Abstract

Background

Osimertinib is a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that has been widely applied as a standard first-line treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. However, the risk signals of osimertinib-related myotoxicity have not yet been fully examined. This study aimed to explore osimertinib-related myotoxicity by conducting a real-world disproportionality analysis.

Methods

Data from January 1st 2015 to March 31st 2024 were retrieved from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System database. Reporting odds ratio (ROR), proportional reporting ratio (PRR), and information component (IC) were employed to perform disproportionality analysis.

Results

A total of 121 cases with osimertinib-related myotoxicity were identified and analyzed. The adverse events were mostly reported in females (n = 74, 61.2%) and patients aged over 65 years old (n = 56, 46.3%). The median value of adverse event onset time was 40 (13.3, 164.5). Disproportionality analysis revealed that blood creatine phosphokinase increased (ROR025 = 5.00, IC025 = 2.07, PRR = 6.18), myositis (ROR025 = 2.72, IC025 = 1.26, PRR = 4.22), and myopathy (ROR025 = 1.28, IC025 = 0.63, PRR = 2.32) carried significant risk signals of osimertinib-related myotoxicity.

Conclusions

Our study comprehensively revealed the safety characteristics of osimertinib-associated myotoxicity. The results would offer referable evidence on the safety and prognosis of osimertinib.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-14743-3.

Keywords: Osimertinib, Myotoxicity, Pharmacovigilance, Adverse event, FAERS

Introduction

Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer-induced death globally, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for nearly 85% of all lung cancer types [1, 2]. Around 10–50% of patients with NSCLC carry mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene, and osimertinib is a third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that has been widely applied as a standard first-line treatment in advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutation [3]. Osimertinib was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States in November 2015, and demonstrated better tolerance and efficacy than first- and second-generations of EGFR-TKIs [4].

The adverse events (AEs) of osimertinib have been widely noticed due to its increasing application in clinical practice. The most frequently reported AEs (> 20%) mainly include rash, diarrhea, stomatitis, anemia, neutropenia, fatigue, and cough [5–8]. Other AEs are documented in the “warnings and precautions” of the osimertinib FDA label, including interstitial lung disease, keratitis, cutaneous vasculitis, embryo-fetal toxicity, and cardiomyopathy [8]. Cardiomyopathy has been widely concerned as a typical myotoxicity AE of osimertinib [9], whereas other types of myotoxicity AEs, such as blood creatine phosphokinase (CPK) increased, rhabdomyolysis, myositis, and myopathy, have only been reported occasionally in clinical trials [10–13] and cases with life-threatening outcomes [14–20]. Therefore, additional studies are required to comprehensively reflect the real-world safety profiles of osimertinib.

Pharmacovigilance analysis is a widely accepted method to detect and assess post-marketing adverse drug reactions (ADRs) [21], and its main data sources are individual case safety reports (ICSRs) from ADR databases [22–24]. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) is a global database of spontaneous AE reports, serving as a fundamental tool of drug safety monitoring [25, 26]. Disproportionality analysis is a crucial part of pharmacovigilance study which enables the assessment of rare ADR signals in large-scale dataset [27]. Therefore, our current study aimed to investigate the overall safety profile of osimertinib-related myotoxicity using disproportionality analysis.

Materials and methods

In this study, spontaneous ICSRs submitted from January 1 st 2015 to March 31 st 2024 were extracted from the FAERS database on a single day of May 7th 2024. Reports sharing the same case number were considered duplicate cases and were excluded from the analysis. The target drug was restricted to osimertinib, including both generic names (“osimertinib” and “osimertinib mesylate”) and trade name (“Tagrisso”). The terms of “myotoxicity” were identified based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (Version 27.0), including “blood CPK increased” (code 10,005,470), “rhabdomyolysis” (code 10,039,020), “myositis” (code 10,028,653), and “myopathy” (code 10,028,641).

In descriptive analysis, the demographic characteristics of cases, including number of reports, age, gender, AE outcome, reporter type, reporting country/region, and time to onset (TTO) of AE, were summarized. The pharmacovigilance analysis tool OpenVigil (Version 1.0.2) was applied to calculate TTO, which was defined as the time interval between START_DT (start date of initial osimertinib treatment) and EVENT_DT (occurrence date of myotoxicity AE) [28, 29]. In addition, since FAERS is a voluntary reporting system that inevitably contains missing or incorrect format values, these invalid entries were therefore excluded from the final descriptive analysis.

