Abstract

Summary

Treatment with antiosteoporotics is recommended after a hip fracture to reduce the risk of a new fracture or death. In our study, we found a slight increase in treatment rates over time, but an important treatment gap in the contemporary secondary prevention of hip fracture is still present.

Introduction

The pharmacological management of patients after hip fracture is likely to have changed due to the availability of denosumab during the last decade, but the extent of its use and potential improvement in treatment rates in routine clinical practice is largely unknown.

Methods

We constructed a population-based retrospective cohort of all patients aged 65 years + , discharged alive following hip fracture hospitalization (Jan 2008 to Dec 2021) in several regions of Spain, accounting for one third of the country’s population. The proportion of patients prescribed any antiosteoporotic (AO) medication and specific classes in the first 90 days after discharge was evaluated. Temporal trends of treatment prescription per month were plotted. All analyses were performed also by age, sex, and region.

Results

In a cohort of over 120,000 patients, we found an important treatment gap in the secondary prevention of hip fracture (78% of patients untreated). Bisphosphonates and denosumab accounted for 60% and 20% of the AO prescriptions, respectively. Treatment gaps were most pronounced among patients aged 85 and over, and males: 26% of patients aged ≤ 84 were treated, in contrast to 18% of those aged 85 + . The proportion of females treated nearly doubled that of males (24% vs 14%). Differences by region were observed. Regarding time trends, despite finding an increase over time, prescription rates remained highly suboptimal. By drug class, treatment with bisphosphonates dropped, whereas denosumab treatment rose along the study period. Concerning management by sex, the Mediterranean regions showed a persistent gap over time, whereas in the Northern regions, the gap was gradually reduced. Treatment patterns by age groups were consistent over time.

Conclusions

Our study offers evidence to identify current gaps of care in secondary prevention of hip fracture and implement adequate strategies to reduce recurrent fractures in this frail population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00198-025-07564-4.

Keywords: Bisphosphonates, Denosumab, Drug use, Health service research, Hip fracture, Osteoporosis

Introduction

The USA, Europe, India, and Japan concentrate an estimated 125 million people suffering from osteoporosis [1]. Osteoporotic fractures, and among them hip fractures—the worst outcome of osteoporosis—represent the majority of the economic and health burden related to fractures in individuals in their fifties and over [2, 3]. In 2010, in the EU alone, there was an estimation of 3.5 million new fragility fractures. The economic burden was estimated at €37 billion, and a sustained increase is foreseen [1, 2], so much so that the cost is expected to rise by 25% by 2025 [1]. The health burden is striking after hip fracture, with 40% of patients not being able to walk independently, 80% not being able to perform basic tasks such as shopping independently, and 10–20% needing permanent residential care [1, 4].

Implementing prevention strategies targeted at high-risk groups is a key feature of cost-effective policies aiming to decrease the incidence and consequences of this type of fractures. However, evidence shows that in several settings, antiosteoporotic drugs are widely used in patients with a very low risk of fracture, while an important underuse has been observed in high-risk individuals, such as patients with a previous major osteoporotic fracture [5–8].

In the specific case of secondary prevention of hip fractures, recommendations in clinical practice guidelines worldwide regarding initiation of therapy with bisphosphonates or alternative medication are widely homogenous [9, 10]. Nevertheless, previous evidence shows that the majority of patients who suffer a hip fracture do not initiate antiosteoporotic therapy, and this has been seen consistently across various settings [11–17].

However, the great majority of these studies, including those set in Spain, were carried out with small populations and often not representative of the general population of reference [13, 14, 16, 17], and even if published relatively recently and with larger populations, most of them analyzed data of about a decade ago [11, 12, 18–20]. During the last decade, the availability of denosumab is likely to have changed the pharmacological management of patients after hip fracture, but there is a scarcity of information on the extent of this in routine clinical practice.

Furthermore, information available refers to dispensed medications. Lack of information on physician prescription prevents accurately knowing real-world management of these patients. Additionally, with an increasingly ageing population all around the globe [21–23], this group of patients might have a bigger percentage of older old, being even more frail nowadays than decades ago. This is relevant as aging is associated with higher risks of fracture and refracture [24]. However, several considerations come into play for the decision-making process physicians have to face when deciding whether to treat these patients or not [25].

Knowing the most recent and current real-world management of patients who survived a hip fracture at the population level, in a large population-based cohort, will offer important evidence to identify actual gaps of care in secondary prevention of hip fracture and implement adequate strategies to reduce recurrent fractures in this frail population.

We sought to evaluate the contemporary management of patients who suffered a hip fracture in a population-based cohort of over 120,000 patients using real-world data from four different regions in Spain, framed in a universal health care system, accounting for 32% of the total Spanish population over 11 years.

Methods

Study design

Population-based retrospective cohort of all patients aged 65 years and over, discharged alive following hip fracture hospitalization from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2021, in four regions of Spain [Basque Country (2017–2021), Catalonia (2010–2018), Navarre (2014–2021), Valencia Region (2008–2020)]. This national cohort, also named PREV2FO cohort to make reference to the study of the same name, is divided into four sub-cohorts, one for each region, in order to assess region-specific patterns. Patients were followed after discharge (index date) for a minimum of 365 days (end of the study December 31, 2021).

