Abstract

Sonodynamic therapy (SDT) is a non-invasive alternative treatment for cancer. However, its effects on early-stage and intradermally implanted melanoma remain underexplored. Here, we investigated the in vivo effects of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA)-mediated SDT on early-stage murine cutaneous melanoma. Three comparative analyses were conducted to evaluate: (1) the efficacy of SDT on tumors at two distinct stages–Stage 1 and Stage 2–defined in this study based on Breslow depth: 1–1.5 mm for Stage 1 and 2.5–3 mm for Stage 2; (2) the therapeutic potential of combining SDT with photodynamic therapy (PDT) in Stage 1 tumors; and (3) the effectiveness of two ultrasound delivery approaches–via waveguide and direct contact. SDT induced significant tumor growth inhibition in Stage 1 (86.5%) and Stage 2 (72.5%) tumors compared to controls. The combination of SDT and PDT did not result in significantly greater tumor growth inhibition compared to SDT or PDT alone in Stage 1 tumors. ALA-mediated SDT thus demonstrates potential as a therapeutic strategy for early-stage cutaneous melanoma. However, under the conditions employed, combining SDT with PDT did not enhance therapeutic efficacy. Both waveguide-mediated and direct-contact ultrasound delivery proved effective for treating Stage 2 tumors, with waveguides offering advantages in anatomically challenging regions.

Keywords: Sonodynamic, Photodynamic, 5-aminolevulinic acid, Protoporphyrin IX, Melanoma

Subject terms: Skin cancer, Acoustics, Cancer, Cancer therapy

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma, a highly invasive and metastatic skin cancer originating in melanocytes, is the eighteenth most common cancer globally, according to the World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRFI) in 20241. In the United States, over 100,000 new cases of melanoma are expected in 2024, with a mortality rate exceeding 8%2. Melanoma is categorized into five clinical stages based on its progression. Stage 0, or in situ melanoma, is confined to the epidermis. Stage 1 melanoma is characterized by a Breslow depth–i.e., the distance from the skin surface to the deepest point of tumor invasion–of up to 2 mm, with or without ulceration, and no evidence of nodal or distant metastasis. Stage 2 involves tumors with a Breslow depth greater than 2 mm, again with no regional or distant spread. In both Stage 1 and Stage 2, the melanoma remains localized without evidence of lymphatic or distant dissemination, although tumor invasion may extend beyond the dermis into the subcutaneous tissue in more advanced cases. Stage 3 is defined by spread to regional lymph nodes or the presence of in-transit or satellite metastases. Stage 4 represents the most advanced disease, with distant metastasis to organs such as the lungs, liver, brain, or distant skin sites3. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for cutaneous melanoma; however, targeted therapy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of them is also employed for higher-risk stages4,5. These approaches generally achieve the highest success rates; however, they can be suboptimal and aggressive for the patient in some instances.6 Surgical intervention poses aesthetic challenges, treating tumors in sensitive areas, such as the face. Furthermore, the stress response induced by surgery can weaken immune function, potentially facilitating tumor progression or metastasis. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy may lead to the development of tolerance in cancer cells over prolonged treatment periods. Immunotherapy can cause a reduction in blood cell counts and skin-related issues6,7. These potential complications, coupled with the increasing costs of the treatments and the growing shortage of trained dermatologists, particularly in rural regions and developing countries, underscore the need for affordable and minimally invasive alternatives for melanoma treatment8.

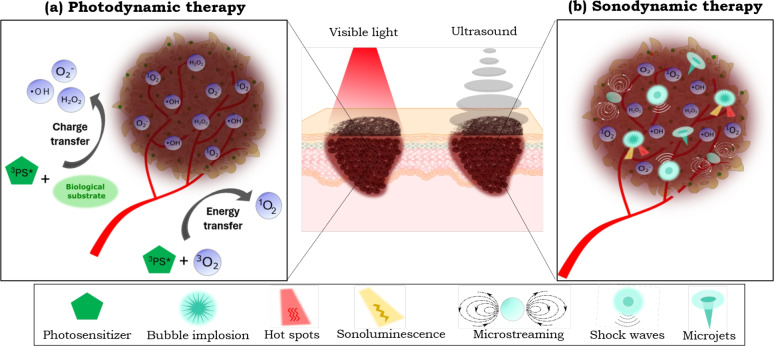

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a well-established cancer treatment with broad clinical applications. It relies on the interaction between a photoactive molecule known as a photosensitizer (PS), visible light, and molecular oxygen. This interaction generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which induce tumor cell death (Fig. 1-a)9,10. PDT is widely recognized for its effectiveness, particularly in treating non-melanoma skin cancer, such as basal cell carcinoma11,12. However, PDT’s efficacy is constrained in treating deep and pigmented tumors since melanin and other skin components attenuate the visible light penetration in biological tissue13–16. In the literature, interstitial PDT, which involves the use of optical fibers to deliver light directly into deep or internal tumors, has been investigated as a therapeutic approach for various cancer types17. However, its application in melanoma remains limited, likely due to the invasive nature of the procedure and the associated risk of promoting metastasis. To overcome the challenge of limited light penetration in melanoma, alternative strategies have been proposed, such as the use of optical clearing agents (OCAs) before PDT18,19, and multiphoton excitation techniques20. These methods are less invasive for enhancing PDT efficacy in melanoma treatments.

Fig. 1.

(a) Mechanisms of ROS generation by photodynamic therapy: “Type I mechanism” refers to a charge transfer from the PS in the excited triplet state ( ) to the biological substrate leading to the formation of ROS such as superoxide anions (

) to the biological substrate leading to the formation of ROS such as superoxide anions ( ), hydrogen peroxide (

), hydrogen peroxide ( ) and hydroxyl radicals (

) and hydroxyl radicals ( ), “Type II mechanism” involves energy transfer between the (

), “Type II mechanism” involves energy transfer between the ( ) and the molecular oxygen (

) and the molecular oxygen ( ). (b) The potential action mechanisms of sonodynamic therapy triggered by acoustic cavitation include mechanical forces (such as microstreaming, microjets, and shock waves) and ROS production by sonoluminescence and hot spots.

). (b) The potential action mechanisms of sonodynamic therapy triggered by acoustic cavitation include mechanical forces (such as microstreaming, microjets, and shock waves) and ROS production by sonoluminescence and hot spots.

Another minimally invasive method that has emerged as an alternative anticancer technique is the sonodynamic therapy (SDT). SDT combines low-intensity (generally unfocused) ultrasound with sonoactive molecules, known as sonosensitizers (SS), within an oxygenated environment12. This interaction induces sonomechanical and sonochemical effects such as physical disruption of cellular membranes and ROS production, respectively, ultimately leading to targeted cell death21–24. These therapeutic effects are attributed to the activation of the SS via acoustic cavitation, a well-known phenomenon induced by ultrasound irradiation (Fig. 1-b)24,25. Ultrasound, a mechanical wave widely employed in deep-tissue imaging, offers excellent tissue penetration capabilities, independent of melanin content12,26. Consequently, its application as an energy source in SDT presents significant potential for treating deep-seated and pigmented tumors.

Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated that SDT induces effectively cytotoxic effects in various cancers and influences the modulation of the immune response within the tumor microenvironment27–31. Although the precise mechanisms underlying SS sonoactivation have not been fully understood, clinical trials for glioblastoma are currently underway, showing significant clinical potential32–35. To date, no clinical trials have been reported evaluating the therapeutic potential of SDT for treating human cutaneous melanoma. Nevertheless, the efficacy of SDT has been investigated in both in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies36–44. Despite these efforts, certain aspects remain underexplored, including the treatment of early-stage tumors and intradermal-implanted cutaneous melanoma.

On the other hand, as an emerging therapy, SDT lacks standardized protocols for ultrasound irradiation, resulting in considerable variability across experimental setups in previous and ongoing preclinical studies. For example, some studies have used tanks filled with ultrapure water for submerging animals during sonication, which is impractical for clinical applications45. Other approaches for acoustic coupling reported in in vitro and in vivo SDT studies include the use of tissue layers, as well as tubes, bags, or cones filled with degassed water28,31,46–52. Also, waveguides, such as aluminum cones with specific profiles, have been applied for SDT application53–56. However, the pros and cons of each approach are rarely discussed, hindering the direct comparison of the SDT outcomes. Therefore, developing an effective SDT protocol with a clinically feasible, efficient, and simplified ultrasound delivery configuration is crucial for advancing the clinical translation of SDT.

A combination of SDT and PDT has recently emerged as a potentially synergistic approach, called sonophotodynamic therapy (SPDT). SPDT integrates the mechanisms of both modalities, leveraging the benefits of ultrasound and light activation to achieve superior tumor control. Preclinical studies on various cancer models (e.g., murine breast, human breast, prostate, murine ovary, human liver, squamous cell carcinoma, Ehrlich ascites carcinoma and brain cancer)27,46 and clinical trials on internal tumors (e.g., bowel and ovarian cancer)57–60 and metastatic tumors61,62 have been investigated. However, regarding melanoma specifically, only one previous in vitro study has been identified, which showed enhanced cytotoxicity in human melanoma cells when PDT and SDT were combined63. Beyond oncology, SPDT has also shown promise as an antimicrobial strategy, exhibiting synergistic effects through combined photo-sonodynamic action64.

