Abstract

As the global population ages, enhancing community outdoor public spaces to accommodate the needs of senior citizens has emerged as a critical challenge. This research delves into the intricate relationship between community outdoor public spaces and the behavioral patterns of the elderly, seeking to inform strategies for optimizing these spaces. The complexity and diversity of the mechanisms linking elderly behaviors with the characteristics of their outdoor environments pose challenges in identifying clear guidelines for improvement. Traditional methods of collecting behavioral data, such as questionnaires and manual observations, are time-consuming and limit the scope and detail of data captured. In contrast, computer vision technologies offer an efficient alternative for gathering behavioral data. However, the application of computer vision to specifically identify various behaviors of the elderly population presents certain challenges. This study addresses two key issues: improving the use of computer vision to recognize diverse behaviors of the elderly; and elucidating how community outdoor public spaces shape the outdoor activities of seniors and identifying crucial influencing factors. The research proceeds by initially categorizing elderly behavior characteristics and typologies of outdoor public spaces based on the physiological and psychological needs of seniors. The spatial elements are classified into four metrics: spatial, greenness, functional facilities, and accessibility. A computer vision-based behavior detection algorithm is then constructed to effectively identify six typical activities of the elderly: exercising, jogging, sitting, standing, walking, and playing chess or cards. Subsequently, a set of quantifiable indicators for community outdoor public spaces is established, and nonlinear machine learning models (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, and eXtreme Gradient Boosting) are employed to reveal the association mechanisms between these six behaviors and the four categories of spatial metrics. The findings highlight 16 major characteristics that have a significant impact on elderly behavior, such as area size, form, green enclosure, and types of workout equipment.

Keywords: Elderly behavior, Association mechanisms, Community outdoor public spaces

Subject terms: Environmental impact, Psychology and behaviour

Introduction

With the steady rise in the proportion of elderly populations worldwide, addressing the challenges of an aging society has become a global imperative. Extensive research has indicated the positive effects of outdoor activities on the physical and mental well-being of seniors1–8. Community outdoor public spaces, serving as the primary venues for the outdoor activities of the elderly, directly influence the quality of their outdoor activities through their spatial environmental characteristics. Seniors are more sensitive to external environmental conditions and possess lower adaptability, making the quality of these spaces vital for facilitating their outdoor engagement. To better tailor community outdoor spaces to the needs of seniors, this research will seek solutions by exploring the linkages between these spaces and elderly behaviors.

The behaviors of seniors in public spaces are multifaceted, as are the compositional elements of these spaces, rendering the “space-behavior” relationship both diverse and complex. Prior studies have often focused on specific behaviors such as dangerous9, sedentary10, or walking behaviors11,12 of seniors. There is a deficiency in studying the multitude of behaviors exhibited by the elderly in community outdoor public spaces, and there exists a limitation in proposing comprehensive optimization strategies for community outdoor public spaces tailored to different elderly behaviors. Therefore, further deepening of the research into the “space-behavior” linkage mechanisms is warranted.

This study aims to address the following questions: How can computer vision be more effectively utilized to identify the elderly population and their diverse behaviors? And how do community outdoor public spaces influence the outdoor activities of the elderly, with a focus on the key elements? Initially, the research will categorize the behavioral characteristics of the elderly and the types of community outdoor public spaces. It will then explore the behavioral needs of the elderly in outdoor activities, considering their physiological and psychological traits, and groups the elements of community outdoor public spaces into spatial indicators, greenery indicators, functional facility indicators, and accessibility indicators. Subsequently, the study will construct a computer vision-based behavior detection algorithm to effectively recognize six distinct behaviors of the elderly: exercising, jogging, sitting, standing, walking, and playing chess or cards. Ultimately, the research will establish quantitative indicators for community outdoor public spaces and employ three nonlinear machine learning models (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, and XGBoost) to elucidate the mechanisms linking the six behaviors of the elderly with the four categories of spatial quantitative indicators. The study will also identify key indicator elements that significantly impact the behaviors of the elderly.

By exploring the relationship between specific design indicators of public outdoor spaces and the behavioral patterns of older people, this study aims to identify key spatial features and their mechanisms of influence on behavior. By establishing these associations, the research will provide designers with data-driven evidence to adjust spatial indicators, thereby optimizing age-friendly spatial design and promoting older people’ activity participation and well-being.

Related works

Characteristics of elderly behavior

As people age, there is a noticeable decline in several functions of the elderly, which are primarily manifested as follows: (1) Degeneration of the sensory system, which includes vision, touch, smell, and hearing. These are the channels by which human receive external information, hence the elderly may have delayed perception and misconceptions of the outside world. (2) Degeneration of the nervous system. Cognitive functions such as the elderly’s reaction capacity, memory, and reasoning ability gradually deteriorate13,14. (3) Degeneration of the musculoskeletal system. Due to the gradual degeneration of the elderly’s upper and lower limb mobility and physical strength15, flexibility and balance are reduced, resulting in an increased risk of falls, and a slower pace of life.

The prolonged degeneration of physical functions leads to difficulties in the daily lives of the elderly and can easily induce chronic diseases, causing great suffering and subsequently leading to negative emotions and mental health issues16. These may include feelings of loss, loneliness, frustration, anxiety, and other psychological problems. The elderly’s decrease in social activities exacerbates feelings of loneliness, and prolonged loneliness and social isolation may further promote depression17.

Types and constituent elements of community outdoor public spaces

The quantifiable measurement of spatial elements as a vital foundation for spatial analysis, with environmental factors that influence human behavior broadly categorized into spatial entities and physical environments. Spatial entities encompass tangible, locatable elements such as buildings, landscapes, facilities and else, whereas the physical environment involves various ambient features perceived within space, including temperature, noise levels, and wind velocities. Unlike the volatility of physical environments, once established, spatial entities endure as long-term determinants of human behavior. This study primarily focuses on the exploration of spatial entities.

Quantitative measurements facilitate the formation of objective data, enabling spatial analysis and comprehension of spatial characteristics. Given the varying impacts of different spatial elements on diverse behaviors, the integration of these components with behavioral research is essential. In quantifying spatial entities, parameters often include location, scale, area, height, and the interrelationships among distinct spatial entities. Dong et al. (2022) delineated indicators such as spatial scale, shape, terrain slope, step count, green view ratio, interface permeability, and the proportion of canopy coverage in their investigation of environmental attributes affecting the elderly’s risky behaviors9. Yang et al. (2023), in their study of resident-driven construction of public spaces, categorized the environmental elements influencing resident behavior into planning layout, spatial form, spatial quality, and physical attributes. They included metrics such as the area of public space per capita, the area of green space per capita, spatial scale, spatial capacity, site gradient, surrounding building height, spatial enclosure, sky visibility, greenery visibility, area of green space, accessible green space area, and water body area, among others18. Zhang et al. (2023) proposed a framework for analyzing the morphology of small spaces, focusing on spatial pattern and composition, usage, and quality, detailed with indices such as urban texture, spatial density, uniformity of distribution, connectivity, compactness, public accessibility, scale, boundaries, functionality, and landscape design19.

Application of computer vision in behavioral studies

Advancements in computer vision have introduced novel technical approaches to urban studies, with scholars increasingly integrating this technology into their research. The specific research methodologies are as follows.

Quantitative analysis of spatial utilization through pedestrian counting. Scholars such as Wei et al. (2005) have utilized head detection algorithms to enumerate the number of users entering a space and those seated around fountains, assessing the quality of architectural design from a usage standpoint20. Hou et al. (2020) furthered this by pinpointing pedestrian positions within images and interpreting how these individuals utilize space21.

Extracting pedestrian distribution data to explore behavioral spatial traits. Primarily, urban inhabitant activity data is gathered via cameras or drones, and pedestrian trajectories are identified using computer vision algorithms to analyze distribution patterns. Liang et al. (2020) documented walking speeds with computer vision techniques and investigated weather and climate effects on pedestrian motion22, while Jiao et al. (2023) revealed variations in walking speeds across different street segments23.

Identifying pedestrian attributes and segmenting populations for analyzing preferences. Distinct populations are categorized based on attributes like gender and age, allowing for an exploration of differential spatial behavior patterns. Wong et al. (2021) provided a more granular segmentation of pedestrians, dividing them into categories based on age and gender, such as youth, adult, and elderly groups. Through a four-stage process that includes pedestrian detection, feature extraction, identity tracking, and motion analysis, they achieved the identification and tracking of pedestrian attributes, thereby obtaining refined information on pedestrian trajectories24.