In disproportionality analysis, reporting odds ratio (ROR), proportional reporting ratio (PRR), and Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (BCPNN), were used to evaluate AE signals based on the 2 × 2 contingency table in Table S1 [30, 31]. The detailed formulas and significant criteria were listed in Table S2. The information component (IC) represents the measure of BCPNN algorithm. If the lower limit confidence interval (CI) of ROR (ROR025) > 1 and lower limit CI of IC (IC025) > 0, the signal is considered statistically significant [32]. In PRR, the signal is significant when PRR ≥ 2 and chi-squared (χ2) ≥ 4 [33].

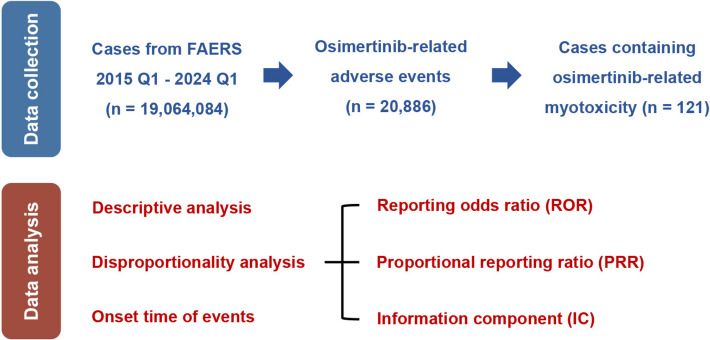

A subsequent sensitivity analysis was performed to compare the TTO and risk signals across different gender subgroups. All data analysis and visualization were performed using R studio (Version 4.1.0) and GraphPad Prism (Version 9.3.1). All methods and findings of this study were conducted based on the REporting of A Disproportionality analysis for drUg Safety signal detection using individual case safety reports in PharmacoVigilance (READUS-PV) guideline [24, 34], and the READUS-PV checklist was provided in Table S3. The detailed procedure of data processing was displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the data collection and data analysis processes

Results

Descriptive analysis

A total of 20,886 osimertinib-related AEs were collected from the FAERS database, and 121 reports were identified after data processing. As displayed in Fig. 2, the number of AEs containing osimertinib-related myotoxicity exhibited a remarkable increase during 2015–2021 and a subsequent fluctuating tendency during 2022–2024. Concurrently, the occurrence rate of osimertinib-related myotoxicity remained relatively stable from 2016–2024.

Fig. 2.

The number of reports and incidence rate of osimertinib-related myotoxicity

The AEs were more frequently reported in females (74 reports, 61.2%) compared to males (31 reports, 25.6%), and AEs were mostly observed in patients aged over 65 years (56 reports, 46.3%). The most common AE was “blood CPK increased” (83 reports, 68.6%), followed by “rhabdomyolysis” (23 reports, 19.0%), “myositis” (20 reports, 16.5%), and “myopathy” (11 reports, 9.1%). Among the 58 cases with recorded AE outcome, most patients were observed in hospitalization state (27 reports, 46.36%). The healthcare professionals (117 reports, 96.7%) appeared to be the most frequent reporters compared to consumers (4 reports, 3.3%). Japan had the greatest number of reports (43 reports, 35.5%), followed by the United States (14 reports, 11.6%) and France (11 reports, 9.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of reports associated with osimertinib-related myotoxicity

| Characteristics | Case Number, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of reports | 121 |

| Age | |

| < 18 | 2 (1.6) |

| 18–65 | 34 (28.1) |

| > 65 | 56 (46.3) |

| Unknown | 29 (24.0) |

| Median age, year (range) | 68 (7–90) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 74 (61.2) |

| Male | 31 (25.6) |

| Unknown | 16 (13.2) |

| Myotoxicity adverse eventsa | |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 83 (68.6) |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 23 (19.0) |