One approach to enhance the singlet oxygen quantum yield of free organic SS is encapsulating it in nanocarriers, such as liposomes, micelles, nanoparticles, or metal-organic frameworks31,43,65,66. Another approach involves synthesizing organometallic compounds or inorganic nanomaterials67–69. As a result, developing new sensitizers has become an area of increasing interest and research. However, concerns about non-biodegradability and potential biosafety risks highlight the need for further investigations to assess their suitability for clinical applications23. The protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) is an endogenous porphyrin and a Heme precursor widely utilized as a PS70. Several studies have demonstrated that PpIX can also be activated by ultrasound, supporting its dual application as a PS and SS55,71,72. Besides, the detection of ROS generation, through indirect techniques (e.g., chemical probes and electron paramagnetic resonance), during PpIX-mediated PDT and SDT has been reported31,48,73–75.

Due to the altered metabolism of tumor cells, there is an increased production and accumulation of endogenous PpIX in tumor cells; however, endogenous levels of PpIX are insufficient for a successful dynamic treatment. To enzymatically increase the concentration of PpIX, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), a PpIX precursor, is administered. This approach bypasses the negative feedback mechanisms of the heme biosynthesis pathway, resulting in the preferential accumulation of PpIX in tumor cells76,77. The use of ALA in dynamic therapies is very convenient, as it was approved for clinical use in Europe in 2001 and the United States in 1999 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)78,79. Additionally, in vivo studies have shown that ALA-based SDT induces ROS generation, effectively contributing to tumor growth inhibition in melanoma models14,45,80–82.

In this study, we investigated the in vivo effects of ALA-mediated SDT on early-stage, intradermally implanted melanoma – a setting that remains largely unexplored in the current literature. To closely model clinical melanoma progression, tumors were classified by Breslow depth: 1–1.5 mm for Stage 1 and 2.5–3.0 mm for Stage 2. The tumor model was established via intradermal implantation of B16-F10 cells into the right flank of female athymic Nu/J nude mice. This study addresses important but insufficiently characterized aspects of SDT and its integration with PDT. Specifically, we designed three comparative studies to investigate: (1) the stage-dependent efficacy of SDT on early-stage tumors; (2) the therapeutic potential of combining SDT with PDT in Stage 1 tumors; and (3) the comparative performance of two ultrasound delivery approaches–a conical aluminum waveguide, designed to concentrate ultrasound energy within the target tissue and to match the irradiation area to the tumor dimensions, versus direct transducer contact - the conventional method. Another feature of this study is the use of high-resolution ultrasonography for non-invasive, longitudinal monitoring of tumor depth and volume, enabling precise quantification of tumor growth dynamics in response to each treatment modality. This continuous imaging approach provided deeper insight into treatment effects beyond conventional endpoint measurements. In addition, the therapeutic interaction between SDT and PDT was quantitatively assessed using combination index analysis. Three days post-treatment, animals were euthanized and tumors were harvested for histological evaluation. By integrating stage-specific analysis, advanced ultrasound-based monitoring, and a direct comparison of ultrasound delivery strategies, this study offers new insights to guide the practical optimization of SDT for translational melanoma therapy.

Results

Acoustic measurements

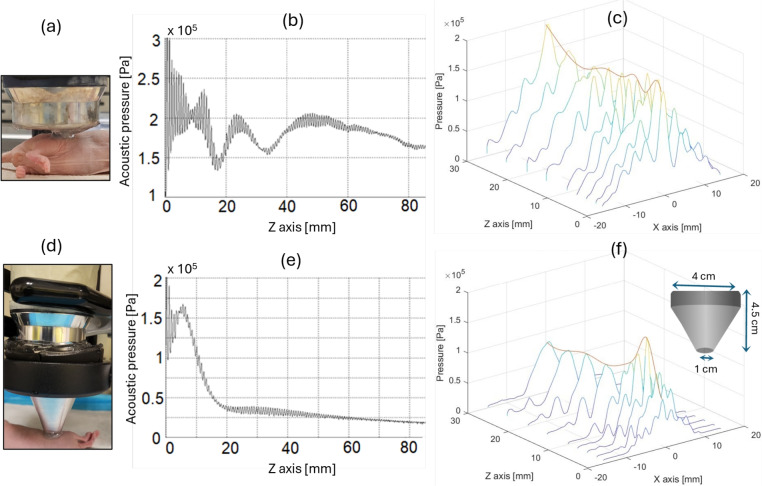

The large-area probe (Fig. 2-a) was positioned at the point (x, y, z) = (0, 0, 0) within the scanning tank, and the hydrophone was initially placed near the center of the head to start data collection. Figure 2-b and the orange line in Fig. 2-c show the acoustic pressure profile mapped along the z-axis. This profile indicates that the acoustic pressure oscillates around 2 Pa up to z=50 mm, beyond which it gradually decreases as the beam diameter expands and its energy dissipates. The region near the ultrasound source, extending up to z=50 mm, constitutes the near field of the acoustic field, whereas the region beyond z=50 mm represents the far field. This is the standard beam profile of a plane wave ultrasound transducer83. Fig. 2-c shows a set of acoustic pressure profiles along the x-axis for some points in the z-axis. These profiles demonstrate that the ultrasound irradiation is concentrated within the region from x=-13 mm to x=13 mm. This range aligns with expectations, as the equipment’s effective radiation area (ERA) is 5  , corresponding to an effective radiation diameter of 2.5 cm. As a result, ultrasound irradiation directly over the tumor area could only be performed in animals with stage 2 tumors since the tumor extended above the skin’s plane. This allowed for selective tumor irradiation while avoiding contact between the transducer and the surrounding skin, as shown in Fig. 2-a.

, corresponding to an effective radiation diameter of 2.5 cm. As a result, ultrasound irradiation directly over the tumor area could only be performed in animals with stage 2 tumors since the tumor extended above the skin’s plane. This allowed for selective tumor irradiation while avoiding contact between the transducer and the surrounding skin, as shown in Fig. 2-a.

Fig. 2.

Acoustic field generated by ultrasound irradiation (continuous wave, 1MHz, 1 W/ ) using (a) the large-area probe (ERA: 5

) using (a) the large-area probe (ERA: 5  ) of the ultrasound machine, and (d) the probe coupled with a conical aluminum waveguide. (b,e) Acoustic pressure profiles mapped along the z-axis at x,y=0. (c,f) Acoustic pressure profiles mapped at the x-axis, y=0, and some points along the z-axis.

) of the ultrasound machine, and (d) the probe coupled with a conical aluminum waveguide. (b,e) Acoustic pressure profiles mapped along the z-axis at x,y=0. (c,f) Acoustic pressure profiles mapped at the x-axis, y=0, and some points along the z-axis.

In order to optimize and develop SDT protocols for treating skin-related diseases, it was crucial to concentrate the maximum ultrasound intensity along the target lesion. The use of waveguides for applying SDT has been previously reported53–56, so a conical aluminum waveguide was designed for this study and coupled to the transducer. The larger face, measuring 4 cm in diameter, was fitted to the transducer head, while the smaller face, measuring 1 cm in diameter, was adjusted to irradiate early-stage tumors (Fig. 2-d). Figure 2-e and the orange line in Fig. 2-f show the acoustic pressure profile mapped along the z-axis corresponding to this new configuration. The standard profile of acoustic pressure changed to a decreasing pattern along the propagation path. This profile indicates that the acoustic pressure oscillates around 1.5 Pa up to z=10 mm, beyond which it drops to zero. Consequently, the highest pressure amplitude was transmitted near the small-diameter face of the waveguide, corresponding to the location of the tumor target region in the in vivo experiments. It was also observed that using the waveguide, the acoustic pressure resulted in approximately a 25% reduction compared to that delivered without the waveguide. Figure 2-f shows a set of acoustic pressure profiles along the x-axis for some points in the z-axis. These profiles show that the ultrasound irradiation is concentrated within the region from x=-5 mm to x=5 mm, corresponding to an ERA of 0.8  . This range enables targeted irradiation of a small tumor region while minimizing exposure to the surrounding healthy tissue.

. This range enables targeted irradiation of a small tumor region while minimizing exposure to the surrounding healthy tissue.

Introducing the waveguide, the standard spatial propagation profile of ultrasound was modified, focusing the acoustic energy on more superficial layers (approximately 1 cm in depth) where our cutaneous melanoma model is located. The following sections will explore the effects of SDT in treating a murine model of cutaneous melanoma with and without using the conical aluminum waveguide.