Identifying various types of behaviors and establishing space-behavior correlations. Wang and He (2023) categorized outdoor public spaces into three types and utilized computer vision detection algorithms to recognize and monitor six distinct behaviors among children, adults, and the elderly. This approach sought to uncover the relationships between demographic groups, behaviors, and the spatial settings25. In 2025, Wang and He based on the same behavior detection algorithm, further explored the spatiotemporal characteristics of older people’ behaviors26.

Impact of public spaces on the behavior of the elderly

Delving into the mechanisms linking behavior and space, much scholarly work focuses on the multifaceted impact of spatial factors on human behavior. The diversity and complexity of these influences stem from the varied nature of spatial elements and their differential effects on distinct behaviors. Sun et al. (2020) conducted an empirical study to ascertain the influence of small-scale spatial attributes on the social interactions of the elderly. The findings indicated that moderate street widths, an abundance of seating, and low ambient noise levels were significantly associated with increased frequencies of social engagement across a spectrum of 29 observed behaviors among the senior population27. Liu et al. (2021) executed a comprehensive survey among the elderly in Dalian, China, to delineate the effects of park accessibility on sedentary behaviors, leisurely strolls, and errand-related activities. Through a meticulous analysis of the correlation between neighborhood characteristics and the incidence of specific outdoor activities, the study revealed that proximity to the nearest park, specifically within a range of less than 800 meters, was inversely correlated with the frequency of sedentary behaviors among the elderly. Intriguingly, a distance between 800 to 1200 meters was found to be conducive to supporting leisure walking habits among frequent strollers28. Dong et al. (2022) focused on the observation of hazardous behaviors prevalent among the elderly, identifying five primary categories of risk: falls, collisions, sprains, exhaustion, and disorientation. The research delved into the spatial determinants of these behaviors, examining factors such as spatial dimensions, the uniformity of terrain, and the quality of the lighting environment9. Monica et al. (2022) surveyed dense urban areas in Southeast Asian countries and regions, including China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, studying the attributes of public open spaces and their association with physical activity and sedentary behavior. The results indicated a positive correlation between the distance and quantity of public open spaces and physical activity, while areas within public open spaces that are close to water features and corridors are associated with more sedentary behavior10. Zhou et al. (2022) leveraged data from the Nanjing Household Travel Survey to highlight a discrepancy between the transportation needs and the supply available to the elderly. The research scrutinized the impact of familial and personal attributes, travel patterns, local amenities, and public transit systems on the elderly’s preference for public transportation and walking as modes of travel29. C. Perchoux et al. (2023) utilized GPS to record individuals’ exposure time in different environments, examining the impact of green spaces (percentage of parks and forests), streets (bicycle lane density), amenity density, and bus stop density on location- and trip-based sedentary behavior. They found that higher street connectivity was negatively correlated with total lingering time30. Renjiang Xiong (2024) investigated the spatial heterogeneity of the objective built environment’s impact on older people’ walking distance in mountainous cities. The results indicated that slope was negatively correlated with walking distance, while the density of recreational venues and proximity to the nearest bus stop had a positive effect. Land use mix and road density exhibited localized positive and negative effects on walking distance12.

These studies adopted data-driven approaches to quantify the relationship between spatial factors and older people’ behaviors, revealing the profound impact of public space design on their behavioral patterns. By employing data collection methods such as field observations, questionnaires, and behavioral mapping, combined with techniques like statistical analysis, spatial analysis, these studies precisely characterized the complex relationship between spatial attributes and older people’ behaviors. These data-driven methods overcome the limitations of traditional qualitative research through large sample data and objective indicators. The refined modeling of the interaction between elderly behavior and space can further reveal the spatial driving factors behind the behavior. It provides an operational basis for the precise optimization of urban public space design.

Study area and data

Study area

This study has chosen certain communities within the Bajiao Subdistrict of the Shijingshan District in Beijing (See Fig. 1) as the research site. According to the Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2022, the permanent resident population in 2021 was 566k, with 96k residents aged 65 and above accounting for almost 17%. This percentage is higher than the average proportion of the elderly population in Beijing (See Fig. 2), suggesting a serious aging situation. The Shijingshan District includes 9 subdistricts, one of which is the Bajiao Subdistrict. It boasts a permanent resident population of 110,000, the highest in the district, which underscores its large population size. With a rich history of development, Bajiao Subdistrict is characterized by numerous mature residential communities and a substantial elderly population. This demographic profile offers a valuable case study for research into the behavioral characteristics of the elderly.

Fig. 1.

Location map of Bajiao subdistrict.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of elderly population aged 65 and above in each district of Beijing City (Source: Compiled by the author from the Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2022).

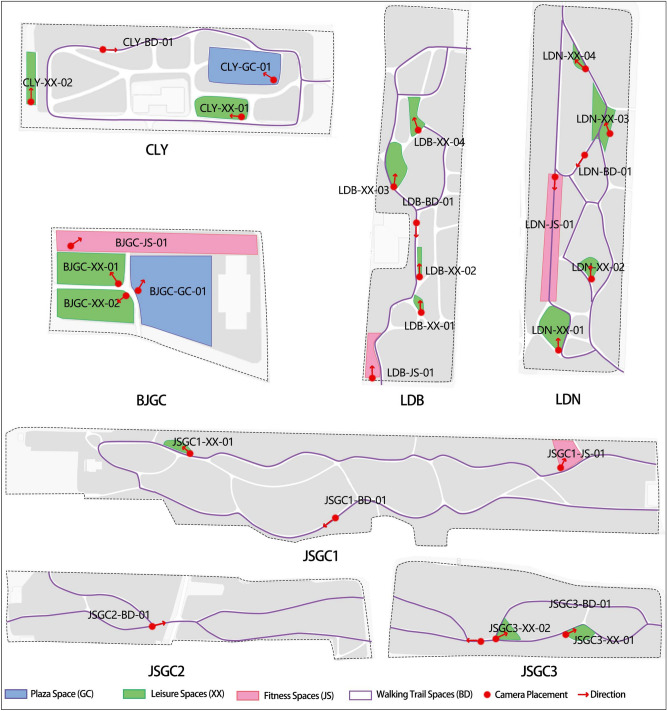

Through field research and site visits, the study selected outdoor public spaces within the Bajiao Subdistrict that are popular among the elderly and exhibit typical and distinctive environmental characteristics. The classification was based on the types of activities that occur in these spaces, leading to the final determination of four distinct types of community outdoor public spaces, encompassing a total of 27 sampled spaces. These include plaza spaces, leisure spaces, fitness spaces, and walking trail spaces, each of which has been coded accordingly (See Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Spatial samples and their corresponding codes.

To ensure the representativeness and diversity of the research sample, this study selected community outdoor public spaces in Bajiao Subdistrict with high older adult activity, typical environmental characteristics, and diversity through field investigations and visits. The selection of spaces adhered to the following principles:

1. Aggregation of older people’ Activities: Priority was given to public spaces with high frequency of daily activities among older people. Through preliminary observations and interviews with community management, these locations were confirmed as primary gathering areas for older people, such as popular spots for morning exercises, walking, or socializing.

2. Richness of Environmental Characteristics: Based on the function and physical features of the spaces (e.g., area, facilities, greenery level, and path layout), the samples were categorized into four types: plaza spaces (open activity areas), leisure spaces (primarily for rest and socializing), fitness spaces (equipped with exercise facilities), and pathway spaces (linear walking paths). This ensured a wide distribution of spatial indicator data.

3. Sample Representativeness: As a typical urban community, Bajiao Subdistrict outdoor public spaces are highly representative in terms of function and design. The selection of 27 sample spaces ensured coverage of locations with varying scales, layouts, and usage patterns, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the research findings.

In the end, four types of community outdoor public spaces were identified, comprising a total of 27 sample spaces, including plaza spaces, leisure spaces, fitness spaces, and pathway spaces, each of which was coded accordingly (See Fig. 3).

To ensure the comprehensiveness and accuracy of data collection, this study employed three smartphones for video recording, configured at 2K resolution (2048 * 1536 pixels) with a frame rate of 30 fps. The devices were positioned at vantage points or locations with open views to minimize blind spots. The cameras were uniformly installed at a height of 2 meters with a downward tilt angle of  to avoid occlusion and overlapping of individuals.

to avoid occlusion and overlapping of individuals.

