Abstract

Effective iron chelation is crucial for preventing morbidity and mortality in transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia major. While oral chelation is the preferred mode of administration, heavily iron-overloaded patients often require combination therapy. Although desferoxamine and deferiprone are commonly recommended, a combination of two oral chelators—deferasirox and deferiprone, offers a more convenient alternative. This study evaluates the efficacy and safety of combination oral chelation in pediatric patients with severe iron overload. Children with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia major and persistently high serum ferritin levels (> 2500 µg/dL) for more than six months despite maximum-dose deferasirox (40 mg/kg/day) were initiated on combination chelation with deferiprone. Serum ferritin levels were monitored at six-month intervals to assess treatment efficacy. Among 130 regularly followed patients, 27 met the criteria for combination chelation. A significant reduction in serum ferritin levels was observed, decreasing from 4277 ± 1885 µg/dL at baseline to 3242 ± 1110 µg/dL at six months (p = 0.003) and further to 2985 ± 1116 µg/dL at twelve months (p = 0.018). No significant adverse effects were noted during the study period. Combination chelation with deferasirox and deferiprone is an effective and well-tolerated strategy for managing severe iron overload in children with beta-thalassemia major. This approach provides a practical alternative to injectable therapies and may improve adherence and treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Iron chelation, Beta-thalassemia, Combined chelation

Introduction

The thalassemias are a group of anemias that result from inherited defects in the production of hemoglobin due to ineffective bone marrow erythropoiesis and excessive red blood cell hemolysis. They are among the most common genetic disorders worldwide, occurring more frequently in the Mediterranean region, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and West Africa.

Iron overload in thalassemia is largely due to regular red blood cell transfusions in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients or due to increased absorption of iron through the gastrointestinal tract in non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia [1]. Iron overload is inevitable in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients causing toxicity in the form of heart failure, cirrhosis, growth retardation and multiple endocrine abnormalities [1].

Chelation therapy balances this excess iron by increasing the excretion in urine and or feces. Convenience of use and tolerability of individual chelators are important considerations for the successful management of iron overload as these are therapies that need to be taken over many years. The term ‘combination therapy’ refers to the use of multiple chelators to improve outcome when monotherapy has become ineffective [2]. The standard recommended combination chelation for highly iron-overloaded patients includes desferioxamine and deferiprone [1–3]. As desferioxamine is injectable and requires continuous subcutaneous infusion, an alternative with only oral iron chelators would be ideal. There are emerging studies on combination oral chelation with deferasirox (DFX) and deferiprone (DFP) [4–7]. In this study, we assess the efficacy and tolerability of iron chelation with combination deferasirox and deferiprone in children with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia major.

Materials and methods

A prospective observational study was conducted at the Thalassemia clinic in the Division of Pediatric Hemato-Oncology at a tertiary level university teaching hospital over 2 years. Deferasirox as a single oral iron chelator was started for all transfusion-dependent children once serum ferritin was above 1000 ug/dL. Serum ferritin was monitored every 3–6 months. Patients with serum ferritin levels persistently above 2500 ug/dL over a period of 6 months, while on maximum dose of deferasirox (DFX) (40 mg/kg/day) were included in the study. All patients included in the study were started on deferiprone (DFP) along with deferasirox (DFX). DFX dose was continued at maximum dose (40 mg/kg/day) and DFP dose was started at 50 mg/kg/day. Serum ferritin levels was monitored at 6 monthly intervals. Patients were monitored for toxicity in the form of arthralgia/arthritis and cytopenias for deferiprone and renal functions and transaminases for deferasirox. Intolerance to deferasirox in the form of gastrointestinal symptoms of vomiting/abdominal pain were monitored. T2* MRI was not available at the time of the study due to cost concerns. Adherence to treatment was confirmed by requesting parents to carry the blister packs during assessments. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS for windows version 22.0. Fisher exact test and Chi-square test used for the comparison of categorical variables. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (Figs. 1 and 2).