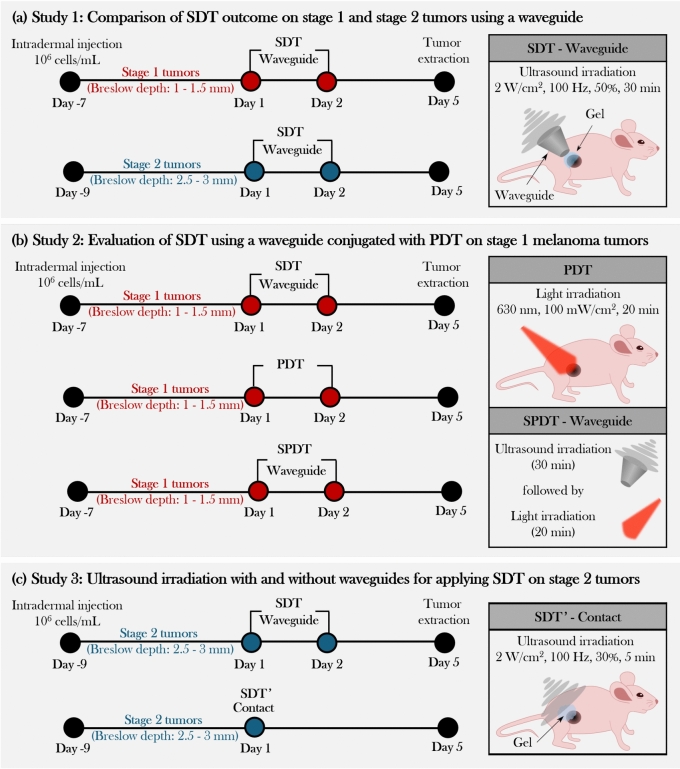

Study 1: comparison of SDT outcome on stage 1 and stage 2 tumors using a waveguide

As illustrated in Fig. 3-a, mice bearing cutaneous melanoma tumors at two different progression stages were treated using a standardized SDT protocol. This protocol consisted of two sonodynamic therapy sessions administered 24 hours apart. 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) was administered daily, three hours prior to each ultrasound application ((2 W/ , 100 Hz, 50%, 30 min each day). Figure S7 shows the PpIX fluorescence across the entire skin of the animals, confirming successful photosensitizer accumulation under these standardized conditions. Although the same administration protocol was used for both tumor stages, the actual generation and distribution of PpIX likely varied according to the physiological characteristics of each animal-tumor. Notably, under these ultrasound parameters and timing, this protocol proved to be the most effective in controlling tumor growth among the initial pilot tests conducted (data not shown).

, 100 Hz, 50%, 30 min each day). Figure S7 shows the PpIX fluorescence across the entire skin of the animals, confirming successful photosensitizer accumulation under these standardized conditions. Although the same administration protocol was used for both tumor stages, the actual generation and distribution of PpIX likely varied according to the physiological characteristics of each animal-tumor. Notably, under these ultrasound parameters and timing, this protocol proved to be the most effective in controlling tumor growth among the initial pilot tests conducted (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Three main studies for assessing ALA-based treatment of murine cutaneous melanoma under different conditions: (a) SDT with waveguide with two initial tumor stages, (b) combining SDT waveguide with PDT, and (c) two ultrasound delivery methods, using a waveguide and in contact.

Figure S1-a shows the daily standard photographs of the right flank of mice bearing stage 1 and stage 2 tumors, respectively. Mice in the ultrasound groups displayed only mild effects on the skin overlying the tumor. In contrast, mice in the SDT groups exhibited visible damage within the sonication area, rising partially into the surrounding irradiation region. Figure 4 presents the ultrasonography images captured on Days 1–5 for the studies with stage 1 and 2 tumors (ultrasound images for all animals are also provided in the Supplemental Material). The control groups in both cases exhibit progressive growth over the days while maintaining an elliptical shape. The epidermis/dermis, the intradermal tumor, and the panniculus carnosus layer beneath the tumors are distinguishable. In both cases, the tumors in the ultrasound groups maintained an elliptical shape; however, mild alterations were observed in the skin overlying the tumor. Besides, a change in tumor density was observed after ultrasound irradiation of stage 2 tumors, as indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 4. This is reflected by the image’s color shift from a light gray shade (denser area, ex., tissue or bones) to a darker shade (less dense area, ex., fluid-filled areas). The SDT groups exhibited noticeable deformation of the skin overlying the tumor, swelling of the skin surrounding the sonication area, structural alterations of the tumor (evidenced by the loss of its initially elliptical shape), and reduced tumor density after treatment, indicated by the central area of the tumor appearing darker.

Fig. 4.

Representative ultrasound images of tumors at days 1-5 for the experimental groups of the Study 1, 2, and 3. The arrows indicate the color shift observed on the tumor ultrasonography. The tumor region appears as a light gray shade before treatment and becomes darker after treatment. (Scale bars: 1.5 mm).

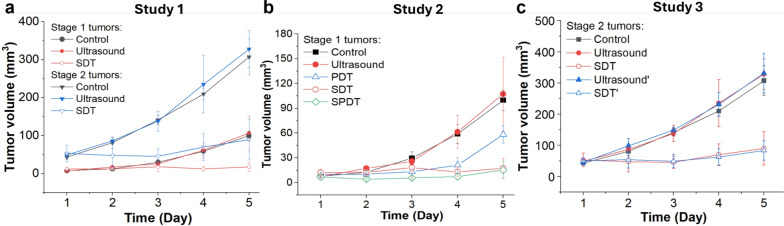

As shown in Fig. 5-a, the mean tumor volume at the endpoint was 100 ± 12, 107 ± 45, 18 ± 12  for the control, ultrasound, and SDT groups of stage 1 tumors, respectively. While, for stage 2 tumors, it was 307 ± 47, 328 ± 49, and 90 ± 54

for the control, ultrasound, and SDT groups of stage 1 tumors, respectively. While, for stage 2 tumors, it was 307 ± 47, 328 ± 49, and 90 ± 54  , respectively. The tumor volume growth in both stage 1 and stage 2 tumors treated with SDT was significantly reduced compared to their corresponding control groups, indicating the therapeutic efficacy of sonodynamic therapy in inhibiting tumor progression. On the other hand, it was observed that for certain animals with stage 1 tumors, the tumor volume at the endpoint in the ultrasound group was slightly larger than that in the control group (Figure S1-b). It could be attributed to a biomodulation effect triggered by sonication under the ultrasound conditions used in this study. Specifically, it suggests that a low amount of ROS generated during sonication may be sufficient to stimulate the tumor cells, potentially leading to faster growth. An example of such effects is photobiomodulation, where light irradiation induces similar cellular responses84–86. However, the normalized tumor volume growth curve in the control and ultrasound groups did not present a statistical difference (Figure S2-a). The potential effect of sonobiomodulation was not observed in the ultrasound group of the stage 2 tumor study, possibly due to a higher degree of hypoxia in the tumors, which may prevent these effects from influencing the tumor growth rate (Figure S1-b).

, respectively. The tumor volume growth in both stage 1 and stage 2 tumors treated with SDT was significantly reduced compared to their corresponding control groups, indicating the therapeutic efficacy of sonodynamic therapy in inhibiting tumor progression. On the other hand, it was observed that for certain animals with stage 1 tumors, the tumor volume at the endpoint in the ultrasound group was slightly larger than that in the control group (Figure S1-b). It could be attributed to a biomodulation effect triggered by sonication under the ultrasound conditions used in this study. Specifically, it suggests that a low amount of ROS generated during sonication may be sufficient to stimulate the tumor cells, potentially leading to faster growth. An example of such effects is photobiomodulation, where light irradiation induces similar cellular responses84–86. However, the normalized tumor volume growth curve in the control and ultrasound groups did not present a statistical difference (Figure S2-a). The potential effect of sonobiomodulation was not observed in the ultrasound group of the stage 2 tumor study, possibly due to a higher degree of hypoxia in the tumors, which may prevent these effects from influencing the tumor growth rate (Figure S1-b).

Fig. 5.

Tumor growth curves depicting the mean tumor volume over time corresponding to (a) Study 1, (b) Study 2, and (c) Study 3. Ultrasound irradiation methods: A waveguide was used in the ultrasound, SDT, and SPDT groups; while just coupling gel was used in the ultrasound’ and SDT’ groups.

As shown in Fig. 6-a, the tumor growth inhibition ratio in the SDT group of stage 1 tumors and stage 2 tumors was 86.51% (p 0.01 vs control) and 72.53% (p

0.01 vs control) and 72.53% (p 0.05 vs control), respectively. Both tumor stages responded well to SDT, with comparable levels of growth inhibition. The mean tumor inhibition ratio of SDT was slightly higher in Stage 1 tumors than in Stage 2 tumors. The minor difference observed may reflect anatomical and physiological variations between tumor stages. Larger Stage 2 tumors are more likely to develop hypoxic regions, which could modestly reduce the efficacy of ROS-mediated treatments such as SDT. Additionally, the penetration of ALA and subsequent PpIX accumulation may be less uniform in larger tumors. Nevertheless, these factors did not result in a statistically significant difference in treatment outcome between Stage 1 and Stage 2 tumors under the conditions tested. There was no remarkable difference in body weight between experimental groups (Figure S4-a).

0.05 vs control), respectively. Both tumor stages responded well to SDT, with comparable levels of growth inhibition. The mean tumor inhibition ratio of SDT was slightly higher in Stage 1 tumors than in Stage 2 tumors. The minor difference observed may reflect anatomical and physiological variations between tumor stages. Larger Stage 2 tumors are more likely to develop hypoxic regions, which could modestly reduce the efficacy of ROS-mediated treatments such as SDT. Additionally, the penetration of ALA and subsequent PpIX accumulation may be less uniform in larger tumors. Nevertheless, these factors did not result in a statistically significant difference in treatment outcome between Stage 1 and Stage 2 tumors under the conditions tested. There was no remarkable difference in body weight between experimental groups (Figure S4-a).

Fig. 6.

Statistical analysis of the tumor growth inhibition ratio (%) induced by (a) SDT protocol of Study 1, (b) PDT, SDT, and SPDT protocols of Study 2, and (c) SDT’- contact protocol of Study 3. US: ultrasound.

0.05 was considered statistically significant.

0.05 was considered statistically significant.

