Abstract

Fluorescence microscopy enables the visualization of cellular morphology, molecular distribution, ion distribution, and their dynamic behaviors during biological processes. Enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in fluorescence imaging improves the quantification accuracy and spatial resolution; however, achieving high SNR at fast image acquisition rates, which is often required to observe cellular dynamics, still remains a challenge. In this study, we developed a technique to rapidly freeze biological cells in milliseconds during optical microscopy observation. Compared to chemical fixation, rapid freezing provides rapid immobilization of samples while more effectively preserving the morphology and conditions of cells. This technique combines the advantages of both live-cell and cryofixation microscopy, i.e., temporal dynamics and high SNR snapshots of selected moments, and is demonstrated by fluorescence and Raman microscopy with high spatial resolution and quantification under low temperature conditions. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that intracellular calcium dynamics can be frozen rapidly and visualized using fluorescent ion indicators, suggesting that ion distribution and conformation of the probe molecules can be fixed both spatially and temporally. These results confirmed that our technique can time-deterministically suspend and visualize cellular dynamics while preserving molecular and ionic states, indicating the potential to provide detailed insights into sample dynamics with improved spatial resolution and temporal accuracy in observations.

Subject terms: Wide-field fluorescence microscopy, Ca2+ imaging, Super-resolution microscopy, Biophotonics, Imaging and sensing

Our cryo-optical microscopy rapidly freezes cells at an arbitrary timepoint during live imaging, enabling detailed observation of specific moments during dynamic events under cryogenic conditions.

Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy techniques are widely employed to study the cellular dynamics of biological events, as they enable visualizing molecular distributions, ion signaling, and molecular or protein interactions alongside cellular morphologies. Furthermore, the use of functional fluorescent probes1–3 and/or the incorporation of external stimulation techniques, such as electrical stimulation4, chemical condition changes5, and mechanical stimulation6, have further expanded the range of biological investigations possible with fluorescence microscopy.

Studying dynamic biological processes, where the distribution and state of molecules and ions changes over time, often requires fast image acquisition to accurately capture their co-localizations, behaviors, and interactions. While improving signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) offers distinct benefits, such as improved quantification accuracy and spatial resolution, achieving high SNR under short image acquisition times remains challenging. Additionally, the need for fast image acquisition also limits the applicability of various fluorescence imaging approaches, such as super-resolution imaging7–12, three-dimensional (3D) imaging, and fluorescence lifetime imaging, that would provide further detailed information but typically require relatively long image acquisition times, such as several hundred milliseconds to minutes.

In this study, we developed a technique utilizing a simple, easy-to-handle device to in situ rapidly freeze living cellular samples and their subcellular dynamics in millisecond order during observation using optical microscopy observations with high spatial and temporal resolutions. This technique visualizes the path of biological dynamics by tracing temporal information before fixation, allowing the rapid arrest of cellular morphologies, ion distributions, and chemical states at an arbitrary time during a biological event, while also enabling the acquisition of high SNR snapshots of them with extended exposure times under cryogenic conditions. Additionally, we also developed a method to control the timing of cryofixation with a precision of ± 10 ms. By combining this precise cryofixation timing control with an optical stimulation technique, we accurately determined the time interval between the initiation of biological events and cryofixation during optical microscopy observation. While rapid freezing-based techniques, such as pouring liquid cryogen over in vivo tissue or organ samples and subsequently performing freeze substitution, have previously been proposed and utilized for sample observation and analysis using optical/electron microscopy observations13,14, our technique specifically adapts rapid freezing for near-instantaneous immobilization of cellular samples and dynamics under optical microscopy observations, enabling subsequent cryogenic observations using various optical microscopy modalities.

Cryofixation has long been utilized to immobilize samples in the conditions close to their native states15, and has been frequently employed in the field of life science studies involving electron microscopy16,17. While the degree of immobilization required for optical microscopy is less stringent than for electron microscopy due to its lower spatial resolution, cryofixation still offers the distinct advantage over chemical fixation in preserving cellular structures15,18,19. This preservation is essential for analysis of cellular details using super-resolution fluorescence imaging techniques20–27. Moreover, cryofixation may preserve the chemical state and environment in samples, such as the redox state of molecules, pH, and ion concentration, which cannot be realized by traditional chemical fixation techniques, such as using paraformaldehyde28–30. The benefits of cryofixation in optical microscopy observations, including enhanced photostability of sample molecules and improved quantum yield, have also been recognized31–36. However, the optical properties of some fluorescent probes, such as photoswitching behaviors or the fluorescence intensity ratio within the fluorescence spectrum, may differ under cryogenic conditions compared to room temperature conditions or may show temperature dependencies21,31,37. Understanding these differences is crucial prior to performing cryogenic observations of samples using fluorescent probes31,38,39.

Recently, rapid freezing techniques of a sample on a microscope stage have been proposed and demonstrated, enabling cryofixation at specific time points during optical microscopy observations40–43. These techniques have successfully demonstrated the cryofixation of the movement of Caenorhabditis elegans during fluorescence imaging41, achieving cryofixation within 30 ms, as well as the cryofixation of mammalian cells during fluorescence imaging at time intervals from a few seconds to several minutes43. Subsequent cryogenic optical observations, including super-resolution or fluorescence lifetime imaging40,43, further demonstrated their potential. Advancing such rapid freezing techniques to enable the rapid immobilization of biological dynamics, especially at subcellular level, during optical microscopy observations with high spatial and temporal resolution, as studied in this research, significantly benefit a wide range of biological studies. High SNR and spatial-resolution snapshots of biological events at accurate moments, along with the recording of biological dynamic behaviors leading up to the immediate moment of cryofixation, are expected to provide deeper and more accurate insights into cellular functions, molecular distributions, molecular co-localization, and other aspects related to the dynamic biological events.

