Abstract

Hyperosmolar therapy, specifically the use of mannitol, has been employed to improve brain relaxation, but mannitol use may cause hypovolemia and electrolyte imbalance. Given these risks, hypertonic saline was introduced as an alternative; however, data on its efficacy and safety are limited. Researchers conducted a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Sixty-six patients with supratentorial or posterior fossa brain tumours undergoing craniotomy were randomized into two groups. Group M received 20% mannitol at 3 ml/kg, and Group H received 3% hypertonic saline at the same dose. These solutions were administered before dural opening. Two masked neurosurgeons immediately assessed the four-point brain relaxation score by direct visual and tactile evaluation after dural opening. Both groups showed no significant difference in brain relaxation scores (p = 0.543). There was no significant difference in haemodynamic change, fluid replacement, or serum osmolarity between groups; however, urine output was greater in the mannitol group (p = 0.003). Additionally, postoperative neurological outcomes and one-month mortality rates were similar. These findings suggest 3% hypertonic saline can be considered an alternative to mannitol for improving brain relaxation during craniotomy, as it is equally effective with less urine output.

Keywords: Brain relaxation, Mannitol, Hypertonic saline, Hyperosmolar therapy

Subject terms: Medical research, Neurology

Introduction

A tight brain is a common, nuanced problem that can occur during a craniotomy for removing brain tumours. This leads to difficulty in accessing the tumour due to a narrow surgical field. Therefore, the administration of hyperosmolar solutions has been utilized to enhance brain relaxation. Hyperosmolar solutions rapidly increase blood osmolarity, which induces the movement of water out of brain tissue. This osmotic effect results in a reduction in brain water content and overall brain volume, which leads to a decrease in intracranial pressure1,2. By facilitating these physiological changes, hyperosmolar solutions play a significant role in the management of conditions characterized by elevated intracranial pressure. Additionally, the reduction in brain bulk enhances surgical exposure. This improves the visibility and accessibility of the surgical site.

Hyperosmotic solutions, including hypertonic saline and mannitol, are widely used in neurosurgery for brain relaxation. Hypertonic saline solutions are used in various concentrations, including 3%, 5%, and 10%. These hyperosmolar agents operate on the principle of osmosis, creating an osmotic gradient that draws free water out of brain tissue, thereby decreasing intracranial pressure. Hypertonic saline is indicated in several clinical conditions, including traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and as a preventive measure during preoperative preparation for tumour resection via craniotomy. On the other hand, mannitol, commonly administered as a 20% solution, acts as an osmotic diuretic that increases plasma osmolality and promotes the movement of water from the brain into the intravascular space. This mechanism is particularly beneficial in the management of cerebral edema associated with various neurological conditions, including malignant brain tumors and acute neurological injuries. However, mannitol is restricted in cases of kidney disease, heart failure, and pulmonary congestion because of its potential to cause large fluid shifts, which can precipitate heart failure, acute kidney failure, and electrolyte imbalances3,4. Hypertonic saline, particularly 3%, has been commonly used as an alternative to promote brain relaxation but there is a lack of high-quality evidence to support its efficacy and safety. This lack of high-quality evidence raises concerns over its use. Furthermore, while hyperosmotic solutions have been investigated for reducing brain tightness in supratentorial pathologies5–7there is a lack of data regarding their use in posterior fossa pathologies. In addition, previous studies6,7 have utilized varying doses of mannitol and hypertonic saline, complicated direct comparisons and potentially introducing dose-related bias. To address this limitation, our study compared 3% hypertonic saline and mannitol using an equivalent dose of 3 ml/kg—an approach designed to represent the minimal effective volume required for brain relaxation while minimizing the risk of complications. This standardized dosing strategy aims to provide a more rigorous and clinically relevant evaluation of the comparative efficacy of these two agents.

Therefore, this study aims to compare the effectiveness of 3% hypertonic saline versus 20% mannitol at the same volume in reducing brain tightness in patients undergoing elective craniotomy for brain tumours, both in the supratentorial and posterior fossa (infratentorial). Additionally, the debate over the optimal dose of hyperosmotic solutions—either low or high—remains contentious due to insufficient evidence. Therefore, our study adopted a minimum effective volume of 3 ml/kg to minimize the risk of complications. This approach aims to balance efficacy with safety by addressing the need for cautious administration while ensuring adequate therapeutic effects.