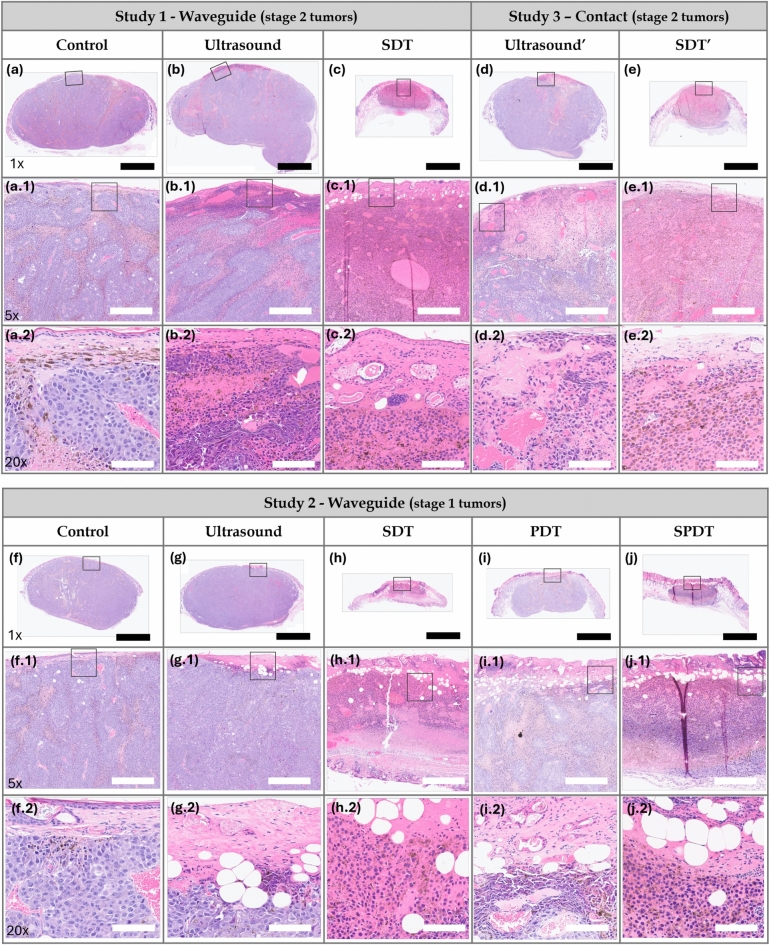

Figure 7 shows the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-staining of tumors collected on Day 5 for each experimental group. The slides presented at 1x magnification depict the complete cross-sectional area of the tumors along the irradiation axis, thereby illustrating the depth of damage induced by the studied protocols. The slides at 5x and 20x magnification display a better visualization of the damage. We observed that in the control groups of animals with stage 2 (Fig. 7-a, a.1, a.2) and stage 1 (Fig. 7-f, f.1, f.2) tumors, the epithelial tissue was preserved. The boundary between the epithelium and the tumor region was distinguishable compared to the treated groups. H& E staining exhibited islands of autonecrosis, which were more pronounced in the stage 2 tumor group. Regions containing melanin and blood vessels were additionally identified. In the ultrasound groups of mice with stage 2 (Fig. 7-b, b.1, b.2) and stage 1 (Fig. 7-g, g.1, g.2) tumors, the epithelial tissue was observed to be preserved but disorganized. A necrotic region was identified in the epithelial tissue and the most superficial areas of the tumor. This was attributed to the ultrasound mechanical effects generated under the applied sonication parameters. The tissue appeared friable, and inflammatory infiltrates were detected adjacent to the necrotic regions. The tumors also exhibited islands of autonecrosis dispersed throughout the cross-sectional area, resembling those observed in the control group. The stage 2 (Fig. 7-c, c.1, c.2) and stage 1 (Fig. 7-h, h.1, h.2) tumors treated with SDT showed disorganized epithelial tissue with points of ulceration. The necrotic area encompassed nearly the entire cross-sectional region for both tumor stages. Inflammatory infiltrates adjacent to the necrotic zones, as well as blood vessel extravasation, were also observed in both cases. These results suggest that the induction of sonodynamic damage at depth was achievable even in the thicker tumors.

Fig. 7.

Study 1: Histological H&E staining images of Stage 2 tumors in (a,a.1,a.2) control, (b,b.1,b.2) ultrasound, and (c,c.1,c.2) SDT groups. Study 3: Histological H&E staining images of Stage 2 tumors in (d,d.1,d.2) ultrasound’ and (e,e.1,e.2) SDT’ groups. Study 2: H&E stained slide of Stage 1 tumors in (f,f.1,f.2) control, (g,g.1,g.2) ultrasound, (h,h.1,h.2) SDT, (i,i.1,i.2) PDT and (j,j.1,j.2) SPDT groups. Black bar=2.5 mm (1x magnification). White bar=500  m (5x magnification) and 100

m (5x magnification) and 100  m (20x magnification). The black square delineates the region displayed at 5x and 20x magnification.

m (20x magnification). The black square delineates the region displayed at 5x and 20x magnification.

The temperature of the tumor-overlying skin, in contact with the small end face of the waveguide and a coupling gel layer, increased by up to  C during the final 5 minutes of ultrasound irradiation. As a result, it was concluded that the damage observed in the ultrasound and SDT groups may be attributed to thermal effects to a minimal extent.

C during the final 5 minutes of ultrasound irradiation. As a result, it was concluded that the damage observed in the ultrasound and SDT groups may be attributed to thermal effects to a minimal extent.

Study 2: evaluation of SDT using a waveguide conjugated with PDT on stage 1 melanoma tumors

Study 2 aimed to evaluate the therapeutic potential of combining SDT with PDT in Stage 1 tumors, as shown in Fig. 3-b.

Figure S5-a presents the daily collected standard photographs of the right flank of mice treated with SDT, PDT, and SPDT. Mice exhibited visible damage on the skin overlying the tumor for SDT, PDT, and SPDT, and skin swelling in the right flank of mice after PDT and SPDT. The ultrasonography images (Fig. 4) of the treated groups, PDT, SDT, and SPDT, displayed a significant reduction in the tumor volume at the endpoint compared to the control groups. Additionally, damage to the stratum corneum and epidermis overlying the tumor, skin swelling in the surrounding tumor area, and alterations in the tumor structure (more pronounced in the SDT and SPDT groups) were observed. Similar to the treated groups in Study 1, the tumors in the PDT and SPDT groups also exhibited a reduction in density (visualized as darker shades on tumor ultrasonography), as indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 4.

As shown in Fig. 5-b, the mean tumor volume at the endpoint was  , and

, and

for the control, ultrasound, PDT, SDT, and SPDT groups, respectively. This indicates that the tumor volume growth induced in PDT, SDT, and SPDT groups was significantly reduced compared to the control groups (Figure S5-b). The mean tumor volume at the endpoint obtained in SDT and SPDT groups was considerably smaller than that in PDT group; however, no statistically significant difference was observed between the SPDT and SDT groups (Figure S2-b). As shown in Fig. 6-b, the tumor growth inhibition ratio in SDT, PDT, and SPDT groups was 86.51% (p

for the control, ultrasound, PDT, SDT, and SPDT groups, respectively. This indicates that the tumor volume growth induced in PDT, SDT, and SPDT groups was significantly reduced compared to the control groups (Figure S5-b). The mean tumor volume at the endpoint obtained in SDT and SPDT groups was considerably smaller than that in PDT group; however, no statistically significant difference was observed between the SPDT and SDT groups (Figure S2-b). As shown in Fig. 6-b, the tumor growth inhibition ratio in SDT, PDT, and SPDT groups was 86.51% (p 0.001 vs control, p

0.001 vs control, p 0.05 vs PDT), 53.08% (p

0.05 vs PDT), 53.08% (p 0.001 vs control), and 79.18% (p

0.001 vs control), and 79.18% (p 0.001 vs control), respectively. The tumor growth inhibition ratio (TGI%) generated by SDT was higher than that induced by PDT; however, no statistically significant difference was observed between TGI (%) of SDT and SPDT. Based on the Bliss independence model, the expected additive effect was 93.65%. Since this value is higher than the observed effect of SPDT (79.18%), the combination index (CI) was found to be less than 1, indicating an antagonistic interaction when combining SDT and PDT. There was no remarkable difference in body weight between experimental groups (Figure S3-b).

0.001 vs control), respectively. The tumor growth inhibition ratio (TGI%) generated by SDT was higher than that induced by PDT; however, no statistically significant difference was observed between TGI (%) of SDT and SPDT. Based on the Bliss independence model, the expected additive effect was 93.65%. Since this value is higher than the observed effect of SPDT (79.18%), the combination index (CI) was found to be less than 1, indicating an antagonistic interaction when combining SDT and PDT. There was no remarkable difference in body weight between experimental groups (Figure S3-b).

Figure 7-f,f.1,f.2, Fig. 7-g,g.1,g.2 and Fig. 7-h,h.1,h.2 show the H&E-staining of stage 1 tumors of the control, ultrasound, and SDT groups discussed in Study 1. In the PDT group (Fig. 7-i, i.1, i.2), the epithelial tissue exhibited disorganization and some points of erosion. In contrast to the SDT group, regions of necrosis and inflammatory infiltrates were located close to the epithelial tissue, indicating that photodynamic effects were concentrated in the superficial layers. Additionally, the tumors displayed islands of autonecrosis dispersed throughout the cross-sectional area, similar to those observed in the control group. Figure 7-j, j.1, j.2 show the slides of SPDT group where the epithelial tissue exhibited marked disorganization with points of ulceration. Similar to the SDT groups, regions of necrosis and inflammatory infiltrates generated by the treatment were present throughout the cross-sectional area of irradiation. The temperature of the tumor-overlying skin, in contact with the small end face of the waveguide and a coupling gel layer, increased by up to  C during the final 5 minutes of ultrasound irradiation and

C during the final 5 minutes of ultrasound irradiation and  C during light irradiation. As a result, the thermal effects induced by light irradiation were disregarded, and the damage observed in the ultrasound, SDT, and SPDT groups was attributed primarily to sonodynamic effects, with minimal influence from thermal effects.