Results

On-stage chamber for rapid freezing

We developed a sample-freezing chamber that can be placed on an inverted optical microscope, as shown in Fig. 1a (Materials and Methods). A liquid cryogen composed of propane and isopentane was introduced into the sample in the chamber so that the living cells were frozen by heat exchange between the cryogen and sample (Materials and Methods). The volume of buffer solution surrounding the cells was reduced specifically to facilitate rapid freezing, with no noticeable impact on biological events observed. With this method, the residual buffer height was estimated to be 6.7 ± 2.5 µm (Fig. S1). The cryogen was maintained on the sample to ensure that the sample remained at cryogenic temperature during optical observations. Our on-stage freezing chamber features an open-top design, enabling cell stimulation by altering buffer solution conditions prior to freezing. We confirmed that the drift velocity is only 31 nm s−1 after 30 s following rapid freezing, which is sufficiently low to avoid motion artifacts in fluorescence imaging using this on-stage freezing chamber (Fig. S2). We also confirmed that our on-stage freezing chamber maintained the sample temperature below the glass transition temperature of pure water (−136 °C)44 for about 3.3 min (Fig. S3), which is long enough for many applications using fluorescence imaging. To assess the extent of ice crystal formation with our freezing method, we performed cryo-transmission electronic microscopy (cryo-TEM) observation of HeLa cells, which were frozen by dropping the cryogen onto the sample. The cryo-TEM results confirmed that almost no ice crystal formation was observed within HeLa cells (Fig. S4). Given the spatial resolution of optical microscopy is on the order of several hundreds nm, such small ice crystal formation is unlikely to impact image quality or biological interpretation by optical microscopy. Supporting this, structured illumination microscopy (SIM)12 revealed no noticeable damage or notable morphological alternation in cells subjected to rapid freezing with our on-stage freezing chamber (Fig. S5).

Fig. 1.

On-stage freezing chamber, Cryofixation of cellular dynamics under microscopic observation, and cryogenic super-resolution imaging. a Cross-sectional schematics and photograph of on-stage freezing chamber. b Cryofixation of Ca2+ wave propagating in the neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (frame rate: 100 frames s-1, Video S1). Ca2+ wave motion stopped at the frame of 0 ms by cryofixation. The white arrow in the image indicated the region where Ca2+ wave motion stopped. Post-cryofixation, the image contrast was predominantly preserved, with only slight discernible differences. Although further investigations are needed to elucidate the details of the slight difference in the image contrast before and after cryofixation, this may be attributed to variations in optical property of Fluo-4 in the cytoplasm and cellular organelles, contamination of cellular autofluorescence, which is also enhanced under cryogenic conditions, and the difference of physiochemical properties between Fluo-4 and cellular molecules under cryogenic conditions. If contamination of cellular autofluorescence is the case, employing spectral unmixing techniques or a calcium indicator with longer excitation and emission wavelengths would mitigate this issue significantly. Note that, as described in the Materials and Methods, the fluorescence intensity of each image was normalized for visualization purpose based on the fluorescence intensity of the selected area in the observed cells. c Fluorescence intensity profiles of the line indicated with the red and blue arrows in (b). These profiles show that the leading edge of the Ca2+ wave moves from left to right in this plot and is then arrested by cryofixation. These intensity line profiles were normalized to allow for comparison of the time variation in graph shapes at each line location. d Ca2+ titration curve of Fluo-4 under 20 °C and −180 °C (rapid freezing). This data was measured using Fluo-4 in a Ca2+ calibration buffer (“Materials and Methods”). After freezing the dissociation of calcium indicator is unlikely to occur in freezing conditions, as it does in liquid environments, we referred to the values calculated from the fitting function of the post-freezing data as Kcryofix, instead of Kd to avoid confusion. It was confirmed that a Kd value similar to that in ref. 45 was obtained at the room temperature, and the shape of the Ca2+ titration curve was preserved after cryofixation. This result supports the preservation of the image contrast of the Fluo-4 loaded neonatal rat cardiomyocytes after cryofixation, as demonstrated in (b). e Cryogenic dual-color super-resolution and conventional widefield fluorescence images of Ca2+ distribution and actin filaments in the neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. f Cryogenic 3D super-resolution fluorescence image of Ca2+ distribution in the neonatal rat cardiomyocyte (Video S2). 3D visualization was produced by using alpha rendering (Nikon, NIS-Elements). g Cryogenic conventional widefield fluorescence images of a HeLa cell expressing DsRed in mitochondria (frame rate: 1 frames s−1, Video S3). The mitochondria moved at 37 °C and were immobilized by cryofixation. Although the cell shape was slightly deformed by cryofixation, it was not significant as shown in the enlarged views in this figure

Cryofixation of cellular dynamics

Cryofixation was performed using a freezing chamber on a microscope stage to observe calcium activity, which is one of the most rapid cellular reactions. Figure 1b, c show a series of fluorescence images of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes loaded with a calcium-ion (Ca2+) indicator, Fluo-4, and fluorescence intensity profiles indicating the wavefront of the Ca2+ wave propagating in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (Materials and Methods, Fig. S6 for another demonstration of cryofixation halting Ca2+ wave propagation rapidly). During the observation of the Ca2+ wave, the cryogen was introduced, and the wave motion was stopped (Video S1). This result shows that rapid freezing can preserve not only the cell morphology and Ca2+ distribution, but also the chemical state of the fluorescent indicator because the contrast of the image remains largely unaltered before and after fixation.

We confirmed the ability to perform Ca2+ observations at cryogenic temperatures, by measuring the fluorescence intensity over a range of Ca2+ concentrations, and found a sigmoidal response, similar in shape to that of room temperature, as shown in Fig. 1d. To compare the characteristics with those at room temperature, we then introduce an effective binding constant Kcryofix, which refers to the inflection point in the response curve. On comparison with Kd, we found that Kcryofix was almost unaltered by rapid freezing (294 vs 306 nM, Fig. 1d, Materials and Methods). Interestingly, the dissociation constant Kd of Fluo-4 has been reported to be temperature-dependent45. This indicates that if the freezing process is fast enough, molecular responses and spatio-temporal conditions are halted without passing through a thermal equilibrium state, implying the pre-freezing state is preserved upon rapid freezing. In this study, we also confirmed that the fluorescence intensity of Ca2+ indicator, Fluo-4, increased under cryogenic conditions; however, the magnitude of increase was different between the cell nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. S7). Therefore, it is important to evaluate these regions independently when analyzing the spatial intensity distributions to avoid misinterpretation (Fig. S8, more detailed discussion in the Discussion section). During this experiment, the same optical system was used at room and cryogenic temperatures because the excitation and fluorescence spectra of Fluo-4 were not significantly different under these temperature conditions (Fig. S9).

