Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a prevalent condition with increasing incidence and mortality rates. The identification of robust prognostic gene signatures remains an unmet clinical need in CRC treatment. In this study, data from the GEO and TCGA databases were utilized to identify 2,779 upregulated and 2,629 downregulated genes in CRC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. WGCNA analysis highlighted the MEbrown module, which comprised 1,639 genes that exhibited strong correlations with CRC progression. Subsequently, an intersection analysis was conducted to further refine the candidate gene set, resulting in the selection of 926 differentially expressed CRC-related genes for subsequent analysis. Through univariate Cox regression, LASSO regularization, and multivariate Cox regression, a five-gene prognostic signature (TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, CXCL13) was established, demonstrating consistent predictive accuracy in external (GSE32323) and internal validation cohorts. Mutational profiling showed predominant missense mutations across signature genes, with TIMP1 exhibiting the highest variant allele frequency. Functional enrichment analysis linked TIMP1 to critical CRC pathways including type I interferon receptor binding, oxidative phosphorylation, and Notch signaling pathways. High expression of TIMP1 was associated with poor prognosis in patients with CRC. Additionally, using siRNA technology, the impact of TIMP1 on cellular proliferation, metastasis and apoptosis in CRC cell lines (HCT116 and HT29) was investigated, showing that TIMP1 knockdown significantly inhibited CRC cell proliferation, metastasis, and promoted apoptosis. These experimental results were consistent with the conclusions drawn from the bioinformatics analysis. This research presents a prognostic risk model for CRC, further highlights TIMP1 as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for the disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-03301-9.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Prognostic biomarkers, WGCNA, Bioinformatics, TIMP1

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [1–3]. The American cancer society (ACS) estimates 152,810 new cases of CRC in 2024 [4]. The CRC causes for approximately 1.5 million deaths annually [5–7]. Driven by the increasing complexity of disease biology, the emergence of novel therapeutic approaches, and the critical need for personalized treatment strategies, the landscape of CRC treatment continues to evolve dynamically.

Current treatment modalities for CRC encompass a range of strategies, including targeted therapy, immunotherapy, surgical treatment and integrated treatment plans. In terms of targeted therapy, anti-angiogenic agents such as Regorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, have been approved for third-line treatment in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer [8, 9]. According to the CORRECT trial, Regorafenib significantly extended overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), but it was accompanied by relatively high toxicities, mainly including fatigue, hand-foot syndrome, and hypertension. In the realm of immunotherapy, the emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has marked a revolutionary shift in oncological therapeutics, providing substantial clinical benefits for CRC patients [10]. ICIs like Pembrolizumab have emerged as standard care for patients with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) CRC [11, 12]. Data from multiple clinical trials indicate that Pembrolizumab as first-line therapy can substantially improve PFS. However, immunotherapy remains largely ineffective for patients with microsatellite stable (MSS) CRC, as most exhibit resistance to these treatments. Thus, it is imperative to identify novel biomarkers or targets for “cold tumors” to improve patient outcomes. Furthermore, an integrated treatment strategy is pivotal in CRC management. Comprehensive molecular profiling, encompassing MSI status, KRAS/BRAF mutation status, and other biomarkers, provides a robust foundation for developing personalized treatment regimens and serves as the cornerstone for precision medicine [13, 14]. In addition to the above-mentioned treatment strategies, currently, surgical intervention continues to serve as the principal modality and a critical component in the comprehensive management of CRC, especially for patients with non-metastatic CRC [15].

Treatment and early diagnosis of CRC have improved significantly in recent years; However, many patients remain asymptomatic in the early stages, and approximately 50–60% of patients with CRC often have multiple metastases. Following standard therapy, the 5-year survival rate for these patients is only 12–19%, with a high recurrence rate [16]. Molecular studies have identified numerous genetic alterations associated with colon carcinogenesis; however, the precise genetic changes driving the initiation and progression of CRC remain poorly understood [17]. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop novel biomarkers and models that can accurately predict outcomes and guide the clinical management of CRC. Meanwhile, investigating the impact of prognostic genes on CRC and their underlying mechanisms is essential.

In the present study, a robust prognostic risk model based on five characteristic genes (TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, and CXCL13) was developed, which demonstrated excellent performance in predicting OS in CRC patients. Furthermore, a nomogram was constructed to provide a quantitative tool for predicting the survival outcomes of CRC patients based on clinical variables and risk scores. In vitro validation revealed that TIMP1 knockdown in HCT116 and HT29 cell lines suppressed cell proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities while promoting apoptosis. Further analysis confirmed the high expression of TIMP1 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with CRC. In summary, this study identified prognostic biomarkers for CRC by integrating data from relevant public databases, employing comprehensive bioinformatics analysis approaches, and conducting experimental validation. The findings contribute to the foundation of prognostic analysis and provide valuable insights into the role of TIMP1 in CRC.

Materials and methods

Acquirement of the data of the CRC patients

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-CRC dataset (training cohort) including RNA-seq data and clinical information of 51 normal tissue samples and 606 CRC tissue samples with survival information (version 3.4-0), was downloaded from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Two independent cohorts (GSE39582 and GSE32323) were acquired from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). GSE39582 dataset, including a total of 556 CRC samples containing survival information, were used as the validation set. GSE32323 dataset, which consisted of 17 CRC tissue samples and 17 normal tissue samples, was utilized to analyze the expression of the characteristic genes.

Identification of differentially expressed CRC-related genes (DE-CRC-related genes)

The “DESeq2” package (version 1.36.0) [18] was used for differential expression analysis to obtain the DEGs between the normal and CRC tissue samples. The “ggplot2” (version 3.3.0) (https://academic.oup.com/biometrics/article/67/2/678/7381027?Login.

=false) and “pheatmap” packages (version 0.7.7) (https://cran.ms.unimelb.edu.au/web/packages/pheatmap/pheatmap.pdf) were adopted to plot the volcano map and heatmap to visualize DEGs, respectively. Gene modules with comparable expression patterns have been identified using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) [19] and the relationship between modules and particular traits has been examined. In this study, we used the R package “WGCNA” (version 1.71) to create a gene co-expression network for CRC in the TCGA-CRC dataset. For the network construction to be reliable, abnormal samples were first eliminated. Then the appropriate threshold for network construction was selected, and a minimum number of genes per module of 30. The link between clinical traits (CRC and normal tissues samples) and module attributes was examined using the Pearson correlation analysis, and the module with the highest correlation was identified as the module most closely related to CRC. The “VennDiagram” package (version 1.7.3) [20] was applied to visualize the DE-CRC-related genes.

Functional analysis and protein-protein interactions (PPI) network of DE-CRC-related genes

Based on DE-CRC-related genes, the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database (http://string-db.org) was applied to establish the PPI network’s structure, where the results were visualized via Cytoscape (version 3.9.1). Then the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) database was adopted to perform Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis on these DE-CRC-related genes and visualize the results by the R package “ggplot2” (version 3.3.0). KEGG is a publicly available database on signal transduction pathways [21]. Enrichment analysis was used to determine the candidate genes’ connections to pertinent biochemical metabolic and signal transduction pathways [22].