Materials and methods

The prospective randomized, double-blind controlled trial was conducted between December 2021 and October 2022. Recruitment included patients between the ages of 18 and 65 who presented with supratentorial or posterior fossa brain tumours with scheduled craniotomy for tumour resection. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients with clinical evidence of increased intracranial pressure, including persistent morning headache, headache exacerbated by bending over, presenting papilledema, or delayed responses. Additional criteria included an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification of I to III and a high Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. The exclusion criteria included a previous history of allergy to mannitol or hypertonic saline, a history of seizures, receipt of hyperosmolar therapy or diuretics within the last 24 h, a body temperature exceeding 37.8 °C with hyponatremia (< 130 mmol/L) or hypernatremia (> 150 mmol/L).

Patients were enrolled and asked for written informed consent one day before surgery. Patients were randomly allocated into two groups via block randomization with a computer generating multiple block sizes of 4, 6, and 8. The patients were assigned to either Group M, which received intravenous 20% mannitol at a dose of 3 ml/kg, or Group H, which received intravenous 3% hypertonic saline at the same dose in concealed syringes. These hypertonic solutions were administered via an infusion pump 15 min before dural opening. The neurosurgeons and patients were blinded to the group assignments.

A sample size of 33 patients per group was calculated as appropriate with a 95% confidence interval and 2% error (allowing for a 10% dropout rate). A minimal clinically important difference of 0.15 was observed, and the proportion of good brain relaxation was estimated from the study of Hernández-Palazón et al.5; the 3% hypertonic saline group had a value of 0.83, whereas the 20% mannitol group had a value of 0.90.

Patients in both groups were anaesthetized via the same protocol. Premedication with fentanyl (1–2 mcg/kg) was prescribed. Propofol (1–2 mg/kg) and cisatracurium (0.15 mg/kg) were administered to induce anaesthesia. The TIVA technique with target-controlled infusion of propofol and cisatracurium (1–2 mcg/kg) was used in the maintenance phase of general anaesthesia to achieve the targeted BIS values of 40–60. The ventilator settings included a tidal volume of 6–8 ml/kg, a PEEP of 5 cmH2O, and an RR of 10–20 tmp to maintain PaCO2 at 30–35 mmHg and a Paw below 30 cmH2O. Haemodynamics, including electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, pulse pressure variation (PPV), heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP), were monitored. Fluid administration was standardized via early goal-directed therapy. The degree of brain relaxation was evaluated by masked the two neurosurgeons via direct visual and tactile assessments immediately after dura opening. The interrater reliability of neurosurgeons was tested via Cohen’s kappa coefficient, which exceeded 0.8 in the pilot study. Grading8 was classified as perfectly relaxed (grade I), satisfactorily relaxed (grade II), firm bulging (grade III), or bulging (grade IV). However, if the degree of brain relaxation was greater than Grade II, patients received rescue management, including internal jugular vein compression, bronchospasm, the BIS waveform, and blood pressure. The rescue management of bronchospasm included prescribing a bronchodilator and keeping the PIP lower than 30 mmH2O while properly adjusting the ventilator. The range of the BIS from 40 to 60 was controlled with propofol. Additionally, antiepileptic drugs were administered when epileptic BIS waves were present. Antihypertensive medication was prescribed when the blood pressure exceeded 20% of the baseline value. If the brain did not relax following initial rescue management, hyperventilation and a second dose of hyperosmolar solution were administered per the protocol in each group. Finally, if there was no brain relaxation response, intravenous furosemide was considered. At the end of the surgery, neuromuscular blockade reversal was facilitated via the administration of 2.5 mg neostigmine and 1.2 mg atropine to ensure sufficient recovery.

Bottom of form

Outcome measurement

The primary outcome was the incidence of good brain relaxation grades, defined as grades I or II of the four-point brain relaxation grading scale8.

Haemodynamic parameters were recorded for 105 min after the administration of hyperosmolar solutions. Serum osmolarity and sodium levels were assessed at the T45 and T105 timepoints. Secondary outcomes evaluated included total intraoperative fluid replacement, urine output, incidence of rescue interventions, postoperative neurological outcomes, length of ICU stay (LOICU), length of hospital stay (LOS), and one-month postoperative mortality rate. Furthermore, postoperative neurological function was assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) at 24 h after surgery. Patients were classified into three categories based on their GCS scores: Good (score of 13–15), Moderate (score of 9–12), and Severe (score < 9), providing a standardized measure of early postoperative neurological status.