C during light irradiation. As a result, the thermal effects induced by light irradiation were disregarded, and the damage observed in the ultrasound, SDT, and SPDT groups was attributed primarily to sonodynamic effects, with minimal influence from thermal effects.

Study 3: ultrasound irradiation with and without waveguides for applying SDT on stage 2 tumors

The effectiveness of the SDT protocol using a waveguide, employed in the previous studies, was compared to a new SDT protocol (1 MHz, 2 W/ , pulsed mode, 30%, 100 Hz, 5 min - single application) for stage 2 tumor treatment, shown in Fig. 3-c. The new SDT-contact protocol was not applied to treating the stage 1 tumors due to their flatter morphology, as these tumors did not protrude significantly from the skin’s surface. In contrast, the stage 2 tumors, which extended above the skin’s plane, allowed for targeted ultrasound irradiation of the tumors while protecting the surrounding skin, making SDT-contact a viable method for these cases.

, pulsed mode, 30%, 100 Hz, 5 min - single application) for stage 2 tumor treatment, shown in Fig. 3-c. The new SDT-contact protocol was not applied to treating the stage 1 tumors due to their flatter morphology, as these tumors did not protrude significantly from the skin’s surface. In contrast, the stage 2 tumors, which extended above the skin’s plane, allowed for targeted ultrasound irradiation of the tumors while protecting the surrounding skin, making SDT-contact a viable method for these cases.

Standard photographs of the right flank of mice treated with SDT in contact, the control groups, and the extracted tumor at the endpoint are shown in Figure S6-a. In the ultrasound group, mice exhibited mild effects on the skin overlying the tumor. Mice in the SDT group demonstrated visible surface damage and a significant reduction in tumor volume compared to the control group. The ultrasonography images of each experimental group are shown in Fig. 4. In the ultrasound’ group, no substantial changes in tumor structure were observed; however, some alterations were observed in the skin overlying the tumor compared to the control group. In the SDT’ group, damage on the skin overlying the tumor, skin swelling in the surrounding tumor area, and alterations in tumor structure were observed. A reduction in tumor density after treatment was observed in both the Ultrasound’ and SDT’ groups, as indicated by the darker areas on ultrasonography (highlighted by white arrows in Fig. 4).

Figure 5-c shows that the mean tumor volume at the endpoint was  , 328 ± 49,

, 328 ± 49,  ,

,  , and

, and

for the control, ultrasound, SDT, ultrasound’, and SDT’ group, respectively. The mean tumor volume on Day 5 for mice in SDT and SDT’ groups was substantially shrunk compared to the control group, with no statistically significant difference observed between the two SDT groups (Figure S6-b). As shown in Fig. 6-c, the tumor growth inhibition ratio in SDT and SDT’ group was 72.53% (p

for the control, ultrasound, SDT, ultrasound’, and SDT’ group, respectively. The mean tumor volume on Day 5 for mice in SDT and SDT’ groups was substantially shrunk compared to the control group, with no statistically significant difference observed between the two SDT groups (Figure S6-b). As shown in Fig. 6-c, the tumor growth inhibition ratio in SDT and SDT’ group was 72.53% (p 0.001 vs. control) and 76.27% (p

0.001 vs. control) and 76.27% (p 0.001 vs. control), respectively. Both SDT methods yielded a similar percentage reduction in tumor volume, with no statistically significant difference. However, considering the number of sessions and the ultrasound dose emitted in the SDT group, the most efficient method for treating stage 2 melanoma tumors was irradiation in contact (i.e., just using coupling gel) applied in the SDT’ group. There was no remarkable difference in body weight between experimental groups (Figure S3-c).

0.001 vs. control), respectively. Both SDT methods yielded a similar percentage reduction in tumor volume, with no statistically significant difference. However, considering the number of sessions and the ultrasound dose emitted in the SDT group, the most efficient method for treating stage 2 melanoma tumors was irradiation in contact (i.e., just using coupling gel) applied in the SDT’ group. There was no remarkable difference in body weight between experimental groups (Figure S3-c).

In the ultrasound’ group (Fig. 7-d,d.1,d.2), a necrotic region was observed in the epithelial tissue and central tumor area along the propagation direction of the ultrasound. The tissue appeared friable, and inflammatory infiltrates were detected adjacent to the necrotic regions. The presence of red blood cells indicated evidence of blood vessel extravasation. In the SDT’ group (Fig. 7-e,e.1,e.2), the epithelial tissue was notably affected, exhibiting focal areas of ulceration. Similar to the SDT group, the necrotic region extended across the entire cross-sectional area, with inflammatory infiltrates adjacent to these zones and widespread blood vessel extravasation throughout the necrotic areas. The temperature of the skin overlying the tumor, in contact with the transducer and a coupling gel layer, increased by up to  C during the final 5 minutes of ultrasound irradiation. Given that the tumor region was exposed to this temperature rise for a brief period, thermal effects in the ultrasound’ and SDT’ groups were considered negligible.

C during the final 5 minutes of ultrasound irradiation. Given that the tumor region was exposed to this temperature rise for a brief period, thermal effects in the ultrasound’ and SDT’ groups were considered negligible.

Discussion

Cutaneous melanoma is among the most aggressive and deadly types of skin cancer. Despite the high effectiveness of conventional treatments, melanoma exhibits a significantly higher mortality rate if not detected in its early stages87. Previous in vivo studies have demonstrated the potential of ALA-mediated SDT in treating pigmented melanoma, utilizing a subcutaneous implantation method for melanoma induction45,80,81. However, a subcutaneous tumor model is more compatible with a clinical subtype of human melanoma, known as primary dermal melanoma, which is a less common melanoma88. In this sense, intradermally implanted tumors were treated in the present research, as they more accurately represent the human cutaneous melanoma most frequently reported in clinical settings. Another distinguishing feature of the tumors treated in our study is their initial stage. While previous studies typically addressed melanomas with initial volumes of approximately 100  or greater, our study focused on smaller tumors, representative of early-stage human cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of

or greater, our study focused on smaller tumors, representative of early-stage human cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of  3 mm and volumes of

3 mm and volumes of  50

50  14,37,44,45,80–82.

14,37,44,45,80–82.

Previous to the in vivo experiments, acoustic measurements were carried out. The hydrophone-based measurements were performed in a homogeneous medium without tissue interfaces, which differs from the complex structure of biological tissues. However, mapping the acoustic field generated by the ultrasound device and characterizing its propagation profile remains valuable for predicting potential energy deposition patterns in vivo. Due to the physics of unfocused ultrasound propagation, the acoustic field includes distinct near-field and far-field regions, characterized by spatial oscillations in acoustic amplitude. By introducing the waveguide, we were able to concentrate the region of highest acoustic amplitude closer to the transducer, i.e., near the skin surface, which corresponds to the tumor location in our intradermal melanoma model.

While conducting the in vivo experiments, the characteristics of an intradermal tumor model were verified by ultrasonography. On the treatment day, the tumors were anatomically confined by the epidermis on the superficial side and by the panniculus carnosus, a thin dermal muscle layer, on the deep side, consistent with observations reported by Carlson et al.89 Tumor thickness was also verified with ultrasonography on the treatment day. While most preclinical studies report only the initial tumor volume on the treatment day, they often omit tumor thickness, a critical clinical parameter in melanoma staging18. In this study, a range of tumor’s Breslow depth (i.e., the vertical distance from the skin surface to the deepest layer of the tumor) that the tumor reached at the time treatment was initiated was defined. This approach aligns more closely with clinical practices and enhances the translational relevance of the results.

The present research comprised three studies aimed at addressing key unclear aspects of SDT on cutaneous melanoma. Study 1 investigated the influence of tumor thickness, classified as Stage 1 and Stage 2, on the therapeutic efficacy of SDT. This objective was motivated by previous findings suggesting that increased tumor depth may compromise the effectiveness of localized treatments by limiting energy penetration18,90,91. Thus, understanding the impact of tumor depth is essential for optimizing treatment protocols. To ensure accurate ultrasound delivery to the smaller Stage 1 tumors, a custom-designed conical aluminum waveguide was employed for ultrasound irradiation of both tumors (Stage 1 and Stage 2). This device reduced the effective radiating area (ERA) from 5  to 0.8

to 0.8  , as confirmed by the acoustic pressure profiles shown in Fig. 2-f, thereby enabling focused sonication of small target regions.

, as confirmed by the acoustic pressure profiles shown in Fig. 2-f, thereby enabling focused sonication of small target regions.