Construction and validation of the prognostic risk model

By using univariate Cox analysis of DE-CRC-related genes in the training set, the prognosis-related genes were acquired (P < 0.03). Subsequently, the most predictive characteristic genes were identified by the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) [23] analysis. The model’s performance was assessed using 10-fold cross-validation by calculating the biased likelihood deviation [type.measure = ‘deviance’] for each fold and selecting the regularization parameter lambda.min that minimizes the cross-validation error. Finally, multivariate Cox regression analysis was conducted sequentially to further refine the gene signatures. The R package “biomaRt” (version 2.52.0) [24] was applied to visualize the localization of the characteristic genes on the chromosomes. Subsequently, risk score of each CRC patient was calculated based on the formula:

The training set of CRC patients was divided into two groups based on the median risk score. The difference in OS between the two groups was then displayed using Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves. The “timeROC” package (version 0.4) [25] was applied to display the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to perform an assessment of the prognostic capability of the prognostic model. Meanwhile, the stability of this prognostic risk model was investigated in the external GSE71014 dataset and the internal validation set. In addition, decision curve analysis run by the “DecisionCurve” package (version 1.3) (https://github.com/cran/DecisionCurve?%20tab=readme-ov-file) and principal component analysis were used to further assess the predictive power of the prognostic risk model. Finally, whether these characteristic genes were differentially expressed in GSE32323 was investigated.

Assessment of the nomogram model

To determine if clinicopathological characteristics (age, mismatch repair protein expression deficiency, lymphovascular infiltration, pathologic M, pathologic N, tumor stage, tumor stage and risk scores were independent predictive factors for CRC patients, univariate and multifactorial Cox analyses were performed. The “rms” package (version 5.4-1) (http://mirror.psu.ac.th/pub/cran/web/packages/rms/rms.pdf) was adopted to construct the nomogram to predict survival probability based on independent prognostic criteria. Both the calibration and the ROC curves were adopted to validate whether the nomogram can be used as an optimal model for clinical decision-making.

The analysis of characteristic genes

The mutation frequencies of all genes in the TCGA-CRC dataset were analyzed using the maftools package (version 2.12.0). The CNV status of characteristic genes was also analyzed through the gene set cancer analysis (GSCA) database. We explored the biological functions enriched by genes associated with characteristic genes through GSEA. The expression of characteristic genes in CRC/normal tissues was assessed by the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database. The UALCAN database (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) was utilized to study the expression of TIMP1 in colorectal cancer patients. The relationship between expression of TIMP1 and survival of patients with colorectal cancer was analyze through Kaplan-Meier analysis (https://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?%20p%E2%80%89=%E2%80%89background).

Cell culture

HCT116 and HT29 human colorectal cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. All cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 ℃. Table 1

Table 1.

Sequences of SiRNA used in this study

| Name | Sequences |

|---|---|

| siRNA-TIMP1 | Sense: 5′⁃CCAGCGUUAUGAGAUCAAGAUTT⁃3′ |

| Antisense: 5′⁃AUCUUGAUCUCAUAACGCUGGTT⁃3′ | |

| siRNA-Control | Sense: 5′⁃CCGGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCAC⁃3’ |

| Antisense: 5′⁃AATTCAAAAATTCTCCGAACGT⁃3′ |

Cell transfection

The function of TIMP1 in CRC cells was examined by knocking-down TIMP1 expression using siRNA transfection. siRNAs specifically targeting TIMP1 were all constructed by GenePharma Inc (China). CRC cells were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (13778030, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 4 × 105 cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates. When the cell density reached 70%, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium. Next, Subsequently, Lipofectamine™ 3000 and siRNAs were diluted with Opti-MEMTM medium (31985070, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in tube A and B, respectively. the liquids in tube A and B were mixed in equal proportions, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Then the mixture was dropped into the corresponding wells and incubated for 6 h. Afterward, each well was supplemented with FBS containing 10% medium and incubated for 24 h. The silencing effect of TIMP1 was analyzed by qRT-PCR and WB to detect the expression level of TIMP1 and STING in CRC cells. Information on the sequences of siRNA is summarized as follows in Table 1:

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from tumor cells was extracted utilizing the Eastep Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega, catalog number LS1040, America), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted RNA was then reverse transcribed using the HyperScript RT SuperMix (APExBIO, catalog number K1074, America), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted with the Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen, catalog number 11202ES08, China) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (ABI, catalog number 4,351,107, America). Each reaction was conducted in triplicate. Data analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism software. Relative mRNA values were calculated by the ΔΔCt method. GAPDH was used as an internal normalization control.

Western blotting

CRC cells were seeded in 6-well culture plate and incubated overnight before transfection. After 48 h of siRNA transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared from treated and untreated cells using cold Nonidet P-40 buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche, catalog numbers 04 906 837 001 and 04 693 132 001, Switzerland). Protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog number 23,227, America).

Equal protein amounts were loaded onto 7.5–12% polyacrylamide gels (EpiZyme Biotechnology, PG212, China), transferred to PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, IPVH00010, America), and blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 2 h. The PVDF membrane was incubated with the specific primary antibody, and the secondary antibody. Finally, signals were detected using Bio-Rad’s chemiluminescence enhancer reagent.

MTT assay

HCT116 and HT29 Cells were digested using trypsin, resuspended with fresh complete medium, and counted 5 × 103 cells per well were inoculated in 96-well cell plates for 24 h. At each detection point, 10 µL MTT reaction solution (298-93-1, Solarbio, China) was added to each well. Then, the plates were incubated in the incubator for 2 h. Subsequently, 100 µL DMSO was added in each well after discarding the supernatant. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured by a microplate reader (BMG Spectrostar, BMG Labtech, Germany). All experiments were performed in triplicate. The results were analyzed by Prism 9.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Colony forming assay

Approximately 500 cells were seeded in six-well plates and cultured at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, and the medium was changed every 72 h. After 12 days, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with 0.1% crystalline violet staining solution (G1062, Solarbio, China) for 15 min. Colonies were then photographed. All experiments were performed in triplicate. ImageJ software was utilized to count the number of stained colonies [26].

Invasion and migration assays

For the invasion assay, transwell upper chambers were precoated with Matrigel (C0372, Beyotime, China). In the 8-µm pore chamber (353097, BD Falcon, USA) coated with Matrigel containing serum free medium, equal numbers of cells (5 × 104 per well) were plated. As an attractant, complete culture media was added to the bottom chamber. Forty-eight hours later, cells in the upper chamber were wiped off. Migrated and invaded cells on the lower membrane surface were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and photographed. ImageJ software was utilized to count the number of migrated and invaded cells. Migration assay was carried out the same as invasion assay, but without the utilization of Matrigel.

Cell apoptosis analysis

The Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (E-CK-A211, Elabscience, China) was used to perform apoptosis analysis according to the instructions. HCT116 and HT29 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (4 × 105/well). After 12 h, the cells were attached to the dishes. The intervention was performed for 36 h, then culture medium was collected and the cells were rinsed with cold 1 × PBS and collected. Annexin V-FITC and Propidium iodide were added to the cells, incubated at room temperature and protected from light for 20 min, the stained cells were detected under BD FACSAria IIIu. The apoptosis was determined using the FlowJo software (version 10.10, USA).

