Abstract

Background

People with kidney failure, unable to access kidney transplantation are disadvantaged in terms of their quality of life and overall survival. Despite this, regional, rural, and remote populations worldwide remain less likely to receive a kidney transplant and often experience unique difficulties throughout their transplant journey. This study aimed to explore the experiences of these kidney transplant recipients, including around current transplant processes to understand barriers to access for regional, rural, and remote populations.

Methods

Focus group discussions were conducted either in-person or online with kidney transplant recipients from regional, rural, and remote areas of northern Queensland. Transcripts were analysed thematically with emerging themes mapped against constructs of Levesque’s patient-centred healthcare access framework.

Results

Focus group participants (n = 30) included both deceased (90%) and living (10%) donor transplant recipients, with almost a third (30%) of which resided in rural or remote areas. Six themes were identified relating to access to kidney transplantation: facing hurdles to transplant assessment, insufficient communication and education, permeating psychosocial hazards, repercussions of distance, overwhelming financial strain, and troubling long-term adversities.

Conclusions

Kidney transplant recipients from regional, rural, and remote areas of northern Queensland described significant barriers throughout their transplantation journey. These relate primary to their geographical distance from specialty kidney transplant services and the subsequent logistic, financial, and psychosocial challenges that arise.

Clinical trial registration

This study was not a clinical trial.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12882-025-04412-9.

Keywords: Rural and remote health, Chronic kidney disease, Kidney failure, Kidney transplant, Indigenous health, Health equity

Background

Kidneys are the most commonly transplanted organ worldwide, with kidney transplantation (KT) considered the “gold standard” kidney replacement therapy (KRT) for patients due to superior quality of life and survival outcomes compared to dialysis [1, 2]. Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) offers the additional option of pre-emptive transplantation, without the need to commence dialysis, as well as improved graft and patient survival outcomes compared to deceased donor transplantation [3, 4]. There are ongoing implications for patients unable to obtain timely access to KT, with evidence indicating that prolonged time on dialysis prior to transplant is associated with poorer long-term outcomes and overall survival for recipients [5].

Globally, inequities exist in both availability and accessibility of KT [6], with regional, rural, and remote populations (defined in Australia as Modified Monash Model 2019 classifications MM2-MM7) [7] particularly disadvantaged, as they are far less likely to be wait-listed for or receive a transplant compared to their urban counterparts [8–10]. Many additional barriers to KT access have been identified for regional, rural, and remote populations, stemming primarily from their geographical distance from specialist medical services and transplantation facilities, requiring recurrent travel and prolonged time away from home [11]. Addressing access to healthcare is particularly complex, largely due to the interconnected system level and consumer specific characteristics that affect accessibility of services [12]. When designing, implementing, or evaluating new or existing health care services, the importance of consumer involvement is increasingly recognised as an essential step in developing health services that are relationship-focused [13].

However, existing studies exploring patients’ perspectives regarding access to specialist kidney health services for regional, rural, and remote populations worldwide examine the collective barriers and challenges across all KRT modalities [14–17], focus on particularly disadvantaged populations (such as Indigenous, Māori, Asian and African minorities) [18–23], or examine challenges pertaining to LDKT only [24, 25]. Works that address KT specifically in regional, rural, and remote populations explore the perceptions of patients who have not yet received a transplant [26], and therefore lack any lived experience of the peri- and post-transplant phases of the complete KT journey. Thus, there remains a paucity of data around the lived experiences of regional, rural, and remote KT recipients and how delivery of kidney health services could be improved or transformed to address existing inequities specific to KT access and care provision. The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives and lived experiences of KT recipients from regional, rural, and remote areas in northern Queensland, including around current pre-, peri-, and post-transplant processes to understand barriers to access and challenges across the entire KT journey. Using a patient-centred healthcare access framework [12], this study aimed to explore the interrelationships among identified barriers and challenges and their alignment with existing literature, providing novel insights to inform potential strategies for addressing inequities in transplant access and enhancing KT experiences and outcomes for wider regional, rural, and remote populations.

Methods

Study design

This study utilised a focus group methodology based on its demonstrated value in health care research in providing rich and meaningful data that would otherwise be less accessible without the interaction between participants [27]. Multisite ethical approval was granted by the Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/2023/QTHS/89342). This study was reported following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [28].

Participant selection and recruitment

Participants, sampled via a purposive non-probability method [27] were KT recipients recruited from regional, rural, and remote areas who had received their transplant within the last 5 years. Potential participants were identified through existing public nephrology services within northern Queensland (Cairns and Hinterland, Townsville, and Mackay Hospital and Health Services), with an invitation to participate sent to 120 eligible transplant recipients via post. Posters advertising the study were also provided to the relevant nephrology services to display in clinical areas and waiting rooms. Residency data were collected in order to define geographical remoteness of participants according to the Modified Monash Model (MMM) 2019 [7]. Written consent was obtained from all participants and reconfirmed verbally prior to commencement of each focus group discussion (FGD). Further information around recruitment can be found in Supplementary Material 1.

Data collection

A scoping review [11] informed the semi-structured focus group interview guide (Supplementary Material 2) which was reviewed and discussed with all investigators to confirm readability, content clarity, and validity in relation to the research objective. A total of four FGD were conducted over a 3-month period from May to July 2024, with three conducted in-person at various regional locations and one conducted virtually (for those unable to travel). FGD were moderated by the principal investigator (TKW) under the guidance of a co-investigator (BDG or NSR) with extensive qualitative research experience. Further information around data collection can be found in Supplementary Material 1.

Data analysis

Focus group transcripts were imported into NVivo (NVivo, Version 12, Lumivero, Denver United States) and analysed using a descriptive thematic method following the Braun and Clarke framework [29, 30]. Themes and subthemes were identified through both inductive and deductive coding, with initial deductive codes identified from the scoping review [11] and further developed during the iterative analysis process. The principal investigator (TKW) carried out the initial review of the data, inductively identifying recurrent or related ideas within the data to develop initial codes and themes. All investigators collaboratively reviewed and refined the coding scheme until a consensus was reached. TKW conducted line-by-line coding of the transcripts to develop conceptual links and overarching themes, with a second investigator (NSR) independently reviewing and coding sections of data to confirm interpretation [31, 32]. Final themes and subthemes were reviewed and agreed upon by all investigators. To further explore and understand the barriers to transplantation access that emerged from the data, a patient-centred healthcare access framework by Levesque et al. was used to assign relevant accessibility dimensions to each of the identified themes. The framework by Levesque et al. consists of five accessibility dimensions that integrate both supply- and demand-side determinants: approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness [12].

