Abstract

In response to the growing concerns regarding pharmaceutical contamination of our aquatic systems, targeted actions are being implemented to align with the recommendations of the European Commission. However, a challenge lies in finding effective, accurate, and green chemistry-compliant methods for analyzing these compounds in complex matrices. This study introduces a highly sensitive and sustainable ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) method for simultaneously determining carbamazepine, caffeine, and ibuprofen in water and wastewater. This method exhibits impressive advantages: exceptional sensitivity, high selectivity, and an economical sample preparation strategy resulting from the absence of an evaporation step after solid-phase extraction (SPE), as well as a short analysis time (10 min). Following the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) guidelines Q2(R2), the developed and validated method proved to be specific, linear (correlation coefficients ≥ 0.999), precise (RSD < 5.0%), and accurate (recovery rates ranging from 77 to 160%). The limits of detection were 300 ng/L for caffeine, 200 ng/L for ibuprofen, and 100 ng/L for carbamazepine, respectively. The limits of quantification (LOQs) were 1000 ng/L for caffeine, 600 ng/L for ibuprofen, and 300 ng/L for carbamazepine. The advanced UHPLC-MS/MS method presented in this article constitutes a green and blue analytical technique for the precise detection and quantification of trace levels of pharmaceutical contaminants in aquatic environments. This method has been validated and exemplified using a case study from the Kraków area, highlighting its high efficiency, reliability, and minimal environmental impact. This approach aligns with the concept of sustainable analytics, combining ecological aspects with high-quality results. This study is therefore crucial for the effective monitoring of pollutants, the assessment of environmental and health risks, and ensuring water quality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-15614-4.

Keywords: Green analytical chemistry, UHPLC-MS/MS technique, SPE, Pharmaceuticals, Water, Method validation

Subject terms: Environmental chemistry, Environmental impact, Mass spectrometry, Analytical chemistry, Environmental sciences, Hydrology

Introduction

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and quality standards in monitoring represent primary aspects of contemporary scientific inquiry to establish effective, safe, and environmentally benign analytical methodologies. The synergistic integration of these components creates an innovative approach for modern monitoring practices, a development of particular salience given the escalating global issue of pharmaceutical presence in aqueous environments. GAC focuses on techniques that limit the consumption of substances, energy, and waste, while maintaining precision, which in monitoring translates into ecological and effective solutions in long-term surveillance programs. Conversely, quality standards in monitoring assure the reliability and accuracy of obtained data, which are indispensable for informed decision-making in environmental stewardship, public health initiatives, and industrial operations. The integration of these two aspects enables the development of robust and sustainable analytical methods that are technically effective and consistent with the principles of sustainable development 1.

In recent decades, the global issue of environmental contamination by pharmaceuticals has become a subject of intense scientific scrutiny and growing public concern. These compounds, often referred to as “emerging contaminants”, encompass a broad spectrum of substances, from analgesics and antibiotics to hormones and psychoactive drugs, that were not traditionally monitored in the environment. The escalating global consumption of pharmaceuticals, both by humans and in veterinary applications, results in their continuous and significant introduction into the aquatic environment through municipal and industrial wastewaters. Conventional wastewater treatment plants often demonstrate insufficient efficacy in eliminating these compounds, leading to their pervasive presence in surface and groundwaters2–4. The estimated average annual consumption of pharmaceuticals is approximately 15 g per capita, translating to about 1.2 × 105 tons per year globally, considering a world population of 8,119 million people2,5. Particularly concerning are data indicating that a substantial fraction (10–20%) of ingested pharmaceuticals is excreted largely unchanged into wastewater6,7, and their metabolites can transform into active compounds in ecosystems8–11. Additional significant sources of pharmaceutical pollution include industrial discharges, household disposal, landfill leachate, agricultural practices, and aquaculture feed additives12–14. Despite relatively low individual discharge quantities, the persistent release of these substances leads to their accumulation in aquatic ecosystems15. Globally, high concentrations of active pharmaceutical ingredients are often associated with arid climates, inadequate sanitation infrastructure, and direct contact between surface waters and municipal landfills, while low levels are characteristic of limited anthropogenic impact, advanced wastewater treatment, and high river flow rates7,16–18.

The presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment poses a serious ecological threat. Even at trace concentrations, they can exert toxic effects on aquatic organisms, lead to endocrine disruption (e.g., feminization of fish), and contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance, representing a global public health challenge. Furthermore, long-term exposure to these substances in drinking water raises potential risks to human health, underscoring the urgent need for effective monitoring.

Pharmaceuticals from various therapeutic groups commonly detected in surface water and wastewater were considered as indicators of anthropogenic contamination3: caffeine (CAF), a widely used psychoactive agent; ibuprofen (IBU), a common non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; and carbamazepine (CBM), an anticonvulsant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the analyzed pharmaceuticals.

| No. | Chemical | Acronym | Structure | Empirical formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caffeine | CAF |  |

C8H10N4O2 |

| 2 | Ibuprofen | IBU |  |

C13H18O2 |

| 3 | Carbamazepine | CBM |  |

C15H12N2O |

Their selection is dictated not only by their widespread environmental presence but also by their specific chemical and pharmacological properties, which can influence their behavior in aquatic ecosystems. Carbamazepine (CBM), a dibenzoazepine derivative with anticonvulsant properties, stands out as one of the most widely accepted and well-established indicators of environmental contamination due to its high chemical stability, widespread medical use, and poor biodegradability in wastewater treatment plants7,19. Caffeine (CAF), as one of the most widely consumed psychoactive substances globally, is present in coffee, tea, energy drinks, and numerous other products. Its immense global consumption directly translates to a continuous and significant release into sewage systems and subsequently into the aquatic environment. For this reason, caffeine is broadly recognized as an excellent marker for domestic wastewater contamination, serving as a valuable indicator of human impact on surface waters20,21. Its presence typically correlates with the influx of insufficiently treated sewage. Despite undergoing faster biodegradation than CBM, CAF is still frequently detected in surface waters, especially near urban agglomerations and wastewater discharge points. The variable presence and degradation levels of CAF provide additional insights into the self-purification processes of waters and the efficiency of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs)22.

Ibuprofen (IBU) is one of the most frequently used over-the-counter pain relievers and anti-inflammatory drugs. Its massive global consumption leads to continuous and significant introduction into the aquatic environment23. Although IBU is partially degradable in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), substantial quantities still pass into receiving waters. Its presence in treated effluent and surface waters is well-documented, making it a significant “emerging contaminant”. Crucially, environmental concentrations of IBU can exert negative ecotoxicological effects on aquatic organisms, including fish and invertebrates, impacting their health, development, behavior, and hormonal balance. Therefore, monitoring its presence is vital for assessing the ecological quality of water bodies24. Ibuprofen also serves as a representative example of the broad class of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), which are among the most frequently detected pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments. Monitoring its presence allows for a general estimation of the environmental burden from these substances25.

A variety of conventional analytical techniques are utilized to monitor pharmaceutical contaminants in aquatic environments, with each method offering different levels of sensitivity, selectivity, and applicability. One of the most commonly used techniques is UV–Vis spectrophotometry, which is based on measuring the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by the analytes. Although this method is simple and widely available, it suffers from low selectivity and a high susceptibility to interference from other light-absorbing substances, which complicates the analysis of complex environmental matrices26–29. Similar limitations are observed in spectrofluorometry, which measures the fluorescence of molecules, often requiring prior derivatization. Despite its high sensitivity for certain compounds, the technique is prone to matrix interferences and is not suitable for broad-spectrum pharmaceutical analysis30–32. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy enables the identification of chemical compounds based on the characteristic vibrational bands of functional groups. However, its applicability in detecting trace concentrations of pharmaceuticals in environmental samples is limited due to its relatively low sensitivity and inability to effectively analyze complex mixtures. Potentiometry, an electrochemical method, is relatively simple and cost-effective but suffers from low sensitivity and selectivity, and it is particularly prone to ionic interferences in environmental matrices33. Capillary electrophoresis (CE) offers improved resolution by separating analytes based on their electrophoretic mobility. Despite its advantages of minimal sample consumption and good separation efficiency, CE is generally more difficult to couple with mass spectrometric detection and tends to have lower sensitivity compared to modern analytical methods34,35. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is among the most widely used chromatographic techniques for pharmaceutical analysis, enabling compound separation based on retention behavior and detection via UV, DAD, or FLD detectors. However, HPLC is limited by its lower selectivity and the inability to reliably identify analytes in complex environmental matrices26,36–40. Gas Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS), on the other hand, is a sensitive and selective technique for the analysis of volatile and thermally stable compounds. Nonetheless, most pharmaceuticals found in aquatic environments are non-volatile and/or thermally labile, often requiring laborious and inefficient derivatization steps, which complicate sample preparation and may result in analyte loss41–43.