The shooting locations are illustrated in Fig. 3, with arrows indicating the primary shooting directions. Each sampling point was collected from 9:00 to 18:00, with a time interval of 1 minute, and the collection lasted for 9 hours. 540 behavioral images were obtained at each sampling point. A total of 14,580 behavioral images were collected from 27 spatial samples. Due to the large number of spatial scenes to be monitored and the inability to cover all areas simultaneously, a time-segmented and location-specific collection strategy was adopted. Specifically, within a given time period, three locations were recorded simultaneously. After completing the behavioral video collection for one area, the equipment was relocated to other scenes for subsequent data collection.

Data

(1) Behavioral Data

The collection of behavioral data in this study employs computer vision-based behavior detection algorithms, following the systematic process outlined in Fig. 4. Initially, appropriate locations within the site are selected for camera setup to record the activities of the elderly. Recorded videos are then extracted and processed using Python scripts to conform to the video format requirements stipulated by the computer vision behavior detection algorithm. Subsequently, these visually captured datasets are subjected to a computer vision behavior detection model, as adopted from the literature25, enabling the identification and extraction of specific behavioral patterns exhibited by the elderly population.

Fig. 4.

Behavioral data collection workflow.

Based on the preliminary investigation and analysis of older people behaviors, the most frequent activities in outdoor public spaces were identified as exercises, jogging, sitting, walking, standing, and chess/cards . These six activities encompass physical activities (e.g., exercise, jogging, walking), static rest (e.g., sitting, standing), and social interactions (e.g., chess/card), reflecting the daily behavioral habits of older people. Furthermore, these behaviors exhibit distinct motion characteristics and spatial usage patterns, making them highly recognizable for computer vision algorithms. Based on the above survey results and comprehensive consideration of the applicability of the algorithm, it was finally decided to conduct further research on these six behaviors.

(2) Spatial Data

Spatial characteristics represent the fundamental qualities and unique attributes of a given space, encompassing dimensions such as spatial type, form, scale, compositional elements, and functional properties. In this study, we employ a holistic methodology that integrates spatial form, scale, and compositional elements with practical considerations derived from site-specific observations. This approach allows us to construct a comprehensive suite of spatial characteristic indicators, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Spatial feature indicators and descriptions.

| Category | Spatial Element | Shortcuts | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Indicators | Spatial Scale | SSL |  |

Spatial Area |

| Spatial Shape | SSP | - | Aspect Ratio (Length to Width) | |

| Enclosure Degree | ED | - | Length Enclosed by Elements / Perimeter of Space | |

| Green Enclosure Degree | GED | - | Length Enclosed by Vegetation / Perimeter of Space | |

| Number of Steps | NS | Count | / | |

| Elevation Change | EC | m | Highest Point - Lowest Point of the Site | |

| Green Indicators | Green Envelopment | GE | - | Length Enclosed by Plants / Perimeter of Space |

| Green Space Area | GSA |  |

Grass, Shrub Coverage Area, Excluding Trees | |

| Tree Canopy Area Ratio | TCAR | - | Vertical Projection Area of Tree Canopy | |

| Facility Indicators | Building Area | BA |  |

Vertical Projection Area of Structures Such as Pavilions and Canopies |

| Seating Area | SA |  |

Area of Seating Available on Chairs, Planters, etc. | |

| Number of Fitness Facilities | NFF | Count | / | |

| Types of Fitness Facilities | TFF | Categories | / | |

| Fitness Facility Density | FFD | Count per Square Meter | Number of Fitness Facilities / Spatial Area | |

| Number of Chess and Card Tables and Chairs | NCCTC | Count | / | |

| Density of Chess and Card Tables and Chairs | DCCTC | Count per Square Meter | Number of Chess and Card Facilities / Spatial Area | |

| Accessibility Indicators | Population Served | PS | People | Number of Residents within a 10-Minute Walking Radius |

| Number of Entrances | NE | Count | Number of Access Points |

- denotes no unit specified.

Behavior definition and behavior detection

(1) Behavior Definition

This study focuses on six common behaviors of older people in outdoor public spaces: exercise with equipment, jogging, sitting, walking, standing, and chess/card games. As behavioral detection algorithms are inherently image processing techniques, the definition of each behavior centers on visual features extractable by the algorithm, providing interpretable classification criteria for behavioral detection. These are specified as follows:

Exercises: refers to all behaviors using fitness equipment, excluding other fitness behaviors without fitness equipment. The detection features are visual features with fitness equipment.

Jogging: Characterized by rapid alternation of legs, forward-leaning posture, and hands raised to chest level. Detection focuses on forward tilt and arm movements.

Sitting: refers to a posture with a low center of gravity, hips close to horizontal, and legs bent, with or without support (such as chairs, ground).

Walking: The legs move slowly and alternately, the body is upright, the arms swing naturally, and the gait is continuous.

Standing: The body is upright, the legs are straight, and there is no obvious step or posture swing.

Playing Chess/Card Games: refers to a scene in a sitting state accompanied by a chess, cards or similar props, with the characteristics of multiple people playing chess and gathering to watch. It detects typical hand movements, multiple people playing chess, and onlookers.

(2) Behavior Detection

The behavior detection algorithm developed in this study integrates multiple algorithms and tasks, comprising object detection, pedestrian attribute recognition, and behavior recognition (Fig. 5). Object detection extracts the “person” target from input images and obtains corresponding location information. Subsequently, the pedestrian attribute recognition algorithm identifies attributes to filter out the older people group and classify by gender. Finally, the behavior recognition algorithm assigns behavior labels to determine the corresponding behavior type.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of the computer vision behavior detection algorithm.

The behavior detection algorithm is built based on pytorch, and the hardware configuration is NVIDIA RTX A5000 24GB GPUs. The Adam algorithm is used to optimize the network, and the hyperparameter settings are shown in Table 2. The model training data set has a total of 17,000 images, which are randomly divided into training set and test set in a ratio of 6:425. The performance of the model is shown in Table 3

Table 2.

Hyper-parameter settings.

| Hyper-parameter | Setup |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 128 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Epochs | 50 |

Data are from25.

Table 3.

Performance of behaviour detection algorithms.

| Metric | Accu. | Prec. | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | 85 | 86 | 83 | 86 |

Data are from25.

Methodology

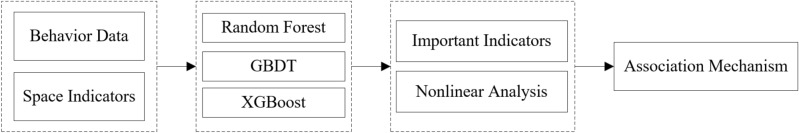

The construction of a methodological framework aims to study the nonlinear relationship between community outdoor public spaces and behavior. As shown in Fig. 6, this framework encompasses two key steps: (1) The employment of three machine learning models (RF, GBDT, XGBoost) to model the relationship between spatial indicators and the behavior of the elderly, respectively; (2) The use of SHAP to interpret the three machine learning models, thereby obtaining spatial indicators with uniform explanations and a rich understanding of their influence on behavior. The details are as follows.

Fig. 6.

Association mechanism analysis framework diagram.

Nonlinear relationship models in machine learning

Machine learning offers a multitude of models for handling nonlinear relationships, such as polynomial regression, logistic regression, decision trees, random forests (RF), gradient boosting decision trees (GBDT), and extreme gradient boosting models (XGBoost). Different models exhibit varying performances in data processing. To mitigate errors in nonlinear relationships caused by different model performance, this study integrates the three models RF, GBDT, and XGBoost to jointly explore the nonlinear correlations between spatial indicators and types of behavior.

The data was randomly split into a training set (60%) and a testing set (40%), and the training results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Performance of machine learning models.

Performance of machine learning models.

| Model | Training Set | Testing Set |

|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.97 | 0.91 |

| GBDT | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| XGBoost | 0.96 | 0.93 |

Machine learning interpretation model

This paper utilizes SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) as the machine learning interpretation model31,32, which provides a unified measure for the importance of each feature. There are two methods of interpretation: global and local approaches.

Result and discussions

Results of importance ranking

Comparing the three machine learning models, there is a certain consistency in the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for behavior, and these indicators with uniform explanations are highlighted in the analysis.