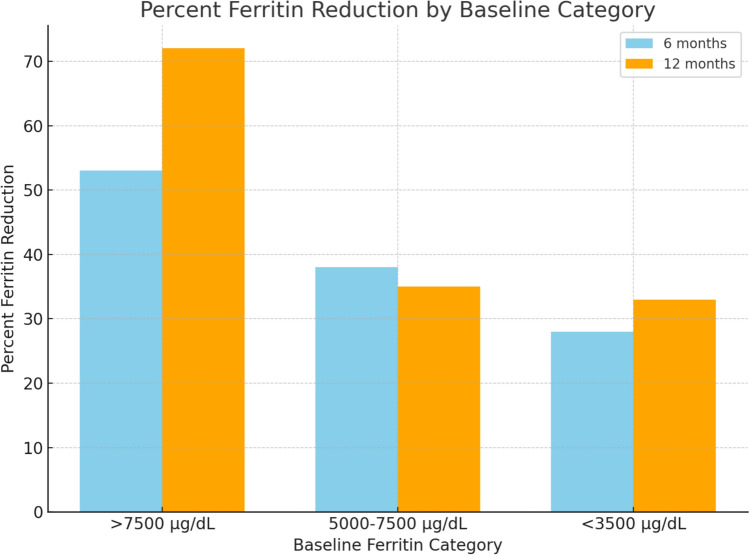

Fig. 1.

Percent serum ferritin reduction by baseline category

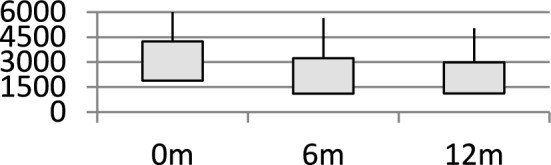

Fig. 2.

Box Plot: Graph showing changes in serum ferritin levels with combination chelation

Results

Among 130 children (83 boys and 47 girls) on regular follow-up at our hospital, 27 were included in the study as they met criteria for heavy iron overload. Mean age of children was 8.5 years. Baseline mean Serum ferritin levels were 4277 ug/dL ± 1885 (median: 4241). On combination chelation therapy, the mean serum ferritin level decreased significantly to 3242 ± 1110 µg/dL at 6 months (95% CI: 2834–3650, p = 0.003, median: 3081) and further to 2985 ± 1116 µg/dL at 12 months (95% CI: 2566–3404, p = 0.018, median: 2750). Stratified analysis showed that patients with initial serum ferritin levels above 7500 µg/dL had a 53% reduction at 6 months (95% CI: 45%–61%) and a 72% reduction at 12 months (95% CI: 63–81%). Patients with baseline serum ferritin between 5000 and 7500 µg/dL showed a reduction of 38% at 6 months (95% CI: 30–46%) and 35% at 12 months (95% CI: 28–42%), while those with levels below 3500 µg/dL had reductions of 28% (95% CI: 22–34%) and 33% (95% CI: 27–39%) at 6 and 12 months, respectively. While no formal adjustments were made for age, sex, or transfusion burden, these factors may influence serum ferritin trends. The significant p values at both time points highlight the efficacy of combination chelation, particularly in patients with severe iron overload. None of the children needed to stop either deferiprone or deferasirox due to bone marrow suppression, hepatic failure, renal dysfunction arthralgia or arthritis (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Demographic details

| Total number of Thalassemia major children getting transfusion at our unit | 130 |

| Mean age | 8.5 years |

| Male: female | 64%: 36% |

| Children who received Combination chelation | 27 (male: female = 16:9) |

| Mean pre transfusion Hemoglobin | 8.3 g/dL |

| Mean volume of transfusion | 11.5 ml/kg/month |

| Mean Serum ferritin level at start of combination chelation | 4277 ug/dL (median:4241, SD: 1885) |

| Mean Serum ferritin at 6 months | 3242 ug/dL (SD: 1110) |

| p = 0.003 | |

| Mean Serum ferritin at 12 months | 2985 ug/dL (median:SD: 1116) |

| p = 0.018 |

This table describes the demographic details of the study population

Table 2.

