combination with other agents to enhance HBsAg loss. For example, the de novo combination of pegIFNa and NA was demonstrated to have higher rates of HBsAg loss compared to pegIFNa or NA monotherapy after 24 weeks follow up.(35, 36) Studies have also suggested that switching to pegIFNa from NA or adding pegIFNa to NA in selected virally suppressed patients may increase HBsAg loss when compared to continuing NA monotherapy.(37-40)

It is still unclear if these results can be extrapolated to new combination therapies. When combined with novel agents such as CAMs, NAPs, siRNAs, or entry inhibitors, pegIFNa may provide additional antiviral and immunomodulatory effects to enhance HBsAg loss.(41, 42) In a proof-of-concept study and in line with preclinical studies,(43) the combination of NVR 3-778, a first generation CAM, with pegIFNa, resulted in greater reduction in HBV DNA and HBV RNA levels compared to monotherapy with either NVR 3-778 or pegIFNa. However, no significant reduction in HBsAg level was observed during the 4-week treatment period.(44) A recent phase 2 study demonstrated that co-administration of the siRNA VIR-2218 with pegIFNa achieved greater HBsAg seroclearance with anti-HBs seroconversion compared to VIR-2218 alone, 31% (4/13) versus 0% (0/15) at end-of-treatment (week 48).(11) Other studies are currently exploring whether switching to or adding on pegIFNa to these novel agents after achieving a lowered HBsAg and HBV DNA concentration, might optimize the rate of durable HBsAg seroclearance and finite cure.

The timing and duration of pegIFNa in combination with new agents remain important issues that need to be resolved. One approach is to utilize pegIFNa early during therapy to gain synergism in promoting cccDNA silencing(45) and by lowering HBsAg levels. An alternate approach is to first lower HBV DNA and HBsAg levels prior to pegIFNa therapy. The approved duration of pegIFNa is 48 weeks but whether this duration is necessary when combined with new agents is unclear. The panel recommends limiting duration of pegIFNa in clinical trials to ≤24 weeks, and if possible, to a maximum of 12 weeks, as longer durations are less attractive and may pose a challenge for trial recruitment and retention and patients with cirrhosis.

Questions remain as to whether the therapeutic effects of pegIFNa will be similar across HBV genotypes and HBeAg status. It will be important to assess baseline and on-treatment predictors to identify which patients are likely to achieve additional benefit with pegIFNa to limit exposure and maximize benefit. These factors would include baseline ALT, gender, age/duration of HBV infection, HBeAg status, HBV genotype, HBV DNA levels, qHBsAg levels, stage of liver disease, as well as HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels (46) and characterization of the underlying host immune responses.(47) Inclusion of appropriate control arms are recommended to allow for interpretation of results obtained with novel agents.

Recommendations:

-

6.

Depending on the mechanism of actions of the novel agents being evaluated, assessing novel agents in combination with NAs and/or pegIFN as finite treatment may be appropriate.

-

7.

For studies evaluating novel agents in NA suppressed patients, a NA suppressed control arm should be considered. If off-treatment response is a primary endpoint, then NA should be withdrawn from both active treatment and control arms but only if stringent predetermined criteria based on HBsAg levels and other parameters are met to ensure safety.

-

8.

Patients with cirrhosis and those without stable HBeAg sero-conversion should not be considered for NA withdrawal studies.

-

9.

For studies using pegIFNa of any duration, a pegIFNa monotherapy arm should be included as a control arm.

4. Management of On- and Off-treatment ALT Flares and Virological Rebound

An acute elevation in serum ALT level or ALT flare may occur periodically during the natural course of infection and during treatment with pegIFNa and NAs. Although most ALT flares are thought to represent a host immune response against HBV infected hepatocytes, ALT flares are a concern with novel therapies because of their potential to worsen underlying liver injury or lead to hepatic decompensation with unclear management approaches to these events. Depending on the mechanism of action of novel therapies, ALT flares may be: 1) immune mediated, such as an agent that directly or indirectly augments the host immune recognition e.g. immune-mediated hepatitis by immune checkpoint inhibitors and destruction of HBV-infected hepatocytes, including a host cytolytic response after a rapid decrease of viral replication and HBV antigen expression 2) virally mediated due to an increase in viral replication and renewed intrahepatic viral spreading that might occur in the setting of viral escape, reactivation or resistance to an antiviral agent, e.g. a CAM, or in the setting of NA discontinuation before HBsAg loss and 3) drug-induced liver injury (DILI) due to direct or indirect hepatotoxicity of the study drug e.g. CAM and Inarigivir.