Data analyses

Descriptive data are presented as percentages, means ± SDs, and medians (IQRs). Categorical data were analysed with the chi-square test for nonparametric distributions, and Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse normally distributed categorical data. For continuous data, nonparametric data were analysed with the Mann‒Whitney U test, and normally distributed data were analysed with the independent t test. A mixed model regression was used to analyse repetitive data. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the data were analysed with STATA (v 10.1: Stata Corp. 2015, Texas, USA).

Ethical review

The study was reviewed and approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee of Khon Kaen University (HE641396). The study was also registered with the Thai Clinical Trial Registry (TCTR20211027001) (27/10/2021). Informed consent was obtained from all patients following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

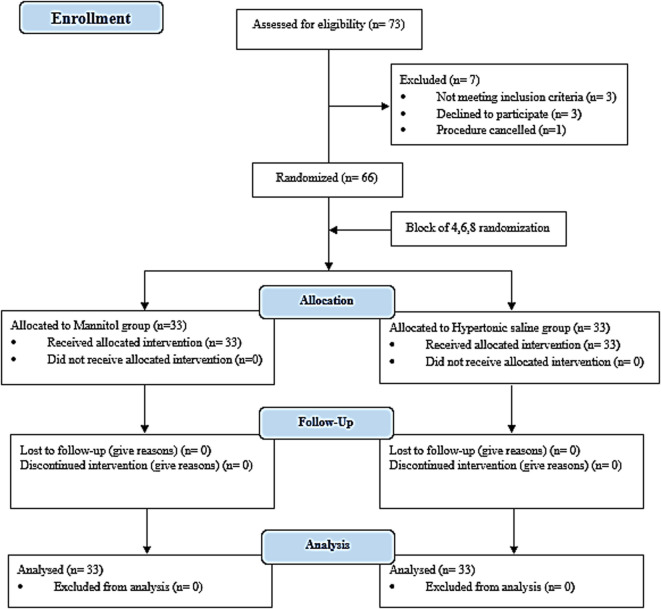

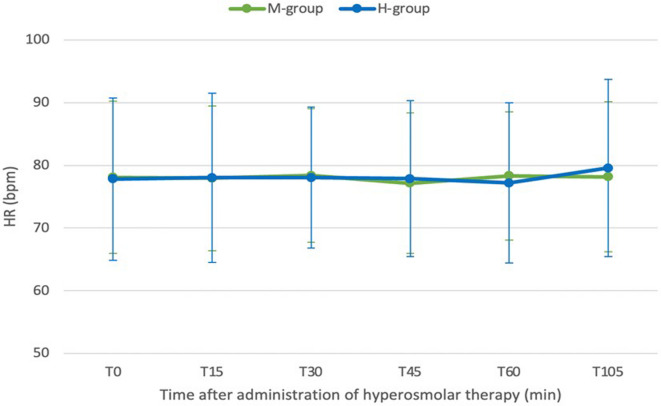

Sixty-six patients, 10 males and 56 females (mean age = 48.1 ± 10.5 years) were included in this study. The patients were allocated equally to both groups (Fig. 1). There were no subjects loss to follow-up at the end of the study. The demographic data were similar between the two groups. In our cohort, meningioma was the most common pathological diagnosis. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding tumour subtype or the proportion of convexity tumours (Table 1). After the administration of the hypertonic solutions, the urine output of the M group was significantly greater than that of the H group (p = 0.003). Moreover, the blood Na+ level in the M group seemed to have plateaued, whereas the blood Na+ level in the H group tended to increase. At the T45 and T105 timepoints, the blood Na+ level was significantly greater in the H group as compared to the M group (Table 2). All the haemodynamic parameters, including the mean MAP, HR, and PPV, were comparable between the two groups, as shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the flow of patients through each stage of the randomized controlled trial.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Characteristics | M group (n = 33) | H group (n = 33) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female, n (%) | 6 (18.2)/27 (81.8) | 4(12.1)/29 (84.9) | 0.49 |