The immobilization of the sample on the microscope stage can be fully exploited by various imaging techniques. Figure 1e shows a super-resolution fluorescence image obtained by three-dimensional (3D) structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM)12 of Fluo-4 and SPY-555, an actin probe for live cells, in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, demonstrating the super-resolution imaging of ions and associated cell behaviors that cannot be performed using conventional chemical fixation techniques (Fig. S10, “Materials and Methods”). Our result shows that the sarcomere lengths were slightly shorter in the high Ca2+ concentration region compared to the low Ca2+ concentration region46 (Fig. S11). It is important to note that the dark spots seen in the Ca2+ images under cryogenic conditions were already present before freezing (Fig. S12), confirming that they were not caused by the cryofixation process. These characteristic fluorescence intensity distributions were considered due to the accumulation or deposition of Ca2+ indicator within the cells47. Additionally, we confirmed that the spatial resolution of SIM is essentially maintained after cryofixation under our experimental conditions (Fig. S13).

We further performed 3D super-resolution imaging of the Ca2+ distribution in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes using 3D-SIM (Fig. 1f, Video S2, “Materials and Methods”), after Ca2+ wave propagation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes was halted by cryofixation during observation with a conventional widefield fluorescence microscope (Video S2, Materials and Methods). This result demonstrates the capability of our technique to capture detailed 3D spatial information about rapid dynamic cellular processes at a precise moment, which has been significantly difficult to visualize under living conditions.

In addition to Ca2+ dynamics, we also confirmed that the cryofixation technique effectively immobilized the motions of various subcellular structures, such as the mitochondria (Fig. 1g, Video S3, Materials and Methods) and lysosomes (Video S3, Materials and Methods). To evaluate the extent of morphological changes by cryofixation, we calculated the measurement errors in 2-point lengths of fluorescence images before and after cryofixation, using a B-spline based non-rigid registration algorithm48 (Fig. S14). The measurement errors in length for mitochondria (Fig. 1g, Video S3) and lysosomes samples (Video S3) are similar to that in expansion microscopy reported in ref. 48. We also confirmed that, even at 15 min after freezing, no noticeable morphological changes caused by ice crystal formation were observed at the spatial resolution of widefield fluorescence microscopy used in this study, although ice crystals may form as the temperature increases (Fig. S15). This suggested that, at this level of spatial resolution, observations with longer exposure times are feasible and can be used to obtain fluorescence images with improved SNR.

Time-deterministic cryofixation

As shown above, the rapid cryofixation on the microscope stage allows us to precisely determine the time of fixation during observation, which provides temporal information on biological events just before and at the moment of cryofixation. Time-deterministic features are especially useful when combined with a technique that triggers biological events. We used a caged Ca2+ compound that can modulate the Ca2+ concentration in cells by light irradiation to trigger Ca2+ waves in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes before cryofixation49 (“Materials and Methods”). For the determination of the time between signal triggering and cryofixation, we developed a cryogen injector (Fig. 2a, Fig. S16, “Materials and Methods”), equipped with an externally triggerable electric valve, and enabled the injection of liquid cryogen onto a sample with a timing precision of ±10 ms (Fig. 2a). By using the optical setup in Fig. 2a, Ca2+ propagation in the cell was frozen at 120 ms after applying the trigger signal to the UV laser light source (Fig. 2b and Video S4). By referring to the video recorded immediately before, it is possible to determine the timing of the cell dynamics under observation, which are being observed in detail with the cryo-microscope. This technique can be combined with various external stimuli, such as electrical stimulation, chemical condition changes, and mechanical stimulation4–6.

Fig. 2.

Time-deterministic cryofixation of Ca2+ dynamics. a Optical microscope setup equipped with a UV laser source for signal triggering and a precise cryogen injection control system (Materials and Methods). The timing of UV laser irradiation and cryogen injection was controlled by electrical trigger signals, which can be sent individually and synchronously or asynchronously to each device. The delay time between the trigger signal timing to cryogen injector and the cryogen injection timing onto samples was measured three times and plotted in red, green, and light blue, confirming the freezing time precision of ± 10 ms. 133 ms ± 10 ms delay was observed between triggering the cryogen injector and the moment when the cryogen reaches samples. By advancing the timing of the trigger signal for the cryogen injector relative to that for the UV laser light source, our system enables rapid freezing at any desired timing with the time precision of ± 10 ms under optical stimulation. b Schematics of the time course of Ca2+ signal triggering and cryofixation, and the time course of the change of fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4 at the line indicated by the red arrows in the frame of the X-Y image at −13,410 ms, and X-Y images at different times. Ca2+ propagation stopped at 120 ms after UV light irradiation by cryofixation (Video S4). c, d Cryofixation of the neonatal rat cardiomyocytes loaded with Fluo-4 during contraction and relaxation phases (Video S5). Liquid cryogen was provided onto the sample manually for C and D. The fluorescence images were acquired at a frame rate of 100 frames s−1 in all data

As further examples, Fig. 2c, d show that we can selectively apply the cryogen at contraction or relaxation phases in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, allowing the possibility to arrest heartbeat motion triggered by the cells (Video S5, “Materials and Methods”). Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were loaded with Fluo-4, and an increase in the free Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm during the contraction of the heartbeat motion, known as a Ca2+ transient, was observed. As shown in Fig. 2c, d, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were frozen at the rising (contraction phase) and falling (relaxation phase) time points of fluorescence intensity.

Improved quantitative measurement

Molecules under cryogenic conditions exhibit an enhanced chemical stability, which can be exploited for quantitative measurements. Quantifying dynamic samples has several challenges under ambient conditions but becomes significantly easier under cryogenic conditions. While previous studies have reported increased optical stability of fluorescent probes under cryogenic conditions31–36, the optical properties and quantitative imaging performance of Fluo-4 and a ratiometric fluorescent Ca2+ probe, yellow cameleon 3.60 (YC3.60)50, have not been previously explored.