Results

A total of 30 transplant recipients attended focus groups including both deceased (90%) and living (10%) donor recipients. 10% of participants identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. The median age of participants was 59 years (IQR 51–62), and the median distance from participants’ residence to the nearest transplanting centre was 1,370 km (IQR 1348–1687). Demographic characteristics of participants in each focus group are included in Table 1, as previously described [33].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Kidney Transplant Recipient Participant Characteristics | FG1 (n = 8) |

FG2 (n = 8) |

FG3 (n = 7) |

FG4 (n = 7) |

Total (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of kidney transplant received | |||||

| Deceased donor transplant | 7 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 27 |

| Living donor transplant | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Years on dialysis prior to transplant | |||||

| 0–1 year | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| 1–3 years | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 17 |

| 3–5 years | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| > 5 years | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Age, y# |

54 (47–58) |

61 (59–61) |

53 (52–68) |

60 (46–63) |

59 (51–62) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| Female | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| Rurality of residence at time of transplant (MMM 2019) | |||||

| Regional Centre | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 21 |

| Medium Rural Town | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| Small Rural Town | - | - | 3 | - | 3 |

| Remote Community | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Very Remote Community | 1 | - | - | 2 | 3 |

| Distance from transplant centre, km#^ |

1688 (1668–1822) |

1354 (1351–1375) |

969 (969–995) |

1428 (1361–1695) |

1370 (1348–1687) |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | |||||

| Torres Strait Islander | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 2 | - | - | - | 2 |

| Non-Indigenous | 6 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 27 |

#Values are median (interquartile range)

^Shortest distance measured from participant’s residence to transplant centre via road

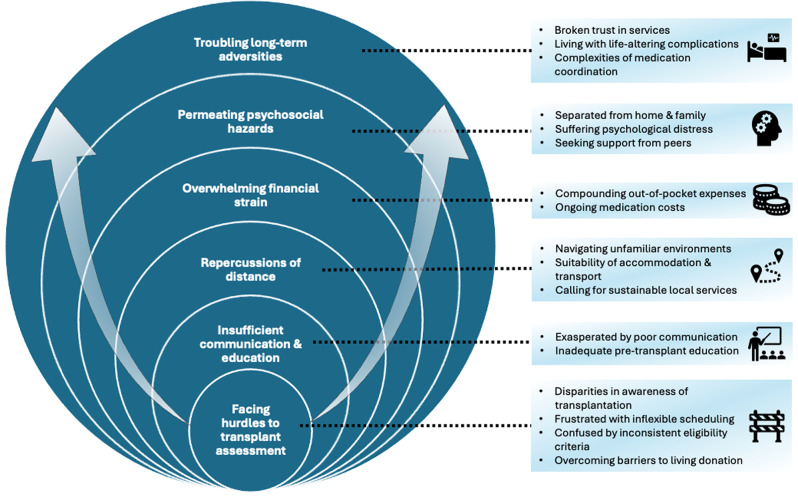

Six themes were identified related to participants’ access to transplantation: facing hurdles to transplant assessment, insufficient communication and education, permeating psychosocial hazards, repercussions of distance, overwhelming financial strain, and troubling long-term adversities. Table 2 provides illustrative participant quotations.

Table 2.

Identified themes, subthemes and illustrative participant quotations

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Facing hurdles to transplant assessment | |

| Disparities in awareness of transplantation |

“The discussion with Dr [nephrologist] was several years before I even went on dialysis, because we could see my kidney function gradually coming down”. (KTR; FG3) “They told me about 20 years ago when I was still at 70% kidney function that I would eventually have to have a kidney transplant, just with the nature of what I had”. (KTR; FG4) “I think it was two years in – during the dialysis when [transplant coordinator] actually talked to me about it and introduced me to all the facts”. (KTR; FG1) “It was only just prior to going on dialysis that I actually discussed with the doctor about transplanting. There wasn’t a lot of conversation about it… There wasn’t a lot of detail”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Frustrated with inflexible scheduling |

“It very much was do this test, then a month later, do another test, do another test”. (KTR; FG4) “It was just frustrating, you’d go to [regional area] today to do a test, then another day to do another one, and it just went on and on, to the point of just before I did get my transplant I was just about over it, because one of the first tests you had done, well it was out dated now, so you had to go and do it again, and you had only just finished doing the other tests. I just wish that they gave you all the tests at once and go to [regional area], even if you went there for a week and done the whole lot”. (KTR; FG4) “One test, I had to go down to [metropolitan city] for, I was literally in the hospital for five minutes, it does take a lot out of your day”. (KTR; FG1) “If I was coming down for a meeting here, I would ring [transplant coordinator] and say, “is there any tests I’ve got to do while I’m down here to make it easier?” Or if I’m on holiday here, “can I do some of my tests before I’m going back home?” So that was my frustration, not knowing when’s the next test, or even a checklist of what to expect about all the tests you’re going to have”. (KTR; FG1) |

| Confused by inconsistent eligibility criteria |

“I was told by all the doctors here, “you need to lose weight, need to lose weight” and it was really stressing me out. But when I went to see the doctors down there, the surgeon doctor, she come and saw me, she said, “you’re okay””. (KTR; FG1) “The surgeon said to me, “don’t put on any more weight” and that was fine and I didn’t. When you get down there, you’re sitting in the waiting room waiting to get your bloods done, and I was sitting in a room full of fatties. I was like, “how the hell did you get a [transplant]?”… Too many inconsistencies”. (KTR; FG1) “The inconsistency in the way that they would accept someone to operate on them was – there was no consistency”. (KTR; FG1) |

| Overcoming barriers to living donation |

“For me as an Indigenous person, that was never on the table… I spoke to the medical team, I was advised that as an Aboriginal person, it doesn’t happen. Live donors don’t happen… I thought, that’s a generalised stereotype”. (KTR; FG1) “The only real options were my two sisters… They weren’t married or had kids or anything like that, I just said “not going there, I’ll wait”… Just the thought of doing that to my sisters, it would have drastically reduced any chances of them having children and affected their whole life”. (KTR; FG4) “My brother just chickened out in the end, he got scared. Once they explained it to him, he actually got scared”. (KTR; FG2) “We looked at live donors for a short period of time but none of the possible live donors were matches. Then I went on the [deceased donor] waiting list”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Insufficient communication and education | |