Population and setting

Patients included had a main discharge diagnosis of hip fracture (International Classification of Diseases 9th revision Clinical Modification [ICD9CM] codes: 820.xx and 733.14; International Classification of Diseases 10th revision Clinical Modification [ICD10CM]: S72.0, S72.1, S72.2). Patients with a diagnosis of high-impact trauma or fractures at multiple sites at the index date and those with a diagnosis of bone malignancy in the 365 days prior to the index date were excluded, as well as nonresidents in the region and lack of pharmaceutical coverage (due to difficulties associated with follow‐up). Patients who did not survive at least 90 days after the index fracture were also excluded.

The study was conducted in four Spanish regions (15 million inhabitants registered in 2021, accounting for one third of the Spanish population) using data of the Spanish National Health System (SNHS), an extensive network of public hospitals, primary care centers, and other facilities managed by the different regional governments, which provides universal free healthcare services (except for drug co-payment) to 97–99% of the regional population.

Covariates

Information on a wide range of relevant sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, medication use, and health services use at baseline was available and taken into account in the present study (see Table 1 for a complete list and Supplementary Table 1 for the diagnostic codes used to define comorbidities). Age, sex, and in-hospital information were measured at the index date. Comorbidities were defined as the presence of an active diagnosis during a lookback period of 12 months before the index date, while previous medication use was defined as dispensing the drug at least once during this period. Previous treatment with antiosteoporotics by drug class was defined considering the most recent dispensation prior to discharge during this lookback period of 12 months. Health services use was expressed in terms of the number of visits and hospitalizations in the lookback period of 12 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the PREV2FO national cohort and subcohorts

| Basque Country (2017–2021) | Catalonia (2010–2018) | Navarre (2014–2021) | Valencia Region (2008–2020) | PREV2FO National Cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9519 | 56,627 | 4419 | 50,905 | 121,470 |

| Percentage or mean ± standard deviation | |||||

| Socio-demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 84.8 ± 7.3 | 84.4 ± 7.1 | 85.3 ± 7.1 | 83.3 ± 7.0 | 84.0 ± 7.1 |

| 65–74 | 1053 (11.1%) | 5739 (10.1%) | 423 (9.6%) | 6853 (13.5%) | 14,068 (11.6%) |

| 75–84 | 2898 (30.4%) | 20,576 (36.3%) | 1493 (33.8%) | 21,717 (42.7%) | 46,684 (38.4%) |

| ≥ 85 | 5568 (58.5%) | 30,312 (53.5%) | 2503 (56.6%) | 22,335 (43.9%) | 60,718 (50%) |

| Female | 7435 (78.1%) | 43,138 (76.2%) | 3425 (77.5%) | 38,269 (75.2%) | 92,267 (76%) |

| Characteristics of in-hospital treatment | |||||

| Time of stay (days) | 9.87 ± 7.9 | 10.85 ± 6.73 | 9.3 ± 3.42 | 9.03 ± 6.61 | 9.96 ± 6.74 |

| Type of surgery | |||||

| Arthroplasty | 3731 (39.2%) | 19,683 (34.8%) | 1650 (37.3%) | 16,958 (33.3%) | 42,022 (34.6%) |

| Internal fixation | 5354 (56.2%) | 34,065 (60.2%) | 2346 (53.1%) | 29,930 (58.8%) | 71,695 (59%) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Osteoporosis | 1406 (14.8%) | 7565 (13.4%) | 1094 (24.8%) | 11,570 (22.7%) | 21,635 (17.8%) |

| Previous fracture | 1717 (18.0%) | 11,486 (20.3%) | 498 (11.3%) | 7222 (14.2%) | 20,892 (17.2%) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 417 (4.4%) | 2246 (4.0%) | 210 (4.8%) | 2843 (5.6%) | 5716 (4.7%) |

| Dementia | 2209 (23.2%) | 13,303 (23.5%) | 894 (20.2%) | 12,759 (25.1%) | 29,165 (24%) |

| Diabetes | 2269 (23.8%) | 13,805 (24.4%) | 1078 (24.4%) | 15,807 (31.1%) | 32,959 (27.1%) |

| Heart failure | 1086 (11.4%) | 6896 (12.2%) | 581 (13.1%) | 6654 (13.1%) | 15,217 (12.5%) |

| Hypertension | 6269 (65.9%) | 35,676 (63.0%) | 2976 (67.3%) | 36,874 (72.4%) | 81,795 (67.3%) |

| Depression | 1050 (11.0%) | 9873 (17.4%) | 1136 (25.7%) | 10,750 (21.1%) | 22,809 (18.8%) |

| Stroke | 806 (8.5%) | 5481 (9.7%) | 506 (11.5%) | 4801 (9.4%) | 11,594 (9.5%) |

| Cancer | 1954 (20.5%) | 8704 (15.4%) | 819 (18.5%) | 8985 (17.7%) | 20,462 (16.8%) |

| Previous medication use | |||||

| Antiosteoporotics (any) | 744 (7.8%) | 6209 (11.0%) | 250 (5.7%) | 6640 (13.0%) | 13,843 (11.4%) |

| Bisphosphonates | 415 (4.4%) | 4759 (8.4%) | 135 (3.1%) | 4727 (9.3%) | 10,036 (8.3%) |