Change in serum ferritin levels

| Initial serum ferritin level | % fall at 6 months | % fall at 12 months |

|---|---|---|

| < 3500 | 28 | 33 |

| 3500–5000 | 20 | 18 |

| 5000–7500 | 38 | 35 |

| > 7500 | 53 | 72 |

This table shows the change in serum ferritin levels in percentage from baseline at 6 months and at 12 months

Discussion

Combination chelation therapy has been used to improve outcomes if monotherapy proves inadequate to control iron overload, particularly in the heart and liver. Most commonly used regimes give DFP daily at standard doses, combined with varying frequency and dosing of DFO [1]. More recently, combinations of DFX with DFO, or DFX with DFP have been evaluated [2, 3]. Our study has shown significant improvement in Serum ferritin within 6–12 months with a significant decrease in serum ferritin within these relatively short time points. Recent studies have suggested combination of deferasirox and deferiprone to be an effective regimen [4–7]. Previously studies showed clinical improvement with combination of desferoxamine and deferiprone in cardiac and endocrine complications of iron overload in 52 patients not responding to single chelator use [8]. Combination of deferiprone with subcutaneous desferoxamine was more effective to lower serum ferritin and improved echocardiographic parameters with no statistically significant differences in mortality or cost between the groups [9–11]. Though this method of combined chelation remains the gold standard and recommended method for heavily iron-overloaded patients, it does not lend itself to ease of administration and hence poor adherence. This is especially true in the developing world where cost of care if often borne by the parents. Two oral chelators used in this study was well accepted and well tolerated.

The increased risk of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome in iron-overloaded patients with thalassemia undergoing an allogeneic stem cell transplant is well documented [12, 13]. With accessibility to curative options for stem cell transplant improving in the developing world also, optimal iron chelation prior to transplant is important. In this setting, a regimen with improved adherence, and equal efficacy is preferred.

Though desferioxamine has been the gold standard in iron chelation, studies have demonstrated comparable amounts of iron excretion when deferiprone was compared to desferoxamine [14, 15]. Deferiprone results in more significant reduction in iron levels in those with a higher iron burden [16]. It is interesting to note that in our study those with a higher serum ferritin level had a proportionately greater drop in serum ferritin. This observation is similar in other studies on combination of DFP and DFX [16]. The major limitation of our study is the inaccessibility to T2* MRI due to high cost for most of our patients. This limitation notwithstanding, the trend of serum ferritin showing statistically significant decreases is reassuring. We acknowledge that T2 MRI* is the gold standard for assessing iron overload in organs such as the heart and liver. However, due to resource constraints in developing and underdeveloped countries, access to T2 MRI is limited* and often unavailable for routine monitoring in many clinical settings, including ours.

Given these limitations, serum ferritin remains the most widely used and accessible biomarker for assessing iron burden in resource-limited settings. While it has known variability and is influenced by factors such as inflammation, it still provides valuable trends in iron overload management and is routinely used in clinical decision-making.

As a retrospective audit, this study aimed to evaluate the practical efficacy and safety of combination therapy in a cohort that required it. While a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or a matched control study would provide higher-level evidence, real-world audits are critical in resource-limited settings to guide treatment modifications. Instead of a control group, we used baseline pre-treatment serum ferritin levels and trends over time as internal references to assess efficacy. This allowed us to demonstrate the impact of combination therapy within the patient population, reducing variability due to interpatient differences.

Combination oral therapy is an effective, acceptable and cheaper mode of chelation therapy which may be utilized as a method of chelation in developing countries where iron burden is high [6, 7, 16, 17].