| Exasperated by poor communication |

“I found out after the fact, “oh you’re off the list for this reason and that reason”, but I didn’t even know that I’d been off the list for a few months. I thought there could have been a lot more communication”. (KTR; FG4) “I think there was a lack of communication. I’d go to get a heart x-ray and then I’d come back to the [regional hospital] and have to do something else. I found the medical staff asking me what tests I’d had… But I thought, surely you should be able to access my records and tell me?”. (KTR; FG1) “When you’re having your tests they don’t tell you the outcome of it. When you’ve finished your blood test or your cardio or anything, they don’t tell you, “you’ve got to improve on this”… There’s no communication between me and the doctor or the nurse”. (KTR; FG1) |

| Inadequate pre-transplant education |

“I feel that in some of those seminars, a lot of it is skipped through… A lot of it is kind of oversold or portrayed as this really good thing… I think there needs to be someone in-house that does more education with you”. (KTR; FG1) “There was nobody to go and talk to about the transplant process and doing the education, because the renal nurses, they were having one-to-one with the dialysis patients… There was no time for going down and just sit down and have a yarn to them”. (KTR; FG1) “I had the webinars and couple of pamphlets and things, but other than that I really didn’t know what to expect”. (KTR; FG4) “I think they probably should give more education about the drugs beforehand, just so you’ve got an idea, because [post-transplant] it really hit me… I couldn’t handle that”. (KTR; FG1) “I didn’t get told anything about it really. They said, “you’re going on anti-rejection medications, you’ll be on quite a lot of meds after the transplant”. That was as far as it went until a few days after the transplant, sitting down and doing this quite intense… to go through and learn about all the different medications, and what they did, why you were taking them, side effects everything like that. Quite a lot to take in.” (KTR; FG4) |

| Permeating psychosocial hazards | |

| Separated from home and family |

“It’s a long wait, the six weeks, and you’re a long way from home and you miss home”. (KTR; FG3) “None of my close family or relations could get down to us at the time, they were busy with work and family and all of that. So that period was pretty lonely… There was no family support, which was for me, was massive”. (KTR; FG4) “I was really homesick, I didn’t even like the place. I just wanted to come home”. (KTR; FG4) “When we were down there, me and my wife, the person who was supposed to take our kids to school, they weren’t turning up, so the kids didn’t end up going to school”. (KTR; FG1) “Stuff is very short notice sometimes, which is hard when you do work, and I live on my own as well, so I’ve got pets and houses and stuff to look after to try to organise in short periods of time. I was completely unprepared to travel to [metropolitan city] for my transplant”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Suffering psychological distress |

“Once I actually got home it was quite challenging just accepting the new way of life and figuring out what was normal, what wasn’t and the anxiety that came with that”. (KTR; FG4) “Emotionally and psychologically I could not handle it, I’ll admit it. Someone would mention something and I’d just start bawling”. (KTR; FG3) “I cried a lot over that, someone had to die to give me life”. (KTR; FG2) “I was feeling upset, for getting somebody else’s organ to be placed inside of me. Taking the life from somebody and putting it inside of me”. (KTR; FG4) “The anxiety and the unknown about what’s going to happen after the transplant and how everything was going to change”. (KTR; FG4) |

| Seeking support from peers |

“I don’t see other recipients on [remote area]… I would rather come once a week or once a month, just to find out if there’s any problems, any issues with everybody or are they doing okay, or how I can support them”. (KTR; FG1) “It’s good to know you’re not alone I suppose, in the struggles that you do have”. (KTR; FG3) “I just knew a couple of people that had kidney transplants before, and I just picked their brain about what happens and how it all works… I thought it was good because you got first-hand experience of what happens”. (KTR; FG4) “I would have really appreciated someone that had been through it before to give me that guidance, it would have been useful”. (KTR; FG4) “We need that network… but we have no one to talk to. We think, is it only happening to us? It must be us. When really it’s not, it’s something that we all go through”. (KTR; FG2) |

| Repercussions of distance | |

| Navigating unfamiliar environments |

“You’ve got so much going through your head when all these events are happening. But someone calmly and collectively being able to do the paperwork side for you, being able to do certain steps to get you to where you need to go… I thought there was actually going to be some sort of a chaperone-type person”. (KTR; FG1) “When I arrived at [metropolitan hospital], I was by myself… I just couldn’t figure out where I had to be. I asked at an information desk, they ended up sending me all the way over to the dialysis unit outside the hospital… I was in a strange city, I didn’t know… I sat outside and started crying because I needed someone to just say “here, I will take you where you need to go”… I knew what I had to do when I got there, but I could not get to the place, and that was terribly scary”. (KTR; FG4) “I had another patient approach me, I went to the Aboriginal liaison officer and he just said to me, “you’ve got to go do this, this and that”. I thought, it’s not my responsibility, I’m just assisting another patient”. (KTR; FG1) |

| Suitability of accommodation and transport |

“Mum ran around with the Domestos and cleaned everything, even though they’re supposed to be clean, she’s going around there scrubbing everything. Things weren’t what you’d consider a healthy environment for someone who’s just been transplanted and extremely immunosuppressed”. (KTR; FG1) “There were huge capacity issues. There were people getting shuffled around left, right and centre”. (KTR; FG1) “For my transplant I had my grandson with me, a 22-year-old… It wasn’t suitable for us because he’s 22 and we were sleeping in the same room, and I wanted a room for myself as a grandmother because I’m 70. I couldn’t change in front of my grandson”. (KTR; FG4) “For people in [remote area], for them to prepare themselves, to travel the next day… I didn’t get my travel itinerary”. (KTR; FG4) “I was booked on the 6:30am flight and no one rang me… When I asked the question, everyone told me they didn’t know about it, including [nephrologist], including the manager, including all the other people that were in charge of me getting there safely and without the stress”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Calling for sustainable local services |