| Denosumab | 242 (2.5%) | 373 (0.7%) | 88 (2.0%) | 574 (1.1%) | 1277 (1.1%) |

| Teriparatide/PTH | 78 (0.8%) | 287 (0.5%) | 17 (0.4%) | 276 (0.5%) | 658 (0.5%) |

| Other AO | 9 (0.1%) | 790 (1.4%) | 10 (0.2%) | 1063 (2.1%) | 1872 (1.5%) |

| Calcium and vitamin D | 2754 (28.9%) | 14,190 (25.1%) | 944 (21.4%) | 11,149 (21.9%) | 29,037 (23.9%) |

| Dementia | 1054 (11.1%) | 4954 (8.7%) | 495 (11.2%) | 6813 (13.4%) | 13,316 (11%) |

| Antipsychotics | 1884 (19.8%) | 8599 (15.2%) | 680 (15.4%) | 9112 (17.9%) | 20,275 (16.7%) |

| Sedatives | 1811 (19.0%) | 8998 (15.9%) | 1021 (23.1%) | 8392 (16.5%) | 20,222 (16.6%) |

| Opioids | 2690 (28.3%) | 11,307 (20.0%) | 955 (21.6%) | 15,334 (30.1%) | 30,286 (24.9%) |

| SSRIs | 1843 (19.4%) | 15,360 (27.1%) | 876 (19.8%) | 10,366 (20.4%) | 28,445 (23.4%) |

| Diuretics | 4372 (45.9%) | 28,611 (50.5%) | 1970 (44.6%) | 21,536 (42.3%) | 56,489 (46.5%) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 5228 (54.9%) | 36,831 (65.0%) | 2467 (55.8%) | 33,498 (65.8%) | 78,024 (64.2%) |

| Health care utilization | |||||

| Primary care visits | 24.4 ± 23.5 | 19.4 ± 21.4 | 24.1 ± 23.1 | 19.2 ± 22.8 | 19.9 ± 22.3 |

| ER visits | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 3.6 | 1.0 ± 2.3 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 2.8 |

| Hospitalizations | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.8 |

Osteoporosis medications

The antiosteoporotic medications studied in the present paper included alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, etidronate, parathyroid hormone (teriparatide and PTH), raloxifene, bazedoxifene, strontium ranelate, and denosumab. Zoledronic acid (only administered in the hospital setting in Spain) was not included due to a lack of in-hospital medication data. Antiosteoporotics were classified using ATC codes in four groups: oral bisphosphonates (M05BA and M05BB), denosumab (M05BX04), teriparatide/parathyroid hormone (H05AA), and others (G03XC, H05BA, M05BX03).

Therapeutic management ascertainment

Based on electronic pharmacy data, we assessed therapeutic management, examining whether a prescription was issued (filled or not) for the drugs of interest. We determined the proportion of patients who received at least one prescription for any antiosteoporotic (AO) medication during the first 90 days after the index date, for the whole cohort and by sub-cohort. Secondary outcomes were (1) the proportion of patients who were issued at least one prescription for a specific class of osteoporosis medication (i.e., oral bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone, denosumab, and others) within 90 days after the index date; (2) the proportion of patients who were issued at least one prescription for any AO or a specific class of AO medication (i.e., oral bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone, denosumab, and others) within 90 days after the index date, for the last year of available data in each of the regions; (3) therapeutic management (prescription of any antiosteoporotic medication) by age and sex was also assessed.

Data analysis

We first described the baseline characteristics of the national cohort and in each one of the four sub-cohorts, which are presented as means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables (Table 1). Afterwards, the proportion of patients who were prescribed any osteoporosis medication and specific classes in the first 90 days after discharge was evaluated for the whole cohort and in each sub-cohort (Table 2). The same analyses were performed by sex and age (Table 3).

Table 2.

Proportion of patients who suffered a hip fracture and were prescribed antiosteoporotic treatment* within 90 days after hospital discharge

| Basque Country (2017–2021) | Catalonia (2010–2018) | Navarre (2014–2021) | Valencia Region (2008–2020) | PREV2FO National Cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment for the study period | |||||

| N | 9519 | 56,627 | 4419 | 50,905 | 121,470 |

| Any antiosteoporotic medication (%) | 37.4 | 18.9 | 25.4 | 22.0 | 21.9 |

| Drug classes prescribed (%) | |||||

| Oral bisphosphonates | 18.1 | 14.2 | 7.9 | 12.8 | 13.7 |

| Denosumab | 16.6 | 2.0 | 16.3 | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| Teriparatide/PTH | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| Other | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 1.7 |

*At least one prescription within 90 days after hospital discharge

Table 3.