| Age, yr, n (%) | |||

| • 18–30 | 2 (6.1) | 2 (6.1) | 0.06 |

| • 31–40 | 1 (3.0) | 5 (15.2) | |

| • 41–50 | 13 (39.4) | 15 (45.5) | |

| • 51–60 | 14 (42.4) | 9 (27.3) | |

| • 61–65 | 3 (9.1) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Weight, Kg, mean (SD) | 62.8 (10.8) | 58.8 (9.5) | 0.11 |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 156 (7) | 156 (6) | 0.61 |

| BMI, kg/m2 mean (SD) | 25.9 (3.9) | 24.1 (4.1) | 0.07 |

| ASA physical status, n (%) | |||

| • I | 7 (21.2) | 12 (36.4) | 0.13 |

| • II | 25 (75.8) | 17 (51.5) | |

| • III | 1 (3.0) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Signs of increasing ICP, n (%) | 18 (54.6) | 16 (48.5) | 0.62 |

| Preoperative steroids using, n (%) | 23 (69.7) | 20 (60.6) | 0.44 |

| Intraoperative positioning, n (%) | |||

| • Supine | 19 (57.6) | 25 (75.8) | 0.20 |

| • Prone | 8 (24.2) | 3 (9.1) | |

| • Lateral decubitus | 6 (18.2) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||

| • Supratentorial | 16 (48.5) | 23 (69.7) | 0.08 |

| • Posterior fossa | 17 (51.5) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Diagnosis., n (%) | |||

| • Meningioma | 20 (60.6) | 19 (57.6) | 0.70 |

| • WHO I | • 14 (42.4) | • 15 (45.5) | |

| • WHO II | • 5 (15.2) | • 4 (12.1) | |

| • WHO III | • 1 (3.0) | • 0 | |

| • Schwannoma | 6 (18.2) | 6 (18.2) | |

| • Glioma | 0 | 4 (12.1) | |

| • Metastasis | 2 (6.1) | 1 (3.0) | |

| • Other | 5 (15.2) | 2 (6.0) | |

| Tumor size, cm3 median (IQR) | 17.4 (7.1, 37.3) | 9.8 (5.8, 34) | 0.37 |

| Convexity tumor | 15 (45.5) | 13 (39.4) | 0.62 |

| Imaging finding, n (%) | |||

| • Perilesional edema | 10 (30.3) | 7 (21.2) | 0.40 |

| • Generalized edema | 3 (9.1) | 4 (12.1) | >0.99 |

| • Midline shift | 7 (21.2) | 5 (15.2) | 0.52 |

| • Herniation | 5 (15.2) | 5 (15.2) | >0.99 |

| • Obstructive hydrocephalus | 3 (9.1) | 5 (15.2) | 0.71 |

Table 2.

Anaesthetic and surgical data.

| Data | M group (n = 33) | H group (n = 33) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time, min, median (IQR) | 180 (150, 240) | 210 (165, 270) | 0.18 |

| TD, mins, median (IQR) | 55 (45, 70) | 65 (53, 95) | 0.11 |

| Blood loss, ml, median (IQR) | 500 (300, 850) | 600 (400, 1000) | 0.43 |

| Fluid replacement, ml/kg/hr, median (IQR) | 10.8 (7.9, 12.2) | 12.4 (9.0, 16.4) | 0.20 |

| Urine output, ml/kg/hr, median (IQR) | 3.8 (2.4, 4.5) | 2.3 (1.6, 3.0) | 0.003 |

| Blood Na+ level, mEq/L, mean (SD) | |||

| • At T0 | 138 (2.5) | 138 (2.7) | 0.706 |

| • At T45 | 136 (3.5) | 141 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| • At T105 | 137 (2.6) | 140 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Serum Osmolarity, mOsm/kg, mean (SD) | |||

| • At T0 | 291 (8.0) | 290 (6.0) | 0.52 |

| • At T45 | 298 (8.0) | 296 (6.0) | 0.12 |

| • At T105 | 296 (8.0) | 295 (6.0) | 0.48 |

Fig. 2.

Line plot of mean arterial pressure (MAP) over time after administering the hyperosmolar solutions. There were no significant differences in the MAP between the two groups (p value > 0.99).

Fig. 3.

Line plot of heart rate (HR) over time after administering the hyperosmolar solutions. There were no significant differences in HR between the two groups (p value > 0.99).

Fig. 4.