In comparison to these techniques, Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) offers several critical advantages. It provides substantially higher sensitivity and selectivity, allowing for the detection and quantification of pharmaceuticals at ng/L levels or even lower. Through the use of Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), this method enables unambiguous identification of compounds based on their molecular mass and specific fragmentation patterns, minimizing matrix interferences. Unlike methods such as HPLC or GC–MS, UHPLC-MS/MS typically does not require derivatization, simplifying sample preparation and reducing the risk of analyte loss. Moreover, the use of UHPLC significantly shortens analysis time and improves resolution. Due to these attributes, UHPLC-MS/MS is currently regarded as the gold standard in the analysis of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments, offering unmatched performance under real-world environmental monitoring conditions. Based on the above, precise, sensitive, and efficient monitoring of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment is essential. It enables risk assessment for ecosystems and humans, provides crucial data for informing regulatory policy, and supports the development of effective pollution management strategies. However, the determination of trace concentrations of pharmaceuticals in complex environmental matrices is associated with numerous analytical challenges. These primarily include: the low concentrations of target analytes (often at ng/L levels), the presence of numerous matrix interferences that can affect the analytical signal, and the fundamental need for high selectivity and sensitivity in analytical methods44.

In response to these challenges, this work presents the development and validation of a UHPLC-MS/MS method that not only exhibits high analytical performance but also possesses significant “green” and “blue” analytical attributes. A key innovation of presented method is the omission of the energy- and solvent-intensive evaporation step following solid-phase extraction. This directly contributes to reducing solvent consumption and waste generation, aligning with sustainability principles. The developed method is simultaneously highly sensitive and selective, enabling the detection of pharmaceuticals at ng/L levels, which is crucial for reliable ecological and human health risk assessment. It is also efficient and rapid, significantly reducing per-sample analysis time, a vital aspect for effectively conducting routine monitoring campaigns and promptly responding to changing environmental conditions. Furthermore, the method is economical, potentially lowering reagent and equipment operation costs, which is highly significant for laboratories with limited budgets. Lastly, it is more environmentally sustainable (“green”/“blue”) due to a substantial reduction in solvent consumption and waste generation, fully aligning with increasing regulatory requirements and global trends in environmental analytical chemistry45. In conclusion, analytical methods with these characteristics are indispensable for regulatory bodies, environmental agencies, and water management entities to effectively implement monitoring programs, assess the efficacy of remediation efforts, and better manage the problem of pharmaceutical contamination in the environment.

The objective of this study was to develop and validate a fast, sensitive, and simple Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) method for the quantification of three pharmaceuticals from different therapeutic classes (stimulants, anticonvulsants, and antipyretics) in river and wastewater matrices. The selection of the three analytes: carbamazepine (CBM), caffeine (CAF), and ibuprofen (IBU), is based on their complementarity as markers. CBM serves as an indicator of persistent pharmaceutical contamination due to its high stability and poor biodegradability. CAF, given its widespread consumption and recognizability, acts as a direct indicator of domestic wastewater contamination. IBU was chosen as a representative of widely used pharmaceuticals with proven negative impacts on aquatic ecosystems and incomplete elimination in WWTPs. Together, these compounds provide a comprehensive picture of anthropogenic contamination in aquatic environments.

Additionally, to thoroughly evaluate both the environmental footprint and the practical utility of the newly developed analytical method, a comprehensive assessment was conducted using the Analytical Greenness metric (AGREE) and the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI)45. Furthermore, to assess the applicability of the developed and validated method under real conditions and to identify potential, unforeseen issues related to the sample matrix, preparation procedures, or instrumental analysis, the method was subjected to verification on real environmental water samples collected from the Kraków area. The Kraków case study is an integral part of assessing the effectiveness and usefulness of the UHPLC-MS/MS method under real environmental monitoring conditions in a region strongly affected by industrial and urban activities. The data obtained provides specific information on the level of pollution and allows for the assessment of whether the developed method is a suitable tool for long-term monitoring of water quality and assessment of the effectiveness of pharmaceutical pollution reduction strategies.

Material and methods

Reagents and chemicals

Certified Reference Materials for caffeine (> 99%), ibuprofen (> 99%), and carbamazepine (> 99%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Poland). Acetonitrile and formic acid (LC–MS grade) were purchased from Merck KGaA, and methanol was purchased from POCH. Ultra-pure water was produced using a HydroLab 20 UV water purification system.

Standard solution preparation

A stock solution at a concentration of 1 mg/ml of the substances: CAF, IBU, and CBM in a mixture of acetonitrile and water at a ratio of 1:1 was prepared (stock solution). The stock solution was diluted in a mixture of acetonitrile and water at a ratio of 1:1 to obtain solutions with the following concentrations 200, 600, 1200, 2000, 6000, 12,000, 24,000 to 60,000 ng/L for IBU, and 100, 300, 500, 1000, 3000, 5000 to 10,000 ng/L for CAF and CBM (calibration solutions).

In the conducted study, each LC–MS/MS analysis was performed using a freshly prepared calibration curve. The external calibration approach applied involved preparing a series of calibration standards in the same solvent used to reconstitute the samples after solid-phase extraction (SPE) concentration, namely, a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of acetonitrile and water. As a result, both the calibration standards and the samples were introduced into the instrument in an equivalent solvent matrix.

Sample solution preparation

To separate and enrich the analyzed compounds from the sample matrix, a 12-position vacuum extraction system from BAKER was utilized with HLB sorbent extraction cartridges. In the optimized SPE protocol, Oasis HLB cartridges were placed in the vacuum apparatus. In the first step, the SPE sorbent was conditioned with 5 mL of methanol, followed by 5 mL of ultra-pure water. Subsequently, 250 mL of river water sample was applied to the SPE cartridge at a flow rate of 6 mL/min. During the third step, the cartridges were washed with 5 ml of 5% methanol and left to dry under vacuum for 15 min. The target compounds were then eluted by adding 2 ml of methanol to the extraction column. The prepared sample was subjected to UHPLC-MS/MS analysis.

Instruments

Analytical balance (Mettler Toledo MS 105, OHAUS PA114CM/1), ultrasonic bath (InterSonic IS-5.5), syringe filters 0.45 µm, 25 mm PVDF (Millipore), cellulose filter paper (0.45 mm) (Eurochem BGD), vacuum solid-phase extraction system (SPE) from BAKER with Waters™ Oasis HLB 60 mg, 3 mL columns were used.

The concentrations of selected pharmaceuticals were determined using a UPLC system (Vanquish, Thermo Scientific) coupled with quadrupole mass spectrometry (TSQ Altis Plus, Thermo Scientific) with a HESI (Heated Electrospray Ionization) ion source. The analysis utilized a Chromolith® Performance RP-18e column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, Merck) at 20 °C, which stands out due to its unique monolithic silica structure with a porous design. Unlike traditional packed columns with spherical particles, Chromolith® is made from a single piece of porous silica, creating a network of macropores (around 2 µm) and mesopores (around 13 nm). The surface of this monolithic structure is chemically modified with octadecylsilane groups (C18), imparting a reversed-phase (RP) character. The letter "e" in the name "RP-18e" signifies that the silanol groups on the silica surface are end-capped, which minimizes interactions with polar analytes and improves peak shape. This specific design of the Chromolith® column significantly facilitates the separation of the analyzed pharmaceutical substances. Key benefits derived from its unique structure include fast separation and shorter analysis times, as the large macropores within the monolithic structure allow for very rapid mobile phase flow at low back pressure, resulting in significantly shorter retention times and faster analysis compared to traditional packed columns, aligning with the principles of “green” and “blue” analytical chemistry. Furthermore, the C18 reversed-phase enables effective separation of both polar and non-polar analytes based on their hydrophobicity; differences in logP values and the chemical structures of the analyzed pharmaceutical substances (e.g., presence of acidic, basic, phenolic groups) lead to varied hydrophobic interactions with the C18 stationary phase. The porous structure and end-capping characteristics of the column’s surface contribute to a reduced matrix effect by facilitating the rapid elution of the sample matrix, thereby minimizing its negative impact on the sensitivity and peak shape of the analytes, which is particularly important in environmental sample analysis. Finally, the monolithic structure inherently offers enhanced stability and repeatability, being less prone to packing degradation and channeling, which translates to better column performance and higher consistency of results over a longer operational period46. An isocratic flow rate of 0.5 mL/min was applied using a mobile phase consisting of eluent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and eluent B (acetonitrile), mixed in a 50:50 (v/v) ratio. Sample injection volume was 20 µl. Data were collected in positive ionization mode for CAF and CBM, and in negative ionization mode for IBU. Compounds in positive mode were detected as their protonated molecules ([M + H]+), while in negative mode as ([M-H]-). The most intense fragment ion from each precursor ion was selected for quantification. Detailed detection parameters MS/MS method have been presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