Number and proportion of patients who suffered a hip fracture and were prescribed antiosteoporotic treatment* within 90 days after hospital discharge, by sex and age

| Basque Country (2017–2021) | Catalonia (2010–2018) | Navarre (2014–2021) | Valencia Region (2008–2020) | PREV2FO National Cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9519 | 56,627 | 4419 | 50,905 | 121,470 |

| Treatment by sex and age: n (%) | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 714 (34.3%) | 1625 (12.0%) | 198 (19.9%) | 1587 (12.6%) | 4124 (14.1%) |

| Women | 2845 (38.3%) | 9060 (21.0%) | 924 (27.0%) | 9611 (25.1%) | 22,440 (24.3%) |

| Age group | |||||

| 65–74 | 505 (48.0%) | 1315 (22.9%) | 121 (28.6%) | 1729 (25.2%) | 3670 (26.1%) |

| 75–84 | 1337 (46.1%) | 4809 (23.4%) | 435 (29.1%) | 5540 (25.5%) | 12,121 (26.0%) |

| 85 + | 1717 (30.8%) | 4561 (15.0%) | 566 (22.6%) | 3929 (17.6%) | 10,773 (17.7%) |

*At least one prescription within 90 days after hospital discharge

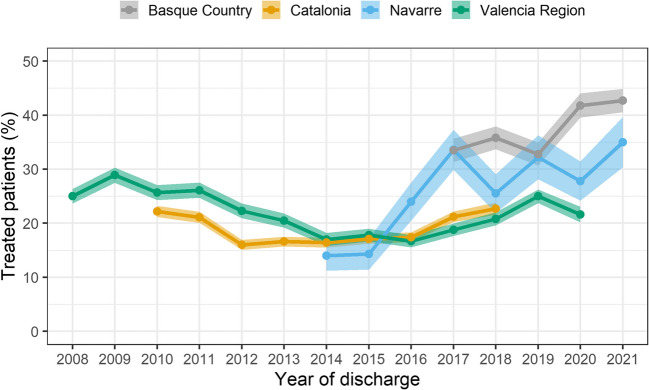

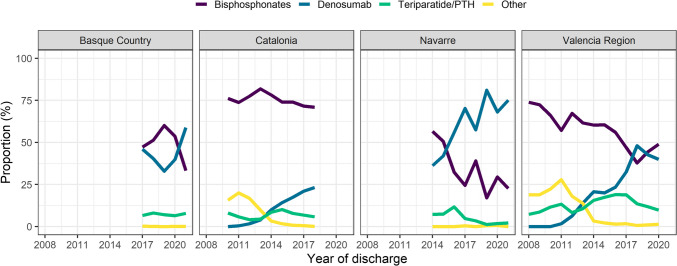

Trends of treatment prescription were analyzed by age and subcohort (Fig. 1). Temporal trends of treatment prescription per year were plotted by region (Fig. 2). The same analyses were repeated by age ranges (65–74 y, 75–84 y, and 85 y and over) and sex (male, female) for each one of the regions (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Finally, temporal trends per year according to therapeutic strategy among treated patients were also plotted. They were depicted in terms of the proportion of treated patients who were prescribed each specific class of antiosteoporotics, by year and subcohort (Fig. 3). The same analysis was repeated by age (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of treated patients by age in the secondary prevention of hip fracture in Spain

Fig. 2.

Time trends of secondary prevention of hip fracture in Spain. Proportion of patients with a prescription within 90 days after index date by region

Fig. 3.

Time trends of secondary prevention of hip fracture by drug class and for each sub-cohort among treated

All analyses were performed using the R environment [26].

Results

Patient characteristics

The study population comprised 121,470 patients discharged alive after experiencing a hip fracture between 2010 and 2021. Table 1 shows the characteristics of each sub-cohort and the whole population. The mean age for the whole cohort was 84.0 years (Standard Deviation: 7.1), with 50% being 85 years of age or over. Women accounted for 76% of the population. The mean time of stay in hospital was 10 days (SD: 6.7). Regarding health care utilization, the mean number of primary care and emergency visits in the previous year was 19.9 (SD: 22.3) and 1.4 (SD: 2.8), respectively, for the whole cohort.

Eighteen percent of patients had a baseline diagnosis of osteoporosis, and 17% had a previous fracture. The most prevalent diseases in the cohort were hypertension (67%), diabetes mellitus (27%), and dementia (24%). Regarding drug use potentially related to fracture risk in the previous year, proton pump inhibitors were the most used medication, with 64% of patients in the cohort using them, followed by diuretics (47%) and antiosteoporotics (11%). Previous treatment with antiosteoporotics was mostly bisphosphonates (8.3%), which is also true when stratifying by region despite some regional differences.

Treatment patterns for secondary prevention of hip fracture

During the study period, 22% of patients were treated with antiosteoporotics after hip fracture (Table 2). When assessing specific classes, 13.7% of the cohort were prescribed oral bisphosphonates, 4.5% denosumab, 2.0% teriparatide/PTH, and 1.7% other medications (Table 2). Treatment patterns by region showed that treatment with any antiosteoporotic was higher in the Basque Country as compared to the other regions. The most prevalent treatment in all sub-cohorts was oral bisphosphonates followed by denosumab, except in Navarre where it was the opposite.

Regarding treatment patterns in the last year available, 27% of patients were treated with antiosteoporotics after hip fracture (Supplementary Table 2). When assessing specific classes, 14% of the cohort were prescribed oral bisphosphonates, 11% denosumab, 2% teriparatide/PTH, and 0.1% other medications.

Regarding management by age, treatment rates were similar in patients aged 65–74 and 75–84 (26%); whereas this proportion was 18% in patients 85 years old and over (Table 3). This pattern of lower treatment rates for the eldest patients was very similar among regions (Table 3). When seen as a continuum, the proportion of treated patients in the whole cohort remains stable until age 80, when treatment rates start to drop steadily as age increases (Fig. 1). The proportion of treatment by drug class, seen as a continuum, and for every region is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, where differences by region are observed.