Defining what constitutes an ALT flare in a patient with CHB can sometimes be difficult because of variable baseline ALT, HBV antigen and HBV DNA levels. Consequently, two definitions of an ALT flare are proposed. For subjects with a previously normal ALT, a rise in ALT to >5X ULN and for subjects with an elevated ALT pre-treatment, an elevation in ALT >3X pre-treatment are defined as ALT flares.(1)

Management is guided by the etiology and severity of the flare, Figure 2. In most cases the etiology of the flare can be established based on clinical presentation and virological tests. Rarely, a liver biopsy may be necessary. In severe flares, defined by an elevated serum total bilirubin, prolongation of the prothrombin time, mental status changes or hepatic decompensation, the investigational agent should be stopped immediately, and the patient referred to a center with experience in managing acute liver failure with liver transplantation capabilities. In mild or moderate flares (ALT <5X ULN), it is imperative that patients are monitored more frequently (weekly to fortnightly with unscheduled visits) until resolution. Whether the investigational agent should be stopped or continued would depend on the pathogenesis of the flare and risk of hepatic decompensation. Clinical trial protocols evaluating new HBV therapies should include clear and detailed plans for how ALT flares should be managed. Flares that occur in patients who are virally suppressed with reduced HBsAg concentrations are likely DILI-related, immune, or autoimmune in nature. Drug re-challenge in the setting of immune or autoimmune-related flares should be avoided because of risk of greater severity with repeat exposure. Management of auto-immune flares may require additional therapy e.g., corticosteroids and addition of a NA if not already being used. Flares associated with a rise in HBV DNA likely signify antiviral breakthrough and consideration should be given to instituting rescue antiviral therapy. Finally, it is important to note that an ALT flare may occur due to viral rebound following cessation of an investigational agent (withdrawal flare). There has been one report of acute liver failure requiring liver transplantation, following withdrawal of NAs in a clinical trial.(48) Therefore, it is important that patients be carefully monitored for HBV DNA and ALT levels every 2-4 weeks for 6 months and every 3 months, thereafter, after stopping therapy given the unpredictable outcome of severe flares and the capacity of hepatic regeneration. One study reported that the slope of increase in HBV DNA was an important factor preceding ALT flares.(49) Therefore, it was proposed to restart NAs for an increase in HBV DNA to a concentration of 4 log10, irrespective of ALT levels to mitigate the onset of severe liver injury.(49) Based on these observations, clinical trials that include HBV treatment cessation should prespecify detailed plans and criteria for reinitiating HBV treatments for withdrawal flares. These criteria should be tailored to the agents and patient populations being studied. Early re-treatment of ALT flares may be associated with a lower rate of HBsAg clearance.(34). However recent data from the control, NA only arm of REEF-2 indicate that NA withdrawal is of limited efficacy and is an uncertain primary cure strategy to promote HBsAg loss going forward for most patients.

Figure 2:

Algorithm for investigation and management of ALT flares during conduct of trials of investigational agents

Recommendations

-

9.

The specific criteria for defining, monitoring, and managing hepatitis flares during treatment and after stopping therapy should be prespecified in the clinical trial protocols evaluating novel agents. Appropriate investigations to determine the etiology of an ALT flare are warranted and details of their course and outcome should be reported.

-

10.

In studies of treatment withdrawal, HBV DNA and ALT levels should be frequently monitored during the first 6-12 months. Clinical trials that include HBV treatment cessation should prespecify detailed plans and criteria for reinitiating HBV treatments for withdrawal flares. These criteria should be tailored to the agents and patient populations being studied.

5. Which Patient Populations to Enroll in Phase II/III Studies and Need for Control Arms?

Patient Populations

A key issue that was discussed at the meeting was prioritizing patient populations for enrollment in phase II/III studies of novel therapies. There was general agreement that HBeAg positive and negative patients with immune active disease (HBeAg positive and HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis) without cirrhosis should be the focus of early phase studies. Some favored enrolling HBeAg positive and negative patients separately while others believed both HBeAg positive and negative patients could be included in the same study arm if enrollment and analyses were balanced by HBeAg status. Both treatment-naïve and -experienced patients are appropriate for inclusion in clinical trials but should be stratified and analyzed separately. There was consensus that patients with cirrhosis should be excluded in early phase studies but should be included in phase 2b studies and additional pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies conducted in this population. Table 4a includes a list of special populations that should be considered for new therapeutic trials in HBV.

Table 4a -. Special Populations for Inclusion in Therapeutic Trials for CHB.

| Grey Zone patients |

| Immune tolerant (HBeAg positive chronic infection) |

| Inactive carrier (HBeAg negative chronic infection) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis |

| Children/adolescents |

| Acute HBV infection |

| HBV recurrence after liver transplantation |

| HIV/HBV coinfection |

Populations of Special Interest

The Panel recommends that clinical trials be specifically designed to study “immunotolerant” patients, or HBeAg positive chronic infection (defined as HBeAg positive with HBV DNA >6 log IU/mL and ALT <ULN) and “inactive carrier” or HBeAg negative chronic infection (defined as HBeAg negative with HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL and ALT <ULN)) patients.(18, 19) A key challenge will be a prerequisite to demonstrate improved prognosis after achieving functional cure, given the low short-term rate of clinical outcomes in these two populations. Reducing the ultimate HCC risk and infectivity as well as reducing stigma from CHB may be potential ancillary benefits of functional cure in the immunotolerant population. However, achieving functional cure among the immunotolerant population may be particularly challenging because of the very high baseline viral load and HBsAg levels. Studies of NAs alone and in combination with pegIFNa have been disappointing in achieving HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion.(50, 51) Nonetheless recent studies have shown the effect of aging on progressive immunological impairment in CHB, advocating for earlier treatment of this young cohort.(52) Conversely natural history studies report low rates of cirrhosis and HCC among inactive carriers (HBeAg negative chronic infection).(6, 53, 54) An argument can be made for treating this latter population, despite their relatively inactive disease, to induce functional cure because of a 15-20% long-term risk of transition to (immune) active disease.(6, 7) The lower levels of HBsAg and evidence of virological and immunological control at baseline may be advantages to evaluating new therapeutics aimed to achieve functional cure in patients with low replicative states (“inactive carriers”) in this population.