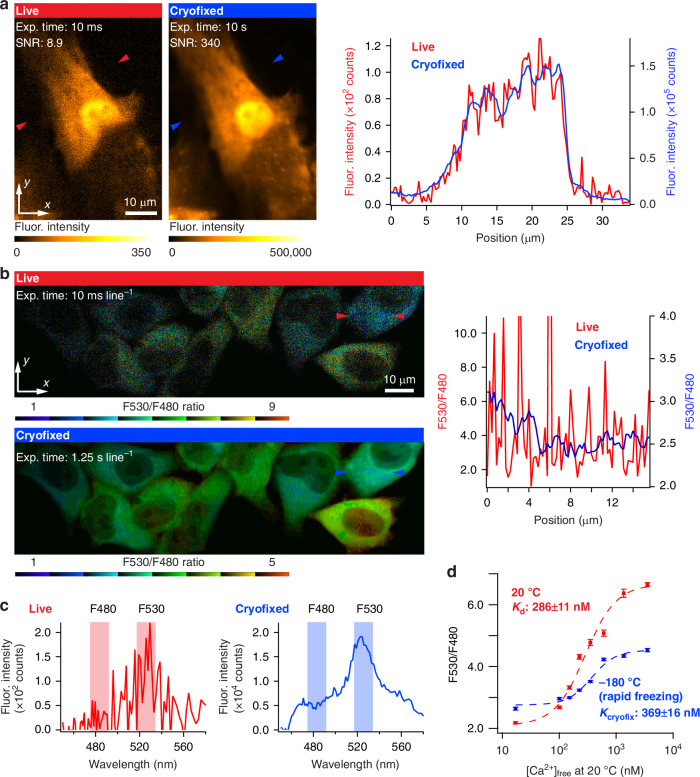

As demonstrated in Fig. 3a, long-time exposure of a cryofixed sample produced a higher SNR in fluorescence imaging of Ca2+ distribution using Fluo-4, compared to limited exposure times in dynamics imaging under living conditions (Fig. 3a, “Materials and Methods”). Improved resistance of Fluo-4 to photobleaching under cryogenic conditions was also beneficial for improving the SNR in Ca2+ imaging (Fig. S17). The improvement in the SNR generates a corresponding increase in the quantification capability of the experiment. For example, a Ca2+ measurement accuracy of 0.2 nM can be achieved using Fluo-4 with 10 s exposure under −170 °C, demonstrating a 17-fold improvement compared to measurement conditions that could be used in live cell imaging (33 ms here, at 20 °C) (Fig. S18).

Fig. 3.

Image quantification ability is improved by ultra-rapid fixation and cryogenic imaging. a Fluorescence images of Fluo-4 loaded neonatal rat cardiomyocyte and fluorescence intensity line profiles of the lines indicated by the red and blue arrows in the fluorescence images. By increasing the exposure time by a factor of 1000, the SNR was improved from 8.9 to 340. The experimental data are the same as that shown in Fig. 1b. The fluorescence image of the cryofixed sample with the exposure equivalent to 10 s was generated by integrating 1000 fluorescence images with an exposure time of 10 ms under cryogenic conditions. b Ratiometric fluorescence images of HeLa cells expressing YC3.60 acquired with a slit-scanning hyperspectral fluorescence microscope before and after cryofixation. Here, we utilized MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices) to generate the ratiometric image using 8 shades of color in a look-up table shown at the bottom of the image. To facilitate the identification of cellular morphology, the intensities of each color in the image were adjusted to correspond with fluorescence intensities observed in the fluorescence image of Venus. Fluorescence ratio line profiles are also shown for the lines indicated by the red and blue arrows in the ratio images. The ratio values in the line profiles were calculated from the fluorescence intensity images of ECFP and Venus (Fig. S20). Similar to (a), the fluorescence image with the equivalent long exposure time under cryogenic conditions was generated by the integration of 125 fluorescence images with an exposure time of 10 ms line−1. c Representative fluorescence spectra of YC3.60 in the sample shown in (b). The increase of the exposure time allows us to improve SNR in the spectrum measurement. d Ca2+ titration curve of YC3.60 before and after cryofixation, which was measured by using YC3.60 dispersed in Ca2+ calibration buffer solution

We also examined YC3.60, which is cyan fluorescent protein, ECFP, paired with yellow fluorescent protein, Venus, via Ca2+-sensitive calmodulin50. The optical property and imaging performance of YC3.60 under cryogenic conditions, like those of Fluo-4, have not been explored previously. Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between ECFP and Venus is facilitated by the capture of Ca2+ by calmodulin, and the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of ECFP and Venus can quantitatively measure the Ca2+ concentration in cells. Figure 3b shows a ratiometric fluorescence image of HeLa cells expressing YC3.60 in the cytosol and fluorescence ratio profiles obtained from the lines indicated by red and blue arrows in Fig. 3b, acquired using a slit-scanning hyperspectral fluorescence microscope (Fig. S19, “Materials and Methods”). The cells were cryofixed at 36 s after histamine stimulation. Long-time exposure under cryogenic conditions allowed us to measure the fluorescence spectrum of YC3.60 with a higher SNR, as shown in Fig. 3c, providing a high quantification capability for Ca2+ imaging. We also measured the calcium response of YC3.60 under the room temperature and cryogenic conditions at −180 °C after the rapid freezing mentioned above. We found that the YC3.60 performed effectively at cryogenic conditions over a useful range of calcium concentrations (several tens of nanomolars to micromolar range).

After demonstrating the applicability of the technique for calcium measurements, we compared the sigmoidal response curves of the probe after rapid freezing with that of room temperature and found a slight difference of the Kd and Kcryofix values, and a change in FRET efficiency (Fig. 3d, “Materials and Methods”). Although further investigations are needed to clarify the mechanism behind the change in fluorescence ratio after rapid freezing, this might be explained by changes in physicochemical properties, such as the increase in FRET efficiency due to the elongated fluorescence lifetime under low temperatures, a larger increase in the quantum yield of ECFP compared to that of Venus, changes in the emission spectrum shapes and possibly absorption spectrum shapes (Figs. S21–S23). Despite the changes in these physicochemical properties, ratiometric imaging at a high SNR for the quantification of Ca2+ concentration was achieved, indicating that various FRET-based probes can also be used with time-deterministic cryo-optical microscopy. The fluorescence ratio in cryogenic cell imaging was lower than those shown in the Ca2+ titration curve, which we attribute to the difference in the surrounding environmental conditions of YC3.60 in HeLa cells and the Ca2+ calibration buffer solution.

Multimodal imaging capability with a different temporal resolution

Time-deterministic cryofixation is also useful for multimodal studies because switching between different modalities does not cause a time discrepancy between modes and provides the same precise snapshot in time, even when using modalities with different temporal resolutions, such as fluorescence and Raman microscopy (Fig. S24, “Materials and Methods”). Here, we demonstrated this by multimodal imaging of the same state of HeLa cells using fluorescence 3D-SIM and slit-scanning Raman microscopy (Fig. 4, Fig. S25, “Materials and Methods”).

Fig. 4.

Cryogenic spontaneous Raman and super-resolution fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells. The super-resolution fluorescence image of actin filaments was taken with 3D-SIM and shown in yellow color. Raman intensities at 750, 1680, and 2850 cm−1 are mapped, representing the distributions of cytochromes (green), protein (blue), and lipid (red), respectively

A custom-built on-stage freezing chamber equipped with a cooling block was employed, enabling rapid freezing of cellular samples and subsequently maintaining a low temperature during spontaneous Raman imaging51 (Fig. S24, “Materials and Methods”), which typically requires relatively long image acquisition time, such as a few tens of minutes, due to the inherently small Raman scattering cross-section of cellular intrinsic molecules.

