Abstract

Current research suggests that gentrification is an important determinant of health. Furthermore, this research concludes that the health impacts of gentrification are heterogeneous and may have adverse impacts on Black Americans. However, existing gentrification and health research has not fully engaged with the racialized processes that produce these uneven impacts. To address this gap, we develop a conceptual framework to describe how gentrification may create unique experiences and differentiated health impacts for Black Americans. Applying a lens of racial capitalism, we examine how an ongoing legacy of structurally racist urban and housing policy in the United States has disinvested from and devalued Black communities; thereby rendering them vulnerable to subsequent reinvestment through gentrification. Next, we consider how this history creates unique health vulnerabilities to gentrification for Black residents. Finally, we describe pathways of displacement—physical and symbolic—through which these unique health vulnerabilities are shaped to produce differences in health.

Keywords: gentrification, health disparities, race, neighborhoods

Introduction

An emerging body of literature examines the health impacts of gentrification (Schnake-Mahl et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Tulier et al., 2019). To date, however, research on gentrification and health has lacked consistency due to the complex and spatially uneven manifestations of gentrification (Tulier et al., 2019). These uneven manifestations suggest that gentrification’s effects are heterogeneous, differing across subpopulations (Bhavsar et al., 2020; Schnake-Mahl et al., 2020). Notably, some health research has found racial differences in health outcomes associated with gentrification, as Black, but not white, residents experience adverse health effects (Gibbons & Barton, 2016; Huynh & Maroko, 2014; Izenberg et al., 2018). While prior research on gentrification and health has considered race as a variable that may moderate gentrification’s impacts on health (Bhavsar et al., 2020; Gibbons & Barton, 2016; Izenberg et al., 2018), this research does not, for the most part, address how race intersects with gentrification processes. Given a history of structurally racist and discriminatory urban and housing policies and practices, a critical race lens is necessary to unpack how this history may shape the experiences and impacts of gentrification for Black Americans. In order to fully understand gentrification’s impact on health, future research must critically examine gentrification as a racialized process, meaning that it is driven by racist logics, and that the experiences and effects of this process differ for people in different racialized groups.

Indeed, existing scholarship on gentrification focuses primarily on class and often overlooks the role of race, and when race is included, scholars rarely offer a theoretically relevant analysis of its role (Fallon, 2020). For example, these studies may employ static individual race variables that fail to uncover how race and racism interact with urban processes, group race with class variables which obfuscates the true effects of racism on health, or remove race from the definition of gentrification altogether (Fallon, 2020). Yet urban processes are shaped and defined by racialized policies and practices, and the racial demographics of the people who live within urban spaces (Dantzler, 2021; Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021). To address this gap in the literature, we develop a conceptual framework that critically examines gentrification as a process that is both class-based and racialized. In doing so, we consider the uneven health impacts of gentrification through processes of physical and symbolic displacement for Black communities and their residents.

To advance our understanding of gentrification’s racialized impacts on health, scholars must engage with transdisciplinary theory and debates about the nature, causes, and consequences of gentrification. Current research on gentrification and health often frames gentrification as a solution for or “upgrading” from disinvestment and corresponding adverse health outcomes (Tulier et al., 2019) which may have undesired and unequal side effects for marginalized, in particular Black, residents. Through this lens, gentrification offers residents a “trade-off” between benefits, such as new parks, and costs, such as displacement (Ellen & Captanian, 2020) with positive and negative potential health effects. However, this lens fails to consider how and why such benefits and costs are distributed across different places and people. This lens also fails to question why gentrification is necessary to remediate health hazards in disinvested neighborhoods, and why different racialized groups experience gentrification’s effects in such uneven ways. In developing this conceptual model, we engage with transdisciplinary scholarship and theory to help answer these critical questions and clarify the uneven and complex effects of gentrification on health.

Thus, following calls to “re-politicize” how gentrification-related changes may affect health (Anguelovski, Connolly, & Brand, 2018), we offer a transdisciplinary framework that employs Marxist geography and critical race theory to frame gentrification as a process of racial capitalist uneven development, and parse out how it thereby exacerbates inequalities in health. First, our conceptual framework unpacks theories of rent gap and racial capitalism to explain why Black neighborhoods and residents are particularly vulnerable to gentrification processes and its adverse health impacts. Understanding gentrification through these critical theories reveals that gentrification is not contingent on class change alone but that neighborhood redevelopment is an inherently racialized process that relies on the dispossession of Black neighborhoods and Black people. Second, building from this theoretical analysis and through analyzing the existing gentrification and health literature, our conceptual framework aims to 1) describe the evidence, to date, on how gentrification may unevenly affect the health of Black residents by examining pathways of displacement (physical and symbolic) as well as 2) identify how the nature of gentrification as a racial capitalist process informs these differentiated effects.

Our focus on Black communities and residents is intentional. While we recognize that Indigenous, Latine, Asian, and even white communities can be devalued and appropriated for profit, the effects of gentrification on health may differ due to different histories of racialization. The United States’ legacy of anti-Black violence is foundational to the production and reproduction of urban space and continues to marginalize Black communities and residents, through gentrification and other means (Kent-Stoll, 2020; Lipsitz, 2007; Taylor, 2019). A history of racialized housing policy in the United States, through which racial capitalism has long operated, demonstrates that anti-Black racism facilitates profit accumulation for white communities and stakeholders by commodifying space in ways that simultaneously devalue and dispossess Black people. We acknowledge that some racial experiences of Blackness may be shared beyond the United States; however, other aspects (i.e., systems of power and political economies of race) are unique to the United States and applying this conceptual model elsewhere would be problematic (Lees, 2016; Lees & Hubbard, 2021).

Background

Prior research considering race in gentrification processes

While research assessing the role of race in the gentrification and health literature is limited, scholars in other disciplines have examined gentrification and its impacts through a critical race lens. This work suggests that while Black neighborhoods may not be initial targets for gentrification early on, these neighborhoods may later experience gentrification due to the racial valuations placed on them by specific “gentrification stakeholders.” For example, Black neighborhoods may become highly valued by individual white gentrifiers because of their “diversity” (Hyra, 2017; Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021; Summers, 2019). Indeed, Derek Hyra’s research in Washington, DC (2017) details how “black branding” and the consumption of Black culture are motivators that drive white in-movers to Black neighborhoods. Likewise, also examining DC, Brandi Thompson Summer’s research (2019) has explored how Black authenticity is strategically deployed to reorganize urban spaces via redevelopment and revitalization. In these cases, Blackness is aestheticized and subsequently commodified to propagate gentrification, led by white gentrifiers, while Black residents are displaced to remake neighborhoods (Boyd, 2008; Pattillo, 2010; Summers, 2019).

Additionally, other scholars have begun examining the intersectionality of multiple social categories—race, gender, class, sexual orientation, to name a few—in gentrification research. At the intersection of race and class, work by Michelle Boyd (2008) and Mary Pattillo (2010) showcases that other “gentrification stakeholders” include non-white actors such as Black middle-class in-movers and Black developers who may gentrify Black neighborhoods because they place higher value on culture and have shared histories of oppression with long-term residents. This work unpacks how race is leveraged as a tool to promote the class interests of Black middle-class residents in changing urban landscapes. Here, race and class operate as mutually complicit forces to exploit and exclude Black lower-class residents, while simultaneously privileging the interests of the Black upper class but also those of white residents, politicians, and developers.