Regarding treatment by sex, overall, 24% of females and 14% of males were treated with AO during the study period (Table 3). Differences were observed by region: treatment rates for females ranged from 21% in Catalonia to 38% in the Basque Country, whereas those for males ranged from 12% in Catalonia to 34% in the Basque Country. The latter was the region with the lesser differences between male and female treatment (Table 3).

Treatment within 90 days after discharge stratified by previous treatment with AO was also assessed. Most patients who were previously treated with AO continued with the same treatment after discharge (71.4%), followed by those who discontinued (18.6%), and those who switched to another AO (10.0%). Previously untreated patients mostly remained untreated (85.8%), with a few initiating treatment as new users (14.2%). Basque Country was the region with the lowest rate of discontinuation (7.9%), while showing the highest rates for switching (19.1%) and initiation of treatment with AO (32.8%) after discharge (see Supplementary Table 3).

Regarding the relationship of previous treatment with antiosteoporotics and treatment within 90 days after discharge by drug class (Supplementary Fig. 4), denosumab showed the highest proportion of treatment continuation (88.9%), followed by bisphosphonates (72.6%), teriparatide (68.5%), and other AO (53.8%). Overall, untreated patients initiated mostly with bisphosphonates (8.4%) and denosumab (3.6%), with some differences between regions (see Supplementary Table 4).

Time trends in secondary prevention of hip fracture

Figure 2 shows time trends by sub-cohort. Overall, Basque Country and Navarre showed an increasing trend over time in antiosteoporotic treatment after hip fracture, whereas Catalonia and the Valencia Region showed a U-shaped trend, with a steep decrease between 2011 and 2014 for Valencia and 2011–2012 for Catalonia, and a more gradual rise from 2014 onwards.

Figure 3 shows time trends of treatment by drug class and for each sub-cohort. Treatment with bisphosphonates dropped, whereas denosumab treatment rose during the study period, showing an opposite pattern of use in all the regions. Parathyroid hormone use showed some fluctuations in all of the regions but with similar rates of use at the start and the end of the period in all sites but Navarre, where use decreased over time. Treatment with other antiosteoporotics declined in Catalonia and the Valencia Region, whereas it remained stable and very low in Basque Country and Navarre.

Time trends by age groups showed a consistent pattern over time (Supplementary Fig. 2). By sex, overall, the Mediterranean regions showed a persistent gap over time, whereas in the Northern regions, the gap was gradually reduced (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

We assessed the contemporary patterns of hip fracture secondary prevention in a population-based cohort of over 100,000 patients using real-world data of around one third of the Spanish population, distributed in four regions. This is arguably the largest cohort of patients with hip fracture assessing routine clinical practice data from the last decade when treatment patterns might have changed due to the introduction of denosumab, but the extent of its use in routine clinical practice is largely unknown. We found that a very high percentage of the whole cohort (≈ 78%) remained untreated within the first 3 months post-fracture. The most used treatment was oral bisphosphonates, followed by denosumab, with differences in antiosteoporotic (AO) treatment prevalence by region. Differences in therapeutic management by age were observed, with around a quarter of patients aged 84 and under being treated with AO, in contrast to under a fifth of those aged 85 and over. Regarding treatment by sex, females were treated in a higher proportion than males, with the former nearly doubling the proportion of the latter. We also found evidence of important differences between sub-cohorts in management by age and sex.

Regarding time trends, despite finding an increasing trend in AO treatment over time, prescription rates remained highly suboptimal. By drug class, we observed that treatment with bisphosphonates dropped, whereas denosumab treatment rose along the study period, showing an opposite pattern of use in all of the regions. Concerning management by sex, overall, the Mediterranean regions showed a persistent gap over time, whereas in the Northern regions, the gap was gradually reduced. In regard to management by age, treatment patterns after discharge by age groups were consistent over time.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to show data on bisphosphonates and denosumab prescription rates after hip fracture, separately, and trends over time, in a large population-based cohort using real-world data. Previous studies had considered any antiosteoporotic use [12, 19], shown denosumab use together with other AO such as calcitonin and PTH, given their incipient use [11], or found that only bisphosphonates were used [20]. This can be attributed to the fact that they analyzed data of about a decade ago or more, when denosumab was starting to be used. Knowing contemporary management patterns is important for the identification of current gaps of care in secondary prevention of hip fracture and the subsequent implementation of adequate strategies to reduce recurrent fractures in this frail population.

Therapeutic management after hip fracture

We found fairly or slightly better treatment rates than studies using data from 10 or more years ago [18, 20], but the treatment gap is still remarkable, with around 78% of patients remaining untreated. Bisphosphonates accounted for over 60% of all AO prescriptions, whereas denosumab represented a non-negligible 20%. It is not possible to compare these figures with existing evidence, as there are no published data on contemporary secondary prevention of hip fracture, and as stated before, available papers analyzed data of about a decade ago or more when denosumab use was only starting [11, 12, 19, 20]. It would be important to know if the uptake of denosumab has been similar in other settings.