“The assessment in [metropolitan area], you go down, you’re there for one hour. When you think of people coming from remote areas, they’ve got to come to [regional area], overnight here first, so it takes a few more days”. (KTR; FG1) “If there could be a transplant clinic in [regional area], that would be amazing”. (KTR; FG4) “If they had something in [regional area] to take transplant patients back or other hospitals to look after them, that would have taken three weeks off my stay down there”. (KTR; FG2) “We’re sitting up here going, “where’s another doctor? Where’s someone to help that doctor?”… Where’s our professor with eight nephrologists walking around and the team of people rounding beside them?”. (KTR; FG3) “I understand us having a second one [transplant unit], but are we going to be able to staff it with the people that you get down in [metropolitan area]? That experience and knowledge?”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Overwhelming financial strain | |

| Compounding out-of-pocket expenses |

“You get out of hospital, and the first thing you’ve got to do is go to the Woolworths over the road, and you’ve got to start all over again, you’ve got to buy everything”. (KTR; FG1) “We had to organise our own accommodation and we were out thousands of dollars… It was a huge gap… I’d say four to five thousand we would have been out of pocket”. (KTR; FG4) “My wife runs a business too, of course she came down for a couple of weeks and that costs money”. (KTR; FG2) “I can’t even get in to see a skin specialist with bulk billing, or a bone density scan. I can’t afford to pay for it, not on the pension, no way in hell. Not when you’ve got to pay for registration and tyres to get there and the petrol”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Ongoing medication costs |

“I’m not on a concession card or anything, the first six weeks down in [metropolitan city] was extremely expensive… I started off on 49 tablets a day, which you were blowing through $500 every three days”. (KTR; FG3) “Costs me about $300 a month for the stuff… My work is really up and down, all over the place, so sometimes it is a big problem”. (KTR; FG3) “I’m still working and the burden of the medication cost for me, because there’s no reductions in pricing I pay full price, and it’s a massive challenge for me and a burden”. (KTR; FG4) “I wasn’t expecting the bill… I think mine was about $500 or something”. (KTR; FG1) |

| Troubling long-term adversities | |

| Broken trust in services |

“They don’t listen, they don’t do everything, they don’t do follow-ups like they should”. (KTR; FG3) “If not more nephrologists here I think we need a bigger team that can take care of the minor details that the doctors aren’t getting to”. (KTR; FG3) “I’ve only had one check-up from the [transplant unit] since I’ve been back. I don’t even think that they were particularly aware that I was sick for as long as what I was when I spoke to that doctor”. (KTR; FG3) “The response from the renal team here is nothing, I didn’t hear from anyone for four months and I was just like, when’s my next appointment? Should I go and do bloods?”. (KTR; FG3) |

| Living with life-altering complications |

“I have a lot of issues with viruses and diarrhoea and everything, I end up in hospital at least once every six months”. (KTR; FG2) “For years and years I kept getting urine infections, turns out they had left one of the stents in me from my first transplant”. (KTR; FG1) “The medications make me susceptible to sunlight and I’m prone to skin cancers, so I’ve had a mass of skin cancers burnt off… They still keep happening”. (KTR; FG3) “The kidney transplant that was left in had basically started to rot inside my body and that caused a great deal of problems that went on for about 18 months”. (KTR; FG4) |

| Complexities of medication coordination |

“I only go for the original brand, I don’t have substitute brands, and that’s why I can’t get tacrolimus through my chemist, they won’t do it”. (KTR; FG2) “I live near a small town [rural area] and their pharmacy is only open two days a week for two hours… which is immensely inconvenient… I only go to town once a fortnight, I can’t afford to be wasting fuel driving in for another box of medication”. (KTR; FG3) “I think it was just too many tablets for starters, you get mixed up”. (KTR; FG1) “I found it a bit difficult at first, because so many pills”. (KTR; FG3) “It was absolutely overwhelming. I have an app on my phone that connects to my watch… that keeps me on track so that I know I’m not going to miss any of the medication”. (KTR; FG4) “I think there needs to be conversations around some of those drugs and what they’re potentially going to do… there needs to be some sort of drug education”. (KTR; FG1) |

Abbreviations: KTR – Kidney transplant recipient, FG1 – Focus Group 1, FG2 – Focus Group 2, FG3 – Focus Group 3, FG4 – Focus Group 4

Facing hurdles to transplant assessment

Disparities in awareness of transplantation

Participants felt uninformed about transplant as a treatment option until well after commencing dialysis, with one person recalling “it was two years in – during the dialysis when [transplant coordinator] actually talked to me about it”. Others had considered transplant as a treatment option early on in their CKD journey, with one reporting initial discussions occurred “several years before I even went on dialysis”. These participants also self-reported glomerulonephritis or hereditary conditions as the primary cause of their kidney disease, which required early referral to a nephrologist for diagnosis and ongoing management.

Frustrated with inflexible scheduling

Participants expressed frustration with the lack of coordination and flexibility with scheduling of work-up testing, with one recalling, “it very much was do this test, then a month later, do another test”. The associated travel required was also inconvenient, with one individual recalling, “one test, I had to go down to [metropolitan city] for, I was literally in the hospital for five minutes”. Participants suggested the increased use of telehealth to reduce travel requirements, as well as “a checklist of what to expect about all the tests” provided at the time of referral, to improve planning and coordination.

Confused by inconsistent eligibility criteria

Participants felt discouraged and confused as they perceived there to be “too many inconsistencies” between the home nephrology service and the transplant unit for certain eligibility requirements. One recalled “I was told by all the doctors here, “you need to lose weight”… and it was really stressing me out. But when I went to see the doctors down there… she said, “you’re okay””. Others reported comparing their own weight to that of other recent recipients from the same transplant unit, feeling there was “inconsistency in the way that they would accept someone”.

Overcoming barriers to living donation

Numerous barriers and challenges to LDKT were experienced that prevented participants from pursuing this option. One person recalled “as an Indigenous person, that was never on the table… I was advised that as an Aboriginal person, it doesn’t happen” due to unacceptable risk of progression to kidney failure for the donor, however they felt this was a “generalised stereotype” based on population-specific risk only. Participants as potential recipients often declined the option of LDKT as they were worried about possible risks for the person donating their kidney, with one explaining “it would have drastically reduced any chances of them having children and affected their whole life”. Others had family members who willingly commenced the donor work-up process, but were either ruled out as “none of the possible live donors were matches”, or the family member “got scared” and changed their mind.

Insufficient communication and education

Exasperated by poor communication

Participants were frustrated with the “lack of communication” from clinicians, particularly around requirements and outcomes of work-up tests and investigations. One person reported “they don’t tell you the outcome of it… there’s no communication between me and the doctor”. Potential recipients were left unsure regarding their status on the waitlist due to poor communication, with someone recalling “I didn’t even know that I’d been off the list for a few months”.