Continuously, in her work advancing Black feminist intersectional analysis, Rosemary Ndubuizu (2023) explores how gender is leveraged in United States racial politics to spur displacement and exacerbate inequities in access to affordable housing in gentrifying areas. This research examines how the state perpetuates stereotypes of low-income Black families, especially those led by single Black mothers in public housing, to justify and validate contemporary gentrification via government-funded programs like HOPE VI. As mentioned above, Black neighborhoods are initially avoided by white homebuyers and renters and thus not the first neighborhoods to gentrify (Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021), however, city government officials, developers, and private investors may expand revalorization to these neighborhoods due to the potential for profit (Hackworth, 2007; Hackworth & Smith, 2001; Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021). Intervention by these gentrification stakeholders, through programs like HOPE VI, can trigger larger-scale and faster gentrification that may be unique to Black neighborhoods because of the potential return of investment caused by legacies of disinvestment (Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021). While HOPE VI was a program designed to revitalize distressed public housing, demolition often occurred in areas that were already on a path to gentrification, accelerating this process and facilitating the displacement of Black communities to neighborhoods with less opportunity (Bennett & Reed, 1999; Goetz, 2011; Hyra, 2012; Keene, 2016; Keene & Geronimus, 2011). Of the residents that were displaced from these public housing sites, research shows that low-income single mothers and their households experienced displacement and housing insecurity at disproportionate rates (Duryea, 2006; Ndubuizu, 2023).

Collectively, this research, analyzing gentrification through critical race and intersectional lenses, showcases that while racial change may not always be an outcome of gentrification, racialization and racism are intrinsically linked to the process of gentrification and can explain who and where is most vulnerable to gentrification and its impacts (Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021). This scholarship also highlights that race can and does intersect with multiple social categories in complex and dynamic ways that exacerbate harm under gentrification processes. To further understand the impacts of gentrification, however, scholarship must aim to uncover why gentrification is experienced differently by different racialized groups. This research should explore the root causes of disinvestment to help explain why differentiated experiences of gentrification across racialized groups and neighborhoods exist. Continuously, scholarship must also assess how, or through what processes, these differentiated experiences shape adverse impacts, especially in the context of health. Transdisciplinary theory and debates can help us develop a framework that elucidates why and how race shapes the causes, impacts, and experiences of gentrification. Developing such a model will have significant implications for how gentrification is defined, operationalized, and measured (Fallon, 2020; Lees, 2016) as well as how impacts are analyzed in research and policy.

Rent gap theory

Understanding gentrification as a racialized process requires moving beyond Marxist frameworks that centralize the role of class. For many scholars—notably those using a critical urban theory lens and Marxist political economic frameworks to understand gentrification—the flows of capital in accordance with profit-making potential, via class transformation, is one of the most significant drivers of gentrification (Kent-Stoll, 2020). Marxist geographer Neil Smith, for instance, foregrounded his conceptualization of gentrification in class struggle and capital accumulation –highlighting that gentrification processes are not driven by consumption or the changing tastes of people, but by capital (Smith, 1979). In his influential theory of rent gap (1979), Smith illustrates how the disparity between the current value of property and its potential value is a key feature that paves the way for gentrification to take place. If there is no disparity or “rent gap,” there would be no return on investment or no economic benefit from redevelopment. Therefore, for the rent gap to exist, capital depreciation and devaluation in neighborhoods must also exist as private developers and state actors are able to buy disinvested land cheaply and sell at a profit.

Contemporary conceptualizations of gentrification theory, in accordance with Marxism’s prominent focus on class as the central tenet of exploitation, often expand Smith’s work by clarifying critiques of rent gap theory (Slater, 2017a), assessing its applicability across different geographic settings including cities outside of the Global North (Darling, 2005; O’Sullivan, 2002; Slater, 2017b), as well as exploring how the rent gap develops across different stages of gentrification (Wachsmuth & Weisler, 2018) and different geographies of development (Hammel, 1999). Though there are exceptions (Kent-Stoll, 2020; Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021), what is largely missing in this contemporary literature is how race operates in the context of gentrification processes. The rent gap theory, for example, does not emphasize the role of racist housing policy or centralize race. Smith and many others who expand on his work do not emphasize how racist policies and practices, promulgating segregation and racialized spatial stigma, have shaped which neighborhoods experienced disinvestment. As such, scholarship drawing on the rent gap theory often ignores the racial and colonial dimensions that shape space and exploit/dispossess specific communities and neighborhoods over others (Kent-Stoll, 2020).

Racial capitalism and place

Indeed, many scholars have identified limitations in the race-neutral interpretation of capital accumulation in Marxist theory, and increasingly in Marxist geography specifically. Marxist analysis, preoccupied with European industrialization and the exploitation of labor, neglects the experiences of Black people and Black resistance (Melamed, 2015). Cedric Robinson’s seminal work on racial capitalism (2000), which was developed to critique Marxism’s overt removal of race and racism in contextualizing the emergence and growth of capitalism, posits that our current world economy under capitalism was established through slavery, colonialism, and genocide, all of which continue to devalue and harm racially minoritized groups, especially Black communities, via capitalistic gain. Racial capitalism is the process of “deriving social and economic value” from racial identity (Leong, 2012, p. 2190); it establishes that the commodification of race and the accrual of capital are two sides of the same coin. A nascent body of theoretical work has begun to connect racial capitalism to urban development and more specifically gentrification (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019; Dantzler, 2021; Rucks-Ahidiana, 2021), which offers a foundation for exploring how the logics of cyclical devalorization and revalorization Smith describes must be understood specifically as built on the production and exploitation of racial difference. A lens of racial capitalism is critical to understanding the uneven geographic development of gentrification—specifically how the prior disinvestment of Black communities renders them vulnerable to subsequent revalorization.

In the context of place, there are distinct connections between capital accumulation and anti-Blackness, demonstrating how the construction of racialized space has facilitated profit accumulation in white communities, built upon disinvestment in, extraction from, and the destruction of Black communities (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019). This work points to the mutually constitutive nature of “race” and space. It demonstrates that urban space is not only a container for and reflection of processes with racialized impacts, but also that racialized processes are enacted and the construction of race is actualized through space, in ways which are linked to the valuation of those spaces and people (Brand & Miller, 2020). Thus, Black communities are constructed as deviant, dying, and destructible, and, simultaneously, Black people as pathological and devaluing. The perceived “aspatiality” of Black people further renders Black spaces available for capital accumulation, legitimizing displacement (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019; Dantzler, 2021; McKittrick, 2011). Thus, anti-Black racism can operate as a “precondition for the perpetuation of capitalism” (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019, p. 8). by devaluing Black spaces as a means to profit from appropriation through processes like gentrification. This lens illustrates that places are inherently racialized through valuation where resources and capital are concentrated in white communities, premised upon extraction from and disinvestment in Black communities and that Black people may still be devalued and indeed seen as illegitimate occupants in now-revalorized places (Dantzler, 2021).

Disinvestment in Black communities can be linked to a history of racial capitalist housing policies in the United States that have facilitated the co-production of race and property value through the segregation, exclusion, exploitation, and displacement of Black communities. Separation enables value differentiation and thus creates the possibility for profit accumulation (Dantzler, 2021). The devaluation and exclusion of Blackness generates value for white communities, while simultaneously systematically preventing Black people from building wealth, and facilitates the uneven distribution of resources and hazards (e.g., Freund, 2007; Imbroscio, 2020; Lipsitz, 2011; Pulido, 2017; Taylor, 2019). This history of racialized value is based in anti-Black racism and uplifts the white spatial imaginary which Lipsitz (2007) explains is based on “exclusivity and augmented exchange value” (p. 13). Here, white communities own appreciable property and accumulate wealth that can be passed down through generations while Black communities are relegated to structurally disinvested communities seen to be legitimate targets for appropriation and revalorization (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019; Lipsitz, 2011). Historically and at present, these racial capitalist policies and practices such as slavery, racialized zoning, redlining, segregation, white flight, urban renewal, and subprime lending, have led to the erosion of resources and the systematic disinvestment of Black communities and have reduced power for and disenfranchised Black residents—while establishing conditions that enable future profitable revalorization (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019). This racialized history highlights that race, and not class alone, dictates the devalorization and subsequent revalorization of Black neighborhoods, via processes like gentrification.