Line plot showing the mean pulse pressure variation (PPV) after administering the hyperosmolar solutions. There was no statistically significant change in PPV between the two groups (p value > 0.99).

The incidence of good brain relaxation (grades I-II) was not significantly different between the two groups (p value = 0.40) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Brain relaxation grading.

| Brain relaxation grading | M group n (%) | H group n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade I | 7 (21.2) | 10 (30.3) | 0.54 |

| Grade II | 19 (57.6) | 13 (39.4) | |

| Grade III | 4 (12.1) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Grade IV | 3 (9.1) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Good grade (I–II) | 26 (78.8) | 23 (74.2) | 0.40 |

The incidence of rescue interventions and postoperative outcomes were similar in both groups (Table 4). Three patients underwent reoperative craniotomy; however, only one patient in the M group received the second dose. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the postoperative GCS score, new focal neurological deficit score, LOICU score, or LOS. There were no other serious adverse events, including acute kidney injury, osmotic demyelination syndrome, or mortality, after one month.

Table 4.

Incidence of rescue interventions and postoperative outcomes.

| Data | M group (n = 33) | H group (n = 33) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted PEEP = 0, n (%) | 7 (21.2) | 10 (30.3) | 0.40 |

| Hyperventilation, n (%) | 9 (27.3) | 9 (27.3) | 0.38 |

| Prescribed antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 27 (81.8) | 29 (87.9) | 0.49 |

| Prescribed vasopressor drugs, n (%) | 5 (15.2) | 9 (27.3) | 0.23 |

| 2nd dose of hyperosmolar solution, n (%) | 1 (3.03) | 0 | >0.99 |

| Re-operative craniotomy, n (%) | 1 (3.03) | 2 (6.06) | >0.99 |

| Postoperative GCS at 24 h, n (%) | |||

| • Good (score of 13–15) | 31 (93.9) | 29 (87.9) | 0.72 |

| • Moderate (score of 9–12) | 2 (6.1) | 3 (9.1) | |

| • Severe (score < 9) | 0 | 1 (3.03) | |

| New neurological deficit, n (%) | 7 (21.2) | 5 (15.2) | 0.52 |

| Improved neurological deficit, n (%) | 8 (24.2) | 9 (27.3) | 0.78 |

| LOICU, days, median (IQR) | 1 (1,1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.89 |

| LOS, days, median (IQR) | 6 (6,8) | 6 (6.8) | 0.44 |

Discussion

Brain tightness is a critical concern during craniotomy, as it can significantly impact surgical exposure, prolong operative time, and increase the risk of complications. Hyperosmolar solutions are commonly administered to facilitate brain relaxation and optimize surgical conditions. In the present study, the incidence of good brain relaxation grading was not significantly different between the 3% hypertonic saline group and the 20% mannitol group. These findings were similar to previous studies6,7. Although we studied supratentorial and posterior fossa tumours, previous studies focused only on supratentorial tumours.

The proper dose of hyperosmotic solution has been a controversial issue. Some studies9,10 have shown that high doses effectively reduce ICP, while others have used low doses11,12. At a dose of 3 ml/kg, both 20% mannitol and 3% hypertonic saline produced comparable and sustained increases in mean blood osmolarity. Specifically, the blood osmolarity was 298 mOsm/kg for mannitol and 296 mOsm/kg for hypertonic saline at T45. At T105, the values were 296 mOsm/kg for mannitol and 295 mOsm/kg for hypertonic saline. The primary effect of both hypertonic solutions was a reduction in water content, resulting in equivalent brain shrinkage. These findings are comparable with those of Hernández-Palazón et al.13 who compared a low dose of 3 mg/kg with 5 mg/kg 3% hypertonic saline. There was no significant difference in the incidence of brain relaxation. Therefore, the low dose of 3 mg/kg potentially achieved effective brain relaxation. In addition to supratentorial tumours, our study included patients with posterior fossa tumours to enhance the generalizability of the findings across different intracranial regions. Although the posterior fossa was a confined anatomical space where even minor swelling could significantly impact surgical conditions and increase the risk of brainstem compression, our results demonstrated no significant differences in brain relaxation outcomes between tumour locations. This suggested that both 3% hypertonic saline and 20% mannitol were similarly effective in achieving satisfactory brain relaxation, regardless of tumour location. However, given the unique challenges associated with posterior fossa surgeries, future studies specifically targeting this subgroup would be valuable to confirm and expand upon these findings.

