Highlights

-

•

Sarcopenic indexes capture different health parameters;.

-

•

Muscle power improves the associations of sarcopenia with health parameters;.

-

•

Sarcopenia operationalized according to muscle power displays exclusive and stronger associations with health parameters.

Keywords: Frailty, Disability, Mobility, Physical performance, Intrinsic capacity, Mediterranean diet

Abstract

Background and Objectives

The present study examined the associations between sarcopenia, operationalized through muscle strength or muscle power, and health parameters in Italian community-dwelling older adults.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Unconventional settings across Italy.

Participants

Italian older adults (65+ years) who provided a written informed consent.

Measurements

Physical function was evaluated according to isometric handgrip strength (IHG) and 5-time sit-to-stand (5STS) performances. Muscle power parameters were estimated based on 5STS values. Sarcopenia was operationalized according to the presence of low physical function (i.e., IHG or 5STS), or low muscle power, plus low appendicular skeletal muscle mass. Health parameters included the capacity to perform the 400 m test, adherence to the Mediterranean (MED) diet, practice of physical activity (PA), blood pressure (BP) values, blood concentration of total cholesterol and glucose, verbal fluency, sleep quality, and self-reported health status.

Results

Results indicated that sarcopenic indexes had a poor-to-moderate level of agreement. Moreover, results indicated that operationalizing sarcopenia using muscle power measures provided exclusive or stronger associations with health parameters. Specifically, older adults classified as sarcopenic based on muscle power values were less likely to complete the 400-meter walk test, more likely to engage in PA, reported poorer self-rated health, and showed lower adherence to the MED diet.

Conclusions

Findings of the present study indicated that sarcopenia indexes based on muscle strength or muscle power capture different aspects of older adults’ health. Specifically, operationalizing sarcopenia using muscle power measures provided exclusive or stronger associations with health parameters.

1. Introduction

Sarcopenia was first described by Roubenoff as an age-related condition assumed to reflect the effects of muscle loss on physical performance [[1], [2], [3]]. Since then, this concept has been extensively reviewed, with working groups composed of experts in the field established to propose operational definitions, diagnostic criteria, and clinical implications [4,5]. The current operational definitions of sarcopenia by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [6] and the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) [7] suggest that dynapenia, significant losses of muscle strength, be the primary element of sarcopenia, owing to its stronger associations with health parameters compared with muscle mass.

However, the validity and capacity of this operationalization paradigm has been challenged by investigations showing no significant associations between sarcopenia and health-related parameters [8], and limited capacity of this construct to identify individuals at higher risk of negative events [9]. As such, it has been proposed that the elements included in the current operationalization need to be revised to improve the ability of sarcopenia to represent muscle failure and predict negative events [10,11].

Muscle power, the capacity of muscles to generate strength rapidly, declines earlier and to a greater extent than muscle strength during aging [12]. Furthermore, many investigations have observed that this physical capacity is a better predictor of physical independence, functional performance, mobility, and death than muscle strength [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. Hence, muscle power might be the best available indicator of muscle failure, and operationalizing sarcopenia according to reductions in this physical capacity could improve the ability of the current paradigm to identify individuals at risk of negative health events [10].

Based on these premises, the present study examined the associations between sarcopenic indexes, operationalized through muscle strength and power, and health related parameters in community-dwelling older adults.

2. Materials and methods

Data of the present investigation were gathered from the Longevity Check-up 8+ (Lookup 8+) project database. Sampling characteristics, procedures, and other results have been published elsewhere [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Lookup 8+ is an ongoing initiative developed by the Department of Geriatrics of the Fondazione Policlinico “Agostino Gemelli” IRCCS at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Rome, Italy). The project was designed to foster healthy and active aging by raising awareness among the general public on the importance of modifiable risk factors for chronic diseases [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]].

Recruitment was conducted among people visiting public spaces (e.g., exhibitions, shopping centers) and those adhering to prevention campaigns promoted by our institution. As previously described, recruitment activities were carried out in small (<100,000 inhabitants), medium (100,000–250,000 inhabitants), and large cities (>250,000 inhabitants) to achieve a comprehensive geographic coverage of mainland Italy and major islands. In large cities, participants were recruited in different locations to maximize the representation of the sociodemographic characteristics of inhabitants. Until now, events were conducted in 41 Italian cities, including Milan, Rome, Catania, Genoa, Caserta, Grosseto, Bologna, Modena, Anzio, Terni, Perugia, Viterbo, Naples, Cesena, Cannara, Fontecchio, Ancona, San Gabriele Piozzano, Madonna di Campiglio, Capalbio, Pesaro, Vasto, Ovindoli, Vicenza, Bardolino, Paestum, Olbia, Gaeta, Pinzolo, Treviso, Ischia, Florence, Forte dei Marmi, Palermo, Pistoia, Capodimonte, Cosenza, Eboli, Pescara, Cagliari, and Brindisi.

These cities span the entire Italian peninsula—from the northern regions, such as Lombardy and Veneto, to the central areas like Tuscany and Umbria, and down to the southern territories and islands, including Sicily and Sardinia. This wide geographical coverage not only underscores the inclusive and far-reaching nature of the Lookup 8+, but also reflects its capacity to reflect the health status of the Italian population and strong resonance with communities across diverse cultural, economic, and social landscapes.

The Lookup 8+ protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (protocol #: A.1220/CE/2011) and each participant provided written informed consent prior to enrolment. The manuscript was prepared in compliance with the STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies [23].

2.1. Participants

From 1 June 2015 to 31 December 2023, 17,576 community-dwelling adults aged 18+ years participated in the study. Exclusion criteria were inability or unwillingness to provide written informed consent, self-reported pregnancy, and inability to perform the physical function tests, as per the study protocol. For the present investigation, only participants aged 65+ years, with body mass index (BMI) values ≥18.5 kg/m2 and no missing data for the study variables, were included, totaling 2266 participants (15,310 excluded).

2.2. Data collection

Participants received a structured interview to collect information on lifestyle habits, followed by measurement of anthropometric parameters, including height and weight. The BMI was calculated as the ratio between body weight (kg) and the square of height (m2).

2.3. Sarcopenic indexes

Sarcopenia was identified according to the simultaneous presence of dynapenia, or low muscle power, and low appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) [6]. Muscle strength was assessed by isometric handgrip strength (IHG) and 5-time sit-to-stand (5STS) testing. Participants underwent IHG testing while sitting comfortably on a chair with their shoulders neutral. The arm being assessed had the elbow flexed at 90° near the torso, and the hand neutral with thumbs up. A maximal contraction was performed over four seconds using a handheld hydraulic dynamometer (North Coast Medical, Inc., Morgan Hill, CA, USA). For the 5STS test, participants had to get up from a chair as quickly as they could while keeping their arms crossed at their chest. Timing started when participants raised their buttocks off the chair and was halted when they were seated at the conclusion of the fifth seat.

ASM was estimated from the calf circumference of the dominant leg. The measure was taken at the largest girth between ankle and knee joints using an anthropometric tape while the participant was in a seated position. ASM was subsequently calculated according to the following formula [24]:

-

(1)

ASM = −10.427 + (calf circumference (cm) × 0.768) −(age × 0.029) + (sex (male = 1, female = 0)) × 7.523.

5STS performance was used to calculate absolute muscle power (AMP), relative muscle power (adjusted by body weight, RMP), allometric muscle power (adjusted by height, ALMP), and specific muscle power (adjusted by ASM, SMP) according to the equations proposed by Alcazar et al. [25]:

-

(2)

Absolute muscle power (W) = (Body weight (kg) × 0.9 × g × [height (m) × 0.5 - chair height (m)])/([(5STS test time (s))/(no. of STS repetitions)] × 0.5);

-

(3)

Relative muscle power (W/kg) = (Absolute muscle power (W))/(Body weight (kg));

-

(4)

Allometric muscle power (W/m2) = (Absolute muscle power (W))/(Height (m2));

-

(5)

Specific muscle power (SMP) (W/kg) = (Absolute muscle power (W))/ASM (kg).