Thus, the disinvestment required for gentrification to occur is built on a foundation of racializing value to enable profit accumulation. This emphasizes that disinvestment and gentrification are not opposites but two sides of the same coin under racial-capitalist uneven development (Marcuse, 1985; Slater, 2021, pp. 54–55). As such, gentrification should be understood not as an independent one-time phenomenon, but rather as adding to a cumulative total, the latest instance in a series of processes of devaluation and dispossession that has and continues to adversely affect Black residents and communities. As discussed by Fullilove and Wallace (2011), gentrification is part of an ongoing legacy of serial forced displacement where racialized policies and practices transfer and amplify disadvantage onto Black people across generations. Thus, in understanding the health impacts of gentrification it is important to place gentrification in context with other dispossessive processes. In our conceptual model, we advance this research on racialized serial forced displacement (Fullilove & Wallace, 2011) by going beyond assessing the health impacts of physical displacement, to also consider symbolic displacement or experiences of displacement for residents who are able to stay in place. We also advance this work by placing it in the context of racial capitalism, therefore analyzing displacement as a process needed to accumulate profit for specific actors.

Altogether, this cumulative legacy of forced upheavals or displacements (Fullilove & Wallace, 2011), both physical and symbolic, suggests that Black people may be affected by and experience gentrification in a differentiated way, especially in the context of health, due to their repeated exposure to dispossession and discrimination, which we now explore in our conceptual model below.

Towards a racialized health framework

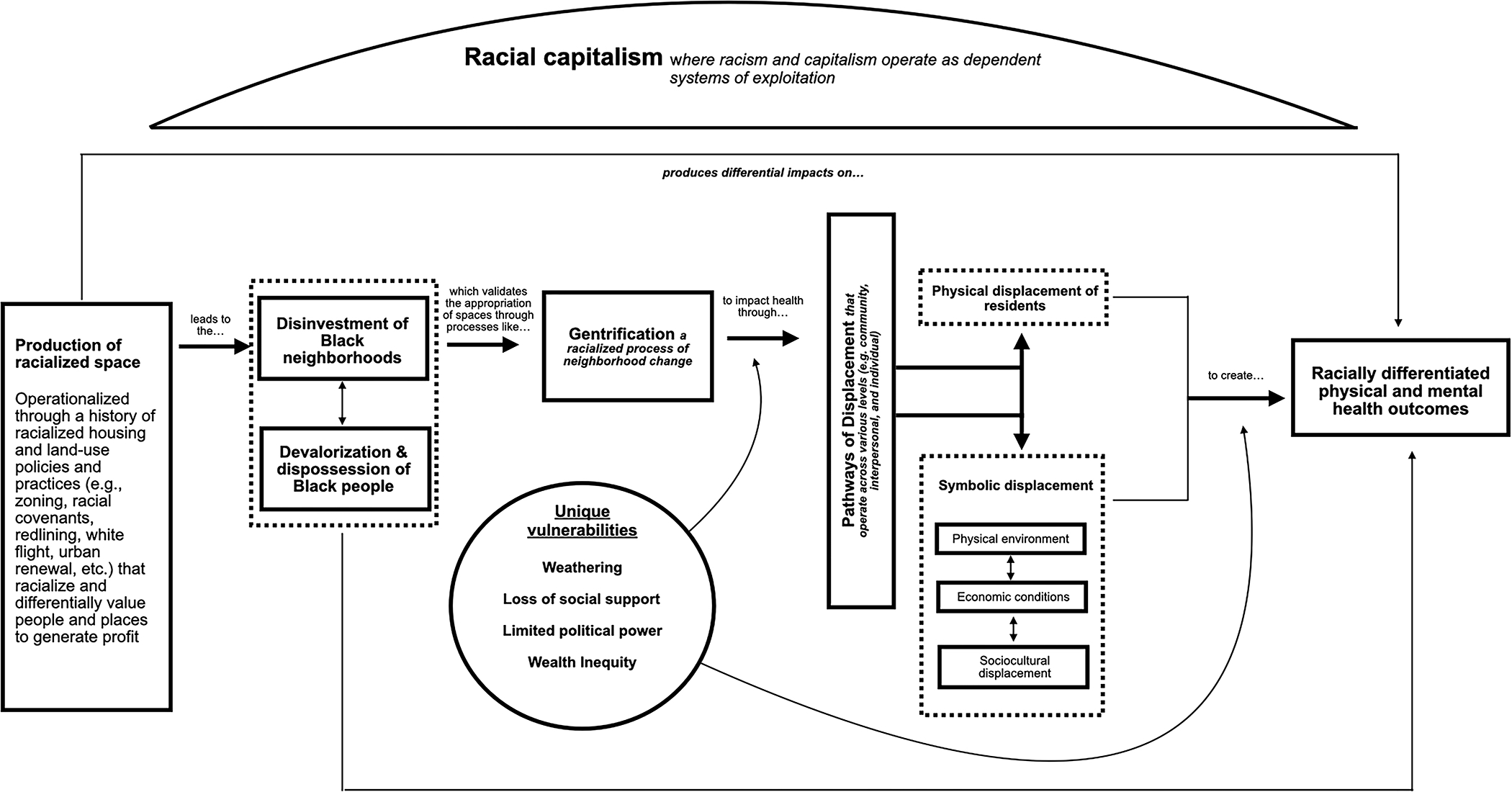

Considering the aforementioned analysis of racial capitalism, gentrification, and disinvestment, we offer a conceptual model (Figure 1) to unpack the impact of gentrification on health for Black residents. As noted above, research on gentrification and health rarely engages with transdisciplinary scholarship. Because of this lack of engagement, this research may consider race as a moderator between gentrification and health (Bhavsar et al., 2020; Gibbons & Barton, 2016; Izenberg et al., 2018), a variable disconnected from gentrification processes altogether. However, these methods, for the most part, do not address how racist and structural factors intersect with gentrification processes nor do they uncover what about race is at play to moderate effects. Rather than assuming a universal impact on health from gentrification-related changes, or assessing race as a static moderator of these effects, our framework identifies mechanisms through which racialization and racial capitalism may create unique vulnerabilities to gentrification’s health impacts. Furthermore, rather than framing these vulnerabilities as incidental, we contextualize them in the workings of racial capitalism and other structural forms of racism. That is, we do not argue that Black communities simply happen to bear the burden of a set of disproportionate vulnerabilities to gentrification, nor that uneven adverse effects from gentrification are merely undesirable side effects of the process to be mitigated. Rather, racial capitalism shapes gentrification as a process and places racialized bodies at different vulnerabilities for harmful effects. Therefore, tying healthy environments and positive health outcomes to gentrification is a “false choice” between continued disinvestment and gentrification (DeFilippis, 2004), as gentrification does not address the root cause of disinvestment but is a new manifestation of it. Rather than offering a solution to disinvestment’s negative health ramifications, gentrification may perpetuate the linkage between the devalorization of Blackness and health riskscapes, albeit in new forms.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the racialized health effects for Black communities and residents under gentrification

Next, our conceptual model aims to examine how gentrification affects the health of Black residents via pathways of displacement. While disinvestment is antecedent to capital accumulation via gentrification, displacement is a necessary step that detaches people from places and resources to remake neighborhoods (Dantzler, 2021) and as a process, has significant implications for population health. Physical or residential displacement describes the involuntary dislocation of a household caused by either physical (i.e., the deterioration of a building or of neighborhood services) and/or economic forces (i.e., rent increase) outside of that households’ control (Marcuse, 1985). Symbolic displacement, on the other hand, refers to the loss of place felt by residents trying to stay put as their neighborhoods change physically, economically, socially, and culturally (Elliott-Cooper et al., 2020; Marcuse, 2013). By understanding gentrification as a racial capitalist process, we aim to connect how these two pathways produce differentiated health effects at the individual level, as well as reshape neighborhood riskscapes for gentrifying neighborhoods. In delineating these pathways of displacement, we primarily draw on literature centering the Black experience in the United States. Though in a few cases, we draw on relevant evidence about the effects of gentrification on health in other contexts.