Statistical analysis

All experiments and analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reliability. Numerical data are displayed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, USA). The statistical significance of the differences was analyzed by Student’s t test, unpaired t test, and one-way ANOVA according to the test of homogeneity of variances. Statistical significance was set as follow: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

Results

Acquirement of DE-CRC-related genes and WGCNA construction and identification of key modules

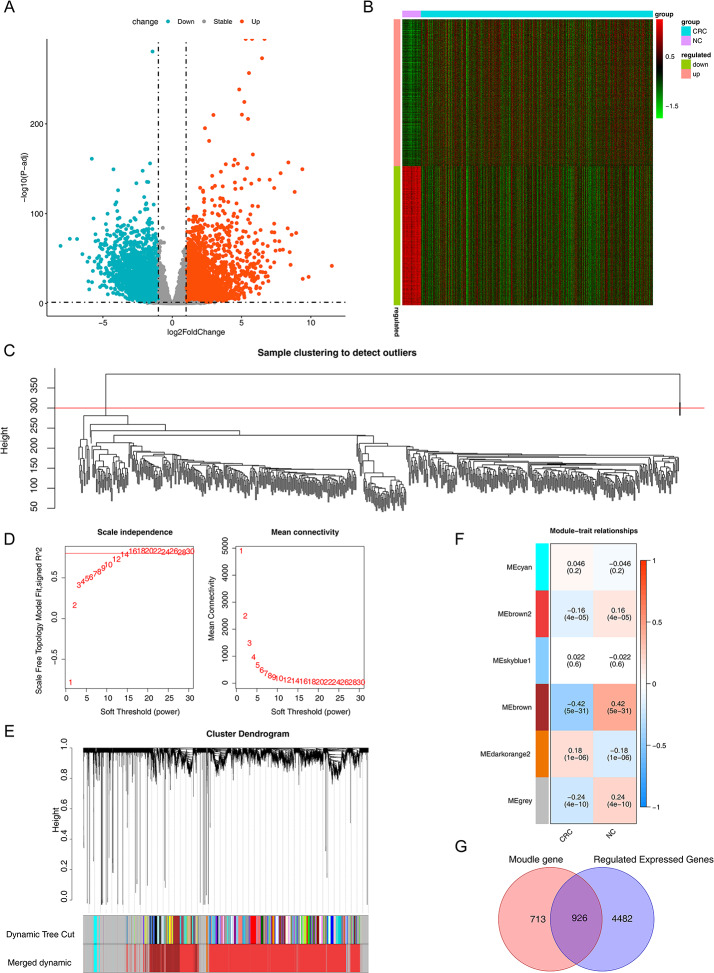

A total of 5408 DEGs (2779 genes up-regulated and 2629 genes down-regulated) were screened between the CRC/normal tissue samples in the TCGA-CRC dataset. The selection of these DEGs was based on criteria of |log2FC|>1 and adj. p < 0.05. The volcano plot and heatmap visualizing the differential expression of CRC-related DEGs were presented (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

Identification of the differentially expressed genes and DE-CRC-related genes in the TCGA cohort. A Volcano plot, is used to identify DEGs between tumor and normal tissues; B Heatmap visualization of differentially expressed genes; C Diagram of sample clustering; D. Chart of genes scale-free distribution; E. Diagram of modules; F. The heat map of module-trait relationships. The MEbrown module was identified as the key module associated with CRC; G. Venn diagram of DEGs and key module genes intersections

Subsequently, we selected genes with expression values greater than 1, conducted sample clustering analysis on them, and removed outlier samples to ensure the accuracy of subsequent analyses (Fig. 1C). Two outlier samples (TCGA-AA-3947–01 A and TCGA-CM-4748–01 A) were excluded from the sample clustering analysis. β value of 16 was chosen to ensure network conformity to a scale-free distribution (Fig. 1D). With CRC as the trait, six modules were identified (Fig. 1E). The heatmap of module-trait relationships was obtained by Spearman analysis (Fig. 1F). To screen the gene modules related to CRC, the correlations between each module and CRC were further analyzed. In the heatmap of the correlation between the modules and traits (as shown in Fig. 1F), only the MEbrown module among the six modules had an absolute value of correlation exceeding 0.4. Therefore, the MEbrown module was selected as the key module related to CRC. This module comprises a total of 1,639 genes, among which 926 genes related to CRC exhibited differential expression (Fig. 1G).

Functional analysis and PPI network of 926 DE-CRC-related genes

Based on the STRING database, we retrieved 923 out of 926 genes to construct the PPI network (Fig. 2A). These genes were enriched to a total of 1022 GO entries and 27 KEGG pathways. According to the biological processes (BP) analysis, these genes were connected to cell adhesion and cell communication (Fig. 2B). In the case of cellular component (CC), these genes were engaged in plasma and neuron part (Fig. 2C). Regarding molecular function (MF), these genes were involved in transmembrane signaling receptor activity, metal ion transmembrane transporter activity, and G-protein coupled peptide receptor activity (Fig. 2D). These intersecting genes were also enriched in cGMP-PKG signaling pathway, circadian rhythm, cAMP signaling pathway, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and other pathways related to CRC (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

GO and KEGG analyses of all differentially expressed genes in CRC. A PPI network; B Go analysis in biological process of DE-CRC-related genes; C Go analysis in cellular component of DE-CRC-related genes; D Go analysis in molecular function of DE-CRC-related genes; E KEGG [27–29] pathway analysis of DE-CRC-related genes