| Myositis | 20 (16.5) |

| Myopathy | 11 (9.1) |

| Outcome of eventsb | |

| Death | 5 (4.1) |

| Life-threatening | 8 (6.6) |

| Disabled | 5 (4.1) |

| Hospitalization | 27 (22.3) |

| Non-serious | 13 (10.7) |

| Other outcomes | 94 (77.7) |

| Reporter type | |

| Consumer | 4 (3.3) |

| Healthcare Professional | 117 (96.7) |

| Reporting country/region | |

| Japan | 43 (35.5) |

| United States | 14 (11.6) |

| France | 11 (9.1) |

| Other | 11 (9.1) |

| Unknown | 42 (34.7) |

| Time to onset of adverse events | |

| 0–30 days | 15 (39.5) |

| 30–60 days | 6 (15.8) |

| 60–90 days | 4 (10.5) |

| 90–180 days | 5 (13.1) |

| 180–360 days | 6 (15.8) |

| > 360 days | 2 (5.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 40 (13.3, 164.5) |

Abbreviations Q1 Lower Quartile, Q3 Upper Quartile

aSome cases may contain more than one myotoxicity adverse events

bSome cases may contain more than one outcome

A total of 38 reports were ultimately included after removing entries containing inappropriate values of TTO. As listed in Table 1, the value of median TTO was 40 (13.3, 164.5), and most AEs were observed within 30 days following osimertinib treatment (total:15 reports, 39.5%; female: 9 reports, 34.6%, male: 6 reports, 50.0%) (Fig. 3A). Likewise, the mainly reported myotoxicity AE was “blood CPK increased” within gender subgroup (female: 53 reports, 60.9%; male: 19 reports, 54.3%) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The distribution of reports within each gender for (A) time to event onset and (B) myotoxicity adverse events

Disproportionality analysis

As shown in Table 2, significant disproportionality signals were found in total myotoxicity AEs (ROR025 = 2.63, IC025 = 1.37, PRR = 3.10, χ2 = 194.51). Regarding each subtype, “blood CPK increased” (ROR025 = 5.00, IC025 = 2.07, PRR = 6.18, χ2 = 358.27), “myositis” (ROR025 = 2.72, IC025 = 1.26, PRR = 4.22, χ2 = 48.85), and “myopathy” (ROR025 = 1.28, IC025 = 0.63, PRR = 2.32, χ2 = 8.23) represented significant signals, whereas “rhabdomyolysis” (ROR025 = 0.72, IC025 = 0.07, PRR = 1.08, χ2 = 0.14) was not found to have a significant association with osimertinib.

Table 2.

Pharmacovigilance metrics for reported cases of osimertinib-related myotoxicity

| Myotoxicity AEs | Case Number, N | ROR (ROR025) | PRR (χ2) | IC (IC025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 137 | 3.11 (2.63) | 3.10 (194.51) | 1.62 (1.37) |

| Blood CPK increased | 83 | 6.20 (5.00) | 6.18 (358.27) | 2.58 (2.07) |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 23 | 1.08 (0.72) | 1.08 (0.14) | 0.11 (0.07) |

| Myositis | 20 | 4.22 (2.72) | 4.22 (48.85) | 1.96 (1.26) |

| Myopathy | 11 | 2.32 (1.28) | 2.32 (8.23) | 1.13 (0.63) |

Abbreviations AE Adverse events, CPK Creatine phosphokinase, ROR Reporting odds ratio, ROR 025 The lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of the ROR, PRR Proportional reporting ratio, χ2 Chi-squared, IC Information component, IC025 The lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of the IC

The results of disproportionality analysis for signals within each gender were presented in Fig. 4. We found significant signals of “blood CPK increased” (ROR025 = 2.85, IC025 = 1.41, PRR = 3.72), “myositis” (ROR025 = 3.66, IC025 = 1.39, PRR = 6.31), and “myopathy” (ROR025 = 1.28, IC025 = 0.59, PRR = 2.85) in female patients, while “myositis” (ROR025 = 1.06, IC025 = 0.48, PRR = 2.54) and “myopathy” (ROR025 = 1.11, IC025 = 0.51, PRR = 2.68) were discovered to have significant association with osimertinib in male patients.

Fig. 4.