Controlling haemodynamic parameters was challenging after administering hyperosmolar solutions; however, we found that these parameters could be effectively managed to achieve the target, with no significant differences between the two groups. Singla et al.7 compared 5 mg/kg 3% hypertonic saline and 5 mg/kg 20% mannitol and reported a lower MAP in the mannitol group than in the 3% hypertonic saline group. Our study findings differed, which may be due to the dose of hyperosmolar solutions used. However, Hernández-Palazón et al.5 investigated the same dose of 3 mg/kg hyperosmolar solutions and reported that it preserved haemodynamic stability, with no statistically significant alterations observed. Furthermore, electrolyte imbalance and urine output are a concern. We detected increased urine output in the mannitol group, which is consistent with previous findings7.

With respect to rescue intervention, we found no significant difference in incidence between the two groups. One patient in the 20% mannitol group developed a postoperative haematoma and subsequently underwent reoperation for blood clot removal. A second dose of 20% mannitol was administered due to pronounced brain swelling. Two patients in the 3% hypertonic saline group continued to have elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and subsequently underwent another operation to place a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt. However, these patients did not require a second dose of 3% hypertonic saline.

Furthermore, postoperative clinical outcomes, as well as the LOICU and LOS, were similar between the two groups. These findings were consistent with data from Dostal et al.12 who compared the effects of similar doses of 3% hypertonic saline and 20% mannitol in patients undergoing elective brain tumour resection.

Our study had three limitations. First, we included only patients who were not at high risk for tight brain conditions. Due to this, the applicability of the data may be limited. However, brain relaxation remains a critical factor for optimal surgical conditions in all craniotomy cases, regardless of initial swelling severity. Our findings demonstrate that 3% hypertonic saline is as effective as 20% mannitol in achieving satisfactory brain relaxation, supporting its role as a viable alternative in routine neurosurgical practice. Further studies in populations with a higher risk of cerebral edema would be valuable to confirm and expand upon these findings. Second, this study lacked objective measures of brain relaxation. Brain relaxation was assessed subjectively by the operating neurosurgeons, which may have introduced observer bias. Future studies could benefit from enrolling high-risk patients and employing objective tools—such as intraoperative real-time CT scanning—to evaluate the relationship between intracranial contents and cranial capacity, thereby providing more reliable and reproducible assessments. In addition, although the GCS was widely used in clinical practice due to its simplicity and practicality, it remained a relatively crude tool that might not have captured subtle or specific neurological deficits. GCS scores could also have been influenced by various perioperative factors, including the duration of surgery, the patient’s baseline condition, and postoperative management strategies such as prolonged analgosedation. These factors may have confounded the interpretation of postoperative neurological status. Future research should consider incorporating more comprehensive and objective neurological outcome measures. Third limitation of this study was the presence of baseline differences between the two groups despite randomization, particularly regarding tumour location and tumour type. The mannitol group had a higher proportion of posterior fossa tumours, and no glioma cases were present in this group. Only four patients who underwent glioma resection were included, all of whom had been assigned to the 3% hypertonic saline group. This small sample size precluded any meaningful subgroup analysis regarding brain relaxation strategies specifically in glioma cases. Previous studies had emphasized that gliomas were tumours in which achieving adequate intraoperative brain relaxation was particularly challenging due to their infiltrative nature and associated brain edema14. Therefore, optimal brain relaxation in glioma surgery was considered crucial for maximizing the extent of resection and minimizing postoperative neurological deficits15. Although brain relaxation scores did not differ significantly between tumour types or locations, the potential influence of tumour characteristics on intraoperative brain relaxation could not be fully excluded. Additionally, a small number of patients in our cohort had obstructive hydrocephalus—three in the mannitol group and five in the 3% hypertonic saline group—with no statistically significant difference between groups. As the pathophysiology of brain tightness in obstructive hydrocephalus differed from that of perifocal brain edema, their inclusion might have represented a potential source of bias. This heterogeneity underscored the need for future studies with larger sample sizes to achieve greater baseline homogeneity and to allow for stratified analyses based on tumour location, pathology, and underlying mechanisms of brain tension. Future investigations with larger sample sizes are warranted to achieve greater baseline homogeneity and to allow for stratified analyses according to tumour location and pathology.

