Abstract

Climate change amplifies temperature variability, thereby subjecting organisms to increased stress as they more frequently encounter temperatures outside their optimal range. Temperature influences resource distribution across fundamental processes in organisms, such as metabolism, reproduction and overall fitness, yet energy allocation strategies are primarily understood under stable temperature conditions. Predicting organisms’ responses to fluctuating temperatures, however, remains challenging. To address this gap, we develop an allometric growth model to predict energy allocation between growth and reproduction under both constant and variable temperature conditions. The model predictions perform and align well with the observed growth patterns of Daphnia magna, a keystone species in aquatic ecosystems, exposed to various thermal scenarios. Results indicate that exposure to unpredictable temperatures elicits growth and reproduction responses similar to those observed under consistently high temperatures. However, individuals exposed to unpredictable temperatures incur a disproportionate energetic cost compared to those in constant average or low-temperature conditions, significantly reducing estimated fecundity over time and lifespan. These findings highlight the relative energetic impacts of increased unpredictability in temperature and underline its critical role in shaping life-history traits. Given the growing concern over modern climate change scenarios, the allometric growth model provides a straightforward yet essential approach for integrating energetic and subsequent ecological effects, enabling not only predictions of responses across keystone species but also an enhanced understanding of anthropogenic impacts on aquatic ecosystems.

Subject terms: Differential equations, Power law, Statistical methods, Climate-change ecology, Freshwater ecology

Introduction

Temperature plays a fundamental role in shaping resource allocation patterns by influencing metabolic demands, energy budgets and trade-offs between growth, reproduction and maintenance1. As temperature increases, metabolic rates typically rise2, leading to greater energy expenditure on maintenance and activity at the expense of growth and reproductive investment. This shift often results in reduced body size, a phenomenon known as the temperature-size rule, where individuals mature earlier but at smaller sizes3. Further, warmer temperatures can favour increased reproductive output in some species, while others may experience constraints due to elevated metabolic costs. In contrast, colder environments often promote energy storage strategies, with greater allocation to lipid reserves to enhance survival during resource-scarce periods1. Temperature-driven shifts in resource allocation underpins responses in life-history traits4 which have significant ecological and evolutionary implications, influencing population dynamics, species interactions, and overall ecosystem function, particularly in the face of climate change5.

Species often respond to predictable changes in mean temperature by adjusting the reproductive cycles and brood sizes to maximise fitness6. However, responses to increased temperature variability and its associated unpredictability introduce further challenges nonetheless7. Although life-history responses to predictable constant temperatures are well-studied and understood, our comprehension remains comparatively limited regarding the effects of unpredictable fluctuation in temperature on energy allocation—and the subsequent trade-offs between reproduction, growth and lifespan8,9. Further, there is no unifying agreement regarding the fitness effects of increase unpredictability, with both positive and negative impacts being reported10. In this study, we address this scientific gap by developing a novel temperature-energy model that quantifies the fitness (reproduction), growth and mortality costs associated with the increased temperature unpredictability forecasted under modern climate change scenarios.

Mathematical models play a pivotal role in comprehending the energy allocation between growth and reproduction, often using surrogate metrics, such as body mass, length and reproduction data11. Energy expenditure on growth and reproduction has been expressed through differential equations rooted in the von Bertalanffy-Pütter differential equation12–14, which specifies growth as a balance between anabolic and catabolic processes. To date, the subsequent model advancements have shifted towards increasingly mechanistic formulations, offering greater biophysical interpretability through parameters, which align with underlying metabolic processes rather than relying solely on phenomenological observations. A key aspect is model exponents, which both distinguish the theoretical underpinnings of model developments (see Kearney 202015 for a comprehensive review) and ensure that the differential equation possesses an analytical solution whereby model parameters can be estimated using body length data.

Previous major model advancements include the Dynamic Energy Budget (DEB) theory16,17, which expresses a rate parameter at which energy assimilation and partition between reproduction, growth and maintenance are specified and related to environmental conditions with organism-specific parameters16–18. The DEB framework has been widely employed to capture the energetic effect of various stressors, including chemical, temperature and food-related factors, on the life-history of freshwater organisms19. In principle, the DEB model differs from the von Bertalanffy-Pütter model, specifying the model terms as assimilation and maintenance costs encompassing anabolic and catabolic processes. This distinction is apparent in the core parameters, which differ depending upon the theoretical framework on which each model stands15. Under constant temperature and resources (i.e. food), the growth curve proposed by the DEB coincides with the von Bertalanffy growth curve on two parameters: (1) the relative growth rate coefficient and (2) the structural length18,20. While these two parameters can be estimated from longitudinal body length data, these are also confounded regarding metabolic aspects by more than two core parameters. Thus, all these core parameters can be mathematically unidentifiable unless some of the parameters are predetermined or estimated from some additional sources. This fact indicates an alternative model refinement, leading to the alteration of the von Bertalanffy-Pütter differential equation, which may incline towards a hybrid model that combine mechanistic and phenomenological approaches, simplifying model parameters while still maintaining meaningful biophysical interpretations.

There is some recognised limitations of using the von Bertalanffy-Pütter equation to estimate the energy component allocated to reproduction21. However, recent model advancements have integrated the energy component allocated to reproduction to be a feature of the allometric scaling model framework22–25. Here, we develop a novel allometric scaling model to capture individual lifetime energy allocation shifts between growth and non-growth components. Model parameters are validated using D. magna exposed to different temperature scenarios (i.e. constant-low, constant-rearing, constant-high and unpredictable temperatures). Combined with our experiments, the proposed model offers several important scientific contributions. First, the model introduces a time-varying rate parameter at which acquired energy is partitioned between growth and reproduction components, illustrating age-dependent transitions. Second, all the model parameters, including the exponents typically predefined in other modelling approaches, are estimable from body length data alone, also bypassing the need of solving the original differential equation. This flexibility enables the model to delineate energy allocated to reproduction without fecundity data, broadening its applicability across species and systems with similar biological traits to our study organism. Importantly, these extensions are achieved by model re-parametrisation accommodating the present experiment design. Finally, our model reveals a more realistic insight into the energy allocation and bioenergetic costs incurred throughout their lifetime under different temperature scenarios, rather than simply studying short or chronic exposures to stress, shedding light on the extent to which species may respond to increasingly unpredictable anthropogenic climate change.