Inadequate pre-transplant education

Participants’ experiences of pre-transplant education varied greatly, in both the content and format of delivery, with some attending online seminars hosted by the transplant unit and others receiving only sporadic local education through their home nephrology service. Many therefore felt underprepared for potential poor outcomes or complications post-transplant, with one reporting “in some of those seminars, a lot of it is skipped through”. Others felt isolated without opportunity for follow-up questions or discussion, reporting “there was nobody to go and talk to about the transplant process”. Participants were left scrambling to learn about their transplant medications and found it “quite a lot to take in” immediately after the transplant. Participants sought “more education about the drugs beforehand” including potential side effects, with one elaborating “it really hit me… I couldn’t handle that”.

Permeating psychosocial hazards

Separated from home and family

Participants expressed the loneliness they felt being away from home, family and country while receiving their transplant, explaining “it’s a long wait… you’re a long way from home and you miss home”. For those without a carer with them it “was pretty lonely… there was no family support, which was for me, was massive”. Participants felt stressed due to travel arrangements made with “very short notice”, particularly if they had “pets and houses and stuff to look after”. Someone recalled the distress they experienced because “the person who was supposed to take our kids to school, they weren’t turning up, so the kids didn’t end up going to school”.

Suffering psychological distress

Participants struggled to adjust after receiving their transplant, particularly “accepting the new way of life and figuring out what was normal” and dealing with “the anxiety that came with that”. They felt isolated without access to appropriate support or guidance from a health professional. Some experienced distress and guilt over “taking the life” (an organ) from somebody else, with one recalling “emotionally and psychologically I could not handle it… I’d just start bawling” and another recalling “I cried a lot over that, someone had to die to give me life”.

Seeking support from peers

The need for increased peer support was strongly expressed by participants, who felt it was important to hear “first-hand experience of what happens” and “to know you’re not alone” while navigating your own transplant journey. Some were disappointed to miss out on this opportunity, explaining “I don’t see other recipients on [remote area]” and “I would have really appreciated someone that had been through it before to give me that guidance”.

Repercussions of distance

Navigating unfamiliar environments

It was daunting for participants navigating unfamiliar cities and health care facilities alone to receive their transplant, especially when “you’ve got so much going through your head when all these events are happening”. They felt overwhelmed getting from the airport to the hospital and utilising public transport, and one person recalled how distressed they felt trying to find the correct area of the hospital, explaining “I sat outside and started crying because I needed someone to just say “here, I will take you where you need to go"”, highlighting the need for culturally appropriate “navigator” type roles.

Suitability of accommodation and transport

Participants were concerned regarding “huge capacity issues” with accessing health service supported accommodation options, describing them as not “what you’d consider a healthy environment for someone who’s just been transplanted and extremely immunosuppressed” due to mould and other hygiene concerns. Participants travelling long distances from remote areas were frustrated and stressed by the apparent disorganisation around transport, in some cases resulting in delays to transplant with one reporting “I didn’t get my travel itinerary” and another “I was booked on the 6:30am flight and no one rang me”.

Calling for sustainable local services

Participants’ desire for pre- and post-transplant services closer to home was recurrently highlighted, who felt “if there could be a transplant clinic in [regional area], that would be amazing”. They were frustrated with having to travel to metropolitan hospitals for transplant assessment given “you go down, you’re there for one hour”. However, participants were also wary of the sustainability of a regional KT service, asking “are we going to be able to staff it with the people that you get down in [metropolitan area]? That experience and knowledge?”.

Overwhelming financial strain

Compounding out-of-pocket expenses

Participants were strained by out-of-pocket expenses adding up to “thousands of dollars” relating to travel and accommodation, especially while also managing rent or mortgage payments, or loss of income. They were frustrated with insufficient subsidies from patient travel schemes, reporting “it was a huge gap… I’d say four to five thousand we would have been out of pocket”. Participants felt dejected by the ongoing medical expenses post-transplant, explaining “I can’t afford to pay for it, not on the pension, no way in hell”.

Ongoing medication costs

Transplant medications were described as “extremely expensive”, with some participants “blowing through $500 every three days” in the initial post-transplant period. Some were blindsided by these costs, with one explaining “I wasn’t expecting the bill”. The ongoing anxiety around covering medication costs long term was described as “a massive challenge for me and a burden”.

Troubling long-term adversities

Broken trust in services

Participants were concerned around both the capacity and capability of their local nephrology services to provide adequate post-transplant care, commenting “they don’t do follow-ups like they should”. Some felt they had been forgotten about, having no idea when they were next due to have blood tests or see the doctor, explaining “I didn’t hear from anyone for four months”. Participants felt that local nephrology services “need a bigger team that can take care of the minor details that the doctors aren’t getting to”.

Living with life altering complications

The troubling long-term complications of KT described by participants were largely unexpected, and they felt unsupported and ill-equipped to deal with them. Participants were burdened by “issues with viruses and diarrhoea” and “urine infections” affecting their quality of life, with one reporting “I end up in hospital at least once every six months”. Participants also struggled with medication adverse effects such as increased skin cancer risk, reporting “I’ve had a mass of skin cancers burnt off… They still keep happening”.

Complexities of medication coordination

Participants felt the various aspects of transplant medication management were “absolutely overwhelming”, particularly managing administration and dosette box packing as “it was just too many tablets for starters, you get mixed up”. They expressed the need for ongoing “drug education” and support to assist them with managing their medications post-transplant, as well as “conversations around some of those drugs and what they’re potentially going to do”. Participants were frustrated trying to source their preferred brands of immunosuppressant medications through community pharmacies that “won’t do it”, offering only generic brands, and they felt it was inconvenient to access hospital pharmacies, particularly when it’s “only open two days a week for two hours”.

To explore how these themes correspond to KT access and experiences for wider regional, rural, and remote populations, Table 3 presents the relevant Levesque et al. accessibility dimensions mapped against each subtheme, as well as similarly conducted studies that identify comparable themes.

Table 3.