Racial capitalism and unique vulnerabilities for Black communities and residents

Black communities and residents are uniquely vulnerable to adverse health impacts related to gentrification for a multitude of reasons. Owing to a legacy of serial forced displacement, noted above, gentrification may have adverse health consequences for Black communities and residents as it amplifies and compounds, rather than merely adds to, the impacts of prior displacements (Fullilove & Wallace, 2011).

First, racial capitalism and other structural forms of racism may create unique biosocial vulnerabilities to gentrification for Black residents whose bodies may bear the cumulative toll of chronic stress associated with racism (Geronimus et al., 2006; Krieger, 2001). Research illustrates how cumulative exposure to racialized stressors contributes to premature cellular aging (Geronimus et al., 2015), and the earlier onset of age-related chronic health conditions (Geronimus et al., 2006), through a process of weathering. For Black Americans, in particular, living in a racialized society that accumulates disadvantage for Black individuals and stigmatizes Black communities contributes to a disproportionate burden of stress related chronic health conditions (Geronimus et al., 2004) and thus potential vulnerability to the stressors of gentrification. For example, chronic health conditions caused by weathering may become exacerbated by disruptions in health care access caused by gentrification-induced displacement.

Additionally, gentrification may disrupt social support and community resources that can mitigate weathering. Indeed, extant research indicates that social support is critical to health and well-being (Berkman & Glass, 2000; Thoits, 2011; Uchino, 2006). Subsequently, a large body of literature highlights the adverse effects of lost social support (Wang et al., 2018; Wärnberg et al., 2021). Social support is particularly important for low-income communities who may rely on their social networks for informal caretaking and other forms of informal support to avoid material hardship and make ends meet (Keating-Lefler et al., 2004; Mills & Zhang, 2013; Stack, 1997). Continuously, a loss of social support may have unique consequences for Black residents of gentrifying neighborhoods. For instance, George Lipsitz, in his theorization of the Black spatial imaginary, showcases that Black communities employ creative forms of mutual support, from pooling resources to organizing in public spaces in order to mitigate adverse economic and social impacts of racist policies and practices (Lipsitz, 2007, 2011). These dynamic networks not only provide social support but also uplift identity-affirming frameworks that have been shown to mitigate the harmful health impacts of racism (Geronimus, 2000). This loss of social support and the racially-specific meanings and consequences of this loss may shape particular health consequences of gentrification for Black residents in the United States and remains a concern for Black residents living in gentrifying neighborhoods elsewhere (Lees & Hubbard, 2021).

Furthermore, racial capitalist practices and policies and the history of anti-Black violence in the United States have limited political power for Black people by hoarding profit-making opportunities for white actors (Gonzalez & Mutua, 2022); thereby systematically dispossessing and disenfranchising Black communities. A lack of political power reduces Black communities’ ability to develop and implement policies that are critical for reaching optimal health (Dawes, 2020; Dawes et al., 2022). As neighborhoods change via processes like gentrification, Black political power becomes further dispersed as Black residents are either forced to leave their neighborhoods or excluded socially and culturally if they are able to stay (Hyra, 2015). At the neighborhood level, a loss of concentrated political power limits the ability of community members to support and enact changes that are beneficial to their collective well-being (Betancur, 2002; Hyra, 2015). At the individual level, this dispersal of Black political power makes Black residents feel powerless to the changes occurring in their neighborhoods which can decrease self-efficacy and increase physical and mental distress (Holt et al., 2021). It may also increase tension with and resentment towards new residents (Hyra, 2015) which may further segregate and exclude Black residents and thus impact mental health as neighborhoods change.

In addition to limited political power, another reason why Black communities and residents may be increasingly vulnerable to adverse health impacts related to gentrification is due to wealth inequity. The history of racial capitalist housing policies and practices intentionally removed Black people from systems of investment and wealth building (i.e., owning property and equal labor) (Markley et al., 2020). A substantial body of literature links greater wealth to better health (Pollack et al., 2007), which may mean that Black residents experience more adverse health outcomes given limited opportunities to accumulate wealth. Wealth inequalities may further create differential vulnerability to adverse health outcomes by increasing financial precarity under gentrification as the cost of goods and housing rise; further exposing Black residents to well-documented physical and mental health impacts of financial stress (Sturgeon et al., 2016; Whitehead & Bergeman, 2017).

While the above mechanisms describe general ways that racial capitalism and structural forms of racism shapes uneven impacts of gentrification for Black residents, we now turn to their manifestation across specific pathways related to gentrification-induced changes.

Pathways from gentrification to health: Physical displacement of residents

One way that gentrification influences health is through the physical or residential displacement of residents who are no longer able to stay in their neighborhoods. A large body of literature, not specific to gentrification, documents that displacement or involuntary moves serves as a significant disruption to daily life in ways that may influence health and well-being (Desmond & Kimbro, 2015; Hori & Schafer, 2010; Schwartz et al., 2022).

Black households may be disproportionately vulnerable to gentrification-induced physical displacement for multiple reasons. As mentioned above, Black residents may be particularly vulnerable to displacement due to financial insecurity. Black neighborhoods may also be vulnerable to large scale gentrification such as HOPE VI which may lead to the displacement of residents. Furthermore, previous legacies of serial forced displacement have shaped how Black residents understand their vulnerability to present-day displacement caused by gentrification. For example, a study conducted in Portland, Oregon among older Black adults observed that residents perceived their vulnerability to contemporary physical displacement to be related to prior waves of displacement in the 1960s to 1990s (Croff et al., 2021). Participants believed that past and present-day displacement of primarily Black residents was a city-led initiative to disinherit Portland’s Black community. In expressing this view, residents referred to overt racism in the housing market that created wealth inequalities.

Additionally, it is important to note that housing tenure may also shape vulnerability to gentrification-induced physical displacement among Black residents. Renters are likely at the highest risk for displacement due to increased rent and higher living costs, compared to homeowners and residents who live in subsidized housing (where housing costs are adjusted to fit the tenant’s income) (Dragan et al., 2020; Freemark et al., 2021).

This disproportionate vulnerability to gentrification-induced physical displacement can contribute to negative health impacts for Black communities. Fullilove (2001) examined how community displacement during midcentury urban renewal adversely affected health for Black communities through “root shock,” or the emotional trauma one may experience due to the loss of their emotional ecosystem. Ultimately, this loss impacts health in three key ways: directly causing stress, exposing residents to substandard housing and adverse environments in their destination neighborhoods, and draining resources for resettlement which could otherwise be used to meet important needs. Indeed, what scholars such as bell hooks (1990) have termed the “homeplace” is critical for Black communities as it provides a physical space for Black people to be restored, feel rooted in community, resist oppression, and also develop a political consciousness. When homeplaces or these physical “sites of resistance” and restoration are lost, Black communities may have difficulty constructing socio-cultural identities, embodying power in and control of their own lives, and developing and maintaining familial structure and routine (Burton & Clark, 2005; Williams, 2018)—all of which may adversely impact psychological well-being. Considering gentrification as the most contemporary process in a chain of serial forced displacement and dispossession, Black residents must contend with the compounded health consequences of multiple episodes of emotional trauma due to lost homeplaces (Fullilove & Wallace, 2011; Hyra, 2012).

Yet, research directly assessing physical displacement, gentrification, and health is limited due to the methodological challenges inherent in defining and measuring displacement. These challenges include difficulties in identifying gentrifying neighborhoods, as well as tracking displacees, either locally or through available datasets (Easton et al., 2019), which are equally important for both qualitative and quantitative research. Nevertheless, an emerging body of research does suggest harmful impacts of gentrification-induced displacement on health. In a quantitative study examining health impacts from gentrification-related physical displacement, Lim et al. (2017) find that residents displaced from gentrifying/gentrified tracts are more likely to utilize emergency department services and experience hospitalizations due to drug and alcohol intake and mental health, compared to residents who remain, suggesting that displacement may trigger abrupt disruptions in access to primary care. Furthermore, the authors suggest that loss of interpersonal ties associated with displacement may result in psychological distress that increases mental health related hospitalizations. Likewise, research assessing the effects of HOPE VI, a program that has been considered a form of state-led gentrification, illustrates that displaced residents experienced increased stress due to economic hardships and difficulty in finding replacement homes after being displaced (Keene & Geronimus, 2011). Residents displaced by HOPE VI in this study also experienced social isolation and reduced access to supportive relationships after relocation.