An extensive literature review on the application of SDT for melanoma treatment revealed that Wang et al. (2014), Hu et al. (2015), and Peng et al. (2018) investigated the therapeutic effects of ALA-mediated SDT using a murine model of subcutaneously implanted melanoma. In these studies, ALA was administered via intraperitoneal injection, and the initial tumor volume at the time of treatment was approximately 100  . Notably, the animal strain used, Balb/c athymic mice, was the same as that employed in the present study45,80,81. Wang et al.45 (2014) explored an SDT protocol of multiple sessions (twice a week for 2 weeks) using ALA (Dose: 250 mg/kg) and an unfocused ultrasound (diameter: 4 mm, ultrasound frequency: 1.1 MHz, Intensity: 2 W/

. Notably, the animal strain used, Balb/c athymic mice, was the same as that employed in the present study45,80,81. Wang et al.45 (2014) explored an SDT protocol of multiple sessions (twice a week for 2 weeks) using ALA (Dose: 250 mg/kg) and an unfocused ultrasound (diameter: 4 mm, ultrasound frequency: 1.1 MHz, Intensity: 2 W/ , pulse frequency: 100 Hz, duty cycle: 10%, irradiation time: 5 min, Dose: 60 J/

, pulse frequency: 100 Hz, duty cycle: 10%, irradiation time: 5 min, Dose: 60 J/ ) coupled to a degassed water-filled 20 cm-tube where tumors were submerged for ultrasound irradiation. Under these conditions, researchers related that ALA-mediated SDT inhibited tumor growth and reversed the local passive innate immune system; this is M2 tumor-associated macrophages changed to the M1 phenotype, and immature DCs developed into mature DCs under ALA-mediated SDT. Hu et al.)80 (2015) assessed a single SDT protocol of one session using ALA (D: 200 mg/kg) and an unfocused ultrasound (d: 3 mm, f: 1 MHz, I: 1 W/

) coupled to a degassed water-filled 20 cm-tube where tumors were submerged for ultrasound irradiation. Under these conditions, researchers related that ALA-mediated SDT inhibited tumor growth and reversed the local passive innate immune system; this is M2 tumor-associated macrophages changed to the M1 phenotype, and immature DCs developed into mature DCs under ALA-mediated SDT. Hu et al.)80 (2015) assessed a single SDT protocol of one session using ALA (D: 200 mg/kg) and an unfocused ultrasound (d: 3 mm, f: 1 MHz, I: 1 W/ , PF: 100 Hz, DC: 10%, t: 10 min, D: 60 J/

, PF: 100 Hz, DC: 10%, t: 10 min, D: 60 J/ ). Similar to our study, the ultrasound signal was applied through a tapered conical aluminum buffer head with its front surface directly in contact with the skin above the tumor site (5 mm-small end face). They explored the SDT anti-tumor effects and the role of miRNAs in this process. They found that the ALA-mediated SDT inhibited tumor growth, and its mechanism might be associated with the induction of miR-34a expression, which led to apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via p53-miR-34a-Sirt1 axis. Similar to Wang et al. (2014), Peng et al.81 (2018) evaluated a multiple sessions ALA-SDT protocol (twice a week for 2 weeks, ALA: 250 mg/kg) applying an unfocused ultrasound (d: 5 mm, f: 1 MHz, I: 0.8 W/

). Similar to our study, the ultrasound signal was applied through a tapered conical aluminum buffer head with its front surface directly in contact with the skin above the tumor site (5 mm-small end face). They explored the SDT anti-tumor effects and the role of miRNAs in this process. They found that the ALA-mediated SDT inhibited tumor growth, and its mechanism might be associated with the induction of miR-34a expression, which led to apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via p53-miR-34a-Sirt1 axis. Similar to Wang et al. (2014), Peng et al.81 (2018) evaluated a multiple sessions ALA-SDT protocol (twice a week for 2 weeks, ALA: 250 mg/kg) applying an unfocused ultrasound (d: 5 mm, f: 1 MHz, I: 0.8 W/ , PF: 100 Hz, DC: 10%, t: 5 min, D: 24 J/

, PF: 100 Hz, DC: 10%, t: 5 min, D: 24 J/ ). The ultrasound transducer was coupled to a conical aluminum part (5 mm-small end face). They focused on the SDT effects on tumor growth, immune cells, and blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment, finding that ALA-mediated SDT inhibited tumor growth, effectively activated CD8+ T cells, and inhibited the activity of T regulatory cells. Besides, the tumor peripheral vessels were dilated, and ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1), a membrane protein that enables leukocytes to adhere to vascular endothelium, was upregulated on HUVECs following SDT, which may facilitate the transendothelial migration of immune cells into inflamed tissues, enhancing the anti-tumor immune response. The studies mentioned above demonstrated the efficacy of SDT in melanoma treatment and its influence on the immune response within the tumor microenvironment in inmunocompromised mice (Balb/c athymic mice). The number of T cells in Balb/c athymic mice is reduced, but macrophages and dendritic cells are components of innate immunity, which is still present in this mouse model. Besides, the intradermal region is a highly vascularized environment with a dense population of dendritic cells, which improves oxygen delivery and enhances tumor immunogenicity. Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that applying SDT to intradermal tumors situated in a more immunologically active and oxygen-rich environment would further amplify the SDT antitumoral effects.

). The ultrasound transducer was coupled to a conical aluminum part (5 mm-small end face). They focused on the SDT effects on tumor growth, immune cells, and blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment, finding that ALA-mediated SDT inhibited tumor growth, effectively activated CD8+ T cells, and inhibited the activity of T regulatory cells. Besides, the tumor peripheral vessels were dilated, and ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1), a membrane protein that enables leukocytes to adhere to vascular endothelium, was upregulated on HUVECs following SDT, which may facilitate the transendothelial migration of immune cells into inflamed tissues, enhancing the anti-tumor immune response. The studies mentioned above demonstrated the efficacy of SDT in melanoma treatment and its influence on the immune response within the tumor microenvironment in inmunocompromised mice (Balb/c athymic mice). The number of T cells in Balb/c athymic mice is reduced, but macrophages and dendritic cells are components of innate immunity, which is still present in this mouse model. Besides, the intradermal region is a highly vascularized environment with a dense population of dendritic cells, which improves oxygen delivery and enhances tumor immunogenicity. Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that applying SDT to intradermal tumors situated in a more immunologically active and oxygen-rich environment would further amplify the SDT antitumoral effects.

Ultrasound parameters commonly reported in the literature to effectively induce sonodynamic effects typically include ultrasound frequencies ranging from 0.5 to 3 MHz, a pulse repetition frequency of 100 Hz, duty cycle of 30-50 %, and ultrasound intensities in the range of 0.5 to 3 W/ . The ultrasound parameters used in this study were selected based on both literature precedent and preliminary experimental evaluation. Pulsed ultrasound irradiation was chosen to minimize the risk of excessive thermal damage. The ultrasound frequency (1 MHz) and pulse repetition frequency (100 Hz) were selected based on literature37,45,80–82. The ultrasound intensity (2 W/

. The ultrasound parameters used in this study were selected based on both literature precedent and preliminary experimental evaluation. Pulsed ultrasound irradiation was chosen to minimize the risk of excessive thermal damage. The ultrasound frequency (1 MHz) and pulse repetition frequency (100 Hz) were selected based on literature37,45,80–82. The ultrasound intensity (2 W/ ), duty cycle (50%) and irradiation period (30 minutes) were defined based on a preliminary pilot study, in which various parameter combinations were tested. These selected parameters yielded the most effective antitumor response while remaining within the range of values commonly reported in the literature. However, the delivered total dose of 1800 J/

), duty cycle (50%) and irradiation period (30 minutes) were defined based on a preliminary pilot study, in which various parameter combinations were tested. These selected parameters yielded the most effective antitumor response while remaining within the range of values commonly reported in the literature. However, the delivered total dose of 1800 J/ per day was higher than in previous in vivo studies14,37,44,45,80–82. During temperature monitoring conducted throughout the ultrasound irradiation, it was observed that the temperature at the skin surface overlying the tumor, directly in contact with the small end face of the waveguide and the coupling gel, increased by approximately 3

per day was higher than in previous in vivo studies14,37,44,45,80–82. During temperature monitoring conducted throughout the ultrasound irradiation, it was observed that the temperature at the skin surface overlying the tumor, directly in contact with the small end face of the waveguide and the coupling gel, increased by approximately 3  C during the final 5 minutes of sonication. The temperature remained below levels associated with significant thermal damage, thereby ensuring that the observed therapeutic effects could be attributed primarily to sonodynamic mechanisms rather than thermal effects. The results of study 1 demonstrated suppression of tumor volume growth after SDT for both tumor stages. This indicates that, under the conditions utilized in this study, the induction of sonodynamic effects is achievable even in stage 2 tumors. Furthermore, incorporating a waveguide for applying SDT in treating thinner tumors proved to be an effective approach.

C during the final 5 minutes of sonication. The temperature remained below levels associated with significant thermal damage, thereby ensuring that the observed therapeutic effects could be attributed primarily to sonodynamic mechanisms rather than thermal effects. The results of study 1 demonstrated suppression of tumor volume growth after SDT for both tumor stages. This indicates that, under the conditions utilized in this study, the induction of sonodynamic effects is achievable even in stage 2 tumors. Furthermore, incorporating a waveguide for applying SDT in treating thinner tumors proved to be an effective approach.

Study 2 investigated the therapeutic potential of combining SDT with PDT for treating stage 1 cutaneous melanoma tumors. Due to the limited penetration of light in biological tissues, the combined protocol was exclusively applied to stage 1 tumors90,91. The PDT protocol used in this study (635 nm, 100 W/ , 120 J/

, 120 J/ ) was based on previously established PDT protocols in the literature, which employed ALA-mediated PDT in a murine melanoma model14–16,92.

) was based on previously established PDT protocols in the literature, which employed ALA-mediated PDT in a murine melanoma model14–16,92.