Data and model

Experiment and data

All the individuals used in the experiment were descendants ( ) from the third brood neonates of D. magna clone F26. The parental generation (

) from the third brood neonates of D. magna clone F26. The parental generation ( ) was raised at a constant temperature of 20

) was raised at a constant temperature of 20 C under a 16:8-hour (light:dark) photoperiod in ASTM (American Society for Testing Materials) medium27 and individually fed daily with green algae, Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata, at a concentration of

C under a 16:8-hour (light:dark) photoperiod in ASTM (American Society for Testing Materials) medium27 and individually fed daily with green algae, Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata, at a concentration of  cells

cells  (see ASTM 198028). This concentration was above ad libitum to ensure proportional satiation of energetic requirements across all temperature scenarios. The medium was changed every other day. The temperature, photoperiod and feeding rate used in our cultures follow guideline 211 from the Organization for Economic and Co-operation and Development, which is recommended for reproduction and chemical tests with Daphnia27.

(see ASTM 198028). This concentration was above ad libitum to ensure proportional satiation of energetic requirements across all temperature scenarios. The medium was changed every other day. The temperature, photoperiod and feeding rate used in our cultures follow guideline 211 from the Organization for Economic and Co-operation and Development, which is recommended for reproduction and chemical tests with Daphnia27.

Each  individual was, immediately after birth, randomly placed in an individual 50 ml glass container and allocated to one of four temperature scenarios over their entire life and maintained within a Binder incubator (Binder Bs28). The four temperature scenarios were: constant low (15

individual was, immediately after birth, randomly placed in an individual 50 ml glass container and allocated to one of four temperature scenarios over their entire life and maintained within a Binder incubator (Binder Bs28). The four temperature scenarios were: constant low (15 C), constant rearing (20

C), constant rearing (20 C), constant high (25

C), constant high (25 C), and unpredictable variation (15–25

C), and unpredictable variation (15–25 C, see the supplementary information). The constant rearing temperature refers to the normal temperature at which individuals are kept in the laboratory. The maximum temperature was set at 25

C, see the supplementary information). The constant rearing temperature refers to the normal temperature at which individuals are kept in the laboratory. The maximum temperature was set at 25 C. This value is above the optimal temperature curve for D. magna, thus expected to elicit oxidative stress which will impact growth, reproduction and survival29,30. Under the unpredictable temperature scenario, temperature randomly fluctuated but within different ranges according to three specific time segments every day. From 00:00 to 08:00 and 18:00 to 24:00 (dawn–morning and late afternoon segments), the temperature fluctuated within 15–20

C. This value is above the optimal temperature curve for D. magna, thus expected to elicit oxidative stress which will impact growth, reproduction and survival29,30. Under the unpredictable temperature scenario, temperature randomly fluctuated but within different ranges according to three specific time segments every day. From 00:00 to 08:00 and 18:00 to 24:00 (dawn–morning and late afternoon segments), the temperature fluctuated within 15–20 C; from 08:00 to 18:00 (morning–afternoon segment), it randomly varied within 20–25

C; from 08:00 to 18:00 (morning–afternoon segment), it randomly varied within 20–25 C. This resulted in an overall average of 19.8

C. This resulted in an overall average of 19.8 C, matching the constant rearing temperature. Thus, any deviation in observed growth and reproduction patterns under the unpredictable temperature scenario should be attributed to temperature variability. We obtained data from 628

C, matching the constant rearing temperature. Thus, any deviation in observed growth and reproduction patterns under the unpredictable temperature scenario should be attributed to temperature variability. We obtained data from 628  individuals (high: 157; rearing: 156; low: 158; and unpredictable: 157), each fed as per

individuals (high: 157; rearing: 156; low: 158; and unpredictable: 157), each fed as per  protocol, with the culture medium changed every two days. By providing the same amount of food, we can better isolate the temperature effect because of the fixed amount of energy intake being allocated to growth (

protocol, with the culture medium changed every two days. By providing the same amount of food, we can better isolate the temperature effect because of the fixed amount of energy intake being allocated to growth ( ) and reproduction (

) and reproduction ( ), according to the DEB framework.

), according to the DEB framework.

We measured  body length,

body length,  , for every individual i upon the birth of neonates (

, for every individual i upon the birth of neonates ( ),

),  ; we also recorded

; we also recorded  body length at their birth,

body length at their birth,  , and death,

, and death,  . Time of birth of neonates was considered as the time point when neonates were released and observed in the vial. Note that the time intervals between body length observations are thus uneven, unlike typical time-series data, which will be considered when fitting the model. Each

. Time of birth of neonates was considered as the time point when neonates were released and observed in the vial. Note that the time intervals between body length observations are thus uneven, unlike typical time-series data, which will be considered when fitting the model. Each  individual was placed in a culture cell plate using a 3 ml plastic pipette and photographed to measure the body length (from the tip of the head to the start of the caudal spine) to the nearest micrometres using ImageJ software31 (ver. 1.54g; https://imagej.net/ij/index.html). In addition, we recorded the number of

individual was placed in a culture cell plate using a 3 ml plastic pipette and photographed to measure the body length (from the tip of the head to the start of the caudal spine) to the nearest micrometres using ImageJ software31 (ver. 1.54g; https://imagej.net/ij/index.html). In addition, we recorded the number of  individuals,

individuals,  , for each brood,

, for each brood,  . The experiment was continued until the last

. The experiment was continued until the last  individual died. We recorded, immediately after emergence, more than 130,000 neonates across all four scenarios.

individual died. We recorded, immediately after emergence, more than 130,000 neonates across all four scenarios.

Modelling

Under specific assumptions body mass can be used to estimate patterns of growth rate under variants of Pütter equation12 that include the von Bertalanffy13, the Gompertz32 and other logistic growth models as special cases. However, body mass can be converted to body length, another common unit, under some assumptions. There is some variability in how body length scales with mass, however, most studies on Daphnia suggest using a cubic transformation33–35. The growth model here combines the knowledge from the DEB theory and a recently proposed modelling framework25, and its extension hinges upon two aspects: 1) the model introduces a time-varying rate parameter, later denoted as  , at which acquired energy is partitioned into growth and reproduction components over a lifetime; and 2) all the model parameters, including the time-varying rate parameter, can be estimated solely from body length data. The new model discussed here is constructed in two steps. First, the model is developed and specified as a general form based on body mass. Second, the proposed body mass model is then converted into a unit of length.

, at which acquired energy is partitioned into growth and reproduction components over a lifetime; and 2) all the model parameters, including the time-varying rate parameter, can be estimated solely from body length data. The new model discussed here is constructed in two steps. First, the model is developed and specified as a general form based on body mass. Second, the proposed body mass model is then converted into a unit of length.