The pharmacovigilance metrics of osimertinib-related myotoxicity within each gender

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first real-world pharmacovigilance analysis examining the association between osimertinib and myotoxicity. In this study, the AEs were primarily observed in patients over 65 years old (46.3%), thus echoed the results from clinical trials AURA and FLAURA that the number of AE was higher in participants over the age of 65 [35, 36]. Hence, it is crucial for clinicians to remain vigilant regarding osimertinib-related AEs in elderly patients as the outcome of AEs can be potentially life-threatening. Notably, we found that AEs of osimertinib-associated myotoxicity were more commonly observed in females (61.2%) compared to males (25.6%). It has been established that women generally have higher occurrence rate of AEs than men due to the differences in physiological characteristics, volume of distribution, and systemic clearance [37–39]. More recent findings revealed that women exhibited greater susceptibility to non-smoking-induced lung cancer than men, owning to factors such as hormonal influences, environmental exposures, and genetic factors [40–43]. Therefore, it would be important for clinicians to pay attention to these gender differences and develop gender-specific therapies for patients. In addition, our TTO results filled the current knowledge gap, and suggested that close monitoring of patients would be essential, particularly during the first month after osimertinib treatment.

Osimertinib-related myotoxicity has not been explicitly labeled as ADRs in FDA instruction. Data of clinical trials showed that osimertinib-related myositis occurs in less than 1% of subjects, and serum CPK elevation was reported in only one case [35, 36]. In clinical case reports, osimertinib-related rhabdomyolysis was reported in one case with serious outcome of metabolic acidosis and electrolyte disturbances [17], and myositis was reported in few severe case reports [14, 44]. In this study, the 121 cases collected indicated that osimertinib-associated myotoxicity AEs might be underreported in real-world situation and therefore warrants attention in clinical practice.

In our disproportionality analysis, significant signals were identified in blood CPK increased, myositis, and myopathy. Rhabdomyolysis, on the contrary, displayed a weak association with osimertinib medication. One reason behind it might be that blood CPK increased (more than 10 times of upper limit) is an intuitive clinical manifestation of rhabdomyolysis, which led to a decreased number of AEs reported for rhabdomyolysis. Additionally, muscle pain and weakness are common ADRs of early myotoxicity, and patients may only consider them as fatigue [45]. Hence, it would be valuable to validate a comprehensive scoring system of osimertinib-associated myotoxicity for a clear clinical diagnosis.

In fact, myotoxicity with various levels of severity have been reported in the use of other EGFR-TKIs, including erlotinib, gefitinib, and almonertinib [18, 46]. In non-EGFR signaling TKIs, the incidence of CPK elevation has been reported by over 35% in patients receiving brigatinib, binimetinib, or gilteritinib [47]. The myotoxicity AEs of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have received growing attention as well. The common myotoxicity AEs in clinical trials are muscle pain (incidence of 4–5%), myocarditis (incidence of 16–32%), and myositis (incidence of 80%) [48–50]. The loss of immune tolerance is the key contributor of ICI-induced myotoxicity [51]. In chemotherapies, it is reported that drugs with neurotoxicity, such as taxanes, may induce myositis by triggering chronic inflammation [52, 53]. Apart from anticancer agents, various medications were discovered to have common level of myotoxicity ADRs (incidence over 10%), such as antidyslipidemia drugs, beta blockers, antipsychotics, donepezil, and colchicine [47, 54–56]. In this study, the impact of these medications could be excluded as we only found 5 cases containing their concurrent administration.

The exact mechanisms of osimertinib-induced myotoxicity remains to be elucidated, and the leading hypothesis include direct myocyte toxicity [57], mitochondrial dysfunction [58], electrolyte disturbances [59], and immune-mediated mechanisms [60]. CPK acts as a key enzyme in muscle function, and tyrosine kinase plays a vital role in muscle metabolism [47]. TKIs may cause muscle damage and elevate serum CPK level by inhibiting the activity of tyrosine kinase in muscle tissue [61, 62]. Nevertheless, future research is required to further reveal the underlying mechanisms of osimertinib-related myotoxicity.