Then, six sarcopenic indexes were created according to the recommendations and cutoff points of the EWGSOP, and sample- and sex-based 25th percentiles, as follows:

-

(1)

sarcIHG= Low IHG (men: <27 kg, women: 16 kg) + low ASM (men: <20 kg, women: < 16 kg);

-

(2)

sarc5STS= Low 5STS (>15 s) + low ASM (men: <20 kg, women: < 16 kg);

-

(3)

sarcAMP= Low AMP (men: <298.7 W, women: <193.5 W) + low ASM (men: <20 kg, women: < 16 kg);

-

(4)

sarcRMP= Low RMP (men: <3.9 W/kg, women: <3.1 W/kg) + low ASM (men: <20 kg, women: < 16 kg);

-

(5)

sarcALMP= Low ALMP (men: <102.3 W/m², women: <78.0 W/m²) + low ASM (men: <20 kg, women: < 16 kg);

-

(6)

sarcSMP= Low SMP (men: <13.0 W/kg, women: <12.6 W/kg) + low ASM (men: <20 kg, women: < 16 kg).

2.4. Health parameters

The capacity to perform the 400 m test was assessed by the question: “Do you have any difficulty in walking 400 m?”. The possible answers were “Yes” or “No”. Adherence to the Mediterranean (MED) diet was assessed using a modified version of the Medi-Lite score [22]. The Medi-Lite scoring system considers nine food categories: (1) fruit, (2) vegetables, (3) grains, (4) legumes, (5) fish and fish products, (6) meat and meat products, (7) dairy products, (8) alcohol, and (9) olive oil. For each food group traditionally included in the MED diet (i.e., fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, and fish), a score ranging from 2 (greatest consumption) to 0 (lowest consumption) was attributed. For food items not included among typical MED diet ingredients, such as meat, meat derivatives, and dairy products, 2 points were assigned to the lowest consumption, 1 to intermediate consumption, and 0 to the greatest consumption. As for olive oil, 2 points were assigned to daily intake, 1 point to frequent use, and 0 for occasional consumption. Alcohol consumption was not recorded, and the corresponding item was therefore excluded from the Medi-Lite scoring. Consequently, the highest possible Medi-Lite score was 16 instead of 18. A score of 12 or above indicated high MED diet adherence, a score from 9 to 11 indicated good adherence, and a score of 8 or below indicated low adherence. Regular participation in physical activity (PA), was considered as the regular practice of walking, aerobic, resistance, stretch, or any type of exercise, at least two time a week. Accordingly, participants were considered either physically active or inactive. Blood pressure (BP) was measured with a clinically validated Omron M6 electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron, Kyoto, Japan), according to recommendations from international guidelines. Total cholesterol was measured from capillary blood samples using disposable electrode strips based on a reflectometric system with a portable device (MultiCare-In, Biomedical Systems International Srl, Florence, Italy). The same device was employed to measure random blood glucose using disposable reagent strips based on an amperometric system. Sleep quality was assessed using a questionnaire with a Likert scale. Participants were asked, “How has your sleep quality been in the past month?”. Possible answers were “very good”, “quite good”, “quite bad”, “very bad”. Verbal fluency was assessed by asking participants to name as many words as possible, beginning with the letter 'F' within 30 s. Self-reported health status was assessed by asking participants to evaluate their overall health status. Respondents selected one of four options: (1) excellent, (2) good, (3) fair, or (4) poor.

2.5. Covariates

Smoking status was defined as follows current smoker (has smoked 100+ cigarettes in lifetime and currently smokes cigarettes), and no current smoker. Schooling was measured in years of formal education. Participants provided information on the use of antihypertensive, cholesterol-lowering, and antidiabetic drugs. Participants were also asked if they were fasting for at least 8 h prior to evaluation.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of variables was ascertained via the Shapiro–Wilk test. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons among groups according to sarcopenia status were performed using independent t-tests. Unadjusted and adjusted linear regressions were conducted to examine the associations between sarcopenic indexes and BP, blood glucose and blood cholesterol levels, and verbal fluency. Unadjusted and adjusted binary logistic regressions were performed to investigate the association between sarcopenia indexes and the capacity to perform the 400 m test and PA practice. Unadjusted and adjusted ordinal regressions were conducted to examine the associations between sarcopenia indexes and adherence to the MED diet, sleep quality, and self-reported health status. All models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and smoking status. Analysis involving BP, blood glucose, and blood cholesterol, as dependent variables, were adjusted for the use of antihypertensive, cholesterol-lowering, and antidiabetic drugs, respectively. Analysis for blood glucose was also adjusted for fasting state. For verbal fluency, schooling was included as a covariate. False discovery rate (FDR) for multiple comparisons was controlled using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) was calculated to assess the model fit and determine the best-fitting model among those tested. Fleiss' Kappa was used to test the level of agreement among the multiple sarcopenic indexes. Significance was set at 5 % (p < 0.05) for all tests. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), except for Fleiss' Kappa, which was conducted using Rstudio 4.4.1 (PBC, Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Main characteristics

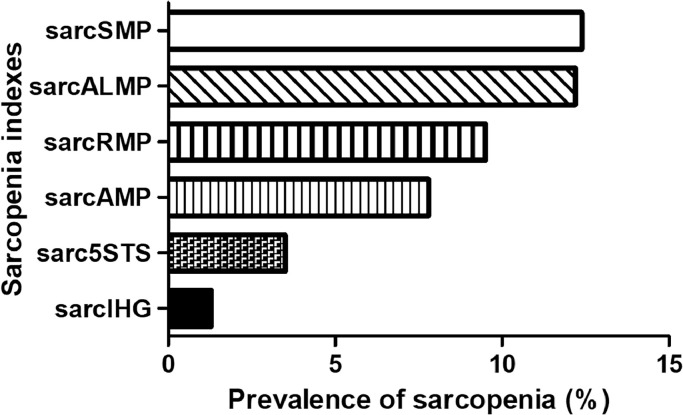

The main characteristics of the participants of the present study are shown in Table 1. The prevalence of sarcopenia was 1.3 %, 3.5 %, 7.8 %, 9.5 %, 12.2 %, and 12.4 % when this condition was operationalized according to 5STS, IHG, SMP, RMP, ALMP, and AMP, respectively (Fig. 1). Fleiss' Kappa results indicated a significant poor-to-moderate (κ= 0.426) level of agreement among the models.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of study participants according to sarcopenia indexes (n = 2266).