There has also been interest in enrolling patients classified as “grey-zone ” or “indeterminate” into clinical trials. These are patients who cannot be classified into one of the 4 phases of chronic infection. They represent a heterogenous population consisting of HBeAg negative with low viral load (HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL) but elevated ALT levels (likely representing inactive carriers with other causes of liver disease),(55) and HBeAg negative patients with moderately high viral loads (HBV DNA >2000 IU/mL but normal or mildly elevated (<2X ULN) ALT levels.(55, 56) Newer biomarkers estimating cccDNA transcription could refine the phenotype in these populations and aid in determining need for therapy.

Study design

The Panel recommends two different strategic approaches for design of phase 2 studies: 1) adaptive trial designs whereby, multiple studies of small sample size but very well characterized patients, are enrolled and multiple regimens and dose ranges are evaluated in parallel and non-efficacious arms are rapidly discontinued and patients shuttled to better performing arms (57) and 2) large scale studies (>200-300 patients) in which pre-defined exploratory analyses can be performed. In general, superiority trials are recommended over non-inferiority trials, but the choice may depend on the regimen under consideration and whether finite versus maintenance therapy is the intended goal. Should a non-inferiority trial design be considered, it is important that it is adequately powered to allow statistical comparisons with the control arm and for key secondary analyses. Consideration should be given to controlling for variables that may affect treatment outcome including age, HBeAg status, baseline HBV DNA and qHBsAg levels, disease severity (presence/absence of cirrhosis), treatment history, HBV genotype or race. It is recommended to continue to follow participants in clinical trials beyond 24-48 weeks off-treatment to establish durability of response and long-term outcomes. For studies evaluating pegIFNa for >24 weeks as de novo combination therapy, add-on or sequential strategies, a pegIFNa monotherapy arm, is recommended. For studies in which NA will be withdrawn, consideration should be given to stratify for duration of NA treatment and to collect data on "disease activity" markers prior to NA treatment, i.e., HBV DNA levels, ALT and HBsAg levels, and estimated duration of infection prior to initial therapy, if applicable.

Control arms

Whether a control arm is necessary for early phase studies and which population should serve as controls in particular studies remain unresolved issues. An active treatment control arm is recommended in phase IIa studies; for studies assessing short-term administration of new compounds, i.e., <24 weeks, it may be ethical to include an untreated control group, provided that these patients have later access to treatment. Use of untreated controls would provide valuable safety information on new agents in development. For studies assessing the efficacy and safety of add-on strategies in NA suppressed patients, a NA control group is recommended to facilitate evaluation of safety and off-treatment endpoints. However, appropriate monitoring and treatment re-initiation algorithms should be in place if NA is withdrawn. For studies conducted in populations for whom treatment is not currently indicated, HBeAg positive and negative chronic infection and greyzone patients it may be ethical to include untreated controls. A control arm should be included in phase III registration trials.

Recommendation:

-

11.

HBeAg positive and HBeAg negative patients with immune active disease without cirrhosis are appropriate candidates for Phase II and III studies.

-

12.

For studies enrolling immune active HBeAg positive and HBeAg negative patients, a control group should include standard of care.

-

13.

For studies enrolling immunetolerant, inactive carriers and greyzone patients, it is appropriate to consider a placebo arm.

-

14.

Variables to consider for patient stratification include baseline quantitative HBsAg and HBV DNA levels, HBeAg status, cirrhosis, treatment history, HBV genotype/race.

-

15.

Both superiority and non-inferiority trial designs may be employed but will require different endpoints.

Hepatitis D

6. Which is the appropriate primary endpoint for new drugs in development for CHD?

The goal of HDV therapy is to improve patient survival by preventing disease progression, particularly development of cirrhosis, decompensation, HCC, and liver-related death. Cure of HDV remains difficult, because both HBsAg seroclearance and suppression of HDV replication and propagation are required for most. The long-term clinical endpoints are difficult to measure in both clinical trials and real-life studies because of the need for lengthy follow-up. Hence, surrogate endpoints such as HBsAg clearance and HDV RNA <LLOQ on- or off-therapy have been proposed (Table 3). These endpoints have been utilized in untreated and interferon-alfa (IFNa) treated patients, and demonstrated that patients who achieve these endpoints have a lower risk of disease progression.(58) Several studies, have reported that, sustained suppression of HDV RNA (undetectable or <LLOQ) off-treatment was associated with an increased rate of HBsAg loss and with a lower incidence of adverse clinical events compared to patients with detectable or >LLOQ HDV RNA, although statistical significance was not reached due to the small number of patients achieving this endpoint and low rate of clinical events.(59, 60) Additionally, an association between undetectable/<LLOQ HDV RNA levels 24 weeks off-treatment and improvement in clinical outcomes was observed in two non-randomized cohort studies and in the 10-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of pegIFNa (HIDIT-1).(58, 61, 62) HDV RNA <LLOQ at 24 weeks off therapy is not a robust endpoint because of late virologic relapses occurring in approximately 50% of these patients.(63)