The clinical management of osimertinib-associated myotoxicity is mainly symptomatic management and close surveillance of CPK levels. Several clinical strategies are available to alleviate muscle symptoms, such as switching to another TKI, and supplementation with calcium, magnesium, and B vitamins [63]. Follow-up studies focusing on the management of osimertinib-related myotoxicity would be necessary for the optimal treatment of patients. Furthermore, vigorous exercise is not recommended as it may aggravate myotoxicity-related symptoms and cause rhabdomyolysis [64]. It is suggested that if CPK rises to 5–10 times of upper limit, TKI treatment should be suspended until condition improves, and discontinued if there is no improvement with suspension [47].

Interestingly, there have been studies showing that CPK elevation induced by multiple TKIs (e.g., imatinib, aumolertinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib) seem to be positively correlated with improved overall survival and better treatment response [60, 65]. These findings would be valuable for physicians to weigh efficacy and side effects of osimertinib. However, we should emphasize that if CPK is significantly elevated or severe symptoms occur, dose adjustment, drug discontinuation, or additional interventions are required.

There were several limitations existed in our present research. First, since FAERS is a spontaneous AE reporting system, invalid data, incomplete data, and reporting bias are thereby unavoidable. Second, due to the intrinsic limitation of pharmacovigilance study, the disproportionality analysis alone was unable to establish a firm causality of AE. Third, the confounders of AEs were not visible in FAERS database, including drug interactions, medical histories, and laboratory tests results. Integration of other data sources, including preclinical experiments, clinical trials, and case reports, would aid in the improvement of these limitations.

Conclusions

In summary, osimertinib-related myotoxicity is a series of underrated ADRs that warrants clinical attention. Our results would expand the understanding of the safe use of osimertinib and contribute to the development of personalized anticancer therapies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank FAERS for the free access of data. We also thank Dr. Ruwen Böhm for the free use of OpenVigil FDA.