| Variables | sarcIHG |

sarc5STS |

sarcAMP |

sarcRMP |

sarcALMP |

sarcSMP |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Age, years | 67.6 ± 1.8 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.6 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.6 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.5 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.7 | 67.4 ± 1.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.4 ± 4.9 | 26.2 ± 4.0 | 29.5 ± 7.8* | 26.3 ± 4.0 | 23.6 ± 3.5* | 26.7 ± 4.0 | 25.3 ± 4.0 | 25.8 ± 4.7 | 23.1 ± 3.4* | 26.9 ± 3.9 | 23.9 ± 3.8* | 26.3 ± 3.9 |

| IHG, kg | 14.8 ± 3.8* | 30.2 ± 9.8 | 23.5 ± 9.4* | 29.3 ± 10.0 | 22.1 ± 6.5* | 30.0 ± 10.1 | 22.1 ± 6.6* | 29.8 ± 10.1 | 22.5 ± 6.7* | 29.9 ± 10.2 | 22.2 ± 6.6* | 29.8 ± 10.2 |

| 5STS, s | 9.4 ± 2.8* | 8.5 ± 2.2 | 18.9 ± 5.3* | 8.4 ± 1.8 | 10.3 ± 2.9* | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 11.3 ± 2.9* | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 10.5 ± 2.9* | 7.8 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 3.3* | 7.8 ± 1.4 |

| AMP, W | 205.9 ± 61.2* | 298.4 ± 105.5 | 152.8 ± 53.8* | 296. 9 ± 104.3 | 171.7 ± 38.5* | 325.4 ± 100.1 | 170.6 ± 40.2* | 321.2 ± 104.0 | 174.5 ± 41.3* | 324.2 ± 101.0 | 160.4 ± 33.0* | 322.1 ± 103.4 |

| RMP, W/kg | 3.3 ± 0.9* | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.5* | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.6* | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.4* | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.6* | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.5* | 4.3 ± 0.9 |

| ALMP, W/m2 | 83.0 ± 21.0* | 107.3 ± 30.0 | 54.1 ± 15.6* | 107.1 ± 29.6 | 69.5 ± 12.8* | 116.0 ± 27.3 | 68.5 ± 13.9* | 115.0 ± 28.5 | 68.5 ± 12.2* | 116.4 ± 26.9 | 65.4 ± 11.9* | 115.0 ± 28.4 |

| SMP, kg | 15.7 ± 4.7* | 16.5 ± 4.6 | 8.3 ± 2.6* | 16.5 ± 4.6 | 13.1 ± 2.7* | 17.8 ± 4.3 | 12.8 ± 3.0* | 17.9 ± 4.2 | 13.2 ± 2.9* | 17.8 ± 4.3 | 11.6 ± 1.7* | 18.2 ± 3.9 |

| ASM, kg | 13.3 ± 2.4* | 18.2 ± 5.1 | 13.3 ± 5.1* | 18.3 ± 5.0 | 13.3 ± 2.7* | 18.4 ± 5.0 | 13.5 ± 2.5* | 18.0 ± 5.0 | 13.4 ± 2.7* | 18.4 ± 5.0 | 13.8 ± 2.9* | 17.9 ± 5.1 |

| SBP, mmHg | 125.1 ± 13.5* | 130.6 ± 16.3 | 130.1 ± 13.7 | 130.2 ± 16.2 | 127.8 ± 16.6* | 130.6 ± 16.1 | 128.0 ± 15.8 | 130.1 ± 16.3 | 127.2 ± 16.0 | 130.7 ± 16.3 | 126.4 ± 16.5* | 130.6 ± 16.0 |

| DBP, mmHg | 75.6 ± 8.5 | 77.3 ± 9.8 | 75.3 ± 9.9 | 77.2 ± 9.7 | 75.7 ± 9.7* | 77.5 ± 9.7 | 76.0 ± 9.2 | 77.1 ± 9.7 | 75.2 ± 9.5 | 77.5 ± 9.7 | 74.7 ± 9.1* | 77.3 ± 9.6 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 102.6 ± 22.1 | 107.0 ± 24.3 | 123.6 ± 30.7* | 106.9 ± 24.3 | 103.2 ± 20.1* | 107.8 ± 25.2 | 103.6 ± 21.7* | 107.1 ± 24.7 | 103.1 ± 19.5* | 107.7 ± 25.2 | 130.3 ± 20.7* | 107.4 ± 24.9 |

| Total blood cholesterol, mg/dL | 208.6 ± 33.6 | 203.5 ± 36.6 | 192.6 ± 31.6 | 203.6 ± 36.4 | 213.0 ± 35.4* | 202.4 ± 36.1 | 210.9 ± 34.5* | 203.6 ± 36.3 | 213.0 ± 35.6* | 202.5 ± 36.0 | 213.8 ± 36.2* | 203.2 ± 36.2 |

5STS= 5-time sit-to-stand test; ALMP= Allometric muscle power; AMP= Absolute muscle power; ASM= Appendicular skeletal muscle; BMI= Body mass index; DBP= Diastolic blood pressure; IHG= Isometric handgrip strength; RMP= Relative muscle power; SBP= Systolic blood pressure; SMP= Specific muscle power.

P < 0.05 vs non-sarcopenia.

Fig. 1.

Level of agreement between sarcopenic indexes.

As per the study design, ASM, IHG, 5STS, and muscle power measures were significantly lower in those with sarcopenia, regardless of the assessment method, in comparison to non-sarcopenic participants. Furthermore, individuals with sarcopenia operationalized according to 5STS had higher BMI, whereas those with sarcAMP, sarcALMP, and sarcSMP had lower values, when compared to participants with no sarcopenia. SarcIHG, sarcAMP, and sarcSMP groups had lower BP levels relative to non-sarcopenia. Higher blood cholesterol levels were found in sarcAMP, sarcRMP, sarcALMP, and sarcSMP. Blood glucose levels varied according to the method used to operationalize sarcopenia, with higher values observed in those with sarc5STS and sarcRMP, and lower concentrations found in participants with sarcAMP, sarcRMP, and sarcALMP.

3.2. Associations between sarcopenia and health-related parameters

The associations between sarcopenia and health-related parameters are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted analysis, sarcopenia, regardless of the operationalization method, was significantly and inversely associated with the capacity to walk 400 m. All indexes, except for sarcALMP, were significantly associated with self-reported health status, with sarcopenic individuals having a higher likelihood of rating their health status as poor. When sarcopenia was operationalized according to muscle power measures, it was significantly associated with blood cholesterol and glucose levels. Significant associations were also observed between sarcIHG, sarcAMP, sarcALMP, and sarcSMP with BP levels. PA and sleep quality were significantly associated with sarc5STS. These variables were also associated with sarcRMP and sarcALMP, respectively. Only sarcRMP was significantly associated with adherence to the MED diet, with sarcopenic individuals showing a higher likelihood of having lower levels of adherence. No significant associations were observed with verbal fluency.

Table 2.

Associations between sarcopenic indexes and health parameters.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | ||||||

| 400 m | ||||||

| OR | P-value | CI | OR | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 2.529 | 0.002 | 1.414, 4.524 | −0.395 | 0.003 | 0.212, 0.736 |

| sarc5STS | 3.769 | 0.002 | 1.647, 8.623 | 2.118 | 0.139 | 0.783, 5.731 |

| sarcAMP | 1.909 | 0.001 | 1.363, 2.676 | 2.701 | 0.001 | 1.842, 3.960 |

| sarcRMP | 3.477 | 0.001 | 2.418, 4.999 | 3.250 | 0.001 | 2.214, 4.770 |

| sarcALMP | 1.738 | 0.002 | 1.235, 2.445 | 2.692 | 0.001 | 1.817, 3.989 |

| sarcSMP | 2.385 | 0.001 | 1.608, 3.537 | 2.789 | 0.001 | 1.812, 4.293 |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| OR | P-value | CI | OR | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 0.727 | 0.162 | 0.465, 1.137 | 1.474 | 0.100 | 0.928, 2.343 |

| sarc5STS | 4.697 | 0.001 | 2.015, 10.947 | 3.534 | 0.005 | 1.454, 8.591 |

| sarcAMP | 1.112 | 0.405 | 0.866, 1.429 | 1.594 | 0.001 | 1.213, 2.094 |

| sarcRMP | 1.649 | 0.001 | 1.245, 2.184 | 1.779 | 0.001 | 1.327, 2.385 |

| sarcALMP | 1.059 | 0.655 | 0.823, 1.364 | 1.598 | 0.001 | 1.209, 2.111 |

| Linear and multiple regressions | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure | ||||||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 5.494 | 0.004 | 1.807, 9.181 | 3.491 | 0.058 | −0.125, 7.108 |