Table 3-. Primary and Secondary Endpoints for Therapeutic Studies in Patients with CHD.

| TYPE OF RESPONSE |

DEFINITION | FINITE (SHORT-TERM )THERAPY (≤ 48 WEEKS) |

MAINTENANCE (LONG-TERM) THERAPY (> 48 WEEKS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-therapy (24 weeks) |

On-therapy (48 weeks) |

||

| Complete Virological | HDV RNA < LLOQ | Yes^ | Yes# |

| Partial Virological | ≧ 2 log IU/ml decline of HDV RNA vs baseline | NA | Yes |

| Biochemical | Normal ALT | Yes | Yes |

| Combined | ≥ 2 log IU/ml decline of HDV RNA compared to baseline and normal ALT | NA | Yes! |

| Serological | HBsAg loss±anti-HBs | Yes* | Yes/No |

| Histological | Improvement of necroinflammation and fibrosis | Yes | Yes |

Primary endpoint for studies with a finite duration strategy

Alternate endpoint for studies with a finite duration strategy

Primary endpoint for studies with a maintenance strategy

Alternate endpoint for studies with a maintenance strategy

Despite these weaknesses in the evidence, the absence of alternate biomarkers support the use of HBsAg loss and HDV RNA <LLOQ as endpoints to assess new treatments in development for CHD. For drugs being developed for a finite duration of therapy, the preferred endpoint is HBsAg loss ± anti-HBs seroconversion, which should be associated with HDVRNA <LLOQ. In the absence of HBsAg loss, an alternate endpoint is HDV RNA <LLOQ at 24 weeks off-treatment. However for drugs being developed for maintenance therapy, the preferred endpoint is HDV RNA <LLOQ at 48 weeks on-treatment.(64) If this endpoint is not achievable, as is currently the case for most treatment regimens then an intermediate endpoint that will allow ongoing drug development for CHD is >2 log decline in HDV RNA combined with normal ALT levels, termed “combined response”.(65) Indeed, this latter endpoint was used in the phase II clinical studies of bulevirtide leading to its conditional approval by the EMA (66) and is being used in the phase III trials of lonafarnib and bulevirtide. An international expert panel proposed using a combined response criteria,(65) based on the long-term clinical results of nine patients enrolled in a trial using high-dose IFN-alfa compared to untreated controls.(67) However, the study was performed in the 1990s with HDV RNA assays that were not standardized and lacked sensitivity. In a more recent study with a relatively small number of patients who were followed for 8 years, HDV RNA decline of >2 log10 IU/mL was not associated with better outcomes; however, the number of patients who achieved outcomes was low.(68) In two small cohorts of patients from Italy and Austria in patients with compensated cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) treatment with bulevirtide for 48 weeks led to a reduction in severity of portal hypertension.(69) In both studies, the results are too preliminary to establish whether these improvements were attributable to reduction in HDV viremia and requires additional confirmatory studies.

Several questions remain unanswered regarding the proposed endpoints of maintenance studies. What is the appropriate timepoint to assess an on-treatment combined endpoint and how often should it be reassessed? What is the risk of virological relapse on maintenance treatment and can clinical improvement be expected? Is there any difference in clinical outcome between patients with HDV RNA <LLOQ and those with only a 2-log decline and ongoing detectable viremia? Is the relative or absolute decline in HDV RNA pivotal to clinical improvement? For example, the clinical outcomes could differ in patients with very high baseline HDV RNA achieving a 2-log decline to for example 104 to 105 IU/mL versus patients who reach levels of 103 IU/mL or lower. Why in some studies is there a dichotomy between the decline in viremia and improvement in serum aminotransferase concentrations? The impact of persistently low HDV RNA, as well as the impact of therapies on intrahepatic changes (HDV RNA and HDAg levels) should also be assessed in clinical trials when investigating clinical endpoints.

In conclusion, for studies of finite treatment duration, the preferred primary endpoint is HBsAg loss and/or HDV RNA <LLOQ24 weeks off-therapy. For studies of maintenance therapy, the preferred primary endpoint is HDV RNA <LLOQ at 48 weeks on treatment. Further studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of this endpoint.

Recommendations:

For Finite Strategies:

-

16.

The preferred endpoint for novel anti-HDV therapies is HBsAg loss ± anti-HBs seroconversion and HDV RNA below the lower limit of quantification

-

17.

In the absence of HBsAg loss, an alternate endpoint is HDV RNA below the lower limit of quantification at 24 weeks off-treatment. There should be a commitment to long-term follow-up (minimum 5 years) to assess durability of this endpoint.