MS/MS parameters of the method.

| Parameter | Caffeine (CAF) | Ibuprofen (IBU) | Carbamazepine (CBM ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Mode | HESI (positive) | HESI (negative) | HESI (positive) |

| MRM Transitions (m/z) | 195-69 | 205-159 | 237-165 |

| 195-110 | 205-161 | 237-179 | |

| 195-138 | 205-178 | 237-194 | |

| Collision Energy (V) | 28.56 | 5.43 | 47.11 |

| 23.98 | 5.43 | 37.37 | |

| 19.68 | 8.15 | 20.4 | |

| Dwell Time (ms) | 98.6 | 118.5 | 98.6 |

| Aux Gas (Arb) | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Sheath Gas (Arb) | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Ion Tranfer Tube Temp. (oC) | 380 | 380 | 380 |

| Vaporizer Temp (oC) | 350 | 350 | 350 |

| SheathGasFlow | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Capillary (V) | 3500 | 3500 | 3500 |

| CID Gas (mTorr) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

Study area and sampling

To demonstrate the analytical applicability of the developed method to assess the level of contamination by selected pharmaceutical substances, the Vistula River and its six largest tributaries in the Kraków area (Rudawa, Drwina Długa, Serafa, Dłubnia, Prądnik, and Wilga) were selected for analysis (Fig. 1). For this study, samples from one of Kraków’s wastewater treatment plants were chosen due to their complex matrix, which poses a challenge for conventional analytical methods.

Fig. 1.

Localization of the sampling points (Topographic map sourced from geoportal.gov.pl and adapted using AutoCAD LT 2025 to include sample collection points).

Kraków is located in Southern Poland, at the foot of the Carpathians, at the meeting point of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, the Carpathian Foothills, and the Sandomierska Valley. The city of Kraków has a population of 779.966 inhabitants (2nd largest community in Poland). The number of people per square kilometer is 2.386 (20th community in Poland in terms of population density)47. Kraków is characterized by an asymmetrical hydrographic network, with the Vistula River as its central axis. The river flows west to east over a length of 41.2 km within the city limits. The left-bank tributaries of the Vistula within the borders of Krakow include: Sanka, Rudawa, Białucha-Prądnik, Dłubnia, the Suchy Jar (Kanar) canal, the Kościelnicki Stream (Kościelnicki Stok), and the right-bank tributaries Sidzinka, Kostrzecki Stream, Pychowicki Stream, Wilga, Serafa, and Podłężanka48. In Kraków, there are two mechanical–biological wastewater treatment plants: “Płaszów” and “Kujawy.” The “Płaszów” plant serves 780,000 PE (Population Equivalent) from the Kraków area, while “Kujawy” is part of the Nowa Huta system, treating municipal sewage from 250,000 PE of Nowa Huta49,50.

Water samples and wastewater before and after treatment were collected in September 2024 following the Polish standards51,52. Sampling locations were strategically chosen to ensure both accessibility and safety during fieldwork. Additionally, sufficient water depth to immerse the container at the collection point was ensured to avoid disturbing the bottom sediments. Containers were immersed in the mainstream of the river, against the current of the river. Then samples were directly transferred into 1-L amber glass bottles, which had been pre-cleaned by rinsing three times with the same water being sampled. All samples were filtered using cellulose filter paper (0.45 mm) and membrane filters, followed by solid-phase extraction (SPE) using HLB resin columns.

Results

Validation results of the analytical method

The LC–MS/MS method was validated according to the requirements of the European Commission and ICH guidelines53. Validation parameters included selectivity, linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), recovery, precision, accuracy, and matrix effect.

Limits of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ)

The limits of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were calculated using the formulas recommended in the ICH guideline53: LOD = 3.3 * SD, LOQ = 10 * SD, where SD is the standard deviation of the signal at the lowest point of the calibration curve.

LOD values for investigated pharmaceuticals were as follows: CAF 300 ng/L, IBU 200 ng/L, and CBM 100 ng/L. The LOQ concentrations were 1000 ng/L, 600 ng/L, and 300 ng/L, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

The limits of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), the coefficient of determination (R2), dynamic range (LDR) and repeatability (RSD) for investigated pharmaceuticals.

| Parameters | Caffeine (CAF) | Ibuprofen (IBU) | Carbamazepine (CBM ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity range | 1000 to 10,000 ng/L | 600 to 60,000 ng/L | 300 to 10,000 ng/L |

| Slope n = 3 | 2291.7 ± 2.97 | 34.17 ± 0.0001 | 31,578.0 ± 0.54 |

| Intercept n = 3 | 905.4 ± 13.84 | 20.11 ± 0.0003 | 48,880.4 ± 2.35 |

| Correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.99995 | 0.99993 | 0.99998 |

| Limit of detection | 300 ng/L | 200 ng/L | 100 ng/L |

| Limit of quantification | 1000 ng/L | 600 ng/L | 300 ng/L |

| Repeatability Precision (RSD) n = 6 | 2.62% | 3.10% | 2.84% |

| Repeatability Intermediate Precision (RSD) n = 6 | 2.72% | 2.04% | 1.14% |

Linearity

Calibration curves were performed for concentration levels ranging from LOQ to 60,000 ng/L for IBU and from LOQ ng/L to 10,000 ng/L for CAF and CBM. The analysis was performed according to the conditions described in the analytical method. The obtained peak areas of pharmaceuticals were plotted versus their corresponding concentrations, and the linear regression analysis was performed (y = ax + b). The quality of the linear fit was evaluated by verifying the values of the correlation coefficient R determined for the obtained data.

The calibration curve plots for the investigated pharmaceuticals are presented in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S1, S2, and S3).

The obtained values of correlation coefficients (the R value for all substances is ≥ 0.9999) are following the ICH requirement, confirming the linearity of the method in the tested concentration ranges for the studied substances 53.

Accuracy

For environmental samples, recovery is usually determined based on extraction efficiency and depends on extraction conditions54,55. In the case of enrichment of analytes using the SPE technique, it is necessary to select appropriate columns, type of eluent, and possibly method of solvent evaporation, and then sample dissolution. The number of operations can be a source of considerable error56. To avoid this problem, the use of appropriate matrices is recommended at this stage57.

The accuracy of the method was tested by verifying the recovery of IBU, CBM, and CAF concentration in solutions (spiked samples). Two matrices (tap water and Wisła River water) were spiked with the substance solutions at several concentration levels (Table 4). Solid phase extraction (SPE) technique, where used to clean up and enrich samples according to the described method. Calibration standards were prepared and used for calculations.

Table 4.

Recoveries and accuracy for caffeine, ibuprofen and carbamazepine in 200 mL of spiked tap waters and river waters.

| Matrix and Spiked Concentration | Theoretical concentration [ng/L] | Mean Measured Concentration (n = 3) [ng/L] | Recovery (n = 3) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine (CAF) | |||

| Tap water matrix | 0.05 ± 0.01 | ||

| Tap water + 1 ng | 1.05 | 1.46 ± 0.04 | 138.94 |

| Tap water + 5 ng | 5.05 | 4.54 ± 0.12 | 89.79 |

| Tap water + 10 ng | 10.05 | 9.82 ± 0.26 | 97.75 |

| Wisła matrix | 75.42 ± 1.98 | ||

| Wisła + 10 ng | 85.42 | 85.60 ± 2.24 | 99.79 |

| Ibuprofen (IBU) | |||

| Tap water matrix | ND | ||

| Tap water + 1 ng | 1.00 | 1.60 ± 0.050 | 159.52 |

| Tap water + 5 ng | 5.00 | 5.61 ± 0.17 | 112.14 |

| Tap water + 10 ng | 10.00 | 10.74 ± 0.33 | 107.41 |

| Wisła matrix | 19.06 ± 0.59 | ||

| Wisła + 10 ng | 29.06 | 29.01 ± 0.90 | 100.16 |

| Carbamazepine (CBM) | |||

| Tap water matrix | 0.96 ± 0.03 | ||

| Tap water + 1 ng | 1.96 | 1.52 ± 0.04 | 77.38 |

| Tap water + 5 ng | 5.96 | 5.60 ± 0.16 | 93.94 |

| Tap water + 10 ng | 10.96 | 11.07 ± 0.32 | 101.05 |

| Wisła matrix | 47.21 ± 1.34 | ||

| Wisła + 10 ng | 57.21 | 55.55 ± 1.58 | 103.00 |

Extraction recoveries ranged from 77 to 160%. The recoveries were significantly worse for samples spiked with the lowest amount of API (1 ng) compared to the results obtained for matrices spiked with 5 ng and 10 ng API (recoveries in the range of 90–112% and 98–108%, respectively).