Body mass model

We consider the following differential equations to describe individual body mass  at age t, which is made up of the somatic

at age t, which is made up of the somatic  and gonadic

and gonadic  masses, in allometric forms viz.

masses, in allometric forms viz.

|

1a |

|

1b |

|

1c |

We assume that the gonadic mass is zero,  , at times of the individual’s birth (

, at times of the individual’s birth ( ) and of

) and of  neonates’ birth (

neonates’ birth ( ). In standard allometric equations, each model term comprises somatic mass

). In standard allometric equations, each model term comprises somatic mass  and two parameters: the exponent (i.e.

and two parameters: the exponent (i.e.

and

and  ) that describes how the parameter scales over different values of body mass; and the multiplier (i.e.

a, b and c) that often refers to a parameter independent of body mass. Eq. (1a) states a constraint that the somatic and gonadic masses must be the total mass. Equations (1b)–(1c) describe the energy allocation mechanism of individuals. Equation (1b) consists of three components:

) that describes how the parameter scales over different values of body mass; and the multiplier (i.e.

a, b and c) that often refers to a parameter independent of body mass. Eq. (1a) states a constraint that the somatic and gonadic masses must be the total mass. Equations (1b)–(1c) describe the energy allocation mechanism of individuals. Equation (1b) consists of three components:  expresses the acquisition of energy resources;

expresses the acquisition of energy resources;  describes energy expenditure towards non-body-growth components, including maintenance and indirect reproduction costs. The term

describes energy expenditure towards non-body-growth components, including maintenance and indirect reproduction costs. The term  then represents the direct reproduction energy expenditure that is specified in Eq. (1c). The model here assumes that investments in gonadic growth (1c) begin immediately after birth. Some allometric models often assume a two-stage response where energy is allocated to gonadic growth after a certain age of maturity22,23,25. Such energetic allocation response is advantageous for species that take longer to reach sexual maturity (e.g. fish and mammals). There is also a direct link to other growth models; for example, von Bertalanffy model assumes specific constants for the exponent as

then represents the direct reproduction energy expenditure that is specified in Eq. (1c). The model here assumes that investments in gonadic growth (1c) begin immediately after birth. Some allometric models often assume a two-stage response where energy is allocated to gonadic growth after a certain age of maturity22,23,25. Such energetic allocation response is advantageous for species that take longer to reach sexual maturity (e.g. fish and mammals). There is also a direct link to other growth models; for example, von Bertalanffy model assumes specific constants for the exponent as  but does not explicitly accommodate the gonadic energy allocation

but does not explicitly accommodate the gonadic energy allocation  (see Ricklefs (2003)36 for mathematical links to other models). The key distinction here is the model exponents that are not predefined but estimated from data, which makes the present model hybrid contrasting to those existing models.

(see Ricklefs (2003)36 for mathematical links to other models). The key distinction here is the model exponents that are not predefined but estimated from data, which makes the present model hybrid contrasting to those existing models.

Given the sum-constraint (1a), we can write the instantaneous relative fecundity investment,  say, taking the ratio of Eqs. (1c) and (1a) as

say, taking the ratio of Eqs. (1c) and (1a) as

|

2 |

where  , the rate at which energy is allocated to non-body-growth components. The rate

, the rate at which energy is allocated to non-body-growth components. The rate  can take, from the definition, values between

can take, from the definition, values between  . Given this, we can re-write Eq. (2) as

. Given this, we can re-write Eq. (2) as

|

3 |

and substitute it to Eq. (1b) as

|

1b’ |

The analytical solution of Equation  cannot be obtained in a closed form. Thus, numerical means is required to solve the equation or estimate the model parameters.

cannot be obtained in a closed form. Thus, numerical means is required to solve the equation or estimate the model parameters.

Body length model

Once the growth model is established in terms of body mass, we can scale it into a unit of body length. Somatic mass  and body length

and body length  are scaled using a power transformation,

are scaled using a power transformation,

|

4 |

where h and k are respectively a constant. Since  , the conversion emerges to a simple re-parametrisation of Equation

, the conversion emerges to a simple re-parametrisation of Equation  as

as

|

5 |

where

|

The above re-parametrisation inherits the implication from the original parameters of the body mass model (1b). The parameters z and  only depend on the energy acquisition through the parameters a and

only depend on the energy acquisition through the parameters a and  , whereas the time-varying parameter

, whereas the time-varying parameter  relies on both the energy acquisition and the non-growth (i.e. maintenance and indirect reproduction) costs through the parameters c and

relies on both the energy acquisition and the non-growth (i.e. maintenance and indirect reproduction) costs through the parameters c and  , apart from the constant h used for the body mass–length transformation (Eq. 4). If it is assumed that

, apart from the constant h used for the body mass–length transformation (Eq. 4). If it is assumed that  , i.e. the energy allocated to the non-growth components is proportional to the energy intake as

, i.e. the energy allocated to the non-growth components is proportional to the energy intake as  , then

, then  becomes constant over time as

becomes constant over time as  .

.

Lifetime fecundity model

Equation (1c) suggests that the cumulative energy allocated to direct reproduction up to age  can be quantified by its integration. From Eqs. (3) and (4), this quantity is given as

can be quantified by its integration. From Eqs. (3) and (4), this quantity is given as

|

6 |

Total energy allocated to reproduction is difficult to quantify directly from standard experiments. Here we use the cumulative number of neonates produced by each individual up to age  , say

, say  , to capture the energy allocated to direct reproduction. Accordingly, we expect the cumulative number of neonates produced across the lifetime to be proportional to the cumulative energy,

, to capture the energy allocated to direct reproduction. Accordingly, we expect the cumulative number of neonates produced across the lifetime to be proportional to the cumulative energy,  , assuming that the energy required per neonate is relatively constant. In Daphnia, the primary energy source for reproduction is provided by lipids obtained through food37. Although the amount of triacylglycerol transferred into each egg depends on age and feeding success, within the individual, the energy cost of producing a neonate is expected to be similar38.

, assuming that the energy required per neonate is relatively constant. In Daphnia, the primary energy source for reproduction is provided by lipids obtained through food37. Although the amount of triacylglycerol transferred into each egg depends on age and feeding success, within the individual, the energy cost of producing a neonate is expected to be similar38.

The model assumptions for the present experiment

The growth model sensu body length is provided in a general form (Eq. 5), which can be re-parametrised to reflect the experimental conditions used here. This facilitates the interpretation of what each model parameter represents in energy allocation mechanisms. We set the following three assumptions:

the potential energy intake from food is identical for all individuals since all individuals were fed above ad libitum in a controlled feeding environment ensuring that nutritional adequacy. Thus the parameters z and

of Eq. (5) will become the same over the different temperature scenarios. There is a similar convergence in the parameters a and

of Eq. (5) will become the same over the different temperature scenarios. There is a similar convergence in the parameters a and  of Equation

of Equation  in the body mass context;

in the body mass context;the amount of energy spent on maintenance is proportional to the energy intake18,37. The parameter

of Equation (5) is thus constant over a lifetime but can differ amongst the temperature scenarios; and

of Equation (5) is thus constant over a lifetime but can differ amongst the temperature scenarios; andthe amount of energy allocated to direct reproduction differs amongst the different temperature scenarios35. Accordingly, the time-varying parameter

of Eq. (5) will depend upon time and temperature scenarios.

of Eq. (5) will depend upon time and temperature scenarios.