Conclusion

The administration of 3% hypertonic saline has been shown to be both safe and effective in facilitating brain relaxation during surgery. This positions 3% hypertonic saline as a potentially viable alternative to 20% mannitol for intraoperative brain relaxation. Additionally, 3% hypertonic saline was associated with lower urine output as compared to 20% mannitol, which may provide a beneficial advantage in managing fluid balance throughout the surgical procedure.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Kaewjai Thepsuthammarat for assistance with data analysis.

Abbreviations

- PPV

Pulse pressure volume

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- HR

Heart rate

- BP

Blood pressure

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LOICU

Length of ICU stay

- LOS

Length of hospital stay

- BMI

Body mass index

- GCS

Gasglow coma score

- ICP

Intracranial pressure

- VP

A ventriculoperitoneal

- CT

Computer tomography

Author contributions

C.T., W.T. and P.K. participated in manuscript preparation include conception. C.T., W.T., P.K., P.D., A.M.K., N.P., A.K., D.S., M.S., L.S. and T.J. participated in data collection and/or processing. C.T., W.T. and P.K. participated in drafting the article. C.T., W.T., P.K., P.D., A.M.K., N.P., A.K., D.S., M.S., L.S. and T.J. participated in critically revising the article.

Funding

This study was supported by an Invitation Research Grant from the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University (IN65116).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Consent to participate

All participants provide written consent following the Declaration of Helsinki before enrolment.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research (HE641396).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dabrowski, W. et al. Potentially detrimental effects of hyperosmolality in patients treated for traumatic brain injury. J. Clin. Med.10, 4141. 10.3390/jcm10184141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thongrong, C. et al. Current purpose and practice of hypertonic saline in neurosurgery: A review of the literature. World Neurosurg.82, 1307–1318 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, W. et al. Mannitol in critical care and surgery over 50+ years: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and complications with meta-analysis. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol.31, 273–284 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Manninen, P. H., Lam, A. M., Gelb, A. W. & Brown, S. C. The effect of high-dose mannitol on serum and urine electrolytes and osmolality in neurosurgical patients. Can. J. Anaesth.34, 442–446 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hernández-Palazón, J. et al. A comparison of equivolume, equiosmolar solutions of hypertonic saline and mannitol for brain relaxation during elective supratentorial craniotomy. Br. J. Neurosurg.30, 70–75 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali, A. et al. Comparison of 3% hypertonic saline and 20% mannitol for reducing intracranial pressure in patients undergoing supratentorial brain tumor surgery: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 30, 171–178 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Singla, A., Mathew, P. J., Jangra, K., Gupta, S. K. & Soni, S. L. A comparison of hypertonic saline and mannitol on intraoperative brain relaxation in patients with Raised intracranial pressure during supratentorial tumors resection: A randomized control trial. Neurol. India. 68, 141–145 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, J., Gelb, A. W., Flexman, A. M., Ji, F. & Meng, L. Definition, evaluation, and management of brain relaxation during craniotomy. Br. J. Anaesth.116, 759–769 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rozet, I. et al. Effect of equiosmolar solutions of mannitol versus hypertonic saline on intraoperative brain relaxation and electrolyte balance. Anesthesiology107, 697–704 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quentin, C. et al. A comparison of two doses of mannitol on brain relaxation during supratentorial brain tumor craniotomy: A randomized trial. Anesth. Analg. 116, 862–868 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu, C. T. et al. A comparison of 3% hypertonic saline and mannitol for brain relaxation during elective supratentorial brain tumor surgery. Anesth. Analg. 110, 903–907 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dostal, P. et al. A comparison of equivolume, equiosmolar solutions of hypertonic saline and mannitol for brain relaxation in patients undergoing elective intracranial tumor surgery: A randomized clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 27, 51–56 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández-Palazón, J. et al. A dose-response relationship study of hypertonic saline on brain relaxation during supratentorial brain tumour craniotomy. Br. J. Neurosurg.32, 619–627 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prabhakar, H., Singh, G. P., Anand, V. & Kalaivani, M. Mannitol versus hypertonic saline for brain relaxation in patients undergoing craniotomy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.7, CD010026 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, Z. et al. A review on surgical treatment options in gliomas. Front. Oncol.13, 1088484 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.