Method precision and intermediate precision

In order to determine the precision of the developed method, six independent samples of Wisła River water were prepared and analyzed. Calibration standard solutions were prepared according to the analytical procedure. The intermediate precision of the method was assessed by analyzing the pharmaceutical content in six Wisła River water samples, prepared and analyzed by a different analyst (in a different day), following the same analytical procedure.

The results of the method precision and intermediate method precision assessment are presented in the Supplementary Information in Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

The results demonstrate satisfactory precision of the method (RSD < 5.0%) and proved that this analytical method were repeatable and reproducible. Differences of means between analysts were not more than 5.0%.The difference of assay average results obtained by two analysts was 2.46% for CAF, 4.08% for IBU, and 3.64% for CBM.

Matrix effects

Co-eluting matrix compounds can impact the ionization of the analyte, resulting in signal enhancement or suppression, a phenomenon known as the matrix effect. This effect can cause reduction of accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and repeatability, ultimately leading to inaccurate quantification of sample values9,54. To reduce the matrix effect, selective extraction and improved chromatographic separation were used.

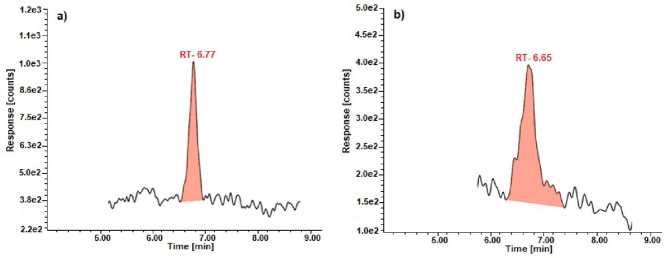

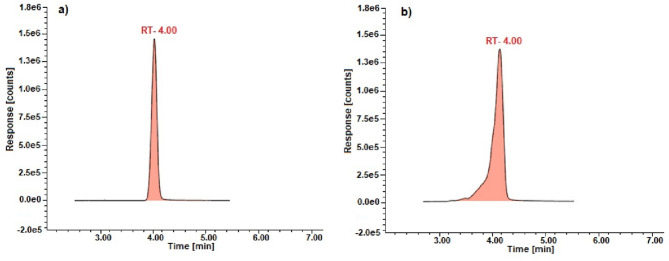

Exemplary chromatograms of standards and of sample solutions (Wisła River) used for assay determination of the pharmaceuticals are shown in the Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Fig. 2.

Chromatograms of the caffeine: (a) standard and (b) sample solution for water from the Wisła River.

Fig. 3.

Chromatograms of the ibuprofen: (a) standard and (b) sample solution for water from the Wisła River.

Fig. 4.

Chromatograms of the carbamazepine: (a) standard and (b) sample solution for water from the Wisła River.

This validated method is specific (the retention times of pharmaceuticals in sample solution corresponded well to the standards) and there were no significant analytical losses or increases in analysis time. Furthermore, the use of MS/MS detection in MRM mode enhances the specificity of the method by targeting unique precursor-to-product ion transitions characteristic of each analyte, thereby minimizing interference from matrix components.

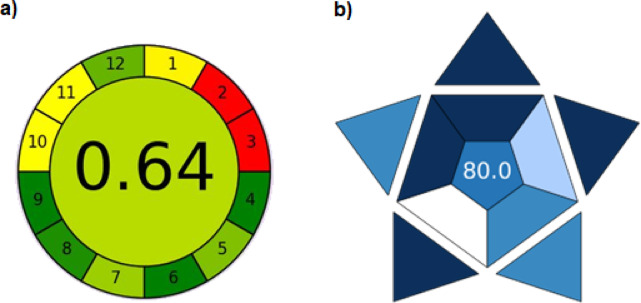

Greenness and blueness assessments

The newly developed analytical method was subjected to a comprehensive evaluation of its environmental impact and practical utility using the Analytical Greenness (AGREE) and Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) tools, respectively45.

The greenness assessment AGREE considered 12 parameters of principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), such as the amounts and toxicity of reagents, generated waste, energy requirements, the number of procedural steps, miniaturization, and automation. This tool can be downloaded from https://mostwiedzy.pl/pl/wojciech-wojnowski,174235-1/AGREE. The result is a pictogram, a clock-shaped graph that is split into 12 pieces, indicating the final score, performance of the analytical procedure in each criterion, and weights assigned by the user58–60.

The blue applicability grade index (BAGI) assesses the analytical practicality of the method, including considerations such as sample throughput, time, and cost. The BAGI tool is publicly available at https://mostwiedzy.pl/en/justyna-plotka-wasylka,647762-1/BAGI. The color gradient of the pictogram visually represents the extent of the method’s adherence to the defined criteria. To meet the designation of "practical," the method must achieve a score of 60 points or higher58–60.

The AGREE score for the UHPLC-MS/MS method was 0.64 (Fig. 5a), indicating a high level of its greenness. This favorable result was primarily attributed to the reduction in the number of analytical steps and the shortening of the analysis time, which translated into savings in materials, energy, and time. Nevertheless, factors such as sample size, the location of the analytical device, and the use of toxic reagents resulted in the appearance of red zones (2 and 3) in the AGREE assessment. The proposed UHPLC-MS/MS method demonstrated a significant advantage over other reported chromatographic methodologies in terms of the number of steps, analysis duration, and the reduced consumption of substantial amounts of organic solvents. The BAGI score for the UHPLC-MS/MS method was 80.0 (Fig. 5b), indicating a high degree of its analytical practicality. The main factors contributing to this favorable “blueness” score were the type of analysis, the short analysis time, and the possibility of simultaneous determination of multiple components belonging to different classes of compounds, which makes the current method a viable alternative to traditional methods used in the routine quality control of water and wastewater. However, certain limitations should be noted, including the necessity of manual sample collection, the relatively large sample volume required, and the costly extraction step.

Fig. 5.

Greenness assessment of the developed UHPLC-MS/MS method using the AGREE tool to determine its environmental impact (a). Blueness assessment of the developed UHPLC-MS/MS method using the BAGI tool to determine its analytical practicability (b).

The levels of target analytes in authentic environmental water matrices

The analysis of real samples was conducted to verify the applicability of the developed method. Samples collected from rivers flowing through the Kraków area (Fig. 1) showed that each of the selected pharmaceuticals was present in these waters, however, their concentrations were usually low, around several dozen ng/L (Table 5).

Table 5.