Identified themes and subthemes with mapped Levesque et al. accessibility dimensions and similarly conducted studies identifying comparable themes

| Themes and Subthemes | Relevant Levesque et al. Accessibility Dimension/s | Reported in other Regional, Rural, or Remote Studies (Country of Origin) |

|---|---|---|

| Facing hurdles to transplant assessment | ||

| Disparities in awareness of transplantation |

Approachability / Ability to perceive Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [18] Anderson et al. (Aus) [36] Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Walker et al. (NZ) [22] Misra et al. (India) [37] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] |

| Frustrated with inflexible scheduling |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [18] Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Ghahramani et al. (US) [26] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] |

| Confused by inconsistent eligibility criteria |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Walker et al. (NZ) [22] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] |

| Overcoming barriers to living donation |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Ghahramani et al. (US) [26] |

| Insufficient communication and education | ||

| Exasperated by poor communication |

Approachability / Ability to perceive Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [18] Anderson et al. (Aus) [36] Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Walker et al. (NZ) [22] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] |

| Inadequate pre-transplant education |

Approachability / Ability to perceive Acceptability / Ability to seek Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [36] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Walker et al. (NZ) [22] Ghahramani et al. (US) [26] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] |

| Permeating psychosocial hazards | ||

| Separated from home and family |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [18] Anderson et al. (Aus) [36] Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] |

| Suffering psychological distress |

Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [18] Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] |

| Seeking support from peers |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] |

| Repercussions of distance | ||

| Navigating unfamiliar environments |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] |

| Suitability of accommodation and transport |

Acceptability / Ability to seek Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach |

Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] |

| Calling for sustainable local services |

Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Anderson et al. (Aus) [36] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Ghahramani et al. (US) [26] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] |

| Overwhelming financial strain | ||

| Compounding out-of-pocket expenses |

Affordability / Ability to pay Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Barnieh et al. (Aus) (LDKT) [24] McGrath et al. (Aus) (LDKT) [25] Kelly et al. (Aus) [21] Ghahramani et al. (US) [26] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [16] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [38] |

| Ongoing medication costs |

Affordability / Ability to pay Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Barnieh et al. (Aus) (LDKT) [24] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [38] |

| Troubling long-term adversities | ||

| Broken trust in services |

Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Devitt et al. (Aus) [20] Walker et al. (NZ) [22] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [14] Walker et al. (NZ) [17] |

| Living with life-altering complications | Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

Bennett et al. (Aus) [19] Scholes-Robertson et al. (Aus) [15] |

| Complexities of medication coordination |

Availability and accommodation / Ability to reach Appropriateness / Ability to engage |

|

Discussion

Transplant recipients in this study shared numerous challenges and difficulties faced throughout their journeys, stemming primarily from their geographical distance from specialty KT services and the consequent logistic, financial, and psychosocial barriers that arise. Access to transplantation for regional, rural, and remote recipients in this study was hindered by inflexible assessment and work-up processes as well as inadequate transplant education and communication from clinicians. Throughout the transplant process they struggled with significant financial and psychosocial stressors, and the logistics around traveling large distances and spending time away from home to receive their transplant. Participants experienced ongoing challenges in the post-transplant period also, including broken trust in their local nephrology services and issues with medication management. A visual representation of the relationship between identified themes is shown in Fig. 1. Each of the identified themes in this study could be related to multiple accessibility dimensions from the Levesque et al. framework (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Thematic schema showing relationship between identified themes

Whilst many of the challenges highlighted in this study appeared to affect participants equally, some had a greater impact with increasing remoteness. Participants from regional centres reported less difficulties accessing transplant work-up tests and pre-transplant education compared to those in rural and remote areas. Likewise, access to transplant medications was reportedly more difficult for those in rural and remote areas compared to participants from regional centres. These trends reflect the long recognised workforce shortages and limited access to healthcare services in rural and remote regions globally [34, 35]. A previous study comparing perceptions of KT between urban and rural CKD patients found similar differences between those cohorts, with rural participants receiving less information around transplant, less likely to be encouraged to pursue transplant, and citing distance from transplanting centre as a significant barrier [26]. Perceptions around LDKT also differed, with rural participants raising concerns about the well-being of the potential donor, and urban participants concerned about being indebted to the donor instead [26].

Overall, the barriers and challenges faced by regional, rural, and remote transplant recipients identified in this study are consistent with those identified in similar studies exploring perspectives of rural and remote KRT consumers across Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and India (Table 3). With regards to access to transplant, there are multiple Levesque et al. accessibility dimensions that align with each subtheme in this study (Table 3), supporting the theory that these are not independent constructs, but rather interrelated factors that will impact each other throughout the KT journey [12]. Difficulties completing transplant work-up and assessment [14, 16–22, 26, 36, 37] and inadequate communication and education around transplant [15–22, 26, 36] are barriers recurrently highlighted by regional, rural, and remote patients across numerous countries, indicating that the current process for completing transplant assessment is not meeting the needs of this population. Across these studies consumers highlight issues around the visibility of transplant as a treatment option (approachability [12]), and accessibility of required testing and assessment appointments (availability [12]). Inequities in service delivery models for KT assessment and education are also explored in these studies, highlighting an inability to meet the needs of this population, or for patients to engage with the service, based on their cultural and socioeconomic requirements (acceptability, appropriateness [12]).

The identified psychosocial and psychological distress [14–21, 36] as well as issues relating to geographical distance from transplant centres [14–17, 19–21, 26, 36] are also recurrent barriers identified by regional, rural, and remote KT patients across other studies. Patients emphasise the lack of locally available healthcare services, including support services to assist transplant recipients with managing the intense stress and anxiety that is often experienced (availability [12]). Patients report the recurrent travel required to unfamiliar cities, challenges with travel and accommodation arrangements, and separation from their family and country as being particularly burdensome, contributing to their psychological distress. This highlights that current models of care provision do not enable transplant recipients from regional, rural, and remote areas to accept and positively engage with the service (acceptability and appropriateness [12]).

The financial burden of KT has been similarly identified across other studies in the context of out-of-pocket expenses related to travel, accommodation, and medical testing [14–17, 21, 24–26, 38]. Consumers report these out-of-pocket expenses are leading to significant financial strain, and patient travel subsidy schemes and government rebates for healthcare services are not providing adequate financial support for transplant recipients in regional, rural, and remote areas, despite the higher travel burden they face (affordability, appropriateness [12]). Interestingly, the cost of ongoing medication supply highlighted as a difficulty faced by participants in this study is mentioned in only a small number of Australian studies [14, 24, 38].