Under these assumptions, Eq. (5) can be re-parametrised viz.

|

7 |

with two constant parameters, q and  and a time-varying parameter,

and a time-varying parameter,  , that are

, that are

|

7a |

|

7b |

|

7c |

To specify Eq. (7), these parameters,  and

and  (see Table 1 for their interpretation), need to be estimated from body length data. It is worthwhile mentioning that our model advancement allows, as will be discussed in the following section, estimating the time-varying parameter

(see Table 1 for their interpretation), need to be estimated from body length data. It is worthwhile mentioning that our model advancement allows, as will be discussed in the following section, estimating the time-varying parameter  without body (

without body ( ) and gonadic (

) and gonadic ( ) mass data, both of which are initially required as the model states.

) mass data, both of which are initially required as the model states.

Table 1.

The key model parameters in Eq. 7.

The assumptions and the re-parametrisation above will benefit model interpretation. Differences in energy allocation patterns caused by different temperature scenarios can now be revealed via the parameters q and  . Since the parameters a and

. Since the parameters a and  are related to anabolism and are assumed to be the same across the temperature scenarios (A1), the parameter q tends to be small when energy costs become greater because of a larger value of c; note that

are related to anabolism and are assumed to be the same across the temperature scenarios (A1), the parameter q tends to be small when energy costs become greater because of a larger value of c; note that  (A2). In other words, individuals are predicted to grow slowly when values of q are small because of less energy for growth. The extent to which energy is allocated to direct reproduction changes over time across the different temperature scenarios is given by the time-varying parameter

(A2). In other words, individuals are predicted to grow slowly when values of q are small because of less energy for growth. The extent to which energy is allocated to direct reproduction changes over time across the different temperature scenarios is given by the time-varying parameter  (A3). However, as Eq. (7) cannot be solved analytically, the parameter estimation relies on numerical means.

(A3). However, as Eq. (7) cannot be solved analytically, the parameter estimation relies on numerical means.

Once the model parameters,  , and

, and  in Eq. (7) are estimated from body length data, the total energy allocated to direct reproduction up to age

in Eq. (7) are estimated from body length data, the total energy allocated to direct reproduction up to age  should mirror the pattern of the cumulative number of neonates up to age

should mirror the pattern of the cumulative number of neonates up to age  , say

, say  . This allows us to test whether the estimated model represents the actual energy allocation mechanism well by evaluating the shape of the curve against the number of neonates produced by each individual over a lifetime. The expected number of notates up to age

. This allows us to test whether the estimated model represents the actual energy allocation mechanism well by evaluating the shape of the curve against the number of neonates produced by each individual over a lifetime. The expected number of notates up to age  can be proportional to the cumulative energy,

can be proportional to the cumulative energy,  , as

, as

|

8 |

Parameter estimation

The parameter estimation procedure employed the gradient matching method to minimise the squared errors in the gradient (derivative) without solving the differential equation25,39–41. The overview of the parameter estimation procedure is provided below. Note that the hat-sign (  ) is hereafter used for variables and parameters throughout the manuscript to indicate estimated variable or parameter values.

) is hereafter used for variables and parameters throughout the manuscript to indicate estimated variable or parameter values.

Consider observed body length trajectory data  for the i-th individual. Time t takes discrete time points,

for the i-th individual. Time t takes discrete time points,  , and the endpoint

, and the endpoint  differs amongst individuals because their lifetime varies. The observed trajectories are noisy realisations from the process

differs amongst individuals because their lifetime varies. The observed trajectories are noisy realisations from the process  governed by the differential Eq. (7). The observations can then be written as

governed by the differential Eq. (7). The observations can then be written as

|

9 |

where  is a noise term with mean of zero,

is a noise term with mean of zero,  for

for  . Although the analytical form of the processes (Eq. 7) are unknown, Eq. (9) suggests that the form can be delineated from the data, taking their expectation, i.e.

. Although the analytical form of the processes (Eq. 7) are unknown, Eq. (9) suggests that the form can be delineated from the data, taking their expectation, i.e.

. The calculation of the expectation here is carried out via the locally weighted regression (loess)42,43 as described in Shimadzu & Wang (2021)25 with the default smoothing argument.

. The calculation of the expectation here is carried out via the locally weighted regression (loess)42,43 as described in Shimadzu & Wang (2021)25 with the default smoothing argument.

The stochastic version of the differential Eq. (7) can be described in a conventional way viz.

|

10 |

The standard Brownian motion  , with its mean

, with its mean  , describes stochastic divergence from the model due to the stochastic nature amongst time and individuals. This discrepancy is going to be minimised when estimating the parameters, namely q,

, describes stochastic divergence from the model due to the stochastic nature amongst time and individuals. This discrepancy is going to be minimised when estimating the parameters, namely q,  and

and  as

as

|

The integrand above is a squared term of the stochastic divergence specified in Eq. (10). To estimate the approximate value of the above integral, we use the trapezium method with appropriate intervals;  is a weight for the numerical integration, and the present study chooses

is a weight for the numerical integration, and the present study chooses  (day). It is worth noting that the minimisation procedure here is the same as the weighted least squared method for linear regressions, profiling upon the parameter

(day). It is worth noting that the minimisation procedure here is the same as the weighted least squared method for linear regressions, profiling upon the parameter  —profile least squares—which can easily be implemented in a standard linear regression framework.

—profile least squares—which can easily be implemented in a standard linear regression framework.

Results

Body length growth

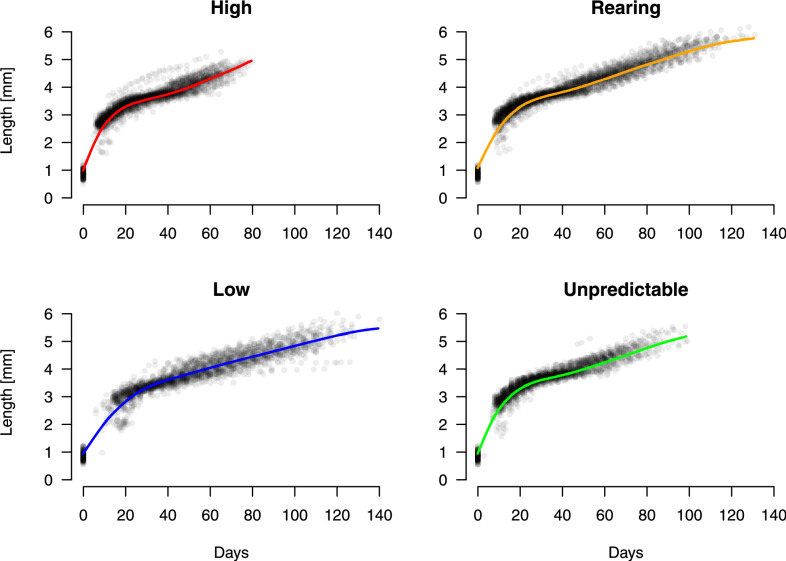

The model revealed a significant effect of temperature through the estimated parameter  (Table 2 and Fig. 1), equivalent to the energy proportion used for somatic growth. However, there appears to be a slight difference amongst the estimated growth curves, except for that of the low-temperature treatment (Fig. 2, the top panel). The difference in the parameter