Research on gentrification-induced physical displacement also suggests that the characteristics of destination neighborhoods may also shape displaced residents’ health. For example, Anguelovski et al. (2021) finds that residents who become displaced to locations far from the center of the city often face poor or poorer housing quality and experience longer and more expensive commute times; both of which negatively impact physical and mental health. For Black residents, experiences in destination neighborhoods may specifically be shaped by racism. Residents displaced from gentrifying Portland neighborhoods, for example, reported racially-charged, stressful interactions in new neighborhoods, often citing confrontational events with white residents (Croff et al., 2021). Feeling unwelcomed in relocation areas and/or experiencing racial tension can undermine health in multiple ways: Displaced residents may face constrained opportunities such as barriers to employment and housing, as well as increased psychosocial stress as they confront racial discrimination and exclusion (Keene & Padilla, 2010).

Thus, claims that long-term residents of gentrifying neighborhoods may experience health benefits from much-needed reinvestment and remediation must be tempered by the possibility that residents could be physically displaced. Not only could physical displacement mean that the supposed health-relevant benefits in residents’ gentrifying neighborhoods fail to reach them—it could also potentially contribute to direct health effects related to disruption and distress, and lead to additional health-harming exposures in new neighborhoods.

Pathways from gentrification to health: Symbolic displacement

Gentrification may also affect the health of those able to stay in gentrifying neighborhoods through symbolic displacement. Symbolic displacement (Atkinson, 2015) refers to a sense of alienation and loss of place and is related to similar concepts of displacement pressure (Marcuse, 1985), phenomenological displacement (Davidson & Lees, 2010) or everyday displacement (Stabrowski, 2014). Understanding displacement solely as a single moment of physical migration excludes other dimensions such as the experiences of dislocation, disruption of networks and resources, and loss of feelings of security and spatial agency that residents, able to stay in gentrifying neighborhoods, may feel as neighborhoods dramatically change (Davidson, 2008; Easton et al., 2019; Shaw & Hagemans, 2015).

We hypothesize three domains—physical environment, economic conditions, and sociocultural displacement—in which gentrification may symbolically displace residents in ways that influence health. As with physical displacement, symbolic displacement may disproportionately and adversely influence long-term, Black residents. These domains may interact and reinforce one another; for example, changes to the physical environment in the form of new institutions may alter economic conditions by driving up costs for goods and services, while also altering social interactions and culture by changing the spaces available for residents to gather.

Physical environment

One way that gentrification may symbolically displace residents is by transforming the physical characteristics of neighborhoods. Histories of disinvestment denied built environment resources to Black neighborhoods which could support health, while simultaneously inflating the value of white neighborhoods which offered more salubrious conditions. While gentrification is often associated with the provision of these health-supporting built environment resources, the resulting physical changes have significant racialized implications for health—as new healthful resources may not be similarly available to and accessible for Black residents, and may be accompanied by the loss of long-term health-supportive resources, or may trigger rising unaffordability.

The existing literature on gentrification has described how gentrification is related to neighborhood conditions—for example, the rehabilitation of abandoned and vacant buildings (Lee & Newman, 2021; Marcuse, 1985), inclusion of new public infrastructure (e.g., transit systems) (Padeiro et al., 2019), increased presence of supermarkets and other food stores (Cohen, 2018; Zukin et al., 2009), and remediation of environmental hazards (Anguelovski, 2016; Banzhaf & McCormick, 2007). However, these changes, while seemingly healthful for neighborhoods, may not offer universal benefits for all residents under gentrification processes.

Isabelle Anguelovski and colleagues’ (2018) work on “green gentrification” offers an illuminating example of how, in practice, supposedly health-promoting neighborhood changes—such as new park space or grocery stores selling healthier food options—may fail to benefit, or may even harm, marginalized residents. This work shows how green amenities can raise rents, leading to financial stress or physical displacement. It also illustrates how new residents may also impose different norms and practices, making it uncomfortable for long-term residents to use green spaces. Furthermore, “green gentrification” may lead to the loss of valued amenities and resources, and their replacement with higher-cost, inaccessible, or otherwise exclusionary options. Importantly, the researchers also emphasize that green interventions are nevertheless framed as offering public benefits to all residents, despite the capture of new value by advantaged actors.

Other work on green spaces, focused more specifically on Black residents, further demonstrates how neighborhood changes may not have the same health impacts across groups. For instance, a study conducted in West Philadelphia, a historically Black neighborhood, observed that white residents and university students perceived their gentrifying neighborhood as favorable to physical activity due to newly created resources such as a local bike share program, running trail and walking path, and a newly developed University Park (Schroeder et al., 2019). On the other hand, Black residents reported that poorly maintained, unsafe parks, and scarce or unaffordable recreation facilities created barriers to physical activity. The authors hypothesize that these racial differences can be attributed to new, and often more privileged, residents having better access to improved resources, and long-term residents experiencing increased stress and reduced social capital which may decrease the likelihood of long-term residents engaging in physical activity. Other research by Cole (2019) hypothesizes that racist histories may shape the use of places like parks. Black residents, for example, may avoid parks and other outdoor spaces due to previous exclusion through policies such as Jim Crow, and associate these open spaces with different types of violence such as lynching and experiences of racism and discrimination (Finney, 2014).

Similarly, the building of new supermarkets and grocery stores in gentrifying neighborhoods may lead to differential access for Black residents who are able to stay put. For example, Sullivan (2014) found that a newly-constructed supermarket in a previous food desert went largely unused by Black residents. Sullivan hypothesizes that the new supermarket did not appeal—or was not accessible—to Black residents for economic and/or cultural reasons, as will be discussed below. Thus, this new resource may not have yielded health benefits for all residents.

While gentrification may lead to the construction of new amenities like parks and supermarkets, it may also physically displace or remove neighborhood establishments such as social services from gentrifying neighborhoods with implications for health and well-being. In Los Angeles, for example, a day center for street children was evicted from a central space in Hollywood due to gentrification and subsequent rising rents (De Verteuil, 2011). This center later bought a smaller building in a more marginal location on the fringes of Hollywood making it less accessible to those who may have relied on this resource for social services such as housing, medical care, and other basic needs. The displacement of services may also affect racial groups differently and gentrification may specifically displace resources that serve Black residents. In the same study, De Verteuil (2011) explains how a children’s charity in London, which served primarily homeless Afro-Caribbean teenagers, was displaced as a result of funding loss and reduced community support.

Additionally, Black-owned businesses may be particularly vulnerable to physical displacement due to policies and practices that have made it difficult for Black business owners to receive prime business loans. Residents in Harlem highlighted that racially discriminatory practices used by corporations and banks made it nearly impossible for Black business owners to receive loans and credit (Versey et al., 2019) which may make it difficult to remain in their gentrifying neighborhoods, especially as property taxes and the cost of housing and other goods increase. The loss of these long-time retail spaces may fragment neighborhood networks for remaining Black residents in ways that adversely impact mental and physical health. Indeed, a study of gentrification in Washington, DC, found that the removal of essential neighborhood businesses such as the local laundromat left Black residents feeling powerless as the resources they relied and depended on were removed (Holt et al., 2021). This sense of powerlessness may impact psychological health and well-being for these residents by increasing physical and mental distress (Thomas & Gonzalez-Prendes, 2009).

Economic conditions

Another domain in which gentrification symbolically displaces residents is by changing the economic landscape (i.e., the cost of housing and other goods) of neighborhoods. Economic shifts brought forth by gentrification occur due to a significant influx of capital in neighborhoods which had previously faced disinvestment (Richardson et al., 2019). Black residents’ financial position and experiences with these economic shifts may be shaped by a larger history of racial capitalism which has stripped them of opportunities to accrue wealth and gain economic stability. As noted above, this legacy of racial capitalism may create unique vulnerabilities to adverse health outcomes.