Likewise, the barriers around medication supply and access highlighted in this study have not previously been described in similar studies, which is surprising given that reduced access to medications (as a result of limited pharmacy services) in rural and remote areas is well-documented and globally relevant (availability [12]) [39, 40]. Although not well described in the regional, rural, and remote KT cohort specifically, it has been described in a study of both liver and KT recipients. Although rurality of participants was not defined, rurality was reported by patients as contributing to medication access difficulties, which ultimately affected medication adherence and their ability to engage with treatment (appropriateness [12]) [41]. Some innovative models that have been implemented to address medication access and supply issues in rural and remote areas, include the use of remote dispensing kiosks used in Canada, the United States, and Scotland, and delivery of medications via drones to rural and remote areas of Queensland, Australia [42].

A range of potential solutions have been explored involving the redesign of current KT care provision to address the barriers and challenges experienced by regional, rural, and remote KT recipients identified in this study [43]. Examples of targeted initiatives that have already been implemented or trialled with positive outcomes in various countries include the coordination of work-up testing [44, 45], outreach visits by the KT team [46], novel and/or culturally appropriate KT education [46, 47], and increased psychosocial support through ‘patient mentor’ programs [48, 49]. However, implementing such changes to service delivery models within the constraints of government funded health services remains a significant challenge. Specialised funding streams or targeted grants are therefore often required to support pilot programs (such as those implemented in Australia by the National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce) [48], that can provide evidence to support a strategic shift in resource allocation to achieve sustainable improvements in the delivery of KT care.

Limitations

This study presents the detailed transplant experiences and in-depth perspectives of a diverse cohort of regional, rural, and remote transplant recipients from northern Queensland. The proportion of rural and remote participants was significantly smaller than those in regional centres, however investigators believe this to be a result of additional barriers to participation in research seen in rural and remote communities, such as lack of transportation or insufficient internet connection [50]. The inclusion of participants within northern Queensland only may reduce the transferability of these findings both nationally and internationally, particularly in areas with different KT care service delivery models, low- to middle-income countries, or those with different health care funding structures.

Conclusions

Kidney transplant recipients in regional, rural, and remote areas face numerous difficulties and challenges across the entirety of their transplantation journey. Barriers relate primarily to their geographical distance from specialty transplant services and the lack of locally available medical and support services. Current service delivery models for kidney transplant care and education are struggling to meet the needs of this population, and there is insufficient ongoing financial, medical, and psychological support post-transplant despite the adversities faced. These findings may support translation to the redesign of transplant care provision, however further research is required to explore how current models can be sustainably improved to address inequities in access and the unique needs of regional, rural, and remote transplant recipients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Additional Methods Information

Supplementary Material 2: Focus Group Discussion Guide

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the many kidney transplant recipients who took time to participate in this study.

Abbreviations

- IQR

Interquartile range

- KT

Kidney transplant / transplantation

- KRT

Kidney replacement therapy

- LDKT

Living donor kidney transplantation

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- SRQR

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

- MMM

Modified Monash Model

- FGD

Focus group discussion

Author contributions

Research idea and study design: TKW, BDG, AJM, NSR; data acquisition: TKW; data analysis/interpretation: TKW, NSR; supervision and mentorship: BDG, NSR, AJM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Funding

TKW is supported by a Tropical Australian Academic Health Centre (TAAHC) Clinician Researcher Fellowship. TKW received a research grant from the Far North Queensland Hospital Foundation to conduct this research. AJM is supported by a Queensland Health Advancing Clinical Research Fellowship. No institutions providing funding had any role in study design, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Multisite ethics approval was granted by the Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/2023/QTHS/89342). Participants gave written informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors information - consumer involvement

Co-author NSR has lived experience of both peritoneal dialysis and kidney transplantation and resides in a rural community. NSR has experience in qualitative research and contributed to this study’s design, data analysis, manuscript preparation and supervision of the first author’s PhD candidature.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nicole J. Scholes-Robertson and Andrew J. Mallett contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Tara K. Watters, Email: tara.watters@my.jcu.edu.au

Andrew J. Mallett, Email: Andrew.mallett@health.qld.gov.au

References

- 1.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, Jadhav D, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transpl. 2011;11(10):2093–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liem YS, Bosch JL, Hunink MG. Preference-based quality of life of patients on renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2008;11(4):733–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyld MLR, Wyburn KR, Chadban SJ. Global perspective on kidney transplantation: Australia. Kidney360. 2021;2(10):1641–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitz J, Koch M, Mehrabi A, Schemmer P, Zeier M, Beimler J, et al. Living-donor kidney transplantation: risks of the donor – benefits of the recipient. Clin Transpl. 2006;20(s17):13–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aufhauser DD Jr., Peng AW, Murken DR, Concors SJ, Abt PL, Sawinski D, et al. Impact of prolonged dialysis prior to renal transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2018;32(6):e13260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mudiayi D, Shojai S, Okpechi I, Christie EA, Wen K, Kamaleldin M, et al. Global estimates of capacity for kidney transplantation in world countries and regions. Transplantation. 2022;106(6):1113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health and Aged Care. Modified Monash Model: Commonwealth of Australia; [updated 10th April 2025]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-health-workforce/classifications/mmm. Accessed 12th Feb 2025.

- 8.Axelrod DA, Guidinger MK, Finlayson S, Schaubel DE, Goodman DC, Chobanian M, et al. Rates of solid-organ wait-listing, transplantation, and survival among residents of rural and urban areas. JAMA J Am Med Association. 2008;299(2):202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sypek MP, Clayton PA, Lim W, Hughes P, Kanellis J, Wright J, et al. Access to waitlisting for deceased donor kidney transplantation in Australia. Nephrology. 2019;24(7):758–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis A, Didsbury M, Lim WH, Kim S, White S, Craig JC, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status and geographic remoteness on access to pre-emptive kidney transplantation and transplant outcomes among children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;31(6):1011–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watters TK, Glass BD, Mallett AJ. Identifying the barriers to kidney transplantation for patients in rural and remote areas: a scoping review. J Nephrol. 2024;37(6):1435–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Intern. 2013;12(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. CIHC Competency Framework for Advancing Collaboration. 2024. Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative; 2024. https://cihc-cpis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CIHC-Competency-Framework.pdf. Accessed 12th Feb 2025.