Concerning management by age, we found that treatment rates were lowest in the eldest group (85 years old or above), but similar in the 65–74 and 75–84 years old groups, along the study period. These findings partially coincide with a Danish study, with data from about a decade ago, which also found the lowest treatment proportion among patients ≥ 85 y but different treatment rates between the 65–74 and 75–84 years old groups [20]. Age is associated with a higher risk of fracture and refracture [24], and therefore, it is worrisome that patients aged 85 + remain highly untreated, especially in settings with high life expectancy such as Spain. In our cohort, a percentage as high as 50% of patients was 85 years old and over. It is possible that clinical reasons such as important renal impairment or terminal cancer have influenced the decision not to treat some of these patients, but it is likely that many of these patients have indications for treatment.

Regarding management by sex, we found that treatment rates for females nearly doubled those of males in the study cohort, with important differences by region. A considerable gap between females and males for the secondary prevention of osteoporosis has been found previously in large cohorts in Denmark and Taiwan [18–20], including differences by region [19] coinciding with our results.

Temporal trends in secondary prevention of hip fracture

When observing temporal trends of overall treatment, we found that an increase in treatment rates was evident in the Northern regions, in contrast to the Mediterranean regions. Previous studies have reported differences in treatment rates by region in the UK [12] and Taiwan [19] but are not directly comparable as trends over time were not analyzed.

Regarding temporal trends by drug class, we found that bisphosphonates prescription decreased, whereas denosumab increased in all of the regions along the study period. As stated before, no previous studies have assessed bisphosphonates and denosumab separately, as available evidence refers to data of at least a decade ago, so we are not able to compare our results with existing literature. The information regarding overall treatment trends and by drug class according to region suggest that the introduction of denosumab has not considerably increased treatment rates but rather largely replaced treatment with bisphosphonates in the Mediterranean regions. There were no changes in drug coverage or availability during the study period that could justify the trend observed.

Regarding temporal trends of management after hip fracture by sex, differences among men and women were consistent along the study period in the Mediterranean regions. However, the Northern regions showed a different behavior, with a gap reduction between men and women over time. This is the first time that a gap reduction between men and women is reported, to the best of our knowledge. Other studies with contemporary data would be necessary to explore this trend in different settings.

It is important to bear in mind that some of the differences found by region might be (at least in part) explained by the differences in study periods (i.e., the period of study for Catalonia finishes before that of the rest of the cohorts/regions and different factors taking place at certain times might influence prescription trends). This feature has been described in previous studies in which there is not a complete overlap in time between regions, but still, the information derived from the study is quite informative, reliable, and valuable [11].

The stratified analysis by previous treatment with AO shows that most patients continued with the same treatment within 90 days after discharge, as expected. Those patients treated with a particular class of AO follow the same treatment after fracture, while those untreated mostly remain untreated. Patients from Basque Country and Navarre were more likely to switch from bisphosphonates to denosumab than in the other regions, as well as showing higher rates of treatment initiation with antiosteoporotics. On the other hand, it is important to consider that treatment with denosumab having the smallest discontinuation rate is probably due to its long duration (one injection every 6 months). As a result, a patient who is treated with denosumab prior to fracture but near the index date would count as treated both previously and within 90 days after discharge.

Several limitations must be acknowledged: In population-based cohort studies using real-world data, as the one presented here, bias such as differential recording, misclassification bias, or missing data might be present. However, the reliability of hospital discharge diagnoses due to acute conditions (such as hip fracture, which was the basis to construct our cohort) is expected to be very high. Electronic drug prescription information can also be considered highly reliable given the severity of the diagnosis. In addition, note that prescription data do not provide information regarding exposure of patients to drugs as dispensing data do. However, this fact does not substantially influence or hinder the importance of our results since the objective of the present manuscript is to assess therapeutical management by clinicians after a hip fracture, and prescription data is the most appropriate data to do so.

Some discussion is also needed regarding the choice of a 90-day follow-up period after the index hip fracture when defining treatment with antiosteoporotics. Recommendation given by clinical guides is to treat patients with AO medication after a hip fracture. Thus, we need to define a follow-up period in which a prescription with AO may be attributable to a hip fracture. Despite being possible to find patients with a delayed dispensing [27], its connection to this hip fracture might be less clear. A follow-up period of 90 days has been previously used in the literature and seems reasonable for defining treatment at discharge with AO. In addition, previous work within the Spanish context showed slight differences between 3 or 6 months of follow-up [11]. Restricting to 90-day survivors can be justified by the lethality of hip fractures, giving patients enough follow-up time to be treated. Nevertheless, some selection bias, as well as difficulties regarding generalization, should be considered.

Each region included different time periods of study and therefore, results of differences between them must be interpreted with caution in some cases; however, all regions—but Catalonia—show a good overlap between 2017 and 2020. The importance of this type of data, despite the limitation of not complete overlap in time, has been shown previously [11]. Moreover, the region of Navarre showed more variability in its annual trends of treatment, which is likely due to its small sample size compared to the other regions. On the other hand, disruptions in 2020 due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic could have influenced the trends shown. Finally, our results might not be generalized to other settings, and therefore, it would be advisable to generate evidence on the contemporary management of patients after hip fracture in different populations and/or health systems.