| sarc5STS | 0.108 | 0.972 | −5.957, 6.172 | 1.401 | 0.655 | −4.751, 7.554 |

| sarcAMP | 2.858 | 0.007 | 0.799, 4.917 | −0.139 | 0.898 | −2.265, 1.988 |

| sarcRMP | 2.114 | 0.073 | −0.193, 4.412 | 0.580 | 0.622 | −1.728, 2.887 |

| sarcALMP | 3.521 | 0.001 | 1.444, 5.598 | 0.171 | 0.878 | −2.000, 2.341 |

| sarcSMP | 4.283 | 0.001 | 1.793, 6.774 | 1.571 | 0.221 | −0.945, 4.086 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 1.751 | 0.121 | −0.462, 3.964 | 0.716 | 0.523 | −1.480, 2.911 |

| sarc5STS | 1.944 | 0.294 | −1.691, 5.580 | 2.818 | 0.139 | −0.920, 6.557 |

| sarcAMP | 1.987 | 0.002 | 0.756, 3218 | 0.537 | 0.414 | −0.752, 1.827 |

| sarcRMP | 1.087 | 0.121 | −0.286, 2.459 | 0.193 | 0.786 | −1.199, 1.585 |

| sarcALMP | 2.346 | 0.001 | 1.111, 3.581 | 0.707 | 0.289 | −0.602, 2.016 |

| sarcSMP | 2.585 | 0.001 | 1.096, 4.074 | 1.341 | 0.085 | −0.185, 2.867 |

| Blood cholesterol | ||||||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | −5.051 | 0.230 | −13.306, 3.205 | −0.682 | 0.868 | −8.739, 7.374 |

| sarc5STS | 11.053 | 0.110 | −2.513, 24.639 | 8.192 | 0.241 | −5.515, 21.898 |

| sarcAMP | −10.638 | 0.001 | −15.223, −6.054 | −5.271 | 0.029 | −9.995, −0.547 |

| sarcRMP | −7.237 | 0.006 | −12.409, −2.066 | −4.105 | 0.118 | −9.249, 1.039 |

| sarcALMP | −10.517 | 0.001 | −15.124, −5.910 | −5.499 | 0.024 | −10.287, −0.711 |

| sarcSMP | −10.541 | 0.001 | −16.179, −4.904 | −5.327 | 0.066 | −11.000, 0.346 |

| Blood glucose | ||||||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 4.349 | 0.116 | −1.082, 9.779 | 3.678 | 0.175 | −1.633, 8.990 |

| sarc5STS | −16.756 | 0.001 | −25.554, −7.959 | −11.726 | 0.009 | −20.521, −2.930 |

| sarcAMP | 4.539 | 0.004 | 1.462, 7.615 | 2.878 | 0.073 | −0.265, 6.021 |

| sarcRMP | 3.506 | 0.046 | 0.065, 6.947 | 2.918 | 0.091 | −0.463, 6.300 |

| sarcALMP | 4.546 | 0.004 | 1.452, 7.640 | 2.834 | 0.082 | −0.363, 6.031 |

| sarcSMP | 4.103 | 0.034 | 0.318, 7.889 | 2.161 | 0.260 | −1.598, 5.920 |

| Verbal fluency | ||||||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | Unstandardized B | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | −1.038 | 0.485 | −3.970, 1.894 | −1.218 | 0.444 | −4.357, 1.922 |

| sarc5STS | 0.921 | 0.634 | −2.895, 4.737 | −1.798 | 0.510 | −7.193, 3.597 |

| sarcAMP | 0.139 | 0.895 | −1.932, 2.210 | −0.897 | 0.443 | −3.209, 1.416 |

| sarcRMP | 0.136 | 0.897 | −1.936, 2.207 | −1.579 | 0.170 | −3.846, 0.688 |

| sarcALMP | 0.762 | 0.483 | −1.385, 2.909 | −0.177 | 0.884 | −2.588, 2.233 |

| sarcSMP | 0.041 | 0.970 | −2.138, 2.221 | −1.131 | 0.372 | −3.640, 1.378 |

| Ordinal Regression | ||||||

| Mediterranean diet | ||||||

| Beta | P-value | CI | OR | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | −0.475 | 0.159 | −1.135, 0.186 | −0.512 | 0.131 | −1.176, 0.153 |

| sarc5STS | −0.268 | 0.563 | −1.177, 0.641 | −0.281 | 0.571 | −1.252, 0.690 |

| sarcAMP | −0.023 | 0.890 | −0.355, 0.309 | −0.218 | 0.226 | −0.572, 0.135 |

| sarcRMP | −0.505 | 0.009 | −0.886, −0.124 | −0.604 | 0.002 | −0.994, −0.215 |

| sarcALMP | −0.083 | 0.624 | −0.415, 0.249 | −0.338 | 0.064 | −0.696, 0.019 |

| sarcSMP | −0.099 | 0.633 | −0.503, 0.306 | −0.207 | 0.331 | −0.626, 0.211 |

| Self-reported health status | ||||||

| Beta | P-value | CI | Beta | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 1.124 | 0.001 | 0.587, 1.660 | 1.019 | 0.001 | 0.477, 1.561 |

| sarc5STS | 1.628 | 0.001 | 0.861, 2.395 | 1.388 | 0.001 | 0.586, 2.190 |

| sarcAMP | 0.325 | 0.026 | 0.040, 0.610 | 0.317 | 0.041 | 0.013, 0.621 |

| sarcRMP | 0.671 | 0.001 | 0.350, 0.991 | 0.549 | 0.001 | 0.221, 0.877 |

| sarcALMP | 0.221 | 0.130 | −0.065, 0.507 | 0.276 | 0.079 | −0.032, 0.583 |

| sarcSMP | 0.417 | 0.017 | 0.075, 0.759 | 0.335 | 0.064 | −0.019, 0.690 |

| Sleep quality | ||||||

| Beta | P-value | CI | Beta | P-value | CI | |

| sarcIHG | 0.027 | 0.956 | −0.942, 0.996 | −0.179 | 0.721 | −1.160, 0.803 |

| sarc5STS | 1.177 | 0.015 | 0.229, 2.124 | 0.885 | 0.088 | −0.130, 1.900 |

| sarcAMP | 0.383 | 0.085 | −0.053, 0.820 | 0.202 | 0.395 | −0.264, 0.668 |

| sarcRMP | 0.246 | 0.339 | −0.259, 0.751 | 0.069 | 0.795 | −0.451, 0.589 |

| sarcALMP | 0.670 | 0.003 | 0.227, 1.113 | 0.550 | 0.023 | 0.076, 1.024 |

| sarcSMP | 0.337 | 0.206 | −0.185, 0.859 | 0.167 | 0.548 | −0.378, 0.713 |

5STS= 5-time sit-to-stand test; ALMP= Allometric muscle power; AMP= Absolute muscle power; ASM= Appendicular skeletal muscle; DBP= Diastolic blood pressure; IHG= Isometric handgrip strength; RMP= Relative muscle power; SBP= Systolic blood pressure; SMP= Specific muscle power.

After adjusting the analysis for covariates, results remained significant for the associations between sarcopenic indexes and the capacity to walk 400 m, PA, and adherence to the MED diet. In contrast, no significant associations were observed between sarcopenia indexes and BP. Furthermore, only sarcALMP was significantly associated with blood glucose levels and sleep quality, whereas blood cholesterol had significant associations with sarcAMP and sarcALMP. Regarding self-reported health status, results remained significant for sarcIHG, sarc5STS, sarcAMP, and sarcRMP, but not for sarcSMP.