Great predictive capability of prognostic risk model

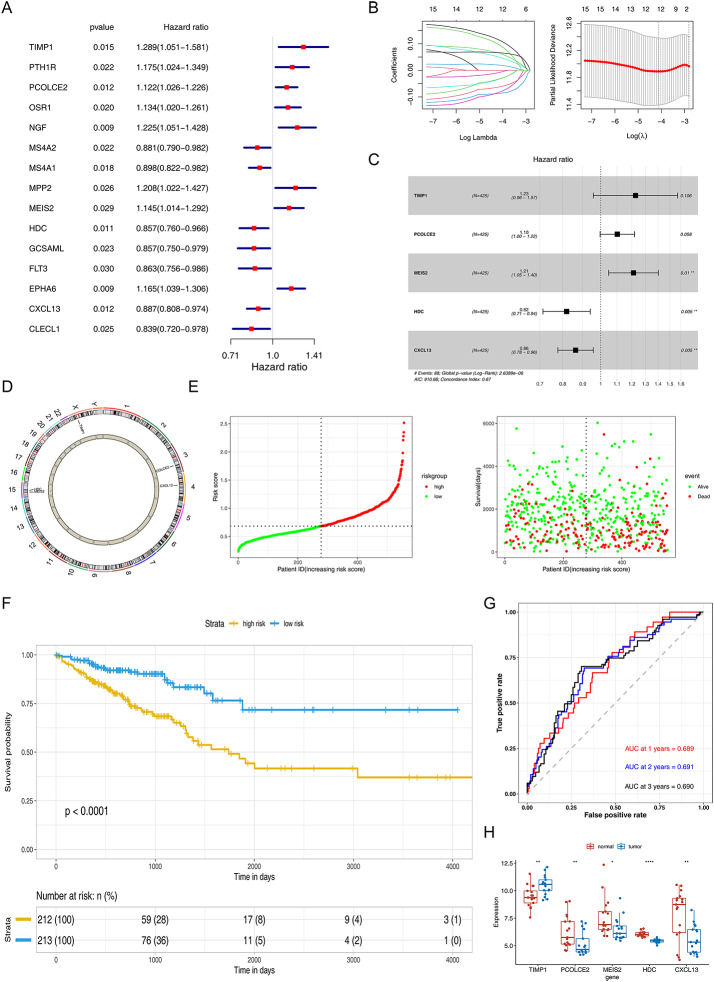

Univariate Cox analysis was conducted on the intersection genes to screen for candidate prognostic genes with high prognostic ability (p < 0.03), and 15 genes were found to be significantly associated with OS (Fig. 3A). Next, the results were then analyzed by LASSO and multifactorial Cox analysis, which showed that TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, and CXCL13 were the characteristic genes of CRC (Fig. 3B − 3 C), and their positioning on the chromosome was shown in Fig. 3D. Then, the model was developed as follows: Risk score = TIMP1 × 0.203931952 + PCOLCE2 × 0.09722934 + MEIS2 × 0.192140876 – HDC × 0.20005372 - CXCL13 × 0.14748485. According to median risk = 0.971322, CRC patients were divided into high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Construction and evaluation of the prognostic risk model. A and C respectively represent the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses conducted for prognostic gene screening; B. LASSO regression analysis; D. Chromosomal localization of prognostic genes; E. Scatter plots illustrating high and low risk scores, as well as the association between risk scores and prognosis; F. KM analysis demonstrated a significant difference in prognosis between the low-risk and high-risk groups (p < 0.0001); G. The ROC curve analysis. AUC values at 1, 2, and 3 years were approximately 0.7 indicating better efficacy of the risk model. H. Differential expression of prognostic genes in the GSE32323 dataset

Subsequently, to further assess the validity of the risk signature, the prognostic model was evaluated through the ROC curve and the difference analysis of KM curves between high-risk and low-risk groups. The KM analysis showed that patients with high-risk scores had significantly lower OS than those with low-risk scores (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3F). The ROC curve for OS was calculated, and the area under the curve (AUC) values at 1, 3, and 5 years were approximately 0.7 indicating better efficacy of the risk model (Fig. 3G). This prognostic risk model still had strong predictive power in both the internal test set and the external GSE39582 dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In addition, the decision curve analysis (DCA) and principal component analysis (PCA) results of the prognostic risk model in the training set, internal test set, and external validation set demonstrated the strong predictive power of the model (Supplementary Fig. 2). These five characteristic genes were also differentially expressed in GSE32323, further demonstrating the superiority of the model (Fig. 3H).

Functional assessment of the nomogram model

To assess the performance of the risk model as an independent prognostic factor, clinical variables and risk scores from 606 CRC tissue samples were combined to perform univariate and multivariate Cox analyses (Table 2; Fig. 4A). Age, MMR protein expression, lymphovascular infiltration, pathologic M stage, pathologic N stage, and tumor stage, and risk score were identified as prognostic factors for CRC patients.

Table 2.

The univariate analysis of independent prognostic models

| Clinical factor | HR | HR.95 L | HR.95 H | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.000275*** |

| Loss Expression of MMR Proteins | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.73 | 0.012971* |

| Lymphatic invasion | 1.89 | 1.29 | 2.77 | 0.001057** |

| Risk score | 1.52 | 1.33 | 1.74 | 8.35E-10*** |

| pathologic M | 4.32 | 2.9 | 6.44 | 5.96E-13*** |

| pathologic N(reference: N0) | ||||

| N1 | 1.900343802 | 1.206960394 | 2.992067168 | 0.005568** |

| N2 | 3.961218249 | 2.611668465 | 6.008132437 | 9.37E-11*** |

| pathologic T(reference: T0) | ||||

| T4 | 6.15 | 1.46 | 26 | 0.013490* |

|

Tumor stage (reference: I) | ||||

| III | 3.35 | 1.41 | 7.94 | 0.006098** |

| IV | 9.13 | 3.87 | 21.55 | 4.46E-07*** |

HR Hazards ratio

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Fig. 4.

Functional assessment of the prognostic risk model. A Multivariate Cox regression analyses to detect independent prognostic factors; B Prognostic model nomogram were developed; C Calibration curve for evaluating the predictive performance of nomogram model; D The ROC curves for evaluating the predictive performance of nomogram model, the AUC values for 1, 2 and 3 years were all greater than 0.7

On the basis of independent prognostic factors, a nomogram model was developed to estimate the survival probability of CRC patients (Fig. 4B), which was found that the survival rate decreases as overall score increases. The correction curve value of this nomogram model approached 1, indicating that its prediction was true and reliable (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the ROC curve values of nomogram model for 1, 2 and 3 years were all greater than 0.7, which indicated that the model had excellent prediction (Fig. 4D).

Multiple analyses of characteristic genes indicated their importance in CRC

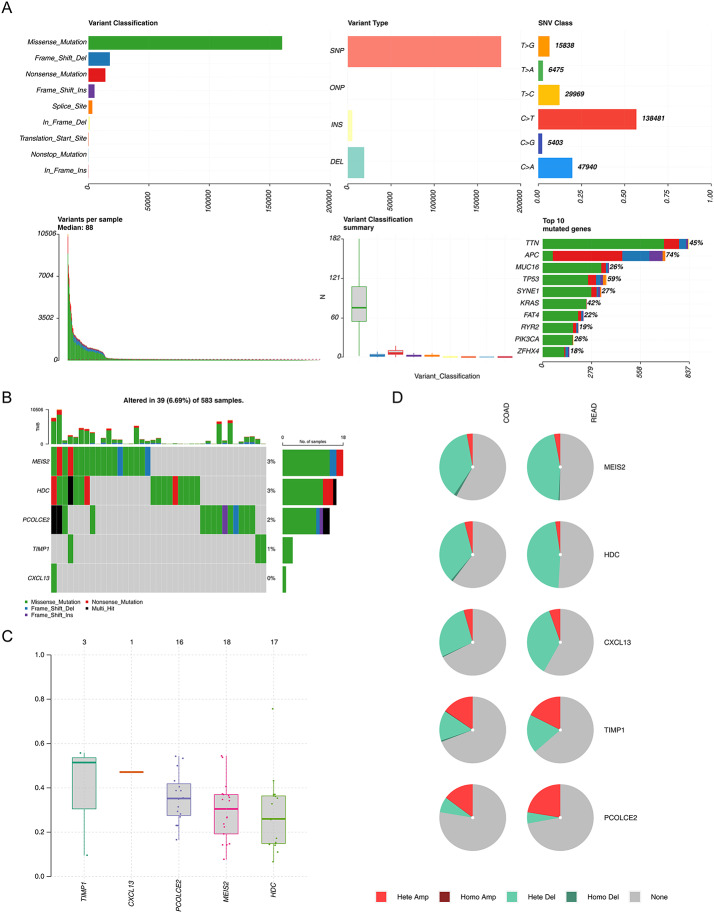

Mutation analysis of all genes in the TCGA-CRC dataset revealed the highest proportion of missense mutations and the highest proportion of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation patterns were C to T (Fig. 5A). Although the top 10 mutated genes did not have the characteristic genes, the characteristic genes were all dominated by missense mutations (Fig. 5B). MEIS2 exhibited the highest mutation frequency, followed by HDC. The variant allele frequency was highest for TIMP1 and lowest for HDC (Fig. 5C). Heterozygous amplification (Hete Amp) and heterozygous deletion (Hete Del) are the major forms of copy number variation of the characteristic genes (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Multiple analyses of characteristic genes in CRC. A Mutation analysis of all genes in the TCGA-CRC dataset; B Mutation status of five prognostic genes; C. Variant allele frequency of prognostic genes; D. Analysis of copy number variation (CNV) status of prognostic genes by GSCA database

Functional analysis of the prognostic gene TIMP1 and its expression at the histological level

TIMP1 is an important prognostic marker for the progression and metastasis in different cancer [30–32]and has been shown to influence several tumorigenic biological processes [33–35]. Moreover, TIMP1 plays a role in anti-tumor drugs resistance [31, 33]. To elucidate the biological functions of TIMP1 in CRC, utilizing GSEA (version 1.36.3), we identified pathways and molecular functions associated with TIMP1 that are implicated in CRC progression. Notably, TIMP1 was found to be enriched in pathways such as type I interferon receptor binding, oxidative phosphorylation, and the Notch signaling pathway, all of which are known to play a role in cancer development and metastasis (Fig. 6A and B). Subsequently, we searched the UALCAN database (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) and found that the expression of TIMP1 was significantly higher in CRC than in normal people, which was consistent with the previous study [30, 31, 36]and that it tended to increase with increasing pathological grade, suggesting that overexpression of TIMP1 was associated with worse pathological stage and poor prognosis (Fig. 6C and D).