- 14.Scholes-Robertson N, Gutman T, Howell M, Craig JC, Chalmers R, Tong A. Patients’ perspectives on access to dialysis and kidney transplantation in rural communities in Australia. Kidney Intl Rep. 2022;7(3):591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholes-Robertson N, Gutman T, Dominello A, Howell M, Craig JC, Wong G, et al. Australian rural caregivers’ experiences in supporting patients with kidney failure to access Dialysis and kidney transplantation: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;80(6):773–e821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholes-Robertson N, Howell M, Carter SA, Manera KE, Viecelli AK, Au E, et al. Perspectives of a proposed patient navigator programme for people with chronic kidney disease in rural communities: report from National workshops. Nephrology. 2022;27(11):886–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker RC, Hay S, Walker C, Tipene-Leach D, Palmer SC. Exploring rural and remote patients’ experiences of health services for kidney disease in Aotearoa new zealand: an in‐depth interview study. Nephrol (Carlton Vic). 2022;27(5):421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson K, Cunningham J, Devitt J, Preece C, Cass A. Looking back to my family: Indigenous Australian patients’ experience of hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bennett E, Manderson L, Kelly B, Hardie I. Cultural factors in dialysis and renal transplantation among aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in North Queensland. Aust J Public Health. 1995;19(6):610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devitt J, Anderson K, Cunningham J, Preece C, Snelling P, Cass A. Difficult conversations: Australian Indigenous patients’ views on kidney transplantation. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly J, Stevenson T, Arnold-Chamney M, Bateman S, Jesudason S, McDonald S et al. Aboriginal patients driving kidney and healthcare improvements: recommendations from South Australian community consultations. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(5):622–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Walker RC, Abel S, Palmer SC, Walker C, Heays N, Tipene-Leach D. “We need a system that’s not designed to fail Maori”: experiences of racism related to kidney transplantation in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2023;10(1):219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.El-Dassouki N, Wong D, Toews DM, Gill J, Edwards B, Orchanian-Cheff A, et al. Barriers to accessing kidney transplantation among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in canada: a scoping review part 2-East asian, South asian, and african, caribbean, and black Canadians. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:2054358121996834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnieh L, Kanellis J, McDonald S, Arnold J, Sontrop JM, Cuerden M, et al. Direct and indirect costs incurred by Australian living kidney donors. Nephrology. 2018;23(12):1145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath P, Holewa H. It’s a regional thing’: financial impact of renal transplantation on live donors. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghahramani N, Wang C, Sanati-Mehrizy A, Tandon A. Perception about transplant of rural and urban patients with chronic kidney disease; a qualitative study. Nephro Urol Mon. 2014;6(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Liamputtong P. Research methods and evidence-based practice. 4th ed. Victoria: Oxford University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, Brady A, McCann M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(5):443–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Archibald MM. Investigator triangulation:a collaborative strategy with potential for mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2016;10(3):228–50. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Watters TK, Scholes-Robertson NJ, Mallett AJ, Glass BD. Exploring the pharmacist’s role in regional, rural, and remote kidney transplant care: perspectives of health professionals and transplant recipients. Exploratory Res Clin Social Pharm. 2025;18:100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Health and Aged Care. About Australia’s rural health workforce: Australian Government; 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-health-workforce/about#:~:text=where%20they%20live.-,Status%20of%20rural%20health%20in%20Australia,levels%20of%20disease%20and%20injury. Accessed 20th Feb 2025.

- 35.World Health Organization. WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas. Geneva. 2021. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341139/9789240024229-eng.pdf. Accessed 20th Feb 2025. [PubMed]

- 36.Anderson K, Cunningham J, Devitt J, Cass A. The IMPAKT study: using qualitative research to explore the impact of end-stage kidney disease and its treatments on aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(2):223–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra P, Malhotra S, Sharma N, Misra MC, Vij A, Pandav CS. A qualitative approach to understand the knowledge, beliefs, and barriers toward organ donation in a rural community of Haryana - A community based cross-sectional study. Indian J Transplantation. 2021;15(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholes-Robertson N, Blazek K, Tong A, Gutman T, Craig JC, Essue BM, et al. Financial toxicity experienced by rural Australian families with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol (Carlton). 2023;28(8):456–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poudel A, Nissen LM. Telepharmacy: a pharmacist’s perspective on the clinical benefits and challenges. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2016;5:75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Medicine safety: Rural and remote care. Canberra, Australia. 2021. https://www.psa.org.au/advocacy/working-for-our-profession/medicine-safety/medicine-safety-rural-and-remote-care/. Accessed 20th Feb 2025.

- 41.Bendersky VA, Saha A, Sidoti CN, Ferzola A, Downey M, Ruck JM, et al. Factors impacting the medication adherence landscape for transplant patients. Clin Transpl. 2023;37(6):e14962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Department of Health and Aged Care. International comparisons of pharmacy models. 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-12/foi-4778-released-documents-international-comparisons-of-pharmacy-models.pdf. Accessed 20th Feb 2025.

- 43.Watters TK, Glass BD, Scholes-Robertson NJ, Mallett AJ. Health professional experiences of kidney transplantation in regional, rural, and remote Australia. BMC Nephrol. 2025;26(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Formica RN Jr., Barrantes F, Asch WS, Bia MJ, Coca S, Kalyesubula R, et al. A One-Day centralized Work-up for kidney transplant recipient candidates: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kidney Health New Zealand. One Day Renal Transplant Workup2024 30/09/2024. (Autumn 2024). https://www.kidney.health.nz/resources/files/links/kidney-health-newsautumn-24hr-1.pdf. Accessed 6th June 2025.

- 46.Cundale K, McDonald SP, Irish A, Jose MD, Diack J, D’Antoine M, et al. Improving equity in access to kidney transplantation: implementing targeted models of care focused on improving timely access to waitlisting. Med J Aust. 2023;219(S8):S7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Low JK, Crawford K, Manias E, Williams A. The potential of a patient-centred video to support medication adherence in kidney transplantation: A three-phase sequential intervention research. Transpl J Australasia. 2017;26(1):12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cundale K, Hughes J, Owen K, McDonald S. Final Report - National Indigenous Kidney Transplant Taskforce. 2023. https://www.niktt.com.au/finalreport. Accessed 6th June 2025.

- 49.Sullivan C, Dolata J, Barnswell KV, Greenway K, Kamps CM, Marbury Q, et al. Experiences of kidney transplant recipients as patient navigators. Transpl Proc. 2018;50(10):3346–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pelletier CA, Pousette A, Ward K, Fox G. Exploring the perspectives of community members as research partners in rural and remote areas. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Additional Methods Information

Supplementary Material 2: Focus Group Discussion Guide

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.