Juzenas et al. (2002) observed delayed tumor growth in a murine melanoma model following the topical application of M-ALA-PDT (633 nm, 120 J/ )92. Similarly, Abels et al. (1997), Haddad et al. (2000), and Lin et al. (2016) reported delayed melanoma growth, including prolonged survival of treated mice, when systemic ALA-PDT (630 nm, 50–100 J/

)92. Similarly, Abels et al. (1997), Haddad et al. (2000), and Lin et al. (2016) reported delayed melanoma growth, including prolonged survival of treated mice, when systemic ALA-PDT (630 nm, 50–100 J/ ) was applied. The partial outcomes reported in these studies may be attributed to the challenge of poor light penetration in pigmented tissues. One interesting approach to addressing this limitation is the use of optical clearing agents. For instance, Radi et al. (2018) and Pires et al. (2020) reported PDT protocols combined with OCAs employing ferrous chlorophyllin transethosome gel and a combination of sensitizers (Photodithazine and Visudyne), respectively. These strategies successfully achieved complete tumor regression in cutaneous melanoma models18,19. However, using certain OCAs may alter some tissue biological properties (e.g., dehydration, changes in collagen structure), potentially affecting the absorption and distribution of the sensitizer. In some cases, OCAs may induce uneven tissue clearing, leading to irregular treatment areas. Additionally, unpredictable interactions between OCAs and the sensitizer or cellular components could disrupt the photochemical reactions required for effective ROS generation93.

) was applied. The partial outcomes reported in these studies may be attributed to the challenge of poor light penetration in pigmented tissues. One interesting approach to addressing this limitation is the use of optical clearing agents. For instance, Radi et al. (2018) and Pires et al. (2020) reported PDT protocols combined with OCAs employing ferrous chlorophyllin transethosome gel and a combination of sensitizers (Photodithazine and Visudyne), respectively. These strategies successfully achieved complete tumor regression in cutaneous melanoma models18,19. However, using certain OCAs may alter some tissue biological properties (e.g., dehydration, changes in collagen structure), potentially affecting the absorption and distribution of the sensitizer. In some cases, OCAs may induce uneven tissue clearing, leading to irregular treatment areas. Additionally, unpredictable interactions between OCAs and the sensitizer or cellular components could disrupt the photochemical reactions required for effective ROS generation93.

Another approach aiming to overcome the challenges posed by PDT in pigmented lesions is its combination with SDT, since ultrasound exhibits excellent tissue penetration independent of melanin. Several preclinical studies have reported the enhanced antitumor effects of SPDT using free organic sensitizers in various tumor models27,46. These effects include increased mitochondrial membrane damage, reduced cell proliferation and tumor growth, elevated ROS generation, and enlarged areas of apoptosis and necrosis when compared to monotherapies94. Haiping Wang et al. (2013) and Pan Wang et al. (2015) conducted similar studies measuring intracellular ROS production in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with PDT (1.2 J/ ), SDT (1.0 MHz, 0.36 W/

), SDT (1.0 MHz, 0.36 W/ , 60 s), and their combinations (SPDT and PSDT) using Chlorine 6. Both studies showed that combined treatments led to significantly higher ROS levels compared to monotherapies, as evidenced by increased fluorescence intensity and a greater proportion of ROS-positive cells. In both cases, the use of NAC, a ROS scavenger, restored cell viability and reversed treatment-induced effects, such as morphological changes. These findings highlight that enhanced ROS generation plays a central role in the synergistic cytotoxicity observed with the combined SDT and PDT treatments95,96. Liu et al. (2016) measured intracellular ROS production in 4T1 cells two hours after treatment with PDT (1.4 J/

, 60 s), and their combinations (SPDT and PSDT) using Chlorine 6. Both studies showed that combined treatments led to significantly higher ROS levels compared to monotherapies, as evidenced by increased fluorescence intensity and a greater proportion of ROS-positive cells. In both cases, the use of NAC, a ROS scavenger, restored cell viability and reversed treatment-induced effects, such as morphological changes. These findings highlight that enhanced ROS generation plays a central role in the synergistic cytotoxicity observed with the combined SDT and PDT treatments95,96. Liu et al. (2016) measured intracellular ROS production in 4T1 cells two hours after treatment with PDT (1.4 J/ ), SDT (0.84 MHz, 0.25 W/

), SDT (0.84 MHz, 0.25 W/ , 60 s), SPDT, and PSDT using sinoporphyrin sodium. The results showed that combined treatment groups produced 4–5 times higher intracellular ROS levels compared to the SDT and PDT monotherapy groups97. Additionally, studies involving microorganisms have reported synergistic effects of SPDT64. Regarding melanoma, only one previous in vitro study has been identified, which showed enhanced cytotoxicity in human melanoma cells when PDT and SDT were combined63. However, to date, in vivo studies about the application of SPDT as a treatment for melanoma have not been reported. These findings lead us to investigate the in vivo cytotoxic effects of SPDT on murine cutaneous melanoma.

, 60 s), SPDT, and PSDT using sinoporphyrin sodium. The results showed that combined treatment groups produced 4–5 times higher intracellular ROS levels compared to the SDT and PDT monotherapy groups97. Additionally, studies involving microorganisms have reported synergistic effects of SPDT64. Regarding melanoma, only one previous in vitro study has been identified, which showed enhanced cytotoxicity in human melanoma cells when PDT and SDT were combined63. However, to date, in vivo studies about the application of SPDT as a treatment for melanoma have not been reported. These findings lead us to investigate the in vivo cytotoxic effects of SPDT on murine cutaneous melanoma.

The results of this study demonstrated that both ALA-PDT and ALA-SDT can induce a significant tumor growth inhibition as monotherapy. However, when applied SDT+PDT under the specific experimental conditions used in this study, the CI analysis indicated no clear synergistic advantage of the combined treatment. Instead, the outcomes were comparable to those achieved with PDT or SDT alone. The absence of a synergistic effect may be explained by several factors. In this study, SDT was applied first (30 min), followed by PDT (20 min). Prolonged ultrasound exposure during SDT may have consumed available oxygen within the tumor microenvironment (oxygen depletion), which could not be replenished given the immediate sequential application of PDT, potentially impairing ROS generation during the PDT phase. In addition, the limited light penetration used in PDT resulted in a predominantly superficial effect, overlapping with regions already treated by SDT, thus limiting spatial complementarity. The use of effective monotherapy doses and a sequential single-session protocol may have further constrained the opportunity for synergistic interaction. Moreover, heterogeneity in PpIX distribution and oxygen availability within the tumor may have also contributed to the observed results. It should be noted that the CI alone may not fully capture all potential interactions between the modalities, and further mechanistic investigations and complementary analyses would be necessary to comprehensively validate synergy in this context. This represents an important direction for future studies.

Study 3 of the present study evaluated the efficacy of two ultrasound delivery methods: using a waveguide and direct contact. As previously mentioned in the introduction, various methods for ultrasound delivery have been reported in the literature, including the use of couplers (e.g., gel, animal tissue, cylindrical tubes, water-filled tanks, or gloves) or waveguides (commonly conical and filled with water or metal-made). However, the rationale for choosing one method over another, the materials used, or the geometry of these devices is not well explained. Furthermore, there is a lack of characterization of these couplers or waveguides, which would provide a clearer understanding of how the irradiation field differs when using these tools. Hu et al. (2015) and Pen et al. (2018) evaluated the antitumor effects of ALA-SDT in a large murine melanoma model (100  ) using a conical aluminum waveguide. This waveguide featured a small end face with a 5 mm diameter, which was positioned in contact with the tumor during irradiation80,81. Wang et al. (2014) used a tube filled with degassed water. Although all these studies reported the therapeutic effects of SDT, they did not provide a rationale for the selection of the specific ultrasound irradiation method employed45.

) using a conical aluminum waveguide. This waveguide featured a small end face with a 5 mm diameter, which was positioned in contact with the tumor during irradiation80,81. Wang et al. (2014) used a tube filled with degassed water. Although all these studies reported the therapeutic effects of SDT, they did not provide a rationale for the selection of the specific ultrasound irradiation method employed45.

One SDT protocol of this study involved the use of a waveguide between the US transducer and the tumor (total transducer dose of 1800 J/ per day, treatment time: 30 min), and the other SDT protocol employed only a coupling gel layer between the US transducer and the tumor (total transducer dose of 180 J/

per day, treatment time: 30 min), and the other SDT protocol employed only a coupling gel layer between the US transducer and the tumor (total transducer dose of 180 J/ , treatment time: 5 min). Acoustic measurements revealed variations in the pressure profile along the z-axis when the waveguide was coupled to the transducer. This change was important for focusing ultrasonic energy on the animal’s skin, as our goal was to treat cutaneous tumors. The data also showed that the acoustic pressure near the small face of the waveguide was reduced by approximately 25% compared to direct transducer contact. This acoustic energy dissipation occurs after propagation through the waveguide, as shown in Fig. 2-b,e. It is likely attributable to the waveguide’s material properties or geometry, resulting in significantly lower energy delivery at the tumor site relative to the total transducer dose. Consequently, it was necessary to increase the total energy delivered by extending the ultrasound exposure time (i.e., 5 to 30 minutes) to achieve therapeutic outcomes comparable to those observed with direct application methods. Despite this, the waveguide was made of aluminum rather than other materials for its ease of use.