Gentrification is sometimes argued to positively influence the financial well-being of long-term residents as it may increase access to financial services and resources and increase home values for residents who securely own their homes (Ding & Hwang, 2016). However, the inflow of capital may lead to job losses for current residents (Meltzer & Ghorbani, 2017), and increase the costs of housing, goods and other services, making gentrifying neighborhoods less affordable (Richardson et al., 2019); thus, increasing financial strain for residents able to stay. Ultimately, these economic changes may increase stress and stress-related health consequences.

Some research on gentrification and health found significant psychosocial stress related to financial insecurity (Binet et al., 2021; Gibbons, 2019). For example, Binet et al. (2021) found that increased financial strain, caused by rising rents and costs of living, created stress for residents that undermined their health. Participants also noted that financial insecurity increased their stress by limiting social support networks as the costs of socializing increased, and time for socializing was consumed by the need to work longer hours.

Moreover, threats of displacement or the anticipation of fear of losing one’s home may feel imminent for residents living in gentrifying neighborhoods in ways that adversely impact health through stress pathways. Versey (2022b) describes how new real estate development heightened fears of displacement for Black residents. One participant from Cleveland, Ohio described how developers were buying homes at cheap prices and renting them out to residents at higher prices. In some cases, participants felt that they could not leave their current neighborhoods, despite the increasing costs, because surrounding neighborhoods were already more expensive and had fewer resources. As noted by Versey (2022b), displacement threat may be linked to feelings of insecurity, distrust, or harm; all of which can lead to stress and other negative coping behaviors (Versey, 2022a; Versey & Russell, 2022). More than that, displacement threat may heighten anticipatory stress (Gibbons, 2019), which research shows adversely impacts health (Hicken et al., 2013, 2014).

Additionally, financial strain caused by rising housing costs can affect residents’ ability to afford resources necessary for health. A large literature documents how high housing costs compete with resources needed to prevent and manage illness; often forcing residents to make trade-offs that are harmful for health (Fletcher et al., 2009; Keene et al., 2018; Meltzer & Schwartz, 2016; Pollack et al., 2010; Swope & Hernández, 2019). For example, one study examining the association between gentrification, food insecurity, and chronic illness found that rising rents were associated with food insecurity among a sample of low-income people living with HIV/AIDS in the San Francisco Bay area (Whittle et al., 2015). Participants in this study described how rents displaced food budgets and sometimes led them to use risky strategies such as sexual activity and selling drugs to procure food for survival.

Gentrification may also directly increase the price of goods in ways that influence health. As mentioned above, “green gentrification” may replace long-term amenities with exclusionary options. In the Boston area, Anguelovski (2015) observes how the arrival of a Whole Foods store economically, culturally, and politically transformed a Latino community. Economically, food gentrification—the increase in price of food staples and/or the removal of foods usually bought by long-term residents—excluded long-term residents from purchasing traditional foods, often doubling the price of food options compared to the former supermarket that the Whole Foods replaced. This increase in cost meant that residents spent more of their paychecks on food, or resorted to traveling to neighboring towns to shop for cheaper options. Similarly, for Black residents in the study detailed in the previous section, the arrival of a new supermarket left Black residents feeling excluded due to the expensive price of food - thus creating a food “mirage” (Sullivan, 2014). Price inflation for food and other goods limits how much food residents are able to buy and how often residents choose healthier food options necessary for good health (Binet et al., 2021).

Owing to a history of structured constraints and opportunities based in racial capitalism, Black residents may not be able to build wealth and attain financial security under gentrification, nor enjoy the ostensible health benefits which hypothetically accompany new types of goods and services. Instead, gentrification may worsen health for Black communities by increasing the cost of housing and goods and concomitant experiences of stress, reducing resource availability, and limiting coping mechanisms, like social support, which are integral for health.

Sociocultural displacement

A third way in which residents in gentrifying neighborhoods may experience symbolic displacement is through changes to the social and cultural fabric of their neighborhoods which may affect their sense of community and feelings of belongingness. Anguelovski et al. (2021) suggest that sociocultural displacement is produced by exclusion and social segregation; both of which may lead to ruptured social networks and diminished neighborhood social cohesion. These social factors are necessary to health as they positively impact physical and mental functioning and well-being, especially for vulnerable populations such as the elderly and home-insecure individuals (Anguelovski et al., 2021). Further, social networks are particularly important for Black residents, as previously discussed (Lipsitz, 2011). However, such practices become threatened under gentrification as Black residents have less political power to control the direction of the neighborhood’s physical, social and cultural development.

One way that long-term residents may experience social segregation and exclusion is through the removal of cultural traditions. For example, in the Tremé neighborhood in New Orleans, research illustrates how new white residents resisted and jeopardized longstanding traditions of music and second line parades that were an important part of cultural life for Black residents and had been in place for generations (Parekh, 2015). Similarly, in New York, Black residents in historically Black neighborhoods described how a long-standing cultural tradition of weekend outdoor R&B and Afrobeat performances was threatened and ultimately discontinued as a result of noise complaints from new residents (Versey, 2022b). This suppression of culture made residents in the study feel upset and distrustful of, not only newer residents, but also structural actors such as city officials, politicians, developers, and businesses who did not consult incumbent residents about new development plans and thus inflamed neighborhood divisions from the start. Mistrust and skepticism of new residents may create disparate value systems in neighborhoods as long-term residents question who and what cultures are being prioritized and valued, and feel like their cultural traditions are dismissed and not accepted by newcomers.

Long-term residents may also feel excluded from new businesses in gentrifying neighborhoods as they cater to the wants and needs of gentrifiers. For Black residents, in particular, these experiences of exclusion may be race-based. In Portland, Oregon, for example, Sullivan and Shaw (2011) document how Black residents perceive new businesses as “uppity” and “a little exclusive.” Often referring to white business owners as “them”, white businesses as “white shops,” and white residents as not belonging to “this community,” Black residents felt discomfort with white culture and expressed that new coffee shops, art galleries, and clothing stores did not cater to the Black community. One resident even noted that there were no places for Black people to hang out other than a bar that went out of business after the study was concluded. Feelings of resentment towards new residents may make Black residents feel excluded and pushed out of their own community; thereby increasing feelings of alienation from place, defined by Tuttle (2022) as the experience of one’s place as alien due to crime or gentrification. Decreased feelings of belongingness and community as well as a threatened sense of ownership of neighborhood amenities and space produce an increasing sense of their neighborhood feeling unfamiliar. Research also suggests that the “whitening” of neighborhoods may cause significant distress among non-white long-term residents (Freeman, 2006; Gibbons & Barton, 2016). More than that, the removal of social spaces for Black residents reduces opportunities for them to gather and build solidarity and resilience against marginalization and experiences with racism and discrimination which are crucial components of the Black spatial imaginary.

As racialization informs valuation of both places and people, Black people may still be devalued and indeed seen as illegitimate occupants in now-revalorized places (Dantzler, 2021). Black people are seen as out of place even as Black history and culture is commodified and exploited to support this place revalorization (Hyra, 2017; Summers, 2019). Accordingly, Black residents in gentrifying neighborhoods may experience increases in discrimination in ways that influence their well-being. For example, in gentrifying Harlem Black residents reported being treated differently by shopkeepers of newly built businesses (Versey et al., 2019). Additionally, Black residents in the Bloomingdale neighborhood of Washington, D.C. described experiences of racial discrimination from white employees in neighborhood restaurants (Helmuth, 2019). A large body of research documents how such experiences with racial discrimination impact health through stress processes as well as negative coping strategies (Davis, 2020; Williams et al., 2019).