After cryofixation of HeLa cells, a super-resolution fluorescence image of actin filaments and high-resolution Raman images of cytochrome, protein, and lipid distributions were acquired. As shown in Fig. 4, Raman microscopy clearly visualized the spatial distribution of cytochromes, proteins, and lipids in cryofixed HeLa cell. The Raman images were reconstructed using Raman signals at 750 cm−1 (porphyrin breathing of cytochromes), 1680 cm−1 (amide-I of protein), and 2850 cm−1 (symmetric CH2 of lipids), respectively. Actin filaments in HeLa cells were labeled with SPY555 in the same manner, as shown in Fig. 1e. The image acquisition times for fluorescence 3D-SIM and slit-scanning Raman microscopy were 0.75 s and 25 min, respectively. Our simulation confirmed that the temperature increase during Raman imaging is ~1 °C, which would not cause any notable damage to the sample (Fig. S26). Although only two microscope imaging modalities were used in this study, a wide variety of optical microscope modalities, such as autofluorescence and coherent Raman imaging techniques, can be added, allowing us to increase multiplexing of observation targets or add further orthogonal imaging data52.

Discussion

We demonstrated rapid freezing of living cells under observation by optical microscopy, in which the morphological, calcium ion, and chemical dynamics of the cells were fixed. This technique also demonstrated continuous observation of the sample with a temporal resolution of 10 ms before and after the moment of cryofixation, providing accurate spatio-temporal information on cellular dynamics and conditions immediately prior to freezing. Combining this spatiotemporal information with high spatial resolution and from cryofixed samples could offer a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of biological events. The accurate and detailed data obtained with this technique could also be useful as the ground truth for machine learning approaches53. In this study, we also demonstrated the precise determination of time interval (± 10 ms precision) between the initiation of cellular dynamics and its cryofixation under optical microscopy observation. This was achieved using the electrically controlled cryogen injector in conjunction with the optical stimulation technique.

One of the remarkable findings of this study is that the Kd value of fluorescent Ca2+ probes is maintained after rapid freezing, which indicates that the molecular-level interactions in the cell can be frozen without passing through a thermal equilibrium state. Therefore, our results suggest that rapid freezing can stop chemical reactions and can be effective for the selection of and study of chemical dynamics at a precise immobilization timepoint. As shown by the fixation of the 3D Ca2+ distribution, this technique can also be extended to fix the activities of other ions, including those for membrane potential and signaling molecules. This technique can be used to fix states of the cell that relate to otherwise intangible information such as pH, redox state, and temperature, which can be detected using functional fluorescent probes1–3.

In this study, we also observed that change in the optical properties of fluorescent probes under cryogenic conditions varies depending on the type of probes and their surrounding environments. This variability makes it important to confirm the optical properties in advances and to conduct careful analysis of observation results. For example, the difference of fluorescence intensity increases between the nucleus and cytoplasm regions after cryofixation, which was observed in the experiments for cryofixation of Ca2+ wave propagating in cells (Figs. 1b, S6), might be attributed to differences in surrounding environment of Fluo-4. Previous reports indicated that the optical property of negative charged Ca2+ indicators, including Fluo-4, is different in the nucleus and cytoplasm in living conditions54,55. This fact indicates the need for careful caution when analyzing spatial intensity distributions within cells. Additionally, similar caution may also be required when analyzing samples labeled with multiple kinds of fluorescent probes, as change of the optical properties of each probe could be different, potentially affecting the interpretation of results. However, it is important to note that such caution is not exclusive to cryogenic conditions; it is always necessary when using fluorescent probes, as their optical properties can be influenced by various surrounding conditions even at room temperatures, as mentioned above.

As demonstrated by cryo-TEM observations, simply pouring the liquid cryogen onto samples is effective for rapidly freezing samples without causing severe ice crystal formation. Our experiments confirmed that, even without the use of cryoprotectants, no crystalline ice was observed in two of three lamellae, each containing a cell and buffer solution (Fig. S4). Although small ice crystals were observed within cells in the remaining cellular lamella, approximately 93% of the total area was vitrified, and crystal sizes were comparable to those seen in samples frozen by plunge freezing. As with plunge freezing and high-pressure freezing, the addition of cryoprotectant, such as glycerol, may further reduce the formation of crystalline ice within cells56. This approach may be preferable when applying our method to higher spatial resolution techniques, such as SMLM7–9, STED microscopy10, minimum photon flux (MINFLUX) microscopy11, correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM), and computational approaches57–59. Future developments in accurate buffer volume control devices could help to improve cooling conditions, potentially reducing ice crystal formation even without the use of cryoprotectants. In addition, while technically challenging both in implementation on an optical microscope stage and in achieving high cooling rate, high-pressure freezing techniques60,61 as an alternative to the current freezing method could enhance the preservation quality of cellular structures and molecular distributions by effectively suppressing ice crystal formation, enabling more precise high-resolution imaging.

Although the main target of this research is time-deterministic fixation for optical microscopy, the open-top design also facilitates sample processing after freezing. For example, subsequent freeze substitution, staining, and resin embedding62 are all enabled by this design. Developing a device that can exchange liquid cryogen, which is maintained on a sample after rapid freezing, with freeze substitution media while maintaining the sample at cryogenic temperatures remains essential. The open-top and simple construction of our sample freezing chamber is expected to be advantageous for this development. Combination with electron microscopy also holds many potential advantages; however, depending on the application, it is necessary to investigate the freezing characteristics and the capability to preserve ultrastructural integrity.