For Maintenance Strategies:

-

18.

The preferred endpoint of a maintenance strategy is HDV RNA below the lower limit of quantification at 48 weeks on-treatment that is maintained on-treatment. The optimal duration of maintenance therapy is currently unknown.

-

19.

If this is not achievable, an alternate endpoint is combined response defined as HDV RNA >2 log decrease from baseline and normal ALT level at 48 weeks on-treatment and during the follow-up on treatment. The optimal duration of maintenance therapy is currently unknown.

7. Define the role of Biomarkers in Phase II/III Studies.

Biomarkers serve a similar role in CHD as in CHB. In phase II and III studies aiming to assess the safety and efficacy of new compounds for CHD, the most relevant biomarkers are quantitative HBsAg and HDV RNA levels and the correlation between these markers, and further supported with improvement in serum ALT and if biopsies are performed, an improvement in necroinflammation and fibrosis and a reduction in immunohistochemical staining for HDAg. The panel recommends reporting the results of these two markers at timepoints on- as well as off-therapy. As the preferred endpoint of finite treatment strategies is loss of HBsAg, standardized, validated, commercially available assays should be used to report qualitative and quantitative HBsAg levels.

Similarly, measurement of HDV RNA levels should be performed using validated assays that are commercially available. Ideally, quantitative assays should be reproducible across all HDV genotypes. RNA extraction methodologies during quantitation of HDV RNA are critical factors influencing the results. HDV RNA levels should be expressed as IU/ml. The clinical relevance of “target not detected” compared to <LLOQ for HDV RNA levels is currently unknown. Since HDV RNA levels may sometimes fluctuate between these two results, the panel recommends using <LLOQ as the endpoint of clinical trials and providing the limit of detection and quantification of the assay used. This would allow for comparison of results with different assays and different regimens and resolving minor blips in HDV RNA levels that are probably of no clinical consequence. HDV genotype should be determined pre-therapy in all patients. Standard HBV specific markers such as HBeAg/anti-HBe status and HBV DNA levels should be collected at timepoints, before, during and after therapy.

The role of exploratory markers specific to HDV such as quantification of total anti-HDV and quantification of HDV RNA by digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) deserve further investigation. Similarly, exploratory HBV biomarkers such as HBcrAg and HBV RNA should be collected in all HDV studies. The clinical utility of other HBV biomarkers such as HBsAg isoforms, HBsAg/anti-HBs complexes, supersensitive HBsAg levels and quantification of anti-HBc should be explored in specific subpopulations of patients. HBV and HDV genotype should be determined pre-therapy in all patients entering a clinical trial for HDV, if HBV DNA levels permit assessment of genotype. Sub-studies to estimate intrahepatic levels of HDV RNA and HDAg will be fundamental in early trials to evaluate decline in intrahepatic viral markers. These studies may help define treatment duration and inform design of other trials with the goal of achieving HDV clearance. The complex immune response to coinfection differs from mono-infection and further research studies are needed.

Recommendations

-

20.

HDV RNA, HBV DNA, HBeAg and qHBsAg should be obtained at baseline, on-treatment, end-of-treatment, 24 weeks off treatment. Long-term off-treatment follow-up should be reported.

-

21.

HDV genotyping should be obtained pre-treatment in all studies and HBV genotypes if possible.

-

22.

Serum qHBeAg (HBeAg positive patients only), HBcrAg, HBV RNA, ultrasensitive qHBsAg, q anti-HBc and intrahepatic (HDV RNA and HDAg) as well as peripheral immune are considered exploratory.

8. Which Patient Populations to Enroll in Phase II/III Studies?

Patient Populations

Treatment-naïve or -experienced patients with CHD, defined by quantifiable HDV RNA in serum independent of ALT levels, are candidates for phase II and III studies. The inclusion of patients with compensated cirrhosis with or without CSPH should be carefully assessed on a study-by-study basis. The decision to include this patient group will depend on the mechanism of action and safety profile of the compound under evaluation, the study design, and duration of treatment (finite vs maintenance long-term therapy) Patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be excluded from early phase studies and only considered once the safety and efficacy of the drugs have been established in CHD patients without and with compensated cirrhosis. Consideration must be given to possible deleterious effects and frequency of HDV relapse after cessation of treatment.

The role of NA therapy in CHD is controversial. In general, CHD patients have low levels of HBV replication. Use of NAs in HDV trials assessing new therapeutics may avoid or reduce the risk of an increase in HBV replication following inhibition of HDV replication, thus simplifying the evaluation of ALT flares in the post-treatment follow-up. Table 4b includes a list of special populations that should be considered for new therapeutic trials in HDV.