Concentrations (mean value of 3 measurements) and standard deviation (SD) of pharmaceuticals in surface water and wastewater samples (Kraków, September 2024).

| Location | Compounds [ng/L] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| River | Coordinates | Caffeine (CAF) | Ibuprofen (IBU) | Carbamazepine (CBM) |

| Mean (n = 3) | Mean (n = 3) | Mean (n = 3) | ||

| River | ||||

| Rudawa | 50.057010;19.906710 | 136.31 ± 2.15 | 7.35 ± 3.30 | 46.06 ± 5.54 |

| Drwina Długa | 50.028816;20.088059 | 122.02 ± 3.41 | 43.11 ± 8.33 | 294.42 ± 2.33 |

| Serafa | 50.027884;20.088023 | 154.45 ± 4.04 | 18.04 ± 3.11 | 14.34 ± 9.23 |

| Dłubnia | 50.056667;20.071621 | 74.34 ± 5.23 | 19.23 ± 9.24 | 150.22 ± 5.40 |

| Prądnik | 50.067786;19.973149 | 122.01 ± 4.45 | 5.84 ± 3.12 | 48.16 ± 3.44 |

| Wilga | 50.040213;19.935377 | 80.55 ± 2.11 | 8.42 ± 2.53 | 39.73 ± 5.05 |

| Wisła 1 | 50.053293;19.931573 | 75.42 ± 1.98 | 19.06 ± 0.59 | 47.21 ± 1.34 |

| Wisła 2 | 50.051415;20.072559 | 119.34 ± 7.05 | 16.33 ± 8.23 | 53.81 ± 4.44 |

| WWTP | ||||

| WWTP influent | – | 28,680.51 ± 3.43 | 7967.71 ± 7.07 | 526.45 ± 1.13 |

| WWTP effluent | – | 65.02 ± 3.21 | 15.65 ± 2.33 | 330.13 ± 2.15 |

The highest mean CAF concentration was observed in the Serafa River (154.45 ng/L), while the lowest mean levels were detected in the Dłubnia River (74.34 ng/L) and Wisła 1 River (75.42 ng/L). IBU was also present in surface waters, with the highest mean concentration noted in the Dłubnia and Wisła River (19.23 ng/L) and the lowest in the Rudawa River (7.35 ng/L). CBM generally showed higher concentrations compared to IBU in surface waters, with the peak mean value recorded in the Drwina Długa River (294.42 ng/L) and the minimum mean in the Serafa River (14.34 ng/L). Standard deviations for individual measurements in surface water samples were generally relatively low in relation to the mean values.

Significantly elevated concentrations of the target pharmaceuticals were observed in wastewater samples compared to surface waters. In the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) influent, the mean concentrations were 28,680.51 ng/L for CAF, 7967.71 ng/L for IBU, and 526.45 ng/L for CBM. Following the treatment process (WWTP effluent), the concentrations of these compounds decreased substantially, reaching 65.02 ng/L for CAF, 15.65 ng/L for IBU, and 330.13 ng/L for CBM, respectively. The standard deviations in the wastewater samples were also relatively low, indicating measurement stability.

Discussion

The legal acts currently in force in Poland do not regulate the permissible concentration values of pharmaceuticals in water. However, recent legislative measures at the EU level aim to include certain pharmaceuticals as parameters in water monitoring (Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/1307) and in establishing the quality of drinking water (Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2022, Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of December 16, 2020)61–63. Consequently, there is a growing interest in pharmaceuticals among researchers and water suppliers, who will need to adapt to new standards in the future to ensure adequate water quality. This will not be feasible without the implementation of optimal, fully validated qualitative analysis methods for the detection of pharmaceuticals in such diverse and complex matrices as water and wastewater, while simultaneously ensuring cost-effectiveness and environmental friendliness.

In response to this need, the present study developed, optimized, and validated an analytical method using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) without an evaporation step after SPE extraction, to determine the concentrations of investigated pharmaceuticals in riverine water and wastewater.

The method enables the determination of three compounds in a single analysis at low levels in complex matrices. The application of LC–MS/MS operating in the MRM mode, with three transitions monitored for each compound, provided excellent sensitivity and selectivity of detection according to the EU Commission Decision 2002/657/EC requiring a minimum of 3 IP for the confirmation of pharmaceuticals in environmental samples64.

The method’s validation parameters, evaluated in accordance with the ICH Q2(R2) guidelines53, confirmed its suitability for routine environmental analyses. The method proved to be specific (the retention times of pharmaceuticals in sample solution corresponded well to the standards) and linear (correlation coefficients for all substances ≥ 0.9999). The method’s precision, expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) below 5.0%, and its accuracy, with analyte recoveries ranging from 77 to 160%, are also within acceptable limits for trace pollutant analysis in complex matrices. The achieved LODs of 300 ng/L for CAF, 200 ng/L for IBU, and 100 ng/L for CBM, as well as LOQs of 1000 ng/L, 600 ng/L, and 300 ng/L, respectively, demonstrate the high sensitivity of the developed method. These low LOD and LOQ values are crucial for effective monitoring of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments, where their concentrations often occur at nanogram per liter levels or even lower.

The elimination of the evaporation step after SPE significantly reduced analysis time and solvent consumption, aligning with green chemistry principles and enhancing the method’s environmental friendliness and potential cost-effectiveness. The rapid 10-min analysis time increases sample throughput.

The environmental impact and analytical practicality of the developed UHPLC-MS/MS method for trace-level pharmaceutical monitoring were comprehensively evaluated using the AGREE and BAGI tools45. This dual assessment provides a holistic perspective on the method’s sustainability and its feasibility for routine applications.

The AGREE score for our UHPLC-MS/MS method was 0.64 (Fig. 5a), indicating a high level of greenness. This favorable result primarily stems from the reduction in analytical steps and shortened analysis time, leading to savings in materials, energy, and time. The proposed UHPLC-MS/MS method demonstrated a significant advantage over other reported chromatographic methodologies in terms of the number of steps, analysis duration, and reduced consumption of substantial amounts of organic solvents3,6,22,23,54,65. This implicitly suggests a competitive or superior greenness profile in these specific aspects. Regarding the aspects that lowered the AGREE score, the appearance of red zones (2 and 3) in the pictogram (Fig. 5a) indicates areas for improvement. These were primarily attributed to the sample size, the location of the analytical device, and the use of toxic reagents. Specifically, the AGREE assessment highlights the relatively large sample volume required. While the method generally exhibits high greenness, these factors represent specific limitations in achieving an even higher score.

The BAGI score of 80.0 (Fig. 5b) signifies a high degree of analytical practicality for our UHPLC-MS/MS method. This strong “blueness” score is mainly due to the nature of the analysis, the short analysis time, and the capability for simultaneous determination of multiple components from different compound classes. This last point makes the method a viable alternative to traditional methods used in the routine quality control of water and wastewater, which speaks to its competitiveness in terms of applicability and efficiency. Similar to the AGREE assessment, the aforementioned advantages–short analysis time and multi-component analysis–are key indicators of its strong practical utility compared to more traditional or less optimized methods. However, the analysis also acknowledges certain limitations that prevent an even higher BAGI score, including the necessity of manual sample collection, the relatively large sample volume required, and the costly extraction step. These aspects indicate areas where practicality could be further enhanced in future developments.

To verify the applicability of the developed and validated methodology under authentic environmental conditions and to identify potential challenges, the method was applied to real environmental water samples from the highly urbanized region of Kraków in southern Poland. This case study served as an integral part of assessing the method’s effectiveness and utility for environmental monitoring in a region impacted by industrial and urban activities. The obtained results (Table 5) serve as a crucial reference point for assessing their potential impact on the natural environment and human health.

Comparing the surface water concentrations obtained in this study with literature data (Table 6) some differences were observed.

Table 6.

Concentration of the selected pharmaceuticals in riverine waters and wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) in literature data.

| Compounds [ng/L] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample location | Caffeine (CAF) | Ibuprofen (IBU) | Carbamazepine (CBM) | References |

| Rivers | ||||

| Wisła River, Kraków, Poland | 326–1198 | 38 | 40 | 66,67 |

| Rudawa River, Kraków, Poland | 367–626 | 33 | 58 | 66,67 |

| Dłubnia River, Kraków, Poland | 370 | 10 | 47 | 66 |

| Wilga River, Kraków, Poland | 326 | – | – | 67 |

| Surface water, Poland | 113–5250 | 4–737 | 28–1840 | 68,69 |

| Surface water, UK | 55–199 | < 0.2–5044 | < 1–25 | 70 |

| Surface water, Germany | – | – | < 1–7100 | 70 |

| Surface water, France | 13–107 | ND–5 | ND–56 | 71 |

| Surface water, Spain | 12–416 | 6–2784 | 0.3–104 | 72 |

| Surface water, Greece | 38–72 | < LOQ | 92–186 | 73 |

| Surface water, Nigeria | < 4–1080 | 6720 | < 1–342 | 74 |

| Surface water, South Africa | 1170–60,530 | – | – | 74 |

| Surface water, China | 66–8571 | < LOD–195 | 1–30 | 8,75 |

| Surface water, Brazil | 200–14,820 | – | < 20–1590 | 54 |

| WWTPs | ||||

| Kraków WWTP influent | 2334–6768 | 666–3070 | 1452–3427 | 66 |

| Kraków WWTP effluent | < LOQ–1432 | 17–672 | 42–137 | 66 |

| WWTP Poland influent | 78,300–156,000 | 280–23,800 | 1120–2690 | 36,68 |

| WWTP Poland effluent | ND–364 | 0–110 | 1650–2240 | 36,68 |

| WWTP Greece influent | 856–6679 | < LOD–1258 | 326–1012 | 73 |

| WWTP Greece effluent | 28–119 | < LOD–790 | 172–552 | 73 |

| WWTP Jordan influent | 156,000 | – | 3138–3352 | 76 |

| WWTP Jordan effluent | 1560 | – | 2365–3020 | 76 |

| WWTP Canada influent | – | – | 3124 | 77 |

| WWTP Canada effluent | – | – | 2956 | 77 |

– lack of data.