Analysis of cellular dynamics and related functions using the rapid freezing techniques under optical microscopy observations still remains a largely unexplored field with many challenges and points requiring careful interpretation. However, as demonstrated and discussed in this paper, the potential benefits of this technique are significant. Compared with chemical fixation, cryofixation produces fewer morphological and chemical artifacts15,18,19. In addition, chemical environments such as ion distributions, pH, and redox conditions may also be fixed, allowing a more detailed investigation of chemical responses that govern biological phenomena. The rapid freezing can even immobilize the states of both endogenous and exogenous molecules, such as fluorescent indicators, providing snapshots of molecular behavior at a moment of interest. Therefore, by exploiting the rapid freezing techniques under optical microscopy observations, detailed visualization of chemically unfixable targets, such as ions or other signaling messengers, as well as other observation targets at specific moments of cellular dynamics would become possible, allowing for more detailed understanding of their intracellular distribution and interaction without being limited by short exposure times needed for traditional time-resolved imaging. This advantage is also significantly beneficial for enhancing the imaging performance of super-resolution fluorescence microscopy7–12 which can benefit greatly from relaxing constraints on acquisition times. The concept and design of fluorescent probes can also be altered when considering the usage and optimization of their performances under cryogenic conditions. This technique is also useful for improving the detection sensitivities of optical techniques that require the detection of low-light signals, such as Raman microscopy. Cryogenic Raman imaging using Raman tags can be used to observe low concentrations of small molecules in live cells that are difficult to observe using fluorescence labeling63,64. Further improvement in SNR and detection sensitivities could be achieved if an immersion objective lens with a high numerical aperture is used, which allows us to improve the spatial resolution65–67. Moreover, the implementation of adaptive optics can further optimize the spatial resolution and signal levels.

Although various challenges still remain in our technique as discussed above, the techniques presented in this paper demonstrated a significant advancement in terms of ability for rapid and time-deterministic immobilization of cellular dynamics under optical microscopy observation. The simplicity and user-friendliness of on-stage rapid freezing technique facilitate practical usage of cryogenic optical microscopy, broadening its application across a wide range of research fields relying on optical microscopy. This advancement also has the potential to stimulate further development of various techniques related to cryogenic optical imaging.

Materials and methods

The materials and methods are described below, with further experimental details provided in the Supplementary Information.

On-stage freezing chamber

The sample freezing chamber consisted of three parts: top, middle, and bottom mounts, as shown in Fig. 1a. A sample coverslip was placed in the indented area of the bottom mount and held by pressing it down from above. The top mount was equipped with two hinges. After a sample is mounted, it can then be cryofixed by applying liquid cryogen from the upper side, and the sample freezing chamber allows the storage of liquid cryogen during observation. The area between the sample coverslip and the objective lens was filled with nitrogen gas, which was kept in a chamber with a plastic sheet and an objective-lens-sized hole in the center to prevent frost condensation due to low temperatures. This simple design facilitates easy handling of this sample freezing chamber, significantly reducing the time required to exchange a sample to approximately 30-60 s by using spare mounts. This sample freezing chamber can be attached to any type of standard inverted microscope stage using appropriate adapters.

A sample (cells on a 10 × 10 mm, 18 × 18 mm, or 25 mm diameter quartz coverslip (thickness of 0.17 ± 0.02 mm)) was removed from the cell culture medium or a buffer solution in a cell culture dish, and the liquid on the bottom side of the coverslip was carefully wiped off with paper such as lens cleaning paper with ethanol. Immediately thereafter, the sample was mounted in an on-stage freezing chamber, and a buffer solution, such as Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), was added to prevent the sample from drying out while it was being prepared for measurement.

The experimental data shown in this paper were obtained using a Nikon Ti2-E microscope. After completing the measurement preparation and activating the axial autofocus system of the Ti2-E microscope, the buffer solution was aspirated using a pipette. Under an optical microscope, liquid cryogen was applied to freeze a sample at any given time, such as when Ca2+ waves or Ca2+ transients occur.

Liquid cryogen

For our experiments, a mixture of liquid isopentane and propane (temperature: about −185 °C, ratio of isopentane to propane: 1:2–1:3) was mainly used. By mixing isopentane and propane, the freezing point is lowered, allowing us to handle the cryogen more easily while it remains in liquid even after more than 30 min of cooling with liquid nitrogen (LN2)68. Only for multimodal imaging (Fig. 4), liquid propane (temperature: about −185 °C) was used.

Optical microscopy setups

Four optical microscopy modalities were employed in this study: a widefield fluorescence microscope, a structured illumination microscopy (SIM) system, a hyperspectral slit-scanning fluorescence microscope, and a multimodal system combining SIM with slit-scanning Raman microscopy. The base platform was a Nikon Ti2-E inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a mercury lamp and sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, ORCA Flash4.0 V3). An axial autofocus system was activated to maintain image focus during observations.

For SIM imaging, a laser excitation path and a reflective-type spatial light modulator were added to the widefield microscope to generate structured illumination patterns on samples (Fig. S10). To acquire a single X-Y image using 3D-SIM microscopy, 15 images of a sample were acquired using structured illumination at three different illumination angles with five phase shifts per angle, which were then reconstructed into a SIM image. For 3D volumetric SIM imaging, this process was repeated at different Z-positions by changing the Z-direction offset position of the autofocus function of a Nikon Ti2-E microscope, and the resultant image stack was used to construct a 3D-SIM volumetric image. Fluo-4 (AAT Bioquest, 20550 or Chemical Dojin, 342-90961) and the live-cell F-actin probe SPY-555-actin (Spirochrome, SC202) were excited using 488-nm and 561-nm lasers, respectively. Fluorescence signals were detected using the sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, ORCA Flash4.0 V3), which was also used for widefield imaging.

For slit-scanning hyperspectral fluorescence imaging, the widefield microscope was modified to include a 405-nm laser excitation path to generate a line illumination, along with a spectrometer equipped with an electron multiplying charged-coupled device (EMCCD) camera (Princeton Instruments, Pro-EM:1024) (Fig. S19). Fluorescence spectra were acquired via line-illumination and slit-confocal detection and were subsequently used to reconstruct fluorescence images.

The multimodal system extended the SIM microscope with an additional optical setup for a slit-scanning Raman microscopy (Fig. S24). The setup included a 532 nm laser excitation path for line illumination and a spectrometer (Bunkoukeiki, MK-300) equipped with a cooled CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, PIXIS:400BR). After SIM imaging, Raman spectra from a sample were recorded and used to reconstruct Raman images.

Cellular sample preparations

Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were cultured on gelatin-coated coverslips, whereas HeLa cells and COS-7 cells were cultured on uncoated coverslips. The culture medium was Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% PSG antibiotic mix (100 U mL−1 penicillin, 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine).

For Ca2+ imaging of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, the cells were washed three times with HBSS, immersed in Fluo-4 (AAT Bioquest, 20550 or Chemical Dojin, 342-90961) staining solution, and then washed again three times prior to imaging. For dual color imaging of Ca2+ and F-actin, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were pre-stained with the live-cell F-actin probe SPY-555-actin (Spirochrome, SC202), followed by Fluo-4 staining. To perform Ca2+ imaging with a caged calcium compound (Tocris, DMNPE-4 AM-caged calcium, 5948), the cells were loaded with the mixture of Fluo-4 and the caged calcium compound following the same protocol as Fluo-4 staining. Ratiometric Ca2+ imaging of HeLa cells was conducted with stably expressing YC3.60 in the cytosol.