Authors’ contributions

YT contributed to the conception and design of the study. YT and QS collected and analyzed the data. YT drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82104223 and 82204372), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515110008), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202102021022, 2023A04J0601, 2024A04J10001, and 2025A03J3308), Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project for Medicine and Healthcare (20211A011044), and Guangzhou Municipal Key Discipline in Medicine (2025–2027).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since all data of our study was originated from public databases with non-identifiable datasets, no ethical approval is required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):1046–61. 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-14-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Mao T, Wang J, Zheng H, Hu Z, Cao P, et al. Toward the next generation EGFR inhibitors: an overview of osimertinib resistance mediated by EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):71. 10.1186/s12964-023-01082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aschenbrenner DS. New adjuvant drug for lung cancer. Am J Nurs. 2021;121(4):23–4. 10.1097/01.Naj.0000742492.40886.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M–positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):629–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa1612674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jänne PA, Yang JCH, Kim DW, Planchard D, Ohe Y, Ramalingam SS, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR Inhibitor–Resistant Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England J Med. 2015;372(18):1689-99.10.1056/NEJMoa1411817 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Greig SL. Osimertinib: first global approval. Drugs. 2016;76(2):263–73. 10.1007/s40265-015-0533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand K, Ensor J, Trachtenberg B, Bernicker EH. Osimertinib-Induced Cardiotoxicity: a retrospective review of the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS). JACC CardioOncology. 2019;1(2):172–8. 10.1016/j.jaccao.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J-F, Chen Y-Z, Kawabata S, Li Y-H, Wang Y. Identification of Light-Independent Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Mutants Induced by Ethyl Methane Sulfonate in Turnip “Tsuda” (Brassica rapa). Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goss G, Tsai C-M, Shepherd FA, Bazhenova L, Lee JS, Chang G-C, et al. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1643–52. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30508-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akamatsu H, Katakami N, Okamoto I, Kato T, Kim YH, Imamura F, et al. Osimertinib in Japanese patients with EGFR T790M mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: AURA3 trial. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(6):1930–8. 10.1111/cas.13623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soria J-C, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley F, Fitzgerald BG, Bhardwaj AS, Siraj I, Smith C. Life-threatening myositis in a patient with EGFR-mutated NSCLC on osimertinib: case report. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3(1):100260. 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parafianowicz P, Krishan R, Beutler BD, Islam RX, Singh T. Myositis - a common but underreported adverse effect of osimertinib: case series and review of the literature. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2020;25:100254. 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimoto H, Matsumoto S, Tsuji Y, Sugimoto K. Elevated serum creatine kinase levels due to osimertinib: a case report and review of the literature. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022;28(2):489–94. 10.1177/10781552211042271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Zhang Y. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient with advanced lung cancer treated with osimertinib: a case report. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2023;12(3):629–36. 10.21037/tlcr-22-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ram A, Siu CT, Mukherjee A, Gupta R. Osimertinib-induced myositis in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e67597. 10.7759/cureus.67597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamasaki M, Matsumoto N, Nakano S, Kawamoto K, Taniwaki M, Izumi Y, et al. Osimertinib for the treatment of EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma complicated with dermatomyositis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56(12):822–3. 10.1016/j.arbres.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujioka S, Kitajima T, Itotani R. Myositis in a patient with advanced lung cancer treated with osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):e137–9. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croteau D, Pinnow E, Wu E, Muñoz M, Bulatao I, Dal Pan G. Sources of evidence triggering and supporting safety-related labeling changes: a 10-year longitudinal assessment of 22 new molecular entities approved in 2008 by the US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Saf. 2022;45(2):169–80. 10.1007/s40264-021-01142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham M, Cheng F, Ramachandran K. A comparison study of algorithms to detect drug-adverse event associations: frequentist, Bayesian, and machine-learning approaches. Drug Saf. 2019;42(6):743–50. 10.1007/s40264-018-00792-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tau N, Shochat T, Gafter-Gvili A, Tibau A, Amir E, Shepshelovich D. Association between data sources and US food and drug administration drug safety communications. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1590–2. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fusaroli M, Salvo F, Begaud B, AlShammari TM, Bate A, Battini V, et al. The reporting of a disproportionality analysis for drug safety signal detection using individual case safety reports in PharmacoVigilance (READUS-PV): development and statement. Drug Saf. 2024;47(6):575–84. 10.1007/s40264-024-01421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong CK, Ho SS, Saini B, Hibbs DE, Fois RA. Standardisation of the FAERS database: a systematic approach to manually recoding drug name variants. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(7):731–7. 10.1002/pds.3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(7):796–803. 10.7150/ijms.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(7):796–803. 10.7150/ijms.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Böhm R, von Hehn L, Herdegen T, Klein HJ, Bruhn O, Petri H, et al. OpenVigil FDA - inspection of U.S. American adverse drug events pharmacovigilance data and novel clinical applications. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0157753. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dias P, Penedones A, Alves C, Ribeiro CF, Marques FB. The role of disproportionality analysis of pharmacovigilance databases in safety regulatory actions: a systematic review. Curr Drug Saf. 2015;10(3):234–50. 10.2174/1574886310666150729112903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bate A, Lindquist M, Edwards IR, Olsson S, Orre R, Lansner A, et al. A bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(4):315–21. 10.1007/s002280050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Puijenbroek EP, Bate A, Leufkens HG, Lindquist M, Orre R, Egberts AC. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11(1):3–10. 10.1002/pds.