Fig. 6.

Functional analyses and histological expression of TIMP1 in CRC. A Go analysis items of TIMP1 in CRC; B KEGG pathways of TIMP1 in CRC; C Data from the UALCAN database indicating that TIMP1 is more highly expressed in CRC tissues than in normal tissues. *** P < 0.001. D The expression of TIMP1 increases with increasing pathological grade according to the UALCAN database. E, F. The HPA analysis; G. KM survival curves of patients with high versus low expression of TIMP1 in the TCGA database (P = 0.0058)

At the histological level, immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that TIMP1 expression was markedly higher in CRC tumor tissues compared to normal tissues. (Figure 6E and F), which was consistent with the results of the previous expression analysis in GSE32323 (Fig. 3H). Not only that, CRC patients with high TIMP1 expression exhibited shorter survival times and poorer prognoses, as analyzed by Kaplan-Meier analysis (Fig. 6G).

TIMP1 knockdown suppresses CRC cells proliferation, metastasis and promoted apoptosis

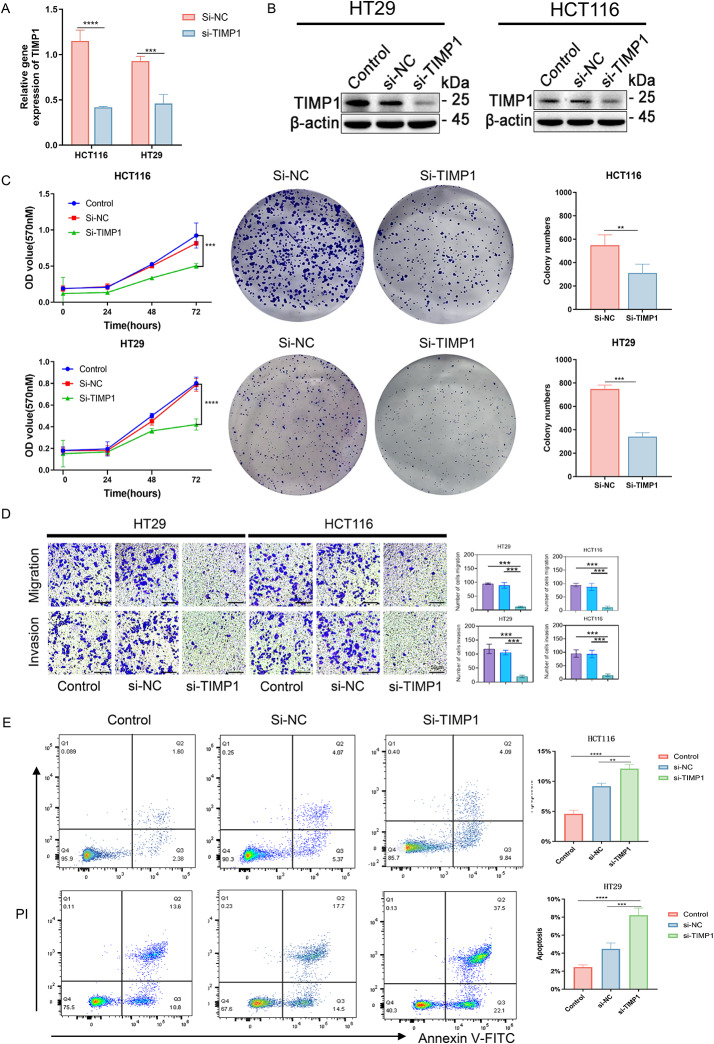

Our bioinformatics analysis has highlighted the significant role of TIMP1 in the prognosis of colorectal cancer, where its overexpression is associated with poor clinical outcomes. To further substantiate the impact of TIMP1 on CRC cell, experimental validation was conducted. siRNA technology was utilized to knock down TIMP1 expression in the HCT116 and HT29 cell lines. RT-qPCR and western blot analyses post-transfection confirmed a significant reduction in both mRNA and protein levels of TIMP1 in these cells (Fig. 7A and B). Subsequently, MTT assay revealed that si-TIMP1 transfection significantly inhibited cell viability (Fig. 7C). Moreover, colony formation assays further demonstrated that TIMP1 knockdown impaired the ability of these cells to form colonies compared to the negative control (Si-NC) cells (Fig. 7C). In terms of cell migration and invasion, silencing TIMP1 reduced the capacities of HCT116 and HT29 cells, as evidenced by a lower number of cells in si-TIMP1 treated groups compared to the Si-NC group (Fig. 7D). The cell apoptosis was also studied using Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The apoptosis cells were measured by staining with Annexin V-FITC along with Propidium Iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry. A higher number of apoptotic cells were observed in the Si-TIMP1 group compared to the Si-NC cells (Fig. 7E), indicating that TIMP1 silencing enhances apoptosis in CRC cells. These results imply that TIMP1 is involved in CRC carcinogenesis and may serve as a prognostic biomarker and a potential therapeutic target.

Fig. 7.

The clinical significance of TIMP1 in CRC and in vitro study. A, B. Evaluation of silencing efficiency of siRNA in CRC cell lines; C. MTT and Cell colony forming assays are used to assess the influence of blocking TIMP1 expressions on proliferative abilities of HCT116 and HT29 cells; D. The transwell assays revealed that silencing of TIMP1 inhibited the migration and invasion of CRC cells; E. The apoptosis observed after knocking down TIMP1 in CRC cells. All experiments and analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reliability. Numerical data are displayed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). siRNA Small interfering RNA; Control: Blank control group; NC: Negative control group; ** means p value < 0.01; *** means p value < 0.001

Discussion

In recent years, the field of cancer treatment has experienced significant advancements. However, the prognosis of advanced CRC remains unfavourable. It is crucial to identify and validate novel molecular markers and models for CRC diagnosis and prognosis. In this study, we conducted an integrated analysis of RNA-seq data and clinical information obtained from the GEO and TCGA databases. A total of 5408 differentially expressed genes were identified between CRC tissues and normal tissues in the TCGA-CRC dataset, comprising 2779 upregulated DEGs and 2629 downregulated DEGs. Based on WGCNA, we screened the modules related to CRC. The MEbrown module was the most associated with CRC and contained 1639 CRC-associated genes, of which 926 CRC-associated genes were differentially expressed. Through LASSO regression and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, we identified five characteristic genes associated with CRC: TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, and CXCL13. Subsequently, we developed a prognostic risk model with substantial predictive capability. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that patients with high-risk scores had significantly lower OS than those with low-risk scores. The time-dependent ROC curve analysis yielded an area under the curve of 0.7, indicating relatively high specificity and sensitivity of the prognostic signature for CRC. This prognostic risk model demonstrated robust predictive power in both the internal TCGA dataset and the external GSE39582 dataset. Additionally, decision DCA and PCA results confirmed the strong predictive performance of the model across the training set, internal dataset, and external validation set. Notably, these five characteristic genes were also differentially expressed in the GSE32323 dataset, further validating the superiority of the model.