3.3. False discovery rate

Results of the analysis of the false discovery rate are shown in Table 3. After FDR correction, significant associations were maintained for the capacity to walk 400 m, PA, adherence to the MED diet, blood glucose levels, and self-reported health status. In contrast, the associations with sleep quality and blood cholesterol were no longer statistically significant.

Table 3.

Control for false discovery rate.

| Logistic regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 m | |||

| OR | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | −0.395 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| sarc5STS | 2.118 | 0.139 | 0.139 |

| sarcAMP | 2.701 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| sarcRMP | 3.250 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| sarcALMP | 2.692 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| sarcSMP | 2.789 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Physical activity | |||

| OR | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | 1.474 | 0.100 | 0.100 |

| sarc5STS | 3.534 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| sarcAMP | 1.594 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| sarcRMP | 1.779 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| sarcALMP | 1.598 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | 3.491 | 0.058 | 0.348 |

| sarc5STS | 1.401 | 0.655 | 0.898 |

| sarcAMP | −0.139 | 0.898 | 0.898 |

| sarcRMP | 0.580 | 0.622 | 0.898 |

| sarcALMP | 0.171 | 0.878 | 0.898 |

| sarcSMP | 1.571 | 0.221 | 0.663 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | 0.716 | 0.523 | 0.627 |

| sarc5STS | 2.818 | 0.139 | 0.417 |

| sarcAMP | 0.537 | 0.414 | 0.621 |

| sarcRMP | 0.193 | 0.786 | 0.786 |

| sarcALMP | 0.707 | 0.289 | 0.578 |

| sarcSMP | 1.341 | 0.085 | 0.417 |

| Blood cholesterol | |||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | −0.682 | 0.868 | 0.868 |

| sarc5STS | 8.192 | 0.241 | 0.289 |

| sarcAMP | −5.271 | 0.029 | 0.087 |

| sarcRMP | −4.105 | 0.118 | 0.117 |

| sarcALMP | −5.499 | 0.024 | 0.087 |

| sarcSMP | −5.327 | 0.066 | 0.132 |

| Blood glucose | |||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | 3.678 | 0.175 | 0.210 |

| sarc5STS | −11.726 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| sarcAMP | 2.878 | 0.073 | 0.135 |

| sarcRMP | 2.918 | 0.091 | 0.135 |

| sarcALMP | 2.834 | 0.082 | 0.135 |

| sarcSMP | 2.161 | 0.260 | 0.260 |

| Verbal fluency | |||

| Unstandardized B | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | −1.218 | 0.444 | 0.612 |

| sarc5STS | −1.798 | 0.510 | 0.612 |

| sarcAMP | −0.897 | 0.443 | 0.612 |

| sarcRMP | −1.579 | 0.170 | 0.612 |

| sarcALMP | −0.177 | 0.884 | 0.884 |

| sarcSMP | −1.131 | 0.372 | 0.612 |

| Mediterranean diet | |||

| OR | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | −0.512 | 0.131 | 0.262 |

| sarc5STS | −0.281 | 0.571 | 0.571 |

| sarcAMP | −0.218 | 0.226 | 0.339 |

| sarcRMP | −0.604 | 0.002 | 0.012 |

| sarcALMP | −0.338 | 0.064 | 0.192 |

| sarcSMP | −0.207 | 0.331 | 0.3972 |

| Self-reported health status | |||

| Beta | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | 1.019 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| sarc5STS | 1.388 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| sarcAMP | 0.317 | 0.041 | 0.061 |

| sarcRMP | 0.549 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| sarcALMP | 0.276 | 0.079 | 0.079 |

| sarcSMP | 0.335 | 0.064 | 0.076 |

| Sleep quality | |||

| Beta | P-value | Adjusted p-value | |

| sarcIHG | −0.179 | 0.721 | 0.795 |

| sarc5STS | 0.885 | 0.088 | 0.264 |

| sarcAMP | 0.202 | 0.395 | 0.790 |

| sarcRMP | 0.069 | 0.795 | 0.795 |

| sarcALMP | 0.550 | 0.023 | 0.138 |

| sarcSMP | 0.167 | 0.548 | 0.795 |

5STS= 5-time sit-to-stand test; ALMP= Allometric muscle power; AMP= Absolute muscle power; ASM= Appendicular skeletal muscle; DBP= Diastolic blood pressure; IHG= Isometric handgrip strength; RMP= Relative muscle power; SBP= Systolic blood pressure; SMP= Specific muscle power.

3.4. Comparisons among models

More than one sarcopenia index showed significant associations with 400 m, PA, and self-reported health status. Then, an AIC analysis was performed to identify the model that showed stronger associations with health parameters (Table 4). Lower AIC levels were found for sarcRMP and sarcSMP in 400 m walk and practice of PA, and sarcRMP in self-reported health status.

Table 4.

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for associations between sarcopenia indexes and health parameters.

| 400 m | |

|---|---|

| sarcIHG | 1488.1 |

| sarc5STS | 1444.8 |

| sarcAMP | 1239.2 |

| sarcRMP | 1133.6 |

| sarcALMP | 1233.8 |

| sarcSMP | 1137.7 |

| Physical activity | |

| sarc5STS | 2889.1 |

| sarcAMP | 2565.0 |

| sarcRMP | 2423.3 |

| sarcALMP | 2558.1 |

| sarcSMP | 2411.7 |

| Self-reported health status | |

| sarcIHG | 3053.6 |

| sarc5STS | 2985.9 |

| sarcRMP | 2500.2 |

Bold denotes the lowest value(s).

5STS= 5-time sit-to-stand test; ALMP= Allometric muscle power; AMP= Absolute muscle power; ASM= Appendicular skeletal muscle; DBP= Diastolic blood pressure; IHG= Isometric handgrip strength; RMP= Relative muscle power; SBP= Systolic blood pressure; SMP= Specific muscle power.

4. Discussion

The present study was conducted to examine the associations between sarcopenia indexes operationalized according to IHG, 5STS, and muscle power measures with health-related parameters. The main findings of our investigation indicate that these measures have a low-to-moderate level of agreement, which is reflected in their differing associations with study outcomes. Specifically, operationalizing sarcopenia using muscle power measures provided exclusive or stronger associations with health parameters, when compared to sarcIHG and sarc5STS. Indeed, older adults with sarcopenia according to RMP and SMP values were less likely to report no difficulty to walk 400 m and more likely to be engaged in PA. Worse self-reported health status and lower adherence to the MED diet were also more frequently observed in the sarcRMP group. Furthermore, sarc5STS was inversely associated with blood glucose levels.

The low-to-moderate rate of agreement observed among sarcopenia indexes is probably explained by the fact that the assessment methods used in the present study are not kinesiological and biologically equivalent [26]. Indeed, although these tests have been proposed as similar proxies of muscle strength [6,7], IHG seems to be only moderately associated with muscle strength of other body segments and physical function tests [[27], [28], [29], [30]], whereas more robust results have been reported for 5STS [27,31]. IHG is a static test that requires the activation of the forearm muscles as the primary motor [32], with potential involvement of the shoulder external rotators and abductors as stabilizers [32]. It specifically measures isometric muscle strength at the joint angle held during the test. On the other hand, 5STS requires the coordinated activation of several major and minor muscle groups during different types of muscle contractions (e.g., concentric, eccentric, static) [26,33].

The use of muscle power amplifies differences among assessment methods, given that this physical capacity is expected to be highly dependent on the activation of specific high-threshold motor units [34]. Moreover, muscle power involves other higher-order neuromuscular functions, such as the rate of force development, inter- and intramuscular coordination, and cognitive function [[35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. As such, it is possible that sarcopenia, when operationalized through muscle power measures, reflects a condition of lower coordination and activation of neuromuscular factors than the 5STS or IHG [10].