Table 4b -. Special Populations for Inclusion in Therapeutic Trials for CHD.

| Treatment-experienced patients (PegIFNa, Bulevirtide, Lornafarnib+ritonavir) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis |

| Children/adolescents |

| Acute HDV infection |

| HDV recurrence after liver transplantation |

| HDV genotype non-1 infection |

| HIV/HDV coinfection |

Study Design

In general recommendations for trial designs are similar to that of CHB (see section 5). The inclusion in early phase trials assessing maintenance therapy of patients with low HDV RNA levels <500 IU/ml, and normal ALT levels could be problematic if ≥ 2 log decline compared to baseline with ALT normalization (combined response) is used as the primary endpoint. Consideration should be given to stratification of baseline factors that may affect study outcome and response to treatment such as HDV RNA levels, HDV genotype, HBsAg and HBV DNA levels, HBeAg status, possibly HBV genotype and fibrosis stage. For phase II and III clinical trials, the panel recommends the inclusion of an untreated control group only if these patients will remain without active treatment for a limited period (≤24 weeks) and only if active treatment will be offered at the end of the study if the study drug has been proven safe and efficacious. Since the conditional approval of bulevirtide, regulatory authorities may require an active control group. Indeed, the likelihood of achieving HDV RNA <LLOQ or ≥2 log decline compared to baseline with ALT normalization (combined response) for untreated CHD patients is very low.(70) There should be a commitment to collect long-term off- or on-therapy clinical data and outcomes.

Recommendations

-

23.

Treatment-naïve or -experienced adult patients with CHD (HDV RNA quantifiable for 6 months) regardless of ALT level are candidates for phase II/III studies.

-

24.

The inclusion of patients with both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis must be carefully considered based on the mechanism of action and preliminary safety and efficacy data of phase II studies.

-

25.

NA therapy for HBV should be considered in all CHD patients enrolled in Phase II and III studies.

For HBV and HDV

9. How do we incorporate and prioritize the patient perspective and experience in conduct of trials undertaken by pharma, funding agencies for FDA/EMA, and other regulatory agencies?

There is an increasing recognition of the critical role of a patient-focused approach in drug development (Figure 2). Patient engagement adds value to the regulatory process of medicinal products through the development of therapeutic options that better embody patient needs and priorities. The valuable insights of those living with CHB can guide the development of treatment endpoints and drug development with the ultimate goals of improving patient quality of life, treatment adherence and outcomes and reducing stigma. During the HBV/HDV Endpoints Meeting, patient advocacy groups were invited to share their insights regarding the patient perspective and preference in drug development. This included the impact of CHB on their lives, their experience with current medications and their preferences and tolerance to new agents, route of administration and duration of therapy.

Patient-centered clinical trials and drug development should include patient experience data (PED) as defined in Title 2I, section 3001 of the 21st Century Cures Act, and amended by section 605 of the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (FDARA).(71) This includes data collected by any person and are intended to provide information about patients’ experiences with a disease or condition. PED captures the patient’s experience, perspective, needs, and priorities relating to 1) Symptoms of their condition and their natural history; 2) Impact of their condition on their functional status and quality of life (QOL); 3) Experience with treatments; 4) Input on what outcomes are important to them; 5) Preferences for outcomes and treatments 6) Any important issues defined by patients.(72) (Table 5)

Table 5. The Benefits of Patient Engagement in Drug Development.

| Promotes the development of treatment options that better represent patient needs and priorities |

| Provides direct input from patients, families, caregiver, and patient advocates on: a) symptoms that matter most to them; b) impact the disease on patient’s lives; c) patient experiences with currently available treatments |

| Identifies impacts and concepts from patients with development of potential study instruments that can be incorporated into drug trial to evaluate for clinical benefit |

| Ensures that investigations of the effects of treatments are evaluating outcomes that are meaningful to patients |

| Provides better understanding of the clinical context for drug development and evaluation |

| Informs the selection of clinical outcomes and ensures the appropriateness of instruments used to collect trial data |

| Guides product design such as formulation and delivery modes that minimize burden and optimize adherence |

| Develops endpoints that represent benefits that matter most to patients including type of adverse event endpoints |

| Designs trials that optimize enrollment/retention and ensures adequate recruitment reflecting diversity and heterogeneity to accurately reflect target population |

| Informs industry and regulatory decision-making regarding patient acceptability of benefits vs. risks vs. tolerability concerns, and effective risk management |

Both the FDA and EMA are committed to patient engagement in the regulatory process of drug development, to promote patient-focused medicinal product development while at the same time improving transparency and trust in the regulatory system. To this end, both regulatory agencies have developed patient-focused drug development programs and initiatives. The FDA has published a series of four methodological patient-focused drug development (PFDD) guidance documents to address, in a stepwise manner, how stakeholders can collect and submit PED and other relevant information from patients and caregivers for medical product development and regulatory decision making.(73) An example of an externally led PFDD was one initiated by the Hepatitis B Foundation in June 2020 in collaboration with the FDA. With over 650 participants, testimonies from 12 people living with HBV, and over 300 comments from around the world, much patient experienced data was gleaned to advocate for patient-focused drug development and clinical trials. The EMA published the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) reflection paper on patient-focused drug development in June 2021.(72) This paper identifies key areas where incorporation of the patient’s perspective could improve the quality, relevance, safety and efficiency of drug development and regularly inform decision making. EMA also participates in the IMI PREFER (Innovative medicines initiative/ Patient Preferences in benefit risk assessments during the drug life cycle) which provides a set of systematic methodologies and recommendations to assess, engage and include patient perspectives during the development, approval and post-approval of new therapies (http://www.imi-prefer.eu/about/.)

Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs), considered part of the PED, should be incorporated in the assessment of CHB patients in clinical trials or natural history studies. For a PRO to be disease specific and a patient centered outcome measure, it must capture a concept(s) that patients identify as being highly important to them. PROs have been used to assess QOL impairments in viremic patients (HBV and HCV, HDV vs. HBV mono-infection), as well as the long-term effects of treatment in virally suppressed CHB patients.(74-76) In addition, the development of specific PRO instruments for HBV such as the HBV-specific health-related quality-of-life instruments have shown initial validity and responsiveness.(77) The incorporation of HBV-specific PROs will add further value to drug development by bridging the efficacy-effectiveness gap, thereby, providing the connection between efficacy outcomes and meaningful change in the real-world clinical context.

Lastly, a new paradigm in clinical trials, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, is emerging with a shift towards patient centricity, which provides opportunity to optimize patient engagement and input. This involves the adoption of a decentralized approach to clinical trials and clinical trial design utilizing virtual engagement technology.(78) The benefits of such virtual trials can improve the patient and physician experience and their participation. For example, a decentralized format would involve consultation with advocacy groups and trial activities that could be conducted remotely or in the patient’s home. By optimizing patient engagement, this can lead to higher, faster recruitment and retention in clinical trials. This can also capture a more diverse and real-world representation of patient groups, thus ensuring adequate representation of previously under-represented patient populations. Ultimately, this can produce higher quality data and can expedite the development and review of novel medicinal products. There is an urgent need to include patients from sub-Saharan African region in new clinical trials as they are severely under-represented group in current trials.

Recommendations:

-

25.

Metrics using validated instruments to incorporate patient experience data (PED), including patient preference information (PPI) and patient reported outcomes (PROs), should be included early in the drug development process, and reported as secondary endpoints.

-

26.

New virtual technology platforms may be considered to optimize the collection of patient focused experience data in addition to data in clinic trials.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3:

HDV life cycle and drug targets. Bulevirtide (BLV) blocks de novo infection by binding to the NTCP receptor. Lonafarnib (LNF) impairs HDV assembly and secretion by inhibiting farnesyl transferase which is required for prenylation of L-HDAg. IFNα and IFNλ profoundly suppress HDV amplification during cell division by inducing IFN stimulated genes (ISGs). NAPs selectively block assembly and secretion of subviral HBsAg particles and/or HDV ribonucleoprotein assembly. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; IFN, interferon; L-HDAg, large hepatitis D antigen; NAP, nucleic acid polymer, NTCP, sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide; S-HBsAg, small hepatitis B surface antigen.

Figure 4:

The patient focused approach in drug development and the clinical trial continuum

1. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/selected-amendments-fdc-act/21st-century-cures-act. Last accessed October 28th, 2022.

2. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cdrh-patient-science-and-engagement-program/patient-preference-information-ppi-medical-device-decision-making. Last accessed Nov 23,2022.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the following participants (alphabetical order) for their helpful discussion in the closed-door session:

1. Michael Biermer – Johnson and Johnson

2. Stephanie Buccholz – EMA

3. Maria Buti, EASL

4. Gavin Cloherty, Abbott Diagnostics

5. Joyeta Das – GlaxoSmithKline

6. Eric Donaldson, FDA

7. Geoffrey Dusheiko EASL

2. John Flaherty Gilead Science

3. Marc Ghany, AASLD

4. Pietro Lampertico, EASL

5. Audrey Lau – Vir Biotechnology

6. Hannah Lee, AASLD

7. Anna Lok, AASLD

8. Gaston Picchio, Arbutus

9. Virginia Sheikh – FDA

10. Norah Terrault, AASLD

11. Andrew Vaillant, Replicor Inc

12. Cynthia Wat, Roche

Financial support and sponsorship:

Marc G. Ghany was supported by the Intramural Research Program, NIDDK.

List of Abbreviations:

- CHB

chronic hepatitis B

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- HBV

Hepatitis B Virus

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- HDV

hepatitis D virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantitation

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- anti-HBs

antibody

- HBeAg

hepatitis B e antigen

- anti-HBe

antibody to HBeAg

- pegIFNa

pegylated interferon alfa

- NA

nucleos(t)ide analogue

- cccDNA

covalently closed circular DNA

- LLOD

Lower Limit of Detection

- HBcrAg

hepatitis B core-related antigen

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotides

- NAPs

nucleic acid polymers

- CAM

core assembly modulator

- IFNL3

IFN-lambda 3

- DILI

drug-induced liver injury

- CSPH

clinically significant portal hypertension

- ddPCR

digital droplet PCR

- FDARA

FDA Reauthorization Act

- PED

patient experience data

- QOL

quality of life

- PFDD

patient-focused drug development

- ICH

International Council for Harmonization

- IMI

Innovative medicines initiative

- PRO

Patient Reported Outcomes

AASLD-EASL HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference Faculty (In Alphabetical order)

Thomas Berg (Division of Hepatology, Department of Medicine II, Leipzig University Medical Center, Leipzig, Germany)

Maurizia R. Brunetto (Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa and Hepatology Unit, University Hospital of Pisa, Italy)

Stephanie Buchholz (Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, BfArM, Bonn, Germany)*

Maria Buti (Liver Unit, Hospital Universitario Valle Hebron. Barcelona 08021)

Kyong-Mi Chang (Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine; Medical Research, The Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA)

Jacki Chen (Department of Pharmacology, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, NJ, USA; Patient and Patient Advocate, Taiwan Hepatitis Information & Care Association, Taiwan)

Markus Cornberg Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology, Hannover Medical School, Germany.