In the LASSO analysis, we employed 10-fold cross-validation. Specifically, the dataset was partitioned into 10 subsets, with 9 subsets iteratively used for training and the remaining 1 subset for testing, thereby evaluating model performance across multiple iterations. This approach effectively mitigates bias introduced by data partitioning and ensures the model’s generalizability. Additionally, we assessed model performance by calculating the partial likelihood deviance for each fold and selected the regularization parameter lambda.min that minimized cross-validation error. This process reflects the model’s performance across diverse data subsets, preventing bias arising from specific data distributions or overfitting [37]. These steps demonstrate the stability of our model through repeated validations, enhancing its reliability and robustness in practical applications.

The functional enrichment analysis demonstrated that the DEGs were involved in some biological processes, such as cell adhesion, cell communication. In accordance with previous research, these biological processes play crucial role in CRC tumorigenesis and development [38]. KEGG analysis on DE-CRC-related genes revealed that they were also enriched in cGMP-PKG signaling pathway, circadian rhythm, cAMP signaling pathway, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway related to CRC. According to Zhan Ma et al., PHLDA2 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and autophagy in CRC via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [3]. Si-Yang Li et al. has demonstrated that Diosgenin suppresses CRC cells through cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway [39]. Our research revealed that these DEGs are implicated in the tumorigenesis and development of CRC, which was consistent with the previous research.

Through univariate, multivariate Cox regression analysis, and LASSO analysis, we identified five key prognostic genes: TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, and CXCL13. Our findings demonstrate that these genes are significantly associated with the survival outcomes of CRC patients. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have explored the roles of the five prognostic genes in CRC from various perspectives.

PCOLCE2 (Procollagen C-Endopeptidase Enhancer 2) encodes a collagen-binding protein, which is involved in the regulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) by enhancing the activity of procollagen C-terminal peptidase [40]. The abnormal remodeling of ECM is closely related to the occurrence, invasion and metastasis of tumor. Previous studies have demonstrated that TGF-β signaling and Hedgehog signaling are significantly activated in groups with high PCOLCE2 expression in CRC. These pathways play critical roles in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the maintenance of cancer stem cells [41, 42]. Furthermore, lncRNA SNHG14 acts as a competing endogenous RNA by forming the SNHG14/miR-200a-3p/PCOLCE2 oncogenic axis. This axis further promotes the proliferation, migration, and immune evasion of CRC cells. PCOLCE2 can promote the enzymatic cleavage of type I procollagen to produce mature structured fibrils [43]. Our findings are consistent with previous research, Chen et al. developed a prognostic gene signature made up by 9 genes, including PCOLCE2 and T1MP1, and they accurately predicted the overall survival in CRC patients [40]. Although the specific mechanism of PCOLCE2 in CRC is less known, according to recent research, PCOLCE2 has been identified as the main gene driving the development of endometrial cancer, and our findings are supported by this research [44]. Notably, the expression level of PCOLCE2 is positively correlated with multiple immune checkpoint genes (e.g., PDCD1, CTLA4, CD274) and significantly associated with the infiltration of CD8 + T cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. These findings suggest that PCOLCE2 may contribute to tumor progression by modulating the immunosuppressive microenvironment [45, 46].

MEIS2 (Homo sapiens Meis homeobox 2) belongs to the MEIS protein family and plays crucial roles in regulating neural crest and limb development [47]., and it has been implicated in the development of human cancer [48]. Previous studies have demonstrated that high expression levels of MEIS2 are significantly correlated with reduced overall survival times in patients with CRC. Knockdown of MEIS2 significantly suppresses CRC cell migration, invasion, and EMT. Moreover, MEIS2 has been identified as a factor associated with shorter overall survival times in CRC patients [49]. MEIS2 promotes tumor progression in CRC by regulating immune-intrinsic cell death and may serve as a potential predictive biomarker for immunotherapy [50]. Furthermore, MEIS2 facilitates tumor progression by maintaining the characteristics of cancer stem cells in CRC [51]. Recent research showed that in prostate cancer and ovarian cancer, the degree of MEIS2 protein expression was related to the development of clinically metastatic illness and the absence of biochemical recurrence [52, 53]. Ziang Wan et al. has firstly demonstrated that the MEIS2 promotes cell migration and invasion in CRC, and acts as a promoter of metastasis in CRC [49]. Our study further validated MEIS2 as a potential biomarker for CRC. Continued investigation of this gene may offer valuable insights and references for the development of therapeutic strategies for this disease.

HDC (Histidine decarboxylase) is an inhibitor of NOX2-derived ROS [54]and exerts anti-cancer efficacy in experimental tumor models. Hanna et al. propose that anti-tumor properties of HDC may comprise the targeting of MDSCs [55]. In addition, Chen et al. demonstrated that HDC + granulocytic myeloid cells influence CD8 + T cells both directly and indirectly through modulating Tregs, and which hence appear to play crucial roles in suppressing tumoricidal immunity in murine colon cancer [56]. In colon cancer patients, the high expression of HDC and H2R genes is significantly correlated with prolonged overall survival. HDC deficiency results in histamine insufficiency, which contributes to chronic inflammation and tumor progression. However, exogenous supplementation with histamine-producing probiotics can reverse this process [57, 58]. Within the intestinal microbiota, microbial histamine production relies on HDC activity, which is modulated by the host’s intestinal environment, including pH levels and ionic concentrations. Consequently, enhancing the activity of microbial HDC may effectively suppress the development of intestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis by augmenting histamine-mediated anti-inflammatory effects [59]. The deficiency of HDC results in a marked reduction in histamine levels, which significantly impacts the immune response. In the OVA-induced allergy model, the reduction in histamine levels due to HDC deficiency promotes IL-17 production, thereby contributing to the progression of tumor growth [60]. The low expression of HDC is significantly associated with a poorer prognosis in CRC patients, which is consistent with our findings. The underlying mechanism may involve HDC’s role in modulating the histidine metabolic pathway, as abnormal histidine metabolism has been demonstrated to play a critical role in tumor initiation and progression. Additionally, HDC expression is regulated by the transcription factor ATF3, which modulates tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and malignant transformation by altering HDC expression levels [61]. This study for the first time identified HDC as a biomarker related to CRC, providing new therapeutic targets and research directions for this field.

CXCL13, a homeostatic chemokine, is secreted by the stromal cells in the B-cell area of the secondary lymphoid tissues. CXCL13 plays a significant role in tumor progression [62]. The previous study demonstrates that CXCL13 can promote prostate cancer cell proliferation through JNK signaling and invasion through activation of ERK [63]. The same findings as our study, Qi XW et al., indicate that CXCR5 and CXCL13 appear to be independent predictors of survival markers for patients with CRC [64]. Senlin Zhao et al. demonstrated that polarized M2 macrophages could induce premetastatic niche formation and promote CRLM by secreting CXCL13, which activated a CXCL13/CXCR5/NFκB/p65/miR-934 positive feedback loop in CRC cells [65]. Our research is consistent with previous studies in identifying CXCL13 as a potential biomarker. Future studies can further explore the function of CXCL13 and its role in the progression of CRC, providing new ideas for the treatment of this disease.