Further, newcomers may use their increasing political power to advocate for increases in surveillance and policing practices (Laniyonu, 2018; Sharp, 2014) which have well established adverse health consequences. Often, gentrification is associated with surveillance that targets Black and other non-white residents (Alvaré, 2017). In a predominantly Black community in the mid-Atlantic, for example, newer residents advocated for surveillance and policing to reduce crime and “disorderly” behavior (e.g., residents playing loud music). A group of residents, who were mostly white, formed watch groups to report crime and other issues to the police, often criminalizing Black residents’ behavior. Similar experiences of surveillance were reported in cities like Oakland and Atlanta where Black residents felt marginalized in greened spaces (Anguelovski et al., 2021). Respondents then linked these spaces, originally thought of as spaces of reprieve and rest, to anxiety and stress. Considering the long history of mass criminalization and incarceration of Black people and communities (Hinton & Cook, 2021), increased surveillance may disproportionately impact Black residents in these neighborhoods; increasing stress levels as Black residents experience discrimination while also feeling as if they no longer belong in their neighborhoods (Ellen & Captanian, 2020; Holt et al., 2021). Additionally, heightened police surveillance may increase the risk of physical injury and death at the hands of police officers, or increase psychological distress as people experience or witness harassment (Alang et al., 2017).

Black residents in gentrifying neighborhoods may experience tensions around class as well as race, a point which is highlighted through the fact that historically Black neighborhoods may also be gentrified by Black newcomers. As briefly mentioned above, Mary Patillo’s (2010) work in Chicago examines how middle to upper class Black professionals gentrify a working-class Black community. Despite Black newcomers sharing similar backgrounds with long-term residents, their current social class positionality meant that their vision to uplift the neighborhood was misaligned with the needs and desires of long-term Black residents. In some cases, new residents criminalized the behavior of poor Black residents; attempting to curb what they perceived to be negative behaviors such as barbequing in front yards and socializing on the street and in public parks. These behaviors, which were considered acceptable forms of community building, were now looked down upon and judged. Other scholars also observe how the preferences and actions of middle-class Black residents in gentrifying neighborhoods can run counter to the needs of working-class Black residents (Boyd, 2005; Taylor, 2002). Indeed, Gibbons and Barton (2016) illustrate that Black-led gentrification is related to worse self-rated health for Black residents. The authors hypothesize two possibilities for this result. First, gentrification may not mitigate the effects of disinvestment via racial capitalist policies; thus, cementing disadvantage in these communities that cannot be lessened by the in-migration of wealthier Black residents. Second, long-term Black residents may experience cultural displacement in ways that negatively affect health.

Hypothesized beneficial health impacts of gentrification are often predicated on positive social interactions between these groups—e.g., access to new employment opportunities arising from social ties with more-advantaged neighbors (Ellen & Captanian, 2020; Hyra, 2015). However, collectively, neighborhood social and cultural changes contribute to social segregation between Black and white people, and new and long-term residents. Groups may technically live in proximity to one another, but remain meaningfully socially separated—what Hyra (2017) terms “diversity segregation” (p. 9–10) To the extent that such interactions do not in fact occur, long-term Black residents will not actually gain these ostensible benefits. Ongoing hierarchies of value assigned to racialized bodies may instead limit the extent of long-term Black residents’ potentially health-promoting interactions with newcomers, while instead exposing them to toxic experiences of racial discrimination and classism in their neighborhoods.

Discussion

In spite of its uneven effects on health, gentrification remains a complicated and elusive subject for urban health scholars and policy professionals for many reasons. In this paper, we extend existing literature on gentrification and health by drawing on transdisciplinary scholarship to unpack why and how an ongoing legacy of co-constructing race and property in the United States, via the housing market, may shape gentrification experiences and health impacts for Black communities. We engage with theories of rent gap, racial capitalism, and weathering to clarify why and how Black communities and residents are more vulnerable to gentrification and its adverse health impacts.

Our conceptual framework achieves this goal in two ways. First, placing rent gap theory in conversation with theorizations of racial capitalism reveals how disinvestment is racialized, as Black spaces and Black people are differentiated and devalorized to create opportunities for appropriation and capital accumulation for private and public actors. This disinvestment, as well as experiences with racist policies and practices, creates vulnerabilities (i.e., weathering, lack of loss of social support, limited political power, wealth inequity) for Black communities and residents as gentrification occurs.

Second, our model draws on the existing gentrification literature to describe pathways of displacement, both physical and symbolic, through which unique vulnerabilities to gentrification are produced and shaped to create differential health impacts. While these pathways of displacement are shared by residents across all racial groups, the above experiences and exposures to racial capitalism create susceptibility for Black communities and residents. Both physical and symbolic displacement are likely to adversely impact Black health in multiple ways. By involuntarily removing Black residents from gentrifying neighborhoods, physical displacement may impact health by severing social networks and by displacing residents to neighborhoods with fewer health resources. Symbolic displacement, which we identify through three pathways—physical environment, economic conditions, and sociocultural displacement—may impact health by making new health resources inaccessible for Black residents either economically or socio-culturally, removing long-term health resources from neighborhoods, increasing financial strain, and contributing to feelings of social segregation and exclusion. As discussed in the above pathways, gentrification may not necessarily remediate the harmful health effects of disinvestment but instead may reconstitute harm in new ways, especially for Black residents as they are physically and symbolically displaced from and within gentrifying neighborhoods.

Implications for future research

This project highlights the need for a more methodologically sound way to define and measure gentrification in research as a racialized process. To do this, we believe that both qualitative and quantitative researchers need to uncover ways to center both race and racism in their analysis. While qualitative techniques have been used to capture racialized experiences with gentrification processes, as noted by Rucks-Ahidiana (2021), this research must also unpack how race informs power relations between long-term residents, gentrifiers and other public and private actors. In doing this work, it may be helpful for qualitative researchers to incorporate therapeutic skills (McVey et al., 2015; Perry & Bigelow, 2020) which could be useful in capturing racialized experiences of gentrification while also attending to the psychological needs of research participants, especially those experiencing mental health challenges, who may be processing past and present traumas such as displacement (Lees & Hubbard, 2020).

Moreover, new approaches to quantitative research is another tool that can be used to analyze race and racism in gentrification and health scholarship. Generally, quantitative research uses racial categories as an indicator for experiences of racialization and the historical, political, and social processes that shape daily life (Lett et al., 2022). However, this technique can obscure the structural forces at play, allowing room for the insidious implication that physiologic difference is the reason for health inequities. Scholars such as Lett et al. (2022) suggest multiple ways to move this work forward, including the use of theoretical frameworks that address socio-structural factors. As Fallon (2020) states, we need a more intersectional approach which “provides equal theoretical and empirical weight to the situated structures that produce power and domination” (p. 19–20) Analytically, Lett et al. (2022) note that additional contextual variables that reconstitute racism should also be included in analysis as well as measuring racism alongside other systems of oppression including, but not limited to, sexism, classism, and ableism. These techniques, and many others, can help uncover how race and racism intersect with gentrification processes to produce racialized effects.

Next, research has suggested that gentrification consists of multiple evolving “waves” that transform amidst dynamics of urban change (Hyra et al., 2020). Future research should aim to unpack each wave of gentrification to assess pathways and domains to health. Additionally, gentrification’s effects and harms can exist outside of the confines of gentrified neighborhoods to impact the health of residents in other neighborhoods, e.g., by increasing exposure to environmental hazards (Abel & White, 2011). Research should aim to study how these spillover effects impact resident health, especially in neighborhoods that are under-resourced and minoritized.

Furthermore, although we have focused here on Black people, Marxism may also have limitations in its ability to explain the oppression of other marginalized groups beyond the waged European male laborer, such as Indigenous peoples and women (e.g., Coulthard, 2014; Federici, 2004; Nichols, 2020). Additional work should aim to understand blind spots in the rent gap theory for such groups (see Jackson (2017) for one such example). Given the interrelated nature of racial capitalism with patriarchal and colonial systems of domination (Dorries et al., 2019; Koshy et al., 2022), research should further explore how uneven development and gentrification are shaped by multiple systems simultaneously. Lastly, future research could also similarly apply a post-colonial perspective to explore the relevance and applicability of the planetary gentrification theory and consider how other geopolitical processes shape development outside of the Global North (Lees et al., 2016).