Results of the present study regarding the exclusive or stronger associations observed for muscle power sarcopenia indexes are supported by extensive evidence suggesting that muscle power is more strongly linked to physical performance than muscle strength [12,[40], [41], [42]]. This scenario reflects the crucial role of muscle power in performing physical function tasks that require acceleration (e.g., walking at a fast pace, rising from a chair, climbing stairs) [15], [40], [41], [43], [44], [45]. As muscle power declines earlier and more substantially with aging compared to muscle strength [12], it might serve as a more sensitive indicator for detecting early and specific detriments in neuromuscular capacity.

Many investigations have found that 5STS-based muscle power measures are significantly associated with hospitalization, frailty, and death in older adults [15,16,46]. The present study adds to the current literature by indicating that muscle power-based sarcopenia indexes are associated with low adherence to the MED diet and negative self-reported health status. MED diet refers to a nutritional pattern passed down through generations, shaped by millennia of cultural exchanges among the people who inhabited the regions surrounding the MED basin [[47], [48], [49]]. A pooled analysis found that a high MED diet adherence was significantly associated with physical performance in community dwelling older adults [50]. Moreover, a high prevalence of dynapenia has been observed in older adults with low adherence to the MED diet [22].

Sarcopenia has long been associated with cardiometabolic problems [51,52]. In the present study, we observed an inverse association between sarcopenia defined by the 5-times sit-to-stand test (sarc5STS) and blood glucose levels. A possible explanation for this finding is that sarcopenic individuals with mobility impairments may experience greater difficulty regulating glycemia, potentially due to increased sedentary behavior and suboptimal nutritional habits, such as low adherence to the Mediterranean diet [53], contributing to the worsening of chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes) [54].

This scenario might also explain the associations with self-reported health status, as it reflects older adults’ perception of various factors, including physical performance, healthy lifestyle habits, body composition, and multimorbidity [55,56]. Muscle power might also be linked with self-reported health status because its preservation is crucial to generate rapid muscle contractions, used in actions as stopping suddenly (e.g., in response to abrupt traffic changes) [57], preventing falls, and reducing hospitalizations. As diminished self-reported health status predicts the occurrence of negative events [58,59], it is plausible that older adults who perceive their health as poor may have experienced mobility and balance impairments linked to reduced muscle power.

Older adults with sarcopenia were more likely to practice PA. Our results emphasize the findings of existent literature, suggesting that the simple adherence to PA is not sufficient to maintain neuromuscular function during aging [60], and further indicate that the regular practice of specific exercise training programs, mainly resistance and power training, combined with moderate-to-high-intensity PA habits are required to counteract sarcopenia [61].

A question that remains is why different associations were found according to the type of muscle power measure. Muscle power is determined by the amount of force produced per unit of time following the onset of muscle contractions [62,63]. RMP refers to the amount of power produced adjusted by the weight lifted, while ALMP is corrected for the distance, and SMP is relative to muscle mass. Many possible scenarios might be hypothesized to explain differences. For instance, individuals with greater body mass require more muscle power to generate movement compared to their lighter counterparts, which explains the stronger associations with the capacity to walk 400 m. On other hand, taller individuals need to generate more force and sustain it for longer periods compared with their shorter counterparts to achieve the same average muscle power. In this case, not adjusting muscle power according to an individual’s height could mask low AMP in shorter older adults. adjusting muscle power for muscle mass yields an index that more accurately reflects the amount of tissue actively contributing to power generation. Further research is needed to better elucidate this relationship.

Findings of the present study hold meaningful implications for clinical practice, screening, and intervention strategies aimed at preserving neuromuscular health in older adults. The stronger and exclusive associations observed for muscle power-based sarcopenia indexes suggest that the evaluation of this parameter should be present in the routine assessment of older adults. The 5STS, already commonly used in clinical and community settings, can be easily adapted to estimate muscle power with minimal additional equipment or training. This enhances its feasibility for large-scale screening efforts. Additionally, findings reinforce the need for tailored interventions that go beyond general physical activity promotion. Clinicians and health professionals should prioritize resistance and power training exercises in their recommendations, particularly for older adults with early signs of muscle dysfunction. Embedding these practices into standard geriatric care may enhance physical resilience, support healthy aging, and reduce the risk of negative health outcomes.

The present study has limitations that should be acknowledged to provide a better interpretation of our results. First, lower limb muscle power and ASM were estimated through equations rather than being measured directly. Second, the fact that sarcopenia indexes operationalized through muscle power were exclusively or more strongly associated with health parameters might be dependent on the conditions of our sample, which involved relatively young community-dwelling Caucasian older adults with apparently preserved physical function, given that declines in muscle power in this age group are frequently more significant than those in muscle strength. Third, participants were evaluated while attending a public event. As such, the evaluation setting may have influenced physical performance outcomes, and this context may limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader older adult population. Fourth, information on chronic diseases (e.g., osteoarthritis) or medications (e.g., corticosteroids) that could impact musculoskeletal health was not available. The collection of detailed medical history would substantially increase the duration of the assessments, making them unsuitable for the unconventional settings where the research is conducted. Fifth, low IHG and 5STS performance were identified according to cutoff values proposed by the revised guidelines of the EWGSOP. Different results might be obtained using age- and sex-specific cutoff points. Sixth, the lack of a detailed examination of participants’ characteristics precludes the conduction of sensitivity analysis to provide valuable insights into the robustness of our findings. Seventh, although ASM and muscle power were estimated using validated questions, future studies using gold standard instruments are necessary to confirm and expand our findings. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes any conclusions about the temporal sequence or causality of the observed associations. To better understand directionality and potential causal relationships, future research should include longitudinal analyses that monitor changes in sarcopenia-related parameters and associated outcomes, such as: PA, metabolic markers, and health status, over time. These studies could help determine whether alterations in muscle mass and function precede or result from changes in these health indicators.

5. Conclusions

Findings of the present study indicate that sarcopenia indexes based on muscle strength and muscle power capture different aspects of older adults’ health. Operationalizing sarcopenia using muscle power measures provided exclusive or stronger associations with health parameters, when compared to sarcIHG and sarc5STS.

Ethical approval

The Lookup 8+ protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (protocol #: A.1220/CE/2011).

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

No Generative AI or AI -assisted technologies were used in the writing process.

Data availability statement

Raw data files are available from Prof. Landi upon reasonable request.

† Lookup Study Group

Francesco Landi,a,b Roberto Bernabei,a Emanuele Marzetti,a,b Riccardo Calvani,a,b Luca Mariotti,a Stefano Cacciatore,a,b Hélio José Coelho-Junior,a,b Francesca Ciciarello,b Vincenzo Galluzzo,b Anna Maria Martone, a,b Anna Picca,b,c Andrea Russo,b Sara Salini,b Matteo Tosato,b Gabriele Abbatecola,a Clara Agostino,a Fiorella Ambrosio,a Francesca Banella,a Carolina Benvenuto,a Damiano Biscotti,b Vincenzo Brandi,b Maria Modestina Bulla,a Caterina Casciani,a Lucio Catalano,b Camilla Cocchi,a,b Giuseppe Colloca,b Federica Cucinotta,a, Emanuela D’Angelo,b Mariaelena D’Elia,b Federica D’Ignazio,a,b Daniele Elmi,a Marta Finelli,a Francesco Pio Fontanella,a Domenico Fusco,b Ilaria Gattari,a Giordana Gava,a,b Tommaso Giani,a,b Giulia Giordano,a,b Rossella Giordano,a,b Francesca Giovanale,a Simone Goracci,a Silvia Ialungo,a,b Rosangela Labriola,a,b Elena Levati,a,b Myriam Macaluso,a,b Luca Marrella,a Claudia Massaro,a,b Rossella Montenero,a,b Maria Vittoria Notari,a Maria Paudice,a Martina Persia,a Flavia Pirone,a Simona Pompei,b Rosa Ragozzino,a Carla Recupero,a Antonella Risoli,a,b Stefano Rizzo,a,b Daria Romaniello,a Giulia Rubini,a Barbara Russo,a Stefania Satriano,a Giulia Savera,a Elisabetta Serafini,b Annalise Serra Melechì,b Francesca Simeoni,a Sofia Simoni,a,b Chiara Taccone,a Elena Tagliacozzi,a Roberta Terranova,a Salvatore Tupputi,a Matteo Vaccarella,a Emiliano Venditti,a Chiara Zanchi,a Maria Zuppardo,a