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans SJ, Waller PC, Davis S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2001;10(6):483–6. 10.1002/pds.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fusaroli M, Salvo F, Khouri C, Raschi E. The reporting of disproportionality analysis in pharmacovigilance: spotlight on the READUS-PV guideline. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2024; 15:2024.10.3389/fphar.2024.1488725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Chmielecki J, Gray JE, Cheng Y, Ohe Y, Imamura F, Cho BC, et al. Candidate mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line osimertinib in EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1070. 10.1038/s41467-023-35961-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beierle I, Meibohm B, Derendorf H. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;37(11):529–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotreau MM, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. The influence of age and sex on the clearance of cytochrome P450 3A substrates. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(1):33–60. 10.2165/00003088-200544010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.del Carmen C-P, Flores-Murrieta FJ. Gender differences in the pharmacokinetics of oral drugs. Pharmacology & Pharmacy. 2011;2(1):31–41. 10.4236/pp.2011.21004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong S, Borlak J. Sex disparities in non-small cell lung cancer: mechanistic insights from a cRaf transgenic disease model. EBioMedicine. 2023;95:104763. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su Y, Zhang H, Xu F, Kong J, Yu H, Qian B. DNA repair gene polymorphisms in relation to non-small cell lung cancer survival. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(4):1419–29. 10.1159/000430307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barta JA, Powell CA, Wisnivesky JP. Global epidemiology of lung cancer. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1):8. 10.5334/aogh.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mederos N, Friedlaender A, Peters S, Addeo A. Gender-specific aspects of epidemiology, molecular genetics and outcome: lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000796. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujioka S, Kitajima T, Itotani R. Myositis in a patient with advanced lung cancer treated with Osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):e137–9. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, Vladutiu GD, Raal FJ, Ray KK, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European atherosclerosis society consensus panel statement on assessment, aetiology and management. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(17):1012–22. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji W, Jiang Y, Wei Y, He K, Mu H, Wen Q, et al. Effect of food intake on pharmacokinetics of oral almonertinib: a randomized crossover trial in healthy Chinese participants. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2022;11(9):1046–53. 10.1002/cpdd.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang H, To KKW. Serum creatine kinase elevation following tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment in cancer patients: symptoms, mechanism, and clinical management. Clin Transl Sci. 2024;17(11):e70053. 10.1111/cts.70053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizvi NA, Mazières J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):257–65. 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liewluck T, Kao JC, Mauermann ML. PD-1 inhibitor-associated myopathies: emerging immune-mediated myopathies. J Immunother. 2018;41(4):208–11. 10.1097/cji.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miernik S, Matusiewicz A, Olesińska M. Drug-induced myopathies: a comprehensive review and update. Biomedicines. 2024;12(5):987. 10.3390/biomedicines12050987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solimando AG, Crudele L, Leone P, Argentiero A, Guarascio M, Silvestris N, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related myositis: from biology to bedside. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3054. 10.3390/ijms21093054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller FW, Lamb JA, Schmidt J, Nagaraju K. Risk factors and disease mechanisms in myositis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(5):255–68. 10.1038/nrrheum.2018.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demırel N, Demır M. Docetaxel associated myositis. Journal of Chemotherapy.1–6.10.1080/1120009X.2025.2505806 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Obayashi S, Tomomatsu K, Urata M, Tanaka J, Niimi K, Hayama N, et al. Rhabdomyolysis caused by gefitinib overdose. Intern Med. 2022;61(10):1577–80. 10.2169/internalmedicine.8168-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Aggarwal R. Approach to asymptomatic creatine kinase elevation. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(1):37–42. 10.3949/ccjm.83a.14120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomaszewski M, Stępień KM, Tomaszewska J, Czuczwar SJ. Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63(4):859–66. 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuji K, Takemura K, Minami K, Teramoto R, Nakashima K, Yamada S, et al. A case of rhabdomyolysis related to sorafenib treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2013;6(3):255–7. 10.1007/s12328-013-0381-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang H, Qiu S, Yao T, Liu G, Liu J, Guo L, et al. Transcriptomics coupled with proteomics reveals osimertinib-induced myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol Lett. 2024;397:23–33. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2024.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prenggono MD, Yasmina A, Ariyah M, Wanahari TA, Hasrianti N. The effect of imatinib and nilotinib on blood calcium and blood potassium levels in chronic myeloid leukemia patients: a literature review. Oncol Rev. 2021;15(2):547. 10.4081/oncol.2021.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang Y, Su Z, Lin Y, Xiong Y, Li C, Li J, et al. Prognostic and predictive impact of creatine kinase level in non-small cell lung cancer treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(9):3771–81. 10.21037/tlcr-21-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leroy MC, Perroud J, Darbellay B, Bernheim L, Konig S. Epidermal growth factor receptor down-regulation triggers human myoblast differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71770. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nersesjan V, Hansen K, Krag T, Duno M, Jeppesen TD. Palbociclib in combination with simvastatin induce severe rhabdomyolysis: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):247. 10.1186/s12883-019-1490-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deininger MWN, O’Brien SG, Ford JM, Druker BJ. Practical management of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(8):1637–47. 10.1200/jco.2003.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JCH, Han JY, Hochmair MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK inhibitor-naive advanced ALK-positive NSCLC: final results of phase 3 ALTA-1L trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(12):2091–108. 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bankar A, Lipton JH. Association of creatine kinase elevation with clinical outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia: a retrospective cohort study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022;63(1):179–88. 10.1080/10428194.2021.1971219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.