Among these genes, TIMP1 attract our attention. Tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), belongs to the Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases family which included four identified members [32, 66]. TIMP1 encodes a 931 base-pair mRNA and a 207 amino acid protein. This protein may inhibit the proteolytic action of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are thought to be crucial for the tumor invasion and development of metastatic disease [67, 68]. T1MP1 has been showed that its expression is upregulated in colon cancer [69, 70]and it also plays an important role in the regulation of cell proliferation and anti-apoptotic function [71, 72]. A previous study indicated that TIMP1 is a key role in promoting progression and metastasis of human colon cancer, and function as a potential prognostic indicator for colon cancer [30]. Through in vitro experiments, we verified the inhibitory effect of blocking TIMP1 expression on growth and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells. Moreover, we investigated the apoptotic effect of TIMP1 on CRC cells, TIMP1 knocked down can promote apoptosis of CRC cells. In summary, we have initially explored the biological function of TIMP1 in CRC, further verified its potential as a therapeutic target, and provided new insights for the treatment of CRC.

However, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, in vivo experiments are necessary to further validate the biological functions of TIMP1 in CRC. Second, the current study did not explore whether a TIMP1 inducer could counteract the promoting effects of TIMP1 on cancer cell growth, metastasis, and apoptosis. Third, the prognostic model developed in this study requires external validation through prospective clinical trials to confirm its clinical utility and generalizability. In future studies, we will further investigate these issues to deepen our understanding and address the remaining challenges.

Conclusion

In this research, we developed and validated a novel prognostic risk model for CRC, utilizing both the GSE32323 dataset and an internal dataset, thereby confirming its predictive accuracy. Nevertheless, the current validation scope of this prognostic model remains relatively restricted. In future research and practical applications, it will be essential to further validate this model across additional independent cohorts and diverse clinical settings to ensure its robustness and generalizability. The model implicates TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, and CXCL13 as pivotal genes in CRC. TIMP1, in particular, was subjected to in vitro study, revealing its significant role in CRC biology. Despite these findings, our study acknowledges the need for in vivo studies and a deeper exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying the identified genes in CRC pathology. It is imperative that future investigations bridge these gaps and further probe the therapeutic potential of TIMP1. In conclusion, our findings indicate that TIMP1 promotes CRC cell proliferation. Conversely, the inhibition of TIMP1 suppresses proliferation and metastasis while enhancing apoptosis in CRC cell lines. This study provides valuable insights into the development of targeted therapies for CRC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We also would like to acknowledge the contributions by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22004056), and the Stable Support Project of Shenzhen (Project No. 20231120105309001). We also thank the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shenzhen University for the assistance with the Flow Cytometry technical support.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BP

Biological process

- CC

Cellular component

- CNV

Copy number variation

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DCA

Decision curve analysis

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- GSCA

Gene set cancer analysis

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- GO

Gene ontology

- HDC

Histidine decarboxylase

- Hete Amp

Heterozygous amplification

- Hete Del

Heterozygous deletion

- HPA

Human protein atlas

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- KD

Knock down

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- K-M

Kaplan-Meier

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- MEIS2

Homo sapiens meis homeobox 2

- MF

Molecular function

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MMR protein

Mismatch repair protein

- MSI-H

Microsatellite instability-high

- MSS

Microsatellite stable

- MTT

Methyl tetrazolium

- OS

Overall survival

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PPI

Protein-protein interactions

- PFS

Progression free survival

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TCGA

The cancer genome atlas

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Author contributions

MS, HF conceived and designed the study. HF, WGZ, ZYL, FJY performed the literature search and manuscript writing; HF, SA, CL wrote the original draft; SA, MJ, CTN, SC, KKV and MAA provided input as content experts; MS, HF, MAA and SC reviewed and proofread the writing. All authors have contributed, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded and supported by grant provided by Centre of Excellence for Research, Value Innovation and Entrepreneurship (CERVIE), UCSI University under the project code REIG-FPS-2023/040.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GEO and TCGA repository. The GSE39582 and GSE32323 were obtained from GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the TCGA-CRC were downloaded from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable. This study exclusively utilized commercially available colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT116 and HT29) and publicly accessible bioinformatics data from GEO, TCGA, and HPA databases. The use of cell lines and pre-existing anonymized public data does not require ethical approval under institutional or national guidelines. This study did not generate or involve the use of any personally identifiable information (e.g., patient images, genomic sequences linked to individuals). All public database analyses complied with their respective data access policies and publication guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohammed Abdullah Alshawsh, Email: alshaweshmam@um.edu.my.

Karthikkumar Venkatachalam, Email: karthikjega@gmail.com.

Malarvili Selvaraja, Email: malarvili@ucsiuniversity.edu.my.

References

- 1.Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467–80. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreuders EH, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: a global overview of existing programmes. Gut. 2015;64:1637–49. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-309086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Z, Lou S, Jiang Z. PHLDA2 regulates EMT and autophagy in colorectal cancer via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Aging. 2020;12:7985–8000. 10.18632/aging.103117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12–49. 10.3322/caac.21820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer IA. f. R. o. Colorectal cancer, https://www.iarc.who.int/cancer-type/colorectal-cancer/ (2022).