, treatment time: 5 min). Acoustic measurements revealed variations in the pressure profile along the z-axis when the waveguide was coupled to the transducer. This change was important for focusing ultrasonic energy on the animal’s skin, as our goal was to treat cutaneous tumors. The data also showed that the acoustic pressure near the small face of the waveguide was reduced by approximately 25% compared to direct transducer contact. This acoustic energy dissipation occurs after propagation through the waveguide, as shown in Fig. 2-b,e. It is likely attributable to the waveguide’s material properties or geometry, resulting in significantly lower energy delivery at the tumor site relative to the total transducer dose. Consequently, it was necessary to increase the total energy delivered by extending the ultrasound exposure time (i.e., 5 to 30 minutes) to achieve therapeutic outcomes comparable to those observed with direct application methods. Despite this, the waveguide was made of aluminum rather than other materials for its ease of use.

It is important to highlight that tumor monitoring through ultrasonography demonstrated considerable effectiveness, particularly for tumors treated with light, since the swelling induced post-treatment impeded accurate tumor measurements using more conventional tools, such as calipers. Besides, volume estimation could be less reliable, calculating it assuming its ellipsoidal shape, even after treatment, when tumors usually have an irregular shape.

Conclusions

Under the specific light and ultrasound conditions applied, SDT was observed to induce necrosis at greater depths compared to PDT, as well as to significantly inhibit tumor growth in early-stage cutaneous melanoma.

Although several studies have reported synergistic effects between PDT and SDT, under the specific experimental conditions used in this study, the evaluation of SDT combined with PDT revealed no significant enhancement in therapeutic efficacy. This outcome could be attributed to oxygen depletion induced by the prior SDT application, which likely reduced oxygen availability during the subsequent PDT phase. Consequently, further optimization of treatment sequence, timing, and dosing may be necessary to better explore the potential for synergistic effects. In addition, future studies assessing the effects on the surrounding healthy tissue and the potential stimulation of metastasis would be highly valuable.

In summary, ALA-mediated SDT shows promise for the treatment of cutaneous melanoma, and this study contributes an additional step toward its clinical implementation. Despite the potential ultrasound energy losses associated with using a conical aluminum waveguide, our findings suggest that it remains a valuable tool for treating small tumors, as it effectively concentrates ultrasound energy on localized small regions that would otherwise be challenging to target with direct irradiation.

Methods

Irradiation platform

The small area probe of the commercial photodynamic therapy device LINCE (MMOptics Ltda., São Paulo, Brazil) was used for light irradiation. The probe comprised five LED arrays emitting at 630±10 nm.98. The large-area probe (ERA: 5  ) of the commercial device Sonidel SP100 (Sonidel Limited, Dublin, Ireland) was used for ultrasound irradiation. In some cases described below, the large-area probe was coupled to a conical aluminum waveguide for ultrasound irradiation.

) of the commercial device Sonidel SP100 (Sonidel Limited, Dublin, Ireland) was used for ultrasound irradiation. In some cases described below, the large-area probe was coupled to a conical aluminum waveguide for ultrasound irradiation.

Acoustic measurements

The AIMS III Hydrophone Scanning Tank (OndaCorp, USA) was used to characterize the propagation of ultrasound waves generated by the above-mentioned ultrasound device. The AIMS III system features an acrylic tank with internal dimensions of 0.89 x 0.51 x 0.58 m (width, height, and depth). It includes an automated three-axis support for positioning the hydrophone, a rotating support for the transducer being studied, and the AQUAS-10 Water Conditioner (OndaCorp, USA) that degasses water. This conditioner also has a microparticle filter and a UV lamp to eliminate impurities and maintain microbiological control of the water. The tank was filled with distilled water to a level adequate for data collection, and the water was kept in continuous circulation using the AQUA-10 throughout all measurements to ensure it remained degassed. An HNR-Series 1000 hydrophone (OndaCorp, USA) was employed, with an operating frequency range of 0.25 to 10 MHz and a maximum operating temperature of 50°C. The data were collected using the Soniq software (OndaCorp, United States), which works with the PicoScope 5000C Series oscilloscope software (Pico Technology, United States). The oscilloscope provides the root mean square (rms) voltage ( ), which is then converted into acoustic pressure (

), which is then converted into acoustic pressure ( ) by Eq. (1) and the conversion factor, M =

) by Eq. (1) and the conversion factor, M =  V/Pa, provided by the manufacturer.

V/Pa, provided by the manufacturer.

|

1 |

The propagation of ultrasound waves emitted by the large-area ultrasound probe was characterized by mapping the  values along the Z and X-axes. The irradiation emitted by the large-area transducer coupled to the waveguide was also characterized. Subsequently, the acoustic pressure profile for each configuration was plotted using MATLAB (Matlab 2022b, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The ultrasound parameters were set: resonance frequency at 1 MHz, continuous irradiation mode, and ultrasound intensity of 1 W/

values along the Z and X-axes. The irradiation emitted by the large-area transducer coupled to the waveguide was also characterized. Subsequently, the acoustic pressure profile for each configuration was plotted using MATLAB (Matlab 2022b, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The ultrasound parameters were set: resonance frequency at 1 MHz, continuous irradiation mode, and ultrasound intensity of 1 W/ .

.

Tumor model

Female athymic Nu/J nude mice (weight: 20–25 g, age: 6-8 weeks) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Texas A&M University (IACUC 2023-0137). The mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment at a 12 h light/dark illumination schedule and had free access to food and water. After the acclimation period (1 week), 50  L of B16-F10 cell solution (sterile PBS, 1x10

L of B16-F10 cell solution (sterile PBS, 1x10 cells per animal) was intradermally implanted on the right flank of the mice using a 30ga needle under inhaled anesthesia (isoflurane 5% for induction and 2% for maintenance). The intradermal implantation was verified through physical examination, as described by Carlson et al.89, immediately after cell inoculation. This examination involved lateral skin displacement, with correct implantation indicated by the corresponding shift of cell solution. After a few days, the tumors were visibly attached to the skin and moved freely along with it, consistent with observations reported by Carlson et al.89.

cells per animal) was intradermally implanted on the right flank of the mice using a 30ga needle under inhaled anesthesia (isoflurane 5% for induction and 2% for maintenance). The intradermal implantation was verified through physical examination, as described by Carlson et al.89, immediately after cell inoculation. This examination involved lateral skin displacement, with correct implantation indicated by the corresponding shift of cell solution. After a few days, the tumors were visibly attached to the skin and moved freely along with it, consistent with observations reported by Carlson et al.89.

ALA administration

EMI Pharma (São Carlos, SP, Brazil) supplied 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) as a powder. It was diluted in water injection at a 100 mg/mL concentration, and its pH was adjusted to 5.0–6.5 by adding 1 N sodium hydroxide. The solution was freshly prepared and used within one hour after preparation. On treatment days (Days 1 and 2), ALA solution was administered via intraperitoneal injection at a concentration of 200 mg/kg body weight80,82. PpIX accumulation in melanoma tumors was previously assessed at 3, 4, and 5 hours following intraperitoneal administration of ALA through chemical extraction of PpIX from excised tumor tissues99. The results demonstrated that in that condition, the peak PpIX accumulation occurred around three hours post-ALA administration. Accordingly, an incubation period of three hours was selected for the present study. During this time, animals were maintained in a dark environment to prevent unintended photoactivation of the sensitizer.

Therapeutic experimental groups

As shown in Fig. 3, this research comprises three main studies utilizing mice with tumors of two distinct Breslow depths. Tumors with a Breslow depth of 1–1.5 mm represented Stage 1 cutaneous melanoma, while those with a Breslow depth of 2.5–3 mm represented Stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. Therefore, the tumors in this study will be referred to as stage 1 and stage 2 tumors. In the three studies, the mice were under general anesthesia (5% isoflurane for induction, 2% for maintenance) during all the procedures. The PpIX accumulation in the tumor region before and after treatment was verified by recording widefield fluorescence images with a camera connected to a fluorescence probe ( nm) of LINCE (Figure S7)98. The temperature increment on the tumor region was monitored using a FLUK-Ti400 60 Hz infrared camera (Fluke®, EUA). The body weight was monitored daily. Mice were euthanized 4 days after the first treatment session by anesthetic overdose, using a maximum dose of Isoflurane (4% in oxygen). As a confirming death method, the application of cervical dislocation is foreseen after detecting the absence of vital signs. Immediately after, the tumors were taken using a scalpel.

nm) of LINCE (Figure S7)98. The temperature increment on the tumor region was monitored using a FLUK-Ti400 60 Hz infrared camera (Fluke®, EUA). The body weight was monitored daily. Mice were euthanized 4 days after the first treatment session by anesthetic overdose, using a maximum dose of Isoflurane (4% in oxygen). As a confirming death method, the application of cervical dislocation is foreseen after detecting the absence of vital signs. Immediately after, the tumors were taken using a scalpel.

Study 1: comparison of SDT outcome on stage 1 and stage 2 tumors using a waveguide

This study analyzed and compared the effectiveness of SDT using a conical aluminum waveguide on stage 1 and stage 2 tumors (Fig. 3-a). When the tumors reached the depth corresponding to Stage 1 tumor, mice were randomly divided into three groups: control (n=4), ultrasound (n=4), and SDT (n=5) group. Similarly, the mice were categorized into three groups when the tumors reached the depth corresponding to Stage 2. The mice in the control group did not receive any treatment. In the ultrasound group, the mice were exposed solely to ultrasound irradiation, while in the SDT group, the mice received ALA administration, followed by ultrasound irradiation.