(Table 2 and Fig. 1), equivalent to the energy proportion used for somatic growth. However, there appears to be a slight difference amongst the estimated growth curves, except for that of the low-temperature treatment (Fig. 2, the top panel). The difference in the parameter  between the unpredictable- and high-temperature scenarios is relatively moderate. The growth pattern in the individuals exposed to unpredictable temperature variations is parallel to the constant high temperature, with overlapping

between the unpredictable- and high-temperature scenarios is relatively moderate. The growth pattern in the individuals exposed to unpredictable temperature variations is parallel to the constant high temperature, with overlapping  confidence intervals. Each panel in Fig. 3 illustrates estimated growth curves for the data observed for each temperature treatment. Overall, the curves fit the observations well, and even captured a slight deviation around day 40.

confidence intervals. Each panel in Fig. 3 illustrates estimated growth curves for the data observed for each temperature treatment. Overall, the curves fit the observations well, and even captured a slight deviation around day 40.

Table 2.

The parameter estimates and summary statistics with their  confidence intervals.

confidence intervals.

| Treatments |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Eq. 7a) | (Eq. 7b) | |||

| Constant Low | 0.118 | 239 | 81 | |

(15 C) C) |

(0.110, 0.126) | (235, 243) | (75, 87) | |

| Constant Rearing | 0.169 | 0.179 | 236 | 72 |

(20 C) C) |

(0.159, 0.180) | (0.163, 0.196) | (229, 242) | (67, 77) |

| Constant High | 0.209 | 181 | 48 | |

(25 C) C) |

(0.198, 0.220) | (176, 185) | (45, 52) | |

| Unpredictable Variation | 0.196 | 194 | 52 | |

(15–25 C) C) |

(0.187, 0.206) | (189, 199) | (48, 56) |

: The estimate is assumed to be the same over the different treatments

: The estimate is assumed to be the same over the different treatments

Fig. 1.

The estimated parameters  with their

with their  confidence intervals against temperature scenarios.

confidence intervals against temperature scenarios.

Fig. 2.

The body length curve and the estimated fecundity changes. Top: the calculated body length growth curve and its  confidence envelope for each temperature treatment. Each curve is a numerical solution of model (7), given estimated parameters,

confidence envelope for each temperature treatment. Each curve is a numerical solution of model (7), given estimated parameters,  and

and  . The length of the trajectories differ as the longevity of D. magna varies; Bottom: the estimated fecundity investments over time, time-varying parameter

. The length of the trajectories differ as the longevity of D. magna varies; Bottom: the estimated fecundity investments over time, time-varying parameter  .

.

Fig. 3.

The scatter plots and the estimated growth curves.

Furthermore, the estimated parameter  suggests that D. magna in lower temperatures reduce the energy expenditure for growth, demonstrating an exact ascending order along with the low- to high-temperature scenarios (Table 2). Figure 1 highlights a clear linear pattern between the parameter

suggests that D. magna in lower temperatures reduce the energy expenditure for growth, demonstrating an exact ascending order along with the low- to high-temperature scenarios (Table 2). Figure 1 highlights a clear linear pattern between the parameter  and temperature, except for the unpredictable temperature treatment.

and temperature, except for the unpredictable temperature treatment.

The estimated power coefficient  is assumed to be shared over the different temperature scenarios (A1). The parameter

is assumed to be shared over the different temperature scenarios (A1). The parameter  can easily be converted to the parameter

can easily be converted to the parameter  in the body mass model

in the body mass model  ; it is given as

; it is given as  , which is close to a value widely reported from other studies13, when the isometric growth (i.e. the cubic weight–length transformation,

, which is close to a value widely reported from other studies13, when the isometric growth (i.e. the cubic weight–length transformation,  ) is assumed.

) is assumed.

Energy allocation between growth and direct reproduction

The estimated time-varying parameters  highlight variations in relative energy allocation to reproduction across the temperature scenarios (Fig. 2, bottom panel); note that

highlight variations in relative energy allocation to reproduction across the temperature scenarios (Fig. 2, bottom panel); note that  , implying no energy allocation to reproduction at birth,

, implying no energy allocation to reproduction at birth,  . The discrepancy of these estimated curves appears to be greater for the early life stage (0–40 days) and diminishes in the later stage, as these

. The discrepancy of these estimated curves appears to be greater for the early life stage (0–40 days) and diminishes in the later stage, as these  curves approach an asymptote. The constant high-temperature induces rapid gonadic growth with increased relative energy allocation to reproduction within a shorter interval (0–20 days). This response mirrors those in the unpredictable temperature treatment. On the other hand, the individuals allocated to the constant low-temperature treatment take longer (0–35 days) to reach the asymptote. The extent of increase in

curves approach an asymptote. The constant high-temperature induces rapid gonadic growth with increased relative energy allocation to reproduction within a shorter interval (0–20 days). This response mirrors those in the unpredictable temperature treatment. On the other hand, the individuals allocated to the constant low-temperature treatment take longer (0–35 days) to reach the asymptote. The extent of increase in  during early life stages becomes faster as temperature increases.

during early life stages becomes faster as temperature increases.

Direct reproduction

With the estimated model parameters, namely  , and

, and  , Eq. (8) can be matched with the cumulative number of neonates produced by each temperature treatment. Figure 4 illustrates these matched curves for ease of comparison. The average lifetime

, Eq. (8) can be matched with the cumulative number of neonates produced by each temperature treatment. Figure 4 illustrates these matched curves for ease of comparison. The average lifetime  of the temperature scenarios results in descending order as temperature increases (Table 2). Interestingly, the parameter q and the average lifetime

of the temperature scenarios results in descending order as temperature increases (Table 2). Interestingly, the parameter q and the average lifetime  are negatively correlated (Table 2). Furthermore, the cumulative number of neonates up to the average lifetime,

are negatively correlated (Table 2). Furthermore, the cumulative number of neonates up to the average lifetime,  , is greater for those allocated to the constant low-temperature treatment than the constant high-temperature treatment (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

, is greater for those allocated to the constant low-temperature treatment than the constant high-temperature treatment (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Fig. 4.