For organelle observation, mitochondria in HeLa cells were labeled by using pcDNA3 encoding DsRed. HeLa cells were imaged 1 day after transfection. To observe lysosomes in COS-7 cells, the cells were incubated with the live-cell lysosome probe LysoTracker Red NDN-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L7528), then washed three times before imaging.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST-CREST and JST COI-NEXT program under Grant number JPMJCR1925 and JPMJPF2009. This work was also partially supported by JST SPRING under Grant number JPMJSP2138, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB1278 (TP C04), and the Leibniz Association (Leibniz Science Campus, InfectoOptics, HotAim 2.0). M.C.W. was supported by Janelia Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The authors thank M. Hayakawa for the isolation of cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats, S. Kawano for the development of SIM software, and S. Sakakihara for the preparation of SIM masks. The authors also acknowledge the Visiting Scientist Program at Janelia Research Campus and the Cryo-EM facility at Janelia Research Campus for the sample preparation and cryo-TEM data collection.

Author contributions

K.F. conceived the idea of the on-stage rapid freezing and designed research. K.T., M.Y., Y.K., S.T., W.M., T.Kubo, K.Mizushima, K.K., H.H., M.S., X.Z., H.X., T.Kunimoto, Y.T., K.N., Z.Y., M.C.W., and K.F. performed research. K.T., S.T., T.Kubo, K.S., S.F., K.Mochizuki, Y.H., R.H., T.N., and H.T. contributed new reagents or analytic tools. K.T., M.Y., W.M., T.Kubo, K.Mizushima, K.K., H.H., X.Z., S.F., T.Kunimoto, and N.I.S. analyzed data. K.T., M.Y., S.T., W.M., T.Kubo, K.Mizushima, M.S., X.Z., N.I.S., R.H., Z.Y., T.N., and K.F. wrote the paper. The authors are listed here in the same order as they appear in the author list.

Data availability

All original data used in this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

K.F. and Y.K. are inventors on the patent related to this work (application number: PCT/JP2022/020045, applicant: The University of Osaka, publication date: 17 November 2022, publication number: WO 2022/239830 A1), and PCT national phase applications have been filed in the United States, Japan, Europe, and China. K.F., M.Y., Y.K., and K.T. have patent applications (application number: PCT/JP2023/038854, applicant: The University of Osaka). K.F. is a co-founder and the chief technology officer (CTO) of Millde Co., Ltd. The authors declare no additional conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Kosuke Tsuji, Masahito Yamanaka

Contributor Information

Masahito Yamanaka, Email: yamanaka@ap.eng.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Katsumasa Fujita, Email: fujita@ap.eng.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41377-025-01941-8.