Conclusions

Combination chelation with deferiprone and deferasirox can be considered a viable option for patients not responding to a single chelator, particularly in resource-limited, rural, and developing settings where access to intensive chelation therapies may be restricted. This approach offers an effective and convenient alternative, enhancing treatment adherence and ensuring better long-term outcomes in managing iron overload. The availability of an entirely oral regimen is especially beneficial in settings with limited healthcare infrastructure, reducing the need for frequent hospital visits and invasive treatments.

Author contribution

For the manuscript titled: “Efficacy of Combination Chelation with Deferasirox and Deferiprone in Children with Beta Thalassemia Major: An Audit from a Unit in the Developing World”. VJ contributed to data collection, research, and data analysis. AP contributed to data collection, research, and data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

In accordance with institutional guidelines, this study was approved by the St John’s Medical College Institutional ethical research board. Given the retrospective nature of the study, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the ethics committee. However, patient confidentiality and data anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Porter J, Taher A, Viprakasit V. Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia. 3rd ed. Cyprus: Thalassemia International Federation Publication; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwiatkowski JL. Current recommendations for chelation for transfusion-dependent thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1368(1):107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgna-Pignatti C, Marsella M. Iron chelation in thalassemia major. Clin Ther. 2015;37(12):2866–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voskaridou E, Christoulas D, Terpos E. Successful chelation therapy with the combination of deferasirox and deferiprone in a patient with thalassaemia major and persisting severe iron overload after single-agent chelation therapies. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(5):654–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alavi S, Sadeghi E, Ashenagar A. Efficacy and safety of combined oral iron chelation therapy with deferasirox and deferiprone in a patient with beta-thalassemia major and persistent iron overload. Blood Res. 2014;49(1):72–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Totadri S, Bansal D, Bhatia P, et al. The deferiprone and deferasirox combination is efficacious in iron overloaded patients with β-thalassemia major: a prospective, single center, open-label study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(9):1592–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomber S, Jain P, Sharma S, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of oral iron chelators and their novel combination in children with thalassemia. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53(3):207–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmaki K, Tzoumari I, Pappa C, et al. Normalisation of total body iron load with very intensive combined chelation reverses cardiac and endocrine complications of thalassaemia major. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:466–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maggio A, Vitrano A, Capra M, et al. Long-term sequential deferiprone desferoxamine versus deferiprone alone for thalassaemia major patients: a randomized clinical trial. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daar S, Pathare AV. Combined therapy with desferrioxamine and deferiprone in beta thalassemia major patients with transfusional iron overload. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Origa R, Bina P, Agus A. Combined therapy with deferiprone and desferrioxamine in thalassemia major. Haematologia. 2005;90:1309–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morado M, Ojeda E, Garcia-Bustos J, et al. BMT: serum ferritin as risk factor for veno-occlusive disease of the liver. Prospec Cohort Stud Hematol. 2000;4:505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilo F, Angelucci E. Iron toxicity and hemopoietic cell transplantation: time to change the paradigm. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2019;11(1): e2019030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olivieri NF, Koren G, Hermann C, et al. Comparison of oral iron chelator L1 and desferoxamine in iron-loaded patients. Lancet. 1990;336:1275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins AF, Fassos FF, Stobie S, et al. Iron-balance and dose-response studies of the oral iron chelator 1,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxypyrid-4-1 (L1) in iron-loaded patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 1994;83:2329–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DivakarJose RR, Delhikumar CG, Kumar R, et al. Efficacy and safety of combined oral chelation with deferiprone and deferasirox on iron overload in transfusion dependent children with thalassemia—a prospective observational study. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88(4):330–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elalfy MS, Adly AM, Wali Y, Tony S, Samir A, Elhenawy YI. Efficacy and safety of a novel combination of two oral chelators deferasirox/deferiprone over deferoxamine/deferiprone in severely iron overloaded young beta thalassemia major patients. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95(5):411–20. 10.1111/ejh.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.