The calculated quantity equivalent to the number of neonates produced for the average lifetime. Each dashed line illustrates the average lifetime (days)  : 81 (Constant Low), 72 (Constant Rearing), 48 (Constant High) and 52 (Unpredictable Variation). The corresponding number of neonates

: 81 (Constant Low), 72 (Constant Rearing), 48 (Constant High) and 52 (Unpredictable Variation). The corresponding number of neonates  : 239 (Constant Low), 236 (Constant Rearing), 181 (Constant High) and 194 (Unpredictable Variation).

: 239 (Constant Low), 236 (Constant Rearing), 181 (Constant High) and 194 (Unpredictable Variation).

The illustrated curves for the cumulative number of neonates in Fig. 5 demonstrate a remarkable agreement with actual observations, indicating that the model provides accurate representation of experiment data. Note that all the model parameters are estimated solely based on the body length data.

Fig. 5.

The scatter plots show the number of neonates produced by individuals over the lifetime. The superposed solid line represents the theoretical number of neonates up to days t. The dashed line illustrates the average lifetime  and the corresponding number of neonates

and the corresponding number of neonates  .

.

Discussion

We have developed a novel allometric scaling growth model that enables predicting patterns in energy allocation between growth and reproduction across different thermal conditions. With body length data, rather than body mass, this new model broadens its applicability across a range of organisms. As a unique feature of our model, its time-varying parameter,  , projects instantaneous relative fecundity investment. This parameter delineates how temperature influences the allocation of energy to direct reproduction over a lifetime, capturing age-dependent transitions within unobservable energy distribution mechanisms, and uncovers the interplay between growth and reproduction through a single equation (Eq. 7). The underlying model assumptions (A1–A3) have also been thoroughly evaluated against lifetime neonate data (Fig. 5), thereby ensuring robustness of the model. This novel framework offers valuable insights into the crucial role of energy allocation mechanisms in shaping life-history traits of organisms under realistically varying temperature scenarios, thus revealing the complexity between life-history traits and energy allocation patterns.

, projects instantaneous relative fecundity investment. This parameter delineates how temperature influences the allocation of energy to direct reproduction over a lifetime, capturing age-dependent transitions within unobservable energy distribution mechanisms, and uncovers the interplay between growth and reproduction through a single equation (Eq. 7). The underlying model assumptions (A1–A3) have also been thoroughly evaluated against lifetime neonate data (Fig. 5), thereby ensuring robustness of the model. This novel framework offers valuable insights into the crucial role of energy allocation mechanisms in shaping life-history traits of organisms under realistically varying temperature scenarios, thus revealing the complexity between life-history traits and energy allocation patterns.

The interplay between growth and reproduction has been well-documented under constant temperatures1. High mean temperatures are generally associated with increased growth and reproduction rates3,44. This pattern is effectively described by our allometric model. Individuals exposed to consistently high temperatures exhibited faster growth with high  and produced more neonates early in life as

and produced more neonates early in life as  illustrated (Table 2, Figure 2). This result provides robustness to our model and aligns with the established expectations of energy allocation between growth and reproduction under consistently higher temperature45. Our model, however, shows that when exposed to low-temperature there is a delay in investment in fecundity (

illustrated (Table 2, Figure 2). This result provides robustness to our model and aligns with the established expectations of energy allocation between growth and reproduction under consistently higher temperature45. Our model, however, shows that when exposed to low-temperature there is a delay in investment in fecundity ( increased slowly), at the expenses of more energy being allocated to maintenance (Table 2, Fig. 2). This pattern is consistent with the expectation that consistent exposure to below optimal temperatures, energy is prioritised to maintenance at the expenses of reproduction46. We did notice a cost of life expectancy in both the unpredictable and constant high temperature scenarios. Under these thermal conditions, individuals produced more neonates during early to mid-life stages but attained shorter lifespan, which resulted in a reduced overall fitness. Greater metabolic demands caused by high temperatures are expected favour a strategy of strong early investment in fecundity at the expenses of reduced lifespan47,48. Our results, indicate that D. magna adopts a life history strategy analogous to a “live fast, die young” pace-of-life syndrome when exposed to above optimal thermal conditions, a pattern observed in previous studies and hypothesised to evolve in response to such physiological and thermal stressors49.

increased slowly), at the expenses of more energy being allocated to maintenance (Table 2, Fig. 2). This pattern is consistent with the expectation that consistent exposure to below optimal temperatures, energy is prioritised to maintenance at the expenses of reproduction46. We did notice a cost of life expectancy in both the unpredictable and constant high temperature scenarios. Under these thermal conditions, individuals produced more neonates during early to mid-life stages but attained shorter lifespan, which resulted in a reduced overall fitness. Greater metabolic demands caused by high temperatures are expected favour a strategy of strong early investment in fecundity at the expenses of reduced lifespan47,48. Our results, indicate that D. magna adopts a life history strategy analogous to a “live fast, die young” pace-of-life syndrome when exposed to above optimal thermal conditions, a pattern observed in previous studies and hypothesised to evolve in response to such physiological and thermal stressors49.

As increased temperature variability intensifies globally50–52, organisms face not only warmer averages but also its unpredictability with which becomes a greater challenge to cope53. A recent meta-analysis showed limited effect of fluctuating temperatures on biological responses compared to constant temperatures9. Our results provide mixed support for this prediction. While individuals exposed to unpredictable variations in temperature produced less neonates at their average lifetime relative to both low and rearing conditions, these effects were not distinct from those observed under the constant high-temperature scenario (Figure 5). Indeed, their growth, reproduction and mortality responses also resemble those of both unpredictable and high-temperature scenarios. This result adds to the discussion regarding whether unpredictable temperature disproportionately impacts fitness cost38,53 or not54. Several explanations could account for our result. First, individuals under the constant high-temperature scenario were likely to be exposed to their maximum reproductive thermal tolerance and stress55–57, thereby always being exposed to thermal stress. On the other hand, individuals exposed to unpredictable temperatures are likely to have encountered periodic optimal thermal conditions. This fluctuation between upper-limit and optimal temperatures may have facilitated a thermal tolerance, thereby reducing some fitness costs associated with unpredictability in temperature58. Another possibility is that elevated temperatures impair food-to-energy assimilation efficiency59. Our findings confirm the complexity of individual sensitivity responses to thermal variability, which warrants further investigation.

There are some limitations in our study. First, we used the number of neonates at emergence as a proxy for direct reproductive investment. While number and offspring size are considered to be reasonable indicators of fitness and reproductive investment38,60,61, indirect reproductive investment such as potential parental care costs can be a crucial component in terms of reproductive investment as a whole62, though Daphnia provide no parental care. A separate investigation on this energetic component would be worthy as a venue for future research. Further, we note that extrapolations of our model across very-distant species, or extreme size ranges need caution. Despite these limitations, our model provides a clear and robust pattern of the dynamics between energy allocation and life-history traits under ecologically relevant conditions in a keystone species. The allometric nature of our model can be applied to different species to predict their biological rates and traits.