Figure 7 (a), (b) and (c) respectively display the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for the “exercising” behavior according to the three models. In the RF model, the top four influential variables are the type of fitness equipment, fitness equipment density, number of fitness facilities, and spatial scale. In the GBDT model, the top four influential variables are the type of fitness equipment, fitness equipment density, enclosure degree, and number of steps. In the XGBoost model, the top four influential variables are the type of fitness equipment, spatial scale, number of fitness facilities, and spatial shape. Among them, the variable “type of fitness equipment” ranks first in importance across all three models (RF, GBDT, XGBoost, same below), with uniform explanations, while other variables exhibit significant differences in their interpretations.

Fig. 7.

Importance ranking of spatial feature indicators on exercising behavior under three models (a) RF model (b) GBDT model (c) XGBoost model.

Figure 8 (a), (b) and (c) respectively illustrate the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for “jogging” behavior according to the three models. In the RF model, the three most influential variables are the number of entrances, spatial shape, and spatial scale. In the GBDT model, the three most influential variables are the number of entrances, spatial shape, and the number of people served. In the XGBoost model, the most influential variable is spatial scale alone. The variables of the number of entrances and spatial shape are interpreted similarly in both the RF and GBDT models, while the interpretations of other variables show greater variability.

Fig. 8.

Importance ranking of spatial feature indicators on jogging behavior under three models (a) RF model (b) GBDT model (c) XGBoost model.

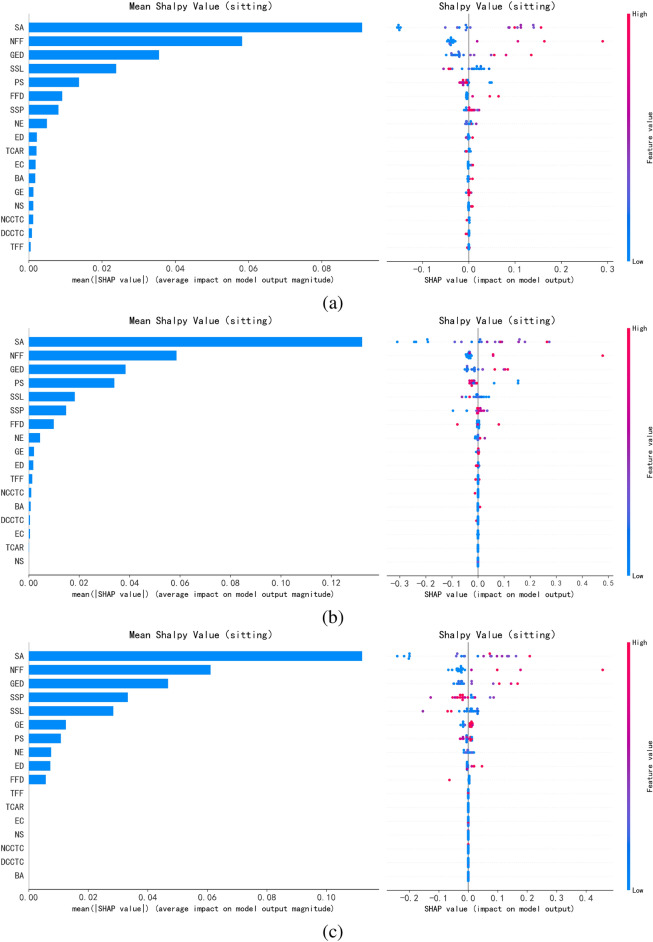

Figure 9 (a), (b) and (c) respectively illustrate the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for “sitting” behavior according to the three models. In the RF model, the four most influential variables are the sitting area, the number of fitness facilities, green enclosure degree, and spatial scale. In the GBDT model, the four most influential variables are the sitting area, the number of fitness facilities, green enclosure degree, and the number of people served. In the XGBoost model, the four most influential variables are the sitting area, the number of fitness facilities, green enclosure degree, and spatial shape. The variables of sitting area, the number of fitness facilities, and green enclosure degree are interpreted similarly across all three models. However, the spatial scale is interpreted differently in the XGBoost model compared to the RF and GBDT models.

Fig. 9.

Importance ranking of spatial feature indicators on sitting behavior under three models (a) RF model (b) GBDT model (c) XGBoost mode.

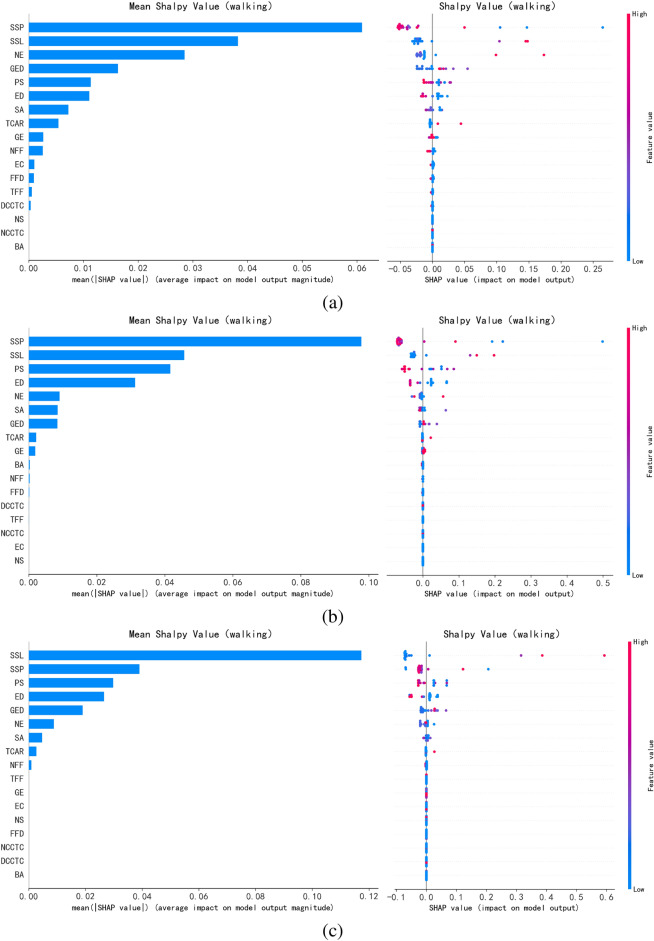

Figure 10 (a), (b) and (c) respectively present the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for walking behavior as determined by the three models. In the RF model, the four most influential variables are spatial shape, spatial scale, number of entrances, and green enclosure degree. In the GBDT model, the four most influential variables are spatial scale, spatial shape, number of people served, and enclosure degree. In the XGBoost model, the four most influential variables are spatial scale, spatial shape, number of people served, and enclosure degree. The variables of spatial scale, spatial shape, number of people served, and enclosure degree are interpreted similarly in both the GBDT and XGBoost models, whereas they are interpreted differently in the RF model.

Fig. 10.

Importance ranking of spatial feature indicators on walking behavior under three models (a) RF model (b) GBDT model (c) XGBoost mode.

Figure 11 (a), (b) and (c) respectively illustrate the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for standing behavior according to the three models. In the RF model, the four most influential variables are the sitting area, spatial shape, spatial scale, and the number of fitness facilities. In the GBDT model, the four most influential variables are spatial shape, sitting area, spatial scale, and the number of fitness facilities. In the XGBoost model, the four most influential variables are spatial shape, spatial scale, sitting area, and the number of fitness facilities. Among these, the sitting area, spatial shape, and spatial scale are consistently ranked in the top three across all three models, with only the order varying. The variable of the number of fitness facilities holds the same ranking (fourth) in all models.

Fig. 11.

Importance ranking of spatial feature indicators on standing behavior under three models (a) RF model (b) GBDT model (c) XGBoost mode.