References

- 1.Kneen, M. et al. Green fluorescent protein as a noninvasive intracellular pH indicator. Biophys. J.74, 1591–1599 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lou, Z. R., Li, P. & Han, K. L. Redox-responsive fluorescent probes with different design strategies. Acc. Chem. Res.48, 1358–1368 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vu, C. Q. et al. A highly-sensitive genetically encoded temperature indicator exploiting a temperature-responsive elastin-like polypeptide. Sci. Rep.11, 16519 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morishita, Y. et al. Generation of myocyte agonal Ca2+ waves and contraction bands in perfused rat hearts following irreversible membrane permeabilisation. Sci. Rep.13, 803 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almada, P. et al. Automating multimodal microscopy with NanoJ-Fluidics. Nat. Commun.10, 1223 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles, A. C. et al. Intercellular signaling in glial cells: calcium waves and oscillations in response to mechanical stimulation and glutamate. Neuron6, 983–992 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rust, M. J., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. W. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods3, 793–796 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betzig, E. et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science313, 1642–1645 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavani, S. R. P. et al. Three-dimensional, single-molecule fluorescence imaging beyond the diffraction limit by using a double-helix point spread function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA106, 2995–2999 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett.19, 780–782 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balzarotti, F. et al. Nanometer resolution imaging and tracking of fluorescent molecules with minimal photon fluxes. Science355, 606–612 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustafsson, M. G. L. et al. Three-dimensional resolution doubling in wide-field fluorescence microscopy by structured illumination. Biophys. J.94, 4957–4970 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohno, N., Terada, N. & Ohno, S. Histochemical analyses of living mouse liver under different hemodynamic conditions by “in vivo cryotechnique”. Histochem. Cell Biol.126, 389–398 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terada, N. et al. Application of “in vivo cryotechnique” to detect erythrocyte oxygen saturation in frozen mouse tissues with confocal Raman cryomicroscopy. J. Struct. Biol.163, 147–154 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilkey, J. C. & Staehelin, L. A. Advances in ultrarapid freezing for the preservation of cellular ultrastructure. J. Electron Microsc. Tech.3, 177–210 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowall, A. W. et al. Electron microscopy of frozen hydrated sections of vitreous ice and vitrified biological samples. J. Microsc.131, 1–9 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saibil, H. R. Cryo-EM in molecular and cellular biology. Mol. Cell82, 274–284 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhaus, E. M. et al. Ethane-freezing/methanol-fixation of cell monolayers: a procedure for improved preservation of structure and antigenicity for light and electron microscopies. J. Struct. Biol.121, 326–342 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laporte, M. H. et al. Visualizing the native cellular organization by coupling cryofixation with expansion microscopy (Cryo-ExM). Nat. Methods19, 216–222 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufmann, R. et al. Super-resolution microscopy using standard fluorescent proteins in intact cells under cryo-conditions. Nano Lett.14, 4171–4175 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang, Y. W. et al. Correlated cryogenic photoactivated localization microscopy and cryo-electron tomography. Nat. Methods11, 737–739 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisenburger, S. et al. Cryogenic optical localization provides 3D protein structure data with Angstrom resolution. Nat. Methods14, 141–144 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahlberg, P. D. et al. Cryogenic single-molecule fluorescence annotations for electron tomography reveal in situ organization of key proteins in Caulobacter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA117, 13937–13944 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips, M. A. et al. CryoSIM: super-resolution 3D structured illumination cryogenic fluorescence microscopy for correlated ultrastructural imaging. Optica7, 802–812 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kounatidis, I. et al. 3D correlative cryo-structured illumination fluorescence and soft X-ray microscopy elucidates reovirus intracellular release pathway. Cell182, 515–530.e17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman, D. P. et al. Correlative three-dimensional super-resolution and block-face electron microscopy of whole vitreously frozen cells. Science367, eaaz5357 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moser, F. et al. Cryo-SOFI enabling low-dose super-resolution correlative light and electron cryo-microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 4804–4809 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mony, M. C. & Larras-Regard, E. Imaging of subcellular structures by scanning ion microscopy and mass spectrometry. Advantage of cryofixation and freeze substitution procedure over chemical preparation. Biol. Cell89, 199–210 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perrin, L. et al. Evaluation of sample preparation methods for single cell quantitative elemental imaging using proton or synchrotron radiation focused beams. J. Anal. Spectrom.30, 2525–2532 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu, H. N. et al. Optical redox imaging of fixed unstained muscle slides reveals useful biological information. Mol. Imaging Biol.21, 417–425 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahlberg, P. D. et al. Identification of PAmKate as a red photoactivatable fluorescent protein for cryogenic super-resolution imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc.140, 12310–12313 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hulleman, C. N. et al. Photon yield enhancement of red fluorophores at cryogenic temperatures. ChemPhysChem19, 1774–1780 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, W. X. et al. Ultra-stable and versatile widefield cryo-fluorescence microscope for single-molecule localization with sub-nanometer accuracy. Opt. Express23, 3770–3783 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baskin, T. I. et al. Cryofixing single cells and multicellular specimens enhances structure and immunocytochemistry for light microscopy. J. Microsc.182, 149–161 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufmann, R., Hagen, C. & Grünewald, K. Fluorescence cryo-microscopy: current challenges and prospects. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.20, 86–91 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz, C. L. et al. Cryo-fluorescence microscopy facilitates correlations between light and cryo-electron microscopy and reduces the rate of photobleaching. J. Microsc.227, 98–109 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu, B. et al. Three-dimensional super-resolution protein localization correlated with vitrified cellular context. Sci. Rep.5, 13017 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez, D. et al. Exploring transient states of PAmKate to enable improved cryogenic single-molecule imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 28707–28716 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez, D. et al. Identification and demonstration of roGFP2 as an environmental sensor for cryogenic correlative light and electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol.214, 107881 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masip, M. E. et al. Reversible cryo-arrest for imaging molecules in living cells at high spatial resolution. Nat. Methods13, 665–672 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuest, M. et al. Cryofixation during live-imaging enables millisecond time-correlated light and electron microscopy. J. Microsc.272, 87–95 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuest, M. et al. In situ microfluidic cryofixation for cryo focused ion beam milling and cryo electron tomography. Sci. Rep.9, 19133 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huebinger, J. et al. Ultrarapid cryo-arrest of living cells on a microscope enables multiscale imaging of out-of-equilibrium molecular patterns. Sci. Adv.7, eabk0882 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubochet, J. & McDowall, A. W. Vitrification of pure water for electron microscopy. J. Microsc.124, 3–4 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woodruff, M. L. et al. Measurement of cytoplasmic calcium concentration in the rods of wild-type and transducin knock-out mice. J. Physiol.542, 843–854 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsukamoto, S. et al. Simultaneous imaging of local calcium and single sarcomere length in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes using yellow Cameleon-Nano140. J. Gen. Physiol.148, 341–355 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas, D. et al. A comparison of fluorescent Ca2+ indicator properties and their use in measuring elementary and global Ca2+ signals. Cell Calcium28, 213–223 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, F., Tillberg, P. W. & Boyden, E. S. Expansion microscopy. Science347, 543–548 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellis-Davies, G. C. R. & Barsotti, R. J. Tuning caged calcium: photolabile analogues of EGTA with improved optical and chelation properties. Cell Calcium39, 75–83 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagai, T. et al. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA101, 10554–10559 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mizushima, K. et al. Raman microscopy of cryofixed biological specimens for high-resolution and high-sensitivity chemical imaging. Sci. Adv.10, eadn0110 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng, J. X. & Xie, X. S. Vibrational spectroscopic imaging of living systems: an emerging platform for biology and medicine. Science350, aaa8870 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greener, J. G. et al. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.23, 40–55 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gee, K. R. et al. Chemical and physiological characterization of fluo-4 Ca2+-indicator dyes. Cell Calcium27, 97–106 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Terzic, C., Stehno-Bittel, L. & Clapham, D. E. Nucleoplasmic and cytoplasmic differences in the fluorescence properties of the calcium indicator Fluo-3. Cell Calcium21, 275–282 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bäuerlein, F. J. B. et al. Cryo-electron tomography of large biological specimens vitrified by plunge freezing. Print at 10.1101/2021.04.14.437159 (2023).

- 57.Zhao, W. S. et al. Sparse deconvolution improves the resolution of live-cell super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 606–617 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mo, Y. Q. et al. Quantitative structured illumination microscopy via a physical model-based background filtering algorithm reveals actin dynamics. Nat. Commun.14, 3089 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cao, R. J. et al. Dark-based optical sectioning assists background removal in fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods. 10.1038/s41592-025-02667-6 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Moor, H. & Riehle, U. “Snap-freezing under high pressure: a new fixation technique for freeze-etching” in Electron microscopy 1968, vol. 2 Proc. 4th Eur. Reg. Conf. Electron Microsc., Rome, D. Steve Bocciarelli, Eds. pp 33-34.

- 61.Dahl, R. & Staehelin, L. A. High-pressure freezing for the preservation of biological structure: theory and practice. J. Electron Microsc. Tech.13, 165–174 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buser, C. et al. Quantitative investigation of murine cytomegalovirus nucleocapsid interaction. J. Microsc.228, 78–87 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dodo, K., Fujita, K. & Sodeoka, M. Raman spectroscopy for chemical biology research. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 19651–19667 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen, C. et al. Multiplexed live-cell profiling with Raman probes. Nat. Commun.12, 3405 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faoro, R. et al. Aberration-corrected cryoimmersion light microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA115, 1204–1209 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nahmani, M. et al. High-numerical-aperture cryogenic light microscopy for increased precision of superresolution reconstructions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA114, 3832–3836 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang, L. et al. Solid immersion microscopy images cells under cryogenic conditions with 12 nm resolution. Commun. Biol.2, 74 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jehl, B. et al. The use of propane/isopentane mixtures for rapid freezing of biological specimens. J. Microsc.123, 307–309 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All original data used in this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.