Caffeine, a well-known indicator of recent municipal wastewater contamination, was detected in all investigated rivers, with concentrations ranging from 74 ± 5(Dłubnia) to 154 ± 4 ng/L (Serafa). Its high concentration in the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) influent (28,680 ± 3 ng/L) and significant reduction in the effluent (65 ± 3 ng/L) indicate effective elimination during wastewater treatment processes. However, its consistent presence in the rivers suggests continuous wastewater discharge. Although CAF is a readily biodegradable substance, its widespread occurrence in surface waters underscores the extent of anthropogenic pressure on Kraków’s aquatic environment. CAF concentrations in Kraków’s rivers are comparable to values observed in other urbanized areas in Poland and Europe, such as the Vistula River basin68 or German rivers70, confirming its role as a municipal pollution marker. While there are no specific regulatory standards for caffeine in surface waters, its ubiquitous presence highlights the need for general water quality management.

Ibuprofen was also present in all rivers, with concentrations ranging from 5 ± 3 (Prądnik) to 43 ± 8 ng/L (Drwina Długa). Similar to CAF, IBU is a widely used pharmaceutical, and its presence in environmental waters is strongly linked to wastewater discharges (WWTP influent: 7967 ± 7 ng/L). The reduction of IBU concentration in the WWTP effluent (15 ± 2 ng/L) indicates its partial biodegradability. However, its detectability in rivers emphasizes that conventional treatment methods cannot entirely remove this pharmaceutical. The relatively low precision observed for certain locations (e.g., Prądnik: 5 ± 3 ng/L, Drwina Długa: 43 ± 8 ng/L) might stem from concentrations close to the LOQ or from sample heterogeneity, which is typical for trace-level determinations. A comparison with other European studies, where IBU concentrations also fall within the ng/L to µg/L range57, confirms the widespread nature of this problem across Europe.

Carbamazepine exhibited relatively high concentrations in Kraków’s rivers, ranging from 14 ± 9 (Serafa) to 294 ± 2 ng/L (Drwina Długa). This is particularly significant as CBM is known for its high resistance to biodegradation and poor elimination in wastewater treatment plants (WWTP influent: 526 ± 1 ng/L; WWTP effluent: 330 ± 2 ng/L). The high relative standard deviation for Serafa (14 ± 9 ng/L, ~ 64%) might suggest variability in discharge sources or specific hydrological conditions at the sampling point, warranting further investigation. CBM is listed on the EU Watch List for priority substances in water 64, underscoring its potential environmental risk. Ecotoxicological data indicate that carbamazepine can have long-term, detrimental effects on aquatic organisms, including disrupting fish reproductive processes18. The concentrations detected in Kraków are consistent with reports from other regions in Poland and Europe70, confirming its ubiquitous and recalcitrant nature as a contaminant.

The observed high removal efficiency of CAF (99.9%) and IBU (78.9%) during the wastewater treatment process aligns with existing literature, which attributes this to their susceptibility to biodegradation and sorption in conventional treatment systems61,63,69,72. Conversely, the limited reduction in CBM concentration (37.3%) underscores the well-established challenges associated with the elimination of persistent pharmaceuticals using standard wastewater treatment technologies66,68,73,76, raising concerns regarding its potential long-term environmental impact78.

The discrepancies observed when comparing our results with historical data on the concentrations of the analyzed pharmaceuticals may reflect dynamic changes in the consumption patterns of these substances at the population level. The increased consumption of caffeine and the widespread use of ibuprofen in recent years could have contributed to the higher influent concentrations. Conversely, the lower carbamazepine concentration might be attributable to changes in prescribing practices or a more stable consumption within the population. However, the potential influence of the specific characteristics and efficiency of the unit processes employed at the investigated WWTP on the concentrations of the target analytes should also be considered.

Overall, the results from Kraków mirror the global trend of pharmaceutical presence in the aquatic environment. Pharmaceutical concentrations in the studied rivers are generally lower than in the WWTP influent, indicating some contaminant reduction. However, their continued presence highlights the need for more advanced wastewater treatment technologies and more effective management of pollution sources.

Based on the measured environmental concentrations (MEC) and the Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC) values provided by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission79, risk quotients (RQ = MEC/PNEC)80 were calculated for CAF, IBU, and CBM. A comprehensive assessment of the ecological relevance and potential health risks associated with these pharmaceuticals in river water and municipal wastewater is presented in the Supplementary Information (Table S3). This table includes a detailed risk classification, highlighting exceedances of PNEC values and environmentally relevant concentration levels.

The concentrations of CAF, IBU, and CBM measured in the rivers did not exceed the PNECs. The calculated risk quotients (RQs) for all three substances were significantly below 1 (0.002 for CAF, 0.14 for IBU, and 0.59 for CBM), indicating an unlikely ecological risk. These results suggest that the presence of these compounds in rivers does not pose an acute threat to aquatic organisms in the short term, which is consistent with studies from other similarly urbanized regions. The low RQ values in the rivers may be attributed to natural dilution and self-purification processes.

Significant increases in concentrations were observed in the municipal wastewater influent (WWTP influent), resulting in a change in risk classification. The measured concentrations of ibuprofen (MEC = 7.968 ng/L) and carbamazepine (MEC = 527 ng/L) exceeded their PNEC values. The calculated risk quotients (RQs) were 26.56 and 1.05, respectively, indicating a likely ecological risk in the untreated wastewater. These data confirm that municipal wastewater is the main source of these contaminants entering the environment.

The most important finding, however, is the high efficiency of the wastewater treatment process. After passing through the treatment plant (WWTP effluent), the concentrations of all tested compounds, including ibuprofen and carbamazepine, were reduced to levels where the risk quotient (RQ) dropped back below 1. This clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of the applied technologies in removing these pharmaceuticals and minimizing their negative impact on aquatic ecosystems.

A notable shift in risk profile was observed in the municipal wastewater influent (WWTP influent). Here, the measured concentrations of ibuprofen (MEC = 7.968 ng/L) and carbamazepine (MEC = 527 ng/L) exceeded their corresponding PNEC values, resulting in calculated risk quotients (RQs) of 26.56 and 1.05, respectively. This signifies a likely ecological risk in the untreated wastewater, confirming its role as a major source of pharmaceutical contamination. A key finding, however, is the high effectiveness of the wastewater treatment process. Following treatment (WWTP effluent), the concentrations of all studied compounds, including ibuprofen and carbamazepine, were reduced to levels where the RQ fell below 1, unequivocally proving the efficacy of the applied technologies in mitigating their negative impact on aquatic ecosystems.

While the primary objective of our study was not to assess human health risks (further research is anticipated), we considered available literature data80–82. Current pharmaceutical concentrations in rivers, such as those observed in our study (in the ng/L range), are typically significantly lower than concentrations that could pose a direct threat to human health through drinking water consumption or recreational activities. Standard drinking water treatment processes often effectively remove many of these compounds. However, long-term exposure to low concentrations, especially to mixtures of various pharmaceutical substances, is an actively researched area. The concentrations detected in our study provide valuable baseline data that can be used for further research assessing cumulative risk and for exposure modeling for public health risk assessment purposes.

Our approach distinguishes itself from many existing UHPLC-MS/MS protocols by offering significant advancements in green and blue analytical chemistry, efficiency, and robustness, which are crucial for routine environmental monitoring. A key innovation of our method is the omission of the evaporation/reconstitution step. Many conventional SPE methods coupled with LC–MS/MS methods for trace pharmaceutical analysis require an evaporation step after extraction, followed by reconstitution of analytes in a small volume of solvent. This step significantly contributes to organic solvent consumption and associated costs. By eliminating it, our method substantially reduces the use of hazardous solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) and related waste. This action fully aligns with the principles of green analytical chemistry, particularly concerning the reduction of energy consumption and minimization of hazardous substance use. Furthermore, omitting evaporation and reconstitution enhances time efficiency and reduces labor intensity. These steps are typically time-consuming and labor-intensive, often requiring specialized equipment such as nitrogen evaporators or vacuum concentrators. Their elimination streamlines sample preparation, significantly shortening the total analysis time per sample, which is critical for high-throughput environmental monitoring. Additionally, bypassing these steps minimizes analyte loss and contamination risk. The evaporation process can lead to the loss of more volatile compounds or those prone to adsorption onto laboratory glassware, while reconstitution introduces another potential source of error. By omitting these steps, our method improves overall analyte recovery and reduces variability, leading to higher accuracy and precision of results.