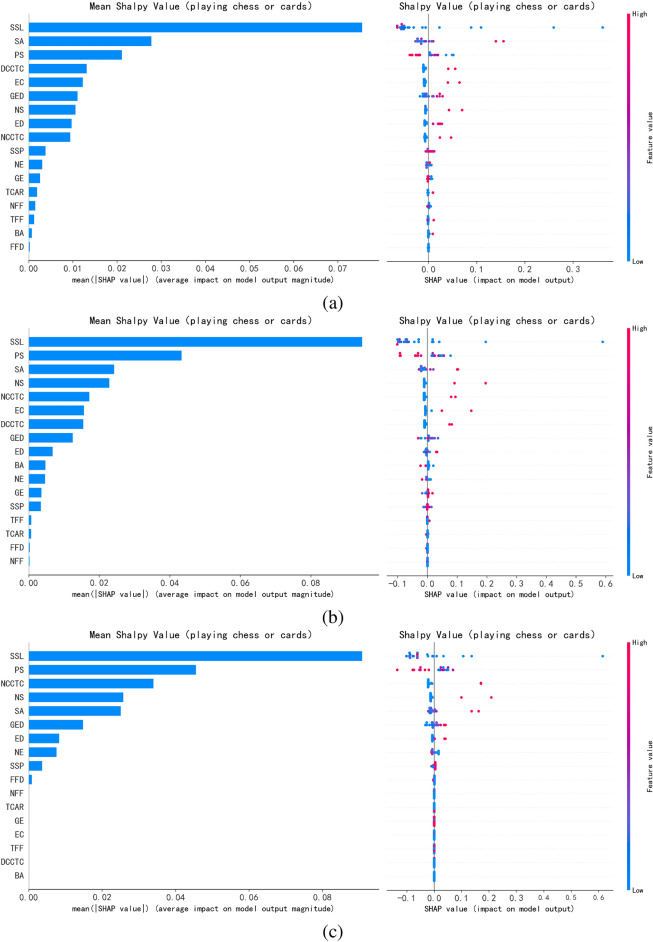

Figure 12 (a), (b) and (c) respectively show the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for chess and card playing behavior according to the three models. In the RF model, the four most influential variables are spatial scale, sitting area, number of people served, and the density of chess and card tables and chairs. In the GBDT model, the four most influential variables are spatial scale, number of people served, sitting area, and the number of steps. In the XGBoost model, the four most influential variables are spatial scale, number of people served, the number of chess and card tables, and the number of steps. The variable of spatial scale ranks first in importance across all three models, while there are differences in the importance ranking for the sitting area, number of people served, and the density of chess and card tables and chairs.

Fig. 12.

Importance ranking of spatial feature indicators on chess and card playing behavior under three models (a) RF model (b) GBDT model (c) XGBoost mode.

Integrating the descriptions of the importance ranking of spatial feature indicators for behavior from the three models, the indicators with consistent interpretations across all models are as follows: the variety of fitness equipment (+) for exercise; seating area (+), number of fitness facilities (+), and degree of green enclosure (+) for sitting, and spatial scale (+) for chess and card playing. Indicators with consistent interpretations across two models include: fitness equipment density (+) for exercise, number of entrances (+), spatial shape (-) for jogging, spatial scale (+), spatial shape (-), and population served (-) for walking, spatial shape (+), spatial scale (-) for standing, and the number of chess and card tables (+) for chess and card playing. The different machine learning models exhibit a degree of uniformity in the importance ranking of various feature variables, as depicted in Table 5.

Table 5.

spatial feature indicators with same interpretation under the three modes.

| First | Second | Third | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | Types of Fitness Facilities (+) *** | Density of Fitness Facilities (+) ** | / |

| Jogging | Number of Entrances (+) ** | Spatial Shape (-) ** | Spatial Scale (+) ** |

| Sitting | Seating Area (+) *** | Number of Fitness Facilities(+)*** | Degree of Green Enclosure (+) *** |

| Walking | Spatial Scale (+) ** | Spatial Shape (-) ** | Population Served (-) ** |

| Standing | Spatial Shape (+) ** | Spatial Scale (-) ** | / |

| Chess and Cards | Spatial Scale (-) *** | Seating Area (+) ** | Number of Chess and Card Tables (+) ** |

** indicates that two models provide the same interpretation for the importance ranking; *** indicates that all three models provide the same interpretation for the importance ranking; (/) indicates that none of the three models agree on the interpretation, hence the indicator is not marked; (+) signifies that the indicator has a promoting effect on behavior; (-) signifies that the indicator has an inhibiting effect on behavior.

Results of nonlinear relationship

To further explore the complex relationships between spatial feature indicators and behavior, Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) plots and Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs or PD plots) were created based on the spatial feature indicators deemed important by machine learning (as summarized in Table 5).

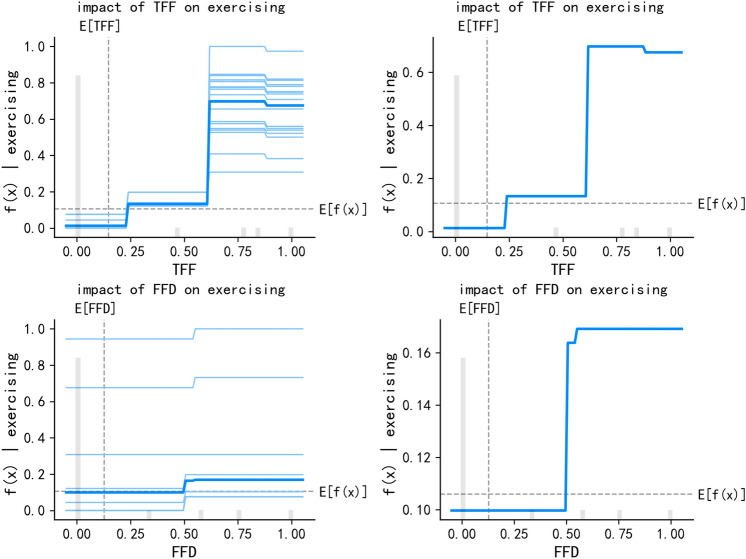

Figures 13, 14 and 15 respectively display the ICE and PD plots for the spatial feature indicators (with the same feature variables extracted, same below) associated with exercising behavior under the RF, GBDT, and XGBoost models (the left side is the ICE plot, and the right side is the PD plot, same below). When comparing different models, there will be certain differences in the details during the increasing or decreasing process. However, the overall trends, such as the increasing or decreasing trends and the thresholds of change, remain consistent (same below).

Fig. 13.

ICE Plots and PDP plots of exercise behavior in relation to TFF (types of fitness facilities) and FFD (fitness facility density) in the RF model.

Fig. 14.

ICE Plots and PDP plots of exercise behavior in relation to TFF (types of fitness facilities) and FFD (fitness facility density) in the GBDT Model.

Fig. 15.

ICE Plots and PDP plots of exercise behavior in relation to TFF (types of fitness facilities) in the XGBoost model.

Integrating the results from the three models, the following conclusions can be drawn: The type of fitness equipment shows a stepwise increasing trend with exercising behavior, accompanied by a threshold effect, where the exercising behavior remains constant when the type of fitness equipment exceeds 0.75; the influence of fitness facility density on exercising behavior also exhibits a threshold effect across different models, with different manifestations in the details of the middle increasing process, where the RF model shows a stepwise increase, while the GBDT model shows a linear increase.

Figures 16 and 17 respectively display the ICE plots PD plots for the spatial feature indicators associated with jogging behavior under the RF and GBDT models (the XGBoost model is not analyzed due to different importance rankings for the number of entrances, spatial shape, and spatial scale).

Fig. 16.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for jogging behavior in relation to NE (Number of Entrances), SSP (Spatial Shape), and SSL (Spatial Scale) in the RF Model.

Fig. 17.

ICE Plots and PDP plots of jogging behavior in relation to NE (Number of Entrances) and SSP (Spatial Shape) in the GBDT Model.

Integrating the results from the three models, the following conclusions can be summarized: The number of entrances exhibits an accelerating stepwise increasing trend for the influence on jogging, with a threshold effect, where it remains constant after reaching around 0.9 and no longer changes; the spatial shape (the more elongated the space, the smaller the value) has a decelerating decreasing trend for jogging, with a threshold effect, where it remains constant after reaching around 0.25 and no longer changes; the spatial scale shows a stepwise increasing trend for jogging, with a threshold effect, and remains constant after reaching around 0.75 and no longer changes.