Shifts in fitness-related traits (e.g. fecundity, mortality and growth) in response to environmental disruptions—such as increased unpredictability in temperature—bear direct consequences for population dynamics, thus shaping ecosystem stability. Responses in keystone species (such as Daphnia) to variability in environmental conditions provide insights into species’ climatic tipping points63, which is a critical metric for forecasting the resistance and resilience of the impacted ecosystem64. Keystone species play a pivotal role in regulating the balance between primary producers and consumers biomass. For instance, increased Daphnia abundance is followed by a decrease in algal blooms, which resulted in improved water quality and increased fish biomass65. Disruptions to the life cycle of Daphnia, therefore, hold major consequences for the whole ecosystem66. The ecological importance of keystone species raises a crucial aspect, how these species respond to environmental unpredictability, which hinders the ability of species to predict future conditions67–69. This underlines an urgent need for an improved understanding the extent to which environmental variability shapes life-history traits, leading it into changes at an individual, population, community and ecosystem as a whole. Translating life-history trait responses into energetic responses is, as our model has demonstrated, a promising approach and can address such a gap as a critical first step to a better understanding of processes in species adaptation and resilience, offering great potential for investigating environmental impacts on organisms under emerging changes in climate conditions.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

MB was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from FCT (SFRH/BPD/82259/2011) and had financial support from CESAM (UIDP/50017/2020; UIDB/50017/2020). HS was partially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Grant Number: JP19K21569; JP21H03402, 25K09165).

Author contributions

MB and HS conceived the ideas and designed methodology; MB collected the data; HS analysed the data; HS led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the GitHub, https://github.com/hshimadzu/DaphniaGrowth

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-15593-6.

References

- 1.Angilletta, M. J., Steury, T. D. & Sears, M. W. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: Fitting pieces of a life-history puzzle. Integrative and Comparative Biology44, 498–509. 10.1093/icb/44.6.498 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cossins, A. R. & Bowler, K. Temperature Biology of Animals (Springer, Netherlands, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson, D. Temperature and Organism Size—Biological Law for Ectotherms?, vol. 25 of Advances in Ecological Research, 1–58 (Academic Press, 1994).

- 4.Stearns, S. C. The Evolution of Life Histories (Oxford University Press, Oxford New York, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Field, C. B. Changes in ecologically critical terrestrial climate conditions. Science341, 486–492. 10.1126/science.1237123 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visser, M. E. & Both, C. Shifts in phenology due to global climate change: the need for a yardstick. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences272, 2561–2569. 10.1098/rspb.2005.3356 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franch-Gras, L., García-Roger, E. M., Serra, M. & Carmona, M. J. Adaptation in response to environmental unpredictability. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences284, 20170427. 10.1098/rspb.2017.0427 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slein, M. A., Bernhardt, J. R., O’Connor, M. I. & Fey, S. B. Effects of thermal fluctuations on biological processes: a meta-analysis of experiments manipulating thermal variability. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences290, 10.1098/rspb.2022.2225 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Stocker, C. et al. The effect of temperature variability on biological responses of ectothermic animals—a meta-analysis. Ecology Letters27, 10.1111/ele.14511 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Colinet, H., Sinclair, B. J., Vernon, P. & Renault, D. Insects in fluctuating thermal environments. Annual Review of Entomology60, 123–140. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-021017 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, J. H., Gillooly, J. F., Allen, A. P., Savage, V. M. & West, G. B. Toward a metabolic theory of Ecology. Ecology85, 1771–1789. 10.1890/03-9000 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pütter, A. Studien über physiologische Ähnlichkeit VI. Wachstumsähnlichkeiten. Pflüger’s Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere180, 298–340 (1920).

- 13.von Bertalanffy, L. Untersuchungen über die gesetzlichkeit des wachstums. Wilhelm Roux’ Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen131, 613–652 (1934). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Bertalanffy, L. Quantitative laws in metabolism and growth. The Quarterly Review of Biology32, 217–231 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kearney, M. R. What is the status of metabolic theory one century after Pütter invented the von Bertalanffy growth curve?. Biological Reviews96, 557–575. 10.1111/brv.12668 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kooijman, S. Energy budgets can explain body size relations. Journal of Theoretical Biology121, 269–282. 10.1016/s0022-5193(86)80107-2 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooijman, S. Quantitative aspects of metabolic organization: a discussion of concepts. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences356, 331–349. 10.1098/rstb.2000.0771 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Sousa, T., Domingos, T., Poggiale, J.-C. & Kooijman, S. A. L. M. Dynamic energy budget theory restores coherence in biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences365, 3413–3428. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0166 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goussen, B. et al. Bioenergetics modelling to analyse and predict the joint effects of multiple stressors: Meta-analysis and model corroboration. Science of The Total Environment749, 141509. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141509 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinke, K., Hülsmann, S. & Mooij, W. M. Energetic costs, underlying resource allocation patterns, and adaptive value of predator-induced life-history shifts. Oikos117, 273–285. 10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16099.x (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boukal, D. S., Dieckmann, U., Enberg, K., Heino, M. & Jørgensen, C. Life-history implications of the allometric scaling of growth. Journal of Theoretical Biology359, 199–207. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.05.022 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quince, C., Abrams, P. A., Shuter, B. J. & Lester, N. P. Biphasic growth in fish I: Theoretical foundations. Journal of Theoretical Biology254, 197–206. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.05.029 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quince, C., Shuter, B. J., Abrams, P. A. & Lester, N. P. Biphasic growth in fish II: Empirical assessment. Journal of Theoretical Biology254, 207–214. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.05.030 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mollet, F. M., Ernande, B., Brunel, T. & Rijnsdorp, A. D. Multiple growth-correlated life history traits estimated simultaneously in individuals. Oikos119, 10–26. 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17746.x (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimadzu, H. & Wang, H.-Y. Estimating allometric energy allocation between somatic and gonadic growth. Methods in Ecology and Evolution13, 407–418. 10.1111/2041-210x.13761 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baird, D. J., Barber, I., Bradley, M., Soares, A. M. & Calow, P. A comparative study of genotype sensitivity to acute toxic stress using clones of Daphnia magna straus. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety21, 257–265. 10.1016/0147-6513(91)90064-v (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.OECD. Test no. 211: Daphnia magna reproduction test. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 210.1787/9789264185203-en (2012).

- 28.ASTM. Standard practice for conducting acute toxicity tests with fishes, macroinvertebrates, and amphibians. In American Society for Testing and Materials, vol. 729, 406–430 (1980).