- 6.Xi Y, Xu P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol. 2021;14:101174. 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grothey A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–12. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61900-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekaii-Saab TS, et al. Regorafenib dose-optimisation in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (ReDOS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1070–82. 10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30272-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludford K, et al. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab in localized microsatellite instability high/deficient mismatch repair solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2181–90. 10.1200/jco.22.01351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark BC, Arnold WD et al. Strategies to prevent serious fall injuries: a commentary on bhasin. a randomized trial of a multifactorial strategy to prevent serious fall injuries. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):129–140. Adv Geriatr Med Res. 2021;10.20900/agmr20210002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Le DT, et al. Pembrolizumab for previously treated, microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient advanced colorectal cancer: final analysis of KEYNOTE-164. Eur J Cancer. 2023;186:185–95. 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaeger R, et al. Efficacy and safety of adagrasib plus cetuximab in patients with KRASG12C-Mutated metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:982–93. 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-24-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foroutan F, et al. Computer aided detection and diagnosis of polyps in adult patients undergoing colonoscopy: a living clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2025;388:e082656. 10.1136/bmj-2024-082656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machida N, et al. A phase 2 study of adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin and oxaliplatin after lung metastasectomy for colorectal cancer (WJOG5810G). Cancer. 2025;131:e35807. 10.1002/cncr.35807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong YL, et al. Sequential chemotherapy/radiotherapy was comparable with concurrent chemoradiotherapy for stage I/II NK/T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:256–63. 10.1093/annonc/mdx684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, et al. Decreased MALL expression negatively impacts colorectal cancer patient survival. Oncotarget. 2016;7:22911–27. 10.18632/oncotarget.8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:559. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen H, Boutros PC. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:35. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D277–80. 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan I, et al. Alteration of gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): cause or consequence?? IBD treatment targeting the gut microbiome. Pathogens. 2019;10.3390/pathogens8030126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colaprico A, et al. TCGAbiolinks: an r/bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e71. 10.1093/nar/gkv1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Ma S. Time-dependent ROC analysis under diverse censoring patterns. Stat Med. 2011;30:1266–77. 10.1002/sim.4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5. 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanehisa M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019;28:1947–51. 10.1002/pro.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Ishiguro-Watanabe M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D587–92. 10.1093/nar/gkac963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song G, et al. TIMP1 is a prognostic marker for the progression and metastasis of colon cancer through FAK-PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:148. 10.1186/s13046-016-0427-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian Z, et al. Arsenic trioxide sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine through downregulation of the TIMP1/PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis. Trans Res. 2023;255:66–76. 10.1016/j.trsl.2022.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YY, Li L, Zhao ZS, Wang HJ. Clinical utility of measuring expression levels of KAP1, TIMP1 and STC2 in peripheral blood of patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:81. 10.1186/1477-7819-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toricelli M, Melo FH, Peres GB, Silva DC, Jasiulionis MG. Timp1 interacts with beta-1 integrin and CD63 along melanoma genesis and confers Anoikis resistance by activating PI3-K signaling pathway independently of Akt phosphorylation. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:22. 10.1186/1476-4598-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balah A, Ezzat O, Akool ES. Vitamin E inhibits cyclosporin A-induced CTGF and TIMP-1 expression by repressing ROS-mediated activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in rat liver. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;65:493–502. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells via activating IL-17a/JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:877. 10.21037/atm-20-4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, Ni QY, Yu SY. Integration of single-cell transcriptomics and epigenetic analysis reveals enhancer-controlled TIMP1 as a regulator of ferroptosis in colorectal cancer. Genes Genomics. 2024;46:121–33. 10.1007/s13258-023-01474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, et al. Interpretable machine learning method to predict the risk of pre-diabetes using a national-wide cross-sectional data: evidence from CHNS. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:1145. 10.1186/s12889-025-22419-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2449–60. 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li SY, et al. Diosgenin exerts anti-tumor effects through inactivation of cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;908:174370. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L, et al. Identification of biomarkers associated with diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer patients based on integrated bioinformatics analysis. Gene. 2019;692:119–25. 10.1016/j.gene.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao H, Li C, Tan X. An age stratified analysis of the biomarkers in patients with colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:22464. 10.1038/s41598-021-01850-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, et al. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related mRNA signature associated with the prognosis, immune infiltration and therapeutic response of colon adenocarcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2023;29:1611016. 10.3389/pore.2023.1611016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bourhis JM, et al. Procollagen C-proteinase enhancer grasps the stalk of the C-propeptide trimer to boost collagen precursor maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6394–9. 10.1073/pnas.1300480110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, Wang Y. Identification of hub genes and key pathways associated with the progression of gynecological cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:6516–24. 10.3892/ol.2019.11004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li N et al. Identification of the Immune-related LncRNA SNHG14/ miR-200a-3p/ PCOLCE2 axis in colorectal cancer. Altern Ther Health Med (2024). [PubMed]

- 46.Liu Q, Liao L. Identification of macrophage-related molecular subgroups and risk signature in colorectal cancer based on a bioinformatics analysis. Autoimmunity. 2024;57:2321908. 10.1080/08916934.2024.2321908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geerts D, Schilderink N, Jorritsma G, Versteeg R. The role of the MEIS homeobox genes in neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2003;197:87–92. 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhanvadia RR, et al. MEIS1 and MEIS2 expression and prostate cancer progression: a role for HOXB13 binding partners in metastatic disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:3668–80. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan Z, et al. MEIS2 promotes cell migration and invasion in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2019;42:213–23. 10.3892/or.2019.7161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu J, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic insights into colorectal carcinoma through Immunogenic cell death gene profiling. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17629. 10.7717/peerj.17629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, Liu YH, Hu YY, Chen L, Li JM. Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 acts as a negative regulator of stemness in colorectal cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8528–39. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeong JH, Park SJ, Dickinson SI, Luo JL. A constitutive intrinsic inflammatory signaling circuit composed of miR-196b, Meis2, PPP3CC, and p65 drives prostate cancer castration resistance. Mol Cell. 2017;65:154–67. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crijns AP, et al. MEIS and PBX homeobox proteins in ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2495–505. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mellqvist UH, et al. Natural killer cell dysfunction and apoptosis induced by chronic myelogenous leukemia cells: role of reactive oxygen species and regulation by Histamine. Blood. 2000;96:1961–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grauers Wiktorin H, et al. Histamine targets myeloid-derived suppressor cells and improves the anti-tumor efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:163–74. 10.1007/s00262-018-2253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen X, et al. Histidine decarboxylase (HDC)-expressing granulocytic myeloid cells induce and recruit Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in murine colon cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1290034. 10.1080/2162402x.2017.1290034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao C, et al. Gut microbe-mediated suppression of inflammation-associated colon carcinogenesis by luminal histamine production. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:2323–36. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang P, Lai S, Wu S, Zhao XM, Chen WH. Host DNA contents in fecal metagenomics as a biomarker for intestinal diseases and effective treatment. BMC Genomics. 2020;21:348. 10.1186/s12864-020-6749-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hall AE, Engevik MA, Oezguen N, Haag A, Versalovic J. ClC transporter activity modulates histidine catabolism in Lactobacillus reuteri by altering intracellular pH and membrane potential. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18:212. 10.1186/s12934-019-1264-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen X, et al. IL-17 producing mast cells promote the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in a mouse allergy model of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32966–79. 10.18632/oncotarget.5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan F, et al. Overexpression of the transcription factor ATF3 with a regulatory molecular signature associates with the pathogenic development of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:47020–36. 10.18632/oncotarget.16638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Müller G, Höpken UE, Lipp M. The impact of CCR7 and CXCR5 on lymphoid organ development and systemic immunity. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:117–35. 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sobin LH, Fleming ID. TNM classification of malignant tumors, fifth edition (1997). Union internationale contre le cancer and the American joint committee on cancer. Cancer 1997;80:1803–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Qi XW, et al. Expression features of CXCR5 and its ligand, CXCL13 associated with poor prognosis of advanced colorectal cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:1916–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao S, et al. Tumor-derived exosomal miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:156. 10.1186/s13045-020-00991-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Würtz SO, Schrohl AS, Mouridsen H. Brünner, N. TIMP-1 as a tumor marker in breast cancer–an update. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:580–90. 10.1080/02841860802022976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Batra J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 (MMP-10) interaction with tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases TIMP-1 and TIMP-2: binding studies and crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15935–46. 10.1074/jbc.M112.341156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bao W, et al. HER2-mediated upregulation of MMP-1 is involved in gastric cancer cell invasion. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;499:49–55. 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim YS, et al. Overexpression and β-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminylation-initiated aberrant glycosylation of TIMP-1: a double whammy strategy in colon cancer progression. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:32467–78. 10.1074/jbc.M112.370064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Okuno K, et al. Gene expression analysis in colorectal cancer using practical DNA array filter. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:295–9. 10.1007/bf02234309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bourboulia D, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): positive and negative regulators in tumor cell adhesion. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20:161–8. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schelter F, et al. Tumor cell-derived Timp-1 is necessary for maintaining metastasis-promoting Met-signaling via Inhibition of Adam-10. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2011;28:793–802. 10.1007/s10585-011-9410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GEO and TCGA repository. The GSE39582 and GSE32323 were obtained from GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the TCGA-CRC were downloaded from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).