Affiliations

a Department of Geriatrics, Orthopedics and Rheumatology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go F. Vito 1, 00,168 Rome, Italy

b Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “Agostino Gemelli” IRCCS, L. go A. Gemelli 8, 00,168 Rome, Italy

c Department of Medicine and Surgery, LUM University, Strada Statale 100 km 18, 70,100 Casamassima, Italy

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hélio José Coelho Júnior: . Alejandro Álvarez-Bustos: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Riccardo Calvani: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Stefano Cacciatore: . Anna Picca: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Matteo Tosato: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Francesco Landi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Emanuele Marzetti: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affi liations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any fi nancial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affi liations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The APC was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2025).

Contributor Information

Hélio José Coelho Júnior, Email: coelhojunior@hotmail.com.br.

Emanuele Marzetti, Email: emanuele.marzetti@policlinicogemelli.it.

Lookup Study Group:

Francesco Landi, Roberto Bernabei, Emanuele Marzetti, Riccardo Calvani, Luca Mariotti, Stefano Cacciatore, Hélio José Coelho-Junior, Francesca Ciciarello, Vincenzo Galluzzo, Anna Maria Martone, Anna Picca, Andrea Russo, Sara Salini, Matteo Tosato, Gabriele Abbatecola, Clara Agostino, Fiorella Ambrosio, Francesca Banella, Carolina Benvenuto, Damiano Biscotti, Vincenzo Brandi, Maria Modestina Bulla, Caterina Casciani, Lucio Catalano, Camilla Cocchi, Giuseppe Colloca, Federica Cucinotta, Emanuela D’Angelo, Mariaelena D’Elia, Federica D’Ignazio, Daniele Elmi, Marta Finelli, Francesco Pio Fontanella, Domenico Fusco, Ilaria Gattari, Giordana Gava, Tommaso Giani, Giulia Giordano, Rossella Giordano, Francesca Giovanale, Simone Goracci, Silvia Ialungo, Rosangela Labriola, Elena Levati, Myriam Macaluso, Luca Marrella, Claudia Massaro, Rossella Montenero, Maria Vittoria Notari, Maria Paudice, Martina Persia, Flavia Pirone, Simona Pompei, Rosa Ragozzino, Carla Recupero, Antonella Risoli, Stefano Rizzo, Daria Romaniello, Giulia Rubini, Barbara Russo, Stefania Satriano, Giulia Savera, Elisabetta Serafini, Annalise Serra Melechì, Francesca Simeoni, Sofia Simoni, Chiara Taccone, Elena Tagliacozzi, Roberta Terranova, Salvatore Tupputi, Matteo Vaccarella, Emiliano Venditti, Chiara Zanchi, and Maria Zuppardo