- 29.Im, H., Samanta, P., Na, J. & Jung, J. Time-dependent responses of oxidative stress, growth, and reproduction of daphnia magna under thermal stress. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology102, 817–821. 10.1007/s00128-019-02613-1 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giebelhausen, B. & Lampert, W. Temperature reaction norms of daphnia magna: the effect of food concentration. Freshwater Biology46, 281–289. 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2001.00630.x (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. Nih image to imagej: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods9, 671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gompertz, B. XXIV. on the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life contingencies. in a letter to Francis Baily, Esq. F.R.S. &c. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London115, 513–583. 10.1098/rstl.1825.0026 (1825). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lynch, M., Weider, L. J. & Lampert, W. Measurement of the carbon balance in daphnia1. Limnology and Oceanography31, 17–34. 10.4319/lo.1986.31.1.0017 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hallam, T. G., Lassiter, R. R., Li, J. & Suarez, L. A. Modelling individuals employing an integrated energy response: Application to daphnia. Ecology71, 938–954. 10.2307/1937364 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinke, K. & Vijverberg, J. A model approach to evaluate the effect of temperature and food concentration on individual life-history and population dynamics of daphnia. Ecological Modelling186, 326–344. 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.01.031 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricklefs, R. E. Is rate of ontogenetic growth constrained by resource supply or tissue growth potential? a comment on west et al.’s model. Functional Ecology17, 384–393. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00745.x (2003).

- 37.Tessier, A. J., Henry, L. L., Goulden, C. E. & Durand, M. W. Starvation in daphnia: Energy reserves and reproductive allocation. Limnology and Oceanography28, 667–676. 10.4319/lo.1983.28.4.0667 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbosa, M. et al. Maternal response to environmental unpredictability. Ecology and Evolution5, 4567–4577. 10.1002/ece3.1723 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varah, J. M. A spline least squares method for numerical parameter estimation in differential equations. SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing3, 24–46. 10.1137/0903003 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramsay, J. O. Principal differential analysis: Data reduction by differential operators. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological)58, 495–508. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02096.x (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsay, J. & Hooker, G. Dynamic Data Analysis (Springer, New York, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleveland, W. S. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association74, 829–836. 10.1080/01621459.1979.10481038 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cleveland, W. S. & Devlin, S. J. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. Journal of the American Statistical Association83, 596–610. 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478639 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angilletta Jr., M. J. Thermal Adaptation (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- 45.Forster, J., Hirst, A. G. & Atkinson, D. Warming-induced reductions in body size are greater in aquatic than terrestrial species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences109, 19310–19314. 10.1073/pnas.1210460109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trillmich, F. & Guenther, A. Shifts in energy allocation and reproduction in response to temperature in a small precocial mammal. BMC Zoology8. 10.1186/s40850-023-00185-6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Stearns, S. C. The evolutionary significance of phenotypic plasticity. BioScience39, 436–445. 10.2307/1311135 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 48.English, S. & Bonsall, M. B. Physiological dynamics, reproduction-maintenance allocations, and life history evolution. Ecology and Evolution9, 9312–9323. 10.1002/ece3.5477 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao, Z. et al. Body temperature is a more important modulator of lifespan than metabolic rate in two small mammals. Nature Metabolism4, 320–326. 10.1038/s42255-022-00545-5 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morice, C. P., Kennedy, J. J., Rayner, N. A. & Jones, P. D. Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: The HadCRUT4 data set. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres117. 10.1029/2011JD017187 (2012).

- 51.Mora, C. et al. The projected timing of climate departure from recent variability. Nature502, 183–187. 10.1038/nature12540 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karl, T. R. et al. Possible artifacts of data biases in the recent global surface warming hiatus. Science348, 1469–1472. 10.1126/science.aaa5632 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasseur, D. A. et al. Increased temperature variation poses a greater risk to species than climate warming. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences281, 20132612. 10.1098/rspb.2013.2612 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vafeiadou, A.-M. & Moens, T. Effects of temperature and interspecific competition on population fitness of free-living marine nematodes. Ecological Indicators120, 106958. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106958 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harley, C. D. G. et al. The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecology Letters9, 228–241. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00871.x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin, T. L. & Huey, R. B. Why, “suboptimal’’ is optimal: Jensen’s inequality and ectotherm thermal preferences. The American Naturalist171, E102–E118. 10.1086/527502 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nisbet, R. M., McCauley, E. & Johnson, L. R. Dynamic energy budget theory and population ecology: lessons from daphnia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences365, 3541–3552. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0167 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fischer, K. & Karl, I. Exploring plastic and genetic responses to temperature variation using copper butterflies. Climate Research43, 17–30. 10.3354/cr00892 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richman, S. The transformation of energy by daphnia pulex. Ecological Monographs28, 273–291. 10.2307/1942243 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hunt, J. & Hodgson, D. Evolutionary behavioral ecology, chap. What is fitness, and how do we measure it?, 46–70 (Oxford University Press, New York, 2010). Includes bibliographical references and index. - Description based on print version record.

- 61.Barbosa, M., Inocentes, N., Soares, A. M. & Oliveira, M. Synergy effects of fluoxetine and variability in temperature lead to proportionally greater fitness costs in daphnia: A multigenerational test. Aquatic Toxicology193, 268–275. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.10.017 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ginther, S. C., Cameron, H., White, C. R. & Marshall, D. J. Metabolic loads and the costs of metazoan reproduction. Science384, 763–767. 10.1126/science.adk6772 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lenton, T. M. et al. Tipping elements in the earth’s climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences105, 1786–1793. 10.1073/pnas.0705414105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Meerbeek, K., Jucker, T. & Svenning, J. Unifying the concepts of stability and resilience in ecology. Journal of Ecology109, 3114–3132. 10.1111/1365-2745.13651 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taipale, S. J., Kuoppamäki, K., Strandberg, U., Peltomaa, E. & Vuorio, K. Lake restoration influences nutritional quality of algae and consequently daphnia biomass. Hydrobiologia847, 4539–4557. 10.1007/s10750-020-04398-5 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Castro-Català, N. et al. Ecotoxicity of sediments in rivers: Invertebrate community, toxicity bioassays and the toxic unit approach as complementary assessment tools. Science of The Total Environment540, 297–306. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.06.071 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beaumont, H. J. E., Gallie, J., Kost, C., Ferguson, G. C. & Rainey, P. B. Experimental evolution of bet hedging. Nature462, 90–93. 10.1038/nature08504 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crean, A. J. & Marshall, D. J. Coping with environmental uncertainty: dynamic bet hedging as a maternal effect. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences364, 1087–1096. 10.1098/rstb.2008.0237 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Starrfelt, J. & Kokko, H. Bet-hedging-a triple trade-off between means, variances and correlations. Biological Reviews87, 742–755. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00225.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the GitHub, https://github.com/hshimadzu/DaphniaGrowth