Conclusions

This large population-based study provides evidence of a slight increase in treatment rates and the maintenance of an important treatment gap in the contemporary secondary prevention of hip fracture in Spain, a decade after the introduction of denosumab. Our data shows a considerable uptake of denosumab in the management of these patients, as we found that bisphosphonates and denosumab accounted for 60 and 20% of the AO prescriptions, respectively, during the study period. Treatment gaps were most pronounced among patients aged 85 and over and males. It is noteworthy that we identified differences between regions by sex, with the Northern regions showing an important reduction in the treatment gap between males and females over time. Patterns of osteoporosis medications by age were similar among regions. Regarding drug classes, we found that bisphosphonates’ treatment dropped, whereas denosumab use rose along the study period, suggesting that the introduction of denosumab replaced bisphosphonates’ use, especially in the Mediterranean regions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Miss María Fernanda Carrillo-Arenas, Medical Records Technician of the Health Services Research & Pharmacoepidemiology Unit at FISABIO, for her assistance with the identification of diagnostic codes used to define comorbidities and with the elaboration of Supplementary Table 1.

Funding

This work has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the projects [PI14/00993, PI18/01675], “RD16/0001/0011 – Red Temática de Servicios de Salud Orientados a Enfermedades Crónicas (REDISSEC),” and “RD21/0016/0006 – Red de Investigación en Cronicidad, Atención Primaria y Promoción de la Salud (RICAPPS)” and co-funded by the European Union. FLC was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) [grant number FI19/00190] and co-funded by the European Union.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to legal restrictions on sharing the data set, regulated by each regional government. In the case of the Valencia Region, it is regulated by a legal resolution from the Valencia Health Agency [2009/13312]. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the Management Office of the Data Commission in the Valencia Health Agency (email: solicitud_datos@gva.es) for the Valencia Region; Navarre Health Data Base-Bardena (email: salsedrs@navarra.es) for the Region of Navarre; Basque Health Service-Osakidetza (email: SUBDIRECCION.COORDINACIONHOSPITALARIA@osakidetza.eus) for the Basque Country. In the case of Catalonia, the anonymized and unidentified data will be accessible to the research staff of the research centers accredited by the Research Centres of Catalonia (CERCA) institution https://cerca.cat/en/, Catalonia healthcare public agents (Catalan acronym SISCAT) https://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/coneix-catsalut/presentacio/model-sanitari-catala/siscat/, and public university research centres based in Catalonia, as well as the Catalan health administration through the Public Data Analysis for Health Research and Innovation Program of Catalonia (PADRIS) https://aquas.gencat.cat/ca/fem/intelligencia-analitica/padris/index.html.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van Oostwaard MM (2018) Osteoporosis and the nature of fragility fracture: an overview. In: Hertz K, Santy-Tomlinson J (eds) Fragility fracture nursing: Holistic care and management of the orthogeriatric patient. Springer, Cham, pp 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jönsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12):1726–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JP, Josse RG (2002) Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. Can Med Assoc J 67(10 Suppl):S1–S34 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanfélix-Genovés J, Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Peiró S, Hurtado I, Fluixà C, Fuertes A, Campos JC, Giner V, Baixauli C (2013) Prevalence of osteoporotic fracture risk factors and antiosteoporotic treatments in the Valencia region, Spain. The baseline characteristics of the ESOSVAL cohort. Osteoporos Int 24(3):1045–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Felipe R, Cáceres C, Cimas M, Dávila G, Fernández S, Ruiz T (2010) Clinical characteristics of patients under treatment for osteoporosis in a Primary Care Centre. Who do we treat? Aten Primaria 42(11):559–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Shawn Tracy C, Moineddin R, Upshur RE (2013) Osteoporosis prescribing trends in primary care: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Prim Health Care Res Dev 14(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu YM, Lee JY, Lee E (2017) Access to anti-osteoporosis medication after hip fracture in Korean elderly patients. Maturitas 103:54–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanfélix-Genovés J, Catalá-López F, Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Hurtado I, Baixauli C, Peiró S (2014) Variability in the recommendations for the clinical management of osteoporosis. Med Clin (Barc) 142(1):15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conley RB, Adib G, Adler RA, Åkesson KE, Alexander IM, Amenta KC, Blank RD, Brox WT, Carmody EE, Chapman-Novakofski K, Clarke BL, Cody KM, Cooper C, Crandall CJ, Dirschl DR, Eagen TJ, Elderkin AL, Fujita M, Greenspan SL, Halbout P, Hochberg MC, Javaid M, Jeray KJ, Kearns AE, King T, Koinis TF, Koontz JS, Kužma M, Lindsey C, Lorentzon M, Lyritis GP, Michaud LB, Miciano A, Morin SN, Mujahid N, Napoli N, Olenginski TP, Puzas JE, Rizou S, Rosen CJ, Saag K, Thompson E, Tosi LL, Tracer H, Khosla S, Kiel DP (2020) Secondary fracture prevention: consensus clinical recommendations from a multistakeholder coalition. J Bone Miner Res 35(1):36–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SC, Kim MS, Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Song HJ, Liu J, Hurtado I, Peiró S, Lee J, Choi NK, Park BJ, Avorn J (2015) Use of osteoporosis medications after hospitalization for hip fracture: a cross-national study. Am J Med 128(5):519-526.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah A, Prieto-Alhambra D, Hawley S, Delmestri A, Lippett J, Cooper C, Judge A, Javaid MK, REFReSH study team (2017) Geographic variation in secondary fracture prevention after a hip fracture during 1999–2013: a UK study. Osteoporos Int 28(1):169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prieto-Alhambra D, Reyes C, Sainz MS, González-Macías J, Delgado LG, Bouzón CA, Gañan SM, Miedes DM, Vaquero-Cervino E, Bardaji MFB, Herrando LE, Baztán FB, Ferrer BL, Perez-Coto I, Bueno GA, Mora-Fernandez J, Doñate TE, Blasco JM, Aguado-Maestro I, Sáez-López P, Doménech MS, Climent-Peris V, Rodríguez ÁD, Sardiñas HK, Gómez ÓT, Serra JT, Caeiro-Rey JR, Cano IA, Carsi MB, Etxebarria-Foronda I, Hernández JDA, Solis JR, Suau OT, Nogués X, Herrera A, Díez-Perez A (2018) In-hospital care, complications, and 4-month mortality following a hip or proximal femur fracture: the Spanish registry of osteoporotic femur fractures prospective cohort study. Arch Osteoporos 13(1):96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor L, Kimata C, Siu AM, Andrews SN, Purohit P, Yamauchi M, Bratincsak A, Woo R, Nakasone CK, Lim SY (2021) Osteoporosis treatment rates after hip fracture 2011–2019 in Hawaii: undertreatment of men after hip fractures. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 7(3):103–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klop C, Gibson-Smith D, Elders PJ, Welsing PM, Leufkens HG, Harvey NC, Bijlsma JW, van Staa TP, de Vries F (2015) Anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing after hip fracture in the UK: 2000–2010. Osteoporos Int 26(7):1919–1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamboa A, Duaso E, Marimón P, Sandiumenge M, Escalante E, Lumbreras C, Tarrida A (2018) Oral bisphosphonate prescription and non-adherence at 12 months in patients with hip fractures treated in an acute geriatric unit. Osteoporos Int 29(10):2309–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malle O, Borgstroem F, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Svedbom A, Dimai SV, Dimai HP (2021) Mind the gap: incidence of osteoporosis treatment after an osteoporotic fracture - results of the Austrian branch of the International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (ICUROS). Bone 142:115071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skjødt MK, Ernst MT, Khalid S, Libanati C, Cooper C, Delmestri A, Rubin KH, Javaid MK, Martinez-Laguna D, Toth E, Prieto-Alhambra D, Abrahamsen B (2021) The treatment gap after major osteoporotic fractures in Denmark 2005–2014: a combined analysis including both prescription-based and hospital-administered anti-osteoporosis medications. Osteoporos Int 32(10):1961–1971. 10.1007/s00198-021-05890-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang CY, Fu SH, Huang CC, Hung CC, Yang RS, Hsiao FY (2018) Visualisation of the unmet treatment need of osteoporotic fracture in Taiwan: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Clin Pract 72(10):e13246. 10.1111/ijcp.13246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristensen PK, Ehrenstein V, Shetty N, Pedersen AB (2019) Use of anti-osteoporosis medication dispensing by patients with hip fracture: could we do better? Osteoporos Int 30(9):1817–1825. 10.1007/s00198-019-05066-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Population Aging 1950–2050. Department of economic and social affairs. Population Division. United Nations 2001. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2021/Nov/undesa_pd_2002_wpa_1950-2050_web.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2025