Our work is also distinguished by the explicit integration and quantitative assessment using AGREE (Analytical Greenness) and BAGI (Blue Analytical Greenness Index) metrics. This is a growing, though not yet universal, practice in environmental analytical chemistry. Our manuscript not only adopts these metrics but uses them to rigorously demonstrate and quantify the environmental benefits derived from our simplified approach, providing.

A tangible and comparable measure of our method’s sustainability performance relative to others. The application of both AGREE (which considers a broader environmental impact) and BAGI (focused on water consumption) ensures a holistic assessment of sustainability. Many studies focus solely on method parameters (LOD, LOQ) without explicitly quantifying their environmental footprint. Our work highlights how method design choices (such as omitting evaporation) directly translate into improved “greenness” and “blueness” scores, thereby promoting more sustainable analytical practices.

Moreover, despite simplification, i.e. omission of evaporation and internal standards, our method achieves robust performance at trace levels (ng/L) in diverse aqueous matrices from the Kraków area. This demonstrates that the benefits derived from increased efficiency do not compromise analytical quality, making the method suitable for routine monitoring. It is worth noting that many methods requiring internal standards often do so to mitigate significant matrix effects or extraction variability, which our optimized SPE procedure and direct injection approach successfully minimize. While numerous UHPLC-MS/MS methods exist for pharmaceutical monitoring, a significant portion still includes an evaporation/reconstitution step post-SPE. Examples include methods described in3,6,13,22,23,54. Although effective, these methods inherently involve higher solvent consumption and longer preparation times. Our approach stands out by demonstrating that for the specific analytes and matrices studied, this step can be safely omitted without compromising critical performance parameters, thus yielding a genuinely “greener” and more efficient protocol. The novelty of this work lies in the demonstrated feasibility and validated performance of this simplified, more sustainable workflow for a set of relevant environmental indicators.

In conclusion, the novelty and impact of our method stem from its validated effectiveness for trace pharmaceutical monitoring, achieved through a streamlined, “greener”/“bluer” process that critically omits the energy- and solvent-intensive evaporation step. This makes our protocol not only analytically sound but also environmentally responsible and more practical for routine application in environmental laboratories.

The high sensitivity and low analytical cost of the non-evaporative UHPLC-MS/MS method make it a promising tool for routine pharmaceutical monitoring in environmental waters. The data from this Kraków case study provide valuable insights into the current contamination status and can inform further research on the fate and effects of these pollutants in the local aquatic ecosystem. The method’s successful application to real samples from.

A heavily urbanized region confirms its robustness and utility for long-term water quality monitoring and evaluating pharmaceutical pollution reduction strategies. Given the growing problem of pharmaceutical pollution and upcoming legal regulations, the development and implementation of such methods is a key step in the effective monitoring and management of these pollutants. These actions also support the implementation of the European Commission’s recommendations regarding the reduction of pharmaceutical contamination83.

Future research should focus on expanding the application of this methodology to the analysis of other combinations of substances, replacing toxic reagents with safer alternatives, and developing automated sample collection procedures.

Conclusions

This study developed and validated an analytical method for the determination of selected pharmaceuticals in environmental samples using UHPLC-MS/MS, eliminating the need for evaporation after solid-phase extraction.

The presented methodology enables the concurrent quantification of carbamazepine, caffeine, and ibuprofen in aqueous and wastewater matrices, offering a significant asset for monitoring pharmaceutical occurrence in aquatic environments, a critical endeavor for ecotoxicological risk evaluation. Its accuracy, precision, and sensitivity were confirmed through comprehensive validation, following ICH guidelines, rendering it both efficient and reliable. Moreover, the successful application of this methodology to authentic polluted water and wastewater samples from the Kraków region substantiated its practical applicability and reliability. The detection of target analytes at concentrations reaching tens of nanograms per liter in these real-world samples underscores the tangible presence and environmental relevance of pharmaceutical contamination in this area.

The developed method not only enables tracking the migration pathways of pharmaceuticals within the environment and assessing the efficiency of wastewater treatment processes, but also, characterized by a short analysis time and minimal environmental impact, represents.

A step toward a more sustainable approach to environmental analysis. By potentially reducing the consumption of harmful substances and energy, it aligns with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and contributes to decreasing the negative environmental footprint of laboratory activities.

In conclusion, the evaluation using both AGREE and BAGI demonstrates that the developed UHPLC-MS/MS method offers a strong balance between environmental considerations and analytical practicality for the monitoring of trace-level pharmaceuticals. While areas for further greening exist, its current performance and advantages in terms of speed, reduced solvent consumption, and multi-analyte capability position it as a significant advancement in sustainable analytical chemistry for water quality assessment.

In future studies, the developed method can be extended to the analysis of additional pharmaceutical products and other important environmental pollutants, which will allow for.

A more comprehensive assessment of water quality. Furthermore, in order to further optimize and automate the analytical process, the method can be improved by integrating automation systems.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Research project partly supported by the program “Excellence initiative – research university” for the AGH University of Krakow (IDUB No.: 501 696 7996/L34, IDUB: 10674) and by the Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection at the AGH University of Krakow, Poland (No. 16.16.140.315).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., M.S. and E.S.; Data curation, M.K., and M.S.; Formal analysis, M.K., and M.S.; Funding acquisition, E.S. M.K.; Investigation, M.K., M.S. and E.S.; Methodology, M.K., and M.S.; Project administration, E.S. and M.K.; Resources, M.S. and M.K.; Software, M.K.; Supervision, E.S.; Validation, M.S. and M.K.; Visualization, M.K.; Writing—original draft, M.K., M.S., and E.S; Writing—review and editing, M.K., E.S., and M.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research project partly supported by the program “Excellence initiative – research university” for the AGH University of Krakow (IDUB No.: 501 696 7996/L34, IDUB: 10674) and by the Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection at the AGH University of Krakow, Poland (No. 16.16.140.315).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author M.K., on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shi, M. et al. Overview of sixteen green analytical chemistry metrics for evaluation of the greenness of analytical methods. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem.166, 117211. 10.1016/j.trac.2023.117211 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigues, F. et al. Pharmaceuticals in urban streams: A review of their detection and effects in the ecosystem. Water Res.268, 122657. 10.1016/j.watres.2024.122657 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kot-Wasik, A., Jakimska, A. & Śliwka-Kaszyńska, M. Occurrence and seasonal variations of 25 pharmaceutical residues in wastewater and drinking water treatment plants. Environ. Monit. Assess.10.1007/s10661-016-5637-0 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kózkal, B. & Bębas, K. Residues of pharmacologically active substances as environmental pollutants and the role of white rot fungi in their removal. Prospects Pharmaceut. Sci.19(5), 42–63 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Population Fund, World Population Dashboard https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population-dashboard (2024).