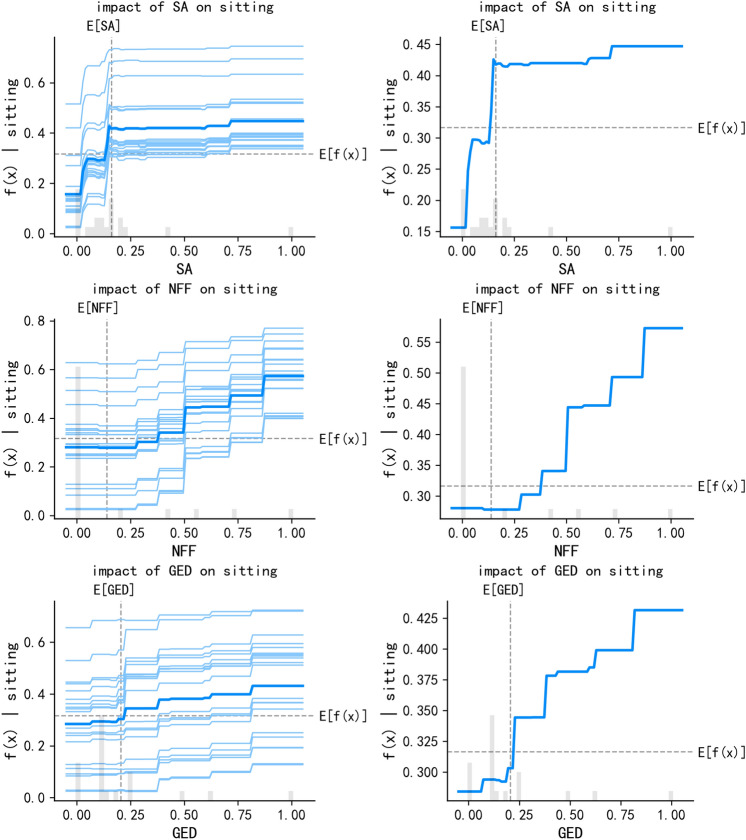

Figures 18, 19 and 20 respectively display the ICE plots and PD plots for the spatial feature indicators associated with sitting behavior under the RF, GBDT, and XGBoost models.

Fig. 18.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for sitting behavior in relation to SA (Seating Area), NFF (Number of Fitness Facilities), and GED (Green Enclosure Degree) in the RF Model.

Fig. 19.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for sitting behavior in relation to SA (Seating Area), NFF (Number of Fitness Facilities), and GED (Green Enclosure Degree) in the GBDT Model.

Fig. 20.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for sitting behavior with respect to SA (Seating Area), NFF (Number of Fitness Facilities) and GED (Green Enclosure Degree) in the XGBoost model.

Synthesizing the results from the three models, the following conclusions can be drawn: The seating area exhibits a distinct nonlinear relationship and threshold effect on sitting behavior, initially increasing sharply with some fluctuations, then gradually rising until it stabilizes around the value of 0.75 without further change. In contrast, the number of fitness facilities and the degree of green enclosure influence sitting behavior with a stepwise increasing trend, without exhibiting a nonlinear relationship.

Figures 21, 22 and 23 respectively display the ICE plots and PD plots for the spatial feature indicators associated with walking behavior under the RF, GBDT, and XGBoost models.

Fig. 21.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for walking behavior in relation to SSL (Spatial Scale), SSP (Spatial Shape), and PS (Population Served) in the RF model.

Fig. 22.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for walking behavior in relation to SSL (Spatial Scale) and SSP (Spatial Shape) in the GBDT model.

Fig. 23.

ICE Plot and PDP plots for walking behavior in relation to SSL (Spatial Scale) and PS (Population Served) in the XGBoost model.

Upon synthesizing the results from the three models, the following conclusions can be summarized: Spatial scale exhibits a nonlinear relationship and threshold effect on walking behavior, showing an initial accelerating monotonic increase followed by a decelerating monotonic increase, until it reaches a maximum value after which it no longer changes. The spatial shape has a nonlinear relationship and threshold effect on walking, with a decelerating monotonic decrease before the value of 0.35, followed by a plateau phase, and then a phase of monotonic increase. The number of people served shows a trend for walking behavior that starts off stable, then monotonically decreases, and finally levels off.

Figures 24, 25 and 26 respectively display the ICE plots and PD plots for the spatial feature indicators associated with standing behavior under the RF, GBDT, and XGBoost models.

Fig. 24.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for standing behavior in relation to SSP (Spatial Shape) and SSL (Spatial Scale) in the RF model.

Fig. 25.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for standing behavior in relation to SSP (Spatial Shape) and SSL (Spatial Scale) in the GBDT model.

Fig. 26.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for standing behavior in relation to SSP (Spatial Shape) and SSL (Spatial Scale) in the XGBoost model.

Upon synthesizing the results from the three models, the following conclusions can be summarized: The spatial shape exhibits a clear nonlinear correlation and threshold effect on standing behavior, characterized by an initial slight fluctuating decrease followed by a sharp increase. The spatial scale shows a decreasing trend for standing behavior, after which it remains constant.

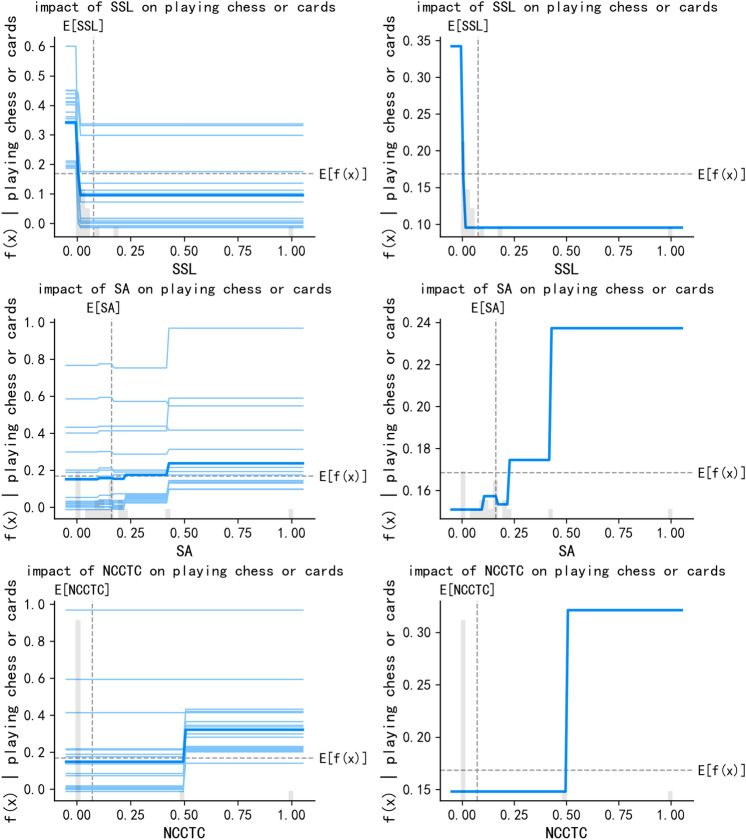

Figures 27, 28 and 29 respectively display the ICE plots and PD plots for the spatial feature indicators associated with chess and card playing behavior under the RF, GBDT, and XGBoost models.

Fig. 27.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for chess and card playing behavior in relation to SSL (Spatial Scale), SA (Seating Area), and NCCTC (Number of Chess and Card Tables and Chairs) in the RF Model.

Fig. 28.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for chess and card playing behavior in relation to SSL (Spatial Scale), SA (Seating Area), and NCCTC (Number of Chess and Card Tables and Chairs) in the GBDT Model.

Fig. 29.

ICE Plots and PDP plots for chess and card playing behavior in relation to the SSL (Spatial Scale), SA (Seating Area), and NCCTC (Number of Chess and Card Tables and Chairs) in the XGBoost Model.

Upon synthesizing the results from the three models, the following conclusions can be summarized: The spatial scale has an initial decreasing effect on chess and card playing behavior, maintaining a certain linear relationship until it reaches its minimum value and then remains constant; the sitting area has a promotional effect on chess and card playing behavior, increasing until it reaches a maximum value after which it no longer changes; the number of chess and card tables also has a promotional effect on chess and card playing behavior, increasing until it reaches a maximum value and then remains constant.

Discussions

Integrating ICE and PD plots reveals nonlinear relationships, monotonic trends, and critical limits in how spatial features influence behaviors. The relationships between spatial indicators and behaviors are summarized as follows:

For jogging behavior, significant indicators are entrance count (+), spatial shape (-), and spatial scale (+). Entrance count shows an accelerating increase, leveling off at a certain limit. Fewer entrances force elderly users to take considerable detours. More entrances rapidly reduce detours, but beyond a certain point, further additions have negligible impact. Spatial shape (more elongated means a smaller value) displays a decelerating decrease, reaching a critical limit. Jogging thrives in pathway spaces with consistent width. Compact shapes enhance pathway characteristics, favoring jogging. Squarer layouts diminish pathway clarity, reducing jogging until it ceases. Spatial scale shows an increasing trend, plateauing when exceeding elderly physical limits. Maximum scale may surpass jogging distance capacity, halting further behavioral escalation.