References

- 1.Roubenoff R. Sarcopenia and its implications for the elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(Suppl 3):S40–S47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roubenoff R. Sarcopenia: effects on body composition and function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:1012–1017. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.11.m1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roubenoff R. Sarcopenia: a major modifiable cause of frailty in the elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2000;4:140–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L-K, Liu L-K, Woo J., Assantachai P., Auyeung T.-W., Bahyah K.S., et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Baeyens J.P., Bauer J.M., Boirie Y., Cederholm T., Landi F., et al. Sarcopenia: european consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Bahat G., Bauer J., Boirie Y., Bruyère O., Cederholm T., et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48:16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L.K., Woo J., Assantachai P., Auyeung T.W., Chou M.Y., Iijima K., et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on Sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21 doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012. 300-307.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cawthon P.M., Lui L.Y., Taylor B.C., McCulloch C.E., Cauley J.A., Lapidus J., et al. Clinical definitions of sarcopenia and risk of hospitalization in community-dwelling older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1383–1389. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaudart C., Locquet M., Touvier M., Reginster J.Y., Bruyère O. Association between dietary nutrient intake and sarcopenia in the SarcoPhAge study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31:815–824. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coelho-Júnior H.J., Álvarez-Bustos A., Landi F., da Silva Aguiar S., Rodriguez-Mañas L., Marzetti E. Why are we not exploring the potential of lower limb muscle power to identify people with sarcopenia? Ageing Res Rev. 2025;104 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2025.102662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans W.J., Guralnik J., Cawthon P., Appleby J., Landi F., Clarke L., et al. Sarcopenia: no consensus, no diagnostic criteria, and no approved indication-how did we get here? Geroscience. 2024;46:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s11357-023-01016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauretani F., Russo C.R., Bandinelli S., Bartali B., Cavazzini C., Di Iorio A., et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1851–1860. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. (1985) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coelho-Júnior H.J., Álvarez-Bustos A., Rodríguez-Mañas L., de Oliveira Gonçalves I., Calvani R., Picca A., et al. Five-time sit-to-stand lower limb muscle power in older women: an explorative, descriptive and comparative analysis. J Frailty Aging. 2024:1–8. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2024.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coelho-Júnior H.J., da Silva Aguiar S., de Oliveira Gonçalves I., Álvarez-Bustos A., Rodríguez-Mañas L., Uchida M.C., et al. Agreement and associations between countermovement jump, 5-time sit-to-stand, lower-limb muscle power equations, and physical performance tests in community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Med. 2024;13:3380. doi: 10.3390/jcm13123380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coelho-Júnior H.J., Calvani R., Álvarez-Bustos A., Tosato M., Russo A., Landi F., et al. Physical performance and negative events in very old adults: a longitudinal study examining the ilSIRENTE cohort. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2024;36:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40520-024-02693-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Losa-Reyna J., Alcazar J., Carnicero J., Alfaro-Acha A., Castillo-Gallego C., Rosado-Artalejo C., et al. Impact of relative muscle power on hospitalization and all-cause mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77:781–789. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glab230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skelton D.A., Greig C.A., Davies J.M., Young A. Strength, power and related functional ability of healthy people aged 65-89 years. Age Ageing. 1994;23:371–377. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landi F., Calvani R., Picca A., Tosato M., Martone A.M., Ortolani E., et al. Body mass index is strongly associated with hypertension: results from the longevity check-up 7+ study. Nutrients. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/nu10121976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landi F., Calvani R., Martone A.M., D’angelo E., Serafini E., Ortolani E., et al. Daily meat consumption and variation with aging in community-dwellers: results from longevity check-up 7 + project. J Gerontol Geriat. 2019;67:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landi F., Calvani R., Martone A.M., Salini S., Zazzara M.B., Candeloro M., et al. Normative values of muscle strength across ages in a “real world” population: results from the longevity check-up 7+ project. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11:1562–1569. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landi F., Calvani R., Picca A., Tosato M., D’Angelo E., Martone A.M., et al. Relationship between cardiovascular health metrics and physical performance in community-living people: results from the longevity check-up (Lookup) 7+ project. Sci Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34746-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cacciatore S., Calvani R., Marzetti E., Picca A., Coelho-Júnior H.J., Martone A.M., et al. Low adherence to Mediterranean diet is associated with probable sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: results from the longevity check-up (Lookup) 7+ project. Nutrients. 2023:15. doi: 10.3390/nu15041026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P., et al. The strengthening the reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos L.P., Gonzalez M.C., Orlandi S.P., Bielemann R.M., Barbosa-Silva T.G., Heymsfield S.B. New prediction equations to estimate appendicular skeletal muscle mass using calf circumference: results from NHANES 1999–2006. J Parenteral Enteral Nutrit. 2019;43:998–1007. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alcazar J., Losa-Reyna J., Rodriguez-Lopez C., Alfaro-Acha A., Rodriguez-Mañas L., Ara I., et al. The sit-to-stand muscle power test: an easy, inexpensive and portable procedure to assess muscle power in older people. Exp Gerontol. 2018;112:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coelho-Júnior H.J., Calvani R., Picca A., Marzetti E. Are sit-to-stand and isometric handgrip tests comparable assessment tools to identify dynapenia in sarcopenic people? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2023.105059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris-Love M.O., Benson K., Leasure E., Adams B., McIntosh V. The influence of upper and lower extremity strength on performance-based sarcopenia assessment tests. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2018;3 doi: 10.3390/jfmk3040053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins N.D.M., Buckner S.L., Bergstrom H.C., Cochrane K.C., Goldsmith J.A., Housh T.J., et al. Reliability and relationships among handgrip strength, leg extensor strength and power, and balance in older men. Exp Gerontol. 2014;58:47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostolin T.L.V.D.P., Gonze B de B., de Oliveira Vieira W., de Oliveira A.L.S., Nascimento M.B., Arantes R.L., et al. Association between the handgrip strength and the isokinetic muscle function of the elbow and the knee in asymptomatic adults. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/2050312121993294. 2050312121993294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roman-Liu D., Tokarski T. Mazur-Różycka J. Is the grip force measurement suitable for assessing overall strength regardless of age and gender? Measurement. 2021;176 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones C.J., Rikli R.E., Beam W.C. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70:113–119. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S., Shim J., Park M. A study on the activation of forearm muscles during gripping by handle thickness. J Phys Ther Sci. 2011;23:549–551. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehail P., Bestaven E., Muller F., Mallet A., Robert B., Bourdel-Marchasson I., et al. Kinematic and electromyographic analysis of rising from a chair during a “sit-to-walk” task in elderly subjects: role of strength. Clin Biomech. 2007;22:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraemer W.J., Looney D.P. Underlying mechanisms and physiology of muscular power. Strength Cond J. 2012;34:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35.HJ Coelho-Júnior. Is high-speed resistance training an efficient and feasible exercise strategy for frail nursing home residents? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23:44–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coelho-Júnior H.J., Aguiar S da S, Calvani R., Picca A., Carvalho D de A, Zwarg-Sá J da C, et al. Acute effects of low- and high-speed resistance exercise on cognitive function in frail older nursing-home residents: a randomized crossover study. J Aging Res. 2021;2021:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2021/9912339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cormie P., McGuigan M.R., Newton R.U. Developing maximal neuromuscular power: part 2 training considerations for improving maximal power production. Sports Med. 2011;41:125–146. doi: 10.2165/11538500-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cormie P., McGuigan M.R., Newton R.U. Developing maximal neuromuscular power: part 1–biological basis of maximal power production. Sports Med. 2011;41:17–38. doi: 10.2165/11537690-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraemer W., Newton R. Training for muscular power. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000;11:341–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki T., Bean J.F., Fielding R.A. Muscle power of the ankle flexors predicts functional performance in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1161–1167. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bean J.F., Leveille S.G., Kiely D.K., Bandinelli S., Guralnik J.M., Ferrucci L. A comparison of leg power and leg strength within the InCHIANTI study: which influences mobility more? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:728–733. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.8.m728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hetherington-Rauth M., Magalhães J.P., Alcazar J., Rosa G.B., Correia I.R., Ara I., et al. Relative sit-to-stand muscle power predicts an older adult’s physical independence at age of 90 yrs beyond that of Relative handgrip strength, physical activity, and sedentary time: a cross-sectional analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;101:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuoco A., Callahan D.M., Sayers S., Frontera W.R., Bean J., Fielding R.A. Impact of muscle power and force on gait speed in disabled older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:1200–1206. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.11.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman S., Kiely D.K., Leveille S., O’Neill E., Cyberey S., Bean J.F. Upper and lower limb muscle power relationships in mobility-limited older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:476–480. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alcazar J., Alegre L.M., Suetta C., Júdice P.B., Van Roie E., González-Gross M., et al. Threshold of relative muscle power required to rise from a chair and mobility limitations and disability in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53:2217–2224. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burbank C.M., Branscum A., Bovbjerg M.L., Hooker K., Smit E. Muscle power predicts frailty status over four years: a retrospective cohort study of the National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2023;8:1–8. doi: 10.22540/JFSF-08-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis C., Bryan J., Hodgson J., Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; a literature review. Nutrients. 2015;7:9139–9153. doi: 10.3390/nu7115459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trichopoulou A., Vasilopoulou E. Mediterranean diet and longevity. Br J Nutr. 2000;84(Suppl 2):205–209. doi: 10.1079/096582197388554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trichopoulou A., Martínez-González M.A., Tong T.Y.N., Forouhi N.G., Khandelwal S., Prabhakaran D., et al. Definitions and potential health benefits of the Mediterranean diet: views from experts around the world. BMC Med. 2014;12 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.HJ Coelho-Júnior, Trichopoulou A., Panza F. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between adherence to Mediterranean diet with physical performance and cognitive function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Izzo A., Massimino E., Riccardi G., Della Pepa G. A narrative review on sarcopenia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence and associated factors. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–18. doi: 10.3390/nu13010183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bai T., Fang F., Li F., Ren Y., Hu J., Cao J. Sarcopenia is associated with hypertension in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:279. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01672-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loprinzi P.D., Smit E., Mahoney S. Physical activity and dietary behavior in US adults and their combined influence on health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee I.-M., Shiroma E.J., Lobelo F., Puska P., Blair S.N., Katzmarzyk P.T., et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moser N., Sahiti F., Gelbrich G., Cejka V., Kerwagen F., Albert J., et al. Association between self-reported and objectively assessed physical functioning in the general population. Sci Rep. 2024;14 doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-64939-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hambleton I.R., Clarke K., Broome H.L., Fraser H.S., Brathwaite F., Hennis A.J. Historical and current predictors of self-reported health status among elderly persons in Barbados. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;17:342–352. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orr R., de Vos N.J., Singh N.A., Ross D.A., Stavrinos T.M., Fiatarone-Singh M.A. Power training improves balance in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:78–85. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansen T.B., Thygesen L.C., Zwisler A.D., Helmark L., Hoogwegt M., Versteeg H., et al. Self-reported health-related quality of life predicts 5-year mortality and hospital readmissions in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:882–889. doi: 10.1177/2047487314535682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGee D.L., Liao Y., Cao G., Cooper R.S. Self-reported health status and mortality in a multiethnic US cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:41–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sánchez-Sánchez J.L., He L., Morales J.S., de Souto, Barreto P., Jiménez-Pavón D., Carbonell-Baeza A., et al. Association of physical behaviours with sarcopenia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5:e108–e119. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coelho-Júnior H.J., Uchida M.C., Picca A., Bernabei R., Landi F., Calvani R., et al. Evidence-based recommendations for resistance and power training to prevent frailty in community-dwellers. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodríguez-Rosell D., Pareja-Blanco F., Aagaard P., González-Badillo J.J. Physiological and methodological aspects of rate of force development assessment in human skeletal muscle. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018;38:743–762. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maffiuletti N.A., Aagaard P., Blazevich A.J., Folland J., Tillin N., Duchateau J. Rate of force development: physiological and methodological considerations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116:1091–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00421-016-3346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data files are available from Prof. Landi upon reasonable request.