- 6.Alqarni, A. M. Analytical methods for the determination of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in solid and liquid environmental matrices: A review. Molecules29(16), 3900. 10.3390/molecules29163900 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham, V. L., Perino, Ch., D’Aco, V. J., Hartmann, A. & Bechter, R. Human health risk assessment of carbamazepine in surface waters of North America and Europe. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.56(3), 343–351. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.10.006 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou, H., Ying, T., Wang, X. & Liu, J. Occurrence and preliminary environmental risk assessment of selected pharmaceuticals in the urban rivers of China. Sci. Rep.7, 34928. 10.1038/srep34928 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calisto, V., Bahlmann, A., Schneider, R. J. & Esteves, V. I. Application of an ELISA to the quantification of carbamazepine in ground, surface, and wastewaters and validation with LC–MS/MS. Chemosphere84(11), 1708–1715. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.04.072 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikolaou, A., Meric, S. & Fatta, D. Occurrence patterns of pharmaceuticals in water and wastewater environments. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.387(4), 1225–1234. 10.1007/s00216-006-1035-8 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadutto, D., Andreu, V., Ilo, T., Akkanen, J. & Picó, Y. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in a Mediterranean coastal wetland: Impact of anthropogenic and spatial factors and environmental risk assessment. Environ. Pollut.271, 116353. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116353 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Commission. Legislative Observatory, European Parliament. Resolution on a strategic approach to pharmaceuticals in the environment. https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/en/procedurefile?reference=2019/2816RSP (2019)

- 13.Baranowska, I. & Kowalski, B. Using HPLC Method with DAD detection for simultaneous determination of 15 drugs in surface water and wastewater. Polish J. Environ. Stud.20(1), 21–28 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battaglin, W. A. et al. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, pesticides, and other bioactive contaminants in water, sediment, and tissue from Rocky Mountain National Park, 2012–2013. Sci. Total. Environ.643, 651–673. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.150 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bavumiragira, J. P., Ge, J. & Yin, H. Fate and transport of pharmaceuticals in water systems: A processes review. Sci. Total. Environ.823, 153635. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153635 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhandari, K. & Venables, B. Ibuprofen bioconcentration and prostaglandin E2 levels in the bluntnose minnow Pimephales notatus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol.153(2), 251–257. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.11.004 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson, J. et al. Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA119(8), e2213947119. 10.1073/pnas.2113947119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu, J. et al. Derivation of water quality criteria for carbamazepine and ecological risk assessment in the Nansi Lake Basin Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.19(17), 10875. 10.3390/ijerph191710875 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taibon, J. et al. An LC-MS/MS based candidate reference method for the quantification of carbamazepine in human serum. Clin. Chim. Acta472, 35–40. 10.1016/j.cca.2017.07.013 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.dePaula, J. & Farah, V. Caffeine consumption through coffee: content in the beverage, metabolism. Health Benefits Risks Beverages5(2), 37. 10.3390/beverages5020037 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirza, V. et al. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatographic method for quantitative determination of caffeine in different soft and energy drinks available in Bangladesh. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci.9(3), 1081–1089. 10.12944/CRNFSJ.9.3.33 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarcomnicu, I. et al. Simultaneous determination of 15 top-prescribed pharmaceuticals and their metabolites in influent wastewater by reversed-phase liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta83(3), 795–803. 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.10.045 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koçak, Ö. F. & Atila, A. Determination of ibuprofen in pharmaceutical preparations by UPLC-MS/MS method. Tr. Doğa ve Fen. Derg.11(2), 58–63. 10.46810/tdfd.1107889 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges, K. B. et al. LC–MS–MS determination of ibuprofen, 2-hydroxyibuprofen enantiomers, and carboxyibuprofen stereoisomers for application in biotransformation studies employing endophytic fungi. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.399(2), 915–925. 10.1007/s00216-010-4329-9 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gracia-Lor, E., Martínez, M., Sancho, J. V., Peñuela, G. & Hernández, F. Multi-class determination of personal care products and pharmaceuticals in environmental and wastewater samples by ultra-high performance liquid-chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta15, 1011–1023. 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.07.091 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gungor, S., Bulduk, I., Aydın, B. & Sağkan, R. I. A comparative study of HPLC and UV spectrophotometric methods for oseltamivir quantification in pharmaceutical formulations. Acta Chromatogr.34(3), 258–266. 10.1556/1326.2021.00925 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhawani, S. A., Fong, S. S. & Ibrahim, M. N. M. Spectrophotometric analysis of caffeine. Int. J. Anal. Chem.2015, 170239. 10.1155/2015/170239 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoaibi, Z. & Gouda, A. Extractive spectrophotometric method for the determination of tropicamide. J. Young Pharm.4(1), 42–48. 10.4103/0975-1483.93572 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gouda, A., Kotb, M. I., Kotb-El-Sayed, M. & Sayed Amin, A. Spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric methods for the determination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A review. Arab. J. Chem.6(2), 145–163. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.12.00 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damiani, P. C., Bearzotti, M. & Cabezón, M. A. Spectrofluorometric determination of naproxen in tablets. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.29(1–2), 229–238. 10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00063-8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghonim, R., Tolba, M. M., Ibrahim, F. & El-Awady, M. I. Smart green spectrophotometric assay of the ternary mixture of drotaverine, caffeine and paracetamol in their pharmaceutical dosage form. BMC Chem.17(1), 181. 10.1186/s13065-023-01097-9 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Kosasy, M., Tawakkol, S. M., Ayad, M. F. & Sheta, A. I. New methods for amlodipine and valsartan native spectrofluorimetric determination, with factors optimization study. Talanta143, 402–413. 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.05.012 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matkovic, S. R., Valle, G. M. & Briand, L. E. Quantitative analysis of ibuprofen in pharmaceutical formulations through FTIR spectroscopy. Lat. Am. Appl. Res.35, 189–195 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunha, R. R. et al. Simultaneous determination of caffeine, paracetamol, and ibuprofen in pharmaceutical formulations by high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection and capillary electrophoresis with conductivity detection. J. Sep. Sci.38(10), 1657–1662. 10.1002/jssc.201401387 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jankech, T. et al. Current green capillary electrophoresis and liquid chromatography methods for analysis of pharmaceutical and biomedical samples (2019–2023)–A review. Anal. Chim. Acta1323, 342889. 10.1016/j.aca.2024.342889 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Migowska, N., Caban, M., Stepnowski, P. & Kumirska, J. Simultaneous analysis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogenic hormones in water and wastewater samples using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and gas chromatography with electron capture detection. Sci. Total. Environ.441, 77–88. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.09.043 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cetin, A., Özbek, O. & Erol, A. Development of a potentiometric sensor for the determination of carbamazepine and its application in pharmaceutical formulations. J. Chem. Tech. Bio.98(4), 890–897. 10.1002/jctb.7292 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doumtsi, A. et al. A simple and green liquid chromatography method for the determination of ibuprofen in milk-containing simulated gastrointestinal media for monitoring the dissolution studies of three-dimensional-printed formulations. J. Sep. Sci.45(21), 3955–3965. 10.1002/jssc.202200444 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali, H. S., Abdullah, A. A., Pınar, P. T., Yardım, Y. & Şentürk, Z. Simultaneous voltammetric determination of vanillin and caffeine in food products using an anodically pretreated boron-doped diamond electrode: Its comparison with HPLC-DAD. Talanta170, 384–391. 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.04.037 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadad, G. M., Salam, R. A. A., Soliman, R. M. & Mesbah, M. K. Rapid and simultaneous determination of antioxidant markers and caffeine in commercial teas and dietary supplements by HPLC-DAD. Talanta101, 38–44. 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.08.025 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qureshi, T., Memon, N., Memon, S. Q. & Shaikh, H. Determination of ibuprofen drug in aqueous environmental samples by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry without derivatization. Am. J. M. Chromatogr.1, 45–54 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadkowska, J., Caban, M., Chmielewski, M., Stepnowski, P. & Kumirska, J. Environmental aspects of using gas chromatography for determination of pharmaceutical residues in samples characterized by different composition of the matrix. Arch. Environ. Protection43(3), 3–9. 10.1515/aep-2017-0028 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang, S. et al. Determination of eight pharmaceuticals in an aqueous sample using automated derivatization solid-phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Talanta136, 198–203. 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.11.071 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.IQVIA Commercial Consulting Sp. z o.o., API Prioritization Project, Final Report. https://smart.gov.pl/images/Projekt-API---Raport-kocowy.pdf (2023) (in Polish).

- 45.Hammad, S. F., Hamid, M. A., Adly, L. & Elagamy, S. H. Comprehensive review of greenness, whiteness, and blueness assessments of analytical methods. Green Anal. Chem.12, 100209. 10.1016/j.greeac.2025.100209 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/product/mm/102129?srsltid=AfmBOorpCSRc8ojuRzKXp7Yn_DQdxZN9-noiLbCIpJzyst2PAa1NthnR

- 47.Geoportal Krakówhttps://krakow.geoportal-krajowy.pl/statystyki-gus (2024).

- 48.Public Information Bulletin, City of Krakówhttps://www.bip.krakow.pl/?sub_dok_id=20375 (2025).

- 49.Waterworks of the City of Krakówhttps://wodociagi.krakow.pl/pl/o-firmie/infrastruktura/zaklad-oczyszczania-sciekow-plaszow (2025).

- 50.Waterworks of the City of Kraków https://wodociagi.krakow.pl/en/about-company/infrastructure/kujawy-sewage-treatment-plant (2025).

- 51.PN-EN ISO 5667–6:2016–12. Water Quality—Sampling—Part 6: Guidelines for Sampling Rivers and Streams. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland. (2016).