Maura Dandri (I. Department of Medicine, University Medical center Hamburg- Eppendorf, Hamburg, and German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), Germany

Geoffrey Dusheiko (Kings College Hospital and University College London Medical School, London, UK)

Philippa Easterbrook (Global Hepatitis Programme, Department of Global HIV, Hepatitis and STI Programmes, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland)

Jordan J. Feld (Toronto Centre for Liver Disease, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Canada)

Marc Ghany (Liver Diseases Branch, National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Harry L.A. Janssen (Toronto General Hospital, University of Toronto, Canada)

Marko Korenjak President of the European Liver Patients' Association, Brussels, Belgium

Pietro Lampertico (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Milan, Italy; CRC “A. M. and A. Migliavacca” Center for Liver Disease, Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, Milan, Italy)

Hannah Lee (Stravitz- Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health; Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA)

Jake Liang (Liver Diseases Branch, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA)

Anna S. Lok (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI)

Francesco Negro Departments of Medicine and of Pathology and Immunology of the University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland.

Barbara Rehermann (Liver Diseases Branch, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA)

Virginia Sheikh** (Division of Antiviral Products, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, USA)

-

George Papatheodoridis (Department of Gastroenterology, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, General Hospital of Athens “Laiko”, Athens, Greece)

23. Jörg Petersen (IFI Institute at the Asklepios Klinik St Georg Hamburg, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany)

Norah Terrault (Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Southern California, USA)

Zobair M. Younossi, Department of Medicine, Inova Fairfax Medical Campus.

Man-Fung Yuen Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology in the University of Hong Kong

*This article represents the opinion of the authors and does not represent the official policy or views of the EMA/CHMP or the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM).

** This article represents the opinion of the authors and does not represent the official policy or views of the FDA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Marc G. Ghany: nothing to report.

Maria Buti: Advisory Board/Speaker Bureau for: Abbvie, Altimmune, Assembly, Antios, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Roche Mercke Sharp and Dohme and Springbank

Pietro Lampertico: Advisory Board/Speaker Bureau for: Bristol Meyers Squibb, Roche, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbvie, Mercke Sharp and Dohme, Arrowhead, Alnylam, Janssen, Springbank, MYR, Eiger, Antios, Aligos, VirBio.

Hannah Lee: nothing to report.

References:

- 1.Cornberg M, Lok AS, Terrault NA, Zoulim F, Faculty E-AHTEC. Guidance for design and endpoints of clinical trials in chronic hepatitis B - Report from the 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference(double dagger). J Hepatol 2020;72:539–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lok AS, Zoulim F, Dusheiko G, Ghany MG. Hepatitis B cure: From discovery to regulatory approval. Hepatology 2017;66:1296–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yip TC, Wong GL, Chan HL, Tse YK, Lam KL, Lui GC, Wong VW. HBsAg seroclearance further reduces hepatocellular carcinoma risk after complete viral suppression with nucleos(t)ide analogues. J Hepatol 2019;70:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yip TC, Wong VW, Lai MS, Lai JC, Hui VW, Liang LY, Tse YK, et al. Risk of hepatic decompensation but not hepatocellular carcinoma decreases over time in patients with hepatitis B surface antigen loss. J Hepatol 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.www.globalhep.org/sites/default/files/content/resource/files/2021-05/WHO%20Progress%20Report%202021.pdf. Last accessed January 16th, 2023.

- 6.Hsu YS, Chien RN, Yeh CT, Sheen IS, Chiou HY, Chu CM, Liaw YF. Long-term outcome after spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2002;35:1522–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lok AS, Lai CL, Wu PC, Leung EK, Lam TS. Spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion and reversion in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 1987;92:1839–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler EK, Gersch J, McNamara A, Luk KC, Holzmayer V, de Medina M, Schiff E, et al. Hepatitis B Virus Serum DNA andRNA Levels in Nucleos(t)ide Analog-Treated or Untreated Patients During Chronic and Acute Infection. Hepatology 2018;68:2106–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MH, Yang HI, Liu J, Batrla-Utermann R, Jen CL, Iloeje UH, Lu SN, et al. Prediction models of long-term cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in chronic hepatitis B patients: risk scores integrating host and virus profiles. Hepatology 2013;58:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Su TH, Wang CC, Chen CL, Kuo SF, et al. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low HBV load. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1140–1149 e1143; quiz e1113-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]