For sitting behavior, significant indicators are sitting area (+), fitness facility count (+), and green enclosure (+). Sitting area exhibits a nonlinear pattern: a sharp initial surge, followed by a gradual plateau. This reflects the elderly’s need for frequent rest due to diminished physical capacity. Expanding seating immediately increases sitting behavior, but once demand is met, frequency stabilizes. Fitness facility count, often overlooked, promotes sitting, as elderly seek rest post-exertion. Green enclosure shows a linear trend, peaking at a limit, enhancing leisurely qualities and fostering a serene environment that entices the elderly to sit and relax.

For walking behavior, significant indicators are spatial scale (+), spatial shape (-/+), and number of people served (+). Spatial scale shows an initial rapid increase, then decelerates, reaching a plateau. Unlike jogging, walking is less strenuous and supports varied pursuits, requiring ample space for elderly walking distances. Expanded scale allows greater distances, appealing to the elderly. At maximum scale, walking needs are fulfilled, showing a limit. Spatial shape (more elongated means smaller value) first inhibits, then promotes walking. Elongated spaces enhance walking function, while squarer spaces blur it. Leisure-oriented square spaces, however, revive walking behavior, linked to the space’s evolving nature. Number of people served (elderly within 10 minutes) positively impacts walking, as more individuals translate to greater walking needs, stimulating activity.

For standing behavior, significant indicators are spatial shape (+) and spatial scale (+). Spatial shape initially remains constant, then fluctuates and decreases, before sharply increasing. Pathway-like spaces are unsuitable for standing due to their movement focus. As shapes become more leisure-oriented, standing decreases, possibly due to a preference for sitting. Certain square spaces, however, rekindle standing behavior.

For chess and card playing behavior, significant indicators are spatial scale (-), sitting area (+), and chess/card table count (+). Spatial scale shows a declining trend, reaching a limit. The elderly prefer smaller, intimate spaces for these sedentary pursuits, favoring tranquility and requiring less extensive dimensions. Larger scales suit active pursuits like exercise. Sitting area exerts a strong positive influence, peaking at a limit. Many elderly use existing seats for portable games, substituting for dedicated tables. Expanded seating significantly satisfies their needs, but at maximum capacity, needs are fulfilled. Chess/card table count positively impacts play, plateauing at a saturation point. As essential facilities, tables enhance play propensity until elderly needs are fully met, with no further activity increase.

The discussion on the impact mechanisms of various spatial feature indicators on different types of behavior is summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Nonlinear relationships between spatial feature indicators and behavioral types.

| Behavioral Type | Spatial Feature Indicator | Overall Impact | Threshold Effect | Marginal Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | Types of Fitness Facilities | + | Yes | / |

| Density of Fitness Facilities | + | Yes | / | |

| Jogging | Number of Entrances | + | Yes | Initially increasing then decreasing |

| Spatial Shape | - | Yes | Decreasing | |

| Spatial Scale | + | Yes | / | |

| Sitting | Seating Area | +

|

Yes | Initially increasing then decreasing |

| Number of Fitness Facilities | + | Yes | No significant effect | |

| Degree of Green Enclosure | + | Yes | No significant effect | |

| Walking | Spatial Scale | + | Yes | Initially increasing then decreasing |

| Spatial Shape | +

|

/ | No significant effect | |

| Number of People Served | -

|

Yes | No significant effect | |

| Standing | Spatial Shape | +

|

Yes | / |

| Spatial Scale | - | Yes | Decreasing | |

| Chess and Cards | Spatial Scale | - | Yes | Decreasing |

| Seating Area | + | Yes | Initially increasing then decreasing | |

| Number of Chess and Card Tables | + | Yes | Initially increasing then decreasing |

+ indicates a promoting effect, - indicates an inhibiting effect,  indicates fluctuation, Yes indicates the presence of a threshold effect, and / in the Marginal Effect column indicates no significant effect or uncertainty.

indicates fluctuation, Yes indicates the presence of a threshold effect, and / in the Marginal Effect column indicates no significant effect or uncertainty.

Overall, the interplay between spatial feature indicators and behaviors is characterized by nonlinear relationships and threshold effects to varying extents. Patterns that positively influence behavior typically exhibit a deceleration in the rate of increase until they plateau; in contrast, those with a negative impact tend to demonstrate a deceleration in the rate of decrease until they stabilize. Specifically, when the values of spatial feature indicators fall within a lower range, they exhibit greater sensitivity to behavior, as evidenced by the steepness of the curve. As these values ascend, their sensitivity to influencing behavior diminishes until it plateaus. This phenomenon aligns with the findings of numerous scholars who have investigated the influence of the built environment on behavior33, suggesting that the impact of the built environment on behavior attenuates as the marginal effects wane with sustained increments or decrements in value.

This study has certain limitations: due to video data collection being restricted to a single time period, it failed to capture the dynamic changes in older people’ behaviors under varying factors such as seasons and weather, which may affect the comprehensive characterization of behavioral patterns by the model. Additionally, the interaction effects of multiple spatial variables on behavior were not fully considered in the correlation mechanisms, limiting their explanatory power. Future research could expand the temporal coverage through multi-period and cross-seasonal data collection to further explore the synergistic mechanisms of spatial variables, providing more reliable evidence for optimizing age-friendly spatial design.

Conclusion and prospects

In this study, we systematically categorized the daily behaviors of the elderly in outdoor public spaces into six distinct types: exercise, jogging, sitting, walking, standing, and playing chess and cards. Employing computer vision-based behavior detection algorithms, we detected behaviors within community outdoor public spaces to compile data on these six behavior types. We identified spatial variables that influence the outdoor activities of the elderly and categorized them into spatial indicators, greening indicators, functional facility indicators, and accessibility indicators, thereby establishing a spatial quantification model.

Subsequently, the study delved into the association mechanism between behavior types and spatial feature indicators, utilizing interpretable machine learning techniques to analyze nonlinear relationships. Key spatial feature indicators and their influence on behavior were ultimately identified, leading to the proposal of optimization strategies for community outdoor public spaces to effectively accommodate the behavioral needs of the elderly. The findings are summarized as follows:

(1) The behavioral activities of the elderly in community outdoor public spaces display temporal and spatial variations. Through the identification and analysis of these activities, distinct temporal patterns and spatial differences in activity types were observed. Temporal regularity is primarily characterized by specific behaviors occurring within concentrated and fixed time frames: jogging peaks in the morning with the shortest duration; chess and card playing peaks in the afternoon with the longest duration; sitting activities are spread across various spaces with the most extensive time span; walking activities peak in the afternoon with a significant duration; standing activities show no clear temporal concentration and are evenly distributed. Spatial differences imply that various activity types have distinct spatial distributions, leading to insights regarding the “compatibility” of behaviors in different spaces and the most suitable activities for each space. Compatibility insights: standing and sitting are deemed the most compatible. Suitability insights: square spaces are best suited for standing, leisure spaces for sitting and playing chess and cards, pathway spaces for walking, and fitness spaces for exercise.

(2) Spatial feature indicators influencing the behavioral activities of the elderly encompass 16 elements, such as spatial scale, spatial shape, and the degree of green enclosure. By applying three machine learning algorithms—random forest, gradient boosting decision tree, and extreme gradient boosting—we calculated the nonlinear relationships between “behavior and space” separately. Interpretable machine learning models were employed to ascertain the importance ranking of spatial variables affecting behavior. These variables include the type and density of fitness facilities influencing exercise, the number of entrances, spatial shape, and spatial scale affecting jogging, the seating area affecting sitting, spatial scale affecting walking, and spatial scale affecting chess and card playing.

By integrating the insights from the three machine learning models, the key indicators impacting the outdoor activities of the elderly were determined to include a total of 16 items, such as spatial scale, spatial shape, and the degree of green enclosure.