Conclusion

Analyzing the relationship between gentrification and health through a lens of racial capitalism highlights that gentrification is not an independent process but instead a cumulative one of structured disadvantage for Black Americans with compounding health effects. The compounding impacts for Black residents magnifies the need for future health research to fully engage with critical race theory to understand differentiated effects. It also highlights the need for future policy interventions to consider alternative techniques to invest in previously disinvested neighborhoods without harming Black and other non-white communities. More than that, it emphasizes that gentrification should not be classified by class change alone, as race and class are intrinsically linked in urban processes. We hope our conceptual framework can provide a foundation for future research that aims to unpack these racialized differences for other racial groups. We also hope this work urges health scholars to engage in and with transdisciplinary debates, scholarship, and theory to further health equity research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Derek Hyra, Dr. Melody Tulier, Emma Tran, and Marie-Fatima Hyacinthe for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

Support for Shannon Whittaker, MPH was provided by predoctoral fellowships funded by the National Institute of Mental Health under grant number T32MH020031and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under grant number 1F31MD017129-01A1. Shannon Whittaker, MPH also received support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars Program.

Biographies

About the authors

Shannon Whittaker is a doctoral candidate in social and behavioral sciences at the Yale School of Public Health. Her research interests lie at the intersection of place, race, health and history where she examines how social, cultural, and political processes such as gentrification impact the health of marginalized communities of color, particularly Black communities.

Carolyn Swope is a doctoral candidate in urban planning at Columbia University. Her research interests focus on the relationship between housing and health disparities, with particular attention to the role of historical housing policies in shaping inequitable health impacts of present-day gentrification.

Danya Keene is an associate professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Yale School of Public Health. Her research focuses on housing and housing policy as determinants of population health equity.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligation as researchers, Carolyn Swope reports consulting fees at Delos Living, a wellness real estate and technology company whose work and offerings include the design of indoor spaces to improve the health and wellness of occupants of the space. Shannon Whittaker and Danya Keene have no competing interests to report.

Contributor Information

Shannon Whittaker, Yale School of Public Health.

Carolyn B. Swope, Columbia University

Danya Keene, Yale School of Public Health.

References

- Abel TD, & White J (2011). Skewed riskscapes and gentrified inequities: Environmental exposure disparities in Seattle, Washington. American Journal of Public Health, 101(S1), S246–S254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, & Hardeman R (2017). Police brutality and black health: Setting the agenda for public health scholars. American Journal of Public Health, 107(5), 662–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvaré MA (2017). Gentrification and resistance: Racial projects in the neoliberal order. Social Justice, 44(2–3 (148)), 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I (2015). Healthy food stores, greenlining and food gentrification: Contesting new forms of privilege, displacement and locally unwanted land uses in racially mixed neighborhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1209–1230. 10.1111/1468-2427.12299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I (2016). From toxic sites to parks as (green) LULUs? New challenges of inequity, privilege, gentrification, and exclusion for urban environmental justice. Journal of Planning Literature, 31(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I, Cole HV, O’Neill E, Baró F, Kotsila P, Sekulova F, Del Pulgar CP, Shokry G, García-Lamarca M, & Argüelles L (2021). Gentrification pathways and their health impacts on historically marginalized residents in Europe and North America: Global qualitative evidence from 14 cities. Health & Place, 72, 102698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I, Connolly J, & Brand AL (2018). From landscapes of utopia to the margins of the green urban life: For whom is the new green city? City, 22(3), 417–436. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I, Connolly JJ, Garcia-Lamarca M, Cole H, & Pearsall H (2018). New scholarly pathways on green gentrification: What does the urban ‘green turn’ mean and where is it going? Progress in Human Geography, 0309132518803799. 10.1177/0309132518803799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R (2015). Losing one’s place: Narratives of neighbourhood change, market injustice and symbolic displacement. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(4), 373–388. 10.1080/14036096.2015.1053980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banzhaf HS, & McCormick E (2007). Moving beyond cleanup: Identifying the crucibles of environmental gentrification. (National Center for Environmental Economics Working Paper No. 07-02). https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/201412/documents/moving_beyond_cleanup_identifying_the_crucibles_of_environmental_gentrification.pdf

- Bennett L, & Reed A Jr. (1999). The new face of urban renewal: The near north redevelopment initiative and the Cabrini-Green neighborhood. In Reed A Jr. (Eds.), Without justice for all: The new liberalism and our retreat from racial equity (pp. 175–211). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, & Glass T, (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Berkman LF, & Kawachi I, (Eds), Social Epidemiology. (pp. 137–173). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Betancur JJ (2002). The politics of gentrification: The case of West Town in Chicago. Urban Affairs Review, 37(6), 780–814. 10.1177/107874037006002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar NA, Kumar M, & Richman L (2020). Defining gentrification for epidemiologic research: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 15(5), e0233361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binet A, Zayas del Rio G, Arcaya M, Roderigues G, & Gavin V (2021). ‘It feels like money’s just flying out the window’: Financial security, stress and health in gentrifying neighborhoods. Cities & Health, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe A, & Wright WJ (2019). The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(1), 8–26. 10.1177/0263775818805102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M (2005). The downside of racial uplift: Meaning of gentrification in an African American neighborhood. City & Society, 17(2), 265–288. 10.1525/city.2005.17.2.265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M (2008). Jim Crow nostalgia: Reconstructing race in Bronzeville. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brand AL, & Miller C (2020). Tomorrow I’ll be at the table: Black geographies and urban planning: A review of the literature. Journal of Planning Literature, 35(4), 460–474. 10.1177/0885412220928575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, & Clark SL (2005). Homeplace and housing in the lives of low-income urban African American families. In McLoyd VC, Hill NE & Dodge KA (Eds.), African American Family Life: Ecological and Cultural Diversity (pp. 166–188). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N (2018). Feeding or starving gentrification: The role of food policy. (Policy Brief). CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute. New York, NY. https://cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Policy-Brief-Feeding-or-Starving-Gentrification-20180327-Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cole HV, Triguero-Mas M, Connolly JJ, & Anguelovski I (2019). Determining the health benefits of green space: Does gentrification matter? Health & Place, 57, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard GS (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press. 10.5749/minnesota/9780816679645.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croff R, Hedmann M, & Barnes LL (2021). Whitest city in America: A smaller Black community’s experience of gentrification, displacement, and aging in place. The Gerontologist, 61(8), 1254–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzler PA (2021). The urban process under racial capitalism: Race, anti-Blackness, and capital accumulation. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City, 0(0), 1–22. 10.1080/26884674.2021.1934201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darling E (2005). The city in the country: Wilderness gentrification and the rent gap. Environment and Planning A, 37(6), 1015–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M (2008). Spoiled mixture: Where does state-led “positive” gentrification end? Urban Studies, 45(12), 2385–2405. 10.1177/0042098008097105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M, & Lees L (2010). New-build gentrification: Its histories, trajectories, and critical geographies. Population, Space and Place, 16(5), 395–411. 10.1002/psp.584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B (2020, February 25). Discrimination: A social determinant of health inequities. Health Affairs. 10.1377/hblog20200220.518458/full/ [DOI]

- Dawes DE (2020). The political determinants of health. Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes DE, Donnell M, Amador C, Standifer M, Valle M, Houston S, McKinney T, & Dunlap N (2022). The political determinants of health and health equity in the aging population. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 46(1),1–17. [Google Scholar]

- De Verteuil G (2011). Evidence of gentrification-induced displacement among social services in London and Los Angeles. Urban Studies, 48(8), 1563–1580. 10.1177/0042098010379277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis J (2004). Unmaking Goliath: Community control in the face of global capital. Routledge. [Google Scholar]