- 22.United Nations. Department for Economic, and Policy Analysis. World Economic and Social Survey. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis, 2007.

- 23.Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel JP, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Epping-Jordan JE, Peeters GMEEG, Mahanani WR, Thiyagarajan JA, Chatterji S (2016) The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 387(10033):2145–2154. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llopis-Cardona F, Armero C, Hurtado I, García-Sempere A, Peiró S, Rodríguez-Bernal CL, Sanfélix-Gimeno G (2022) Incidence of subsequent hip fracture and mortality in elderly patients: a multistate population-based cohort study in Eastern Spain. J Bone Miner Res 37(6):1200–1208. 10.1002/jbmr.4562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrahamsen B (2024) Treating osteoporosis in the oldest old. J Bone Miner Res 39(6):629–630. 10.1093/jbmr/zjae045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org

- 27.Leung MTY, Turner JP, Marquina C, Ilomaki J, Tran T, Bell JS (2024) Trajectories of oral bisphosphonate use after hip fractures: a population-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int 35(4):669–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to legal restrictions on sharing the data set, regulated by each regional government. In the case of the Valencia Region, it is regulated by a legal resolution from the Valencia Health Agency [2009/13312]. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the Management Office of the Data Commission in the Valencia Health Agency (email: solicitud_datos@gva.es) for the Valencia Region; Navarre Health Data Base-Bardena (email: salsedrs@navarra.es) for the Region of Navarre; Basque Health Service-Osakidetza (email: SUBDIRECCION.COORDINACIONHOSPITALARIA@osakidetza.eus) for the Basque Country. In the case of Catalonia, the anonymized and unidentified data will be accessible to the research staff of the research centers accredited by the Research Centres of Catalonia (CERCA) institution https://cerca.cat/en/, Catalonia healthcare public agents (Catalan acronym SISCAT) https://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/coneix-catsalut/presentacio/model-sanitari-catala/siscat/, and public university research centres based in Catalonia, as well as the Catalan health administration through the Public Data Analysis for Health Research and Innovation Program of Catalonia (PADRIS) https://aquas.gencat.cat/ca/fem/intelligencia-analitica/padris/index.html.