In spatial design, designers can adjust relevant spatial indicators based on the overall impact, threshold effects, and marginal effects of 16 spatial indicators on behavior. For example, in designing fitness spaces, emphasis should be placed on improving the diversity and richness of fitness facilities. For optimizing spaces for jogging and walking, the spatial scale of jogging areas should be appropriately controlled, and the number of entrances can be increased to provide convenient and quick access. For spaces designed for sitting, the seating area and greenery enclosure can be enhanced. For spaces intended for chess/card games, an appropriate spatial scale should be designed, with an increased number of tables and chairs to offer more seating options, reduce waiting time, and allow more older people to participate in such activities simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the Beijing Municipal Office of Philosophy and Social Science Planning [24SRB016], and the Yuxiu Innovation Project of NCUT (Project No.2024NCUTYXCX115).

Author contributions

Lei Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review and Editing, Funding Acquisition; Wenqi He: Investigation, Software, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization; Shan Wu: Data Collection, Data Analysis; Bo Zhang: Funding Acquisition; Xiaorui Zhang and Hu Yin: Supervision, Validation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to their necessity for future research but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics and consent

All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Chess of North China University of Technology (NCUT). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects participating in the study. This study strictly adhered to ethical principles in the collection and processing of video data involving older people, ensuring the protection of participants’ privacy and rights. The specific ethical measures are as follows: (1) Anonymization: Data collection occurred in public spaces without identifying or tracking specific individuals (e.g., faces or names), complying with ethical exemptions for non-invasive observation in public settings. To further safeguard privacy, all videos underwent anonymization processing to ensure individuals could not be traced. (2) Restricted Research Purpose: The study collected only the behavioral data necessary for research, used exclusively for extracting behavioral data through computer vision behavior detection algorithms, and not for any other purposes. (3) Ethical Review: The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of North China University of Technology. (4) Data Security: Video data were accessible only to the research team, with external sharing of video clips strictly prohibited. In accordance with ethics committee requirements, all data will be destroyed within six months after the study’s completion, in compliance with data protection regulations.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lei Wang, Email: wlei@ncut.edu.cn.

Bo Zhang, Email: abaofoc@ncut.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Han, W.-J. & Shibusawa, T. Trajectory of physical health, cognitive status, and psychological well-being among Chinese elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.60, 168–177. 10.1016/j.archger.2014.09.001 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jian, M., Su, D., Du, Y., Cao, J. & Li, C. Exploring the influence of walking on quality of life among older adults: Case study in Hohhot. China J. Transp. Health32, 101684. 10.1016/j.jth.2023.101684 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcos-Pardo, P. J., Espeso-García, A., Abelleira-Lamela, T. & Machado, D. R. L. Optimizing outdoor fitness equipment training for older adults: Benefits and future directions for healthy aging. Exp. Gerontol.181, 112279. 10.1016/j.exger.2023.112279 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma, J., Zhao, S. & Li, W. Threshold effect of unmet walking needs on quality of life for seniors. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ.124, 103894. 10.1016/j.trd.2023.103894 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni, H.-J. et al. Effects of Exercise Programs in older adults with Muscle Wasting: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.99, 104605. 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104605 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan, Z. et al. Reduced social activities and networks, but not social support, are associated with cognitive decline among older chinese adults: A prospective study. Soc. Sci. Med.289, 114423. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114423 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hikichi, H., Kondo, K., Takeda, T. & Kawachi, I. Social interaction and cognitive decline: Results of a 7-year community intervention. Alzheimer’s Dement.: Transl. Res. Clin. Interv.3, 23–32. 10.1016/j.trci.2016.11.003 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu, W. et al. Cognitive decline trajectories and influencing factors in China: A non-normal growth mixture model analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.95, 104381. 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104381 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, H. X. & Xie, Q. Y. Research on health risks to the elderly in residential spaces from the perspective of behavioral safety: theoretical methods, risk formation rules, and assessment and prevention. City Planning Review46, 77–89 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motomura, M. et al. Associations of public open space attributes with active and sedentary behaviors in dense urban areas: A systematic review of observational studies. Health Place75, 102816. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2022.102816 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirzaei, E., Kheyroddin, R., Behzadfar, M. & Mignot, D. Utilitarian and hedonic walking: Examining the impact of the built environment on walking behavior. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev.10, 20. 10.1186/s12544-018-0292-x (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong, R., Zhao, H. & Huang, Y. Spatial heterogeneity in the effects of built environments on walking distance for the elderly living in a mountainous city. Travel Behav. Soc.34, 100693. 10.1016/j.tbs.2023.100693 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salthouse, T. A. Trajectories of normal cognitive aging. Psychol. Aging34, 17–24. 10.1037/pag0000288 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brush, C. et al. Does aerobic fitness moderate age-related cognitive slowing? Evidence from the P3 and lateralized readiness potentials. Int. J. Psychophysiol.155, 63–71. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.05.007 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatangelo, T., Muollo, V., Ghiotto, L., Schena, F. & Rossi, A. P. Exploring the association between handgrip, lower limb muscle strength, and physical function in older adults: A narrative review. Exp. Gerontol.167, 111902. 10.1016/j.exger.2022.111902 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun, S., Yu, Z. & An, S. Patterns of physical and mental co-occurring developmental health among Chinese elderly: A multidimensional growth mixture model analysis. SSM - Popul. Health25, 101584. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101584 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, Y. et al. Loneliness, social isolation, depression and anxiety among the elderly in Shanghai: Findings from a longitudinal study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.110, 104980. 10.1016/j.archger.2023.104980 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.YANG, X. et al. A Study on the relationship between residents’ spontaneous construction behavior and public space elements in the aging old community: A case study of Zhuguang community in Guangzhou. Urban Development Studies30 (2023).

- 19.Zhang, R., Jiang, X., He, Y. & Miquel, M. C. Research on the historical types of small public space from the perspective of urban morphology: Taking Barcelona as an example. Urban Planning International 1–14, 10.19830/j.upi.2022.603 (2023).

- 20.Wei, Y. & Forsyth, D. Learning the behavior of users in a public space through video tracking. In 2005 Seventh IEEE Workshops on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV/MOTION’05) - Volume 1, 370–377, 10.1109/ACVMOT.2005.67 (IEEE, Breckenridge, CO, 2005).

- 21.Hou, J., Chen, L., Zhang, E., Jia, H. & Long, Y. Quantifying the usage of small public spaces using deep convolutional neural network. PLOS ONE15, e0239390. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239390 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang, S., Leng, H., Yuan, Q., Wang, B. & Yuan, C. How does weather and climate affect pedestrian walking speed during cool and cold seasons in severely cold areas?. Build. Environ.175, 106811. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106811 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiao, D. & Fei, T. Pedestrian walking speed monitoring at street scale by an in-flight drone. PeerJ Comput. Sci.9, e1226. 10.7717/peerj-cs.1226 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong, P.K.-Y., Luo, H., Wang, M., Leung, P. H. & Cheng, J. C. Recognition of pedestrian trajectories and attributes with computer vision and deep learning techniques. Adv. Eng. Inform.49, 101356. 10.1016/j.aei.2021.101356 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, L. & He, W. Analysis of community outdoor public spaces based on computer vision behavior detection algorithm. Appl. Sci.13, 10922. 10.3390/app131910922 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, L. & He, W. A study of behavioural characteristics of the elderly based on computer vision technology. International Journal of Urban Sciences 1–31 (2025).

- 27.Sun, X., Wang, L., Wang, F. & Soltani, S. Behaviors of seniors and impact of spatial form in small-scale public spaces in Chinese old city zones. Cities107, 102894. 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102894 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, Z., Kemperman, A. & Timmermans, H. Correlates of frequency of outdoor activities of older adults: Empirical evidence from Dalian. China. Travel Behav. Soc.22, 108–116. 10.1016/j.tbs.2020.09.003 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou, Y. et al. Demand, mobility, and constraints: Exploring travel behaviors and mode choices of older adults using a facility-based framework. J. Transp. Geogr.102, 103368. 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103368 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perchoux, C. et al. Does the built environment influence location- and trip-based sedentary behaviors? evidence from a gps-based activity space approach of neighborhood effects on older adults. Environ. Int.180, 108184. 10.1016/j.envint.2023.108184 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems30 (2017).

- 32.Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell.2, 56–67. 10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, J., Xiao, L., Zhou, J., Guo, Y. & Yang, L. Non-linear relationships between the built environment and walking to school: Applying extreme gradient boosting method. Prog Geogr41, 251–63 (2022). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to their necessity for future research but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.